Orrin Grey's Blog: Shovel Murders & Monologues, page 15

October 2, 2021

“[Friday] Night at the movies, who cares what picture we see?”

For seven years now, every October I have gone to a local event called #Nerdoween, hosted by my favorite local theatre, the Screenland Armour, and the fine folks from the Nightmare Junkhead podcast. The gimmick is always the same: one night, three horror movies, all on a pre-chosen theme, but you don’t get to know what you’re going to see until the movies play.

In past years, the themes have included demons, sequels, anthologies, “sleazy sci-fi,” killer nouns, and Satan. This year, to celebrate the fact that movie theatres are kinda, sorta able to be open again a little bit, the theme was movies that take place, well, at the movies.

And I’m gonna warn you, one of the three movies we saw is a film best experienced as cold as humanly possible, and just knowing that it’s included in this list constitutes a spoiler of sorts for it, so I’m not going to say the title. If you follow me on Twitter or Letterboxd you can figure it out, but there’s only so much I can do to protect you from a movie from 1987.

I am a skeleton of few traditions, and #Nerdoween is one of the things that brings me the most joy each year. Every one of those seven years, my friend and adopted brother Jay has accompanied me. Unlike me, he is almost always exposed to entirely new things – across 21 movies, we determined that he had ever seen three of them before. And even I get introduced to at least one new film more often than not.

In fact, every year save two (this year and “killer nouns”), I’ve seen at least one new-to-me film, and sometimes (indeed, on three occasions) two. This year, the poor hosts set themselves a nearly impossible task if they wanted to show a movie I hadn’t seen, given the theme they picked, as I think I’ve seen most of those. At the same time, they came surprisingly close, as I had only seen one of the films for the first time earlier this year.

We kicked off the night with Popcorn (1991), perhaps the most obvious choice given the theme but also a perfect way to start things off. It was a blast to see in a theatre, as a movie that has always felt more like a Halloween party in a movie theatre than an actual movie.

That was followed up with Porno (2019), a movie I had previously seen when it made its debut at Panic Fest. I wasn’t a fan then, and I’m still not, but it was a good crowd movie. (It may surprise you to learn that it is remarkably difficult to perform a Google image search for stills from the movie Porno and actually turn up pictures from that movie.)

The last film of the night is often the weirdest and/or the heaviest – as is only right and proper – and this year it was both. I’m gonna refrain from saying its name here because, again, I think that to even include it on this list is to lose something of its magic, but for those who want to know, feel free to drop me a line, or you can check Letterboxd or my Twitter, where I spilled the beans.

Perhaps more so than any of the others, it was a real pleasure to see this in a theatre, especially given that literally no one else there had ever seen it besides me and one other person. Also, the sound mix was amazing.

So props to the Nightmare Junkhead crew for always putting on a great show, and I’m already looking forward to next year, when hopefully COVID will actually be a thing of the past and the only anxiety will be what’s up on the screen.

October 1, 2021

“We live in Hell.” – Two Books by Jonathan Raab for Halloween

“What’s hidden just beyond the veil? A bloody good time, of course.”

I’ve talked, often and at length, about how what I want to write, when I sit down to write, is “fun horror.” And because of that, I’m often asked in interviews or casual conversation just what I mean by that. The ethos behind it, sure, but also for examples, so I’m always pleased when I find some.

Jonathan Raab is not only one of the best living practitioners we have of the form, he’s also a testament to the fact that “fun horror” can also be smart horror, political horror, character-driven horror, psychological horror, cosmic horror, thinking person’s horror, you name it.

Raab refers to himself as a “hack horror writer,” and that affection for B-grade horror shines through in his work, but he’s never just making lazy pastiches of the slasher flicks that decorated our screens when we grew up. He’s taking the subtext that was often there – or that we saw there, even when it wasn’t – and making it text. Repurposing camp into paranoid, conspiracy-laden, doom-synth chronicles of the secret world behind the world, the scratching at the back of your brain, on the other side of the tube, on the outside of your window as you fall asleep.

As with so many writers I first got to know via social media, I can’t remember how Jonathan and I first met. We were already on friendly terms by the time he solicited a story from me for Terror in 16-Bits, drawn together because we shared a similar set of references, a similar cache of filmic, video game, and tabletop inspirations, a similar set of aesthetic and thematic fixations – yet also different enough to keep things from overlapping too much.

Aside from conventions, I’ve only ever met Jonathan in person once. I was spending some time in Boulder, Colorado – my significant other attending a flute workshop, myself tagging along to explore the environs and write in the hotel room – and I drove down to his house, past a prison, into a setting from a Jonathan Raab story, even though, at that time, I’m not positive I had yet ever read one.

We walked down the street and had a big breakfast at a crowded greasy spoon, then back to his place where we talked all manner of subjects high and low. By then we were already friends – I can’t remember yet if I was a fan.

I wrote a blurb for one of his books, The Lesser Swamp Gods of Little Dixie, but it was his novel Camp Ghoul Mountain Part VI that fully sold me. That converted me. As I read those pages – part fictionalized novelization of a late-era slasher movie that never was (or was it?), part conspiracy-laden meta-fictional journal, part cosmic horror – that I realized that Raab had risen to the ranks of one of my favorite working authors, the kind where I would eagerly seek out each new thing he did.

And given that short story collections are about my favorite type of book, well, I was damned excited about the release of The Secret Goatman Spookshow, Raab’s first such collection. I preordered the book, but I forced myself to wait to read it until we were nearing the Halloween season – which wasn’t as hard as it might otherwise have been, because I was buried in freelance work when it arrived.

Along with it, I had secreted away another little treasure. A zine-length special he had put out for the season called The Crypt of Blood. I’m bad at guessing word counts, but it was maybe a novella. An ideal length, spooky and short, but not too short. Enough so that there was some meat on the bones…

As summer gave way to fall, as September dwindled down to October, the month of rubber bats and autumn moons, of grinning pumpkins and cotton candy cobwebs, I read them both, one after the other. The Secret Goatman Spookshow would have made a convert of me, had I not been one already. The stories inside travel around, from those told prosaically to those presented in a more experimental fashion – there is a story in the form of the rules for a tabletop roleplaying game, episodes of a cable access show, an oral history of a video game – interspersed with fragments that often directly address the reader.

Yet all of them bear the unmistakable stamp of authorial voice. Whether he’s channeling the buckets of so-fake-it’s-real gore of a SOV slasher or the high strange horror of The X-Files, whether he’s simulating the techniques of found footage so effortlessly that it becomes unnoticeable, or peppering in references to Ghostbusters 2, every story is fun until the exact moment that it isn’t – pulling the rug from under your feet to show you the maggots that have always been squirming beneath.

The same is true of The Crypt of Blood just… focused. For an idea of what you’ll get with Crypt of Blood, imagine if the WNUF Halloween Special were a Hammer vampire film. Then imagine that they were entirely committed to the bit – so much so that the actual narrative was the stuff that took place off screen. Instead of faux commercials full of local color, you have bizarro interstitials that devolve into Ligottian weirdness – interstitials where the real story is being told, because in a Jonathan Raab story, the real story is always the one behind the curtain.

In other words, the perfect read for a dark and stormy Halloween night. (If a dark and stormy Halloween night is not available, please contact your local cable affiliate.)

September 28, 2021

Crestwood House Movie Monsters: Revenge of the Creature

Here we are with the third (of seven) in my weekly explorations of the purple cover Crestwood House Movie Monsters books that I found at an antique store. As I mentioned in my last post, this time around I’m tackling Revenge of the Creature, a 1987 title in the series adapting the (lackluster) 1955 sequel to Creature from the Black Lagoon.

Like The Mole People before it, Revenge is a film that has gotten the Mystery Science Theater 3000 treatment, meaning that I’m more than usually familiar with the script. Which, once again, enables me to let you know that the authors of this book, somewhat inexplicably, took some liberties with the events of the story.

While the end of the book isn’t identical to the end of the picture, it’s much closer this time around than in The Mole People. Instead, the differences crop up in other, less explicable places. For example, when the Gill Man arrives at Ocean Harbor in the movie, he comes by boat (Porpoise III, to be precise) whereas in the book he arrives in a seaplane “specially fitted to carry a large water tank.”

Ocean Harbor is called Ocean Harbor Seaworld in the book, as well. These are just a few of the differences, though most of the others are not so striking. The love triangle between John Agar (again playing a pompous scientist), Lori Nelson, and John Bromfield is downplayed here. The line Agar tosses out about Bromfield being a “grade-A wolf” is still here, but the follow-up that he’s not going to let “Captain America cut into my cake” is missing, along with much of the rest of the film’s sexism. Instead, Agar’s character and Bromfield’s shake hands and Nelson sees that they’re “good friends.”

The book also gets inside the Gill Man’s head a little bit. “Within the Gill Man’s slow brain, a plan was forming,” the authors inform us, after the Gill Man has absconded with Lori Nelson’s character. “This woman was his. He would take her with him to the Black Lagoon.”

Okay, so maybe not all of the sexism is gone.

(Thank god that still over there got a full-page spread, by the way, so we can all bask in its fine quality.)

Like all the books in this series, this one prefaces its retelling of the film with a brief prologue contextualizing the picture. “The earliest sailors believed that monsters lived under the sea,” this one starts. “Even when scientists proved that the stories were false, many people still half-believed them.”

Ah, those good ol’ days when even most people listened to scientists when they said stuff.

The prologue goes on to briefly explain what a sequel is, and suggest that this film was intended to make the audience “feel sorry for the Gill Man,” as if the first movie didn’t already do that more than adequately. “Will you feel sorry for the creature?” the authors ask. “Maybe… as long as he stays hidden in the Black Lagoon!”

September 26, 2021

A Tale of Two Teeth

So, here’s a story: Back when I was putting together my very first collection, it was originally going to include a story called “The Tooth.” Around the same time, however, Cullen Bunn was putting out a comic called The Tooth. To make matters worse, his comic was about a monster hero in the ’70s Marvel style that grew from a dragon’s tooth, while my story was about a ghost/monster that grew from a dead wizard’s tooth. What’s more, the publisher of my first collection happened to also be publishing some of Cullen’s stuff.

In other words, Cullen Bunn and I were engaged in a Swamp Thing/Man-Thing scenario, while we were both writing for the same publisher. “The Tooth” got retitled and, ultimately, pulled from my first collection, to eventually find its way into print (under its new and, frankly, better title, “Remains”) first in Strange Aeons and then in my second collection, Painted Monsters & Other Strange Beasts.

Cullen Bunn and I aren’t friends, per se, but we’ve remained on friendly terms over the years. He lives in Missouri, I live in Kansas right by the Missouri line, which means that we find ourselves at the same conventions and whatnot a lot of the time. In the years since my first collection came out, his career as a comic book writer has skyrocketed, and he has written, well, just all sorts of things, including lots of stuff for Marvel and DC, not to mention the really great Harrow County and The Sixth Gun.

What reminded me of all this was that last night, I finally got around to watching a movie that came out last year called The Empty Man. It’s adapted from one of Cullen’s comics. The movie seems to be divisive, but most of the weird fic folks I know who have seen it like it, and I totally get why. It’s a big swing at cosmic horror, fronted by a cold open that’s basically an M. R. James ghost story with a Zdzislaw Beksinski creature, and told in the form of a detective flick. Think True Detective only, honestly, this does it better.

It’s long as hell, which I actually dug, because I hate when movies are long except when they’re also long and boring. No, wait, what I mean is, I’m a sucker for overlong procedural stuff. People looking at photographs, digging through papers, going to places and putting pieces together. I can watch that all goddamn day, if it’s done even remotely well, and especially if there’s a supernatural component at the heart of it all.

Add to this that the film is set (though mostly not shot) in and around St. Louis, and I was completely onboard for the whole ride. If you haven’t seen it and you dig cosmic horror, weird fiction, and detective narratives, give it a shot. If you have, or if you’re not into it, at least it prompted me to tell an odd little anecdote about one of my stories…

September 22, 2021

Crestwood House Movie Monsters: The Mole People

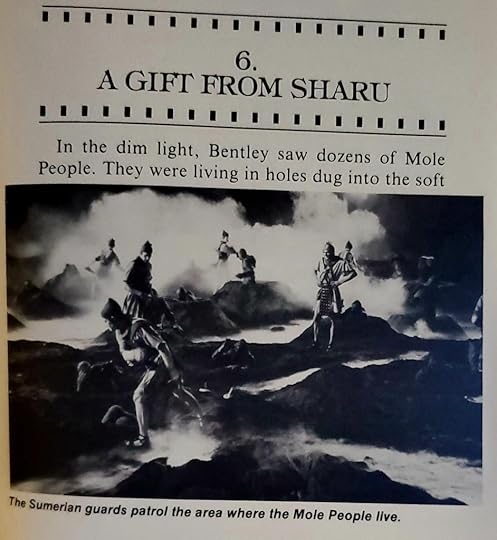

I wrote last time about my relationship with the Crestwood House monster books, how I found seven of them at an antique mall, and my plans to post about each one, one a week, until Halloween. So if you need a refresher, there you go.

Thanks to its being featured on an episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000, I am probably more familiar with the script for The Mole People than any other movie in either of the Crestwood sets, with the possible exception of two other MST alums, Revenge of the Creature (which I’ll be covering next time) and The Deadly Mantis, from the orange series. Which means I can tell you, unequivocally, that they changed some stuff here.

Like, the beats are all there, but the dialogue is all different. And not just that they excised some of it to keep the length of the book intact, what is there is almost always slightly off in wording – if usually similar in meaning – to what the actors actually say. But the dialogue is the least of it, in some ways. Perhaps the most startling change comes at the end…

The movie ends with the slave girl Adad – played by Cynthia Patrick, who has been gifted to John Agar’s pompous archaeologist Roger Bentley and becomes his love interest in typically ’50s creepy fashion – perishing in an aftershock just after Agar and company reach the surface. The earthquake is here, but Agar and Leave it to Beaver‘s Hugh Beaumont dig her back out and resuscitate her in a fairly anticlimactic sequence.

“Bently uncovered her face,” the authors write. “She was barely breathing. He started giving her first aid. At last, her eyes opened. In a little while she was strong enough to start the climb downward.”

Indeed, where the film ended with Adad perishing, then cutting to a sequence of the subterranean temple being destroyed by the quake, the book adds several paragraphs as Agar, Beaumont, and Patrick make their way down the mountain, and Agar laments that he has no proof of his discovery, except for Adad who, after all, looks just like any other (white) person.

He vows to dig the lost civilization back up, but Adad begs him not to, asking him to, “Let the mountain keep its secrets.”

Ultimately, he agrees. “After all,” the final lines of the book speculate, “there were plenty of other places he could dig. Besides, who would believe his story?”

Normally, in a novelization, we would chalk such a disparity up to the writers working from a shooting script, some previous version that got changed before the film was released. But given that The Mole People came out in 1956 and this book was copyrighted in 1985, that seems an unlikely explanation. Perhaps the authors were pressured (or simply chose) to give the tale a more traditional “happy” ending. I suppose only time will tell if the other volumes in this series share similar variations from their source material.

The ending isn’t the only deviation in The Mole People, even while it is the most major one. Agar’s character is less insufferable here than he is in the film, and, in a haphazard gesture toward at least a kind of diversity, the eponymous mole people are, occasionally, referred to as “Mole Men and Mole Women.” Oh, and the mole people talk in the book, which also doesn’t happen in the movie.

When Agar and Beaumont save some of the mole people from their albino Sumerian oppressors, one of them stops before leaving to tell Agar, “We re-mem-ber,” making their attack at the picture’s climax more an intentional combining of efforts, rather than the conveniently-timed but largely unrelated uprising that it seems on film.

September 15, 2021

Crestwood House Movie Monsters: Werewolf of London

I have written before, extensively, about my relationship with the Crestwood House monster books, most recently in the first issue of Weird Horror from Undertow Publications. For those who weren’t like me, the Crestwood House books were a series of retellings of the classic horror films of yesteryear, illustrated with evocative black-and-white film stills from those same flicks, at least some of them provided by none other than Forrest J. Ackerman.

The school library at just about every elementary school I ever attended had at least a few of them, usually the whole series. The first and best-known set, which kicked off in the late ’70s, had orange-and-black covers and titles hitting upon some of the biggest names in the Universal monster canon, including Frankenstein, Dracula, and The Creature from the Black Lagoon – not to mention more weirdo titles like The Deadly Mantis and It Came from Outer Space.

Each of those orange books provided an abridged novelization of the film, alongside trivia and context for the films that surrounded it. The Frankenstein book, for instance, summarized the James Whale film, but also talked about Mary Shelley’s novel, Thomas Edison’s Frankenstein, and other films and adaptations before and since.

The lesser-known purple series came out later, kicking off in the ’80s (the ones I have are copyrighted 1985 and 1987) and including more B-sides than its predecessor. Hence, we get titles like Werewolf of London, Tarantula, and House of Fear.

The dimensions of the books were also smaller. While the orange titles were the size of a standard “board book,” the purple series were closer in scale to a mid-grade chapter book. And where the orange books had included a breezy summary of the main film, alongside details about others, the purple series included a more scene-by-scene novelization of the film in question, even if the result was still quite brisk.

While I was obsessed with those books, I never owned any of them – I’m pretty sure they were sold only to libraries, as I’ve never seen a copy without a library stamp inside. Today, they sell for big bucks online, when you can find them at all. Recently, I came across seven of the purple cover titles in a book-filled booth at an antique mall, and brought them all home with me. It’s not quite the full series – I’ve never been able to find a definitive list, but I know I’m missing several titles. Now, as we head toward Halloween, I’ll be reading one a week and posting about it here.

Most of the books in the orange cover series were credited to writer Ian Thorne, actually science fiction author Julian May. All of the purple ones – or, at least, the ones I have – are credited to Carl R. Green and William R. Sanford, authors, according to the website of Enslow Publishing, of “more than one hundred books for young people.”

Each book includes a prologue, usually about a page long, that gives some minor context for the story you’re about to read, and from there on it’s just raw adaptation of the screenplay, accompanied, once again, by black-and-white stills.

I decided to start with Werewolf of London for a variety of reasons. The 1935 film is an oddity, given that it predates The Wolf Man by more than half-a-decade, yet never managed to kick off a franchise the way that film did, even though it was the first mainstream Hollywood film to feature a werewolf. What’s more, it actually features two werewolves, and not just one begetting the other, as in that later picture. Here, there’s an actual werewolf-on-werewolf fight!

Werewolf of London is also interesting in its relationship to the Crestwood House canon. While it didn’t get a book in the orange series, it also kind of did. Not only does the orange Wolf Man book summarize this flick alongside the Lon Chaney Jr. one, it’s the werewolf from Werewolf of London – with his Eddie Munster widow’s peak – who decorates that cover.

It’s been long enough since I watched the film that I can’t tell you for sure which liberties Green and Sanford took with the script, but the writing is, for the most part, of the “see Jane run” style you might expect, with short, unambiguous sentences. “Lisa and Miss Ettie ran down the stairs,” one climactic scene tells us. “The wolfman was faster.”

Which is not to say that such direct language can’t be occasionally effective. “Glendon knew he was now a werewolf,” an earlier scene says, conveying his transformation. “Deep, evil powers ruled him.”

August 28, 2021

Sweets to the sweet…

“A story like that, a pain like that, it lasts forever.”

It would be more dramatic to say that today was the first time I set foot in a movie theatre since February of last year, when I went to see Underwater, blissfully ignorant that it would be my last movie before the pandemic. But that’s not wholly accurate. I went to a very socially-distanced Nerdoween last October, and I’ve been to a couple of Analog Sundays over the past few months, since I got vaccinated and they started up again.

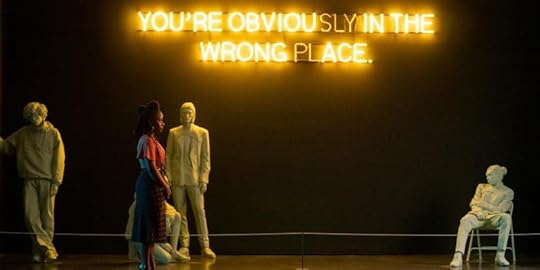

It is true, though, that Candyman is not merely the first new-release movie of 2021 that I’ve seen, it’s the only first-run movie that I’ve caught in a theatre since that fateful showing of Underwater. In a way that even Analog Sunday hasn’t quite, it felt like a homecoming.

Since whenever the hell it first got announced way back before the plague times, I have been excited to catch this new Candyman. I am not as familiar as I maybe should be with director Nia DaCosta, but Jordan Peele’s other horror efforts have been some of my favorite films of the past decade, and I was extremely excited to see an #ownvoices take on this material.

More to the point, though, Candyman is one of my favorite films. It is, for my money, the best screen adaptation to date of anything by Clive Barker, himself one of my favorite creators. This is, in no small part, because it actually improves upon the source material, by moving the action from the projects of London to Chicago’s Cabrini Green and changing the race of the eponymous urban legend, thereby also changing the socio-political heft of the story for the better.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given Peele’s name in the credits, this new Candyman takes that added heft and runs with it. What is more surprising, for me, is how well the movie seems to get what the original Candyman was all about. Better than many fans of the movie seem to. Certainly better than any of the other sequels ever did.

There are going to be mild spoilers from here on in, so read at your own risk.

Tony Todd is in this movie. I don’t feel like that’s a surprise, at this point. He’s not all over the trailer or anything, but they also haven’t exactly kept it under their hats. But he’s not in it much. Instead, the legend of Candyman has… expanded. Candyman is no longer just Daniel Robitaille – but then, he never was.

What this movie nails that so many don’t get is that Candyman isn’t a ghost. He’s not even the more tangible revenant that slashers like Jason and Freddy represent. He is the tragedy itself, not the person the tragedy happened to. “It is a blessed condition, believe me,” he says to Helen Lyle. “To be whispered about at street corners. To live in other people’s dreams, but not to have to be.”

That quote, which is also lifted more-or-less whole cloth from the original Clive Barker story “The Forbidden,” as many of the original movie’s best lines are, always resonated hard with me. It’s why I used it as the epigraph for my story “Ripperology.”

Candyman is not the person, Candyman is the myth. It’s true for him in a way that it isn’t for any of the other slashers, even while there’s an element of the urban legend about all of them. It is that element of the original’s power that this movie gets, and runs with, and exploits for its own purposes to very interesting and satisfying – at least for me – ends.

This new Candyman is not the picture that the original was – it can’t be and, mostly to its credit, it doesn’t try. It’s messier and more ambitious. It’s the rare movie that I actually think would have benefitted from being longer. Giving its characters, its mysteries, its recursions and inversions more time to breathe. Writing at the AV Club, Anya Stanley argued that the film would have been better served as a TV series and, for once, I don’t necessarily disagree.

Even at a brisk 91 minutes, however, and amid not-infrequent missteps, DaCosta and company have crafted a haunting, complex, sometimes funny, often gruesome puzzle box movie that simultaneously serves as one of the better things to grow organically out of Clive Barker’s extensive and often very organic oeuvre, and also very much its own creature.

In a world of largely unnecessary remake/sequels (requels?), the others could stand to take notes.

August 20, 2021

Badreads

I’ve been using Goodreads for… many years now. I’d be too lazy to figure out how many, but fortunately my profile over there just handily tells me that it’s a little over 12 – I apparently started in March of 2009.

March of 2009 is like another world. At that time, I was still three years out from the publication of my first collection, and I had only sold the tiniest handful of short stories. In fact, 2009 would have been the year that I published my first chapbook novella, The Mysterious Flame, and the year that I attended my very first writing convention, ReaderCon.

In that time, again according to the site’s own stats because otherwise I would certainly have no way of knowing, I have read and reviewed more than 600 books. I won’t be doing that anymore. Reviewing, I mean, at least not on Goodreads.

I’ll probably still be reading books and occasionally writing reviews for places like Signal Horizon that don’t have the problems I’m here to talk about. But, let’s be honest, if you look back over my Goodreads activity for the last year or two, you won’t see anything all the much different from “nothing.” So I doubt anyone would even notice, if I didn’t make the announcement here.

If, like me, you are active at all in writing and book blogging circles, you have probably seen an article making the rounds from Time focused on the site’s problems with “review bombing” and extortion scams. And they’re part of what’s informing this decision, to be sure, but those topics are really only symptoms made possible by Goodreads’ larger problem.

It’s tempting to lay the blame at the feet of the site’s 2013 acquisition by Amazon, but I honestly don’t know when the problem started. What I do know – what I have heard time and time again, from authors both more and less “successful” than me, whatever that word even means – is that Goodreads has a disproportionate power to make or break a writer’s career.

For those dozen years that I’ve been reading and reviewing books on Goodreads, I’ve treated the site much as I treat Letterboxd now: a place where I leave a review and a star rating (even though I’m not terribly fond of using numerical rankings to describe experiences) that reflects my feelings about the book I just read.

This means that a book may get a rating of anywhere from one star to five, based on how much the thing spoke to me, personally. It also means that some things get judged by different criteria than others – I have to have some way of telling all the Mike Mignola comics apart without just giving them all five stars, after all.

The problem is that Goodreads has become a place where, if you give less than five stars to any book, you are basically putting a bullet in that author’s future sales, especially if they’re an indie author, or a marginalized one, or really anybody but, like, Stephen King or J. K. Rowling.

I don’t like that, but it’s the reality of the situation. Ratings on Goodreads and Amazon have huge impacts on the algorithms that get books in front of people and directly impact sales in significant and meaningful ways. A drop of even a few percentage points has real repercussions for an author’s ability to sell their next book, or the one after that.

I can’t change that. It doesn’t matter that I have my own reasons for a rating I might assign, my own system of determining how many stars I click. The algorithm doesn’t know and, more to the point, it doesn’t care. So, the only really ethical choice is to rate every single book five stars, or stop rating them at all. For the most part, I’ll probably be doing that second one.

I’m not shutting down my Goodreads account just yet, though I’ll admit that I’m on there rarely enough as it is. I’m not even going to swear that I’ll never review another book on the site. I may, and when I do just always hand out five stars each time. But I’ll no longer use it to track what I read, as I have until now. I’ll probably go back to doing that the old-fashioned way, in a paper journal – which I still do for movies, even though I also use Letterboxd until such time as I learn that it is equally ethically compromised.

Nor am I presuming to tell you what you should do with your Goodreads habits, except to say this: Think about them, and think hard. Before you leave your next two or three or even four-star review, do some reading about how this system affects authors, especially those who are the most vulnerable. If you have a favorite author with whom you talk or correspond, ask them for their take on the situation. And let all that inform your decision before you select those stars.

August 13, 2021

A Pin in My Head

Back in 1982, more than a full decade before DC would launch their own, more successful Vertigo line of comics for “mature audiences,” Marvel introduced its Epic Comics imprint. Operating without the Comics Code seal of approval, Epic was also a place where creator-owned projects could happen – and sometimes did, including such titles as Groo the Wanderer and Sam & Max.

By the end of the decade, Epic was also licensing literary (and other) properties, leading to titles as diverse as Wild Cards, Tekworld, the really phenomenal Fafhrd & the Gray Mouser comics by Howard Chaykin and Mike Mignola, even a partial adaptation of Neuromancer – not to mention stuff like Elfquest, translations of Akira, and some weirdo crossover titles from their regular line, including a revival of Tomb of Dracula and that Silver Surfer comic that Moebius did, to name a few.

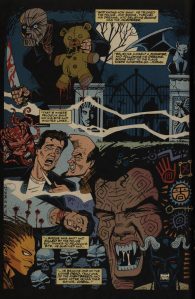

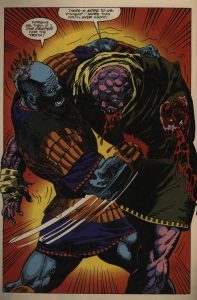

Among the strangest of these, for what we typically think of as Marvel Comics – though not, after all, so strange for the comics scene in the late ’80s and early ’90s – were a series of titles adapting, reimagining, repurposing, and expanding the works of Clive Barker, perhaps most notably Hellraiser. (The pictures accompanying this post are all borrowed from the Totally Epic blog, whose writer set themselves the perhaps-unenviable task of reading everything the imprint ever put out.)

The Hellraiser comic series kicked off in 1989 and ran for about twenty of these, like, digest-sized issues with cardstock covers and square binding. They’re all pretty nice, and they boast an impressive roster of talent, though most are more famous now than they were then. At least one of the Wachowski siblings is here, along with folks like Neil Gaiman, Scott Hampton, Mike Mignola, Bernie Wrightson, and Barker himself.

Besides the main Hellraiser series, there were spin-offs and also-rans, including a three-part adaptation of Barker’s novel Weaveworld and a Nightbreed series that ran for 25 issues or so and has since been collected into a nice hardcover from Boom, complete with a Mike Mignola cover.

There were also spin-off titles to the more popular Hellraiser, including one for Pinhead, which launched in 1993 and ran for six issues, all of them written or co-written by D. G. Chichester, a name that will be familiar to anyone who read much of the Hellraiser comic series. Also spinning off from that series was Harrowers: Raiders of the Abyss, which followed a handful of outcasts who had made their first appearance in the Hellraiser story that Barker had contributed, who were chosen by the goddess Morte Mamme to rescue souls from the Cenobites.

The Pinhead series sees the eponymous Cenobite hurled backward through his past incarnations throughout history, all of whom have different stupid shit stuck in their heads, including bones, arrowheads, and, at one point, tiny bronze swords. Also, because this was 1993, the first issue has a foil cover with art by Kelley Jones.

Harrowers feels maybe more like a regular comic book than most of the rest of these titles, in that it’s about a team of people with super powers who are uncomfortably united by a mission. It definitely feels like something that was intended to go on for more than 6 issues, as the storylines feel like they’re just warming up about the time they stop, and the Harrowers only save, like, three souls from Hell, and one of those is the wrong one. They also fight a headless statue possessed by the soul of Marc Antony in Times Square so, y’know, there’s that.

Probably more than any of the other Cliver Barker Epic titles, Harrowers feels like a warm up for what was to (briefly) come, the launch of a whole imprint, Razorline, dedicated entirely to characters and concepts made up by Barker. Separate from proper Marvel continuity – it’s officially Earth-45828, for those who keep track of such things; meaning who knows, maybe it’ll show up in the MCU once Disney inexplicably acquires whoever owns the rights to Barker’s various IPs – it was also distinct from anything else Barker had done.

While the Epic titles had all played in the Hellraiser sandbox, or adjacent to it in one of Barker’s other literary properties, Razorline was ostensibly going to be all new stories. Some promising talent was even attached, most notably to Ectokid, which started out penned by James Robinson before being handed off to Lana Wachowski – we were still several years pre-Matrix or even Bound at this point, remember.

Razorline amounted to four titles: the aforementioned Ectokid, the overtly superhero-y Hyperkind, the more artsy Saint Sinner, and the phenomenally-titled Hokum & Hex. (Barker may have been partial enough to the name Saint Sinner to use it for an unrelated TV movie in 2002, but Hokum & Hex was pretty clearly his best naming job.) Most of them only ran for nine issues. (Saint Sinner didn’t even make it quite that far.)

I’ve read the majority of these comics, though not most of the Razorline ones. The idea of this weirdo moment in time, when Clive Barker, of all fucking people, was mainstream enough that Marvel was publishing tie-ins of his shit, fascinates me, even while the comics themselves are all over the place. But I’ll be honest, I love them more being all over the place than I would if they were legit great comics (which they very occasionally are, especially some of the Hellraiser stories).

There’s a purity to these oddball comics that ran for a handful of issues and were, generally speaking, a wild combo of cash grab and someone’s genuine love of the material. It’s reminiscent of that magic you find in the gleam of just the right low-budget exploitation B-movie. One of the highs I’m always chasing. One more pin in my head…

August 9, 2021

“…it was a photograph from life.”

I’m a writer, in case you hadn’t already figured that out. But my work has been and continues to be heavily influenced by visual media. Movies, of course, but also comic books, graphic novels, video games, fine arts, and, perhaps above all those others, illustration of various forms.

Beyond broader influences, I’ve written stories directly inspired by the photographs of William Mortensen, the paintings of Goya, wax anatomical models, and penny-arcade dioramas, to name just a few. Not to mention all of the movies that have directly inspired specific stories.

It’s why my list of major influences includes easily as many illustrators as writers – and many who are both – even though I’m no hand at all when it comes to illustrating myself. There are many names in that pantheon, and none are more important to the formation of my imagination as it exists today than Mike Mignola. But today I’m here to talk about someone else.

I’m not actually sure where I saw my first Gary Gianni illustration. It’s possible that, like so many other things, I came to his work by way of Mignola, through one of the Monster Men stories that served as backups in Hellboy comics (and vice versa). Those Monster Men comics have since been collected, by the way, and are amazing.

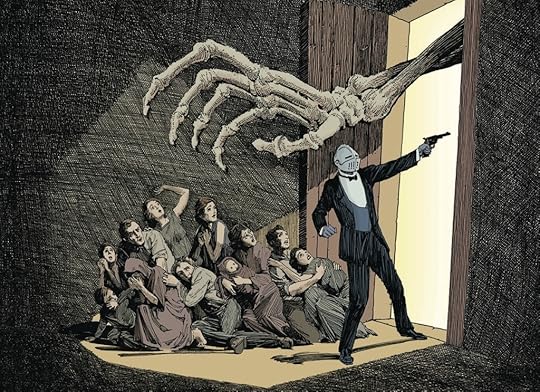

Or it may have been his illustrated version of some classic tale of weird fiction in one of the Dark Horse Book of… collections. What I do know is that, in short order, Gianni became the lens through which I tended to see classic weird tales of the golden age. There is something about his style that elevates it beyond mere pastiche of the old pulp illustrators. A wildness to his design sensibility, especially when it comes to drawing monsters, that puts him alongside folks like Virgil Finlay, Sidney Sime, and Lee Brown Coye, rather than working in their shadow.

(The more proper modern successors of Coye might be folks like Richard Corben and, more recently, Nick Gucker, who did several of my own book covers, but you get the idea.)

Gianni’s illustrations for Solomon Kane and some of the Conan books, not to mention the aforementioned stuff from the Dark Horse Book of… volumes, helped to cement him, in my mind, as the go-to guy for illustrating those kinds of tales. At least, the way I imagined seeing them illustrated.

A few years back, I got to meet him at the Spectrum Fantastic Art Live event here in Kansas City, and he seemed to be a genuinely nice guy, which was also pleasant. I had him sign some stuff, picked up a sketchbook, and was generally just happy to get to tell someone, even using highly inadequate words, what their work meant to me.

I hadn’t thought much about Gianni in some time – maybe not since Hellboy: Into the Silent Sea with his amazingly detailed art came out – when I saw Mike Mignola post a link to a new edition of Lovecraft’s “Call of Cthulhu,” with 100 new illustrations by Gianni. As I said on social media: Does anyone really need another edition of “Call of Cthulhu?” Maybe not. But does everyone need 100 new illustrations by Gary Gianni, drawing the kind of golden age pulp stuff that his style seems made for?

Absolutely, yes.