Oxford University Press's Blog, page 503

June 5, 2016

Living with multiple stressors in the marine environment

When asked to think about the ocean, most people imagine a pristine habitat in the tropics with golden sands and clear blue waters, or the diversity of fish associated with coral reef communities. Yet, the oceans of the world are being influenced by an array of human activities that are not necessarily visible, from the input of chemical pollutants and nutrients, to the absorption of carbon dioxide and heat, and the effects of UV radiation and noise. All of these have increased over the last few decades, raising concerns about the effects that multiple co-occurring stressors may have on marine ecosystems and their levels of biodiversity.

There is a difficulty, however, in studying the responses of marine organisms and communities as the effects of individual stressors may not be expressed at the same time and in the same way—and may be context dependent. In addition, the expression of these effects may take many years to emerge. Understanding these interdependencies has become a major theme in contemporary environmental science, but demands an interdisciplinary focus that can be difficult to achieve.

Traditionally, the biological effects of human activities have been studied independently in the laboratory. More recently, attention has switched to the combined effects of multiple stressors in order to more fully appreciate the changes that may occur in the natural environment. However, there are a number of challenges associated with studying the effects of multiple and simultaneously acting stressors in a ‘real world’ scenario.

Plastic & Garbage! A Bunaken Beach by Fabio Achilli. CC0 BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Plastic & Garbage! A Bunaken Beach by Fabio Achilli. CC0 BY 2.0 via Flickr.Humans can influence marine ecosystems in a number of ways. By first studying the physiological effects of single and multi-stressors on individual species, biologists can learn about the relative vulnerabilities of marine species to environmental change. Variations in their responses at different life stages can influence the survival of populations and communities, and inform on their ecology. Changes in the ability to respond to environmental change can have a negative effect on growth and development, as demonstrated by marine invertebrates exposed to lowered salinity, increased UV radiation, and/or increases in CO2 levels in the seawater. Different strategies are used to survive areas of low oxygen and several mechanisms are influenced by chemical contaminants. All of these responses can be altered by climate change, and in particular, ocean warming. Coastal eutrophication can occur in regions of high nutrient inputs (nitrogen) with early life stages being more sensitive to nitrogen stress. Finally the stress of human activity can come in the form of acoustic pollution and its effect on hearing and the integrity of the auditory system. All of these factors can trigger changes in biological interactions, community structure, and trophic dynamics, ultimately leading to a loss in biodiversity and alterations in ecosystem structure and function.

Complex interactions between various stressors further complicate the identification of generic processes or patterns, but they also have the potential to help towards the development of strategies for the management and conservation of marine habitats. Developing sufficient knowledge and collating information from several fields of science, however, can be particularly challenging. At present, only a handful of studies have gone beyond the traditional domains of a scientific discipline, combining physiological responses with changes in what species do, when they do it, and how efficiently they continue to do so. Gaining such interdisciplinary knowledge is going to be vital if we are to understand and mitigate the effects of human activity on our natural heritage.

Featured image credit: Coral reef by Jan-Mallander. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Living with multiple stressors in the marine environment appeared first on OUPblog.

Ecological development and adapting to change

World Environment Day is celebrated on 5 June to encourage positive environmental action. Instituted by the United Nations in 1974, it provides a global platform for public outreach in promoting the importance of the protection of our environment. This post explores instances where the environment affects the life living within it and future adaptations.

As in many reptiles, the sex of leopard geckos is determined not by chromosomes, but by the environment. Hatchlings will develop into either males or females depending on the temperature they experience as incubating eggs. Sex isn’t hard-wired because the key genes involved in gonad differentiation are up- and down-regulated by temperature, so a fairly warm nest will produce mostly males, a cool nest mostly females, and a nest close to the temperature threshold, an evenly mixed brood.

In other organisms as well, all kinds of environmental factors – from light to nutrients to social interactions – can be important players in gene regulatory pathways. In 1953, when Watson, Crick, and Franklin discovered that the double-helix DNA molecule carried genetic information, the DNA gene code (or genotype) of an animal or plant was viewed as a ‘blueprint’ for its features. It turns out, however, that an organism’s development is often strongly influenced by its environment. As a result of the many ways that environmental factors can affect gene expression (via mechanisms such as epigenetic silencing, hormone levels, or metabolic feedbacks), we can now view the genotype as a more or less flexible repertoire of possible outcomes, rather than a rigid blueprint.

Image credit: Eublepharis macularius by Eduardo Santos. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Eublepharis macularius by Eduardo Santos. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.A closer examination of the leopard gecko reveals a second key point. Sex determination isn’t entirely environmental, because the precise temperature threshold for developing as a male rather than a female is influenced by an animal’s genotype. As a result, the sex of a particular hatchling depends on both its genes and its environment. In fact, the vast majority of traits in all kinds of organisms reflect this kind of developmental interaction between ‘nature’ (the individual’s genotype) and ‘nurture’ (its environmental conditions).

Eco-Devo (ecological developmental biology) is the field of biology that investigates how a given plant, animal, or microbial genotype can produce different outcomes in different natural environments. There are countless examples of this kind of developmental plasticity. In cichlid fish, features such as jaw anatomy and tooth shape develop differently if a juvenile fish’s early diet consists of soft foods versus harder prey items such as larval snails and shrimp. These developmental responses in turn shape the fish’s lifelong food preferences and thus its ecological impact as a predator.

Juvenile diet also influences development and feeding behavior in certain birds and insects. For instance, Melanoplus grasshoppers that are fed fibrous, low-nutrient food develop larger, more muscular mouthparts and a larger gut compared with individuals given food that is easier to chew and more nutritious. In mammals, low quality food can likewise result in suitable changes to the digestive tract such as increased gut capacity and larger intestinal surface area to maximize nutrient uptake. Plants also develop differently when resources are scarce: in low light, they produce large, thin leaves that catch as many photons as possible, and in dry or nutrient-poor soil, they allocate more of their body mass to roots to generate large uptake surfaces.

Plastic responses to the environment can even extend to the next generation. Yellow monkeyflower plants subjected to simulated herbivory produce offspring with dense defensive hairs, even though the seedlings themselves have not been damaged. In this way, parent plants living in a site where herbivores are present can pre-adapt their progeny to repel potential attackers. This adaptive effect results from inherited modifications to gene expression without any changes in the offspring DNA sequence per se.

Image credit: (Polygonum persicaria) produce larger, thinner leaves that capture more photons compared with genetically identical plants grown at high light, by Dan Sloan. Courtesy of Sultan lab.

Image credit: (Polygonum persicaria) produce larger, thinner leaves that capture more photons compared with genetically identical plants grown at high light, by Dan Sloan. Courtesy of Sultan lab.Clearly, in many cases, plastic eco-devo adjustments to different ecological conditions result in a plant or animal body that is functionally fine-tuned to the environment (or parent’s environment) that brought it about. For this reason, eco-devo studies provide new insights to how adaptation works. Because precise cues and developmental pathways are influenced by genes, these studies also show how genetically distinct individuals or populations may differ in response.

Eco-devo information is especially important to understanding the potential for organisms to succeed in the changed environments being created by human activities. This potential depends in part on each species’ environmental response patterns to aspects of its habitat. In tropical anemonefish, parents raised in seawater with predicted future levels of carbon dioxide produce progeny that show none of the usual negative effects of high CO2, due to adaptive effects on enzyme function that are inherited from the pre-exposed parents. Individuals in certain bird species respond to warm days by speeding up their developmental timing, allowing them to raise their young in synch with the earlier onset of Spring due to climate change (and gobble the peak supply of caterpillars). Yet other species lack these beneficial types of plasticity, putting them at greater risk of extinction in altered conditions.

In some cases, new patterns of environmental response may evolve which will maintain adaptation under changed conditions. For this to occur, populations must contain genetic variation for eco-devo responses, so that natural selection can promote the increased frequency of genotypes with the most beneficial response patterns. In current populations of the leopard gecko, for instance, only males would be produced at the higher nest temperatures that are expected under global warming. The presence of genotypes with different sex-determining temperature thresholds would provide the raw material for populations to evolve higher thresholds that would allow both males and females to be produced. Fortunately, this kind of genetic variation has been found in this species, but such in-depth information about eco-devo variation is seldom available. Another worrying fact is that changes to environmental cues may derail existing adaptive pathways, requiring the evolution of new cues to guide development. We need to learn a lot more about eco-devo responses to predicted future environments, and about genetic variation for these responses, to understand how various species are likely to fare in a changing world.

Featured image credit: Flower floral blossom by GLady. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Ecological development and adapting to change appeared first on OUPblog.

June 4, 2016

The forgotten history of piracy in the Indian Ocean

When I first started thinking about retelling a story of piracy, two images almost immediately sprang to mind. The first is the famous story of Alexander the Great who supposedly once asked a pirate whom he had taken prisoner why he claimed possession of the sea by hostile means. The reply was pithy: “What do you mean by seizing the whole earth? Because I do it with a petty ship, I am called a robber, while you who does it with a great fleet are styled emperor.” The second image, a recurring trope in the Asterix comics illustrated by Albert Uderzo, is more comic. Think of the motley crew of lowborn men who man a small pirate ship and try to seize whatever they encounter – but usually come off worse in their battles. Both of these images are typically European, with the Mediterranean and the Atlantic emerging as the normal theatre for piratical actions.

But where did the Indian Ocean figure in the story of piracy narratives? Piracy, we know, is as old as maritime trade itself and yet the history of piracy in the Indian Ocean is complicated and distinctly different from the history of piracy elsewhere. Why? The difference is partly to do with the fact that the Indian Ocean was technically speaking mare librum, a “free sea” where merchants could trade and navigate without formal permission, and partly because war-time action on sea was rare. Not surprisingly, the Europeans, who brought with them grandiose claims to maritime supremacy also gave themselves responsibility for maritime peace. They introduced – in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries – an altogether new dimension to ideas about sovereignty and transgression against it.

Fictional pirate ship, re-created, by Robert Pittman. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via Flickr.

Fictional pirate ship, re-created, by Robert Pittman. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via Flickr.This contest between sovereignty and piracy did not remain confined to the level of ideas. In the wake of new dispensation assembled by the European entrants, there occurred a massive destabilisation of littoral society whose peoples resorted to new strategies of survival and resistance. They are the ones who became the dreaded pirates— the unreasonable outlaws who had to be contained, disciplined, and subjugated by European navies.

The littoral peoples—and those among them who were outlaws—had, for their part, a different story to tell. For many of them, not only were the Europeans singularly responsible for the misery of their coastal society, they were pirates themselves. They saw the Europeans as pirates who attacked at will and coerced seafarers and merchants to pay for their passes and permits in order to venture on the seas.

Accordingly, the ballads of eastern Bengal describe the fearsome harmads (derived from the Portuguese armada), who attacked the rich and the poor, the aged and the children, only to sell them as slaves. They also speak of the bombets (“bombardiers”)—the varied crowd of raiders on the sea which included littoral peoples. Members of this latter group, when charged with breaking the law, retorted quite simply that they were caught between the devil and the deep blue sea. Accepting European protection for every venture was costly and drove them to poverty; not accepting it made them pirates to be hunted down and pursued.

Strangely enough, in this contest between sovereignty and piracy, law played a minor role. European sovereigns periodically made ritual invocations of the natural law that held pirates as enemies of all mankind, but in reality, the seas remained an unbounded realm. Thus, in the context of India’s western seaboard, piracy happened more in the littoral than on the high seas, and it involved close networks that extended all along the coast and further outwards into Oman and the Arabian Gulf. Piracy was part of a mobile and changing geography that kept close to the coast, drawing support from local bosses, shrines, and villages, and thus making the process of colonial subordination a prolonged and tedious affair. The gradual and extended nature of imperial expansion highlighted moments of rupture and confrontation which, in turn, generated an archive of pirate depositions and testimonies.

It is through these testimonies that we can access the slippery world of the salty subaltern. They make for fascinating reading and once we get past the formulaic nature of the depositions, all sorts of tantalising details about lives, livelihoods, choices, and tragedies emerge.

Featured image credit: Pirate flag, by LeslieAnneliese. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post The forgotten history of piracy in the Indian Ocean appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the month: Bertrand Russell

This June, the OUP Philosophy team honors Bertrand Russell (May 18, 1872 – February 2, 1970) as their Philosopher of the Month. Considered among the most distinguished philosophers of the 20th century, Russell’s style, wit, and contributions to a wide range of philosophical fields made him an influential figure in both academic and popular philosophy. Among his best known philosophical works, the History of Western Philosophy demonstrates the scope of Russell’s curiosity and understanding, and highlights the interrelation of seemingly disparate areas of philosophy.

His most influential work includes his defense of logicism (the view that mathematics is in some important sense reducible to logic), and his theories of definite descriptions and logical atomism. Along with Kurt Gödel, he is also regularly credited with being one of the most important logicians of the 20th century. Russell’s contributions to logic and the foundations of mathematics include his discovery of Russell’s paradox, his detailed development of logicism, his development of the theory of types, and his refining of the first-order predicate calculus.

Russell discovered the paradox that bears his name in 1901, while working on his Principles of Mathematics (1903). The paradox arises in connection with the set of all sets that are not members of themselves. Such a set, if it exists, will be a member of itself if and only if it is not a member of itself. The paradox is significant since, using classical logic, all sentences are entailed by a contradiction. Russell’s discovery thus prompted a large amount of work in logic, set theory, and the philosophy and foundations of mathematics.

Russell was the President of the Aristotelian Society, and along with G. E. Moore, is generally recognized as one of the founders of analytic philosophy. Among his most important philosophical contributions is his theory of descriptions, which distinguished between the logical and grammatical subject of propositions, and developed a theory of meaning which was able to avoid the popular view that the grammatical subjects of all meaningful propositions must refer to objects which in some sense exist.

Russell is remembered not only for his own outstanding philosophical achievements but also for the crucially important personal encouragement that he gave to his student Ludwig Wittgenstein, who might very well have abandoned philosophy had not Russell seen the importance of the Tractatus logico-philosophicus, which appeared in 1922 and for which Russell wrote a highly significant introduction. In later life Russell gradually withdrew from his logical studies, and then from his philosophical work, towards political concerns and, especially, dedication to the cause of nuclear disarmament. Awarded the Order of Merit in 1949 and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950, Russell remained a prominent public figure until his death at the age of ninety-seven.

Featured image: the Wren Library at Nevile’s Court of Trinity College. Photo by Cmglee. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Philosopher of the month: Bertrand Russell appeared first on OUPblog.

June 3, 2016

Lady Susan: “the most accomplished Coquette in England”

In anticipation of the new film adaptation of Jane Austen’s comedic epistolary novella, Lady Susan, this extract introduces the main character; the charming and flirtatious Lady Susan Vernon.

LETTER 4

Mr. De Courcy to Mrs. Vernon.

PARKLANDS.

My dear Sister

I congratulate you and Mr. Vernon on being about to receive into your family, the most accomplished Coquette in England. As a very distinguished Flirt, I have been always taught to consider her; but it has lately fallen in my way to hear some particulars of her conduct at Langford, which prove that she does not confine herself to that sort of honest flirtation which satisfies most people, but aspires to the more delicious gratification of making a whole family miserable. By her behaviour to Mr. Manwaring, she gave jealousy and wretchedness to his wife, and by her attentions to a young man previously attached to Mr. Manwaring’s sister, deprived an amiable girl of her Lover. I learnt all this from a Mr. Smith now in this neighbourhood– (I have dined with him at Hurst and Wilford)—who is just come from Langford, where he was a fortnight in the house with her Ladyship, and who is therefore well qualified to make the communication.

What a Woman she must be! I long to see her, and shall certainly accept your kind invitation, that I may form some idea of those bewitching powers which can do so much– engaging at the same time and in the same house the affections of two Men who were neither of them at liberty to bestow them– and all this without the charm of Youth. I am glad to find that Miss Vernon does not come with her Mother to Churchill, as she has not even Manners to recommend her, and according to Mr. Smith’s account, is equally dull and proud. Where Pride and Stupidity untie, there can be no dissimulation worthy notice, and Miss Vernon shall be consigned to unrelenting contempt; but by all that I can gather, Lady Susan possesses a degree of captivating Deceit which must be pleasing to witness and detect. I shall be with you very soon, and am

your affect. Brother R. De Courcy.

LETTER 6

Mrs. Vernon to Mr. De Courcy.

CHURCHILL.

Well my dear Reginald, I have seen this dangerous creature, and must give you some description of her, tho’ I hope you will soon be able to form your own judgement. She is really excessively pretty. However you may chuse to question the allurements of a Lady no longer young, I must for my own part declare that I have seldom seen so lovely a Woman as Lady Susan. She is delicately fair, with fine grey eyes and dark eyelashes; and from her appearance one would not supposed her more than five and twenty, tho’ she must in fact be ten years older. I was certainly not disposed to admire her, tho’ always hearing she was beautiful; but I cannot help feeling that she possesses an uncommon union of Symmetry, Brilliancy and Grace. Her address to me was so gentle, frank and even affectionate, that if I had not known how much she has always disliked me for marrying Mr. Vernon, and that we had never met before, I should have imagined her an attached friend. One is apt I believe to connect assurance of manner with coquetry, and to expect that an impudent address will necessarily attend an impudent mind; at least I was myself prepared for an improper degree of confidence in Lady Susan; but her Countenance is absolutely sweet, and her voice and manner winningly mild. I am sorry it is so, for what is this but Deceit? Unfortunately one knows her too well. She is clever and agreeable, has all that knowledge of the world which makes conversation easy, and talks very well, with a happy command of Language, which is too often used I beleive to make Black appear White. She has already almost persuaded me of her being warmly attached to her daughter, tho’ I have so long been convinced of the contrary. She speaks of her with so much tenderness and anxiety, lamenting so bitterly the neglect of her education, which she represents however as wholly unavoidable, that I am forced to recollect how many successive Springs her Ladyship spent in Town, while her daughter was left in Staffordshire to the care of servants or a Governess very little better, to prevent my beleiving whatever she says.

If her manners have so great an influence on my resentful heart, you may guess how much more strongly they operate on Mr. Vernon’s generous temper. I wish I could be as well satisfied as he is, that it was really her choice to leave Langford for Churchill; and if she had not staid three months there before she discovered that her friends’ manner of Living did not suit her situation or feelings, I might have believed that concern for the loss of such a Husband as Mr. Vernon, to whom her own behaviour was far from unexceptionable, might for a time make her wish for retirement. But I cannot forget the length of her visit to the Manwarings, and when I reflect on the different mode of Life which she led with them, from that to which she must not submit, I can only suppose that the wish of establishing her reputation by following, tho’ late, the path of propriety, occasioned her removed from a family where she must in reality have been particularly happy. Your friend Mr. Smith’s story however cannot be quite true, as she corresponds regularly with Mrs. Manwaring; at any rate it must be exaggerated; it is scarcely possible that two men should be so grossly deceived by her at once.

Yrs &c. Cath. Vernon.

Featured image: Chloe Sevigny and Kate Beckinsale in ‘Love and Friendship’. Roadside Attractions

The post Lady Susan: “the most accomplished Coquette in England” appeared first on OUPblog.

Bath salts in the emergency department

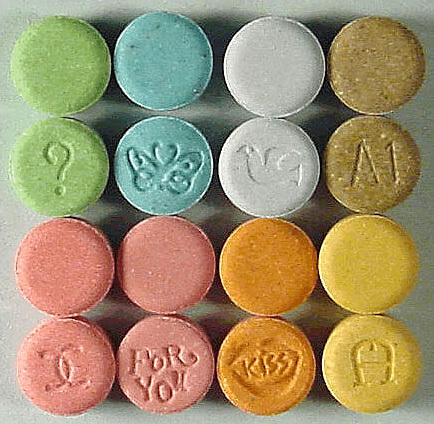

Psychosis, agitation, disorientation, or bizarre behavior due to drug ingestion is a common presentation to the emergency department (ED), and frequently psychiatry is consulted to assess for an underlying psychiatric illness. A working knowledge of how different substances are expected to affect patients is an important part of keeping up-to-date as a psychiatric emergency clinician. Thus it was particularly disturbing to learn from a recent NYU study that up to 40% of the “Molly” or “ecstasy” (common names for MDMA) consumed by club-goers in New York City may be contaminated with cathinone-derived substances, otherwise known as the dreaded “bath salts.”

Bath salts are synthetic stimulants which were previously legal in many states, undetectable by many drug urine screens and contain multiple compounds. They were labeled as “bath salts” and “not for human consumption” so that they could be sold legally in retail settings – most states have now banned them explicitly. MDMA, previously marketed as “ecstasy” is now more commonly sold as “Molly,” reputed to be purer and more effective than previous versions.

The study from NYU’s Department of Population Health consisted of two parts. First, an electronic survey was completed by 679 festival- or nightclub-attending 18-25 year-olds. The survey queried participants about demographic information, frequency of attendance at rave/dance party events and whether they had ever knowingly used any drugs from a provided list, which included 35 varieties of substances associated with “bath salts,” including Flakka, Mephedrone (“meow-meow”), “Ivory Wave,” and others. Then, they were asked to give a hair sample. Approximately 26% provided a sample. The majority of participants listed no lifetime use of bath salts. Of the participants who reported no lifetime use of “bath salts” or similar compounds, 41.2% tested positive for a bath salt-related compound. A positive test on hair sample was also associated with lower educational level and being from a racial minority; however, the strongest correlation was with frequency of attendance at these types of events.

Ecstasy pills by the Drug Enforcement Administration. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Ecstasy pills by the Drug Enforcement Administration. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.A few things about this study are particularly interesting. Bath salts have a very negative connotation in the media, associated with horrible outcomes such as severe violence, bizarre behavior, and cannibalism, although notably in the most publicly known case, no link was found. Molly is distributed as a powder and is perceived to be the “love-drug” that fosters interconnectedness and positive feelings. Aside from the profound irony that this population believed they were taking a drug intended to cause a happy, connected euphoria, but instead inadvertently ingested something reputed to turn people into zombies, we see two drugs that are supposed to have diametrically opposed effects on their users where the users had no idea what they were actually consuming even after the fact. The power of suggestion may be at play here.

What does this mean for psychiatric clinicians treating patients in the emergency department? Many drugs are not detected by routine urine toxicology in most hospitals or in pre-employment or legally-mandated surveillance drug screens (such as for people on probation or parole). In fact, part of the allure of synthetics such as MDMA, synthetic cannabinoids, Flakka, and bath salts is the ability of these compounds to avoid detection in typical urine drug screening tests for cannabis, opiates, cocaine, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates. Many screens can also test for phencyclidine (PCP) and amphetamines. However, there are exceptions even in standard screens: some synthetic opiates are missed, and phencyclidine screenings can cross-react with other substances such as dextromethorphan, or even the antiepileptic lamotrigine. Bath salts are largely cathinone-derivatives that have an entirely different chemical structure from typical amphetamines. Compounds synthesized in a lab can also be changed rapidly to avoid detection and have evolved over time, which makes producing a reliable screening test almost impossible. Because of the variety of the compounds, testing technology has not caught up.

In clinical practice, clinicians should be suspicious that any drug the patient reports to have consumed may be tainted with something else and should not rely entirely on urine or blood toxicology results to come to a diagnosis. Both MDMA and bath salts can cause adverse medical reactions such as hyperthermia, autonomic instability, electrolyte abnormalities and rhabdomyolysis, and death. Consequently, patients should be monitored carefully. ED presentations suspicious for toxic ingestion should be reported to local poison control, who can help monitor for trends and help direct public health efforts.

Featured image credit: People at a night club by stuv. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Bath salts in the emergency department appeared first on OUPblog.

Movement without touch: the life of Ian Waterman

When I first met Ian Waterman in the mid-1980s I could scarcely believe him. He claimed to have lost touch, and movement and position sense (termed proprioception) below the neck, though he could still feel pain and temperature, and his movement nerves were unaffected. Not only was I not aware of any such condition in medicine, but he had walked to the clinic and was sitting calmly as we chatted. How could his apparently normal functioning be reconciled with sensory loss which should have led to complete loss of coordination and useful movement? Tests soon showed his problem was exactly as he described it and, that when deprived of vision he was completely hopeless at moving, as expected. He had lost all automatic movement and was doing everything, instead, by attention to all aspects of movement, with vision to tell him his intentions had been successful.

For his part Ian hated doctors; he had had the condition 12 years by then and doctors had helped little. He viewed me, a young clinical neurophysiologist, with supreme suspicion. But then, having done the clinical thing, I sat down with him and asked just what it was like to live without touch and proprioception. No one had ever asked that before and Ian was intrigued.

That was the beginning of over 30 years’ collaboration. We’ve done research in labs across the United Kingdom, Europe, and the United States. It was soon clear how astute Ian was at judging research and researchers, so we do work with Ian never simply on him. He has also been the subject of a BBC documentary, been portrayed on stage, hung out with Oliver Sacks, and even flown in microgravity. Working together on the science, as well as spending long periods travelling and hanging out in hotels, restaurants, as well as the odd dive, has involved fun times as well as work. But his life has not been just research; he runs a successful business performing access audits for hotels, banks, trains, and hospitals—using his need for close attention towards movement in the built environment to his commercial advantage, as well as being the mastermind behind Pedigree Turkeys, which breeds rare types of turkeys and poultry. And he has been married three times.

Ian Waterman and Jonathan Cole at Ian’s wedding to Brenda. Used with permission.

Ian Waterman and Jonathan Cole at Ian’s wedding to Brenda. Used with permission.I wrote about his early years, learning to move again, escaping after 17 months in rehab and of his triumph over disability in 1991 in Pride and a Daily Marathon. But now, 25 years later, we wanted to explore living without touch and proprioception over four decades, as he turned 60 and as he has come to terms with his impairment in deeper ways. So we’ve sat and talked, digital recorder running, as we built up his reflections on a remarkable life. Despite living with the condition for 40 years, Ian is still as vulnerable as ever, and any reduction in mental effort towards movement, whether due to a head cold or the lights fusing, takes him back to stage one again.

We wanted to explore how the neuroscience was actually done and Ian’s contribution to the understanding of touch and proprioception. We also focussed on how he moved from being a passive participant to become an astute collaborator and even critic of neuroscience and neuroscientists. For Ian, neuroscience is not impersonal either but, rather, uncovers his tricks and strategies for living, especially when investigating his sense of intimacy without touch and his use of gesture without automatic movement.

Ian has also fascinated more than scientists. He has been a subject of vignettes in two Peter Brook plays and worked with magicians, philosophers, and choreographers—awakening them all to the importance of proprioception and its loss. To each and all, Ian has made himself available and answered questions as best he could.

We were keen to describe Ian’s life and his experiences not just during experiments but over decades. So often science dips in and leaves; living in a condition for years and decades gives a perspective and insights not to be found in shorter accounts. The great Russian neuropsychologist, Alexander Luria, did this in his narrative biographies and I have tried to do the same in my previous books on spinal cord injury and facial immobility. People live a long time with their conditions; the longer view and mature reflection are necessary, even essential, to understand how living successfully with an unusual condition evolves by subtle and creative means.

Featured image credit: touching by Paul J. Everett, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Movement without touch: the life of Ian Waterman appeared first on OUPblog.

Bird talk

“Women’s speech is always, in some sense, birdspeech, always, by virtue of gender, sub-human, other. It requires interpretation before we know what it means, and it places us on the margins of the main discourse.” (Jeanne de Montbaston/Lucy Allen).

For all its supposed isolation out there beyond the pale of acceptable discourse — marginal words in the mouths of marginal people — we know a good deal about slang. We know its lexis, and keep chasing down the new arrivals; we know its lexicographers, some very well; we know its speakers, and note that far from monosyllabic illiterates, they coin some of the most inventive usages currently on offer. We knows its preoccupations and that as a vocabulary it shows us not how we might like to be, but how we are: at our most human.

And above all, we know that it’s made and used by men.

At which, might I suggest a pause.

What happened to the women?

We know about women in slang: there isn’t even the usual sexist dichotomy, plenty of whores, whether literal or figurative, but mothers? Not really, since mother, when she does appear, is usually no more than abbreviation for a longer, far from savoury polysyllable. But what about woman and slang. Women as coiners, women as users? At which point we meet one of language’s most intriguing, but still unexplored questions: what is the relationship of women to slang? Do they use it, do they create it, and is ‘female’ slang different to the well-known ‘male’ version? It is an important question, and as yet, we have no answer. Girls and women’s position as sexual objects within mainstream slang has been well documented. What about them from the subject position, as language users and linguistic innovators.

As a slang lexicographer I have long espoused the men-only theory. I am no longer so sure. Because women have always used slang, both between themselves and in conversation with men. That the themes of this slang have been seen as male-generated does not diminish this truth. In addition, thanks to the online world in general and specifically that of social media, there continues to develop a type of all-female slang focused on themes that concern girls and women. A development that represents a new, even revolutionary change in the way we speak.

Coarse, obscene, confrontational: mainstream slang militates against the traditional stereotypes of ‘femininity’. Its sexism is innate and unavoidable. Yet slang ought to be a woman’s ally. On the margins of standard language, it rebels against linguistic norms. If, in social terms, women have been and still are a marginal group, slang would seem to provide an outlet for challenging restrictive social norms.

Slang is not seen as ‘talking proper’. Similarly, as recent media discussions show, allegedly female speech patterns such as ‘vocal fry’, ‘up-talk’, and tag-questions are seen as similarly ‘improper’. Like slang, regularly seen as the cause of social failings such as the inability to tackle job interviews, speech patterns such as ‘up-talk’ are paraded as causes of professional inequality for young women. Slang disadvantages its users; so too, it is claimed, does ‘talking like a woman’.

Leisure and Entertainment during the First World War. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Leisure and Entertainment during the First World War. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.This debate on the ‘policing’ of women’s use of language is hardly new: in 1777, Lord Chesterfield upheld the common stereotype of women’s talkativeness, describing their use of language as ‘promiscuous’ and without regard for grammatical propriety. Women were over-experimental, blithely inventing new meanings for words. In contrast, the linguist Otto Jespersen in 1922 claimed that women’s vocabulary was poorer than men’s, and that female speakers were much more careful and polite. Both deviated from a male ‘norm ’.

In 1975 Robin Lakoff presented her theory on ‘Women’s Language’: it included politeness, hesitation and hedging, and a richer vocabulary for typically ‘female’ fields (e.g. colours). The idea of distinct ‘men’s’ and ‘women’s languages’ continues to flourish in popular media, in spite of having been debunked by research.

Researching women’s slang encounters problems that have accompany any slang research, but even more so. If slang in general is marooned beyond mainstream speech and thus hard to track down, then the female version has proved even more elusive. Yet there are a wide range of possible sources, among them: dictionaries, literary sources, research in anthropology and sociolinguistics, historical corpora, scripts of TV and movies and the output of social media.

Once one starts looking, historical representations of female slang users are not hard to find. Moll Frith, as depicted in Middleton’s Roaring Girl in 1611, is a devotee of cant or criminal slang. The 18th century slang subset ‘flash’ was acknowledged as finding its home at Moll King’s celebrated coffee house in Covent Garden. In late 19th century New York the show people of Helen Green’s fictional ‘Maison de Shine’ were all vociferously slangy, irrespective of their gender. It has been noted that while military slang in World War I basically consisted of the word ‘fuck’, such terminology palled in comparison with the language of the average textile factory of the era. The factory girls neither blocked their ears, nor shut their mouths. Some of the most slang-laden (not to mention sizzlingly obscene) blues lyrics came from women such as Louise Bogan and Bessie Smith. Examples are legion and only increase with the passage of time.

Whether women coined slang terms is harder to discern. Slang research rarely notes the speakers’ gender. The assumption, as with Standard English, is of a male norm, but assumption is not proof and we should not fall into the fantasy that slang is not ‘ladylike’. Or perhaps it is, if one looks at slang’s definitions of ‘lady’.

Finally, as elsewhere, technological developments have opened new possibilities. The world of social media, unfettered by traditional gatekeepers, has seemingly become a playground for female language users. Female-dominated web sites such as Mumsnet, for instance, have evolved their own non-standard vocabulary. The potential is unrevealed, but the traditionally male-orientated balance of power as regards slang may be changing.

Featured image credit: ‘Photobooth strip of a woman and friend’, by simpleinsomnia. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Bird talk appeared first on OUPblog.

June 2, 2016

Artificial Intelligence – Episode 35 – The Oxford Comment

Imagine a world where the majority of our workforce was composed of robots as capable and as psychologically similar to human beings. The robots are constantly working and are faster and more efficient than humans—leaving humans to be pushed towards early retirement to enjoy a life of leisure and wealth due to a large growth in investments on this artificial intelligence (AI). But don’t get too excited about this luxurious idea just yet—Robin Hanson, author of The Age of Em, cautions that this may not be a reality for another few decades.

So what does currently exist in the development of AI today? Our multimedia producer Sara Levine chats with Robin Hanson; Robert Repino, an editor in OUP’s Reference Department and author of Mort(e) from SoHo Press; Maggie Boden, author of AI: Its Nature and Future; and Steve Furber, Editor-in-Chief of The Computer Journal this month on The Oxford Comment to find out. Together, they explore the dichotomy between what is expected of artificial intelligence in the future and what is actually happening in the field today—including the use of AI to solve climate change and disease diagnosis issues and to provide us with better insight into the human mind.

Featured image credit: “Robot Eye” by thehorriblejoke. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Artificial Intelligence – Episode 35 – The Oxford Comment appeared first on OUPblog.

Left behind? The future of progressive politics

Centre-left social democratic parties appear to have been left behind in the last decade. ‘‘Early in this century you could drive from Inverness in Scotland to Vilnius in Lithuania without crossing a country governed by the right,’’ The Economist highlighted just weeks ago, ‘‘the same would have been true if you had done the trip by ferry through Scandinavia. Social democrats ran the European Commission and vied for primacy in the European Parliament.’’ But recently their share of the vote has plunged- they have been ‘left behind.’

The challenge for anyone thinking about the future of social democracy is that we no longer have a vocabulary of politics that resonates with the broader public sphere. Even the title of this little piece – ‘Left Behind?’ – embraces an arguably tired and prosaic attachment to a notion of politics that remains tied to a ‘left-right’ spectrum. One might argue whether this ‘spectrum approach’ was ever really capable of grasping the subtle complexities of political life – either at the personal, party, organizational, or social level – let alone the innate irrationalities of political life itself with its inevitable mixture of messiness and compromise. A ‘new political project’ from this perspective might focus not simply on the concept of ‘the centre left’ but on the very nature of collective politics itself. This ‘new approach’ offers huge potential in terms of redefining and revitalising democratic politics – a rejection of the defensive and callowed version of social democracy that currently exists in the wake of the global financial crisis.

The simple argument here is that any starting point in a discussion about revitalizing politics – and therefore society – cannot be rooted in conceptions of either ‘the left’ or ‘the right’ (or ‘the centre’). Such historical signposts are now too crude to grasp the social complexity that defines the twenty-first century. The research of Jonathan Wheatley, for example, suggests that the terms ‘left’ and ‘right’ are of little relevance to the contemporary electorate. “Evidently, left and right are amorphous concepts that mean different things to different people at different times’’, Wheatley notes, “Amongst younger, less well-educated and especially less politically interested users, items belonging to the economic scale were barely coherent at all. For these voters, the notions of ‘left’ and ‘right’, at least in economic terms, are really not meaningful at all”. The electoral basis of democracy therefore needs to be accepted not only in terms of its complexity but also in terms of the decline of monolithic class groups, the re-scaling of economic activity, combined with a shift towards single-issue or valence politics. The rise of political complexity therefore reflects a broader increase in social complexity.

If I were being provocative I might dare to suggest that, at one level, there was no such thing as ‘the public’ because as any politician (or impact-engaged academic) knows there are in fact ‘multiple publics with whom it is necessary to engage in multiple ways.’ This argument may have academic roots (in this case it’s Michael Burawoy’s work on public sociology) but in many ways it speaks to the challenges faced by thinkers, scholars, politicians, and policy-makers who aim to craft a new political project for what really are ‘new times.’ The challenge for any of the ‘mainstream’ political parties – or for any of the new ‘insurgent’ parties – is to learn how to engage with multiple audiences in multiple ways with a message that has resonance and meaning while also being accessible. From this perspective the ‘traditional’ parties too often appear like dinosaurs wandering aimlessly across the political savannah who don’t really understand where they are going and why. The terrain, the savannah, has become more complex and yet the beasts remain incredibly cumbersome with their committees, conferences, headquarters and desiderata of an arguably earlier political age. The elements of this increased complexity are diverse, contested, and inter-related (social media, increased public expectations, individualization, migration, etc.) but they culminate in a well-known focus on ‘the problem of democracy’ with its ‘disaffected democrats’ and ‘critical citizens.’ (The irony for the Labour Party is that, as Andrew Gamble has argued, ‘the Corbyn effect’ was fuelled by anti-politics and populist sentiment within an established political party.)

One way of thinking about this problem – and possibly a solution – is to think of Zygmunt Bauman’s work on ‘liquid modernity’, which when stripped down to its core components, emphasizes the decline in traditional social anchorage points (jobs for life, national identity, religion, marriage, close knit communities, trade unions, etc.). All that was once solid has apparently melted away and has been replaced with a hyper-materialism that ultimately leaves the public(s) frustrated. To make such an argument is to step back to C Wright Mills classic The Sociological Imagination (1959) and his arguments about ‘the promise’ and ‘the trap.’ We have identified a perceived trap in the form of the decline of the centre left and the dominance of market logic across and within social relationships. But where is ‘the promise’ in terms of a new vision possibly inspired by the insights of the social sciences that cuts across traditional partisan lines?

Politicians make promises but the public no longer perceives that these promises are ever delivered, or fail to understand exactly why – as Bernard Crick argued – democratic politics tends to be so messy. Politicians have no simple solutions to complex problems and nor do I. And yet, as a way of generating a discussion, I would suggest that ‘the promise’ of social democratic politics will only be achieved when three elements are secured:

A Clarity in terms of not only a stable vision of why ‘working together’ through collective endeavours matters but also in terms of how it can provide meaning, , control and choice;

A Confidence in terms of a positive political narrative that inspires belief and hope, and redefines specific ‘threats’ as opportunities; and,

A clear and confident ‘language of politics’ that is not defensive or defined by the past, that makes no mention of Guild Socialism, Golden Ages, Fabianism, Richard Crossman, ‘Lefts’ and ‘rights’, etc.

The challenge for the Labour Party in 2020 already looks greater than it did in 2015, not least because the party too often appears engulfed in (internal) tribalism within an increasingly post-tribal world. The challenge for a future political leader is to reject and re-frame the dominant anti-political sentiment for the simple reason that it is rarely anti-political in nature and more accurately interpreted as frustration with the current system. Redefining ‘anti-politics’ as ‘pro-a-different-way-of-doing-politics’ lies at the heart of any new political project that seeks not to be left behind.

Featured image credit: direction road look by aitoff. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Left behind? The future of progressive politics appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers