Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 140

March 31, 2017

Good news for health-services research

Without fanfare, a rule restoring full research access to Medicare and Medicaid data has gone into effect. The rule had been adopted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Agency (SAMHSA) in the waning days of the Obama administration, but was placed on hold when President Trump took office. It apparently passed muster with the new administration, and a SAMHSA spokesperson has confirmed that the rule took effect on March 21.

This is good news for the research community, and a welcome end to a two-year battle to restore access to unbiased government data. The rule isn’t perfect: as I’ve discussed before, it appears to leave all-payer claims databases with no mechanism to receive data containing records about substance use disorders. But it’s a big step forward.

For those of you who have received scrubbed data from prior years, it’s not clear yet how quickly those data can be re-released in unscrubbed form. If ResDAC—the contractor that manages the research distribution of CMS data—has the unscrubbed data on hand, the rule now allows their release. If not, ResDAC will have to go back to CMS to secure the complete data sets.

March 30, 2017

The complications of House v. Price

I’ve got a piece at Vox discussing what happens next with House v. Price (formerly House v. Burwell), the litigation over whether Congress has appropriated the money to make cost-sharing payments.

To bring you quickly up to speed: a district court in Washington, D.C., concluded last year that the Obama administration was breaking the law in making the cost-sharing payments. The court entered an injunction prohibiting the payments; the injunction was then stayed pending appeal. The question for the Trump administration is what to do with that appeal.

I wanted to explain in non-legalese what the case is about and why it has insurers so worried. I also wanted to address the common assumption that the House of Representatives and the Trump administration could cut some kind of deal to keep the cost-sharing payments flowing. Even assuming that’s how both parties want to play it, the lawsuit will be a big headache.

The most straightforward fix would be for Congress to appropriate the damn money. That’s probably a nonstarter, given how many Freedom Caucus members would cry foul at funding Obamacare. Nor is it clear whether the Republican leadership is willing or able to broker a deal with Democrats.

If Congress won’t appropriate the money, the House and the Trump administration could try to bury the hatchet and settle the case. They might say, in effect, “We’ve agreed between ourselves to drop the lawsuit and that we’re better off without the district court’s injunction.” Now that the case is on appeal, however, it’s not so easy as that. The Supreme Court has said that appeals courts can’t overturn district court orders when parties settle their cases, even if both parties ask nicely.

So to get out from under the district court’s injunction, the parties may have to go back to the district court. But the court can modify its prior order only if there’s been a “significant change either in factual conditions or in law.”

Does Trump’s election qualify as such a “significant change … in factual conditions”? Perhaps. Certainly it would be strange to keep an injunction in place when no one on either side of the legal fight wanted it anymore. Judges don’t usually ask too many questions when opposing parties agree about something.

But still, there’s something fishy about the asking the court to vacate the injunction — and allowing the payments to proceed. Both the district court and the House of Representatives still believe (correctly, in my view) that it’s unconstitutional for the executive branch to keep making the cost-sharing payments. The Trump administration’s lawyers likely share that assessment. (Until recently, those same lawyers were raging about Obama’s lawlessness.)

The only reason to vacate the injunction, then, is because it’d be awfully convenient to keep making the cost-sharing payments — even though the judiciary, the executive, and the legislature all think those payments are unconstitutional. The judge might well balk. Indeed, she might be offended at the effort to enlist the federal courts in an unconstitutional scheme.

If I’m right about this, the best course of action for Trump administration and the House of Representatives might be to ask the D.C. Circuit to put the case on hold. But that will drive insurers crazy: the president could dismiss the appeal at any point, which would lead to chaos on the exchanges. Will insurers really stick around if the exchanges are that vulnerable?

March 29, 2017

Is the tax exclusion for employer-sponsored insurance regressive?

If you were to ask 100 randomly-selected health wonks, probably 92 would say that the tax exclusion for employer-sponsored insurance is bad policy. This is one of those issues on which liberal and conservative health economists agree. Liberal and conservative politicians agree with each other, too, though not in the way hoped for by economists. Policies to limit ESI tax exclusion seem politically radioactive, as indicated by the savage reception to candidate John McCain’s 2008 health proposals, and as indicated by the delayed implementation of the “Cadillac tax” on high-value employer plans enacted under ACA.

Politics aside, most experts would argue that the tax exclusion is regressive, that it subsidizes over-insurance for highly-compensated people, and that such hidden subsidies make health care costs further opaque, and therefore undermine cost-control policies. TIE’s own Austin Frakt observes that many of us receive greater tax subsidies from the ESI exclusion than is provided to the typical Medicaid recipient. My own taxes would be about $7,000 higher if I were fully taxed on my generous insurance plan. This massive tax subsidy to a tenured professor seems hard to justify on either equity or efficiency grounds.

Joseph White of Case Western challenges the conventional policy-wonk wisdom in a recent essay in the Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law: The Tax Exclusion for Employer-Sponsored Insurance Is Not Regressive—But What Is It?

White makes several seemingly-obvious but generally-overlooked points. Although the dollar value of the tax exclusion is higher for high-income people who pay higher marginal tax rates, health insurance comprises a much higher percentage of income for low-wage workers. This is particularly so given the mundane reality that health benefits are provided in more egalitarian fashion across (full-time) workers than dollar-wages and salaries are. (My own employer, like Professor White’s, actually charges lower premiums to less-compensated employees.) So the tax exclusion is one mechanism to transfer resources, albeit imperfectly towards people with families and others in greater need of health services. If we believe that age discrimination is a significant problem in the American economy, tax subsidies for older workers aren’t the worst thing, either.

One strand of White’s argument becomes obvious with a simple example. Suppose GE provides $10,000 coverage to an executive earning $300,000 annually, and a mid-level worker who earns only $40,000. It’s quite possible that the ESI exclusion is worth $3800 to the executive and only $1500 to her less affluent counterpart. Does this mean that the exclusion is regressive? It’s not so obvious. After all, $1500 is a much larger proportion of $40,000 (3.75%) than $3800 is of $300,000 (1.27%).

For historical reasons, the United States has followed the problematic path of employer-sponsored health coverage for most employed citizens. It’s hard to imagine that we would institute this package of policies—including the ESI exclusion—if we could truly start anew. But we’re not starting anew. As Paul Starr and others rightly noted, providing health coverage through large employers brought genuine advantages along the way: Providing administrative economies and a reasonable internal risk-pool, providing some implicit redistribution to lower-wage workers, too. The challenges facing ACA’s federal and state marketplaces underscore the political and operational difficulties of standing-up viable alternatives to ESI, which would necessarily involve substantial government regulations and subsidies.

I’m not fully sold by White’s argument. Surely there is some way to limit excessive tax expenditures to families like my own. We don’t need the subsidy for these extremely generous plans. And it does bother me that the huge tax subsidy is so hidden, allowing prosperous employed workers to believe that other people—certainly not we ourselves—are beneficiaries of the American social welfare state.

Without a doubt, though, the economic and policy issues are less clear-cut than my standard economics lectures present. Everything in health policy is so darned complicated and path-dependent.

Training your brain so you don’t need reading glasses

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company).

By middle age, the lenses in your eyes harden, becoming less flexible. Your eye muscles increasingly struggle to bend them to focus on this print.

But a new form of training — brain retraining, really — may delay the inevitable age-related loss of close-range visual focus so that you won’t need reading glasses. Various studies say it works, though no treatment of any kind works for everybody.

The increasing difficulty of reading small print that begins in middle age is called presbyopia, from the Greek words for “old man” and “eye.” It’s exceedingly common, and despite the Greek etymology, women experience it, too. Every five years, the average adult over 30 loses the ability to see another line on the eye reading charts used in eye doctors’ offices.

By 45, presbyopia affects an estimated 83 percent of adults in North America. Over age 50, it’s nearly universal. It’s why my middle-aged friends are getting fitted for bifocals or graduated lenses. There are holdouts, of course, who view their cellphones and newspapers at arm’s length to make out the words.

The decline in vision is inconvenient, but it’s also dangerous, causing falls and auto accidents. Bifocals or graduated lenses can help those with presbyopia read, but they also contribute to falls and accidents because they can impair contrast sensitivity (the ability to distinguish between shades of gray) and depth perception.

I’m 45. I don’t need to correct my vision for presbyopia yet, but I can tell it’s coming. I can still read the The New York Times print edition with ease, but to read text in somewhat smaller fonts, I have to strain. Any year now, I figured my eye doctor would tell me it was time to talk about bifocals.

Or so I thought.

Then I undertook a monthslong, strenuous regimen designed to train my brain to correct for what my eye muscles no longer can manage.

The approach has been reported in the news media, and perhaps you’ve heard of it. It’s based on perceptual learning, the improvement of visual performance as a result of demanding training on specific images. Some experts have expressed skepticism that it can work, but a number of studies provide evidence that it can improve visual acuity, contrast sensitivity and reading speed.

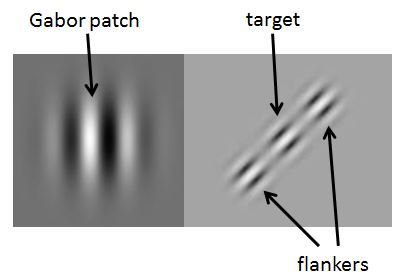

The training involves looking at images called “Gabor patches” in various conditions. Gabor patches optimally stimulate the part of the brain responsible for vision. A great deal of the training involves trying to see Gabor patches placed between closely spaced, distracting flankers. In training, the flanker spacing is varied, the target contrast is turned way down, and the images are flashed on a screen for fractions of a second — to the point that one can barely see the target.

Do this and similar exercises hundreds of times over multiple sessions weekly; continue for months; and, gradually, presbyopia lessens, a number of studies show.

One study also examined functions of the eye itself and found none of these improvements were because of changes in the eye. They’re all in the brain.

Various smartphone apps say they offer this kind of vision-improving training; I used one called GlassesOff, the only one I found that was backed by scientific studies.

Perceptual learning can improve the vision of people who already see quite well and those with other conditions. For example, a study tested the approach in 23 young adults, around age 24. Compared with a control group of 20 young adults, the treatment group increased letter recognition speed. Similar training is an effective component in treating amblyopia, also called “lazy eye,” which is the most frequent cause of vision loss in infants and children, affecting 3 percent of the population. It may also improve vision in those with mild myopia (nearsightedness).

It should be acknowledged that some researchers involved in many of these studies have financial ties to GlassesOff. However, other studies with no commercial links obtained similar results, and several scientists I spoke to, including those without ties to GlassesOff, thought the science behind the app was credible. One study published in Psychological Science trained 16 college-aged adults and 16 older adults (around age 71) with Gabor patch exercises for 1.5 hours per day for seven days. After training, the older adults’ ability to see low-contrast images improved to the level that the college-age ones had before training.

Scientists don’t know exactly how perceptual learning relieves presbyopia, but they have some clues based on how our brain processes visual information.

After first taking in “raw data” of an image through the eye, different sets of neurons in the brain process it as separate features like edges and colors. Then the brain must coordinate activity across sets of neurons to assemble these features into recognizable objects like chairs, faces, letters or words. Reading at our normal pace, the brain has only about 250 milliseconds to do this work until the eyes automatically move onto the next letter or word. Once they do so, we’re taking in more information from whatever the eyes focus on next. If we haven’t yet processed the prior set of information, we can’t understand it.

Visual processing time is challenged and slowed by noisy images, low contrast or closely spaced information (like small fonts). There is a bottleneck in the brain as it attempts to build and then comprehend the image. Therefore, enhancing and speeding up the ability to process image components — through perceptual learning — improves a wide range of vision functions.

What’s surprising is that this is possible in adult brains. Neuroplasticity — the ability of the brain’s processing functions to change to acquire new skills — is most strongly associated with childhood. It’s still more pronounced in children than adults, but for some skills, including vision, the brain is more malleable than once thought.

The training with GlassesOff is long and challenging. I found it fun initially, perhaps because it was new. But weeks into it, I began to dread the monotonous labor. Yet, after a couple of months, the app reports I can read fonts nearly one third the size I could when I started and much more rapidly. According to feedback from GlassesOff, my vision after training is equivalent to a man about 10 years younger than my age. If I reach 50 — the age at which almost everyone needs corrective lenses to read — and still don’t need reading glasses, I may conclude that the training has paid off.

As apps go, GlassesOff is not cheap. I paid $24.99 for three months of use — long enough to get me through the initial program. Upon completion, I was invited to pay another $59.99 per year for maintenance training. It’s a nice option, but the hard work and price probably mean that the bifocals market will remain strong.

March 28, 2017

What happens next to the ACA?

This post was co-authored with Rachel Sachs, a law professor at Washington University School of Law. It has been cross-posted at Take Care, a new blog concerned with President Trump’s constitutional duty to take care to faithfully execute the law.

In his speech after withdrawing the Republican health care bill from consideration on Friday, Speaker of the House Paul Ryan said that “Obamacare is the law of the land” and will remain so “for the foreseeable future.” But law professors who have followed the ACA for the past seven years ago know that its future is not yet secure. President Trump has said that “the best thing we can do politically speaking is let Obamacare explode,” and there’s a lot he can do to make that explosion a reality.

It doesn’t have to come to that. Contrary to GOP reports, the ACA is not collapsing. The Medicaid expansion will continue chugging along and we’re even seeing other states—Kansas and North Carolina most recently—move toward their own expansions. The individual markets in some states are fragile, but they are not in a death spiral. As the Congressional Budget Office noted in its first score of the GOP bill just two weeks ago, the marketplaces would “probably be stable in most areas” under current law.

Without question, however, President Trump and HHS Secretary Price have the ability to radically destabilize the individual marketplace. The only question is whether they attempt to do so through active sabotage, incompetence, or purposeful ambivalence.

One of us (Nick Bagley), together with Adrianna, has already compiled a preliminary list of executive actions President Trump could take that would reshape the ACA. Many of these will not be news, but we write here to focus on two actions with the greatest potential to disrupt the market: ending cost-sharing payments to insurers and declining to enforce the individual mandate.

The largest concern facing the individual markets is the fate of House v. Price, a lawsuit brought by the House of Representatives against President Obama’s HHS Secretary (Sylvia Burwell) in 2014. The House argued that the administration was acting illegally in making cost-sharing payments to insurers because Congress had not specifically appropriated those funds. A judge on the District Court for the District of Columbia ruled both that the House had standing to sue (wrong) and that the administration’s spending violated the Appropriations Clause (right).

The Obama administration appealed the case to the DC Circuit, but, of course, on November 7, 2016, there was an intervening event: the election of President Trump. The GOP-led House then asked the court to stay the litigation to see what the future might hold for health reform. The case is being held in abeyance, with the next status report due at the end of May, just days before insurers must file their insurance plans for 2018.

Here’s why the case is such a big deal for the individual markets: The ACA instructs insurers to limit the out-of-pocket expenses for enrollees who make less than 250% of the federal poverty level. This cost-sharing cap thus plays a key role in keeping insurance affordable for the low-income population. The federal government is then supposed to reimburse insurers for cutting those low-income customers a break.

Without an appropriation, however, the federal government can’t keep making those payments. Insurers would remain bound by the statutory requirement that they reduce cost-sharing for their customers, but they wouldn’t get reimbursed. Without those funds, most insurers will not only refuse to enter the market next year, but may exit the market immediately—cancelling plans and leaving patients uncovered.

What happens next with the lawsuit is anyone’s guess. President Trump could simply drop the appeal, leaving the district court’s ruling in place and crashing the markets. Alternatively, the Republican-controlled Congress could appropriate the money for the cost-sharing payments, which would make House v. Price moot.

Neither of these outcomes seems especially likely, however. It’s more probable, in our view, that the president and the House will mutually agree to put the litigation on life support—holding it in abeyance indefinitely while the cost-sharing payments keep flowing. That’s not an ideal outcome for insurers: House v. Price will hang over their heads like the sword of Damocles, and they’ll be rightly skittish that the Trump administration might eventually dismiss its appeal and cut off their cost-sharing payments. But with the right assurances, insurers could probably be persuaded to stay in the market.

Setting aside House v. Price, the administration will also have to decide how it prioritizes enforcement of the individual mandate. Within days of taking office, not only did President Trump sign an executive order designed to “Minimiz[e] the Economic Burden” of the ACA, but Kellyanne Conway went on television and suggested that the president “may stop enforcing the individual mandate.” That hasn’t happened—yet. But the IRS, in response to Trump’s executive order, has agreed to process tax returns that refuse to answer whether the taxpayer has complied with the individual mandate. Formally and informally, the administration could take other steps to reduce the efficacy of the individual mandate.

And it’s the individual mandate that makes the exchanges possible. Many of the law’s most popular provisions—preventing insurers from denying coverage or charging more on the basis of pre-existing conditions, chiefly—enable sicker people to enter the individual market. To keep premiums stable, however, healthy people have to buy insurance too. Hence the individual mandate. If the administration lets it be known publicly that it’s weakening the mandate, as it has already begun to do, healthier people may flee the market, leading to increased premiums and potential instability.

But House v. Price and the individual mandate are just the beginning. If it chooses, the administration could use dozens of other tools to destabilize the individual insurance markets and undermine the ACA. Even the uncertainty over what the administration might do will inflict damage. The administration may come to believe that it’s in its political interests to make the exchanges work. But if it doesn’t, it has the power to inflict a lot of damage.

March 27, 2017

Healthcare Triage: Premium Support, Medicare, and Obamacare

A number of Republican health care policy proposals that seemed out of favor in the Obama era are now being given new life. One of these involves Medicare, the government health insurance program primarily for older Americans, and is known as premium support.

That’s topic of this week’s Healthcare Triage.

This episode was adapted from a column Austin and I wrote for the Upshot. Links to sources and further reading can be found there.

March 25, 2017

The ACA Won

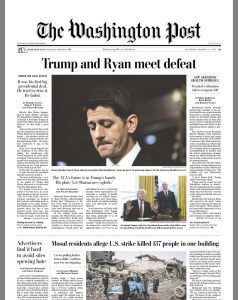

On Friday, the Republicans pulled the American Health Care Act from the House floor. Paul Ryan said that the Affordable Care Act would remain law “for the foreseeable future.” Headlines have described this as either Ryan’s defeat or Trump’s. Or both. That suggests that more skilled Republican leaders wouldn’t have lost.

On Friday, the Republicans pulled the American Health Care Act from the House floor. Paul Ryan said that the Affordable Care Act would remain law “for the foreseeable future.” Headlines have described this as either Ryan’s defeat or Trump’s. Or both. That suggests that more skilled Republican leaders wouldn’t have lost.

But it’s just as valid to see it this way: America had a choice between the ACA and a Republican alternative. They chose the former. David Frum argues that this is because American moral values have changed:

In that third week in March in 2010 [when the ACA was passed], America committed itself for the first time to the principle of universal (or near universal) health-care coverage. That principle has had seven years to work its way into American life and into the public sense of right and wrong. It’s not yet unanimously accepted. But it’s accepted by enough voters—and especially by enough Republican voters—to render impossible the seven-year Republican vision of removing that coverage from those who have gained it under the Affordable Care Act. Paul Ryan still upholds the right of Americans to “choose” to go uninsured if they cannot afford to pay the cost of their insurance on their own. His country no longer agrees.

This change is visible in Pew Research polling data,

Currently, 60% of Americans say the government should be responsible for ensuring health care coverage for all Americans, compared with 38% who say this should not be the government’s responsibility. The share saying it is the government’s responsibility has increased from 51% last year and now stands at its highest point in nearly a decade.

Journalists write stories, and stories need protagonists, and celebrities are all-purpose protagonists, and there is nothing more delicious than watching a celebrity get publicly shamed. Therefore, the commentary on the defeat of the AHCA will focus on the humiliation of America’s Celebrity, Donald J. Trump, the supposed superstar dealmaker.

That trivializes what happened. The Congress was voting on a bill, not Donald Trump. The American people were offered a Republican and conservative approach to health insurance, and only 17% of them approved of it. The defects and merits of the ACA had been debated in four successive elections and litigated in two Supreme Court cases. The Republicans held the Presidency and both houses of Congress. Yet the ACA won.

March 24, 2017

Healthcare Triage: Regional Difference in Procedures and Prices

I’ve been travelling, so I’m late to post this. Sorry!

You might think that once drugs, devices and medical procedures are shown to be effective, they quickly become available. You might also think that those shown not to work as well as alternatives are immediately discarded.

Reasonable assumptions both, but you’d be wrong. That’s the topic of this week’s Healthcare Triage.

This episode was adapted from a column Austin and Jon Skinner wrote for the Upshot. Links to sources and further reading can be found there.

AcademyHealth: We have to make policy line up with the changes we’d like to see

If we want to see research implemented well in the real world with effects we can see, we need to focus on making policy consistent with the studies we do, focusing on the populations where the benefits will likely be seen.

The DASH diet is 20 years old. How has it worked? Go read more about this in my latest post over at the AcademyHealth blog!

Confusion over essential health benefits

Last night, House Republicans released the text of the final manager’s amendment to the American Health Care Act, including changes to the rules governing the essential health benefits. With these tweaks, the House hopes to pass the bill today.

House Republicans should look before they leap. Even if they’re on board with the amendment’s goals, its actual language is a train-wreck. If it becomes law, the individual insurance market will likely collapse nationwide in 2018. Its fate after that will be highly uncertain.

* * *

Eliminating the requirement that insurers in the individual and small-group market cover the essential health benefits would have created a vicious race to the bottom among insurers. Fortunately, the manager’s amendment doesn’t go that far. Instead, the amendment tells each state to define what counts as essential within the state. State-defined benefits will then set a floor on what insurers can offer, arresting the race to the bottom.

Whether you like the idea of punting to the states may turn on how you feel about federalism. I happen to think there’s a lot to be said for it, but your mileage may vary. (For present purposes, I’m setting aside the thorny question of whether the Senate can adopt a change to the essential health benefits rule through reconciliation.)

However you feel about the policy, though, the manager’s amendment is troubling. Start with its irresponsibility. The new rule would apply as of January 1, 2018. But insurers have to create and price their health plans within the next few months in order to get them approved prior to the start of open enrollment. They don’t know which services their states will say are essential and they don’t have time to wait around while their states bicker about it. Insurers are likely to walk. All of them. The individual market in 2018 will be a ghost town.

* * *

The problem actually runs deeper. Under the manager’s amendment, states must define the essential health benefits “for the purposes of section 36B of the Internal Revenue Code.” Section 36B in turn governs eligibility for the AHCA’s meager tax credits; among other things, you’re eligible only if you buy a qualified health plan that covers the essential health benefits. In 2018 and beyond, then, it looks like you’re eligible for tax credits only if you buy a health plan that adheres to state-defined essential health benefits.

So—in a weird echo of the argument in King v. Burwell—if a state hasn’t defined the essential health benefits, it seems that no one in the state is eligible for tax credits. If that’s right, then the best way to read the manager’s amendment may be the same way that Republicans in King argued the ACA should be read: as dangling tax credits to induce states to do what Congress couldn’t order them to do directly.

I can’t imagine that’s what House Republicans have in mind, just as it wasn’t what the ACA’s drafters had in mind. But that appears to be what this amendment says. Perhaps HHS could adopt an alternative interpretation through rulemaking, but that too will take time—several months, probably closer to a year—and any rule would be challenged in court. Until the uncertainty is resolved, no insurer will offer health plans in any state that—for whatever reason—can’t get its act together to specify the essential health benefits.

* * *

Which brings me to the final ambiguity. The manager’s amendment retains almost the entirety of the ACA’s rule governing the essential health benefits. The Secretary of HHS is still required to “define the essential health benefits,” which must include the ten major benefit categories, including maternity care and mental health services. Plus, the Secretary must “ensure” that the scope of the essential health benefits is “equal to the scope of benefits provided under a typical employer plan.”

The amendment just tacks on a provision saying that, for 2018 and beyond, “each State shall define the essential health benefits with respect to health plans offered in such State.” That’s all the provision says; it doesn’t elaborate. So do these state-defined essential health benefits also have to cover the ten categories of benefits? And do those benefits have to be the same as those in a “typical employer plan”?

The amendment doesn’t say. It’s probably best understood to give states carte blanche to define essential health benefits. The ten categories and the typicality requirement would then apply only to the HHS Secretary’s definition, not to the states’ definitions.

But that’s not the only way to read the amendment. It’s also possible to read it as shifting responsibility for defining the essential health benefits from the Secretary to the states. On that view, states would have to adhere to the same rules that govern the Secretary’s definition. Maternity care and mental health services, among other benefits, would still have to be covered. Typicality would be preserved.

Now, Secretary Price could probably issue a rule resolving this ambiguity in favor of state authority. But that, again, will take time—maybe years, if you take into account the inevitable litigation. In the meantime, the uncertainty will drive insurers from the individual insurance markets.

* * *

The deficiencies of the manager’s amendment exemplify the perils of refashioning an enormous and complex system on the fly. Health care is complicated; anyone who tells you otherwise is delusional. If Republicans want to change the rules governing the essential health benefits, they need to take care that they don’t accidentally destroy the individual insurance market. The manager’s amendment fails to clear that very low bar.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers