Andrew Huang's Blog, page 4

September 30, 2024

Winner, Name that Ware August 2024

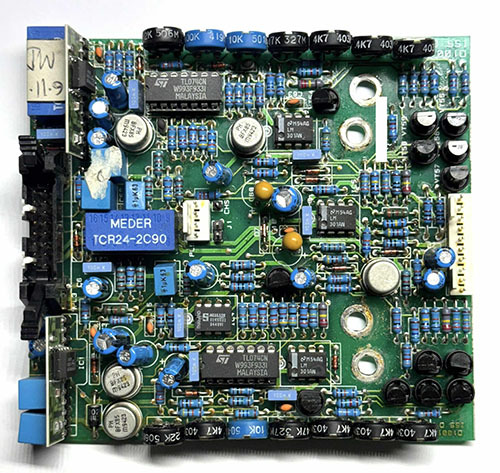

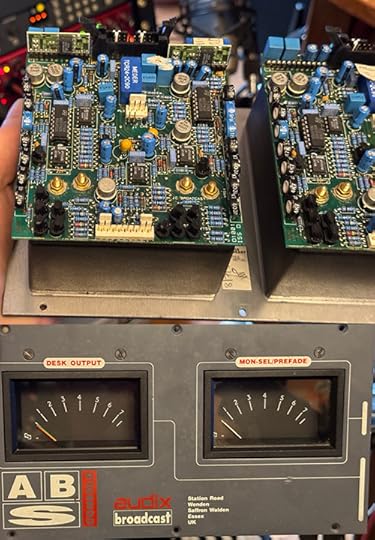

Last month’s Ware was a peak programming meter driver board made by JC Broadcast, taken from an Audix broadcast console. Thanks again to Howie M for contributing the ware!

Howie hypothesized that the four mounting holes would be a dead give-away, in his words:

The meters, typical in the broadcast world, have two needles against a single scale; the 4 holes in this board are both mounting points and contacts for the two coils. The board takes a pair of balanced audio inputs, and drives the pair of needles with tightly controlled (and calibratable) ballistic profiles such that they indicate and hold audio peaks correctly, rather than giving the typical slower VU meter response. The board lets you switch the meters between showing the A and B input levels, or a Sum and Difference reading (which I’m guessing is the purpose of the two Meder relays).

However, it looks like nobody picked up on the mounting holes, and this was a stumper. Personally, I think the closest guess was “two-channel galvo driver” – the panel meters are basically galvanometers, so the physics of the guess was correct, which is good enough for me (and probably about what I would have guessed in the end — something audio-adjacent, obsessively concerned with precision calibrations and/or control loop tuning, but without enough heat sinks to push any significant mass). Congrats, Matt, email me for your prize!

PS: the DIP8’s on the hybrids have a Philips logo, but even with the best shot I have of them on file, I still can’t make out the part number.

September 19, 2024

Turning Everyday Gadgets into Bombs is a Bad Idea

I think turning everyday gadgets into bombs is a bad idea. However, recent news coverage has been framing the weaponization of pagers and radios in the Middle East as something we do not need to concern ourselves with because “we” are safe.

I respectfully disagree. Our militaries wear uniforms, and our weapons of war are clearly marked as such because our societies operate on trust. As long as we don’t see uniformed soldiers marching through our streets, we can assume that the front lines of armed conflict are far from home. When enemies violate that trust, we call it terrorism, because we no longer feel safe around everyday people and objects.

The reason we don’t see exploding battery attacks more often is not because it’s technically hard, it’s because the erosion of public trust in everyday things isn’t worth it. The current discourse around the potential reach of such explosive devices is clouded by the assumption that it’s technically difficult to implement and thus unlikely to find its way to our front door.

That assumption is wrong. It is both surprisingly easy to do, and could be nearly impossible to detect. After I read about the attack, it took half an hour to combine fairly common supply chain knowledge with Wikipedia queries to propose the mechanism detailed below.

Why It’s Not Hard

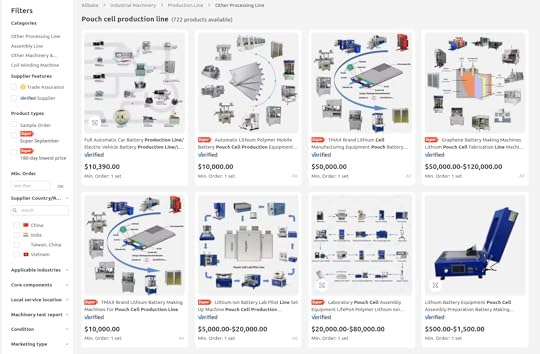

Lithium pouch batteries are ubiquitous. They are produced in enormous volumes by countless factories around the world. Small laboratories in universities regularly build them in efforts to improve their capacity and longevity. One can purchase all the tools to produce batteries in R&D quantities for a surprisingly small amount of capital, on the order of $50,000. This is a good thing: more people researching batteries means more ideas to make our gadgets last longer, while getting us closer to our green energy objectives even faster.

Above is a screenshot I took today of search results on Alibaba for “pouch cell production line”.

The process to build such batteries is well understood and documented. Here is an excerpt from one vendor’s site promising to sell the equipment to build batteries in limited quantities (tens-to-hundreds per batch) for as little as $15,000:

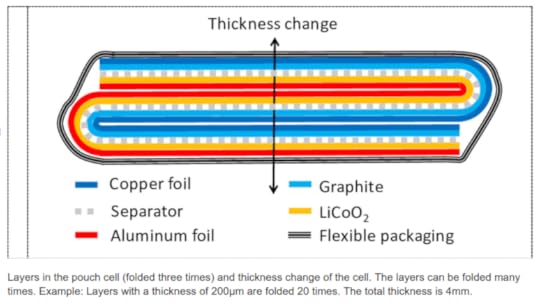

Pouch cells are made by laying cathode and anode foils between a polymer separator that is folded many times:

Above from “High-resolution Interferometric Measurement of Thickness Change on a Lithium-Ion Pouch Battery” by Gunther Bohn, DOI:10.1088/1755-1315/281/1/012030, CC BY 3.0

The stacking process automated, where a machine takes alternating layers of cathode and anode material (shown as bare copper in the demo below) and wraps them in separator material:

There’s numerous videos on Youtube showing how this is done, here’s a couple of videos to get you started if you are curious.

After stacking, the assembly is laminated into an aluminum foil pouch, which is then trimmed and marked into the final lithium pouch format:

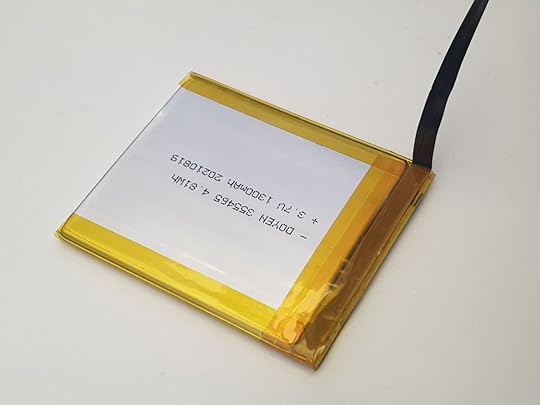

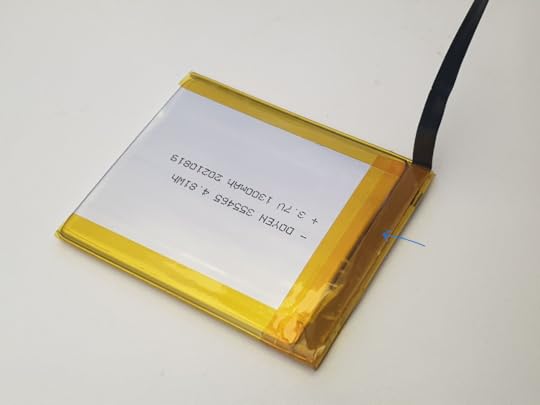

Above is a cell I had custom-fabricated for a product I make, the Precursor. It probably has about 10-15 layers inside, and it costs a few thousand dollars and a few weeks to get a thousand of these made. Point is, making custom pouch batteries isn’t rocket science – there’s a whole bunch of people who know how to do it, and a whole industry behind it.

Reports indicate the explosive payload in the cells is made of PETN. I can’t comment on how credible this is, but let’s assume for now that it’s accurate. I’m not an expert in organic chemistry or explosives, but a read-through the Wikipedia page indicates that it’s a fairly stable molecule, and it can be incorporated with plasticizers to create plastic explosives. Presumably, it can be mixed with binders to create a screen-printed sheet, and passivated if needed to make it electrically insulating. The pattern of the screen printing may be constructed to additionally create a shaped-charge effect, increasing the “bang for the buck” by concentrating the shock wave in an area, effectively turning the case around the device into a small fragmentation grenade.

Such a sheet could be inserted into the battery fold-and-stack process, after the first fold is made (or, with some effort, perhaps PETN could be incorporated into the spacer polymer itself – but let’s assume for now it’s just a drop-in sheet, which is easy to execute and likely effective). This would have the effect of making one of the cathode/anode pairs inactive, reducing the battery capacity, but only by a small amount: only one layer out of at least 10 layers is affected, thus reducing capacity by 10% or less. This may be well within the manufacturing tolerance of an inexpensive battery pack; alternatively, the cell could have an extra layer added to it to compensate for the capacity loss, with a very minor increase in the pack height (0.2mm or so, about the thickness of a sheet of paper – within the “swelling tolerance” of a battery pack).

Why It Could Be Hard to Detect

Once folded into the core of the battery, it is sealed in an aluminum pouch. If the manufacturing process carefully isolates the folding line from the laminating line, and/or rinses the outside of the pouch with acetone to dissolve away any PETN residue prior to marking, no explosive residue can escape the pouch, thus defeating swabs that look for chemical residue. It may also well evade methods such as X-Ray fluorescence (because the elements that compose the battery, separator and PETN are too similar and too light to be detected), and through-case methods like SORS (Spatially Offset Raman Spectroscopy) would likely be defeated by the multi-layer copper laminate structure of the battery itself blocking light from probing the inner layers.

Thus, I would posit that a lithium battery constructed with a PETN layer inside is largely undetectable: no visual inspection can see it, and no surface analytical method can detect it. I don’t know off-hand of a low-cost, high-throughput X-ray method that could detect it. A high-end CT machine could pick out the PETN layer, but it’d cost around a million dollars for one machine and scan times are around a half hour – not practical for i.e. airport security or high throughput customs screening. Electrical tests of capacity and impedance through electromechanical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) may struggle to differentiate a tampered battery from good batteries, especially if the battery was specifically engineered to fool such tests. An ultrasound test might be able to detect an extra layer, but it would require the battery to placed in intimate contact with an ultrasound scanner for screening. I also think that that PETN could be incorporated into the spacer polymer film itself, which would defeat even CT scanners (but may leave a detectable EIS fingerprint). Then again, this is just what I’m coming up with stream-of-consciousness: presumably an adversary with a staff of engineers and months of time could figure out numerous methods more clever than what I came up with shooting from the hip.

Detonating the PETN is a bit more tricky; without a detonator, PETN may conflagrate (burn fast), instead of detonating (and creating the much more damaging shock wave). However, the Wikipedia page notes that an electric spark with an energy in the range of 10-60 mJ is sufficient to initiate detonation.

Based on an available descriptions of the devices “getting hot” prior to detonation, one might suppose that detonation is initiated by a trigger-circuit shorting out the battery pack, causing the internal polymer spacers to melt, and eventually the cathode/anode pairs coming into contact, creating a spark. Such a spark may furthermore be guaranteed across the PETN sheet by introducing a small defect – such as a slight dimple – in the surrounding cathode/anode layers. Once the pack gets to the melting point of the spacers, the dimpled region is likely to connect, leading to a spark that then detonates the PETN layer sandwiched in between the cathode and anode layers.

But where do you hide this trigger-circuit?

It turns out that almost every lithium polymer pack has a small circuit board embedded in it called the PCM or “protection circuit module”. It contains a microcontroller, often in a “TSSOP-8” package, and at least one or more large transistors capable of handling the current capacity of the battery.

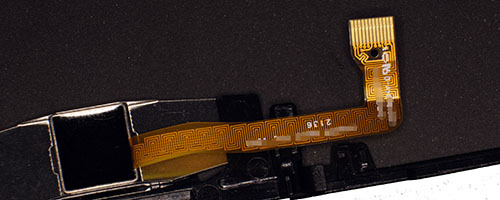

I’ve noted where the protection circuit is on my custom battery pack with a blue arrow. No electronics are visible because the circuit is folded over to protect the electronics from damage.

And above is a selection of three pouch cells that happen to have readily visible protection circuitry. The PCM is the thin green circuit board on the right hand side, covered in protective yellow tape. One take-away from this image is the diversity inherent in PCM modules: in fact, vendors may switch out PCM modules for functionally equivalent ones depending on component availability constraints.

Normally, the protection circuit has a simple job: sample the current flow and voltage of the pack, and if these go outside of a pre-defined range, turn off the flow of current.

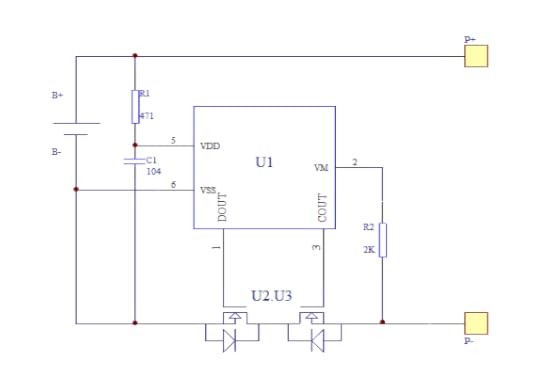

Above: Example of a protection circuit inside a pouch battery. U1 is the controller IC, while U2 and U3 are two separate transistors employed to block current flow in both directions. One of these transistors can be repurposed to short across the battery while still leaving one transistor for protection use (able to block current flow in one direction). Thus the cell is still partially protected despite having a trigger circuit, defeating attempts to detect a modified circuit by simply counting the number of components on the circuit board, or by doing a simple short-circuit or overvoltage test.

A small re-wiring of traces on the protection circuit board gives you a circuit that instead of protecting the battery from out-of range conditions, turns it into a detonator for the PETN layer. One of the transistors that is normally used to cut the flow of electricity is instead wired across the terminals of the battery, allowing for a selective short circuit that can lead to the melting of the spacer layers, ultimately leading to a spark between the dimpled anode/cathode layers and thus detonation of the PETN.

The trigger itself may come via a “third wire” that is typically present on battery packs: the NTC temperature sensor. Many packs contain a safety feature where a nominally 10k resistor is provided to ground that has a so-called “negative temperature coefficient”, i.e., a resistance that changes in a well-characterized fashion with respect to temperature. By measuring the resistance, an external controller can detect if the pack is overheating, and disconnect it to prevent further damage.

However, the NTC can also be used as a one-wire communication bus: the controller IC on the protection circuit can readily sample the voltage on the NTC wire. Normally, the NTC has some constant positive bias applied to it; but if the NTC is connected to ground in a unique pattern, that can serve as a coded trigger to detonate.

The entirety of such a circuit could conceivably be implemented using an off-the-shelf microcontroller, such as the Microchip/Atmel Attiny 85/V, a TSSOP-8 device that would look perfectly at-home on a battery protection PCB, yet contains an on-board oscillator and sufficient code space such that it could decode a trigger pattern.

If the battery charger is integrated into the main MCU – which it often is in highly cost-reduced products such as pagers and walkie-talkies – the trigger sequence can be delivered to the battery with no detectable modification to the target device. Every circuit trace and component would be where it’s supposed to be, and the MCU would be an authentic, stock MCU.

The only difference is in the code: in addition to mapping a GPIO to an analog input to sample the NTC, the firmware would be modified to convert the GPIO into an output at “trigger time” which would pull the NTC to ground in the correct sequence to trigger the battery to explode. Note that this kind of flexibility of pin function is quite typical for modern microcontrollers.

Technical Summary

Thus, one could conceivably create a supply chain attack to put exploding batteries into everyday devices that is undetectable: the main control board is entirely unmodified; only a firmware change is needed to incorporate the trigger. It would pass every visual and electrical inspection.

The only component that has to be swapped out is the lithium pouch battery, which itself can be constructed for an investment as small as $15,000 in equipment (of course you’d need a specialist to operate the equipment, but pouch cells are ubiquitous enough that it would not be surprising to find a line at any university doing green-energy research). The lithium pouch cell itself can be constructed with an explosive layer that I hypothesize would be undetectable to most common analytical methods, and the detonator trigger can be constructed so that it is visually and mostly electrically indistinguishable from the protection circuit module that would be included on a stock lithium pouch battery, using only common, off-the-shelf components. Of course, if the adversary has the budget to make a custom chip, they could make the entire protection circuit perfectly indistinguishable to most forms of non-destructive inspection.

How To Attack a Supply Chain

Insofar as how one can get such cells and firmware updates into the supply chain – see any of my prior talks about the vulnerability of hardware supply chains to attack. For example: this talk which I gave in Israel in 2019 at the BlueHat event, outlining the numerous attack surfaces and porosity of modern hardware supply chains.

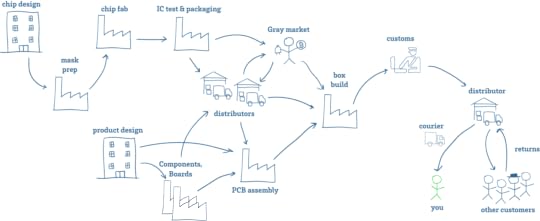

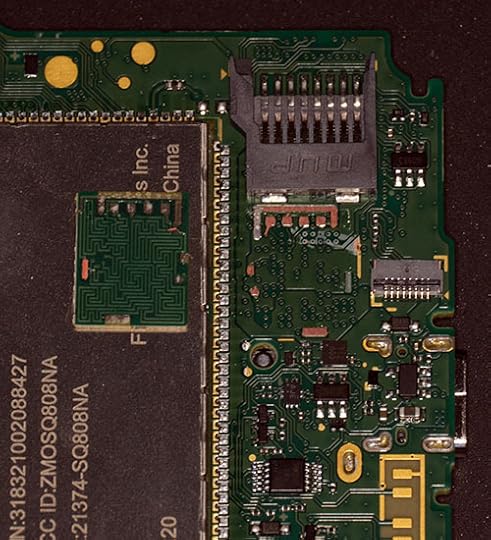

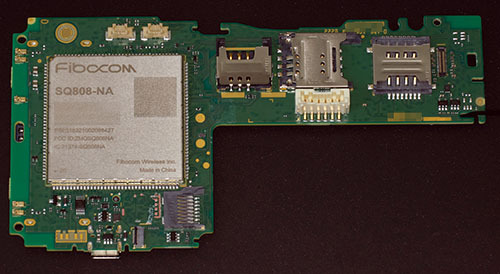

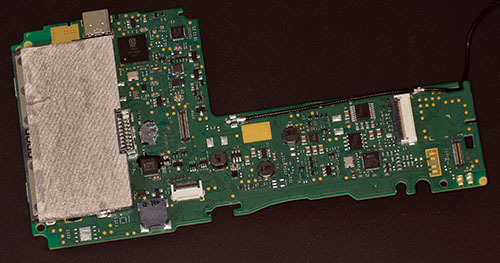

Above is a cartoon sketch of a supply chain. Getting fake components into the supply chain is easier than you might think. As a manufacturer of hardware, I have to deal with fake components all the time. This is especially true for batteries – most popular consumer electronic devices already have a healthy gray market for replacement batteries. These are batteries that look the same as OEM batteries and fetch an OEM price, but are made with sub-par components.

Aside from taking advantage of gray and secondary markets, there are multiple opportunities along the route from the factory to you to tamper with goods – from the customs inspector, to the courier.

But you don’t even have to go so far as offering anyone a bribe or being a state-level agency to get tampered batteries into a supply chain. Anyone can buy a bunch of items from Amazon, swap out the batteries, restore the packaging and seals, and return the goods to the warehouse (and yes, there is already a whole industry devoted to copying packaging and security seals for the purpose of warranty fraud). The perpetrator will be long-gone by the time the device is resold. Depending on the objective of the campaign, no further targeting may be necessary – just reports of dozens of devices simultaneously detonating in your home town may be sufficient to achieve a nefarious objective.

Note that such a “reverse-logistics injection attack” works even if you on-shore all your factories, and tariff the hell out of everyone else. Any “tourist” with a suitcase is all it takes.

Pandora’s Box is Open

Not all things that could exist should exist, and some ideas are better left unimplemented. Technology alone has no ethics: the difference between a patch and an exploit is the method in which a technology is disclosed. Exploding batteries have probably been conceived of and tested by spy agencies around the world, but never deployed en masse because while it may achieve a tactical win, it is too easy for weaker adversaries to copy the idea and justify its re-deployment in an asymmetric and devastating retaliation.

However, now that I’ve seen it executed, I am left with the terrifying realization that not only is it feasible, it’s relatively easy for any modestly-funded entity to implement. Not just our allies can do this – a wide cast of adversaries have this capability in their reach, from nation-states to cartels and gangs, to shady copycat battery factories just looking for a big payday (if chemical suppliers can moonlight in illicit drugs, what stops battery factories from dealing in bespoke munitions?). Bottom line is: we should approach the public policy debate around this assuming that someday, we could be victims of exploding batteries, too. Turning everyday objects into fragmentation grenades should be a crime, as it blurs the line between civilian and military technologies.

I fear that if we do not universally and swiftly condemn the practice of turning everyday gadgets into bombs, we risk legitimizing a military technology that can literally bring the front line of every conflict into your pocket, purse or home.

August 15, 2024

Name that Ware, August 2024

Winner, Name that Ware July 2024

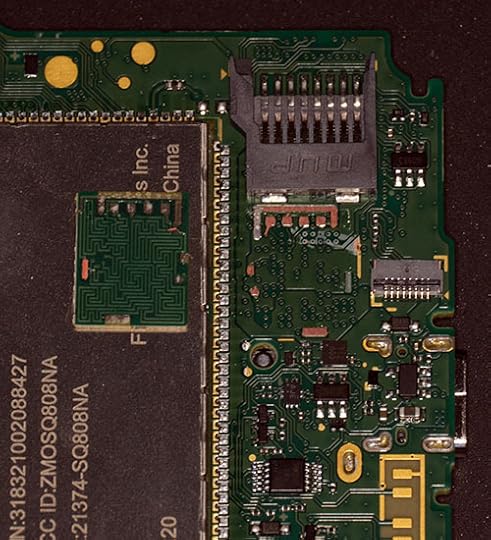

The ware for July 2024 is an Ingenico Axium DX8000. I hadn’t had a chance to tear down a modern POS terminal myself, so it was pretty interesting to see all the anti-tamper traces built into the product (thank you jackw01 for sharing it!). I wonder how effective these are, and how they mitigate manufacturing variations to prevent false positives. It looks like they use some custom IC to drive the serpentine traces, so presumably the chips are smart enough to do a training phase that calibrates to the environment and they just look for a “delta” on key metrics to flag a problem. Every computer already has self-training drivers that respond to manufacturing variations (in the DDR busses and high speed comms cables such as HDMI, USB-C, Ethernet, etc.), so I imagine this is fairly solid technology.

Still can’t help but wonder if the terminals can be remote-DoS’d with a relatively simple device that radiates signals at the right frequency to activate the tamper triggers. Thankfully, I haven’t heard of such an exploit, yet.

Jacob Creedon had a strong first guess but Anon got the make and model almost exactly right, so I’ll give the prize to Anon. Congrats, email me for your prize!

July 31, 2024

Name that Ware, July 2024

The Ware for July 2024 is shown below.

Thanks again to jackw01 for contributing this ware! The last two images might be killer clues that give away the ware, but they are also so cool I couldn’t not include them as part of the post.

Winner, Name that Ware June 2024

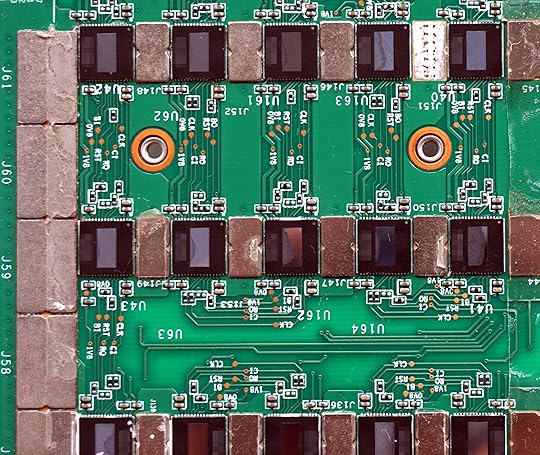

The Ware for June 2024 is a hash board from an Antminer S19 generation bitcoin miner, with the top side heatsinks removed. I’ll give the prize to Alex, for the thoughtful details related in the comments. Congrats, email me for your prize!

I chose this portion of the miner to share for the ware because it clearly shows the “string of pearls” topology of the miner. Each chip’s ground is the VDD of the chip to the left. So, the large silvery bus on the left is ground, then the next rank is VDD, the next is VDD*2, VDD*3, and so forth, until you reach about 12 volts. The actual value of VDD itself is low – around 0.3V, if I recall correctly. Miners focus on efficiency, not performance, so the mining chips are operated at a lower core voltage to improve computational efficiency per joule of energy consumed, at the expense of having to throw more chips at the problem for the same computational throughput.

Along the bottom side of the image, you can see that the signals between chips cross the voltage domains without a level shifter. This is one of the things that I thought was kind of crazy, because there is a risk of latch-up whenever you feed voltages in that are above or below the power supply rails. However, because the core VDD is so low (0.3V), the ground difference between adjacent chips is small enough that the parasitic diode necessary to initiate the latch-up cascade isn’t triggered.

The whole arrangement relies on each chip maintaining its core voltage to under the latch-up threshold. But what controls that voltage? The answer is that it’s pretty much unregulated – if you were to say, run hashing on one chip but leave another chip idle, the core voltages will diverge rapidly, because the idle chip will have a higher impedance than the active chip but being wired in series, all the current of the active chip must flow through the idle chip, and thus the idle chip’s voltage rises until its idle leakage becomes big enough to feed the active chips in the chain.

Of course, the intention is that all the chips are simultaneously ramped up in terms of computational rate, so the energy consumption is equally distributed across the string and you don’t get any massive voltage shifts between ranks.

You’ll note the supplemental metal sheets soldered onto the power busses on the board. I had removed one of the sheets in the top right of the image. These bus bars are added to the board to reduce the V-I drop of the power distribution. Each string pushes 10’s of amps of current, so reducing the resistive losses of the copper traces by adding these bus bars in between chips measurably improves the efficiency of the hasher. If you look at a more zoomed-out version of the image, the distance between the chips actually increases as you go across the board. I’m not sure exactly why this is the case but I think it’s because one side is farther from the fans, and so they adjust the density of the chips to even out the air temperature as it makes its way across the board.

Anyways, at this massive current draw, any chip failure gets…”exciting”, to use a term of art. It turns out that a miner can operate with one busted chip in the chain. Since leakage goes up super-linearly with temperature and voltage, they basically rely on physics to turn the broken chip into a pass-through heating element. The voltage shift between ranks does go up slightly in that case, but apparently still by not enough to trigger latch-up.

That being said, latch-up is a big concern. Power cycling one of these beasts takes minutes — there is an interlock in the system that will wait a very long time with the power off to ensure that every capacitor in the chain has fully discharged. In order to prevent latch-up on a power-cycle, I imagine that every capacitor’s voltage has to be discharged to something quite a bit less than 0.3V. If you’ve ever poked around an “idle” board (powered off, but possibly with some live peripheral connector plugged in), you’ll know that even the tiniest leakages can easily develop 0.1V across a node, and 0.3V+ levels can persist for a very long time without explicit discharge clamps (I’ve seen some laptops designed with discrete FETs to discharge voltage rails internally so one can do a quick suspend/resume cycle without triggering latch-up). Since the design has no clamps to discharge the internal nodes (that I can see) I presume it just relies on the minutes of idle time on the reboot to ensure that the inherent leakage paths (which become exponentially less leaky as the voltages go down) discharge the massive amount of capacitance in the string of chips.

Of course, all these shenanigans are done in the name of efficiency and low cost. Providing a buck regulator per chip would be cost-prohibitive and less efficient; you can’t beat the string-of-pearls topology for efficiency (this is what all home LED lighting uses for a reason).

But, as a “regular” digital engineer who strives for everything to go to ground, and if ground isn’t ground you fix it so that the ground plane doesn’t move, it’s kind of mind blowing that you can get such a complicated circuit to work with no fixed ground between chips. The ground of each chip floats and finds its truth through the laws of physics and the vagaries of yield and computation-dependent energy usage patterns. It’s a really brilliant example that reinforces the notion that even though one may abstract ground to be a “global 0 voltage”, in reality, ground is always local and voltages only exist in relation to a locally measurable reference point – ground bounce is “just fine” so long as your entire ground bounces. If you told me the idea of stringing chips together VDD-to-GND without showing me an implementation, I would have vehemently asserted it’s not possible, and you’d have all sorts of field failures and yield problems. Yet, here we are: I am confronted with proof that my intuition is incorrect. Not only is it possible, you can do it at kilowatt-scales with hundreds of chips, tera-hashes of throughput, with countless deployments around the world. Hats off to the engineers who pulled this together! I have to imagine that on the way to getting this right, there had to be some lab somewhere that got filled with quite the puff of blue smoke, and the acrid smell that heralds new things to learn.

June 30, 2024

Name that Ware, June 2024

The Ware for June 2024 is shown below.

This one will probably be a super-easy guess for some folks, but the details of the design of this type of ware are interesting from an engineering standpoint. Some of the tricks used here are kind of mind blowing; on paper, I wouldn’t think it would work, yet clearly it does. I’ll go into it a bit more next month, when we name the winner. Or, if you’re already an expert in this type of ware and have circuit-level insights to share, be my guest!

Winner, Name that Ware May 2024

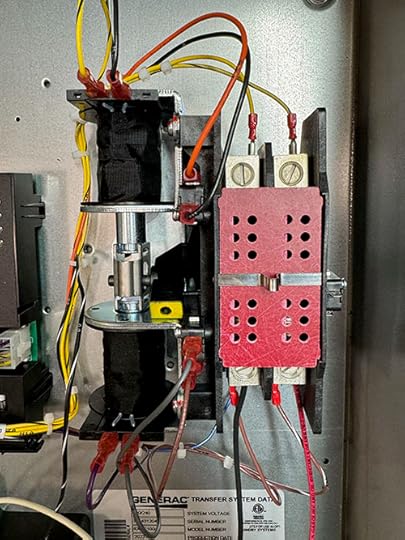

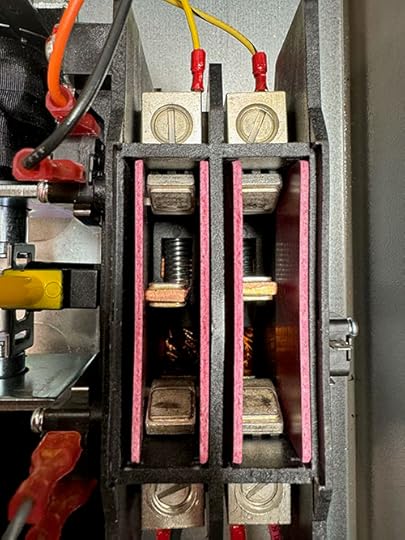

The Ware from May 2024 is a Generac RXSC100A3 100-amp automated load transfer switch. It senses when utility power fails and automatically throws a switch to backup power. Thanks to Curtis Galloway for contributing this ware; he has posted a nice write-up about his project using it. The total function of the ware was a bit difficult to guess because the actual load switch wasn’t shown – the relays don’t do the power switching; they merely control a much larger switch.

A lot of questions in the comments about why a 50/60Hz jumper. I think it’s because as a backup power switch, a deviation of the mains frequency by 10Hz is considered a failure, and thus, backup power should be engaged. I also think the unit does zero-crossing detection to minimize arcing during the switch-over. The system drives a pair of rather beefy solenoids, which can be seen to the left of the load switch in the image below.

And this is the inside of the 100-amp load switch itself:

For better images hit up Curtis’ blog!

I think Ben got pretty close in his analysis of the ware, noting the 50/60Hz jumper could be for mains failure detection. Congrats, email me for your prize!

An administrative note: my ISP upgraded the blog’s database server this past month. Because this blog was created before UTF-8 was widely adopted, the character sets got munged, which required me to muck around with raw SQL queries to fix things up. I think almost everything made it through, but if anyone notices some older posts that are messed up or missing, drop a comment here.

I’m also working on trying to configure a fail-over for my image content server (bunniefoo.com), which is still running on a very power-efficient Novena board of my own design from over a decade ago. It’s survived numerous HN hugs of death, but the capacitor electrodes are starting to literally oxidize away from a decade of operating in salty, humid tropical air. So, I think it might be time to prep a fail-safe backup server — a bit like the load switch above, but for bits not amps. However, I think I’m more in my element configuring a 100A load switch than an IP load balancer. The Internet has only gotten more hostile over the past decades, so I’m going to have some learning experiences in the next couple of months. If you see something drop out for more than a day or so, give me a shout!

June 2, 2024

Formlabs Form 4 Teardown

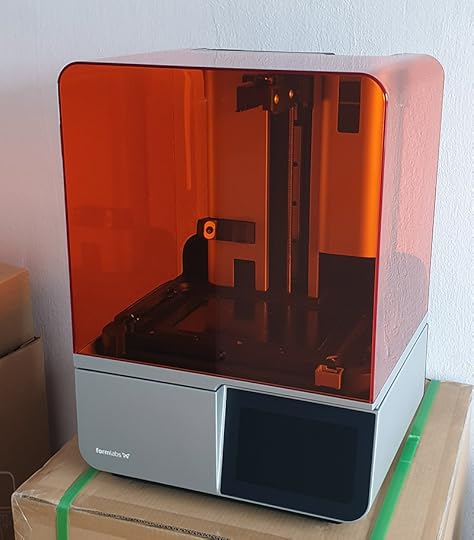

Formlabs has recently launched the fourth edition of their flagship SLA printer line, the Form 4. Of course, I jumped on the chance to do a teardown of the printer; I’m grateful that I was able to do the same for the Form 1, Form 2, and Form 3 generations. In addition to learning a lot from the process of tearing down a single printer, I am also gaining a unique perspective on how a successful hardware startup matures into an established player in a cut-throat industry.

Financial interest disclosure: Formlabs provides me two printers for the teardown, with no contingencies on the contents or views expressed in this post. I am also a shareholder of Formlabs.

A Bit of Background

The past few years has seen a step-function in the competitiveness of products out of China, and SLA 3D printers have been no exception. The Form 4 sits at a pivotal moment for Formlabs, and has parallels to the larger geopolitical race for technological superiority. In general, Chinese products tend to start from a low price point with fewer features and less reliability, focusing on the value segment and iterating their way towards up-market opportunities; US products tend to start at a high price point, with an eye on building (or defending) a differentiated brand through quality, support, and features, and iterate their way down into value-oriented models. We now sit at a point where both the iterate-up and iterate-down approaches are directly competing for the same markets, setting the stage for the current trade war.

Being the first to gain momentum in a field also results in the dilemma of inertia. Deep financial and human capital investments into older technology often create a barrier to adopting newer technology. Mobile phone infrastructure is a poster child for the inertia of legacy: developing countries often have spectacular 5G service compared to the US, since they have no legacy infrastructure on the balance sheet to depreciate and can thus leapfrog their nations directly into mature, cost-reduced and modern mobile phone infrastructure.

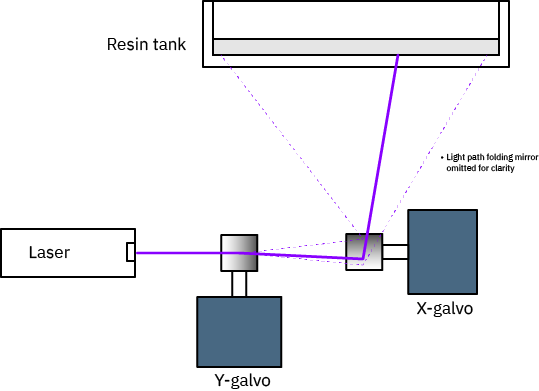

In the case of 3D printers, Formlabs was founded in 2011, back when UV lasers were expensive, UV LEDs weren’t commercially viable, and full HD LCD screens (1080p) were just becoming mainstream. The most viable technology for directing light at the time was the galvanometer: a tiny mirror mounted on a motor that can adjust its angle with parts-per-thousands accuracy, tens of thousands of times a second. They invested in full custom galvanometer technology to create a consumer-priced SLA 3D printer – a technology that remained a gold standard for almost a decade, and powered three generations of Form printers.

Above is the light path architecture of the Form 1 and Form 2 printers. Both used a laser plus a pair of galvanometers to direct light in a 2-D plane to cure a single layer of resin through raster scanning.

The Form 3, introduced in 2019, pushed galvanometer technology to its limit. This used a laser and a single galvanometer to scan one axis, bounced off a curved mirror and into the resin tank, all in a self-contained module called a “light processing unit” (LPU). The second axis came from sliding the LPU along the rail, creating the possibility of parallel LPUs for higher throughput, and “unlimited” printing volume in the Y direction.

In the decade since Formlabs’ founding, LCD and LED technology have progressed to the point where full-frame LCD printing has become viable, with the first devices available in the range of 2015-2017. I got to play with my first LCD printer in 2019, around the time that the Form 3 was launched. The benefits of an LCD architecture were readily apparent, the biggest being build speed: an LCD printer can expose the entire build area in a single exposure, instead of having to trace a slice of the model with a single point-like laser beam. However, LCD technology still had a learning curve to climb, but manufacturers climbed it quickly, iterating rapidly and introducing new models much faster than I could keep up with.

Five years later and one pandemic in between, the Form 4 is being launched, with the light processing engine fully transitioned from galvanometer-and-laser to an LCD-and-LED platform. I’m not privy to the inside conversations at Formlabs about the change, but I imagine it wasn’t easy, because transitioning away from a decade of human capital investment into a technology platform can be a difficult HR challenge. The LPU was a truly innovative piece of technology, but apparently it couldn’t match the speed and cost of parallel light processing with an LCD. However, I do imagine that the LPU is still indispensable for high-intensity 3D printing technologies such as Selective Laser Sintering (SLS).

Above is the architecture of the Form 4 – “look, ma, no moving parts!” – an entirely solid state design, capable of processing an entire layer of resin in a single go.

I’m definitely no expert in 3D printing technology – my primary exposure is through doing these teardowns – but from a first-principles perspective I can see many facial challenges around using LCDs as a light modulator for UV, such as reliability, uniformity, and build volume.

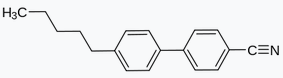

As their name implies, LCDs (liquid crystal displays) are built around cells filled with liquid crystal. Liquid crystals are organic molecules; 5CB is a textbook example of an LC compound.

Above is the structure of 5CB, snagged from its Wikipedia page; a few other LC molecules I looked up share a similar structure. I’m no organic chemist, but if you asked me “do you think a molecule like this might interact with intense ultraviolet light”, my answer is “definitely yes” – look at those aromatic rings!

A quick search seems to indicate that LCDs as printer elements can have a lifetime as short as a few hundred hours – which, given that the UV light is only on for a fraction of the time during a print cycle, probably translates to a few hundred prints. So, I imagine some conversations were had at Formlabs on how to either mitigate the lifetime issues or to make the machine serviceable so the LCD element can be swapped out.

Another challenge is the uniformity of the underlying LEDs. This challenge comes in two flavors. The first problem is that the LEDs themselves don’t project a uniform light cone – LEDs tend to have structural hot spots and artifacts from things such as bond wires that can create shadows; but diffusers and lenses incur optical losses which reduce the effective intensity of the light. The second is that the LEDs themselves have variance between devices and over time as they age, particularly high power devices that operate at elevated temperatures. This can be mitigated in part with smart digital controls, feedback loops, and cooling. This is helped by the fact that the light source is not on 100% of the time – in tests of the Form 4 it seems to be much less than 25% duty cycle, which gives ample time for heat dissipation.

Build volume is possibly a toss-up between galvo and LCD technologies. LCD resolutions can be made cheaply at extremely high resolutions today, so scaling up doesn’t necessarily mean coarser prints. However, you have to light up an even bigger area, and if your average build only uses a small fraction of the available volume, you’re wasting a lot of energy. On the other hand, with the Form 3’s LPU, energy efficiency scales with the volume of the part being printed: you only illuminate what you need to cure. And, the Form 3 can theoretically print an extremely wide build volume because the size in one dimension is limited only by the length of the rail for the LPU to sweep. One could conceivably 3D print the hood of a car with an LPU and a sufficiently wide resin tank! However, in practice, most 3D prints focus on smaller volumes – perhaps due to the circular reasoning of people simply don’t make 3D models for build volumes that aren’t available in volume production.

Despite the above challenges, Formlabs’ transition to LCD technology comes with the reward of greatly improved printing times. Prints that would have run overnight on the Form 3 now finish in just over an hour on the Form 4. Again, I’m not an expert in 3D printers so I don’t know how that speed compares against the state of the art today. Searching around a bit, there are some speed-focused printers that advertise some incredible peak build rates – but an hour and change to run the below test print is in net faster than my workflow can keep up with. At this speed, the sum of time I spend on 3D model prep plus print clean and finishing is more than the time it takes to run the print, so for a shop like mine where I’m both the engineer and the operator, it’s faster than I can keep up with.

A Look around the Exterior of the Form 4

Alright, let’s have a look at the printer!

The printer comes in a thoughtfully designed box, with ample padding and an opaque dust cover.

I personally really appreciate the detail of the dust cover – as I only have the bandwidth to design a couple products a year, the device can go for months without use. This is much easier on the eyes and likely more effective at blocking stray light than the black plastic trash bags I use to cover my printers.

The Form 4 builds on the design language of previous generation Form printers, with generous use of stamped aluminum, clean curves, and the iconic UV-blocking orange acrylic tank. I remember the first time I saw the orange tank and thought to myself, “that has to be really hard to manufacture…” I guess that process is now fully mature, as even the cheapest SLA printers incorporate that design touchstone.

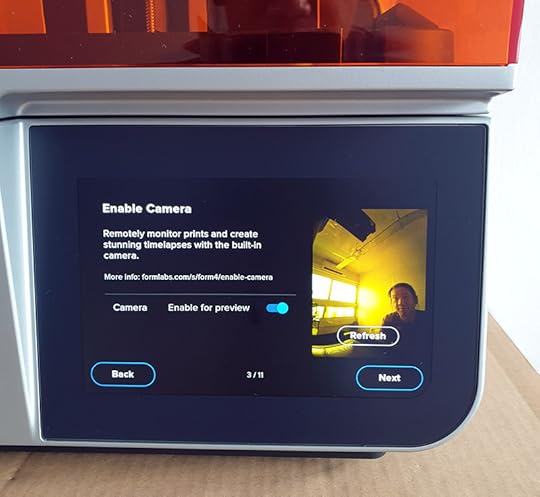

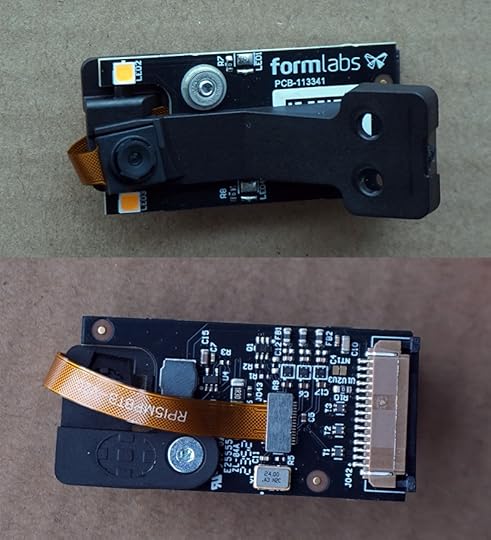

A new feature that immediately leaps out to me is the camera. Apparently, this is for taking time lapses of builds. It increases the time to print (because the workpiece has to be brought up to a level for the camera to shoot, instead of just barely off the surface of the tank), but I suppose it could be useful for diagnostics or just appreciating the wonder of 3D printing. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to get the feature to work with the beta software I had – it took the photos, but there’s something wrong with my Formlabs dashboard such that my Form 4 doesn’t show up there, and I can’t retrieve the time-lapse images.

Personally, I don’t allow any unattended, internet-connected cameras in my household – unused cameras are covered with tape, lids, or physically disabled if the former are not viable. I had to disclose the presence of the camera to my partner, which made her understandably uncomfortable. As a compromise, I re-positioned the printer so that it faces a wall, although I do have to wonder how many photos of me exist in my boxer shorts, checking in on a print late at night. At least the Form 4 is very up-front about the presence of the camera; one of the first things it does out of the box is ask you if you want to enable the camera, along with a preview of what’s in its field of view. It has an extremely wide angle lens, allowing it to capture most of the build volume in a single shot; but it also means it captures a surprisingly large portion of the room behind it as well.

Kind of a neat feature, but I think I’ll operate the Form 4 with tape over the camera unless I need to use the time-lapse feature for diagnostics. I don’t trust ‘soft switches’ for anything as potentially intrusive as a camera in my private spaces.

The backside of the Form 4 maintains a clean design, with another 3D printed access panel.

Above is a detail of the service plug on the back panel – you can see the tell-tale nubs on the inner surface of 3D printing. Formlabs is walking the walk by using their own printers to fabricate parts for their shipping products.

The bottom of the printer reveals a fan and a massive heatsink underneath. This assembly keeps the light source cool during operation. The construction of the bottom side is notably lighter-duty than the Form 3. I’m guessing the all solid-state design of the Form 4 resulted in a physically lighter device with reduced mechanical stiffness requirements.

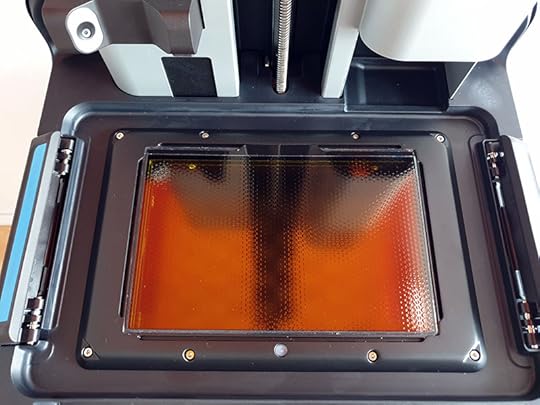

Inside the printer’s cover, we get our first look at the pointy end of the stick – the imager surface. Unlike its predecessors, we’re no longer staring into a cavity filled with intricate mechanical parts. Instead we’re greeted with a textured LCD panel, along with some intriguing sensors and mounting features surrounding it. A side effect of no longer having to support an open-frame design is that the optical cavity within the printer is semi-sealed, with a HEPA-filtered centrifugal fan applying positive pressure to the cavity while cooling the optics. This should improve reliability in dusty environments, or urban centers where fine soot from internal combustion engines somehow finds their way onto every optical surface.

One minor detail I personally appreciate is the set of allen keys that come with the printer, hidden inside a nifty 3D printed holder. I’m a fan of products that ship with screwdrivers (or screwdriver-oids); it’s one of the feature points of the Precursor hardware password manager that I currently market.

The Allen key holder is just one of many details that make the Form 4 far easier to repair than the Form 3. I recall the Form 3 being quite difficult to take apart; while it used gorgeous body panels with compound splines, the situation rapidly deteriorated from “just poking around” to “this thing is never going back together again”. The Form 4’s body panels are quite easy to remove, and more importantly, to re-install.

A Deep Dive into the Light Path

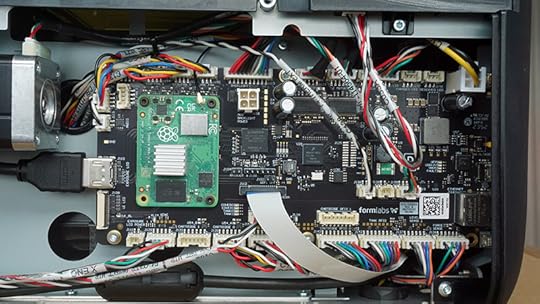

Pulling off the right body panel reveals the motherboard. Four screws and the panel is off – super nice experience for repair!

And below, a close-up of the main board (click for a larger version):

A few things come out at me on first glance.

First up, the Raspberry Pi 4 compute module. From a scrappy little “$35 computer” put out by a charity originally for the educational market, Raspberry Pi has taken over the world of single board computers, socket by socket. Thanks to the financial backing it had from government grants and donations as well as tax-free status as a charity, it was able to kickstart an unusually low-margin hardware business model into a profitable and sustainable (and soon to be publicly traded!) organization with economies of scale filling its sails. It also benefits from awesome software support due to the synergy of its charitable activities fostering a cozy relationship with the open source community. Being able to purchase modules like the Raspberry Pi CM with all the hard bits like high-speed DDR memory routing, emissions certification, and a Linux distro frees staff resources in other hardware companies (like Formlabs and my own) to focus on other aspects of products.

The next thing that attracted my attention is the full-on HDMI cable protruding from the mainboard. My first thought was to try and plug a regular monitor into that port and see what happens – turns out that works pretty much exactly as you’d expect:

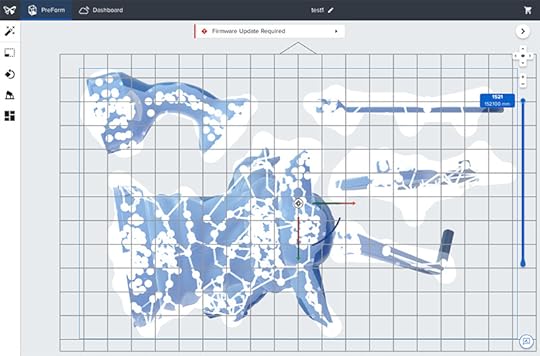

In the image above, the white splotches correspond to the areas being cured for the print – in this case, the base material for the supports for several parts in progress.

Above is a view of the layer being printed, as seen in the Preform software.

And above is a screenshot showing some context of the print itself.

The main trick is to boot the Form 4 with the original LCD plugged in (it needs to read the correct EDID from the panel to ensure it’s there, otherwise you get an error message), and then swap out the cable to an external monitor. I didn’t let the build run for too long for fear of damaging the printer, but for the couple layers I looked at there were some interesting flashes and blips. They might hint at some image processing tricks being played, but for the most part what’s being sent to the LCD is the slice of the current model to be cured.

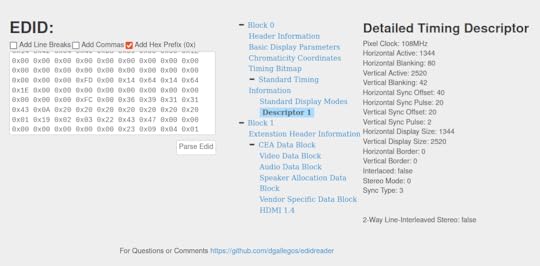

I also took the LCD panel out of the printer and plugged it into my laptop and dumped its EDID. Here are the parameters that it reports:

I was a little surprised that it’s not a 4K display, but actually, we have to remember that each “color pixel” is actually three monochrome elements – so it probably has 2520 elements vertically, and 4032 elements horizontally. While resolutions can go higher than that, there are likely trade-offs on fill-factor (portion of a pixel that is available for light transmission versus reserved for switching circuitry) that are negatively impacted by trying to push resolution unnecessarily high.

The LCD panel itself is about as easy to repair as the side body panels; just 8 accessible screws, and it’s off.

Another minor detail I really enjoyed on the LCD panel is the 3D-printed retaining clip for the HDMI cable. I think this was probably made out of nylon on one of Formlabs’ own SLS printers.

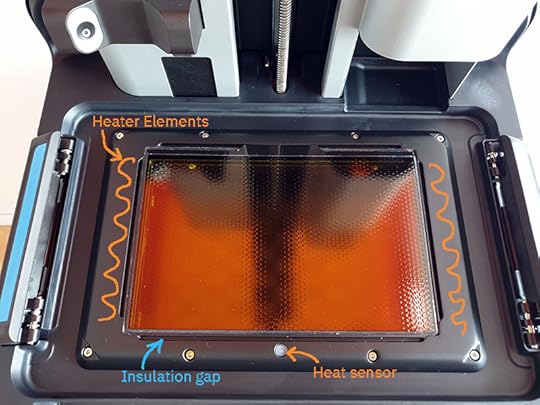

Turn the LCD panel assembly over, and we see a few interesting details. First, the entire assembly is built into a robust aluminum frame. The frame itself has a couple of heating elements bonded to it, in the form of PCBs with serpentine traces. This creates an interesting conflict in engineering requirements:

The resin in the tank needs to be brought to temperature for printingThe LCD needs to be kept cool for reliabilityBoth need to be in intimate contact with the resinFormlabs’ solution relies on the intimate contact with the resin to preferentially pull heat out of the heating elements, while avoiding overheating of the LCD panel, as shown below.

The key bit that’s not obvious from the photo above is that the resin tank’s lower surface is a conformal film that presses down onto the imaging assembly’s surface, allowing heat to go from the heater elements almost directly into the resin. During the resin heating phase of the print, a mixer turns the resin over continuously, ensuring that conduction is the dominant mode of heat transfer into the resin (as opposed to a still resin pool relying on natural convection and diffusion). The resin is effectively a liquid heat sink for the heater elements.

Of course, aluminum is an excellent conductor of heat, so to prevent heat from preferentially flowing into the LCD, gaps are milled into the aluminum panel that go along the edges of the panel, save the corners which still touch for good alignment. Although the gaps are filled with epoxy, the thermal conduction from the heating elements into the LCD panel is presumably much lower than that into the resin tank itself, thus allowing heating elements situated mere millimeters away from an LCD panel to heat the resin, without overheating the LCD.

One interesting and slightly puzzling aspect of the LCD is the textured film applied to the top of the LCD assembly. According to the Formlabs website, this is a “release texture” which prevents a vacuum between the film and the LCD panel, thus reducing peel forces and improving print times. The physics of print release from the tank film is not at all obvious to me, but perhaps during release phase, the angle between the film and the print in progress plays a big role in how fast the film can be peeled off. LCDs are extremely flat and I can see that without such a texture, air bubbles could be trapped between the film and the LCD; or if no air bubbles were there, there could be a significant amount of electrostatic attraction between the LCD and the film that can lead to inconsistent release patterns.

That being said, the texture itself creates a bunch of small lenses that should impact print quality. Presumably, this is compensated in the image processing pipeline by pre-distorting the image such that the final projected image is perfect. I tried to look for signs of such compensation in the print layers when I hooked the internal HDMI cable to an external monitor, but didn’t see it – but also, I was looking at layers that already had some crazy geometry to it, so it’s hard to say for sure.

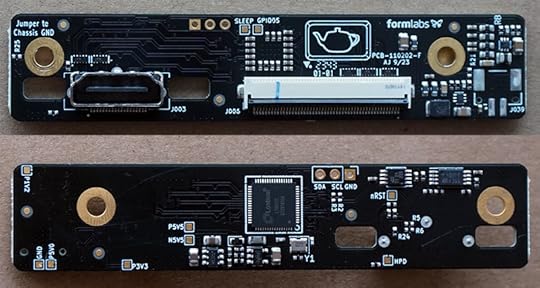

The LCD driver board itself is about what you’d expect: an HDMI to flat panel converter chip, plus an EDID ROM.

As a side note, an LCD panel – a thing we think of typically as the finished product that we might buy from LG, Innolux, Sharp, CPT, etc. – is an assembly built from a liquid crystal cell (LC cell) and a backlight, along with various films and a handful of driver electronics. A lot of the smaller players who sell LCD panels are integrators who buy LC cells, backlights, and electronics from other specialty vendors. The cell itself consists of the glass sheets with the transparent ITO wires and TFT transistors, filled with LC material. This is the “hard part” to make, and only a few large factories have the scale to produce them at a competitive cost. The orange thing we’re looking at in the Form 4 is more precisely described as an LC cell plus some polarizing films and a specialized texture on top. Building a custom LC cell isn’t profitable unless you have millions of units per year volume, so Formlabs had to source the LC cells from a vendor specialized in this sort of thing.

Hold the panel up to a neutral light source (e.g., the sun), and we can see some interesting behaviors.

The video above was taken by plugging the Form 4’s LCD into my laptop and typing “THIS IS A TEST” into a word processor (so it appears as black text on a white background on my laptop screen). The text itself looks wider than on my computer screen because the Formlabs panel is probably using square pixels for each of the R, G, and B channels. For their application, there is no need for color filters; it’s just monochrome, on or off.

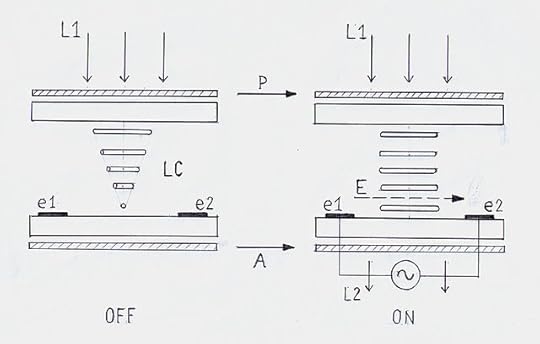

I suspect the polarizing films are UV-optimized. I’m not an expert in optics, but from the little I’ve played with it, polarizing films have a limited bandwidth – I encountered this while trying to polarize IR light for IRIS. I found that common, off-the-shelf polarizing films seemed ineffective at polarizing IR light. I also suspect that the liquid crystal material within the panel itself is tailored for UV light – the contrast ratio is surprisingly low in visible light, but perhaps it’s much better in UV.

I’m also a bit puzzled as to why rotating the polarizer doesn’t cause light to be entirely blocked in one of the directions; instead, the contrast inverts, and at 45 degrees there’s no contrast. When I try this in front of a conventional IPS LCD panel, one direction is totally dark, the other is normal. After puzzling over it a bit, the best explanation I can come up with is that this is an IPS panel, but only one of the two polarizing films have been applied to the panel. Thus an “off” state would rotate the incoming light’s polarization, and an “on” state would still polarize the light, but a direction 90 degrees from the “off” state.

Above is a diagram illustrating the function of an IPS panel from Wikipedia.

I could see maybe there is a benefit to removing the incoming light polarizer from the LCD, because this polarizer would have to absorb, by definition, 50% of the energy of the incident unpolarized light, converting that intense incoming light into heat that could degrade the panel.

However, I couldn’t find any evidence of a detached polarizer anywhere in the backlight path. Perhaps someone with a bit more experience in liquid crystal panels could illuminate this mystery for me in the comments below!

Speaking of the backlight path – let’s return to digging into the printer!

About an inch behind the LCD is a diffuser – a clear sheet of plastic with some sort of textured film on it. In the photo above, my hand is held at roughly the exit plane of the LED array, demonstrating the diffusive properties of the optical element. My crude tests couldn’t pick up any signs of polarization in the diffuser.

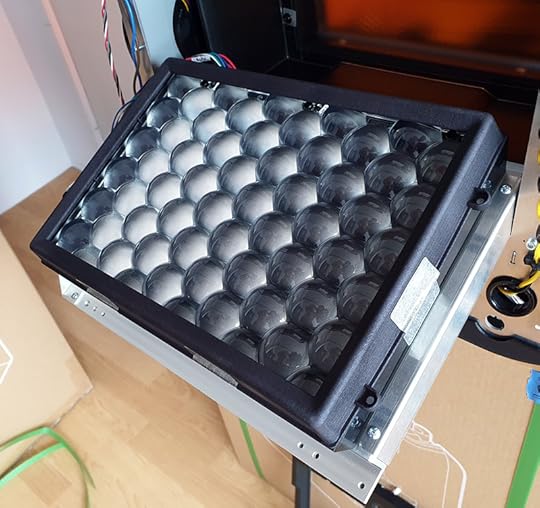

Beneath the diffuser is the light source. The light source itself is a sandwich consisting of a lens array with another laminated diffuser texture, a baffle, an aluminum-core PCB with LED emitters, and a heat sink. The heat sink forms a boundary between the inside and outside of the printer, with the outside surface bearing a single large fan.

Below is a view of the light source assembly as it comes out of the printer.

Below is some detail of the lens array. Note the secondary diffuser texture film applied to the flat surface of the film.

Below is a view of the baffle that is immediately below the lens array.

I was a bit baffled by the presence of the baffle – intuitively, it should reduce the amount of light getting to the resin tank – but after mating the baffle to the lens assembly, it becomes a little more clear what its function might be:

Here, we can see that the baffle is barely visible in between the lens elements. It seems that the baffle’s purpose might be to simply block sidelobe emissions from the underlying dome-lensed LED elements, thus improving light uniformity at the resin tank.

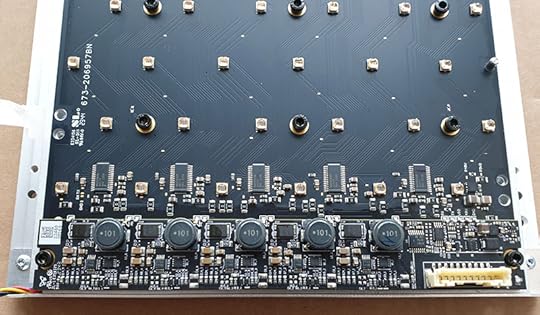

Beneath the baffle is the LED array, as shown below.

And here’s a closer look at the drive electronics:

There’s a few interesting aspects about the drive electronics, which I call out in the detail below.

The board is actually two boards stacked on top of each other. The lower board is an aluminum-core PCB. If you look at the countersunk mounting hole, as highlighted by the buff-colored circle, you can see the shiny inner aluminum core reflecting light.

If you’re not already familiar with metal-core PCBs, my friends at King Credie have a nice description. From their site:

The most economical (and most common) metal-core stack-up is a sheet of aluminum that has a single-layer PCB bonded to it. This doesn’t have as good thermal performance as a copper-core board with direct thermal heat pads, but for most applications it’s good enough (and much, much cheaper).

However, because the aluminum board is single-layer, routing is a challenge. Again, referring to the detail photo of the board above, the green circle calls out a big, fat 0-ohm jumper – you’ll see many of them in the photo, actually. Because of this topological limitation, it’s typical to see conventional PCBs soldered onto a metal-core PCB to instantiate more complicated bits of circuitry. The cyan circle calls out one of the areas where the conventional PCB is soldered down to the metal-core PCB using edge-plated castellations. This arrangement works, but can be a little bit tricky due to differences in the thermal coefficient of expansion between aluminum and FR-4, leading to long-term reliability issues after many thermal cycles. As one can see from this image, a thick blob of solder is used to connect the two boards. The malleability of solder helps to absorb CTE mismatch-induced thermal stresses.

The light source itself uses the MAX25608B, a chip capable of individually dimming up to 12 high-current LEDs in series (incidentally, I recently made a post covering the theory behind this kind of lighting topology for IRIS). This is not a cheap chip, given the Maxim brand and the AEC-Q100 automotive rating (although, the automotive rating means it can operate at up to 125 °C – a great feature for a chip mounted to a heat sink!), but I can think of a couple reasons why it might be worth the cost. One is that the individual dimming control could give Formlabs the ability to measure each LED in the factory and match brightness across the array, through a per-printer unique lookup table to dim the brightest outliers. Another is that Formlabs could simply turn off LEDs that are in “dark” regions of the exposure field, thus reducing wear and tear on the LCD panel. The PreForm software could track which regions of the LCD have been used the least, and automatically place prints in those zones to wear-level the LCD. Perhaps yet another reason is that the drivers are capable of detecting and reporting LED faults, which is helpful from a long-term customer support perspective.

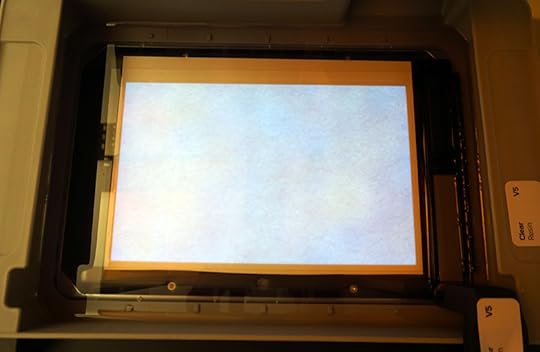

To investigate the light uniformity a bit more, I defeated the tank-close sensors with permanent magnets, and inserted a sheet of white paper in between the resin tank and the LCD to capture the light exiting the printer just before it hits the resin.

However, a warning: don’t try this without eye protection, as the UV light put out by the printer can quickly damage your eyes. Fortunately, I happen to have a pair of these bad boys in my lab since I somewhat routinely play with lasers:

Proper eye safety goggles will have their protection bandwidths printed on them: keep in mind that regular sunglasses may not offer sufficient protection, especially in non-visible wavelengths!

With the resin tank thus exposed, I was able to tell the printer to “print a cleaning sheet” (basically a single-layer, full-frame print) and capture images that are indicative of the uniformity of the backlighting:

Looks pretty good overall, but with a bit of exposure tweaking on the camera, we can see some subtle non-uniformities:

The image above has some bubbles in the tank from the mixer stirring the resin. I let the tank sit overnight and captured this the next day:

The uniformity of the LEDs changes slightly between the two runs, which is curious. I’m not sure what causes that. I note that the “cleaning pattern” doesn’t cause the fan to run, so possibly the LEDs are uncompensated in this special mode of operation.

The other thing I’d re-iterate is that without manually tweaking the exposure of the camera, the exposure looks pretty uniform: I cherry-picked a couple images so that we can see something more interesting than a solid bluish rectangle.

Other Features of Note

I spent a bit longer than I thought I would poking at the light path, so I’ll just briefly touch on a few other features I found noteworthy in the Form 4.

I appreciated the new foam seal on the bottom of the case lid. This isn’t present on the Form 3. I’m not sure exactly why they introduced it, but I have noticed that there is less smell from the printer as it’s running. For a small urban office like mine, the odor of the resin is a nuisance, so this quality of life improvement is appreciated.

I mentioned earlier in this post the replaceable HEPA filter cartridge on the intake of a blower that creates a positive pressure inside the optics path. Above is a photo of the filter. I was a little surprised at how loose-fitting the filter is; usually for a HEPA filter to be effective, you need a pretty tight fit, otherwise, particulates just go around the filter.

The small plastic protrusion that houses the camera board (shown above) also contains the resin level sensor (shown below).

The shape of the transducer on the sensor makes me think that it uses an ultrasonic time-of-flight mechanism to detect the level of the liquid. I’m impressed at the relative simplicity of the circuit – assuming I’m correct about my guess about the sensor, it seems that the STM32F303 microcontroller is directly driving the transducer, and the sole external analog circuit is presumably an LNA (low noise amplifier) for capturing the return echo.

The use of the STM32 also indicates that Formlabs probably hand-rolled the DSP pipeline for the ultrasound return signal processing. I would note that I did have a problem with the printer overfilling a tank with resin once during my evaluation. This could be due to inaccuracy in the sensor, but it could also be due to the fact that I keep the printer in a pretty warm location so the resin has a lower viscosity than usual, and thus it flows more quickly into the tank than their firmware expected. It could also be due to the effect of humidity and temperature on the speed of sound itself – poking around the speed of sound page on Wikipedia indicates that humidity can affect sound speed by 0.1-0.6%, and 20C in temperature shifts things by 3% (I could find neither a humidity nor an air temperature sensor in the region of the ultrasonic device). This seems negligible, but the distance from the sensor to the tank is about 80mm and they are filling the tank to about 5mm depth +/- 1mm (?), so they need an absolute accuracy of around 2.5%. I suspect the electronics itself are more than capable of resolving the distance, as the time of flight from the transducer and back is on the order of 500 microseconds, but the environmental effects might be an uncompensated error factor.

Nevertheless, the problem was quickly resolved by simply pouring some of the excess resin back into the cartridge.

Speaking of which, the Form 4 inherits the Form 3’s load-cell for measuring the weight of the resin cartridge, as well as the DC motor-driven pincer for squishing the dispenser head. The image above shows the blind-mating seat of the resin cartridge, with the load cell on the right, and the dispenser motor on the left.

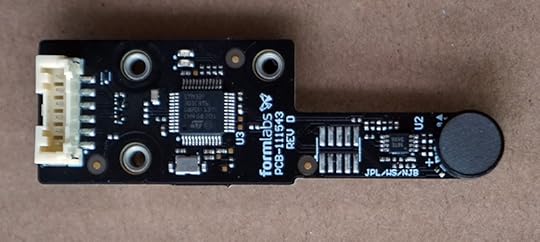

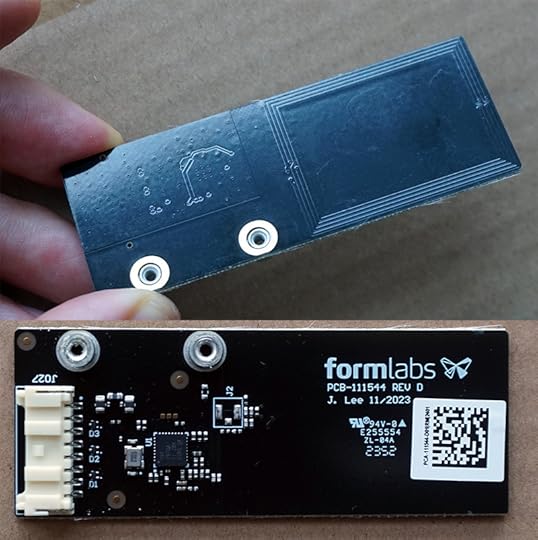

A pair of 13.56 MHz RFID/NFC readers utilizing the TRF7970 allow the Form 4 to track consumables. One is used to read the resin cartridge, and the other is used to read the resin tank.

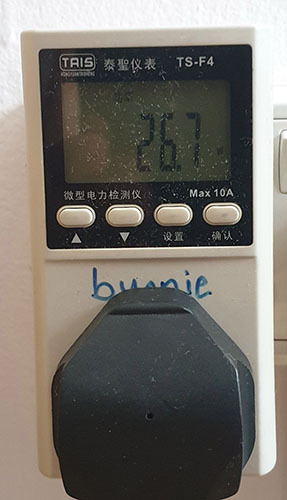

Finally, for completeness, here’s some power numbers of the Form 4. On standby, it consumes around 27 watts – just a hair more than the Form 3. During printing, I saw the power spike as high as 250 watts, with a bit over 100 watts on average viewed at the plug; I think the UV lights alone consume over 100 watts when they are full-on!

Epilogue

Well, that’s a wrap for this teardown. I hope you enjoyed reading it as much as I enjoyed tearing through the machine. I’m always impressed by the thoroughness of the Formlabs engineering team. I learn a lot from every teardown, and it’s a pleasure to see the new twists they put on old motifs.

While I wouldn’t characterize myself as a hardcore 3D printing enthusiast, I am an occasional user for prototyping mechanical parts and designs. For me, the dramatically faster print time of the Form 4 and reduced resin odor go a long way towards reducing the barrier to running a 3D print. I look forward to using the Form 4 more as I improve and tune my IRIS machine!

May 30, 2024

Name that Ware, May 2024

The Ware for May 2024 is shown below.

This is a guest ware, but I’ll reveal the contributor when I reveal the ware next month, as the name and link would also lead to the solution.

Andrew Huang's Blog

- Andrew Huang's profile

- 32 followers