Oxford University Press's Blog, page 477

August 13, 2016

The life and work of H.G. Wells: a timeline

The thirteenth of August marks the 150th birth and the 70th death anniversary of legendary science fiction writer H.G. Wells. A prophet of modern progress, he accurately predicted several historical milestones, from the World War II, nuclear weapons, to Wikipedia. His humble origins gave him insight into class issues, and his studies in biology propelled him to become one of the greatest thinkers and observers of his time. Combined with a flair for story-telling, Herbert George Wells dominated and defines the science fiction genre till this day. His 1895 published novel, The Time Machine, propelled him to fame and inspired studies and speculation from later generations of physicists and theorists.

Also known as ‘the Father of Science Fiction,’ H. G. Wells was overwhelmingly prolific. Over the course of his life, Wells produced over a hundred pieces of work, ranging from ‘scientific romances,’ as they were called in the day, to non-fiction essays on politics, cultural commentaries, and world history. These creations led to his four nominations for the Nobel Prize in Literature. His personal life was equally eventful. A free-thinker and modernist, Wells engaged in numerous affairs with prominent feminists, writers, and activists throughout his life, most notably with Moura Budberg, who by many accounts was said to have been a Ukrainian spy.

A blend of creative voice and unbounded imagination gave him the perfect recipe for literary success. Wells understood the skepticism of his readers, and respected their intellectual hesitance to embrace the extraordinary, which led to his forming ‘Wells’ Law:’ that “a science fiction story should contain only a single extraordinary assumption.” Indeed, this law has worked so well, this gift for building credibility in realism and then engaging audience with original fantasies inspired multiple later authors, from Arthur C. Clarke, Ray Bradbury, Isaac Asimov, to Ursula K. Le Guin.

“If the world does not please you, you can change it.” The History of Mr. Polly, H.G. Wells

Wells was also an active member in politics, having run for Parliament as a Labor Party candidate for two years. He had a vision for the world, and he wanted to actively change it, although both his election runs ended in failure. Nevertheless, through his science fiction and insightful essays, H.G. Wells has managed to change the landscape of imagination and of science. His influence is palpable even in the present day. In memory of this anniversary, we have made a list of major events and predictions made in the life of H. G. Wells in the interactive timeline below.

Featured image credit: Depiction of a futuristic city, Jonas de Ro. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The life and work of H.G. Wells: a timeline appeared first on OUPblog.

Setting Shakespeare to music

Shakespeare has inspired countless and varied performances, works of art, and pieces of writing. He has also inspired music. In this 400th year since Shakespeare’s death we asked five composers “How did you approach setting the Shakespeare text you chose for your recent work?”.

Alan Bullard

Photo courtesy of Alan Bullard. Used with permission.

Photo courtesy of Alan Bullard. Used with permission.Setting Shakespeare is a daunting prospect — one is following in the steps of so many others — and it is difficult to approach ‘Hark, Hark, the Lark’ from Cymbeline without Schubert’s setting (with its extra, non-Shakespearian verses) in one’s mind. So, in my upper voice setting, I deliberately chose to respond differently — the short poem allows for a spacious, expressive approach, with the words of the title repeated several times as a refrain, the piano suggesting the rising and falling of the lark’s song, and the whole forming one broad sweep of music, shaped towards a climax and subsequently winding down.

By contrast, in my mixed choir setting of ‘When that I was and a little tiny boy’ from Twelfth Night I planned to mirror the five verses of this bitter-sweet account of the stages of life (a tragi-comic ‘All the world’s a stage’) with a folk-song like strophic melody which never quite settled in either major or minor key, or into a perfectly steady metre. I hope that this approach captured the humour, the pathos, and the final note of optimism, in the jester Feste’s valediction.

Gabriel Jackson

Gabriel Jackson. Photo by Joel Garthwaite, used with permission.

Gabriel Jackson. Photo by Joel Garthwaite, used with permission.There were always going to be Three Shakespeare Songs, after Vaughan Williams. Three is a good number for Shakespeare songs. With three pieces, there can be a nice balance between contrast and continuity. Fast-slow-fast? Or perhaps slow-fast-slow? The texts themselves can dictate that. And that was the difficult part – choosing the texts, where with Shakespeare there is so much to choose from. Perhaps texts that have been set before should be avoided? But if all three are unfamiliar, perhaps they will be less attractive to performers? In the end, I settled for one very well-known text, and two relatively unfamiliar ones. What should they be about? How to ensure there is some connection between the three pieces, some reason why they are grouped together? At one stage I thought they should all be about music, but Shakespeare’s attitude to music is always more-or-less the same – it’s a good thing! In the end, I chose three nicely different texts (two speeches and a sonnet) that all mention music or singing. The commissioners wanted there to be no divisi in these pieces, just straight SATB; my natural instinct, when setting words as rich as these, is to create rich textures and big chords. So I had to try something different to make music for these wonderful words, and different is always good!

Cecilia McDowall

1. Give me some music

2. Mark how one string sweet husband to another

3. How sour sweet music is

Where better to start writing a new choral cycle than with texts drawn from Shakespeare. A composer’s task is always easier with good words, rich in imagery, and Shakespeare has given such inspiration over 400 years to countless artists. The quest for words, just the very right words, can be a long, tricky but interesting pursuit. These particular texts are a ‘mash up’ from six different sources, including Sonnet VIII (advocating the virtues of marriage) and ‘Much ado about nothing’ (insinuating that matrimony begins well, then it’s downhill all the way). The texts are unified by a musical theme; harmony, discord and rhythm. I looked for words which I hoped had not been previously set.

Photo courtesy of Cecilia McDowall. Used with permission.

Photo courtesy of Cecilia McDowall. Used with permission.As to how to set them, the words provide a ‘way in,’ suggesting the style, mood and direction of how the music could be. Beatrice’s description of the courtship procedure as being like a Scotch jig, all hot and hasty, is enough encouragement to think of Scottish fiddle music. And why not take it a step further and give the voices ‘mouth music’ to sing, a traditional Scottish style known as ‘puirt à beul’ (literally, ‘tunes from a mouth,’ usually something cheery). Then in the second movement, with the words, one pleasing note do sing, I’ve made the repeated ‘pleasing note’ a ‘blue’ note which I hope draws attention to itself. The final movement opens with a cynical unison laugh and the order to ‘keep time’ which should sound as though it is breathlessly not keeping time. All manner of discord follows rounding off the work with a collective pitch-less sigh. The rest is silence.

David Bednall

The toughest challenge in setting a Shakespeare text is probably the familiarity of the words in question and the certain baggage that they may carry – this was certainly the case for Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? It is possibly the most loved of all the sonnets, and certainly familiar from many marriage services, yet, nevertheless, remains timeless and fresh on each hearing. Added to this of course is the feeling of responsibility involved in setting words of such quality.

In making a musical setting of a text, one inevitably has to make choices of interpretation, and once these are made the feel of the work is set; obviously a performer has a certain leeway in their interpretation, but whereas the poem may be spoken or read in many different ways depending on the moment, orator, or reader, the musical setting is a more fixed entity. A further difficulty arises purely from the fact that this sonnet is in the first person whereas my setting is for choir. Against these difficulties of course there is the advantages bestowed by a text of immense poetic beauty and natural musical flow, filled with images that lend themselves to setting.

Howard Skempton. Photo by Katie Vandyck, used with permission.

Howard Skempton. Photo by Katie Vandyck, used with permission.My approach on the whole was simple and direct, allowing the words their full expression. I began, as always, by writing out the text in full, and then planning the musical structure, always governed by the words on both micro and macro levels, and deciding on the various musical textures which would provide variety and where these might be best deployed. A musical setting is almost inevitably more extended than a purely spoken one, so I chose moments which seemed to warrant and bear repetition in a sung context. I have always been much-inspired by the word-setting of Finzi, and strove to achieve a natural flow, hopefully painting something of their meaning in the music.

Howard Skempton

One of the most enjoyable aspects of composing vocal or choral music is going in search of a text, a task normally undertaken as one is finishing a previous piece. It is also exciting to be invited to set a text chosen by a commissioner (or editor of an anthology!), and the choice in this case was inspiring. My initial aim in setting ʻCome away, come away deathʼ was to devise a strong melodic line, one that might be worthy of inclusion in a production of Twelfth Night. The writing throughout the setting is essentially homophonic. The harmony attempts to strike a balance between tenderness and gravity, and is sometimes quite stark, as when colouring “my black coffin”.

Featured image credit: Ensemble by yunje5054. CCO public domain via Pixabay.

The post Setting Shakespeare to music appeared first on OUPblog.

How did you approach setting the Shakespeare text you chose for your recent work?

Shakespeare has inspired countless and varied performances, works of art, and pieces of writing. He has also inspired music. In this 400th year since Shakespeare’s death we asked five composers “how did you approach setting the Shakespeare text you chose for your recent work?”.

Alan Bullard

Photo courtesy of Alan Bullard. Used with permission.

Photo courtesy of Alan Bullard. Used with permission.Setting Shakespeare is a daunting prospect — one is following in the steps of so many others — and it is difficult to approach ‘Hark, Hark, the Lark’ from Cymbeline without Schubert’s setting (with its extra, non-Shakespearian verses) in one’s mind. So, in my upper voice setting, I deliberately chose to respond differently — the short poem allows for a spacious, expressive approach, with the words of the title repeated several times as a refrain, the piano suggesting the rising and falling of the lark’s song, and the whole forming one broad sweep of music, shaped towards a climax and subsequently winding down.

By contrast, in my mixed choir setting of ‘When that I was and a little tiny boy’ from Twelfth Night I planned to mirror the five verses of this bitter-sweet account of the stages of life (a tragi-comic ‘All the world’s a stage’) with a folk-song like strophic melody which never quite settled in either major or minor key, or into a perfectly steady metre. I hope that this approach captured the humour, the pathos, and the final note of optimism, in the jester Feste’s valediction.

Gabriel Jackson

Gabriel Jackson. Photo by Joel Garthwaite, used with permission.

Gabriel Jackson. Photo by Joel Garthwaite, used with permission.There were always going to be Three Shakespeare Songs, after Vaughan Williams. Three is a good number for Shakespeare songs. With three pieces, there can be a nice balance between contrast and continuity. Fast-slow-fast? Or perhaps slow-fast-slow? The texts themselves can dictate that. And that was the difficult part – choosing the texts, where with Shakespeare there is so much to choose from. Perhaps texts that have been set before should be avoided? But if all three are unfamiliar, perhaps they will be less attractive to performers? In the end, I settled for one very well-known text, and two relatively unfamiliar ones. What should they be about? How to ensure there is some connection between the three pieces, some reason why they are grouped together? At one stage I thought they should all be about music, but Shakespeare’s attitude to music is always more-or-less the same – it’s a good thing! In the end, I chose three nicely different texts (two speeches and a sonnet) that all mention music or singing. The commissioners wanted there to be no divisi in these pieces, just straight SATB; my natural instinct, when setting words as rich as these, is to create rich textures and big chords. So I had to try something different to make music for these wonderful words, and different is always good!

Cecilia McDowall

1. Give me some music

2. Mark how one string sweet husband to another

3. How sour sweet music is

Where better to start writing a new choral cycle than with texts drawn from Shakespeare. A composer’s task is always easier with good words, rich in imagery, and Shakespeare has given such inspiration over 400 years to countless artists. The quest for words, just the very right words, can be a long, tricky but interesting pursuit. These particular texts are a ‘mash up’ from six different sources, including Sonnet VIII (advocating the virtues of marriage) and ‘Much ado about nothing’ (insinuating that matrimony begins well, then it’s downhill all the way). The texts are unified by a musical theme; harmony, discord and rhythm. I looked for words which I hoped had not been previously set.

Photo courtesy of Cecilia McDowall. Used with permission.

Photo courtesy of Cecilia McDowall. Used with permission.As to how to set them, the words provide a ‘way in,’ suggesting the style, mood and direction of how the music could be. Beatrice’s description of the courtship procedure as being like a Scotch jig, all hot and hasty, is enough encouragement to think of Scottish fiddle music. And why not take it a step further and give the voices ‘mouth music’ to sing, a traditional Scottish style known as ‘puirt à beul’ (literally, ‘tunes from a mouth,’ usually something cheery). Then in the second movement, with the words, one pleasing note do sing, I’ve made the repeated ‘pleasing note’ a ‘blue’ note which I hope draws attention to itself. The final movement opens with a cynical unison laugh and the order to ‘keep time’ which should sound as though it is breathlessly not keeping time. All manner of discord follows rounding off the work with a collective pitch-less sigh. The rest is silence.

David Bednall

The toughest challenge in setting a Shakespeare text is probably the familiarity of the words in question and the certain baggage that they may carry – this was certainly the case for Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? It is possibly the most loved of all the sonnets, and certainly familiar from many marriage services, yet, nevertheless, remains timeless and fresh on each hearing. Added to this of course is the feeling of responsibility involved in setting words of such quality.

In making a musical setting of a text, one inevitably has to make choices of interpretation, and once these are made the feel of the work is set; obviously a performer has a certain leeway in their interpretation, but whereas the poem may be spoken or read in many different ways depending on the moment, orator, or reader, the musical setting is a more fixed entity. A further difficulty arises purely from the fact that this sonnet is in the first person whereas my setting is for choir. Against these difficulties of course there is the advantages bestowed by a text of immense poetic beauty and natural musical flow, filled with images that lend themselves to setting.

Howard Skempton. Photo by Katie Vandyck, used with permission.

Howard Skempton. Photo by Katie Vandyck, used with permission.My approach on the whole was simple and direct, allowing the words their full expression. I began, as always, by writing out the text in full, and then planning the musical structure, always governed by the words on both micro and macro levels, and deciding on the various musical textures which would provide variety and where these might be best deployed. A musical setting is almost inevitably more extended than a purely spoken one, so I chose moments which seemed to warrant and bear repetition in a sung context. I have always been much-inspired by the word-setting of Finzi, and strove to achieve a natural flow, hopefully painting something of their meaning in the music.

Howard Skempton

One of the most enjoyable aspects of composing vocal or choral music is going in search of a text, a task normally undertaken as one is finishing a previous piece. It is also exciting to be invited to set a text chosen by a commissioner (or editor of an anthology!), and the choice in this case was inspiring. My initial aim in setting ʻCome away, come away deathʼ was to devise a strong melodic line, one that might be worthy of inclusion in a production of Twelfth Night. The writing throughout the setting is essentially homophonic. The harmony attempts to strike a balance between tenderness and gravity, and is sometimes quite stark, as when colouring “my black coffin”.

Featured image credit: Ensemble by yunje5054. CCO public domain via Pixabay.

The post How did you approach setting the Shakespeare text you chose for your recent work? appeared first on OUPblog.

How much do you know about René Descartes? [quiz]

This August, the OUP Philosophy team honors René Descartes (1596–1650) as their Philosopher of the Month. Called “The Father of Modern Philosophy” by Hegel, Descartes led the seventeenth-century European intellectual revolution which laid down the philosophical foundations for the modern scientific age. His philosophical masterpiece, the Meditations on First Philosophy, appeared in Latin in 1641, and his Principles of Philosophy, a comprehensive statement of his philosophical and scientific theories, also in Latin, in 1644.

But how much do you really know about Descartes? Test your knowledge with our quiz below.

Featured image: Château d’Azay-le-Rideau, Indre-et-Loire, France. Photo by Jean-Christophe BENOIST. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How much do you know about René Descartes? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

August 12, 2016

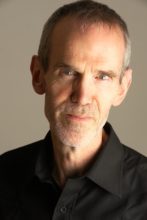

A collection of Victorian profanities [infographic]

Euphemisms, per their definition, are used to soften offensive language. Topics such as death, sex, and bodily functions are often discussed delicately, giving way to statements like, “he passed away,” “we’re hooking up,” or “it’s that time of the month.”

Throughout history, the English language has been altered by societal taboos. The role of social codes in the development of euphemisms can be explored through Victorian vulgarities. A woman who didn’t fulfill social expectations of purity or femininity may have been referred to as a “trollop.” Similarly, a man who lacked intelligence may have been written off as merely “beetle-headed.”

We list a variety of Victorian profanities in the infographic below.

Download the image as a PDF or a JPEG.

Featured image credit: “Victorian Ladies Fashion 1880s” by JamesGardinerCollection. CC0 1.0 Public Domain via Flikr.

The post A collection of Victorian profanities [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

5 Edinburgh attractions for booklovers [slideshow]

The Edinburgh Fringe is in full swing with over 3,000 arts events coming to the vibrant Scottish capital over the next few weeks. With the International Book Festival kicking off on the 13th, we’ve compiled our favourite bookish spots around the city for you to squeeze into your schedule.

You can explore more of Edinburgh’s local and literary history with the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Scott Monument, East Princes Street Gardens

This 1840 monument to poet, novelist and Edinburgh native Sir Walter Scott dominates the city’s skyline, towering over Princes Street Gardens to the south and the Georgian New Town in the north. Whether you have time to visit and climb the 287 steps or not, this dark and imposing Gothic landmark is quite literally unmissable.

“The Scott Monument, Edinburgh” by Gregg M. Erickson. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

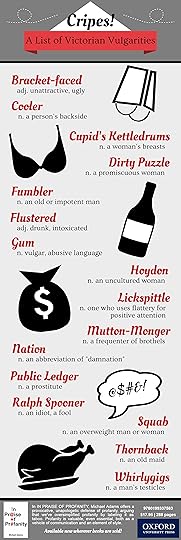

The Writer’s Museum, Lady Stair’s Close

Housed in a ramshackle castle-like building nestled in one of the many steep alleys off the Royal Mile, the Writer’s Museum is dedicated to the lives of Scott, Robert Burns, and Robert Louis Stevenson. Exhibiting rare books and historical artefacts – including Burns’ own desk – this is an immersive experience. Be sure to explore the courtyard too, where inspiring literary quotes are engraved into the paving slabs.

“The Writers’ Museum sign, Lady Stair’s House” by Kim Traynor. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

National Library of Scotland, George IV Bridge

Scotland’s National Library is located in the city’s Old Town on a street which is also home to the main branch of the public library service. The National Library’s somewhat austere frontage is countered by a light and airy foyer, beyond which you’ll find free exhibitions relating to the literary history of Edinburgh, Scotland, and beyond.

“National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh” by Kim Traynor. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Calton Hill

The surreal Calton Hill features a monument to Scottish philosopher and mathematician Dugald Stewart, and the unfinished National Monument of Scotland, inspired by the Parthenon in Athens. It’s a gentler climb than Arthur’s Seat, but Calton Hill still provides an expansive view across the city.

“ViewAlongNationalMonument” by Duimdog. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Clarinda’s Tearoom, 69 Canongate

While it’s not quite as famous or historically significant as some of the other places on this list, Clarinda’s is an adorably quaint café in which to refuel during any busy trip to Edinburgh. Olde-worldy décor and a stunning array of traditional cakes make it an experience somewhere between visiting your grandmother and falling into a Jane Austen novel.

“Golden Wedding celebrations at the Orthopaedic Hospital, Gobowen” by Geoff Charles. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: “Athens of the North” by anonymous. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post 5 Edinburgh attractions for booklovers [slideshow] appeared first on OUPblog.

A commemoration and a counter-revolution in the making

A major event which hogged media coverage in July 2015 was the 25th anniversary of India’s economic reforms (1991). However, that coverage missed out the unintended and decisive contribution that economic reforms made to India’s quest for ‘universalising’ primary education (UPE), mainly because that contribution is little known. The Indian Constitution cast an obligation on the State to provide free and compulsory education to children in the age group 6-14. As early as 1966 the Kothari Commission had recommended that each district should prepare and implement a perspective plan for fulfilling the Constitutional obligation. It was only in 1992, a year after the launch of economic reforms, that the Kothari Commission’s idea of a district plan for UPE became an idea whose time had come.

Two factors contributed to the quantum leap caused by the idea of district planning. Firstly, the Total Literacy Campaign, which caught the nation’s attention; the success of quite a few districts in becoming ‘totally literate’ imparted a new thrust to UPE because it became clear that success would be ephemeral if an inadequate schooling system spawned year after year a new brood of illiterates. That success also gave rise (subliminally) to the question why the district-based strategy which made many districts ‘fully literate’ cannot be applied to elementary education. The second factor comprised a confluence of developments.

One such development was the critical dependence of India on the World Bank’s assistance to tide over the unprecedented macroeconomic crisis which left no option but to launch economic reforms. Another was the World Bank emerging as a champion of providing elementary education to all children, taking a lead role in organising the World Conference on Education for All in Jomtien, Thailand (1990), and assigning a high priority to elementary education in its lending policies. The World Bank offered a fast disbursing social safety net loan to tide over the acute balance of payment crisis, and help India plan effective programmes in areas like elementary education.

‘IMG_3477,’ by melgupta. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

‘IMG_3477,’ by melgupta. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Few know about India’s response to the World Bank’s insistence, and how MHRD availed the opportunity to ‘operationalise’ the Kothari Commission’s recommendation, and develop the District Primary Education Programme (DPEP). Together with its progeny Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), the DPEP was responsible for the rapid strides that India made in reducing out-of-school child population in 1993 to a mere 0.3 percent in 2010 when the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act (RTE Act), 2009, came into force. Few know how DPEP blazed a new trail in development cooperation and precociously introduced many practices commended by the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (2005). for example, such as the recipient country taking a lead in developing a strategy for achieving goals and objectives in a given sector, developing a programme for implementing that strategy, and the country exercising leadership in coordinating the contributions of different funding agencies. India’s experience is of great interest not only to educationists and education policymakers but also to many developing countries as well as theorists and practitioners of development cooperation.

Yet another event which received some attention was the publication by the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) of the consultation document Some Inputs for Draft National Education Policy 2016. From the perspective of the history of thought, the RTE Act accomplished a revolution overturning two of the cardinal postulates of the National Policy of Education, 1986. First, given the Indian socioeconomic reality, UPE cannot be achieved only through formal schooling and that a large and effective system of non-formal education (NFE) should complement the school system. Secondly, education being all about learning it is imperative to lay down essential levels of learning for each grade and assess how far these levels are achieved by the students. These cardinal postulates were overturned by the RTE Act which can be perceived as a successful revolution by constructivist pedagogues. Based on consultations with State Governments MHRD’s Input Document proposes to restore NFE as well as assessing learning with reference to norms of learning. The New Education Policy as and when announced would be a counterrevolution against constructivist pedagogy if it incorporates the proposals of the Input Document. Whatever, an intense policy debate could be expected over these proposals.

Featured image credit: Children inKarnataka India by gauthamkanchodu. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post A commemoration and a counter-revolution in the making appeared first on OUPblog.

Facing the Führer: Jesse Owens and the history of the modern Olympic games

Enjoying Rio 2016? This extract from Sport: A Very Short Introduction by Mike Cronin gives a history of the modern Olympic games; from its inspiration in the British Public school system, to the role it played in promoting Nazi propaganda.

The modern Olympic Games, and their governing body, the International Olympic Committee (IOC), came into being in 1894 and were the brainchild of Pierre de Coubertin. A Frenchman with a passionate interest in education, de Coubertin had visited England. He toured several public schools while there, including Rugby School, where he was said to have been inspired by the reformist headmaster Thomas Arnold, and the way in which school sport was used to create moral and social strength. De Coubertin also placed great store in the sporting and philosophical approach of the Ancient Greeks, and through meetings with Dr William Penny Brookes, founder of the Much Wenlock Olympian Games in 1850, had been able to understand how a multi-sport competition might work. The various events and traditions that de Coubertin had observed came together in 1889 when he finally conceived the idea of reviving the Olympic Games. After a series of meetings involving figures interested in sport from across Europe, the IOC was formed in 1894, and, with the support of the Greek government, the first revived Olympic Games scheduled for Athens two years later.

De Coubertin and the IOC’s thinking in these early years is instructive in understanding the spirit that is said to underlie the contemporary games, and also the ways in which the Olympics have deviated from their original goals. The Games, as conceived by de Coubertin, would have a philosophical underpinning, often referred to as Olympism, and much of his inspiration was drawn from his own romanticized reading of the ancient Games. He believed that the spirit of competition was central, but that the taking part was more important that the winning. He argued that the competition should be restricted to amateurs, and that the Games, building on the idea of the ancient Olympic truce, should bring about a spirit of peace between competing nations. Whatever the ethical underpinning of the Games, the first Olympics in Athens were deemed a success. Despite a relatively hasty process of organization, and a lukewarm response to the whole Olympic idea from some leading nations such as the US (which brought a team of only 14 that was mainly drawn from the athletic teams of Harvard and Yale), the Games were popular amongst Greeks and garnered a good deal of international press coverage.

In 1900 in Paris, and in 1904 at St Louis, the Games were side attractions to a World’s Fair being held simultaneously in the host city, and failed to elicit any great enthusiasm. So disjointed were the Games in St Louis, and so subservient to the World’s Fair, the sporting competitions stretched from the opening event on 1 July until the close on 23 November. Only 12 nations competed, and most with small teams. The US team, with 526 athletes, dominated the total field of 623 athletes. The 1908 Games were originally awarded to Rome, but were relocated to London after the Italians faced financial problems following the costs associated with clearing up the 1906 eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Although a host city of expediency, many argue that London managed to stage the first recognizably modern Olympics featuring 22 competing nations. It was also the first Games that featured athletes marching into the stadium during the opening ceremony behind their national flags, and as a result one of the first political disputes when the US flag bearer, Ralph Rose, failed to dip the Stars and Stripes when his team passed the viewing platform where King Edward VII sat.

Berlin, Olympiade, Siegerehrung Weitsprung by Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-G00630. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Berlin, Olympiade, Siegerehrung Weitsprung by Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-G00630. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The Games were disrupted during the First World War, the 1916 Games originally scheduled for Berlin were cancelled, and the defeated War powers banned from competing in 1920 and 1924. In the inter-war years the Games grew steadily, with the Winter Olympics added in 1924, and staged at Chamonix in France. The 1936 Games were awarded to Berlin, and the ruling Nazi party transformed the Olympics from an international athletic competition into a mega-event infused with political rhetoric and spectacle provided specifically to enhance the status of the host city (and by proxy, the host nation). Conceiving the Games as an opportunity to showcase the positives of Nazi rule, the 1936 Olympics serve as a byword for a state propaganda display. Despite the intense politicization of the event by the Nazis, many of their innovations would become standard features of future Olympics Games. It was the first Games where there was a torch relay, the first to be televised, and, under the directorship of Leni Reifenstahl, the first to be filmed and produced as the documentary movie titled Olympia. They were also the first Games to be used as a political tool by other nations states with a point to make, and Spain, the Soviet Union, and Ireland all boycotted the event.

Given that the Berlin Olympics were staged to showcase the merits of Nazi ideology, it is perhaps the performance of Jesse Owens that best symbolizes the inherent contradictions of 1936. Given Nazi race policies, the party’s newspapers suggested in the run-up to the Games that Jewish and black athletes be barred from entering. Faced with a potential US boycott, entry was left open to all, but the victory of African-American Owens, in the 100 m final, in front of Hitler, proved a visible rebuke to Nazi claims for the supremacy of the Aryan race. That said, the race politics of the US at the time were equally poisonous. Despite his propaganda boosting defeat of the Germans in front of the home Nazi crowd in Berlin, Owens was never invited to the White House by President Roosevelt, and on the occasion of a reception to mark his gold medal victory, after his homecoming, he was made to use the goods elevator rather than the one in the main lobby which was reserved for whites. While grandiose in its propaganda use by the Nazis, the 1936 Olympics proved that the Games were a political football, and that competing, winning, or even boycotting could score important political and cultural points.

Featured image credit: Jesse Owens sprinter by WikiImages. Public domain via Pixabay

The post Facing the Führer: Jesse Owens and the history of the modern Olympic games appeared first on OUPblog.

August 11, 2016

Some very short reflections on social psychology

For as long as I can remember, I’ve never been able to understand the ‘logic’ of prejudice: how anyone could justify the derogation of others simply on the basis of their culture, gender, religion, or race. Of course, the causes of prejudice are many and varied, and we need contributions from many different disciplines – history, politics, economics – to fully understand what they are, and how they can be addressed. For me, however, there was always something deep in the human psyche that cut to the heart of prejudice. As well as the systemic (economic), structural (organisational) and social (policy) factors, there seemed to be something that linked all three; something that shapes how we perceive these external forces; something that determines whether we react to them with tolerance or intolerance. It turns out that the study of how we understand, and react, to these social forces, is precisely what social psychology is about.

So I leapt in to the field. In my early explorations, it didn’t take long for me to stumble upon Henri Tajfel’s famous ‘minimal group paradigm’ (MGP) studies, conducted in the 1970s. Tafjel was driven by that same desire to understand the nature of prejudice. His MGP was an experimental ‘game’ that revealed the utter irrationality of prejudice. In the MGP there was no possible gain for people to favour their own group: everyone was anonymous, and the identities involved were explicitly artificial and meaningless. Nonetheless, under these most minimal of social conditions (i.e., the simple division of people in to “us” and “them”) people still showed prejudice.

What emerged from these studies was a whole area of psychology that revealed the motives and processes that drive peoples’ prejudices. Discovering that it was a basic tendency to categorize that lies at the heart of prejudice had huge implications. It meant that to tackle prejudice we have to not only address the social, the economic and the political: we also need to tackle the psychological.

Armed with this insight I set off on (what became) a 20-year quest to develop an educational and training initiative to tackle the cognitive foundations of prejudice. The result was ‘Imagined Intergroup Contact’, a mental simulation technique that models interactions between people from different cultures and groups. The reasoning was that in the absence of actual contact, people might imagine that encounters with other groups would be negative – and develop negative stereotypes accordingly. If that is the case, then perhaps we can reverse this idea by getting people to imagine the opposite – positive outgroup encounters. Early results supported the idea that simply imagining contact could be useful as a way of reducing prejudice, and promoting an interest in engaging positively with other groups. There have now been well over 100 studies of imagined contact, involving thousands of participants. These studies have found the approach to be effective in tackling prejudice against a whole range of groups, including those formed on the basis of race, religion, gender, ethnicity, and sexuality.

It meant that to tackle prejudice we have to not only address the social, the economic and the political: we also need to tackle the psychological.

The technique has been hugely successful at promoting more positive group-based interactions, reducing prejudice, and empowering individuals with confidence and self-efficacy. It’s such a simple idea, but one with so much power and potential. To see it grow from a flash of inspiration to a research programme to a multi-lab global endeavour is immensely rewarding. Most importantly, I passionately believe imagined contact has the power to change peoples’ lives for the better. Seeing a scientific advance like this begin to be adopted in education and industry gives a real and important sense of meaning to what we do.

And the future? What’s so exciting about research is you really don’t know what’s around the corner – there are so many possibilities. I do strongly believe there is a need for us to better connect basic science with application, to build stronger pathways to impact, and harness scientific advances to effect real and positive change in the societies in which we live. It’s also true that research in all areas is increasingly multi-disciplinary. I think this trend will continue; for me this means an exciting, closer integration between psychological, economic, and social policy approaches. For Imagined Contact research, this can only be a good thing. Cross-fertilization of ideas will help us build a better picture of the processes that lead to the formation of prejudiced attitudes, and through this understanding, will help us develop new interventions to tackle this most pressing of social problems.

Inter-disciplinarily, however, does not mean, and should not mean, complexity. Complexity can be beguiling – a complex idea, one that is difficult to understand, can seem correct precisely because it is difficult to understand. Getting people to believe that a simple idea is sometimes the best idea can be a challenge. But if developing Imagined Contact has taught me anything it’s that sometimes the simplest ideas can be the most powerful.

Finally, none of us must be afraid to suggest new ideas, even if they go against received wisdom. All science needs new perspectives, and this is what makes working in these areas so thrilling and rewarding. Sometimes you’ll be wrong, sometimes you’ll be half right … but perhaps sometimes you’ll have something that no-one else has ever thought of before. Whatever your discipline and whatever your field, your ideas could well be the next big thing.

Featured image credit: Crowd by tinabold. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Some very short reflections on social psychology appeared first on OUPblog.

Remembering Montrell Jackson’s ethic of mutuality

In a poignant post to his Facebook page on 8 July, police officer Montrell Jackson offered a “hug” and “prayer” to those he met as he patrolled the streets of his native Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Jackson was meditating on the bloodshed of the previous day: the death of five law enforcement personnel in Dallas, Texas, at the hands of a sniper, and the subsequent killing of the suspect at the mechanical hands of the police. But in a way he never could have anticipated, Jackson’s comments would come to serve as an interpretive key, not just for this violence, but also that which would claim his own life days later.

For those looking to fit life to the patterns of literature, the events of the past weeks have had the unsettling feel of a revenge tragedy: Philando Castile and Micah Xavier Jackson; Alton Sterling and Gavin Long; St. Paul and Dallas; Baton Rouge and Baton Rouge.

It is perhaps for this reason that the vision of reciprocity that Jackson expressed has gained such appeal. If the risk of revenge is that it sets off an endless cycle of destruction, then Jackson offered another, more appealing way. His model of mutuality—democratic in its dispensations—has informed the public comments of Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards and inspired the hashtag #IGotYou.

But Jackson’s ethic ought to unsettle us too. In extending his offer of fellowship to “protesters, officers, friends, family,” he invited an exchange with those familiar to him and not—which is to say: with those who knew him and who thought they knew him. This is the sort of exchange that the Harvard political philosopher Danielle Allen has called “talking to strangers,” a crossing of boundaries and borders that necessarily violates the parental wisdom that would keep us in our narrow precincts. And in the context of the United States, past and present, those spaces still remain defined largely by black and white.

In the face of this reality, the calls for empathy and openness coming from President Obama and other political figures make a certain kind of sense. These human resources surely offer one way forward.

But we will stumble if we focus exclusively on going on. For empathy is also about the way back. It is about the personal and public past.

This was the insight that motivated the great American writer Ralph Ellison in the novel he set out to compose after Invisible Man. The book follows Alonzo Hickman, a Southern black preacher who travels to Washington, DC, to save a Senator from an assassination attempt. Visibly a white man, the Senator was reared by Hickman but has fled his past and come to peddle the politics of racism.

In a particularly rich passage, after he and his fellow travelers have returned from a visit to the Lincoln Memorial, Hickman reflects on the ties that hold the group together—and those that bind the rest of us, for better or worse. “It was possible that the virtues of charity and sympathy depend as much upon one’s memory of the past as upon one’s hope for heaven,” he remarks. Enlarging this reflection into an ethical principle, he continues: “For perhaps true charity depends upon our memory as much as upon our willingness to identify with those to whom it’s extended.”

The idea here—inspiring as it is striking—is that it’s not enough to extend ourselves to one another. The hug and the prayer Jackson offered are necessary, to be sure. But living among and with others in democracy requires something more. For Ellison, it was the sense that encountering and identifying with fellow citizens also meant confronting our memories, both those we share and those we do not. To live among others is to tell and listen to stories of personal and public pasts.

Ellison worked on his second novel for nearly five decades, but he never finished it. Perhaps one reason was that the story he told—of fathers and sons, black and white, struggling with their pasts, and a nation wrestling with its own—was itself not finished, and remains so now.

The past weeks have made this truth clear enough. Perhaps one way to go forward, then, is to move back, into the personal and public histories of which these acts of violence are the symptoms. There may be no better way to remember Montrell Jackson and ethic of mutuality to which he gave voice.

Featured Image: “Shadows” by Kevin Dooley. CC BY 2.0 via flickr.

The post Remembering Montrell Jackson’s ethic of mutuality appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers