Brian Clegg's Blog, page 15

April 22, 2024

The Night in Question - Susan Fletcher ***(*)

This is a bit of an oddity - it was given to me on the assumption that it is a mystery so I would like it, and there is a mystery element, but the main focus (and certainly the best part) involves an 87-year-old woman looking back over her life.

This is a bit of an oddity - it was given to me on the assumption that it is a mystery so I would like it, and there is a mystery element, but the main focus (and certainly the best part) involves an 87-year-old woman looking back over her life.Florence Butterfield is a woman from an ordinary background, but who has an extraordinary life, which is dipped into through her memories in a non-linear fashion. Susan Fletcher is clearly adept at this kind of writing, handling it well and giving Florrie some remarkable events to remember, through to the point when due to an unlikely accident with mulled wine she ends up losing a leg, in a wheelchair and moving into the assisted living part of a care home, where the key event of the mystery takes place at midsummer. The manager of the home, Renate, plummets from her third floor window with Florrie as the only witness. The manager's life is on a thread in a coma, and the assumption is made that it was a suicide attempt. But Florrie is not sure.

Here's where the mystery element comes in - or at least one of the two mystery elements. The other is that there is something nasty in the woodshed from when Florrie was 17 that is hinted at every few pages for nearly all of the 400-page book. Frankly, this teasing of what happened gets tedious. The main mystery is more interesting - was Renate pushed, by whom and why? But I'm afraid this part of the book does not play to Fletcher's strengths. The two key twists in the plot were reasonably obvious: in the first case, Florrie and her Dr Watson-like friend draw entirely the wrong conclusion from a clue, even though the reality is readily apparent. In the second, they fail to notice a totally straightforward possibility. As far as I can see, the only reason for the apparently bright Florrie missing these points for so long is that the book wouldn't be long enough to fit in all the reminiscing otherwise.

I quite enjoyed The Night in Question, though during some of the diving into the past I did feel 'Please, let's get back to the mystery.' - but if you enjoy an 'extraordinary and unexpected life slowly revealed' novel and aren't too worried about the mystery side, this would very satisfactorily hit the spot.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can buy The Night in Question from Amazon.co.uk Amazon.com and Bookshop.org

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

Monte Carlo or bust (Monte Carlo Method, part 4)

This is the final post on the mathematical approach known as the Monte Carlo method, following 'Generating random numbers.'

This is the final post on the mathematical approach known as the Monte Carlo method, following 'Generating random numbers.'We have seen in previous posts why the method is named Monte Carlo, how it was first used and the difficulties of obtaining a stream of truly random numbers. This approach is now used across the sciences, as well in engineering, economics, AI and more. It's an technique that comes in useful when there is a complex mathematical problem solve, where taking repeated random samples of weighted possible outcomes will give a better understanding of a real world situation.

There are far too many applications to go into detail here (you can find a length set of possibilities in the Wikipedia entry). To see a simple one in action, take a look at this Monte Carlo-based pi generator. But I just want to pick out another application that I'm particularly familiar with from using it to help understand queues in an airport terminal. I've always thought that queuing is one of the most fascinating aspects of Operational Research, which I worked in for a good few years. Apart from anything, this is because queues involve people, and the way that people interact with each other.

Anyone who has visited theme park rides in different countries may well have experienced varying cultural approaches to dealing with a conventional single line queue, from polite fairness to 'cram in and try to get in front'. But things get more interesting when there are multiple servers. Once upon a time there would typically be an individual queue for each server. This is still often the case, for example, with supermarket trolley checkouts and airport passport checks. But in many cases, it is more effective to have a single queue feeding all the servers, where the person at the front goes to the first available server.

It's not long ago that such queuing systems were treated with suspicion: since the single queue is much longer than any one of the individual queues it replaces, it looks like it will make waiting time longer. But it doesn't in many circumstances. Usually when we want a single queue multiple server setup we corral people to make it easier to see what's happening. With no enforced structure, for example, at a row of several busy cash machines you usually see a queue forming behind each dispenser - though I was delighted a few years ago (when I used to use cash) to see a spontaneously formed single queue, multiple server arrangement developing as people held back from cashpoints and let the first person go to whichever became free.

