Oxford University Press's Blog, page 842

February 21, 2014

The world’s revolutions [infographic]

How many revolutions have occurred in the history of the world? Are they all violent? As revolutions around the world continue to make front page news, we asked Jack Goldstone, author of Revolutions: A Very Short Introduction, to help us pull together a timeline of the revolutions that have shaped the world.

By Jack Goldstone

One of the biggest changes in the history of revolutions is the recent shift from revolutions being mainly violent events, marked by terror and civil war, to being the result of non-violent mass uprisings that force rulers from power and usher in new political systems. Since 1996, these non-violent or “color” revolutions, with death tolls in the dozens or hundreds instead of many thousands (or even far more), have become more common than violent ones.

What determines whether revolutions that start as protests continue and succeed peacefully, or turn bloody? It is mainly the reactions of state rulers, who may take a hint and leave, or decide to ratchet up repression and thus trigger a descent into violence. In Libya and Syria, it was the decisions by Moammar Qaddafi and Bashar al-Assad to turn their troops loose against peaceful protesters that led to the oppositions arming for civil war. Today we are seeing tense confrontations between rulers and peaceful crowds in two capitals: Bangkok (Thailand) and Kiev (Ukraine). Whether these rulers choose to compromise, flee, or fight will determine whether we will add new revolutions to our list, and whether they will go in the column of violent or non-violent ones.

Download a jpg or pdf of the timeline and map.

Jack Goldstone is Virginia E. and John T. Hazel, Jr. Professor of Public Policy and Eminent Scholar, School of Public Policy, at George Mason University. He is the author of Revolutions: A Very Short Introduction and Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World. He blogs on revolutions, the world economy, and international politics at New Population Bomb.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The world’s revolutions [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesNations and liberalism?A crossroads for antisemitism?Fractal shapes and the natural world

Related StoriesNations and liberalism?A crossroads for antisemitism?Fractal shapes and the natural world

February 20, 2014

Common Core Standards, universal pre-K, and educating young readers

Parents and educators everywhere want to introduce children to the world of reading, but the task of helping a child become an independent reader is increasingly difficult and daunting. How can you create a love for reading and learning with stories, lessons, and activities while also supporting reading development? Psychologists, educators, and authors of Book Smart: How to Develop and Support Successful, Motivated Readers, Anne E. Cunningham, PhD, and Jamie Zibulsky, PhD, examine the latest trends in education development and how they affect children’s literacy — navigating through the uncertainties of teaching children to read.

Jamie Zibulsky discusses the benefits that strong reading programs in universal pre-K can produce. Statistics indicate that if children from a low income family are given a strong pre-K education, they show better vocabulary, motivation in learning, and better social skills — mediating the playing field between high income and low income family children.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Anne E. Cunningham emphasizes the importance of a strong preschool and kindergarten experience. More complex texts are now being employed through the Common Core State Standards and they will make learning more difficult.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Anne E. Cunningham and Jamie Zibulsky, psychologists and educators, are the authors of Book Smart:How to Develop and Support Successful, Motivated Readers. Anne E. Cunningham is a Professor of Cognition and Development at University of California Berkeley Graduate School of Education. Jamie Zibulsky is Assistant Professor of Psychology at Fairleigh Dickinson University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only education articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Common Core Standards, universal pre-K, and educating young readers appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBe Book Smart on National Reading DayWhat does he mean by ‘I love you?’Why nobody dreams of being a professor

Related StoriesBe Book Smart on National Reading DayWhat does he mean by ‘I love you?’Why nobody dreams of being a professor

At the launch of Nothing Like a Dame

On Monday, 27 January 2014, the lobby of Oxford University Press’s New York City office was filled with Broadway fans, and a few stars, drinking champagne in celebration of the publication of What price books?

What price books?

For most readers at most times, books were not essential. They were to be bought, if they were to be bought at all, out of disposable income. For most families in the nineteenth century, if they were lucky enough to have any disposable income, it would be a matter of two or three shillings a week at best. This means that book buyers were mostly very price sensitive. We would expect, therefore, the price profile of the Book Trade in general to change markedly as the impact of industrial revolution in print production increased. From work done on book trade prices in the nineteenth century it is clear that this occurred — most notably, judging by data derived from contemporary trade journals — in the 1840s and 1850s, and still further between the 1870s and 1890s. By the mid-nineteenth century this was not simply a matter of producing out-of-copyright works cheaply (although this was still an important part of the market); it was also evident that copyright holders of newish works were working to exploit the possibilities of price elasticity. That is, of finding a new market for the same title by, after a judicious amount of time, offering a radically cheaper version of the same copyright text. Although this was not a market in which Oxford University Press competed, the publication of novels gives a most vivid example of this process. By the 1880s a three-volume novel, originally issued at the very high price of 31s6d (more than the average industrial weekly wage) and aimed at the circulating library market, might be republished as a single-volume novel six months later at 3s6d, then as a railway novel or ‘yellowback’ at between 1s and 2s and then, if demand justified it, as a 6d paperback.

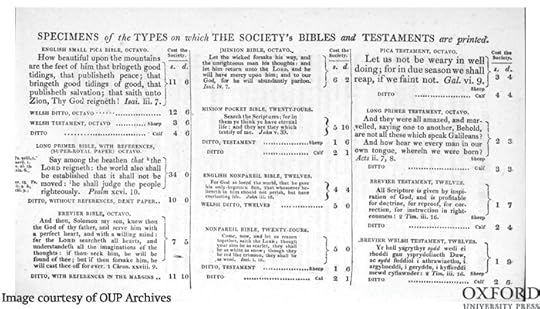

Variety of typefaces and sizes used in BFBS bibles and new testaments ‘Reports of the British and Foreign Bible Society; with Extracts of Correspondence’, fifth volume for the years 1818 and 1819 (By kind permission of Cambridge University Library, 215 x 130 mm).

In practice Oxford University Press, though in a very particular and untypical market, had been exploiting price elasticity for decades, indeed it had been obliged to do so. In order fully to exercise its right to print Bible the Press needed to sell a variety of different texts in different combinations at different prices to different markets. Whole Bibles, New Testaments, Psalms, the Apocrypha, the Book of Common Prayer, Services, and Catechism could be sold separately or bound in various combinations and at various prices. This ‘modular’ approach was visible in the Bible Press’s offerings from at least the 1780s onwards. In the Press’s warehouse in 1801, for instance, there were 79 printed items listed ranging from a Royal Folio Bible (422 copies valued at £1,329.44), through Common Prayer Pica (6,846 copies valued at £782.4), to a 32mo Psalms (498 copies valued at £14.25). Even when a new bible copyright could be exploited for the first time, the Press was not inclined to wait to ‘tranche down’, but offered the same text at different prices from the very beginning. In May 1881 Henry Frowde was promising that ‘on or about 17 May’ the Revised Version New Testament would be available in five formats ranging from Pica Royal 8vo down to Nonpareil 32mo and in four binding styles. The most expensive was the Pica Royal 8vo in morocco at 25s, the cheapest Nonpareil 32mo in a cloth binding at just 1s.

In the market for secular books, as in the market for bibles, not all prices were equally popular, and some possible prices were rarely if ever used. Taking the book trade as a whole during the nineteenth century, prices such as 2s6d, 3s6d, 5s, 6s, 7s6d, 10s6d, and 21s were common throughout the period. From the 1830s onwards the percentage of titles at higher prices (above 10s6d) diminished rapidly while, by 1853, no fewer than seven lower prices (6d, 1s, 1s6d, 2s, 2s6d, 3s, 3s6d) were each accounting for at least 3% of the total titles listed in the main book trade journal. 6d became much more popular in the second half of the century, while 31s6d occurred more commonly than one might expect as it was the price of a three-decker novel; with the collapse of this form in 1894, the first edition of a novel fell to 6s. In other words, the book trade’s price profile shifted decidedly towards cheaper books as the century progressed, with reprints of all sorts commonly selling at various points between 6d and 3s6d. What was seriously under-represented in these figures were the very low prices of texts produced for the literate and semi-literate agricultural and industrial working classes, a market that usually went unrecorded in the respectable catalogues and trade journals of the period. Traditionally this marketed catered for those who might be able and willing to afford something between a halfpenny and twopence. At those prices, print-runs and subsequent sales had to be very large in order to make a reasonable profit. However, by the end of the nineteenth century Oxford University Press was engaging in such markets by publishing one or two books of the Bible retailing at 1d.

Simon Eliot is Professor of the History of the Book in the Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London. He is general editor of The History of Oxford University Press, and editor of its Volume II 1780-1896.

Editor’s notes: (1) Currency: The United Kingdom decimalized its currency in 1971. Prior to that the currency operated on a system pounds, shillings, and pence (and crowns, halfpennies, and farthings). There were 12 pence in a shilling and 20 shillings in a pound. Pounds were abbreviated as ‘£’; shillings as ‘s’; pence as ‘d’. For example, the ’31s6d’ cited in the first paragraph = thirty-one shillings, six pence. (2) Publishing formats: ’8vo’ is an octavo, page size resulting from folding each printed sheet into eight leaves (sixteen pages). ’32mo’ is a thirty-twomo, page size resulting from folding each sheet into thirty-two leaves.

With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Read previous blog posts about the history of Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What price books? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHalf the cost of a bookOxford University Press faces up to the NazisLetters, telegrams, steam, and speed

Related StoriesHalf the cost of a bookOxford University Press faces up to the NazisLetters, telegrams, steam, and speed

What does he mean by ‘I love you?’

Have you ever had difficulty expressing your emotions in words? Have people misinterpreted what you feel even if you name it? If you speak more than one language, you’re almost certain to have answered “yes”.

I am Spanish. My husband is American. The first time I realized emotion words may not mean the same in different languages was when he first told me “I love you”. I liked it, but I didn’t know what he meant. After all, people in English also say they love ice-cream, or biking. Certainly, context (and the look in my husband’s eyes) helped me understand I was more cherished than his two-wheeled vehicle. But in Spanish we don’t use the same verb to designate what we enjoy and what we love romantically, so did “I love you” mean the same as “te quiero”?

This is the kind of question I investigate in my job. I am a linguist at the Swiss Center for Affective Sciences, an interdisciplinary research center at the University of Geneva devoted to the study of emotion. In my specific line of work, we look at the meaning of emotion words, like “love” or “pride”, across languages and cultures. Our project, called “GRID”, brings together linguists and psychologists from 34 countries around the world interested in a topic both psychologists and linguists often have heated debates about: to what extent emotions are the same or different across languages and cultures.

To answer this question empirically, we use a questionnaire and ask people around the world about the meaning of their emotion words. Questions are made about the various “components of emotion”, that is, the basic aspects of experience commonly believed to compose an emotional episode. These include, among others, the way we perceive events around us (was this intentional? is it controllable?), the way our body reacts (e.g. increased heart rate, shivers, blushing), or the way we express our feelings (e.g. frowning, smiling, crying). The responses allow us to compose a mean semantic profile for those words that we can then compare across languages and countries. So far we have investigated the meaning of 24 emotion terms in 23 languages and 27 countries.

Some big commonalities can be found. For example, around the world, our emotional vocabularies seem to be organized in terms of four basic dimensions: words can vary on whether they are more or less positive or negative (like love and hate, respectively), active or inactive (like joy and sadness), strong or weak (like anger and fear), and expected or unexpected (like contentment and surprise). The high correlation scores obtained across data samples also suggest that the meaning of these words is fairly similar across languages. Importantly, this applies to the so-called basic emotions – like fear or anger – which have been hypothesized to be biologically primary and universal, but also to the social emotions – like shame or guilt – which were assumed to vary more from culture to culture.

In addition to the regularities, differences can also be found between languages. For example, Spanish “despair” (“desesperación”) designates a more excited emotion than English “despair”. The latter means, for instance, that when I say I feel “despair”, I may be clenching my teeth and pulling my hair out. By contrast, when my husband says he feels “despair”, he is more likely to have bowed his head and covered his face with his hands.

Interestingly, differences can also be found between countries that speak the same language. For example, the meaning of French “serenité” (serenity) seems to be more positive in Canada than Gabon, and indeed the facial expression of “serenité” in Canada has been found to include a smile, whereas in the African country, “serenity” has more of a neutral face.

More surprisingly perhaps, differences can also be found within the same country. The meaning of “orgoglio” (pride) seems to be slightly different in the North and the South of Italy. In the North, for example, one typically feels “orgoglio” about the things one has done oneself, whereas in the South it can also be felt about things done by others, like one’s kin.

Research at the intersection of language, culture and emotion can shed light on important topics like the cultural traits that influence our emotional representations, and the role of linguistic categories in the emergent quality of emotional experience. The project also has applications for the study of bilingualism (how do our emotion concepts change when we speak more than one language?), emotional intelligence (how does our linguistic knowledge of emotions affect our empathic and adaptive skills?), and pathologies (is the meaning of emotion words different in autistic people with no linguistic deficit but affective handicaps?).

The research agenda is highly motivating because it has applications in real life. A better understanding of the meaning of emotion words is useful to make sense of our emotions and the emotions of others in different languages and contexts, and this is of crucial importance in an increasingly multilingual and interconnected world.

Cristina Soriano is a senior researcher in linguistics at the Swiss Center for Affective Sciences of the University of Geneva, Switzerland. She conducts research on the meaning of emotion words across languages and cultures and on the metaphorical representation of emotion concepts. The first results have been recently published by Oxford in the book Components of Emotional Meaning.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A loving young couple out on date at a restaurant. © GlobalStock via iStockphoto.

The post What does he mean by ‘I love you?’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow the Humanities changed the worldThinking about the mind: an anti-linguistic turnBeggars, buggers, and bigots, part 1

Related StoriesHow the Humanities changed the worldThinking about the mind: an anti-linguistic turnBeggars, buggers, and bigots, part 1

Can metaphors make better laws?

Lawyers have a lot of explaining to do. It’s the nature of their job, as their most important task is to communicate, clearly and concisely, the content of the law. It should therefore be no surprise to find that many of the most masterful users of language, from Cicero to Clinton, from Lincoln to Lenin, were lawyers. When Barack Obama eulogised Nelson Mandela for having “taught us the power of ideas; the importance of reason and arguments”, one lawyer was paying tribute to another.

A good lawyer, like a good writer, is one who chooses her words carefully. Those words are used not only to spell out specific rules, such as those passed by Parliament, but also to capture the underlying principles that support so much of our legal structure. Those principles are particularly important in English law, and in the legal systems based, in whole or part, on our “common law”. Such systems apply, for example, in all but one of the United States, and they govern the rights of around one third of the world’s population. The distinctive feature of the common law is that many of our most important rights and duties derive not from legislation, but from precedent: from the past decisions of the courts. So in English law, if you want to know whether you have committed murder, broken a contract, or received a gift, you don’t start by looking at a statute, or interpreting a code – instead, you have to look at the principles laid down by the judges.

A good lawyer, like a good writer, is one who chooses her words carefully. Those words are used not only to spell out specific rules, such as those passed by Parliament, but also to capture the underlying principles that support so much of our legal structure. Those principles are particularly important in English law, and in the legal systems based, in whole or part, on our “common law”. Such systems apply, for example, in all but one of the United States, and they govern the rights of around one third of the world’s population. The distinctive feature of the common law is that many of our most important rights and duties derive not from legislation, but from precedent: from the past decisions of the courts. So in English law, if you want to know whether you have committed murder, broken a contract, or received a gift, you don’t start by looking at a statute, or interpreting a code – instead, you have to look at the principles laid down by the judges.

The common law’s principles have been developed over hundreds of years, and in hundreds of thousands of judgments. They are applied by judges to the wildly diverse situations thrown up by litigation and are thus subject to the rigorous testing that only real life can provide. Just as scientific hypotheses are eliminated and improved through experiment, common law principles have been abandoned and altered through application. The law thus adapts and survives; it “works itself pure”. But the sheer weight of history causes a problem. How can we explain the law clearly when its general principles have to be extracted from a mass of single instances?

Metaphors can assist: an apt and arresting visual image can get us to the heart of a concept. But caution is needed when handling metaphors. Pick the right one and it will be illuminating and memorable; get it wrong and the squib will be damp; get it badly wrong, and it will blow up in your face. For a writer, such an error will be embarrassing; for a judge, the consequences can be far worse. A misleading metaphor, or one applied too literally, can cause a litigant to be denied his rights. For example, in looking recently at the archaically-named doctrine of “proprietary estoppel”, I’ve found that the application of the relevant principles has been hampered by judges taking too literally the word “estoppel” (a metaphor based on the image of stopping up, or placing a bung in, a bottle). The metaphor does neatly capture one strand of the doctrine, but it fails miserably to explain much of the modern law, which the judges have developed rapidly in order to provide much-needed protection to parties who have reasonably relied on a promise. As Orwell noted, communication is impossible when we use metaphors that “have been twisted out of their original meaning without [our] even being aware of that fact.”

This does not mean, of course, that lawyers, any more than writers, should show metaphors the door. Indeed, an estoppel case shows the power of the well-chosen metaphor. In one of his final contributions as a judge of the UK’s top court, Lord Hoffmann, channelling his inner German philosopher, stated that: “The owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of the dusk.” The image, at once crepuscular and illuminating, was used to capture the idea that, in determining if an oral promise had been made, it was permissible for a judge to consider not only the particular words used, but also events occurring after the alleged promise. The metaphor can also be understood more broadly, as it extends to the idea that, in this branch of estoppel, the question is not whether a promise is immediately binding, like a contract; it is rather whether, taking into account the other party’s reliance on the promise, and other relevant subsequent events, it would now be unconscionable for the promisor to deny any liability to the relying party. And, more broadly still, Minerva’s owl can tell us something about the very nature of the common law: it will continue to develop, and be refined, and we will always need lawyers and judges to explain it. We can only hope that our lawyers and judges, like our metaphors, are chosen wisely.

Ben McFarlane is Professor of Law at University College London. He is the author of The Law of Proprietary Estoppel and is one of the authors of Land Law: Text, Cases, and Materials.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Lawyer and jurors. By junial, via iStockphoto.

The post Can metaphors make better laws? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBeggars, buggers, and bigots, part 1Is small farm led development still a relevant strategy?How the Humanities changed the world

Related StoriesBeggars, buggers, and bigots, part 1Is small farm led development still a relevant strategy?How the Humanities changed the world

February 19, 2014

Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 1

Bigot will wait until the end of this miniseries, because some time ago (26 October 2011) I published a special post on this word and now have only a short remark to add to it. But beggars and buggers cry out for recognition and should not be denied it.

The story of beg and beggar is full of dramatic moments. Both words surfaced at the same time (the mid-twenties of the thirteenth century), but no one knows which “begat” which. If it was the verb, one wonders why beggar was not spelled begger in the first place; beggar is the oldest (and the modern) form of the noun. Begger had great currency in the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries, but this variant must have been due to the belief that beggar originated as an agent noun; thus, a product of folk etymology. Assuming that beggar preceded beg, the verb will end up as an example of so-called back formation, like peddle from peddler or sculpt from sculptor.

The attempt to trace beg to German begehren “to desire, covet” was given up quite early, for be- in begehren is an unstressed prefix. The first volume of the OED (the letters A and B) appeared in 1884. By that time James Murray had already known all the hypotheses that reference books occasionally recycle today. And so did Skeat, whose etymological dictionary of English appeared in 1882. The oldest and quite reasonable conjecture on the origin of beggar goes back to Stephen Skinner. I constantly refer to his 1671 dictionary, for he and Franciscus Junius, the author of a later English etymological dictionary and an outstanding philologist, were very smart men and had numerous excellent ideas. Skinner suggested that beggars got their name from carrying bags. “It must be borne in mind that the bag was a universal characteristic of the beggar, at a time when all his alms were given in kind, and a beggar is hardly ever introduced in our older writers without mention being made of his bag”; so Hensleigh Wedgwood, who wrote those lines in 1872. Eduard Mueller, a reliable but almost forgotten German etymologist of English, followed Wedgwood, the main British specialist in the area before Skeat. Yet theirs is a hopeless etymology. Beggars were never called baggers, and the change of a to e cannot be explained. However, no word exists in isolation. Once the noun beggar was coined, an association with bag probably arose and may have contributed to its survival. Unfortunately, such hidden processes in the life of words cannot be reconstructed. In any case, Skeat and Murray had every right to dismiss the bag ~ beg connection as untenable.

An important event in the search for the origin of beg occurred in 1871, when Henry Sweet, one of the greatest English scholars ever, brought out his edition of King Alfred’s Pastoral Care. Pope Gregory’s book Cura Pastoralis on the duties of the clergy enjoyed tremendous popularity all over the medieval world. It was written around 590 and translated into English under the guidance or by King Alfred at the end of the ninth century. Sweet’s edition appeared in two volumes and contained the Latin and the Old English text supplemented by a translation into Modern English and notes. Once, and only once, the word bedecige “I beg” turns up there (Chapter 285, line 120). The jubilant Sweet wrote: “I do not doubt… that we have in bedecian [the infinitive] a simple derivative of biddan, which is itself used to express the idea of ‘begging’…. Such a derivative exists in the Gothic bidagwa ‘beggar’. The Old English verb is no doubt the original of our ‘beg’, whose etymology has always been a subject of dispute” (I have left out some technical phonetic details). He also mentioned bedecian in the preface, and indeed, he had no reason to fake humility: discovering the origin of an opaque word is a major feat.

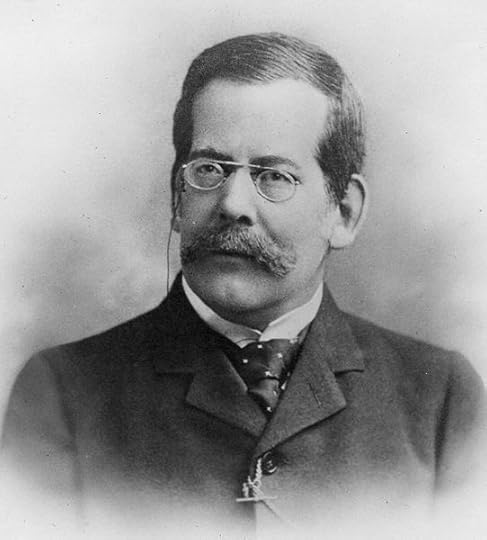

Henry Sweet

Sweet was a man of extraordinary talent, and in his knowledge of Old Germanic and every aspect of linguistics he had few rivals, but even he should not have said I do not doubt and no doubt. In etymology, those words always retaliate. The Gothic noun bidagwa, as though to mock scholars, also occurs only once and seems to be a scribal error for bidaga. (The Gothic Bible is a fourth-century literary monument and the earliest long text we have in Germanic.) Assuming that bidaga is the correct form, it cannot be anything but a cognate of Old Engl. bed-eci-an, in which, contrary to German be-gehren, be- is part of the root bed-. Both seem to be related to Engl. bid, as Sweet suggested. Close to bidaga is German Bettler “beggar,” apparently, but not certainly, another cognate of bidaga.

All this is fine, yet it does not follow that bedecian is the etymon of beg, because the consonants given above in bold do not match. Murray treated Sweet’s idea with utmost respect (neither he nor the OED online indicated where Sweet offered his reconstruction, and that is why I gave the reference). Yet he wondered why between Alfred’s time and the twelve-forties the verb in question never turned up in texts. Later it was shown that bedecian did occur in post-Alfredian Old English; nevertheless, a rather wide chronological gap remained. Skeat initially accepted Sweet’s derivation, and so did, without enthusiasm, Henry Cecil Wyld in his Universal Dictionary. Although the editors of The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology rarely disagreed with Murray, they too hesitatingly preferred it to all others.

I am severely tempted to say that beg “undoubtedly” cannot be traced to bedecian but will refrain from doing so and only state my objections. (Oh, the joys of the rhetorical figure of praeteritio, that is, mentioning something by pretending to omit it!) The main of them is the same as Murray’s. After the publication of the AB volume of the OED, scholars narrowed the chronological gap between bedecian and beg, but it is still uncomfortably wide. Middle English absorbed countless borrowed words. It is a bit too bold to assume that a rare Old English verb lay dormant for at least two hundred years, to reemerge in a slightly different form in the thirteenth century. Mendicancy was such a widespread phenomenon that the verb for “beg” and the noun for “beggar” must have been very common. The postulated phonetic change from d to g, even though not unique, has nearly no analogs. Finally, in the European languages, the story of beg versus beggar usually starts with the noun; the verb is derived from it later. Even German Bettler may have preceded the verb betteln. In similar fashion, we should not be surprised if beggar came before beg, a back formation on it.

Where are we, with German begehren, Modern Engl. bag, and seemingly Old Engl. bedecian out of the picture? Some people thought that beggar is a genteel alteration of bugger (but where did bugger come from?). And why is bigot mentioned in the title? Still others proposed an entirely different solution. The tunnel is long and narrow, but at the end of it I believe I can see a glimmer of light. However, as has happened in the past, our readers will be held in suspense for two weeks, because next time I will go gleaning on the snow-covered February fields. March is warmer, and even bigots, let alone other b-people, will thaw out.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Henry Sweet. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGenius and etymology: Henry William Fox TalbotBickering and bitchingMonthly gleanings for January 2014

Related StoriesGenius and etymology: Henry William Fox TalbotBickering and bitchingMonthly gleanings for January 2014

A new concept of medical textbook

As Charles Darwin elegantly demonstrated, survival depends on the ability for adaptation. This principle, however, can be conceptualized beyond species evolution. By reference to contingent or contextual considerations, adaptation is also relevant to the need of human activity, in general, to correlate with the speed of scientific progress and technological innovation.

This is particularly true for medicine. Although both a science and an art since the days of Hippocrates, the recent explosive expansion of knowledge and technological progress argues in favour of science. Numerous randomized clinical trials, new tools and applied innovation, novel drugs and therapeutic schemes, and updated practice guidelines by major professional societies continually appear, almost on a daily basis, and rationalize our practices. This amazing progress, however, imposes a new set of challenges for the practicing physician who struggles to stay informed and provide evidence-based medicine amidst the current environment of rapidly disseminating scientific knowledge. In addition, classic medical textbooks, as excellent they are, when they appear in print may already be obsolete at parts. Thus, most of the time physicians go through their phones, iPads, or laptops in search of relevant clinical trials, scientific reviews, and guidelines from learned societies.

Even electronic access, however, is not as straightforward as one may hope; information is often not easy to retrieve and, by its nature, when retrieved is often complex and occasionally conflicting, as is the case with results of clinical trials. Guidelines are not always readily accessible, and overlapping guidelines often appear advising different practice regarding the same condition. And when updates do inevitably appear, the situation is compounded.

Thus, there still remains a need for a textbook that organizes our essential knowledge as it disseminates into the medical mainstream. Simultaneously, there is a need for expert opinion to guide the busy physician to the appropriate areas of our evidence-base with advice on how to incorporate it into practice. But, in order to avoid obsolescence, it has to be capable of continuous updating with no time restrictions: immediately as new information appears it should be incorporated into the online version that is now an invariable companion of most scientific publications.

Such an attempt has been recently put into trial with the publication of Clinical Cardiology: Current Practice Guidelines. There were three goals we tried to accomplish with this manual. First to consolidate our knowledge of clinically necessary points and information, to be organized in a “user-friendly, at a glance” way, providing a clinical tool both to our readers and us. Second, to scrutinize, summarize, and present in succinct and clear tabulations the most recent guidelines in the field of cardiology, such as those by the American College of Cardiology Foundation / American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), among many others. Third, and more importantly, to commit ourselves to continuously update our book as new information disseminates. This is now accomplished by biannual online updates and frequent revised versions of the book in the printed form. We are confident that, in the future, an innovative and visionary publishing house as OUP will allow us a continuous access to an online version that can be revised any time by the authors, as happens with a personal website or blog.

We hope that, in authoring this book, the busy physician will have the entire essential and, according to the authors at least, necessary information for his clinical practice available at the click of a button or the turn of a page. As happens with any novelty and revolutionary approach in life, practical and financial considerations and obstacles have always to be addressed and resolved — we hope to evolve through these. The 1860 evolution debate took place at the University of Oxford after all.

Demosthenes G. Katritsis, MD, PhD (London), FRCP, is Director of Cardiology at Athens Euroclinic, Greece, and Visiting Professor at the City University, London, UK. He is co-author of Clinical Cardiology: Current Practice Guidelines.

Oxford Medicine Online is an interconnected collection of over 500 online medical resources which cover every stage in a medical career. Our aim is to ensure that the site delivers the highest quality Oxford content whilst meeting the requirements of the busy student, doctor, or health professional working in a digital world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: My stethoscope by Darnyi Zsóka. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A new concept of medical textbook appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow we all kill whalesWho shapes the history of the British Isles?Madness, rationality, and epistemic innocence

Related StoriesHow we all kill whalesWho shapes the history of the British Isles?Madness, rationality, and epistemic innocence

‘Before he lived it, he wrote it’? Final thoughts on Fleming

The real Ian Fleming died on 12 August 1964, just two weeks before the release of the second Bond film, From Russia With Love. Ian’s thrillers, and the films based on them, were already rising towards their phenomenal worldwide success, although they were still sniffed at by the snootier members of his wife Ann’s circle. The following year, when the novelist and critic Kingsley Amis published his zestful literary appreciation of Fleming’s writing, The James Bond Dossier, Evelyn Waugh remarked to Nancy Mitford: ‘Ian Fleming is being posthumously canonized by the intelligentsia. Very rum.’

Production still from Fleming: The Man Who Would Be Bond, (c) BBC America

Fifty years on, the Fleming icon is being desecrated on television. As a biopic, the fourth and final episode of Fleming is preposterous. It’s early 1945. Boyish Ian Fleming (Dominic Cooper) demonstrates some Q-style gadgets — a poison-gas pen and a cigarette-lighter camera whose film fits in a golf ball — to the cigar-chomping American Colonel William Donovan (Stanley Townsend) and says they will win the war. Donovan dismisses his toys because he’s after bigger fish: Hitler’s atomic bomb program! Where are the ‘Nazi nuclear secrets’? Ian Fleming draws four lines of retreat on a map of Germany. They intersect at Tambach Castle! That’s the hiding place, and he must race there before the Americans or the Russians. ‘Leave it to me!’

Taking with him a lone sergeant and a couple of Sten-guns, Fleming drives in a jeep through southern Germany, looking for ‘Nazi documents, nuclear secrets’. The snowy woods are full of last-ditch ‘Werewolves’ with scars on their brutal, stop-at-nothing faces. At the castle, a German admiral is protecting the secret stuff – ‘my life’s work.’ The Werewolves attack; the sergeant holds them off till he dies, actorishly; Fleming murders a Nazi with his bare hands, puts on his uniform and escapes in a truck with the admiral and all the papers. Russian troops stop them; the German admiral is shot, but with one bound (‘I am a British officer!’) Fleming escapes with the precious documents.

This being Fleming, it goes without saying that none of this happened. Or if anything like it did, they get it wrong. In Ian Fleming’s real life in the Second World War, he killed no-one, never fired a submachine gun, invented no gadgets, met no Soviet troops. William Donovan, Director of the Office of Strategic Services, was a Major-General at the time, not a Colonel. The real-life ‘Werewolves’ were mostly a fantasy of Joseph Goebbels, enacted by a few kids. Tambach Castle held nearly 500 tons of the German naval archives (far too big to fit in one small truck) and they were captured intact without any shots being fired.

The true story is completely different. Commander Fleming worked for British Naval Intelligence and he was directing his ‘intelligence commando’ teams towards naval targets, not ‘nuclear secrets’. As well as capturing the archives, Fleming’s commandos, 30 Assault Unit or 30AU, hunted down the first German miniature submarine and seized the hydrogen peroxide technology powering both Nazi rockets and a new generation of U-boats that were faster than anything the Allies had. This is the real background to the later James Bond books like Thunderball and Moonraker. At the Walterwerke in Kiel, 30 Assault Unit uncovered a genuine ‘lethal toyshop with its jet-driven explosive hydrofoils, radio-controlled glider bombs, remote-controlled tankettes, rocket-propelled ‘sticky bombs’, silent steam cannons, mine detonators and a new kind of big gun with a fuel injection system in the barrel to extend its range.’ The TV Fleming is like being trapped with a crassly compulsive liar who can’t tell truth from falsehood, and doesn’t want to try.

Ecosse Films have subjected other famous people to screen dramatization, including Queen Victoria, Jane Austen, and Princess Diana. Now John Brownlow (who scripted a biopic about Sylvia Plath) has sold them this pastiche Fleming, which they have made in Hungary. Does truthfulness matter in entertainment? When Darryl F. Zanuck was criticized for altering some events of D-Day for his 1962 epic movie The Longest Day, the producer’s defense was that: ‘There’s nothing duller on the screen than being accurate but not dramatic.’

Inaccurate Fleming isn’t dramatic, simply unbelievable. The credited consultant is John Pearson, the veteran journalist who knew Ian Fleming and wrote the first biography, The Life of Ian Fleming, in 1966. But John Brownlow seems to have mashed up that shrewd book with the jokier ‘fictional biography’ that Pearson wrote in 1973, James Bond: The Authorized Biography. The mix doesn’t work. Whatever else he may have been, in real life Ian Fleming was literate, amusing, inventive, and intelligent. The television Fleming has reduced his life and work to the puerile silliness of what the authentic spy and traitor Kim Philby once dismissed as ‘James Bond idiocy’.

Nicholas Rankin is the author of Ian Fleming’s Commandos: The Story of the Legendary 30 Assault Unit which is publishing in paperback in March. Follow him on Twitter @RankinNick.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post ‘Before he lived it, he wrote it’? Final thoughts on Fleming appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories“Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episodes 2, 3“Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episode 1“Before he wrote it, he lived it”?

Related Stories“Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episodes 2, 3“Before he lived it, he wrote it”? Fleming Episode 1“Before he wrote it, he lived it”?

Is small farm led development still a relevant strategy?

The case for smallholder development as a win-win strategy for achieving agricultural growth, poverty reduction, and food insecurity is less clear than it was during the green revolution era. The gathering forces of rapid urbanization, a reverse farm size transition towards ever smaller and more diversified farms, and an emerging corporate-driven business agenda in response to higher agricultural and energy prices, is creating a situation where policy makers need to differentiate more sharply between the needs of different types of small farms, and between growth, poverty, and food security goals.

Many smallholdings today are too small to provide adequate livelihoods, and their farm families have either begun a transition out of farming into the nonfarm economy, or they are trapped in subsistence modes of farming. Both kinds of smallholders may need assistance developing new off-farm opportunities, and in overcoming poverty and food insecurity. These smallholders account for large shares of the total rural poor and food insecure people in the developing world, and they are an important target group for international efforts to achieve the MDGs and promote food security. However, transition and subsistence oriented farms play a relatively minor role in producing marketed surpluses to drive economic growth and feed growing urban populations, and are unlikely to successfully link to modern value chains. Interventions to improve on-farm productivity can be helpful to the food security of both groups, but will need to be complemented by other interventions that more directly alleviate poverty and facilitate off-farm transitions.

In contrast, there are also many small farmers who, because of their resource endowments, good location or shear entrepreneurial skill, are succeeding as commercial farm businesses, even if only on a part time basis. These kinds of small farms are much more aligned with the new corporate driven business agenda. As with small farms in green revolution days, they can play important roles in driving economic growth and feeding urban populations. The greatest challenge facing these types of smallholders is accessing modern value chains. Private sector investments along value chains are opening up new market opportunities for some smallholder farms, particularly for high value products, but it is also becoming apparent that many more commercially oriented smallholders are being left behind while larger farms are gaining market shares.

If more smallholder farms are to become commercially successful in farming, policy makers will need to do more to support them. Key areas for support include improving the workings of markets for outputs, inputs, land and financial services to overcome market failures that discriminate against small farms, investing in the kinds of R&D and rural infrastructure that small farmers need, helping to organize small farmers for the market, and incentivizing the private sector to link with more small farmers. The best way to achieve these is for government to work through private sector and civil society partners, creating an enabling policy and business environment, and scaling up proven successes.

An important challenge is the development of practical ways of identifying different groups of small farms on the ground. There has been a lot of recent work using spatial analysis methods to identify target areas for rural development purposes. Most of this work focuses on mapping different regions in terms of their agro-ecology, market access, and rural population density, but so far there has been limited work on disaggregating further according to differences in farmer endowments, market orientation and gender.

Peter Hazell was formerly director of the development strategy and governance division at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) in Washington DC, and a visiting professor at Imperial College London. Atiqur Rahman was formerly a member of the Strategy and Knowledge Management Team of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) in Rome. They have edited New Directions for Smallholder Agriculture.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Women smallholder farmers in Kenya. By McKay Savage [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Is small farm led development still a relevant strategy? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive myths about the gold standardEnhancing transparency at ICSIDPeak shopping and the decline of traditional retail

Related StoriesFive myths about the gold standardEnhancing transparency at ICSIDPeak shopping and the decline of traditional retail

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers