Oxford University Press's Blog, page 161

February 19, 2020

Nine books to read for Black History Month [reading list]

The month of February has been

Thomas Jefferson received a letter with strange markings on it on 3 October 1807, which were later determined to be Arabic script from enslaved Africans. This book expands our understanding of African American history as well as the history of religion in America.Exposing Slavery: Photography, Human Bondage, and the Birth of Modern Visual Politics in America by Matthew Fox-AmatoThe emergence of photography in America inaugurated a new era of visual politics for a country divided by slavery. A variety of actors utilized this new technology to push their vision of a future.Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America by W.Caleb McDaniel

Henrietta Wood was born into slavery and then legally freed in Cincinnati in 1848, only to be later abducted and sold back into slavery five years later. She would remain enslaved until after the Civil War. After regaining her freedom, she sued her kidnapper and eventually won her case and reparations for damages. Madness in the City of Magnificent Intentions: A History of Race and Mental Illness in the Nation’s Capital by Martin Summers

From its founding in 1855, St. Elizabeths Hospital was the country’s main center to care for and treat the mentally ill. The hospital was also one of the first to accept black patients, and the author examines the history of the development of modern psychiatry and its intersection with race at this unique institution. Reconstruction: A Very Short Introduction by Allen C. Guelzo

In this account by an eminent scholar of the period, Reconstruction is expanded to include the American West as well as the South. Guelzo also examines developments in philosophy, literature, law, and economy that parallel those in the political realm. Slavery and Class in the American South: A Generation of Slave Narrative Testimony, 1840-1865 by William Andrews

Among enslaved African Americans, some experienced degrees of relative freedom in comparison to others. This book examines these social strata through the literary genre of the slave narrative. Promises to Keep: African Americans and the Constitutional Order, 1776 to the Present, Second Edition by Donald G. Nieman

This groundbreaking work argues that conflict over the place of African Americans in US society has shaped the Constitution, law, and our understanding of citizenship and rights. The second edition incorporates insights from the last 30 years, including the War on Drugs and the Black Lives Matter movement.

It is impossible to fully grasp American history without black history. You can explore more materials from Oxford related to Black History Month here.

Featured image credit: “The African American History Monument, completed in 2001 on the state capitol grounds in Columbia, the capital city of South Carolina” by Carol M. Highsmith. Public Domain via The Library of Congress.

The post Nine books to read for Black History Month [reading list] appeared first on OUPblog.

February 16, 2020

Five philosophers on the joys of walking

René Descartes argued that each of us is, fundamentally, a thinking thing. Thought is our defining activity, setting us aside from animals, trees, rocks. I suspect this has helped market philosophy as the life of the mind, conjuring up philosophers lost in reverie, snuggled in armchairs. But human beings do not, in fact, live purely in the mind. Other philosophers have recognised this, and connected our inner lives with an everyday, bodily process: walking. The act of putting one foot in front of another creates rhythm, movement, and can elevate the spirit. From teaching to reflecting, here are some suggestions for your next stroll.

1. Aristotle: Walk and talk.

Aristotle was named a peripatetic, one who paces, for his habit of strolling up and down whilst teaching. For Aristotle, walking facilitates talking – and, presumably, thinking. Although Aristotle’s walking was famous, he was not the first philosopher to have the habit. Socrates was delighted at how students trailed after their teacher, as reported in Plato’s Protagoras: “I saw how beautifully they took care never to get in Protagoras’ way. When he turned around with his flanking groups, the audience to the rear would split into two in a very orderly way and then circle around to either side and form up again behind him. It was quite lovely.” Comedy writers of the time also made fun of Plato for tiring out his legs whilst working out “wise plans.”

2. Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Examine everything in your own time.

For Rousseau, the great benefit of walking is that you can move at your own time, doing as much or as little as you choose. You can see the country you’re travelling through, turn off to the right or left if you fancy, examine anything which interests you. In Emile, he writes: “To travel on foot is to travel in the fashion of Thales, Plato, and Pythagoras. I find it hard to understand how a philosopher can bring himself to travel in any other way; how he can tear himself from the study of the wealth which lies before his eyes and beneath his feet.” He adds that those who ride in well-padded carriages are always “gloomy, fault-finding, or sick,” whilst walkers are “always merry, light-hearted, and delighted with everything.”

3. Henry Thoreau: Allow nature to work on you.

Thoreau argues that humans are a part of nature, and walking through nature can allow us to grow spiritually. He argues that being in the wild can act on us, that mountain air can feed our spirits. In his article, “Walking,” he advises us to focus: “I am alarmed when it happens that I have walked a mile into the woods bodily, without getting there in spirit… What business have I in the woods, if I am thinking of something out of the woods?” To feel the benefits of walking through nature, we must allow it to enter us, to soak it up.

4. George Santayana: Reflect on the privilege of movement.

Santayana points out that plants cannot move, whilst animals can. In “The Philosophy of Travel”, he wonders if this privilege of “locomotion” is the “key to intelligence”, writing: “The roots of vegetables (which Aristotle says are their mouths) attach them fatally to the ground, and they are condemned like leeches to suck up whatever sustenance may flow to them at the particular spot where they happen to be stuck. Close by, perhaps, there may be a richer soil or a more sheltered or sunnier nook but they cannot migrate, nor have even the eyes or imagination by which to picture the enviable neighbouring lot.” Moving around allows animals to experience more of the world, to imagine how it might be elsewhere.

5. Fr é d é ric Gros: Hear the silence.

Gros has done more than any other philosopher to advance the philosophy of walking, although according to this amusing interview he does not walk enough. He maintains we should walk alone, preferably through nature. Once you’ve left populated streets, roads, and public spaces behind, you leave their noises behind. No more speed, jostling, clamour, clattering footsteps, white noise murmurs, snatches of words, rumbling engines. As he notes in “A Philosophy of Walking,” gradually, you retrieve silence: “All is calm, expectant and at rest. You are out of the world’s chatter, its corridor echoes, its muttering. Walking: it hits you at first like an immense breathing in the ears. You feel the silence as if it were a great fresh wind blowing away clouds.” The silence gathered by walking is refreshing, restorative.

Throughout the ages, and for different reasons, we have been encouraged (sometimes urged!) to step outside and explore the world by foot. Whether to clear our heads, to gain new perspective, or simply to absorb the wonders of nature, perhaps there is something for everyone to gain by slipping on a pair of shoes and venturing forth into the great beyond.

Featured image credit: Dmitry Schemelev on Unsplash.

The post Five philosophers on the joys of walking appeared first on OUPblog.

February 14, 2020

How dating apps reflect our changing times

As we look forward to explore what’s next in love and sex, it makes sense to examine to the heart. That which lovers have once worn on their sleeve is now being navigated in the palm of our hands. With mobile devices and apps letting us literally explore desires with our fingertips, as social scientists we are in a new frontier in which to examine who we pursue for love, and why. Is this the end of romance, or the beginning of a new way to love and connect to one another?

With over 1,500 dating apps on the market, many have come to the conclusion that the romance of courtship has been replaced with fantasy and heavily-edited Instagram photos. Along with driving this increase in dating apps, the millennial generation is also delaying marriage and moving away from conventional religious practices. Because of this, many popular magazines and TV shows suggest that hook-up culture dominates contemporary pursuits of love. Right-swiping, label free, highly educated, and technologically savvy, today’s young people appear to pursue sex frequently and do so on their own terms. There also appears to be much more equal footing between genders than ever before.

Anyone can download a dating app and begin swiping left or right within minutes, it does not seem to mean that more people are having sex. In fact, 15% of 20 to 24 year olds born in the 90s reported no recent sexual partners compared to 6% of Gen Xers (when they were the same age). This is likely more about our current cultural climate and less of a generational difference. Recently researchers found out that across all generations, reported frequency of sex appears to be falling compared to even two years ago. Even the Washington Post recently suggested Americans are having a sexual dry spell, opaquely insinuating that desire has been replaced with student loan debt and existential peril.

Economic anxieties aside, we have to wonder: If connecting to one another is easier than ever, why are we more likely than ever to keep our hands to ourselves?

It may be that the dry spell is not a dry spell at all, but a sexual recalibration. Some scientists suggest that less sex doesn’t reflect relationship satisfaction or overall happiness. In fact, less sex could mean that people having healthier “sex diets,” partly driven by people’s increased ability to apply selective criteria to potential romantic partners.

Accelerating this growing desire for romantic discernment may be the advent of new and specialized dating apps. Instead of relying on a friend’s opinion on a potential romantic partner after a few drinks at the bar, you can now enlist your friends through the app Wingman to peruse potential romantic partners for you and select what they think is your best match. This makes us more selective about who we ultimately meet in real life, decreasing the need to go to out and nervously introduce yourself to a potential suitor sitting across the room.

However, this increased discernment means that some people aren’t having much sex, but other people are having most of the sex, especially heterosexual individuals. A recent study analyzing swipes and likes on Tinder showed that the top 20% of men, in terms of attractiveness, were pursued by the top 78% of women. What this suggests is that the online dating market is heavily unequal in terms of who is most likely to receive attention from the opposite sex. It is not surprising then to see the decline in sex in the overall population is being led by a particular proportion of young men. Even the dating market experiences its own versions of economic inequality.

But these statistics aren’t meant to dissuade a longing lover from trying his or her hand at meeting a potential romantic partner. In fact, technology may be providing new tools for connection that have never existed before. A new site called Dating-Bots allows programmers to upload specially trained bots for the public to use that can be deployed on a number of different dating sites. These bots then chat with potential suitors using dialogue that has been statistically tested to garner the most replies or phone numbers. These bots promise to “take your love life to the next level” while “teaching you how to flirt” and “helping you select the best match.”

Ultimately, dating apps are developing based on our prurient interests in finding the best possible mate for our current market value in the dating market. Some apps help to give people the best chances for achieving that, while others may make it easier for those with the most desirable qualities to be selected at higher rates than ever before. However, like most markets, in time there will be more parity as new tools emerge for connecting different types of romantic partners.

What this all means for researchers is that to understand sexual behaviors, we must look at the economy, culture, and technological changes together to understand changes in overall averages of sex rates and habits. While online dating is most likely not the cause of a Dating Apocalypse, it is likely a telling window into the hearts, minds, and libidos of our ever-evolving American culture.

Featured image by Rob Hampson via unsplash

The post How dating apps reflect our changing times appeared first on OUPblog.

February 12, 2020

An etymologist is not a lonely hunter

The posts for the previous two weeks were devoted to all kinds of bloodsuckers. Now the time has come to say something about hunters and hunting. The origin of the verbs meaning “hunt” can give us a deeper insight into the history of civilization, because hunting is one of the most ancient occupations in the world: beasts of prey hunt for food, and humans have always hunted animals not only for food but also for fur and skins.

When lions hunt antelopes and fleas hunt dogs, they do not reflect on the results of their actions, while people take hunting seriously. In the remote past, they could not draw a line between humans and animals and endowed beasts with the same capacity for reasoning they themselves had. They wanted to explain to their prey why they had behaved so cruelly toward it, apologize, and, if possible, propitiate the masters of the creatures they hunted.

Primitive hunting. Hunting Bison in USA by George Catlin, 1844. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Primitive hunting. Hunting Bison in USA by George Catlin, 1844. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.This approach also had a practical side. Killing a bear, for example, was believed not only to enrage other bears; it diminished the chance of being successful a year later, because, when the next hunting season came to an end, it was understood that the bear brought home was the same one they had killed earlier: reborn. To ensure the bear’s rebirth, elaborate feasts were celebrated. All this is known from the descriptions made by ethnographers, and, obviously, such rites go back to the hoariest antiquity. The words for “hunt” had the status of religious terms, and they are sometimes notoriously hard to etymologize.

One of the reasons for the difficulty is that sacral terms were not supposed to be pronounced “in vain” and often fell victim to taboo. For example, the real verb might be “to kill,” but it would be distorted or replaced by a gentler or vaguer synonym or even by a word of the opposite meaning. One of such words is German jagen “to hunt.” It occurred in the oldest period; yet the few attempts to explain its derivation resolve themselves into “intelligent guessing.”

Another important German word is Weidmann “hunter,” probably not related to weiden ”to graze.” The corresponding old verb was weidenen “to hunt.” It resembles Engl. win, from winnan, and Latin vēnāri “to hunt.” (From the root of the Latin verb English has venery “the art of hunting” and venison “the flesh of an animal killed in the chase”: such an animal was in the days of Robin Hood the deer, and that is why the Germanic word for “animal,” such as German Tier, has acquired the meaning “deer.”) But winnan seems to have meant “to toil; suffer,” that is, “to attain something after hard and painful struggle” (so in Gothic, a Germanic language recorded in the fourth century).

The contours of this picture become blurred, because next to win we find Latin venus “love” (hence the name Venus, and compare Engl. venerate, venerable, and alas, venereal). The root must have meant “to desire,” and it is usually said that Germanic winnan and Latin venerāri are reflexes of the same protoform, but that in Germanic, the verb acquired a specific meaning (“to struggle” or “to suffer”). However, they may have been homonyms.

What concerns us here is Latin vēnor “to hunt” (compare vēnātor “hunter”). The verb hardly referred to toiling and suffering. It was rather a taboo word: one “loved” one’s prey. The word hid the hunter’s intention and turned killing into its opposite (as far as the language was concerned). The love-hunt symbiosis has a close parallel in Slavic: thus, the Russian for “hunt” (noun) is okhota (stress on the second syllable), its root (khot-) means “to want, wish.” Incidentally wish, a cognate of German Wunsch (the same meaning), shares the root with win. Thus, the Slavic hunter is a “wisher,” who “desires” (“loves”) his prey, a close semantic relative of the Latin vēnātor.

Fox hunting, until recently, a favorite pastime of the British leisured class. Foxhunting: Clearing a Ditch by John Frederick Herring, Sr. 1839. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Fox hunting, until recently, a favorite pastime of the British leisured class. Foxhunting: Clearing a Ditch by John Frederick Herring, Sr. 1839. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.All this should be enough to show where etymologists cast their net in the hope of understanding the origin of the verb hunt. Perhaps the most revealing parallel for us is Engl. to hunt versus French chaser (the same meaning). The words of the modern Romance languages for “to hunt” and “hunter” do not continue Latin vēnor and vēnātor. For example, French has chasser and chasseur. The Latin verb sounded as captare “to chase,” and Engl. chase, borrowed from French, is, obviously, related to the same verb. The simplest word that will interest us is Latin capere “to take, seize.” English is full of borrowed words containing its root: captious “catching of faults,” captive, captivate, and so forth. Engl. chase goes back to the same root and is an etymological doublet of catch.

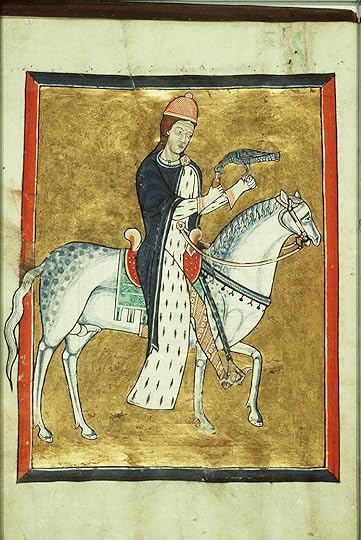

Falconry played an outstanding role in the life of the medieval aristocracy. It left some traces in the modern last names. Search for the sculptures of Étienne Maurice Falconet and read or reread Prosper Méremée story ‘Matteo Falcone’. May: a falconer. Public domain via The European Library and the National Library of the Netherlands.

Falconry played an outstanding role in the life of the medieval aristocracy. It left some traces in the modern last names. Search for the sculptures of Étienne Maurice Falconet and read or reread Prosper Méremée story ‘Matteo Falcone’. May: a falconer. Public domain via The European Library and the National Library of the Netherlands.Can it be that hunt, too, once meant “to catch, to seize”? The verb has existed for centuries: its Old Engl. form was huntian, and it seems to be related to hentan “to seize”; hent can still be found in the largest dictionaries of Modern English, marked as obsolete or dialectal. A moderately promising cognate outside English turns up only in Gothic. Outside Gothic, we draw a blank. Icelandic has veiða, a cognate of Germ. weiden, mentioned above. The modern Scandinavian languages borrowed Germ. jagen, while Frisian and Dutch have its close cognates. Greek has gone its own way and used compounds for “hunting.” The seemingly relevant Gothic verb is –hinþan “to take captive.” However, hunt ends in t, rather than th or d. To explain away this inconsistency, two parallel roots—kent and kend—have been reconstructed (a typical face-saving trick, or, to use a more dignified term, an ad hoc explanation).

To complicate matters, the Gothic verb and its obvious cognates, such as Old Engl. hūþ “booty,” are items of the military vocabulary, whereas hunt is not: it usually emphasizes the result of pursuing, catching, obtaining, and the object of prey is the catch, not a captive. Hunt has often been traced to the root of hand. Once again we have the t ~ d problem, and the semantic bridge is also weak: the hunter’s prey is not caught manually. Viktor Levitsky, to whose Germanic etymological dictionary I have referred in the past, traced hunt to the root (s)kent “cut” (with s-mobile, the villain of many earlier posts), with the well-attested development “cut”—“draw a line”—“seize.” He did not exclude the connection between hand and hinþan, but admitted that the problem of d ~ t had never been resolved.

None of the conjectures mentioned above looks particularly impressive. Even the closeness of hunt to hent may, and probably is, due to chance (hint surfaced in texts only in the seventeenth century, and its origin is obscure: a variant of hent?). Predictably, it has been suggested that hunt is not an Indo–European word, but rather a relic of some substrate language. However, one wonders why the speakers of Old English, in whose language there may have been cognates of German weidenen and jagen, needed a borrowing, obviously not from Celtic or Latin, but from Pictish, whose influence on English is minimal, and all that for one of the most useful and common verbs in their vocabulary. Did the speakers of that mysterious substrate language teach the invaders a rare and especially efficient way of hunting? In the extant books, there should have been some references to this method. Is hunt the product of taboo? The verb hurt seems to have been coined in Germanic. Could hunt be a deliberate distortion of hurt? Another arrow shot into the air. We can see that many people have tried to disclose the remote past of the word hunt—unfortunately, with moderate success, but it is always a pleasure to share a sportsmanlike spirit with other worthy people. “Home is the sailor, home from the sea, and the hunter home from the hill.”

Hunters like telling tall tales. In this picture by Vasily Perov (1833-1882; stress on the second syllable), you can see one of such scenes. Its Russian title (“Zavralsia”) means approximately: “Lost in His Own Lie”; two hunters give their companion the lie. 1871. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Hunters like telling tall tales. In this picture by Vasily Perov (1833-1882; stress on the second syllable), you can see one of such scenes. Its Russian title (“Zavralsia”) means approximately: “Lost in His Own Lie”; two hunters give their companion the lie. 1871. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Featured image credit: Female lion versus buffalo at Serengeti National Park by Demetrius John Kessy. CC-by-2.0 via Flickr. Image has been cropped to fit.

The post An etymologist is not a lonely hunter appeared first on OUPblog.

February 11, 2020

How to teach history better

These days, we often hear of a crisis in the discipline of history. It’s not a crisis of research. To be sure, there are debates and disputes over new methodologies, theoretical frames, the price and speed of publication, and even the relative value of publishing in public, digital, and traditional media. There is also the ever-present absence of funding. These are long-standing, ongoing issues, but they are not the crisis at the forefront of the discipline.

Instead, the current crisis is in the teaching of history. In two seemingly contradictory (but actually complementary) trends, student enrollment and interest is falling while oversight from administrative and even legislative bodies climbs. Across the United States, and in many other countries, fewer history courses are offered and required at the college level. Where students have the choice at the high school level, interest levels are falling as well. At the same time, however, both local administrations and state governments are seeking increasing oversight as to what is taught in those courses.

There are many contributing causes to this crisis. It may be partly a result of changing student demand in an era of hard-nosed pragmatism, a societal turn away from the Humanities and towards STEM, or the struggles of departments to respond to shifting student demographics and skills. It may result in part from inattention to social studies in primary schools (in favor of reading and arithmetic) and a lack of direction at the high school level. Or, we might muse, it may be a consequence of some failure within the discipline to make our case – to students and parents as well as society at large – for the significance of thinking like a historian and studying the past. Whatever the causes, these changes derogate from historians’ capacity to provide our unique contributions to American society.

But while threatening, crises can also be highly generative, and the current situation is no exception. There is evidence that across the country, individual historians and collaborative projects are generating new models and approaches for the teaching of History. Designed around core competencies, and, in many cases focused on an enquiry model, these projects vary in approach but seek to make use of advances and findings from cognitive sciences as well as the adoption of computer and web-based technologies.

Two long-standing projects – Stanford History Education Group’s Reading Like a Historian and World History For Us All – have been joined by a number of newer collaborative projects. UC Berkeley’s online world history cohort has brought together eight community college instructors to build two exemplary online introductory courses. Washington State University’s Roots of Contemporary Issues courses promote a skills-based focus on usable history. History for the 21st Century is a funded project aimed at supporting the development of open access, educative curriculum for introductory courses. Faculty at Framingham State University have collaborated to develop a modular system introducing vital historical thinking and writing skills. There are other examples. Most are based in individual institutions or the product of small groups of collaborating faculty, but the American Historical Association has assumed a leadership stance with its History Gateways project, aimed at stimulating conversation about curriculum and pedagogy in first-year college courses. Similarly, Gates Ventures has invested deeply in OER world history courses for the High School level.

Of course curricular and pedagogical experimentation has happened before in our discipline. Bob Bain, professor of educational studies and history at the University of Michigan, has tracked the history of these kinds of efforts to reform education from the 1883 work of G. Stanley Hall through the Amherst Project of the 1960s, which aimed to produce modules for high school history courses complete with everything a teacher would need. Although it is difficult to measure precisely, in Bain’s evaluation these projects seem in general to have had little lasting impact.

Things seem different this time. The crisis in teaching translates directly into economic facts that cannot be ignored, as evidenced by a decline in both the number of students enrolled in history courses and the number of history majors, a situation which is aggravated by curricular interference from administrators and state legislators. Many departments are seeking ways to remedy these issues instead of simply being victimized by them. Again, this is not the first time such efforts have been tried. But today, the wide availability of new digital technologies makes possible widespread collaboration in the production of new materials, simplifies their discovery and sharing by instructors, and could possibly revolutionize the practice of teaching as well. People can build, test, and share material rapidly. This was not the case in 1883 or the 1960s.

Yet to be really effective and to scale such efforts dramatically, historians need to do more work outside the classroom as well. We need to be more introspective and consequential about the results of our teaching—we need to assess new projects for efficacy and make the findings made public to contribute directly to even better approaches built on that learning. Academics need to pay more attention to lessons we can learn from teachers, in particular those in secondary education. At the same time, universities – including major research universities – need to truly deliver on their promises to emphasize teaching, including making changes to systems of reward such as tenure for individuals and the awarding of lines or positions for departments.

Whether or not such changes will solve the current crisis in history education is unclear, but even if they do not drive enrollments, they should be embraced. If we’re not to be teaching more, we can at least teach better.

Featured image: by Gibson, J. (John) via Wikimedia Commons

The post How to teach history better appeared first on OUPblog.

How to diversify the classics. For real.

As (I hope) Barnes and Noble and Penguin Random House have just learned, appropriating the concept of diverse books for an opportunistic rebranding insults the idea they claim to honor.

If you were off-line last week, here’s a brief recap. The bookseller and publisher announced (and then abandoned) plans to publish “Diverse Editions” – not books by writers of color or from minoritized communities, but a dozen classic books with new cover art depicting the protagonists as ethnically diverse. An African American Ahab on Melville’s Moby Dick, a black Peter Pan on Barrie’s book.

As Michael Harriot wrote in The Root, “They put their books in blackface.” Within 48 hours of the announcement, widespread criticism prompted them to cancel the project.

If booksellers and publishers truly want to diversify the classics, here are some better suggestions.

You want to rethink a white-authored classic? Rather than decorating Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) with a brown Alice, try L.L. McKinley’s A Blade so Black (2018), in which an ass-kicking African American Alice from Atlanta navigates the Nightmares of Wonderland. Instead of publishing Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) with a brownface monster on the cover, promote Victor LaValle and Dietrich Smith’s Destroyer (2017), a contemporary graphic-novel retelling that explores how racism makes monsters. Christina Orlando and Leah Schnelbach have assembled a great list of “23 Retellings of Classic Stories from Science Fiction and Fantasy Authors.” Start there.

Another way to rethink the classics: Put them in dialogue with works by authors of color. To counter the allegation in the final third of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) that enslavement is one big joke, booksellers could create a display pairing Mark Twain’s novel with Julius Lester’s To Be a Slave (1968), where readers will find first-hand accounts of living quarters “more fit for animals than human beings,” mothers who killed their own children rather than allowing them to be sold, and ways that the enslaved resisted their white jailors. Or they could pair Twain with speculative works that render with precision the physical and psychic traumas of slavery: Zetta Elliott’s A Wish After Midnight (2010), Octavia Butler’s Kindred (1979) and its recent graphic-novel adaptation (2017).

Publishers and booksellers might — as the We Need Diverse Books organization suggests — champion “new editions of classic books by people of color and marginalized people, particularly if those books have been largely ignored by the canon.” Need recommendations? Instead of consulting the company’s chief diversity officer, ask experts. Marilisa Jiménez García, a scholar of Latinx literature at Lehigh University, recommends the Nuyorican writer Nicholasa Mohr’s Nilda (1973), “the first novel by a Latina.” Professor Sarah Park Dahlen, co-editor of the journal Research on Diversity in Youth Literature, suggests Yoshiko Uchida’s Journey to Topaz (1971) “for the important work it does to inform young readers of the racist incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.” Katharine Capshaw, a scholar of African American children’s literature at the University of Connecticut, proposes June Jordan’s His Own Where (1971), “a poetic young adult novel about two teenagers in love, which was nominated for a National Book Award.”

There are many experts who can give you good ideas. Ask them. Or, better, hire them as consultants.

Instead of commissioning new covers, publishers might commission restoried versions. As Ebony Elizabeth Thomas’s The Dark Fantastic (2019) explains, restorying happens when readers take ownership of and rewrite the stories they hear: “they not only imagine themselves into stories,” she writes, “but also reimagine the very stories themselves.” Rather than creating a new cover, ask a writer from one of the southern Pacific islands what Moby-Dick might look like told from the perspective of Queequeg. Or ask an African American writer to reimagine the story from Pip’s point of view. For any classic, ask what narratives emerge when we instead center the characters who Thomas calls the “Dark Others”?

Finally, and most importantly, you can create diverse classics simply by featuring diverse books. The works of Cherie Dimaline, N.K. Jemisin, Nnedi Okorafor, and Elizabeth Acevedo become classics when publishers promote them, teachers include them in their classrooms, librarians recommend them to patrons, and people read them. Erika L. Sanchez, Emily X.R. Pan, and Hanna Alkaf — whose debut YA novels appeared in 2017, 2018, and 2019, respectively — get to write second novels when bookstores feature their work and readers buy it.

Classic diverse novels are being written right now. Help readers find them.

Featured Image Credits: by maxmann via Pixbay

The post How to diversify the classics. For real. appeared first on OUPblog.

February 10, 2020

Why the Great Recession made inequality worse

Many compare the Great Recession to the Great Depression for its severity and scale. Yet, a decade later, it is clear that their consequences on the distribution of economic resources in the United States cannot be more different.

The decades following the Great Depression substantially reduced the wealth of the rich and improved the economic wellbeing of many workers.

The Great Recession, in contrast, has exacerbated both income and wealth inequality. The mortgage crisis eroded the wealth of middle- and working- class families, who tend to invest most of their savings in housing. Meanwhile, the median wage remained stagnant until 2015. Since then, wage growth has been weak, despite record-low unemployment.

The crisis was not only wasted. It made the United States even more unequal. Why did the Great Recession exacerbate rather than mitigate inequality? Some have attributed this phenomenon to a weakened labor movement, fewer worker protections, alongside a radicalized political right wing.

This account misses the power of finance to rebound and overlooks its fundamental role in generating economic disparities.

The rise of finance represents a paradigmatic, regressive shift in how American society organizes economic resources. The increase in productivity first and foremost benefits the financial sector and investors. Growth became wed to heightened inequality.

The process through which financialization generates inequality unfolds in three primary ways. First, the financial sector creates extractive intermediaries that drain resources from other economic activities without providing commensurate benefit. Examples include mega banks, shadow banks, and corporate financial arms. Second, it loosens the codependence between labor and capital, allowing investors to profit without production. Third, the proliferation of financial products among American households are invariably regressive: poor households pay the highest interests and fees, while rich households reap the largest investment gains.

While the reforms during the Great Depression fundamentally restructured the financial system, the regulatory policies since the financial crisis largely were designed to restore a financial order that, for decades, has been channeling resources from the rest of the economy to the top.

Whereas the New Deal took a bottom-up approach and brought governmental resources directly to unemployed workers, the recent recovery was largely top-down and finance-driven. Governmental stimuli, particularly a mass injection of credit, first went to banks and large corporations, in the hope that the credit eventually would trickle down to families in need.

The banks and corporations first principle created a highly unequal recovery. Even though the financial crisis wiped out almost three-quarters of financial sector profits, the comeback was startling. Before the end of the recession in mid-2009, the financial sector had brought in a quarter more income than 2007. Profits continued to grow in the following years. In 2017, the sector made 80% more than before the financial crisis. Profit growth was much slower in the non-financial sector, which recovered in 2010 and grew 38% in 2017.

The gain in profit was in part due to losses in wages and employment. Labor’s share of national income dropped 4% during the recession. Yet, it remained low during the recovery.

The stock market fully recovered from the crisis in 2013, a year when the unemployment rate was as high as 8% and the single-family mortgage delinquency still hovered above 10%. The median household wealth, in the meantime, had yet to recoup from the nosedive during the Great Recession. In 2016, a typical American family owned 30 less wealth than it did in 2007.

The racial wealth gap only widened in the past decades. The median household wealth of white, black, and Hispanic households all dropped around 25% after the burst of real estate bubble. But white households recovered at a much faster pace. The difference was most salient between 2010 and 2013, during which white households stabilized their wealth but minority households continued in a downward spiral. By 2016, black households still lost about 30% of their wealth, compared to 14% for white families.

The massive corporate tax cut of 2017 did little to stimulate real investment but only fueled widening inequality. The conventional wisdom was that banks—as well as corporations and investors—knew how to put the credit into best use. And so, to provide liquidity and stimulate economic growth, the Federal Reserve increased the supply of money to banks by purchasing treasury- and mortgage-backed securities.

What the banks did, however, was prioritize their own interests over those of the public. They were hesitant to lend the money out to homebuyers and small businesses, since the money would then be locked into long-term loans that paid historically low interest. Instead, they deposited most of the funds and waited for interest rates to rise.

Similarly, corporations did not use the easy credit and tax cut to increase wages or create jobs. Rather, they took advantage of the low interest rate to finance stock buybacks, channeling other people’s money to top executives and shareholders.

What is good for the stock market is not necessarily good for American families. More than 80% of the stock market is owned by only 10% of Americans and by foreign investors.

In retrospect, it would have been more effective to channel these funds into policies similar to the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, which gave fiscal relief to state and municipal governments. But that was deemed politically infeasible under the market-oriented governing model dominating in the late 2000s.

In light of this unequal recovery, how robust is current economic boom? Despite promising economic statistics, analysts believe we are not far from the next recession. Many workers still experience job insecurity even in a booming labor market, and families are struggling to get by. A likely scenario is that the next economic downturn will hit before many American families fully recover from the Great Recession.

When it comes, we will have a decision to make.

We can either continue the trickle down approach to first protect banks, corporations, and their investors with monetary stimuli. Or, we can learn from the New Deal and bring governmental support directly to the most fragile communities and families.

Featured Image Credit: Wall St by Rick Tap on Unsplash

The post Why the Great Recession made inequality worse appeared first on OUPblog.

February 9, 2020

How to use maps to solve complex problems

Imagine that you’ve just been appointed the head of operations for a five-star hotel in Manhattan. Your boss calls you in her office on your first day and says: “Our biggest problem is how slow elevators are. Everyone complains about it, and we can’t have that. Speed them up.”

How would you do it?

Most people intuitively focus on speeding up the elevators: installing stronger motors, modifying the dispatch algorithm, getting the doors to shut faster, or even installing additional elevators. But there is also a whole set of options that consists of giving the impression that the elevators are faster, for instance by distracting the users with windows or, on the cheaper side, with mirrors, TVs, or newspapers.

Facing a complex challenge, it’s tempting to pursue whichever option we first identify and start implementing it quickly. But relying on this kind of intuitive thinking, particularly in unpredictable environments, might result in poor outcomes —even when we have a high degree of confidence.

Instead, we should first identify the range of solutions that are available to us, which is challenging, because we don’t know what we don’t know. It’s like being an explorer a few hundred years ago who would land on an uncharted piece of land having to decide how to explore it. Well, there is a time-tested approach: map it.

Facing that complex challenge, your first task should be to frame your problem in the form of an overarching question that, once answered, will lay out your proposed plan of action. A good way to frame your problem is to summarize that key question and its context in a situation- complication-question sequence. Once you’ve framed your problem, you should then think of alternative ways—or options—to solve it before deciding which one is on balance the best.

A question map helps you explore that universe of potential options. Question maps are similar to other knowledge cartography tools, such as mind maps, decision trees, and the issue trees that management consultants use. But question maps are also different from these tools in that they obey their own rules, four rules that actively drive structure into your problem-solving process.

1. Good question maps answer a single type of question

The first rule of good question maps is that they answer a single type of question. Facing a complex problem, we face two types of questions: why and how. A why question is problem centric; it helps you to diagnose your problem, uncovering its root causes and, ultimately, enabling you to summarize your problem in a more insightful key question. In contrast, a how question is solution centric: It enables you to consider all the possible solutions to your problem.

One type of question isn’t consistently better than the other. Both are useful and, in general, you want to ask why before you ask how.

2. Good question maps go from the question to potential options

The second rule of good question maps is just as simple: Start your map at your key question and explore all possible answers—the so-called solution space. This requires you to think in a divergent pattern. Vertically, use your map to uncover the various facets of your question, with each branch addressing a different dimension. Horizontally, use your map to go into more details eventually identifying concrete, tangible answers.

So, if your question is how you should make your clients happy with the speed of your elevators, you might start a map with two ideas: “by speeding up the elevators” and “by creating the impression that the elevators are faster.” You can then continue exploring these ideas into further and further details.

You should continue that divergent thinking pattern as long as doing so brings value. This will typically result in a map with dozens of ideas over at least five layers. For a why question, this progression in further depth is equivalent to the five-whys methodology—but don’t limit yourself to just five, if it makes sense to drill deeper, do so. Since it would be intractable to treat each one of these ideas as a separate option, you then converge by summarizing your entire map in a set of two to ten formal options.

3. Good question maps have a specific structure

Next, consider all the possible answers to your question exactly once. That is, give your map branches that are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive (or MECE). Giving your map this structure is a critical element of the process, and in most cases, it isn’t easy to do, as it requires you to think both creatively and critically. So, expect to spend some effort here—and by “expect to spend some effort,” I mean that if you don’t feel some frustration, you’re not doing it well!

4. Good question maps are insightful

The final rule of good maps is that they should have an insightful structure. That is, the structure should be both logically valid and useful. Concretely, this means finding a way to structure the map that helps bring some new, useful light into your question. This is especially important for the first cut, the top-most node of the map.

Striving to be insightful also means that you need to keep developing your map until you identify concrete answers. Don’t stay at a philosophical level (e.g., by just writing “by creating the impression that the elevators are faster”) but identify concrete ways to answer your question (“by installing mirrors in the elevators”).

Question maps only have four rules, and those are simple enough to understand. Following them when solving a complex problem, however, can be, let’s say, challenging. But realize that the complexity isn’t in the map; the complexity is in the problem, all that the map does is expose that complexity so that you can better address it. So, embrace the challenge, and happy mapping!

Feature image by Daan Stevens via Unsplash

The post How to use maps to solve complex problems appeared first on OUPblog.

February 8, 2020

The problem with overqualified research

Not all research findings turn out to be true. Of those that are tested, some will need to be amplified, others refined or circumscribed, and some even rejected. Practicing researchers learn quickly to qualify their claims, taking into account the possibility of improved measurements, more stringent analyses, new interpretations, and, in the extreme, experimental or theoretical error.

Qualification is routinely achieved by changing the form of the verb. Take this example from a physics article: “This lack of correlation may be due to the increased inhomogeneity expected for the MG method.” The authors’ use of “may” allows for the lack of correlation to be due to something else.

The softening of any statement with a word or words is called hedging. It can be accomplished in many ways. One has already been indicated—inserting an auxiliary modal verb, “may,” “might,” “can,” or “could.” Another common way is to add a mitigating phrase or clause such as “It is possible that” or “This suggests that.”

Unhappily, the temptation for an author is to keep accumulating hedges to secure progressively more protection against potential criticism. As a result, it becomes correspondingly harder for the reader to see what the author is actually claiming.

In these two sentences from a molecular biology article, there’s a doubling of hedges, here in italics: “it is possible that … G9a-mediated H3K9 and H3K27 monomethylation might serve as stimulating factors” and “Possible candidates might comprise Jarid2 and Snail1.” Both instances of “might” can be eliminated without affecting the provisional status of the claims.

Altogether this article contained 44 instances of “might,” “can,” “could,” “likely,” and varieties of “possibly,” but none of “may.” Because of its potential for ambiguity, some authorities advise authors not to use “may” when what’s being signalled is possibility instead of permission.

This next example is from an oncology article: It has five hedges in one sentence: “Although, on balance, testosterone might possibly be beneficial to the cardiovascular system, testosterone might also have some detrimental effects.” Two of the hedges can be safely eliminated; for example, “Although testosterone might be beneficial to the cardiovascular system, testosterone might also have some detrimental effects.” Yet with two opposing uses of “might,” the sense of equivocation remains, despite the restrictive “some.” Given that “might” is seen as being more tentative than “may,” a less equivocal version is “Although testosterone may be beneficial to the cardiovascular system, it might also have some detrimental effects.” Whether this edit is valid, though, needs expert judgement. In all, this article contained 54 instances of “might.”

There can be very good reasons for using “might” so often—but it’s unusual. I estimated its general frequency of occurrence from an analysis of a sample of about 1000 articles from the physical, life, and behavioural sciences, mathematics, engineering, and medicine. Across the sample, 50% of articles containing “might” used it just once or twice and only 1% used it as many as 21 times or more.

In a more detailed analysis, I also found that as the frequency of the modals “may,” “might,” “can,” and “could” increased in an article, the frequency of pairs of hedges such as “could indicate” and “possibly suggests” increased still more. The implication is that multiple hedges within a sentence are a response to the prevailing rate of protection within the article—rather like having to talk more loudly in a noisy restaurant.

Whatever the cause, hedging can clearly escalate. But there’s a countervailing force: the need to deliver impact, usually in the abstract or conclusion of an article—something to be remembered by the reader, a take-home message. Since impact is lessened by hedging, summary statements may succumb to under-qualification and go beyond what the data can safely support. At worst, they can lead to public correction and retraction of the article.

How, then, to choose the right amount of hedging? Every claim is unique to its particular context and it’s difficult to generalize. Even so, there’s some strategic advice, popularly attributed to Albert Einstein, that may be helpful. Applied to hedging, it’s this: Hedging should be as simple as possible—but never simpler. Although finding the right balance is another challenge, it at least encourages restraint.

Featured Image Credits: Julian Schöll on Unsplash

The post The problem with overqualified research appeared first on OUPblog.

February 7, 2020

Four reasons why the Indo-Pacific matters in 2020

If there is one place in the world that we need to keep our eyes on for a better understanding of the dynamics of international affairs in 2020, it is the Indo-Pacific region. Here are four reasons why.

1. T he Indo-Pacific is hard to define

Politically, the Indo-Pacific is still a contested construct in the making. Australia and the United States seem to share a similar geographic view on the Indo-Pacific, i.e. the original Asia-Pacific region plus India. However, Japanese and Indian geographic understandings are much broader, including two continents—Asia and Africa— and across two oceans—the Pacific and Indian Oceans. For the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, the concrete boundary of the region does not matter as long as the association retains its centrality in the future regional architecture.

China is a key player in the Indo-Pacific region, no matter how the geographical boundary is defined. However, China is reluctant to register itself to the Indo-Pacific. So far, no Chinese official document has used the term Indo-Pacific. In practice, however, China’s economic and strategic ambitions have straddled across the Pacific and the Indian Oceans, as we can see from the extensive scope of its Belt and Road Initiative. In other words, China has politically entered the Indo-Pacific without acknowledging it officially.

2. The Indo-Pacific matters to the US and China

The political contestation over the geographical construct reveals the strategic importance of the Indo-Pacific itself. The Indo-Pacific includes the world’s most populous state (China), the most populous democracy (India) and the most populous Muslim-majority state (Indonesia). Seven of the ten largest standing armies in the world can be found in the Indo-Pacific, and around one third of global shipping passes through the South China Sea alone. Therefore, as the United States government has claimed, “the Indo-Pacific is the single most consequential region for America’s future.”

For Chinese leaders, the single purpose of US emphasis on the Indo-Pacific concept and the Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy is to contain China’s rise. To a certain extent, the Indo-Pacific has become a new focal point of the US-China rivalry for the next decade or two. It is clear that the US-China competition will re-shape the strategic dynamics and international order in the region. All other states, especially Australia, Korea, Japan, the Philippines, and Thailand—US traditional allies, might have to take sides between the United States and China or choose between security protection and economic prosperity in the future if US-China strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific becomes extremely tense.

3. There are many potential flashpoints

Militarily, the Indo-Pacific is full of flashpoints that serve as potential sources of armed conflict. North Korea’s Kim Jong Un has refused to return to talks with United States although Trump sent birthday greetings to Kim personally. North Korea has vowed to show the world its “new strategic weapon” in 2020, which will be definitely a poke in the eye for the United States, and South Korea and Japan as well. Taiwan’s pro-independent Democratic Progressive Party won a landslide victory in both presidential and legislative elections in January 2020. Any pro-independent movement of the Democratic Progressive Party might fuel the nationalism flame in the mainland and drive Beijing into a corner. To make things worse, the United States will not remain idle if cross-strait military tensions heat up. Potential conflicts between the two nuclear powers will be a doomsday for the world.

In addition, the territorial and maritime disputes in the East China Sea and the South China Sea might be stirred up anytime as seen from the recent standoff between Indonesia and China in the waters near the Natuna islands in the beginning of 2020. China has strengthened its navy’s power projection capabilities by building its second aircraft carrier in 2019 while the United States conducted 85 military drills in the Indo-Pacific, especially in the South China Sea, according to a Chinese report. It is very likely that the Indo-Pacific, especially the South China Sea, will feature heightened US-China security competition and rivalry in 2020.

4. The Indo-Pacific is a major economic hub

Last, but not the least, the Indo-Pacific is at the centre of gravity of economic growth in the world. The three largest economies, the US, China, and Japan are all located in the Indo-Pacific. Therefore, the Indo-Pacific can be either a powerhouse or destroyer of world economy. According to the International Monetary Fund, the US-China trade war that started in mid-2018 has dragged the 2019 global growth to its slowest pace since the 2008-2009 financial crisis.

Besides the trade war, the more worrisome trends are the strategically driven decoupling and technological competition between the two economic giants, which will cause more collateral damages to other states in the region. One example is the Huawei 5G controversy, in which the United States has forced other states to take sides in the tech-war between the United States and China. In addition, the United States, Australia, Japan, and India have expressed strong interest in strengthening cooperation of their infrastructural initiatives as a countervailing measure against China’s Belt and Road Initiative influence. To be clear, any market-driven competition in infrastructure will definitely benefit all parties because it will increase efficiency, transparency, and sustainability of infrastructure projects in particular and regional economic growth in general. However, political and strategic motivations behind economic and technological competition will not only dim the opportunities for economic growth, but also fuel distrusts and suspicions among states in the Indo-Pacific.

The Indo-Pacific can become a driver of peace and prosperity in the whole world providing the United States and China can work together. At the same time, the region can also become an epicentre of turbulence in world politics if these two major powers remain at odds. The early flashpoint in 2020 may have occurred in the Middle East (with the stand-off between the US and Iran) but expect the Indo-Pacific to regain prominence as a cause for concern as the year progresses. Whichever direction the region takes, without a doubt the effects will be felt across the globe.

Featured Image Credit: “White and Black Desk Globe” by Andrew Neel. CC0 public domain via Pexels .

The post Four reasons why the Indo-Pacific matters in 2020 appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers