Oxford University Press's Blog, page 496

June 24, 2016

What is combinatorics?

Please consider the following problems:

How many possible sudoku puzzles are there?

Do 37 Londoners exist with the same number of hairs on their head?

In a lottery where 6 balls are selected from 49, how often do two winning balls have consecutive numbers?

In how many ways can we give change for £1 using only 10p, 20p, and 50p pieces?

Is there a systematic way of escaping from a maze?

How many ways are there of rearranging the letters in the word “ABRACADABRA”?

Can we construct a floor tiling from squares and regular hexagons?

In a random group of 23 people, what is the chance that two have the same birthday?

In chess, can a knight visit all the 64 squares of an 8 × 8 chessboard by knight’s moves and return to its starting point?

If a number of letters are put at random into envelopes, what is the chance that no letter ends up in the right envelope?

What do you notice about these problems?

First of all, unlike many mathematical problems that involve much abstract and technical language, they’re all easy to understand – even though some of them turn out to be frustratingly difficult to solve. This is one of the main delights of the subject.

Secondly, although these problems may appear diverse and unrelated, they mainly involve selecting, arranging, and counting objects of various types. In particular, many of them have the forms. Does such-and-such exist? If so, how can we construct it, and how many of them are there? And which one is the ‘best’?

The subject of combinatorial analysis or combinatorics (pronounced com-bin-a-tor-ics) is concerned with such questions. We may loosely describe it as the branch of mathematics concerned with selecting, arranging, constructing, classifying, and counting or listing things.

To clarify our ideas, let’s see how various sources define combinatorics.

Oxford Dictionaries describe it briefly as:

“The branch of mathematics dealing with combinations of objects belonging to a finite set in accordance with certain constraints, such as those of graph theory.”

While the Collins dictionary present it as:

“the branch of mathematics concerned with the theory of enumeration, or combinations and permutations, in order to solve problems about the possibility of constructing arrangements of objects which satisfy specified conditions.”

Wikipedia introduces a new idea, that combinatorics is:

“a branch of mathematics concerning the study of finite or countable discrete structures.”

So the subject involves finite sets or discrete elements that proceed in separate steps (such as the numbers 1, 2, 3 …), rather than continuous systems such as the totality of numbers (including π, √2, etc.) or ideas of gradual change such as are found in the calculus. The Encyclopaedia Britannica extends this distinction by defining combinatorics as:

“the field of mathematics concerned with problems of selection, arrangement, and operation within a finite or discrete system … One of the basic problems of combinatorics is to determine the number of possible configurations (e.g., graphs, designs, arrays) of a given type.”

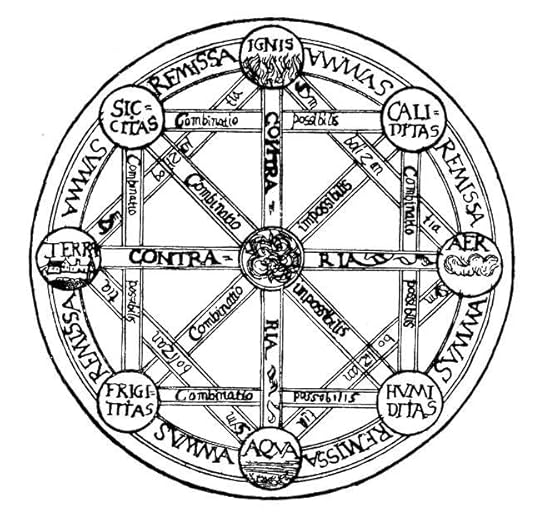

Leibniz’s representation of the universe resulting by combination of Aristotle four elements. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Leibniz’s representation of the universe resulting by combination of Aristotle four elements. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Finally, Wolfram Research’s MathWorld presents it slightly differently as:

“the branch of mathematics studying the enumeration, combination, and permutation of sets of elements and the mathematical relations that characterize their properties,”

adding that:

“Mathematicians sometimes use the term ‘combinatorics’ to refer to a larger subset of discrete mathematics that includes graph theory. In that case, what is commonly called combinatorics is then referred to as ‘enumeration’.”

The subject of combinatorics can be dated back some 3000 years to ancient China and India. For many years, especially in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, it consisted mainly of problems involving the permutations and combinations of certain objects. Indeed, one of the earliest works to introduce the word ‘combinatorial’ was a Dissertation on the combinatorial art by the 20-year-old Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in 1666. This work discussed permutations and combinations, even claiming on the front cover to ‘prove the existence of God with complete mathematical certainty’.

Over the succeeding centuries the range of combinatorial activity broadened greatly. Many new types of problem came under its umbrella, while combinatorial techniques were gradually developed for solving them. In particular, combinatorics now includes a wide range of topics, such as the geometry of tilings and polyhedra, the theory of graphs, magic squares and Latin squares, block designs and finite projective planes, and partitions of numbers.

Much of combinatorics originated in recreational pastimes, as illustrated by such well-known puzzles such as the Königsberg bridges problem, the four-colour map problem, the Tower of Hanoi, the birthday paradox, and Fibonacci’s ‘rabbits’ problem. But in recent years the subject has developed in depth and variety and has increasingly become a part of mainstream mathematics. Prestigious mathematical awards such as the Fields Medal and the Abel Prize have been given for ground-breaking contributions to the subject, while a number of spectacular combinatorial advances have been reported in the national and international media.

Undoubtedly part of the reason for the subject’s recent importance has arisen from the growth of computer science and the increasing use of algorithmic methods for solving real-world practical problems. These have led to combinatorial applications in a wide range of subject areas, both within and outside mathematics, including network analysis, coding theory, probability, virology, experimental design, scheduling, and operations research.

Featured image credit: ‘Sudoku’ by Gellinger. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post What is combinatorics? appeared first on OUPblog.

June 23, 2016

Managing the time warp of loss: why do they want to marry the widow off

How does a widow see her future? What can a widow see in the present?

My late husband Gene D. Cohen is considered a founding father of Geriatric Psychiatry and the grandpappy of the field of Creativity and Aging. With his son and our daughter, I went to Chicago to receive his Hall of Fame Award, only four months after his passing. Being married to someone famous, who passes away just five weeks into his 65th year, after devoting his entire career to the understanding and creative potential of people 65 and older, is a loss not only to those of us who are his family, but to the many colleagues and protégés in the field.

It seems to comfort friends to see me as OK; they say I am intelligent, bright, beautiful, young (they think, but I am 60, is that young?). They like to envision another chapter awaiting me. Although I know they have my best in mind, I am clear that this thought is more consoling for them than for me; it also erases my existence. I cannot imagine a future because the present is still filled with a need for stamina. Thoughts of “new life, new passions, new people” feel unsafe to me. I don’t want to be moved out of the “now” and into the “then”. Because I have walked the full distance of responsibility in caretaking, all the way up to the moment of death, the choice to walk with another is not an intimacy I dare take on again. The experience is a deep responsibility and a shared exchange that I can’t imagine repeating.

When our parents die, no one tries to comfort us by saying, “You can love like this again with a new mother, new father, or a different grandparent.” Yet, with the loss of a spouse, people quickly start talking about a new companion, a new sexual partner, a new friend. Or it seems quick to me; some people may truly be comforted by the possibility of being loved and cared for by someone again but for me, it feels unsafe. I could explain it by saying that Gene was rare, that he was my true love, or that Gene was the right husband for me. But I don’t think this truth is the reason for what I experience. It’s much more existential than that: I have gone through the door of death and over the edge.

“Both/And” (2002), carved alabaster on stone slab,12 x 9 x 7 inches. Artwork by Wendy L. Miller. Photo credit: Claire Blatt. Image used with permission.

“Both/And” (2002), carved alabaster on stone slab,12 x 9 x 7 inches. Artwork by Wendy L. Miller. Photo credit: Claire Blatt. Image used with permission.So, I do not find it hopeful or comforting when people say to me, “Ah yes, you will do that again once you get through this period. You are young, you have more time, more spunk, and more energy within, more love to give and to receive.” The truth is, it is comforting to them to believe that—to imagine that death does not take everything away, that we recover from what we have lost, that life goes on and on. And maybe the real desire in such a message is that we do not die. But we do. He did.

To me, what is comforting is to honor the deep intimacy I have whether my husband is here or not. I don’t want people to ask me to move on, move over, move anywhere. I don’t want to build a shrine to a past nor do I want to be told there is a future. I want to stand in what is and have it still throb with its own breath, its own memories. I want preservation and conservation. I want to float in the beauty of the creative life we built. I want to stay in our life together, a life that I seeded with him.

There is a huge community of care around me. It’s a wonderful source of support, gratitude, and love. But there is an edge to the grieving process that is difficult to articulate. It sounds ungrateful, mean, even selfish, but I think it needs to be said out loud because grieving is a universal process, one that requires informed exchanges of love and understanding.

So, allow me, please: Stop telling me of a different future. Stop telling me who I can become, might become, or should become. Stop placing your anxiety on me. I have enough to carry right now. I am carrying the death of love, the death of body, the death of marriage, the death of shared parenting, the death of wholeness, the death of friendship, the death of a well-built, well-traveled journey together.

I reject your images of what my grief should look like to you. From this side of the opened door, I can say that you cannot possibly understand what my reality is like or you would not offer me solutions. The loss of the intimacy, love, identity, essence, partnership I have known with Gene is what I am processing; nothing can be more intimate than holding the soul and essence of a loved one at the time of death. No one would ever ask us to move on from such awe-filled moments as when our child is born, when our choice of partnered love is born, when our shared identities are born. No one would ever ask us to imagine new moments for these rites of passage. Yet our culture doesn’t allow death to have the same respect.

Please remember, when you stand by your grieving friend, you cannot take her pain away with your belief that another life will help her feel better. What feels best is to stand beside your friend, knowing that you can’t imagine her grief—not just the loss, but the intimacy; not just the pain, but the closeness; not just the loneliness, but the aloneness.

The shared presence of listening is your real gift. Be in awe that your friend has been touched by some vital essence and will never be the same again.

Featured image credit: Sunset by diego_torres. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Managing the time warp of loss: why do they want to marry the widow off appeared first on OUPblog.

LGBT Pride Month: A reading list on LGBT older adults

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Pride Month is celebrated annually in June to commemorate the 1969 Stonewall riots. The Stonewall Inn in New York City’s Greenwich Village was one of the city’s few gay bars or nightclubs at that time. In the wee morning hours of 28 June 1969, police raided the bar, triggering protests among members of the LGBT community. The riots that erupted in New York and beyond captured the long-standing feelings of anger and disenchantment among members of the gay community, who were frequently subjected to discriminatory, hateful, and even violent treatment.

The Stonewall riots were a tipping point in LGBT history, setting the stage for the creation of LGBT Pride Month. Each June, the United States celebrates the LGBT community with parades, festivals, and teach-ins. The 2016 celebration will be especially noteworthy, as President Barack Obama prepares to designate the Stonewall Inn as the first national monument dedicated to gay rights.

Protesters at Stonewall were at the vanguard of the LGBT movement, and most are older adults today. Social gerontologists recognize the importance of identifying the sources of health, well-being, and resilience among older gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender older adults. Many “came out” as young adults in an era when same-sex relations were frowned upon (if not illegal). Others remained “in the closet,” never anticipating that five decades later they would have the legal right to marry. Roughly 1.5 million Americans ages 65 and older identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender. In celebration of LGBT Pride Month, and in honor of older LGBT Americans, we have created a reading list of recent articles from Gerontological Society of America journals that reveal the challenges and joys of older gays, lesbians, bisexual, and transgendered older adults.

The Physical and Mental Health of Lesbian, Gay Male, and Bisexual (LGB) Older Adults: The Role of Key Health Indicators and Risk and Protective Factors, by Karen I. Fredriksen-Goldsen, Charles A. Emlet, Hyun-Jun Kim, Anna Muraco, Elena A. Erosheva, Jayn Goldsen, and Charles P. Hoy-Ellis in The Gerontologist.

This study investigates the influence of risk and protective factors on health outcomes (including general health, disability, and depression) among lesbian, gay male, and bisexual (LGB) older adults. The results show that lifetime victimization and financial barriers to health care are linked with poor general health, disability, and depression, while internalized stigma also predicts disability and depression. Social support and having a large social network protect against poor health, disability, and depression. Tailored interventions should address the distinct health issues facing these historically disadvantaged populations.

Successful Aging Among LGBT Older Adults: Physical and Mental Health-Related Quality of Life by Age Group, by Karen I. Fredriksen-Goldsen, Hyun-Jun Kim, Chengshi Shiu, Jayn Goldsen, and Charles A. Emlet, in The Gerontologist.

The researchers investigate factors associated with subjective evaluations of physical and mental health-related quality of life (QOL), which are considered important indicators of successful and healthy aging. Discrimination and chronic health conditions reduced both physical and mental health QOL, whereas social support, having a larger social network, participating in physical and leisure activities, not using substances, being employed, and having higher income were associated with better physical and mental health QOL. Mental health QOL, in particular, was enhanced by a positive sense of sexual identity. These patterns differed across age groups, where discrimination was particularly harmful to those ages 80+, revealing the distinctive experiences of different cohorts of LGBT adults.

The Intergenerational Relationships of Gay Men and Lesbian Women, by Corinne Reczek in Journals of Gerontology: Psychological and Social Sciences.

The author conducted 50 in-depth interviews with older gay men and lesbians (ages 40–72) in long-term intimate partnerships. The respondents discussed positive and negative aspects of their relationships with their parents and parents-in-law. They named four supportive factors in their relationships: integration, inclusion through language, social support, and affirmations. By contrast, strained intergenerational relationships were marked by rejection in everyday life, traumatic events, and the threat of having the couples’ wishes ignored if either partner were compromised with a health issue. These findings provide a new lens viewing adult intergenerational relationships.

Physical and Mental Health of Transgender Older Adults: An At-Risk and Underserved Population, by Karen I. Fredriksen-Goldsen, Loree Cook-Daniels, Hyun-Jun Kim, Elena A. Erosheva, Charles A. Emlet, Charles P. Hoy-Ellis, Jayn Goldsen, and Anna Muraco, in The Gerontologist.

This study used data from a cross-sectional survey of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults aged 50 and older to examine the ways that gender identity affects physical health, disability, depressive symptoms, and perceived stress. Transgender older adults were at greater risk of poor physical health, disability, depressive symptomatology, and perceived stress compared with other study participants. The researchers call for individual and community-level social support when developing programs to address transgender older adults’ distinct health and aging needs.

Older Gay Men and their Quality Support Convoys, by Griff Tester and Eric Wright, in Journals of Gerontology: Psychological and Social Sciences.

The researchers investigate the social networks of 20 older gay men in Atlanta, using both network mapping strategies and in-depth interviews. Study participants said that having people in their lives with whom they could fully be “out” as gay men (authenticity) was at the root of a quality network. Although older gay men have contact with their biological families, for many older gay men, family is not central to their lives. Rather, some described a queer construct of family, which emphasizes social practices and “doing” family-like things, rather than “being in/out” of a narrowly defined institution.

Living Arrangement and Loneliness Among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Older Adults, by Hyun-Jun Kim and Karen I. Fredriksen-Goldsen, in The Gerontologist.

The researchers examine the ways that living arrangements affect loneliness among LGB older adults. Types of living arrangements include living with a partner or spouse, living alone, and living with someone other than a partner or spouse. Those living alone and living with others reported higher degrees of loneliness. These gaps are partly explained by social support, having a larger social network, and internalized stigma. The authors call for eliminating discriminatory policies against same-sex partnerships and partnered living arrangements.

Featured image credit: Stonewall Inn, West Village by InSapphoWeTrust. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post LGBT Pride Month: A reading list on LGBT older adults appeared first on OUPblog.

The Broadway song that nominated a president

The astounding success of Hamilton, its capacity to engage audiences from third graders to the president and first lady, reminds us that Broadway musicals have a healthy tradition of mining political history. From 1776 to Evita, songwriters have been fascinated by political power. What drives people to become leaders? How do they rally supporters around them? What reservations do they have about their failures and successes? From costumes to choreography to the musical score, Broadway storytellers have amazing tools at their disposal, but as Lin-Manuel Miranda might agree, nothing attracts an audience like a tale of scrappy ambition carved out of the past.

Irving Berlin’s Call Me Madam stands the traditional partnership between politics and musical theater on its head. Although based on real life events, the musical played a special role in the making of American history. Long before Dwight Eisenhower had joined a political party, let alone agreed to run for office, Call Me Madam was advocating for an Eisenhower presidency, and evidence suggests that Berlin’s musical significantly contributed to his election.

Call Me Madam opened at New York’s Imperial Theater in October 1950, with Ethel Merman starring as a Washington socialite who becomes the American ambassador to the fictional country of Lichtenburg. Although the focus remains with Merman’s character, Sally Adams, the show featured a catchy tune midway through the second act in which two senators and a congressman speculate about the upcoming presidential race. As the Democrats boast that the combative Harry Truman would hold the White House for another term, the Republican asserts that his party has set their sights on running a more affable candidate: “They like Ike/ And Ike is good on a mike./ They like Ike.”

When the Democrats interrupt, “—But Ike says he don’t wanna,” the congressman wittily replies: “That makes Ike/ The kind of fella they like!/ And what’s more/ They seem to think he’s gonna.” In each verse, the Democrats list various reasons why Truman will win, but the chorus always comes back to the simple Republican theme: “They like Ike.”

Irving Berlin 1906: Publicity photo of Irving Berlin taken by his early music publishing company for promotion. By Life magazine images – Book: Life: Our Century in Pictures (2000). Public Domain via Wikipedia Commons.

Irving Berlin 1906: Publicity photo of Irving Berlin taken by his early music publishing company for promotion. By Life magazine images – Book: Life: Our Century in Pictures (2000). Public Domain via Wikipedia Commons.The phrase “They like Ike” had occurred to Berlin when he met Eisenhower in London in 1944, and Call Me Madam provided just the opportunity to develop it into a song. The Tony Award-winning musical was a hit, and although it had nothing to do with the storyline, the power of “They Like Ike” was immediately evident. After seeing an early performance, the syndicated columnist Inez Robb described the song as “one of the greatest political windfalls ever to fall like manna upon a presidential possibility.” “They Like Ike,” she predicted, would “sweep the general into the White House.”

The problem for Eisenhower supporters, however, was that the general had no intention of running for president and barely tolerated the Draft Eisenhower movement that was spreading across the country. Berlin’s lyrics took on new significance when, in January 1952, Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge entered Eisenhower’s name in the New Hampshire Republican primary. Stationed in Paris as Supreme Commander of NATO, Ike took to his journal and cursed. Back in New York, Berlin quickly revised his lyrics to fit the voice of Eisenhower’s many fans: “I like Ike/ And Ike is easy to like/ Stands alone/ The choice of We the People.”

Over the course of the campaign and, indeed, over the next sixteen years, Berlin used the song to reflect changing circumstances. When Joseph McCarthy endorsed Eisenhower’s chief Republican opponent, Ohio Senator Robert Taft, the Call Me Madam cast sang: “McCarthy’s backing Taft? / That’s the kiss of death!” After Ike’s victory in November, the show’s disillusioned Democrats bemoaned “how many changed their minds down at the polls.” As late as 1968, Berlin was changing the lyrics to address the Vietnam War and the wide-open presidential contest. The chorus, however, stubbornly clung to a candidate from the 1950s: “We still like Ike.”

Berlin and the cast of Call Me Madam played a prominent role in a February 1952 rally for Eisenhower held in Madison Square Garden. In order to accommodate a previously scheduled boxing match, the organizers began the rally at 11:30 pm after the boxing fans had departed the building and over 15,000 Eisenhower supporters had flooded in. After the curtain fell at the Imperial Theater, cast members joined such stars as Clark Gable, Humphrey Bogart, and Lauren Bacall in offering their support. (Bogart and Bacall would eventually switch their endorsement and campaign for Eisenhower’s Democratic opponent, Adlai Stevenson). Ethel Merman belted out “There’s No Business Like Show Business” and danced with the chorus master Fred Waring. Berlin debuted his new version of “I Like Ike,” while the actor who played Harry Truman appeared in costume, comically wagging a disapproving finger. As if politics were a combination of pugilism and show business, all of the proceedings took place within the Garden’s boxing ring.

Critics hated the rally, denouncing it as cheap, vulgar, and “an expression of really outrageous cynicism,” but Berlin’s song swept across the country. Herbert Brownell, who served as Eisenhower’s Attorney General, concluded that the song’s popularity helped convince the general that the time was right for a presidential bid. Seeing a recording of the rally a few days later in Paris, Eisenhower wept. By June, he had returned to the United States to take his shot at the presidency.

We do not know what Lin-Manuel Miranda’s influence on our politics will be, but if he proves to be as determined and astute as Berlin, it could be substantial. And as we read about Neil Young, The Rolling Stones, and REM trying to reclaim their music from the Donald Trump campaign, we might remember the power of song not only to represent America, but also to shape it.

Featured image: Broadway Street Sign. Image by Damzow via Wikimedia Commons, CC SA 3.0.

The post The Broadway song that nominated a president appeared first on OUPblog.

June 22, 2016

God and clod

In an old post, I once referred to Jack London’s Martin Eden, a book almost forgotten in this country and probably in the rest of the English-speaking world. Martin is not Jack London’s self-portrait; yet the novel is to a great extent autobiographical. The protagonist, in the beginning an uncouth and uneducated sailor, becomes a famous writer. One of his essays, devoted to the nature of realism in fiction, bears the title “God and Clod” (Chapter 27). I also have to say something about clod, but as an object of etymology.

In my case, the clod and the plot I am about to investigate began with the history of the verb clutter, or rather with Middle High German verklüteren, which occurs in Gottfried’s Tristan; it is glossed as “to confuse, bewitch.” Isolde, who used the word while berating Tristan before the two drank the love potion, meant that Tristan had cluttered her mind with vicious blandishments. I looked up clutter in etymological dictionaries and found myself in a morass of kl-words referring to dry and liquid dirt.

Isolde thought that Tristan had obfuscated, cluttered her mind, but he did not. Both ended up as playthings of fate.

Isolde thought that Tristan had obfuscated, cluttered her mind, but he did not. Both ended up as playthings of fate.Clutter “clotted mass” turned up in English texts only in the sixteenth century, but Chaucer already knew clotter, and in the fifteenth century clodder had some currency. It does not come as a surprise that, while discussing clutter, dictionaries mention clot and clod. Clot, at present mainly associated with clotted blood, goes back to Old English and reminds us of its German counterpart Klotz “a great lump; chunk” (also, a disrespectful name for a certain kind of person), Engl. cleat “wedge,” and clout “patch; piece of cloth, etc.” If we keep following the cross-references in our most reliable sources, we will discover not only clod (which, despite its final -d, began its history in English with the sense “clot of blood,” yet developed into “lump of earth” and, somewhat unexpectedly, into “stupid person”—not quite a synonym of German Klotz, but sharing a strong aura of disapproval with it) but also cloud. Cloud surfaced in Old English and meant “hill, rock; block,” which is somewhat reminiscent of Klotz “chunk.” In the thirteenth century, cloud came to mean what it does today and superseded its synonym wolken, still recognizable in the obsolete noun welkin “sky.” Modern German and Dutch have Wolke and wolk “cloud” respectively. However, the connection between clod and cloud is hard to establish because of the semantic leap from “hill, rock” to “a mass of vapor in the air.”

The profanity of disease

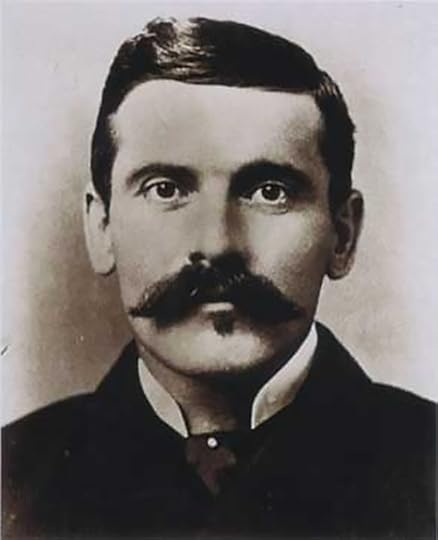

Over spring break, I spent a day in Tombstone, Arizona. This is the town where, if you don’t know the story, Wyatt Earp and his brothers, accompanied by their friend Doc Holliday, had a shootout with a group of cattle rustlers at the OK Corral. Though the Earp brothers wore the badges, when the tale is told the hero is usually Doc Holliday—noted gambler, crack shot, prodigious drinker, educated southern gentleman, dying all the while of tuberculosis. Contemporary accounts (1880s) of his exploits occasionally refer to him as “consumptive,” but in the 1993 movie Tombstone and the 2015 book Epitaph by Mary Doria Russell, various characters deride him as a “lunger.” According to the OED, the first recorded use of lunger is in 1893, and it reflects an interesting change in societal attitudes to people with tuberculosis. Pre-1880, tuberculosis was mysterious, a possibly inherited condition thought to bestow on sufferers a heightened sensitivity and creativity. The physical frailty and paleness it produced were beautiful in the Romantic imagination—Byron declared to a friend that he “should like, I think, to die of consumption.” In 1882, however, the year after the Tombstone shootout, Robert Koch discovered that tuberculosis was caused by a bacterium, and very contagious. Quite suddenly, it transformed from interesting condition to terrifying disease. English-speakers needed a new epithet to sum up and distance themselves from sufferers in order to ward off, linguistically, the disease and the diseased—hence lunger.

Through the centuries, English has had other derogatory terms and swearwords based on disease, but they have never made up a large proportion of our bad words. Other languages—Dutch and Yiddish, for example—have much stronger and more elaborate disease-related swearing. Nevertheless, English-speakers of the past could choose from a few options, depending on what illnesses were most feared at the time.

John Henry “Doc” Holliday, dentist and gambler, an ally of the Earps at the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. Photographer unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

John Henry “Doc” Holliday, dentist and gambler, an ally of the Earps at the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. Photographer unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.While leprosy has been known since Greek and Roman times, and plays a thematic role in the Bible, the disease spread especially widely in medieval England. Society was of two minds about it. On one hand, it was so horrible—in its most famous form, Hansens’ disease, the bacterium “rots” a person’s extremities and can chew through bone—that lepers were thought to be holy people imitating Christ’s passion, living a life of such suffering on Earth that they would go directly to heaven after death. On the other hand, the disease was sometimes imagined as God’s punishment for sin (usually some sort of heresy), the physical disfigurement a mark of inner foulness. Terms for sufferers of the disease reflected this dichotomy. Leper and lazar seem to have been the more standard, unmarked terms. Lazar especially has connotations of sanctity, as it is derived from Lazarus, who in Luke 16:19-31 begged outside a rich man’s door and was carried away by angels to heaven after death (while the rich man who ignored him went to hell). Another Lazarus was resurrected by Jesus, serving as the final evidence (in the Gospel of John) that Christ was truly the son of God, and receiving sainthood for his trouble.

In contrast, mesel, another term for a person afflicted with leprosy, skews derogatory. One character in the 14th century romance Amis and Amiloun tells another: “Fouler mesel there was never…than thou shall be!” And in 1386, Chaucer’s Parson, whose tale is one long moral treatise, declares that it is a sin to chide or make fun of one’s neighbor, “as Mesel, crooked harlot…” Mesel here is obviously an insult, not intended to evoke the holy suffering of leprosy.

Historically, the strongest disease-related insult in English was pox. This sometimes referred to smallpox, but more often was used for syphilis, known as the “Great pox” or the “French pox” (meanwhile, in France, it was mainly called the “Neapolitan disease,” but the Spanish and the English also came in for a share of the blame). When European colonists brought smallpox to the native Americans in the 16th century, they picked up syphilis in return. The disease spread widely in the 16th-19th centuries, and its effects were terrible—patients got widespread, weeping rashes all over their bodies, which in a third of cases went on to eat away parts of bone and produce soft tumors, causing nerve pain and cardiac problems as well as facial deformity. William Davenant, a 17th century playwright, poet laureate, and friend of King Charles I, lost his nose to syphilis in 1632, and his contemporaries never let him forget it—he was followed by nose jokes for the rest of his life.

Q: Why does Davenant have a grudge with Ovid?

A: Because his Sirname is Naso [“nose” in Latin].

William Davenant, operator of one of the first licensed theatre companies after the Restoration of Charles II in 1660. From The Works of Sir William Davenant, frontispiece, printed by TN for Henry Herringman, London, 1673. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

William Davenant, operator of one of the first licensed theatre companies after the Restoration of Charles II in 1660. From The Works of Sir William Davenant, frontispiece, printed by TN for Henry Herringman, London, 1673. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Joking aside, the French pox was widely stigmatized because it was known to be sexually transmitted, and was thus interpreted as a sign of loose morals. This apparently didn’t do Davenant any harm, but for many people, being called “pox-ridden” or “poxy” could destroy their reputation. A woman might lose marriage prospects; a working man might lose business, if his moral probity was suspect. Thus pox-insults were actionable under English common law—in the 17th and 18th centuries especially, people were sued for defamation for saying things like “thy wife is a scurvie [“diseased”] pocky queane [“prostitute”]… she hath the French pockes and I say so still” or “whore, pocky whore, burnt Arst whore” (“burnt-arsed” also refers to venereal disease).

Pox is the only one of the words we’ve been discussing that might actually be considered a swearword. Unlike lunger and mesel, it could be used in a variety of ways. It was an insult, as we’ve seen, but could also be a curse: “Pox take you!” or “Pox on you for a fool!” It could be used non-literal interjections (“O Pox!”, like “Damn it!”) and as intensifiers (“this pockie stuff!”, like “this fucking stuff!”). In the 18th century, authors and publishers of more delicate sensibilities sometimes partially censored it, as with other mild swearwords such as bl—dy and d—n. In 1756, one critic so deplored the book he was reviewing that he declared, “A p-x on such writing!”

The biggest difference between pox and other words like lunger and mesel, though, is that pox and its adjectives are not epithets. Today some of our worst, most taboo, most emotionally charged words are epithets—nigger, for example, is considered by most people to be the “worst” word in the English language; paki, a derogatory term for people of Southeast Asian origin, is extremely offensive in the UK. For us today, it is taboo to sum up and label people on the basis of race, size (“fat”), or mental acuity (“retarded”). In the past, however, that was simply what one did. Epithets were, of course, sometimes still hurtful to the people so addressed, but there was little wider cultural consciousness that such words were painful and harmful or that it might be preferable not to use them. So lunger and mesel, though derogatory and insulting, probably did not have the emotional charge of true swearwords, unless you too were beautifully pale and coughing up bright red blood.

Featured image: “Leprous Beggars” from A Dictionary of the Bible (1887) by Philip Schaff. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons/Library of Congress.

The post The profanity of disease appeared first on OUPblog.

Global footprints of Indian multinational corporations

While Western multinational corporations (MNCs) have traditionally taken their domestic strengths ‘outward’ to the rest of the world to exploit already existing firm-specific competitive advantages, the multinational from emerging economies have no such pre-existing strengths and therefore, their motive for internationalization is primarily to acquire competitive advantages that they lack, such as marquee brands and managerial expertise. Most of their overseas growth has occurred in the last decade or so and in a very short span of time, they have spread their global network, mainly via acquisitions in a constant cycle of ‘linkage, leverage, and learning’.

Indian multinationals have been quick learners in internationalization both in scale and speed. One of the core strengths of Indian firms is to extract maximum value from even ailing businesses by applying innovative and cost effective methods that they have developed over the years in an extremely resource constrained and uncertain domestic environment. Their unique approach to international growth, which some label as ‘compassionate capitalism’ manifests in several ways, such as a preference for sustainable growth without compromising core values, long-term commitment to their businesses despite economic turbulences, faith in the management team of the acquired overseas companies and commitment to employees in terms of job security and investment in training. The ‘fire in the belly’ attitude of emerging multinationals is evident in the way they are pushing the top management in the companies that they have acquired abroad to stretch their goals.

Indian MNCs do face multiple hurdles in furthering their internationalization strategies

While their management philosophy is grounded in Indian heritage that focuses on social mission and employee welfare, they have adopted several best practices from developed markets, such as metrics driven performance management. However, unlike Western multinationals which tend to adopt an ethnocentric approach to managing subsidiaries in developing markets, Indian multinationals seem to adopt a highly localized approach as reflected in their staffing and decision making process. They also show clear signs of an ‘adaptive approach’ in managing subsidiaries in developed markets.

Indian MNCs do face multiple hurdles in furthering their internationalization strategies. For example, despite attempts to localize their workforce in different geographies, their global management team is still predominantly Indian but increasingly their systems and to some extent their management mindset are becoming global. They also tend to centralize decision making power in the headquarters for fear of losing control. They recognize that to become a truly global corporation, they need to develop a global mindset and employee base. While this vision is being somewhat hampered by the liabilities of country of origin, foreignness, newness and smallness, they are steadily acquiring the critical mass to differentiate themselves as innovative global players.

With regard to human resource (HR) strategies and practices, Indian multinationals are clearly focused on linking HR strategy to business strategy and harnessing the potential of intellectual capital by creating an environment of trust and transparency, adopting a long-term vision in managing performance and business cycles, investing heavily in employee training, providing internal growth opportunities, empowering employees, integrating people, culture and systems, and being a good corporate citizen by working with and for the local communities.

Increasing investment by emerging economies in developed as well as emerging markets, particularly via mergers and acquisitions means that there is a greater need for management practitioners to understand the ways in which MNCs from emerging economies strategize and act in diffusing and coordinating management practices. For too long, international management literature and practice have been embedded in Western thinking and concepts with little cross-pollination. Accordingly, reexamining the management approaches and practices of MNCs from newer industrialized and developing economies such as India that facilitates ‘travel of ideas’ is likely to remain a key research issue for the next decade, given the speed of economic development and the increasing influence and numbers employed by such companies. Accordingly, the India model is worth considering in drawing lessons on how to navigate the changing contours of the 21st century global economy.

Featured image credit: Delhi city smog, by wili hybrid. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Global footprints of Indian multinational corporations appeared first on OUPblog.

June 21, 2016

17 US foreign relations must-reads

The annual meeting of the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations (SHAFR) begins this week in San Diego. Are you caught up on your reading? If not, have no fear! We’ve put together a list of your SHAFR “must-reads,” including Diplomatic History’s most popular articles from the past year and a selection of recent books and blog posts on US foreign relations.

Picks from Diplomatic History, the official journal of SHAFR

“Take Me to Havana! Airline Hijacking, U.S.–Cuba Relations, and Political Protest in Late Sixties’ America” by Teishan A. Latner

From 1968 to 1973, amidst a period of social upheaval, Cuba unwittingly became the world’s most popular place to land a hijacked plane. In five years, “skyjackers” made over 90 attempts to commandeer airplanes from the United States to Cuba. A majority of hijackers were American—from draft dodgers, to activists, to asylum-seekers, to petty criminals. They were drawn to an idealized image of Cuba as a revolutionary’s haven, which rejected capitalism and defied America’s global domination. The situation led to unprecedented diplomatic collaboration between America and Cuba as they crafted a mutual anti-hijacking agreement.

“Presidential Address: Structure, Contingency, and the War in Vietnam” by Fredrik Logevall

In his presidential address, Frederik Logevall traces the history of the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations alongside the Vietnam War. Almost half a century ago, the society was founded in the throes of the Vietnam War. Today, they study the Vietnam War as history. An outpouring of scholarship reflecting on the war has been produced in the past several decades, but Logevall addresses one question: “How do we account for the reality [that] three American presidents… escalated and perpetuated a war in Southeast Asia that they privately suspected was neither winnable nor necessary?”

“Local People’s Global Politics: A Transnational History of the Hands Off Ethiopia Movement of 1935” by Joseph Fronczak

In 1935, a transnational social movement transformed the dynamics of global politics. When the Italian Fascist régime threatened to invade Ethiopia, leftists across the world leaped to the country’s defense. With the Hands Off Ethiopia campaign, the new “global left” utilized informal political practices, including mass meetings, street fights, riots, and strikes. Unled, unorganized, and unstructured, the group showed that common people could directly assert themselves in matters of international affairs. Though their antiwar efforts failed to prevent Ethiopia’s invasion, Hands Off Ethiopia created lasting effects on international history continuing beyond the postwar era.

Cuba-Florida Map. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Cuba-Florida Map. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.“The Imperialism of Economic Nationalism, 1890–1913” by Marc-William Palen

Through his article, Palen looks to debunk a laissez-faire myth that revolutionized imperial studies. Since 1953, a theory that American imperialism surrounding turn-of-the-century foreign relations had a “free-trade character” has become popular. Palen argues that this revisionist interpretation has prevailed “despite the predominance of economic nationalism” during the time period. If the American Empire arose out of imperialism of economic nationalism, rather than imperialism of free trade, then how did this free-trade, open-door theory become such a steadfast fixture within US history?

“Embracing Regime Change in Iraq: American Foreign Policy and the 1963 Coup d’état in Baghdad” by Brandon Wolfe-Hunnicutt

Following a 1958 coup d’état in Iraq, the Middle East was in flux and American policymakers struggled to respond. They were divided into two camps: one accommodating faction believed that, through skillful diplomacy and a robust program of development assistance, the United States could convince the new regime to protect “Western interests.” Another interventionist faction worried that new leadership would destabilize order in the region, and hoped to restore a “reliable client regime” in Iraq instead. US policy vacillated between these two factions for five years, but eventually sided with the interventionists. The Kennedy administration pursued a regime change in the name of national security—but Wolfe-Hunnicutt suggests that interventionists’ warnings of a “Communist threat” in Iraq were actually a cover for more base motives.

Picks from our books

Your Country, My Country – Offers a chronological comparative history of both Canada and the United States, with new insights for readers on both sides of the border.

Executing the Rosenbergs – A look at the Rosenberg case from how it was reported and protested around the world. Citing never before used State Department documents that focus on the ways in which the Rosenberg case reflected America’s role in the world.

Legalist Empire – Shows the role of international lawyers in the making of American empire in the late 19th and first half of the 20th century.

Holocaust Angst – An account of attempts by German political actors to grapple with American Holocaust memory and reshape Germany’s public image abroad.

From Empire to Humanity – Roots the origins of humanitarianism in the fracturing of the British Empire as a result of the American Revolution.

Choosing War – Provides the only comparative analysis of presidential crisis decision-making and naval incidents.

The Guardians – Accesses the mandates system based on original research, undertaken on four continents and in numerous archives.

The Oxford Handbook of the Cold War – Thirty four essays from an international team of scholars providing a broad reassessment of the Cold War based on the latest research in international history.

Close up of Jimmy Carter and German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, July 1977. Public domain via The US National Archives.

Close up of Jimmy Carter and German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, July 1977. Public domain via The US National Archives.Picks from the OUPblog

Queering America and the world – On the important (and often unexamined) role of queer history in the study of US diplomatic relations.

The ideology of counter-terrorism – Mary Barton discusses the United States and international anarchist terrorism from the 19th century through the present day.

A prickly pair: Helmut Schmidt and Jimmy Carter – Helmut Schmidt and Jimmy Carter had one of the most explosive relationships in postwar, transatlantic history, straining to the limit the bond between West Germany and America.

Can history help us manage humanitarian crises? – A look at the parallels between America’s reaction to Jewish refugees during World War II and Syrian refugees today.

Image credit: Signing of the preliminary Treaty of Paris by John D. Morris & Co. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 17 US foreign relations must-reads appeared first on OUPblog.

The Brandeis confirmation a century later

June 2016 marks the 100th anniversary of the confirmation of Louis D. Brandeis to the U.S. Supreme Court. The first Jew to serve on the court and one of the most respected and revered justices in our history, his opinions on free speech, due process, and fundamental liberty are still widely quoted and cited. Before going on the Court his representation of poor people, exploited workers, women’s rights organizations, and the public interest, helped make America a more humane and just nation, while forcing banks, railroads, public utilities and other large business to be more fair to the public. In 1916, he was known throughout the nation as “The People’s Lawyer.” He was the forerunner of other social activist lawyers who were later appointed to the Court, such as Thurgood Marshall and Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

His confirmation took four months, the longest in history. Brandeis’s ethnicity was an issue for politicians and anti-Semitism swirled around the process. But in the end the Brandeis nomination was a historical turning point, definitively undermining anti-Semitism in American political culture, even though that toxic animus still lingers in some quarters of American society.

The Brandeis nomination came in an election year, and at a time when it seemed likely that President Woodrow Wilson might not be reelected. Since the reelection of Grant in 1872, only one other sitting president, William McKinley, had been reelected for a second term. Moreover, other than Wilson, the only Democrat elected since the Civil War had been Grover Cleveland. In 1912 Wilson won only 6.3 million votes against a divided Republican Party, with Teddy Roosevelt and William Howard Taft winning more than 7.6 million votes. Meanwhile, the Socialist Party candidate Eugene V. Debs won 900,000 votes. Facing a united Republican Party, it seemed likely that Wilson might lose the election. Significantly, despite the upcoming election, no Republicans argued that the Supreme Court seat should have been left vacant until the next president took office, even though it was an election year.

Republicans did oppose Brandeis on policy grounds. He was a reformer, an activist lawyer, and a supporter of the rights of workers, immigrants, and women. He opposed monopolies and unregulated economic activity by large industries, public utilities, banks, and other financial institutions including brokerage houses. These were reasons enough for many Republicans to oppose him. While no one in the Senate explicitly raised the issue of Brandeis’s religious and ethnic background, anti-Semitism nevertheless swirled around the opposition to his nomination.

The nomination came at a high point of anti-Semitism in the United States. A year before Brandeis’s nomination the Supreme Court refused, by a 7-2 vote, to overturn the murder conviction of Leo Frank, a Jewish businessman, whose trial had taken place in a circus-like atmosphere of Ku Klux Klan inspired anti-Semitic hysteria. The unfairness of the trial, as well as Frank’s innocence, was obvious to everyone but the authorities in Georgia and a majority of the U.S. Supreme Court. Shortly after the Court rejected his appeal, a mob dragged Frank from a jail and lynched him. Georgia authorities never charged anyone with this murder.

During this period the popular media often portrayed Jews with ugly language and racist cartoons. Private clubs regularly refused to admit Jews, elite colleges and universities placed quotas on Jewish enrollment, and cultural anti-Semitism was acceptable among American elites. This elite bigotry dovetailed with the Populist Party’s anti-Semitic rhetoric. William Jennings Bryan’s Bible-thumping fundamentalist presidential campaigns in 1896, 1900, and 1908 were tinged with loathing of Jews and Catholics. At the same time a resurgent Ku Klux Klan focused much of its hated Jews and Catholics as well as blacks. In this atmosphere, President Wilson nominated Brandeis.

Brandeis’s victory in Muller v. Oregon (1908) was immediately seen as a milestone for workers’ rights and women’s rights. Indeed the feminist leaders of the National Consumers League, Florence Kelley and Josephine Goldmark, had recruited Brandeis for the case and were thrilled with the outcome. They considered it a great victory for women and workers alike. As with his other reform cases, Brandeis insisted that he receive no fee for taking the case.

His brief in Muller, which stressed social, health, and economic issues involving poor working conditions, set the stage for future progressive litigation, and was a model for briefs in subsequent labor, civil rights, and progressive cases. That style brief is still known as a “Brandeis Brief.” Significantly, in his opinion of the Court Justice David J. Brewer did something the Court almost never did: he singled out a lawyer’s brief for special praise: “It may not be amiss, in the present case, before examining the constitutional question, to notice the course of legislation, as well as expressions of opinion from other than judicial sources. In the brief filed by Mr. Louis D. Brandeis for the defendant in error is a very copious collection of all these matters, an epitome of which is found in the margin.” He then quoted and cited extensively from the Brief in a footnote.

As a public interest lawyer, Brandies had exposed dishonesty, corruption, and scandal in the Taft administration that helped lead to Taft’s defeat for reelection in 1912. Needless to say, the ex-president loathed the crusading lawyer from Boston. The title of one of Brandeis’s books, Other People’s Money and How the Bankers Use It (1914) illustrates why Wall Street despised Brandeis. While the opposition to Brandeis was ideological, economically self-serving, and political, anti-Semitism was a major tool of those trying to derail his confirmation.

One Boston stockbroker urged the Senate to defeat the nomination because Brandeis was a “slimy fellow” tainted by “his smoothness and intrigue, together with his Jewish instinct.” Such blatant racism and anti-Semitism was considered respectable by his wealthy, elite opponents. Some lawyers (many of whom had lost to Brandeis in court) asserted, without evidence, that he was unethical. At the same time, those who had faced him in Court also complained that he always aggressively represented his clients, and did not go along to get along. In other words, for some Brandeis was “unethical” precisely because he followed his ethical obligation to, in the words of the modern code of professional conduct, to be a “zealous advocate on behalf of a client.”

Abbott Lawrence Lowell, the president of Harvard, was more refined in his opposition to Brandeis, but his arguments still smacked of bigotry and anti-Semitism. Using coded language, he claimed Brandeis was “unscrupulous,” and lacked “judicial temperament and capacity,” but when asked for evidence of this, Lowell admitted he had none. Brandeis was a graduate of Lowell’s law school, and he been a popular teacher there. But this did not stop Harvard’s president from defaming him. Significantly, all but one of the faculty at Harvard Law School publicly endorsed his nomination.

Opponents argued Brandeis was money grubbing (wink, wink, Jewish) while also questioning his extensive pro bono practice. The opponents never explained how Brandeis could be motivated by money but also take so many cases for free. Typical of anti-Semitic thought, Brandeis’s critics claimed he was simultaneously both greedy and a socialist. The Massachusetts Republican, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge complained that Wilson, hoping to carry the Jewish vote in New York, Massachusetts, and elsewhere, had only nominated Brandeis because he was Jewish, implying he was not qualified. Certainly, the growing power of Jewish voters may explain why some Republican senators, including one each from New York, Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts, did not show up for the confirmation vote. As conservative Republicans they did not want to vote for “The People’s Lawyer,” but they dared not vote against the Jewish nominee.

While his opponents claimed Brandeis’s “Jewish” traits and characteristics made him unfit for the office, in the end their arguments fell short. The Senate ignored the massive racist and anti-Semitic attacks on Brandeis, ultimately confirming him by a vote of more than two to one, mostly along party lines. Forty-four Democrats and three progressive Republicans voted for confirmation, and twenty-one Republicans and one Democrat voted no. Even in the face of Ku Klux Klan inspired anti-Semitism, not a single southern Democrat voted against Brandeis, although a handful did show up for the vote.

This vote reflected the power of Wilson. In 1910 there were 60 Republicans in the Senate. In 1912 Democrats took the Senate and the White House. This was in part due to the scandals of the Taft administration that Brandeis had helped expose. In the off year election, with Wilson in office, Democrats picked up five more Senate seats. Democrats were not about to betray their president – the first of their party in two decades – who had helped them take the Senate. However, seven southern Democrats, including “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman of South Carolina, ducked the confirmation vote. They may have mistrusted Brandeis’s liberalism and were perhaps uncomfortable supporting a Jewish nominee. But all the other southerners voted for Brandeis. This vote suggests the complexity of Southern politics. The first two Jewish U.S. senators had been from the South, 3,000 Jewish soldiers served in the Confederate army, Jefferson Davis had a Jew (Judah P. Benjamin) in his Confederate cabinet nearly a half century before Teddy Roosevelt put a Jew (Oscar Strauss) in a U.S. cabinet. Brandeis, who was born and raised in Kentucky, passed muster as had many other southern Jews.

The Brandeis confirmation did not end anti-Semitism in the US, especially in corporate board rooms, private clubs, elite universities, and among right wing groups. The 1924 immigration restrictions, passed by a Republican Congress and signed by a Republican president, kept hundreds of thousands of Jews out of the country, but these restrictions also affected Italians, Poles, Greeks, Turks, and other eastern and southern Europeans, Middle Easterners, and Asians. A decade later, these quotas would of course have a profound effect on Jews trying to escape Nazism on the eve of World War II.

Despite lingering private prejudice, the Brandeis confirmation signaled the beginning of the end to the use of anti-Semitism by political leaders to block the appointment of Jews to positions of great importance in American political life. In the 1930s both a Republican (Hoover) and a Democrat (FDR) sent Jews to the Supreme Court and Jews played an increasingly active role at the highest levels of American politics. Even ex-President Taft, who had ranted that Brandeis was “a socialist,” “unscrupulous,” “cunning,” and “evil,” came to value Brandeis as a colleague when Taft became Chief Justice in 1921.

In the face of public bigotry, the Senate rejected the legitimacy of anti-Semitism when considering a Supreme Court nominee in 1916. Once on the Court, no one seemed to be concerned that he remained a leading figure in the Zionist Organization of America and the World Zionist Congress. Indeed, the new Justice’s powerful opinions and obvious wisdom made the earlier arguments about his temperament and ethnic traits seem absurd. He was often allied with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., the embodiment of America’s traditional Protestant aristocracy. Brandeis himself became one of our greatest and most influential justices. Many of his opinions – on liberty, free speech, and fundamental fairness – are now accepted and honored.

Most importantly, since the Brandeis fight, no nominees to the Court have been so vigorously (or openly) attacked on the basis of ethnicity or religion, and at the national level anti-Semitism is generally no longer part of America’s political vocabulary. Thus, for all Americans the 100th anniversary of Justice Brandeis’ confirmation to the Supreme Court is a milestone worth remembering. The confirmation is also worth celebrating as an example of Congress fairly and honestly considering a Supreme Court nominee, even in an election year.

Featured Image Credit: “The Supreme Court of the United States. Washington, D.C.” by Kjetil Ree. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Brandeis confirmation a century later appeared first on OUPblog.

10 facts about the maracas

The simple design and intuitive process of the maracas have made it a familiar favorite around the world, but may often lead to an underestimation of its value in creating variety of rhythmic expression. Yet this rattle-like instrument has a long history of engaging audiences of all ages and backgrounds. Learn more about the cultural significance and musical capabilities behind the maracas with our ten fun facts below:

1. Although maracas are traditionally made from hollowed and dried gourds, today they are more commonly found in plastic, metal, and wooden forms.

2. The term ‘maraca’ likely has origins in the pre-Columbian Araucanian language, and its heritage as a rattle is ancient.

3. Different maracas can produce sounds that are recognizably higher or lower than one another, and composers will sometimes specify depending upon the desired sound.

4. Maracas are integral to Latin American dance bands, and have become increasingly popular in pop groups, percussion ensembles, as well as primary school music education.

5. Many 20th century composers including Edgard Varèse, Sergey Prokofiev, and Malcolm Arnold included the maracas in their pieces.

6. In Paraguay, maracas are most commonly made from the porrongo gourd, and are only played by men.

7. A Brazilian instrument of similar construction, the caxixi, which is made from a small wicker basket filled with seeds, produces a similar sound to that of the maracas.

Maraquero: A boy playing maracas at the 2007 Universal Forum of Cultures. Photo by ruumo. CC by Share Alike 2.0 Generic via Wikimedia Commons.

Maraquero: A boy playing maracas at the 2007 Universal Forum of Cultures. Photo by ruumo. CC by Share Alike 2.0 Generic via Wikimedia Commons.

8. In Venezuela, the singer plays the maraca as a basic form of rhythmic accompaniment.

9. In Colombia, the maracas are an integral part of the conjunto de cumbria and conjunto de gaitas ensembles. Smaller types of rattles, like the gapachos and clavellinas, appear in the Andean and Llanos regions, respectively.

10. Maracas are usually played in pairs, with either one in each hand or two held together in one hand.

Do you have any others to add to our list?

Featured image: “Maracas” by Max Bosio, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post 10 facts about the maracas appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers