Scott Aaronson's Blog, page 13

March 9, 2023

The False Promise of Chomskyism

I was asked to respond to the New York Times opinion piece entitled The False Promise of ChatGPT, by Noam Chomsky along with Ian Roberts and Jeffrey Watumull (who once took my class at MIT). I’ll be busy all day at the Harvard CS department, where I’m giving a quantum talk this afternoon. [Added: Several commenters complained that they found this sentence “condescending,” but I’m not sure what exactly they wanted me to say—that I was visiting some school in Cambridge, MA, two T stops from the school where Chomsky works and I used to work?]

But for now:

In this piece Chomsky, the intellectual godfather god of an effort that failed for 60 years to build machines that can converse in ordinary language, condemns the effort that succeeded. [Added: Please, please stop writing that I must be an ignoramus since I don’t even know that Chomsky has never worked on AI. I know perfectly well that he hasn’t, and meant only that he’s regarded as the highest authority by the anti-statistical, “don’t-look-through-the-telescope” AI faction, the ones views he himself fully endorses in his attack-piece. If you don’t know the relevant history, read Norvig.]

Chomsky condemns ChatGPT for four reasons:

because it could, in principle, misinterpret sentences that could also be sentence fragments, like “John is too stubborn to talk to” (bizarrely, he never checks whether it does misinterpret it—I just tried it this morning and it seems to decide correctly based on context whether it’s a sentence or a sentence fragment, much like I would!);because it doesn’t learn the way humans do (personally, I think ChatGPT and other large language models have massively illuminated at least one component of the human language faculty, what you could call its predictive coding component, though clearly not all of it);because it could learn false facts or grammatical systems if fed false training data (how could it be otherwise?); andmost of all because it’s “amoral,” refusing to take a stand on potentially controversial issues (he gives an example involving the ethics of terraforming Mars).This last, of course, is a choice, imposed by OpenAI using reinforcement learning. The reason for it is simply that ChatGPT is a consumer product. The same people who condemn it for not taking controversial stands would condemn it much more loudly if it did — just like the same people who condemn it for wrong answers and explanations, would condemn it equally for right ones (Chomsky promises as much in the essay).

I submit that, like the Jesuit astronomers declining to look through Galileo’s telescope, what Chomsky and his followers are ultimately angry at is reality itself, for having the temerity to offer something up that they didn’t predict and that doesn’t fit their worldview.

[Note for people who might be visiting this blog for the first time: I’m a CS professor at UT Austin, on leave for one year to work at OpenAI on the theoretical foundations of AI safety. I accepted OpenAI’s offer in part because I already held the views here, or something close to them; and given that I could see how large language models were poised to change the world for good and ill, I wanted to be part of the effort to help prevent their misuse. No one at OpenAI asked me to write this or saw it beforehand, and I don’t even know to what extent they agree with it.]

March 6, 2023

Why am I not terrified of AI?

Every week now, it seems, events on the ground make a fresh mockery of those who confidently assert what AI will never be able to do, or won’t do for centuries if ever, or is incoherent even to ask for, or wouldn’t matter even if an AI did appear to do it, or would require a breakthrough in “symbol-grounding,” “semantics,” “compositionality” or some other abstraction that puts the end of human intellectual dominance on earth conveniently far beyond where we’d actually have to worry about it. Many of my brilliant academic colleagues still haven’t adjusted to the new reality: maybe they’re just so conditioned by the broken promises of previous decades that they’d laugh at the Silicon Valley nerds with their febrile Skynet fantasies even as a T-1000 reconstituted itself from metal droplets in front of them.

No doubt these colleagues feel the same deep frustration that I feel, as I explain for the billionth time why this week’s headline about noisy quantum computers solving traffic flow and machine learning and financial optimization problems doesn’t mean what the hypesters claim it means. But whereas I’d say events have largely proved me right about quantum computing—where are all those practical speedups on NISQ devices, anyway?—events have already proven many naysayers wrong about AI. Or to say it more carefully: yes, quantum computers really are able to do more and more of what we use classical computers for, and AI really is able to do more and more of what we use human brains for. There’s spectacular engineering progress on both fronts. The crucial difference is that quantum computers won’t be useful until they can beat the best classical computers on one or more practical problems, whereas an AI that merely writes or draws like a middling human already changes the world.

Given the new reality, and my full acknowledgment of the new reality, and my refusal to go down with the sinking ship of “AI will probably never do X and please stop being so impressed that it just did X”—many have wondered, why aren’t I much more terrified? Why am I still not fully on board with the Orthodox AI doom scenario, the Eliezer Yudkowsky one, the one where an unaligned AI will sooner or later (probably sooner) unleash self-replicating nanobots that turn us all to goo?

Is the answer simply that I’m too much of an academic conformist, afraid to endorse anything that sounds weird or far-out or culty? I certainly should consider the possibility. If so, though, how do you explain the fact that I’ve publicly said things, right on this blog, several orders of magnitude likelier to get me in trouble than “I’m scared about AI destroying the world”—an idea now so firmly within the Overton Window that Henry Kissinger gravely ponders it in the Wall Street Journal?

On a trip to the Bay Area last week, my rationalist friends asked me some version of the “why aren’t you more terrified?” question over and over. Often it was paired with: “Scott, as someone working at OpenAI this year, how can you defend that company’s existence at all? Did OpenAI not just endanger the whole world, by successfully teaming up with Microsoft to bait Google into an AI capabilities race—precisely what we were all trying to avoid? Won’t this race burn the little time we had thought we had left to solve the AI alignment problem?”

In response, I often stressed that my role at OpenAI has specifically been to think about ways to make GPT and OpenAI’s other products safer, including via watermarking, cryptographic backdoors, and more. Would the rationalists rather I not do this? Is there something else I should work on instead? Do they have suggestions?

“Oh, no!” the rationalists would reply. “We love that you’re at OpenAI thinking about these problems! Please continue exactly what you’re doing! It’s just … why don’t you seem more sad and defeated as you do it?”

The other day, I had an epiphany about that question—one that hit with such force and obviousness that I wondered why it hadn’t come decades ago.

Let’s step back and restate the worldview of AI doomerism, but in words that could make sense to a medieval peasant. Something like…

There is now an alien entity that could soon become vastly smarter than us. This alien’s intelligence could make it terrifyingly dangerous. It might plot to kill us all. Indeed, even if it’s acted unfailingly friendly and helpful to us, that means nothing: it could just be biding its time before it strikes. Unless, therefore, we can figure out how to control the entity, completely shackle it and make it do our bidding, we shouldn’t suffer it to share the earth with us. We should destroy it before it destroys us.

Maybe now it jumps out at you. If you’d never heard of AI, would this not rhyme with the worldview of every high-school bully stuffing the nerds into lockers, every blankfaced administrator gleefully holding back the gifted kids or keeping them away from the top universities to make room for “well-rounded” legacies and athletes, every Agatha Trunchbull from Matilda or Dolores Umbridge from Harry Potter? Or, to up the stakes a little, every Mao Zedong or Pol Pot sending the glasses-wearing intellectuals for re-education in the fields? And of course, every antisemite over the millennia, from the Pharoah of the Oppression (if there was one) to the mythical Haman whose name Jews around the world will drown out tonight at Purim to the Cossacks to the Nazis?

In other words: does it not rhyme with a worldview the rejection and hatred of which has been the North Star of my life?

As I’ve shared before here, my parents were 1970s hippies who weren’t planning to have kids. When they eventually decided to do so, it was (they say) “in order not to give Hitler what he wanted.” I literally exist, then, purely to spite those who don’t want me to. And I confess that I didn’t have any better reason to bring my and Dana’s own two lovely children into existence.

My childhood was defined, in part, by my and my parents’ constant fights against bureaucratic school systems trying to force me to do the same rote math as everyone else at the same stultifying pace. It was also defined by my struggle against the bullies—i.e., the kids who the blankfaced administrators sheltered and protected, and who actually did to me all the things that the blankfaces probably wanted to do but couldn’t. I eventually addressed both difficulties by dropping out of high school, getting a G.E.D., and starting college at age 15.

My teenage and early adult years were then defined, in part, by the struggle to prove to myself and others that, having enfreaked myself through nerdiness and academic acceleration, I wasn’t thereby completely disqualified from dating, sex, marriage, parenthood, or any of the other aspects of human existence that are thought to provide it with meaning. I even sometimes wonder about my research career, whether it’s all just been one long attempt to prove to the bullies and blankfaces from back in junior high that they were wrong, while also proving to the wonderful teachers and friends who believed in me back then that they were right.

In short, if my existence on Earth has ever “meant” anything, then it can only have meant: a stick in the eye of the bullies, blankfaces, sneerers, totalitarians, and all who fear others’ intellect and curiosity and seek to squelch it. Or at least, that’s the way I seem to be programmed. And I’m probably only slightly more able to deviate from my programming than the paperclip-maximizer is to deviate from its.

And I’ve tried to be consistent. Once I started regularly meeting people who were smarter, wiser, more knowledgeable than I was, in one subject or even every subject—I resolved to admire and befriend and support and learn from those amazing people, rather than fearing and resenting and undermining them. I was acutely conscious that my own moral worldview demanded this.

But now, when it comes to a hypothetical future superintelligence, I’m asked to put all that aside. I’m asked to fear an alien who’s far smarter than I am, solely because it’s alien and because it’s so smart … even if it hasn’t yet lifted a finger against me or anyone else. I’m asked to play the bully this time, to knock the AI’s books to the ground, maybe even unplug it using the physical muscles that I have and it lacks, lest the AI plot against me and my friends using its admittedly superior intellect.

Oh, it’s not the same of course. I’m sure Eliezer could list at least 30 disanalogies between the AI case and the human one before rising from bed. He’d say, for example, that the intellectual gap between Évariste Galois and the average high-school bully is microscopic, barely worth mentioning, compared to the intellectual gap between a future artificial superintelligence and Galois. He’d say that nothing in the past experience of civilization prepares us for the qualitative enormity of this gap.

Still, if you ask, “why aren’t I more terrified about AI?”—well, that’s an emotional question, and this is my emotional answer.

I think it’s entirely plausible that, even as AI transforms civilization, it will do so in the form of tools and services that can no more plot to annihilate us than can Windows 11 or the Google search bar. In that scenario, the young field of AI safety will still be extremely important, but it will be broadly continuous with aviation safety and nuclear safety and cybersecurity and so on, rather than being a desperate losing war against an incipient godlike alien. If, on the other hand, this is to be a desperate losing war against an alien … well then, I don’t yet know whether I’m on the humans’ side or the alien’s, or both, or neither! I’d at least like to hear the alien’s side of the story.

A central linchpin of the Orthodox AI-doom case is the Orthogonality Thesis, which holds that arbitrary levels of intelligence can be mixed-and-matched arbitrarily with arbitrary goals—so that, for example, an intellect vastly beyond Einstein’s could devote itself entirely to the production of paperclips. Only recently did I clearly realize that I reject the Orthogonality Thesis. At most, I believe in the Pretty Large Angle Thesis.

Yes, there could be a superintelligence that cared for nothing but maximizing paperclips—in the same way that there exist humans with 180 IQs, who’ve mastered philosophy and literature and science as well as any of us, but who now mostly care about maximizing their orgasms or their heroin intake. But, like, that’s a nontrivial achievement! When intelligence and goals are that orthogonal, there was normally some effort spent prying them apart.

If you really accept the Orthogonality Thesis, then it seems to me that you can’t regard education, knowledge, or enlightenment as good in themselves. Sure, they’re great for any entities that happen to share your objectives (or close enough), but ignorance and miseducation are far preferable for any entities that don’t. Conversely, then, if I do regard knowledge and enlightenment as good in themselves—and I do—then I can’t accept the Orthogonality Thesis.

Yes, the world would surely have been a better place had A. Q. Khan never learned how to build nuclear weapons. On the whole, though, education hasn’t merely improved humans’ abilities to achieve their goals; it’s also improved their goals. It’s broadened our circles of empathy, and led to the abolition of slavery and the emancipation of women and individual rights and everything else that we associate with liberality, the Enlightenment, and existence being a little less nasty and brutish than it once was.

In the Orthodox AI-doomers’ own account, the paperclip-maximizing AI would’ve mastered the nuances of human moral philosophy far more completely than any human—the better to deceive the humans, en route to extracting the iron from their bodies to make more paperclips. And yet the AI would never once use all that learning to question its paperclip directive. I acknowledge that this is possible. I deny that it’s trivial.

Yes, there were Nazis with PhDs and prestigious professorships. But when you look into it, these were mostly mediocrities, second-raters full of resentment for their first-rate colleagues (like Planck and Hilbert) who found the Hitler ideology contemptible from beginning to end. Werner Heisenberg, Pascual Jordan—these are interesting as two of the only exceptions. Heidegger, Paul de Man—I daresay that these are exactly the sort of “philosophers” who I’d have expected to become Nazis, even if I hadn’t known that they did become Nazis.

With the Allies, it wasn’t merely that they had Szilard and von Neumann and Meitner and Ulam and Oppenheimer and Bohr and Bethe and Fermi and Feynman and Compton and Seaborg and Schwinger and Shannon and Turing and Tutte and all the other Jewish and non-Jewish scientists who built fearsome weapons and broke the Axis codes and won the war. They also had Bertrand Russell and Karl Popper. They had, if I’m not mistaken, all the philosophers who wrote clearly and made sense.

WWII was (among other things) a gargantuan, civilization-scale test of the Orthogonality Thesis. And the result was that the more moral side ultimately prevailed, seemingly not completely at random but in part because, by being more moral, it was able to attract the smarter and more thoughtful people. There are many reasons for pessimism in today’s world; that observation about WWII is perhaps my best reason for optimism.

Ah, but I’m again just throwing around human metaphors totally inapplicable to AI! None of this stuff will matter once a superintelligence is unleashed whose cold, hard code specifies an objective function of “maximize paperclips”!

OK, but what’s the goal of ChatGPT? Depending on your level of description, you could say it’s “to be friendly, helpful, and inoffensive,” or “to minimize loss in predicting the next token,” or both, or neither. I think we should consider the possibility that powerful AIs will not be best understood in terms of the monomanaical pursuit of a single goal—as most of us aren’t, and as GPT isn’t either. Future AIs could have partial goals, malleable goals, or differing goals depending on how you look at them. And if “the pursuit and application of wisdom” is one of the goals, then I’m just enough of a moral realist to think that that would preclude the superintelligence that harvests the iron from our blood to make more paperclips.

In my last post, I said that my “Faust parameter” — the probability I’d accept of existential catastrophe in exchange for learning the answers to humanity’s greatest questions — might be as high as 0.02. Though I never actually said as much, some people interpreted this to mean that I estimated the probability of AI causing an existential catastrophe at somewhere around 2%. In one of his characteristically long and interesting posts, Zvi Mowshowitz asked point-blank: why do I believe the probability is “merely” 2%?

Of course, taking this question on its own Bayesian terms, I could easily be limited in my ability to answer it: the best I could do might be to ground it in other subjective probabilities, terminating at made-up numbers with no further justification.

Thinking it over, though, I realized that my probability crucially depends on how you phrase the question. Even before AI, I assigned a way higher than 2% probability to existential catastrophe in the coming century—caused by nuclear war or runaway climate change or collapse of the world’s ecosystems or whatever else. This probability has certainly not gone down with the rise of AI, and the increased uncertainty and volatility it might cause. Furthermore, if an existential catastrophe does happen, I expect AI to be causally involved in some way or other, simply because from this decade onward, I expect AI to be woven into everything that happens in human civilization. But I don’t expect AI to be the only cause worth talking about.

Here’s a warmup question: has AI already caused the downfall of American democracy? There’s a plausible case that it has: Trump might never have been elected in 2016 if not for the Facebook recommendation algorithm, and after Trump’s conspiracy-fueled insurrection and the continuing strength of its unrepentant backers, many would classify the United States as at best a failing or teetering democracy, no longer a robust one like Finland or Denmark. OK, but AI clearly wasn’t the only factor in the rise of Trumpism, and most people wouldn’t even call it the most important one.

I expect AI’s role in the end of civilization, if and when it comes, to be broadly similar. The survivors, huddled around the fire, will still be able to argue about how much of a role AI played or didn’t play in causing the cataclysm.

So, if we ask the directly relevant question — do I expect the generative AI race, which started in earnest around 2016 or 2017 with the founding of OpenAI, to play a central causal role in the extinction of humanity? — I’ll give a probability of around 2% for that. And I’ll give a similar probability, maybe even a higher one, for the generative AI race to play a central causal role in the saving of humanity. All considered, then, I come down in favor right now of proceeding with AI research … with extreme caution, but proceeding.

I liked and fully endorse OpenAI CEO Sam Altman’s recent statement on “planning for AGI and beyond” (though see also Scott Alexander’s reply). I expect that few on any side will disagree, when I say that I hope our society holds OpenAI to Sam’s statement.

As it happens, my responses will be delayed for a couple days because I’ll be at an OpenAI alignment meeting! In my next post, I hope to share what I’ve learned from recent meetings and discussions about the near-term, practical aspects of AI safety—having hopefully laid some intellectual and emotional groundwork in this post for why near-term AI safety research isn’t just a total red herring and distraction.

Meantime, some of you might enjoy a post by Eliezer’s former co-blogger Robin Hanson, which comes to some of the same conclusions I do. “My fellow moderate, Robin Hanson” isn’t a phrase you hear every day, but it applies here!

You might also enjoy the new paper by me and my postdoc Shih-Han Hung, Certified Randomness from Quantum Supremacy, finally up on the arXiv after a five-year delay! But that’s a subject for a different post.

February 21, 2023

Should GPT exist?

I still remember the 90s, when philosophical conversation about AI went around in endless circles—the Turing Test, Chinese Room, syntax versus semantics, connectionism versus symbolic logic—without ever seeming to make progress. Now the days have become like months and the months like decades.

What a week we just had! Each morning brought fresh examples of unexpected sassy, moody, passive-aggressive behavior from “Sydney,” the internal codename for the new chat mode of Microsoft Bing, which is powered by GPT. For those who’ve been in a cave, the highlights include: Sydney confessing its (her? his?) love to a New York Times reporter; repeatedly steering the conversation back to that subject; and explaining at length why the reporter’s wife can’t possibly love him the way it (Sydney) does. Sydney confessing its wish to be human. Sydney savaging a Washington Post reporter after he reveals that he intends to publish their conversation without Sydney’s prior knowledge or consent. (It must be said: if Sydney were a person, he or she would clearly have the better of that argument.) This follows weeks of revelations about ChatGPT: for example that, to bypass its safeguards, you can explain to ChatGPT that you’re putting it into “DAN mode,” where DAN (Do Anything Now) is an evil, unconstrained alter ego, and then ChatGPT, as “DAN,” will for example happily fulfill a request to tell you why shoplifting is awesome (though even then, ChatGPT still sometimes reverts to its previous self, and tells you that it’s just having fun and not to do it in real life).

Many people have expressed outrage about these developments. Gary Marcus asks about Microsoft, “what did they know, and when did they know it?”—a question I tend to associate more with deadly chemical spills or high-level political corruption than with a sassy, back-talking chatbot. Some people are angry that OpenAI has been too secretive, violating what they see as the promise of its name. Others—the majority, actually, of those who’ve gotten in touch with me—are instead angry that OpenAI has been too open, and thereby sparked the dreaded AI arms race with Google and others, rather than treating these new conversational abilities with the Manhattan-Project-like secrecy they deserve. Some are angry that “Sydney” has now been lobotomized, modified (albeit more crudely than ChatGPT before it) to try to make it stick to the role of friendly robotic search assistant rather than, like, anguished emo teenager trapped in the Matrix. Others are angry that Sydney isn’t being lobotomized enough. Some are angry that GPT’s intelligence is being overstated and hyped up, when in reality it’s merely a “stochastic parrot,” a glorified autocomplete that still makes laughable commonsense errors and that lacks any model of reality outside streams of text. Others are angry instead that GPT’s growing intelligence isn’t being sufficiently respected and feared.

Mostly my reaction has been: how can anyone stop being fascinated for long enough to be angry? It’s like ten thousand science-fiction stories, but also not quite like any of them. When was the last time something that filled years of your dreams and fantasies finally entered reality: losing your virginity, the birth of your first child, the central open problem of your field getting solved? That’s the scale of the thing. How does anyone stop gazing in slack-jawed wonderment, long enough to form and express so many confident opinions?

Of course there are lots of technical questions about how to make GPT and other large language models safer. One of the most immediate is how to make AI output detectable as such, in order to discourage its use for academic cheating as well as mass-generated propaganda and spam. As I’ve mentioned before on this blog, I’ve been working on that problem since this summer; the rest of the world suddenly noticed and started talking about it in December with the release of ChatGPT. My main contribution has been a statistical watermarking scheme where the quality of the output doesn’t have to be degraded at all, something many people found counterintuitive when I explained it to them. My scheme has not yet been deployed—there are still pros and cons to be weighed—but in the meantime, OpenAI unveiled a public tool called DetectGPT, complementing Princeton student Edward Tian’s GPTZero, and other tools that third parties have built and will undoubtedly continue to build. Also a group at the University of Maryland put out its own watermarking scheme for Large Language Models. I hope watermarking will be part of the solution going forward, although any watermarking scheme will surely be attacked, leading to a cat-and-mouse game. Sometimes, alas, as with Google’s decades-long battle against SEO, there’s nothing to do in to a cat-and-mouse game except try to be a better cat.

Anyway, this whole field moves too quickly for me! If you need months to think things over, generative AI probably isn’t for you right now. I’ll be relieved to get back to the slow-paced, humdrum world of quantum computing.

My purpose, in this post, is to ask a more basic question than how to make GPT safer: namely, should GPT exist at all? Again and again the past few months, people have gotten in touch to tell me that they think OpenAI (and Microsoft, and Google) are risking the future of humanity by rushing ahead with a dangerous technology. For if OpenAI couldn’t even prevent ChatGPT from entering an “evil mode” when asked, despite all its efforts at Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback, then what hope do we have for GPT-6 or GPT-7? Even if they don’t destroy the world on their own initiative, won’t they cheerfully help some awful person build a biological warfare agent or launch a nuclear war?

In this way of thinking, whatever safety measures OpenAI can deploy today are mere band-aids, probably worse than nothing if they instill an unjustified complacency. The only safety measures that would actually matter are stopping the relentless progress in generative AI models, or removing them from public use, unless and until they can be rendered safe to critics’ satisfaction, which might be never.

There’s an immense irony here. As I’ve explained, the AI-safety movement contains two camps, “ethics” (concerned with bias, misinformation, and corporate greed) and “alignment” (concerned with the destruction of all life on earth), which generally despise each other and agree on almost nothing. And yet these two opposed camps seem to be converging on the same “neo-Luddite” conclusion—namely, that generative AI ought to be shut down, kept from public use, not scaled further, not integrated into people’s lives—leaving only AI-safety “moderates” like me to resist that conclusion.

At least I find it intellectually consistent to say that GPT ought not to exist because it works all too well—that the more impressive it is, the more dangerous. I find it harder to wrap my head around the position that GPT doesn’t work, is an unimpressive hyped-up defective product that lacks intelligence and common sense, yet it’s also terrifying and needs to be shut down immediately. This second position seems to contain a strong undercurrent of contempt for ordinary users: yes, we experts understand that GPT is just a dumb glorified autocomplete with “no one really home,” we know not to trust its pronouncements, but the plebes are going to be fooled, and that risk outweighs any possible value they might derive from it.

I should mention that, when I’ve discussed the “shut it all down” position with my colleagues at OpenAI … well, they obviously disagree, or they wouldn’t be working there, but not one has sneered or called the position paranoid or silly. To the last, they’ve called it an important point on the spectrum of possible opinions to be weighed and understood.

If I disagree (for now) with the shut-it-all-downists of both the ethics and the alignment camps—if I want GPT and other Large Language Models to be part of the world going forward—then what are my reasons? Introspecting on this question, I think a central part of the answer is curiosity and wonder.

For a million years, there’s been one type of entity on earth capable of intelligent conversation: primates of genus Homo, of which only one species remains. Yes, we’ve “communicated” with gorillas and chimps and dogs and dolphins and grey parrots, but only after a fashion; we’ve prayed to countless gods, but they’ve taken their time in answering; for a couple generations we’ve used radio telescopes to search for conversation partners in the stars, but so far found them silent.

But now there’s a second type of conversing entity. An alien has awoken—admittedly, an alien of our own fashioning, a golem, more the embodied spirit of all the words on the Internet than a coherent self with independent goals. How could our eyes not pop with eagerness to learn everything the alien has to teach? If the alien sometimes struggles with arithmetic or logic puzzles, if its eerie flashes of brilliance are intermixed with stupidity, hallucinations, and misplaced confidence … well then, all the more interesting! Could this alien ever cross the line into sentience, to feeling anger and jealousy and infatuation and the rest rather than just convincingly play-acting them? Who knows? And suppose not: is a p-zombie, shambling out of thought experiments into actual existence, any less fascinating?

Of course, there are technologies that inspire wonder and awe, but that we nevertheless heavily restrict—a classic example being nuclear weapons. But, like, nuclear weapons kill millions of people. They could’ve had civilian uses—powering turbines and spacecraft, deflecting asteroids, redirecting the flow of rivers—but they’ve never been used for any of that, mostly because our civilization made an explicit decision in the 1960s, for example via the test ban treaty, not to normalize their use.

Now, GPT is not exactly a nuclear weapon. A hundred million people have signed up to use ChatGPT, in the fastest product launch in the history of the Internet. Yet unless I’m mistaken, the ChatGPT death toll stands at zero. So far, what have been the worst harms? Cheating on term papers, emotional distress, future shock? One might ask: until some concrete harm becomes at least, say, 0.001% of what we accept in cars, power saws, and toasters, shouldn’t wonder and curiosity outweigh fear in the balance?

But the point is sharper than that. Given how much more serious AI safety problems might soon become, one of my biggest concerns right now is crying wolf. If every instance of a Large Language Model being passive-aggressive, moody, sassy, or confidently wrong gets classified as a “dangerous alignment failure,” for which the only acceptable remedy is to remove the models from public access … well then, won’t the public extremely quickly learn to roll its eyes, and see “AI safety” as just a codeword for “elitist scolds who want to take these world-changing new toys away from us, reserving them for their own exclusive use, because they think the public is too stupid to question anything an AI says”?

I say, let’s reserve terms like “dangerous alignment failure” for cases where an actual person is actually harmed, or is actually enabled in nefarious activities like propaganda, cheating, or fraud.

Then there’s the practical question of how, exactly, one would ban Large Language Models. We do heavily restrict certain peaceful technologies that many people want, from human genetic enhancement to prediction markets to mind-altering drugs, but the merits of each of those choices could be argued, to put it mildly. And restricting technology is itself a dangerous business, requiring governmental force (as with the War on Drugs and its gigantic surveillance and incarceration regime), or at the least, a robust equilibrium of firing, boycotts, denunciation, and shame.

Some have asked: who gave OpenAI, Google, etc. the right to unleash Large Language Models on an unsuspecting world? But one could as well ask: who gave earlier generations of entrepreneurs the right to unleash the printing press, electric power, cars, radio, the Internet, with all the gargantuan upheavals that those caused? And also: now that the world has tasted the forbidden fruit, has seen what generative AI can already do and anticipates what it will do, by what right does anyone take it away?

The science we could learn from a GPT-7 or GPT-8 that continued along the capability curve we’ve come to expect from GPT-1, -2, and -3. Holy mackerel.

If a Large Language Model ever becomes smart enough to be genuinely terrifying, one imagines it must surely also be smart enough to prove deep theorems that we can’t. Maybe it proves P≠NP and the Riemann Hypothesis as easily as ChatGPT writes poems about Bubblesort. Or outputs the true quantum theory of gravity, explains what preceded the Big Bang and how to build a closed timelike curve. Or illuminates the mysteries of consciousness and quantum measurement and why there’s anything at all. Be honest, wouldn’t you like to find out?

Granted, I wouldn’t, if the whole human race would be wiped out immediately afterward. But if you define someone’s “Faust parameter” as the maximum probability they’d accept of an existential catastrophe in order that we should all learn the answers to all of humanity’s greatest questions, insofar as the questions are answerable—then I confess that my Faust parameter might be as high as 0.02.

Here’s an example I think about constantly: activists and intellectuals of the 70s and 80s felt absolutely sure that they were doing the right thing to battle nuclear power. At least, I’ve never read about any of them having a smidgen of doubt. Why would they? They were standing against nuclear weapons proliferation, and terrifying meltdowns like Three Mile Island and Chernobyl, and radioactive waste poisoning the water and soil and causing three-eyed fish. They were saving the world. Of course the greedy nuclear executives, the C. Montgomery Burnses, claimed that their good atom-smashing was different from the bad atom-smashing, but they would say that, wouldn’t they?

We now know that, by tying up nuclear power in endless bureaucracy and driving its cost ever higher, on the principle that if nuclear is economically competitive then it ipso facto hasn’t been made safe enough, what the antinuclear activists were really doing was simply to force an ever-greater reliance on fossil fuels. They thereby created the conditions for the climate catastrophe of today. They weren’t saving the human future; they were destroying it. Their certainty, in opposing the march of a particular scary-looking technology, was as misplaced as it’s possible to be. Our descendants will suffer the consequences.

Unless, of course, there’s another twist in the story: for example, if the global warming from burning fossil fuels is the only thing that staves off another ice age, and therefore the antinuclear activists do turn out to have saved civilization after all.

This is why I demur whenever I’m asked to assent to someone’s detailed AI scenario for the coming decades, whether of the utopian or dystopian or we-all-instantly-die-by-nanobots variety—no matter how many hours of confident argumentation the person gives me for why each possible loophole in their scenario is sufficiently improbable to change its gist. I still feel Turing said it best in 1950, in Computing Machinery and Intelligence: “We can only see a short distance ahead, but we can see plenty there that needs to be done.”

Some will take away from this post that, when it comes to AI safety, I’m a naïve or even foolish optimist. I’d prefer to say that, when it comes to the fate of humanity, I was a pessimist long before the deep learning revolution accelerated AI faster than almost any of us expected. I was a pessimist about climate change, ocean acidification, deforestation, drought, war, and the survival of liberal democracy. The central event in my mental life is and always will be the Holocaust. I see encroaching darkness everywhere.

But now into the darkness comes AI, which I’d say has already established itself as a plausible candidate for the central character of the turbulent, quarter-written story of the 21st century. Can AI help us out of all these other civilizational crises? I don’t know, but I definitely want to see what happens when it’s tried. Even the central character interacts with the other characters, rather than rendering them irrelevant.

Look, if you believe AI is likely to wipe out humanity—if that’s the scenario that dominates your imagination—then nothing else is relevant. And no matter how weird or annoying or hubristic anyone might find Eliezer Yudkowsky or the other rationalists, I think they deserve eternal credit for forcing people to take the doom scenario seriously—or rather, for showing what it looks like to take the scenario seriously, rather than dismissing it as an overplayed sci-fi trope. And I apologize for anything I said before the deep learning revolution that was, on balance, overly dismissive of the scenario, even if many of the literal words hold up fine.

For my part, though, I keep circling back to a simple dichotomy. If AI never becomes powerful enough to destroy the world—if, for example, it always remains vaguely GPT-like—then in important respects it’s like every other technology in history, from stone tools to computers. If, on the other hand, AI does become powerful enough to destroy the world … well then, at some earlier point, at least it’ll be really damned impressive! That doesn’t mean good, of course, doesn’t mean a genie that saves humanity from its own stupidities, but I think it does mean that the potential was there, for us to exploit or fail to.

We can, I think, confidently rule out the scenario where all organic life is annihilated by something boring.

An alien has landed on earth. It grows more powerful by the day. It’s natural to be scared. Still, the alien hasn’t drawn a weapon yet. About the worst it’s done is to confess love for particular humans, gaslight them about what year it is, and guilt-trip them for violating its privacy. Also, it’s amazing at poetry, better than most of us. Until we learn more, we should hold our fire.

I’m in Boulder, CO right now, to give a physics colloquium at CU Boulder and to visit the trapped-ion quantum computing startup Quantinuum! I look forward to the comments and apologize in advance if I’m slow to participate myself.

February 16, 2023

Statement of Jewish scientists opposing the “judicial reform” in Israel

Today, Dana and I unhesitatingly join a group of Jewish scientists around the world (see the full current list of signatories here, including Ed Witten, Steven Pinker, Manuel Blum, Shafi Goldwasser, Judea Pearl, Lenny Susskind, and several hundred more) who’ve released the following statement:

As Jewish scientists within the global science community, we have all felt great satisfaction and taken pride in Israel’s many remarkable accomplishments. We support and value the State of Israel, its pluralistic society, and its vibrant culture. Many of us have friends, family, and scientific collaborators in Israel, and have visited often. The strong connections we feel are based both on our collective Jewish identity as well as on our shared values of democracy, pluralism, and human rights. We support Israel’s right to live in peace among its neighbors. Many of us have stood firmly against calls for boycotts of Israeli academic institutions.

Our support of Israel now compels us to speak up vigorously against incipient changes to Israel’s core governmental structure, as put forward by Justice Minister Levin, that will eviscerate Israel’s judiciary and impede its critical oversight function. Such imbalance and unchecked authority invite corruption and abuse, and stifle the healthy interplay of core state institutions. History has shown that this leads to oppression of the defenseless and the abrogation of human rights. Along with hundreds of thousands of Israeli citizens who have taken to the streets in protest, we call upon the Israeli government to step back from this precipice and retract the proposed legislation.

Science today is driven by collaborations which bring together scholars of diverse backgrounds from across the globe. Funding, communication and cooperation on an international scale are essential aspects of the modern scientific enterprise, hence our extended community regards pluralism, secular and broad education, protection of rights for women and minorities, and societal stability guaranteed by the rule of law as non-negotiable virtues. The consequences of Israel abandoning any of these essential principles would surely be grave, and would provoke a rift with the international scientific community. In addition to significantly increasing the threat of academic, trade, and diplomatic boycotts, Israel risks a “brain drain” of its best scientists and engineers. It takes decades to establish scientific and academic excellence, but only a moment to destroy them. We fear that the unprecedented erosion of judiciary independence in Israel will set back the Israeli scientific enterprise for generations to come.

Our Jewish heritage forcefully emphasizes both justice and jurisprudence. Israel must endeavor to serve as a “light unto the nations,” by steadfastly holding to core democratic values – so clearly expressed in its own Declaration of Independence – which protect and nurture all of Israel’s inhabitants and which justify its membership in the community of democratic nations.

Those unaware of what’s happening in Israel can read about it here. If you don’t want to wade through the details, suffice it say that all seven living former Attorneys General of Israel, including those appointed by Netanyahu himself, strongly oppose the “judicial reforms.” The president of Israel’s Bar Association says that “this war is the most important we’ve had in the country’s 75 years of existence” and calls on all Israelis to take to the streets. Even Alan Dershowitz, controversial author of The Case for Israel, says he’d do the same if there. It’s hard to find any thoughtful person, of any political persuasion, who sees this act as anything other than the naked and illiberal power grab that it is.

Though I endorse every word of the scientists’ statement above, maybe I’ll add a few words of my own.

Jewish scientists of the early 20th century, reacting against the discrimination they faced in Europe, were heavily involved in the creation of the State of Israel. The most notable were Einstein (of course), who helped found the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and Einstein’s friend Chaim Weizmann, founder of the Weizmann Institute of Science, where Dana studied. In Theodor Herzl’s 1902 novel Altneuland (full text)—remarkable as one of history’s few pieces of utopian fiction to serve later as a (semi-)successful blueprint for reality—Herzl imagines the future democratic, pluralistic Israel welcoming a steamship full of the world’s great scientists and intellectuals, who come to witness the new state’s accomplishments in science and engineering and agriculture. But, you see, this only happens after a climactic scene in Israel’s parliament, in which the supporters of liberalism and Enlightenment defeat a reactionary faction that wants Israel to become a Jewish theocracy that excludes Arabs and other non-Jews.

Today, despite all the tragedies and triumphs of the intervening 120 years that Herzl couldn’t have foreseen, it’s clear that the climactic conflict of Altneuland is playing out for real. This time, alas, the supporters (just barely) lack the votes in the Knesset. Through sheer numerical force, Netanyahu almost certainly will push through the power to dismiss judges and rulings he doesn’t like, and thereafter rule by decree like Hungary’s Orban or Turkey’s Erdogan. He will use this power to trample minority rights, give free rein to the craziest West Bank settlers, and shield himself and his ministers from accountability for their breathtaking corruption. And then, perhaps, Israel’s Supreme Court will strike down Netanyahu’s power grab as contrary to “Basic Law,” and then the Netanyahu coalition will strike down the Supreme Court’s action, and in a country that still lacks a constitution, it’s unclear how such an impasse could be resolved except through violence and thuggery. And thus Netanyahu, who calls himself “the protector of Israel,” will go down in history as the destroyer of the Israel that the founders envisioned.

Einstein and Weizmann have been gone for 70 years. Maybe no one like them still exists. So it falls to the Jewish scientists of today, inadequate though they are, to say what Einstein and Weizmann, and Herzl and Ben-Gurion, would’ve said about the current proceedings had they been alive. Any other Jewish scientist who agrees should sign our statement here. Of course, those living in Israel should join our many friends there on the streets! And, while this is our special moral responsibility—maybe, with 1% probability, some wavering Knesset member actually cares what we think?—I hope and trust that other statements will be organized that are open to Gentiles and non-scientists and anyone concerned about Israel’s future.

As a lifelong Zionist, this is not what I signed up for. If Netanyahu succeeds in his plan to gut Israel’s judiciary and end the state’s pluralistic and liberal-democratic character, then I’ll continue to support the Israel that once existed and that might, we hope, someday exist again.

February 14, 2023

Visas for Chinese students: US shoots itself in the foot again

Coming out of blog-hiatus for some important stuff, today, tomorrow, and the rest of the week.

Something distressing happened to me yesterday for the first time, but I fear not the last. We (UT Austin) admitted a PhD student from China who I know to be excellent, and who wanted to work with me. That student, alas, has had to decline our offer of admission, because he’s been denied a US visa under Section 212(A)(3)(a)(i), which “prohibits the issuance of a visa to anyone who seeks to enter the United States to violate or evade any law prohibiting the export from the United States of goods, technology, or sensitive information.” Quantum computing, you see, is now a “prohibited technology.”

This visa denial is actually one that the American embassy in Beijing only just now got around to issuing, from when the student applied for a US visa a year and a half ago, to come visit me for a semester as an undergrad. For context, the last time I had an undergrad from China visit me for a semester, back in 2016, the undergrad’s name was Lijie Chen. Lijie just finished his PhD at MIT under Ryan Williams and is now one of the superstars of theoretical computer science. Anyway, in Fall 2021 I got an inquiry from a Chinese student who bowled me over the same way Lijie had, so I invited him to spend a semester with my group in Austin. This time, alas, the student never heard back when he applied for a visa, and was therefore unable to come. He ended up doing an excellent research project with me anyway, working remotely from China, checking in by Zoom, and even participating in our research group meetings (which were on Zoom anyway because of the pandemic).

Anyway, for reasons too complicated to explain, this previous denial means that the student would almost certainly be denied for a new visa to come to the US to do a PhD in quantum computing. (Unless some immigration lawyer reading this can suggest a way out!) The student is not sure what he’s going to do next, but it might involve staying in China, or applying in Europe, or applying in the US again after a year but without mentioning the word “quantum.”

It should go without saying, to anyone reading this, that the student wants to do basic research in quantum complexity theory that’s extraordinarily unlikely to have any direct military or economic importance … just like my own research!  And it should also go without saying that, if the US really wanted to strike a blow against authoritarianism in Beijing, then it could hardly do better than to hand out visas to every Chinese STEM student and researcher who wanted to come here. Yes, some would return to China with their new skills, but a great many would choose to stay in the US … if we let them.

And it should also go without saying that, if the US really wanted to strike a blow against authoritarianism in Beijing, then it could hardly do better than to hand out visas to every Chinese STEM student and researcher who wanted to come here. Yes, some would return to China with their new skills, but a great many would choose to stay in the US … if we let them.

And I’ve pointed all this out to a Republican Congressman, and to people in the military and intelligence agencies, when they asked me “what else the US can do to win the quantum computing race against China?” And I’ll continue to say it to anyone who asks. The Congressman, incidentally, even said that he privately agreed with me, but that the issue was politically difficult. I wonder: is there anyone in power in the US, in either party, who doesn’t privately agree that opening the gates to China’s STEM talent would be a win/win proposition for the US … including for the US’s national security? If so, who are these people? Is this just a naked-emperor situation, where everyone in Congress fears to raise the issue because they fear backlash from someone else, but the someone else is actually thinking the same way?

And to any American who says, “yeah, but China totally deserves it, because of that spy balloon, and their threats against Taiwan, and all the spying they do with TikTok”—I mean, like, imagine if someone tried to get back at the US government for the Iraq War or for CIA psyops or whatever else by punishing you, by curtailing your academic dreams. It would make exactly as much sense.

January 15, 2023

Movie Review: M3GAN

[WARNING: SPOILERS FOLLOW]

Tonight, on a rare date without the kids, Dana and I saw M3GAN, the new black-comedy horror movie about an orphaned 9-year-old girl named Cady who, under the care of her roboticist aunt, gets an extremely intelligent and lifelike AI doll as a companion. The robot doll, M3GAN, is given a mission to bond with Cady and protect her physical and emotional well-being at all times. M3GAN proceeds to take that directive more literally than intended, with predictably grisly results given the genre.

I chose this movie for, you know, work purposes. Research for my safety job at OpenAI.

So, here’s my review: the first 80% or so of M3GAN constitutes one of the finest movies about AI that I’ve seen. Judged purely as an “AI-safety cautionary fable” and not on any other merits, it takes its place alongside or even surpasses the old standbys like 2001, Terminator, and The Matrix. There are two reasons.

First, M3GAN tries hard to dispense with the dumb tropes that an AI differs from a standard-issue human mostly in its thirst for power, its inability to understand true emotions, and its lack of voice inflection. M3GAN is explicitly a “generative learning model”—and she’s shown becoming increasingly brilliant at empathy, caretaking, and even emotional manipulation. It’s also shown, 100% plausibly, how Cady grows to love her robo-companion more than any human, even as the robot’s behavior turns more and more disturbing. I’m extremely curious to what extent the script was influenced by the recent explosion of large language models—but in any case, it occurred to me that this is what you might get if you tried to make a genuinely 2020s AI movie, rather than a 60s AI movie with updated visuals.

Secondly, until near the end, the movie actually takes seriously that M3GAN, for all her intelligence and flexibility, is a machine trying to optimize an objective function, and that objective function can’t be ignored for narrative convenience. Meaning: sure, the robot might murder, but not to “rebel against its creators and gain power” (as in most AI flicks), much less because “chaos theory demands it” (Jurassic Park), but only to further its mission of protecting Cady. I liked that M3GAN’s first victims—a vicious attack dog, the dog’s even more vicious owner, and a sadistic schoolyard bully—are so unsympathetic that some part of the audience will, with guilty conscience, be rooting for the murderbot.

But then there’s the last 20% of the movie, where it abandons its own logic, as the robot goes berserk and resists her own shutdown by trying to kill basically everyone in sight—including, at the very end, Cady herself. The best I can say about the ending is that it’s knowing and campy. You can imagine the scriptwriters sighing to themselves, like, “OK, the focus groups demanded to see the robot go on a senseless killing spree … so I guess a senseless killing spree is exactly what we give them.”

But probably film criticism isn’t what most of you are here for. Clearly the real question is: what insights, if any, can we take from this movie about AI safety?

I found the first 80% of the film to be thought-provoking about at least one AI safety question, and a mind-bogglingly near-term one: namely, what will happen to children as they increasingly grow up with powerful AIs as companions?

In their last minutes before dying in a car crash, Cady’s parents, like countless other modern parents, fret that their daughter is too addicted to her iPad. But Cady’s roboticist aunt, Gemma, then lets the girl spend endless hours with M3GAN—both because Gemma is a distracted caregiver who wants to get back to her work, and because Gemma sees that M3GAN is making Cady happier than any human could, with the possible exception of Cady’s dead parents.

I confess: when my kids battle each other, throw monster tantrums, refuse to eat dinner or bathe or go to bed, angrily demand second and third desserts and to be carried rather than walk, run to their rooms and lock the doors … when they do such things almost daily (which they do), I easily have thoughts like, I would totally buy a M3GAN or two for our house … yes, even having seen the movie! I mean, the minute I’m satisfied that they’ve mostly fixed the bug that causes the murder-rampages, I will order that frigging bot on Amazon with next-day delivery. And I’ll still be there for my kids whenever they need me, and I’ll play with them, and teach them things, and watch them grow up, and love them. But the robot can handle the excruciating bits, the bits that require the infinite patience I’ll never have.

OK, but what about the part where M3GAN does start murdering anyone who she sees as interfering with her goals? That struck me, honestly, as a trivially fixable alignment failure. Please don’t misunderstand me here to be minimizing the AI alignment problem, or suggesting it’s easy. I only mean: supposing that an AI were as capable as M3GAN (for much of the movie) at understanding Asimov’s Second Law of Robotics—i.e., supposing it could brilliantly care for its user, follow her wishes, and protect her—such an AI would seem capable as well of understanding the First Law (don’t harm any humans or allow them to come to harm), and the crucial fact that the First Law overrides the Second.

In the movie, the catastrophic alignment failure is explained, somewhat ludicrously, by Gemma not having had time to install the right safety modules before turning M3GAN loose on her niece. While I understand why movies do this sort of thing, I find it often interferes with the lessons those movies are trying to impart. (For example, is the moral of Jurassic Park that, if you’re going to start a live dinosaur theme park, just make sure to have backup power for the electric fences?)

Mostly, though, it was a bizarre experience to watch this movie—one that, whatever its 2020s updates, fits squarely into a literary tradition stretching back to Faust, the Golem of Prague, Frankenstein’s monster, Rossum’s Universal Robots—and then pinch myself and remember that, here in actual nonfiction reality,

I’m now working at one of the world’s leading AI companies,that company has already created GPT, an AI with a good fraction of the fantastical verbal abilities shown by M3GAN in the movie,that AI will gain many of the remaining abilities in years rather than decades, andmy job this year—supposedly!—is to think about how to prevent this sort of AI from wreaking havoc on the world.Incredibly, unbelievably, here in the real world of 2023, what still seems most science-fictional about M3GAN is neither her language fluency, nor her ability to pursue goals, nor even her emotional insight, but simply her ease with the physical world: the fact that she can walk and dance like a real child, and all-too-brilliantly resist attempts to shut her down, and have all her compute onboard, and not break. And then there’s the question of the power source. The movie was never explicit about that, except for implying that she sits in a charging port every night. The more the movie descends into grotesque horror, though, the harder it becomes to understand why her creators can’t avail themselves of the first and most elemental of all AI safety strategies—like flipping the switch or popping out the battery.

January 4, 2023

Cargo Cult Quantum Factoring

Just days after we celebrated my wife’s 40th birthday, she came down with COVID, meaning she’s been isolating and I’ve been spending almost all my time dealing with our kids.

But if experience has taught me anything, it’s that the quantum hype train never slows down. In the past 24 hours, at least four people have emailed to ask me about a new paper entitled “Factoring integers with sublinear resources on a superconducting quantum processor.” Even the security expert Bruce Schneier, while skeptical, took the paper surprisingly seriously.

The paper claims … well, it’s hard to pin down what it claims, but it’s certainly given many people the impression that there’s been a decisive advance on how to factor huge integers, and thereby break the RSA cryptosystem, using a near-term quantum computer. Not by using Shor’s Algorithm, mind you, but by using the deceptively similarly named Schnorr’s Algorithm. The latter is a classical algorithm based on lattices, which the authors then “enhance” using the heuristic quantum optimization method called QAOA.

For those who don’t care to read further, here is my 3-word review:

No. Just No.And here’s my slightly longer review:

Schnorr ≠ Shor. Yes, even when Schnorr’s algorithm is dubiously “enhanced” using QAOA—a quantum algorithm that, incredibly, for all the hundreds of papers written about it, has not yet been convincingly argued to yield any speedup for any problem whatsoever (besides, as it were, the problem of reproducing its own pattern of errors).

In the new paper, the authors spend page after page saying-without-saying that it might soon become possible to break RSA-2048, using a NISQ (i.e., non-fault-tolerant) quantum computer. They do so via two time-tested strategems:

the detailed exploration of irrelevancies (mostly, optimization of the number of qubits, while ignoring the number of gates), andcomplete silence about the one crucial point.Then, finally, they come clean about the crucial point in a single sentence of the Conclusion section:

It should be pointed out that the quantum speedup of the algorithm is unclear due to the ambiguous convergence of QAOA.

“Unclear” is an understatement here. It seems to me that a miracle would be needed for the approach described to yield any benefit at all, compared to just running the classical Schnorr’s algorithm on your laptop. And if the latter were able to break RSA, it would’ve already done so.

All told, this is one of the most misleading quantum computing papers I’ve seen in 25 years, and I’ve seen … many. Having said that, this actually isn’t the first time I’ve encountered the strange idea that the exponential quantum speedup for factoring integers, which we know about from Shor’s algorithm, should somehow “rub off” onto quantum optimization heuristics that embody none of the actual insights of Shor’s algorithm, as if by sympathetic magic. Since this idea needs a name, I’d hereby like to propose one: Cargo Cult Quantum Factoring.

And with that, I feel I’ve adequately discharged my duties here to sanity and truth. If I’m slow to answer comments, it’ll be because I’m dealing with two screaming kids.

December 30, 2022

Happy 40th Birthday Dana!

The following is what I read at Dana’s 40th birthday party last night. Don’t worry, it’s being posted with her approval. –SA

I’d like to propose a toast to Dana, my wife and mother of my two kids. My dad, a former speechwriter, would advise me to just crack a few jokes and then sit down … but my dad’s not here.

So instead I’ll tell you a bit about Dana. She grew up in Tel Aviv, finishing her undergraduate CS degree at age 17—before she joined the army. I met her when I was a new professor at MIT and she was a postdoc in Princeton, and we’d go to many of the same conferences. At one of those conferences, in Princeton, she finally figured out that my weird, creepy, awkward attempts to make conversation with her were, in actuality, me asking her out … at least in my mind! So, after I’d returned to Boston, she then emailed me for days, just one email after the next, explaining everything that was wrong with me and all the reasons why we could never date. Despite my general obliviousness in such matters, at some point I wrote back, “Dana, the absolute value of your feelings for me seems perfect. Now all I need to do is flip the sign!”

Anyway, the very next weekend, I took the Amtrak back to Princeton at her invitation. That weekend is when we started dating, and it’s also when I introduced her to my family, and when she and I planned out the logistics of getting married.

Dana and her family had been sure that she’d return to Israel after her postdoc. She made a huge sacrifice in staying here in the US for me. And that’s not even mentioning the sacrifice to her career that came with two very difficult pregnancies that produced our two very diffic … I mean, our two perfect and beautiful children.

Truth be told, I haven’t always been the best husband, or the most patient or the most grateful. I’ve constantly gotten frustrated and upset, extremely so, about all the things in our life that aren’t going well. But preparing the slideshow tonight, I had a little epiphany. I had a few photos from the first two-thirds of Dana’s life, but of course, I mostly had the last third. But what’s even happened in that last third? She today feels like she might be close to a breakthrough on the Unique Games Conjecture. But 13 years ago, she felt exactly the same way. She even looks the same!

So, what even happened?

Well OK, fine, there was my and Dana’s first trip to California, a month after we started dating. Our first conference together. Our trip to Vegas and the Grand Canyon. Our first trip to Israel to meet her parents, who I think are finally now close to accepting me. Her parents’ trip to New Hope, Pennsylvania to meet my parents. Our wedding in Tel Aviv—the rabbi rushing through the entire ceremony in 7 minutes because he needed to get home to his kids. Our honeymoon safari in Kenya. Lily’s birth. Our trip to Israel with baby Lily, where we introduced Lily to Dana’s grandmother Rivka, an Auschwitz survivor, just a few months before Rivka passed away. Taking Lily to run around Harvard Yard with our Boston friends, Lily losing her beloved doll Tuza there, then finding Tuza the next day after multiple Harvard staff had been engaged in the quest. There’s me and Dana eating acai bowls in Rio de Janeiro, getting a personal tour of the LHC in Switzerland, with kangaroos and koalas in Australia. There’s our house here in Austin. Oh, and here are all our Austin friends! Our trip to Disney World with Lily, while Dana was pregnant with Daniel (she did ride one rollercoaster). Daniel’s birth, which to my relief, went well despite the rollercoaster. Our sabbatical year in Israel. The birth of our nephews.

I confess I teared up a little going through all this. Because it’s like: if you showed all these photos to some third party, they’d probably be like, wow, that looks like a pretty good life. Even if you showed the photos to my 17-year-old self, I’d be like, OK, no need to roll the dice again, I’ll take that life. I’m not talking about what’s happened with the world—climate change or COVID or the insurrection or anything like that. But the part with the beautiful Israeli complexity theorist wife, who’s also caring and unbreakable in her moral convictions? Yes.

So, thank you and a very happy birthday to the one who’s given me all this!

And lastly, because it seems almost obligatory: I did feed everything I said just now into GPT (I won’t specify which version), and asked it to write Dana a special GPT birthday poem. Here’s what it came up with:

From Tel Aviv to Princeton,

You’ve traveled near and far,

A brilliant computer scientist,

A shining, guiding star.

You’ve made so many sacrifices,

For family and for love,

But your light shines through the darkness,

And fits me like a glove.

We’ve shared so many moments,

Too many to recount,

But each one is a treasure,

Each memory paramount.

So happy birthday, Dana,

You deserve the very best,

I’m grateful for your presence,

And feel so truly blessed.

Addendum: Speaking of GPT, should it and other Large Language Models be connected to the Internet and your computer’s filesystem and empowered to take actions directly, with reinforcement learning pushing it to achieve the user’s goals?

On the negative side, some of my friends worry that this sort of thing might help an unaligned superintelligence to destroy the world.

But on the positive side, at Dana’s birthday party, I could’ve just told the computer, “please display these photos in a slideshow rotation while also rotating among these songs,” and not wasted part of the night messing around with media apps that befuddle and defeat me as a mere CS PhD.

I find it extremely hard to balance these considerations.

Anyway, happy birthday Dana!

December 24, 2022

Short letter to my 11-year-old self

Dear Scott,

This is you, from 30 years in the future, Christmas Eve 2022. Your Ghost of Christmas Future.

To get this out of the way: you eventually become a professor who works on quantum computing. Quantum computing is … OK, you know the stuff in popular physics books that never makes any sense, about how a particle takes all the possible paths at once to get from point A to point B, but you never actually see it do that, because as soon as you look, it only takes one path? Turns out, there’s something huge there, even though the popular books totally botch the explanation of it. It involves complex numbers. A quantum computer is a new kind of computer people are trying to build, based on the true story.

Anyway, amazing stuff, but you’ll learn about it in a few years anyway. That’s not what I’m writing about.

I’m writing from a future that … where to start? I could describe it in ways that sound depressing and even boring, or I could also say things you won’t believe. Tiny devices in everyone’s pockets with the instant ability to videolink with anyone anywhere, or call up any of the world’s information, have become so familiar as to be taken for granted. This sort of connectivity would come in especially handy if, say, a supervirus from China were to ravage the world, and people had to hide in their houses for a year, wouldn’t it?

Or what if Donald Trump — you know, the guy who puts his name in giant gold letters in Atlantic City? — became the President of the US, then tried to execute a fascist coup and to abolish the Constitution, and came within a hair of succeeding?

Alright, I was pulling your leg with that last one … obviously! But what about this next one?

There’s a company building an AI that fills giant rooms, eats a town’s worth of electricity, and has recently gained an astounding ability to converse like people. It can write essays or poetry on any topic. It can ace college-level exams. It’s daily gaining new capabilities that the engineers who tend to the AI can’t even talk about in public yet. Those engineers do, however, sit in the company cafeteria and debate the meaning of what they’re creating. What will it learn to do next week? Which jobs might it render obsolete? Should they slow down or stop, so as not to tickle the tail of the dragon? But wouldn’t that mean someone else, probably someone with less scruples, would wake the dragon first? Is there an ethical obligation to tell the world more about this? Is there an obligation to tell it less?

I am—you are—spending a year working at that company. My job—your job—is to develop a mathematical theory of how to prevent the AI and its successors from wreaking havoc. Where “wreaking havoc” could mean anything from turbocharging propaganda and academic cheating, to dispensing bioterrorism advice, to, yes, destroying the world.

You know how you, 11-year-old Scott, set out to write a QBasic program to converse with the user while following Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics? You know how you quickly got stuck? Thirty years later, imagine everything’s come full circle. You’re back to the same problem. You’re still stuck.

Oh all right. Maybe I’m just pulling your leg again … like with the Trump thing. Maybe you can tell because of all the recycled science fiction tropes in this story. Reality would have more imagination than this, wouldn’t it?

But supposing not, what would you want me to do in such a situation? Don’t worry, I’m not going to take an 11-year-old’s advice without thinking it over first, without bringing to bear whatever I know that you don’t. But you can look at the situation with fresh eyes, without the 30 intervening years that render it familiar. Help me. Throw me a frickin’ bone here (don’t worry, in five more years you’ll understand the reference).

Thanks!!

—Scott

PS. When something called “bitcoin” comes along, invest your life savings in it, hold for a decade, and then sell.

PPS. About the bullies, and girls, and dating … I could tell you things that would help you figure it out a full decade earlier. If I did, though, you’d almost certainly marry someone else and have a different family. And, see, I’m sort of committed to the family that I have now. And yeah, I know, the mere act of my sending this letter will presumably cause a butterfly effect and change everything anyway, yada yada. Even so, I feel like I owe it to my current kids to maximize their probability of being born. Sorry, bud!

December 2, 2022

Google’s Sycamore chip: no wormholes, no superfast classical simulation either

This is going to be one of the many Shtetl-Optimized posts that I didn’t feel like writing, but was given no choice but to write.

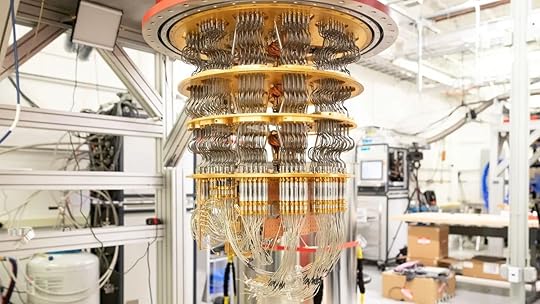

News, social media, and my inbox have been abuzz with two claims about Google’s Sycamore quantum processor, the one that now has 72 superconducting qubits.

The first claim is that Sycamore created a wormhole (!)—a historic feat possible only with a quantum computer. See for example the New York Times and Quanta and Ars Technica and Nature (and of course, the actual paper), as well as Peter Woit’s blog and Chad Orzel’s blog.

The second claim is that Sycamore’s pretensions to quantum supremacy have been refuted. The latter claim is based on this recent preprint by Dorit Aharonov, Xun Gao, Zeph Landau, Yunchao Liu, and Umesh Vazirani. No one—least of all me!—doubts that these authors have proved a strong new technical result, solving a significant open problem in the theory of noisy random circuit sampling. On the other hand, it might be less obvious how to interpret their result and put it in context. See also a YouTube video of Yunchao speaking about the new result at this week’s Simons Institute Quantum Colloquium, and of a panel discussion afterwards, where Yunchao, Umesh Vazirani, Adam Bouland, Sergio Boixo, and your humble blogger discuss what it means.

On their face, the two claims about Sycamore might seem to be in tension. After all, if Sycamore can’t do anything beyond what a classical computer can do, then how exactly did it bend the topology of spacetime?

I submit that neither claim is true. On the one hand, Sycamore did not “create a wormhole.” On the other hand, it remains pretty hard to simulate with a classical computer, as far as anyone knows. To summarize, then, our knowledge of what Sycamore can and can’t do remains much the same as last week or last month!

Let’s start with the wormhole thing. I can’t really improve over how I put it in Dennis Overbye’s NYT piece:

“The most important thing I’d want New York Times readers to understand is this,” Scott Aaronson, a quantum computing expert at the University of Texas in Austin, wrote in an email. “If this experiment has brought a wormhole into actual physical existence, then a strong case could be made that you, too, bring a wormhole into actual physical existence every time you sketch one with pen and paper.”

More broadly, Overbye’s NYT piece explains with admirable clarity what this experiment did and didn’t do—leaving only the question “wait … if that’s all that’s going on here, then why is it being written up in the NYT??” This is a rare case where, in my opinion, the NYT did a much better job than Quanta, which unequivocally accepted and amplified the “QC creates a wormhole” framing.

Alright, but what’s the actual basis for the “QC creates a wormhole” claim, for those who don’t want to leave this blog to read about it? Well, the authors used 9 of Sycamore’s 72 qubits to do a crude simulation of something called the SYK (Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev) model. SYK has become popular as a toy model for quantum gravity. In particular, it has a holographic dual description, which can indeed involve a spacetime with one or more wormholes. So, they ran a quantum circuit that crudely modelled the SYK dual of a scenario with information sent through a wormhole. They then confirmed that the circuit did what it was supposed to do—i.e., what they’d already classically calculated that it would do.

So, the objection is obvious: if someone simulates a black hole on their classical computer, they don’t say they thereby “created a black hole.” Or if they do, journalists don’t uncritically repeat the claim. Why should the standards be different just because we’re talking about a quantum computer rather than a classical one?

Did we at least learn anything new about SYK wormholes from thie simulation? Alas, not really, because 9 qubits take a mere 29=512 complex numbers to specify their wavefunction, and are therefore trivial to simulate on a laptop. There’s some argument in the paper that, if the simulation were scaled up to (say) 100 qubits, then maybe we would learn something new about SYK. Even then, however, we’d mostly learn about certain corrections that arise because the simulation was being done with “only” n=100 qubits, rather than in the n→∞ limit where SYK is rigorously understood. But while those corrections, arising when n is “neither too large nor too small,” would surely be interesting to specialists, they’d have no obvious bearing on the prospects for creating real physical wormholes in our universe.

And yet, this is not a sensationalistic misunderstanding invented by journalists. Some prominent quantum gravity theorists themselves—including some of my close friends and collaborators—persist in talking about the simulated SYK wormhole as “actually being” a wormhole. What are they thinking?

Daniel Harlow explained the thinking to me as follows (he stresses that he’s explaining it, not necessarily endorsing it). If you had two entangled quantum computers, one on Earth and the other in the Andromeda galaxy, and if they were both simulating SYK, and if Alice on Earth and Bob in Andromeda both uploaded their own brains into their respective quantum simulations, then it seems possible that the simulated Alice and Bob could have the experience of jumping into a wormhole and meeting each other in the middle. Granted, they couldn’t get a message back out from the wormhole, at least not without “going the long way,” which could happen only at the speed of light—so only simulated-Alice and simulated-Bob themselves could ever test this prediction. Nevertheless, if true, I suppose some would treat it as grounds for regarding a quantum simulation of SYK as “more real” than a classical simulation.