Oxford University Press's Blog, page 845

February 13, 2014

Books for loved ones on Valentine’s Day

What does your bookshelf say about you? When you work in publishing, you tend to bypass the traditional gifts of chocolate and flowers and aim an arrow straight for the heart — with books. Here are a few staff recommendations on books for the people you love.

“I would give a cook-book like Proper Pub Food by Tom Kerridge to a loved one, as my family and friends all love to eat and recipe books just keep giving. You get the fun half hour after opening when the proud recipient shows the room glossy pictures of delicious looking food saying things like, ‘I’m definitely trying this’, or ‘doesn’t that look like something grandma made’. It also doesn’t hurt to have friends who throw dinner parties using award winning chefs recipes either…”

— Simon Turley, Marketing Assistant for Oxford Journals

“For my first anniversary (traditionally the paper anniversary), I gave my husband a signed book by Kurt Vonnegut. I still love picking up an autographed book as a special present for him. That knowledge that the author him or herself has held that copy in their hand can never be replicated on an e-reader.”

— Patricia Bowers Hudson, Associate Director of Institutional Marketing

“Not only does Mo’ Meta Blues: The World According to Questlove by Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson cover Questlove’s formative years — as well as the formation and evolution of the Roots — but it’s an incredibly rare insight into this corner of the music world. Although the bands that the Roots were the most influenced by — Slum Village, De La Soul, Tribe — faded away around them, they have remained an indissoluble player for decades. Many times throughout this memoir, it feels like Questlove is at the axis of it all. He refers to his life episodes as nostalgia at a short range, and I think he knows that he’s one of the few who hasn’t lost perspective. The chosen title is also kind of perfect because it encapsulates Questlove’s packrat approach to popular culture. Although he has a hilarious fear of photo collages, he finds real peace and satisfaction drawing connections between cultural output to reveal in the obvious in the obscure. Don’t get me wrong: Questlove does not re-appropriate. He is, however, relatable, thoughtful, enthusiastic, stubborn, easily embarrassed, and just downright charming.”

— Cailin Deery, Associate Marketing Manager

“If you are going to give love, give it unconditionally… like The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein. This is not a sad or depressing story. The narrator is omniscient and if (s)he says the tree is happy, then take it to be true, real, genuine, authentic.”

— Purdy, Director of Publicity

“If there is one underrated love-story that everyone should read, it’s E.M. Forster’s A Room With a View, which is high up on my best-books-of-all-time list. Forster’s story of how a passionate young woman finds herself and true love is just about perfect. Plus, it’s filled with great quotes: ‘It isn’t possible to love and to part. You will wish that it was. You can transmute love, ignore it, muddle it, but you can never pull it out of you. I know by experience that the poets are right: love is eternal.’”

— Lauren Hill, Associate Events Manager

“With all of the epics, poems, and stories written about this thing we call love, sometimes it is the least bit of language that is able to communicate the most. Every page of Me without You by Ralph Lazar and Lisa Swerling contains an elementary illustration and short rhyme describing how the protagonist would feel without her significant other. As simple as it sounds, the combined effect would make any Grinch swoon and secretly hope for a visit from cupid.”

— Sarah Hansen, Publicity Assistant

“Any book given with love makes the best of gifts, but for your heart-broken best friend, I recommend Persuasion by Jane Austen. As intelligent and charming as Captain Wentworth is, Anne Elliot’s internal strength goes a lot farther in mending a broken heart. ”

— Alana Podolsky, Associate Publicist

The feast of Saint Valentine is observed on February 14—a day set aside by the Roman Catholic Church to honor two martyred saints: Valentine of Rome and Valentine of Termi.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Books for loved ones on Valentine’s Day appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPerforming for profit: 100 years of music performance rightsLucy in the scientific methodFishing with Izaak Walton

Related StoriesPerforming for profit: 100 years of music performance rightsLucy in the scientific methodFishing with Izaak Walton

Performing for profit: 100 years of music performance rights

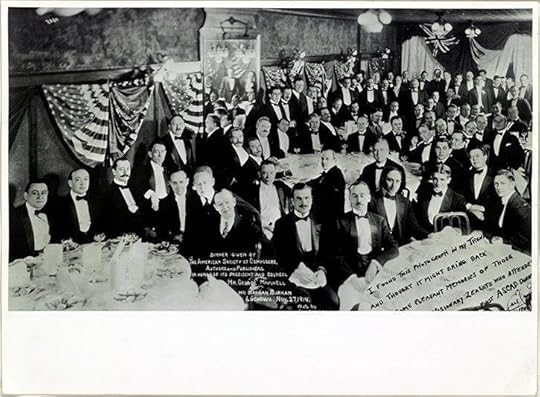

This February marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of ASCAP, the American Society of Composers, Authors & Publishers. Though little known outside the music industry today, its creation set in motion a series of events that still reverberates in the popular music of our time.

The epochal Copyright Act of 1909 gave the owners of copyrights in musical compositions the exclusive right of “public performance for profit.” But the practical challenges of enforcing this right against a multitude of performances, each one “fleeting, ephemeral, and fugitive,” were daunting. In Europe, the problem had been solved through the organization of performing rights societies which pooled numerous copyrights, licensed them to performance venues on a blanket basis, and distributed the royalties in proportion to each piece’s popularity, a model that ASCAP borrowed in its 1914 by-laws.

1914 ASCAP Dinner. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

ASCAP’s efforts to license public performances initially met with massive resistance. But Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, writing in 1917 for a unanimous Supreme Court, ruled that “public performance for profit” was not limited to concerts or shows where music is the main attraction and admission is charged to hear it, but also includes the even more widespread use of ambient music in commercial establishments such as restaurants and hotels—a ruling that was eventually applied to movie theaters and, most important of all, radio broadcasting.

This did not simply raise songwriters’ modest standard of living—it changed the course of popular music. When ASCAP was created, the music business was still dominated by the group of publishers known as Tin Pan Alley. Their profits came from the sale of printed sheet music, and their target consumers were amateur musicians—parlor piano players, barbershop quartets, and the like. They favored simple songs, ones easily learned that required no great skill to perform satisfactorily. “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” of 1908 is perhaps the quintessential Tin Pan Alley tune most frequently heard today. Publishers were long in the habit of paying for professional performances; the idea of collecting a fee for “plugs” was anathema.

With the rise of broadcasting and ASCAP, performance royalties soon surpassed sheet music sales, and songs were being written for the professional, not the amateur. In the 1920s, the Tin Pan Alley era gave way to the days of the Great American Songbook. The best work of ASCAP founders Irving Berlin and Jerome Kern was still to come, and the rising second generation of ASCAP members included the Gershwins, Harold Arlen, Rodgers & Hart, and Cole Porter.

There was a flipside to ASCAP’s success. By the 1930s, membership had become a practical necessity for anyone hoping to have music performed publicly and to collect a royalty for it. “For publishers and composers, to be outside of ASCAP was to be a nonentity in the music business.” ASCAP was able to enforce highly restrictive membership criteria that left entire genres—such as “race,” “hillbilly,” Latin, and gospel music—in the wilderness. And with its stranglehold on the mainstream popular music coming out of Broadway and Hollywood, there was little to restrain the pricing of ASCAP licenses.

The broadcast industry decided to do something about both problems, forming a competing performing rights society—Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI)—that would build an alternative repertoire from the large pool of music blackballed by ASCAP. The broadcasters promised that BMI would “give to American music a freedom for creative progress that it has never had before.”

Although BMI’s early catalogue fell short of that promise, it cobbled together a sufficient number of songs by ASCAP-rejected writers and swing arrangements of public domain tunes to allow the radio networks to pull off a successful boycott of ASCAP music that lasted for most of 1941. BMI was firmly established, and in the post-war years its investment in niche genres began to pay off. “Race” and “hillbilly” music, with the backing of BMI, became the more respectable R&B and country, and when they merged into rock n’ roll, BMI was well-positioned to thrive. Virtually all the iconic early hits of the rock era came from publishing houses affiliated with BMI, and BMI music came to dominate the radio airwaves.

By the 1950s it was the old ASCAP crowd petitioning Congress to break up BMI, charging that rock n’ roll was the product of a conspiracy to foist upon the American public music that broadcasters could procure more cheaply than the old ASCAP standards.

In time the energy behind such futile efforts to put the genie of musical diversity back in the bottle was spent, and the memberships and repertoires of ASCAP and BMI became virtually indistinguishable, each reflecting the broad and widening spectrum of popular music. Music performance rights, virtually impossible to monetize before the advent of ASCAP 100 years ago, are an economic engine sustaining a beleaguered music industry today.

Gary A. Rosen, the author of Unfair to Genius: The Strange and Litigious Career of Ira B. Arnstein, has practiced intellectual property law for more than 25 years. Before entering private practice, he served as a law clerk to federal appellate judge and award-winning legal historian A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr. He lives outside Philadelphia. The Library of Congress will exhibit “ASCAP: One Hundred Years and Beyond” beginning February 13th.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Performing for profit: 100 years of music performance rights appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLucy in the scientific method“Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episodes 2, 3Oxford University Press faces up to the Nazis

Related StoriesLucy in the scientific method“Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episodes 2, 3Oxford University Press faces up to the Nazis

Lucy in the scientific method

Humans seem to love attempting to understand the meaning of songs. Back in my college days, I spent many hours talking with friends about what this or that song must mean. Nowadays, numerous websites are devoted to providing space for fans to dissect and share their interpretations of their favorite songs (e.g. Song Meanings, Song Facts, and Lyric Interpretations). There is even a webpage with a six-step program for understanding a song’s meaning.

As a scientist and a psychologist, I usually find myself rather dissatisfied with the explanations I see on these sites, as well as the ones that my friends and I generated back in my youth. The explanations given often feel too simplistic, as though a single biographical fact could explain the whole scope of a song. They may also be based on an intuitive hunch, rather than good theorizing about why people create what they do. Other times, the interpreter seems to lose all sense of objectivity and instead projects his or her own concerns or issues onto the artist–I know I’ve been guilty of that one! Or the interpreter seems all too willing to accept the artist’s own explanation for the song, when we know from a good deal of psychological research that people are not so good at explaining their own behaviors and motivations.

For the last decade or so, I’ve been trying to avoid these mistakes as I’ve attempted to understand John Lennon’s “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” There are three standard explanations given for the meaning of the song, but each has its problems.

Probably the most popular explanation is that the song is about tripping on the drug LSD. Certainly Lennon did a lot of drugs around the time he wrote this song, and the initials of the song are the same as the drug.

Problem: Lennon always denied that the song was about LSD, even though he admitted other songs (like “Tomorrow Never Knows”) were about the drug. Why would he deny a drug reference in this case but not the others?

Another oft-repeated explanation for the song is that it is about a picture John Lennon’s almost four-year-old son Julian gave him–a picture of Julian’s friend Lucy, floating in the sky with diamonds. All I’ve read suggests that such a moment in time did indeed occur, and there is little doubt that Julian’s picture does look like a girl floating in a diamond-filled sky.

Problem: Why would this picture lead Lennon to write these lyrics, as opposed to some other lyrics? There are no “plasticine porters” or rivers or train stations in Julian’s drawing.

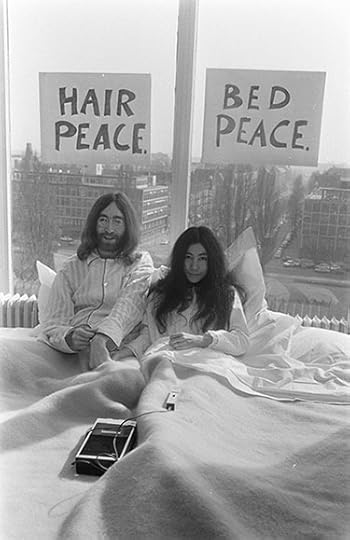

John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Amsterdam, 1969. Nationaal Archief, Den Haag. CC-BY-SA-3.0-nl via Wikimedia Commons.

Lennon’s own explanation, shared a dozen years after he wrote the song, was that it was about his “dream girl” who turned out to be Yoko Ono, even though he hadn’t met her yet. This is certainly a psychologically deeper explanation than any of the others.

Problem: Why did Lennon deny that he knew Yoko at the time he wrote the song when his biography makes it clear they had met months earlier and had even eaten lunch at his house? And if she was his dream girl, why is Lucy constantly “gone” in the song?

Given my dissatisfaction with these explanations and the non-scientific approach to understanding a song’s meaning that is so often used, I set about developing a three step process that I hoped would provide a rigorous, scientifically-based way of understanding “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” (Time will tell how well it works for other songs by other artists.)

Step 1: Derive a full description of the song.

Describing what needs to be studied is the first step any scientist must take when trying to explain any phenomenon. I therefore sought to describe the characteristics of this particular creative expression by adapting four established methods that other researchers had used in the past.

The first method I used was to run a linguistic word count program on the song. I then compared the results from “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” to other songs Lennon had written and other popular songs of the time. This helped me see the style in which Lennon had written the song.

The second method involved conducting a “scripting analysis” of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” and Lennon’s two earliest songs. This helped me to understand whether their narrative structures were similar (which would suggest a theme of long-standing concern for Lennon). I even had another psychologist, naïve to my purposes, derive a script.

An “association analysis” was the third method I used. For this, I mapped out the basic themes likely to have been on Lennon’s mind when he chose the specific words he used in the song’s lyrics. To this end, I reviewed all of his previous songs to see how he had earlier used each of the words that made up “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.”

For the fourth method, I applied a similar method as the third to identify the musical idioms and structures that Lennon used in “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” to identify the previous two songs that were most musically similar to “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”. I thought doing so might tell me what was on Lennon’s mind when he chose the particular melody, key, etc., that he used in “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.”

Thus, by the end of this first step, I had obtained a relatively objective, multi-faceted, and multi-theoretical description of the song Lennon had created in the winter of 1966/1967.

Step 2: Understand the context of the song’s creation.

Why had this man written this song at this time of his life? I read biographies to better understand Lennon’s formative experiences (such as his early life and adolescence), the stresses he had recently been under (such as death threats), the drugs he recently had been taking (LSD), and the “activating event” that spurred this particular creative act (i.e. Julian’s drawing). I then connected these data to relevant psychological and empirical literatures, such as attachment theory, grief research, and what we know about the effects of massive doses of LSD on the mind.

At the end of this step, I had obtained a sense of who Lennon was, what he’d been going through recently, and what spurred him on to this particular creation. At this point I could hazard an explanation of what I thought the song was about.

Step 3: Test my explanation by looking at songs Lennon wrote next.

I decided to test my explanation by examining the songs that Lennon wrote in the three years after “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” I was particularly interested to see whether Lennon continued to express the themes that seemed to have led to the creation of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” when, later in his life, he experienced stresses and situations similar to the ones he had gone through in 1966 and early 1967.

In closing, some might argue that this kind of scientific approach to understanding the meaning of a song is too objective, and too clinical, that it robs artistic creations of their mystery and magic. Other researchers who use the scientific method in the realm of human experience (e.g. religion, life, cosmology) have certainly received similar critiques of their work.

Nonetheless, I continue to hold that if someone really wants to know what a song might mean, there is no better approach than to apply the methods of science in a rigorous, systematic, and theoretically-informed way.

I also have the sense that the understanding that comes from this process does not rob the song of its beauty or meaning. Knowing the science behind sunsets hasn’t made me less awed by their beauty, and understanding what was on Lennon’s mind when he wrote “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” has not made me think any less of the song. Indeed, just the opposite.

Tim Kasser is Professor of Psychology at Knox College. His publications include Lucy in the Mind of Lennon, The High Price of Materialism, and many scientific articles and book chapters. Tim enjoys playing the piano (including blues and Beatles’s songs), interpreting dreams, and spending time with his family at their home in the western Illinois countryside.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Lucy in the scientific method appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEvolutionary psychology: an affront to feminism?Mating intelligence for Valentine’s Day“Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episodes 2, 3

Related StoriesEvolutionary psychology: an affront to feminism?Mating intelligence for Valentine’s Day“Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episodes 2, 3

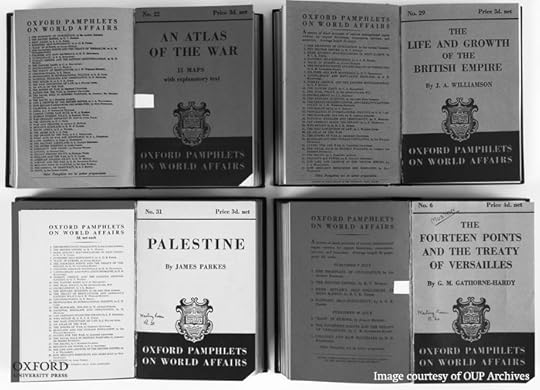

Oxford University Press faces up to the Nazis

Ever since the end of the First World War Oxford University Press had been keen to re-establish some sort of presence in the German book trade. Germany had been a significant market for its academic books in the nineteenth century, and a number of German scholars had edited Greek and Roman texts for the Press. Nevertheless the depressed state of the German economy and the uncertainty of its currency had made this impossible in the first few years after 1918.

However, by 1927 economic conditions were sufficiently improved in Germany for OUP to open an office in Leipzig and appoint H. Bohun Beet, the Press’s representative in Copenhagen, to it, though he still retained responsibility for Copenhagen. Both Humphrey Milford (the Press’s London publisher) and Kenneth Sisam (Assistant Secretary to the Delegates in Oxford) were enthusiastic about Leipzig. The Germans had ‘a very strong local feeling’ but also practised advanced trading methods from which the Press might learn. Additionally, it was the German ‘University professors of English who secure the buying of our solid books’.

Despite that initial optimism, within five years the ‘strong local feeling’ had made the Press’s position in Leipzig untenable. By 1933, Nazi influence on the German publishing system was considerable, and its penetration of the Press’s Leipzig office substantial. That development did bring temporary benefits, as a wry aside from Sisam to Milford made clear: ‘I am returning Beet’s excellent letter. With a group of Nazis depending on him for wages, I think he is safe to get his permits.’ But he wasn’t safe for long. The German book trade organization, the Börsenverein, had been Nazified, and now required every publisher to become a member. Beet took a clear and clean line:

We as an English firm and I as an Englishman have no real right to belong to such organizations, which sooner or later may be antagonistic to us politically, if not today. I have therefore declined to become a member, as I refuse to be Nazified.

. . . I know they want to Nazify the whole earth in due course but I prefer to be left out.

Beet’s heroic stance appealed to Chapman: ‘I have not construed all of Beet’s defiant letter, but I applaud it . . . The blood of all the Bohuns beats in his veins’.

Oxford Pamphlets on World Affairs. From the History of Oxford University Press.

But the pressure continued to increase; Beet reported to Milford: ‘I shall be obliged to become a member [of the Börsenverein] or be sent perhaps to a concentration camp to keep company with other disobedient people and the business would be closed.’ Telephone calls and a face-to-face meeting with a ‘Dr Hess’ — an official whom Beet reported as being a ‘little hopeful’ that a compromise could be reached — followed. By March 1934, Beet was able to report on an arrangement of sorts that kept OUP out of both the Börsenverein and the Riechsschrifttumskammer (an organization for authors, journalists, and publishers involved in producing books in German).

It proved to be a temporary stay, and within a few months Sisam and Milford had agreed on the need to close the Leipzig office. The Delegates authorized Milford to give the necessary notice in order to vacate the premises by the end of 1934. Milford acknowledged that ‘owing to the difficulties in the way of doing business in Germany we have considered it advisable to close down our Branch there for the time being.’ He then expressed a forlorn hope: ‘May we soon see a return to normal conditions!’

Beet stayed on for a couple of years, perhaps sustained by a similar hope, but had given up by the autumn of 1936, when he returned temporarily to Copenhagen. In his final letter from Germany, Beet declared prophetically:

Of course they all want . . . what does yet does not belong to them and that is why the British Empire must be strong enough in arms to keep these military mosquitoes at bay and when will the lethargic British public wake up to their duty as citizens of the Empire. We shall not have so much breathing time as in 1914 that is quite certain.

Simon Eliot is Professor of the History of the Book in the Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London. He is general editor of The History of Oxford University Press, and editor of its Volume II 1780-1896.

With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Read previous blog posts about the history of Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Oxford University Press faces up to the Nazis appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories“Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episodes 2, 3Letters, telegrams, steam, and speedHalf the cost of a book

Related Stories“Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episodes 2, 3Letters, telegrams, steam, and speedHalf the cost of a book

Evolutionary psychology: an affront to feminism?

Getting ready for work the other morning, I was diverted from pouring my coffee by the television news. A comet was about to pass near the sun and might, if it survived, become visible on earth. The professor of astrophysics who had been brought on to explain the details was engaging, enthusiastic, and clear. She was a woman. I wondered how many school girls had heard her and been inspired. Fifty years ago, the idea of a woman gaining recognition in such an arcane area of science would have been astounding. I set off to work with a smile on my face.

If feminism is the belief that nobody should be denied opportunities because of their sex, then feminism belongs to all of us — and that includes evolutionary psychologists. Based on a profound, even wilful, misunderstanding of evolutionary theory, we have been the target of hostility from ‘gender studies’ feminists who have accused us of trying to keep women in their place. Evolutionary theory, they argue, implies an ‘essential’ (read biological) difference between the sexes. Although they cannot deny differences in reproductive organs, they refuse to accept that there are any differences above the pelvis. They maintain this convenient view despite surely realising that testosterone crosses the blood brain barrier, that female foetuses exposed to overdose of this hormone in utero develop male-typical interest, and that neuroimaging studies confirm structural and functional differences in brain organisation in men and women.

Those psychological differences between men and women that have a genetic basis arise from the process of sexual selection: differential reproduction within a sex that means that some genes are copied into more bodies (bodies that survive and go on to reproduce) than others. In ancestral times, any quality that made a woman better at this than other women would have been selected.

Which qualities has ‘sexual selection’ over the millenia given to women?

Recent years have seen a considerable interest in mate competition. A male’s reproductive success (in polygynous sexually reproducing species) depends on how many females he can inseminate. Females tend to be thin on the ground because for a substantial portion of their lives they are pregnant or lactating and therefore unavailable for procreative sex. This ratchets up the level of male competition resulting in some big winners who father dozens (even hundreds) of offspring and losers who are squeezed out completely. Males can become winners by intimidating other males (leading to a wealth of research on male-male aggression) or by charming females. In humans, this had led to a lot of interest in female choice. Why are some men so successful and so desirable to women? We have come a long way since Darwin’s contemporaries refused to take the role of female choice seriously. But we are in the main a monogamous (or serially monogamous) species and this adds a further wrinkle. It creates two-way sexual selection. Women as well as men have to compete for a long-term mate. The rather low criteria that men impose for a casual sexual partner become more demanding when they are making a lifelong commitment. Men (more than women) favour beauty, health, youth, and fidelity and in response women compete to develop and advertise these qualities.

But there are some important qualities on which men and women agree. They want a partner who is kind, understanding, stable, and intelligent. In short, sexual selection for intelligence has been as strong for women as for men. It comes as no surprise therefore that there are no sex differences in intelligence. Of course, there has been a rise in intelligence over evolutionary time since we parted company with our chimpanzee cousins (and that rise has accelerated in the last fifty years) but men and women have risen together. The second string of a woman’s reproductive success lies beyond her choice of partner with the survival and quality of her children. Back in the Pleistocene, this was a demanding job with up to 50% of babies failing to survive to adulthood. Famine, drought, predators, accidents, and illness took their toll. Mothers needed to be clever — at problem-solving, anticipating danger, avoiding toxins, forming alliances, mind reading — to get keep their children alive. At the same time, women’s work of foraging provided half of the calories consumed by them and their children.

Work is not new to women. In our evolutionary past and for most of our more recent history, women (unless they were royals or aristocrats) have worked. And women like men have been selected for their intelligence. Feminism has opened opportunities for women to enjoy and use that intelligence in a public forum. Gender equality liberates women’s abilities and makes them visible to society. What reasonable person would object to that? Certainly not evolutionary psychologists. Encouraging women to achieve their potential does not entail making them the exception to the most powerful theory in the life sciences — the theory of evolution.

Anne Campbell is a Professor of Psychology at Durham University. Her most recent publication is A Mind of Her Own: The evolutionary psychology of women. After completing her D.Phil. on female delinquency at Oxford University, she worked in the United States for eleven years studying girl gang members and violent crime. Since then, she has taken an evolutionary approach to understanding sex differences in aggression, focusing on the psychological mechanisms that mediate behavioural differences between men and women. She has published five books, and won the Distinguished Publication Award from Association for Women in Psychology. She has written over 90 academic articles on topics such as female crime, intimate partner violence, one night stands, competition, gender development, impulsivity, fear, hormonal effects, and mental representations of aggression.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: In the future, the evolution make all women beautiful. By small jaws and beautiful voices. jordens Undergang (La fin du monde) of Flammarion, Camille. Image by Merwart 1911. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Evolutionary psychology: an affront to feminism? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMating intelligence for Valentine’s DayCelebrating Charles Darwin’s birthdaySecond childhood

Related StoriesMating intelligence for Valentine’s DayCelebrating Charles Darwin’s birthdaySecond childhood

Fishing with Izaak Walton

The Compleat Angler opens with a man seeking companionship on a journey. “You are well overtaken, Gentlemen,” Izaak Walton’s alter-ego Piscator (Fisherman) exclaims as he catches up with Venator (Hunter) and Auceps (Falconer) north of London. “I have stretched my legs up Tottenham-hill to overtake you, hoping your business may occasion you towards Ware whither I am going this fine, fresh May morning.” Since it was first published more than three and a half centuries ago, many readers have responded to Walton’s narrative by attempting to follow in the footsteps of Piscator and his friends.

Bridge at Milldale, Staffordshire

At first glance, the task of emulating these seventeenth-century anglers seems both pleasant and simple. Walton’s vacationing Londoners wander appreciatively through beautiful countryside, discuss topics ranging from fishing techniques to the meaning of life, go angling, share favorite poems and songs, and then eat their freshly caught fish — prepared to Piscator’s Top Chef standards — while simultaneously increasing their blood-alcohol levels. But readers’ quests to imitate Piscator — to become, like Venator, a member of the “Brotherhood of the Angle” — have, ironically, created a subgenre of stories of Walton-induced misadventure. In William Chatto’s The Angler’s Souvenir (1835), after days of fruitless attempts to land a trout in increasingly bad weather, a novice angler catches nothing but a cold; confined to his digs and rummaging through his trunk for a book to read, the ailing would-be fisherman “lays his hand on Walton, which, in savage mood, he throws to the other side of the room, wishing the good old man … at a place where it is to be hoped no honest angler ever will be found.” Some American wanna-be Piscators have likewise met with frustration instead of trout. In The Sketch-Book of Geoffrey Crayon (1820), Washington Irving recounts how his narrator, inspired by “the seductive pages of honest Izaak Walton,” utterly fails to re-enact The Compleat Angler in the Hudson River valley: “I hooked myself instead of the fish; tangled my line in every tree; lost my bait; broke my rod; until I gave up the attempt in despair, and passed the day under the trees, reading old Izaak.” And as Nick Redgrove has recently documented, twenty-first-century attempts to emulate Piscator and his disciples are further complicated by the profound environmental changes which have rendered much of the original setting of Walton’s story unrecognizable.

Millions of people in the UK and US go fishing each year, and the experience of angling which Walton celebrates in The Compleat Angler – recreational fishing as the source of enhanced fellowship with both the natural world and humanity — is still successfully pursued on both sides of the Atlantic. The earliest copy-cat sequel to Walton’s narrative appears in the fishing treatise that the Staffordshire squire Charles Cotton wrote to accompany the fifth edition of The Compleat Angler (1676). In this pioneering text (the first angling manual devoted to fly-fishing), Cotton casts himself as “Piscator Junior,” a devoted follower of Walton who meets a Londoner travelling through the Peak District; upon learning that this stranger is none other than Venator, Piscator Junior persuades his new acquaintance to spend some time at Beresford Hall (Cotton’s family seat on the Staffordshire-Derbyshire border) and learn how to fish in Cotton’s beloved River Dove. Today, you can retrace the journey of Piscator Junior and his companion through the rugged terrain of the Peak and marvel at Hanson Toot, a hill so steep that Venator thinks he’s in the Alps, and the bridge at Milldale that’s so narrow “a mouse can hardly go over it.” Beresford Hall is long gone, but the stone fishing house that Cotton built to honor his friendship with Walton still stands, carefully preserved, beside the River Dove, and you can enjoy a pot of tea in this magical little building — the architectural embodiment of Cotton’s love of angling, Dove Dale, and Izaak Walton — while you fish for the descendants of the wily trout pursued centuries ago by Piscator and his self-styled “son.”

Izaak Walton’s Cottage, Shallowford, Staffordshire

Other fans of Walton have enjoyed much more success than Geoffrey Crayon in emulating Piscator on American soil. Inspired by Walton’s depiction of a “Brotherhood” of conservation-minded anglers, a group of Chicago businessmen founded the Izaak Walton League of America in 1922. The first mass-membership conservation organization in the United States, the Izaak Walton League has, since its inception, advocated a keen respect for ecology. When developers planned to drain the watershed of a three-hundred-mile-long stretch of the Upper Mississippi in the early 1920s, the Izaak Walton League successfully pressured the federal government to convert the threatened area into a congressionally financed wildlife preserve instead. Today, with more than 43,000 members in 240 chapters across the United States, the League continues its grassroots efforts to “conserve, restore, and promote the sustainable use and enjoyment of our natural resources, including soil, air, woods, waters, and wildlife.”

The Izaak Walton League of America has now returned to — and helps to sustain — its origins in the English countryside. The only chapter of the League based outside the US was founded in 2002 to help preserve Izaak Walton’s cottage in rural Staffordshire. Walton was born and raised in Stafford, and in the 1650s he bought property near his hometown, including a sixteenth-century cottage at Shallowford. Today, this picturesque thatched, half-timbered cottage, surrounded by a delightful garden of herbs and roses, houses a museum devoted to Walton and the history of angling. The Cottage Chapter of the Izaak Walton League, registered as a charity in both the UK and the US, publishes an award-winning newsletter and works to support and promote the museum. When The Compleat Angler first appeared in 1653, Izaak Walton could not have imagined that he was begetting a global “Brotherhood of the Angle” that would endure into the twenty-first century, but Walton would surely be gratified that in 2014, readers of his book in Britain and beyond continue to find “pleasure or profit” in the story of Piscator.

Marjorie Swann, Associate Professor of English at Southern Methodist University, is the author of Curiosities and Texts: The Culture of Collecting in Early Modern England. She has edited a new edition of The Compleat Angler by Izaak Walton and Charles Cotton for Oxford World’s Classics and is now writing a book about Walton’s Angler and its post-seventeenth-century afterlives.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Both images courtesy of William M. Tsutsui. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post Fishing with Izaak Walton appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesScenes of Ovid’s love stories in art“Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episodes 2, 3Dona nobis pacem by Ralph Vaughan Williams

Related StoriesScenes of Ovid’s love stories in art“Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episodes 2, 3Dona nobis pacem by Ralph Vaughan Williams

February 12, 2014

Mating intelligence for Valentine’s Day

When it comes to the psychology of long-term mating, there are important similarities and differences that characterize the wants and desires of males and females. Based on extensive past research on the nature of human mating, it turns out that the sexes are more similar than portrayals of the recent research in this area often suggests. So in thinking about how to woo your partner this year, you may first want to think about what people across the globe want in long-term mates. To this point, note that men and women often want the same things in mates.

According to the findings of large-scale cross-cultural data, people everywhere seem to want love and someone who loves them genuinely back, putting “your” interests above “his or hers.” Expressions of true love are expressions of altruism, signaling the basic idea of “I’m doing something that is primarily for you at some kind of cost to myself.” So express love — or, perhaps from an evolutionary psychology perspective, more simply express altruism. Give to your partner and do it in a way that shows some self-sacrifice.

When academics think of human evolutionary psychology, they often think of the well-documented literature on the nature of human behavioral sex differences: evolution-based explanations of why men and women behave differently. Granted, research to this point is exhaustive and there is something to it! But human evolutionary psychology is largely about human universals – universals that often cut across gender. The nature of human mating intelligence is in many ways sex-homogeneous as opposed to sex-differentiated.

On this point, consider empathy. Who does not want an empathic romantic partner (or even friend or parent)? The appeal for someone who is sympathetic and kind (high in agreeableness) is one of the most desired qualities in potential mates. Empathy is seen as a positive and desired personality characteristic for cultivating harmonious relationships in several social fields. It is an essential factor that affects interpersonal processes. Empathy is described as the ability to enter one’s world to correctly perceive his/her feelings and their meanings. Research shows that people desire highly agreeable people (as a personality trait which contains empathy) in a potential mate and in long-term relationships more generally. Demonstrating deep and genuine empathy, then, is attractive and should be appreciated by your partner.

Empathy also has a tremendous effect on long term-relationships. Empathic individuals tend to invest their time and energy into their partner and relationship for the long term. Thus, empathy has the power of making a relationship more compatible. It contributes to adult relationships with some positive outcomes such as higher ratings of marital adjustment, better communication, high relationship satisfaction, less conflict, and less depression. Empathy has been noted by many researchers as a key aspect of couple interaction and a predictor of marital satisfaction and functioning. High agreeableness (a significant trait that overlaps with empathy) corresponds to low levels of infidelity, relatively few sexual partners, and high levels of commitment to one’s mate.

A key element of human mating intelligence, then, is true and even conspicuous empathy – including such features as sympathetic emotions in response to others, genuine listening to what others have to say, anticipating the thoughts of another (e.g. cross-sex mind-reading), and knowing the stages that relationships can go through. This Valentine’s Day, if you want to show a little mating intelligence, start by showing a little empathy toward your partner.

According to a recent meta-analysis on the topic of life regrets, it turns out that education, career, and romance are the three most-cited areas in life where regrets arise in the minds of adults. You don’t need to look back years from now and regret your romantic choices of today! According to many findings, we can take several steps to enhance our mating intelligence. Individuals use different strategies consciously or unconsciously, to improve their mating intelligence. Learning about the nature of relationships via modern media (such as music or magazines or movies) may help people learn about the nature of relationships, and what partners may want out of relationships. Taking an empathic approach to the many stories and images we see in the media may actually help people develop some important elements of mating intelligence. And as with other forms of intelligence, such as social intelligence, and emotional intelligence, few individuals seem to reach their maximum limit.

This Valentines’ Day, display some of the core elements of human mating intelligence. Demonstrate love and altruism. Take your time, money, or energy and “spend it” on observable displays of affection to your partner. Be empathic — genuinely listen to what you partner has to say. By doing so, you can make your partner feel loved, validated, and appreciated. Along the way, you’re likely help both you and your partner remember why you started this long-term bond in the first place!

Glenn Geher is Director of Evolutionary Studies at State University of New York at New Paltz. He is the co-author of Mating Intelligence Unleashed: The Role of the Mind in Sex, Dating, and Love with Scott Barry Kaufman, PhD. Gökçe Sancak Aydın is a doctoral student in Psychological Counseling and Guidance Department at Middle East Technical University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Autumn Japanese Couple. © Joey Boylan via iStockphoto.

The post Mating intelligence for Valentine’s Day appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPeak shopping and the decline of traditional retailSecond childhoodCelebrating Charles Darwin’s birthday

Related StoriesPeak shopping and the decline of traditional retailSecond childhoodCelebrating Charles Darwin’s birthday

Genius and etymology: Henry William Fox Talbot

What does it take to be a successful etymologist? Obviously, an ability to put two and two together. But all scholarly work, every deduction needs this ability. The more words and forms one knows, the greater is the chance that the result will be reasonably convincing. Without perseverance and diligence (“indefatigable assiduity”; congratulations to those who, without Googling for this phrase, will know its author) there is little hope to find out the origin of an obscure word. However, hard work, like talent, is another prerequisite of all successful research, for inspiration does not come to the indolent (this phrase is not mine either and is much harder to attribute). To put it differently, the stupid, ignorant, and the lazy needn’t apply. If we go down the list of desirable qualities, including luck and serendipity, we will see that all of them will serve an etymologist well, but none is specific. Apparently, the way of discovery is the same in all branches of knowledge.

However, in one respect pursuit of the best solution in etymology is different from a similar process in biology or physics. People without training in sciences become tongue-tied in the presence of specialists; by contrast, everyone believes to be able to offer an opinion about the derivation of words. When abused, the freedom of speech becomes a dangerous weapon. Outsiders do not know that for approximately two centuries historical linguists have been guided by certain rules. Etymology still presupposes a good deal of guessing, but it tries to be falsifiable, intelligent guessing. Special dictionaries, as well as etymological sections in the OED, Webster, and other reliable reference works, usually give us the information we need and satisfy the public. However, tracing the tortuous ways of our predecessors is also instructive, and that is why I decided to write this post.

In 2012 Cambridge University celebrated the achievements of William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877; he is usually referred to as Henry Fox, or simply, Fox Talbot), the inventor of photography. But the subject of the conference was “Talbot beyond Photography,” because that amazing man contributed learned articles to astronomy, mathematics, botany, the decipherment of Assyrian cuneiform inscriptions, and etymology. Naturally, I can be a cautious judge of only the last-named area of his endeavors. Talbot was educated at Harrow and at Trinity College (Cambridge), and all his teachers marveled at his intelligence. In 1838-1839, he brought out at his own expense the books titled Hermes, Or Classical and Antiquarian Researches and The Antiquity of the Book of Genesis Illustrated by Some New Arguments. Dubious Greek etymologies occupy a prominent place in them. The sales, despite one good review, were unimpressive; eventually, the publisher returned the unsold copies to Talbot’s estate. Both books are rare, and very few libraries own them.

From early childhood on Talbot kept diaries. They are extant, as are his very numerous notebooks. They are kept at the British Library (London), and many researchers have studied them. Experts in art history and the history of photography are well aware of the rich literature devoted to Talbot: books (let alone articles and reports) in English, Italian, French, and German have been written about him. His legacy also interests those who study “the Victorian mind” and the development of science in the nineteenth century. Yet almost nothing has been written about his etymological work, despite the fact that in 1847 Talbot published, again out of pocket, a thick book (one page short of 500), this time called simply English Etymologies, which contained over a thousand entries, most of them short, but some “approaching,” as he said, “to the size of an essay.” The word English in the title should be understood broadly, for many words Talbot discussed are Greek and Latin.

In 1786 Sir William Jones gave a famous talk in which he stated that the affinities among Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, and Gothic could not be due to chance, and postulated the existence of a protolanguage we now call Indo-European (for a long time the usual term was Aryan, but the Nazis made it unpronounceable). He was not the first to arrive at such a conclusion, but it was he whose reconstruction made an impression on the scholarly world. Although Sir William was an Englishman, Indo-European studies struck root first in Denmark (Rasmus Rask) and then in Germany (Jacob Grimm and those who came after him). England had to wait until the late seventies for Henry Sweet and Walter W. Skeat to inaugurate truly modern English comparative linguistics and to catch up with German philological scholarship. In the United States, their peer was William Dwight Whitney.

Talbot’s book is a curiosity. It is a prime example of an extremely gifted amateur believing that one can do etymology without adhering to a strict method. Talbot’s notebooks show how carefully he studied languages. He learned Greek at Cambridge and won the most prestigious prize for his performance. His Latin was excellent. He was well versed in Hebrew. Gothic, Old English, German, Danish, Spanish, French, and Hindustani were among the languages he mastered. Some of them he knew well, because he spent long periods of time on the Continent. But he believed that in order to propose an etymology, it was enough to compare various words, without paying attention to sound correspondences or the history of every word in detail. Noah Webster made the same mistake. Our great dictionaries had not yet been written, but Jacob Grimm was in the same situation as Talbot; yet he never allowed his rich imagination to play tricks like those that ruined Talbot’s experiment. Talbot visualized the most ancient stage of our languages as a plateau on which the ancestors of Greek, Latin, Gothic, Icelandic, and the rest were neighbors; therefore, he allowed Homer to translate a word from Gothic and the Romans to borrow from German. Latin aera “era” was, in his opinion, a variation of English year (or Gothic jer, or German Jahr). He advanced learned and ingenious arguments to boost his idea, but the fact remains that the two words have nothing to do with each other.

Homer, Varro, Isidore, and other authors are quoted on almost every page of the book, along with seventeenth- and eighteenth-century scholars. Talbot derived bran form brown bread, because this derivation made excellent sense. One feels sorry for a fertile mind being wasted on useless hypotheses, some of which Talbot defended with great vigor. He had to defend them, because one of the two reviews of English Etymologies was virulently critical. Unfortunately, neither his supporters nor his attacker saw the real weakness of the book. Students of Talbot are apt to admire the great man (and he deserves their admiration), but specialists “beyond photography” are unimpressed. At best, they accord his publications faint praise. When one deals with a man so dedicated and so brilliant, one is naturally tempted to praise rather than bury him. But in the area of linguistics, his experience shows that etymology, however inexact, is not a collection of entertaining, even if “thought provoking,” fairy tales. It cannot be practiced by dilettantes. The world should allow experts to say silly things and indulge in nonsensical speculation. At the very least such attempts can be refuted rather than ridiculed.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: William Henry Fox Talbot. Daguerrotype by Antoine Claudet, 1844. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Genius and etymology: Henry William Fox Talbot appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBickering and bitchingMonthly gleanings for January 2014Whoa, or “the road we rode”

Related StoriesBickering and bitchingMonthly gleanings for January 2014Whoa, or “the road we rode”

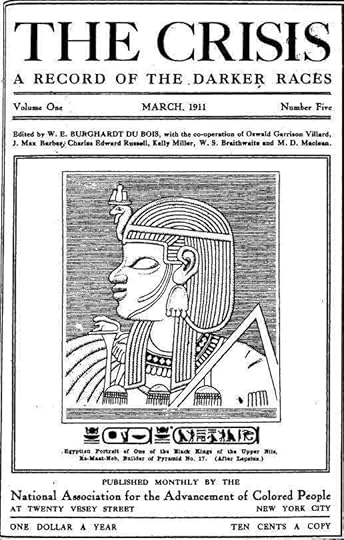

Founding the NAACP

The story of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)’s founding 105 years ago has traditionally focused on the gathering of a small group of whites outraged by the Springfield, Illinois, race riots of the summer of 1908. In January 1909, they gathered in a small New York City apartment to discuss founding a new biracial organization. By February 1909—the date sometimes taken as the official date of the NAACP’s founding—Mary White Ovington, a white social worker who had proposed this meeting, had expanded the group to include two African American clergymen with whom she was working on race issues in New York City.

Mary White Ovington, Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

One of these was Rev. William Henry Brooks, minster of St. Mark’s Methodist Episcopal Church, who sat with Ovington on the Committee to improve the Industrial Conditions of Negros in New York City, which would soon merge with other organizations to become the National Urban League. Another was Rev. Alexander Walters of the AME Zion Church, who headed the National Afro American Council. Ovington regarded these two men as among the most savvy and experienced leaders on racial justice organizing in the city, and she was right. It was these leaders, and many others like them, who brought the experiences and resources to the fledgling NAACP that allowed it to survive the tentative period of its infancy.But the story of the NAACP’s founding is not usually told this way. The traditional story misses the origins of the NAACP in several decades of national organizing by African American activists, in organizations largely forgotten in popular civil rights history today. Those organizations include the National Afro American League, founded by T. Thomas Fortune in the late 1880s; the National Afro American Council, founded by Rev. Walters in 1898; the National Association of Colored Women, founded by Mary Church Terrell and others in 1896; and the Niagara Movement, founded by W.E.B. Du Bois and other so-called “radicals” who broke away from the Afro American Council in 1905.

The true story of the NAACP’s founding emerges from close attention to the many ways in which the NAACP was a direct continuation of decades of prior national organizing, extending back into the 1880s. For example, key leaders, such as Du Bois and Walters, transferred their wisdom gained through decades of prior national racial justice organizing efforts to advise the NAACP on its organizational design. The NAACP’s founding platform blended test case litigation ideas with a left-wing, progressive democratic political ideology.

These were far from new ideas; they framed the organizing vision reflected in T. Thomas Fortune’s founding platform for the National Afro American League, organized several decades earlier. Similarly, the NAACP announced as it key national litigation priority a test case to challenge the constitutionality of the so-called “grandfather clause,” a device inserted in the 1890s into southern states’ constitutions to permanently wipe African Americans off voter registration rolls. This also was not a new idea; a decade before, attacking the grandfather clause had been the litigation priority of the National Afro American Council. The Council’s test case litigation efforts had ended in defeat, although in one case, secretly funded by Booker T. Washington, brilliant US Supreme Court litigation strategist Wilford Smith forced Oliver Wendell Holmes to proclaim that grandfather clauses represented “a great political harm” — but then declare that the high court was powerless to do anything about them in the face of the political power of the states.

By W. E. B. DuBois (Cover of “The Crisis” Magazine, 1911). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Other key resources similarly moved directly from prior national organizations to the NAACP. For example, the magazine Du Bois created and edited for the Niagara Movement, The Horizon, retained its format, tone, content, and even its aesthetics, in becoming the NAACP’s renowned mass circulation publication, The Crisis. Most important of all, experienced grassroots activists who had led the local activities of predecessor organizations, especially (but not exclusively) women leaders active in National Association of Colored Women, and also in the Niagara Movement, transferred their energy and experience to the NAACP to build its early local chapters.

Why did these predecessor organizations and leaders agree to transfer efforts to the NAACP? I believe a big part of this explanation had to do with funding. What white progressives offered to the longstanding organizing efforts of African American leaders was access to philanthropic funds previously been locked under Booker T. Washington’s control. Washington was opposed to open, militant civil rights agitation. Without new allies to break Washington’s control over funding sources, there was no way to push forward this more insistent model of racial justice advocacy, which the members of the Niagara Movement and other civil rights “radicals” embraced. Thus Du Bois wrote an important article in 1909 in The Horizon calling on African American civil rights activists to join in coalition with white progressives from other reform traditions who were calling for a new bi-racial organizing effort on race justice issues. This effort produced the NAACP.

Du Bois made this appeal somewhat reluctantly, I believe, because he recognized the danger to African American leadership of the movement such a step entailed. But he also realized that any sustained, major national organizing effort would need financial resources he had been unable to secure. Thus a great new national organization was born — just not quite the way the standard story tends to tell the tale.

Susan D. Carle teaches courses on anti-discrimination law, labor and employment law, and the legal profession, at American University Washington College of Law. She is the author of Defining the Struggle: National Organizing for Racial Justice, 1880-1915. Like Defining the Struggle on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Founding the NAACP appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories“Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episodes 2, 3A virtual journey in the footsteps of Zebulon Pike250 years since the contract that changed American history

Related Stories“Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episodes 2, 3A virtual journey in the footsteps of Zebulon Pike250 years since the contract that changed American history

“Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episodes 2, 3

As a production, Fleming is still looking great but sounding terrible, with a plonking script mired in Second World War clichés (“This is WAR, Fleming!”).

The second episode begins in 1940. Commander Ian Fleming (Dominic Cooper) is away in neutral Lisbon, where he squanders Naval Intelligence petty cash gambling at cards against uniformed Germans in the casino. Then he goes to the gents’ and rescues a pretty refugee. Her Nazi rapist lies dead on the bathroom floor, garrotted with cheese-wire by a man in evening dress who scuttles out. “Help me! I’m Jewish,” she says. What’s an Old Etonian chap to do? Fleming politely ushers her out, and locks the door on the dead man.

His next adventure is in France, collapsing under blitzkrieg, where he commandeers a Rolls-Royce and confronts the head of the French Navy, Admiral Darlan, warning him not to hand over his ships to the Germans, or else. Then he’s off to help even more refugees escape.

Yet still society ladies in London taunt our hero for being “a chocolate sailor,” stuck behind a desk. Among them is the dark temptress Ann, Lady O’Neill (Lara Pulver), openly conducting an affair with Esmond Rothermere (Pip Torrens), the proprietor of the Daily Mail (“He was wrong about Hitler!”). Fleming is already sleeping with the amiable blonde dispatch-rider Muriel Wright (Annabelle Wallis) but simply can’t commit. He confesses he once was to marry Swiss Monique but his bossy mother made him break it off: “I’ve never forgiven her and I never will,” he adds vehemently. Yes, this Ian Fleming hates his mother, “the wicked witch” Eve Fleming (Lesley Manville), who manages to moralize about others despite having an illegitimate daughter herself.

History always falls mangled under the Panzer-tank of plot. In Fleming, the London Blitz (which actually began in September 1940) comes before the Fall of France (June of the same year). This enables Ann, Lady O’Neill, terrified by an air-raid, to seek solace in Fleming’s bed while unfriendly bombs kill Muriel. Fleming weeps a manly tear over her lovely corpse and seeks comfort from Ann O’Neill. When she mocks his sentimentality, he slaps her face and violates her. But she likes it! They have discovered she is a masochist who enjoys pain and humiliation. Their on-off, game-playing affair runs through the whole series. Lara Pulver — who portrayed a bold Irene Adler in Sherlock — makes a good Ann O’Neill, avid and ardent, perennially unfaithful. You believe she’s the kind of Tory who’d end up as the mistress of the leader of the Labour party, as Ann did in real life later, when married to Fleming.

Ian Fleming (Dominic Cooper) in Fleming (c) BBC America

Episode 3 of Fleming, set in 1942, starts with more fake heroics dreamed up by the scriptwriters. This series embodies the kind of ‘action’ which Joseph Conrad described as “the enemy of thought and the friend of flattering illusions.” Our proto-Bond hero excels on a secret agents’ course at Camp X in Canada and writes a blueprint for a US Central Intelligence Agency (“This is a real page-turner!”). He recruits and trains a private army, 30 Assault Unit, “more vicious and more cutthroat than anyone else.”

Having documented the true story of the brave and often unorthodox men in 30AU, I can state that Fleming’s cartoonish portrayal of them as “rejects, the worst of the worst,” violent and undisciplined candidates for either death or redemption, is a complete travesty. Yes, the real Ian Fleming did have the idea for a commando force run from the Admiralty, but it is a far better and more complex story than the banal version of The Dirty Dozen shown here.

One of the unit’s last survivors died last year, aged 89, a former Royal Marine called Allen ‘Bon’ Royle who had the letters BSc, PhD, CEng after his name. An amusing and eloquent man, he became a mining engineer in Africa after the war, a university lecturer, and a world expert on geostatistics and sampling. He was selected to be an ‘intelligence commando’, not a mindless thug to “wreak havoc and spread fear,” as Fleming suggests. ‘Bon’ could blow safes, but he could also read the documents inside them.

Fleming betrays as little understanding of what intelligence is or does, as it has respect for history. In this dream-world, pompous “Bomber” Harris of the RAF is running the war, trying to sack Admiral Godfrey (Samuel West), Fleming’s boss in Naval Intelligence. Perhaps they have confused him with Winston Churchill, who did run the war and sacked Godfrey for disagreeing with him about claims of U-boat sinkings. But Churchill is too untouchable an icon, so “Bomber” Harris must play the bad daddy, continually running down Ian Fleming’s commandos: “They’re a rogue outfit. They think they have a license to kill!” This is history scripted as a Bond fantasy.

Nicholas Rankin is the author of Ian Fleming’s Commandos: The Story of the Legendary 30 Assault Unit which is publishing in paperback in March. Follow him on Twitter @RankinNick.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post “Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episodes 2, 3 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories“Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episode 1“Before he wrote it, he lived it”?250 years since the contract that changed American history

Related Stories“Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episode 1“Before he wrote it, he lived it”?250 years since the contract that changed American history

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers