Oxford University Press's Blog, page 846

February 12, 2014

Peak shopping and the decline of traditional retail

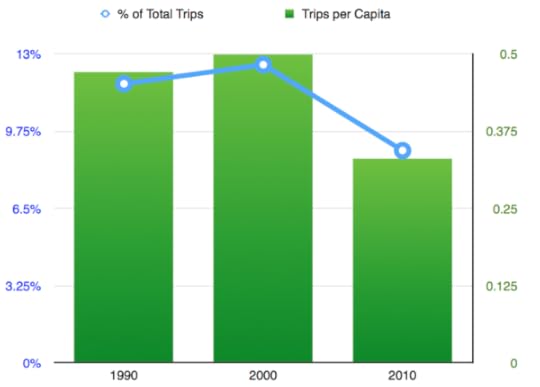

Shopping trips now comprise fewer than 9% of all trips, down from 12.5% in 2000, according to our analysis of the Twin Cities Travel Behavior Inventories. This is consistent with other results from the American Time Use Survey. They are down by about one-third in a decade.

Trends in Shopping Travel in the Minneapolis-St. Paul region. Source: Metropolitan Council Travel Behavior Inventory.

When we want to eat at home but not prepare the food, urban dwellers have options. Some restaurants offer Delivery as well as Take-Away, others offer Take-Away but don’t Deliver, and some specialize in Delivery and avoid the storefront. For the customer who is not out and about, Delivery is more convenient. For the customer who is passing by the restaurant anyway. Ordering ahead and doing Take-Away makes a lot of sense, since there is no waiting for the delivery, the additional distance is small to nil, and tipping charges (or delivery surcharges) are avoided. Drive-thru is Take-Away for fast food (though you can still go into the establishment and take-away as well), which avoids the pre-ordering step, arguably at the cost of food quality.

When we want to consume non-food items, we also have options. There is of course the store.

The block I live on of mostly single family homes with some duplexes and apartments, in a quiet Minneapolis neighborhood, once had two small grocery stores, founded before the days of cheap at home refrigeration and before larger grocery chains took off. One is now housing, the other a small restaurant.

If we did not have easy access to the store, or the store’s variety were limited, we could order from a catalog, like the Sears Wish Book. The catalog era was enabled by Rural Free Delivery, and was as fast as the supply chain of the time (which is to say, as fast they could, but nothing like today). Door-to-door sales was also common in this period, as there would be more likely to be someone at home to sell to.

Catalogs were replaced by the Internet, and Sears by Amazon. Not only can we do the same thing differently, we can do many more things with the technology of the world wide web. Amazon turns 20this year, so we cannot really consider this new anymore.

The early dot-com boom had a number of firms attempting same day if not same hour delivery. That didn’t work out as well as hoped, but like video conferencing and automated (if not flying) cars, it is an inevitable part of the future. There are lots of models out there for solving the last mile delivery problem less expensively than today: lockers or drop boxes (for less shipping costs, goods will be delivered to a locker rather than your doorstep), peer-to-peer delivery services (friends will pick up goods for you), and so on. Today we already have three national networks doing delivery which are cost effective for many types of goods (USPS, UPS, FedEx), as well as specialists (local stores that deliver their own products (furniture, appliances, grocers, newspapers, milk), though one can certainly imagine some others emerging. Amazon is even trying to patent pre-cognition, sending you what you are going to order before you order it.

What goods will you have delivered? Anything that is standardized, commodified, and whose delivery is easily automated. Amazon entered the market with books, and decimated the big box book sellers like Borders and Barnes and Noble. Borders and B&N had earlier acquired and then put-down many mall-based neighborhood bookstores (Walden, B-Dalton). The mall-based chains had themselves pushed out the independent neighborhood bookstores. For the book reader, we now have access to many more books than we did 20 years ago. For the nostalgic, we obviously lost something as well. Such is progress. Books were relatively easy kindling for this revolution, the International Standard Book Number (ISBN) code had been around since 1965. There is a long-tail of desired, but still standard items. There are economies of scale. They are easy to ship (and even easier to ship in electronic versions).

Music is seemingly similar. Once there was the neighborhood record shop, then the national (mall-centric) chain, then big boxes started to get in on the act. The technology of music changed faster than the book, moving from vinyl to tape to CD. In contrast with books, customers digitized and shared their music before the music industry could get their act together. Ultimately Apple’s iTunes brought prices down enough that listening to music is again more legal than illegal, and then new distribution mechanism (internet radio) changes the market again. Music is standardized, commodified, and the sequence in which you listen is automatically customizable using services like Pandora and iTunes Radio, among many others. While there is copyright-violating sharing of eBooks, it is not of the same order of magnitude as music. (Just search for your favorite book followed by PDF, you might be surprised to find it on a non-US website). Is downloading my own book illegal?

And then we get other items, all commodified though not digitized, that are amenable to the new distribution system: from batteries to baked goods, from Kindles to kites, which can all be ordered and delivered within 48 hours (if not sooner). Even custom goods get sold on places like Etsy. While used (and new) items both standard and non-standard are offered on Ebay.

All of these deliveries reduce my travel to the store, while increasing travel in the logistics supply chain, but generally reduce travel overall.

The decline of shopping travel is one aspect of the decline of personal travel overall, and has many knock-on effects. We need fewer roads. We need less parking. We need fewer stores and shopping centers. We inventory more at home (delivery might entail different economies of scale than fetching from the store). We might engage in other out-of-home activities to substitute for shopping as “entertainment”, but it won’t fully substitute.

Eventually we may have replicators, or pneumatic tubes, or good 3-D printers, and delivery as we think of it now will also decline. Or we may decide to consume less overall. But we can fairly safely extrapolate that, for a while, our 20th century retail infrastructure and supporting transportation system of roads and parking is overbuilt for the 21st century last-mile delivery problems in an era with growing internet shopping.

David M. Levinson is Professor of Civil Engineering and RP Braun/CTS Chair in Transportation at the University of Minnesota. He is also the co-author of the second edition of The Transportation Experience: Policy, Planning, and Deployment.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only technology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Peak shopping and the decline of traditional retail appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSecond childhoodCelebrating Charles Darwin’s birthdayHow electronic publishing is changing academia for the better

Related StoriesSecond childhoodCelebrating Charles Darwin’s birthdayHow electronic publishing is changing academia for the better

Second childhood

In my beginning is my end.

TS Eliot, East Coker

Embryologists who study the beginning of life, and gerontologists who study its end, interact rather little. This is hardly surprising: the former work with growth, construction and preparation for the long life ahead, while the latter work with loss, decline, and the inevitable journey to oblivion. Sometimes, though, different sciences connect in surprising ways and, when they do, discoveries can be made that completely change our understanding of both. Just such a fruitful collision happened very recently, the critical experiments appearing in papers from two Spanish laboratories (Manuel Serrano’s and William Keyes’s) in November’s issue of Cell. The groups’ findings may lead to a radical shift in the way we understand why and how we age.

Ageing can be seen at all levels from whole bodies to individual cells. As cells live, they suffer many types of damage; some is quickly repaired but some cannot be. When a cell is alive but irreparably damaged, it enters a specific state called cell senescence, easily detected because it involves the continual synthesis of a set of characteristic proteins. Senescent cells relinquish their ability to multiply, leaving the task of tissue renewal to their undamaged neighbours. This makes sense, teleologically, because a cell with badly damaged chromosomes, for example, would be likely to produce daughters with incomplete genomes that might give rise to a tumour. As well as shutting off proliferation, senescent cells secrete signalling proteins that trigger local inflammation. This too makes sense: one possible cause of damage is infection, and the inflammation brings defence systems into the area. Less easy to understand is the secretion by senescent cells of proteins that cause neighbouring cells to behave in apparently unhelpful ways, remodelling healthy tissue into a scar-like mess (fibrosis), altering blood vessels and even helping cancers grow. These changes are part of bodily ageing, and may cause neighbours to suffer collateral damage and to enter the senescent state themselves, making things worse. Some scientists call this process ’inflam-ageing’, to underline its unhelpful nature.

Ageing can be seen at all levels from whole bodies to individual cells. As cells live, they suffer many types of damage; some is quickly repaired but some cannot be. When a cell is alive but irreparably damaged, it enters a specific state called cell senescence, easily detected because it involves the continual synthesis of a set of characteristic proteins. Senescent cells relinquish their ability to multiply, leaving the task of tissue renewal to their undamaged neighbours. This makes sense, teleologically, because a cell with badly damaged chromosomes, for example, would be likely to produce daughters with incomplete genomes that might give rise to a tumour. As well as shutting off proliferation, senescent cells secrete signalling proteins that trigger local inflammation. This too makes sense: one possible cause of damage is infection, and the inflammation brings defence systems into the area. Less easy to understand is the secretion by senescent cells of proteins that cause neighbouring cells to behave in apparently unhelpful ways, remodelling healthy tissue into a scar-like mess (fibrosis), altering blood vessels and even helping cancers grow. These changes are part of bodily ageing, and may cause neighbours to suffer collateral damage and to enter the senescent state themselves, making things worse. Some scientists call this process ’inflam-ageing’, to underline its unhelpful nature.

Signals that alter the behaviour of other cells are very common during embryonic development, and in this context they are useful. In the ever-changing anatomy of a developing body, specific clusters of cells take charge of a particular aspect of body-building. A signalling centre at the end of the limb, for example, is important in making the fingers different from the wrist, the wrist different from the fore-arm, etc. Similarly, signals from the roof-plate of the developing brain set up various zones of the brain, and also the cell migrations that will later make most of the face. There are many other examples of signalling centres and cells within them, though very active in communication, seldom multiply. Embryonic tissues are fresh and new, not being alive for long enough to have accumulated much damage, so they would seem an unlikely place to find senescent cells. Nevertheless, the Serrano and Keyes laboratories set out to to look for signs of senescence in the young, healthy embryos of mice, chicks and humans. They found them — in surprisingly large numbers.

The senescent cells of embryos were not scattered randomly, as would be expected if entering the senescent state were just a response to damage, but were instead located in particular tissues. Some of them were located in temporary structures that are made during development but destroyed before birth, serving the needs of a developing human rather as scaffolding serves the needs of a new building. Here, cell senescence may just be to do with cells preparing to be eliminated. The rest of the senescent cells were located in places altogether more surprising; they made up some of the embryo’s key signalling centres, including the end of the limb and the roof-plate of the brain. Not only are these cells in a senescent state: they need to be for development to take place properly. Mice genetically engineered so that these cells cannot become senescent show abnormal gene expression in their developing limbs, and the limbs end up growing abnormally.

Why are cells apparently becoming senescent in signalling centres, even though they are not about to be cleared away? One important clue comes from bringing together information from embryology and from gerontology. Comparing the list of the signalling molecules released by the signalling centre of the developing limb with the list released by adult senescent cells reveals something startling: the sets overlap substantially. This raises an intriguing possibility, which would imply that we have got this whole senescence thing the wrong way round.

Researchers discovered the ‘senescent’ cell state in ageing research and became puzzled that, while some aspects of it were helpful in repair and in suppressing cancers, some things the cells secrete are unhelpful and cause inflam-ageing. The new data shows that ‘senescent’ cells are responsible for secreting very similar sets of molecules to control embryonic development. What if the original ‘point’ of the senescent state had nothing to do with ageing and damage, but was all about signalling to control development of primitive embryos? What it is not a ‘senescent’ cell state at all, but a ‘signalling centre’ cell state?

Small, short-lived animals do not need elaborate defences against cancer and slowly accumulating damage; they get eaten before it matters. We large, longer-lived animals do need these defences, and by the time we came to evolve, the ‘signalling centre’ cell state, with its automatic shut-down of multiplication and its secretion of a bunch of signalling molecules, was already there in our developmental repertoire. It may have taken only a small amount of evolutionary change to connect damage detection systems to drive activation of this cell state. With the connection achieved, our damaged, adult cells would automatically shut down and give signals that, an an adult body, are associated with repair and defence. Job done! Well, almost… some of those signals still provoke tissue modelling even in an adult body, where it is no longer appropriate. The convenience of stealing an old embryonic system for the new purpose of controlling damage, rather than going to the trouble of evolving a new purpose-built one, has its price. The price label appears in every line on our faces, every narrowing artery, every aching joint.

It is too early to say how this story will turn out when more experiments have been done, but the possibility that we have had the whole story round the wrong way is intriguing. It would mean that we need to understand inflam-ageing as an effect of unhelpfully reactivated embryonic development. Medically, that may change a lot.

Jamie Davies is Professor of Experimental Anatomy at the University of Edinburgh. Since 1995, he has run his own laboratory, with a multi-disciplinary focus on discovering how mammalian organs construct themselves and how we can use this knowledge to build new tissues and organs for those in need. His latest book is Life Unfolding: How the Human Body Creates Itself.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

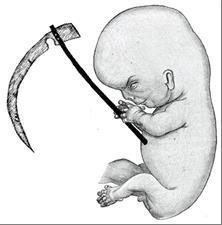

Image credit: Image by Jamie Davies. This is a composite: the embryo from Gray’s Anatomy (original edition, public domain) and the scythe from Personificación de la muerte by Incry. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Second childhood appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCelebrating Charles Darwin’s birthdayThe new DSM-5: changes in the diagnosis of autism and intellectual disabilityThe genesis of computer science

Related StoriesCelebrating Charles Darwin’s birthdayThe new DSM-5: changes in the diagnosis of autism and intellectual disabilityThe genesis of computer science

February 11, 2014

Celebrating Charles Darwin’s birthday

Darwin Day marks the anniversary of the birth of Charles Darwin on 12 February 1809. One could come up with several creative ways to celebrate the life of such an influential and revered scientist—baking a cake with 73 candles in honor of Darwin’s 73 years of life, or taking a walk through a local park or nature reserve in an attempt to make observations about wild animals, to name a few. But why not spend this Darwin Day learning a fun fact or two that you didn’t already know? We compiled a list of Oxford’s books on the life and philosophies of Darwin, and discovered that when it comes to Darwin, there is much to be learned.

Darwin: A Very Short Introduction by Jonathan Howard

Are you looking for a basic overview of Darwin’s work? Look no further than this Very Short Introduction by Jonathan Howard. Howard discusses Darwin’s belief that humans have evolved over time from apes—a fundamental principle from On the Origin of Species. This Very Short Introduction illuminates the importance of Darwin’s evolutionary philosophies in shaping modern biological principles.

Evolution: A Very Short Introduction by Brian Charlesworth

The writings of Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, which are celebrated within this Very Short Introduction, were published over 150 years ago. Brian Charlesworth highlights the evolutionary philosophies of both scientists as they are presented in these works.

Darwin and His Children: His Other Legacy by Tim M. Berra

Darwin and His Children: His Other Legacy by Tim M. Berra

Darwin not only studied how different species have evolved in order to produce viable offspring, he also produced ten offspring of his own. Dedicating one chapter to each of Darwin’s children, Tim Berra sheds light on the lives of these children—some of whom went on to study science just like their father.

On the Origin of Species, Revised Edition by Charles Darwin; edited by Gillian Beer

Most people are familiar with Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. However, this revised edition offers explanatory notes—including a Register that details all of the writers to which Darwin refers within the text—that will provide readers with an even firmer grasp on Darwin’s evolutionary theories.

Evolutionary Writings: Including the Autobiographies by Charles Darwin, edited by James A. Secord

Evolutionary Writings: Including the Autobiographies by Charles Darwin, edited by James A. Secord

Darwin wrote many texts that highlight his evolutionary philosophies and feature the experiments that solidified these principles. Darwin even wrote an autobiography, titled Recollections. Evolutionary Writings, an Oxford World Classic, features key chapters from several of Darwin’s most influential writings: the Journal of Researches on the Beagle voyage, On the Origin of Species, The Descent of Man, and Recollections.

In Darwin’s Shadow: The Life and Science of Alfred Russel Wallace: A Biographical Study on the Psychology of History by Michael Shermer

Far less familiar than the name of Charles Darwin is that of Alfred Russel Wallace. However, Wallace came to many of the same conclusions as Darwin regarding evolutionary theory. Reading this book will bring the life and studies of Wallace out of Darwin’s shadow—further solidifying the discoveries that both of these scientists made.

Alfred Russel Wallace: Letters from the Malay Archipelago by John van Wyhe and Kees Rookmaaker

Alfred Russel Wallace: Letters from the Malay Archipelago by John van Wyhe and Kees Rookmaaker

Like Darwin, Wallace traveled overseas in order to come to the conclusion that evolution occurs via natural selection. John van Wyhe and Kees Rookmaaker highlight Wallace’s letters from this voyage, revealing many fascinating details about this less-recognized naturalist.

Darwin the Writer by George Levine

Most people know Darwin for his contributions to science. But had Darwin been unable to convey all of his discoveries in an eloquent manner, these findings may have never been shared. By highlighting the importance of Darwin’s writing style and argument construction, George Levine provides readers with a new perspective on the significance of Darwin’s work.

Darwin’s Camera: Art and Photography in the Theory of Evolution by Phillip Prodger

Darwin’s Camera: Art and Photography in the Theory of Evolution by Phillip Prodger

Did you know that Darwin was the first person to compile a scientific narrative told through the use of pictures, in his masterpiece Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals? Darwin never studied photography or art, but he was very interested in these subjects—forging friendships with many revered animal artists, painters, and sculptors, some of whom traveled with Darwin aboard the HMS Beagle. Through this narrative, Phillip Prodger sheds light on the way in which Darwin influenced how photographs are viewed.

Living with Darwin: Evolution, Design, and the Future of Faith by Philip Kitcher

The presentation of Darwin’s theories on evolution was far from controversial. In Living with Darwin, Philip Kitcher highlights evidence for evolution, Creation Science, and Intelligent Design—illuminating some of the sources of resistance to Darwin’s philosophies.

Erasmus Darwin: Sex, Science, and Serendipity by Patricia Fara

Erasmus Darwin: Sex, Science, and Serendipity by Patricia Fara

Few people know that Charles Darwin’s theories on evolution were greatly influenced by the similar philosophies of his grandfather, Erasmus Darwin. Erasmus was well-known during the Enlightenment for his beliefs regarding sex and science—many of which were embedded into his poetry. Patricia Fara depicts these evolutionary philosophies and more in Erasmus Darwin: Evolution, Design, and the Future of Serendipity.

Darwin in the Archives: Papers on Erasmus Darwin and Charles Darwin from the Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History and Archives of Natural History by E. Charles Nelson and Duncan Porter

The Society of the History of Natural History celebrated the work of Darwin and its influence on contemporary science on the bicentenary of Darwin’s birth by publishing Darwin in the Archives. This book features reproductions of papers on Charles Darwin and Erasmus Darwin from the Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History and Archives of Natural History.

Happy reading! But most importantly—happy birthday, Darwin!

Charles Darwin was a British naturalist, who studied medicine in Edinburgh followed by theology at Cambridge University, intending a career in the Church. However, his interest in natural history led him to accept an invitation in 1831 to join HMS Beagle as naturalist on a round-the-world voyage. After his return five years later he published works on the geology he had observed. He was also formulating his theory of evolution by means of natural selection, but it was to be 20 years before he published The Origin of Species(1859), prompted by similar views expressed by Alfred Russel Wallace. Among his later works was The Descent of Man (1871).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Celebrating Charles Darwin’s birthday appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWill the real Alfred Russel Wallace please stand up?The new DSM-5: changes in the diagnosis of autism and intellectual disabilityAutism Sunday 2014: controversies and resolutions

Related StoriesWill the real Alfred Russel Wallace please stand up?The new DSM-5: changes in the diagnosis of autism and intellectual disabilityAutism Sunday 2014: controversies and resolutions

How electronic publishing is changing academia for the better

Oxford Scholarship Online (OSO) launched in 2003 with 700 titles. Now, on its tenth birthday, it’s the online home of over 9,000 titles from Oxford University Press’s distinguished academic list, and part of University Press Scholarship Online. To celebrate OSO turning ten, we’ve invited a host of people to reflect on the past ten years of online academic publishing, and what the next ten might bring.

By Hannah Skoda

When I started in my current post, one of my students, off to a nightclub, very cheekily asked me whether when I was young, they were still called discos. The same sorts of feelings are coming to characterize attitudes towards books – our students find it hard to imagine a time when nothing was available electronically. They are helped immensely by the possibilities of electronic publication, not just by the ease of access, but also by the different format, abstracts at the start of each chapter, search facilities, and so on. It makes ‘gutting a book’ a particularly efficient process, as there is very little mess to clear up afterwards and very little time wasted. And this has exciting and challenging implications for authors. Drafting abstracts for each chapter is very good discipline, as is the need to think especially carefully before using key terms, in the knowledge that readers can easily search them and use them as anchors to guide their reading.

All this suggests that electronic publications pander to our need to save time. But there is something more to it than that. Talking about reading in the late sixteenth century, Michel de Montaigne warned that ‘It’s an indication that it hasn’t been cooked properly, and a sign of indigestion, when someone regurgitates the meat that he has just swallowed’ (Essais, 1.26): the ideal reader should chew and digest the text. In a sense, it’s our responsibility as writers, publishers, and readers now to ensure that the possibilities of electronic publishing foster this kind of active reading, rather than a passive one. Already, the reader is able to navigate his or her own way through the text in much more independent ways than the traditional book tends to encourage; the flexibility of the electronic format perhaps allows easier comparison between texts, and the transitory nature of the word on the screen somehow looks less dogmatic.

Michel de Montaigne, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

There are exciting possibilities for the future: Michel de Montaigne, who so loved to interpolate new thoughts into his text giving it a life of its own, would have fascinated by the possibilities of hypertext – not only can one add footnotes and references, but one can comment on one’s own thought processes, critique them and subject them to endless scrutiny. A figure like Montaigne might have added such hypertextual comments, and then felt tempted to comment on the comments: the process of something like an infinite regression opens up the horizons of thought and scholarship in exciting and challenging ways. To some extent, writers are already engaging with these possibilities, but it will be particularly exciting to see more traditionally minded disciplines, such as history, rising to the challenge of endless self-interrogation. We can imagine using hypertext to show thought in motion, to set texts in dialogue with each other, and, most of all, to keep us on our intellectual toes.

All the while, the form in which we access texts becomes more varied and allows us to read in more contexts. Snuggled under the bedclothes in the dark with a Kindle, or sitting stolidly in front of the computer screen. And the more choice we have, the more personal the process of reading can become. It’s quite possible that ease of access demystifies books and encourages us to be lazy readers, but it’s equally possible and far more exciting, that the electronic format and its myriad possibilities will sharpen our reading practices, and make us more critical and more reflective, both as writers and as readers.

Dr. Hannah Skoda is a Tutorial Fellow in History at St. John’s College in Oxford where she teaches late medieval history. She is the author of Medieval Violence: Physical Brutality in Northern France, 1270-1330 and Legalism: Anthropology and History, both published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only education articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How electronic publishing is changing academia for the better appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUniversity libraries and the e-books revolutionVolume, variety, and online scholarly publishingGoing local: understanding regional library needs

Related StoriesUniversity libraries and the e-books revolutionVolume, variety, and online scholarly publishingGoing local: understanding regional library needs

A virtual journey in the footsteps of Zebulon Pike

Somewhere in the middle of the Great Plains in November 1806, the explorer Zebulon Pike worried that the lateness of the season jeopardized the completion of his expedition. A contemporary of Lewis and Clark, Pike commanded a US military party that was exploring the southwestern reaches of the Louisiana Purchase. With cottonwoods turning gold and the nights chilling, Pike resolved to “spare no pains” to accomplish the national objects of his voyage.

Two centuries later, in an era that fetishizes military sacrifice while veterans’ services and other public programs languish for want of funding, the anniversary of a soldier who vowed to spare no pains for his country invites meditation on the relationship between citizen, nation, and the military. Pike’s hypothetical pains quickly turned into literal bodily suffering, as he led his men into the Rocky Mountains on the morning of winter’s first blizzard. For eight weeks they wandered, lost among the passes, enduring cold, fatigue, and hunger.

The misery climaxed on 22 January, when Privates John Sparks and Thomas Dougherty developed frostbite so badly they could no longer walk. Pike had to leave them behind to save the party. Still unable to travel in February when a rescue party returned for them, the hobbled soldiers sent Pike the toe bones that by then had separated from their gangrenous feet, begging him “by all that was sacred not to leave them to die.”

“Ah! Little did they know my heart,” Pike wrote in his journal. He vowed to stop at nothing in order to return them to “the bosom of a grateful country.” Sparing no pains now included body parts. Pike’s response expressed a covenant that he believed bound people and nation. Citizens owed their country sacrifice; their country owed them gratitude.

Pikes Peak

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

In 1806, while Lewis and Clark were on their way home from their historic voyage, Lieutenant

Zebulon Montgomery Pike departed St. Louis at the helm of a U.S. military expedition to

explore the southwestern reaches of the Louisiana Purchase. His aim was to find the headwaters

of the Arkansas River and return via the Red River. This slide show follows his route from his

sighting of Pikes Peak, pictured here, until his arrest by Spaniards in southern Colorado. Photo

by Jared Orsi.

Peak Sighting Spot

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

He first sighted Pikes Peak, which he called the Grand Peak, on November 15, 1806, near this

spot on the plains, between Las Animas and Lamar, Colorado. The 14,000-foot summit was

more than one hundred miles away. Photo by Jared Orsi.

Pawnee war party site

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

On November 22, Pike and his companions met a Pawnee war party on the Arkansas River,

perhaps near this spot. The Indians took some of Pike’s knives and tools. Pike would see no

other human beings until February 16. Photo by Jared Orsi.

Pikes Peak from Pueblo

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Pike parked his men here, at the confluence of the Arkansas River and Fountain Creek in modern

Pueblo, Colorado. Taking Dr. John Robinson and privates John Brown and Theodore Miller, he

set out to climb the Grand Peak, visible here in the background, on November 24. Photo by Brian

Lenz.

Mt. Rosa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

On November 26, they cached their blankets and food at the foot of the mountains and hiked up

a creek. Their view of the Grand Peak now blocked by lesser summits, they climbed all day.

Late in the afternoon, with daylight waning, they spied this peak, Mt. Rosa, and began ascending

it, perhaps hoping to get their bearings on the surrounding terrain. Photo by Jared Orsi.

Cave

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Near the summit of Mount Rosa, they huddled into this cave, which Colorado Springs attorney

John Murphy has marked with a sign. They tossed and turned all night, trying to find a smooth

surface on which to sleep. Photo by Jared Orsi.

Pikes Peak from Mt. Rosa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

After an hour’s hike the next morning, Thanksgiving Day, they reached the top of Mt. Rosa.

“The summit of the Grand Peak,” Pike wrote, now appeared at the distance of 15 or 16 miles

from us, and as high again as what we had ascended, and would have taken a whole day’s march

to have arrived at its base, when I believe no human being could have ascended to its pinical.”

The explorers turned around and returned to their companions on the plains. Photo by Jared

Orsi.

Confluence of Arkansas and Grape Creek

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

With the party regrouped, Pike led them into the Rocky Mountains on the morning of winter’s

first blizzard. Confused by several small streams joining near modern Cañon City, Pike camped

for several days in early December near this spot, where Grape Creek enters the Arkansas River.

Believing he had found the headwaters of the Arkansas, he elected to turn north in search of the

Red River, unaware that it was 300 miles to the southeast. Photo by Jared Orsi.

Upper Arkansas

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

On December 18, the party crossed Trout Creek Pass out of South Park. Spying a broad river

flowing south, Pike wrote in his diary that they had found the Red. From this spot, on U.S

Highways 24 and 285, not far from Buena Vista, Colorado, he looked across the valley at the

Collegiate Peaks. The bedraggled party was overjoyed finally to be heading home. Photo by

Jared Orsi.

10. Poncha Pass

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

A few of Pike’s contemporaries believe he had secret orders to spy on Spanish Santa Fe. Some

subsequent observers have suggested that as he followed the river south, he knew it was not the

Red and that he intended to cross the mountains to find Santa Fe. Though plausible, this is

theory founders at this spot, near where Pike camped on Christmas Day. If Pike intended to

cross to Santa Fe, this was the place to do it. Poncha Pass, southwest of Salida, Colorado,

offered an easy route. Photo by Jared Orsi.

11. Sangres

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

If he had any doubts about Poncha Pass, one glance to southeast would have cured him. To his

left loomed the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Scaling the mountains would never get any easier

than at Poncha Pass. Photo by Jared Orsi.

Confluence of Arkansas and Grape Creek

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

But the expedition continued downstream—as any party believing it was heading homeward

along the Red River would have done. Trapped in the steep-walled canyons that enclose the

Royal Gorge and unable to find food, the party neared starvation. At last, Pike emerged from the

chasm on his birthday, January 5, and beheld this familiar place. The brutal month wandering in

the mountains had yielded only the rediscovery of the Arkansas, which they had been following

since October. Photo by Jared Orsi.

Up Grape Creek

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

If he was still on the Arkansas, where was the Red? Still believing it to be to the southwest, Pike

launched the party up Grape Creek, pictured here, intending to cross the Sangres, something he

had deemed impossible a month before. Photo by Jared Orsi.

Wet Mountain Valley

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

This is the Wet Mountain Valley on nearly the same day of the year at about the same time of day

at about the same spot that Pike would have beheld it. With the sun setting over the Sangres and

little water or wood handy, Pike decided to keep marching, badly underestimating the distance to

the forested mountains across the valley. The consequences were disastrous. Photo by Jared

Orsi.

Grape Creek crossing

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The party crossed Grape Creek near here, getting their boot wet. By the time they made camp at

the foot of the mountains, the temperature was 10 degrees below zero. The party had marched

28 miles that day and several of the men could no longer walk on their frostbitten feet. Photo by

Jared Orsi.

Leaving Sparks and Daugherty

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

A few days later, Pike left Privates John Sparks and Thomas Daugherty behind near here, to face

the wilderness alone, unable to walk. Frostbite led to other problems. Hypothermia. Inability to

hunt. Starvation. The party repeatedly failed to cross the saw-toothed Sangres. Photo by Jared

Orsi.

San Luis Valley

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

After leaving yet another man, Hugh Menaugh, behind, the party finally straggled over the

Sangres and beheld San Luis Valley, depicted here somewhat south of where Pike would have

seen it. Photo by Jared Orsi.

Great Sand Dunes

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

On January 28, they passed through what is now Great Sand Dunes National Park, whose sandy

ripples he compared to “the sea in a storm.” Climbing one of the dunes, Pike saw river. Once

again, he thought he’d found the Red. Photo by Jared Orsi.

Rio Conejos

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Descending the river, the party made camp near here, a few miles up a tributary, the Rio Conejos,

in the southern part of Colorado’s San Luis Valley.

Pike Stockade

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

They built a small stockade and raised an American flag. For mysterious reasons, Robinson,

departed in search of Santa Fe. Some have attributed this, too, to Pike’s alleged secret orders.

Doubters say the pair knew exactly where they were and deliberately tried to get a glimpse of the

New Mexican capital. If so, Robinson took an odd route, heading not south, the obvious path to

Santa Fe, but southwest, the logical direction had he believed he was on the Red. Meanwhile

Pike sent a rescue party to retrieve the men stranded in the mountains. Photo by Jared Orsi.

National Historic Landmark entrance

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Before the rescuers returned, the Spanish army showed up. The commander ordered Pike to

lower his flag and accompany him to New Mexico. Pike, the officer said, had left the United

States. “What,” protested Pike, “is not this the Red?” “No, sir!” retorted the Spaniard, “the Rio

del Norte.” Pike was camped on the Rio Grande, on Spanish soil.” The Americans were now

headed for Santa Fe and a big detour. Today, the replica of Pike’s stockade, reconstructed at the

original site based on specifications in his journal, is a National Historic Landmark managed by

the state of Colorado. Photo by Jared Orsi.

Pike read widely in the popular advice literature of the day, which championed the rights of individuals to personal fulfillment. Liberating as it was though, individualism threatened to undermine deference, family, religion, and other constraints that had traditionally claimed to compel a citizens good behavior. Pike and others, therefore, tempered it with republicanism—the duty to forsake selfish interests for the good of others, especially the nation. “Be always ready to die for your country,” a young Pike scribbled in the margins of one of his favorite advice tracts. He spent most of his life trying to reconcile his willingness to die for his country with his desire to find individual personal fulfillment in life, and to win the social rewards he believed that merited.

Congress did not compensate the explorers for lost toes or other sacrifices. Other matters preoccupied the representatives. Britain was attacking American ships and impressing sailors, raising a national dilemma akin to Pike’s personal one: would Pike’s self-absorbed generation collectively sacrifice to defend the nation? War promised to remedy the nation’s diplomatic and cultural challenges. An external foe could unite self-interested individuals, who would sacrifice to defeat that very enemy. Pike, for one, itched to prove “that the sons are able to maintain the Independence handed down to us by our Fathers.”

After the Senate declared war in June 1812, he headed for the front lines, declaring, “You will hear of my Fame of my death.” He died in April 1813 at the Battle of York, one of the war’s few significant American victories. Newspapers and admiring biographers eulogized this ultimate sacrifice. The embattled James Madison administration—which had failed to beat its enemy on the battlefield—used figures like Pike to recast the war as being not about extracting concessions from Britain but about proving Americans were honorable.

As a result, for the next decade, Pike was the brightest star in the galaxy of American military martyrs. His glory far exceeded that of Meriwether Lewis, who killed himself while mired in debt and political scandal. Pike had won in death the status he had coveted in life.

Although Pike chose to sacrifice in the army, his world did not consider the military the only venue for doing so. In fact, contemporaries understood the American Revolution predominantly as a war in which civilians rose up to defeat a common enemy and then returned to their farms, leaving Europeans to their vice of standing armies. Pike fancied himself as a “Citizen Soldier.”

Today is different. Soldiers have become a specialized class, who sacrifice so that other citizens don’t have to. The nation celebrates them, making it easier to send them into harm’s way while asking little of the others. But the public is largely unwilling to fully support them before, during, or after their time of service.

Pike’s life, however, indicates the roots of this tragedy lie deep in history, in a never-fully-resolved paradox of American nationalism that celebrates both individualism and obligation to the community. The separation of soldiers and civilians originated during Pike’s life, at a moment when the republic narrowed from glorifying citizen sacrifice to lauding only soldier sacrifice. The anniversary of a citizen soldier sparing no pains recalls a path not taken but which remains an open option—a more genuine and widely shouldered commitment to the nation that would extoll citizen service rather than fetishize of the sacrifice of a few.

Jared Orsi is the author of Citizen Explorer: The Life of Zebulon Pike. He is Associate Professor of History at Colorado State University. He is the author of the prizing-winning Hazardous Metropolis: Flooding and Urban Ecology in Los Angeles.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A virtual journey in the footsteps of Zebulon Pike appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesClimbing Pikes Peak 200 years ago250 years since the contract that changed American historyThe new DSM-5: changes in the diagnosis of autism and intellectual disability

Related StoriesClimbing Pikes Peak 200 years ago250 years since the contract that changed American historyThe new DSM-5: changes in the diagnosis of autism and intellectual disability

Dona nobis pacem by Ralph Vaughan Williams

The cantata Dona Nobis Pacem by Ralph Vaughan Williams was written at a time when the country was slowly awakening to the possibility of a second European conflict. When invited to provide a work for the centenary of the Huddersfield Choral Society in October 1936, Vaughan Williams remembered that he had in his drawer an unpublished setting of Walt Whitman’s ‘Dirge for Two Veterans’, taken from Whitman’s 1865 collection Drum Taps inspired by the American Civil War which had just ended. Vaughan Williams had written it in 1911 before the First World War, and now resurrected it as the centrepiece of this new work, preceding it with two further poems by Whitman, also from Drum Taps: ‘Beat! Beat! Drums!’ and ‘Reconciliation’. He prefaced this group of Whitman poems with a setting of the words of the Agnus Dei of the Latin Mass, and followed it with a passage from a speech given in Parliament by John Bright in 1855 at the time of the Crimean War. (‘The Angel of Death has been abroad throughout the land; you may almost hear the beating of his wings …’. Vaughan Williams claimed to be the only composer ever to have set a passage from the proceedings of the House of Commons!) In the last two sections he used a series of passages drawn from the Old Testament which together express optimism for future peace. The text is rounded off with the verse from St Luke ‘Glory to God in the Highest and on earth peace, Good will towards men’ and a final repetition of the plea ‘Grant us peace’ in the work’s title.

Some have criticised the music because the ‘Dirge for two veterans’, of 1911, is stylistically a little apart from the remainder written in the winter of 1935–6. The ‘Dirge’ is as close as Vaughan Williams ever came to writing a Mahlerian funeral march (he was not a Mahler fan), and it certainly commands the attention in a different way to the music before and after. Nonetheless the whole work is welded together by the composer’s sense of urgency; as Simon Heffer, Vaughan Williams’ biographer, has said of Dona Nobis Pacem, his ‘main inspiration is drawn not from the soil of England, but from the whole world going mad around him’. The music for the words from Micah (‘nation shall not lift up a sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more …’), and thereafter, becomes more optimistic, a foreshadowing of the last movement Passacaglia of the future Fifth Symphony; but, unlike the later work, here the music returns to a state of hesitant prayer sung ppp by the chorus and solo soprano, a prayer that at the time was not to be granted.

Some have criticised the music because the ‘Dirge for two veterans’, of 1911, is stylistically a little apart from the remainder written in the winter of 1935–6. The ‘Dirge’ is as close as Vaughan Williams ever came to writing a Mahlerian funeral march (he was not a Mahler fan), and it certainly commands the attention in a different way to the music before and after. Nonetheless the whole work is welded together by the composer’s sense of urgency; as Simon Heffer, Vaughan Williams’ biographer, has said of Dona Nobis Pacem, his ‘main inspiration is drawn not from the soil of England, but from the whole world going mad around him’. The music for the words from Micah (‘nation shall not lift up a sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more …’), and thereafter, becomes more optimistic, a foreshadowing of the last movement Passacaglia of the future Fifth Symphony; but, unlike the later work, here the music returns to a state of hesitant prayer sung ppp by the chorus and solo soprano, a prayer that at the time was not to be granted.

Dona Nobis Pacem was performed many times in that anxious period leading up to the Second World War, and given its connections with both World Wars it is again being taken up by choral societies throughout the country as we come to commemorate the outbreak of the First. The work reminds us that war inevitably brings misery and loss. Vaughan Williams knew that as well as anyone yet at the same time he was convinced that, given the circumstances, this war needed to be fought. The composer, like everyone else, was a member of his community and while he was ready to warn his countrymen of the horrors that might lie ahead, he had no hesitation in playing his part in both of the great wars once they had started.

Hugh Cobbe OBE is the Director of the Vaughan Williams Charitable Trust.

In the fifty years since his death, Ralph Vaughan Williams has come to be regarded as one of the finest British composers of the 20th century. He has a particularly wide-ranging catalogue of works, including choral works, symphonies, concerti, and opera. His searching and visionary imagination, combined with a flexibility in writing for all levels of music-making, has meant that his music is as popular today as it ever has been. Dona Nobis Pacem is available from Oxford Sheet Music. Oxford Sheet Music is distributed in the USA by Peters Edition.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

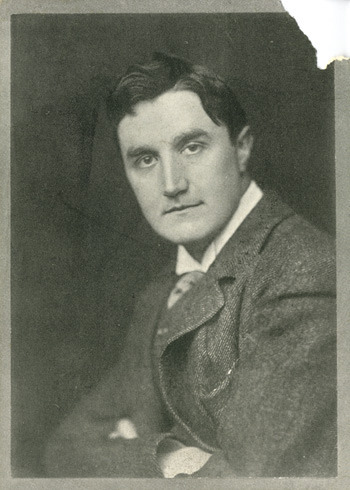

Image credit: Portrait of Ralph Vaughan Williams courtesy of OUP sheet music department. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post Dona nobis pacem by Ralph Vaughan Williams appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA day in the life of the Music Hire LibraryOxford’s top 10 carols of 2013Treasures from Old Holland in New Amsterdam

Related StoriesA day in the life of the Music Hire LibraryOxford’s top 10 carols of 2013Treasures from Old Holland in New Amsterdam

February 10, 2014

Treasures from Old Holland in New Amsterdam

The Frick Collection in New York recently closed its Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Hals: Masterpieces of Dutch Painting from the Mauritshuis exhibition of fifteen seventeenth-century Dutch paintings on loan from the Hague museum, which is currently closed for remodeling. The show (which has already been to San Francisco, Atlanta, and Tokyo, and opens next in Bologna) was a blockbuster, with visitors regularly forming lines wrapping around the building. I saw the exhibition near the end of its run, and can attest that the attention was well-deserved, and not just because this was likely the only chance many in the New York area would ever have to see these works. Among the paintings on view, more than one were drop-dead stunners. Much attention was naturally paid to Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, which is incredibly more arresting in person than it is in reproduction. On the afternoon I came, visitors also flocked around the Rembrandts (of course) and The Goldfinch by Carel Fabritius, the subject of a new bestseller by Donna Tartt. The small panel is a curiosity because of its subject matter, but paintings like the tranquil View of Haarlem with Bleaching Grounds by Jacob van Ruisdael and the big, lively “As the Old Sing, So Pipe the Young” by Jan Steen show the so-called Golden Age’s range of genius. The Frick’s own holdings complement the Mauritshuis paintings nicely. Henry Clay Frick, whose personal collection and mansion were used to establish the museum, bought works by Frans Hals, Rembrandt, and Johannes Vermeer.

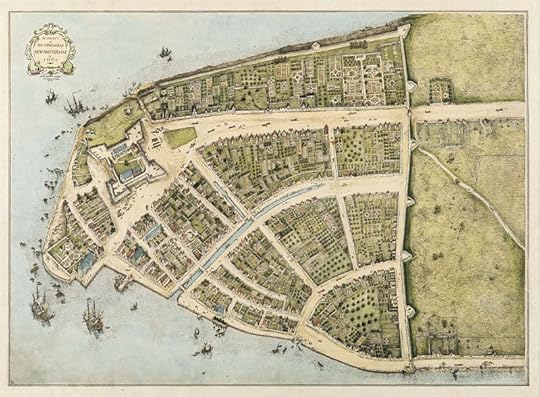

Redraft of the Castello Plan New Amsterdam in 1660. 31 x 40 cm Medium: printed map, color wash on paper. John Wolcott Adams and I.N. Phelps Stokes. New-York Historical Society Library, Maps Collection. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Old Masters of the Netherlands have long received a warm welcome in New York City, beginning with the first Dutch settlers in Manhattan in the 17th century. This founding history of the city is partly the reason why later collectors in New York were so drawn to Dutch paintings of the period:

“By the 1890s the taste of such tycoons as Andrew W. Mellon, J. Pierpont Morgan and Samuel H. Kress, on the other hand, had become synonymous with accredited Old Masters and 18th-century works. Typically these collections were large and historical, including works from the early Renaissance to the 18th century; some were almost encyclopedic, or even acquired in bulk.” (Grove Art Online, “USA, §XIII: Collecting and dealing”)

Wealthy New York merchants and bankers likely also felt a kinship with the bourgeois, Protestant Dutch society that fostered the Golden Age of Dutch painting. Although Americans also snapped up Italian Renaissance and contemporary French works on the international art market, the beautiful landscapes, lush still-lifes, and sensitive portraits of the Dutch masters, who rarely depicted nude figures or erudite, obscure subject matter, appealed to American attitudes and tastes.

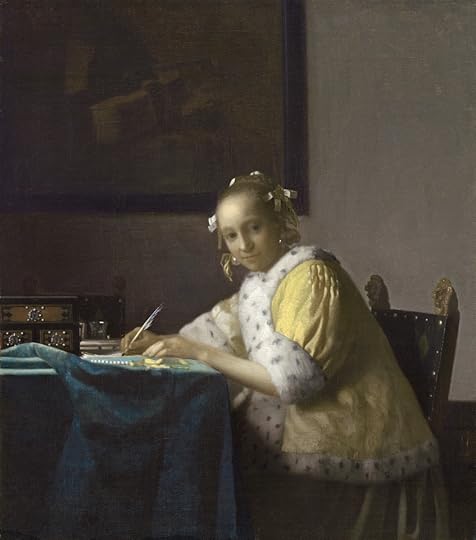

Johannes Vermeer, A Lady Writing, c. 1665. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, NGA Images. Bought by J. P. Morgan in 1907, the painting resided in New York City for decades. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Vermeer was the star of the Frick exhibition, his one painting in the show occupying its own room. The painter is especially well represented in New York: the master’s surviving works number only about 36, and Gotham boasts eight of them, five at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and three in the Frick’s permanent collection (five more are in other American cities). Manhattan movie theaters are now also screening the Oscar-nominated documentary “Tim’s Vermeer”, the story of software innovator Tim Jenison’s quest to recreate the Music Lesson using an optical apparatus he hypothesizes Vermeer used to compose his works. Although the resulting painting doesn’t even come close to the original, the story is a testament to the mystery of his technique and Americans’ ongoing fascination with the artist and his historical milieu.

Kandice Rawlings is Associate Editor of Oxford Art Online and the Benezit Dictionary of Artists. She holds a PhD in art history from Rutgers University.

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access — and simultaneously cross-search — an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Treasures from Old Holland in New Amsterdam appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSelfies and the history of self-portrait photographyAn Oxford Companion to Valentine’s DayShanghai rising

Related StoriesSelfies and the history of self-portrait photographyAn Oxford Companion to Valentine’s DayShanghai rising

250 years since the contract that changed American history

Just over 250 years have passed since the signing of the Treaty of Paris on 10 February 1763. To look back at this influential contract and a turning point in the history of the United States, we present an excerpt from one of Oxford’s Pivotal Moments in American History series — Colin G. Calloway’s The Scratch of the Pen: 1763 and the Transformation of North America.

As the roots of the second World War can be found in the Versailles Peace Settlement of 1918, so in the 1763 Peace of Paris can be found the roots of the American Revolution, the Peace of Paris in 1783, and the American national empire that followed. Looking back, the road from victory in 1763 to revolution in 1775 seems clear, and the British government’s missteps and misjudgments with regard to taxing the colonists seem obvious. But Britons, on whichever side of the Atlantic they lived, did not see things so clearly in 1763. They were entering uncharted territory, sometimes literally. Never before had Britons enjoyed such power, imagined such possibilities, or confronted such challenges. The path to revolution was only one of many stories unfolding that year.

At the Peace of Paris in 1763, France handed over to Great Britain all its North American territories east of the Mississippi. It transferred Louisiana to Spain, and Spain transferred Florida to Britain. Twenty years later, at another Peace of Paris, Britain recognized the independence of thirteen former colonies and transferred to the new United States all its territory south of the Great Lakes, north of the Floridas, and east of the Mississippi. It returned Florida to Spain, and the British inhabitants of St. Augustine packed up and left, just as the Spanish inhabitants had done in 1763. In 1783 as in 1763, the ministry that concluded the Peace of Paris was not the same ministry that had conducted the war.

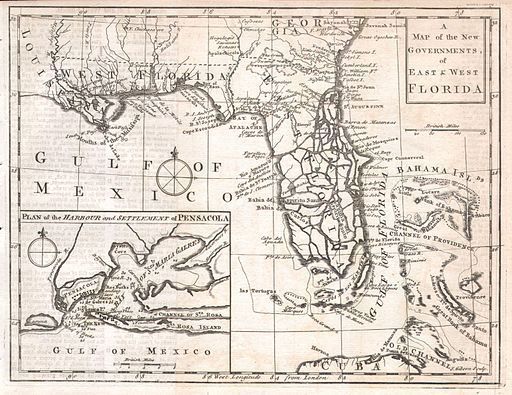

A map of the new governments, of East & West Florida, 1763. Cartographer John Gibson. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

During the debates in England over whether to give up Canada or Guadeloupe at the 1763 peace settlement, William Burke, a relative of the renowned statesman Edmund Burke, had argued that Canada should be left in French hands as a way of binding the North American colonies to Britain: “A neighbor that keeps us in some awe is not always the worst of neighbors,” he explained; removing French Canada would free the original thirteen colonies to separate from the mother country. “By eagerly grasping at extensive territory,” he warned, “we may run the risque, and that perhaps in no very distant period, of losing what we now possess.” As Canadian historian William Eccles pointed out, the Duc de Choiseul not only predicted the American Revolution, but “was counting on it.” For Choiseul, 1763 gave France the peace it needed to rebuild for war. He started rebuilding the navy even before the treaty was signed, and the ink was barely dry before the French were surveying the English coasts to formulate revised invasion plans. France restored its overseas trade, implemented reforms in its army and navy, and strengthened its economy, while at the same time keeping Britain diplomatically isolated in Europe. When, as Choiseul knew they would, the American colonies revolted, France had the power to make the difference. During the War of Independence Britain found itself in the same position France had been during the Seven Years’ War—bogged down in a protracted land war while the enemy took full advantage of its renewed sea power. The British navy momentarily lost command of the seas to France, and Lord Cornwallis lost his army. Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, who had carried the articles of Montreal’s surrender to the British in 1760, was present when the British surrendered at Yorktown in 1781.

Looking back over the course of events from 1763 to 1783, Henry Ellis explained the connection between the two treaties. “What did Britain gain by the most glorious and successful war on which she ever engaged?” he asked. “A height of Glory which excited the Envy of the surrounding nations and united them in the late unnatural contest with our revolted colonies—an extent of empire we were equally unable to maintain, defend or govern—the final independence of those colonies which the dispossession of the French from Canada necessarily tended to promote and accelerate, and the enormous debt of two hundred and fifty millions.” Faced with a huge new territorial empire in North America in 1763, the British tried to defend it, administer it, and finance it. Instead they lost it. They turned to the kind of empire they did best—an ocean-based commercial empire.

France exacted revenge for the humiliation of 1763 but achieved little else. American negotiators signed the preliminary articles of peace with Britain in 1783 without informing the French. France did not replace Britain as America’s trading partner and was unable to shape the direction of American expansion. The French minister, Vergennes, wanted the old Proclamation Line of 1763 to mark the western territorial limits of the new United States, with the lands between the Appalachians and the Mississippi reserved as Indian country. The Earl of Shelburne, now Secretary of State, recognized that American settlements in the West would gravitate to British trade and envisaged joint British participation in the commercial development of the Mississippi Valley. Britain sold out its Indian allies and handed their lands to the United States. “It is rather ironic,” notes William Eccles, “that the British government here insisted on giving away what France had once sought to deny to Britain but now desperately wanted Britain to retain.”

Neither the Peace of 1763 nor the Peace of 1783 made any mention of the Indian peoples who inhabited the territories being transferred. In both cases, Indian interests were sacrificed to imperial agendas. As in 1763, Indians in 1783 were “thunderstruck” by the terms of a treaty that did not include them. As in 1763, they complained that a foreign king had no right to transfer lands and rights they had never given up, let alone breach treaties previously made in solemn council. No such cession could “be binding without their Express Concurrence & Consent.” A Cherokee chief, Little Turkey, said “the peacemakers and our Enemies have talked away our lands at a Rum Drinking.” As in 1763, the victors looked west across vast territories transferred to them in Paris and wondered how to make them into an empire. As in 1763, they believed for a time that they could dispense with the protocols of doing business in Indian country and could dictate to the Indians from a position of strength. As in 1763, they learned their mistake.

Pontiac’s war was not the last Indian war for independence. States and nation encroached on Indian lands and life even more aggressively than had colonies and empire. Multi-tribal coalitions resisted American occupation of the lands ceded by Britain in 1763. During the 1780s and 1790s, and again in the first decade of the nineteenth century, multi-tribal coalitions stalled American advance into the West and mounted formidable opposition to American expansion that sought to gobble up tribal lands piecemeal.

The United States learned from some of Britain’s mistakes. It bound its new territories to it by interest rather than by imperial administration. In the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, the Confederation Congress laid out the provisions by which western territories could enter the union as equal states. In so doing it established a blueprint for perpetual nation-building rather than eventual separation. In Jefferson’s “empire of liberty,” the citizens of the nation shared the fruits of its expansion.

Napoleon Bonaparte had dreams of a revived French empire in America, certainly of a revived French sugar empire in the Caribbean. “I know the full value of Louisiana,” he said, “and I have been desirous of repairing the fault of the French negotiator who abandoned it in 1763.” On October 1, 1800, at the Treaty of San Ildefonso, Spain secretly ceded Louisiana back to France. Thomas Jefferson understood the value of Louisiana too. The threat of an aggressive (rather than a weak) European power having a stranglehold on New Orleans sent a chill down his spine. It looked as if France was to be the United States’ “natural enemy.” But a French Caribbean empire was not viable so long as British sea power remained intact and the slave revolt of Toussaint l’Ouverture remained defiant in Saint Domingue. Napoleon had to defeat them both. He could do neither. Yellow fever decimated his army in Saint Domingue and Horation Nelson destroyed his fleet at Trafalgar. The French emperor needed money to wage war against England. He decided to cut his American losses and unload Louisiana. Louisiana, ceded to Spain in 1763, was French again for less than three years. In the spring of 1803, Robert Livingston and James Monroe, special ministers to Paris, concluded negotiations with Charles Maurice de Talleyrand. For $15 million (80 million francs), the 900,000 square miles of Louisiana became American territory. Passed back and forth like an unwanted stepchild since the Peace of Paris in 1763, Louisiana changed hands one more time in Paris in 1803. The events initiated in 1763 finally played themselves out. The empire in the West would not be French, Spanish, or British; it would be American.

Western lands—those between the Appalachians and the Mississippi that passed from French to British hands in 1763 and then from British to American hands in 1783, and those between the Mississippi and the Rockies that passed from French to Spanish hands in 1763, briefly back to France, and then to the United States in 1803—allowed an empire of slavery as well as an empire of liberty to expand. Should the western territories and the new states formed from them be slave or free? The question proved to be volatile and despite repeated attempts at compromise, defied resolution. The West split the British Empire after 1763. Less than a century later it split the United States. The Revolution severed the relationship between the people who were the citizens of the new nation and peoples who were not continued to contradict the ideals expressed to justify the nation’s birth.

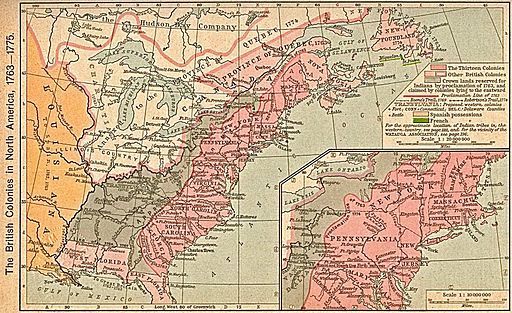

Map of the British colonies in North America, 1763 to 1775. Map from 1923, depicting 1763-1775 by William Robert Sheperd. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Peace of 1763 transferred huge stretches of territory and transformed America. The contest for North American dominance that had raged between France and Britain for close to 100 years was settled once and, with the exception of a brief Napoleonic dream, for all. But the Peace brought little peace and much turmoil to North America. In wrapping up one round of conflicts, it ushered in others. One peace led to another. Territories that had changed hands in Paris in 1763 changed hands again in Paris in 1783. Twenty years later Louisiana changed hands, again in Paris. A new American nation emerged and built a single empire on the lands of numerous Indian nations transferred among three European nations in 1763.

Like King Midas, eighteenth-century Britons perhaps had wished for something too much in America. As happened in 1861, 1914, and 2003, people in 1763 responded to problems whose consequences they could see but not accept by initiating actions whose consequences they could not clearly forsee. In doing so, they set in motion events that changed forever the America they had known.

Colin G. Calloway is Professor of History and Samson Occom Professor of Native American Studies at Dartmouth College. His many books on early American history include The Scratch of a Pen: 1763 and the Transformation of North America; New Worlds for All: Indians, Europeans, and the Remaking of Early America; The American Revolution in Indian Country; and One Vast Winter Count: The Native American West Before Lewis and Clark (2003), which received the Ray Allen Billington Prize, the Merle Curti Award, and many other prizes and was named one of Publishers Weekly’s Best Books of the Year.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 250 years since the contract that changed American history appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRonald Reagan DaySuper Bowl ads and American civil religionThe new DSM-5: changes in the diagnosis of autism and intellectual disability

Related StoriesRonald Reagan DaySuper Bowl ads and American civil religionThe new DSM-5: changes in the diagnosis of autism and intellectual disability

Importance of venue selection in international arbitration

The choice of where an arbitration is venued, known as the seat or the place of arbitration, has important implications and should not be made lightly. The venue of an arbitration impacts the role of local courts in relation to the arbitration, the conduct of the arbitration, and ultimately the enforceability of the award.

Careful selection of the venue of an arbitration is important for several reasons. First, state courts of the selected venue have a role in supervising the arbitration and can influence the process not only before the proceedings have been initiated, but also during the arbitral hearing. The parties, therefore, should pay attention to the local laws and general judicial attitude towards arbitration in the chosen jurisdiction. Second, the seat of arbitration may lead to the imposition of specific rules regarding the conduct of the arbitration, whether relating to the treatment of witnesses or even who may act as counsel or arbitrator. Third, the local laws of the seat of arbitration will be important for the enforcement of the ultimate award or for the applications seeking to annul it. The choice of venue impacts many other issues, including some that may significantly affect cost and convenience. For example, the venue is frequently (although not always) the location where the hearings are held. Thus, it is important to ensure parties and their witnesses have easy physical and legal access to the area.

Prior to the initiation of arbitral proceedings

Local courts of the selected jurisdiction are often called on to provide substantial assistance to the parties even before the arbitration process has been initiated. Although arbitration is largely an extra-judicial process, it is not uncommon that a party brings judicial proceedings seeking preliminary relief, challenging the validity of an arbitration clause or asserting that the particular dispute does not fall within the jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunal and instead should be litigated. Arbitration works most efficiently when courts quickly dismiss challenges to arbitral jurisdiction so long as the contract between the parties contains a valid and enforceable arbitration clause. The courts’ analysis, however, will be based on a variety of factors that vary substantially by jurisdiction. For example, most jurisdictions require that the contract and the arbitration clause be in writing. Yet, neither Stockholm nor Switzerland have such a requirement. The procedure itself for ruling on the jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunal will also be treated differently across venues. While many courts follow the principle that an arbitral tribunal is empowered to rule on its own jurisdiction, this doctrine has been undermined in India by a recent court decision, is not recognized at all in China, and varies according to the wording of the arbitration clause in the United States.

During arbitration

Many parties believe that, once the arbitral process has started, the local courts of the venue no longer have influence over it. That is, however, frequently not the case. The courts can — and do — intervene in the arbitral process. Before selecting a venue, the parties should fully understand the circumstances that may trigger such intervention. One of the most important considerations in this category is the local courts’ position on compelling testimony and evidence. Fact-gathering is critical to successful dispute resolution, yet arbitral tribunals have limited power over third-parties. Thus, parties may need assistance from local courts to secure testimony from third-parties or compel them to produce evidence. The assistance that local courts can provide, however, varies by jurisdiction. For example, a German court cannot compel the production of evidence, while a French court might exercise that power. On the other hand, although courts in Germany and Switzerland can order provisional measures even after arbitral proceedings have started, other courts (for example, in France) have authority to order such measures only before the start of the arbitration.

Post-award stage

Some of the most important effects of the choice of venue are revealed only at the post-award stage. Thus, the grounds for annulment of the arbitral award vary from venue to venue. For example, while most local courts will revoke an award for “violation of public policy,” the interpretation of what constitutes a violation of public policy can vary tremendously between venues. The timeframe during which the parties can demand annulment also varies significantly by jurisdiction. Finally, the parties should remember that the award can be set aside only in local courts of the venue under their local rules and procedures, and the proceedings are conducted in the local language. Thus, the time and cost associated with annulment actions will vary greatly from one venue to another.

With the variety of ways in which local courts can influence the effectiveness and cost of arbitral proceeding, it is important to recognize the importance of venue selection. The parties should always carefully consider their options and discuss them early in their contract negotiations.

Michael Ostrove is the Head of International Arbitration at DLA Piper (Paris). Claudia Salomon is Global co-chair of Latham & Watkins’ International Arbitration practice. Bette Shifman is Vice-President, Director of Publications & Special Counsel at CPR International Institute for Conflict Prevention & Resolution. They are the co-editors of Choice of Venue in International Arbitration, published by Oxford University Press (2014).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: iStockphoto. Do not use without permission.

The post Importance of venue selection in international arbitration appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHomophobia as extremism: The cost to freedom of choiceThe relationship between poverty and everyday violenceUS Supreme Court weighs in on BG Group v. Argentina

Related StoriesHomophobia as extremism: The cost to freedom of choiceThe relationship between poverty and everyday violenceUS Supreme Court weighs in on BG Group v. Argentina

An Oxford Companion to Valentine’s Day

It’s big, it’s red, and it’s here. Valentine’s Day strikes fear into the hearts of men and women around the Western world like nothing else can. But you needn’t run scared of the Hallmark branded teddy bears. Oh no. Follow the sprinkling of rose petals, the sweet aroma of scented candles, and the dulcet tones of Phil Collins up the stairs to the luxury boudoir that is Oxford University Press. Whether you are single or not this Valentine’s Day, let the soothing knowledge in our online products chase your fears away with the following tips…

(1) If food be the food of love, eat on.

It’s a question as old as time: do you eat out for Valentine’s Day or brave the kitchen yourself in a foolhardy attempt to impress your partner? On the one hand, if you dine out, you won’t burn your kitchen down, desperately scraping ashen steak chops off the oven walls as your love weeps into her napkin. On the other hand, you don’t get to use cheesy lines such as: “If the world’s my oyster, then you’re my pearl” as you dish up champagne and oysters. I’m sorry Shakespeare.

However, be careful not to drink your champagne to your oysters on Valentine’s Day as, according to the OED, “to drink to one’s oysters” is to drink to get the worst possible deal. If your partner is a scholar of obsolete English phrases (a very sexy profession) he or she will be most put out.

If you decide to stay at home to cook, possibly inspired by the latest Jamie Oliver or Nigella Lawson recipe, for either two people or one, then our Food: A Very Short Introduction will provide all the information you need to cram before the big day. And if the food doesn’t go as well as you’d hoped, don’t panic, there’s always the wine…

(2) Whisper only the sweetest of sweet nothings.

Tired of the same old cheesy one-liners? If you hear that it must have hurt when you fell from heaven one more time, will you be violently sick? If so, perhaps you should let Oxford Scholarly Editions Online inspire a loftier form of pillow talk. Whether you prefer Donne or Shakespeare, Marlowe or Aston, you could woo your lady the old fashioned way and recite words of romance to her. Warning: this may look odd in a crowded bar. Or maybe you could come up with some lines of your own. “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day” sounds like a good start to a sonnet.

However, if you haven’t met the partner of your dreams quite yet, maybe it’s best to stick to fantasy on Valentine’s Day, and indulge in the 50 shades of Mills and Boon instead of trawling the local bars. Did you know the founders of Mills and Boon (Gerald Mills and Charles Boon) actually began as educational publishers and only moved to romance fiction after the death of Gerald Mills in 1928? If you wanted to delve deeper and expand your knowledge of romantic fiction, the novelist Barbara Cartland wrote a staggering 723 romantic fiction novels in her lifetime. Best grab a bottle of red, pick up a tub of ice-cream, and pour a bubble bath. It’s going to be a long session.

(3) Three is sometimes not the magic number.

Thomas Parr (d.1635), known as ‘Old Parr’, was said to have committed adultery at 105 years, and married for the second time at the spritely age of 122 years. There are also three men on the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography database that had the nickname ‘Cupid’, including the late Prime Minister Henry John Temple. Temple, despite being married, was known as a “man about town” and “a considerable womanizer”. Most women who met him failed to resist his charm. In fact, so proud was he of his own virility that he recorded his sexual successes and failures in his pocket diary.