Brian Clegg's Blog, page 21

May 20, 2023

Review: English Journey - J. B. Priestley ****

Sometimes a particular book keeps coming to your attention from different directions and you know that you will have to read it. This was the case with J. B. Priestley's English Journey - in fact I'd bought a copy before I even realised that it was the inspiration for the latest title from my favourite current English travel(ish) writer, Stuart Maconie.

Sometimes a particular book keeps coming to your attention from different directions and you know that you will have to read it. This was the case with J. B. Priestley's English Journey - in fact I'd bought a copy before I even realised that it was the inspiration for the latest title from my favourite current English travel(ish) writer, Stuart Maconie.Priestley made a journey around parts of England in 1933 - not the pretty bits (apart from the Cotswolds) but more what back then were thought of as that derogatory feeling location 'the provinces'. Priestley was an odd mix for the period - a London literary type, but one from Bradford who still considered being northern a positive. What he is without doubt superb on is uncovering the social conditions of the time. Unlike Orwell's attempt, which feels a bit like someone looking at an alien species through a microscope, this is a picture of the common people by someone who identified personally with their plight (although he can still come across as a touch snobbish).

One piece of information he gives really struck home. While visiting Bournville, the Cadbury family's model living space in the West Midlands, he notes (while pondering whether or not such a pleasant but controlling environment is a good thing) that infant mortality is lower than the average 69 per thousand live births in England and Wales. Compare that with the current value of 3.7 and you really realise that, despite all our moans, things are a lot better now than they were in the 1930s.

On a less important, but quite interesting, level I found it remarkable that Priestley was using the word ���robot��� repeatedly only 10 years or so after it appeared in English. It seems to have become very rapidly (for a time with slower communications) embedded as a term that doesn't need explaining. It did also strike me that it was a shame that he chose to make the journey in late autumn/early winter when, to be honest, the weather ensures that few places in England are at their best - he even admits to seeing places differently when it's a rare sunny day.

The greatness of this as a travel book is that it is a portrait not of places, but of the English people, specifically the English working class. Is it sexist? Certainly - it is of its time, though Priestley does at least celebrate the character of women, particularly Lancastrian women. But his genuine sympathy with the plight of so many people whose home town���s reason for existing was an industry that hardly existed anymore is remarkable. It���s also the case that his plea for the left behind of the industrial North is horrendously still an issue 90 years later. Just as Priestley bemoans the way the south east's wealth has been made on the backs of those now discarded workers so we can see the appeal of levelling up��� and exactly the same inability to make it happen as was the case then.

To make a slight personal moan as an inhabitant of Swindon, which is one of the places he visits, it's about the only place dominated by an industry (in Swindon's case, the railway works) where he simply complains that it's not a very nice place to be in, but doesn't bother to visit the workplace as he does practically everywhere else, nor does he really engage with the people. Swindon's main role in the book seems to be to provide a contrast with Bristol and the Cotswolds, which was a little mean of him.I can see why so many people enthuse about this book. It has its faults. Apart from those already mentioned, it is, frankly, significantly too long and spends too much time making any particular point and then re-making at some length. Priestley's style can be a little heavy going to the modern reader. But the fact remains that this a landmark book, which shows just how long levelling up the country has been an issue that successive governments have failed to address.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

You can buy English Journey from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org.Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

May 10, 2023

A scary scam

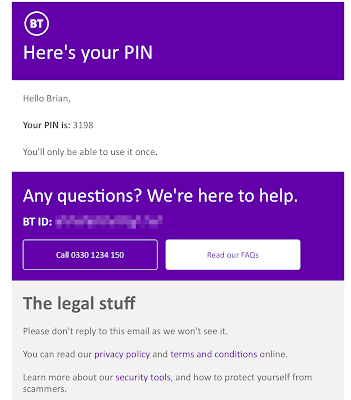

I have just been subject to the most sophisticated scam attempt I've ever come across.

I have just been subject to the most sophisticated scam attempt I've ever come across.I had a call apparently from BT (my broadband provider) to say that my internet had been hacked. To confirm that it was really them, they sent an email and a text with a PIN.

There was admittedly something fishy about it. They weren't able to specify exactly what they meant by my account being hacked, and I was confused about the PIN aspect (more on that in a moment) - so I hung up and called BT myself.

They confirmed that it wasn't them who had been in touch. It was, indeed, a scam. Not only was there not a problem, and they had not contacted me in the last 3 months, the BT operative also confirmed my suspicion about the PIN - the point of a PIN is for me to confirm who I am, not for them to prove who they are. Anyone can send you a PIN and ask you to read it back. BT won't do this when they contact you, only when you contact them.

However, it's easy to see how the text and email could help fool people. The text was apparently from the same number that BT use to send a confirmatory PIN. The wording of the text was almost (but not quite) identical to the BT message. And what I still find unnerving is that the scammers were able to link together my landline phone number, my mobile number (for the text) and the email address I use to log into my BT account.

Because of this linkage, one thing I did do was both change my password on the BT website and switch on two factor authentication (where it sends you a text or email to check it really is you) in case someone had got into their data.

I pride myself on not falling for scam calls. But this one was scarily convincing. Traditionally it's been said that phishing emails and scam calls may be deliberately poor so they are only believed by the most vulnerable. This was certainly not that kind of operation.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

May 9, 2023

Hot under the collar about 'exponential'

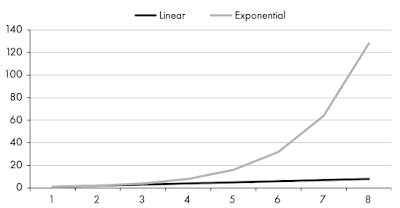

I read an article about how well the Greens did in the local elections recently and got a bit narked. It wasn't about the main thrust of the article (though I'm doubtful how much council election gains for a small party mean in terms of general elections), but rather as a result of a distinctly painful use of the word 'exponential'.

I read an article about how well the Greens did in the local elections recently and got a bit narked. It wasn't about the main thrust of the article (though I'm doubtful how much council election gains for a small party mean in terms of general elections), but rather as a result of a distinctly painful use of the word 'exponential'.In his article, Peter Franklin says 'the Greens grew exponentially — doubling their council seats from 240 to 481'. There are two problems with this. One is you can't tell if growth is exponential from two data points. And the other is that exponential growth does not mean large growth, as seems to be thought here.

For something to grow exponentially, each data point (often with this kind of data, separated over a time period such as a week, month, year or as here election period) has to be related to the original value by the exponent of the number of data points. That sounds far more complicated than it really is. If you have N data points then the Nth value should be around xN, where x is bigger than 1.

A classic example is exponential doubling, where x is 2. In that case, after one time period, the result is twice as much as the original value, after two time periods it's four times the initial value and so on. And yes, if Green councillor growth was to continue to double after the next election we could say there was exponential growth - but not from one election.

Note also that x can be, say 1.005. If there were exponential growth like this, the Green councillor count would go from 240 to 241 in the first time period. That could still be exponential, though we wouldn't know until several time periods had passed.

You might think that this is quibbling about word use, rather like moaning that 'decimation' does not refer to a large reduction, but to a one in ten reduction, as it originally did when the Romans were in the habit of killing off one in ten as a punishment. But decimation isn't a scientific term. Exponential is, and it's a very useful term that shouldn't be diluted.

Journalists, please don't mangle it.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

May 8, 2023

The Daughters of Cain - Colin Dexter ****

Having read rather a lot of new murder mysteries recently, I thought it would be worth revisiting one of the classics - in this case, one of the Oxford antics of Morse. This is quite a late period Morse from 1994, when the books had been strongly influenced by the TV series: Morse has a red Jaguar, is significantly older than Lewis (rather than the other way round) and is more like John Thaw. However, this doesn't mean the book doesn't have all the usual expectations of Colin Dexter's writing.

Having read rather a lot of new murder mysteries recently, I thought it would be worth revisiting one of the classics - in this case, one of the Oxford antics of Morse. This is quite a late period Morse from 1994, when the books had been strongly influenced by the TV series: Morse has a red Jaguar, is significantly older than Lewis (rather than the other way round) and is more like John Thaw. However, this doesn't mean the book doesn't have all the usual expectations of Colin Dexter's writing.One thing that's interesting about this as a detective novel is that it's much more a 'how dunnit' than a 'who dunnit'. It is obvious who's behind the killings both to Morse and us from fairly early on. But getting any further is stymied by solid alibis and tortuous possibilities - all excellently handled.

Dexter's writing style can take a little while to get back into. He was always a wordy writer, and can intrude in the author's voice rather more than is common in a modern novel. One thing that particularly struck me was the time and effort he put into the quotes that start each chapter. These are not just random bits of filler - they contribute to the storyline, and are often fascinating in their own right.

There are arguably elements of sexism in the book that feel a little uncomfortable now. It's not so much the sexism of many TV detective shows, where the victim is far too often female, but rather the way every female character seems to fancy Morse, who seems to have few redeeming features in reality - and this even includes someone less then half his age falling in love with him. Perhaps even worse, Dexter can come across as distinctly condescending to his less educated characters.

However, most period murder mysteries have some issues. I love Margery Allingham, but her books certainly have an undeserved respect for, say old buffer Chief Constables with no brains. So I'm inclined to say that Dexter was of his period, and with that proviso, we can still say that this is a satisfying and intriguing mystery.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can buy The Daughters of Cain from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

May 2, 2023

Review: Mythago Wood - Robert Holdstock *****

For me, almost all the best fantasy has one foot in the real world (I'll make an exception for Lord of the Rings and Terry Pratchett's books). Such books work by juxtaposing the weirdness of fantasy with our everyday lives, meaning authors can deliver far more impact. If asked to name great authors who have written in this vein it would be easy to name the likes of Gene Wolfe, Neil Gaiman and Alan Garner - but it's somehow easy to forget Robert Holdstock.

For me, almost all the best fantasy has one foot in the real world (I'll make an exception for Lord of the Rings and Terry Pratchett's books). Such books work by juxtaposing the weirdness of fantasy with our everyday lives, meaning authors can deliver far more impact. If asked to name great authors who have written in this vein it would be easy to name the likes of Gene Wolfe, Neil Gaiman and Alan Garner - but it's somehow easy to forget Robert Holdstock. Part of the problem with a book like this might be that this type of fantasy is often labelled urban fantasy, but like most of Garner's work, some of the best would be better countryside fantasy - and none more so than Holdstock's Mythago Wood.

I first read this in the 1980s and have come back to it a couple of times since, but starting as I did in that pre-internet era, I never realised it was the first of a series of books, so I've re-read it now before getting on to the sequel, Avondiss - and it is still a remarkable book.

Set in the years following the Second World War, we follow Steven Huxley's attempts to understand his father's obsession with Ryhope Wood, a large stretch of ancient woodland at the bottom of their garden. Huxley's father was convinced that the wood had strange properties, which enabled 'mythagos' to form - folk memories and legends that became tangible. After their father's death, Huxley's brother Christian is trying to explore the wood with frightening consequences that drag Steven into an attempt to uncover what really is happening.

I mentioned Alan Garner above - in this book, Holdstock proves himself very much Garner's heir (I know Garner has outlived Holdstock, but I mean rather his cultural heir). The key to Garner's work is a sense of place and its impact on reality - perceived and actual - and this comes through very strongly in Mythago Wood. There's also sometimes a theme of obsession in Garner, and again obsession is crucial here to the very mechanics of the fantasy logic.

This is quite possibly the most atmospheric fantasy I've ever read - it's certainly one of the best. Anyone with an interest in the genre should have a copy.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can buy Mythago Wood from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

April 29, 2023

Review: Moriarty - Anthony Horowitz *****

This crime novel dates back to 2014, but given the subject, it's timeless. Many people have attempted to continue Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes canon with mixed success. I think it's fair to say that Anthony Horowitz has been one of the most successful, by taking a distinctly tangential approach to the Holmes universe.

This crime novel dates back to 2014, but given the subject, it's timeless. Many people have attempted to continue Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes canon with mixed success. I think it's fair to say that Anthony Horowitz has been one of the most successful, by taking a distinctly tangential approach to the Holmes universe.That's not to say that there isn't some pastiche here. As well as the main novel, the book contains two short stories. One is Conan Doyle's own The Final Problem - the one where Conan Doyle, fed up with his creation, killed Holmes off at the Reichenbach Falls in Switzerland - this is accompanied by an insightful introduction by Horowitz. The other is a 'new' Sherlock Holmes short story featuring the Scotland Yard detective who will play a major part in the novel, Athelney Jones (who also appeared in one of the original Holmes stories).

In the main novel, which is set shortly after Holmes and Moriarty apparently perish by plunging off the waterfall, we get a new pairing. There is Jones, who after being mocked by Dr Watson for his ineptitude in The Sign of the Four has set out to study and apply Holmes' methods, accompanied by his own version of Watson, an American Pinkerton detective called Frederick Chase, who is the first person narrator of the story. Spurred on by a letter found on Moriarty's body, they try to track down an American crime lord who is trying to take over Moriarty's criminal legacy in London.

It is all beautifully done - there is an excellent period feel, though Horowitz allows us considerably more nastiness in the violence (arguably are more accurate portrayal of Victorian London) than Conan Doyle ever did. The action carries us forward with a relentless pace. And the ending has one of the most impressive twists I've ever seen in a book like this. Remarkably (even though this was my second time reading it), I got to page 327 before noticing once more (when the narrator points it out) that there is a huge clue in plain sight from first picking up the book.

An essential for anyone with an interest in the world of Sherlock Holmes - but also an excellent standalone mystery in its own right.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can buy Moriarty from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

April 26, 2023

I want to write a non-fiction book - part 8 - self-publishing

Up to this point, this series (outline at the bottom of the post) has been about having a book published by a publisher, but self-publishing is now a much easer option in some ways than it used to be. The Tl;dr summary is 'It's easy to do, but it's really difficult to do well.' I've done it myself for most of my fiction, but what I describe below applies equally well to non-fiction.

Up to this point, this series (outline at the bottom of the post) has been about having a book published by a publisher, but self-publishing is now a much easer option in some ways than it used to be. The Tl;dr summary is 'It's easy to do, but it's really difficult to do well.' I've done it myself for most of my fiction, but what I describe below applies equally well to non-fiction.Personally I prefer to go through a publisher if I can, because they take away a lot of the hassle - but I'd rather have a book self-published than not at all. Others love the whole business - how you will find it will certainly depend on how much time and effort you can put into it.

There are many routes to self-publishing. I'm going to describe using KDP, Amazon's route, which for me is the most likely to result in good sales and is relatively easy to use. What I'm describing here is different from vanity publishing or hybrid publishing. Here, a publishing company does (some of) the work for you and you typically pay them up front, then get a higher percentage of the cover price than with a traditional publisher. I know a few people who have found this a good experience, but there are a number of dubious vanity publishers who take your money and don't do anything much in the way of editing, distribution or publicity - which means they are little more than expensive self-publishers. I don't have personal experience, but my feeling is that this approach is not for me as my number one rule of being published is that I should be paid, rather than pay, for the experience.

If you are going to self-publish, the first essential is to get someone else to edit your book. Paying someone is an option. Alternatively, while I don't think friends and relations give useful feedback on whether or not a book is any good, it's perfectly possible for a friend or relation to do a proof read, looking for typos and errors. What you can't assume is that just because said friend or relation is a writer or in the publishing business they are any good at this. Although I often spot errors in published books, I pick them up very randomly - as soon as I get engrossed I start missing them. You need someone who can painstakingly read the words. Proof reading is the minimum - you may also want to pay someone to do a structural edit, looking at how the book works overall. I've done this for people in the past - I would say that sometimes they found it really hard to take criticism. There's no point paying someone to do this unless you are prepared to listen and potentially change the content or approach.

Once you have a typescript ready to go, getting it published through something like KDP is tedious and can look overwhelming when you start, but take it step by step and it's perfectly doable. You will need to get the text into the appropriate format, design a cover (or have one designed for you) and set up all the associated metadata, from a blurb to pricing structure.

One small piece of advice on layout I got from a pro - you can pretty much use the same manuscript format for both paper book and ebook, but move the page with the copyright details to the end for the ebook. From my own experience, I'd always get a printed proof before publishing and check that over as well as you can. For the metadata (and cover design), look at what's on the Amazon listing of equivalent books from publishers. Get all the information you need together ahead so you can just paste it onto the KDP pages.

For cover design, I wouldn't put anyone off designing their own, but bear in mind that it's not something we're all good at. Look at plenty of equivalent book covers and see what works at a general level. I'm not suggesting copying them, but you should get a feel for what's in fashion for layout, font and use of colour. I see so many self-published books where the covers are very obviously DIY, and that's not a great start. It's worth having a play with one of the AI image products such as DALL-E or Bing Image Creator. They may give you a good starting point for a cover design. Remember if you are doing a paper book (I recommend having both paper and ebook formats) that you will need a back cover as well. KDP gives templates for the layout of covers if you don't use their clunky built-in designer (I prefer to do it separately). Again look at what's on the back covers of similar titles online or in a bookshop.

You will have to choose prices for each market, and have the option of whether or not it's widely distributed in at least the UK and the US (i.e. available wider than on Amazon). I'd keep the pricing relatively low to start with - you can always tweak this - but not so low that it looks not worth it. If you are use to academic markets but are writing for a more general one here, bear in mind that people don't generally pay as much for books in the general market - again, look at how the competition is priced.

Eventually you will have a published title. Now the hard bit starts. Most self-published books sell tens of copies, primarily to friends and relations. This may be all you want - fine. But if you want a wider audience you need to make your book visible. Use social media if it's available to you. Email contacts you think might be interested. Put together a press release - a one page document that sells the book which is a bit like the summary page of your proposal, but with more blurb-like selling material in there. Send this to all local media and any larger media outlets where you have contents.

Look to get reviews from appropriate bloggers. It will be hard - I do review self-published books on www.popularscience.co.uk, but rarely. Like most reviewers, I tend to use a publisher as a first line of defence, so there needs to be something quite special about a self-published book. Given we're talking non-fiction, the self-published books I wouldn't even consider is where someone has come up with their own scientific theories. Most reviewers will have stronger selection criteria for self-published than other books.

That apart, if you want it to be a real success, you need to put a huge amount of effort into marketing. Are there opportunities to sell your book by giving talks or attending events etc? If this is your aim you have to be shameless about self-publicity. But it's also important you do it right. I know some self-published authors who bombard everyone with social media posts that are all basically 'buy my book' - this will put people off. Make sure you aren't repeatedly hitting the same audience with the same message.

Don't let me scare you off. I really enjoy doing my self-published books, even though I know perfectly well they are likely only to have sales numbers in three figures. And some self-published titles go on to do extremely well - but bear in mind that these are very much the exceptions and usually involve a huge amount of self promotion.

I hope this series has been useful. I'll be doing another one in a while on the writing part of a non-fiction book - do use the link below to subscribe to my articles to get a heads-up. In the meanwhile, enjoy your writing experience.

To finish, here's an outline of the topics this series of posts will cover.

Is my idea a book? Outlining Other parts of a proposal The pitch letter Finding a publisher (or agent) The contract Publicity (and extra earnings) Self-publishingSee all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

April 25, 2023

Murder Before Evensong - Richard Coles ***(*)

A novel by a celebrity is almost always one I would avoid at all costs, as we all know why the publisher wants their name on the cover. It's all about marketing opportunity and nothing to do with writing skills. However, because Richard Coles' other profession as an Anglican clergyman made him ideally suited to writing a church-set murder mystery, I overcame my natural avoidance, and on the whole I'm glad that I did.

A novel by a celebrity is almost always one I would avoid at all costs, as we all know why the publisher wants their name on the cover. It's all about marketing opportunity and nothing to do with writing skills. However, because Richard Coles' other profession as an Anglican clergyman made him ideally suited to writing a church-set murder mystery, I overcame my natural avoidance, and on the whole I'm glad that I did.After reading eight chapters without a hint of murder, I thought Coles was doing an inspiring job of portraying life in a village parish from the 1980s, when an archaic location, that still had local church politics dominated by the lord of the manor, was struggling to come to terms with the (then) present. (There's even a knowing reference to the hit TV show of the period, To the Manor Born.) And, of course, Coles has the church life (and the vicar's outlook on life) perfectly illustrated. It's far more realistic than the portrayal of a vicar in a standard crime novel (though not, of course, my own Stephen Capel mysteries). If you extracted the crimes, to be honest, this novel would stand up well as an enjoyable exploration of that very particular setting.

If anything, the murder mystery part is the weakest aspect of the book. The plotting is more than a little contrived and it's quite difficult to keep track of the secondary characters who eventually come to the fore. I couldn't help think that if Agatha Christie had written this, we would get a real shock from whodunnit - here, the feeling is more 'Oh, okay. Fine.' It's the antithesis of Janice Hallett's amazing books, starting with The Appeal, where the plotting is phenomenal and hits you between the eyes.

Because I enjoyed the setting, both in terms of the life and thoughts of the central character of the Reverend Canon Daniel Clement, and this transitional world of the 1980s when the UK was undergoing a significant culture shift, I will be going back for the second instalment - I just hope that with practice Coles can make the detective aspect more engaging.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can buy Murder Before Evensong from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

April 19, 2023

I want to write a non-fiction book - part 7 - Publicity (and extra earnings)

In the next in my series on writing a non-fiction book (see outline at the end), I've skipped a rather big part: actually writing the book. The reason is it's such a big part, I think it's worth a series of posts in its own right. But our assumption here is you've written the book and it has been published. Between finishing your manuscript and this key moment will have been a lengthy period - typically 6 to 18 months - when the book will have been edited, proof read, typeset (obviously, not literally involving type setting anymore) and produced.

In the next in my series on writing a non-fiction book (see outline at the end), I've skipped a rather big part: actually writing the book. The reason is it's such a big part, I think it's worth a series of posts in its own right. But our assumption here is you've written the book and it has been published. Between finishing your manuscript and this key moment will have been a lengthy period - typically 6 to 18 months - when the book will have been edited, proof read, typeset (obviously, not literally involving type setting anymore) and produced.You might hope that the publisher would deal with the hands-dirty business of marketing your book. You're a writer (or a professional doing a bit of writing on the side). It's not your job. But the reality is that most publishers will only pull out the stops for a handful of books each year. You aren't going to get posters on the Tube or adverts in the newspapers. In fact these days, it's quite hard even to get a review, because books are not reviewed as much as they used to be. So if you want your book to have the best chance of selling well (which also means the best chance of getting lucrative translations), and you contract is of the advance and royalties type (see part 6) it's in your best interest to do what you can within reason to help.

There are broadly four contributions you can make. You can give interviews, give talks, write pieces accompanying the book for, say, newspapers, magazines and websites, and you can do a couple of the things that publishers ought to do, but some aren't very good at.

We'll come back to that last bit, but of the other three, personally speaking I feel that if I'm going to put in the time to give a good talk or write an article, I expect to be paid for it. I'm a professional; writing is my job. We'll start with talks. All too often, literary or science festivals will expect you to do a talk for the 'exposure'. Strangely, they don't expect their venues or caterers or sound people to do the job for 'exposure'. Because they know it won't work. But authors - the only reason they can have the festival or event - can feel embarrassed to ask for payment. If you are going to give a good talk you will typically spend several days preparing for it, plus the time to get to the venue and give the talk.

At the very least they should offer travel expenses and overnight accommodation if necessary. But I think either a percentage of the take or at least a £100 fee is a fair minimum to ensure that you are being treated professionally. Like all such rules, there are exceptions. For example, in the UK science writing world there are no venues more prestigious than the Royal Institution. They don't pay a fee - but I would never turn them down. The same may well apply, for example, to the Hay Festival, the UK's biggest book festival, which only pays celebrities. There's a balance to be struck.

In the same way as being asked to be a public speaker for nothing, if you are asked to write, say, a 1,000 word article about the same topic of your book, you are being asked to act as a freelance journalist. Most newspaper and magazines will pay for this if asked - while you might argue there's a small benefit of publicity, it's only fair that they pay a reasonable fee.

Interviews are different, though. You can't expect to be paid for these, but they don't require a lot of preparation or effort, so personally I'm happy to do them.

Some will enjoy this stuff. I love giving talks - arguably more so than writing books. But I know that others consider the whole business a horrible chore. It's a matter of achieving a balance of what you are prepared to do. Some contracts specify that you are to be able for, say, a week after publication, in which case that's a minimum you should go along with (though in practice it's rare that all the publicity fits in the specified period).

Finally we get to the 'what can I do that publishers probably ought to do.' If you'd like to do local publicity, publishers often don't bother with your local radio/newspaper, which will almost always be prepared to do a quick interview or a piece mentioning your book. Because newspapers run very few reviews these days, you can increase your visibility by getting your book onto a book review blog, like my own www.popularscience.co.uk - while some publishers will do this, you can probably find more opportunities than the publisher, as they will just use whatever their 'usual suspects' are.

Some authors go even further and pay for a publicist on top of the publisher's publicity efforts. I know of at least one author who spent his entire five figure advance on a publicist. The book certainly did well, though of course it may have done so without the money being spent. If you are trying to make a living as an author, unless you are independently wealthy, this is off limits. You need that advance to put bread on the table. But if you have a day job and are an author on the side, it may be worth trying. The main thing is to really research your publicist - there are plenty of people out there who will take your money and give you nothing of great value in return. Make sure the publisher is in the loop on this.

One last point. Many publishers give you a lengthy author questionnaire to fill in ahead of publication. This is a totally tedious task. But they do give your publisher's publicity people a strong foundation to build on. So face the pain and do a good job with them.

To finish, here's an outline of the topics this series of posts will cover.

Is my idea a book? Outlining Other parts of a proposal The pitch letter Finding a publisher (or agent) The contract Publicity (and extra earnings)Self-publishingSee all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

April 18, 2023

Is commercial art more at threat from AI than writing?

There has been quite a fuss from us writers about AI-based writing software in the form of chatbots such as Chat-GPT and Bard. However, equally impressive and insidious are the AI-created visuals from DALL-E and Bing Image Creator.

There has been quite a fuss from us writers about AI-based writing software in the form of chatbots such as Chat-GPT and Bard. However, equally impressive and insidious are the AI-created visuals from DALL-E and Bing Image Creator.The image at the top of this piece was created by DALL-E in response to the request from a friend for a picture of people picnicking in the churchyard of a medieval church in the style of Van Gogh. Now, admittedly the style is more a generic impressionist, but it's hard to argue this isn't an attractive image.

I don't think there is much threat to 'true' art. I asked my daughter, Rebecca Clegg, who is an artist - she commented:

I think AI provides both opportunities and challenges to artists. On one hand, AI could help generate an artwork that an artist would find difficult to create by hand, but it brings into question who owns the right to the artwork. Is it the artist who inputs the information or the AI? Or even the person who created the algorithm. Also would an algorithm not be limiting?

AI can help in the initial stages of ideas and support the inspiration and creation of maybe mathematically complex designs that would be difficult for an artist to produce. This helps the artist be more efficient in the production of their work as well as providing concepts not yet considered by the artist. The artist can also discern and chose between various images generated by AI and consider the limitations and applications of them as a design, I am not sure if AI knows what a good piece of art is compared to a bad piece of art?

Also art is not just about creating a visually appealing piece, its about conveying emotion and ideas on a deeper level pulled from the complexity of the human experience. AI does not have the emotional intelligence to create artwork that would resonate with an individual as it lacks unique experiences and perspectives, or even cultural backgrounds that an artist would draw inspiration from.

AI-generated art may be impressive and can help produce 'art' at a greater rate than an artist could, however it will never take away from the hand of the artist. The techniques and processes that take years to learn and perfect in particular mediums lead to unintentional, intuitive experiments, happy accidents, individual artistic expression and ultimately a signature that is unable to be replicated by AI.

AI-generated art may be impressive and can help produce 'art' at a greater rate than an artist could, however it will never take away from the hand of the artist. The techniques and processes that take years to learn and perfect in particular mediums lead to unintentional, intuitive experiments, happy accidents, individual artistic expression and ultimately a signature that is unable to be replicated by AI. I think what Rebecca says is true. However, she is mostly considering fine art here. And even there, arguably there is a potential for the intrusion of AI, as witness the recent win of an AI image in a prestigious photography competition. In reality, though, I suspect most professional artists are employed in commercial art fields, whether it's designing greetings cards, web imagery or even illustrating comics. For me, these are the areas where AI-generated images could pose a significant threat to employment.

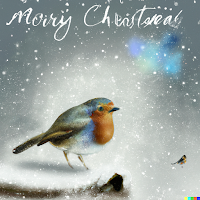

The two Christmas cards shown here were produced by DALL-E in a few seconds as a result of asking for a Christmas card with a robin in snow (above) and the same but in the style of an impressionist painting (right). It might not be great art, but I think both are just as good as plenty of the greetings cards I've seen (and bought).

The two Christmas cards shown here were produced by DALL-E in a few seconds as a result of asking for a Christmas card with a robin in snow (above) and the same but in the style of an impressionist painting (right). It might not be great art, but I think both are just as good as plenty of the greetings cards I've seen (and bought).Similarly, fellow science writer Andrew May, who has an interest in the weird and wonderful Charles Fort, decided he'd experiment with Bing Image Creator to produce a comic-form introduction to some aspects of Fort's work, shown below (click on the images to see the impressive level of detail). He does note that 'One weakness of Bing at the moment is that it can't give you any consistency from one image to the next (which is why I picked the concept for my comic to minimize the need for continuity, and why Fort changes his appearance from one panel to the next).'

I've read quite a few graphic novels and graphic novel-style science books, such as

The Phantom Scientist

,

Prime Suspects

and

Mysteries of the Quantum Universe

. Many of these have, frankly, distinctly mediocre illustrations. I think that Andrew's comic pages are better quality than the real thing in some of these cases.

I've read quite a few graphic novels and graphic novel-style science books, such as

The Phantom Scientist

,

Prime Suspects

and

Mysteries of the Quantum Universe

. Many of these have, frankly, distinctly mediocre illustrations. I think that Andrew's comic pages are better quality than the real thing in some of these cases.Of course there are limitations here, both in the lack of consistency that Andrew mentions and in the reach of the AI: apparently, he had to specify what Fort looked like as Bing was unable to produce even a vague resemblance to Fort's distinct appearance, despite plenty of imagery online. Even so, these examples do demonstrate that commercial artists have something to worry about.

This kind of software has advanced extremely quickly in recent years and even months. For a long time, fears about AI replacing human activity has been overheated. But there is no doubt that it has the potential to replace some human activity, doing the same thing better and cheaper, just as, for example, computer typesetting displaced manual typesetting. I take Rebecca's point that AI 'art' is arguably not of the same level as the best human art - but this is also true of much commercial artwork, and as the photograph competition demonstrates, quality in art is both subjective and subject to interpretation of things that aren't actually there.

It is already clear that it is dangerous to put AI in charge of decision-making. The kind of bias and errors produced by invisible and unexplainable AI 'logic' in everything from deciding whether or not to issue a bank loan to crime prevention and the rating of teachers has been highlighted in books such as Cathy O'Neil's

Weapons of Math Destruction

. The problems there don't mean that AI can't be involved in the grunt work supporting decisions, but that it should only be employed if it can explain why a particular result was reached and if a human being is able to override its decisions.

It is already clear that it is dangerous to put AI in charge of decision-making. The kind of bias and errors produced by invisible and unexplainable AI 'logic' in everything from deciding whether or not to issue a bank loan to crime prevention and the rating of teachers has been highlighted in books such as Cathy O'Neil's

Weapons of Math Destruction

. The problems there don't mean that AI can't be involved in the grunt work supporting decisions, but that it should only be employed if it can explain why a particular result was reached and if a human being is able to override its decisions.Similarly, all the evidence is that it's dangerous to leave AI in charge of writing a piece of text without oversight as it can both be in error (as I discovered when trying the approach on a couple of science writing issues) and is quite capable, for instance, of inventing citations.

However, things are less clear with the whole business of commercial illustration. Here, perhaps, there is often less concern about accuracy. Could it be that this is the first clear instance where this kind of technology will soon have totally transformed an industry?

I'm no artist (Rebecca will definitely agree with that statement), but like most people, to conform to the cliché, I know what I like. And it's people like me, not necessarily professional art experts who buy most artwork. If I'm honest, I'm not sure that we will be able to distinguish that human touch that may signify great art.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here