There are times, though, when the intuitive setup may not be the most effective - and this is where a form of Monte Carlo Method comes in, in the form of simulation. (Some pedants don't include simulation as Monte Carlo, but I disagree, and it's one of the easiest examples to get your head around.) When I did this, I manually coded it, though for many years now you have been able to use off the shelf simulation packages. After collecting data on the distribution of times a transaction takes, which depends on the complexity of the interaction (e.g. the number of items in a shopping trolley, the number of bags and options in a check-in, or the complexity of a bank transaction ranging from a simple deposit to setting up a new account) plus the flows of customers at various times, the simulation makes use of random number generation to control both the availability of servers, the arrival of customers with different transactions, and their queue selection if there is more than one queue.

This is then run as a simulation, a bit like a self-playing video game, churning through a virtual day over and over to build up an effective picture of what is likely to happen. The same approach can then be taken with variations in the queuing layout, making it possible to provide the best structure of queue(s) for the particular requirement.

I had many a happy hour looking at queuing possibilities for Heathrow's Terminal Four (don't blame me if the queues don't work now - this was many years ago and the queuing structures/airline usage have changed several times since). It was a delight to be putting (pseudo-) randomness to good use.

Image from Unsplash by Lisanto

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

April 19, 2024

A week of fantasy TV

Having recently had a week with sole charge of the TV remote, I've taken the opportunity of catching up on a couple of new series in my favourite fantasy sub-genre. I'm not a fan of swords and sorcery (with the noble exception of Lord of the Rings), but I love what you might call real-world fantasy. This is pretty much the same as urban fantasy, but doesn't have to be in a city. You could also see it as magical realism without the pretentiousness.

Having recently had a week with sole charge of the TV remote, I've taken the opportunity of catching up on a couple of new series in my favourite fantasy sub-genre. I'm not a fan of swords and sorcery (with the noble exception of Lord of the Rings), but I love what you might call real-world fantasy. This is pretty much the same as urban fantasy, but doesn't have to be in a city. You could also see it as magical realism without the pretentiousness. The idea, then, is to incorporate fantastical occurrences in the normal world. The first example of this was ITV's Passenger. This sets what should be a normal police procedural story in a weird village (Chadder Vale) in Lancashire. There are strange occurrences, some sort of unexplained dangerous creature and a cast of misfits. As such, you can see it as a mix of Twin Peaks, Stranger Things and Happy Valley.

Perhaps the weirdest decision by Andrew Buchan, the man behind the series, is to set the show in the present, but to emphasise Chaddar Vale's oddness by having various aspects of life there stuck in the past. The the police use a Mini Metro patrol car, the computer game we see, played on a console, is blockily retro, and mobile phones are of the ancient variety. Perhaps influenced by Twin Peaks, there are also some decidedly American aspects to the look of the place (even though the natives speak broad Lancashire). For example, the police uniforms look to be from the wrong side of the Atlantic. Standout performance is from Wunmi Mosaku as the police detective whose boss is more interested in her finding stolen wheelie bins than solving a murder.

The series develops a good sense of dark, brooding atmosphere and attempts a touch of humour, mostly in the dialogue and the incompetence of some of the characters. This all works well, but I'd argue that it's too slow to get anywhere - and it ends in a way that demands a second series, which I'm not sure it will get. Admittedly, if there is going to be one, then the ending is okay, but it does leave everything open and much unexplained. It would have been better to have tied it up more, while still leaving room for new directions. I'm glad I watched it, but I can understand why some were frustrated by the ending. Take a look on ITVX.

The second new series on the block was Disney+'s Renegade Nell by the excellent writer Sally Wainwright. This is a different form of the genre - it could only be called real-world fantasy if Bridgerton can be considered to reflect historical reality (hint - it doesn't). Set in England in the early 1700s, it doesn't attempt period speech, and the cast is colour blind - it works fine, but the result is to reduce the cognitive dissonance of the clash between the fantasy element and the normal world (because the world isn't normal for 1700), which is why real-world fantasy works so well.

The second new series on the block was Disney+'s Renegade Nell by the excellent writer Sally Wainwright. This is a different form of the genre - it could only be called real-world fantasy if Bridgerton can be considered to reflect historical reality (hint - it doesn't). Set in England in the early 1700s, it doesn't attempt period speech, and the cast is colour blind - it works fine, but the result is to reduce the cognitive dissonance of the clash between the fantasy element and the normal world (because the world isn't normal for 1700), which is why real-world fantasy works so well.The central character, Nell, is a poor inkeeper's daughter who gets her own back on the toffs by becoming a highwaywoman, attempting to avenge her father's murder and getting embroiled in various plots while trying to keep her younger sisters safe. So far, so straightforward pseudo-historical. But Nell is helped out by a fairy-like character who can give her superhuman strength, while the dodgy lord-of-the-manor's dim son and scheming daughter hook up with a magician lord in the Privy Council, played magnificently by Adrian Lester. And why not throw in Herne the Hunter too?

Nell is played well by Irish actress Louise Harland, while comedian-turned-actor Nick Mohammed employs his trademark naivety to provide an entertaining turn as the fairyoid, Billy Budd. In one sense this is a natural step forward by Wainwright from her Victorian series Gentleman Jack - it's another show with a strong female lead who thwarts the convention of her period and Harland is more effective than the usually excellent Suranne Jones who is far too mannered as Gentleman Jack, seeming to spend half her time running from one place to another.

Renegade Nell is an oddity for Wainwright who, as a writer, is steeped in the North of England, but here the setting is primarily the Thames Valley, featuring key locations of London (including the village of Tottenham), Slough and Uffington - but it's necessary because of the need to bring in Queen Anne and her key advisors. Despite the pseudo-historical setting, I enjoyed it more than Passenger because there was considerably more action, significantly more plot development and more of a sense of fun, despite the dark context. Worth catching up with if you have Disney+ (though probably not worth subscribing just to watch it).

One thing Disney+ would also give you is access to the the greatest urban fantasy TV show of them all, Buffy the Vampire Slayer - to top off the fantasy week, I watched two of the classic Buffy episodes, Hush and Once More with Feeling.

One thing Disney+ would also give you is access to the the greatest urban fantasy TV show of them all, Buffy the Vampire Slayer - to top off the fantasy week, I watched two of the classic Buffy episodes, Hush and Once More with Feeling. More than half of Hush (from Season 4) has no speaking at all as a spell renders everyone in Sunnydale speechless to enable horrific attacks without the victims being able to cry for help. Despite the distinctly nasty baddies, this provides for some excellent humour, particular during a briefing using overhead projector slides and some unfortunate mime.

Once More with Feeling seems like it should be a much lighter episode, as it's a musical where characters repeatedly burst into song to expound various feelings - though unlike traditional musicals, there is a logical explanation for this random song and dance in the form of a meddling demon with a nefarious purpose. There is still a surprising amount of humour, despite this being from the mostly miserable-toned series 6 (the reason for the misery is finally explained to the rest of the cast in a song performed by Sarah Michelle Gellar featuring some interesting atonality). I'd forgotten the ending, which as often is the case with Buffy defies expectations.

Although now 20 or so years old, Buffy still holds up surprisingly well - especially when revelling in the cleverness of these episodes. What comes across immediately is the sharp dialogue and the depth of humour. (One specific delight I'd forgotten is Anya's suggestion that the cause of the musical outbreaks might be bunnies.) The whole point of the series is to subvert the horror show stereotype by having a strong female character as the vampire slayer, rather than the female lead being a helpless victim - and these two episodes make good use of this feature. Although Passenger and Renegade Nell both had a degree of subversion, neither came close to Buffy's ability to combine a continuous thread of humour with dark topics.

If you have never seen Buffy, it has yet to be toppled from its top spot.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free hereApril 15, 2024

Expecting the unexpected - generating random numbers (Monte Carlo method, part 3)

This is the third of four posts on the mathematical approach known as the Monte Carlo method, following 'Where did those neutrons go'.

This is the third of four posts on the mathematical approach known as the Monte Carlo method, following 'Where did those neutrons go'.As we saw in the previous post, the Monte Carlo method depends on having a stream of random numbers. Unfortunately, randomness is not easy to generate. Ask someone for a series of random choices between 1 and 10 and they will not do well - for example, there won't be sufficient repeated values for a true random stream. In another extract from my book Dice World, let's take a look at what appears to be random whether we use a spreadsheet or a more sophisticated source:

In Excel I have two random number functions, RAND, which gives me a random value between 0 and 1 (I just got 0.61012053) and RANDBETWEEN to choose a random number in a range. (My value for between 1 and 10 came out as 4.) Job done. Unfortunately, what Excel gives us is not random numbers, but pseudo-random numbers. Numbers that are random enough for, say, making a prize draw, but that aren’t good enough if you want a good long sequence of numbers that are truly random.

That is because the pseudo-random number generator is not genuinely picking between the options with equal probabilities, nor is any value in a sequence of numbers it generates totally independent of what came before. That has to be the case or we can’t calculate the random number using some sort of computer algorithm. A spreadsheet’s pseudo-random generator usually starts with a ‘seed’, an initial value which is often taken from the computer’s clock, and then repeatedly carries out a mathematical operation, typically multiplying the previous value by a constant, adding another constant and then finding the remainder when dividing by a third constant. So, for instance, a crude pseudo-random number generator would be something like:

New value = (1,366 × Previous Value + 150,899) modulo 714,025

where ‘modulo’ is the fancy term for ‘take the remainder when you divide it by ...’ The output of the pseudo-random number generator wanders off away from the seed value and can be reasonably convincing in appearance, but it will always produce the same values given the same seed, and can’t match a true random number generator for effectiveness of results. Although my Excel RANDBETWEEN function can produce two repeated values, because it is rounding a wide range of real number values to get to the same figure, the pseudo-random generator will still always be limited because it can never produce the same exact value twice in a row or it would get locked into repeating that value over and over.

Those who want to be more careful about their randomness look for a better way of producing their outputs. Most large lotteries rely on machines with a series of balls in them, which are randomised by stirring them up before balls are drawn. This is not the best way of getting a random number by any means. It’s still a pseudo-random number generator. The chances of the balls being drawn in a perfectly random fashion are very low. But in this particular example, visibility is more important than perfection. It is considered more important for players to see the draw happening than it is to approach the perfection of true randomness.

This isn’t the case for all lotteries, though. In the UK, for instance, we have an unusual kind of lottery known as premium bonds. These are government bonds that allow the buyer to have a little flutter, instead of providing a predictable return for all purchasers, as is traditional with bonds. Most premium bonds will return no ‘interest’ (though unlike a lottery ticket they can be cashed in to get the initial stake back). But 1 in 24,000 of the £1 units wins a prize in each draw*. Some bonds will produce this cash return, which can vary from a few pounds to £1 million.

To make the draw fair, the people behind premium bonds were among the first in using electronic random number generation with a device known as ERNIE, a contraction of Electronic Random Number Indicator Equipment. This device was introduced in 1957, designed by Tommy Flowers, the man behind the world’s first electronic programmable computer, the Colossus, at the World War II code-cracking centre, Bletchley Park.

ERNIE worked by using the noise in the signal produced by a series of valves (vacuum tubes). All elec- tronic devices produce a degree of noise due to thermal variations in the materials, interference and other effects. Although not truly random, because the outcome could in principle be predicted if you had all the available data, no one has access to that data and the effect is sufficiently chaotic that it is impossible to have any idea what will come next. Because of this, it is a safer way to generate pseudo-random numbers than a software-based approach. More recent variants of ERNIE (they are on to Mark IV) make use of thermal noise in transistors.

True random values can be produced using quantum effects, and true random generators are now available to plug into electronic devices if required. For example, if you have a radioactive source, where atoms occasionally spontaneously emit part of their nucleus, you can predict how often an atom will undergo such a decay on average, but the decay of a specific atom is truly random: it is not just impractical to predict but is impossible because there literally is no cause. The modern-day ERNIE could be based on such a system, but the approach taken is equally good in terms of being unpredictable and is easier to produce.

With random numbers fed in, we will look at more modern uses of the Monte Carlo method in the final post.

* Since Dice World was written, the chances of winning with a premium bond increased to 1 in 21,000.

Image from Unsplash by Dylan Nolte

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can buy Dice World from Amazon.co.uk Amazon.com and Bookshop.org

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

April 8, 2024

Where did those neutrons go? (Monte Carlo method, part 2)

This is the second of four posts on the mathematical approach known as the Monte Carlo method, following 'Breaking the bank...'

This is the second of four posts on the mathematical approach known as the Monte Carlo method, following 'Breaking the bank...'Moving from the bank being broken at a casino to a mathematical method occurred as the Second World War came to a close. A number of scientists on the US nuclear programme were attempting to model neutron diffusion from a nuclear bomb. This was because a conventional nuclear explosion is effectively the trigger for the (then theoretical) thermonuclear explosion of a fusion bomb - and a major factor in its effectiveness is how neutrons travel out from the primary fission stage.

Like his colleague John von Neumann, the Polish-American physicist Stanislaw Ulam had an interest in the game of poker and the probabilistic nature of games. The new possibility of electronic calculation using the ENIAC computer made it possible to consider a novel approach to modelling neutron diffusion. At the heart of nuclear fission is the idea of a chain reaction. A neutron hits a nucleus, which splits, giving off more than one neutron. Each of these then has the opportunity to do the same. But predicting how such a process would occur, given the probabilistic nature of particle interactions, was a problem.

The idea behind the Monte Carlo method is to use the output of a (pseudo-) random number generator combined with known distributions of the chance of various interactions taking place to effectively simulate what is happening. By making many multiple runs of the model, an an accurate probability-driven picture is built up. This approach became widely used in a whole range of simulation applications - for instance predicting what would happen over time in complex queuing systems.

Ulam claimed to have come up with the idea while recovering from a serious illness, playing a variant of the card game solitaire (patience). He realised that it would take considerable mental effort to work out the chances of succeeding in any particular attempt. But if, instead, the game was repeatedly played - say 100 times - the percentage of successful plays would converge on the actual probability. He described this idea to von Neumann and began work on it with him.

Perhaps surprisingly, neither of these enthusiastic game players thought up the name. Greek-American physicist Nicholas Metropolis claimed to be responsible, writing 'It was at that time [early 1947] that I suggested an obvious name for the statistical method - a suggestion not unrelated to the fact that Stan had an uncle who would borrow money from relatives because he "just had to go to Monte Carlo." The name seems to have endured.' Initially it was a code name, but it became one of mathematics' more entertainingly named methods.

To make such simulations effective there needs to be a source of random(ish) numbers - but how was that to be achieved? We will look into those in more detail in the next, penultimate post.

Main source The Beginning of the Monte Carlo method by Nicholas Metropolis in the 1987 Los Alamos Science special issue.

Image from Unsplash by Hal Gatewood

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

April 3, 2024

Breaking the bank at Monte Carlo (Monte Carlo method, part 1)

This is the first of a couple of posts on the mathematical approach known as the Monte Carlo method.

This is the first of a couple of posts on the mathematical approach known as the Monte Carlo method.I want to start gently by taking a (virtual) trip to Monte Carlo in Monaco and its famous casino, specifically to explore a once well known phrase - the man who broke the bank at Monte Carlo. The article below is extracted from my book Dice World.

A roulette wheel is a physical device, and as such is not a perfect mechanism for producing a random number between 1 and 37 (or 38 in the more money-grabbing US casinos). Although wheels are routinely tested, it is entirely possible for one to have a slight bias – and just occasionally this can result in a chance for players to make a bundle. It certainly did so for 19th-century British engineer Joseph Jagger, who has, probably incorrectly, been associated with the song ‘The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo’, which came out around the same time as Jagger had a remarkable win in Monaco. The song probably referred instead to the conman Charles Wells, who won over a million francs at Monte Carlo and did indeed ‘break the bank’. (This doesn’t mean that he cleaned out the casino, simply that he used up all the chips available on a particular table.) There were many attempts to find how Wells was cheating, but he later admitted that it was purely a run of luck, combined with a large amount of cash enabling him to take the often effective but dangerous strategy of doubling the stake on every play until he won.

However, Jagger probably deserves the accolade more than Wells, as his win was down to the application of wits rather than luck – and was even more dramatic. Jagger finally amassed over 2 million francs – the equivalent of over £3 million (or $5 million) today. He hired a number of men to frequent the casino and record the winning numbers on the six wheels. After studying the results he discovered that one wheel favoured nine of the numbers significantly over the rest. By sticking to these numbers he managed to beat the system until the casino realised it was just this wheel that was suffering large losses and rearranged the wheels overnight. Although Jagger soon tracked down the wheel, which had a distinctive scratch, the casino struck back by rearranging the numbers on the wheel each night, making his knowledge worthless.

Incidentally, I have always found it bizarre that casinos consider it to be cheating if players use skill to win. Unless there is a fault with the wheel, there is no skill in roulette, but there certainly can be in games like blackjack, where there are a limited number of cards available to play, and so by counting the cards that have already been dealt, a player with a superb memory (or a concealed computer) can increase their chances of winning. Apparently you get thrown out of casinos if you are caught doing this and barred from re-entering. Imagine if athletes were banned from their sport if they showed any sign of skill. It just demonstrates what should be obvious: casinos aren’t a way of playing fair games, they are businesses designed to take money off people.

Image from Unsplash by Derek Lynn

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can buy Dice World from Amazon.co.uk Amazon.com and Bookshop.org

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

April 2, 2024

Leave No Trace - Jo Callaghan *****

In Jo Callaghan's first book featuring Detective Superintendent Kat Frank paired up with a virtual AI detective called Lock,

In the Blink of an Eye

, it was arguably the science fiction aspect that came to the fore - but the (arguably better) sequel focuses more on being an excellent police procedural crime novel.

In Jo Callaghan's first book featuring Detective Superintendent Kat Frank paired up with a virtual AI detective called Lock,

In the Blink of an Eye

, it was arguably the science fiction aspect that came to the fore - but the (arguably better) sequel focuses more on being an excellent police procedural crime novel.Frank and Lock have been moved from cold cases to a frontline murder that rapidly becomes a national news story - the victim has been crucified. (I don't know if the release of the book was timed intentionally, but I read it over Easter.) Tension mounts as a second crucified body is found - while the team is still thrashing around trying to find a viable suspect.

Where in the first book, Lock (and people's reaction to his holographic presence) featured heavily, here he becomes significantly more part of the team, and we see not only his limitations, but some consideration of how much he should be considered a conscious entity. If anything, his abilities are slightly under-utilised. There is also a little less focus on Frank's home life, which was central to the first novel, allowing the police procedural aspect to come more effectively to the fore. With an impressively structured case to solve, this made for an engaging and intriguing plot.

Leaving aside the technical limitations a real Lock would face - which are fine to make the story work - the only thing I thought was a little odd was that an early potential motive was religion, and at one point we have a suspect saying 'Christians aren't the only ones who used to crucify people'. While a religious motive could have been followed up (though it seemed to have dropped early on), in reality Christians would be much less likely to use this method of killing than anyone else.

I suspect some regular readers or viewers of crime stories would have spotted a couple of points ahead of the police team - but that is part of the appeal of reading this kind of book, where the puzzle of working out the who, how and why is just as important as exploring the human interactions along the way. With a dramatic against-the-clock ending, it's a book any crime lover will relish.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can buy Leave no Trace from Amazon.co.uk Amazon.com and Bookshop.org

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

March 25, 2024

The joy of sigma

Anyone who looks in a bit of detail at scientific results may have come across p-values and sigmas being used to determine the significance of a outcome - but what are they, and why is there a huge disparity between practice in the social sciences and physics?

Anyone who looks in a bit of detail at scientific results may have come across p-values and sigmas being used to determine the significance of a outcome - but what are they, and why is there a huge disparity between practice in the social sciences and physics?These are statistical measures that determine the probability of the results being obtained if the 'null hypothesis' is true - which is to say if the effect being reported doesn't exist. The social sciences, notably psychology, usually consider the marker for statistical significance to be a p-value of less than 0.05, while in physics the aim is often to have a 5 sigma result.

Both these measures depend on creating a probability distribution, showing the likelihood of different values occuring. The p-value is a direct measure of the probability of getting the reported results if the null-hypothesis applies. So, a p-value of 0.05 means there is one in twenty (1/20 = 0.05) chance of this happening. Sigmas effectively measure the same thing, but in terms of a statistical measure called standard deviation that shows how spread out the distribution is.

It might seem odd not to use the more straightforward p-value, but the reason that sigmas tend to be used is that the p-value equivalent becomes very small at the kind of levels physicists look for. CERN, for example, actually works with p-values, but converts them to sigmas for easier communication. Here's a look at equivalent values:

Sigma P-value Cliff measure

2 0.05 Whiff

3 0.003 Evidence

4 0.0001 Annoying*

5 0.0000003 Discovery

The 'Cliff measure' used above is a humorous interpretation of sigmas given by particle physicist Harry Cliff in his book Space Oddities. Arguably this is a more effective description of the value of different levels than the way statistical significance is usually regarded in the social sciences. Choosing 2 sigma/p-value of 0.05 as being statistically significant was an arbitrary choice, plucked out of the air by mathematician Ronald Fisher in 1925. However, it should be seen as nothing more than a note that something is worthy of proper investigation - Cliff's whiff - rather than an indicator that the outcome is accepted science.

Such has the focus been on getting a p-value below 0.05, there has in the past been a significant amount of 'p-hacking' - manipulating the data with the intention to get the result below the critical level. But Fisher certainly never intended this to be any sort of indicator of a real discovery. Remember, a p-value of 0.05 means that there is a 1 in 20 chance of getting these results when the effect doesn't exist. It may be a better probability than Russian roulette (p-value equivalent 0.17), but it's still hardly something you would want to risk your life on.

Why, then, is there such a disparity between the social sciences and physics? Because it isn't practical to have sufficient experimental subjects or experimental runs to come close to a 5 sigma outcome. It's very rarely going to be possible. As a result, the social sciences can't hope for equivalent degrees of apparent certainty. However, there is a strong feeling that the social sciences could do better - perhaps aiming for 3 sigma before they get excited. And it does mean that the outcomes of social sciences studies should arguably always carry a health warning and be better reported in terms of the risk of their misattributing an outcome to a particular cause.

One final consideration - even 5 sigma results can be wrong. Scientists can make a mistake with the maths. And there could be confounding factors too - a great example is the BICEP2 study, which aimed to study polarisation in the Cosmic Microwave Background radiation in the hope of finding direct evidence for the cosmological theory of inflation, which evidence as yet doesn't exist. BICEP2 did so at a 5.9 sigma level. Except it turned out that the results were being distorted by cosmic dust - it was not a discovery after all. There is always the possibility that scientists have not allowed for a factor they were not aware of that has distorted the results - something that sadly tends to disappear from popular science/news reporting where outcomes are often stated is if they were fact.

Probability and statistics can be hard to get our heads around - but when scientific results are reported, it is essential that this particular aspect should be carefully explained up front. To have confidence in scientific results, we need to know know what the limitations of a particular study are.

* Cliff's 'annoying' for 4 sigma is not saying it is useless, but rather than it's annoying it's getting close to the 'gold standard' 5 sigma without quite making it.

Image from Unsplash by Naser Tamimi

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free hereMarch 21, 2024

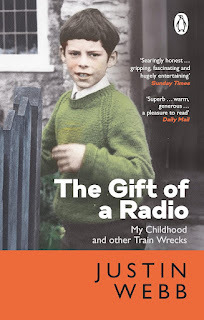

The Gift of a Radio - Justin Webb ****

This isn't the kind of book I usually read, but it piqued my interest when someone told me about it - and it certainly was worth getting into. If you are a BBC Radio 4 listener (or subscribe to the Americast podcast) you will be familiar with Justin Webb's soothing tones - this memoir of his childhood through to going to university gives a vivid picture of his bizarre upbringing.

This isn't the kind of book I usually read, but it piqued my interest when someone told me about it - and it certainly was worth getting into. If you are a BBC Radio 4 listener (or subscribe to the Americast podcast) you will be familiar with Justin Webb's soothing tones - this memoir of his childhood through to going to university gives a vivid picture of his bizarre upbringing.Webb never met his father (who would become a reasonably well-known BBC reporter), being brought up by his mother and stepfather, each of whom had quite serious problems. His stepfather had a form of mental illness that included paranoia, while his mother was intensely snobbish, insisting on every little social divider that would put a gap between her upper-middle-class-on-hard-times position and anyone she considered socially inferior.

Their home life seems to have consisted mostly of silence, though there was a strong bond between Webb and his mother, arguably an unhealthy one. He was then sent to a dire second-rate public school, run by Quakers who somehow ignored violence amongst the students, before finally escaping to the LSE and a job at the BBC (via one dramatic road trip disaster). It's one of those stories where it's almost impossible to prevent yourself from describing parts of his experience to anyone nearby in amazement.

One thing that comes across very strongly is how dire Webb considers the 1970s to have been I can't help but feel that his intense dislike for the decade reflects his personal circumstances. I'm just a little older than Webb, but I loved the seventies, where I was experiencing my last years at a school I liked, time at two universities which I loved and starting a great job. Of course there were political and economic problems in the 70s, but I think the experience of being a child or teenager then has far more to do with what you were going through as an individual than a dark nature of the decade as a whole.

If you aren't familiar with Webb's work, you can hear him here, interviewing me for Radio 4's Today Programme (somewhat ironically, given his admission to totally giving up on science at school):

Your browser does not support the audio element.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can buy The Gift of a Radio from Amazon.co.uk Amazon.com and Bookshop.org

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

March 19, 2024

Ghost singers

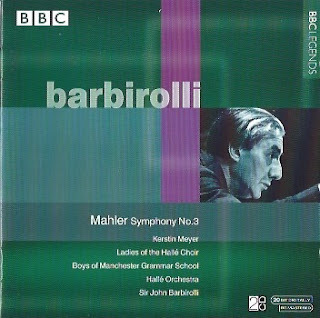

When I was 13, I sang in a performance of Mahler's third symphony with the Hallé Orchestra under Sir John Barbirolli. Our school's 'special choir' was a regular feature in Manchester performances of orchestral pieces with children's parts - amongst other outings, I sang in Stravinsky's Persephone, Verdi's Otello, Malcolm Williamson's Our Man in Havana and Mussorgsky's Khovanschina.

When I was 13, I sang in a performance of Mahler's third symphony with the Hallé Orchestra under Sir John Barbirolli. Our school's 'special choir' was a regular feature in Manchester performances of orchestral pieces with children's parts - amongst other outings, I sang in Stravinsky's Persephone, Verdi's Otello, Malcolm Williamson's Our Man in Havana and Mussorgsky's Khovanschina.We performed Mahler 3 a total of three times - concerts in at the Free Trade Hall and the Festival Hall, and a BBC recording for broadcast. But what I didn't realise until a few weeks ago was that the BBC had issued that recording as an album. I managed to get hold of a CD copy and had the eerie experience of hearing myself and fellow choir members from 55 years ago.

The (extremely long) symphony was quite a trial of patience for us. We had movement after movement marked 'tacet' on our copies, before featuring in the 4 minutes or so of the movement marked 'Lustig Im Tempo Und Keck Im Ausdruck'. Our part almost entirely consisted of singing 'Bimm bamm' (supposedly the sound of bells) with just a brief burst of German words. One of the choir was not allowed to return after spending much of the first movements on stage in full view of the audience reading a newspaper.

Even so, it was a remarkable experience for a young person, and hearing those youthful voices Bimm Bamming away, brought the memories flooding back.

I've extracted a couple of parts of the movement here, which I hope can be played as fair usage to show us in action:

brianclegg · Condensed Mahler 3 Movement 5

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here