Oxford University Press's Blog, page 504

June 2, 2016

Intuitive bedrock and the philosophical enterprise

Imagine a person who spends their entire life sitting on the couch watching and rewatching Clive Barker’s Hellraiser. He does nothing else, gains no education, no relationships with other people, no family, no friends. But he, nevertheless, loves his life, he values everything about it. He is constantly offered the opportunity to do something different, and never chooses to do so. Indeed, his choices are not the result of a lack of information or imagination — he understands perfectly well what it would like to do something else. But he so loves watching the movie that he is simply unconvinced that any alternative would be better for him.

Is this person leading a good life, at least for his own sake? Many are tempted to say “no”. After all, this life is not at all well-rounded, it maintains no knowledge or genuine appreciation of the beautiful, does not engage rational capacities (beyond, say, the bare minimum required to rewind a VHS tape). But others say “yes”. After all, what more is required for the good life for a person that they value it highly, perhaps under conditions of full information?

It seems we may have reached “intuitive bedrock”. In so many areas of inquiry (though, perhaps, not all), philosophical argument ends up bottoming out in a mere clash of intuitions, of considered judgments. But what happens now? Because these considered judgments will help determine the content and structure of our philosophical theorizing, to determine (once and for all) what the good life is for a person (or whether we should be descriptivists or causal theorists of reference, or whether justified true belief counts as knowledge or not, or — if Lewis Carroll is to be believed — whether modus ponens is a valid rule of inference) we — or so it would appear — need to settle which of these intuitions are the right ones.

To put my cards on the table, this seems like an impossible task. Indeed, it’s a task that seems (almost by definition) outside the bounds of philosophical argument. After all, if philosophical arguments (sometimes) bottom-out in intuitive bedrock — Hellraiser good!; Hellraiser bad! — that’s where the tools of philosophical argument seem most impotent. But if this task is impossible, I wonder whether philosophers really ought to conceive their overall project as one that would require it. After all, we only need to settle which intuitions are the right ones if we are in the business of deciding whether, e.g., objectivism or subjectivism about well-being is true. But there’s an alternative. Rather than seeing ourselves as answering the “big questions”, as it were, we see ourselves as exploring how to construct alternative theories, what such theories must take on board, their relations and interconnections without settling which account of the “big question” is the right one. To borrow a metaphor from Ryle (though to somewhat different effect) we might think of the product of philosophical inquiry as a map or road atlas: a clear account of which routes one might take through logical space, without settling which route is the “right one”. (This need not commit to there being no right answer — just that it’s not the task of philosophical inquiry to determine what it, in fact, is.)

Thinking of philosophy in this way has some benefits, I think. First, it provides a more compelling account of philosophical progress. Take hedonism, for instance. This classic theory of well-being stands no closer to refutation or general acceptance than when it was first introduced. But while we may be no closer to consensus on whether hedonism is true, we have discovered a number of important features of the view (it can be both objective and subjective), differences in how to express it (sensory versus attitudinal), concepts of which hedonism may be an adequate conception (moral hedonism, axiological hedonism, prudential hedonism), important verdicts hedonism may take on board (the experience machine). If this sort of thing is what we’re up to, we’re, as it turns out, pretty good at it.

Second, and to me most important, if we think of the philosophical enterprise in this way, the ultimate task of philosophy becomes fully collaborative. If I’m a welfare subjectivist, the success of the project at which the objectivist is engaged need be no threat to the success of my project. After all, we’re all working together to develop the most complete “atlas”. The fact that, when we reach bedrock, I go subjectivist and you go objectivist need not entail that we are philosophical adversaries.

There may be drawbacks; after all, we might be very interested in whether objectivism or subjectivism is true. Giving up the pursuit of the right answer may be disappointing. But I suggest we kick the tires on an alternative, which seems to me a natural result of reflection on the phenomenon of intuitive bedrock. But even if it isn’t, it is up to philosophers how to understand what they’re up to — indeed, up to each individual philosopher. My hope is that thinking of philosophy as a kind of atlas-drawing means that we’re better at our jobs, we see ourselves as working together, and we approach philosophical inquiry much more often in a constructive and collaborative spirit.

Featured image: Haringvaten2_wallpaper by Remy Remmerswaal. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Intuitive bedrock and the philosophical enterprise appeared first on OUPblog.

And the Nobel Prize goes to…

The Red Cross is the organization to receive the most, with three. Martin Luther King was the youngest – until Malala Yousafzai won at the tender age of 17 that is. Jean-Paul Sartre famously won and refused it. Mother Teresa won it but has since been brutally called out since for her inhumane treatment of the poor. Paul Hermann Müller won it in 1948 for the pesticide DDT, which went on to create one of the worst environmental disasters in history. Gandhi was nominated 5 times but never won, dying a few days after his last nomination and leaving the year 1948 “not awarded because there was no suitable living candidate”. It was suspended during the chaos of the great wars and none were awarded in 1914, 15, 17 and 18 due to WWI or 1939-43 for WWII.

I am talking, of course, about the Nobel Prize.

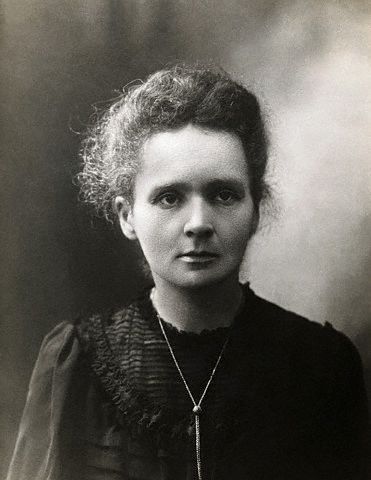

In science, perhaps the most famous recent award is for the prediction of the existence of the Higgs Boson particle, discovered at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider. Overall, the most famous recipient ever is likely Marie Curie. She went down in history as the first person to win two. She took Nobel Prizes in 1903 and 1911 for getting radium and polonium out of pitchblende, with her own elbow power. Both elements are more radioactive than uranium. Shockingly, luminous paints were created with radium and used on clocks, watches, and instrument panels.

Another wildly famous, or more aptly, infamous, Nobel Prize is that for the DNA Double Helix. In 1962, Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Wilkins won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for showing that the two strands of DNA mirror each other to form a helix. The award left out Rosalind Franklin who created the famous “Photo 51” of the crystalline structure of the DNA helix, an image that “changed the world”. As Nobel prizes can’t be given posthumously, she couldn’t win outright, but her colleagues calling her “The Dark Lady” was far from ideal ethical or scientific conduct.

Portrait of Marie Curie, c. 1898, five years before she won his first Nobel Prize. Image © Underwood & Underwood/CORBIS. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Marie Curie, c. 1898, five years before she won his first Nobel Prize. Image © Underwood & Underwood/CORBIS. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Frances Crick sold his medal for US$2.27 million and James Watson for US$4.76 million in 2014. Watson got his medal back from the anonymous buyer. Watson’s Nobel speech and a lecture sold for an additional $610,000. When Crick sold a letter he wrote to his 12 year old son describing the discovery, it sold for $6 million making it the most expensive letter in history.

Both Curie and the Double Helix are secure in most lists of the top Nobel prizes in history. This list also includes a second DNA Nobel. A year after Fleming et al won for isolating the first antibiotic, penicillin, Hermann Muller won in 1946 for discovering the mutating effects of X-ray radiation. For years, radiation would be used to create new types of domesticated crops, for example the deliciously sweet Ruby Red grapefruit through DNA mutagenesis, effectively speeding up evolution and human ability to artificially select beneficial mutations. Penicillin can also be considered a DNA Nobel, as the DNA sequence for this antibiotic has since saved the lives of millions.

DNA has fared well in the Nobel stakes. While DNA research took a while to take off, the second half of the last century saw many wins.

Ochoa and Kornberg (1959) won for synthesizing DNA and RNA, respectively. Holley, Khorana, and Nirenberg (1968) cracked the genetic code, the triplets that signal which amino acid comes next in the chain of a protein. Arbers, Nathans, and Smith (1978) found enzymes in bacteria that chop DNA and fuelled the recombinant DNA revolution. Barbara McClintock (1983) discovered jumping genes in corn, called transposable elements, that, for example, paint corn kernels different colors.

Genomics was launched by the invention of DNA sequencing and the invention of a way of copying DNA in a test tube to make any quantity desired for further study and manipulation. Gilbert, and Sanger (1980, chemistry) won for their methods of DNA sequencing and Mullis (1993, chemistry) for developing the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR).

The Nobel Prize, which is given to individuals who confer “the greatest benefit on mankind”, was established through a bequest from Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel. He left money and directions in his will in 1985 to set up prized for Literature, Physics, Chemistry, Physiology and Medicine and Peace. A prize for economics was later endowed in 1968 by members of the banking community. The first Nobel Peace Prize was awarded in 1901 to Frédéric Passy for founding the Inter-Parliamentary Union and Henry Dunant for setting up the Red Cross.

If the Nobel Prize had been established earlier, one certainly would have be bestowed on the Swiss doctor, Friedrich Miescher, who first discovered DNA in 1869 and to the monk, Gregor Mendel, who established that inheritance comes in units (genes) doing experiments on the heritability of colours in the flowers of sweet peas only two years before.

So what might be the next DNA Nobel Prize?

In 2014, three leaders of the public human genome project from the National Institute of Health (NIH), Collins, Lander and Botstein, received the Albany Prize, also called “America’s Nobel”. Notably missing is Craig Venter who produced the private version of the human genome sequence through his company Celera. Genomic projects are famous for being the work of casts of hundreds to thousands, and therefore less likely to win, but the human genome is certainly a candidate.

The CRISPR gene-editing system is the likeliest bet. In 2015, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier shared the Breakthrough Prize for Life Sciences. Founded in 2013 by the likes of Sergey Brin, Anne Wojcicki, and Mark Zuckerberg and others, it extends the scope of the Noble’s, giving awards in fundamental physics, mathematics, and life sciences.

Looking over the past roster of awards, it is dominated by DNA wins.

Featured image credit: DNA fairy lights, by Stuart Cale. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post And the Nobel Prize goes to… appeared first on OUPblog.

June 1, 2016

I double dog dare you to reject my etymology, or the dog’s chances increase (even if ever so slightly)

The origin of Engl. dog will not look like a uniquely formidable problem if we realize that the names of our best quadruped friend are, from an etymological point of view, impenetrable almost all over the world. The literature on dog is huge, and the conjectures are many. Every next scholar hopes to solve the riddle, but, since articles on the subject keep appearing, I assume that there is still room for improvement. The traditional sources of animal names are known quite well, and I have listed them in my previous posts on tyke, bitch, and cub. Perhaps dog was originally the name of a particular breed and referred to some color (brown?); if so, dog may share its root with dye. Or the word goes back to a call to the animal. Or it meant “runner” or “a useful animal” (supporters of the latter hypothesis compare dog and the family of Engl. doughty). Similar-sounding nouns and verbs are readily available (dodge is especially tempting but should be kept apart from dog: see my old post “Between dodge and kitsch”). Old Icelandic has dugga “a headstrong, intractable person,” and in Old English the personal name Dycga has been recorded. It is anybody’s guess whether one or more of those words should be compared with dog, but even the establishment of a precarious tie will shed no light on the origin of our animal name. Suppose dog is a congener of Dycga or dugga. So what? Old arguments tend to be repeated in later works because they seem to hold out some promise and because until a few years ago a fairly complete bibliography of English etymology did not exist and it was nearly impossible to produce an informed survey of the state of the art.

Speakers of Old English called the dog hund, the progenitor of the modern noun hound, a word, allied, according to many, to Latin canis. In our earliest texts, only the form docgena (the genitive plural) turned up, and only once (in the Boulogne Prudentius Glosses). It was applied contemptuously to the pagan henchmen of the torturer Dacianus by their victim Vincentius and rendered Latin canum. The canum ~ docgena pair makes it almost certain that docgena did indeed mean “of (the) dogs,” and we note with surprise that the word’s pejorative sense surfaced before the regular, neutral one. It had either gained some currency as vulgar slang by the middle of the eleventh century (and was avoided in writing) or the glossator used an animal name current in his dialect but unknown elsewhere (this would be a common case). The glosses in question contain rather many words not attested in earlier texts. In the form docgena, the letters cg should be pronounced as gg, that is, as long g. To the best of our knowledge, the nominative was docga. Frog, stag, (ear)wig, and quite probably pig also ended in –cga in Old English.

Although it has once been suggested that –cga is a remnant of some longer word, the predominant opinion of modern scholars makes better sense: we seem to be dealing with so-called hypocoristic formations, that is, with pet names like pussy and doggie. The word was probably coined late, so that looking for its cognates in Greek and Latin will hardly yield useful results. The idea that that dog has the same root as Greek dákno “I bite” goes back to Minsheu (1617); it recurred two and a half centuries later in a fully respectable work. Yet this is a dead end. The same holds for the alleged parallel Greek thōússō “I shriek; incite dogs by crying out, etc.” ~ Engl. dog. Comparison with dogma is bizarre, to put it mildly. The word dog ousted hound only in Middle English. It became a generic animal name, while hound came to mean predominantly “hunting dog, dog kept for the chase.” Neologisms constantly supersede old words—an analog of the plebeians’ triumph over unwary aristocrats.

August Pott, a great Indo-European scholar, who, though a learned man, did not ignore dogs and their names.

August Pott, a great Indo-European scholar, who, though a learned man, did not ignore dogs and their names.Despite the ever-increasing number of works on the etymology of dog, two statements remain constant: dog is a neologism of unknown origin, and the word has no cognates even in Germanic, for, wherever it appears, it is a borrowing from English. The first statement is correct, but the second may perhaps be modified. In looking at the geography of tyke, bitch, and cub, we observed a multitude of forms spread over a rather large territory. The great German philologist August Pott (1802-1887) enjoyed great renown in his time. His productivity was awe-inspiring, but today few people consult his multivolume compendium and his informative articles. In 1863, he wrote a long linguistic essay on dogs. Among the astounding number of words he cited, he mentioned dodel “dog” (apparently, recorded in a German dialect of Alsace; the reference is unclear), döggel, and teckel from Schleswig, as well as many forms belonging with tyke but having a short vowel. As usual, d varies with t, and g with k in German dialects. Döggel ~ teckel may be a diminutive of the English loanword, but dodel may be independent of them. Even more instructive is the 1966 work by Werner Flechsig, who investigated the name for “bitch” in Ostfalia (Low Saxony). While discussing the word Tache and its eighteenth-century synonym Tiggel, he suggested that they might be cognate with dog. Tiggel resembles döggel. Both are diminutive forms (like dodel), and, as regards word formation, belong with the Old English animal names ending in –cga.

A piece of wood used as a doll.

A piece of wood used as a doll.Experience shows that, when we encounter an etymologically obscure late English word, a thorough search for possible cognates should be made in Dutch and Low (= northern) German. This is how a cognate of bad, also called by all lexicographers isolated, was uncovered (see my posts on this word). Dog, like bad, was probably a baby word. A promising approach to dog can be found in the 1982 paper by Ulrike Roider and in the 1983 paper by Thomas Markey. Roider listed German dialectal dogke “a foolish woman; doll,” obviously related to German Docke “doll.” Old dolls were often short pieces of wood dressed like manikins. One of the meanings of Engl. dock is “the solid fleshy part of a horse’s tail; crupper, rump”; the verb dock means “to remove the end of the tail; cut short.” Roider suggested that Engl. dog, allied to Docke, got its name from the practice of docking dogs’ tails. But perhaps there is a shorter way from “doll” to “dog.” If we are dealing with a baby word, it won’t come as a surprise that little children used the same monosyllable for the toy and the pet. The object’s form probably did not matter. Like bad, dog, with its phonetic variants, had limited currency in English and Low German, but, just as bad edged out evil, so did dog limit the sphere of application for hound.

The tail has been cut short, but there is probably no shortcut from it to the origin of the word dog.

The tail has been cut short, but there is probably no shortcut from it to the origin of the word dog.Markey cited similar Low German words in his discussion of dog. They mean “girl; doll; clump, straw bundle.” Like Roider, he referred to breeds of dogs with artificially abbreviated tails. But he followed Eric Hamp’s etymology of pig and reconstructed the basic meaning of those words as “small, young.” Hamp may have been right in connecting Engl. pig and Danish pige “girl,” but the common denominator was hardly the size of both. Let us remember that pig is another upstart; it superseded swine. Animals and children form a close union. “Little creature” applies to both, but it is more likely that dog and pig were vague, “polyfunctional” syllables out of the baby’s mouth. They could be applied to various objects, with toys, animals, and some pejorative epithets being especially prominent among them. Later grownups picked up such vague, rootless words, specified their use, and made them part of their vocabulary.

Featured image: Chihuaha by Teerasuwat Jiratarawat, Public Domain via Pixabay.

Images: (1) “Wooden toy doll” by Tropenmuseum, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons (2) “Braque du Bourbonnais” by Mic comte, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post I double dog dare you to reject my etymology, or the dog’s chances increase (even if ever so slightly) appeared first on OUPblog.

Much unseen: scandals, cultural stereotypes, and Nabil Ayouch’s Much Loved

Scandal hit just before Moroccan director Nabil Ayouch debuted his most recent film, Much Loved/Zine li fik, at the Director’s Fortnight at Cannes in May of 2015. Footage of the film about the lives of three prostitutes in Marrakech was leaked online, touching off a furor in Morocco. There ensued death threats against Ayouch and lead actor Loubna Abidar, the film’s ban in Morocco, obscenity charges, Facebook calls for the director’s execution, physical attacks on actors, and soon, Abidar’s exile in France. Throughout it all, however, few Moroccans actually saw the film, a condition that persists, at least insofar as is publicly acknowledged, to this day.

Violence aside, little of this is new or even particularly surprising – least of all the pillorying of a film sight unseen in Moroccan and social media by commentators, politicians, civic leaders, and self-appointed guardians of public decency. It is not even the first time that one of Ayouch’s films has kicked up controversy or been banned in Morocco.

Yet past controversies of films unseen – and, in the eyes of some, unseeable – have evolved largely within the spheres of Moroccan media and cyberspace. What is new in this instance is that the controversy has spread across the Mediterranean to France, Europe, and beyond. Observers on both sides of the northern Atlantic are quick to attribute such virulent attacks on a cultural product to religious conservatism, cultural taboos, or even sexual “misery” (assisted in this latter by the kind of culturalist analysis recently offered by best-selling author Kamel Daoud). In turn, many of those who express the greatest surprise at the uproar of Moroccan opinion assume, as does Ayouch himself, that if only people saw the film, it would become apparent that the nudity, sex, and vulgarity of the leaked clips work in the service of exposing deeper social issues concerning the role of women in Moroccan society.

Nabil Ayouch à la cérémonie des prix Lumières 2014 by Georges Biard. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Nabil Ayouch à la cérémonie des prix Lumières 2014 by Georges Biard. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.This presumes that critical blindness is exclusive to Moroccans who refuse or are prevented from seeing the film. Yet, what of Euro-American audiences? Might we not also suffer from some impaired vision?

Certainly, the attention paid to Much Loved obscures the remarkable vitality of film and discourses around it in a country where popular audiences continue to desert movie theaters in favor of bootlegs and downloads even as cineplexes attract wealthy viewers to commercial cinema. More significantly, simplistic analyses of the controversy downplay Moroccan audiences’ keen awareness of the power of globally circulating images and narrative cinema. Not least, it occults the dynamic and complex conversations taking place in Moroccan civil society around the very kinds of social issues that the film’s commercial realism purports to expose.

So, on what grounds do its critics dismiss Much Loved? As the charges against the film show, some call it obscene, an offense against public morals, but they and others also allege that it tarnishes the image of Moroccan women and that it encourages sex tourism. A picture begins to emerge, one that may even have feminist valences, especially when taken together with the critical reviews of western industry critics who have commented that the film contains “a few too many party scenes,” indulges in “the stereotype of the hard-as-nails prostitute,” is guilty of an “overly glossy finish,” and is most likely to appeal to “male viewers wanting close ups of pretty girls, naked flesh, and dirty pillow talk.” If such is the takeaway of Euro-American critics, why should Moroccans see anything different?

In expressing their disappointment that the realism of the film is not grittier (that is to say, somehow more authentic) critics abroad highlight a central concern of many Moroccans, namely that the film will be much viewed not just at home, but also beyond the country’s borders. When presented as a realistic film and framed by a one-sided understanding of the controversy it has elicited, Much Loved has the power to contribute to the long chain of one-dimensional, paternalistic, colonial, imperial, racist, misogynist, and differentially politicized images that flow ever more quickly across borders they simultaneously reinforce. Ayouch’s film, for its part, begins to expose some of these discourses through the figures of Saudi clients who emblematize transnational flows of capital that fuel sex tourism and trafficking. Still, the film’s relationship to the stereotype of Moroccan women as prostitutes that circulates to the North and East, resulting in forms of discrimination and violence both real and symbolic, remains problematic.

Certainly, violence against Ayouch and the film’s actors will do nothing to disrupt such clichés, serving only to harden stereotypes of Moroccans as, in the words of one reviewer, sexual hypocrites.

For our part, we Euro-American audiences must refrain from a certain symbolic violence by learning to see Much Loved as but one small piece of much larger, dynamic cinematic and social discourses.

And by the way, I haven’t seen the film. Yet.

Featured image credit: Impressive dunes of the Sahara desert [in Morocco] along the track by Maienga Agency Chaumont France. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Much unseen: scandals, cultural stereotypes, and Nabil Ayouch’s Much Loved appeared first on OUPblog.

Sanders’ contradiction on trade and immigration

It is hard to imagine two politicians that are further apart ideologically than Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump. Nonetheless, these two presidential candidates have a lot in common: their outsider status, their unrealistic fiscal plans, and a desire to punish foreigners for America’s economic problems. And while Trump makes no bones about his disdain for foreigners, Sanders’ anti-foreigner policy does not match his kinder, gentler rhetoric.

Both campaigns are built on the candidate-as-outsider principle. Trump is the proud non-politician who says outrageous things, and promises to fix Washington so that we won’t be a country of losers anymore. Sanders is a self-proclaimed democratic socialist: it is tough to get much further outside mainstream American politics than by declaring yourself a socialist of any kind.

Both candidates present wildly unrealistic tax and spending plans, which would blow up the federal deficit, according to independent analyses.

And both want to punish foreigners for America’s economic problems.

Trump is the more outspoken of the two, blaming Mexican immigrants for all manner of domestic ills: “They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” He will build a wall to keep them out and have the Mexicans pay for it. And as for Muslims, to paraphrase Walter Mondale’s characterization of Ronald Reagan’s view of handicapped people: “If you’re a Muslim who wants to immigrate to the United States, well you shouldn’t be.”

Trump has also made it clear that he is opposed to free trade, threatening to impose a 45% tariff on Chinese imports and a steep tariffs on American manufacturers like Ford or Carrier, who set up shop in Mexico and attempt to import products into the United States.

How does Sanders fit into the Trump “punish foreigners” mold? After all, his views on immigration could hardly be more different than those of Trump. He favors a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants, proposes easing barriers to asylum seekers, and opposes the current detention and deportation system and the militarization of the US border.

Although Sanders is happy to welcome immigrants to work in the United States, like Trump he is vehemently opposed to helping them work in their home countries—if that results in increased imports to the United States. Sanders takes pride in having opposed every trade deal ever presented to Congress, including NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement), CAFTA (the Central America Free Trade Agreement), and the normalization of trade relations with China.

Last fall Senator Sanders stated, “I do not want American workers to compete against people in Vietnam who make 56 cents an hour.” Although Sanders’ well-meaning approach to immigration might result in allowing a few more Vietnamese immigrants to the United States, he could improve the lives and increase the wages of a far greater fraction of Vietnam’s 90 million people—as well as helping American consumers–by allowing them to sell the product of their labor in the United States.

Freer trade helps low-cost producers find a market for their goods and high-cost producers somewhere to buy goods more cheaply than it would cost to produce at home. The results are not universal, of course. Some industries are hurt by trade, others are helped. And the lack of universal labor and environmental standards means that we accept some bad practices overseas in exchange for cheaper imports. Nonetheless, trade helps lift living standards both at home and abroad. Neither Sanders nor Trump seem to understand this.

What distinguishes Sanders from Trump is that he actually gives a damn about people who are not native-born Americans. This is admirable. And using America’s position as a major player in the global economy to promote fair labor practices and more strict environmental standards around the world should be high on the agenda of the next president.

Nonetheless, Sanders’ policy of being kind to foreigners when they want to immigrate, but hostile to them when they want to stay home and sell us stuff makes no sense.

Featured image credit: US-Mexico border at Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico; and California by Tomas Castelazo. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Sanders’ contradiction on trade and immigration appeared first on OUPblog.

The mysterious search for the Cardinal’s girlfriend

From the goosebump-producing thrills of Wilkie Collins’s fiction and the melodramas on offer at the Royal Princess’ Theatre to the headlines blaring in the Illustrated Police News, the Victorians savoured the sensational. The attention-seeking title above is patently untrue, yet, for more than five decades, John Henry Newman (the Cardinal) was emotionally, spiritually, and textually connected with a woman who just happened to be linked to the family of Gerard Manley Hopkins, the Jesuit poet. The woman in question, Maria Rosina Giberne, was and is a wholly intriguing figure.

Granted, she is never mentioned by name in Hopkins’s diaries or letters. Never. But Maria Rosina Giberne (originally de Giberne, a Hugenot family name) was, in all likelihood, the first convert to Roman Catholicism Hopkins ever met; a person who recommended Newman’s advice; an artistic role model; and an example to Hopkins’s family that a papist who has taken religious vows was not necessarily the anti-Christ.

The connections begin with George Giberne, who served the British Empire as a judge in India. In July 1846, after retirement from the East India Company, he married Maria Smith, the younger sister of Hopkins’s mother, Kate. The couple then moved to Epsom. Biographers mention that Hopkins was ‘the favourite nephew’ of Maria and George Giberne, visiting them often. The artistic influence of the couple is significant: his aunt took him sketching; his uncle, an accomplished photographer, introduced Gerard to photographic theory and practice, and used him as a model. (George Giberne’s photos are the only known records of Hopkins’s youthful appearance.) Not only did the Gibernes encourage Hopkins’s interest in drawing (many of the architectural features sketched in his diaries are modelled on George’s photographs), but it was at Epsom that Hopkins met George’s younger sister, Maria Rosina, also an artist. Maria Rosina Giberne became an Evangelical at twenty, then a Tractarian, then, with Newman as her spiritual adviser, she converted to Roman Catholicism in December 1845. In Newman’s company, she was presented to Pope Pius IX in autumn 1846; she lived in Rome until 1855, earning her living as a portrait artist (in later years, she copied religious paintings for English churches). In 1863, she became a nun, Sister Maria Pia (in honour of the Pope who encouraged her), as part of the Order of Visitation at Autun, France. She died of a stroke in December 1885 (when Hopkins was “at a third remove” in Dublin).

I’Engraved portrait, with autograph, of John Henry Cardinal Newman, published in 1882′, by an anonymous engraver. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

I’Engraved portrait, with autograph, of John Henry Cardinal Newman, published in 1882′, by an anonymous engraver. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Giberne’s bonds with the Newman family were created by a marriage and cemented by suffering. Her elder sister married Walter Mayers, the Anglican clergyman and schoolmaster who introduced John Henry Newman to “a living faith”, in 1816. Maria Rosina became part of their interconnecting social circles. In January 1828, she was visiting the Newmans when Mary, the youngest daughter, suddenly took ill and died. (Fifty years later, Newman vividly recalled the event in a letter to Sister Maria Pia, the grief still fresh.) Francis Newman, the proverbial “difficult” son, proposed to Maria Rosina at least twice, but it was her relationship with John Henry that endured. The latter refers to Maria Rosina in one extant letter to Hopkins, sent 26 September 1870, on the occasion of Hopkins taking his first vows as a Jesuit. After congratulating Hopkins “on an event, so solemn and so joyful to you”, Newman observes: “Miss Giberne is very happy, I find, at Autun, but just now in sore distress… Indeed, who cannot be in distress about France[?].” (He was referring to the Franco-Prussian War, and the Communards’ assassination of the Bishop of Paris and fellow clergy.)

Why was it too challenging to eke out even this bare-bones biography of a minor but significant figure in the lives of two eminent Victorians, Newman and Hopkins? First, there is the anti-feminist factor, so common in the historiography of any era. Because the well-trodden “paths of male entitlement” were unavailable to Maria Rosina Giberne, there are no easily-recovered traces of her in the records of, for example, Highgate School, or Eton, or Oxford, or the Inns of Court, or the Royal Academy, or the National Gallery. (Giberne made several drawings of the Newman circle, and created at least three portraits of her dear friend: one in which he wears his Oratorian collar and cassock (c. 1846‒47); one in which he is seated, in Rome, with Ambrose St. John (c. 1846‒7); and Newman Lecturing … in Birmingham (c. 1851). All are owned by the Birmingham Oratory, as is her watercolour self-portrait in a nun’s habit (c. 1863), which continues to hang in Newman’s room.) Her textual and artistic ‘remains’ survive because of one man she knew—Newman—and a great-nephew, Lance de Giberne Sieveking, famous for the people he knew or could write about.

Secondly, there is the stigma factor. The Newman biographical industry has been prodigious since his death in 1890, but Maria Rosina Giberne has been something of a persona non grata presumably because acknowledging a profound emotional bond with a woman would somehow detract from his saintliness. (The exception is Joyce Sugg, Ever Yours Affly: John Henry Newman and His Female Circle, 1996.) No established Newman scholar apparently knows that Sister Maria Pia is Hopkins’s aunt by marriage. And yet—there she was, painting well-regarded portraits of significant nineteenth-century figures in three countries, illuminating Newman’s life, gracing Hopkins’s. In the words of the Latin inscription Newman chose for his memorial tablet: “Ex umbris et imaginibus in veritatem”, “from shadows and images to truth.”

Featured image credit: ‘Newman’s desk in the Birmingham Oratory’ by Lastenglishking. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The mysterious search for the Cardinal’s girlfriend appeared first on OUPblog.

May 31, 2016

Reading list for World Oceans Day

When the Earth is viewed from space, it’s mostly blue. In fact, the ocean covers over 70% of our planet. Life began in the world’s oceans, and today – billions of years later – we’re no less dependent on it. From the diverse organisms which call it home, to the complex ways it helps keep global climates in check, our own survival is undeniably linked to that of the ocean.

Yet, the ocean is under increasing strain. Climate change, pollution, and damaging human activity are threatening its survival, along with the many organisms living in it. One instance of this is the ocean’s rising acidity as it absorbs more pollutants from the atmosphere: especially unwelcome news for any creatures with calcium carbonate shells, such as corals and crabs, or if you’re one of the countless sea creatures or millions of people dependent on coral ecosystems. This is just one of the many ways in which the ocean is under threat.

World Oceans Day is a chance to celebrate the ocean and ensure its future conservation. Ahead of World Oceans Day, which takes place on 8th June, we’ve collected freely-available journal articles, book chapters, and author blog posts which provide fascinating insights into the ocean, and underline the importance of its preservation.

‘The life of oceans: a history of marine discovery’ by Jan Zalasiewicz and Mark Williams on the OUPblog

In 1841, Edward Forbes pronounced the deep ocean dead with his “azoic hypothesis” – he claimed that life there simply could not exist. Since then, we’ve gradually been discovering the fantastic and bizarre creatures who inhabit the deep ocean, spending their lives in darkness.

‘ Applying organized scepticism to ocean acidification research ’ by Howard I. Browman in ICES Journal of Marine Science

Ocean acidification (OA) poses a very real threat to the health of the ocean and the organisms living within it. In this journal article, Browman discusses the trajectory of research about OA, the causes of OA, and the risks it poses to marine organisms and ecosystem processes.

‘ Predicting the impact of ocean acidification on coral reefs ’ by Paul L. Jokiel in ICES Journal of Marine Science

The world’s coral reefs support a vast ecosystem of ocean life. Yet, with rising ocean acidification levels, reefs are dying at an alarming rate. This journal article charts the science behind ocean acidification, coral bleaching, and the models used to predict future reef decline.

Sea otter by schucke. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Sea otter by schucke. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

‘ Marine Mammal Conservation ’ by John R. Twiss et al. in Foundations of Environmental Sustainability: The Coevolution of Science and Policy

Effective conservation goes hand-in-hand with policy-making and legislature. In the early 1970s, the United States, in an effort to curb the slaughter of thousands of dolphins, whales, and seals, passed the Marine Mammal Protection Act. This chapter sketches the context in which the act was passed, and the challenges it has since faced.

‘ Ocean-Atmosphere Interactions ’ by Anthony J. Vega in Encyclopedia of Climate and Weather

Did you know that in addition to the input of fresh water by continental streams, the saltiness of ocean water is directly related to the amount of sun it receives? For example, the saltiest areas of the ocean occur in the cloudless (and thus precipitation-less) regions of the planet around 30 degrees north and south latitudes.

‘ The Oceans and Human Health ’ by Lora Flemming et al. on the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science

From food to travel, humans have always depended on the ocean for survival and prosperity. Recently, a growing body of evidence is beginning to uncover a direct link between the health of humanity and that of the ocean. Is there a way to promote human health and well-being through sustainable interactions with the coasts and oceans, such as the restoration and preservation of coastal and marine ecosystems?

‘ Incorporating Historical Perspectives into Systematic Marine Conservation Planning ’ by John N. Kittinger et al. in Marine Historical Ecology in Conservation

By its very nature, environmental conservation looks to the future. Yet lessons can be learnt from history. In this chapter, the authors of Marine Historical Ecology in Conservation outline the many lessons ocean conservation efforts can take from the past.

Featured image credit: ‘Waves and Ocean’. Public Domain via Public Domain Pictures .

The post Reading list for World Oceans Day appeared first on OUPblog.

Conjuring 18th-century affekt with Alberti bass on the modern piano

Affekt (the ability of music to stir emotions) is the foundational pillar for eighteenth-century style. It was achieved through attention to detail and proper execution. And done in good taste, which implies a deep understanding of proper practices of the time. Nearly every notational and performance decision was based on affekt—everything from formal structure to note values, dynamics to articulation, and accompaniment patterns such as Alberti bass.

Expressing affekt begins with clearly understanding and conveying the structural or formal foundation and harmonic function. It is upon this that all other elements are laid. Just like the beauty of the Washington National Cathedral is built on solid footings, pilings, and framework, eighteenth-century music finds itself grounded on thoroughbass. C. P. E. Bach devotes a full twenty-five percent of his Versuch to this fundamental component. But it’s not just the harmony, it’s how the harmonic structure drives expression. And with this knowledge interpretive and expressive answers are laid at our feet. Consequently, how to execute expressive embellishing components such as Alberti bass are then more easily determined to bring richness and clarity to our playing.

The Harvard Dictionary of Music points out that broken-chord patterns date back to the seventeenth century, of which Alberti bass is the most commonly known. It is “an accompaniment figure, found frequently in the left hand of the 18th-century keyboard sic, in which the pitches of three-pitch chords are playing successively in the order lowest, highest, middle, highest, as in … Mozart (Sonata in C major K. 545).” The figure is named after Italian singer, harpsichordist, and composer Domenico Alberti (1710-1740?), who used this figuration extensively. Today, Alberti bass has taken a more generic definition, referring to various configurations of arpeggiated broken harmonies.

Once it appeared on the scene, the Alberti bass took hold. It was very popular around 1800 and went out of fashion quickly as new pianos appeared that contained a more resonant soundboard that resulted in a naturally louder, longer-lasting tone. The perfect genre for Alberti bass configurations was the sonata; the perfect instrument to execute them on was the fortepiano. It is extremely conducive to the mechanics of the fortepiano (with a bright, clear attack), lending energy to the declamatory nature of the instrument and rhetorical style of the time. What is often described as simply an accompaniment pattern today is much more important in creating affekt in eighteenth-century style. The Alberti bass motives create rhythmic and harmonic energy, drive, and momentum—pulse and forward propulsion—whether dramatic or lyrical. When it appears momentum intensifies. A clever quip Malcolm Bilson provided says it all: “When it shows, it goes!”

The Alberti bass shapes vary according to need and levels of intensity. As the intensity of the affekt relaxes, so does the activity of the figuration.

The most intense figuration that provides optimal rhythmic energy, drive, and opportunity for polyphonic implications outlines a 5-1-3-1-5-1-3-1 pattern, seen in Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 309/I, mm 73-74. (Copyright G. Henle Verlag, Munich, 2005)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Audio-Ex-3.2a.-Mzrt-K.-309-I-Baddeley.m4a

In mm. 15–16 of the Presto from London Notebook, Anh. 109b no. 3 (15p), mm. 15-25 (Copyright G. Henle Verlag, 2005), by Mozart, the affekt is less intense than that of K. 309. The texture is thinner and the implied polyphony has been reduced to two voices. Yet the intervals and 1-5-1-5-1-5 figuration keeps things quite “live.”

Drive is lessened further at mm. 22–24, when the figure shifts to a rolling and relaxed 1-3-5-3-1-3-5-3 in the right hand. Here, the suspense comes from the melodic motive in the left hand.

The affekt is the least dramatic and almost lyrical in mm. 18–21, where the left-hand pattern outlines a simple progression with arpeggiated four-note chords.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Audio-Ex-3.3a.-Mzrt-London-Notebook-Anh.-109b-Baddeley.m4a

The change in sound aesthetic from one figuration to another is quite dramatic.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Audio-Ex-3.2b.-Mzrt-K.-309-I-Baddeley.m4a

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Audio-Ex-3.3b.-Mzrt-London-Notebook-Baddeley.m4a

There are some concepts that apply regardless of the instrument on which Alberti bass is executed: Heed notational clues to understand formal structure from the very beginning rings true for any repertoire at any level from any era; and let the figuration drive expression and momentum.

The trick lies in conjuring up this sound aesthetic on an instrument for which the figuration was not intended, the modern piano. So what does one do “when it shows?” Many modern players attempt to repress, subdue, or minimize Alberti bass. To do so is much like trying to ignore that pesky gnat at a picnic. It is simply annoying. More importantly, it fails to serve the purpose for which it was intended.

It is most effective to highlight the affekt, found in its rhythmic drive, secondary melodies, or dramatic or beautiful qualities. This effort will bring energy and focus to the motive, as was historically intended and can be reconciled on the modern piano to an effective end:

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Audio-Ex-3.2c.-Mzrt-K.-309-I-Baddeley.m4a

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Audio-Ex-3.3c.-Mzrt-London-Notebook-Baddeley.m4a

There are simple technical principles that can be applied to facilitate execution:

When constructing Alberti bass figurations, begin by creating a pulse. Practice in pulses of one pulse per measure, two pulses per measure, and eventually, one pulse with each beat. The affekt of the section will determine the appropriate number of pulses. As intensity increases, tempo stretches. Pulsing the Alberti bass provides many benefits. The rhythmic pulse will be defined and enlivened. The intermediary notes will naturally be softer. Rushing, that ever-present nemesis, will be kept at bay!

When shaping the Alberti bass, begin with the bass notes (in pulses) alone in conjunction with the melody. This clarifies voice leading. Next, “divide” the hand in half. The bass note is a downward rotation, and the remaining notes are the upward rotation, creating a stroke for each unit.

Envision “orchestrating” Alberti bass figurations and harmonic contours to add depth and substance to the voices. This practice also brings the figure into focus and provides clarity.

Identify and bring out polyphonic contours to add interest and relevance to the figure.

Formal structure and harmonic function provide the solid groundwork and long-lasting beauty on which eighteenth-century affekt is built. Alberti bass is one of the tools available to enhance and ornament the foundation. Taking great care in shaping and highlighting the various figurations provides the necessary means to conjure up eighteenth-century affekt—even on the modern piano!

Image credit: “_MG_8965” by Dmitriy K. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Conjuring 18th-century affekt with Alberti bass on the modern piano appeared first on OUPblog.

Banks, politics, and the financial crisis: a demand for culture change (Part 1)

After the fall of the Berlin wall and before the collapse of Lehman, the political mood was such that banks were able to persuade the world that high levels of profit and remuneration were justified – the banks told the world that their industry had a key role in wealth-creation. They preached the efficiency of markets and the people listened.

However, when Lehman’s collapse in September 2008 precipitated a global financial crisis, banks were able to persuade governments the world over to spare them the harsh market discipline they had espoused as the engine of wealth creation – and had themselves visited on their customers. The huge cost of the banks’ bail-out then fell on the shoulders of bemused tax-payers. This outcome created an impression of hypocrisy; a sense that banks consumed rather than created wealth – and a sense of an account not yet settled as between taxpayer and banks. The political weather began to turn; electorates across the world were no longer prepared to accept the bankers’ arguments as being made in good faith; instead they saw those arguments as self-serving. The people stopped listening.

Thus was born an enduring political sense that the financial system is rigged in favour of the banks and against both “real” business and the people. It is of no account that respectable bodies of opinion observe that at least one cause of the financial crisis was US politicians and regulators expressly deciding, as a matter of settled policy, to persuade banks to lend to parts of the electorate that banks would not otherwise have lent to: the sub-prime mortgage market. Those voices do not carry the day.

By degrees, the political consensus has moved from “light touch” regulation and towards “heavier” regulation. This political climate exists because, in 2008, electorates were told the banks were too big to fail. In the eight years since, electorates have been paying up, but neither are the banks any smaller nor does bankers’ remuneration bear any relation to their own. They are therefore acutely aware that they will be called on as taxpayers to bail out banks in the future – and they don’t like it. Banks have not been able to alter this climate of opinion. Perhaps they are wise not to have tried too hard. Nobody’s listening anyway.

Instead, as the years since 2008 have passed, the abstract concept of a move from light to heavy regulation has grown a little more concrete. Today’s political climate demands a change of culture in the financial markets away from excess and irresponsibility and towards responsibility and accountability: prevention being better than cure.

And yet, adaption of behaviour to this new political climate was not the banks’ first reaction. Rather, from 2008 to 2013 they often remained defiant of criticism and, in part, resistant to regulatory action. Perhaps in response to the generalised nature of the anger directed towards them. In the years after 2008 the government demanded the banks rebuild their balance sheets, while at the same time demanding increased lending to SMEs – self-contradictory instructions. What’s more, in January 2011 the UK government imposed an £2.5bn annual levy on the banks’ balance sheets, a form of retrospective sin tax devised to sate the public sense of an account unsettled.

Sometimes, reasoned argument makes matters worse. In April 2011 the High Court rejected the British Bankers’ Association’s application for judicial review of the Financial Service Authority’s (FSA) redress mechanism for customers mis-sold PPI cover. The banks’ temerity in launching this legal challenge appears to have particularly enraged the Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards (PCBS), established in July 2012 and which reported, in thundering terms, in its final report of June 2013 under the menacing title “Changing Banking for Good”. The temper of the times was such that in November 2013 the Entrepreneur in Residence at the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills published a report accusing the wicked banks of deliberately taking profitable SMEs into insolvency to enhance the banks’ short-term profits.

In September 2012 the then Chief Executive of the FSA produced a final report that concluded that banks had been conspiring to fix LIBOR. This scandal must have been a significant cause of the angry tone of the PCBS’s report eight months later. It is to this revelation that a report by New City Agenda in November 2014 on the culture of British retail banking attributes significance because it “forced many in the industry to face up to the fact that there would not be a rapid return to business as usual. Industry insiders started to accept fundamental change was needed”. Now, at last, bankers appear to agree with regulators and politicians that trust in the industry needs to be rebuilt by effecting a change in banking culture.

In September 2013 seven banks voluntarily established the Banking Standards Board, which published its inaugural report in May 2014. That report proposed establishing the Banking Standards Review Council (BSRC), a body, paid for by banks, which would have responsibility for establishing and ensuring compliance with a voluntary code of practice for all bankers operating in the UK.

The BSRC report was produced with the benefit of 200 responses to a consultative document from distinguished stakeholders in the banking industry. The thrust of the BSRC’s work will be to assist banks in achieving internal culture-change.

The premise of the BSRC’s programme – and New City Agenda’s supporting analysis – is that you “cannot regulate a culture into existence”. For that reason it describes itself as a “call to action” to the management of banks to embed management techniques that will deliver the culture change the political climate demands.

Will the public trust the BSB/BSRC to make change? On 31 December 2015 the FCA abandoned the Thematic Review of Banking Culture it had in its business plan for that the following year, leaving the issue of culture change to the BSB/BSRC – in other words to the banks themselves. The reaction of the public so far suggests a further collapse in trust in both regulator and banks. Will this really go away?

Featured image credit: Paper money, extreme macro, by Kevin Dooley. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Banks, politics, and the financial crisis: a demand for culture change (Part 1) appeared first on OUPblog.

May 30, 2016

To dream or not to dream: What are the effects of immigration status and parental influence on Latino children’s access to education?

Much has been written about the potential of immigration reform to level the playing field for unauthorized children and youth in the United States. Research shows that in addition to, or perhaps ahead of, advocacy for immigration reform, including passage of the DREAM Act legislation in every state of the Union, there is a real need to work with Latino immigrant families on realizing the relationship between levels of formal schooling of immigrant children and parents, and their employment on the one hand, and upward mobility prospects on the other. Those concerned with better educational outcomes for Latino children and youth must also work on improving educational levels and attitudes towards education of their parents.

Jamie’s story illustrates my point well. Jamie was born in the United States to an undocumented mother, who since gained US citizenship. His stepfather is still undocumented. Jamie’s mother owns several businesses and is doing quite well, and has the financial means to contribute to her children’s education. Luckily Jamie’s younger brother, Juan, received a full scholarship to an Ivy League university, and graduated last year without needing his mother’s financial help. Jamie was not so lucky. Nevertheless he did enroll in a public university in upstate New York. First he wanted to major in engineering because he thought it would be a marketable degree, but while in college he discovered his love of writing and switched to English. After three years in New York, Jamie decided to transfer to the University of Maryland, because he could live at home and save money. Unfortunately he still owed New York tuition, so Maryland told him he could not transfer until all of his financial obligations were resolved. Jamie moved back home and was taking classes at Montgomery College while working for tips in his mother’s restaurant; she would not pay him wages. Later he got a job as a cook in an upscale restaurant and stopped taking classes. He works hard and takes every possible overtime shift to pay his student loans. His mother told him how glad she is that “he is following in her footsteps.” I checked in with Jamie recently and indeed he is not in college, and is being groomed by the restaurant owner to become a head chef.

Compare that with Alejandro, an undocumented child, who dropped out of school in 9th grade. He was lucky to have the counsel of his aunt. On her advice, he went to the Latin American Youth Center (LAYC) and got connected with the Next Step School. He did very well there and received his GED within a very short time. In addition, he got certified in Microsoft, and during the summer of our first interview he was teaching a computer class at LAYC. Alejandro is committed to furthering his education. He didn’t understand how undocumented youth can pursue higher education and on what conditions, but l he trusted that his counselor at LAYC would help him figure things out. I checked with Alejandro recently and indeed LAYC successfully helped him apply for DACA. Alejandro is interested in becoming a medical examiner.

Jamie’s and Alejandro’s stories demonstrate the importance of family in supporting—financially and emotionally—Latino youth as they pursue educational goals. Jamie’s mother did not fully understand the importance of higher education. She did not want to contribute to Jamie’s university tuition. She also discouraged her oldest daughter, Elena, from accepting a scholarship to a women’s college because she feared that Elena would not find a husband in an all-women’s college. Elena did not want to enroll against her mother’s wishes. After a very tumultuous adolescence in a female gang and single motherhood, Elena realized that she needed a college degree to support herself and her toddler daughter. Currently, Elena is studying nursing and working part-time.

Image credit: library books shelves-student by StockSnap. Public Domain via Pixabay.

Image credit: library books shelves-student by StockSnap. Public Domain via Pixabay.Parental engagement with their children’s school—a positive predictor of academic achievement, higher self-esteem, and higher rates of high school completion and college enrollment—is often a challenge for immigrant families. While many of the immigrant parents I interviewed had high educational aspirations for their children, few had the resources to realize these goals. Employment pressures—many parents worked more than one job or worked graveyard shifts—also contributed to parents’ increasing inability to actively engage with their children’s education. Research conducted suggests that parents’ engagement with schools decreased as the children got older. Latino parents of small children are eager for their children to succeed in school and meet developmental and educational milestones. However, with few exceptions, parents of high school students were not interested in their children’s achievements or problems at school. It seems that parents who have limited education themselves aspire for better education for their children, but that does not necessarily mean a lot more formal education: finishing primary or middle school seems sufficient. Jamie’s mother who supported her children throughout primary and secondary school thinks her role ended there.

Resilience and perseverance in pursuing educational goals are shaped not only by relationships with caring and supportive parents; approval of extended family is also important. Maria is a case in point. Maria, a young local community leader, went to college and graduated with a BA in anthropology. Maria is working for a non-profit organization helping Latino immigrant families in Northern Virginia. Her uncles constantly barrage her mother that she raised such “a lazy girl.” They consider Maria to be lazy because she does not “work with her manos [hands].” Maria’s professor would like her to come back to school to get a master’s in applied anthropology; she promised to help Maria secure financial aid. Maria said: “I would love to go back to school, but I am sure that would enrage my uncles even more and they would take it out on my mother.”

A professional Latina in the DC government also spoke about the lack of understanding of the value of education among her extended family. She said: “Even my mother-in-law with whom I have a very good relationship could not understand why my husband and I mortgaged our house to put our two daughters through college.”

Speaking about the wider Latino community in the area, she added: “By and large the Latino parents in this area do not appreciate education, because they themselves have little formal schooling. Educational loans are not even on most immigrants’ radar screen; it has less to do with poverty and more to do with valuing education.”

Factors such as poverty, parents’ class and formal education levels, and family strategies favoring employment over schooling are much more tangible in the lives of unauthorized Latino children than legal status per se. The family’s unauthorized status is often hidden from the child’s conscious experience. Many Latino children find themselves in what Roberto Gonzales calls “suspended illegality” through late adolescence. In kindergarten, primary, or even middle schools, they did not have to face full on the consequences of their immigration status. However, once they entered high school, particularly in senior year, when their peers are applying to college, unauthorized children start realizing the effects of their immigration status on their future after high school.

There is an urgent need to work with immigrant parents to better understand the educational system, and the necessity to complete high school and go on to college in order to ensure upward mobility in the labor market and life satisfaction.

Featured image credit: graduates graduation cap and gown by stevensokulski. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post To dream or not to dream: What are the effects of immigration status and parental influence on Latino children’s access to education? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers