Oxford University Press's Blog, page 494

June 29, 2016

A story of how a cluttered mind can find itself in clover

Once again, no gleanings: the comments have been too few, and there have been no questions. Perhaps when the time for a real rich harvest comes, I’ll start gleaning like a house on fire. When last week I attacked the verb clutter, I planned on continuing with the kl-series; my next candidates were cloud and cloth. The nearest future will show whether I have enough material for cloud; at the moment, I can only say that the origin of cloth is a worthwhile topic. However, before I deal with cloth, it may be useful to devote a post to clover (some difficulties in the treatment of cloth and clover are similar), even though one can read a long entry on it in my etymological dictionary.

Old English had two forms of the word for “clover”: clāfre ~ clābre and clæfre (also with a long vowel; æ had the value of a in Modern Engl. man). The presence of long æ alternating with long a gave etymologists a good deal of trouble, but I will ignore this problem, for it is not the phonetic but the semantic history of clover that is at issue here: we want to know why people called the familiar plant clāfre. Some etymologists of the past believed that clāfre is a compound (clā– + –fre) and tried to find the origin of the enigmatic –fre. The great Friedrich Kluge even compared it with –fer in Engl. heifer. (I have a soft spot for heifer, for my etymological career began with this word. Its origin is still not quite clear despite many efforts to “illumine the gloom in which its history appears to be involved,” but, unlike clover, the word heifer, from Old Engl. heahfore, is almost certainly a compound.) Old Engl. clāfre should probably be divided into clāf– and –re, rather than clā– and –fre, for –re looks like the continuation of –dre, a common suffix of tree names (unfortunately for this etymology, clover is not a tree): apuldre “apple tree,” mapuldree “maple,” and so forth. Later, this –dre was associated with the word tree; hence Old Engl. æppeltre and æppeltrēow.

Even when a heifer is in clover, nothing follows from this fact for etymology.

Even when a heifer is in clover, nothing follows from this fact for etymology.We should leave Old Engl. –fre in limbo and turn to the word’s root. Engl. clover has cognates in all the West Germanic languages and nowhere else (for comparison: the Icelandic for “clover” is smári; in Gothic, this word has not been recorded). Danish and Norwegian kløver, Swedish klöver, and Russian klever are loans from Low (= northern) German. Some researchers believe that clover is a remnant of a lost language, the pre-Indo-European substrate. If this is true, there is nothing more to say. But I will assume that the Germanic origin of clover is reconstructable and will continue.

The earliest guess about the origin of clover (German Klei, Dutch klaver) took inspiration from Latin trifolium “trefoil, clover”: allegedly, since the Latin word refers to the cloven form of the leaf, the same is true of clover, which must be allied to Engl. cleave “to split” (from Old Engl. clēofan), Dutch klieven, and German klieben. If phonetic “laws” mean anything (and I believe they do), Old Engl. ā (in clāfre) and ēo (in clēofan) are incompatible, because Old Engl. ā practically always goes back to ai, but ai and ēo belong to different ablaut series, that is, they do not intersect in the forms derived from one and the same root. Some other linguists preferred to trace clover to the root of clay, because clover prefers sandy and loamy soils, or to the Indo-European root gloi– “bright, shining.” Though clover comes in several colors, none of them is particularly bright. Also, it may flourish on loamy soils, but it would be strange if this feature were chosen as the most noticeable one in the naming of the plant. (Incidentally, the idiom to be in clover is usually explained with reference to cattle’s delight in eating clover.)

A man should cleave to his wife.

A man should cleave to his wife.The etymology, half-heartedly accepted by most modern authorities, connects clover with the other cleave “to adhere.” The verb is archaic but not dead. Its Old English form was clīfan; ī, from ai, and ā do belong to the same ablaut series. It took clīfan and clēofan centuries to merge. Modern speakers are often puzzled by the opposite senses (“to split, sever” and “to stick to”) of the “same” word. But the word is not the same. Cleave1 and cleave2 are as different as sea and see and as meat and meet, except that they ended up with an identical orthographic image. It might not be too bad to “reform” them to cleeve and cleave. The question of course is what is sticky about clover.

The clover, it doth cleave.

The clover, it doth cleave.Clover evokes the idea of an adhesive mass in several languages. Icelandic smári, mentioned above, may be related to the Scandinavian word for “butter”: Swedish smör, Old Icelandic, Norwegian, and Danish smør, etc., though this etymology is debatable (of course). In Russian, a popular synonym of klever is kashka, formally, a diminutive of kasha “porridge, cereal.” With a word denoting “pap, mash, pulp” we are not too far from cleave “adhere, stick to.” German kleben, an obvious cognate of cleave, is a close synonym of schmieren “spread (butter); lubricate.”

But perhaps clover is “sticky” because its thick juice is traditionally one of the main sources of honey. The missing link between clover and stickiness is provided by the English word honeysuckle, which until the end of the seventeenth century meant “red clover.” This meaning is still alive in dialects. Honey stalk mentioned in Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus (IV: 4, 90) are stalks of clover. Not only the cattle appreciate the sweet taste of clover: wherever it grows, children chew it, as they chew honeysuckle and sometimes lilac. As recently as at the end of the nineteenth century, poor people in Iceland put clover in their milk and ate this “cold cereal.”

The etymology I have hesitatingly supported here is far from “final.” It is mentioned in some excellent dictionaries with a question mark, ignored in others, and even rejected by a few leading specialists. One observes with amusement that in German lexicography the connection between clover (Klee) and cleave (kleben) appeared only after Kluge’s death and stayed in the next eleven editions of his dictionary, until Elmar Seebold took it out. I know that I keep beating the same horse, but that is because I cannot decide whether the nag is willing or dead. All the current etymological dictionaries of English, German, Dutch, and the Scandinavian languages are “concise,” and that is their fatal flaw. For instance, Seebold did not explain why he disagreed with his predecessors, and Götze, Kluge’s faithful student and amanuensis (Kluge was blind for many years) did not explain why he had rewritten his teacher’s entry.

To sum up: there is some reason to believe that clover got its name because it was adhesive, sticky, “cleaving.” For some reason, unusually many English, Dutch, Frisian, and German words beginning with kl- have no known cognates outside West Germanic. It would be dangerous to ascribe this fact to sound symbolism (sound symbolism being such a vague concept) and equally rash to dismiss such words as traces of an unknown substrate. We will return to this precarious situation while examining the history of the noun cloth.

Image credits: (1) Cow by lisaknola, Public Domain via Pixabay (2) Clover field near Russin by Björn S… CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons (3) Naples – Old couple 1890s by Anonymous, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons (4) Cleaver by Pashminu Mansukhani, Public Domain via Pixabay

Featured image: “Clover” by Paul Horner, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A story of how a cluttered mind can find itself in clover appeared first on OUPblog.

What makes Mr. Darcy desirable?

Here’s my simple question: when did we come to believe that Darcy was sexy?

The popular image of Jane Austen’s Fitzwilliam Darcy today is Colin Firth, with his wet clinging shirt, later immortalized by a giant statue.

Photo credit: “Mr. Darcy in the lake at Lyme Park.” Copyright Philip Halling, CC BY-SA 2.0

Photo credit: “Mr. Darcy in the lake at Lyme Park.” Copyright Philip Halling, CC BY-SA 2.0In 1940 we had Laurence Olivier, with his dapper coat, gleaming eyes, and smoldering charm.

In Curtis Sittenfeld’s new novel, Eligible, Darcy is introduced as “tall, dark, and handsome.” Arrogant and irresistible, Darcy has become one of the great sex symbols of our culture.

But Austen didn’t imagine him that way. We don’t, in fact, have a very clear sense of what he looked like. He is introduced with a “fine, tall person, handsome features, noble mien,” but this sentence concludes that that his bad manners give him “a most forbidding, disagreeable countenance.” The description holds both options in suspension at opposite ends, preventing us from reaching any conclusion and thereby discouraging us from assigning the issue much importance.

Photo credit: Laurence Olivier in “Pride and Prejudice,” 1940. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo credit: Laurence Olivier in “Pride and Prejudice,” 1940. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.However, most Jane Austen heroes are not particularly attractive. At best they might be like Bingley, “good looking and gentlemanlike.” But on the other hand, they might look like Edward Ferrars, who has “no peculiar graces of person or address. He was not handsome, and his manners required intimacy to make them pleasing.” Any experienced Austen reader knows that handsome, charismatic young men are dangerous. Avoid Willoughby, Henry Crawford, Frank Churchill. Go for their boring elders: Colonel Brandon, Edmund Bertram, Mr. Knightley. Familiar men, neighbors and relations, are the ideal marital choices.

This makes sense. When a woman married in the eighteenth or nineteenth century, she consigned herself wholly into a man’s power. The moment she married, she ceased to be a legal person of her own. With no right to custody, no capacity to keep any money she earned, no legal capacity to sign her name to any contract, and no possibility of divorce, she was absolutely dependent on the man she had chosen for her entire lifetime. So a prudent woman would do some research to make sure she wasn’t entrusting herself to a scoundrel: research his history, assess his credentials.

Lizzie accomplishes these goals at Pemberley. The housekeeper informs her that ever since he was four years old, Darcy has been a kind man, a loving brother, and a benevolent employer. During Lydia’s elopement, Darcy reveals himself willing to sacrifice himself for the Bennetts. He proves himself a useful patron and a valuable ally. His strong advocacy for women and economically disempowered people makes him attractive.

Yes, Darcy is rich, but his wealth will do no good if he is a gambler like Wickham. Yes, Darcy is well-born, but his class will do no good if he uses his status to crush his wife rather than raise her. Yes, Darcy may be handsome, but his appearance may cover a vicious temper. Far more important than wealth, birth, and looks is a moral sensibility that can regulate these traits in a way that will benefit the woman who marries him.

In a rare direct address to the reader, the narrator of Pride and Prejudice congratulates Lizzie on overcoming her tendency to love at first sight. Lizzie has learned at last that “gratitude and esteem [are] good foundations of affection.” The alternative, love at first sight, is so distasteful it can hardly even be named: “what is so often described as arising on a first interview with its object, and even before two words have been exchanged.” Because Lizzie had already found its shortcomings “in her partiality for Wickham,” she finally realizes the superiority of well-founded attachments.

Our ideas of love have changed profoundly since Austen’s time. Austen depicts Lydia as a self-indulgent fool, but in a modern rom-com, Lydia would be the heroine, the girl who risks everything to follow her heart, and Lizzie would be the stuffy conventional elder sister who tries to keep her down. Today, erotic attraction has become the basis for marriage, so we designate Darcy as ultra-marriageable through a different set of markers than Austen used. Moreover, film is a visual medium, encouraging us to enjoy precisely the kind of “regard. . . arising on a first interview with its object” (particularly when that object is wearing a wet shirt). By comparison, the slow accumulation of a long history of worthy acts is the kind of history that the novel can do, and that this novel does.

In one sense, it’s fine to ogle Darcy; why shouldn’t modern viewers enjoy him in our own way? However, we should realize that seeing Darcy as desirable is anachronistic – and also completely at odds with the work of this novel. We haven’t yet had the film that shows the thousand small acts of substantive kindness that added up to a life, but it is his life, not his shirt, that makes Darcy a man one would want in 1813. And for a vulnerable woman, finding a safe match is worth acclaim, even though it is harder to erect a statue to it in the lake.

Featured image: “Pride and Prejudice” by Mike Kniec, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What makes Mr. Darcy desirable? appeared first on OUPblog.

The Brexit trade-off

Amidst the uncertainty around what will happen after Britain’s historic vote to leave the European Union, there is some clarity about the next steps. Boris Johnson, the prominent Leave campaigner and PM contender, has set out his views in a newspaper article in which he says that Britons will have the right to live and work in the EU and the “only change” after Brexit is wresting control back so that we are no longer subject to EU laws. This includes the ability to control migration.

It’s worth remembering that the European Union views the freedom of movement of people as one of the four pillars of the Single Market (the others being the free movement of capital, goods, services), which grants the right to people within it to live and work freely anywhere in the EU. In other words, as a member of the EU Single Market, Brits have the right to live and work in the EU just as those from the EU have the same rights to live and work in the UK.

Is it possible to retain access to the European market but not be subject to EU laws, including the freedom of movement of people? So far, the EU hasn’t granted that to the non-EU countries which have negotiated the right to access the Single Market.

There are 3 countries in the European Free Trade Association (Norway, Liechtenstein, Iceland) plus Switzerland which also has access to the Single Market via a series of treaties in the European Free Trade Association. All accept freedom of movement of people in exchange for their varying degrees of access to the largest economic bloc in the world. Indeed, it’s described as “perhaps the most important right for individuals, as it gives citizens of the 30 EEA countries (EU plus these 3 countries) the opportunity to live, work, establish business and study in any of these countries.”

BRexit door by mctjack. Public Domain via Flickr.

BRexit door by mctjack. Public Domain via Flickr.To give a sense as to how integral free movement of people is, Switzerland’s two year struggle to impose a quota on EU migrants is telling. In February 2014, the Swiss voted in a referendum for controls on EU migration. But, the EU wouldn’t budge on the principle of the freedom of movement of people, so the negotiations have dragged on with no conclusion. Ironically, they are exploring using the “emergency brake” that the British Prime Minister David Cameron had negotiated prior to the EU referendum in the UK that would have restricted in-work benefits for new migrants and potentially lessened the “pull factor” of economic migration to a higher income country.

Remaining in the European Single Market has also been touted by a range of businesses and policymakers, including the Mayor of London, as being crucial in Britain’s future relationship with the EU. Not all Leave campaigners may agree, of course, since some had advocated leaving the Single Market and just having a free trade agreement (FTA) with the EU.

A FTA wouldn’t confer the right to live, study, and work in the EU, so it remains to be seen whether Boris Johnson can deliver on what he wrote.

The Single Market is much more than a free trade agreement. By applying the same rules and standards on goods and services, it frees up trade and investment in ways that allows a business to treat the half a billion people in the EU as a single market for their business. So, it’s not about tariffs but what economists call non-tariff barriers that matter, in some instances more, especially for small businesses where the ease of selling across borders can be heavily affected by standards and rules.

And, for businesses, small and large, the European market is important.

The Institute of Directors surveyed its members after Brexit. Of the 1,092 UK firms, a quarter were freezing reruitment, some 20% were considering moving their operations abroad, and 5% even said redundancies were possible.

This reaction reflects the uncertainty that has been seen most vividly in markets, but also importantly for the economy, the big question marks over the UK’s future relationship with Europe.

It may well be that the cost of gaining access to the Single Market is too great if it means accepting the free movement of people. Of course, it’s not just immigration policy. Like the other non-EU countries that access the Single Market, the UK will also have to accept the rules set by Brussels. And that may well be unacceptable since Boris Johnson had stressed that the only change was that Britain won’t be governed by EU laws.

But, that is the unavoidable trade-off: access to the EU Single Market versus control over migration.

Now, if the UK were to gain some, but not full, access to the Single Market, would the EU be willing to permit the UK to retain control over migration and compromise one of its fundamental principles? And what would that look like? Would other EU countries want the same deal or threaten to leave?

The EU hasn’t so far granted any such “Single Market-lite”, but there are those who have argued that Britain is a more important economy than Switzerland or Norway, etc., so the EU will want to sell to the UK and offer more concessions.

On the other side, there are others who insist that granting Britain the benefits of the Single Market without the free movement of people is setting the wrong example for other EU countries who also want to control migration and may leave too. A breakup of the EU is an outcome the EU leaders certainly want to avoid.

We will eventually find out who’s right, but there is no doubt that this is a challenging trade-off with a lot at stake for the economy.

Featured image credit: European Union by Yukiko Matsuoka. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The Brexit trade-off appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know Bertrand Russell? [quiz]

This June, the OUP Philosophy team honors Bertrand Russell (May 18, 1872 – February 2, 1970) as their Philosopher of the Month. Considered among the most distinguished philosophers of the 20th century, Russell’s style, wit, and contributions to a wide range of philosophical fields made him an influential figure in both academic and popular philosophy.

But how much do you know about this renown thinker? Test your knowledge of Russell with the quiz below.

Quiz image credit: drawing of Bertrand Russell by James Francis Horrabin (1884-1962). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: photo of Colwyn Bay, Wales by Ken Tholke. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How well do you know Bertrand Russell? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Research skills, transferable skills, and the new academic imperative

The challenges afflicting higher education in the US are many and multifaceted, and much has been written about the transformation (or full-blown identity crisis, if you’re being less charitable) of the academic institution and its place in society. Much of the controversy has to do with the institution’s responsibilities toward its students, its employees, and the community, with some claiming that “knowledge for knowledge’s sake” is no longer a sufficient offering in a world of rising tuition fees and a brutally competitive job market even for highly educated graduates. When it comes to the structures and expected outcomes associated with undergraduate, masters, and PhD programs, a common complaint is that the institution does too little to prepare students for careers in or outside academia.

Most universities have two key “outputs” intended for the betterment of society: graduates (the people they educate) and research (the publications and discoveries produced by their students and faculty), which together make up their total contribution to human knowledge. However, the whole system is challenged by the fact that recent graduates are increasingly unable to find good jobs, and research outputs are under new scrutiny over proper conduct and systemic failures to address this problem. Clearly the status quo cannot stand, and while this is no small challenge, some thought leaders believe that by solving the “research problem” we can successfully tackle the employability issue at the same time.

This bold approach suggests a few immediate questions. How and when should students learn to conduct research effectively and responsibly? How can these skills be taught in such a way that the experiences translate to career paths outside academia? And whose job is it, exactly, to figure this all out and deliver sustainable solutions?

The countless stakeholders frustrated by the unfulfilled promise of an expensive undergraduate degree leading to solid employment options, or a hard-won PhD leading to a fulfilling academic career, may find hope in the numerous movements in support of re-thinking the university experience in general and the research experience in particular. Organizations like the Council on Undergraduate Research and the Association of American Colleges and Universities are encouraging us to think of research much more broadly as an opportunity for students and the communities they serve—not as a self-contained activity played out in the lab or in the library stacks, but rather as a set of skills and experiences that find equal relevance in both academic and corporate careers.

Insufficient or nonexistent training can lead to mistakes ranging from the mildly embarrassing to the catastrophic

The possession of research skills, after all, is a professional qualification in itself, and top employers are increasingly seeking out candidates who have more than just a degree and knowledge of a subject, however advanced that knowledge may be. Now and in the future, the most in-demand jobseekers will be those who bring a strong set of analytical and problem-solving skills—in addition to professional skills such as communication, collaboration, and leadership—that they have already mastered before graduating from college. Advocates of the undergraduate research movement are confident that a new focus on transferable skills and “professionalization” of research is the key to empowering students and helping institutions to enhance their reputations by providing impactful training support in these areas.

Powerful training programs can help even experienced researchers to produce better results and excel in their careers. The issue of pervasive laxity in research and reproducibility has prompted institutions to give another look at the quality of the training they offer to students and faculty, lest one of their own publishes a paper that attracts media attention for all the wrong reasons. No matter how long a researcher has been working in a given field, there are always opportunities to hone the skills necessary for planning, executing, and publishing better results that contribute positively to the body of knowledge and to the researcher’s own career advancement.

And those who choose to pursue a career in “pure” experimental research, whether in academia or industry, are by no means off the hook when it comes to the professional competencies discussed above. The perils of hiring good scientists who are poor communicators and lack basic managerial skills are well understood by anyone who has worked in a research setting, as is the reality that these skill gaps in leadership positions seriously perpetuate the cycle of poor training of junior researchers, who too often rely on informal (and sometimes inaccurate) knowledge transfer from their peers. It must be the responsibility of higher education to address student training needs as early as possible, as otherwise the institution will not realize the full potential of its talent pool and may in fact be wasting vast resources on research that is improperly conducted.

Delivering on this imperative is as challenging as it is critical, but institutions are not facing the task alone; federally funded grants, professional organizations, and corporate and nonprofit partners are equally invested in the outcomes of improved access to training and development for researchers across the career arc, from the eager but inexperienced undergraduate to the overworked senior research administrator.

Simply put, better training leads to better career options for researchers, better research output for institutions, and better talent for academic and non-academic employers. Insufficient or nonexistent training can lead to mistakes ranging from the mildly embarrassing to the catastrophic; and while self-preservation through preemptive damage control may be the most basic (and most cynical) motivation to invest in training, the true opportunity is to rise to the calling to prepare new generations of researchers to tackle the biggest challenges of our time.

Featured image credit: Key on keyboard. By JeongGuHyeok. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Research skills, transferable skills, and the new academic imperative appeared first on OUPblog.

June 28, 2016

Benjamin Franklin Says “WE ARE ONE”

A year before signing the Declaration of Independence, Benjamin Franklin wrote to Jonathan Shipley, one of his closest English friends, about American congressional affairs. He told of his day-long meetings (he worked from 9 AM often until 9 PM) in Congress. Despite his physical exhaustion, Franklin was impressed with his colleagues. Members of Congress, he wrote, attend “closely” to congressional affairs, “without being bribed to it, by either Salary, Place or Pension, or the hopes of any.” Such was the case with “a new virtuous People, who have publick Spirit,” he said, contrasting it with the “old corrupt” Parliamentary system in England, where leaders “have not so much as an Idea that such a thing” as virtue “exists in Nature.”

The public spiritedness of the new American Congress was widely admired in 1775. It was a heady time, as members of Congress forged from their political ideals a working blueprint for constructing an army (which Franklin hoped would reach “above 20,000 Men”), developing an intercolonial empire of goods in the absence of Britain’s trade restrictions, and determining a common means to fund intercolonial trade and thus support a war effort against Britain. For over a decade, colonial Americans had been working to consolidate political activity by refusing to purchase the goods that Britain chose to vend in North America. The colonists’ non-importation agreements extended across the colonies; instead of buying goods manufactured in Britain, colonial consumers were bartering for and buying products and manufactured goods from other colonies. Austerity, a keyword of the non-importation movement, brought internal prosperity.

Congressional resolutions and petitions increased from 1775 into 1776, and Americans prepared for war. The colonists could no longer be forced to import British “superfluities” (Franklin’s word for British goods), but they would need to develop a currency system printed and monetized by the colonies alone. Given his skill—he had studied economic systems in the Atlantic world and was the first to devise a system of colonial paper bills that were difficult to counterfeit—Franklin was appointed to design, secure copper plates for engraving, and oversee the printing of Continental paper currency.

Franklin was busy! He established a wartime postal service, worked on manufacturing saltpeter (used for gunpowder), wrote an olive branch (peace) petition to King George III, and served as President (essentially, governor) of Pennsylvania. Even so, Franklin developed ten designs for paper currency bills. In creating these designs, Franklin revisited two favorite pastimes from earlier in his life: printing leaf designs (which made counterfeiting difficult) and reading through emblem books to find adaptable designs.

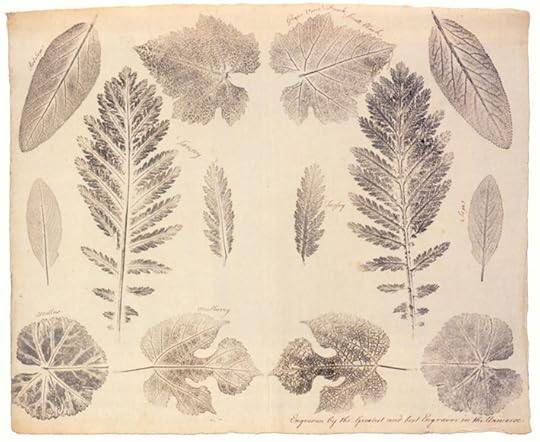

In his early printing days, Franklin had worked on finding new ways to print original images on paper, because he wanted to secure a contract to print paper currency in Pennsylvania. A key concern about moving away from hard money like gold and silver to printed paper currency was the ease of counterfeiting paper money. He experimented with different printing techniques and then worked with his Junto friend, Joseph Brientnal, on printing tree and plant leaves, because these would be difficult to imitate. (For more about Franklin’s printing, including his leaf printings, see the online exhibition about Franklin at the Library Company of Philadelphia.)

Joseph Breintnal and Benjamin Franklin, Nature Prints of Leaves, Philadelphia ca. 1740. Credit: The Library Congress of Philadelphia, used with permission.

Joseph Breintnal and Benjamin Franklin, Nature Prints of Leaves, Philadelphia ca. 1740. Credit: The Library Congress of Philadelphia, used with permission.In 1776, as he worked on designs for new paper bills for intercolonial use, Franklin fell back on his old leaf printing designs and used them on paper bills.

Credit: Private collection, used with permission.

Credit: Private collection, used with permission.

Credit: Private collection, used with permission.

Credit: Private collection, used with permission.Franklin also recuperated his lifelong interest in creating symbolic designs that would have meaning as they were being exchanged. He used his favorite emblem book, Joachim Camerarius’s Symbolorum ac Emblematus Ethico-Politicorum (Latin for “Ethical and Political Symbols and Emblems”). Camerarius’s book was popular and was reprinted often. Franklin’s own copy of the book was a German publication from Mainz, dated 1702; it is housed at the Library Company of Philadelphia, the library Franklin began.

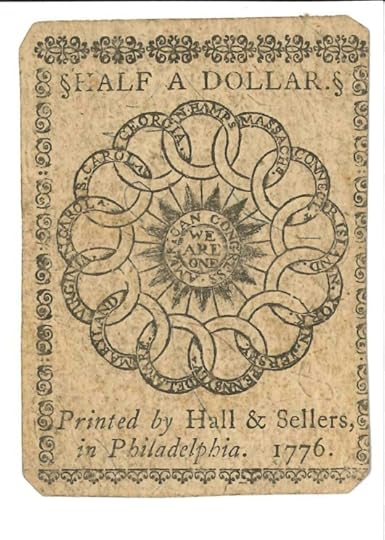

One of the reasons British leaders thought the American colonies would never rebel was that the colonies were too diversely settled, and they produced different products and thus operated on different economies. But the era of non-importation had taught the American people that they could be self-sustaining if they worked cooperatively. This is the meaning behind Franklin’s expression on the Continental currency, “WE ARE ONE.” Surrounding the “WE ARE ONE” expression on the Continental bills is another image Franklin devised, based on classic sources: interlocked circles forming a circle. The image allows to each colony its own identity (each circle is marked with a different colony’s name) while creating a visual impression of unification, indicating that “we are one.”

Credit: Private collection, used with permission.

Credit: Private collection, used with permission.These interlocked circles were used on different issues of continental bills across 1776, on a New Hampshire regimental flag in 1777, on a Massachusetts company flag, and eventually on a set of china that Robert Morris asked Josiah Wedgwood to create for him when he served as the U.S. Agent of the Marine.

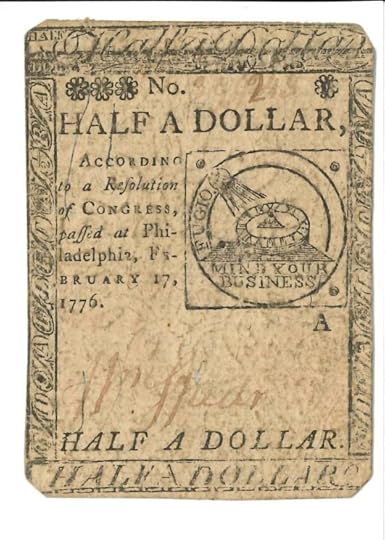

Franklin also devised a “Fugio” image, which on many bills formed the reverse of the interlocked circles side.

Credit: Private collection, used with permission.

Credit: Private collection, used with permission.This image featured a design of the sun shining down on a sundial (a measure for time). On the connecting lines is written “Fugio,” meaning “I flee” or “I fly,” thus reminding viewers that time flies. Franklin added the motto, in case the point would be missed, “MIND YOUR BUSINESS,” implying that no American should misuse time nor do anything inessential to the task of securing American economic freedom from Britain. This Fugio design with the interlocked circles on reverse appeared in a number of issues of paper currency in 1776. The Fugio cent, a hard currency, was later authorized by Congress (in 1787) as the first official copper penny of the new government.

“Fuego Cent” By The U.S. Government, coins.nd.edu. Public Domain via Wikipedia Commons.

“Fuego Cent” By The U.S. Government, coins.nd.edu. Public Domain via Wikipedia Commons. “Fuego cent reverse” By The U.S. Government, coins.nd.edu. Public Domain via Wikipedia Commons.

“Fuego cent reverse” By The U.S. Government, coins.nd.edu. Public Domain via Wikipedia Commons.

Benjamin Franklin understood the essential necessity of funding the war effort, and he threw himself fully into the work to secure the united colonies’ Continental currency and to secure Americans’ financial and political independence. Americans today celebrate July 4 as a national holiday, one that determined the destiny of the country. The truth is, however, that September 3 is the more important anniversary to celebrate: on this day, the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, making possible an American nation-state and enabling the drafting of one of the most important Constitutions ever known in the West.

Featured Image: “Inscription: Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), Penn Libraries.”Image by POP via CC Flickr.

The post Benjamin Franklin Says “WE ARE ONE” appeared first on OUPblog.

10 things you didn’t know about sharks

There are more than 400 known species of sharks inhabiting our planet’s marine ecosystems but detailed knowledge about most sharks is considerably lacking. Biologists often encounter barriers to studying sharks in captivity and in the wild due to factors such as their large size, relatively low demand in commercial markets, fast speeds, and wide habitat ranges. Because of this lack of general knowledge about these animals, misunderstandings arise and sensationalized stories are created out of fear. Admittedly, large fish with big, pointy teeth capable of swimming quickly can be intimidating but not all sharks fall into this narrow stereotype. To get in the Shark Week spirit this year, we’ve compiled ten surprising facts about these ancient and diverse creatures.

The most primitive living shark is the frilled shark, named for its large frill-like gill slits encircling its head. This rare shark usually inhabits deep, cold waters and is shaped much like an eel.

Where did the name “dogfish” come from? In the past, it was thought to originate from a time when the prefix “dog” was used to denote plants or animals unfit for human consumption. However, it turns out that the prefix was generally only used for inedible plants. These sharks were named simply because their actions mirrored that of dogs: they bite.

Lanternsharks usually have bioluminescent skin organs called “photophores” on their sides or undersides that allow them to “light up like lanterns.” This bioluminescence allows the sharks to blend in with the light coming from the surface of the ocean (a process known as “counterillumination”) and makes it difficult for predators below to spot them when looking up.

The whale shark is the only species in the family Rhincodontidae and is the largest fish in the world, measuring about 5-10 meters. But fear not: these sharks are gentle giants and are only known to consume various plankton species, small fish, and crustaceans.

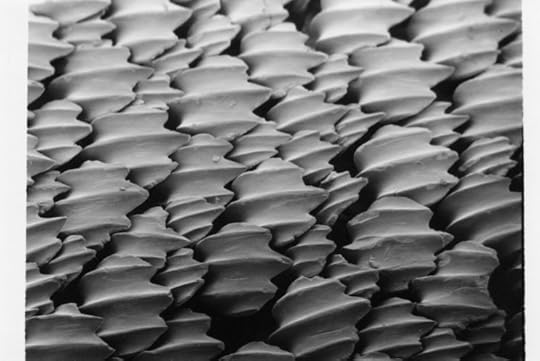

Dermal denticles of a lemon shark viewed through a scanning electron microscope. Image by Pascal Deynat/Odontobase. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Dermal denticles of a lemon shark viewed through a scanning electron microscope. Image by Pascal Deynat/Odontobase. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Sharks are largely known for the frightening-looking teeth in their mouths, but their entire bodies are actually covered in tiny dermal denticles: tooth-like scales that vary widely in shape between shark species. You definitely would not want to rub a shark the wrong way…

Averaging 20-30 miles per hour (32-48 kilometers per hour), the shortfin mako is recognized as the fastest shark species. Its fast speed makes it an excellent apex predator capable of feeding on other quick-moving species such as sharks, swordfish, and bluefish.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, the slowest moving shark species is the Greenland shark. Most individuals inspected in this species are also thought to be blind due to common eye infections caused by parasitic copepods. However, these seemingly sluggish and nearly blind sharks have been noted (through stomach content evaluation) to prey on fast-moving and agile seals and squid. While it has been suggested that the Greenland sharks wait undetected before ambushing unsuspecting prey, their ability to capture such fast-moving species still remains quite a mystery.

Sharks have a sixth sense: electroreception. Minute gel-filled electroreceptor organs called “ampullae of Lorenzini” cover the head of sharks, particularly in the snout area. These organs enable the sharks to detect weak electric fields at short ranges, allowing them to detect animals – predator or prey – in the dark or hidden out of view.

Some sharks take sibling competition to a whole new level in a process known as “oophagy”. Species that are oophagous are born live instead of in egg cases and are characterized by large embryos that feed directly on eggs in the uterus. In the early stages, these embryos have small yolk sacs that are quickly consumed. The embryos then develop a “precocious dentition” that allow it to feed on other ovulated eggs in the mother’s uterus.

Lastly, the great white shark. Although most people think of these sharks as voracious predators, some larger individuals can actually be scavengers. In an effort to save energy, it has been suggested that great whites will occasionally opt to feed passively on large whale carcasses than engage in active predation.

Featured image credit: A whale shark in the Georgia Aquarium by Zac Wolf. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 10 things you didn’t know about sharks appeared first on OUPblog.

How the Brexit vision of UK freedom risks turning sour

“All changed, changed utterly,” wrote the celebrated Irish poet W.B. Yeats of the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin, adding “a terrible beauty is born!” A century later, he might well have been writing about the result of Britain’s referendum on EU membership.

Radical change has been the dream of the UK’s triumphant Brexiteers, but what, beautiful or not, will be born? An absence of clarity about the impact of Brexit on the UK, the rest of Europe, and worldwide will last for a decade at least. The notion that Britain can neatly cut the links binding it to continental Europe will quickly prove absurd, as will the idea that the surgery will be painless and only local.

To return to that ‘terrible beauty’; the referendum result suggests that a 52% majority of British voters believe they have freed themselves of the cumbersome diktats of the EU ‘superstate’, and that the UK will be able to rediscover its former glory. They see the British lion again standing rampant at the centre of an international trading system wider than Europe, with the strength to impose some benign new form of Pax Britannica whenever troubles threaten.

The picture is beguiling but misleading. It is impossible to predict how the 27 remaining EU member states will react, but right now it seems likely that this week’s scheduled meeting of the European Council grouping national leaders will be a subdued affair.

Once the dampening effects of shock wear off, though, the pain will come flooding in. This summer will see the beginning of a tumultuous political crisis that will probably set many EU member states against one another, and will certainly reverberate around the world.

It is too soon even to guess at the immediate consequences of the vote for Brexit. The pound sterling will tumble, stocks and shares will slide and the global financial system will be severely shaken. But what goes down can also come back up, so the more important question is the longer term political outlook for the EU and for the 60-year process of European integration.

Will Britain’s exit trigger a wave of copycat pressures across the Union, as many fear? The European Union’s global credibility is going to suffer, and the further risk is that voters in other European countries will demand special treatment that could, unless satisfied, prompt fresh demands to leave the EU.

The arguments raging so fiercely in recent months inside the UK have been followed closely elsewhere, not least by Europe’s eurosceptic populists. The established centre-right and centre-left mainstream parties that in effect govern the EU’s choices and direction know that their reactions to the Brexit decision must avoid strengthening their hand.

That leaves the EU and its member governments with a difficult balancing act. They must avoid panicking and permitting the UK’s withdrawal negotiations to exacerbate euroscepticism elsewhere. And they must at the same time create a more positive climate so as to move the European project forward.

A first step would be to stop pretending that the EU’s lack of accountability is no problem. Eurosceptics are not the only ones to question the secrecy surrounding Council of Ministers’ meetings that produce no public record of who said what, along with the unelected character of the European Commission.

No one can predict the sort of more open, democratic, and transparent EU decision-making structure that might emerge from a re-think. The EU and the national leaders who in truth are responsible for its policies would, however, be very unwise to ignore the pressures for reform. Not the sort of narrow, self-serving ‘reforms’ that Britain’s prime minister David Cameron attempted to secure earlier this year, but imaginative improvements that could restore the EU’s credibility and popularity.

Featured image credit: Brexit by Sam. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post How the Brexit vision of UK freedom risks turning sour appeared first on OUPblog.

June 27, 2016

Books are for everyone at this outdoor reading room

The first thing you need to know about the Bryant Park Reading Room is that it isn’t a room. Located behind the New York Public Library in Manhattan, this open-air Reading Room sits under a leafy canopy of plane trees at the 42nd Street entrance to Bryant Park. Green metal carts hold books and periodicals for children and adults, and anyone may sit and read—no library card needed!

“‘I’m in a muddle about a lot of things—I’ve just discovered that I’ve a mind, and I’m starting to read.’

‘Read what?’

‘Everything. I have to pick and choose, of course, but mostly things that make me think.’”

– F. Scott Fitzgerald, This Side of Paradise

First established in August 1935, the Reading Room was a public response to the high unemployment rates brought on by the Great Depression. The reading room (really a row of park benches and some carts full of books, staffed by five librarians employed by the Works Progress Administration) served as a place where unemployed businessmen and intellectuals were welcome during the day, with no need for money, a home address, a library card, or any identification at all. Anyone could visit the Reading Room to enjoy the reading materials, and by its second summer it had attracted 64,624 patrons. The first iteration of the Reading Room was open every summer until 1944, when the program was stopped because many of the unemployed patrons had joined the war effort and re-entered the work force.

The Reading Room reopened in 2003 with expanded offerings including children’s books and literary programming, notably the “Word for Word” Book Club series, which Oxford University Press has been helping to organize since 2008.

“Book! You lie there; the fact is, you books must know your places. You’ll do to give us the bare words and facts, but we come in to supply the thoughts.”

– Herman Melville, Moby Dick

Reading Moby Dick in the park.

Reading Moby Dick in the park.

At each Book Club, an acclaimed contemporary author leads a discussion on a book in the Oxford World’s Classics series that has a connection to the author’s own work. This year, for example, the following events are happening every second Tuesday from now until August (Oh, “that it would always be summer . . . !” —Tess of the D’Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy):

Tuesday, June 28, 2016, 12:30 p.m.

Moby Dick by Herman Melville

Facilitated by Journalist, Magazine Editor Mark Beauregard, The Whale: A Love Story

Novel on the role Nathaniel Hawthorne played – both on and off paper – in influencing Melville’s Moby Dick.

Tuesday, July 12, 2016, 12:30 p.m.

This Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Facilitated by Award Winning Journalist, Reporter, Cultural Historian Lesley Blume, Everybody Behaves Badly: The True Story Behind Hemingway’s Masterpiece The Sun Also Rises

A look behind the personalities of those who helped inspire the classic that changed the literary world forever.

Tuesday, July 26 , 2016, 12:30 p.m.

About Love and Other Stories by Anton Chekhov

Facilitated by Fiction Editor, The New Yorker Deborah Treisman

A discussion on the craft of short stories and the influence Chekhov has had over the art of story-writing.

Tuesday, August 9, 2016, 12:30 p.m.

Tess of the D’Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy

Facilitated by Award-Winning Poet Judith Baumel, The Kangaroo Girl

Author’s third book of poetry.

Tuesday, August 23, 2016, 12:30 p.m.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare

Facilitated by Journalist, Correspondent, Photographer Jillian Keenan, Sex With Shakespeare: Here’s Much to do With Pain but More With Love (A Memoir)

An author’s personally-felt connection to Shakespeare, love, and obsession.

Whether you can make it to some of these Book Clubs in person or not, keep an eye on the OUP blog for photos, videos, and excerpts from the classics featured in the series. If you’ve ever felt, like Anton Chekhov, that “All of life and human relations have become so incomprehensively complex that, when you think about it, it becomes terrifying and your heart stands still,” the great works of literature featured in the series just might have some answers for you.

Images are all by Lucie Taylor and Emily Tobin and used with permission.

The post Books are for everyone at this outdoor reading room appeared first on OUPblog.

Do lifestyle factors have an impact on sperm morphology?

The assessment of sperm morphology, determined by the cells’ shape and size, is an important part of male fertility testing. Previous research has suggested that only sperm with good sperm morphology are able to make their way to the egg in the woman’s body and fertilise it. Our knowledge of factors that influence sperm size and shape is very limited, yet faced with a diagnosis of poor sperm morphology, many men are concerned to try and identify any factors in their lifestyle that could be causing this. To investigate the effects of lifestyle factors on sperm morphology, a team of UK scientists based at the University of Sheffield (Professor Harry Moore and myself), the University of Manchester (Dr Andrew Povey and Professor Roseanne McNamee), and the University of Alberta (Professor Nicola Cherry), conducted this landmark research.

In a break from previous investigations into sperm morphology, this research was a substantial case-referent study with 318 cases and 1,652 referent controls. Cases had poor sperm morphology (

So what did this study determine? Do factors such as body mass index (BMI), type of underwear, smoking, or the use of cannabis have an impact on the size and shape of a man’s sperm? Previous studies claimed that environmental factors may contribute to declining sperm quality. Contrary to these findings, our research demonstrated that lifestyle makes little contribution to the risk factors for poor sperm morphology. No significant association was found with BMI, underwear type, smoking, or alcohol consumption—suggesting that an individual’s lifestyle has very little impact on sperm morphology.

Of the risk factor variables for poor sperm morphology, only two proved noteworthy: the use of cannabis in young men in the three months before sample production, and sample production in the summer. Men who produced ejaculates with less than four percent normal sperm were nearly twice as likely to have produced a sample in the summer months (June to August), or be under 30 years old and used cannabis in the three month period prior to ejaculation.

The results overturned the findings of previous less well-controlled and underpowered studies, which suggested that eating, smoking, and drinking habits might contribute to poor sperm qualities in young men. While it is recommended that cannabis users stop using the drug if they are planning to start a family, overall it is reassuring to find that there are very few identifiable risks.

Since many couples undergoing assisted conception treatments such as IVF attempt to make lifestyle adjustments in order to maximise their chances of success, our data suggests there is little evidence to suggest that these will be able to improve sperm morphology. Our previous study, published in 2012 reached a similar conclusion about the number of motile sperm. Both these papers together suggest that modifiable lifestyle risks for semen quality are relatively few and far between.

With no clear link between lifestyle factors and sperm morphology, which factors affect the size and shape of sperm? A major contribution to good sperm morphology will inevitably be down to genetic factors. Moreover, infertility in men is now compounded by age-related changes in both partners. Participant recruitment began over 15 years ago, when lifestyle was much different from today, particularly with regards to mobile phone use. There are still unanswered questions in this area of research and we would like to repeat the study, to see if life in the mid-2010s has any more pronounced effects on sperm morphology than it did 25 years ago.

Featured image: Cigarette by realworkhard. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Do lifestyle factors have an impact on sperm morphology? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers