David O. Stewart's Blog, page 2

July 20, 2019

Newsletter, Spring 2019!

The top news: (i) Rating the presidents with C-SPAN, and (ii) my month at Mount Vernon with the people who know George Washington best.

Also:

Talking about the Constitution and presidential impeachment.

Hidden figures of history and the books you must read before you die

The Bookshelf — great books, both new and new-to-me.

Rating the Presidents on C-SPAN

On Saturday afternoon, April 27, I joined ace historian Ken Ackerman at the Newseum in Washington, DC, for a favorite indoor sport: rating our presidents. Actually, our mission was to rate the ratings produced by a recent C-SPAN survey of 100 historians (not moi). The top three are easy (Lincoln, Washington, FDR, in any order you like), as are the bottom two (Andrew Johnson & James Buchanan). In between is where the disagreements come! The conversation included C-SPAN founder and modern marvel Brian Lamb, plus his successor, Susan Swain. (Ken’s on the left above, Brian on the right, and, well, you can pick out Susan).

We explored the bottom of the rankings, which was unavoidable since I wrote a book about Andrew Johnson’s impeachment and Ken did one on James Garfield. Johnson, after all, ranks next-to-last on every recent survey (thank heavens for Buchanan!). When asked how we thought our current president might fare in future rankings, I suggested that Johnson might jump up a little in the next round. . . .

You can watch the show at the C-SPAN website or buy the C-SPAN book on ranking the presidents, which has the punchy title, The Presidents.

Happy 287th, George Washington!

My month-long fellowship at Mount Vernon landed in the shortest month, February, so included the celebration of GW’s 287th birthday. Joined by my wife Nancy, the partying started early, including the obligatory cringing at the poor man’s dentures (below). How could he do anything with that in his mouth? Thank you, modern dentistry.

The fellowship was a chance to work on my book about Washington’s under-appreciated political talents, America’s Master Politician (target release date: early 2021). He wasn’t just a tall guy who looked good on a horse.

It also allowed me to connect with the sprawling community of students of GW, assisted by the Mount Vernon elite — CEO , Library Director , and research whiz Mary Thompson (a fellow alumnus of Staten Island in the 1960s). Watch for Mary’s book on GW and slavery, “The Only Unavoidable Subject of Regret.”

EVEN MORE IMPORTANT was the good cheer and learning of my fellow fellows (?): Brian Steele (working on the memories and reputation of GW in the years immediately after his death) and George Goodwin.(GW and Ben Franklin conduct a propaganda war against Britain during the Revolution).

You may have seen the news report that when our president visited Mount Vernon in April 2018, he criticized Washington for not naming the estate after himself. “’If he was smart, he would’ve put his name on it,’ Trump said, according to three sources briefed on the exchange. ‘You’ve got to put your name on stuff or no one remembers you.'”

CEO Bradburn, leading the tour, replied that GW gave his name to the nation’s capital.

Talking about the Constitution, Impeachment, and . . . Lincoln

I was glad to be featured on a podcast on the writing of the Constitution, which was produced by New Hampshire Public Radio as part of its Civics 101 series. This podcast stuff, it’s catching on, right? So twenty-first century.

No let-up in the impeachment opinioneering: I still doubtl that — as Speaker. Pelosi put it — he’s worth it, and said so in The Hill. But people are wondering about impeachment, so in the Baltimore Sun I offered a parallel between our current president and a couple of the impeachment all-stars (Richard Nixon, Andrew Johnson). The common thread: angry older men.

Also, I had great fun reviewing Louis Bayard’s terrific new historical novel, Courting Mr. Lincoln, over at the Washington Independent Review of Books. Not your father’s book review!

Speaking Gigs

I’d love to see you at one of my upcoming events:

May 8, 2019, 12:00 p.m., Brandeis Book Club, Woodmont Country Club, Bethesda: Madison’s Gift: Five Partnerships that Built America ,

May 11, 2019, 10:00 a.m., Washington Writer’s Conference: Bethesda North Marriott Hotel and Conference Center: Moderating a panel of history writers on “Hidden Histories.”

May 18, 2019, Gaithersburg Book Festival, 1:15 p.m., in conversation with James Mustich, author of 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die.

September 20, 2019, 6:00 p.m., Charleston Library Society, Charleston, SC: The Summer of 1787.

The Bookshelf: Good books I’ve finally managed to read —

The Friend, by Sigrid Nunez — Winner of the National Book Award for fiction, this book has some powerful elements (suicide, violence against women), and an endlessly charming Great Dane, though it delivered more palaver than I needed about writers and writing, BUT, the writer is another grew-up-on-Staten-Island person, so how can I not list it?

Freedom’s Detective: The Secret Service, the Ku Klux Klan and the Man Who Masterminded America’s First War on Terror, by Charles Lane — A fascinating story, well-told, about the sketchy character, Hiram Whitley, who led the government’s near-suppression of the KKK in the early 1870s. The only negative for me was the book’s subtitle, Exhibit A for the case that nonfiction subtitles are metastasizing to dangerous dimensions.

Invisible: The Forgotten Story of the Black Woman Lawyer Who Took Down America’s Most Powerful Mobster, by Stephen L. Carter — A remarkable tale about Steve Carter’s grandmother, who designed the prosecution of Lucky Luciano (and also was befriended by Governor Calvin Coolidge while she attended Smith College). A book that taught me about the world of high-achieving African-Americans of the last century. As for its subtitle, consider it Exhibit B to my last complaint.

Agents of Innocence, by David Ignatius — Okay, this one’s decades old, but I just read it and it’s really really good. Terrorism and betrayal in the Middle East hasn’t exactly gone out of style. This is the fourth Ignatius novel I’ve read. All winners so far.

The post Newsletter, Spring 2019! appeared first on David O. Stewart.

November 13, 2018

The Framers knew more words than we do

Maybe I should say that eighteenth-century Americans knew and used very different words. Because my current book project plunges me into a seemingly endless supply of George Washington’s correspondence and other records of the time, I bump into lots of surprising words.

Even when the words are new to me, sometimes their meanings are clear enough. Take “disgustful,” for example. I didn’t need dictionary.com to tell me that it means “causing disgust; nauseous; offensive,” but I’m glad that the word survives even in that non-authoritative resource. I like the word: By saying we are FULL of disgust, it seems more powerful than merely “disgusting,”

The modern reader can readily identify meanings for other unfamiliar terms, a few of which may have been concocted by the long-ago writer who enjoyed the flexible linguistic rules of the day:

“stealingly” — secretly: though the word is not on dictionary.com; the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) calls it “rare”;

“plentier” — even more of something, and a good deal pithier than today’s “more plentiful”; alas, the word appears in neither dictionary; I suspect the writer made it up on the fly;

“consolatory” — providing consolation, and recorded in both dictionaries;

“inertitude” — from context, the writer meant it to signify the condition of being inert; I LOVE this word for its mock-learned feel, like something President George W. Bush would say (remember “misunderestimated“?), or maybe Will Ferrell. The word, unsurprisingly, appears in neither the OED nor dictionary.com.

Some words meant something in the 1700s that they no longer mean. Thus, Virginians back then described floods of rivers and creeks as “freshes,” a usage feels very wrong to me. Something “fresh” should be a good thing, but floods do not fall into that category. Then again, the eighteenth century used “wonderful” to mean something that caused a person to puzzle over something, as in, “it’s wonderful that birds can fly,” or “it’s wonderful that lowering taxes is supposed to reduce budget deficits.” They did not use “wonderful” to mean good, or exciting or happy, the way we do.

The most embarrassing word for me was “irruption,” which I first encountered as referring to invading Canada. (Americans often wanted to invade Canada — it was the default way to strike back at Great Britain, but it generally proved more difficult than expected, especially in the winter.)

I assumed that the writer had simply misspelled “eruption,” an odd word choice for an invasion, but not a crazy one. But then other writers used “irruption” to describe the Canadian invasion, so I finally looked it up. Yup, even dictionary.com has it: “a breaking or bursting in; a violent incursion or invasion.” Live and learn.

Then come the words that, well, they’re still in dictionaries but they might as well not be for all I’ve ever run into them. Words like:

“Fugacious” — Fleeting, transitory.

“Dibble” — “a small, handheld, pointed implement for making holes in soil for planting seedlings, bulbs, etc.” Well, I’m no gardener.

“Flagitious” — “shamefully wicked.” We could use this one today, as in a “flagitious tweet.”

Since I spend so much time with eighteenth-century words, I can struggle with current slang, especially the shorthand acronyms like “GOAT” and “FOMO.” It’s a tradeoff, but not one that troubles me much.

July 22, 2018

Adventures in Bookland: Bookstores Spring to Life in DC Area!

Today, before the heavens poured more rain on us, I conducted a quick tour of four new bookstores in the Washington area. While Barnes & Noble’s retailing strategy in the area involves closing its stores in an agonizingly slow decline to full corporate disappearance, other book retailers are jumping into the market — a heartening development for those of us who scribble for a living.

All of the stores I visited had good foot traffic and rang up sales while I was there.

I started at the Politics & Prose branch at Union Market, 1270 5th St., NW, a formerly dodgy/industrial part of town. As a longtime devotee of the flagship P&P store on Connecticut Avenue, which has itself expanded in the last few years, I found the vibe at the branch pretty familiar. The store’s footprint is not huge, but its inventory was rather good, largely by making use of very TALL bookshelf units (NINE shelves high), also pretty true at the flagship store. Stepstools were in evidence.

At Politics & Prose, Union Market: Note the tall shelves and red stool crouching next to the check-out desk.

They showed me an overflow area where they stage events and can accommodate a fairly large group. Non-book merchandise is at a minimum, though they’re planning a cafe in other auxiliary space alongside the store.

MAJOR PLUS: of the stores I visited, P&P was the only one with a book of mine on the shelf (The Summer of 1787). Extremely charming. I commend the store highly.

Solid State Books at 600 H St., N.E. offered further evidence of the area’s gentrification. I spent a summer in an apartment not far away during the Nixon Administration (egad!). The store sits on a street that then was largely burnt out from the MLK assassination rioting of 1968.

Lots of space to roam at Solid State Books, and room to expand the inventory!

Of the sites I visited, I liked Solid State’s space the best. They have a large footprint and have kept it quite open, which creates an accessible feel. I hope that in the coming months and years, they choose to insert more shelving so they can stock a wider inventory. Of the independents that I visited, only Solid State seemed to have the space to evolve into more than a neighborhood fixture (though parking was not easy on a Sunday morning). For now, the openness of the site allows events after they push back some bookcases.

East City Bookshop at 645 Pennsylvania Ave., S.E., is final confirmation that the eastern half of the city is a retail boom are. East City has been around a couple of years, and has a well-established events calendar, which they accommodate by pushing around shelving in the lower level.

East City Bookshop — close quarters, but friendly

East City touts itself as Washington’s only woman-owned independent bookstore, though I can’t say I found that quality seemed to make much difference to the inventory and feel of the place. I should note that it was the only location where a store employee (or owner?) approached me first to offer assistance. After we spoke for a few minutes, she greeted other customers the same way. An excellent practice.

Then it was on to the 800-pound gorilla: the new Amazon retail store in Bethesda. I have the mixed feelings about Amazon that most authors share. They have sold a boatload of my books, so it’s hard to be totally hostile. Bluntly, I need them too much for that.

But they know how much I need them, and mean to take advantage of it. Their hijinks in pricing and brutal tactics toward publishers (admittedly, not the most sympathetic victims), have been well-documented. These days, I am flummoxed to explain why they keep replacing the click-through to my publishers’ NEW copies of my books in favor of links to used copies offered by third-party sellers. Indeed, Amazon occasionally makes it hard to find an actual new copy of the books on their site. The practice screws authors (no royalties on used books) and publishers (no revenue on used books), and frustrates those consumers who actually want a new copy. So, they screw the author and publisher (their supposed partners) and some of their customers. What, exactly, is Amazon’s upside? Because they can?

The retail store at 7117 Arlington Road, Bethesda, is a pretty large space and was hopping when I was there. Lots of shoppers shuffled through, and the cash registers hummed. The inventory is very thin — almost all hot titles, based on sales through the online site, and all volumes shelved facing out, rather than with spines showing. I found no staffers to chat with other than the clerks ringing up sales. The space has the charm of a vending machine, and features lots of electronic devices for sale. There’s no event space.

Amazon in Bethesda — devices plus plastic vibe.

If you’re an Amazon Prime member, you can get the online prices if you find a book you want. The store is better than the nothing we have had since losing the B&N store on Bethesda Row. It did nothing to erase my nostalgia for that store.

The rain kept me from the relatively new Politics & Prose site at the Wharf, And I don’t mean to slight existing indie stores, One More Page Books in at 2200 N Westmoreland St, Arlington, and Upshur Street Books (at, of course, 827 Upshur Street, NW, another gentrifying neighborhood). All are worthy, and welcome players in the regional book culture.

I made an unscheduled stop at Capitol Hill Books at 657 C St., NE, a second-hand store, that had all the charm that Amazon disdains, along with a couple of extra quirky features that I had to photograph for your enjoyment.

At Capitol Hill Books, no space goes unused and your time in the restroom is not wasted — rare marketing savvy!

A lively imaginary event calendar at Capitol Hill Books!

July 9, 2018

Impeachment and George Washington: When it rains, it pours

Is this George Washington? Really? (Painted by Walter Robertson, 1790s.

Back in April, I wrote two short pieces on history topics of interest to me — impeachment trials and George Washington. So, naturally enough, they both launched on the web this weekend, within 24 hours of each other. So I might as well promote them together, right? You can check out:

My take that historians need to back off from analyzing Washington’s “110 Rules of Civility,” which were initially composed by French Jesuits in the late sixteenth century. After copying them into his schoolbook as an apparent penmanship exercise, Washington NEVER mentioned them again. There’s no evidence that he ever thought of them again. On History News Network —

My explanation of what presidential impeachment trial have been, and are likely to be: that is, not really a trial, but more of political kabuki theater. They tried to put President Andrew Johnson to a real trial, and it didn’t work very well. They didn’t much try when it came to Bill Clinton, which is likely to be the pattern in the future. On Law 360 —

BONUS ROUND: check out the life portraits of George Washington that Mount Vernon has posted on its website, especially the last six or so, which were all painted in his final years. Is that the same guy in every picture?

Gotta get back to work. . . .

April 16, 2018

Does Going There Matter?

Multi-prize-winning author T.J. Stiles (Custer’s Trials, The First Tycoon) recently posed this question on social media. “Do historians have to visit the sites in their books?” he asked. “I say no, no more than you have to have been alive in the times you write about.” Stiles contended that what is important is “personal experience,” which allows the writer to understand the feelings triggered in different situations, adding:

“I think the least necessary experience is going to a place where past events transpired. It can be helpful, or not — landscapes change, and often are well-documented. But a sense of the interior experience . . . that’s the tricky part.”

T.J. Stiles: “Don’t need to go there”

For fiction writing, a similar view was offered by Lawrence Block in his excellent primer on novel-writing (cleverly titled Writing the Novel), who insists that “with a decent atlas and a library of travel guides, it’s not all that difficult to do an acceptable job of faking a location.” Pointing to Yugoslavian settings he imagined, Block wrote:

Lawrence Block: OK to fake it

“I’m quite sure my Balkan settings bore little relationship to reality. Then again, I’m equally certain the overwhelming majority of my readers weren’t aware of the discrepancy between my version of Yugoslavia and the real one.”

Yes. And No.

Having written both history and historical fiction, I am firmly of two minds on this question. In novels, I have definitely faked settings. For The Lincoln Deception, I had to write a several scenes in and around a mansion on the southern shore of Lake Erie. Google Images supplied some photos of that shoreline, and, well, I made up the mansion.

Would it have been better to go to the lake and check it out? Maybe, if I could have found a suitable mansion to describe, and if I lived close to it. But once I was sure that the shoreline had no special characteristics, my experience of lakes and tours through mansions seemed good enough.

I felt differently for The Wilson Deception , which was set in France — mostly in Paris after World War I, with a look at the experience of American soldiers in the trenches. I spent two weeks in those locations, just getting comfortable with how the buildings from that period felt, with the food, with the language — all of which have changed since 1919, but are much closer to that reality than anything I see in suburban Maryland.

I was especially keen to get a close look at the Hotel de Crillon on Place de la Concorde, which was home to the American delegation to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. Wouldn’t you know it? The hotel was closed for renovations for the year I worked on the novel, so I never did get inside.

Hotel de Crillon, Paris

What to do? In Paris, I went to view some other big old French buildings from the era and — with permission from Lawrence Block — faked it.

For historical works, though, I’m considerably more demanding, because readers should be. To write about the Constitutional Convention in 1787, I spent time at Independence Hall in Philadelphia. After all, the delegates spent four months in that room. I wanted to understand the organization of the tables and chairs, the acoustics, the light through the windows — even where the privy likely was.

When writing about James Madison, I spent a few days at his Montpelier estate, which helped most for his retirement years — especially being in the room where he spent the last two years of his life. The room opens onto the dining room, so he could take his meals at the door and converse with guests who were eating at the dining room table. You have to see it. . .

Room where James Madison spent his last two years, and died

And now that I’m working on a book about George Washington, I’ve visited all the important locations from his early life — starting with Mount Vernon, of course, but including his boyhood homes in Westmoreland County and in Fredericksburg, Barbados, Winchester, his lands on Bullskin Creek in “the west,” and multiple sites in Alexandria. For the rest of the book, I still need to get to Williamsburg, New York City, Philadelphia — my head hurts thinking about it.

To write history, there are only two choices for describing a setting: either go there and see it myself, or rely on (and disclose the source of) a contemporary description. If neither applies, then I don’t get to imagine the setting, but have to glide over details. Do descriptive details matter to the story? Sometimes. Sometimes not.

Stiles accurately states that the goal is to capture the feelings and spirit of the scene in your account, and that the writer brings his or her experience of life to that description. Two of my histories focus on trials — the impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson and Aaron Burr’s treason trial. Did my experience as a trial lawyer (even trying an impeachment before the U.S. Senate) help me portray those events? Absolutely.

But did it also help to be able to stand in the courtrooms where each of those essential contests took place. Absolutely.

The essential point for me is that if I have been to a setting and walked around in it, I gain confidence in my understanding of the moment, the people, the interests at stake, and the story I’m trying to capture. I may not be able to point to a specific sentence that is different because I traveled to a historic site, but that visit enhanced my confidence in the story and my ability to tell it. That’s worth going to some trouble for.

David McCullough (I think) pointed out that the writer of history has only a few windows on the past: the words left by the people who lived then, the implements they used and clothes they wore, the buildings they lived and worked in, and the landscapes they walked through. I want to look through all of those windows.

February 5, 2018

Misspelling: An American Tradition

Occasionally I despair over rampant, often intentional misspellings in the modern world. Doesn’t anyone, I rant inwardly, proofread any more?

proofread any more?

Was H&M being droll when it misspelled “genius” in the t-shirt on the left? I don’t think so. Perhaps that’s the correct spelling in Swedish.

And in the billboard on the right, the Miller Brewing Co. definitely did not mean to mangle “contradiction” so visibly.

Intentional misspellings are a decades-old tradition in the music business. Look no further than “Led” Zeppelin, the Byrds, or (more recently) Ludacris. Then there are websites like Tumblr, Digg, and Scribd, or consumer brands like Fruit Loops, Chick-fil-A, and Publix Supermarkets.

Americans have never been obsessive about getting the spelling right. For the book I’m working on now, I am reading a massive volume of George Washington’s correspondence and find the eighteenth-century approach to spelling extremely entertaining. George himself could be an indifferent speller, though his errors tended to be minor and even the result of writing a great many letters without the benefit of a “delete” key, much less auto-correct or spellcheck.

But some of Washington’s correspondents — particularly the crusty backwoodsmen he hired to execute his many schemes to acquire frontier lands — employed a delightfully freewheeling approach to spelling. In most instances, their misspelling produced a phonetically perfect rendition of the word, so I have no trouble figuring out what they meant. In some instances, their rendition of the word actually makes more sense than the “correct” spelling.

I offer a selection from letters Washington received in the first half of 1775, beginning with James Cleveland (May 12, 1775, April 10, 1775, June 7, 1775):

Fue = Few

Inbarcket = Embarked

Musk kingdom = Muskingum [a river]

Cannue = Canoe

sattes faction = satisfaction

Fort Blare = Fort Blair

menchioned = mentioned

From Valentine Crawford (March 23, 1775):

Emedently = immediately

enfortenet = unfortunate

acedence = accidents

From Gilbert Simpson (Feb. 6, 1775):

gane = gain

Curcumstans = circumstances

Butifull = Beautiful

The takeaway? Don’t forget to menchion these butifull ideas whenever you gather with a fue frens, in happy or enfortenet curcumstans. You will surtenly gane their respeck.

November 26, 2017

Trump: Haunted Anew by the Ghost of Andrew Johnson

More echoes of the benighted Andrew Johnson Administration of 1865-69 reverberate around President Trump with the current logjam at the top of the Consumer Financial Protection Board. Deputy Director Leandra English asserts the statutory right to direct the agency following the resignation of its director; claiming to act under a different law, President Trump has named Mick Mulvaney to serve as acting director.

The power of the past (Andrew Johnson) to haunt the present!

All of which hearkens back to the those halcyon days in early 1868 when the nation had two Secretaries of War. Edwin Stanton was appointed by Abraham Lincoln, confirmed by the Senate, and retained in office by President Johnson for almost three years. Unhappy with Stanton’s commitment to enforcing Reconstruction laws that aimed to assist the freed slaves, Johnson tried to fire Stanton in late 1867. Under the Tenure of Office Act, the Senate refused to confirm the dismissal, so Stanton remained in office.

In February 1868, Johnson tried again, this time ignoring the Senate and simply sending an interim appointee — the entirely forgettable General Lorenzo Thomas — to take over the War Department.

Sleeping on the Job

Stanton, however, refused to relinquish the office, or even leave the building. He slept in the office and ate his meals at his desk for nearly three months while his congressional allies impeached Johnson and placed him on trial in the Senate. The principal charge against Johnson was that his appointment of Lorenzo Thomas violated the Tenure of Office Act. That law (not accidentally) provided that any violation was a “high crime and misdemeanor,” copying the language of the Constitution’s impeachment clause

The legal situations are not entirely parallel. The English/Mulvaney showdown involves dueling claims under the CFPB’s authorizing statute (which provides that the deputy director serves as acting director when the top position is vacant), and the Federal Vacancies Reform Act (which gives the president authority to appoint fill vacant agency positions on an interim basis, pending Senate confirmation of a successor). Neither law states that violations are high crimes and misdemeanors. And the Tenure of Office Act was mostly repealed, then its remnants were invalidated by the Supreme Court in 1926 as unconstitutional (Myers v. United States).

There’s a stark political distinction between the situations, as well. Andrew Johnson faced a Congress dominated by political foes who desperately wished for his removal from office and the public scene. In contrast, today’s Republican-majority Congress has shown a steady devotion to the president.

Yet the factual similarity is weirdly evocative, a symptom of a polarizing chief executive and bitterly partisan times. Also, it arises just two months short of the 150th anniversary of the Thomas-Stanton showdown in the War Department’s offices, which I wrote about in Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln’s Legacy. That confrontation remains one of my favorite moments in American history — a moment more reminiscent of Monty Python than of the Federalist Papers. As recorded by a witness who transcribed the exchange, Thomas spoke first:

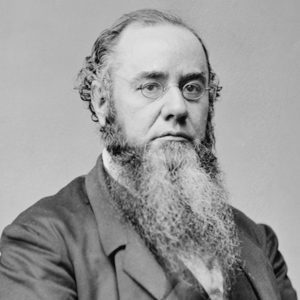

Incumbent Secetary of War Edwin Stanton

THOMAS: I am Secretary of war ad interim, and am ordered by the President of the United States to take charge of the office.

STANTON: I order you to repair to your rooms and exercise your functions as Adjutant General of the Army.

THOMAS: I am Secretary of War ad interim, and I shall not obey your orders; but I shall obey the orders of the President, who has ordered me to take charge of the War Office.

STANTON: As Secretary of War, I order you to repair to your place as Adjutant General.

THOMAS: I shall not do so.

STANTON: Then you may stand there if you please, but you cannot act as Secretary of War; if you do, you do so at your peril.

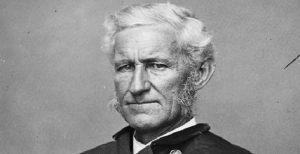

Wannabe Secretary of War Lorenzo Thomasril.

THOMAS: I shall act as Secretary of War.

Shortly after that ludicrous exchange, Thomas left. He attended Cabinet meetings for several weeks until Johnson faced reality. He appointed a permanent replacement for Stanton, General John Schofield, who proved acceptable to much of Congress. Thomas never got into the War Department office.

Oh, and Johnson was acquitted in his impeachment trial by a one-vote margin. Kansas Senator Edmund Ross cast the deciding ballot for acquittal. In my book, I concluded that Ross’ vote was purchased with cash or patronage promises or both, which is another story. . . .

For this week’s face-off at the CFPB, I certainly hope someone records any confrontation between English and Mulvaney. I can’t help but wonder if one of them will end up spending a few weeks barricaded in the building until the courts resolve the matter.

Which leads to the inevitable questions: Does English or Mulvaney have the key to the office? And which will arrive first in the morning?

July 31, 2017

My Ten Best Mystery/Thriller Writers

-- Not a lot of gore or mass violence. They’re distractions.

-- Smart, polished writing.

-- Close, loving attention to the people in the story, not just the story – unless the story’s totally amazing.

John le Carré — The master. From The Spy Who Came In from the Cold through The Russia House, Le Carré captured the tensions, hypocrisies, and terrors of the Cold War. With the fall of the Soviet Union, he reinvented himself, exploring the same themes around the globe in great yarns like The Constant Gardener, The Tailor of Panama, and Our Kind of Traitor. Witty, ironic, the Muse of Moral Ambiguity.

Elmore Leonard – The master, American version, who packed more description into fewer words than anyone. Try this character from Tishomingo Blues: “all the way cool.” You could use more words, but why? He did Detroit-based stories (Split Images, City Primeval), Florida stories (Maximum Bob, Out Of Sight) and anything he damn well pleased. Get Shorty may be perfect.

Eric Ambler – This British espionage writer created dense atmosphere, quirky characters, and compelling yarns. The early books (Journey Into Fear, The Mask of Dimitrios) explore devious men wandering through the world-gone-mad of fascism and communism. His later books widened his scope. A favorite is his last, The Care of Time (as in “time will take care of him”).

Eric Ambler – This British espionage writer created dense atmosphere, quirky characters, and compelling yarns. The early books (Journey Into Fear, The Mask of Dimitrios) explore devious men wandering through the world-gone-mad of fascism and communism. His later books widened his scope. A favorite is his last, The Care of Time (as in “time will take care of him”).Rex Stout

– I haven’t yet joined the Nero Wolfe Literary Society (yup, there is one!), but I can’t resist the fat epicurean sleuth who loves orchids and never leaves his Manhattan townhouse (well, hardly ever). Sidekick Archie Goodwin is the perfect counterweight (“weight,” get it?). Try The League of Frightened Men, or Too Many Cooks, or any of them.

– I haven’t yet joined the Nero Wolfe Literary Society (yup, there is one!), but I can’t resist the fat epicurean sleuth who loves orchids and never leaves his Manhattan townhouse (well, hardly ever). Sidekick Archie Goodwin is the perfect counterweight (“weight,” get it?). Try The League of Frightened Men, or Too Many Cooks, or any of them. Baroness (of course!) P.D. James (Baroness James, to us!) – A Scotland Yard investigator who writes poetry? What can I say – it works in her Adam Dalgleish books (Cover Her Face, The Private Patient). James also made time for a woman protagonist, An Unsuitable Job for a Woman. Thoughtful, carefully-observed stories that draw you in deeper and deeper.

Baroness (of course!) P.D. James (Baroness James, to us!) – A Scotland Yard investigator who writes poetry? What can I say – it works in her Adam Dalgleish books (Cover Her Face, The Private Patient). James also made time for a woman protagonist, An Unsuitable Job for a Woman. Thoughtful, carefully-observed stories that draw you in deeper and deeper. Olen Steinhauer – I know, I know, finally someone on this list who’s both alive and not yet eligible for senior discounts. In fact, Steinhauer’s still in his 40s. He’s hard for me to avoid, since his books appear on bookstore shelves just before mine (“Stei” comes before “Stew”. . .) and there are always quite a few more of his! Still, concentrating on spy stories, he has produced a great trilogy (I loved An American Spy) and excellent stand-alone books (try The Cairo Affair). The tension crackles, the intrigue is compelling. An entire book told through a single dinner between former colleagues? He pulled it off, beautifully, in All the Old Knives.

Olen Steinhauer – I know, I know, finally someone on this list who’s both alive and not yet eligible for senior discounts. In fact, Steinhauer’s still in his 40s. He’s hard for me to avoid, since his books appear on bookstore shelves just before mine (“Stei” comes before “Stew”. . .) and there are always quite a few more of his! Still, concentrating on spy stories, he has produced a great trilogy (I loved An American Spy) and excellent stand-alone books (try The Cairo Affair). The tension crackles, the intrigue is compelling. An entire book told through a single dinner between former colleagues? He pulled it off, beautifully, in All the Old Knives. Robert B. Parker – The Spenser books. I rest my case. One of the few recurring-character series that I just kept coming back for. They’re so good that new ones are still coming out even though Parker died seven years ago (written by Ace Atkins). The novels go down fast, with the smoothest pacing. Try Early Autumn or The Judas Goat.

Robert B. Parker – The Spenser books. I rest my case. One of the few recurring-character series that I just kept coming back for. They’re so good that new ones are still coming out even though Parker died seven years ago (written by Ace Atkins). The novels go down fast, with the smoothest pacing. Try Early Autumn or The Judas Goat.  Josephine Tey – Her novel The Daughter of Time showed that an investigator could unearth secrets from the historical past (in her case, the 15th-century killing of the princes in the Tower of London). That inspired my first mystery, The Lincoln Deception. Though I haven’t been crazy about her other books, Daughter of Time is perfect.

Josephine Tey – Her novel The Daughter of Time showed that an investigator could unearth secrets from the historical past (in her case, the 15th-century killing of the princes in the Tower of London). That inspired my first mystery, The Lincoln Deception. Though I haven’t been crazy about her other books, Daughter of Time is perfect. Arthur Conan Doyle – It’s crazy to have him down this low on the list. Sherlock Holmes will always be with us. Here’s a short list of Doyle’s legacy (1) The dog that didn’t bark. (2) There is nothing more deceptive than an obvious fact. (3) When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth. Great stuff. Not to mention the deerstalker hat, the pipe, the cocaine, the violin, the crazy older brother. Ah. . . .

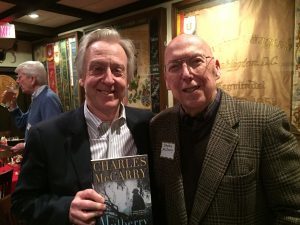

Arthur Conan Doyle – It’s crazy to have him down this low on the list. Sherlock Holmes will always be with us. Here’s a short list of Doyle’s legacy (1) The dog that didn’t bark. (2) There is nothing more deceptive than an obvious fact. (3) When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth. Great stuff. Not to mention the deerstalker hat, the pipe, the cocaine, the violin, the crazy older brother. Ah. . . . Charles McCarry – Another espionage writer, also alive (!). McCarry’s first novel, The Miernik Dossier, was extraordinary. His novel about the Kennedy assassination, The Tears of Autumn, is the best guess I’ve seen as to what happened in Dallas in November 1963. Also nice, I’ve met him (he lives in northern Virginia), and he’s a charming guy.

Charles McCarry – Another espionage writer, also alive (!). McCarry’s first novel, The Miernik Dossier, was extraordinary. His novel about the Kennedy assassination, The Tears of Autumn, is the best guess I’ve seen as to what happened in Dallas in November 1963. Also nice, I’ve met him (he lives in northern Virginia), and he’s a charming guy.That’s my list so far. Great writers didn’t make the cut: Raymond Chandler, John D. MacDonald, Walter Mosley, Alan Furst, Dashiell Hammett, Agatha Christie. Hey, it’s MY list. Who’s on yours?

Ten Best Mystery/Thriller Writers

Wrapping up my blog tour for my historical mystery, The Babe Ruth Deception, I want to honor ten mystery/thriller writers who made me want to write that type of book. The list reflects my tastes, freely acknowledged here:

Not a lot of gore or mass violence. They’re distractions.

Smart, polished writing.

Close, loving attention to the people in the story, not just the story – unless the story’s totally amazing.

Ex-spook, brilliant spy and thriller writer, John Le Carre.

John Le Carre — The master. From The Spy Who Came in From the Cold (1963) through Russia House (1989), Le Carré captured the tensions, hypocrisies, and terrors of the Cold War. With the fall of the Soviet Union, he reinvented himself, exploring the same themes around the globe in great yarns like The Constant Gardener (2001), The Tailor of Panama (1996), and Our Kind of Traitor(2010). Witty, ironic, the Muse of Moral Ambiguity.

The “Dickens of Detroit,” Elmore Leonard

Elmore Leonard – The master, American version, who packed more description into fewer words than anyone. Try this character from Tishomingo Blues: “all the way cool.” You could use more words, but why? He did Detroit-based stories (Split Images, City Primeval), Florida stories (Maximum Bob, Out of Sight) and anything he damn well pleased. Get Shorty may be perfect.

Eric Ambler – This British espionage writer created dense atmosphere, quirky characters, and compelling yarns.  The early books (Journey Into Fear, The Mask of Dimitrios) explore devious men wandering through the world-gone-mad of fascism and communism. His later books widened his scope. A favorite is his last, The Care of Time (as in “time will take care of him”).

The early books (Journey Into Fear, The Mask of Dimitrios) explore devious men wandering through the world-gone-mad of fascism and communism. His later books widened his scope. A favorite is his last, The Care of Time (as in “time will take care of him”).

Rex Stout – I haven’t yet joined the Nero Wolfe Literary Society (yup, there is one!), but I can’t resist the fat epicurean sleuth who loves orchids and never leaves his Manhattan townhouse (well, hardly ever). Sidekick Archie Goodwin is the perfect counterweight (“weight,” get it?). Try The League of Frightened Men, or Too Many Cooks, or any of them.

Baroness (of course!) P.D. James

P.D. James – A Scotland Yard investigator who writes poetry? What can I say – it works in her Adam Dalgleish books (Cover Her Face, The Private Patient). James also made time for a woman protagonist, An Unsuitable Job for a Woman. Thoughtful, carefully-observed stories that draw you in deeper and deeper.

Olen Steinhauer – I know, I know, finally someone on this list who’s both alive and not yet eligible for senior discounts. In fact, Steinhauer’s still in his 40s. He’s hard for me to avoid, since his books appear on bookstore shelves just before mine (“Stei” comes before “Stew”. . .) and there are always quite a few more of his! Still, concentrating on spy stories, he has produced a great trilogy (I loved The American Spy) and excellent stand-alone books (try The Cairo Affair). The tension crackles, the intrigue is compelling. An entire book told through a single dinner between former colleagues? He pulled it off, beautifully, in All the Old Knives.

Robert B. Parker – The Spenser books. I rest my case. One of the few recurring-character series that I just kept coming back for. They’re so good that new ones are still coming out even though Parker died seven years ago (written by Ace Atkins). The novels go down fast, with the smoothest pacing. Try Early Autumn or The Judas Goat.

Josephine Tey – Her novel The Daughter of Time showed that an investigator could unearth secrets from the historical past (in her case, the

Josephine Tey, who inspired my first book.

15th-century killing of the princes in the Tower of London). That inspired my first mystery, The Lincoln Deception. Though I haven’t been crazy about her other books, Daughter of Time is perfect.

Arthur Conan Doyle – It’s crazy to have him down this low on the list. Sherlock Holmes will always be with us. Here’s a short list of Doyle’s legacy (1) The dog that didn’t bark. (2) There is nothing more deceptive than an obvious fact. (3) When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth. Great stuff. Not to mention the deerstalker hat, the pipe, the cocaine, the violin, the crazy older brother. Ah. . . .

Charles McCarry – Another espionage writer, also alive (!). McCarry’s first novel, The Miernik Dossier, was extraordinary. His novel about the Kennedy assassination, The Tears of Autumn, is the best guess I’ve seen as to what happened in Dallas in November 1963. Also nice, I’ve met him (he lives in northern Virginia), and he’s a charming guy.

Charles McCarry and me, celebrating his most recent novel.

That’s my list so far. Great writers didn’t make the cut: Raymond Chandler, John D. MacDonald, Walter Mosley, Alan Furst, Dashiell Hammett, Agatha Christie. Hey, it’s MY list. Who’s on yours?

July 19, 2017

Tools of Historical Fiction

Through the three historical mysteries in my “Deception” series – # 3, The Babe Ruth Deception emerged in paperback last month – I’ve turned to some unexpected tools for grounding each story in the proper time-and-place.

Because the books range from 1900 (The Lincoln Deception) to 1921 (Babe Ruth), and take place variously in small-town Ohio, Washington, Paris, and New York, each one has involved different challenges. If readers don’t believe the book’s version of the era and the location, the story doesn’t have a chance. Happily, some tools work in any situation.

Photographs – These are invaluable guides to personal clothing (how uncomfortable were they?), hair styles, and deportment (how formal did people wish to appear?). Photos of cities reveal how they looked a century ago: the traffic, the buildings, the commercial offerings. Photos of Manhattan streetscapes in the early 1900s showed a surprising (to me) lack of women who were out and about. All were escorted by men. When it comes to landscapes and vistas, even current photos may be helpful.

Finally, photographs are essential for any real historical figures who appear in the story (say, Babe Ruth or President Woodrow Wilson in The Wilson Deception). The Babe’s disarming grin, Wilson’s triumphantly erect posture – these come through powerfully in photos. The story has to portray historical figures as they were, and as they’re known. I have distilled this inarguable point: you can make up a lot, but Abe Lincoln HAS to be tall.

Babe Ruth, 1920 — check out his posture, his expression: he knows he’s the best!

Films and audio recordings – For my first novel, set in 1900, there were no films available, but I could see film of Woodrow Wilson and hear his voice on tape. Watching a person move can reveal much, including the impact that person may have on others; the same is true of hearing his voice, cadence, and speech patterns.

Babe on the Silver Screen!

For Babe Ruth, I hit the jackpot. Not only are there many recordings of his voice, but the Babe made his own silent movie in 1920, Headin’ Home (you can watch all of it online here). It’s a pretty bad movie, but it offers a great look at the 25-year-old Babe, before he put on weight and suffered the dings and aches that come with age and an athletic career. The movie also gave me a key plot line for the novel, since one of New York’s most notorious gangsters financed the film, then was indicted for bribing eight members of the Chicago White Sox to throw the 1919 World Series . . . but I shouldn’t give away the story!

Places – Being at the actual location of the story can give an immediacy – the sounds and light around a place, or the impact of a building’s design on the eye. For The Babe Ruth Deception, I visited the Wall Street shrine of J.P. Morgan Co., where a terrorist bombing took place in 1920, and also the Ansonia Hotel on Broadway in Manhattan (below, now deluxe condos), where the Babe lived in arriviste splendor.

Novels! – For the writer of historical fiction, one puzzle is everyday speech: what words people used, what kinds of slang was current, and how they put words together. To get a feel for such things, I like to read novels written during the period. To learn about 1920 speech patterns, I turned to Main Street by Sinclair Lewis and This Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald. Having the story in 1920 gave me a small advantage. My mother, born in 1917, had a virtually inexhaustible supply of sayings, slang and piquant phrases. If I was tempted to put into a colloquial phrase into a character’s mouth, I tried to imagine my mother saying it. If I could hear her it in her voice, I used it.

A final point. Though I rely on historical research (and always include an Author’s Note to explain what events in the story are real) it’s important not to overdo it. It’s fiction, after all. Novelists use their imaginations, and so do readers. Edgar Rice Burroughs made a fortune with his Tarzan books, yet never set foot in Africa, while Frank Herbert wrote six novels about the universe of Dune without ever visiting that planet.

Prolific novelist Lawrence Block captured this idea in his book Writing the Novel:

All our stories are nothing but a pack of lies. Research is one of the tools we use to veil this deception . . .but this is not to say that the purpose of research is to make our stories real. It’s to make them look real, and there’s a big difference.