Oxford University Press's Blog, page 162

February 7, 2020

How old music conservatories turned orphans into composers

If you approached bystanders on a street corner in sixteenth-century Naples and asked them “What do conservatories conserve?” the likely answers would not have been “performing arts” or “rare plants.” No, you would have been told confidently that conservatories conserved orphans and foundlings. These church-sponsored orphanages practiced a kind of alchemy—they took in defenseless little social outcasts and transformed them into skilled artisans whose services would one day be in high demand. A range of skilled trades were taught at the almost two hundred conservatories in Naples, including four conservatories that taught the trade of music.

A seven- to ten-year-old boy entering one of the four music conservatories in Naples might as well have been enlisting in the army. Six days a week from sunrise to sunset he had to follow a regimented existence where lessons in music were interspersed with lessons in reading, writing, and other subjects that would be useful to a future court or church musician. There were no vacations or trips to see the family because for an orphan boy the conservatory was home and its teachers and students were all the family he had. When the alternative was begging on the street, one can be assured that a conservatory boy was determined to make a go of it.

Was this a form of child abuse? Were the old conservatories like dysfunctional Olympic training camps where young athletes could be exploited for the sake of future medals and national pride? Answering that question fairly would first require that we today and the inhabitants of Naples centuries ago could agree on what children ought to do with their childhoods. Modern parents might think of childhood as a special time to frolic and grow, safe from the cares of the adult world. The old Neapolitans, by contrast, seem to have viewed childhood as a burdensome and dangerous period that should be grown out of as soon as possible. They assumed that all but aristocratic children would work as soon as they were able, starting with easy tasks and eventually reaching an adult level of competence. Children with parents worked approvingly alongside them in the family business or trade. Similarly, older children in the conservatories were rented out to work as junior musicians in order to help support their institution.

While improvisation plays almost no role in classical music today, in Naples it was central to the curriculum. A student would sit at a harpsichord and be given a left-hand, bass part to play as written. The student’s right hand was then expected to improvise a melody and perhaps some chords to bring out or “realize” what was implicit in the bass. Much like a modern studio musician improvising a performance based on a single-staff lead sheet, the Naples-trained musicians used single-staff basses as cues to produce multi-voice compositions. This type of instruction was so successful that musicians trained that way came to dominate Europe and its colonies by the eighteenth century. The Paris Conservatory was set up in 1795 to imitate Neapolitan successes, and most conservatories today can trace their descent back to those early institutions.

In recent years the meteoric rise of the child composer Alma Deutscher has given a good indication of how powerful the old, improvisation-based lessons can still be in the hands of a precocious child. She was trained from age five in the same exercises taught to the orphan boys of old Naples. The need to internalize specific musical patterns in order to be able to complete guided improvisations led to the development of a rich vocabulary of melodies complete with harmony and counterpoint. Alma, like those orphans of long ago, gradually became able to “speak” classical music, and from that point onward the art of composition became mostly the process of notating musical passages already conceived in her mind. The old conservatories, in developing reliable methods to teach a trade, ended up training talented young minds to think directly in a language of multi-voice music. What today we call classical music is in many cases just surviving transcriptions of those nonverbal thoughts.

Featured image credit: Choir Boys. Painting by William Frederick Yeames, 1891. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post How old music conservatories turned orphans into composers appeared first on OUPblog.

February 6, 2020

Celebrating Black History Month with America’s top musicians [playlist]

Black History Month is cause for celebration and remembrance of black excellence throughout American history. This February, we’re celebrating with a playlist highlighting some of the most remarkable musicians of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Beginning with ragtime pioneer, Scott Joplin, this playlist navigates through the many different musical movements created and perfected by black artists.

Ragtime gave way to jazz, as exemplified by such musical legends as Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole, and Miles Davis, was soon followed by Ray Charles, whose fusion of blues, R&B, and gospel styles helped create soul music. Soul music became the sound of the 1950s.

As the decade went on, soul music began to incorporate and adapt the sound of pop music. Capitalizing on such a commercial sound, Berry Gordy rounded out the decade with the founding of Motown Records in 1959, dubbing the soul-pop sound after the name of his label: Motown.

Early Motown singers featured talents such as Marvin Gaye, The Supremes, and The Temptations. Yet with the looming overhead of the Vietnam War, music turned towards psychedelia and rock and roll, welcoming into being the legendary electric guitar stylings of Jimi Hendrix, as well as the funky rock music of Stevie Wonder, the youngest artist to ever top the Billboard Hot 100 charts.

The mid-1960s introduced Aretha Franklin, the Queen of Soul, alongside other black artists who began to lattice soul music into their own sound, including Tina Turner, the Queen of Rock n’ Roll. Rising to stardom in the latter-end of the decade, Turner’s sound fused rock and roll with soul music, becoming an amalgamate representation of the musical stylings of the decade.

Alongside the rise of Franklin and Turner also came the Civil Rights movement. This era featured the voices of jazz singer Nina Simone, an advocate against racial inequality, as well as classical artists Paul Robeson and Marian Anderson. Robeson and Anderson, avid political activists, were also successful black artists in a historically white-dominated profession, demonstrating musical excellence while also advocating for equality.

Following the Civil Rights era came the musical innovations of the 1970s, introducing the early beginnings of hip-hop. In 1979, the Sugarhill Gang released “Rapper’s Delight,” one of the first rap songs to make the Top 40 chart, widening the audience for the genre. The 1970s and early 1980s also introduced the genre of disco, and the fusion of pop music and dance-soul, which influenced the musical endeavors of icons Prince and Whitney Houston heavily.

Towards the end of the 1980s, hip-hop experienced its golden age, and included artists such as Run-D.M.C. and Grandmaster Flash. The 1990s cemented hip hop’s longevity and introduced artists such as Tupac Shakur and the Notorious B.I.G.

More recently, black artists such as Beyoncé, Janelle Monae, and Pulitzer Prize-winner Kendrick Lamar have expanded upon the musical movements before them, evolving, celebrating, and pushing the boundaries of the sound of black artistry.

Tune in to our playlist, Celebrating Black History Month, curated chronologically to trace some of the twentieth- and twenty-first century manifestations of black musical excellence.

Note: This playlist features explicit content.

Image courtesy of Janine Robinson via Unsplash .

The post Celebrating Black History Month with America’s top musicians [playlist] appeared first on OUPblog.

February 5, 2020

Etymological insecticide

This story continues the attempts of the previous week to catch a flea. Anyone who will take the trouble to look at the etymology of the names of the flea, louse, bedbug, and their blood-sucking allies in a dozen languages will discover that almost nothing is known for certain about it. This fact either means that we are dealing with very old words whose beginnings can no longer be discovered or that the names have been subject to taboo (consequently, the initial form is beyond recognition), or, quite likely, both factors were in play. Common sense suggests that those names should refer to stinging, biting, color, size, and shape, or the parasites’ deleterious effect, but of course onomatopoeia should not be discounted either: though fleas and lice are silent, mosquitoes are not. It always amuses me that the standard etymology of the Russian word komar “mosquito” (stress on the second syllable) refers kom to sound imitation. Do those pestiferous insects buzz kommm? Hmm, perhaps. The German for “bumblebee” is Hummel, but bumblebees really “hum.”

To make matters worse, if the name whose origin we are exploring means “pest” or “biter,” or “buzzer,” it will fit more than one insect. What word can be simpler than tick? Doesn’t it tickle before it digs itself in? Tickle is rather obviously sound-symbolic. One of its variants is kittle (compare German kitzeln), and its shorter relative is tick (verb); tick-tack-toe also comes to mind. It does not seem that any dictionary is ready to connect tick and tickle. Armenian tiz means “beetle.” A cognate, a chance parallel? Irish dega “stag beetle” has been compared with tick, but how far does this comparison lead? Wherever we may look, we end up with similar lists. That is why when I see the reconstructed root of the word flea represented as bhsul– or bhlus-, I question their reality (was there such a “root”?). Nor does the occasionally invoked closeness between flea and fleece fill me with enthusiasm.

Johann N. Hummel, 1778-1837, a composer and great pianist. Portrait of Hummel, circa 1814, via Wikimedia Commons.

Johann N. Hummel, 1778-1837, a composer and great pianist. Portrait of Hummel, circa 1814, via Wikimedia Commons.Insects are hard to exterminate, and their names are as hard to etymologize. More than once have I referred to two laws of etymology that I have discovered for myself and that seem to work in all cases. First: every time a word of dubious or unknown origin is expected to shed light on the origin of another obscure word, the result turns out to be wrong. Second: the more complicated an etymology is, the higher the chance that it is wrong, because correct etymologies are usually simple and almost immediately convincing. It is the second law that concerns us here.

The Russian for “louse” is vosh’. Its Slavic cognates sound very much alike. Lithuanian víevesa ~ vievesà, obviously a reduplicated form, looks like a good congener. Finnish väive was probably borrowed from Baltic. The origin of those words, as long as they remain in their Slavic-Baltic home, need not bother us here. English has louse, from lūs, and this form is similar all over Germanic. The apparently related Welsh form sounds as llau, and this fact led to the conclusion that in lūs, –s is some sort of ending, with the root being lū-. Now, in Sanskrit, the louse was called yūkā, while the Slavic vosh’ begins with v, apparently, from w-. The same holds for Lithuanian. Therefore, a brave attempt has been made to combine w- with l- and produce a protoform that would begin with l’. I find such attempts clever but moderately persuasive. Even if there was an Indo-European protoform, numerous changes have garbled it beyond recognition. With taboo and expressive formations always in play, the sought-after protoform is sure to escape us.

My skepticism should not discourage serious students of language history. For instance, Engl. hornet begins with h. Assuming that it has a non-Germanic cognate, it should begin with k- (by the First Consonant Shift, to which I refer in almost every post). And indeed, the Latin for “hornet” is crabro. But in Slavic, the consonant corresponding to Germanic h and Latin k is, in a certain phonetic environment, s, which became sh, and lo and behold! the Russian for “hornet’ is shershen’, which means that the hornet has nothing to do with horns (indeed, why should it?), and only folk etymology makes us think about them. Gambols, like those which connected hornet, crabro, and shershen’, are perfectly legitimate, because they are regular, that is, the same correspondences occur in all words of the same structure. But etymological games with flea and louse are individual exercises, invented for one occasion only, and therefore they do not inspire much confidence.

There are greater miracles than the travels of the Indo-European consonant k. Old Engl. loppe meant “spider” and (!) “silkworm.” Alongside of it, the word loppestre (with the variants lopystre and lopustre) existed. It meant “locust,” a borrowing of Latin locusta. But why lopystre ~ lopustre rather than locust? Not improbably, loppe also meant “flea” or some other jumping insect, and the locust gained its name under the influence of this loppe: just another jumper! If my guess has credence, lopustre is a folk etymological blend of loppe and locusta. (Blends are words like motel, Brexit, and the horrible incel.) But our voracious jumper did not stop there. Its elongated body aroused an association with a large marine crustacean, known to all of us as lobster. Quite an adventure! Many words for “beetle” and its kin seem to have denoted “sack, bunch, pin, etc.,” with reference to their shape; loppe looks like one of them.

Close relatives, right? Locust from christels via Pixabay; lobster from PublicDomainPictures via Pixabay.

Close relatives, right? Locust from christels via Pixabay; lobster from PublicDomainPictures via Pixabay.Another endearing character in our drama is the nit. The word goes back to Old Engl. hnitu. Its Slavic cognates begin with gn– (Russian gnida, and so forth). Old Norse also had gnit, and so do its modern continuations in Swedish and Norwegian. Elsewhere, the name of the same creature begins with gl-, rather than gn-: such is Lithuanian glìnda. Naturally, all such forms have been traced to more or less appropriate verbs, meaning “to scrape,” “to destroy,” “to rot,” “to rub,” and so forth. But one wonders again: Were all such words derived from verbs? Were they not expressive formations, perhaps coined to resemble some verbs but not connected with them? Gn– and kn– are common beginnings of sound-imitating and sound-symbolic words: compare gnaw, gnash, knock, and their likes.

Indeed, have we forgotten gnat? All over Indo-European one runs into its kin, including of course nit, mentioned above. Consider Russian gnus “(a swarm of) very small insects” (believe me: no meshes in a mask are too small for that pest), Latvian knischi “flies swarming in the dust” (my spelling is probably obsolete), and others.

It is only fair to admit that the names of insects obviate the strict laws of etymology with great success. This conclusion should not be equated with the verdict “origin unknown”; rather it means that we are dealing with ludic forms, whose formation violates the rules applicable to the words chosen to designate less troublesome creatures than lice, fleas, flies, and gnats. Language is not algebra, and this circumstance constitutes one of its main charms.

PS. Last week, we observed Goethe’s and Mussorgsky’s celebration of the flea. The flea also graces Nikolai Leskóv’s tale about how a lefty shod this creature. The story was turned into a play by Yevgeny Zamyatin, the author of the famous dystopia We. Both are worth reading.

Nikolai Leskov’s tale on the left, and Yevgeny Zamyatin, 1884-1937, on the right. Title page to The Steel Flea published by Gentlemen Adventurers, Boston, 1916. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Zamyatin portrait by Boris Kustodiev, 1923. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Nikolai Leskov’s tale on the left, and Yevgeny Zamyatin, 1884-1937, on the right. Title page to The Steel Flea published by Gentlemen Adventurers, Boston, 1916. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Zamyatin portrait by Boris Kustodiev, 1923. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.PPS. I would like to finish this short series by expressing my appreciation of the charming poem John Cowan posted in the comments to the previous post, and to Constantinas Ragazas for correcting my Greek

Featured image credit: Image by Hans Braxmeier from Pixabay.

The post Etymological insecticide appeared first on OUPblog.

The language gap in North African schools

When children start school in an industrialized country, their native language is for the most part the one used by the teachers. Conversely, in many developing countries, the former colonial languages have been proclaimed languages of instruction within the classroom at the expense of native indigenous languages. A third scenario is something in-between: The language used at school is related to the home language but is a significantly different variety. This is the case in the Arabic-speaking world where the native dialects are used at home and on the street while Modern Standard Arabic is used in education and in other formal domains. In the latter two cases, the stakes are higher for the students from the very onset of their learning journey: They must acquire a second linguistic system and develop literacy skills, both at the same time.

In North Africa, students acquire their native Arabic dialects at home before starting school. Some students also acquire Berber in the areas where it’s still transmitted naturally. Since the Arabic vernaculars aren’t standardized or officially recognized by the state, they’re not taught at schools and there aren’t any textbooks or dictionaries aimed at native speakers. As a result, students must develop literacy in Modern Standard Arabic, a language that diverges to a significant extent from the native vernaculars. There are different words that refer to the same things and even aspects of the grammar are different. For example, while Tunisian Arabic has seven subject pronouns (eight in some varieties), Modern Standard Arabic has twelve, including the dual pronouns that don’t exist in vernacular Arabic. As a result, Tunisian students have to make a conscious effort not only to develop literacy in the standard variety of Arabic, but also to learn how to speak it extemporaneously in order to communicate successfully in the classroom.

In addition to Modern Standard Arabic, schools in Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco introduce French as a second language, usually in elementary school. In Tunisia, the instruction of French starts around the age of eight, before French becomes a language of instruction for many subjects starting in middle school.

Both in the educational system and on the local job market, a divide exists between students who pursue their studies primarily in Modern Standard Arabic and those who do so in French. STEM education (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), including computer science, is delivered in French in Tunisian high schools. Students who choose tracks that focus more on these subjects will develop higher levels of proficiency in French than students who choose the humanities stream, which has more hours of instruction in Modern Standard Arabic. The result of this added exposure to either language creates a gap in levels of proficiency that stratifies the Tunisian population according to their comfort using Modern Standard Arabic and/ or French. This has implications for social mobility, as both languages have different and competing symbolic, cultural, and material capitals in the Tunisian linguistic market.

Proficiency in French is often used as a proxy metric for educational attainment, professional competence, and overall higher socioeconomic status. Modern Standard Arabic on the other hand is closely associated with the national religious and cultural heritage and pan-Arab ideologies. With this rivalry between Modern Standard Arabic and French in the background, the local Arabic vernacular, Tunisian Arabic, is gradually acquiring more capital and starting to be used by private citizens and public authorities alike on multiplatform media. This is more so since the 2011 Revolution. Additionally, the turn of the century has brought with it an increased presence of English as a global language. Thanks to the vast amounts of materials available for the acquisition of English, increasing numbers of Tunisians are developing higher levels of proficiency in this language and employing it in daily conversation and on social media.

While there are public discussions about which languages to use at school, conflicting ideologies make it hard for real change to happen. For the time being, it appears that North African students will continue to develop initial literacy in Modern Standard Arabic and use French in many STEM subjects throughout their educational trajectory. This affects school attainment for many school children who may fall behind, not necessarily because the subject matter is challenging, just because they don’t understand the language of instruction.

Featured Image Credit: Lindstedt via Unsplash

The post The language gap in North African schools appeared first on OUPblog.

February 4, 2020

Using math to understand inequity

What can math tell us about unfairness? Bias, discrimination, and inequity are phenomena that are deeply complex, context sensitive, personal, and intersectional. The mathematical modeling of social scenarios, on the other hand, is a practice that necessitates simplification. Using models to understand what happens in our social realm means representing the complex with something much less complex in order to study it.

Nonetheless, when used carefully models can help us learn about deep patterns related to inequity, including those that govern how unfair norms and patterns of behavior emerge in groups of people. They are especially useful in highlighting spaces of possibility. What might happen in the complex dynamics of the social realm? Once we answer this question, we can use experiments and experimental studies to learn more about these possibilities.

In recent work by fellow modelers and myself, we’ve looked in particular at what minority status means for patterns of unfair behavior. Suppose you are part of a company where people work together, but are still figuring out some of the social rules for how this is done. Suppose further that men make up the majority of workers and women the minority. And lastly suppose, as argued by Cecilia L. Ridgeway in Framed by Gender, that like most humans your coworkers notice gender, and use it to shape their interactions with others in ways that can be subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle). In a case like this, even without gender biases coming into play, women can end up disadvantaged.

The basic mechanism for this disadvantage relates to the speed with which people learn to interact with others. Say that men make up 90% of office workers, and women 10%. This means that 90% of the time women will be interacting with their “out-group”, while men will be doing the same thing only 10% of the time. We can reasonably expect that women figure out how to treat men in the office more quickly than the reverse. This is a general observation about minority status, majority members are, on average, exposed to the other group less, and so learn about them less quickly.

Evolutionary biologists have shown that when it comes to mutualistic interactions between species, sometimes the species that evolves more quickly ends up at a disadvantage simply by dint of this quick evolution. This is called The Red King Effect. Surprisingly, starting with the work of Justin Bruner, it has become clear that a similar thing might happen in the cultural realm. How?

When it comes to joint action – doing a project together, or forming a company, or running a household – a bargain of a sort is needed to figure out who does how much labor, and who gets what rewards. The bargain need not be explicit, but somehow the issue must be settled. In general, accommodating demands tend to be safe ones in bargains. If you accommodate, usually your partner will be satisfied. When individuals are quickly learning to bargain with another group, this means that in many cases they quickly move towards accommodation. (Think, “don’t worry, I’ll finish the memo” or “I’ll stay to finish cleaning up”.) Once this happens, the majority group can more slowly learn to take advantage of this accommodating behavior by demanding a lot of their partners.

Under other conditions, small groups can actually gain an advantage by learning quickly. This depends on the details of the kind of interaction they are engaged it. I’ve argued, though, that in many real-world cases we should expect conditions to hold that will disadvantage minority groups, including those with intersectional identities.

Of course, much discriminatory behavior is more nefarious than this. It often involves racial, gender, or other biases against members of certain social groups. Given what we’d found in our models, though, my collaborators and I began to wonder whether this simple mechanism – based only on group size and learning speed – could lead to disadvantage for real humans.

We asked experimental subjects to engage in bargaining interactions between two groups. One group was smaller than the other, but otherwise the two groups were completely identical. After having the groups learn to interact with each other, we checked to see how much money they had earned through their bargaining. We found that, on average, the smaller groups earned significantly less, perhaps because of the very mechanism we had identified. This study is not definitive. It is relatively small, and involves restrictive lab conditions. But it points to a general take-away about the use of simplified models to study complex social phenomena.

Without the models we developed to study inequality, we never would have guessed that just being in a small group might be a disadvantage. There was no a priori reason to test such a hypothesis. Once modeling work opened up this possibility, though, it gave us reason to experiment. In general, models can point us to possibilities we might never have imagined without computational resources. They can tell us what dynamical effects might plausibly occur in the social realm. Of course, they can’t tell us for sure whether or not these effects are actually at play. But they can direct us towards empirical work that we otherwise would never have engage in. When used carefully, and with the right back and forth with other methods, models are an important part of the social science toolbox, even for topics as complex as unfairness.

Featured Image Credit: Markus Spiske on Unsplash

The post Using math to understand inequity appeared first on OUPblog.

February 3, 2020

Six books to read to understand business innovation [reading list]

According to McKinsey & Company, 84% of executives agree on the importance of innovation in growth and strategy in their organizations but only 6% know the exact problem and how to improve in innovation. As the world is moving faster and getting more complex, it is important to find ways to constantly innovate for organizations and managers. Innovation day is observed every year on 16 February, to create further awareness on the importance of innovation we have created a list of books with free chapters that show the importance of innovation for business and society.

1. Open Innovation Results, by Henry Chesbrough

To get real business results from innovation, we must go beyond the generation of new innovations, and also pay attention to their broad dissemination and rapid absorption. Many of the best known aspects of open innovation, such as crowdsourcing or open source software or innovation intermediaries, are not well connected to the rest of the organization. We must connect more deeply to the rest of the organization, in order to see real business value from innovation. This book offers the latest theory and evidence from open innovation processes, and discusses how to get real business results from it. Read a free chapter online here.

2. Openness to Creative Destruction, by Arthur M. Diamond, Jr.

Life improves under the economic system often called entrepreneurial capitalism or creative destruction but, according to the author, should more accurately be called innovative dynamism. This book shows how innovation occurs through the efforts of inventors and innovative entrepreneurs, how workers on balance benefit, and how good policies can encourage innovation. Read a free chapter online here.

3. Innovation Commons, by Jason Potts

This book presents a new theory of what happens at the very early stages of innovation. It describes how a new technology is transformed into an entrepreneurial opportunity and becomes the origin of economic growth. The surprising answer is cooperation. Read a free chapter online here that proposes four theories explaining how innovation commons work, in terms of how they pool information, and what specific problems they solve in order to discover entrepreneurial opportunities.

4. Holistic Innovation Policy, by Susana Borrás and Charles Edquist

This book presents a theoretical foundation for the design of innovation policy by identifying the core problems that afflict the activities of innovation systems, including the unintended consequences of policy itself. It shows how to identify viable and down-to-earth policy solutions. Read a free chapter online here. It identifies ten specific activities that define systems of innovation.

5. The Disruptive Impact of FinTech on Retirement Systems, edited by Julie Agnew and Olivia S. Mitchell

Many people need help planning for retirement, saving, investing, and decumulating their assets, yet financial advice is often complex, potentially conflicted, and expensive . This volume examines how technology is transforming financial applications, and how FinTech promises a similar revolution in the retirement planning processes. Read a free chapter online here that describes the development of the robo-advisor industry and compares robo-advisors to traditional human financial advisors.

6. Society and the Internet, edited by Mark Graham and William H. Dutton

How is society being reshaped by the continued diffusion and increasing centrality of the Internet in everyday life and work? This book provides key readings for students, scholars, and those interested in understanding the interactions of the Internet and society. The Internet and digital media are increasingly seen as having enormous potential for solving problems facing healthcare systems. Read a free chapter online here that traces emerging digital health uses and applications, focusing on the political economy of data.

Innovation is the core reason for modern existence. Innovation doesn’t only help organizations stay relevant but also plays an important role in economic growth. With more information on the topic, we can help to understand the importance of innovation and what it means for business and our society.

Featured image credit: Image by Michal Jarmoluk from Pixabay

The post Six books to read to understand business innovation [reading list] appeared first on OUPblog.

February 2, 2020

Usage issues—How are you doing?

When people talk about grammar problems, they often mean usage issues—departures from the traditional conventions for edited English and the most formal types of speaking.

To a linguist, grammar refers to the way that language is used—by speakers of all types—and the way that it works—how it is acquired, how it changes, and so on. We follow the conventions when we are writing in a particular style, but also look at the conventions with a critical, curious eye.

You might think of us as the internal affairs division of the grammar police.

That curiosity and skepticism is important because usage conventions are often underdetermined by the actual language use—in other words, educated speakers don’t worry much about certain things in speaking but have to attend to them in certain types of written expression. The who-whom distinction is an example. Whom do you trust? is traditionally prescribed, but the colloquial Who do you trust? is more trust-worthy.

Secondly, some traditional rules are non-rules: grammatical superstitions handed down from generation to generation sometimes by people who are incurious about language but like to judge others. The non-rules that sentence should not begin with and or that infinitives should not be split fall into this category.

And many rules are incomplete, only applying to certain troublesome words or in certain grammatical situations.

Take well and good, for example. You probably learned that well is an adverb and good is an adjective, so we use one to modify verbs (as in She writes well) and one to modify nouns (a good writer). But the situation is more complicated than that. The adjective form is also used after a linking verb, as in Dinner was good or The coffee tastes good or I feel good today.

We don’t standardly use good as an adverb, so if someone says Marta writes good, we treat that as a usage error—the substitution an adjective when an adverb is called for. However, well can be used as an adjective referring to health. When we say Glinda is well, we are often referring to health. The adjective good can serve as a general characterized of righteousness: Glinda is good or as characterization of well-being: I feel good, I am good, The coffee tastes good, The roses smell good, Things look good, and so on.

What do you say when someone asks “How’re you doing?” Since well can be an adjective or an adverb, it’s fine to say “I’m well” or “I’m doing well” or simple “Well.” And since good is an adjective it is also legitimate answer to the greeting “How are you doing?” One can answer “I’m good” or the shorter “Good.” (Or “I’m okay, fine, terrific, great” etc.).

The same options exist for the pair “well-paying job” and “good paying job.” While some sources will prescribe only the formal “well-paying” (on the pattern of the “well-written,” “well-wrought,” and “well-argued”), others prefer the more colloquial “good-paying” (on the pattern of “good-looking,” “good-tasting,” “good-natured”). It’s not as simple as adjective versus adverb.

Another example is “slow” and “slowly.” Walking to a meeting, I suggested that we should walk slow so someone could catch up with us. You mean “slowly,” someone corrected. I replied that “slow” was fine and it is. “Slow” can be used as an adjective or an adverb.

Examples of adverbial “slow” from the Oxford English Dictionary include “how slow This old Moone waues” from Midsummer Night’s Dream (i. i. 3), “I hear the far-off Curfeu sound, … Swinging slow with sullen roar” from Milton, and “We drove very slow for the last two stages on the road,” from Thackery’s Vanity Fair. We find it as well on road signs exhorting us to “Drive slow.” But adverbial “slow” does not occur everywhere that “slowly” can. Slow occurs after verbs rather than before them and it is used primarily as an adverb with verbs of motion. But to deny its status as an adverb is, as Bryan Garner puts it, “ill-informed pedantry.”

Usage is rarely simple and absolute. It is more complex—and more interesting—than we often believe.

Featured image credit: “Focus definition” by Romain Vignes via Unsplash.

The post Usage issues—How are you doing? appeared first on OUPblog.

February 1, 2020

Henry David Thoreau and the nature of civil disobedience – Philosopher of the Month

Henry David Thoreau was an American philosopher, environmentalist, poet, and essayist. He is best known for Walden, an account of a simpler life lived in natural surroundings, first published in 1854, and his 1849 essay Civil Disobedience which presents a rebuttal of unjust government influence over the individual. An avid, and widely-read, student of philosophy from the classical to the contemporary, Thoreau pursued philosophy as a way of life and not solely a lens for thought and discourse.

Born in 1817 in Concord, Massachusetts, Thoreau was raised in a modest household by his parents John Thoreau, a pencil maker, and Cynthia Dunbar. He was to spend almost all of his life in Concord, save for his time at Harvard from 1833 to 1837 where he studied classics, philosophy, science, and maths. After graduating and returning to his hometown, Thoreau with his brother John opened the Concord Academy, which alongside a traditional program also promoted new concepts such as taking walks in nature and paying visits to local businesses.

An early friendship and influence came in the form of the essayist and Transcendentalism founder, Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson a champion of Thoreau, encouraged him to keep a journal which became a life-long habit and from which his first written piece for journal The Dial was taken. Their friendship was to last for many years, despite a differing and diverging of philosophies as Thoreau moved away from transcendentalism. Thoreau eventually built a small hut in wooded land owned by Emerson by the shores of Walden Pond, where he would live for two years. The stay was to provide the basis of Walden, published in 1854.

In Walden or Life in the Woods Thoreau records his spiritual and philosophical two year, two month, and two day sojourn ensconced in a “tightly shingled and plastered” cottage deep in the New England forests. It focuses on themes of simplicity, self-sufficiency, solitude, and spirituality, with the woodland dweller recording intricate details of his economies; the sounds, geography, environmental changes of his habitat; and his thoughts on everything from vegetarianism to teetotalism to chastity. Walden defies categorization and many have questioned whether the book is a true work of philosophy. It does not question so much as it describes, yet the very nature of the text encourages us to explore some fundamental philosophical concepts.

If Walden gives us reflection, Civil Disobedience gives us intent. Also known as Resistance to Civil Government, this short essay, published in 1849, was derived from a blistering series of lectures and is seen in part as a reaction to slavery and the Mexican-American War. Thoreau firmly asserted the rights of the individual against an unjust state. Despite his support of abolitionist John Brown’s call for use of arms to overthrow slavery, Thoreau believed in non-violent protest and exercised civil disobedience through alternate methods. In July 1846 Thoreau spent the night in jail after refusing to pay poll tax, saying he opposed supporting a government tax where he had no knowledge of how the money was to be spent. Civil Disobedience has gone on to inspire many other notable figures since its publication.

In later life Thoreau became further entranced by the natural world and travel. His travels took him across North America and Canada, stimulating many papers and books, as well recordings in his journal.

Walden and Civil Disobedience offer a lens on Thoreau’s life and work. We see a man, humble (he worked alongside his father in the pencil factory for much of his life), thoughtful, conscious, passionate, and quietly revolutionary. Aware he was dying, when asked by his aunt Louisa if he had made his peace with God, Thoreau famously replied “I did not know we had ever quarrelled”.

Henry David Thoreau died aged 44, on 6 May 1862.

Featured image credit: Noah Silliman via Unsplash

The post Henry David Thoreau and the nature of civil disobedience – Philosopher of the Month appeared first on OUPblog.

January 31, 2020

How the UK is facilitating war crimes in Yemen

More than 100,000 people have died in the war in Yemen since March 2015, including over 12,000 civilians killed in direct attacks. All parties to the war have committed violations of international law, but the Saudi-led coalition—armed and supported militarily and diplomatically by the United States and the United Kingdom primarily—is responsible for the highest number of these reported civilian deaths. In addition, the coalition aerial and naval blockade have contributed to politically-induced famine in which three quarters of the population of 28 million are experiencing food insecurity. Of those, 8.4 million people are wholly dependent on food aid to survive. Save the Children estimates that 85,000 children under the age of five have starved to death as a result of the war. And one million people are suffering from cholera – the worst outbreak since 1949, when modern records began. The latest report of the UN ‘s Group of Eminent Experts stated that people in the governments of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab United Arab Emirates, as well as Houthi leaders, may be individually criminally liable for war crimes, and that arms-supplying states, including the UK, may be legally responsible as well.

The UK – alongside the United States – provides weapons, engineering, and logistical services, and military, intelligence and diplomatic support to the Saudi-led coalition. Without this support, the coalition could not carry out the war. Yet the UK also claims not to be party to the war, and regularly boasts that it operates one of the most robust arms export control regimes in the world. UK arms export policy is clear: the government will not issue arms export licences where there is a clear risk the weapons might be used in serious violations of international humanitarian law. The UK is also a major bilateral aid donor to Yemen. It’s the fourth largest donor to the UN Humanitarian Appeal for Yemen after Saudi Arabia, UAE and Kuwait – all members of the coalition currently pummelling Yemen to within an inch of its life.

How are we to make sense of these seemingly competing and contradictory claims? How can the UK government claim not to be involved in the war while materially facilitating it? How can it claim to uphold international law while promoting arms sales that actively undermine it? The government is not simply ignoring its commitments to international law. It is not the case that the government is merely failing to implement its own rules that require a risk assessment to check whether arms exports might contribute to serious human rights or humanitarian law violations. Instead, something more complicated is going on: rather than assessing risk in order to prevent harm, the government is actively mobilising risk in order to facilitate and legitimise arms exports. It does this in three main ways.

First, through an active strategy of not knowing about violations of international law. Without knowing that there have been breaches of international humanitarian law, the UK government deems the risk of future violations not to be clear. Hence there is no need to refuse arms exports. Second, through claims of unintended harm: the UK government claims that if excessive civilian harm does seem to have happened, it must have been accidental – a strategy to mitigate the demands of international law and manage the reputation of a friendly state, Saudi Arabia. And third, state actors mobilise a temporal claim that even if there have been violations of international law in the past, the risk of future harm is not clear.

Overall, the effect of these practices is to make negotiable the limits of what is deemed legally and normatively permissible. In short, the UK government is making risk not matter, so that it can continue to sell weapons to the Saudi-led coalition while claiming to be on the right side of international law and of history.

Featured image credit: Image by David Mark from Pixabay.

The post How the UK is facilitating war crimes in Yemen appeared first on OUPblog.

January 29, 2020

How far can a flea jump?

Stinging and gnawing insects are not only a nuisance in everyday life; they also harass etymologists. Those curious about such things may look at my post on bug for June 3, 2015. After hovering in the higher spheres of being (eat, drink, breathe: those were the subjects of my most recent posts), I propose to return to earth and deal with low, less dignified subjects. For now, I’ll say what I know about insects and will begin with flea. A curious fact: flea is a common word with solid cognates, and no secure etymology! I have 26 citations on flea in my database, not counting, of course, the entries in numerous dictionaries. As we will see, this embarrassment of riches will fail to produce a definitive result. A mountain can give birth to a mouse, but, apparently, not to a flea.

Here is our protagonist in its full glory. Image via Wellcome Images, CC by 4.0.

Here is our protagonist in its full glory. Image via Wellcome Images, CC by 4.0.The word has been known since the oldest period: Old Engl. flea(h), Old High German flōh, and so forth. The protoform must have sounded approximately as flauh-. One would expect that this form meant “to jump” or “to sting,” or “black.” Unfortunately, such clues lead almost nowhere. It is only easy to notice that in other languages this insect has a similar name: Latin pūlex, Greek fýlla, Russian blokha (stress on the second syllable), etc. The worst part in that list is etc., because the flea may have approximately the same name even outside the Indo-European family.

I am not sure when this fact was first noticed. In my database, the earliest citation along such lines goes back to 1923. Hermann Güntert, at one time an active and highly respected researcher, compared Latin pūlex with Korean pyårak. If we take into account the confusion of l and r in Korean, the form begins to look almost the same. Günter’s article has a characteristic title, namely “Concerning the Homeland of the Indo-Europeans.” Korean is of course not an Indo-European language, so that the question was about the original territory of the Indo-Europeans, who did not inhabit the Far East.

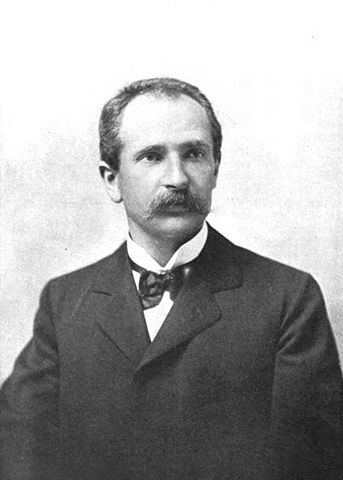

Alfredo Trombetti. From the journal The Critic, v.47 (1905). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Alfredo Trombetti. From the journal The Critic, v.47 (1905). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The Indo-Europeans lived in contact with the speakers of other language families. Moreover, for a long time some linguists have pleaded for a single origin of all the languages of the world. In a way, this idea returns us to the story of the Tower of Babel, but that story has not been supported by “hard evidence,” while Alfredo Trombetti (1866-1929), the scholar who argued for the monogenesis of all languages, wrote numerous works in defense of this idea. Unfortunately, he wrote all of them in Italian, a language not widely read outside Italy, and none of his articles and books have been translated into French, German, or English. His works are hard to find even in good libraries outside Italy, though now quite a few of them are available on the Internet. Since his time, a branch of scholarship, known as Nostratic linguistics, has become prominent. In light of the Nostratic hypothesis, a word known over such a vast territory does not look like an exception.

But is there a chance that flea has a more geographically limited etymology? We notice that it begins with fl-, to which pl– corresponds outside Germanic, and both sound groups play an outstanding role in the formation of sound-imitative words. Fly, flow, flicker, flutter, flimsy, (snow)flake, and Latin fluere “to flow” refer to movement, often unsteady. Fly is especially interesting, because we have the verb fly and the noun fly, the name of another insect. No doubt, the fly got its name because it can fly—at first sight, too vague a name, because mosquitoes, gnats, and many other creatures can also fly. It would be more natural to call a bird “fly”! Can flea be simply one of such fl-words? Perhaps so, though such an etymology would be too general to carry conviction.

Goethe thought of what happened if fleas were raised to a position of power. Music from “The damnation of Faust”, 1880s. Public domain via Flickr.

Goethe thought of what happened if fleas were raised to a position of power. Music from “The damnation of Faust”, 1880s. Public domain via Flickr.Flat also begins with fl-. The flea is rather flat, but flatness is certainly not its most conspicuous feature. Yet Ukrainian has the word bloska “bedbug,” whose etymology is uncertain: perhaps it goes back to the root of the Slavic word for “flat” (Russian ploskii, etc.) or to some root meaning “to squeeze.” Francis A. Wood, whose opinion I often mention in this blog, seems to have traced flea to the idea of quick movement or of being able to detach itself from the place where it rests, and cited many words glossed as “bast; ravel out; pluck, pull; hairs; snowflakes,” and so on. This list is not particularly impressive. Wood concluded that flea and fly share the same root, but this is tantamount to saying that fly and flea are fl-words (with all the implications of this thesis), which they certainly are, but too many questions remain unanswered.

Etymological dictionaries have nothing to say about the origin of flea. They list the oldest form and a few unquestionable cognates. This information can be translated into the familiar sad formula: “Origin unknown.” Even Hensleigh Wedgwood, the most active English etymologist of the pre-Skeat era, never at a loss for some distant parallel or ingenious suggestion, offered the shortest entry in his thick dictionary (of which four editions exist): “German Floh.”

We should return to the beginning of our story. Old Germanic had flauh-, Russian has blokha; next to them we find Latin pūlex and Greek fýlla. Incidentally, in Celtic, among other forms, floh and floach turned up! Even a beginning student of language history will notice that the correspondences according to The First (Germanic) Consonant Shift have been violated, as also happened when we put Engl. flow and Latin fluere side by side. Celtic fl- cannot correspond to Germanic fl-. Latin p and Greek f do not form a union. Russian bl– is irreducible to pl– of fl-. Korean pyårak is an odd man out. Faced with this puzzling diversity of forms, we find the long discussion about whether Russian blokha and Germain flauh– belong together rather uninteresting. In the list above, nothing belongs together, though everything resembles everything else. Consequently, a search for some protoform, with reference to Indo-European, will hardly yield convincing results.

I will restrain from a binding suggestion. The flea, as I have read, can catapult over a distance up to 200 times of its body length. Its etymology seems to have lived up to the insect’s abilities. It looks as though we have an ancient name, whose place of origin may be beyond discovery. This name traveled far and wide and assumed different forms, which are amazingly similar.

To complicate our task of finding the etymology of flea, one more factor should be taken into consideration. The names of dangerous creatures have been subject to taboo: people were afraid to call a flea a flea for fear that it would hear, consider the word an invitation, and pay a visit (the same fear plays an important role in the way people named wolves, bears, and other wild animals). To put it differently: there may have been a common Indo-European word for “flea,” but it was garbled intentionally, to ward off the vermin. Between such propositions (an itinerant word, or Wanderwort, as the Germans call it, and a dimly defined Eurasian name of a dangerous insect) we may never know how the story began: just some sound imitative or sound symbolic bl-/ pl-/ fl– formation with an arbitrary vowel to follow? To alleviate your fears, look at the picture of a flea market in the header: the place is only moderately dangerous.

Featured image credit: “Whitechapel Street Market” by TheeErin, CC-by-SA 2.0, via Flickr.

The post How far can a flea jump? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers