Oxford University Press's Blog, page 497

June 21, 2016

“Soft” affirmative action in the National Football League

Current statistics show a startling lack of diversity in corporate boardrooms. In February 2014, Fortune reported that just over 4% of Fortune 500 CEOs were minorities, a classification including African Americans, Asians, and Latin Americans. This is particularly disturbing given that these classifications of minorities comprised 36% of the United States population, and that, according to The Wall Street Journal, many top business schools boast that ethnic or racial minorities comprise 25% or more of their student bodies. Affirmative action is a potential policy response to this lack of diversity. However, academic research has provided little evidence as to the efficacy of affirmative action policies aimed to increase diversity in executive hiring, perhaps due to a lack of affirmative action policies that pertain to executive hiring. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits firms from establishing “hard” affirmative action policies that would require the direct consideration of minority status during the hiring process (e.g., quotas or inflexible goals). However, “soft” affirmative action policies that are designed to change the composition of the candidate pool, rather than criteria used during the hiring process, could be a viable option for firms seeking to increase diversity at the executive level.

Even as the news media have continually highlighted the lack of diversity, and particularly racial diversity, in the corporate suite, firms have been loath to implement affirmative action policies. That said, with the introduction of the “Rooney Rule,” the National Football League (NFL) has emerged as an unlikely candidate to provide a case study on the impact of a “soft” affirmative action policy on minority hiring in executive leadership. Established in 2003, the Rooney Rule requires NFL teams to interview at least one minority candidate for any head coaching vacancy. No quota or preference is given to minorities during the hiring decision; teams are simply required to interview at least one minority candidate.

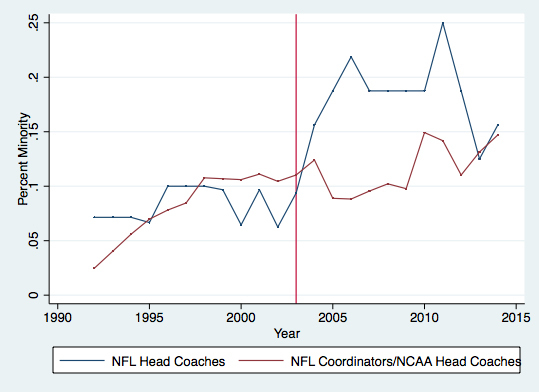

A recent study uses econometric techniques to identify the causal impact of the Rooney Rule. More specifically, it uses a difference-in-differences approach, where NFL offensive and defensive coordinators as well as NCAA head coaches serve as comparison groups, to estimate the impact of the Rooney Rule on the probability that a minority candidate fills an NFL head coaching vacancy.

The picture below compares the percentage of minority offensive and defensive coordinators as well as NCAA head coaches to head coaches in the NFL. The blue line presents the percent of minority NFL head coaches from 1992 to 2014. The solid horizontal line in 2003 visually identifies the year the Rooney Rule was implemented. There is a notable increase in minority hires around the time of the Rooney Rule’s implementation; however, societal changes (e.g., changes in national and regional racial sentiment) over this period make it difficult to credibly identify causal inferences from this trend. If the Rooney Rule was simply implemented at a time coincident with changing social factors that would have increased the probability that a minority fills an NFL head coaching position regardless of any policy intervention, we would incorrectly attribute outcomes to the implementation of the Rooney Rule.

The Impact of “Soft” Affirmative Action Policies on Minority Hiring in Executive Leadership, graph by Cynthia DuBois. Used with permission.

The Impact of “Soft” Affirmative Action Policies on Minority Hiring in Executive Leadership, graph by Cynthia DuBois. Used with permission.To circumvent these concerns, the difference-in-differences strategy compares the deviation from prior hiring trends among a “treatment group” that was subject to the Rooney Rule (i.e., NFL head coaches) with the analogous deviation for a “comparison group” (i.e., NFL coordinators and/or NCAA head coaches) that was arguably less affected by implementation of the Rooney Rule, if at all. The intuition is that the deviation from trend in the comparison group will reflect those hard-to-observe factors (e.g., changes in racial sentiment) that may have influenced the hiring decision in the absence of the Rooney Rule. The most obvious comparison group candidate is NFL coordinators. The Rooney Rule only applies to the hiring of NFL head coaches, not to the hiring of NFL coordinators. Offensive and defensive coordinators represent the second level of the football command structure after the head coach. If the head coach is the CEO of the firm, then the offensive and defensive coordinators are the top-ranking vice-presidents. To test the robustness of results, it is important to identify a second comparison group, NCAA head coaches. NCAA head coaches are also not subject to the Rooney Rule.

Although the comparison group exhibits a positive trend over time, there is no notable increase in minority hires that is analogous with the implementation of the Rooney Rule. The intuition of the difference-in-differences study design is operationalized through regression modeling. Regression analysis is a statistical process that quantifies the relationship between variables (in this case, the implementation of the Rooney Rule and the probability that a minority fills an NFL head coaching vacancy). The regression models estimate that a minority candidate is a statistically significant 19 – 21% more likely, depending on the comparison group (i.e., NFL coordinators or NCAA head coaches), to fill an NFL head coaching vacancy in the post-Rooney era than the pre-Rooney era. Estimates show surprising consistency across comparison groups as well as model specifications and tend to be statistically significant at traditional levels of confidence.

The NFL case study provides evidence that “soft” affirmative action policies may be able to influence executive hiring decisions. However, examples of firms willing to execute such policies are scarce. That said, the tide is showing signs of turning. For example, Facebook introduced their version of the Rooney Rule that will be implemented at the social network widely. The NFL also announced that they would be expanding the Rooney Rule to require the NFL league office to interview female candidates for vacant executive positions. Senate Resolution 511 encourages companies to voluntarily establish a version of the Rooney Rule. As many European countries have taken legislative action to increase diversity in corporate leadership, “soft” affirmative action policies such as the Rooney Rule offer firms a low cost policy option to address a lack of diversity at the executive level.

Featured image credit: ‘Gillette Stadium 2’ by Bernard Gagnon. CC-BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post “Soft” affirmative action in the National Football League appeared first on OUPblog.

June 20, 2016

The value of humanism

World Humanist Day is celebrated on 20 June, providing an opportunity for humanists and humanist organizations to promote the positive principles of Humanism. Celebration of the day began in the 1980s and support for it has grown ever since. This post explores some of the values of Humanism, specifically truth and realism.

Humanism, as I see it, is a view that believes in secular enlightenment, in the importance of truth, rationality, and objectivity, and in the value and progress of our species. It rejects religion, and affirms, if not the perfectibility of human kind, at least our ability and resourcefulness in finding solutions to the problems that beset us. Some of these problems are old ones; others are new. Some are of our own making; others are not. But, whatever the difficulties, the humanist has faith in our capacity to confront and overcome them by the application of intelligence and hard work.

A central humanist concern is the value of truth, of seeing things as they are. Defending this value has often in the past meant confronting the claims of the church and other religious organizations, but in recent years it has increasingly also meant rebutting postmodernist and deconstructionist attacks on the very idea of truth and on its concomitant values of rationality, objectivity, and impartiality. These values, we are told, are not neutral, but ideologically charged; there is no such thing as objective truth, only greater or lesser degrees of consensus among members of the community.

The slogan “everything is ideological” is less interesting than might appear. It should simply be accepted, but the problem with it is that it gets us nowhere. Once it has been agreed on all sides that to pursue the goals of rationality and objectivity is to promote an ideology, we are left exactly where we were. The slogan gives us no guidance on the question which ideologies we should embrace. The humanist’s claim is not that rationality and objectivity are not ideological, but, agreeing that they are, that they are better ideologies than the alternatives. The justification for that claim can only proceed circularly, in terms of the very values for which we are arguing. But that will be true of any fundamental defense of value. The key argumentative point, for humanists, will be that their opponents can be shown already to adhere to these values, only not consistently.

Yes/No by geralt. Public domain via Pixabay.

Yes/No by geralt. Public domain via Pixabay.Similarly, the assertions of postmodernists that there is no such thing as objective truth, either in some particular domain (such as the past), or generally, stand in conflict with their own practice, for they regularly make claims to truth themselves. One of the reasons, I believe, why there been such a loss of faith in the idea of objective truth in recent decades is that people have fallen into an old philosophical confusion, that of drawing metaphysical conclusions from epistemological premises. Our knowledge-gathering processes are fallible; we are liable to make mistakes; people disagree, sometimes violently, over many descriptive and normative issues. But it does not follow that there is no fact of the matter about the disputed territory. If I’d earned a pound every time I had read a literary critic or theorist say words to the effect of “The interpretation of this text is disputed, so it can’t have an objective meaning,” I would be rich man by now.

The phenomenon of dispute and disagreement, the making of mistakes, the fallibility of our perceptions and judgments and so on—these things do not import the absence of objectivity in the subject matter in question. In fact, they imply the exact opposite. People don’t argue about anything unless they think there is a fact of the matter. Take economics, for example. Many economic questions are highly contested, but it would be absurd to conclude from this that there are no economic facts, or no facts in the areas of dispute. The reason why there is disagreement in economics is not that there are no relevant facts, but rather that the facts are extremely complicated, so that it’s hard to achieve a perspicuous view of them. The same is true of literary interpretation. Literary works belong to a tradition, and that is essential to their aesthetic status, so that understanding them requires the critic to acquire deep knowledge of the works’ literary and cultural context and background. That is an extremely hard thing to do, partly because our evidence is often very patchy, but also partly, and oppositely, because for many literary works enough evidence of various sorts has survived to make the task of surveying it an enormous one.

Evidence has to be sifted, evaluated. At this point postmodernists wheel out what is often presented as a decisive argument against objectivity: “there is no innocent eye.” We, the interpreters, are thoroughly embedded in our own cultures; we have the interests and prejudices of our age. So how can we view either the present or (in particular) the past objectively? But this argument, if it worked, would also work against scientific—indeed all—knowledge: physicists are physically and culturally embedded in their environment, so how can they acquire objective knowledge of it? I will not try to answer that question in detail now; but there is at any rate a short way with the postmodernist worry, and that is to say that, however they do it, physicists do acquire objective knowledge of the world, notwithstanding the fact that they are embedded in it (and in their own age and culture). We know that, so we also know that the postmodernist argument goes wrong. It is an old (and Nietzschean) mistake to think that perspectivalism implies irrealism; in fact, like the phenomenon of error, it implies realism.

Featured image: Stones by Unsplash. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The value of humanism appeared first on OUPblog.

7 things you may not know about conservative Christian businesses

Corporations have become places for evangelical activity and expression, and businessmen—sometimes working individually, sometimes collaboratively—have shaped what we think of today as conservative “Christian” culture and politics. Here are 7 facts you may not know about the culture and history of Christian business.

Camaraderie between corporate executives and conservative evangelicals is not a new thing but stretches back to the first days of the fundamentalist movement in the early twentieth century. For instance, one of the foundational publications of the movement – The Fundamentals of the Faith, published from 1910 to 1915 – depended on the financial and administrative help of Lyman Stewart, a wealthy oil tycoon. Fundamentalist businessmen organized in greater numbers in the 1930s and 1940s via the Christian Business Men’s Committee, International (CBMCI), which at times provided organizational and financial support for upstart conservative evangelical efforts, such as Young for Christ, The Navigators, and evangelist Billy Graham’s crusades.

Evangelical businessmen were not relegated to an evangelical “subculture” or off-the-beaten path niche of businesses in corporate America. They have founded or at one time headed well-known, large-scale companies like ServiceMaster, H.E.B., Pilgrim’s Pride, Eckerd’s, Walmart, Tyson Foods, and Genesco, among many others. Thousands of small businesses continue to operate in accordance with evangelical-inflected “Christian” business practices and cater to customers who may or may not be aware of their evangelical business identity or histories.

One of the most popular versions of the Bible, the New International Version or NIV, is published by Zondervan, which is owned by HarperCollins and a subsidiary of NewsCorp, owned by media mogul Rupert Murdoch. But Murdoch was hardly the first non-evangelical big businessman to take an interest in evangelical assets and aspirations. In the mid-1950s, J. Howard Pew, an oilman from Pennsylvania, joined with Billy Graham’s father-in-law, L. Nelson Bell, to underwrite Christianity Today, an upstart evangelical magazine. By the mid-1960s, it was the most-read evangelical publication in the country, surpassing in circulation other conservative periodicals like National Review and its main liberal competitor, The Christian Century. Though more of a public forum for debating the place of evangelicalism in modern life than a political outlet (much to Pew’s chagrin), Christianity Today nevertheless embodied the corporate-evangelical nexus at mid-century and promoted new “norms” regarding what it meant to think and act as a “conservative” evangelical in modern America.

At times, evangelical activists can actually see losing business as the mark of doing “Christian” business. Though certainly not as common as the pursuit of profit, the sacrificial thread in evangelical thought – of sacrificing one’s wealth, time, or well-being, inspired by the sacrificial example of Jesus Christ – has led certain businessmen to equate not selling certain services or goods with a sense of Christian mission. This is contingent on a business’s particular market. Restauranteurs like Chick-fil-A’s S. Truett Cathy (whose restaurants close on Sundays) have often taken such Christian considerations of sacrifice to heart more often than, say, hoteliers like Cecil B. Day, who could not kick out patrons to Days Inn on a Saturday night and, instead, chose to eschew profits derived from in-room alcohol sales or in-lobby bars.

There is a business directory of Christian businesses called The Christian Yellow Pages. It started in 1972 as an effort to establish a parallel consumer market for conservative evangelicals who wanted to buy goods and services from like-minded small business owners. The Anti-Defamation League sued it in the early 1980s for not advertising Jewish sellers, which it did in future issues (although it remained primarily a venue for advertising to “Christian” – largely meaning “evangelical” – customers).

Legal changes played a notable role in shaping the contours of the Christian business landscape. Though fair employment laws and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 focused primarily on racial discrimination, such laws also shaped Christian businesses and their approach to employee relations. With less legal room to shape their corporate cultures in favor of a specific religion, many evangelical businesses lauded other “religious” principles and practices, from voluntary in-office prayer services to an emphasis on seemingly broad “biblical values” or “Judeo-Christian values” in administrative decision-making. Such linguistic, rhetorical, legal, and cultural negotiations nevertheless cornered the market on the meaning of the word “Christian” in business, with conservative evangelicals largely in charge of what it meant to do “Christian” business in an increasingly pluralistic

The office cubicle was invented by a Christian company. The De Pree family, which headed the furniture company Herman Miller, interpreted their Dutch Reformed evangelicalism to mean the valuing of “high design” and better employer-employee relations through modular office furniture. Hence, they developed the “Action Office II,” a predecessor to the contemporary office cubicle, in the mid-1960s as a means to free employees from fixed-in-place desks. (At the time, the Office Space-like, “cubicle drone” hellscape of the future was not their intent.)

Featured image credit: CC0 via Pexels.

The post 7 things you may not know about conservative Christian businesses appeared first on OUPblog.

Salafis, face veils, and ‘Ramadan resolutions’

I’ve often heard Muslims describe the holy month of Ramadan as an ‘iman [i.e. faith] boost’ – as though it were some kind of spiritual energy drink. A whole month, in other words, to recharge one’s spiritual batteries. In busy modern lives, Ramadan is an opportunity to focus on getting closer to God through religious practices – like praying, charitable giving, and avoiding alcohol – that may have been sidelined during the rest of the year.

Just like New Year’s resolutions, these determined efforts to ingrain virtuous habits and abandon objectionable ones often lose steam by the following month. Indeed, sometimes (as with the secular custom of ‘Dry [i.e. alcohol-free] January’) this is quite deliberate.

In other cases, however, Ramadan resolutions can usher in a rigorous programme of self-improvement that continues long after the month has passed. In fact, for some of the young Salafi Muslims I interviewed in London, it actually triggered a series of behavioural changes that led to fundamental shifts in identity and the acceptance of a highly conservative version of Islam.

Since the 1980s, Britain has been host to small but rapidly growing communities that follow Salafism (often called ‘Wahhabism’). These communities are disproportionately young and first-generation in membership, meaning that most adherents grew up in non-Salafi families, and became Salafi during their teens or twenties. For women, adopting a strict (or stricter) Islamic dress code is a demanding but a necessary ingredient of this transformation. Salafi teachings require women to wear long, loose-fitting gowns, and recommend face veils, too. This makes Salafi women particularly vulnerable to stereotyping and Islamophobic attacks in contemporary Western societies – as well as to criticism from their generally less conservative families.

Interviewing young Salafi women from various backgrounds, I learned that for several, it was Ramadan that triggered (or hastened) a dramatic and lasting identity transformation from non-observant Muslim to fully-covered Salafi. Every story was unique, but some patterns emerged. Whereas pre-Ramadan, a woman might feel embarrassed or fearful to go out in anything more than a simple headscarf, she would emerge from the holy month draped from head to toe in black, possibly covering even her face.

Of course, such strict dress codes are widely regarded by Muslims, as well as non-Muslims, to be excessive. Indeed, the perception of Salafis as ‘extremists’ is commonplace, and even some of my interviewees admitted that they’d initially seen Salafism as a ‘cult’ that imposed draconian restrictions on its followers. Salafis say that these sartorial rules are justified because they mirror those followed by the salaf, or first three generations of Muslims, which includes the Prophet Muhammad and his wives.

Salafis want to restore Islam to the ‘pure’ form of this early period by drawing on the holy texts – the Qur’an and ‘authentic’ hadith, or traditions of the Prophet – as literally and exclusively as possible. This leads to controversial and conservative teachings, such as separation from non-believers, wifely obedience, and strict gender segregation. Salafism is a global trend with significant diversity, especially in terms of attitudes towards political engagement, but my research focused on key UK Salafi groups that oppose Jihadism and all organised forms of political participation.

Saidah’s story is particularly striking. Growing up in a largely non-Muslim neighbourhood of south London, she often felt too self-conscious to wear any clothes that identified her as a Muslim. She covered her head only for occasional trips to the local Nigerian mosque with her parents.

Salafi women, Brixton, south London, UK. May 2015. Photo Copyright: Eleanor Bentall. Used with permission.

Salafi women, Brixton, south London, UK. May 2015. Photo Copyright: Eleanor Bentall. Used with permission.As a teenager, she had started wearing a fashionable head wrap, but this decision had little to do with religion, and it did not stop her from going clubbing, dating, and even selling class A drugs. “I used to go and meet people to sell drugs to them,” she said, “and I used to wear a fashionable-looking headscarf just so I didn’t look like a suspect!”

When Ramadan came, she would make a special effort to wear Islamic dress, but it didn’t last. “Every Ramadan, you’d see me with a hijab [head covering] and abaya [loose-fitting robe]. Then, after Ramadan, it came off,” she said.

She repeated this on-off cycle for several years until Ramadan in 2010, when she was 21. That year, she decided to attend night prayers (tarawih) at the Salafi mosque in Brixton, south London. There, she bumped into some old school friends, many of whom were from non-Muslim families, and was astonished to find that they were now all observant Muslims.

“They inspired me to start practising,” she explained. “They said: ‘Why don’t you come to iftar [the breaking of the fast] at the mosque?’ I realised I didn’t have much excuse.”

The young women would go from mosque to mosque, attending Islamic study circles and praying together. Everyone except Saidah would be covered from head to toe in black, so her thoughts naturally turned to her own dress. “I used to wear all sorts of colours, with gems down my abayas, and I used to stick out like a sore thumb. I felt really uncomfortable.”

She asked her friends to take her to a shop to buy her first plain black abaya. Not long afterwards, she bought a niqab, too, and relished the anonymity it gave her when she realised that old acquaintances from her drug-dealing days did not recognise her in the street. “I fell in love with this piece of cloth that protected me from my past,” she said.

By the time Ramadan had ended, she had decided that “there was no way I could have gone back.” She said: “I was happy: I was around a group of people that was doing the same thing as me, and I was proud to say: ‘Yeah! I’m a Muslim!'” She continued to research Salafism and to wear her abaya and niqab, despite daily Islamophobic abuse in public places and her parents’ protests that “this is not Islam!”.

Saidah’s story, and many others I heard, highlights the intense social interaction that often occurs during Ramadan. In certain cases, this interaction could prompt or ease a young woman’s conversion to an austere brand of Islam that she might otherwise have avoided.

Of course, this pull factor is neither necessary nor sufficient for conversion to Salafism to occur. Many Muslims share similar intense social experiences during Ramadan, yet only a very small number find anything appealing in Salafism. For the women I interviewed, becoming Salafi was a gradual process related to a complex combination of pushes and pulls that was unique to each individual.

But it is clear that the holy month and the social activities it fosters – such as tarawih and iftar – had helped to create an environment in which conservative practices, such as the niqab, were judged by the women to be right and praiseworthy, rather than extreme and embarrassing. Ramadan gives them the social and spiritual ‘boost’ necessary to be more daring and consistent in their religious practices, despite the negative reactions these often provoke beyond Salafi spaces.

Featured Image Credit: Public domain via Pexels.

The post Salafis, face veils, and ‘Ramadan resolutions’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Salafis, the face veil, and ‘Ramadan resolutions’

I’ve often heard Muslims describe the holy month of Ramadan as an ‘iman [i.e. faith] boost’ – as though it were some kind of spiritual energy drink. A whole month, in other words, to recharge one’s spiritual batteries. In busy modern lives, Ramadan is an opportunity to focus on getting closer to God through religious practices – like praying, charitable giving, and avoiding alcohol – that may have been sidelined during the rest of the year.

Just like New Year’s resolutions, these determined efforts to ingrain virtuous habits and abandon objectionable ones often lose steam by the following month. Indeed, sometimes (as with the secular custom of ‘Dry [i.e. alcohol-free] January’) this is quite deliberate.

In other cases, however, Ramadan resolutions can usher in a rigorous programme of self-improvement that continues long after the month has passed. In fact, for some of the young Salafi Muslims I interviewed in London, it actually triggered a series of behavioural changes that led to fundamental shifts in identity and the acceptance of a highly conservative version of Islam.

Since the 1980s, Britain has been host to small but rapidly growing communities that follow Salafism (often called ‘Wahhabism’). These communities are disproportionately young and first-generation in membership, meaning that most adherents grew up in non-Salafi families, and became Salafi during their teens or twenties. For women, adopting a strict (or stricter) Islamic dress code is a demanding but a necessary ingredient of this transformation. Salafi teachings require women to wear long, loose-fitting gowns, and recommend face veils, too. This makes Salafi women particularly vulnerable to stereotyping and Islamophobic attacks in contemporary Western societies – as well as to criticism from their generally less conservative families.

Interviewing young Salafi women from various backgrounds, I learned that for several, it was Ramadan that triggered (or hastened) a dramatic and lasting identity transformation from non-observant Muslim to fully-covered Salafi. Every story was unique, but some patterns emerged. Whereas pre-Ramadan, a woman might feel embarrassed or fearful to go out in anything more than a simple headscarf, she would emerge from the holy month draped from head to toe in black, possibly covering even her face.

Of course, such strict dress codes are widely regarded by Muslims, as well as non-Muslims, to be excessive. Indeed, the perception of Salafis as ‘extremists’ is commonplace, and even some of my interviewees admitted that they’d initially seen Salafism as a ‘cult’ that imposed draconian restrictions on its followers. Salafis say that these sartorial rules are justified because they mirror those followed by the salaf, or first three generations of Muslims, which includes the Prophet Muhammad and his wives.

Salafis want to restore Islam to the ‘pure’ form of this early period by drawing on the holy texts – the Qur’an and ‘authentic’ hadith, or traditions of the Prophet – as literally and exclusively as possible. This leads to controversial and conservative teachings, such as separation from non-believers, wifely obedience, and strict gender segregation. Salafism is a global trend with significant diversity, especially in terms of attitudes towards political engagement, but my research focused on key UK Salafi groups that oppose Jihadism and all organised forms of political participation.

Saidah’s story is particularly striking. Growing up in a largely non-Muslim neighbourhood of south London, she often felt too self-conscious to wear any clothes that identified her as a Muslim. She covered her head only for occasional trips to the local Nigerian mosque with her parents.

Salafi women, Brixton, south London, UK. May 2015. Photo Copyright: Eleanor Bentall. Used with permission.

Salafi women, Brixton, south London, UK. May 2015. Photo Copyright: Eleanor Bentall. Used with permission.As a teenager, she had started wearing a fashionable head wrap, but this decision had little to do with religion, and it did not stop her from going clubbing, dating, and even selling class A drugs. “I used to go and meet people to sell drugs to them,” she said, “and I used to wear a fashionable-looking headscarf just so I didn’t look like a suspect!”

When Ramadan came, she would make a special effort to wear Islamic dress, but it didn’t last. “Every Ramadan, you’d see me with a hijab [head covering] and abaya [loose-fitting robe]. Then, after Ramadan, it came off,” she said.

She repeated this on-off cycle for several years until Ramadan in 2010, when she was 21. That year, she decided to attend night prayers (tarawih) at the Salafi mosque in Brixton, south London. There, she bumped into some old school friends, many of whom were from non-Muslim families, and was astonished to find that they were now all observant Muslims.

“They inspired me to start practising,” she explained. “They said: ‘Why don’t you come to iftar [the breaking of the fast] at the mosque?’ I realised I didn’t have much excuse.”

The young women would go from mosque to mosque, attending Islamic study circles and praying together. Everyone except Saidah would be covered from head to toe in black, so her thoughts naturally turned to her own dress. “I used to wear all sorts of colours, with gems down my abayas, and I used to stick out like a sore thumb. I felt really uncomfortable.”

She asked her friends to take her to a shop to buy her first plain black abaya. Not long afterwards, she bought a niqab, too, and relished the anonymity it gave her when she realised that old acquaintances from her drug-dealing days did not recognise her in the street. “I fell in love with this piece of cloth that protected me from my past,” she said.

By the time Ramadan had ended, she had decided that “there was no way I could have gone back.” She said: “I was happy: I was around a group of people that was doing the same thing as me, and I was proud to say: ‘Yeah! I’m a Muslim!'” She continued to research Salafism and to wear her abaya and niqab, despite daily Islamophobic abuse in public places and her parents’ protests that “this is not Islam!”.

Saidah’s story, and many others I heard, highlights the intense social interaction that often occurs during Ramadan. In certain cases, this interaction could prompt or ease a young woman’s conversion to an austere brand of Islam that she might otherwise have avoided.

Of course, this pull factor is neither necessary nor sufficient for conversion to Salafism to occur. Many Muslims share similar intense social experiences during Ramadan, yet only a very small number find anything appealing in Salafism. For the women I interviewed, becoming Salafi was a gradual process related to a complex combination of pushes and pulls that was unique to each individual.

But it is clear that the holy month and the social activities it fosters – such as tarawih and iftar – had helped to create an environment in which conservative practices, such as the niqab, were judged by the women to be right and praiseworthy, rather than extreme and embarrassing. Ramadan gives them the social and spiritual ‘boost’ necessary to be more daring and consistent in their religious practices, despite the negative reactions these often provoke beyond Salafi spaces.

Featured Image Credit: Quran holy Islam by abd ulmeilk majed. Public domain via Pexels.

The post Salafis, the face veil, and ‘Ramadan resolutions’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Why we need the European Union

The slogan ‘Take back control’ has played a vivid part in the debate about the UK’s future: it suggests an enfeebled Britain that should break free of ‘Brussels.’ It is a pernicious misrepresentation of the role of the EU. ‘Control’ is an illusion in a world of economic interdependence: unilateral State action lacks the necessary vigour to tackle the major problems that citizens expect to be addressed – climate change, economic reform, security, migration, and so on. States need to co-operate. That is what the EU is for.

The EU is founded on an institutional architecture that is not based on the model of a State, but which rather seeks to reflect the interests of States and of their peoples in an environment of deepening transnational activity, that tends to push the effective site for problem-solving in some areas (such as climate change, economic reform, security, migration) beyond the State. In such circumstances the legitimacy of the process must be somehow secured, albeit unavoidably not by the orthodox patterns of democracy and accountability that are familiar within a State.

The abiding thematic tension lies between designing institutions with sufficient autonomy to pursue effective problem-solving while also ensuring that those institutions are subject to adequate levels of accountability. Moreover, the EU is built on a constitutionalised legal order, which aims to sustain effective policing of agreed rules, not only at supra-State but also at national level, while also protecting individual rights. This is international treaty law, but it is more than international treaty law. Most of all the EU is a site to manage the interdependence of States. The EU could be abolished tomorrow but the problems to which it is an intended solution would not vanish, and would generate an urgent construction of bilateral and multilateral arrangements to address them (which would quite likely be a lot less effective and more intransparent than those found right now in the EU itself).

So States exercise their sovereignty through membership of the EU. States give up a degree of power to act unilaterally so that they may participate in the deployment of a collective problem-solving capacity that is a great deal more effective. Resources of power are not finite: acting through the EU expands the sum of State powers so it becomes greater than its parts. The EU ‘adds value’ to its Member States. Moreover, the EU also serves as a means to impose constraints on States, to ‘tame’ their historically toxic capacity to cause harm to each other. The EU’s rules and institutions do not replace, still less suppress, the several different locations of political authority to be found across Europe, but instead lock those locations into a credible set of reciprocally undertaken commitments designed to make real promises to solve problems their citizens expect to see solved, and by preventing them inflicting external harm.

The EU aims to supplement the claims of its Member States to be effective democratic and legitimate actors in an interdependent world. At the same time it does not and should not pretend to suppress the diversity that is Europe’s most cherished richness. The EU aims to accommodate that diversity within a managed framework. It seeks not to replace States, but rather to achieve a better management of their interdependence.

Featured image credit: Control Panel by Les Chatfield. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Why we need the European Union appeared first on OUPblog.

June 19, 2016

US government’s premiere test program finds cancer risk from cell phone radiation: a game-changing global wake-up call

Have you heard that cell phones cause cancer, then they don’t, then they do? Confused enough yet? Let me break it down for you. Contrary to some claims, the new US government study by the National Toxicology Program (NTP) is hardly a shot in the dark or a one-off event. With this largest best-conducted animal study, we now have three different studies within the past six years where animals develop some of the same cancers from cell phone radiation as people. In the NTP study, male rats exposed to wireless radiation develop more unusual highly malignant brain tumors—gliomas—as well as very rare tumors of the nerves around and within the heart—schwannomas.

Rodent studies are the gold standard for testing chemicals. In fact, as the American Cancer Society notes, the NTP study comes from a world-renowned test program that involved twice the usual number of animals and triple the typical number of independent reviews of the pathology data. The NTP review process included blinded evaluations by statisticians and pathologists who did not even know the name of the ‘test agent’ they were examining.

An op-ed from the New York Times by pediatrician Aaron Carroll questions the relevance of these animal studies for humans. Chairman of Pediatrics at Hadassah Hospital Jerusalem, Dr. Eitan Kerem, does not agree, stating that “Such findings [of cancers in a test drug] in the pharma industry may prevent further developing of a drug until safety is proven, and until the findings of this study are confirmed parents should be aware of the potential hazards of carcinogenic potential of radiofrequency radiation.”

Prof. Eitan appreciates that every agent known to cause cancer in people, also produces it in animals when well studied. More recently, studies have found significant brain changes in cell-phone exposed Zebra fish which also share important properties with humans. If we fail to heed these studies and insist on more human data, we become the bodies of evidence.

Not a single one of the NTP rat controls developed these rare brain cancers or schwannomas of the heart. Yes it is true that historical controls used in other studies have had a few brain cancers, so why should we not compare these results with that? In scientific research, we take great care to subject controls and exposed animals to the same housing, light, food, water supply, cage rotation, etc. This NTP study placed all animals in a complex reverberation chamber that existed within a metal barrier that blocked all forms of electromagnetic radiation from entering—a Farraday cage. Thus it is entirely plausible that electromagnetic exposures from wiring, ceiling fans, HVAC, or even technicians with phones in their pockets, could have affected control animals in those older studies causing this rare brain tumor and the handful of schwannomas of the heart found in the past in other controls. The fact that not a single one of the controls in this study developed these rare tumors tells us a great deal.

Why then, did brain tumors occur only in male rats? The sexes differ not only in hormones but in the ways that their DNA deals with poisons. In fact, rare precancerous abnormalities in the brain and heart were also reported in both sexes in the NTP study. For many cancer-causing agents, tumors are more common in males than in females—although in this instance, both males and females had significantly more cardiac abnormalities, pre-cancerous lesions, and malignant nerve tumors within and around their hearts.

Wait a minute. Some have claimed that these results are not a true positive, but a false one, that is to say—a false finding that wireless radiation increases cancer. By design, this study had a 97% chance of finding a true positive. Using a relatively small number of animals to study a very rare outcome, this study in fact, had a far greater chance of a falsely negative finding than of a falsely positive result.

Why then does the public know so little about the how cell phones and wireless technology impact our health? In 1994, findings that such radiation could prove a risk spawned an unusual and little-known sport—that of “war-games”—outlined in a memo from Motorola to their PR firm. That year when University of Washington scientists, Henry Lai and V.J. Singh, first showed that radiofrequency radiation (RFR) damaged brain cells in rats, they were subject to well-funded coordinated efforts to discredit their findings, their livelihood, and their integrity. Their university was asked to fire them and the journal editor where their work had been accepted was pressured to un-accept it. Similar disinformation efforts confronted the REFLEX project in 2004—a $15 million European Union multi-lab effort—after it also determined that cellphone radiation caused biological impacts on the brain.

Another paper from the NTP finding genotoxic impacts of wireless radiation is under peer-review at this time. The capacity of this radiation to open membranes is so well established that a number of technologies have been FDA approved to treat cancer relying on electroceuticals that use electromagnetic radiation at various powers, waveforms, and frequencies.

If ever there was a time to re-think our growing dependence on wireless in schools, cars, homes, and energy production, this is it. There is no other suspected cancer-causing agent to which we subject our elementary school students or place directly in front of the brain and eyes with virtual reality. It makes no sense to continue building out huge wireless systems until we have done a better job of putting the pieces of this puzzle together. This latest report from the NTP should give us all pause.

Belgium has banned cell phones for children. Over a dozen countries are curtailing wireless radiation especially for children. Reducing exposures will increase battery life, decrease demand for energy, and lower health risks. Concerted steps to reduce wireless radiation such as those recommended by the Israeli National Center for Non-Ionizing Radiation, France, the Indian Ministry of Health, and the Belgian government are in order now.

Governments have a moral obligation to protect citizens against risks that cannot otherwise be controlled. The epidemics of lung cancer today are evidence we waited far too long to control tobacco. To insist on proof of human harm now before taking steps to prevent future damage places all of us into an experiment without our consent, violating the Nuremberg Code.

Featured image credit: Cell phone in hands by Karolina Grabowska.STAFFAGE. CC0 public domain via Pexels.

The post US government’s premiere test program finds cancer risk from cell phone radiation: a game-changing global wake-up call appeared first on OUPblog.

Portraying Krishna in X-Men: Apocalypse

Another summer, another season of superhero movies. Big budgets, big muscles, big explosions: Each release only strengthens the genre’s domination of Hollywood—and the sense that comic-book franchises make up a contemporary mythology, and superheroes are its gods.

Among this year’s offerings is X-Men: Apocalypse, which opened the last week of May. Apocalypse is the name of the villain, who makes his own claim to divinity in no uncertain terms. One of the film’s trailers features this grandiose statement: “I have been called many things over many lifetimes: Ra, Krishna, Yahweh.” And as reported in Time magazine, the line caught the attention of Rajan Zed, a Hindu priest based in Reno, Nevada. “Lord Krishna was meant to be worshiped in temples or home shrines,” he protested, “not for pushing movies for the mercantile greed of filmmakers,” and pressed the director to have all Krishna references deleted from the film.

Zed is the president of an organization called the Universal Society of Hinduism, but—notwithstanding his own rather grandiose styling—it is unclear how many Hindus he actually speaks for. (Along with Time, some South Asian YouTube channels picked up the story, and comments can be found there echoing Zed’s sense of offense; mishearing “Ra” as Ram has added to the grievances of some.) There has been one notable occasion, however, on which Zed attained national visibility as the face of American Hinduism. In 2007 he opened a session of the United States Senate, the first Hindu guest chaplain in its history. Zed’s prayer was interrupted several times from the gallery; news of his invitation, by Harry Reid of Nevada, had been met with an e-mail protest circulated by Christian groups. One senses that American misunderstandings of Hinduism, and prejudice against it, are sources of familiar and enduring concern for Zed.

That being noted, the association of the X-Men’s blue-faced villain with Krishna would seem to owe little to any actual antecedent in Hindu tradition. Or to any Hindu antecedent, that is, that doesn’t already come filtered through layers of American popular culture, including another comic-book franchise. The Apocalypse character dates back to the X-Men stories published by Marvel Comics in the mid-1980s, and his origin story involves motifs borrowed not from Hindu, but Egyptian mythology (whence the Ra reference). But in the same period, perhaps not entirely by coincidence, another blue-complected character emerged at Marvel’s rival, DC—a figure that does show a clear debt to Krishna. The most powerful character in DC’s celebrated “alternative” comics series, Watchmen, is Dr. Manhattan, a philosophically inclined giant whose name and imagery were inspired by the Manhattan Project—and specifically by J. Robert Oppenheimer’s epiphany on viewing the first atomic detonation, as voiced in the words of the Bhagavad Gita: “I am become Death, Destroyer of Worlds.” Dr. Manhattan’s cinematic debut in 2009’s Watchmen was a memorable one. For comic-book fans and other serial viewers of superhero movies, his is surely the definitive combination, to date, of blue skin, portentous rhetoric, and apocalyptic power—the avatar (so to speak) to beat.

Part of Zed’s point has to do with appropriation. Perhaps the right of non-Hindu filmmakers to use imagery that derives its power and appeal from Hindu sources should be challenged. But his contention that Krishna is “meant” to be worshiped in temples, instead of viewed on the movie screen, relies on a too-simple dichotomy. Indian filmmakers have been working with Hindu imagery (and profiting handsomely off it) for over a century. Indeed, in its first decade Indian film production was entirely dominated by the so-called mythological genre. Famously, D. G. Phalke, the “father of Indian cinema,” cast his own daughter in the early classics Shri Krishna Janma (1918) and Kaliya Mardan (1919) in the starring role—none other than that of Lord Krishna.

Over a hundred years of cinema history, the mythological genre has gone through its vicissitudes. One high point was 1961’s Sampoorna Ramayana, “The Complete Ramayana,” a three-hour Hindi-language spectacular featuring songs, stunts, special effects, and the popular wrestler-actor Dara Singh as the epic’s own action hero, the monkey god Hanuman. These days, in northern India, mythological films have largely ceded their place to mythological television, the catalyst having been the phenomenally successful broadcast of a Ramayana series in 1987–88 (Dara Singh—still going strong—again played Hanuman). But the mythological continues to enjoy prominence in the regional cinemas of South India, which have even fostered distinct subgenres centered on mother goddesses and snake deities. And from time and again the gods do still incarnate themselves in A-list Hindi movies. The 2012 Bollywood hit OMG cast the superstar Akshay Kumar as a suave and well-toned modern Krishna at large in Mumbai; when he races his motorcycle through CGI-enhanced nighttime streets, the scene could be mistaken for Gotham City or Metropolis.

And a final point: What goes for movies goes these days for comic books as well. For a long time starting in the 1960s, the Indian comics market had been dominated by the Amar Chitra Katha line of stories adapted from Sanskrit—a children’s series that served up the classics in an easy-to-digest format. But in recent years glossier comics about the gods and epic heroes—flashier graphics, fleshier physiques—have come muscling into the picture. I’ll give the last word here to the interlocutor who first brought home to me the affinity between Hindu gods and American-style superheroes. He was seven years old at the time, and we were speaking in Hindi. “I know all the mans,” he said to me proudly. “Spiderman…Superman…Hanuman!”

Featured image credit: Wooden Krishna at Bangalore Habba by Rajesh dangi. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Portraying Krishna in X-Men: Apocalypse appeared first on OUPblog.

The EU referendum: a reading list

On 23rd June 2016, a referendum will be held in order to decide whether Britain should leave or remain in the European Union. In light of this, we have put together this reading list containing a selection of books and online resources on Europe and the key topics surrounding the debate on the European Union.

Europe’s Long Energy Journey by David Buchan and Malcolm Keay

Europe’s Long Energy Journey by David Buchan and Malcolm Keay

This book explores how far the European Union can go towards forming its 28 member states into an Energy Union. It analyses how the EU can achieve its goal of providing energy affordability, security, and sustainability in the light of internal dynamics in European energy markets, and of the urgency in mitigating climate change.

Eurozone Virtual Issue in The Review of Finance

Publishes high-quality papers in all areas of financial economics. The Virtual Issue addresses a range of topics relating to the Eurozone, such as the effects of the Euro on firm investment rates, systemic risk, mortgage market design, and more.

European Migration by Klaus F. Zimmermann

In recent years, migration has become a major challenge for researchers and policy-makers. The focus has been to investigate the demographics of the movements, the assimilation and integration patterns this process causes, and the effects migrants have on the welfare of the native population. The design of a coherent migration policy is crucial for Europe, which is far behind countries in North America and Australasia. This book summarizes for existing evidence in Europe and contrasts it with the experiences of those countries.

The European Union: A Very Short Introduction by John Pinder and Simon Usherwood

The European Union: A Very Short Introduction by John Pinder and Simon Usherwood

Since the second edition of this popular Very Short Introduction published in 2007, the world has faced huge economic and political change. Showing how and why the EU has developed from 1950 to the present day, John Pinder and Simon Usherwood cover a range of topics, including the Union’s early history, the workings of its institutions and what they do, the interplay between ‘eurosceptics’ and federalists, and the role of the Union beyond Europe in international affairs and as a peace-keeper.

Cultural Integration of Immigrants in Europe edited by Yann Algan, Alberto Bisin, Alan Manning, and Thierry Verdier

This book seeks to address three issues: How do European countries differ in their cultural integration process and what are the different models of integration at work? How does cultural integration relate to economic integration? What are the implications for civic participation and public policies?

Who Needs Migrant Workers? edited by Martin Ruhs and Bridget Anderson

Who Needs Migrant Workers? edited by Martin Ruhs and Bridget Anderson

Are migrant workers needed to ‘do the jobs that locals will not do’ or are they simply a more exploitable labour force? Do they have a better ‘work ethic’ or are they less able to complain? Is migrant labour the solution to ‘skills shortages’ or actually part of the problem? This book provides a comprehensive framework for analysing the demand for migrant workers in high-income countries.

The Oxford Handbook on European Union Law edited by Anthony Arnull and Damian Chalmers

Since its formation the European Union has expanded beyond all expectations, and this expansion seems set to continue as more countries seek accession and the scope of EU law expands,

Worker protection – does it come from the UK or the EU?

There have been a number of contradictory claims made by politicians and in the media as to where our employment laws and worker protection come from, and whether they are European or home grown. Which is correct?

The fact is that, while some come from the EU, and some are domestic, they can often be a mixture of the two, whether they are domestic laws which have then been expanded by Europe, or European laws which are then made more generous by Parliament. There is also the impact of the European Court of Justice, which has helped to reinterpret some elements which were not in British law.

It should first be clarified that the European Convention on Human Rights, which forms the basis of the Human Rights Act, has nothing to do with the European Union. It arises instead as a result of the UK’s membership of the Council of Europe, which we have been in since its inception in 1949. A ‘leave’ vote will have no effect on this. Even if eventually the Conservative government decides to do away with the Human Rights Act 1998, the UK will still be a member of the Council of Europe and still subject to the Convention, unless we also leave the Council of Europe.

UK

There was very little employment legislation before the 1960s or 70s. Around the time that the UK joined the Common Market, more effective domestic anti-discrimination legislation began to appear, such as prohibiting sex and race discrimination, promoting equal pay, and protecting some ex-offenders. Parliament also brought in legislation allowing claims for unfair dismissal and redundancy (collective consultation is EU-based), and protecting health and safety (although this has also since been supplemented by the EU). Provision was also eventually made against deductions from wages, and for sick pay and guarantee pay.

In the 1980s, the Thatcher government brought in the main wave of trade union legislation, which has been amended over the years. The law here is also influenced by the European Convention on Human Rights.

The 1990s brought more anti-discrimination legislation, in the shape of the Disability Discrimination Act, and also Labour’s minimum wage and whistleblowing laws, which are some of the few pieces of employment legislation not to have some European input.

It is difficult in many cases to say that a piece of legislation is purely domestic or purely EU.

More recent years have seen an expansion of family-friendly rights. While many of these have been extended by the EU, the UK did have some maternity legislation to start with, although this originally required the employee to have been employed for a certain length of time first. The extension of paternity leave and adoption leave, as well as shared parental leave and the right to request flexible working are also domestic.

EU

The EU (as it is now) in the meantime also had very little to start with, apart from the principle of equal treatment between men and women. In parallel with domestic law, it developed laws relating to equal treatment and equal pay (which expanded domestic equal pay law by adding the concept of work of equal value), and brought in the idea of transfer of undertakings, which has now been slightly expanded by domestic legislation.

In the 1980s and 1990s the European Court of Justice (ECJ) and the legislature helped to improve domestic discrimination law by protecting pregnant women, and an ECJ decision also led to the amendment of UK law to protect transsexual people.

Further European social legislation was then passed, bringing in protection for fixed-term workers, part-time workers, and eventually agency workers. The working time legislation also derives from Europe. Further anti-discrimination legislation also followed, such as for sex, race, and disability, much of which we already had.

One illustration of how the EU has helped to improve worker protection in this period is that of sexual orientation discrimination. For many years, campaigners and lawyers asked judges to interpret the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 to protect gay people, but the courts were not able to do so. It was not until the European Framework Directive of 2000 that gay people were protected. Similarly, the Directive also covered religious discrimination, which again British lawyers had argued could fit into the Race Discrimination Act 1976, but to no avail. It was therefore not until the Directive was implemented by the UK that sexual orientation and religious discrimination were prohibited, in addition to age discrimination.

The EU has also expanded maternity and pregnancy protection, rights in relation to parental leave, and gave people the right to time off for dependants and in emergencies.

We can therefore see that Employment law as it stands is a thorough mixture of the two types of law, with worker protection coming from both sides. In addition, although some of it originated domestically, and some from the EU, many pieces of legislation have been amended by each side, and so it is difficult in many cases to say that a piece of legislation is purely domestic or purely EU.

(Note that although I have used UK for short, the law in Northern Ireland and sometimes Scotland may differ to that of England and Wales.)

Featured image credit: European Court of Justice (ECJ) in Luxembourg with flags by Cédric Puisney. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Worker protection – does it come from the UK or the EU? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers