Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 141

March 22, 2017

I’ll be speaking at Amherst College on Thursday!

Any longtime reader of the blog knows how much I love Amherst College, having graduated from there in 1994. For the second time in recent years, I’ll be getting to head back there in a more professorial role. I’ll be meeting with a lot of pre-med students, talking in a health economics class, and giving a talk on Thursday evening.

That’s what this post is about. I’ll be giving a talk on “Evidence Based Health Policy: An Unfortunately Elusive Goal” at the Loeb Center, College Hall, Events Room from 7:30 to 8:30 PM on Thursday, March 23. If you’re anywhere nearby, you should come!

Why Cystic Fibrosis Patients in Canada Outlive Those in the U.S.

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company).

Cystic fibrosis is an inherited disorder that affects the lungs, pancreas, intestines and other organs. A genetic mutation leads to secretory glands that don’t work well; lungs can get clogged with thick mucus; the pancreas can become plugged up; and the gut can fail to absorb enough nutrients.

It has no cure. Over the last few decades, though, we have developed medications, diets and treatments for depredations of the disease. Care has improved so much that people with cystic fibrosis are living on average into their 40s in the United States.

In Canada, however, they are living into their 50s.

A recent study published in Annals of Internal Medicine used the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Registry and the United States Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry to determine how patients fared between 1990 and 2013. Researchers compared the longevity results in the two countries, and controlled for a number of factors, including age, sex, genotype, pancreatic status and more.

Over time, they found, the median life span for patients increased. But it increased faster in Canada. Between 2009 and 2013, the median life span was 40.6 years in the United States versus 50.9 in Canada.

One reason might have been that more Canadians with cystic fibrosis received lung transplants (10.3 percent) than their American counterparts (6.5 percent). In Canada, organs are allocated based on length of time on the waiting list. Because people with cystic fibrosis know they may need new lungs long before they become critically ill, they can sign up earlier and be on the list longer before they truly need a transplant. In the United States, organs are allocated based on disease severity; people with cystic fibrosis need to become very ill before they can get a lung, and fewer of them do.

Relatively few cystic fibrosis patients receive lung transplants, however, so it’s unlikely this is the real difference accounting for a decade of life.

Another difference might be nutrition. Older studies comparing cystic fibrosis survival between the two nations showed that aggressive nutritional support with a high-fat, high-calorie diet in the 1970s might have improved prospects for patients in Canada back then. Physicians in the United States instituted more appropriate diets for patients after studies in the 1970s and 1980s showed them to be superior, making inadequate nutrition a less likely culprit as well.

Further analysis revealed a much more significant association: insurance.

Canada has a single-payer health care system, which is similar to the American Medicare system. It covers all people in Canada, including those with cystic fibrosis. People in the United States receive their insurance — if they do at all — from a number of sources.

Compared with patients in the United States who had private insurance coverage, patients in Canada had a similar risk of early death. Compared with patients who had public insurance like Medicaid, Canadians with cystic fibrosis had a 44 percent lower risk of early death. And compared with Americans who were uninsured, Canadians had a 77 percent lower risk of early death.

A number of factors could be at play. Medications for cystic fibrosis can be expensive, and patients have to take many every day. About 45 percent of American patients with cystic fibrosis receive some form of Medicaid, which can limit the medications patients can get, the providers they can see and the therapies that are covered. For the uninsured, it can be even worse. Insurance, as well as the cost of care, remains a significant concern for people with cystic fibrosis.

No study is perfect, and it’s possible that insurance coverage might just be a marker for socioeconomic status in this analysis. Study after study has shown us that poverty is associated with worse outcomes for many diseases, cystic fibrosis included. Yet the poorest in the United States are more likely to have Medicaid than to be uninsured, and in this study they had better outcomes than those with no insurance at all.

Another fact hints at the power of Canada’s broad health insurance: Canadians tend to live an average of two years longer than Americans. While insurance, and access to the health care system, is certainly not the only factor that affects life expectancy, it’s hard to argue that it’s not at least one factor.

What’s even more compelling is that children and young adults with cystic fibrosis in the United States fare better than their international counterparts on certain health measures. It’s as people age — and, perhaps, as disparities mount — that Americans begin to fall behind.

The United States didn’t always lag in this respect. From 1974 through 1994, cystic fibrosis patients who lived in the United States consistently outlived patients living in other countries in North America, Europe and Australia. Americans have lost that advantage.

It’s easy to repeat the mantra that the United States has “the best health care system in the world.” But a system must be judged on its overall outcomes, and when that is done, America often comes up short.

March 20, 2017

The Cost Can Be Debated, but Meals on Wheels Gets Results

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company).

Meals on Wheels has been delivering food to older people in the United States since the 1950s. Last year it served 2.4 million people. This week, after President Trump released his budget proposal, a furor erupted over the program’s future and effectiveness. Let’s look at the evidence.

Mr. Trump’s budget proposes big cuts to discretionary spending. In a news conference on Thursday, his budget director, Mick Mulvaney, defended cuts to the Community Development Block Grant program by arguing that it was “just not showing any results.” (Some states give a portion of that block grant money to Meals on Wheels.)

“We can’t spend money on programs just because they sound good,” Mr. Mulvaney said. “And Meals on Wheels sounds great — again, that’s a state decision to fund that particular portion to. But to take the federal money and give it to the states and say, ‘Look, we want to give you money for programs that don’t work’ — I can’t defend that anymore.”

Despite expressions of alarm on social media, killing the community block grant program would most likely not kill Meals on Wheels. The financial statements from 2015 show that such grants amounted to just under $250,000, or about 3 percent of the total revenue for the program’s national resource center. More than 85 percent came from corporate, foundation and personal donations. Clearly, federal funding for the national program office isn’t the linchpin for its success.

Public funds at the local level, however, are more substantial, and Meals on Wheels gets much more funding through a different federal program. The nutrition programs of the Older Americans Act support the Meals on Wheels chapters as they actually operate on the ground, and about 30 percent of the expense of home-delivered meals is covered by federal sources.

A cut to this program would have a far more significant effect, especially since that support had been decreasing even before the new budget was considered. The Trump budget calls for a 17.9 percent cut in funding for this program’s parent agency, the Department of Health and Human Services, and it is quite possible Meals on Wheels could be affected. We won’t know until H.H.S. finalizes its budget.

Now, what about the assumption, explicit or implicit, that the program has not achieved “results”?

Meals on Wheels has been the subject of many peer-reviewed studies in the medical literature. So many have been done that there are several systematic reviews gathering these studies into various domains.

In 2014, researchers explored the evidence on whether home-delivered meal programs improved the diet and nutrition of older Americans. They found eight studies, two of which were randomized controlled trials. Six of the eight showed that programs like Meals on Wheels improve the quality of people’s diet, increase their nutrient intake, and reduce their food insecurity and nutritional risk. They also noted that the programs increased chances for human contact and improved quality of life.

A 2015 review found that 80 studies have been conducted on programs like Meals on Wheels. The authors noted, however, that few of these were randomized controlled trials, and that even fewer focused on the program as a whole. They were correct, and I am sympathetic to these calls for more rigorous trials. But such trials are hard to do, they’re expensive, and funding for them seems to be going down, not up.

Saying that you want better evidence is different from saying that there is no evidence, though.

It’s important to recognize that the program’s benefits are not merely nutritional. A 2016 study showed that participants in the Meals on Wheels program had lower loneliness scores. A 2013 study showed that spending on services like Meals on Wheels was associated with less reliance on institutionalized care, because more people could live independently at home. They may even have fewer falls at home and less worry about being able to remain there.

Finally, although no one measures it, Meals on Wheels brings people food they otherwise wouldn’t have.

Researchers conducted economic analyses in 2013 and showed that if all states had increased the number of older Americans who had received Meals on Wheels by just 1 percent, the states would have saved Medicaid more than $109 million. Most of those savings would have come from reductions in the need for nursing home care.

We can debate the cost-effectiveness of Meals on Wheels, but it would be wrong to say that it’s not effective. There are plenty of results, and I’ve highlighted only some of the most rigorous research available. Most programs we fund through tax dollars have far less evidence to support them, if any evidence at all.

About the worst thing you might say about Meals on Wheels is that putting money into a different program might be of more help to older Americans. There’s no evidence that Meals on Wheels is the most cost-effective program there is, or that it’s the most efficient use of our taxpayer dollars.

Any argument that goes in that direction, though, raises the question of whether there is a program that does a better job, and whether there is evidence to support it.

March 17, 2017

AcademyHealth: Explaining the growth in Medicare Advantage

Medicare Advantage’s cost to Medicare is different than traditional Medicare’s. So, predicting MA enrollment is important for projecting future Medicare costs to taxpayers. We’ve entered an era in which such prediction has become difficult and more speculative. In my latest AcademyHealth post I get some help from colleagues in trying to explain MA’s enrollment growth.

Healthcare Triage: Results Are In! Congressional Budget Office Scores the American Health Care Act

Want to know what’s in the CBO report? Don’t want to read it? We’ve got you covered. Another very special episode of Healthcare Triage:

Text of the report here.

Out of Sight, Out of Mind — Behavioral and Developmental Care for Rural Children

Today in the NEJM, Kelly Kelleher (of Nationwide Children’s Hospital) and I discuss rural US kids with mental health and developmental disorders, and the obstacles to caring for them.

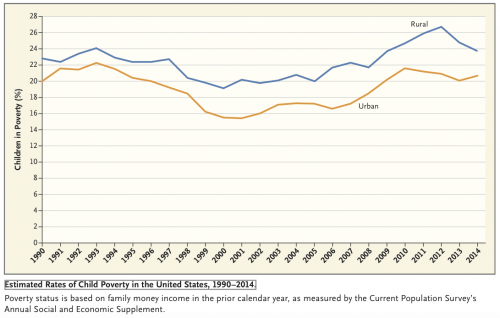

We summarize new data from the Centers for Disease Control about the epidemiology of these problems among rural kids. We also discuss data from the US Department of Agriculture which show that poverty is higher among rural children than urban children and that rural child poverty is higher than it has been since 1993.

Poverty is more common for rural children.

Then we look at the many obstacles to getting services to kids in rural settings, particularly the lack of mental health specialists. It’s a problem in the US and Canada, both of which have large regions with low population densities.

We conclude:

A romantic and pastoral view of the countryside as a place of healing is ingrained in American culture. The increased burden of MBDDs among rural children belies this image, as does the failure of the traditional behavioral and developmental health care system to address rural children’s needs. These problems have received too little attention, because most behavioral and developmental health specialists, researchers, and health policymakers live in cities. The problems of rural children, their families’ crises, and the lack of services have been out of sight and out of mind.

And of course I have to say: please read the whole thing!

Our article was in press before the text of the AHCA was released. Sara Rosenbaum reports that the bill changes Medicaid in several ways.

the House bill essentially eliminates the enhanced funding levels that made possible states’ expansion of Medicaid to their poorest working-age adult residents, something that 31 states and the District of Columbia now have done. Expansion states could face up to a 40-point difference between the federal funding enhancements they expected to receive in 2020 for the expansion population and what they actually would receive under the bill. What is at stake is continued coverage for some 11 million of the more than 16 million people who have gained eligibility since full implementation of the ACA Medicaid expansion.

The proposed changes could harm rural America, and rural American kids specifically, in two ways.

First, many rural families are covered by Medicaid. Losing this coverage will increase the stress on already highly-stressed families. Medicaid funding is also critical to the children’s hospitals that are among the primary places that kids get care for developmental and mental health disorders.

Second, rural Americans are currently experiencing a significant public health crisis involving opiates, amphetamines, and suicide. Parental substance abuse can adversely affect children. The AHCA has a provision that may undermine efforts to address the substance abuse epidemic. Katie Zezima and Chris Ingraham report in the Washington Post that

Beginning in 2020, the plan would eliminate an Affordable Care Act requirement that Medicaid cover basic mental-health and addiction services in states that expanded it, allowing them to decide whether to include those benefits in Medicaid plans.

There are large areas in rural Americas where there are no addiction services. If Medicaid funding shrinks, state administrators will look for places to cut. Eliminating the requirement to fund mental health and addiction services means that funding shortfalls will disproportionately affect kids with mental health and developmental disorders.

March 16, 2017

Performance art: Trump proposes a 20% cut to the NIH

From Science, Donald Trump’s first budget for research:

President Donald Trump’s first budget request to Congress, to be released at 7 a.m. Thursday, will call for cutting the 2018 budget of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) by $6 billion, or nearly 20%, according to sources familiar with the proposal. The Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Office of Science would lose $900 million, or nearly 20% of its $5 billion budget. The proposal also calls for deep cuts to the research programs at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and a 5% cut to NASA’s Earth science budget. And it would eliminate DOE’s roughly $300 million Advanced Research Projects Agency – Energy (ARPA-E).

This is absurd. The US Congress hasn’t passed a budget since 2009, but if by some miracle it does in 2017, it will not include a 20% decrease in the NIH budget. Does the President understand that the Congress will not do this? Does he even know that his budget says this?

Rotten, J., et al. (1979)

Well, someone in his office wrote these numbers down. What point was that person trying to make? Consider the budget not as a plan for governing but as an artistic performance, a kind of Sex Pistols track from the alt-right, a scream of anger against the dull conformity of funding research into health and well-being.

What values are being expressed?

Cardiovascular diseases doesn’t matter? (CDC: 610,000 people die of heart disease in the United States every year.)

Cancer doesn’t matter? (CDC: 595,000 people die of cancer in the United States every year.)

Substance abuse doesn’t matter? (CDC: 50,000 opioid-involved deaths in the United States every year.)

Nothing matters?

What does the administration value? The US government spends $3 million on each weekend Trump spends in Palm Beach. That will come to $130 million per year at the current pace. An average NIH R01 grant costs $500K. The President’s weekly resort trips cost us 260 medical research projects, per year.

March 15, 2017

Avoiding the health care run-around

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company).

You’ve all experienced it: There’s a problem with your health care bill, or you have difficulty getting coverage for the care you need. Your doctor or hospital tells you to talk to your insurer. Your insurer tells you to talk to your doctor or hospital. You’re stuck in an endless runaround.

A small patient advocacy industry has sprung up to help, but that help can cost several hundred dollars an hour. Is there a way to get the customer service we deserve?

Turns out, some kinds of health insurance plans provide better customer service than others. Among those that do are plans offered directly by hospitals or health systems, according to results from a recent study by me; Garret Johnson, now a medical student at Harvard; and Zoë Lyon, a research assistant at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Our conclusions are based on analysis of Medicare Advantage plans — private insurance alternatives to traditional Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans are offered by major insurers like UnitedHealthcare, Humana, Aetna, BlueCross BlueShield affiliates and others. But nearly one-quarter of the plans are issued by hospitals or health systems. These provider-offered plans are more likely found in dense, urban areas in the Northeast and the West.

The government collects data on health care quality from surveys and medical claims, then aggregates them into ratings of plans. These are publicly reported in units of stars: Five stars represents the highest quality, and one the lowest. Our study, published this month in the health policy journal Health Affairs, found that provider-offered plans have higher quality ratings.

Plans offered by insurers have average ratings of just over 3.5 stars for both nondrug and drug service. An average provider-offered plan has quality ratings that are about one-third of a star higher for both, after adjusting for factors that could confound the comparison, like socioeconomic status and the types and number of doctors where plans are offered.

Our study dug deeper to examine the kinds of quality enhancements available in provider-offered plans. Some aspects of quality are clinically focused. For instance, measures of preventive screening — like that for colorectal cancer — or management of chronic conditions assess the quality of care delivered by doctors and hospitals in a plan’s networks. Provider-offered plans perform somewhat better than insurer-offered plans in such areas.

Other aspects of quality pertain to customer service. In measures of complaints, responsiveness to customers and the enrollees’ overall experiences, provider-offered plans really shine. In each area of customer service we examined, provider-offered plans are rated one-half star higher than insurer-offered ones. (This is a big difference. For comparison, over half of plans are within one star of each other in overall quality.)

These results make some sense. When a customer has an issue — like a problem with a hospital bill — the easiest thing for a health plan to do is pass it off to the hospital. Likewise, the hospital’s easiest course of action is to blame the health plan. The patient, stuck in the middle, is not likely to rate his plan (or hospital) highly for customer service in this case.

However, when the plan and hospital are one and the same, neither can pass the buck to the other. Problems may be resolved faster; they may be less likely to develop in the first place. This could lead to the higher customer satisfaction reflected in the quality ratings.

If the higher ratings are enough to interest you in trying a provider-offered plan, how would you find one? Unfortunately, there’s no readily accessible source to inform consumers (or researchers) about this feature of plans. Sometimes the plan’s name gives away the relationship. The UPMC Health Plan practically has the health system that offers it right in the name — UPMC stands for University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. In other cases, consumers can identify the relationship on plans’ or health systems’ websites. For example, the Vital Traditions plan website identifies as its parent company the largest nonprofit hospital system in Texas, Baylor Scott & White.

But in many cases, it’s not so easy to figure out. In fact, this is why there has been so little analysis of provider versus insurer plans. For our study, we had to scroll through hundreds of websites, news articles and documents to build a research data set on provider-offered plans from 2011 to 2015. Because of the work involved, there are very few studies on the subject. Another, published in Health Service Research by me, Roger Feldman of the University of Minnesota and Steven Pizer of Northeastern University, found a similar quality relationship when examining 2009 data.

That earlier study also found that provider-offered Medicare Advantage plans charge higher premiums. But a recent study of marketplace plans found that provider-offered ones are not necessarily the most expensive. For some, a higher premium may outweigh the benefits of greater quality, but for others it may not.

From our study, we can’t be certain that provider sponsorship of plans causes higher quality. It could be that higher-quality providers are the ones that choose to offer plans. Nevertheless, such tight integration between plans and providers is at least a signal of higher quality, even if it doesn’t cause it.

Recent trends suggest more health systems are offering plans in other health care markets for the working-age population, not just in Medicare Advantage. Not all markets may be hospitable to provider-offered plans, however. Some systems that did offer plans are pulling back. According to The Wall Street Journal, Catholic Health Initiatives, which runs over 100 hospitals across 18 states, is divesting itself of some of its health insurance plans. After struggles with profitability, Tenet Healthcare and several other health systems have said they will do the same.

Provider-offered plans may increase convenience for consumers. But the financial risk it confers on the organizations that offer them may be more than some can handle.

March 14, 2017

Healthcare Triage: One Republican Backup Plan for the AHCA: Cassidy-Collins

If the new AHCA doesn’t pass (which is definitely in the realm of possibility), Republicans in Congress will need to come up with another plan to fulfill their promise to repeal and replace Obamacare. Senators Susan Collins of Maine, and Bill Cassidy of Louisiana have a plan, we’re going to tell you about it. That’s the topic of this week’s Healthcare Triage.

We taped this before the AHCA was released. I don’t care. I think Cassidy-Collins may re-emerge and become more important if the AHCA falls apart.

Read the summary here.

The CBO report on the AHCA in as few words as I can manage

Just like last week, I’m trying to describe the report in a few words as I can manage, to make a Healthcare Triage script. The below is my attempt. I’m going to leave comments open, and I encourage you to tell me where I’m wrong or missed something. I don’t tape until tomorrow. You can also tweet me suggested changes. Text of the report here.

The Congressional Budget Office is charged with producing independent analyses of budgetary and economic issues to support the Congressional budget process. It’s a nonpartisan office, and its current director was appointed by the Republicans in Congress. Keith Hall is not generally considered a fan of the ACA, and you can go read some glowing quotes about him by then-Congressman and now-HHS Secretary Tom Price here.

Let’s be frank: the CBO report doesn’t look good for the AHCA. Let’s divide its findings into a number of domains in order to understand it more fully.

Insurance Coverage

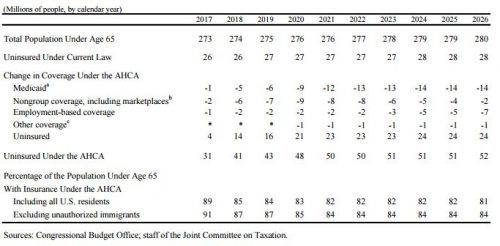

In 2018, just next year, the AHCA would result in 14 million more people being uninsured than under current law. Most of that would come from repealing the mandate. Some would choose not to buy insurance cause they don’t have to (healthy people) and some because they couldn’t afford it.

By 2020, the number of additional uninsured due to the AHCA would be 21 million. By 2026, it would be 24 million. Most of the newly uninsured at that point would be due to changes in Medicaid (which I’ll get to in a bit).

The CBO agrees with me that the continuous coverage provisions might not work as planned. They think they will increase the number of people with insurance in 2018, but reduce the number in 2019 and beyond. In that first year, about a million people will buy insurance to enter the program, but each year after that, about 2 million will not because they will be forced to pay a penalty when they do. Those will be healthier people, by the way.

Fourteen million fewer getting insurance in the Medicaid program, 2 million fewer in the marketplaces, seven million fewer in employer-based coverage, and one million fewer from other sources. Under current law, it’s estimated that 28 million people might be uninsured in 2026. Under the AHCA, it would be 52 million people.

Medicaid

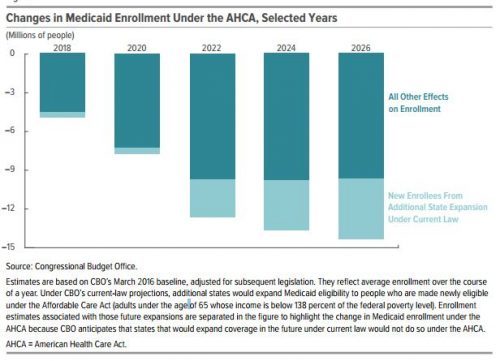

Medicaid takes it on the chin. The CBO thinks that over the next decade, spending on the program would be reduced by about $880 billion. As we discussed last week, the per capita block grants go up each year by medical CPI+1%. The CBO agrees with me that this is likely to rise more slowly than actual medical spending in Medicaid.

It estimates that CPI-M will go up 3.7% each year on agerage over the decade. Medicaid spending will go up 4.4% a year, though. That leaves a lot of money for the states to make up. Either they do that, or they start to cut.

Enrollment is expected to drop pretty impressively, by about 14 million in 2026. Before 2020, almost all those dropped from Medicaid are not expansion-eligible individuals, although the percentage from that population increases starting then through 2020.

Health Insurance Market Stability

If you listen to some politicians, they claim Obamacare is in a death spiral. Others, like me, think that’s massively overstating the case. But let’s listen to the CBO: “Under the AHCA, the subsidies available, added to the grants in the Patient and State Stability Fund, would stabilize the market.”

But the CBO also says the market is stable under current law. In essence, the AHCA doesn’t change much in that respect.

Premiums for Health Insurance

In 2018 and 2019, premiums would actually go up about 15-20% because with the elimination of the mandate, healthy people will leave the market and leave the risk pool sicker, and more expensive.

But, in 2020, the Patient and State Stability Fund could be used to offset the costs of the very sick. Insurers could also start to offer plans of lower actuarial value – which would allow for premiums to be lower. Of course, that means higher OOP payments, but I’ll get to that in a second. They also think healthier, younger people might return, lowering the price per beneficiary.

These changes will combine to let premiums be about 10% lower in 2026 than under current law.

Of course, there are averages. Older people are gonna get crushed and younger people will do better. More on that in a minute.

Details on Premiums and Subsidies on the Exchanges

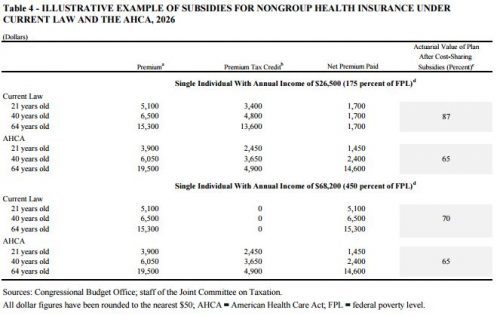

Let’s take a closer look here. In 2026, under current law, if we look at someone who makes $26,500 a year, they all pay about $1700 in premiums for insurance regardless of income. That’s cause while insurance costs $5100 for a 21yo, $6500 for a 40yo, and $15,300 for a 64yo, the subsidies are big.

Under the AHCA, the cost of insurance itself is lower for the 21yo, slightly lower for the 40yo, but much higher for the 64yo. But the subsidies go way down, cause they don’t adjust for wealth. So the 21yo will pay $1450 (which is slightly less), but the 40yo pays $2400 (more), and the 64yo pays $14,600 (which is more than half their income). And this new insurance has an actuarial value about 20% lower, meaning that they have much higher OOP payments.

If they make $68,200, then under current law they get no subsidies, so their payments are the cost of insurance: $5100 for a 21yo, $6500 for a 40yo, and $15,300 for a 64yo. With the AHCA, though, they all do better, cause they get something in subsidies when they got nothing under the ACA. They pay the exact same as the poorer person: the 21yo pays $1450, the 40yo pays $2400, and the 64yo pays $14,600.

So the more well-off see some premium savings (but slightly higher OOP payments), but the poor get, well, hammered. Especially the older, poorer people.

Effects on the Federal Budget

There are massive reductions in spending under the AHCA. Outlays for Medicaid go down $880 billion. The elimination of the ACA’s subsidies in 2020 saves another $673 billion. Decreases in the employer-based health insurance market save another $70 billion. And repealing a tax credit to small employers for providing insurance saves $6 billion.

But! The new tax credits cost $361 billion. Getting rid of mandates and penalties costs another $210 billion. The Patient and State Stability Funds cost $80 billion. And reinstating DSH payments costs $43 billion.

And let’s not forget the tax cuts. About $600 billion in tax cuts, most to people at the very high end of the socioeconomic spectrum.

Bottom line: Spending goes down about $1.22 trillion dollars, and revenue goes down about $883 billion. Therefore, the CBO projects that the federal deficit would be reduced by $337 billion over a decade.

And since I get this question a lot, eliminating Planned Parenthood coverage saves (overall) $156 million over a decade. The technical reduced outlays are more, but that’s reduced by increases in Medicaid spending, thousands more births, and associated care. And because this is the real world and there are tradeoffs, lots of women will lose access to care in “areas without other health care clinics or medical practitioners who serve low-income populations.”

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers