Oxford University Press's Blog, page 502

June 8, 2016

Leaving the kennel, or a farewell to dogs

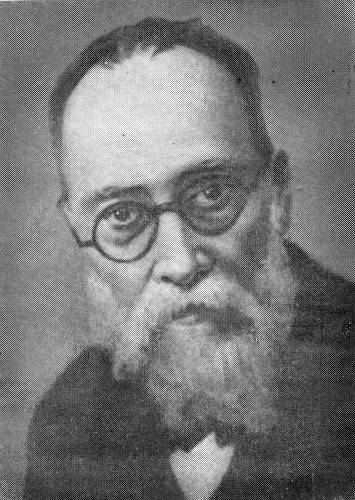

My series on the etymology of dog and other nouns with canine roots has come to an end, but, before turning to another subject, I would like to say a few moderately famous last words. For some reason, it is, as already mentioned, just the names of the dog that are particularly obscure in many languages (the same holds for bitch and others). The great historical linguist Antoine Meillet once wrote that all attempts to reconstruct the origin of Latin canis are futile. Meillet was prone to pontificating and shedding discouraging words of wisdom. Thus, more than a century ago, he observed that all the good etymologies had already been found, while all the new ones were bad. Since I pride myself on offering three, perhaps even four new convincing etymologies, I feel slighted. However, as regards canis, he may have been right. Trouble arises even when everything appears to be clear. Consider greyhound. It is of course a compound. The first element is related to Old Icelandic grey “bitch,” a noun of undiscovered origin. The idea that grey here is a color word does not inspire confidence.

Antoine Meillet is much better known than August Pott (and deservedly so), but, unlike Pott, he left us little hope.

Antoine Meillet is much better known than August Pott (and deservedly so), but, unlike Pott, he left us little hope.The situation with canis and grey is typical. Germanic hund-, whether allied to canis or not, is, to us, an arbitrary coinage, for we cannot explain its initial meaning. Likewise, the origin of Spanish perro “dog,” an orphan of the Romance languages, remains a notorious puzzle. Similar riddles torment language historians in Slavic. East Slavic sobaka (stress on the second syllable), discussed at some length before, is explained in our most reliable dictionaries as a borrowing from Iranian, but O. N. Turbachev, who for decades was the editor of and the main contributor to a Common Slavic etymological dictionary, as well as the author of a book on the names of domestics animals in the Slavic languages, pointed out that this derivation has little to recommend it and preferred to search for the word’s source in Turkic, though he formulated his hypothesis with utmost caution. To repeat what I said in an earlier post, one wonders why any community should have taken over the name of the most common domestic animal from its neighbors. Apparently, when the word made its way to the Slavs (assuming that sobaka was indeed a borrowing), it was not a mere generic term. Russian kobel’ “castrated dog” (stress again on the second syllable), a word I also mentioned in one of the posts of the series, is equally obscure, and so is pes (pronounced as pyos), the Common Slavic word for “a (male) dog.”

The story of pes (pyos) made me return to Meillet’s cruel dictum. It happened because I have read with great interest a 1993 article by Hans-Jürgen Sasse about the dog’s name kut or kuch, current in the Mediterranean region, all over Eastern Europe, in Finno-Ugric, Indo-Iranian, Semitic, and even in some American Indian and aboriginal Australian languages. German Köter “stray dog” and Hungarian kutya “dog” apparently belong with kut ~ kuch. In some places, kut and its phonetic variants are used as a call to dogs and cats. Among the forms, we find kuta(k), guda(g), guda, and gudaga, the latter sometimes being shortened to dog (!). Kutya–kutyu “pup” and kutyityi “baby animal,” along with tjutju “dog,” have also been attested.

A first approach to global etymology.

A first approach to global etymology.No clarity has been achieved in trying to account for the world-wide spread of kut and its analogs in naming dogs and cats. A case of parallel formation in the spirit of Wilhelm Oehl (the hero of an old post on the word butterfly) or the result of dissemination? Kut is not the only common favorite, and this is where Slavic comes into play. The group psps, which we half- recognize in Engl. pussy, is a near universal call to cats. In Modern Greek, the baby word for “cat” is psipsina, and when I saw psipsina, I immediately thought of Russian pyos. Is it possible that all the learned conjectures about pyos are useless and that pyos is a baby word, like pussy? One of my animal series was devoted to fox (“Vulpes vulpes”). In Part 2, I told a story about a girl who listened patiently to her mother’s explanation about the mechanics of street cars (electricity, wires, rails, and so forth) and said: “No, this is not the way they go.” “And how do they go?” asked the woman in surprise. “Ding-dong,” replied the innocent child. I called this type of approach to word history ding-dong etymology. One should not fall for this type of etymologizing with too much readiness, but in some cases it probably works. Is pyos a baby word for “doggie”? We’ll never know, but it may not be entirely unprofitable to have this solution in the back of our collective mind. After all, the street car does go ding-dong, even if this fact cannot be incorporated into a manual of electrical engineering.

The French return to their sheep. I will return to the English word dog. Rather probably, it is a baby word, a “syllable” of the same type as kut and puss, but, unlike those, distributed over a small area: English and a few dialects of German. It will be remembered that the first occurrence of dog in English goes back to the middle of the eleventh century and that it surfaced in the glosses as a term of abuse. Curiously, Spanish perro was first recorded in 1136 and also as low slang with a pejorative sense. Everybody knows that dog is still a term of abuse, with examples going far beyond facetious statements like oh, you lazy dog. Derogatory senses are all over the place. Skeat attempted to derive dog cheap from Swedish (without success, in my opinion). All kinds of plants believed to be spurious have names beginning with with dog. Incidentally, Dog Latin is spurious (or mongrel) Latin. The same contemptuous implication can be easily detected in the fourteenth-century noun doggerel. Going to the dogs denotes the utmost state of deterioration. How did the dog, the most faithful animal that has followed humans from time immemorial, get such a devastatingly bad press?

Since in this series I have ventured so many hypotheses, none of which will probably be accepted, I will offer one more. Perhaps dog was an even looser term than the one I risked reconstructing in the previous post devoted to dogs. It might have been a baby word for a toy, an animal, and a bugaboo. Very small children typically use the same monosyllables for the most various objects surrounding them. Dog, I think, emerged as a unit, combining such almost irreconcilable senses as “a favorite pet” (“puppy,” if you want another baby word), “a frightening animal,” and “some toy; doll.” It entered adults’ slang with at least two of those senses (“domestic animal” and “bugaboo”) but first turned up in our oldest texts, by chance of course, as a term of abuse. The existence of stacga “stag,” frocga “frog,” and the like allowed it to survive as an animal name, but the deprecatory sense did not go away either. To be sure, in other langauges the word for “dog” also has a pejorative sense (for instance, Hund in German,” though Engl. hound is just an animal name). However, it is hardly ever as widespread as in English.

Despite all the abuse people heap on their most faithful pet, dogs were venerated and even deified all over the ancient world.

Despite all the abuse people heap on their most faithful pet, dogs were venerated and even deified all over the ancient world.My work with the etymology of short English words, especially such as begin with and end in b, d, g (and sometimes p, t, k), for instance, bug, bog, big, bad, bed, dig, pig, and even god, invariably results in the discovery of onomatopoeia, expressive and symbolic formations, and baby talk. I have a strong suspicion that dog is part of that group. A look at a larger picture will also show that the origin of dog is not radically different from that of tyke, bitch, and cub, discussed in this series. The sphinx, her part animal nature notwithstanding, may be (to quote Oscar Wilde) without a riddle.

Featured image: Dogs by Ulrike Mai, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Leaving the kennel, or a farewell to dogs appeared first on OUPblog.

The classics and the Constitution: The smokescreen of republicanism and the creation of the Republic

What role did the Greek and Roman classics play in the making of the American Constitution? Existing scholarship has put the main emphasis on the political theory of republicanism. In his 1969 book The Creation of the American Republic 1776-1787, Gordon Wood described a shift from classical republicanism to a more democratic post-Constitution Republic. In the 1998 edition, Wood points out that his book had been pulled into the vortex of the debate about the role of republicanism that followed in the wake of Bernard Bailyn’s 1967 Ideological Origins of the American Revolution and J. G. A. Pocock’s 1975 Machiavellian Moment. In 1998, Wood writes that he may have pictured 18th-century American republicanism as too “severely” classical, and he now seeks to soften the opposition between republicanism and democratic liberalism.

Wood now acknowledges that 18th-century republicanism was more Lockean than he had allowed. It was a “modernized” republicanism, which in its “updated” version was less anti-commercial and more liberal. What had originally drawn communitarian philosophers and legal theorists to Creation, namely the prospect of an anti-commercial alternative to Louis Hartz’s interpretation of the Founding, turns out to be no such thing—Wood’s 1998 republicanism suddenly looks a lot more Hartzian than it did in 1969.

However, even in his recent work, Wood holds on to his original interpretation of John Adams—a holdout who even after 1787 kept talking about politics as a classical republican. Adams thus emerges as a striking exception, an oddity out of step with the spirit of the increasingly democratic United States.

But there is a problem with the very concept of classical republicanism. There was never a coherent tradition of Greco-Roman republicanism in the sense Pocock, Wood, and their followers have argued. Aristotle was indeed singularly concerned with virtue in his political theory—but this is because he viewed the state as an educational machine designed to enable men to be virtuous and lead the good life. Machiavelli also focused on virtue—because he considered (martial) virtue the means to expand the republic and achieve glory. For Aristotle, the polis is an instrument to achieve virtue and the good life. For Machiavelli, virtue is an instrument to achieve glory and political success.

Finding an explanation for and a remedy to the collapse of the Roman Republic was of crucial importance to the American Founders. Apart from the English constitution, which was interpreted as a republic in disguise, there was no more consequential model than the Roman Republic. The Roman writers of the last century BCE who witnessed the Republic’s collapse had diverging explanations for the breakdown. Some, such as Sallust, put forward the idea that luxury and the corruption of virtue were responsible for the Republic’s demise. This is the view that is commonly captured with the term “classical republicanism.”

“…the Federalist and [John] Adams relied on a long tradition of writers, from Cicero to Jean Bodin to Trenchard and Gordon to Montesquieu, who were fascinated by the crisis of the Roman Republic…” The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, as Agreed upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787. In Two Volumes. (1st ed.) This copy is from the Rare Books and Special Collections Division of the Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“…the Federalist and [John] Adams relied on a long tradition of writers, from Cicero to Jean Bodin to Trenchard and Gordon to Montesquieu, who were fascinated by the crisis of the Roman Republic…” The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, as Agreed upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787. In Two Volumes. (1st ed.) This copy is from the Rare Books and Special Collections Division of the Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.But there had always been a competing, no less influential interpretation: according to Cicero, John Adams, and many others, the crisis of the Republic was a constitutional crisis, and an explicit constitutionalism could have provided its remedy. This tradition focused on an institutional analysis of the fall of the Republic in juridical and especially constitutional terms.

Neither Adams nor the authors of the Federalist Papers were classical republicans in either the Aristotelian, Sallustian, or Machiavellian sense of the term. In a way you could say, therefore, that the political theory of the Constitution and the ratification debates left classical republicanism behind. But the Federalist and Adams relied on a long tradition of writers, from Cicero to Jean Bodin to Trenchard and Gordon to Montesquieu, who were fascinated by the crisis of the Roman Republic and who drew similar conclusions from its fall—namely, that virtue could not be relied upon for stable government, and that the solution would have to be institutional.

The solution, they thought, should be sought in what the Founders called a “compounded republic.” Virtue and self-denial, by contrast, were considered “cant-words” (Cato’s Letters). Adams agreed: it was “by no means” luxury or ambition which had brought down the Roman Republic, but lack of constitutional entrenchment and the usurpation of constitutional rights. Adams very much doubted that “any people ever existed who loved the public better than themselves,” and he based his Ciceronian constitutionalism on an Epicurean political psychology (borrowed from Polybius, Cicero himself, or Hobbes).

Cicero and Livy had shown that the seeds of this constitutional solution could already be found in the Roman Republic. The history of the Republic was littered with legal arguments contesting the validity of laws and the actions of magistrates, and these arguments hinged on a distinction between legislation (leges) and higher-order, entrenched constitutional law (ius). Cicero turned this inchoate constitutionalism into an explicit constitutional program.

Bodin, the Commonwealthmen, and Montesquieu drew on this tradition of Roman constitutional thought. It was this set of ideas, developed as a remedy against the demise of republican government and military despotism, which the Federalist proponents of central government, constitutional checks, and a bicameral legislature applied when they debated the Constitution in 1787-88.

The fascination of the Founders with the fate of the Roman Republic has often been written about, but the smokescreen of “classical republicanism” has obscured the crucial differences between those, writing in a Sallustian vein, who were interested in virtue, and those, following Cicero, who discounted virtue and thought that constitutionalism was the remedy to republican decay. The novelty of the constitution-making in the States and at Philadelphia can therefore be seen, paradoxically, in its application of ideas drawn from the collapse of an ancient political order.

Featured image: “Scene at the signing of the Constitution of the United States” by Howard Chandler Christy, 1940. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The classics and the Constitution: The smokescreen of republicanism and the creation of the Republic appeared first on OUPblog.

June 7, 2016

Revealing lives of women in science and technology: the case of Sarah Guppy

The most recent update to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB) adds 93 new biographies, including 18 of women. At just under 20% of the total this is higher than for the Dictionary as a whole (11%, rising to 19.3% for those born after 1840) and reflects long-term changes in historical research. The media response – in particular to the biography of Sarah Guppy (1770-1852) – has also been revealing.

Guppy, as a patent-holding female inventor, is a rare type for the early 19th century but one that we are clearly eager to hear about today. It is the kind of life that (mostly women) historians have been researching since the 1970s and, more recently, has been transformed into popular role model: the archetypical example is Ada Lovelace, whose name has been adopted for a day celebrating and encouraging women in science and technology. It is interesting to note, though, just what we do and don’t want to know about Guppy and women like her. Comparing the carefully compiled ODNB entry by Madge Dresser with other accounts reveals much about how we put past lives to use today.

It is not surprising that recent newspaper reports (e.g. Telegraph, Independent and Bristol Post) have latched onto Guppy’s 1811 patent as something particularly atypical and worth celebrating: a big engineering project. Her patent was for a method of “erecting and constructing bridges and rail-roads without arches or sterlings, whereby the danger of being washed away by floods is avoided” – a chain-suspended bridge. This was, she believed, a potential solution to the long-discussed problem of erecting a bridge over the Avon.

Some articles extrapolate from this, and from the fact that Guppy was an advocate for and investor in what was to become the Clifton Suspension Bridge, that she rather than Isambard Kingdom Brunel was the bridge’s true designer. It’s a great headline, playing into a cherished narrative of unsung heroes, overlooked women and unfairly neglected contributors to science and technology. In fact, it is somewhat misleading regarding the nature of Guppy’s contribution and also privileges one part of her life over its many other aspects.

Menai Bridge, Wales, by Ton 1959. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Menai Bridge, Wales, by Ton 1959. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Guppy did not design the Clifton Suspension Bridge, although she could, and did, claim credit for significant input on the design of Thomas Telford’s Menai Bridge (New South Wales, completed 1826). It was later reported that she had waived fees for Telford’s use of her ideas, claiming her chief concern was public benefit over personal profit. Her role in the Clifton Bridge is less clear, although she was said to have made models for Brunel and he does seem to have used principles outlined in Guppy’s 1811 patent in his 1830s design.

The Sarah Guppy we find in these articles and earlier accounts on the internet (Wikipedia, Intriguing History, Amazing Women in History), in books and on TV is, above all, an inventor and engineer. As well as the bridge design, they note her other patents, although there is perhaps less interest in these mostly domestic innovations. Adam Hart Davis is one who rather condescendingly took these to indicate that she was “not desperately serious”. There is, however, near silence on Guppy’s apparently more conventional female activities, centred on education and philanthropy.

Although in 1845 she was described as “a lady favourably known for her scientific attainments”, Guppy probably saw herself as a woman of letters and benefactor. Her inventions were very much of a piece with the pamphlets and correspondence in which she presented schemes relating to a wide range of issues, including roads, animal welfare, public health, education, agriculture and horticulture. She also wrote a book for children, founded a charity school for girls, and took an interest in the physical and moral welfare of vulnerable groups, from widows to retired seamen and female servants.

Something discussed in the ODNB article, but which does not fit the budding heroine narrative presented elsewhere, is Guppy’s views on the last of these. She was a patron and founder member of the tellingly named Society for the Reward and Encouragement of Virtuous, Faithful, and Industrious Female Servants, and her pamphlet was chiefly concerned with the lack of virtue – indeed “depravity” – that she believed to be rife amongst them. Her suggested remedy was partly that mistresses should carefully counsel these young, uneducated girls and women, but also that their wages should be reduced – an awkward fact for those who would like to recruit her for feminism today.

By focusing on the whole life, instead of trying to fit rediscovered figures into pre-existing moulds shaped around the fables of heroic male inventors, we can learn much more. We can see how scientific or technical work could fit into past lives, often in ways and with motivations that we would now find unexpected. We also find that talent and hard work were never enough but that Guppy and others required support networks and financial backing. Such knowledge will help us find more and other lives in the historic record – and remind us that this essential support is still often lacking today.

The post Revealing lives of women in science and technology: the case of Sarah Guppy appeared first on OUPblog.

Oncolytic virus approved to treat melanoma

Cancer cells have a unique vulnerability: the same mechanisms that shield them from the immune system also make them prone to viral infections. Scientists have long tried to exploit that vulnerability by developing viruses that will infect and replicate in cancer cells until the cells burst, releasing virally infected particles into the bloodstream. Ideally, those particles will then generate a systemic immune reaction against cancer cells.

Those efforts hit a milestone last fall when the US Food and Drug Administration approved Talimogene laherparepvec (T-Vec) for melanoma treatment. A modified form of the herpes simplex type 1 virus, T-Vec is the first oncolytic virus to reach the market. In a multicenter phase III study, 26% of 291 treated patients with stage IIIB–IV disease had an objective response to the virus. In more than half those cases, responses lasted at least six months. Complete responses were achieved in nearly 11% of treated patients, and treatment lengthened overall survival to a median of 23.3 months, compared with 18.0 months among control subjects who took the endogenous immune stimulator granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor.

T-Vec has received a favorable opinion in Europe, where regulatory approval is now pending. Unlike Food and Drug Administration approval, which applies to melanoma of all stages, European approval will probably be limited to stage 3 and 4M1a—tumors of the skin and lymph nodes.

James Gulley, MD, PhD, head of the immunotherapy section at the National Cancer Institute, said T-Vec has the potential to become a powerful therapeutic tool.

“We need new and better ways to turn T cells against cancer, and that’s what T-Vec appears to do,” he said.

But Gulley said that T-Vec’s greatest benefits will probably be achieved in combined treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as ipilumumab, a CTLA-4 inhibitor, and pembrolizumab, an anti–PD-1 agent.

Long Road to Market

T-Vec’s approval follows a long struggle in oncolytic virus development. According to Brian Lichty, PhD, immunologist and professor at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, earlier viruses were so weakened for safety that they didn’t work well, and negative results tarnished the field. By contrast, scientists engineered T-Vec with just two gene deletions: the ICP47 gene, which shields the virus from the immune system, and ICP34.5, which might otherwise facilitate neurological infections in immunocompromised patients.

To maximize exposure, clinicians inject T-Vec directly into melanoma growths on the skin. Treatments start with a minimal dose intended to prime the immune system without unleashing a dangerous antiviral reaction. Then they advance to larger doses given every two weeks until the lesions disappear or until patients shows signs of clinical progression. As with all immunotherapies, the lesions can grow before they shrink, reflecting an influx of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. According to Yvonne Saenger, MD, director of melanoma immunotherapy at New York Presbyterian Hospital’s Columbia Campus, patients often feel minor flu symptoms after treatment, such as low-grade fever, chills, and muscle aches. The advantage, she said, is that T-Vec stimulates local immune reactions within the tumor itself, which otherwise tends to be immunosuppressive.

Injection by PhotoLizM. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Injection by PhotoLizM. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Delivering the treatments can be challenging, added Saenger, who was a principal investigator on the phase II and III clinical trials.

“T-Vec is a live virus, so there are issues and potential complications to consider,” she said. “Nurses can be reluctant to handle it, and should never do so if pregnant, and you need to keep it away from people who are very immune compromised, such as bone marrow transplant patients.”

But Howard Kaufman, MD, chief of the surgical oncology division at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, NJ, said that with proper guidance, clinical staff can learn to manage injection sites and minimize infection risks.

“We haven’t heard of a single report of household transmission,” he said. “But it will take some focused education before the average practitioner in the oncology community feels comfortable using it.”

The best treatment candidates, said Kaufman, T-Vec’s global principal investigator, are those with advanced local disease rather than widespread visceral metastases. T-Vec does appear to have systemic benefits extending beyond treated lesions. During the phase III trial, 15% of visceral metastases shrank by more than half, even though they hadn’t been injected.

“That T-Vec induces regression in peripheral, noninjected lesions makes it superior to other injectable treatments for melanoma that only shrink the injected lesions,” Saenger said.

Citing evidence from retrospective data, Kaufman added that T-Vec treatment appears to delay the onset of metastases, in turn allowing patients to delay systemic therapy. Durable responses are more pronounced in treatment-naive patients, Kaufman said, than in patients receiving T-Vec as second-line therapy. According to Kaufman, other good candidates for T-Vec include elderly patients who don’t tolerate checkpoint inhibitors, in addition to patients with head-and-neck melanoma.

Meanwhile, preliminary results from combination trials with checkpoint inhibitors look promising. At last June’s American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting, investigators reported results from a phase Ib trial with 19 patients given T-Vec with ipilimumab. The objective response rate was 56%, with 44% of treated patients having durable responses. A phase II study has been launched and has reached its target of accruing 200 patients.

At last September’s European Cancer Congress, investigators reported preliminary safety findings from a phase Ib trial combining T-Vec with pembrolizumab. Georgina Long, PhD, associate professor at Australia’s University of Sydney and the trial’s principal investigator, said the treatment was well tolerated with no observations of dose-limiting toxic effects. Efficacy results for the combination have not yet been reported.

Saenger said that T-Vec’s future in melanoma probably hinges on efficacy results from combination trials.

“T-Vec’s strength is that it’s a pathogen that works by a completely different mechanism than checkpoint inhibition,” she said. “Yet its role in melanoma treatment has yet to be fully established. If it adds to anti–PD-1 treatment, which is currently the favored approach in melanoma immunotherapy then I anticipate it will be widely used. If not, I would expect to see it in well-defined clinical contexts, but perhaps not as the dominant therapy.”

A version of this article originally appeared in the Journal of the Nation Cancer Institute.

Featured image credit: Metastatic Melanoma Cells by Julio C. Valencia. Image released by the National Cancer Institute. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Oncolytic virus approved to treat melanoma appeared first on OUPblog.

Filling the void: the Brexit effect on employment law

Having been cast as unnecessary “red tape”, a burden on business, inflexible, uncompetitive and inefficient, it is widely assumed that a sizeable number of domestic employment laws derived from European Law will be in the firing line in the event of a Brexit. In a well-publicised written opinion produced for the TUC, the leading labour law barrister, Michael Ford QC, has provided some support for this assumption. He noted the vulnerability of these EU-derived employment rights and labour laws, and divided and categorised them according to whether a future UK government would be likely to repeal, dilute or preserve them. In this blog, I will probe what might fill any void created by the removal of employment rights rooted in EU law. Surprisingly, the common law would appear to have as significant a role to play as domestic legislation in this context. The potential involvement of the common law is somewhat paradoxical, particularly in light of its perceived ‘undemocratic’ credentials, it being a source of law crafted incrementally by unelected judges.

Turning to the legislation listed in the ‘repeal’ camp, the understanding is that statutory rights to information and consultation on collective redundancies are liable to removal. These rights afford trade union or employee representatives the right to be informed and consulted about managerial proposals to effect redundancies of more than 20 employees in any period of 90 days or less. The effect of any repeal of these provisions is likely to be partial, which can be ascribed to the domestic ‘unfair redundancy’ protections provided to employees on an individual basis pursuant to Part XI of the Employment Rights Act 1996 (ERA). These pre-date the accession of the UK to the European Economic Community in the early 1970s. It is a fundamental part of any fair and proper pre-redundancy process that the employer engages in consultation with employees provisionally earmarked for redundancy on an individual basis: a failure to do so will very likely render any dismissal for the reason of redundancy unfair under Part XI of the ERA, enabling an employee to secure compensation. As such, the notion that employees will no longer have any entitlement to be consulted about proposed redundancies is inaccurate, since domestic law will step into the breach.

Another piece of legislation that Michael Ford QC identifies as ripe for repeal is the Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulations 2006 (SI 2006/246) (TUPE). This is rooted in the European Acquired Rights Directive 2001, which is designed to protect employees from dismissal or variations of their contractual terms in the event of a change of identity of their employer, e.g. on a sale of the business and assets of the employer to a third party, or an outsourcing situation. I am slightly more sceptical about the prospect of a UK Government repealing TUPE than some other commentators, despite the lack of enthusiasm of employers and the Government for such provisions. It is more likely that particular provisions will be cherry-picked and done away with.

Surprisingly, the common law would appear to have as significant a role to play as domestic legislation in this context.

Although it is probable that the right of transferring employees to be collectively consulted on a proposed transfer of their employer’s business will be removed, as will the right not to have the terms of their contract varied, it is likely that other domestic legislation and the common law will adapt to confer some protection, albeit admittedly not entirely equivalent to that removed. For example, the domestic protections on dismissals and redundancies conferred under Parts X and XI of the ERA will continue to impose an obligation on the employer to consult with an employee pre-dismissal about any proposed dismissal or redundancy. Likewise, the common law of the contract of employment regulating the variation and implied terms of that contract will function to ensure that some measure of control over the behaviour of the employer is imposed if the latter attempts to foist contractual amendments on transferring employees without their consent.

The common law will also be relevant in the event that the EU-derived rights to annual leave/holiday pay and maximum weekly limits on working hours in the Working Time Regulations 1998 (SI 1998/1833) are removed. For example, the implied terms of the employment contract place limits on the power of employers to exercise contractual options to extend the working hours of employees (Johnstone v Bloombsury Health Authority 1991) and it is likely that similar common law protections would be adapted to afford employees a range of rights to annual leave as a means of ensuring that employers exercise reasonable care for the physical and psychiatric well-being of their employees.

Finally, Michael Ford QC also pinpoints the protections for agency workers, part-time workers and fixed-term workers as targets for future repeal, each of which are grounded in EU law. These measures ensure parity of treatment with permanent, full-time workers directly employed by the employer. Whilst any repeal would be a regressive development for workers’ rights, in light of the statistical evidence that the majority of such atypical workers are female, domestic anti-discrimination legislation arguably could fill the gap to offer them redress if they were treated less favourably than permanent, full-time workers colleagues who are directly employed by the employer. This would be based on the statutory tort of indirect sex discrimination, since such unequal treatment would be in contravention of section 19 of the Equality Act 2010.

Of course there are deficiencies in the domestic legislation and the common law that could or would operate to plug any spaces left by the repeal of UK legislation based on EU labour laws. For example, the common law underwrites the ability of employers to dictate contractual terms, imposes implied terms designed to ensure the subordination of the employee to the employer, and confers unrestricted powers in favour of employers to dismiss and re-engage employees with few legal sanctions. However, I would argue that once EU laws are removed, domestic statute and the common law could well reach out and expand to occupy the field. The regenerative capacity of the common law and its ability to reinvigorate workers’ rights ‘in the gaps’ created by repealed labour legislation should not be underestimated.

As explicitly recognised in recent judgments, the judiciary are fully aware of movements in underlying social and economic conditions that are prejudicial to the cause of workers’ rights, and are not afraid to use them as a justification for common law expansion. In this way, they have shown themselves to be just as prepared to apply the accelerator on progressive common law developments as they are to hit the brake. The end result is that any post-Brexit legislation that is passed to strip back labour laws may not necessarily have the effect that is intended.

Featured image credit: Interference and the void, by geralt. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Filling the void: the Brexit effect on employment law appeared first on OUPblog.

June 6, 2016

Why Congress should pass the Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness Act

On 17th May, a massive fire caused Metro-North Railroad to reduce its commuter train service to and from Grand Central terminal. In light of this service disruption, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which operates Metro-North, “encouraged” commuters “to consider working from home.”

An out-of-state commuter who followed this sensible advice will be doubled taxed by New York for working at her home. Under its so-called “convenience of the employer” doctrine, New York imposes income taxes on a day when a nonresident works at her out-of-state home for a New York employer. Since the state of residence can legitimately tax its resident’s income on this work-at-home day, the upshot is often double income taxation, as the Empire State inappropriately taxes income earned outside its borders.

Only weeks before this most recent train service disruption, members of the Connecticut congressional delegation reintroduced legislation to bar New York and other states from using the “convenience of the employer” rule to tax income earned outside New York’s borders. In the Senate, Senator Richard Blumenthal, supported by his Connecticut colleague Senator Christopher Murphy, introduced the Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness Act of 2016. In the House, Representative James Himes introduced the Act as well.

If enacted into law, the Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness Act would prevent any state, most prominently New York, from taxing employees’ incomes on days when they work at their out-of-state homes. On such work at home days, these nonresidents do not set foot in New York State and use no New York services. On these days, these employees are receiving all their public services from their home state and its localities. As a matter of tax policy and constitutional law, there is no persuasive justification for New York’s taxation of income earned outside New York’s borders.

In the House, Representative Himes was joined as co-sponsors, not only by his Connecticut colleagues Representative Elizabeth Esty and Representative Rosa DeLauro, but also by Representative Scott Garrett of New Jersey and Representative Chellie Pingree of Maine. Their co-sponsorship of the Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness Act reflects the important fact that New York increasingly taxes the incomes of telecommuters who work at their homes throughout the country.

Consider, for example, the case of Thomas Huckaby of Nashville, Tennessee. Mr. Huckaby is a computer programmer. In 1994 and 1995, Mr. Huckaby spent three-quarters of his work days at his home in the Volunteer State. He worked the other one-quarter of his time in New York.

No one doubts that New York can legitimately tax the one-quarter of Mr. Huckaby’s salary that he earned in New York. However, under its employer convenience rule, New York taxed Mr. Huckaby’s entire salary including the income Mr. Huckaby earned while working at home in Nashville.

When Mr. Huckaby’s case reached the Court of Appeals, New York’s highest court, three of the court’s judges agreed with Mr. Huckaby. New York’s taxation of the income Mr. Huckaby earned in Tennessee, these judges declared, “violates the Due Process Clause of the United States Constitution.”

Unfortunately, four judges concluded otherwise and thus condoned New York’s extraterritorial income taxation of the salary Mr. Huckaby earned working at his home in Tennessee.

The Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness Act would overturn this result, requiring New York (and other states) to only tax employees’ salaries earned within the taxing state. As the Huckaby dissenters noted, this is the correct result as a matter of constitutional principle. It is also the correct result as a matter of tax policy: as on a day when a state provides no benefits to a nonresident working at home, that state has no legitimate claim to tax the income earned outside its borders.

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo proclaims that he no longer wants New York to be “the tax capital of the nation.” The Governor can take an important step in that direction by renouncing New York’s extraterritorial and unconstitutional income taxation of nonresidents under the employer convenience rule.

To date, however, Governor Cuomo has shown no interest in rationalizing this unreasonable feature of New York law. Accordingly, Congress should pass the Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness Act to prevent the unconstitutional and unwise double state income taxation of nonresidents who telecommute from their homes.

Featured image credit: subway nyc Brooklyn by Foundry. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Why Congress should pass the Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness Act appeared first on OUPblog.

Islands: Are some of the most unique biological study systems about to disappear?

The islands of the world’s oceans represent the diversity of life on Earth in all of its forms: geological, biological and cultural. There are at least 20,000 islands of an area greater than 1 km2, and millions if all sizes are considered. These include oceanic islands in a strict sense (i.e., islands that emerged as volcanoes from the seabed), atolls (the last stage of a former tropical volcanic island now represented by only a coral reef), land-bridge islands (continental peninsulas that due to interglacial sea-level rise lost their connection to continents), other islands on a continental shelf, and continental fragments or micro-continents (originally continental areas but now isolated in the ocean through continental drift, e.g., Madagascar or Seychelles).

Further, below sea level, seamounts rise from the seabed but do not reach the ocean’s surface. They are important habitats for sea-life and some of them emerge above the ocean’s surface in times of lower sea levels (e.g. during glaciation periods) and are therefore important for understanding dispersal of species to isolated islands via stepping stones. Islands can be found in all oceans of the planet, at all latitudes, and consequently in all climate zones: from the Mediterranean Sea, via Macaronesia and across the Atlantic to the Caribbean Sea, across the vast Pacific from the East Pacific, to Polynesia, Melanesia, and Micronesia and further to South-East Asia, and back to Africa across the Indian Ocean. Not to forget the Arctic and Subantarctic islands at high latitudes.

Oceanic islands are renowned for the many and diverse scientific breakthroughs that their fascinating biotas have enabled during the past two centuries. They have served as model systems for research in biogeography, ecology, evolution and conservation. Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace independently discovered the principles of evolution after extended travels through the island archipelagos of the world. MacArthur and Wilson’s dynamic theory of island biogeography has become the most influential theory in biogeography, and has major relevance to other biological fields including conservation biology. Peter and Rosemary Grant’s work on the dynamic adaptation of beak size and form of Galápagos finches to variation in food sources has become a textbook example of rapid evolution that happens within years in nature.

In recent years island biology has gained new momentum as a major research avenue in ecology, evolutionary biology and biogeography as exemplified by a series of international island biology conferences (2014 in Hawaii, 2016 in the Azores). Such new dynamism in island biology is stimulated by the emergence of a truly global island research community that today works on most islands of the world (Kueffer et al. 2014). This enables big-data analyses of island biodiversity patterns and multi-island comparisons. In addition, modern research approaches such as genomics, phylogenetic and functional ecology, and palaeoecology, are also increasingly used on islands enabling interdisciplinary work across levels of biological organisation from genes to ecosystems and integrating ecological and evolutionary processes.

At the same time, islands urgently require major additional conservation efforts. Many species face extinction, natural areas are small and fragmented and alien species dominate most ecosystems. Although the world’s islands together make up only ca. 5% of the Earth’s land area, it has been estimated that up to one-quarter of global plant diversity is endemic to islands. A majority of these species might be threatened by extinction through habitat loss, invasive species, small population sizes, loss of their mutualists (e.g. seed dispersers or pollinators) and climate change. The situation is so severe that many conservationists believe that traditional conservation strategies, such as the establishment of protected areas, do not suffice to save island biodiversity. As a consequence, islands have become places where new conservation solutions for the twenty-first century are being tested (Kueffer and Kaiser-Bunbury 2014).

Novel ecosystems that are dominated by non-native species are increasingly accepted as a new and inevitable reality by many conservationists. Sometimes non-native species are even deliberately released into the wild in the hope that they will replace extinct species and take on their lost ecological functions; for instance giant tortoises on the islands of Mauritius and Rodrigues in the Western Indian Ocean. And rare species are moved from the wild to park-like protected areas, e.g. on small offshore islands, where they can be supported through intensive management. These biodiversity parks are a mix between nature reserves, botanic gardens and zoos. Whether or not such innovative new conservation solutions will suffice to save the many unique species that existed for thousands of years in isolation from any other biota on tiny land fragments in the oceans of the world, will be decided in the next few decades.

Islands are like thousands of unique pearls sprinkled across the globe. Their unique biological treasures will disappear first if we do not find solutions to growing environmental problems. Threatened from the surrounding oceans by sea level rise as a result of climate change, and threatened from within through unsustainable use of resources and land. Will they be remembered as the early warning systems that helped to trigger action just in time, or the beginning of the destruction of millions of years of evolution?

Featured image: From Tenerife with an endemic Echium in the foreground, by José María Fernández-Palacios

The post Islands: Are some of the most unique biological study systems about to disappear? appeared first on OUPblog.

Observing Ramadan at the Qatar National Library

Every year, we welcome June with dreams of beaches, warm sunshine and a well-deserved vacation. This year, for over 1 billion Muslims across the globe, June represents something more spiritual as it marks the holy month of Ramadan.

I think by now most people have heard of Ramadan and how those who observe it spend all day without any water or food. But what exactly is Ramadan and what does it represent?

Ramadan is the ninth month in the 12 month Islamic calendar. As this calendar is based on the lunar cycle, Ramadan occurs during different seasons every few years. For us Muslims, Ramadan is not simply a month where we fast from dawn to dusk; it holds a much deeper significance. This month represents an opportunity for Muslims to stop and connect with their inner souls, strengthen belief in Allah and fully live by the values of Islam.

Fasting during Ramadan is one of the five pillars of Islam and Ramadan is the month where this came to be. In this month the first verses of the Qur’an were recited to Prophet Mohammad (peace be upon him) by the angel Jibril and it was also when the Qur’an came to its completion.

Image used with permission.

Image used with permission.With the coming of Ramadan in Qatar, something changes in the air and you can feel the beginning of a wonderful and special month. The atmosphere becomes one where people put aside their differences, reach out to their families, join in charitable acts and try hard to be the best they can be. School and work hours are reduced and restaurants close during the day to open with Iftar (breaking the fast) and stay open to Suhoor (just before the dawn prayer). The whole community feels the spirit of Ramadan including non-Muslims who respect this holy ritual. Some even fast with their Muslim peers!

As a national and public institution, the Qatar National Library (QNL), a member of the Qatar Foundation for Education, Science and Community Development (QF), works year round, to preserve the history and heritage of the Arabic and Islamic world through many initiatives. This includes launching the Qatar Digital Library, a world-class online portal that provides users worldwide with free access to an extensive collection of historical archival items and manuscripts related to Qatar, the Gulf region and the wider Middle East. This online portal is the result of an ongoing partnership between QF, QNL and the British Library. Alongside QDL, Qatar National Library also contributes a collection of books and documents pertaining to Islamic and Arab history to the World Digital Library.

Image used with permission.

Image used with permission.QNL also holds and continuously develops a Heritage Collection that provides unparalleled contribution of historical sources about Qatar and the region and includes precious Arabic manuscripts illuminating centuries of Arab and Islamic influence on world civilisation. These efforts are driven by QNL’s vision of developing knowledge of Qatar’s and the Arab and Islamic world’s heritage and future.

During the month of Ramadan, QNL will join the Qatar Foundation in its celebration of Garangao, a GCC tradition that occurs every year on the eve of Ramadan, where children wear traditional outfits and go from door to door to collect treats. The library will also host a Suhoor event for its employees to share the joy of this month, and will also conduct a weekly competition for teens and children to submit themed photos such as performing good deeds, celebrating Garangao, eating traditional foods and celebrating the Eid festivities.

Through these activities and more, QNL is devoted to creating a versatile and dynamic public library that will serve as an educational and enjoyable community center for all members of the public.

Qatar National Library wishes everyone a very blessed month of Ramadan.

Featured image: “Prière de Tarawih dans la Grande Mosquée de Kairouan. Ramadan 2012” by Zied Nsir. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Observing Ramadan at the Qatar National Library appeared first on OUPblog.

Why Sykes-Picot is (still) important

The centenary of the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement has been marked by what can only be described as a deluge of writing. Opinions have been numerous, sometimes tiresomely so, and have ranged exceedingly widely. Some have presented the agreement as far and away the most significant point of reference for understanding the contemporary Middle East. Others have sought to revisit conventional interpretations of the agreement, typically by stressing that it was rapidly overtaken by other instruments and developments or by contending that corruption and authoritarianism, not European meddling, lie at the root of the region’s ongoing political and economic turmoil. These critical arguments are frequently advanced on the basis of a desire to “demythologize” the Sykes-Picot Agreement.

To be sure, there is something to be said for some of the arguments that have been levelled against the traditional understanding of the Sykes-Picot Agreement. However, they have sometimes been quite misleading, and they are nearly always in need of significant reframing and qualification.

To begin with, while it is true that the Sykes-Picot Agreement was not implemented directly or comprehensively, it is also true that it exemplified the logic of state-building through imperialist partition that would reconstitute the Middle East after the First World War. In late 1917, the Bolsheviks published the agreement’s text as part of a full-throated effort to mobilize the working classes of the world against the imperialist powers that had engendered the Great War. The Balfour Declaration, issued at nearly the same time, called for a “national home” for the Jewish people in Palestine – a territory for which Sykes and Picot had originally envisioned some type of “international administration”. All this did much to complicate and delegitimize the Sykes-Picot Agreement. Yet, the desire to restructure the region in line with European interests remained alive and well. Article 22 of the League of Nations Covenant stipulated that certain territories detached from the German and Ottoman empires were to be administered by foreign states. Such states were to exercise their powers under League supervision and with the aim of ensuring the “well-being” and “development” of the peoples concerned. The 1920 San Remo Conference determined the allocation of the Middle Eastern territories that would be integrated into the resulting regime of internationalized quasi-colonialism. And as specific instruments for each of the relevant territories were drafted and entered into force during the early 1920s, the institutional architecture of a full-fledged “Mandates System” took shape, inaugurating a process of state-building that would eventually result in the creation of a new, post-Ottoman Middle East. The final result did not correspond to the map upon which Sykes and Picot had scribbled their lines and letters, not least because the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne (which replaced the unratified 1920 Treaty of Sèvres) consolidated the Turkish nationalists’ control over Cilicia and northern Kurdistan. But it would never have materialized in the way that it did without the formative influence of the deal they struck in 1916.

Turn now to the claim that political instability and uneven economic development in the Middle East is attributable principally to decades of undemocratic government. Of course, neither the Sykes-Picot Agreement nor any of the other instruments with which it is directly or indirectly affiliated can be blamed for all of the region’s ills. To suggest otherwise would be to discount the agency of regional actors and to ignore the complexity of historical developments. After all, the degeneration of Arab nationalism from a secular and broadly socialist, if disturbingly chauvinistic, movement into the one-party rule of a Hafez al-Assad or Saddam Hussein was by no means an inevitable consequence of the work of Sykes, Picot, or the countless others who had a hand in the construction of the modern Middle East.

That said, it is simply not possible to discount the significance of the kind of imperial intervention and externally coordinated state-building that Sykes and Picot facilitated. At root, this does not mean that the fundamental problem with the Sykes-Picot Agreement stems from the “arbitrariness” of the borders it ultimately helped to establish – or even, as is sometimes suggested, with the very idea of firm international boundaries in the Arab world. (It bears noting that while many Middle Eastern borders were indeed drawn arbitrarily, others grew out of long-standing Ottoman administrative practices. Even more importantly, one should keep in mind that the tendency to characterize Iraq and other states as “artificial” has often functioned as an imperialist narrative used to justify continued Western control or “assistance”.) Instead, it means that the fundamental problem with the agreement is that it bequeathed to us a legacy of Western intervention throughout the Middle East. It is bad faith and bad history – not to mention exceedingly bad “policy” – to condemn authoritarianism in the Middle East without appreciating the fact that the processes of elite formation and state capitalism that made it possible were fed by state-building experiments organized to a large degree from London, Paris, Geneva, and other Western centres.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement is not everything it has been made out to be. Its significance has frequently been exaggerated, and its links with countless other promises and arrangements – some conflicting, others complementary – have sometimes been overlooked. Nevertheless, its symbolic importance can hardly be doubted. From advocates of pan-Arabism to supporters of Kurdish nationalism, from Islamists running roughshod over one border after another to Palestinians denouncing decades of occupation and displacement, “Sykes-Picot” remains a touchstone. If it is a “mythology”, it is one that has given rise to a tremendous amount of upheaval and that continues to exercise a considerable amount of influence.

Featured image credit: ‘Living on the verge of Al Habbala Valley’. Photo by Wajahat Mahmood. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Why Sykes-Picot is (still) important appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten under-appreciated ancient thinkers [timeline]

The influence and wisdom from ancient philosophers like Socrates, Aristotle, and Plato is undeniable. But how well do you know the life and works of Macrina, Philo of Alexandria, or Gorgias? Although known for his work in botany, did you know Theophrastus was a pupil of Plato as well? Peter Adamson, author of the History of Philosophy series, highlights ten under-appreciated ancient thinkers for their important, yet often overlooked, contributions to Western philosophy. Discover more about them in the timeline below.

Featured image credit: The Parthenon (1871) by Frederic Edwin Church. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Ten under-appreciated ancient thinkers [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers