Oxford University Press's Blog, page 475

August 19, 2016

Video didn’t kill the radio star – she’s hosting a podcast

When we’re not busy plotting to make Oxford University Press’s social media all oral history all the time, we occasionally branch out to see what oral historians are doing in other corners of the internet. This week we bring you one of our favorite recent pieces, in which Siobhán McHugh discusses the growth and power of podcasting. Originally published in The Conversation, the article explains some of the reasons why podcasting offers potential for social engagement and even social change. McHugh’s article in OHR 39.2 on the “Affective Power of Sound” was selected for re-publication as part of our special 50th anniversary virtual issue, which will be released in the coming weeks

Podcasters P.J. Vogt, host of Reply All, and Starlee Kine, host of Mystery Show, addressed sold-out sessions at the Sydney Writers’ Festival last month, riding the wave of popularity engendered by Serial, the 2014 US true crime podcast series whose 100 million downloads galvanised the audio storytelling world.

Over 12 weeks, using a blend of personal narratives and investigative journalism delivered in ultra-casual conversational style, host Sarah Koenig examined the case against Adnan Syed, a Baltimore high school student who had been convicted of murdering his ex-girlfriend, Hae Min Lee, in 1999.

In risky but inspired innovation, the series launched without a conclusive ending. It invited listeners to veer with Koenig through the unfolding evidence – a departure hailed as making journalism more transparent, in a genre not without ethical conundrums. The show fomented raucous chatrooms online and Koenig featured on the cover of Time magazine.

“Hosting” is at the heart of the vaunted podcasting revolution that has seen comedy, “chumcasts” (friends riffing on a theme) and deeply personal storytelling vie with established radio documentary, feature and interview formats for audience share. In radio institutions such as the ABC or BBC, programs have “presenters” and the organisation adds further brand identity. In the ever-expanding podsphere (over 350,000 podcasts are listed on iTunes), “hosts” speak directly into our ear.

This seductive intimacy affects both the form and content of the audio storytelling genre. It appeals to listeners from hitherto untapped demographics as well as to rusted-on audiophiles – a development being watched by both advertisers and activists.

In the predominantly English-speaking 12-year-old podsphere, producers and consumers of podcasts used to be mainly young, white, educated, affluent males. But, in the last two years, female listenership has doubled. Female hosts are storming the studio (or bedroom, where many an indie podcast originates, or garage, where US comedian Marc Maron famously conducted a deeply revealing interview with Barack Obama last year).

“Hosts are really forming relationships in new ways with their listeners,” says Julie Shapiro, CEO of Radiotopia, “a curated network of extraordinary, story-driven shows” founded in 2014. It now has over ten million downloads a month of its 14 shows.

Radiotopia’s recent “Podquest” competition attracted 1,537 entrants from 53 countries. The finalists propose shows that feature marginalised voices and quirky perspectives, delivered as engaging crafted narrative.

Radiotopia and Gimlet, the independent US network that hosts Kine and Vogt, have been created by former public radio broadcasters. They still proclaim the editorial values and lofty mission articulated when National Public Radio (NPR) was founded in 1971.

The podsphere is unregulated – open slather for hate speech and religious rants, with the medium already exploited by groups like ISIS. But minorities are also colonising the space, with growing audiences for shows on transgender issues, gender, sexuality and race.

In Australia, both public broadcasters are developing podcast-first formats. SBS has True Stories, unusual tales of multicultural experiences, and the ABC offers First Run, which ranges from comedy to entertaining history.

But other organisations, from community radio to independents, are now able to compete for listeners. Longtime ABC star Andrew Denton partnered The Wheeler cultural centre in Melbourne to launch his excellent podcast series on euthanasia, Better Off Dead.

Other veteran radio journalists are going solo. In 2015, US producer John Biewen, whose work has featured on prestigious outlets including This American Life, NPR and the BBC, launched his own show, Scene On Radio. He told me:

Liberation from broadcast gatekeepers and formats outweighed the advantages they bring … the only downside … is the loss of audience numbers. [But] the freedom to produce work in the tone and at the length that I choose is priceless.

Thrillingly, podcasts can be as long as a piece of string. Audio producers can focus on a natural narrative shape rather than artificially moulding a story to a pre-ordained duration. This enhanced Serial’s appeal and opens new structural possibilities for the form.

At one end, we may see podcasting develop further as a form of literary journalism: a poetic or narrative audio genre long established in Europe and articulated by the New Journalismof the 1960s and ‘70s. It incorporates qualities such as immersive reportage, scenes, evocative writing and a subjective point of view.

At the other end of the spectrum, cheaply produced podcast panel-fests are proliferating. The topics range from the elections in Australia and the US to race and popular culture. Some of these sound clunky and turgid – print journalists operating in a medium they don’t yet get. Others, such as Buzzfeed’s Another Round, have the chemistry and the tone spot on, snaring big names such as Hillary Clinton along the way.

This rapidly evolving podcast ecology is coming under increasing academic scrutiny.

Meanwhile, the race continues to find the next Serial. The second season of Serial, about the troubled Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl, a US soldier held captive by the Taliban for almost five years, didn’t quite manage it. Canada’s CBC got close with Somebody Knows Something.

The best candidate yet is The Bowraville Murders, unexpectedly well produced by The Australian newspaper, in which rookie podcaster Dan Box investigates the unsolved murders of three Aboriginal children from the same small town 25 years ago, bringing raw pain and kneejerk racism directly to listeners.

Having received scant attention for his other crime reportage, Box was astonished by the reaction to the podcast: it has probably been instrumental in launching a fresh trial. Its power lies in fundamental aspects of the audio medium: its capacity to convey emotion and evoke empathy, imagination and intimacy. When those strengths are harnessed, podcasting becomes a formidable force for social engagement.

Want to read more from McHugh about radio, podcasting, and the future of oral history? Check her out online at www.mchugh.org or through her article “The Affective Power of Sound: Oral History on Radio” published in OHR 39.2. Add your voice to the conversation by chiming into the discussion in the comments below, or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

Featured image: Microphone by NikolayF, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Video didn’t kill the radio star – she’s hosting a podcast appeared first on OUPblog.

A Copernican eye-opener

Approximately 500 years ago a Polish lawyer, medical doctor, and churchman got a radical idea: that the earth was not fixed solidly in the middle of all space, but was spinning at a thousand miles per hour at its equator, and was speeding around the sun at a dizzying rate. Unbelievable, critics said. If that were true, at the equator people would be spun off into space. And it would be much harder to walk west than east.

Copernicus’ book, On The Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, was finally printed in 1543, the last year of his life. Few people got upset by its world-shaking proposal, to fix the sun in the middle of a planetary system. It was too technical for common folk to understand, and the specialists regarded it as a recipe book: how to calculate the positions of the stars and planets, but not a description of physical reality. Nearly a century and a half would pass before a majority of educated people would accept that the earth was really spinning around the sun.

But writing a Very Short Introduction to Nicholas Copernicus posed a serious dilemma: how not to trivialize the monumental move from geocentric to heliocentric on the one hand, or get bogged down on the computational details that fill his book on the other. For example, an important part of his On The Revolutions shows how to use a minimum number of carefully chosen observations to set up the tables for finding the positions of the planets at any time of the past or future. Not the stuff for casual reading or philosophical posturing.

And then a solution occurred to me: I could chose a single example of a long calculation and put it in an appendix. There any reader who wanted an idea about the calculations could take a peek without getting totally involved. For my example I chose the position of Mars in the sky on February 19, 1473, which happens to be Copernicus’ birth day. What happened next was a real eye-opener. I had made similar calculations before, and figured I would have the copy for the printer in about three days. Instead, it took nearly a month.

Finding some of the numbers buried in the text (rather than in a neat table) was not so easy. Precisely how Copernicus was treating the so-called precession was another stumbling block. Choosing which of very similar (but modestly different) tables was like a poorly marked detour. And one critical key number he did not give at all, as if he had forgotten a required table. In thinking about this situation, I realized that from the book’s publication in 1543 through to 1550, there was only a single volume of planetary positions based on Copernicus’ numbers, authored by the Polish astronomer’s only student. Not until 1551, with the publication of a revised set of Copernican numbers, did his planetary positions take their stand in the astronomical marketplace.

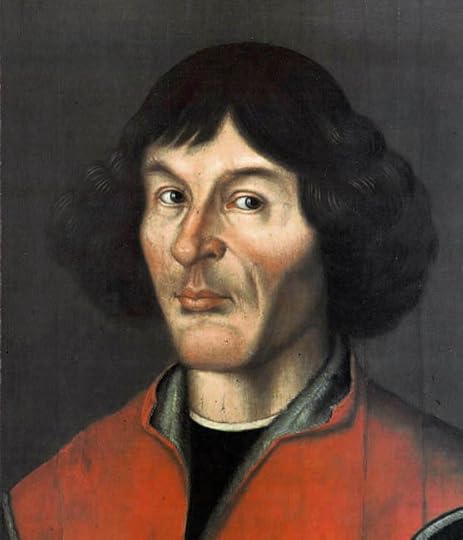

Nicolaus Copernicus portrait from Town Hall in Toruń – 1580 by unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Nicolaus Copernicus portrait from Town Hall in Toruń – 1580 by unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Georg Joachim Rheticus, Copernicus’ only student, had had to work very hard to persuade the Polish master to allow his book to be published. Now we can only wonder: was Copernicus so reluctant to publish because he knew that his book was not really finished? Copernicus’ De Revolutionibus was not for everyone — it was of course in Latin and too technical for those who hadn’t been to a university. There’s a very amusing section in Robert Recorde’s popular astronomy book of 1556, where the Master mentions Copernicus, “a man of greate learninge, of much experience, and of wonderful diligence in observation.” To which the Scholar replies, “Nay syr in good faith, I desire not to heare such vain phantasies, so far againste common reason and repugnante to the consente of all the learned multitude of Wryters, and therefore let it passe for ever, and a daye longer.”

But the Master has the last word: “You are too younge to be a good judge is so great a matter: it passeth farre your learninge and theirs also that are much better learned then you, to improve his supposition by good argumentes, and therefore you were best to condemne no thing that you do not well understand.” It was in the next century that Isaac Newton’s picture of gravity showed why people at the equator would not be spun off into space by the spinning earth, and if there were any doubts left, the successful predicted return of Halley’s comet in 1759 clinched the basic picture of the Copernican system. Despite his reservations about the last chapters of his book, Copernicus would have been both surprised and pleased that if his heliocentric system didn’t give a final blueprint for the solar system, at least the sketch was recognizably correct.

Featured image credit: Sun Planet Solar System by Valera268268. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post A Copernican eye-opener appeared first on OUPblog.

August 18, 2016

Is College Radio Relevant?

You take out the scratched up Beatles’ Abbey Road LP from its musty slipcover, cue it onto the turntable, and broadcast it to the small, rural area surrounding your college campus. It’s 5:00 AM, you’re the only one in the booth, and you ask yourself: is anyone listening? Does what I’m doing matter? Little do you know, as you speak into the microphone introducing “Here Comes the Sun” (as the sun is literally rising), you are part of a long history of college radio. But how is college radio relevant today?

Despite the rise of popular broadcasts ranging from sportscasts to music countdowns, radio has generally been on the decline. We have turned the dial to its off position and turned on our smartphones, abundant with news, traffic reports, YouTube, and pretty much everything the radio can give us without commercial breaks. Yet, mainstream radio largely remains a stable part of society, especially for when we cannot reach our phones, such as during rush-hour traffic on the Long Island Expressway or spontaneous weekends to the Poconos. But how does college radio fit into the equation?

College radio stations are as much for the disc jockeys as they are for the listeners, if not more. Since 1917, when the first college radio station was believed to be introduced at University of Wisconsin, Madison, college stations have become important community hubs for students and alumni. Music lovers, hopeful news anchors, and misfits unite to air their tunes and thoughts for all (well, those within a few miles) to hear. Many campuses are free-format, meaning they can broadcast anything they want within FCC rules, something that marketed, commercialized radio lacks. Just like the unofficial Quidditch team exists for Harry Potter enthusiasts to express themselves, college radio exists for students to do the same, whether it is through music, a sports broadcast, or even spoken word poetry.

Music Technology Radio Musical. Photo by Clubfungus. CC0 via Pixabay.

Music Technology Radio Musical. Photo by Clubfungus. CC0 via Pixabay.Although free-formatted, college radio stations do not take their commitment to the radio spectrum lightly and, in fact, have used their standing as an educational center to maintain the integrity of early radio. For example, exactly 75 years after it was first broadcasted, Binghamton University – SUNY aired the original broadcast of “War of the Worlds,” the infamous H.G Wells’ adaptation that sent Americans running around in fear of an invasion, on October 30th, 2013. “War of the Worlds” marks a significant piece of history as it exemplifies the power the media has on its audience. WHRW 90.5 FM Binghamton, the campus’ radio station, blocked out three hours and threw a listening party for the event, which followed a talk led by professors and scholars to discuss the impact of the work. College radio stations have the opportunity, resources, and even audience to create an intriguing learning experience on various subjects.

Furthermore, while many participate in college radio for the community and for fun, it also prepares students with real-life experience. Many campus stations feature news shows, sports programs, and public affairs broadcasts, preparing students for careers in journalism, television, and more. This undoubtedly allows students to receive important media experience they may not be able to find anywhere else on campus. Whether it is through research, working with others, or preparing their own material, there is transferable experience in much of what a disc jockey or reporter does at his or her college radio station. Who knows, maybe your favorite morning show news anchor got their early start in college radio.

College radio may not even be a blip on your dial, but it is an important educational and social staple for campuses around the world. For some, the booth is a place to blast an old cassette tape and drown themselves in loud drum solos, and for others it is a place to get experience before graduation tosses them head-first into adulthood. For most, though, in a world that is dominated by the digital age, it is where we can remain true to the integrity of the radio and express ourselves in new, and even undiscovered, ways.

Headline Image Credit: Radio Recorder Boombox Old School. Image by Heissenstein. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Is College Radio Relevant? appeared first on OUPblog.

Designer nature: mosquitoes first and then what?

It seems that every time I retrieve a magazine from my mailbox these days, I find an article about how we’re going to drive mosquitoes to extinction. The June issue of Smithsonian’s featured, “A World Without Mosquitoes” and the August National Geographic proclaimed, “Science vs. Mosquitoes” (it’s not hard to guess who wins). Through the technological wonder of CRISPR-Cas9 combined with gene drive, we’re told that we can insert a gene to confer sterility and this trait would race like wildfire through Aedes aegypti. Why this species? Because it’s the vector of the Zika virus—along with the dengue and yellow fever viruses. The problem is that A. aegypti isn’t the only culprit. It’s just one of a dozen or more bloodsuckers that will also have to be wiped out. After we’ve driven these species to extinction, we’ll presumably move on to the Anopheles species that transmit malaria. That’ll be another 40 extinctions, but once we have the technology rolling it should be readily applicable to all sorts of pests. But let’s slow down for a moment and ask a few questions about the new genetic technology before we start intentionally reshaping life on Earth (we’ve been wiping out species for some time, but most of these losses are the collateral casualties of habitat destruction).

Can we drive targeted species to extinction?

Well, maybe. We chuckle at those who told budding entomologists to be sure to collect specimens of pests because DDT would soon eliminate all sorts of insects. The evolutionary power of insecticide resistance was unimagined in the 1940s. Perhaps we are being equally unimaginative with CRISPR as a method of extinction. After 30 years of working in pest management, my money is on the insects. Although I’m not sure how they’ll humble us this time, they’ve outfoxed our technological prowess up until now. But let’s suppose I’m a poor gambler.

Should we drive species to extinction?

Anopheles stephensi (the primary vector of malaria in urban India). This image is a work of a US Department of Agriculture employee. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Anopheles stephensi (the primary vector of malaria in urban India). This image is a work of a US Department of Agriculture employee. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.There are those who advocate wiping out vectors entirely. But this seems like overkill, so to speak. Why eliminate an entire species—along with all of its ecological functions, most of which we don’t know? It seems much more sensible to eliminate the capacity of the species to spread disease (technically speaking, insects transmit pathogens and the pathogens cause disease, so vectors don’t’ really “spread disease” but “spread disease-causing agents” is awkward and you know what I mean). Researchers at Harvard Medical School used CRISPR to remove all 62 occurrences of retroviruses embedded in the porcine genome which make using pig organs unsuitable for transplantation to humans. So why not wipe out a few mosquito genes rather than the whole species? But let’s suppose that we decide for forge ahead.

How do we decide where to stop?

Reshaping genomes to fit our needs is the first step. Then comes redesigning life to accord with our wants: our desire for noiseless cicadas (they can be so disruptive), stingless honeybees (no reason to put up with their bad attitude), or poop-less aphids (nobody likes honeydew and sooty mold on their shiny car). And why stop at a world without vector mosquitoes? Surely, we’ll wipe out the nuisance species that afflict us with itchy bumps. And fleas can go, along with cockroaches, locusts, ticks, starlings, rats, and raccoons (I’ve been battling these garden invaders for years). Okay, some people will want to keep raccoons. So how do we decide where to stop—and who gets to decide for the rest of us? But let’s suppose that I’m a worrywart and we figure out what goes and what stays.

What else might we eliminate along with genes and species?

Much has been written by philosophers for 2500 years about what it means to be human. Beginning with the Greeks, a great deal of discussion has revolved around the virtues which give meaning to our existence. These are the character traits which we cultivate in an effort to realize our potential, to lead a good life, and to become fully human. There are various candidates for the virtues, such as courage, mercy, justice and fidelity. But most frameworks include some version of temperance. A life worth living entails self-control and moderation. Perhaps the modern formulation would be humility—understanding that we are not the sole end of existence, that human comfort is not the purpose of life on Earth, and that our wants can be trumped by others’ needs. I am concerned about an arrogant restructuring of organisms and ecosystems, but I’m most deeply worried about what this means for human morality. We can easily reshape genetic traits of other species, but can we preserve the character traits of our own species?

Featured image credit: Electron microscope image of Zika virus (red), isolated from a microcephaly case in Brazil. Image by NIAID. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Designer nature: mosquitoes first and then what? appeared first on OUPblog.

August 17, 2016

As black as what?

All words, especially kl-words, and no play will make anyone dull. The origin of popular sayings is an amusing area of linguistics, but, unlike the origin of words, it presupposes no technical knowledge. No grammar, no phonetics, no nothin’: just sit back and relax, as they say to those who fly overseas first class. So here is another timeout. I have recently discussed the simile as clean as… and decided that its opposite or near opposite, namely, as black as… might also be interesting to our readers. Once again I have chosen only such phrases that are represented fairly well in my database. And true to my pattern, I will not attempt to solve the origin of the similes. My goal consists in presenting the material for the entertainment of the public, with the usual expectation that some people know more about those similes than I do and will share their knowledge with us.

As black as Itchul. The saying was (or perhaps still is) known in Sussex, though, seemingly, not only there. The question is familiar: “Who or what is itchul?” An ingenious explanation, redolent of folk etymology, runs as follows. Sailors were in the habit of saying as black as hell, but in those days when certain words “offended the ears of children and tittering spinsters,” hell was often spelt h—l and pronounced as aitch-el; hence itchul, to my mind, a creature possibly related to the spotted and herbaceous backson. On the other hand, Old Engl. ysel meant “ember, spark.” Is itchul a garbled reflex of that noun? I also wonder: Can Itchul (with capital I) be a “corruption” of the name of some witch or of a name like Isabel ~ Isobel? The fisherman’s wife in the Grimms’ tale was called Ilsebill.

As black as Newgate Knocker. At one time, this simile was known quite well. In his often-consulted dictionary of slang (1859), John Hotten wrote that Newgate knocker is “the term given to the lock of hair which costermongers and thieves usually twist back towards the ear. The shape is supposed to resemble the knocker on the prisoners’ door at Newgate—a resemblance that carries a rather unpleasant suggestion to the wearer.” Why street vendors dealing in fruit and vegetables treated their hair like thieves and why thieves revealed their identity in such a conspicuous manner remains unclear, but assuming that Hotten’s information is true, we still do not know why the color of the said knocker (not a particularly memorable heavy ring) inspired the ominous simile.

This is the Newgate knocker of ill repute.

This is the Newgate knocker of ill repute.According to a suggestion made in 1940, the reference was probably not to Newgate prison, where felons were incarcerated after conviction, but to the turreted Newgate, part of the City wall that spanned Newgate Street, slightly east of Giltspur Street and the Old Bailey. Burned down in 1666, it was rebuilt in 1672 and demolished in 1777 as an obstruction to the traffic. It was here that those committed for trial would be conducted and a stream of solicitors, proposed witnesses, and relatives would come to aid prisoners in preparing their defenses. Visits after conviction, the correspondent adds, were probably strictly limited. Does the epithet black refer to the despondency of the prisoners or of those who made those visits?

My sources provide no answer to this question, but perhaps the next item has been explained convincingly. Not too long ago, some people used the simile as black as Newker’s (or Nook’s) knocker or simply as black as Newker. The identity of Newker puzzled people no less than that of Itchul. But this riddle has been solved: Newker is the stub of Newgate. This is what happens to long words! The place name Sevenoaks has become Snooks and bicycle has yielded bike. One never knows how to pronounce English place and proper names. Only naïve foreigners think that they can look at Magdalene (or Caius) College or Strachan and guess their pronunciation. However, the reference to the blackness of the famous knocker remains unaccounted for. Perhaps, after all, it was not as black as it was painted.

As black as soot or as black as itchul?

As black as soot or as black as itchul?Finally, there is as black as the Devil’s nutting bag. In discussing the phrase to hang out the broom (February 10, 2016), I noted that in this area we find ourselves at a crossroads between etymology and folklore. It is the custom that needs an explanation, for the phrase may then take care of itself. In 1777, John Brand brought out his deservedly famous book on popular antiquities. It has frequently been reprinted with additions and in different shapes. The story of the nutting bag can already be found there, along with the rhyme “Tomorrow is Holy-rood day,/ When all a nutting take their way.” Later, the custom connected with nutting on the 21st of September (though some informants gave the date as September 14) was discussed in Notes and Queries and elsewhere by those who had first-hand knowledge of it. The often repeated statement that the festival and the phrase have currency mainly or exclusively in Suffolk is wrong.

We know for certain that about the time when hazel nuts are ripe, the festival of Nutting Day was kept. In some places the celebration was accompanied by great disorder. The superstition has Christian overtones, though it probably has roots in pagan antiquity. Among other things, it is said that on that night the Devil met the Virgin, or that nutting is prohibited on Holy Cross Day (also called Hally Loo Day; Loo appears to be an alteration of Rood). Allegedly, the Devil used to wander in the woods on Nutting Day, and, judging by the saying, he had a bag of his own and did gather nuts. The allusion, at least in Berkshire and Somersetshire, was “to the devil’s use of a nuthook as a catchpole or bailiff (remember what is said about hooks and crooks in the June “gleanings”?), and to the necessarily sable hue of the devil’s appurtenance.” Perhaps so, though a hook is not a bag. The part that concerns me is “the necessarily sable hue of the bag.” Strangely, we again learn a lot of interesting things but the color of the Devil’s nutting bag is taken for granted (compare the story of the Newgate knocker). Why should the bag used on Nutting Day be different from the bag the Fiend carries on other occasions?

Bats are not particularly warm, are they?

Bats are not particularly warm, are they?  Owls are certainly not stupid. In Greek mythology, as is known, the owl served the goddess of wisdom.

Owls are certainly not stupid. In Greek mythology, as is known, the owl served the goddess of wisdom.

A look at similes shows that beside the absolutely transparent ones (for instance as plain as the nose on your face, as bright as day, or as black as night) some are totally incomprehensible. Consider as good as Portuguese devil, as sick as a landrail, and as ignorant as a carp. I have chosen those three because they are not listed in any book I’ve had the chance to consult, because neither rhyme nor alliteration justifies their existence, and because, as far as I can judge, the carp is not more ignorant than any other kind of fish. (Was the Portuguese simile coined in reference to some war and the second at the time of the first railways?) People enjoy adding the most incongruous words at the end of the as…as phrases. Some such sayings have been discussed with dubious results (for example, as sure as eggs is eggs). Others contain obvious irony. Among them is as white as a witch (witches are supposed to personify darkness). Many go back to the customs and occasions at present beyond reconstruction. Once their origins have been found, the researcher feels warm as a bat. On other occasion, the poor scholar feels and looks as stupid as an owl.

Image credits: (1) “Doorway” by bonoflex. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay. (2) “Dirt Patterns” by Monik Markus. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. (3) “Square-townsend-fledermaus” by Velho at English Wikipedia. CC ASA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (4) “Owl Bird” by Kaz. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Feature image credit: “Spooky Moon” by Ray Bodden. CC By 2.0 via Flickr.

The post As black as what? appeared first on OUPblog.

2016: the year of Zika

Zika virus (ZIKV), an arbovirus transmitted by mosquitoes of the Aedes genus, was first isolated in 1947 in the Zika forest of Uganda from a sentinel monkey. It has always been considered a minor pathogen. From its discovery until 2007 only 14 sporadic cases – all from Africa and Southeast Asia – had been detected. In 2007, however, a major outbreak occurred in Yap Island, Micronesia, with 73% of residents being infected.

The major breakthrough in the ZIKV story occurred in 2016 when it became clear that Brazil was facing the biggest epidemic ever of the virus. With a population of 210 million inhabitants and heavily infested by Aedes mosquitoes, the arrival of ZIKV in Brazil gave rise to a perfect storm.

Between October 2015 and 20 July 2016, Brazil reported 8,703 suspected cases of microcephaly and other nervous system disorders suggestive of congenital infection. Of these, 1,749 are confirmed cases of microcephaly, 277 of which are laboratory-confirmed for ZIKV infection. Now the problem seems to spread to other countries. As of 28 July 2016, 14 countries or territories have reported microcephaly and other central nervous system malformations associated with ZIKV infection.

As a possible related agent to the rise of microcephaly cases, ZIKV is now becoming associated to an even more complex congenital syndrome. It has been known for many years that some congenitally acquired viruses such as Cytomegalovirus (CMV) can cause microcephaly. Now it is becoming clear that ZIKV once acquired by pregnant mothers can give rise not only to microcephaly but also to a unique “ZIKV congenital syndrome”. This syndrome includes not only microcephaly but also a peculiar brain-imaging pattern, along with complex ocular abnormalities and arthrogryposis (congenital joint contractures).

Since its original description in 1916 by French neurologists, Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) has been associated with previous infections by a number of bacterial and viral agents. In GBS the body’s immune system attacks part of the peripheral nervous system by an autoimmune mechanism. GBS is clinically characterized by a rapidly evolving flaccid paralysis of legs and arms, sometimes associated with facial palsy, swallowing difficulties and respiratory arrest. This usually follows in days or weeks an acute infectious or, less frequently, non-infectious systemic event. GBS is considered a medical emergency due to the potential risk of respiratory insufficiency and generalized paralysis. Now, growing scientific evidences have linked previous ZIKV infection to GBS.

Zika Virus: Transmission electron microscope image of negative-stained, Fortaleza-strain Zika virus (red), isolated from a microcephaly case in Brazil. Image by NIAID. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Zika Virus: Transmission electron microscope image of negative-stained, Fortaleza-strain Zika virus (red), isolated from a microcephaly case in Brazil. Image by NIAID. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Since the emergence of the Brazilian epidemic, ZIKV has grown in status and has brought serious concerns about its capacity of rapid spread and to give rise to ominous neurological consequences. Many non-medical issues are involved in the present situation. For many years, ZIKV has been considered a vector-transmitted agent only. This view has been recently challenged by the possibility of human-to-human transmission (transplacental and sexual contact). This could allow the rapid spread of the infection even in places where Aedes mosquitoes are not endemic.

Brazil, the epicentre of ZIKV problem, is facing an unparalleled political, economical and social crisis. Besides, it is hosting the 2016 Olympic games. The published scientific literature is still growing but most information started to become available and rose in the lay press, which can sometimes be misleading and bring panic to the population.

The uncertainties about ZIKV and its neurological complications open a vast field for research in which only well performed clinical and epidemiological studies will demolish biased, hastened opinions. In a recent review scientists, critically assessed the current literature, trying to summarize what is scientifically known about the neurological complications of ZIKV.

Futures studies need to assess the efficacy of new proposed methods of vector control as well as the effectiveness of the routine use of condoms to prevent sexual transmission. In addition, better and rapid diagnostic tools should be pursued. Because there is no proven treatment for ZIKV, the development of new therapeutic approaches should be one of the priorities for future research. Any of the potential drugs to be tested must be safe for pregnant women. In addition, more knowledge is needed to understand how to best address newborn babies with severe and disabling congenital malformations, and maybe prevent the devastating congenital infection.

The public health and economic implications of the ZIKV outbreak cannot be minimized. The emergency of an epidemic of microcephaly is of great concern for countries with relatively high birth rates. Medical, economic, and psychological burdens suffered by families are worsened by the whole health system, which cannot adequately deal with all the short and long term requirements of the current situation. Also, ethical and social implications have to be taken into account, particularly in countries in which abortion is restricted to very specific situations or even totally prohibited. The consequences of a GBS outbreak are also worrying because it brings along an unbearable overload of both public and private health systems, which may not be able to respond quickly and efficiently to an increased population of patients needing continued hospitalization support and specific and expensive treatments.

In the heat of events one must be very careful to avoid hasty conclusions based solely on crude indications. The lack of solid and scientifically indisputable evidences may easily lead to wrong decisions.

Featured image credit: Mutirão de combate ao mosquito Aedes Aegypti no Grupamento de Fuzileiros Navais de Brasília (Joint effort to combat the Aedes Aegypti mosquito in Reverse Split Marine Brasilia) by Ministério da Defesa. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post 2016: the year of Zika appeared first on OUPblog.

10 things you didn’t know about Brazil’s economy

By the end of the twentieth century, Brazil had ranked as one of the the ten largest economies in the world, but also being that with the fifth largest population, it is facing many obstacles in economic growth. With the 2016 Rio Olympics now upon us, we’ve collated 10 interesting facts about Brazil’s economy, from colonial times to the modern day. Let us know what you think or share your own facts in the comments below.

Brazil has one of the world’s most unequal distributions of income. The richest 10% of the population get 47% of the income, while the poorest 10% get only 12% of the income. Around 20% of Brazilians live below the poverty line.

Sugar and cotton were Brazil’s main exports in the colonial era, and joining them in the nineteenth century were hides, rubber, and coffee.

By 1900, Brazil had accounted for more than one-half of the world’s coffee production, as late as the 1920s coffee still constituted 75% of Brazil’s exports.

Brazil experienced an abrupt transition to rapid economic growth at the start of the twentieth century. This was a result of several factors; the expansion of coffee ports giving Brazil the foreign exchange earnings to improve import productivity, investments in railroads, and the elimination of slavery making Brazil more appealing to European immigrants.

Coffee beans by yo_agullar. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Coffee beans by yo_agullar. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.Brazil is the largest and most populous country in South America, with 182 million inhabitants, by 2000 Brazil had become the world’s eighth largest economy.

The Amazon Basin to the north and west covers more than 40% of the country, and Brazil is home to a wealth of natural resources. It has around one-third of the world’s reserves of iron ore, as well as large deposits of bauxite, coal, zinc, gold, and tin.

Brazil makes up one of the BRIC countries along with Russia, India, and China. Their fast-growing economies are predicted to compete with the USA in global economic importance.

Brazil has a system of conditional cash transfers, which offers payments to around one-quarter of the population for attending health clinics and sending their children to school. This should help improve access to education and health services.

In 1565, Portuguese explorers laid the foundations for the city of Rio de Janeiro along the Atlantic shoreline. From the beginning the port activities, related to local sugar production, were based on slave labor and trade.

Between them, the USA and Brazil account for two thirds of the world’s production of oranges for export.

Featured image credit: Brazil_flag by gaby_bra. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post 10 things you didn’t know about Brazil’s economy appeared first on OUPblog.

Why Christmas should matter to us whether we are ‘religious’ or not

There are many aspects of Christmas that, on reflection, make little sense. We are supposed to be secular-minded, rational, and grown up in the way we apprehend the world around us. Richard Dawkins speaks for many when he draws a distinction between the “truth” of scientific discourse and the “falsehoods” perpetuated by religion which, as he tells us in The God Delusion, “teaches us that it is a virtue to be satisfied with not understanding” (Dawkins, 2006).

If this is so, then Christmas, with its extraordinary tales of virgin births and Santa Claus, should be a relic of a bygone age – a throwback perhaps to antiquity when the Church superimposed a Christian festival upon the pagan Saturnalia, Kalends, Yuletide or the Birthday of the Unconquered Sun. Certainly, this writer is not alone when he contends that “nowadays, Christmas is, for many of us, a holiday that has no religious significance at all,” on the grounds that when one celebrates “good will, generosity, and peace among nations” (Mercer, 2010) and when we adorn the festival with “Christmas trees, wreaths, coloured lights, candy canes, carols and Christmas music,” this does not “put us in mind of any values or doctrines specifically Christian or religious” (ibid.). So, on this reckoning, we pay merely lip service to Christmas as a religious festival. People may go to church, and there may be an abundance of values that would hardly be an anathema to Christians, such as showing kindness and charity to strangers. But, crucially, these need not be construed as religious per se.

Indeed, one of the greatest New Testament scholars of the last century, Rudolf Bultmann, would see eye to eye with Dawkins on the need to divest ourselves of any mythological accoutrements if we are to function and flourish in the modern world. For Bultmann, it was a major stumbling block to be beholden to a pre-scientific worldview: “nobody reckons with direct intervention by transcendent powers” because “modern man acknowledges as reality only such phenomena or events as are comprehensible within the framework of the rational order of the universe” (Bultmann NT&M, 1985). We cannot seriously embrace the latest technological and scientific capabilities – from iPads to IVF, from stem cell research to WiFi – while at the same time subscribing to an archaic cosmology which posits the existence of angels and demons.

No matter how consumerist and materialist the modern Christmas may be, we still find space for magic, typified by when we encourage our children to believe that Santa travels around the world on Christmas Eve delivering presents to every good boy and girl.

Yet no matter how obsolete the cosmology, the irony is that it is the “secular” film industry today which is so brazenly beholden to it. With its ready-made adornment of redeemer-figures by way of Santa and Scrooge, flying reindeer, magical elves and Lapland as a functional equivalent of the Christian heaven, Christmas movies, with their metaphysical and supernatural flights of fancy, suggest that we might not have moved on too far from the days of the New Testament. Christmas actively embraces the miraculous and the transcendental. No matter how consumerist and materialist the modern Christmas may be, we still find space for magic, typified by when we encourage our children to believe that Santa travels around the world on Christmas Eve delivering presents to every good boy and girl. And it is not just children who subscribe to this myth. Indeed, Alex Lester on Radio 2 in the early hours of Christmas morning in 2015 gave his listeners regular updates during the course of his “After Midnight” programme of where Santa was around the globe, even telling us around half past midnight that Santa had already delivered 4.1 million presents, and was presently seen heading from Iceland to Brazil. Canon Roger Royle, a stalwart of Radio 2’s “Pause for Thought” and “Sunday Half Hour,” even invited his listeners shortly before 5am to take a look out of the window and see if Santa had gone past yet. The BBC’s Asian Network was no exception, with British Asian Bhangra singer Danny Sarb, who presented a Christmas morning special, telling listeners that, when he was young, “I waited for Santa to come down the chimney” and joking that “I still remember I used to write Santa a letter every single year – and I still do sometimes, even though I’m 22.”

No matter how ingrained our assumptions may be that Christmas is a “secular” holiday, the reality is far more nuanced than that. Christmas may be one festival of the year which strongly polarizes people precisely because it is either seen as inescapably secular (due to its commercialized and consumerist pedigree) or as a quintessentially religious festival in view of its Christian origins. But any festival which can find authentic manifestations of wonder, miracles, sacrifice, fellowship, redemption and love because of, rather than in spite of the greed, the consumerist telos and the concomitant disenchantment, suggests that our categories of religion need to be reshaped and revisited. Maybe it is in and through the secular that we can find one of the greatest manifestations in the world today of a religious celebration.

Featured image credit: “Christmas bokeh” by Susanne Nilsson. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Why Christmas should matter to us whether we are ‘religious’ or not appeared first on OUPblog.

Blackstone’s Statutes 2016-2017: key legislation

In 2015, we asked some of our Blackstone’s Statutes series editors to select a piece of legislation from their subject area which had made a big impact; it resulted in an interesting selection so we decided to do the same thing this year. Discussed below are what our editors consider to be key pieces of legislation from their area of expertise. The main difference this time around has been that the UK has voted to leave the EU, which in turn has led to the future of some legislation being uncertain.

Nigel Foster: Traveller’s Rights

There are two sets of EU legislation which have had and might continue to have a very positive impact of the lives and rights of UK citizens who travel abroad. I’m not talking about those UK citizens who have taken advantage of the rights of free movement to live and work in another part of the EU, although the legislation does apply to them also, but those who travel temporarily be it on holiday, visiting family or on business.

First we have Regulation 261/2004 91 [OJ 2004 L46/1] dealing with air passenger’s rights, which provides that air carriers pay compensation when flights are delayed, passengers are denied boarding or flights are cancelled, all of which were in the past causes of huge concern, financial loss and for those holidaying with family, incredible disappointment. This legislation has been extended to rail (Regulation 1371/2007 (OJ 2007 L315)), ship (Regulation 1177/2010 (OJ 2010 L334/1)), and bus and coach (Regulation 181/2011 (OJ 2011 L55/1)) transport.

Then allied to the above is the so-called Roaming Directive (which is in fact now governed by a Regulation 531/2012 (OJ 2012 L172)), which has required mobile phone service providers to incrementally reduce roaming tariffs and as from 15 June 2017 removed entirely.

To put this in context as to how this impacts on the lives of UK residents, the Office of National Statistics (ONS) gave the figure of UK residents visits abroad in 2013 as 58.5 million visits (for all reasons) with holidays accounting for over 37 million visits. Most of those will be by air travel and almost certainly most will be with a mobile phone. The two pieces of legislation apply to protect and benefit the vast majority of those traveling. Now that the UK has voted to Brexit, these protections and benefits may change, and we could go back to the bad old days of no compensation for flight disruptions and extortionately high roaming tariffs.

P.S I claimed and have just received my €250 Compensation from Vueling Airline when they cancelled my flight to Zürich, so I know it works!

Nigel Foster is LLM Degree Programme Leader at Robert Kennedy College, Zürich and the editor of Blackstone’s EU Treaties & Legislation 2016-2017 .

Robert G. Lee: European Communities Act 1972

Last year when asked to contribute a blog piece, I chose to write about the European Communities Act 1972. I did so to explain some of the discontents that led to the proposal for a referendum on EU membership. Now that the referendum has been held with a vote to leave the EU, this year I would like to write about the European Communities Act 1972 – again!

One issue is whether the repeal of the Act will represent a final seal on the UK’s departure from the EU.

One might anticipate that this Act is now destined to be repealed. However, quite when and how it is repealed could be a matter of great constitutional significance. One issue is whether the repeal of the Act will represent a final seal on the UK’s departure from the EU and the first involvement of Parliament in the process of withdrawal. Some people argue that Parliament would need to sanction the very process of withdrawal under Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty.

You may have read that a law firm, Mischon de Reya, have threatened legal action if an attempt is made to give notice under Article 50 without Parliamentary approval. This is on the basis that under the EU Referendum Act 2015 (now included in the book), the referendum’s status is advisory and cannot bind Parliament, which could in principle refuse to act on the referendum vote. Since around two thirds of MPs were in the ‘remain’ camp at the time of the referendum, this may not seem so far-fetched.

The political reality is somewhat different, however, and a refusal to sanction notice under Article 50 could provoke a constitutional crisis. Moreover, in the absence of a written constitution formally ruling on the matter, it is perfectly possible to argue that the triggering of Article 50 could be achieved by the exercise of the royal prerogative without Parliamentary approval. Constitutionally the UK Parliament has no formal role in treaty-making, as the power to do so is vested in the executive. If one takes this view, Parliament may have to wait to express its view at the point at which legislative change is needed – and that may come with the repeal of the European Communities Act 1972.

Robert G. Lee is Professor of Law and Director of the Centre for Legal Education and Research at Birmingham Law School. He is editor of Blackstone’s Statutes on Public Law & Human Rights 2016-2017.

Meryl Thomas: The Commonhold and Leasehold Reform Act 2002

There is a trend amongst developers to build properties that are interdependent (for example, blocks of flats), particularly in large cities. Two issues arise. First, buildings are likely to have ‘common parts’, which are not owned by an individual flat owner, for example, lifts, and these areas must be properly maintained. Second, is the need to ensure that the mutual obligations (for example, not to keep pets) be enforced not only between the original parties, but between successors in title.

An owner of property may either have a freehold interest (the best title in English law), or a leasehold interest. Generally purchasers and lenders prefer the former to the latter. In properties of multiple freehold ownership problems arise. Although mutual promises can be enforced between the original purchaser and seller, it is far more difficult for these promises (particularly those of a positive nature) to be enforced between subsequent purchasers. This means that enforcing obligations of maintenance of common parts of the building, and positive obligations between individual owners is almost impossible. Flats therefore tend to be sold as leasehold units, in order to overcome these difficulties.

The introduction of the Commonhold and Leasehold Reform Act in 2002 was meant to overcome these issues, allowing property to be divided into a number of freehold units, each sold to a different owner, and a further freehold comprising all the common parts of the property, and vested in a corporate body (the commonhold association). The association will have responsibility for the common parts, and membership of such is limited to the unit owners, who, by means of the association, control the communal parts of the building. Moreover, mutually enforceable obligations are embodied in a commonhold community statement, providing a ‘local law’ enforceable by and between unit holders.

With only 20 commonhold registrations in 10 years since 2004, developers appear more willing to rely on pre-existing methods probably due to the fact that sale of the freehold of the entire block is a source of revenue for them.

Meryl Thomas is a lecturer at Truman Bodden Law School in the Cayman Islands, and the editor of Blackstone’s Statutes on Property Law 2016-2017 .

Matthew Dyson: The Offences Against the Person Act 1861

England and Wales is one of only a handful of jurisdictions among the economically developed countries of the world which is still without a Criminal Code. Even experts can struggle to find all the applicable legal rules, spread amongst hundreds of years of statutes and cases. Even other common law legal systems have codes, such as those in many Australian Jurisdictions and in New Zealand, or Model Codes, such as in the United States of America.

England might have developed a code, indeed, there were periods in the nineteenth century when it looked possible for English criminal law to be codified. Instead, lawyers decided to focus on improving accessibility by collating existing statutes, such as in the OAPA, the Malicious Damage Act and the Larceny Act; first in 1827/8 and then again in 1861. The OAPA still governs the core non-fatal offences against the person but its language is now somewhat antiquated and it no longer represents our attitude to certain harms (for instance, a pin-prick is a “wound” and thus theoretically still equivalent to “grievous bodily harm”).

The Law Commission has once more proposed significant reform of these offences, at last moving from consolidation of pre-1860s and 1820s law, to modern conceptions. This might then create another pocket of code-like rules, even if a comprehensive code is not achieved.

Since the 1830s there have been numerous attempts at a full Code, the most recent being 1989, all of which failed to get very far towards being promulgated. English criminal law is largely inaccessible and tweaked and changed annually. The best form of criminal law would be certain, clear, enduring and internally coherent: it is to be hoped another 150 years do not go by before English lawyers and politicians have the will to pass a full Criminal Code expressing these values.

Matthew Dyson is Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and the editor of Blackstone’s Statutes on Criminal Law 2016-2017 .

Featured image credit: Case-Law, Lady Justice, Justice by AJEL. CCO Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Blackstone’s Statutes 2016-2017: key legislation appeared first on OUPblog.

August 16, 2016

A curve in the road to a “Drug-Free America”

Tom Hedrick speaks with me in a sunlit suite of offices overlooking Park Avenue in Manhattan. A genial host, he recounts the early days of the Partnership for a Drug-Free America (PDFA), which he helped to found in the mid-1980s and where he still works. Wary of derailing the interview, I hesitate to ask about a controversy that, to some degree, still shadows the organization.

Virtually every American over 35 who had access to a television set in the waning years of the Reagan Administration is familiar with the PDFA’s handiwork. The frying pan with a sizzling egg stand-in for “your brain on drugs.” The stern, middle-aged father confronting his son over the boy’s pot stash, only to be told, “I learned it by watching you!”

These memorable spots resulted from an effort by advertising executives, artists, and copywriters to “unsell” some of the country’s most popular, though illegal, consumer products.

“You have to remember the environment in 1984 and ’85,” remarks Hedrick. “It was a period like no other.” Crack was spawning addiction and violent crime among its users while lawmakers cast accusing fingers at Hollywood for treating illegal drug use as harmless, even alluring. “We in the media were partly responsible for what was going on. So why couldn’t we also not just show one side, or glamorize the issue?” he explains. After all, “many of us worked on teen or young adult products. There was a lot of good professional experience we could bring to bear.”

And thus the operating model of the Partnership was born. Ad agencies proposed public service announcements (PSAs) for TV, radio, and print. A panel at the PDFA screened them, rejected many, and then sent finished work to participating media, which ran them free of charge. The Partnership steered clear of attacks on legal drugs for at least one obvious reason. A television station that relied on advertising from breweries, for example, might prove reluctant to provide airtime for a hard-hitting PSA on alcohol abuse.

Screenshot of the 1987 public service announcement “I Learned it by Watching You!” by Partnership for a Drug-Free America, used with permission.

Screenshot of the 1987 public service announcement “I Learned it by Watching You!” by Partnership for a Drug-Free America, used with permission.With much of the campaign relying on voluntary contributions—even Federal Express offered its services pro bono—costs were relatively low. Still, the Partnership’s directors needed to cover operating expenses. To help make ends meet, they struck something of a Faustian bargain, one best kept under wraps. But because the organization functioned as a nonprofit, the story became a matter of public record. All it took was an enterprising reporter willing to do some digging.

In a spring 1992 exposé in the Nation, Cynthia Cotts revealed that the PDFA’s supporters included several pharmaceutical companies, the maker of Jim Beam whiskey, Anheuser-Busch, and Philip Morris. Most damningly, R.J. Reynolds had been backing its calls for a “drug-free America” even as public health advocates condemned the company for hooking youngsters on cigarettes with its kid-friendly cartoon mascot, Joe Camel.

Cotts pulled no punches: “The war on drugs is a war on illegal drugs, and the partnership’s benefactors have a large stake in keeping it that way. They know that when schoolchildren learn that marijuana and crack are evil, they’re also learning that alcohol, tobacco, and pills are as American as apple pie.” Others were even harsher, and their criticism stung all the more because the Partnership appeared to be making real progress in shifting popular attitudes about illicit drugs.

At the time, Hedrick was unrepentant, claiming that he would have “taken money from the devil” to combat the scourge of crack. That implied comparison hardly flattered the organization’s heretofore silent partners, and it appeared inevitable that they would go their separate ways. Soon the PDFA pledged not to take alcohol and tobacco money, a position it notes prominently on its website today, though it openly acknowledges continued pharmaceutical support. For other reasons, directors also expanded the Partnership’s mission from persuading young people to abstain from drugs to reaching out to parents of children at risk. Now renamed the Partnership for Drug-Free Kids, the group addresses the dangers of licit as well as illicit drugs, with a focus on abuse of prescription medications. Decades of work earned Hedrick recognition from the White House earlier this year.

When schoolchildren learn that marijuana and crack are evil, they’re also learning that alcohol, tobacco, and pills are as American as apple pie.

I finally broached the topic. Had the passage of time changed his perspective on the funding question? “Maybe from a public relations point of view that was a stupid thing to do. I can understand why there was so much criticism.”

Not quite an admission of error, but perhaps understandable in light of how charges by the Partnership’s most vociferous critics—who portrayed it as little more than a front for Big Tobacco out to brainwash unsuspecting young people—distorted the efforts of its professional, generally earnest staff.

The closest analogue to “unselling” drugs may be unselling candidates for office. And as leading scholars in political science have argued, attack ads are not especially useful for implanting negative perceptions where none exist; they work when they tap into pre-existing attitudes or beliefs and then amplify, exploit, or redirect them. That is why their creators spend so much time and money researching, and trying to intuit, the attitudes of their audience. The most compelling, or notorious, of such ads was Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 “Daisy,” which featured a freckle-faced preschooler obliterated in a nuclear explosion. There was no need even to mention Barry Goldwater’s name because many viewers already had an impression that LBJ’s Republican opponent was trigger-happy.

Likewise, in the late 1980s, advertisers with the Partnership did not really convince viewers to divide, as it were, the sheep from the goats, culturally acceptable, legal drugs from apparently dangerous and illegal ones like cocaine. They did not conjure up ambivalence about employing chemicals to alter people’s moods or consciousness. They did not have to.

They learned that by watching us.

Featured image credit: Cigarette smoke by Ralf Kunze. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post A curve in the road to a “Drug-Free America” appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers