David O. Stewart's Blog, page 4

September 22, 2016

Babe Ruth: Know your enemy!

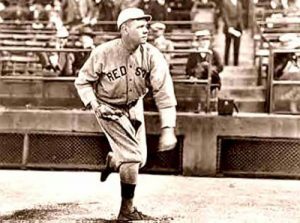

Babe Ruth was a great pitcher before he was a great hitter. Doesn’t it seem likely that one of the reasons he was a great hitter was because he had been a great pitcher?

Playing for the Boston Red Sox from 1915 to 1918, the Babe was probably the best left-handed pitcher in the American League. He won 78 games and lost only 40, racking up an E.R.A. of 2.28 for his entire pitching career. He was fabulous in clutch situations, setting a record that stood for decades by pitching 29 consecutive scoreless innings in World Series games.

By the 1919 season, though, the Babe was getting restless. He wanted to play every day. He thought he could make more of a contribution as a hitter and outfielder, and have more fun, too.

In the 1919 season, he split his time between pitching and the outfield, setting a new home run record with 29 shots out of the park, but also going 9-5 as a pitcher. That was enough to persuade the Babe. He wanted to play outfield full time and if that meant leaving Boston, then so be it. He campaigned to be traded, and the Red Sox accommodated him by selling his contract to the New York Yankees.

The rest is the stuff of legend. Blasting 54 homers in his first season with the Yanks and 59 in his second, Ruth transformed baseball. He inserted the power game into what had been predominantly a scrappy, singles-and-stolen-bases game.

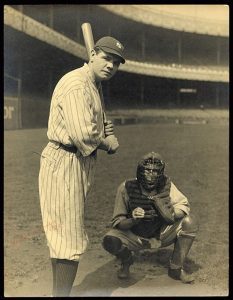

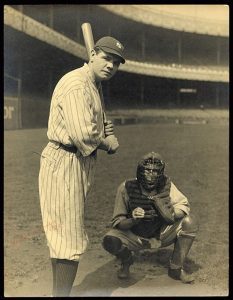

Babe Ruth in 1920, his first full season with the New York Yankees, when he hit 54 home runs.

But he also hit for high averages, finally retiring with a lifetime batting average of .342. He was an amazing hitter.

But I wonder if he didn’t have a terrific advantage as a hitter because he had been a star pitcher? A huge part of hitting is guessing what the pitcher is going to throw (fast ball? curve? slider?) and where he’s going to throw it (inside/outside? high/low?). As said by the man who broke the Babe’s career home run record, Henry Aaron, “Guessing what the pitcher is going to throw is eighty percent of being a successful hitter. The other twenty percent is just execution.”

It stands to reason that someone who has been a pitcher at an elite level, as Babe Ruth was, will have special insight into a pitcher’s strategies. A hitter with that experience — a hitter like Ruth — has walked in the other guy’s moccasins. He should be able to read signs of fatigue, mental and physical. He should be able to suss out the individual pitcher’s reliance on certain pitches and pitch locations in critical moments.

It’s as though one of our generals in Afghanistan had spent five years fighting as part of a Taliban cell. Wouldn’t that provide a remarkable advantage in figuring out the other enemy’s tendencies and preferences?

I’ve read widely about Ruth without ever seeing a claim by the Babe that he consciously used his experience as a pitcher while he was up at bat. Nor have I seen any baseball analyst emphasize that experience in explaining Ruth’s extraordinary career as a hitter. But it makes sense to me.

Babe Ruth: Sleeping with the Enemy?

Babe Ruth was a great pitcher before he was a great hitter. Doesn’t it seem likely that one of the reasons he was a great hitter was because he had been a great pitcher?

Playing for the Boston Red Sox from 1915 to 1918, the Babe was probably the best left-handed pitcher in the American League. He won 78 games and lost only 40, racking up an E.R.A. of 2.28 for his entire pitching career. He was fabulous in clutch situations, setting a record that stood for decades by pitching 29 consecutive scoreless innings in World Series games.

By the 1919 season, though, the Babe was getting restless. He wanted to play every day. He thought he could make more of a contribution as a hitter and outfielder, and have more fun, too.

In the 1919 season, he split his time between pitching and the outfield, setting a new home run record with 29 shots out of the park, but also going 9-5 as a pitcher. That was enough to persuade the Babe. He wanted to play outfield full time and if that meant leaving Boston, then so be it. He campaigned to be traded, and the Red Sox accommodated him by selling his contract to the New York Yankees.

The rest is the stuff of legend. Blasting 54 homers in his first season with the Yanks and 59 in his second, Ruth transformed baseball. He inserted the power game into what had been predominantly a scrappy, singles-and-stolen-bases game.

Babe Ruth in 1920, his first full season with the New York Yankees, when he hit 54 home runs.

But he also hit for high averages, finally retiring with a lifetime batting average of .342. He was an amazing hitter.

But I wonder if he didn’t have a terrific advantage as a hitter because he had been a star pitcher? A huge part of hitting is guessing what the pitcher is going to throw (fast ball? curve? slider?) and where he’s going to throw it (inside/outside? high/low?). As said by the man who broke the Babe’s career home run record, Henry Aaron, “Guessing what the pitcher is going to throw is eighty percent of being a successful hitter. The other twenty percent is just execution.”

It stands to reason that someone who has been a pitcher at an elite level, as Babe Ruth was, will have special insight into a pitcher’s strategies. A hitter with that experience — a hitter like Ruth — has walked in the other guy’s moccasins. He should be able to read signs of fatigue, mental and physical. He should be able to suss out the individual pitcher’s reliance on certain pitches and pitch locations in critical moments.

It’s as though one of our generals in Afghanistan had spent five years fighting as part of a Taliban cell. Wouldn’t that provide a remarkable advantage in figuring out the other enemy’s tendencies and preferences?

I’ve read widely about Ruth without ever seeing a claim by the Babe that he consciously used his experience as a pitcher while he was up at bat. Nor have I seen any baseball analyst emphasize that experience in explaining Ruth’s extraordinary career as a hitter. But it makes sense to me.

September 8, 2016

Why Do Babe Ruth Movies Mostly Suck?

With less than three weeks to go until my novel concerning Babe Ruth debuts, The Babe Ruth Deception, I find myself wondering why Babe Ruth movies are so bad. In fairness, though, not all of them are terrible, at least not when he wasn’t the focus of the film.

He played himself in The Pride of the Yankees, which starred Gary Cooper as the doomed teammate, Lou Gerhig. Babe portrayed himself pretty well in a solid tear-jerker.

The Babe and Coop on the set of “Pride of the Yankees.”

He also appeared in a well-regarded Harold Lloyd silent movie in 1928, Speedy, again portraying himself in a cameo role.

He starred in Babe Comes Home, a 1927 silent movie for which no print has survived — a fact that suggests it wasn’t hugely entertaining.

The film industry’s other encounters with the Babe have been horrifying.

A 1920 silent film, Headin’ Home, stars the Babe as — you guessed it — a baseball star. The film is an hour long but seems way longer. It has its fascination, though, since Babe was only 25 when it was filmed so he actually looks like the stud athlete he was, not the dissipated, pot-bellied caricature of himself that he became in later years. And the story behind the movie — in particular the mobsters who bankrolled it — inspired the plot of my novel.

Unwatchable: John Goodman in “The Babe.” A friend should have talked Goodman out of this one.

Unwatchable: John Goodman in “The Babe.” A friend should have talked Goodman out of this one.So why hasn’t the big screen yet captured the Babe? I think it was the Babe’s fault. He liked to play the clown, tousling the hair of tykes, winking at the dames, drinking and smoking way too much. The caricature public image of him became indelible. Not many think of him as the sleek, powerful athlete he was until he turned thirty and began to pack on a few pounds.

It’s too easy for moviemakers to seize on his superficial qualities and too hard for them to think about how this kid from a terrible family background in a lousy part of Baltimore willed himself to become a world-class athlete and ultimately a mythical figure. That’s an incredible story, but you won’t find it in any movie.

August 8, 2016

BabeWatch: Barnstorming Against Negro League Teams

Partly because he loved to play baseball, partly because he loved to spend money, Babe Ruth played lots of exhibition games in the offseason across the country and in the Caribbean. After his astonishing 1921 season, the formed the Babe Ruth All Stars, which played against multiple Negro League teams, including the Kansas City Monarchs and the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants.

Babe Ruth in 1920, his first full season with the New York Yankees, when he hit 54 home runs.

This brought immediate conflict with the new baseball commissioner, Kennesaw Mountain Landis, former federal judge brought in to clean up the game after the Black Sox Scandal about fixing the 1919 World Series. To choke of these interracial match-ups, Landis decreed that no (white) major leaguers participate in those exhibition games.

The Babe’s response? He kept playing the games, meeting commitments for contests against teams like Oscar Charleston’s Colored All-Stars in the Spring of 1922.

Sometimes called the “black Ty Cobb,” Oscar Charleston hit .434 in 1921 with the St. Louis Giants.

The commissioner’s response? He suspended Ruth and Yankee teammate Bob Meusel and pitcher Wild Bill Piercy for the first 39 games of the season until the wayward ballplayers agreed to respect his decree.

In working on my forthcoming novel, The Babe Ruth Deception (releases Sept. 27; preorders available), I became particularly smitten with the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants, a squad whose owners included two black businessmen and Atlantic City political power Nucky Johnson, played by Steve Buscemi in Boardwalk Empire. Reflecting the scrabbling quality of much of Negro League the team’s home fields in 1921 were actually in Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field and the Bronx. They played Babe Ruth’s All Stars after the 1920 season and beat them, 9-4. Their best pitcher was Cannonball Dick Redding, while Dick Lundy led them in hitting.

Cannonball Dick Redding

Shortstop Dick Lundy of the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants.

I found the intersection between the Babe and Negro League baseball pretty remarkable, and explored it in my novel — which was natural, since one of my lead recurring characters is a former black baseball player, Speed Cook. The Babe was no crusader for equal rights. He was a ballplayer first, last, and always, and a largely uneducated one at that. Yet, unlike the Lords of Baseball, he had no problem taking the field against or with African-Americans.

And he made a difference. Landis had to rescind his decree barring exhibition games against Negro League players, and Ruth played more of them after the 1922 season. With his season shortened by the suspension, he only hit 35 home runs and batted only .315 — substantial reductions from his gaudy numbers in 1921 (59 homers and .378) — but he made his point.

Throughout his life, and until now, there was always a whispering campaign that Ruth was part black. I haven’t seen any reason to credit those whispers, but I wonder if they made the Babe more aware of the lives and burdens of black ballplayers of his era. And more willing to defy Commissioner Landis.

August 4, 2016

Theater of the Near-Real: Cop Chases in L.A.

It’s completely weird.

They can go on forever, the only time Southern California TV stations never break for commercials. The first one on Monday morning lasted more than two hours. Later in the day, a second one lasted two hours.

It sounds mind-numbing. Helicopter cameras track a single car speeding down interstates and freeways while a reporter estimates the speed of the vehicle, the nature of the roads coming up, the risks the driver is running, the time elapsed in the pursuit, and any other drivel he or she can dream up to fill the time.

The chopper reporters like to speculate if the police will deploy the dreaded “spike strips,” the kind that rental car lots use with signs that say DON’T BACK UP OR THE WORLD WILL END! By puncturing the fugitive’s tires, the spike strips add the spice of watching someone try to speed on metal wheel rims, a strategy doomed to bright sparking failure. Spike strips are tricky, though. You don’t want innocent civilians driving over them at high speeds.

The cops generally don’t get crazy during these feature presentations. They know they’re on TV. They stay close, waiting for the driver to run out of gas or adrenaline.

The final apprehension is the most dangerous moment. After being surrounded by squad cars, the first driver on Monday, a woman, just sat in her locked car with the tinted windows up. The police had to punch out the window to shout orders at her. If I had been one of those officers, I would have been seriously keyed up.

The thing is, most of the drivers haven’t done anything real bad, certainly nothing that 95 percent of the television viewers haven’t done in the last six months. They’ve been driving erratically. Check. They might have imbibed an extra brew or two before getting behind the wheel. Check. They are often distraught over something gone wrong in their lives. Check.

But these people make the terrible decision that when a police car summons them to pull over, the smart move is to floor it and head for Encino or San Diego or Fullerton or wherever they imagine they know the roads better than the cops do. What are they thinking?

When they run, the TV choppers swarm like gnats to bring uninterrupted coverage of these non-events.

Nowhere else in the world does this happen — that is, nowhere else in the world do thousands of people sit transfixed by this compelling circus of the unimportant. It started with O.J. Simpson and the Ford Bronco chase in 1994, but it shows no sign of letting up.

Nobody draws a crowd like OJ Simpson did on June 17, 1994.

On Monday, during an eight-hour stretch in a hospital waiting room (you don’t want to know the details and I don’t care to recount them), I watched two of these weird spectacles. God help me, I couldn’t look away. It combined elements of a California Tour de France — hey, look, that’s Burbank! — with Hawaii Five-O (“Book ’em, Dano, failure to signal”).

And at its core is the compelling realization that the poor sap behind the wheel, who could be you if you lost a few dozen IQ points overnight, is totally messing up his or her life, live!, on regional TV!

One question, of course, is why L.A.? Mary Melton in Los Angeles Magazine offered some answers four months ago: “the LAPD’s aggressive pursuit policy (which is under review by the police commission), the city’s horizontality, an abundance of freeways, advances in camera technology, and a competitive TV news market that encourages imitation rather than innovation.” She left out the nice weather, which makes for clear flying weather and sharp camera images.

But let’s not overthink this thing. It’s great TV. Next time you’re in LA, check it out. For that matter, you can live-stream it on the device you’re looking at right now.

April 20, 2016

Hamilton’s Pulitzer Prize: Listen to the Words

Lin Manuel Miranda as Alexander Hamilton

Now that he’s won the Pulitzer Prize for it, maybe we’ll pay attention to the words of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton, the genre-smashing Broadway hit that costs a monthly car payment to attend. When we listen to the words – really listen – we can appreciate his achievement.

Magic can happen when story and words and music meet, when a single artistic vision commands eye and ear and imagination. That’s the secret of opera’s survival despite its preposterous qualities, and also of Hamilton. But there’s more to Miranda’s creation.

A bemused neighbor recently explained that her middle-school-aged children are obsessed with Hamilton. This is a show about a Treasury Secretary who died two centuries ago, a show the kids know only from Internet snippets and the double-CD version (which recently nestled in the top 20 on the Billboard chart, ahead of Taylor Swift, Drake, and a range of pop icons).

Yet these young people in suburban Maryland, my neighbor related, sing the songs to each other and in groups. “You be Jefferson,” they call out, “you be Burr, and I’ll be Hamilton.”

I was dazed. I write history and speak about it to groups with median ages that hover in the low 70s. Is Miranda’s mix of rap, blues, and torch songs making history hip in 2016?

And make no mistake: Miranda’s version of the early Republic’s history is remarkably accurate. Not perfect, but compared to a Hollywood production, it’s astonishing how close he hews to the events – major, minor, and mundane – of Hamilton’s tumultuous life.

Credit Miranda with knowing dramatic gold when he opened Ron Chernow’s biography of Hamilton. A poor immigrant orphan from the West Indies who succeeded by sheer brilliance, Hamilton was good at everything he tried – law, politics, war, finance.

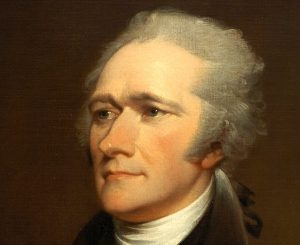

The real Hamilton

Yet, perhaps inevitably for a man with such a trajectory, Hamilton had glaring weaknesses. How many national leaders publish a lengthy pamphlet detailing his extra-marital affair? Or die in a quarrel over intemperate words that he might easily have withdrawn?

The key to the show’s power is that Miranda doesn’t confine himself to depicting this smorgasbord of one man’s powers and flaws, but finds the universal in it.

Start with his insights into politics. When Aaron Burr, Hamilton’s mirror image, advises the bumptious immigrant to “talk less, smile more,” political consultants can only smile and nod. When Burr sings that he wants to “be in the room where it happens,” he reveals the underside of ambition: the desire to do good often twins with the lust to be at the center, to know the secrets.

A rueful moment arises when James Madison and Thomas Jefferson share their dismay over Hamilton’s dominance in George Washington’s government. It sure would be nice, they sing in the lament of those who lack a key ally, to have “Washington on your side.”

But Miranda also finds in Hamilton’s story the thrills and pain of every life. “Helpless,” sung by the Schuyler sisters when they meet Hamilton, is a cheery celebration of young love. According to my informant, the middle-school set favors it. Miranda explores the nature of sisterhood through the two women’s lives, both enamored with Hamilton yet always loyal to each other.

Tragedy sat on Hamilton’s shoulder. A sense of transience hurried him. Miranda has that, too, and lets us know it. “Death doesn’t discriminate,” he warns in the first act, “it takes and it takes and it takes.”

Hamilton’s mother dies of fever. His eldest son falls in a duel. The parents’ moving anthem of loss hinges on a humdrum, slightly formal six-syllable word – “unimaginable” – to capture a pain that will never leave.

Finally, Miranda celebrates words as the only weapons against oblivion. The finale trumpets the importance of “who keeps your flame, who tells your story.” The cry that throbs through the show is the howl of the writer, the vow to “write like you’re running out of time.” Because when your time comes up, the question is “whether you’ve done enough.”

Hamilton did. Miranda, too.

(This commentary appears simultaneously in the Washington Independent Review of Books.)

March 15, 2016

Of Charles Sumner, David Donald, and Used Bookstores

The young Charles Sumner

The serendipity of the used bookstore — its ability to provide unexpected pleasures — is gaining attention recently. Even the Washington Post (owned by Amazon billionaire Jeff Bezos) has noticed. I offer Exhibit A in support.

Last month, at the recently-expanded Rockville store of the Friends of the Library of Montgomery County, I snapped up a copy of Charles Sumner and the Coming of the Civil War, by David Donald.

Okay, it’s not for everyone, but this book scratched a couple of itches I had almost forgotten I had. First, the abolitionist Sumner has been an elusive figure for me. He’s most famous as an orator in the Senate in the Civil War era, but oratory is a talent that does not survive well from the pre-film age. He’s also famous for being caned on the Senate floor by a Southern congressman, Preston Brooks, who was enraged by Sumner’s insulting remarks about a relative. Sumner suffered serious injuries, which the medical profession of the day made much worse.

When I researched Sumner for my book on the Andrew Johnson impeachment trial, Impeached, I was surprised to find that the Massachusetts senator was such a non-factor in the impeachment process and in Congress. He held himself aloof from the legislative process and wrote virtually no legislation. He had little influence with his peers. So why was he so famous? For getting beaten up? It puzzled me.

I may have galloped through David Donald’s biography of Sumner as part of my research, but research for a book is not the same as pleasure reading. When I’m researching a book, I’m looking for information that can inform or undermine my understanding of events. I’m not savoring the book.

Historian David Donald

That David Donald took the trouble to study Sumner and write about him — in a 2-volume biography, no less — was intriguing, but so are many subjects. I never circled back to read the book at leisure.

A word about Professor Donald. Historians’ work tends not to survive their lives. There’s always someone else willing to write about the same subject and the later work will often seem more current and better-informed. The march of progress and all that. Yet Donald’s work commands attention still. His one-volume biography of Lincoln is the absolute best book on that topic that I know. It’s comprehensive, thoughtful, sympathetic, warm, and not exhausting.

And on a personal note, Donald wrote a generous evaluation of my Impeached, just a few weeks before his death in 2009, so I have harbored warm feelings toward him ever since.

What would this wise student of history do with the puzzle of Charles Sumner? I was delighted to find that he approached his subject with a bracing candor. He didn’t exalt his subject, even prominently featuring a contemporary judgment that Sumner was slow in debate, “never ready at a retort, [and] tacked slowly, like a frigate, when assaulted.”

Sumner also was “almost impervious to a joke,” which helps explain why I never warmed to him. In Donald’s words, “If a sense of humor is a handicap in American political life, Sumner was singularly unencumbered.” Sumner himself boasted that he had never made a joke in any of his hours-long orations: “You might as well,” he said, “look for a joke in the book of Revelations.”

So why did Sumner matter? In Donald’s telling, Sumner proved to be a perfect expression of Boston’s moral denunciation of slavery, even though much of the Boston aristocracy disliked him. He was a fine orator, though Donald emphasizes that none of his speeches included a new idea. Sumner processed and promoted the ideas of others.

And only Sumner was so self-righteous, and so tone-deaf to interpersonal relationships, that he was willing to insult Southern slaveholders until one lost his self-control entirely and made Sumner a national martyr. Though not a skilled political player on the national scene, he became a symbol of the abolitionist cause. Symbols can be very powerful.

And that’s why used bookstores are so great! You never know what you may find.

February 15, 2016

The Time Justice Scalia Caught Me Out

The death last weekend of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia brought to mind the time when he turned over a stone in the legal rockpile only to reveal an awkward bit of half-smart maneuvering by me — though until now my name was never publicly associated with it.

The case involved the Equal Access to Justice Act (EAJA), a law that allows small businesses and individuals opposing the federal government to recover some of their attorney fees if they prevail and if the government’s position was not “substantially justified.” Promptly, a lot of ink was spilled over the meaning of “substantially justified.”

I wandered into the situation on behalf of my father, who was a fervent advocate on behalf of small businesses — he thought they are the bedrock of democracy, innovation, and most of what is good in the world. (For then-Sen. John Kerry’s tribute to The Old Man, go here.) EAJA was up for reenactment and The Old Man hoped to have Congress lower the barrier to fee recovery by softening the term “substantially justified.”

Nominally representing a few small business groups — but really representing my father — I testified before Congress with this message and pressed it in meetings with committee staff. There was no way, I learned, that Congress would change the statutory wording.

So I moved to Plan B. How about the committee report that would issue with the legislation? Maybe the report could embrace the softer, more generous interpretation of “substantially justified”? Ah. That was easier. In went the language. The Old Man was mollified. Better half a loaf, right?

Shortly later, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit issued an EAJA decision. In a separate concurrence, then-Judge Scalia wrote with withering contempt of the lonesome bit of legislative history I had secured (Hirschey v. Federal Energy Regulatory Comm’n, 777 F.2d 1), comparing its weight to that of an “equivalently unreasoned law review article”:

“I frankly doubt,” he wrote, “that it is ever reasonable to assume that the details, as opposed to the broad outlines of purpose, set forth in a committee report come to the attention of, much less are approved by, the house which enacts the committee’s bill. And I think it time for courts to become concerned about the fact that routine deference to the detail of committee reports, and the predictable expansion in that detail which routine deference has produced, are converting a system of judicial construction into a system of committee-staff prescription.”

Ouch. That the judge was dead right didn’t make the experience any less mortifying. I felt so . . . violated!

What about all the other stray bits of unwarranted legislative history out there? Of all gratuitous legislative history accompanying all the obscure statutes produced by all the legislative bodies in the world, why did Scalia have to choose mine to pick on?

Over nearly the next 30 years, Scalia continue to fulminate against relying on legislative history that can’t be tied to the legislators actually voting on a bill. In all of those cases that I didn’t work on, I agreed with him.

How did my father take the episode? With a shrug. He was in it for the long haul. We’ll get ’em next time, he said.

February 4, 2016

Putting on the Show: Eight Rules for Book Talks

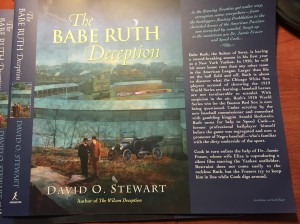

The cover for “The Babe Ruth Deception,” which will release on September 27.

One of the surprising parts of writing books, for me, has been the amount of performance involved — I mean performance: standing up and putting on a show.

My experience is, of course, framed by the kind of writer I’ve become. I’m “midlist,” which is a term that describes all the writers who fall between those who sell gazillions of books and those who can’t get their books published. Publishers expect midlist writers to go out and hustle the books.

They’d prefer that I started tweeting and Instagramming and built a huge online following. Or for me to have a cable TV show commanding millions of viewers. Or for my books to be made into major films or serialized TV shows. So far, none of those things has happened.

So what’s left is to slap me in front of a room to sing and dance (figuratively speaking). My standard gig is about 45 minutes with extra time for questions. Perhaps not surprising for an ex-trial lawyer, I enjoy putting on the show and the shows have been well-received. (If you want to reach your own decision on that claim, go to the pages on this website for individual books, where I’ve linked to some videos and podcasts; or hunt a couple up on YouTube.)

All this book-talking takes time. I have seventeen speaking dates set up for the last eleven months of 2016. The majority of those will address one of my two most recent books (Madison’s Gift and The Wilson Deception) but two will talk about earlier books and four are on unique subjects. And we haven’t even started booking events to promote my newest historical mystery, The Babe Ruth Deception, which will release on September 27.

Having done roughly two hundred of these shows, I herewith offer a few rules about them.

Bring a LOT of energy to the show — Others may be able to do the low-key thing and get audiences to hang on every word. Not me. Before I start, I give myself a mental kickstart. No Jeb Bush. As we all know from being in audiences, it’s easy to drift into thoughts about the rest of your life, or even fall asleep (the ultimate punishment for a dull speaker). Demand their attention, politely.

Distill, distill, distill — It can be difficult to figure out how to boil down a 100,000-word book. Do it. You can’t talk about everything, so figure out the most important things. When I prepared to talk about my first book, The Summer of 1787, I was surprised by how different the book seemed when I tried to boil it down. A book talk is not a recitation of the book. Leave a lot out.

Be funny early — Figure out something funny to say in the first five minutes. Better yet, figure out several funny things to say early in your talk. Humor wakes people up. It gets them feeling good about you and about their decision to be in that room. Everyone likes to laugh.

Tell them what they’re going to hear — We’ve all heard the truism about the three stages of an oral presentation: first you tell the audience what you’re going to tell them; then you tell them; then you tell them what you just told them. Sometimes truisms are true. This one is.

Use images, pictures, maps — Powerpoint gets a bad rap these days as a crutch for the presenter, but when used well, it’s great! Pictures tell a lot. When I say that President Andrew Johnson had no sense of humor, a picture of the old sourpuss reinforces the point. When I want to get across how War I remade the map of Europe and the Middle East, nothing matches the map of 1914 showing the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Russian Empire, and the Ottoman Empire; four years later, all were gone.

Pay attention to the room — Read the audience. You can tell when they’re jumpy, when they’re bored. Body language tells you everything. Sometimes you may lose them. My worst experience was with a roomful of Citadel cadets who had been up and doing difficult things for fourteen hours before being forced to attend my talk. They were not interested. They were barely conscious. So I quit early and opened it up for questions. No need to prolong the agony.

Don’t read from the book (unless it’s expected) — Reading from the book is tough to do well. There’s a tendency to drone, or rush, or just mess it up. It also takes your eyes off the audience (see previous rule) and has the potential to make you cringe in public when you read an unfortunate sentence that someone else must have fiendishly inserted in your book. Sometimes, though, audiences for fiction writers expect to be read to. In those cases, I always (i) keep it short, and (ii) edit the passage again so I won’t cringe in public.

Stay out of most bookstores — Bookstores are among the best places in the world, but not for book talks. But unless it’s your “home” bookstore, or unless it’s a store that’s really really good at turning out some bodies, you’re going to get a small, disengaged group that won’t buy books. Much of the time, you’re better off home sending out tweets.

January 12, 2016

Making President Clinton’s Reading List

It’s not the best photo of me that’s ever been taken, but there are definite virtues to this one, particularly President Clinton’s savvy placement of the copy of Madison’s Gift that I presented to him.

It’s not the best photo of me that’s ever been taken, but there are definite virtues to this one, particularly President Clinton’s savvy placement of the copy of Madison’s Gift that I presented to him.

Our conversation? I said that I imagined that he had not found time to read Lynne Cheney’s biography of Madison. He smiled broadly and said, “I did not.” I presented Madison’s Gift as a superior alternative.