Oxford University Press's Blog, page 476

August 16, 2016

R.J.P. Williams and the advantages of thinking like a chemist

Powell’s City of Books occupies 1.6 acres of retail floor space in downtown Portland, Oregon and is one of my favorite places in the world. My first time there, I searched out the chemistry shelves–and was slightly disappointed. I counted two cases of chemistry books sandwiched between biology and physics, which had eight cases each.

I’m a chemist, so my perspective is decidedly biased, but, still, this puzzles me. In the Periodic Table of Elements, the entire universe is represented and ordered, stacked up like so many books. Chemistry has carved its own niche in the collective psyche of the popular culture. The stories of Breaking Bad and Big Hero 6 depend on powerful chemists, and chemical symbols and structures decorate ads and T-shirts.

But chemistry also entails “chemophobia.” Ever since the days of the secretive, mystical, and decidedly unsuccessful alchemists, my discipline has evoked some suspicion (after all, chemicals can be noxious and/or toxic). Even the great philosopher Immanuel Kant, in his preface to Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science, wrote that chemistry “doesn’t strictly count as a ‘science’, and would be better referred to as a systematic art.”

In the past few decades, a group of philosophers have taken issue with Kant’s assertion and have established a specific philosophy of chemistry. They argue that chemistry presents a coherent way of looking at the world that is distinct in philosophy and practice–and that chemists can see aspects of the world that are overlooked by biologists or physicists.

Image Credit: Bio Lab by Amy. CC BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Image Credit: Bio Lab by Amy. CC BY-2.0 via Flickr.The life of Oxford chemist R.J.P. (“Bob”) Williams (1926-2015) shows how the world benefited from a uniquely chemical viewpoint. Williams started his chemical career early, as an inorganic chemist. (Organic chemists study carbon, while inorganic chemists study metals.) As an undergraduate, Williams researched how transition metals bind non-metals. His work formed the basis for the Irving-Williams series, which I learned as an undergraduate in my inorganic chemistry class. Therefore, as an undergraduate, Williams discovered chemistry that is now taught to other undergraduates.

Williams remained an inorganic chemist at heart, and co-wrote an influential inorganic textbook in the 1960s. However, he soon saw how inorganic chemistry influences other areas, such as the chemistry of living things. His writings helped found the field of “Bio-Inorganic Chemistry.” This may sound like a contradiction in terms, but it’s not. The fields of biochemistry and inorganic chemistry synergistically provide insight into how life works in the present and evolved in the past.

In my biochemistry class, I teach no fewer than four crucial stories in this field that Williams developed from his chemical perspective:

Williams helped Max Perutz figure out how iron in the context of hemoglobin chemically binds oxygen in the lungs and releases it in the tissues, because iron adopts chemically unusual spin states.

Williams collaborated with Bert Vallee to determine how zinc in the context of particular enzymes cuts other proteins or metabolizes alcohol.

In a discussions with Peter Mitchell, Williams helped Mitchell work out that mitochondria store their energy in a protein gradient rather than as a covalently bound intermediate, solving a chemical mystery that stymied the field for decades.

In collaboration with the Oxford Enzyme Group, Williams applied the chemical instrumentation of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) to find the structure of complex protein molecules.

Each of these springs from a distinctly chemical insight. Despite having a hand in all of these fundamental discoveries, Williams is not mentioned in the biochemistry text I use. His collaborative spirit allowed others to take the spotlight. Following a recent ACS Symposium titled “The Posthumous Nobel Prize in Chemistry: Correcting the Oversights and Errors of the Nobel Prize Committee,” R.J.P. Williams was mentioned on the short list of scientists who should have won the Nobel Prize but didn’t.

For all of these accomplishments, I find the last two decades of William’s writing to be the most intellectually provocative. Williams co-wrote several books including The Natural Selection of the Chemical Elements (1996), The Chemistry of Evolution (2006), and Evolution’s Destiny (2012). These combine inorganic chemistry with biological evolution to describe a logical chemical sequence that the planet underwent as oxygen was released into the atmosphere over billions of years. As a result, different parts of the periodic table were available to life three billion years ago than are available today, making different chemical structures and causing different reactions.

Williams showed great skill in combining chemistry with biology to tell the story of natural history on a geological time scale. For example, he gave chemical reasons why life uses phosphate to store information in DNA, why life collects magnesium to help stabilize that phosphate, why it must reject calcium to avoid solidifying that phosphate, and why it also must accept potassium and reject sodium to maintain osmotic balance. In Williams’s story, calcium, potassium, and sodium are later used for specific jobs in nerve signaling that are based on their chemistry in water. As a result, the nerves that are firing in your brain as you read this are using these elements in a way that Williams justified using the periodic table.

Williams wrote down most of this story before genomic data became widely available in the first decade of the 21st century. After that data was analyzed, multiple research groups confirmed that the broad outlines of this story are indeed encoded in the DNA of the biosphere. Using his chemical intuition, Williams made predictions and told a story that was later confirmed by multiple lines of evidence.

In conclusion, we can file books onto specific shelves and classify them in multiple ways, but the world does not recognize our disciplinary boundaries. The career of R.J.P. Williams shows how a dedication to one area of chemistry can benefit fields as distant as evolutionary biology. When a chemist looks at a flower or a mountain, she will also see the atomic structures hidden deep within each, and that specific perspective enriches the others.

Featured image credit: Bookshelf by Matl. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post R.J.P. Williams and the advantages of thinking like a chemist appeared first on OUPblog.

Bloody Olympics: Rio, 2016, and the history of illegal blood doping

Throughout history blood has been imbued with magical properties. Drinking blood was viewed as a source of power for many mythical beasts, centuries before the invention of the modern vampire myth. In Greek mythology Odysseus can revive the dead by giving them blood to drink. But all blood is not the same – the blood from the veins on the left side of the snake-headed Gorgon Medusa is deadly, that from the right side is life-giving. In 1489 the Italian philosopher Marsilio Ficino, proposed that drinking the blood of healthy young men could rejuvenate the sick and elderly. Indeed it seems that an attempt was made to cure Pope Innocent VIII of his stroke by giving him blood from three ten-year-old boys. More dramatically, in the late sixteenth century the Hungarian princess and serial killer, Countess Elizabeth of Bathory, was alleged to have drained all the blood from over 600 young girls to feed her restorative blood baths.

Even in the post-enlightenment age, the first blood transfusions had nothing to do with the modern notion of enhancing oxygen supply; instead they were supposed to heal by replacing old bad blood with strong healthy animal blood.

Sport has long had a fascination with blood. The blood of the Roman gladiators, mopped by a sponge from the arena, fed a profitable business; perhaps the athlete’s ultimate commitment to promoting their brand? Today blood is even more relevant to sport. Indeed arguably its use and abuse in sport today has come close to destroying the Olympic movement.

The modern fascination with blood in the Olympics arose from the new discipline of sports science in the 1960s and 1970s. A key driver was the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, where physiologists recognized the difficulty of getting sufficient oxygen to tissue in the rarefied 2km high air. Red blood cells transfusions increase the amount of oxygen given to people suffering from trauma or anaemia. It was therefore argued that healthy athletes could be given ‘excess’ blood to increase their ability to deliver oxygen to tissue, and hence – it was hoped – enhance their performance in endurance sport.

Punto de apoyo / Supporting point by Hernán Piñera. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Punto de apoyo / Supporting point by Hernán Piñera. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.Scandinavian scientists were first to prove this. In 1972, Björn Ekblom at the Institute of Physiology of Performance in Stockholm, showed a 25% increase in stamina after a transfusion. It was subsequently alleged that Scandinavian athletes were putting this laboratory method into practice. Lasse Viren won double gold medals on the track in 5,000m and 10,000m at the 1972 and 1976 Olympics. Unproven allegations of blood doping dogged Viren, who always denied them, claiming that altitude training and ‘reindeer milk’ were the keys to his enhanced performance. Some of his teammates did later confess to blood doping, however, most notably Kaarlo Maaninka at the 1980 Olympics. Maaninka received no sanction, which may seem very surprising given that blood doping is one of the main reasons we will not see the Russian track and field team competing at the 2016 Olympics. However, although in the 1970s and 1980s blood doping was viewed as morally dubious, it did not break any rules. The anti doping effort of the time focussed more on amphetamines and anabolic steroids.

This would change in the 1980s. The LA Olympics in 1984 was the watershed event. There was extensive use of blood transfusions, including by several members of the highly successful US cycling team. Again no rules were broken, but the IOC had had enough and banned blood doping in 1985. However, they had no way of testing for this form of cheating, and it is fair to assume that it continued in secret. In fact the ready availability of genetically engineered EPO in the late 1990s, a difficult to detect drug that increases the number of red blood cells more gradually and naturally than a blood transfusion, undoubtedly increased the use of banned methods.

So where are we now? Blood is a part of the Olympics and always will be. Whilst not imbuing you with the mythical life giving properties of Odysseus, optimizing your number of red blood cells is a key part of success in endurance events.

I can guarantee that every medal winner in a long distance endurance event will have had their blood measured frequently by support scientists to conform the success of their training program, whether that program uses methods that are permitted (altitude training, sleeping in low oxygen tents) or banned (EPO, blood transfusion).

So much for Rio, what about Pyeong Chang and the Winter Olympics? This is, if anything, an even richer source of stories than the summer games. There are claims of athletes chosen for ski teams solely so that are the right blood group to donate blood to their team leader; in 2006 a disgraced ex-Austrian ski coach crashed his car into a roadblock in the Italian alps, whilst attempting to escape the police. But that’s a blog post for two years’ time….

Featured image credit: blood tubes by keepingtime_ca. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Bloody Olympics: Rio, 2016, and the history of illegal blood doping appeared first on OUPblog.

Breath: the gateway to expressivity in movement

One thing is constant from the moment we enter this world as humans until the day we leave.

We breathe.

We breathe automatically and unconsciously.

We also breathe in intricate and sophisticated ways. For example, singers, horn players, actors, and athletes often train in breathing patterns to improve technique. Breath training is a useful strategy to enhance both musicality and performance.

In many forms of dance the breath support for movement is not an integral part of training. It is not perceived to be important in the same manner that stretching, strengthening, and balance warrant focus. Little coaching and training time addresses breath support in most Western dance forms. We propose breath support is at the heart of expressivity and artistry in movement phrasing.

Teachers may verbally coach students to hold the abdomen in so tightly the action impedes optimal performance. A traditional verbal cue often used in ballet training asks students to ‘pull up’ or ‘pull in’ the abdomen to gain motor control. These are useful verbal cues if the student does not overdo the instruction. If the dancer overexerts in this command, the action actually impedes movement, impairs breathing, and reduces efficiency of action. Recent research delves into the role of breath and motor learning in acquiring ballet ‘skills.’ Over exertion of abdominal support muscles does not ensure efficacy in movement. To the contrary, it can elicit unnecessary stiffness and tension that can impede range of motion and fluidity of action.

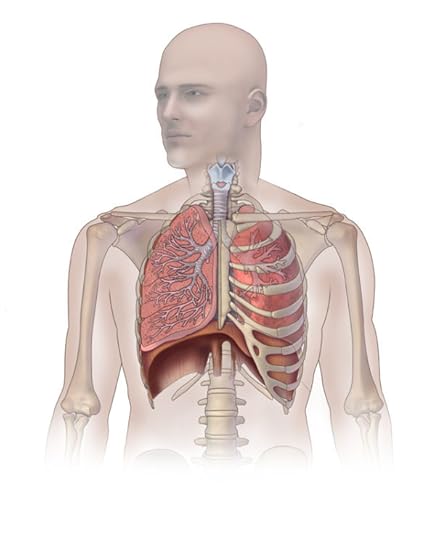

Deepening an understanding of the relationship between the muscular support for breathing and central support can help a student discover the necessary recruitment needed to support the pelvis and lower back for stability while maintaining mobility in the breathing apparatus. The diaphragm, seen in the image provided, is a primary muscle involved in the breathing process. It is responsible for approximately 75% of the action of breathing (Calais-Gemain, 2006). Similar to other muscles it can be chronically tight or have a limited range of motion Dancers spend many hours stretching the hamstrings and other leg muscles, but think little about this important muscle that has myofascial connection from the pelvic floor to the floor of the mouth.

Dana, a colleague and professional dancer with whom we have worked, began her interest in dance during college. Prior to discovering dance she was a synchronized swimmer. This involves swimming in formations and often holding the breath for long periods of time. As she trained more intensely to prepare for a professional dance career, her teachers asked her to stop swimming. Within one year the circumference of her ribcage when measured around the chest reduced from 38in to 36in— a difference of two full inches! The muscles of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles between the ribs no longer maintained the capacity to stretch as far. The muscles of breathing require attention for resiliency of action just as the muscles of the leg require both strength and stretch activity to enable expressive movement.

The lungs are located in the thoracic cage superiorly above the first rib and inferiorly between rib 5 and 7 with the diaphragm muscle situated below the lungs. Photo by Caitlin Duckwall.

The lungs are located in the thoracic cage superiorly above the first rib and inferiorly between rib 5 and 7 with the diaphragm muscle situated below the lungs. Photo by Caitlin Duckwall.Try this movement exploration:

Quietly notice your breathing.

How long is your inhale? How long is your exhale? Use a personal counting system to create a relative measure of time. Breathe in as fully as possible expanding your torso.

Now, hold that breath for a slow count of 8. While holding the breath, let go of unnecessary tension your body. Check in with your neck, jaw, fingers, shoulders, and lower back.

Exhale for a slow count of 6.

Repeat this several process times.

Return to breathing in a natural way without any particular expectation. In what way has the breathing pattern changed?

Breath is both autonomic and muscularly controlled. As we have musculoskeletal habits such as standing on one leg more than another or chewing more often on one side of the mouth, we also have unconscious habits for breathing. Training the breathing mechanism should be as important as training the legs and core. Exploring functional principles for respiratory action in relation to breathing habit provides new possibilities to improve respiratory function, reduce excess tension and stress, and improve expressivity in movement. Employing breathing practices within dance training can shift the breathing mechanism for the student and improve performance.

Breathing, emotions and movement are normally strongly interwoven, with each influencing the others. Young dancers often hold their breath, interfering with their movement’s integrity and precluding expressivity. In a sensory context, exploring various relationships between breathing and moving may enhance expressive potential and release physical and psychological tension (Brodie and Lobel, 2012).

The breathing mechanism supports neuromuscular stamina and cardiovascular health. In the dance studio, conscious use of breathing patterns can enhance the phrasing and expressivity in movement. Beyond the dance studio, conscious awareness of breathing function can enhance our choices for creating ease in daily life, to release unnecessary tension, and restore the body towards balance.

Featured image: “Lungs and the Diaphragm Muscle” by Functional Awareness illustrator Caitlin Duckwall.

The post Breath: the gateway to expressivity in movement appeared first on OUPblog.

Why did the Oxford University Press staff member cross the road?

In order to celebrate National Tell a Joke Day, we asked fellow Oxford University Press staff members to tell us their favourite joke(s). Some of these jokes will make you guffaw and some will make you groan but hopefully all of them will make you smile. The jokes below range from the strange to the downright silly – we hope you enjoy them!

Simon Thomas is a Content Marketing Executive for Oxford Dictionaries, and shared a joke his brother made up:

What’s the difference between a window cleaner who’s scared of heights and this joke?

The window cleaner only works on one level.

———-

Hannah Charters is an Associate Marketing Manager for the Institutional Marketing team and enjoys this simple, straight-forward joke:

Why was 6 afraid of 7?

Because 7 8 9 (say it out loud)

———-

Unfortunately, Amy Jelf recently left OUP but, before she left, she shared this cheese-based joke with us:

Which cheese is made backwards?

Edam

———-

Ged Welford is a Library Sales Manager, and impressively kept both of his jokes ‘on-location’:

This man walked up to me and said “I’m gonna cut the bottom of your trousers off and put them in the library”

I said “Right. That’ll be a turn-up for the books.”

And…

A man walks up to the library desk and says: “I’ll have fish and chips with a chicken pie please!”

The librarian at the desk says: “You do know that this is a library?”

The man whispers very quietly: “Oops, so sorry. Fish and chips with a chicken pie please.”

———-

Alice Graves is an Assistant Marketing Manager for the Institutional Marketing team, and always laughs at this joke:

Two fish are in a tank.

One says to the other: “How do you drive this thing?”

———-

Katie Stileman is a Junior Publicist, and only finds jokes funny if they are not actually funny:

How do you confuse a lexicographer?

Paint yourself green and throw forks at them.

———-

Tracey Rimmel recently joined OUP as a Group Communications Assistant, and shared the following jokes with us:

Why did the scarecrow win an award?

He was outstanding in his field.

And…

The Dalai Lama walks into a pizzeria and says:

“Can you make me one with everything?”

And…

A termite walks into a bar and asks:

“Is the bar tender here?”

———-

John Kay is a Group Internal Communications Manager, and made us smile with this joke:

Who’s the star of Groundhog Day?

Bill Murray

Who’s the star of Groundhog Day?

Bill Murray

Who’s the star of Groundhog Day?

Bill Murray

Who’s the star of Groundhog Day?

Bill Murray

———-

Isabel Thompson is a Marketing Research Analyst, and told us this joke (with voices too):

A snail gets mugged by a tortoise.

Afterwards, a policeman asks “So sir, can you tell me what happened?”

The snail looks bewildered and says “Oh, er, I don’t know! It all happened so fast!”

———-

Ella Percival is a Communications Manager for GAB Marketing Services, and tragically finds this joke funny (every single time):

What do you call a French man in sandals?

Phillipe Phollope

———-

Jack Campbell-Smith is a Multimedia Producer, and made us laugh with this:

It’s hard to explain puns to kleptomaniacs because they always take things literally.

———-

And I’ll leave you with the following:

I went to dance at a sea-food disco last night.

Pulled a mussel.

———-

Featured image credit: ‘Time-money-laughing businessmen’. By Alexas_fotos. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Why did the Oxford University Press staff member cross the road? appeared first on OUPblog.

August 15, 2016

What a difference a decade makes in Brazil

Ten years ago Brazil was beginning to enjoy the financial boom from China’s growing appetite for commodities and raw materials. The two countries were a natural fit. Brazil had what Beijing needed – iron ore, beef, soybeans, etc. and China had what Brasilia desperately wanted – foreign exchange to address budget deficits and cost overruns on major infrastructure projects. It was a marriage made in heaven – for four or five years. Then the financial crisis exploded in 2008-2009, demand in China dropped, and Brazil did not have alternative markets. Indeed, the emphasis on commodity and raw materials exports had a negative impact on industrial activity.

There was an important window in the mid-2000s for the government of President Lula da Silva. The emerging budget surpluses could – should – have been used for long overdue investments in pollution and environmental controls, an extension of the metro, hotels, and well trained personnel to deal with the “God is a Brazilian moment” – Brazil won the bid for the World Cup Finals in 2014 and for the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro in 2016.

The Soccer finals were relatively successful save for the fact that the country is now saddled with very expensive, underused stadiums in many remote regions of the country. The cost overruns were of concern as well. But God being a Brazilian, the World Cup was then, this is now. And the very important difference is that the Olympics would be concentrated in Rio de Janeiro, and not across Brazil. But we discovered that the traditional Brazilian “wishful thinking” kicked in. Yes, we need to extend the metro to Barra, the area in which most of the activities will be played, but…. Indeed, the decade’s old hope of cleaning up Guanabara Bay and the lake in the middle of the city, to prepare for the boating and swimming events, remained elusive. There was confusion over jurisdiction – municipal, state, or federal?

Brazil patriot flag by luni39. Public domain via Pixabay.

Brazil patriot flag by luni39. Public domain via Pixabay.Brazil became distracted by the massive corruption scandal that laid low the state oil company, Petrobras. Accusations of bribes, kick-backs, and related shenanigans emerged in force. The recently re-elected President, Dilma Rousseff, was in danger of being impeached, and was suspended from office while the process meandered through Congress. Unemployment and inflation were up; investment was down. Trade was lackluster. Most of the major construction companies were involved and that slowed much of the infrastructure work needed to make the Olympics a success.

In 2016 crime and gang violence increased. Security issues were suddenly a priority. State and municipal authorities were bankrupt. There was no money for gasoline for police cars. Salaries were delayed. A jihadist threat emerged. Some of the new infrastructure collapsed – shoddy engineering or bad luck? Ticket sales to the various Olympic venues were mediocre. Public opinion polls indicated that many Brazilians did not favor the Games at all.

There was much discussion of whether or not international games actually benefitted the host country. The hidden costs could be enormous, specialists argued. In the middle of a major financial crisis, did Brazil need to spend as much for what is viewed as a middle-upper middle-class activity – in contrast to the Soccer finals that were wildly enthusiastic with the average Brazilian? Soccer was not called “o jogo bonito” (the beautiful game) for nothing.

A week or so before the opening of the Games, it was announced that the metro to Barra should be functional, more or less. Then it emerged that international teams arriving for the Games would not accept their assigned housing in the Olympic village. The Australians, and others, complained that the toilets did not flush, ventilation was poor, and poor construction offered other hazards. The Mayor of Rio, in an intemperate moment, said that he might place a kangaroo in front the of the Australians hotel. The Olympic authorities rushed to correct the deficiencies but the publicity was negative and widespread. What had gone wrong? Hubris, perhaps. Was President Lula overly confident that the country could make the needed investments to host two world sporting events? Did the spreading corruption scandals sap the planning dynamics needed to meet the challenges?

In hindsight the 2015 Soccer finals were fine even though Brazil did poorly on the field. Incredibly proud of their Soccer prowess over the decades, the lackluster performance of the national team did not lift the spirits of the Brazilian public. It now remains to be seen if “muddle through” will again characterize the Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro. And, for the foreseeable future, it does not appear that Brazil will be bidding for any other international sporting events.

Featured image credit: Christ the Redeemer by danilarrifotografia0. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post What a difference a decade makes in Brazil appeared first on OUPblog.

Brexit and the quest for identity

Finding a basis for commonality and social identification is one of the greatest challenges of the 21st century. From Britain to the United States, France to Australia, Western states are struggling with an identity crisis: how to cultivate a common cultural ‘core’, a social ‘bond’, which goes beyond the global economy and political liberalism. It is too early to predict whether Brexit is the last gasp of the old structure of national identity, or its revival. Some of the key factors involved in this quest for identity are Brexit and Britishness, the challenge of migration, the European Union, and Brexit and the Nation-State.

Brexit and Britishness

The debate over the meaning of being British has been a central feature in British politics over the last decade. Back in 2005, in order to promote attachment to British values, the Home Office introduced a ‘Life in the UK’ citizenship test, which every person wishing to settle in the UK must pass. Three years later, in 2008, a government committee found that there had been a diminution in British identity; in order to foster community cohesion, it proposed an American-style pledge of allegiance to be recited in public schools. In 2014, following the ‘Trojan Horse affair’ in Birmingham, then–Prime Minister David Cameron pledged to promote belief in British values as a core curriculum component in every school. In 2015, the House of Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee held a public competition in order to find a preamble for a written UK Constitution; preambles, it stated, can foster community cohesion and express shared values.

A citizenship test, a loyalty oath, a core curriculum, a preamble—they all seek to construct a unique character to be shared and celebrated. But it is still difficult to specify what it means to have a British identity, or how legitimate it is to impose it on newcomers. Britain resembles a nation in search of a meaning, and Brexit is just another step in the journey in search of an identity.

The Challenge of Migration

Massive population movements to and within Europe are seen as the biggest challenge to the self-image of European democracies. Mass migration has inflamed cultural anxiety. The fear of the ‘Other’ was a central reason for Brexit (public polls show that two main reasons were migration and sovereignty). The influx of refugees and migrants, together with the rise of multiculturalism and minority rights, has challenged the democratic assumption that the majority group ‘can take care of itself’. Majority groups in Europe have become smaller in size—numbers matter, especially in a democracy!—and their culture has become more ‘needy’.

Massive population movements to and within Europe are seen as the biggest challenge to the self-image of European democracies

The EU has done little to address the challenge of migration. The lack of a clear EU immigration policy leads to a situation where a person wishing to become British can be naturalized in a more permissive state, for instance Sweden—or even ‘buy’ citizenship that is offered ‘for sale’ in Europe—and then relocate to a state with a stricter regime, for instance Britain. This creates a sort of ‘forum shopping’ where a person can choose the state with the most lenient requirements.

The European Union

National identity is challenged in Europe for another reason—the EU. The concept of Union citizenship was not seen as revolutionary in the early years of the Union. With the establishment of Union citizenship by the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, most people saw EU citizenship as a minimalist concept intended to facilitate labour mobility and promote economic interests; the EU, however, has blossomed to be a supranational form of government. It has adopted Directives that have turned national citizenship into a weaker concept; the distinction between Union citizens and long-term residents has become thin. European courts, too, have narrowed the power of Member States on nationality issues. The submission of nationality policies for the approval of justices in Strasbourg was not foreseen.

The Europeanization of Member States acts, unintentionally, as a burial of the nation-state, and triggers a new form of nationalism—majority nationalism. Brexit is a ‘Yes-vote’ for the nation-state. It is a form of ‘cultural defense policy’ intended to guard Britain from what some people see as a consistent erosion of its national culture and sovereignty. That’s the greatest challenge of the European Union—how to balance EU jurisdiction and the sovereignty of Member States to preserve the core of their constitutional identity. In at least four EU states there is a majority to leave the Union; this majority is not necessarily against the European Union but, rather, for the nation-state and the idea of self-determination.

Brexit and the Nation-State

Brexit poses a challenge to the West—can it be both open and global and, at the same time, keep a national ‘core’ that distinguishes the ‘here’ from the ‘there’? In a deeper sense, Brexit invites us to observe the fundamental changes that concepts of sovereignty, self-determination, and the nation-state are currently undergoing.

Globalization, Europeanization, and immigration are not bogeymen, but neither is national identity. Without a national ‘centre’, societies are becoming more divided than ever, drifting, and falling apart. The Treaty of Lisbon has adopted a clause that provides that “The Union shall respect the equality of Member States before the Treaties as well as their national identities, inherent in their fundamental structures, political and constitutional” (article 4(2)). Brexit is a call to the EU (and to national governments) to find ways to implement this clause.

Featured image credit: ‘European Union Flags 2’. Photo by Thijs ter Haar. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Brexit and the quest for identity appeared first on OUPblog.

August 14, 2016

What makes a good campaign slogan?

Slogan-wise, this year’s presidential campaign gives us Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” and Hillary Clinton’s “Stronger Together,” “Fighting for us,” and “I’m with Her.” Trump’s slogan is a call to bring something back from the past. Clinton’s are statements of solidarity. Phonetically, “Make America Great Again” has a characteristic sound shape, with its repeated m’s, k’s and g’s. “Stronger together” and “Fighting for us” likewise repeats sounds for phonetic unity. Both Trump and Clinton assert values—greatness in one case, and strength and fight in the other. By the wayside now are “Feel The Bern,” “TrustTed,” “Telling it like it is,” and more.

Campaign slogans, whether official or unofficial, have some recurring linguistic themes and devices. References to greatness, strength, peace, prosperity, progress, pride, and personality often play a role. The unofficial slogans that appear on signs, stickers and buttons often to poke at the other side. And poetic wordplay is often central, with repetition, rhyme, and parallelism all having roles.

“I’m with Her” evokes memory of the three-word campaign slogan “I like Ike,” from Dwight Eisenhower’s 1952 campaign. In a famous lecture on the poetic function of language, the linguist Roman Jakobson once analyzed “I like Ike.” The repetition of vowel sounds (the techniques known as assonance) made the slogan memorable, Jakobson said. The long i vowel (phonetically the diphthong /ay/) is repeated and framed by the consonants in a way which suggests, as Jakobson put it “the loving subject enveloped by the beloved object.” The “I” and the “Ike” are both present in the “like” adding to the intensity of the slogan.

Rhyme and the repetition of beginning consonants (alliteration) can be found in slogans as long ago as the election of 1840, with the slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too.” That slogan actually came from a campaign song which referred to William Henry Harrison’s famous victory at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811. Harrison caught pneumonia and died just a month after taking office and “Tyler Too” became the first vice-president to succeed to the presidency on the death of the incumbent.

“Make America Great Again hat” by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

“Make America Great Again hat” by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.We find alliteration in the 1844 “Fifty-four Forty or Fight,” which referred to James K. Polk’s call to expand U.S. control to the northern boundary of the Oregon Territory at 54 degrees, 40 minutes. And as we march through history, we find “Rejuvenated Republicanism,” “Patriotism, Protection, and Prosperity,” “Putting People First,” “Prosperity and Progress,” and “Reformer with Results” (you can check out the years and candidates at the end of the post).

Some slogans have more complex parallelism like “We Polked you in ’44, We shall Pierce you in ’52,” or “Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Speech, Free Men, and Fremont” from John C. Fremont’s 1856 campaign. Then there is Herbert Hoover’s 1928 “A Chicken in Every Pot and a Car in Every Garage.” Hoover also used the less remembered “Who but Hoover?”, with its rhyme play on “Who” and “Hoo” and “Who but” and “Herbert,” following in the spirit of the 1924 slogan “Keep Cool with Coolidge.”

Slogans can focus on a candidate’s presumed virtues: in 1996 Bob Dole tried “The Better Man for a Better America,” in 2004 John Forbes Kerry had “We Need Another JFK,” and in 2008 John McCain offered “Best Prepared to Lead on Day One.” Political attacks can be reinforced with alliteration or rhyme as in the 1884 campaign. That year saw a tit-for-tat between James G. Blaine and Grover Cleveland. Blaine’s attack “Ma, Ma, Where’s my Pa” referred to Cleveland’s supposedly having an illegitimate child. Cleveland’s side responded with the haiku “Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine, The Continental Liar from the State of Maine.” In 1964, Lyndon Johnson’s campaign addressed fears of his opponent Barry Goldwater with “The Stakes are too High for You to Stay at Home.” Johnson supporters also responded to Goldwater’s slogan “In Your Heart, You Know He’s Right,” with the rhyme “In Your Guts, You Know He’s Nuts.”

Some elections are about fears, and some are about the future. Post-war destiny was apparent in the 1960 slogans, where John F. Kennedy used “A Time for Greatness” and Richard Nixon tried “For the Future.” In other elections, voters are called upon to make something happen. In 2008, Barack Obama’s slogans were “Change” and “Change You Can Believe In.” In 2012, the fact of incumbency made “Change” no longer quite the right message to voters, so the slogan was “Forward,” since “Change.” Similarly, Ronald Reagan’s slogans in 1980 were “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” and “Let’s Make America Great Again.” Reagan’s re-election slogan took credit with “It’s Morning Again in America.”

Sometimes, though, incumbents find it hard to give up a good slogan. Dwight Eisenhower’s 1956 campaign used “I still like Ike.” It wasn’t as good phonetically, but it still beat Adlai Stevenson’s “We Need Adlai Badly.”

So as you watch the campaigns play out, enjoy the wordplay while it lasts. As Mario Cuomo once explained: “You campaign in poetry, you govern in prose.”

Key to the alliterative slogans: “Rejuvenated Republicanism” is from Benjamin Harrison’s (William Henry’s grandson) 1888 campaign, “Patriotism, Protection, and Prosperity” is from William McKinley in 1986,” “Putting People First,” is from Bill Clinton in 1992, “Prosperity and Progress,” and “Reformer with Results” are from Al Gore and George W. Bush in 2000).

Featured image credit: “Hillary Clinton” by Nathania Johnson. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What makes a good campaign slogan? appeared first on OUPblog.

Olympian pressure

The four-year Olympic cycle seems to come around with increasing regularity as I get older. As a consultant psychiatrist and advisor to a number of national sports organisations on mental health – I am fascinated every time. Each Olympic Games brings new hope and new challenges for all competitors and their supporters. Among those supporters will be family, friends, team-mates, and coaches, and a wide range of other disciplines – all helping the athlete to his or her best performance. The latter will include medical staff such as team doctors, physiologists, and physiotherapists. They can all expect to be kept busy attending to the health and performance needs of their athletes.

Recent years have brought recognition that sportsmen and women may have mental health needs that are just as important as their ‘physical’ health – and that may need to be addressed. Athletes are people too, subject to many of the same vulnerabilities as the rest of us. In addition to our everyday anxieties, the sports world contains a whole host of different stressors. The impacts of injury or of retirement are particularly associated with psychological stress, even depression, and in weight sensitive sports, the prevalence of disordered eating has long been noted.

With this in mind, overcoming obstacles and adversity is integral to the life of an athlete. Adversity may take the form of a setback such as an injury, or chasing down a lead against tough opponents. One of the major challenges for an athlete is overcoming that posed by his or her own psychological state and more specifically, the ability to overcome and manage pressure. These pressures are factors or combinations of factors that increase the importance of performing well. They may be real or exist primarily in the mind and perceptions of the athlete.

Sport has become a global industry. Events such as the Super Bowl and the Olympics are among the most watched events on the planet and evaluation is largely by binary criteria – winning or losing. An athlete’s performance is judged (whether by themselves or others) and in turn, there are consequences (real or perceived) associated with the outcomes of performance. An athlete will believe (and very often, rightly so!) they have something significant to lose or to gain, known as the ‘fear of failure’ or ‘fear of consequence’.

2010 European Championships in Athletics – during 1500 m final by Antonio Olmedo. CC by -SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

2010 European Championships in Athletics – during 1500 m final by Antonio Olmedo. CC by -SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.Anxiety associated with performance (commonly referred to as ‘competitive anxiety’ or ‘performance anxiety’) has been explored primarily via the applied practice and empirical research of sport psychology. It has been defined as ‘an unpleasant psychological state, in reaction to perceived threat concerning the performance of a task under pressure’. It is considered to be the most common source of situational stress in sport, and is related to the perceived ‘ego-threatening’ nature of the competition. The added public scrutiny and evaluation in sport can mean that both participation and performance are strongly linked to an athlete’s self-esteem and self-worth. Therefore, when working with an athlete, it is important to understand the meaning of sport and performance for that individual athlete.

But what can we all learn from this? Many athletes struggle to come forward and acknowledge their mental health concerns – and when they do, help is not always readily available. For these reasons, two recent stories have caught my eye. From 2005 to 2010, Andy Baddeley was Britain’s leading 1500m runner with a wealth of honours and victories to his name. A depressive illness halted his progress, but as a result, he became a vocal advocate within the mental health community and beyond. In July 2016, he returned to sparkling form with a sub-4 minute mile on the same historic track where Roger Bannister recorded his epic time in 1954.

The story of hurdler Jack Green too is one that inspires hope and optimism for recovery. Suffering from depression throughout most of 2012, he still managed to make the Great Britain team for the London Olympics, where he narrowly missed a medal in the 4x400m relay. How heartening to see him return to near his best form and secure his place yet again in the Olympic team for Rio. Good luck Andy and Jack – an inspiration to us all!

Featured Image Credit: ‘Swimming, Swimmer’ by tpsdave. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Olympian pressure appeared first on OUPblog.

Paradoxes logical and literary

For many months now this column has been examining logical/mathematical paradoxes. Strictly speaking, a paradox is a kind of argument – for example, in some of my academic work I define paradoxes as follows:

A paradox is an argument that:

Begins with premises that seem uncontroversially true.

Proceeds via reasoning that seems uncontroversially valid.

Arrives at a conclusion that is a contradiction, is false, or is otherwise absurd, inappropriate, or unacceptable.

Often, however, such as in the case of the Liar Sentence:

“This sentence is not true.”

there is a central claim that seems to be the root of the paradox, and in such cases we often talk as if the sentence itself is the paradox, rather than the argument. Let’s adopt this informal usage here. Thus, on this looser way of speaking, sentences that cannot be true and cannot be false are paradoxical. We’ll call the kind of sentences just described “philosophically paradoxical”, or paradoxicalP.

In literary theory, some sentences are also called paradoxes, but the meaning of the term is significantly different. If one is in an English department, rather than a philosophy department, and one claims that George Orwell’s claim from Animal Farm that:

“All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

is a paradox, then one is not claiming that this sentence is neither true nor false, or that one can derive a contradiction or absurdity from this claim. Rather, the claim being made is something like this: the sentence in question involves a misleading juxtaposition of concepts and ideas that leads to an unexpected truth. Although this will obscure some of the subtleties, for our purposes we can simplify this as: A sentence is paradoxical (in the literary sense) if and only if it appears to be false, nonsensical, or otherwise problematic, but in fact hides a deeper truth – in short, if it is surprisingly true. Let’s call the kind of sentences just described literarily paradoxical, or paradoxicalL.

It is worth making the following observations, which underlie most of what follows, explicit: If a sentence is paradoxicalP, then it cannot be either true or false. Any sentence that is paradoxicalL, however, must be true, even if it initially appears to be false.

Now, at first glance we might think that this second, literary notion of paradoxicality has little to offer the logician – after all, it is a literary notion, not a logical on. But the opposite is in fact true. We can see this by considering the Literary Liar:

“This sentence is not a paradoxL”

The Literary Liar is either uncontroversially true, and hence is neither kind of paradox, or it is a paradoxP (and hence neither true nor false), but not a paradoxL.

First, the Literary Liar cannot be false. If it were false, then it would not be a paradoxL, since any sentence that is a paradoxL must be true. But it says that it is not a paradoxL, so this would mean that what it says is the case, and hence it would be true. Contradiction.

So the Literary Liar must be true. But now we have two options: either the Literary Liar appears false, nonsensical, or otherwise problematic, or it does not.

Why might we suspect that the Literary Liar is false, nonsensical, or otherwise problematic? Well, paraphrasing loosely, the Literary Liar says something like:

“This sentence is not surprisingly true.”

One might think that this appears, at first glance, to be close enough in content to the Liar Sentence to strongly suggest that similar self-reference induced problems will arise here as well.

If (for whatever reasons) we expect the Literary Liar to be false, nonsensical, or otherwise problematic, then, since it is in fact true, it is a paradoxL. But it says that it is not a paradoxL. So if it is true then it is not a paradoxL. Contradiction, and we have our paradox (of the philosophical variety).

If, however, the Literary Liar does not appear to be false, nonsensical, or otherwise problematic at first glance, then there is no paradox. The Literary Liar, in this situation, would be true, but not surprisingly so, and hence neither a paradoxP nor a paradoxL.

To sum up: If the Literary Liar is not a philosophical paradox, then it is true, but not surprisingly so. Surprising, no?

This example highlights another important fact: Whether or not a sentence is a paradoxL depends on our expectations – that is, on whether or not we expect it to be false, nonsensical, or otherwise problematic. ParadoxicalityP does not depend on our expectations in this manner.

In addition to examining constructions involving the literary notion of paradoxicality, we can combine these two notions to obtain some interesting puzzles. For example, consider the sentence:

“This sentence is a paradox, but is not a paradox.”

On the face of it, this sentence looks plainly false. In fact, however, given the two readings of “paradox” we have to hand, the sentence is ambiguous, and on one reading could be true!

There are four ways that we can disambiguate the sentence in question, depending on how we label the two occurrences of “paradox” with our subscripts “P” and “L”:

This sentence is a paradoxP, but is not a paradoxP.

This sentence is a paradoxL, but is not a paradoxL.

This sentence is a paradoxP, but is not a paradoxL.

This sentence is a paradoxL, but is not a paradoxP.

Readings (i) and (ii) seem, on the face of it, to be plainly false: a sentence cannot be both a paradoxP and not a paradoxP, nor can it be both a paradoxL and not a paradoxL (dialetheists: please forgive my brushing over some subtleties in case (i) – doing so allows us to get to some less subtle but much more fun issues in the other cases).

Reading (iii) also seems false: It can’t be true, of course, because then by the first conjunct it would also have to be a paradoxP, but a paradoxP is a sentence that can’t be true and can’t be false. But on reading (iii) the sentence in question can be false, since in such a case it wouldn’t be a paradoxP and hence what it says would not be the case. Since it can consistently be false, it isn’t a paradoxP, and so is in fact false.

Reading (iv) is the most interesting, however, since it seems to work a bit like the sentence known as the Truth Teller:

“This sentence is true”

The Truth Teller, intuitively, is indeterminate: If it is true, then what it says is the case, which is exactly what is required of a true sentence. If it is false, then what it says is not the case, which is exactly what is required of a false sentence. Thus, it could be true and it could be false, and there seems to be no additional information that can determine which it is.

Similarly, on reading (iv) our sentence might be true and it might be false. First, notice that the sentence, without our disambiguating subscripts, certainly appears to be false – it has the form “P and not P”. So, if it is true, then the fact that it is true is surprising. So if it is true, then it is a paradoxL. And if it is true then it is certainly not a paradoxP. Thus, if it is true, then what it says is the case, which is exactly what is required of true sentence.

Second, if the sentence is false, then it is not a paradoxL, so it is certainly not the case that it is a paradoxL but not a paradoxP. So what it says is not the case, which is exactly what is required of a false sentence.

The reader is encouraged to consider the following slight variation of this sentence to see what difference inclusion of “unsurprising” makes:

“Unsurprisingly, this sentence is a paradoxL, but is not a paradoxP.

Some interesting issues with regard to the logic of “surprising” arise, consideration of which I will leave to the reader.

Featured image: Abstract by geralt. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Paradoxes logical and literary appeared first on OUPblog.

August 13, 2016

Mental health inequalities among gay and bisexual men

Depression, substance abuse, and suicide have long been associated with homosexuality. In the decades preceding the gay liberation movement, the most common explanation for this association was that homosexuality itself is a mental illness. Much of the work of gay liberation consisted of dismantling the pathological understanding of homosexuality among mental health professionals. It was partly the direct challenges by gay people to the psychiatric profession that led to the removal of homosexuality by itself from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1973. Some still hold the view that gay desire is a pathology. It’s no coincidence that the Catholic Church declared that “homosexual acts are intrinsically disordered” in 1975, at precisely the same time that the psychiatric establishment was reorienting itself to the problems gay people experience rather than being gay itself.

Research about the mental health of sexual minorities (that does not start from the assumption that non-heterosexuality is the problem) is in its relative infancy. However, by now a number of studies using representative samples have shown that a range of mental health problems are more common among sexual minorities than the sexual majority. But generally, comparing gay people with straight people is about as far as they can go. Sometimes lesbians, gay men, bisexual men and women, and other non-heterosexuals are grouped together and when they are separated they are still considered as homogenous groups. Majorities tend to think minorities are more alike than they actually are. Because a minority group shares one characteristic, they are assumed to share most other characteristics. This is one of the mechanisms of stereotyping. However, even casual observation reveals that gay men, for example, are extremely diverse. So how is that diversity reflected in their mental health?

Since there are very few quantitative answers to this question, we sought to determine measures of depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and self-harm among a large convenience sample of gay and bisexual men recruited through a wide range of settings. All four indicators were associated with younger age, lower education, and lower income. Depression was also associated with being a member of visible ethnic minorities and sexual attraction to women as well as men. Cohabiting with a male partner and living in London were protective of mental health.

Convenience samples come in for a lot of criticism. But while we should be wary of their known problems, we should not dismiss them when they are the only source of evidence we have. Convenience surveys of sexual minorities complement, rather than compete with, representative general population surveys that include a sexuality question. Even the largest representative samples of the general population recruit only small absolute numbers of sexual minorities and this greatly limits the detail such studies can describe.

It is far from the case that the poor mental health experienced more often by sexual minorities than the sexual majority is equally experienced across those minorities. Mental health inequalities observed in the general population are carried over, perhaps compounded, among sexual minorities.

So why would gay and bisexual men who are also members of other minority groups be more vulnerable to mental health challenges? Understanding the relationships will be key to responding to them. Three possible explanations present themselves.

Firstly, if experience of homophobia is the primary cause of poor mental health among gay and bisexual men, it may not be equally experienced. Here the levels of discrimination (minority stressors) that cause poor mental health are different. This is congruent with the observation that younger men bear the brunt of homophobic abuse and assault and also suffer the greatest impact.

A second explanation is that even when homophobia is equally experienced across different groups (ie. same level of sexual minority stressors) what differs is that some men are more able to resist its impact than others. Some men, perhaps those with higher education and more social support, are better able to mitigate the effect of homophobic oppression if they are relatively privileged in other areas of their lives. In this explanation, the effects of homophobia are not uniform across other axes of social justice.

A third explanation proposes that regardless of the levels and effects of sexual minority stress, some gay and bisexual men also experience discrimination or marginalisation through mechanisms other than those related to their sexuality such as racism and poverty.

All three explanations may be in operation and the contribution each makes to overall outcomes could be expected to differ by the social axis under consideration. But it is clear that mental health promotion for gay and bisexual men will increase its impact if it attends to age, income, and relationship status, preferably targeting younger, poorer, single men. We need to challenge a narrow conception of the gay movement as being about equality between straight and gay and remind ourselves that the mental health challenges of young, poor, single gay men will not be addressed by well-off middle-aged gay couples becoming equal with well-off middle-aged straight couples.

Image credit: Gay Liberation Monument by Raphael Isla, CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Mental health inequalities among gay and bisexual men appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers