David O. Stewart's Blog, page 6

March 10, 2015

Truthiness Triumphant!

At page 117 of my novel about the John Wilkes Booth Conspiracy, The Lincoln Deception, a character laments that the Union and Confederate armies failed to join together at the end of the Civil War to mount invasions of Canada and Mexico. “A terrible missed opportunity,” he complains at page 118.

I had no historical basis for the interlude. It seemed like something that some people might have considered in 1865. My goal wasn’t truth so much as “truthiness” (to borrow from Stephen Colbert). You know, it’s a novel. Fiction.

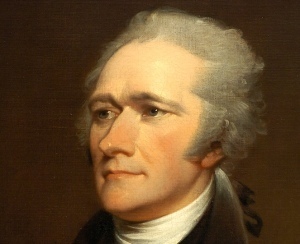

Senator Zachariah Chandler of Michigan

So imagine my surprise yesterday to find in the Reminiscences of Senator William Stewart of Nevada, the recollection that in the closing days of the Civil War, Senator Zach Chandler urged exactly the same invasion scheme that I imagined for my character (p. 178):

“I propose that we take an appeal to President Lincoln,” he [Chandler] said, “signed by influential men, to call an extra session of Congress, and send two hundred thousand trained veterans into the British possessions north of us; one hundred thousand picked troops from the Federal Army, and the same number from the flower of Lee’s army. I have thought of this seriously for weeks, and I shall make every effort to bring it about.” He was intensely in earnest, . . .

The goal, in my novel and in Senator Stewart’s memory, was to join North and South in a common enterprise to expand and enrich the nation.

Senator Stewart (no relation to me) states that thirty of the fifty senators in office agreed to support Chandler’s idea, but the Lincoln assassination effectively removed it from consideration.

Senator William Stewart of Nevada

Truthiness? You bet!

January 25, 2015

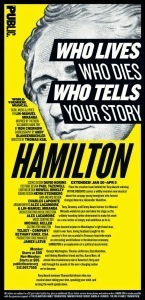

New “Hamilton” Show in NYC: HipHop Hooray!

Nah, I don’t listen to hiphop. Not ever. But Lin-Manuel Miranda is building a beautiful bridge between that music and old farts like me with his new “Hamilton” musical, which has opened for previews at the Public Theatre in New York. I caught the show last night with the Girl of My Dreams, and was blown away. If you can get to New York in the next couple of months, you’ll curse yourself for not seeing this one. (Its run has been extended to early April.)

Several years ago, Miranda performed the title song of the show for the Obamas at the White House, and that knocked me out. But that was a pale preview of the entire show — it’s way better to get it all.

The songs are powerful, the dancing’s exciting, the overall energy level is spectacular, and the underlying story of Hamilton’s life is almost beyond belief. I took a shot at encapsulating the Hamilton saga in my first book, The Summer of 1787, about the Constitutional Convention:

“Slim and handsome, always dressed with meticulous style, he was an admired (if lengthy) speaker, spouting perfectly formed paragraphs and exuding a vital charisma. Hamilton’s oratory was the stuff of opera — as was his life story. Born to unmarried parents on an obscure island in the West Indies, Hamilton was effectively orphaned in his early teens. . . Arriving in New York without family connections or wealth, Hamilton rose like a rocket.”

“In matters of government, Hamilton was a prodigy. . .. Writing his first newspaper essay when he was twenty, Hamilton made his pen a mighty weapon, producing diatribes, monumental reports, and incisive analyses. He wrote in five months more than fifty of the essays in the landmark Federalist series, and was arguably the most prolific advocate on political issues this nation has seen. Jefferson invoked biblical diction when he noted ruefully, ‘Without numbers, he is an host unto himself.'”

“Hamilton’s fall would be a spectacular as his rise, combining a sordid public adultery, a mortifying loss of political influence, and the death of his twenty-year-old son in a tragic duel. The final act was his own death at age forty-eight in an equally senseless duel with that cynical archvillain, Vice President Aaron Burr. Pure opera.”

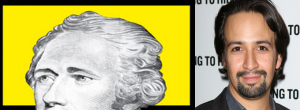

Hamilton & Miranda

Miranda not only portrays Hamilton in this show, but also wrote the nearly three dozen songs and the story (based on the outstanding Hamilton biography by Ron Chernow). Some of the songs have unpromising titles like “The Adams Administration,” and “The Election of 1800,” but they’re uniformly fabulous. Indulge me in highlighting a few highlights:

Miranda has great fun with his portrayal of King George III, who may have the hottest show-stopper of the evening, “You’ll Be Back.” Luckily, the rueful monarch gets two reprises, and he’s uniformly great.

Miranda’s political insights are sharp. When he has Aaron Burr sing of his overpowering desire to be in “The Room Where It Happens,” he captures the ambition that drives political figures. When Jefferson, Madison and Burr frolic happily because Hamilton has self-destructed politically (see “sordid public adultery,” above), he allows us to wallow in the elation that is part of the addictive drug of the life political.

Miranda also digs into his characters’ personal lives — falling in love, having children, losing children. As I’ve written about Hamilton, Miranda is way too young to be this smart. His depiction of Hamilton’s complicated relationship with Washington is spot-on.

Notably, the show doesn’t demonize Aaron Burr; indeed, Miranda allows Burr to be a three-dimensional figure and even (on occasion) sympathetic. As the author of a book on Burr (one I hope is clear-eyed about his virtues and weaknesses), American Emperor, I was impressed by how close Miranda came to being fair to a man who is easy to portray as a “cynical archvillain.” Indeed, the show is more fair to Burr than is the Chernow biography.

In short, the history in this show is remarkably good. Not perfect, of course. It muddles the run-up to the Hamilton-Burr duel, in significant ways. The show takes other liberties with history — the ones I noticed were mostly occasional flipping of chronology –but they didn’t bother me.

Don’t wait any longer. Get your tickets! This is an outstanding show.

November 24, 2014

The Emerging Indian Colossus

A 10-day visit to India this month kindled thoughts about a part of the world I have known only through novels and Merchant/Ivory movies.

The ambitions and dreams of the place are huge. Indian newspapers speculate avidly about a second Indian mission to Mars. (Did you even know about the first one, completed just two months ago?) I was blown away by a tour of a new planned city, Naya Raipur, being built in Chhattisgarh province, an obscure area of heavy industry and relatively backward “tribal” peoples. Rising from the plains of Naya Raipur are solar arrays, carefully planned infrastructure, lakes, recreational areas, and mixed commercial, office, and residential developments. It’s an immense undertaking to build an entirely new city of a half-million people, and they’re doing it.

Administrative buildings in new city of Raya Naipur

New hospital being built in Naya Raipur

India’s diversity is stunning. In ten days of traveling, we passed through areas in which the dominant local tongues were – in no particular order – Telugu, Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi, and Chhattisgarh. And there are many more, though English remains the language of business throughout the nation.

The physical realities of India are daunting. The air pollution is catastrophic. New Delhi has replaced Shanghai as the urban area with the worst air quality on the planet. New Delhi air makes sinuses burn and has to have severe health effects. Like London in the 1880s, or Pittsburgh in the 1950s, the atmosphere is simply poisonous.

Committed to a coal-fired future, India may single-handedly cancel out the efforts of every other nation on earth to control climate change. In the photo from February 2013 below, smog envelops the giant India Gate landmark in New Delhi.

Indian roads are often inadequate, public transport overwhelmed, and basic utility services inconsistent, at best. My wife, Nancy Floreen, asked the mayor of a large Indian city what his major priority is. “Drainage,” he answered. The day before, a woman in that city drowned in an overflowing drainage ditch.

The emergence of a large prosperous class in India underscores the brutal poverty of the nation’s majority. One-room squatters’ huts of plastic and scrap wood crouch next to modern mid-rise buildings.

In plush urban hotels, the capacious public washrooms were larger and dramatically more comfortable than the living quarters of the attendants who offered me hand towels with unfailing courtesy. In Chhattisgarh state, home to new-city Naya Raipur, fourteen women died this month from tainted drugs in government-sponsored sterilizations.

Every day’s newspaper brought fresh revelations of official corruption. While in Chhattisgarh, we read about the deputy head of the housing commission who used his public office to amass eighteen bank accounts, five houses, nine retail establishments, and large stocks of gold, jewelry, and silver.

The caste structure of old India persists and thwarts social mobility. The oppression of women is everywhere visible. They sweep streets with brooms made of ragged sticks, and grub in gardens in filthy clothes. On six domestic airline flights, we rarely saw an Indian female other than flight attendants. More seriously, the tradition persists of “honor killings” when a woman dishonors her family by, for example, marrying below her caste; an estimate 1,000 such killings occur every year.

Yet the ambition, talent, and sheer size of India (1.3 billion people) create the potential for great achievements. The nation’s unwieldy democratic processes – it is the largest democracy on the planet – has finally yielded a majority government with an energetic leader (Narendra Moti) who is goading the nation to clean up corruption and itself. On our tour, we met a range of impressively competent, urbane, and well-trained businesspeople, scientists, and professionals. On the flight home, we ran into two Washington-based acquaintances who had been in India on business. India is on the move.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Leon Trotsky had the insight that nations that come late to modernization can leapfrog developmental steps that pioneers had to trudge through. Modern telecommunications is an example of Trotsky’s “law of uneven and combined development.” Nations like India never developed a wired telephone industry. Instead, they used mobile phone service to jump over that step. Indians are madly working to make many more such leaps.

A final thought about this remarkable place. To survive in a crowded, clawing society, its people develop extraordinary skills. Road traffic is a grinding war of all-versus-all. Four-lane highways accommodate as many as seven lanes of traffic among drivers who don’t flinch until another vehicle threatens immediate annihilation. Indeed, Indian drivers fall into only two categories: (i) excellent ones, and (ii) dead ones. There is no middle ground. Pedestrians are almost always at risk.

An Indian man traveling with us suggested that his nation’s linguistic diversity and traffic madness actually foster a culture of gifted computer code writers. On the streets, they must remain aware and alert around all 360 degrees of the compass. To navigate through their world, they must master the grammar and structure of multiple spoken languages. Those skills, he argued, are essential traits for good code writers.

Keep an eye on India. Great and terrible things will continue to come from there.

November 2, 2014

One Perilous Joy of the Season

I vividly recall the Christmas morning. My father opened the book I had carefully picked out for him. I hadn’t read it, but I thought it would be perfect for him, neatly matching his interests. He looked at the spine, regarded the cover, and said, “I enjoyed this very much when it first came out.”

Not a good moment, but the beginning of a lifetime of mistakes — and occasional successes — in selecting books as gifts.

My column this month at the Washington Independent Review of Books takes a lighter look at the risks of giving books for the holidays.

October 5, 2014

Why F. Scott?

F.Scott Fitzgerald

This morning brings the inaugural installment of a monthly piece I’ll be writing for the Washington Independent Review of Books. The subjects will be what I’m reading, writing, or thinking about. This morning’s effort puzzles over the bafflingly inflated reputation of F. Scott Fitzgerald. I don’t get it. . . .

September 3, 2014

Five Books on Impeachment

The conservative-inspired “Impeach Obama” campaign will wax and wane over the next two political years, a weird residue of the benighted effort to impeach President Bill Clinton fifteen years ago. Even though the Impeach Clinton effort failed somewhat ignominiously, it has empowered true believers of the Left and Right to think of impeachment as an ordinary tool of American politics.

Thus, as the administration of President George W. Bush limped through its final days, liberal Democrats in Congress introduced resolutions to investigate his impeachment, or to flat-out impeach him. By 2008, liberal gadfly Dennis Kucinich of Ohio worked to force a vote in the House of Representatives on his claims that Bush’s foreign invasions based on false efforts (“he lied us into war” in Iraq) warranted his removal from office.

Now it’s President Obama’s turn. Impeachment advocates, including Sarah Palin, recite a laundry list of executive actions by Obama that supposedly exceeded his constitutional powers and justify impeachment and removal from office: actions on immigration policy, lies about Obamacare health insurance coverage (“if you like your coverage, you can keep it”), and launching the United States into “war” in Libya.

That these efforts have been doomed is a blessing for our constitutional government, yet they all reflect a fundamental confusion about what impeachment involves. That confusion has persisted in American government since the Constitution was ratified in 1788. The core of the problem is the constitutional standard for impeachable offenses — that the accused federal office-holder have committed “treason, bribery, or high crimes and misdemeanors.” “Treason” and “bribery” are never the issue. But what the heck are “high crimes and misdemeanors”? [Answer at the end of this post.]

My engagement with impeachment has been long and fairly intense. I defended a federal judge from Mississippi in a Senate impeachment trial and then filed a lawsuit challenging the Senate’s trial procedures in Nixon v. United States, a case that I ultimately argued (and lost) before the U.S. Supreme Court. And I wrote a book, Impeached, about the 1868 impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson, in which Johnson won acquittal by a single vote in the Senate.

For those seriously interested in the question of impeachment beyond the demagoguery of the moment, I recommend the following five books:

Impeached, by moi — What did you expect me to recommend? The Johnson impeachment was a confusing mess. The accusations against him seemed picayune, yet the passions of the impeachers were titanic: they believed the fate of the Union and the outcome of the Civil War turned on Johnson’s trial. Dark men prowled Washington’s streets with satchels of money, looking for Senators to bribe on the impeachment vote. Somehow, the opaque impeachment clause of the Constitution brought about a peaceful resolution of a bitter national crisis.

President Andrew Johnson

Impeachment: A Handbook, by Charles L. Black, Jr. — Not so much a book as a quiet conversation with a thoughtful constitutional law professor at Yale. Black lucidly explains each of the elements of the impeachment process and what they aim to achieve. I don’t agree with all of his conclusions, but it’s a valuable book.

Impeachment: The Constitutional Problems, by Raoul Berger — In many ways, this volume is the polar opposite to Black’s. Berger disagrees with Black on several points and occasionally loses his way in hoary English impeachment precedents from medieval days. Meaning no disrespect to Berger, I find his book most valuable for proving that historical analysis of English impeachment will never solve the fundamental problems of making sense of impeachment under the U.S. Constitution. You may conclude otherwise.

The Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson, by Michael Les Benedict — A notable work because Benedict was willing to say out loud that President Johnson should have been impeached. He spends a good deal of time analyzing congressional voting patterns in the 1860s, but you can skip those sections.

The Breach: Inside the Impeachment and Trial of William Jefferson Clinton, by Peter Baker — Despite the occasional journalistic hyperventilation, this examination of the Clinton impeachment train wreck provides an agonizing dissection of how the nation careened into its continuing infatuation with presidential impeachment.

OK, now my thoughts on “high crimes and misdemeanors”: they must be an abuse of the president’s constitutional powers that justify his removal from office, though they need not be a crime. Lots of crimes are penny-ante. Take the Clinton case. President Clinton lied under oath about his sex life. I abhor his lie. It was not, however, an abuse of his official powers.

Is that subjective? You bet. Although impeachment is dressed up in judicial processes, it is a profoundly political act: Congress removes the elected leader of the nation, the only public official elected by the entire nation. You don’t impeach and remove a president because you don’t like his policies. So long as he can reasonably claim that he acted within his powers — even if a reasonable case can be made that he didn’t — then he should not be impeached.

July 8, 2014

WWI: Who was the enemy?

As the World War I centennial continues to gear up, and as I slouch to the end of my novel on the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, I have stumbled upon the most remarkable French memoir of the war – Poilu. (Thanks to Andy Dayton for recommending it.)

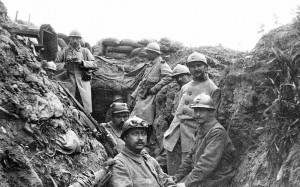

World War I soldiers in a Western Front trench.

Louis Barthas was a barrelmaker in the Languedoc region of Southern France in the summer of 1914, when he was called into the army. A 35-year-old father of two small boys, Barthas was a committed socialist who plainly had a solid education. For the next 54 months — that’s four and one-half years — Barthas served in the French infantry. Remarkably, he endured some of the bloodiest battles of the Western Front, including Verdun. Through that whole time, he kept a journal of his experiences. His fellow soldiers knew about his journal and urged him to tell the real story of life in the trenches for the French poilus (“the hairy ones,” because they grew whiskers).

Barthas’ journal was first published in France in 1978, and only this year has been translated into English. Like any journal, it has a good bit of repetition. Also, every day was not as interesting as every other day. But the overall impact of the book was, for me, profound. Barthas — who never rose above corporal and never aspired to rise as far as corporal — makes it clear that his principal enemies for four and one-half years were French commanders, not German soldiers.

Along the way, Barthas relates some of the things we know intellectually about trench warfare, but which he makes vivid and unavoidable.

Building a good trench is important, and a tremendous amount of work. Every rainfall prompts hours of effort to repair damage to the trench. He describes a trench at the beginning of the war, “before the Germans showed us just how to make them”: “A wide, shallow stream at the bottom. No protective barbed wire. No parapets, no loopholes [to shoot through]. No firing step. No trace of a shelter for us.”

The living conditions were unimaginable, requiring the soldiers to get used to “the cannon’s roar, the musty smell of rotten flesh, the fat venomous flies, the ticks, the worms, the rats, everything unclean and impure that swarms and flourishes in a charnel house.”

Some scenes were so vile that they would make Hieronymous Bosch shrink away in shame. In an attack on a German trench, Barthas found “An unfortunate fellow was stretched out, decapitated by a shell. . . Beside him, another was frightfully mutilated. . . [a few steps beyond] I see, as if hallucinating, a pile of corpses, almost all of them Germans, that they had started to bury right in the trench. . . . ‘There’s no one here but the dead!’ I exclaimed. . . I finally found some living souls, with haggard eyes, leaning on each other in threes and fours like frightened beasts, not even looking around.”

Burying his own dead: “We only had six corpses to get rid of, and they were very close to the trench. . . . You pushed the cadaver into a shell hole, tossed a few shovelfuls of earth on top, and on to the next one.” Barthas had to collect the identity tag from each corpse, rifling pockets and slicing chains. “It seemed like a profanation to us, and we spoke in whispers as if we were afraid of waking them up.”

Barthas offers powerful observations on the nature of the war he fought for so long.

“In a war like this one, combat meant mostly being a target for [artillery] shells. The best leader wasn’t the cleverest tactician, but rather the one who knew best how to keep his men alive.”

“We were hardened against any emotion. We cared only about our own fates. War is the best teacher of egoism.”

Barthas was uniformly contemptuous of his own officers — the colonels, captains, and lieutenants (save for one) who lurked back in well-built dugouts and tents, “holed up in a bunker, ear stuck to a telephone.” One captain led his unit in every direction but the correct one, prompting Barthas to observe, “the poor guy read his map like a carp reading a prayer book.” The poilus, he insisted over and over again, did not fight “because of patriotism, or to defend the rights of peoples to live their own lives, or to end all wars, or other nonsense. It was simply by force, because, as victims of an implacable fate we had to undergo our destiny. . . . At the slightest hint of revolt we would be ground to bits.”

But at times the soldiers did revolt, on both sides of the trench line. He recounts an episode in the fall of 1915 when his unit, drenched by a cold rain, was poised to press an attack. The order came to move forward. “The men started to protest violently at word of this order. They didn’t have any spirit of adventure. They weren’t curious at all. The sergeant was perplexed. I suggested that he respond this way: ‘The men ask that the section chief lead them at the head of the column.’” After considerable passing of messages between those poised to attack and their commanders in the rear, the attack was called off.

When the French military police (the “gendarmes”) cracked down too hard on soldiers for slipping away from their posts to buy food from nearby villages, the soldiers did not hesitate to respond. “One day they found two gendarmes swinging from the branches of a pine tree, with their tongues hanging out. From that moment, the poilus could go get food in the neighborhood without worrying about a thing.”

The common soldiers on both sides accommodated each other on a number of occasions recorded by Barthas. In December 1915, when the rain was so heavy that trenches overflowed, both Germans and Frenchmen had to climb out or drown. “We therefore had the singular spectacle of two enemy armies facing each other without firing a shot.” Both sides were careful not to shoot at the other’s kitchens and food personnel, recognizing their common interest in letting “the peaceful cooks go about their business in peace at their kettles.”

On another occasion, a German soldier blundered into Barthas’ trench and a French soldier prepared to throw a grenade at the intruder. “I held his arm. I will always be faithful to my principles as a socialist, a humanitarian, even a true Christian, even if they cost me my life, of not firing on someone unless in legitimate self-defense. And was it in our interest to break the neighborly relations which existed between our two adjoining outposts?” The German turned and ran.

In the summer of 1916, Barthas’ unit was again posted very close to German trenches. Too close to fight, as it turned out: six meters away. In the area, “calm and tranquility” reigned. Soldiers “smoked, others read, some wrote, a few squabbled.” Indeed, “the French and German sentries [were] seated tranquilly on their parapets, smoking pipes and exchanging bits of conversation from time to time, like good neighbors.” When the French learned that their officers were going to order them to open fire on their “good neighbors,” the poilus warned the Germans to take cover.

Sent out on patrol against German lines, the poilus became adept at fabricating tales for their officers. On one occasion, a patrol reported that a new poison gas was devastating the German lines, even though they poilus had never reached the German trenches. “That made our big bosses happy,. . . as well as the scouts, who all came back at such little risk.”

In 1917, when their commanders demanded that the French patrols bring back German prisoners for questioning, the poilus were equal to the challenge. Returning empty-handed, “everyone swore that the Boches [Germans] simply wouldn’t surrender, and they were forced to kill every last one of them.”

In the early summer of 1917, news of the Russian Revolution against the tsar caused “a wind of revolt [to] blow across almost all the regiments.” Barthas’ regiment elected a “soviet” of three men from each company to take command. Barthas was selected, but refused the honor. “I had no desire to shake hands with a firing squad, just for the child’s play of pretending we were the Russians.”

Barthas helps explode the myth of the implacable German soldier who always fights to the death. In late summer of 1916, his unit captured an entire German unit which, after deciding it was “useless to defend themselves, unanimously raised their arms, crying ‘Comrades! Comrades!” After gathering up the prisoners, the poilus found the body of a German officer, “his head bashed in, and beside him a shovel covered with blood. It seemed clear that, when he didn’t want to surrender, his men had gotten rid of him.”

Barthas’ own survival was very close to a miracle. He recounts a dozen occasions on which his sense of danger caused him to shift position, thereby saving his life and often those of his fellows. He lived long enough to see the next war in France, during which his son served in the French Resistance, and died in 1952. In all of his journals, though, Louis Barthas never describes an occasion when he killed an enemy soldier.

May 21, 2014

World War I: Fragging Officers and PTSD?

The sequel to my historical novel, The Lincoln Deception, is set at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. Accordingly, I’ve been doing some considerable reading about World War I and the peace treaty that proved to be “The Peace to End All Peace,” as some have it. Recent forays into two American novels about The Great War have proved fascinating and surprising.

In Three Soldiers (1921), John Dos Passos drew on his own extensive experience of the war. In 1917-18, he drove an ambulance in Northern Italy and then in Paris. His novel is unreservedly antiwar and steeped in a matter-of-fact social realism combined with the occasional romantic over-writing of a young man. (Dos Passos was 25 when the book was published.)

John Dos Passos

Early passages in Three Soldiers record the dehumanizing nature of military training. I found he had violated Stallard’s First Law of Fiction: that the greatest risk in portraying a boring situation is that you will succeed, thereby boring the pants off the reader. [Credit to Wayland Stallard.] Happily, things heat up when his characters near the battlefield, but no one is allowed to be heroic in the world of Dos Passos. Battle sequences are phantasmagoric, unreal, and largely bereft of opposing soldiers, though there’s plenty of fear, disorientation, and hostile artillery bombardment. The core of the book, it seemed to me, was the American soldiers’ experience of France — French culture, French people, and the brutal losses endured by the French, who had the entire bloody mess in their front parlors for four-plus years.

It’s not a great book, but a powerful one well worth reading. For me, the shocking part occurs during a battle when one of the three featured soldiers stumbles upon an American officer he has not liked throughout the book. The officer, wounded, asks for help. No one else is around. The soldier lobs a grenade at him and blows him up.

Wow. This was 1921! My own coming of age coincided with the Vietnam War, which I did not experience due to a high lottery number in the draft. During that war, I was fascinated by reports of “fragging” of American officers and sergeants by their own soldiers; tossing fragmentation hand grenades into the officer’s sleeping quarters. It seemed a shocking measure of the unwisdom of that war, the alienation of the men supposed to fight it, and (possibly) the inexperience of Army leaders.

It turns out that such incidents have been documented back into the early 1700s, though pretty rarely. Soldiers, after all, are armed and have been trained to use weapons. They can certainly turn those weapons on their own leaders — e.g., the Russian Revolution of 1918. By including such an episode in Three Soldiers, involving true blue Americans, Dos Passos assured the controversy that his book ignited.

Willa Cather

Willa Cather won the 1923 Pulitzer Prize for Literature for her World War I novel, One of Ours. As a huge fan of her My Antonia, and a considerably smaller fan of Death Comes for the Archibishop, I was intrigued that she had won a big prize for a novel I had never heard of.

Her experience of the war had to be very different from that of Dos Passos. When America entered the contest, she was 44, an established novelist and managing editor of McClure’s Magazine in New York. As near as I can tell, she stayed in America during World War I, but traveled to France in 1920 and toured battlefields from the war.

Perhaps not surprisingly, most of One of Ours doesn’t involve service in the army, but rather concerns a coming-of-age on the Nebraska Plains. The hero, Claude Wheeler, feels and understands more than the wooden-headed and wooden-hearted farmers all around him. Naturally enough, such a sensitive flower of a person makes a hash of his life. He fails to finish college, slinks back to the family farm, and marries a really wrong woman. I was psychically screaming “No, No” at Claude at several parts of the book. Nebraska farms are familiar territory for Cather, and her characters and setting are compelling and engaging.

When Claude finally gets into the war, he blossoms. Like Dos Passos, Cather emphasizes the impact on American soldiers of an extended exposure to France, French people, and an entirely different culture. When Claude finally dies in action — that disclosure doesn’t spoil the book for you, believe me, because it’s crystal clear throughout the book that Claude’s not going to survive the novel — his death is both heroic and meaningful. In short, it’s the sort of borderline sappy, sentimentalized battlefield death scene that would have caused Dos Passos to reach for his revolver.

BUT, then Cather threw me a curve. The novel wraps up with a brisk review of how the home folks deal with Claude’s death, and adds this amazing (to me) passage on what we now would call PTSD. Claude’s mother thinks:

“One by one the heroes of that war, the men of dazzling soldiership, leave prematurely the world they have come back to. Airmen whose deeds were tales of wonder, officers whose names made the blood of youth beat faster, survivors of incredible dangers — one by one they quietly die by their own hand. Some do it in obscure lodging houses, some in their office, where they seem to be carrying on their business like other men. Some slip over a vessel’s side and disappear into the sea.”

Cather completely blindsided me with that unsentimental look at the mental and emotional toll of war. Of course, “shell shock” was widely known during and after World War I, and certainly described what we now call Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. And soldier breakdowns under the stresses of war have always been known. But Cather gets full marks for recognizing it.

Interesting books. Worth a lo0k.

March 23, 2014

Nine Breeds of Historical Fiction

[This piece first appeared in the Washington Independent Review of Books]

Historical fiction is flourishing, and its advantages are many. For readers, it combines the familiar with the unknown, as novelists imagine the motivations and thoughts of historical figures. For writers, it provides grounding. Certain characters are already known and even defined. Better yet, the real world produces the most improbable characters. What fiction writer would dare create a character so complex and powerful as Abraham Lincoln? Yet historical fiction comes in many flavors. Here, for starters, are nine:

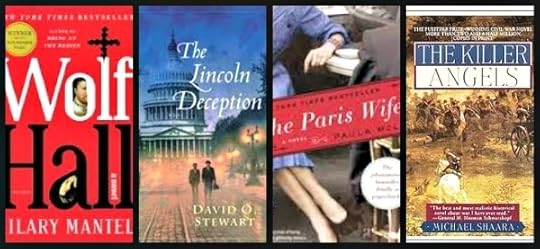

Straight-up. Like Shakespeare’s history plays, some historical fiction offers a straightforward imagining of an event through real and fictional characters, placing the reader in the center of it. Because the novelist can supply characters’ thoughts and motivations, not to mention entertaining dialogue, the resulting story often goes down more smoothly than historical narratives, which cannot stray from the facts. That was certainly true for Michael Shaara’s brilliant rendering of the Battle of Gettysburg in

The Killer Angels

, or E.L. Doctorow’s retelling of the Dutch Schultz gangster story in

Billy Bathgate

.

Straight-up. Like Shakespeare’s history plays, some historical fiction offers a straightforward imagining of an event through real and fictional characters, placing the reader in the center of it. Because the novelist can supply characters’ thoughts and motivations, not to mention entertaining dialogue, the resulting story often goes down more smoothly than historical narratives, which cannot stray from the facts. That was certainly true for Michael Shaara’s brilliant rendering of the Battle of Gettysburg in

The Killer Angels

, or E.L. Doctorow’s retelling of the Dutch Schultz gangster story in

Billy Bathgate

.

Inside-out. Some historical novelists take the heroes and scoundrels of history and flip them. Hilary Mantel’s smashing success with Wolf Hall and Bring Up The Bodies begins with her audacious suggestion that St. Thomas More was a narrow-minded, mealy-mouthed cleric, while his antagonist — the oft-reviled Thomas Cromwell — was a statesman of vision and integrity. Gore Vidal employed this gambit repeatedly. His Burr celebrates the duelist and alleged traitor, while Hollywood portrays Warren G. Harding as a shrewd and wise political leader, and 1876 plumps for the excellence of President Ulysses Grant.

Upside-down. Some novelists refuse to settle for reinterpreting history: they change it, opening readers’ minds to the what-might-have-beens. Often called “alternative history,” these include Stephen L. Carter’s intriguing The Impeachment of Abraham Lincoln, which wonders how things might have turned out if Lincoln had survived the bullet at Ford’s Theatre. Robert Harris’ Fatherland imagines a Europe after Nazi victory in World War II. In The Plot Against America, Philip Roth asked what America would have become if Charles Lindbergh had run for — and won — the presidency in 1940.

The Rosencrantz Maneuver. First popularized by Tom Stoppard in his takeoff of “Hamlet,” “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead,” this maneuver exalts a bit player in a large drama, simultaneously cutting the heroes down to size and offering readers a new window into the story. In The Blood of Heaven, Kent Wascom intriguingly reworked the Aaron Burr story (that man again) through the eyes of the brothers Kemper, who are only occasionally remembered for raising hell in the short-lived Spanish colony of West Florida.

Historical Mysteries. Pioneered by Josephine Tey, these books set fictional characters on the trail of an historical mystery, often from another era. In Tey’sThe Daughter of Time, a Scotland Yard detective in 1950 unravels the mystery of the 1483 murder of the underage King Edward V in the Tower of London. My own effort, The Lincoln Deception, sets a pair of mismatched investigators on the trail of the John Wilkes Booth conspirators and whoever was behind them.

Historical Crime-Fighters. A popular breed of historical novel places the crime thriller back in time, with a key historical figure at the center. Louis Bayard’s The Pale Blue Eye explores a murder in New York City that includes the struggling Edgar Allan Poe, while Daniel Stashower’s Harry Houdini Mysteries uses the magician and escape artist to solve baffling crimes.

Novelists’ Wives. There’s no denying the recent spate of books telling the interior stories of those long-suffering women yoked to writer-husbands. There’sThe Paris Wife by Paula McLain (Hemingway), and three about Zelda Fitzgerald: Therese Anne Fowler’s Z, R. Clifton Spargo’s Beautiful Fools, and Erika Robuck’s Call Me Zelda.

The Grand Sweep. These are the wrist-breakers, the door-stoppers, that purport to tell you everything you might possibly want to know about a nation, region, or city. Edward Rutherfurd’s London and Paris. James Michener’s Poland and Texas and Chesapeake. From one generation to the next, often-wooden characters from a single family land repeatedly in the center of pivotal events. Not often done well. [Thanks to M.K. Tod for noting the importance of this breed.]

Fictional Historical Fiction (Historical Fiction Fiction?). An impressive range of novelists place their stories in someone else’s novel — that is, the author borrows the setting and characters of the first novel and vamps on it. Jane Austen is so regularly honored (and pillaged) in this fashion that one website puts out an annual list of the “Top 20 Jane Austen-Inspired Books.” In March,Geraldine Brooks followed the wartime career of the long-absent father from Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, while Ahab’s Wife, by Sena Jeter Naslund, imagines the story of the stay-at-home wife of Melville’s unforgettable ship captain.

So, which breeds have I missed?

January 5, 2014

Fear of the Shallows

Looking back over the year just ended, I am struck by the proliferation of door-stopper books. This phenomenon — which afflicted both fiction and non-fiction — emerged in many of the most celebrated books which logged impressive sales numbers. To cite just a few:

Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, a novel checking in at 784 pages.

In biography, The Kid: The Immortal Life of Ted Williams, by Ben Bradlee, Jr., tilting the scales at 864 pages.

Wilson, by Pulitzer Prize winner Scott Berg, covering the life of our 28th president in 832 pages.

Doris Kearns Goodwin’s long-awaited The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism, a taut 910 pages.

Man Booker Prize winner The Luminaries, by Eleanor Catton, which offers 848 pages of fiction.

Charles Moore’s Margaret Thatcher: from Grantham to the Falklands, which is only the first volume of a biography of Mrs. Thatcher, yet still fills 896 pages.

Perhaps the most breathtaking of all, the first volume of Victoria Wilson’s A Life of Barbara Stanwyck: S teel True, 1907-1940, which devotes 1,056 pages to the first portion of the film actress’ life; by my count, Ms. Wilson requires an average of 32 pages for every year Stanwyck’s early life.

I should hasten to add that I have read none of these books and accordingly cannot offer any opinion on their merits or demerits. I am struck, however, by their length. I will confess that the length of a book is a factor in my decision to purchase and/or read it. Only yesterday, I lingered in a bookstore over a book on a subject of interest to me. I hefted the volume. I looked at the size of the print. And I put it back on the shelf. I might have been game for 300 pages on that subject, but not 500.

So, I approach this subject like the protagonist in the Bob Dylan song: ”You know something is happening here, but you don’t know what it is: Do you, Mr. Jones?” Why such long books?

Having four of my own books in print and with a fifth delivered last month to the editor, I have established that I will never write a book of such heroic dimensions. This is not a particular matter of pride. I suspect that I lack the attention span to produce a true door-stopper. Plainly, there are many readers out there who are prepared to lose themselves for a long time in an immense book, or at least aspire to doing so, or perhaps wish to be seen by their peers as doing so. And there are, I freely acknowledge, Big Subjects. Woodrow Wilson, for example, of the Golden Age of Journalism. Indeed, for whatever reasons, these large volumes are selling and are popular. I am interested, though, in why so many long books are written, and have a few tentative thoughts on the subject.

First, cutting one’s deathless prose can be most unpleasant. Faulkner famously counseled writers to “kill your darlings” — that is, to be especially ruthless about getting rid of those passages in which you take the most pride, because they are usually pretentious and full of writerly look-at-me. To paraphrase something that (I think) Elmore Leonard said: he always cut anything that seemed like writing.

Leaving things out can be very difficult for non-fiction writers. If you spend long enough on a subject, you can lose some perspective about what is interesting; everything about [Barbara Stanwyck, or Ted Williams, or whatever subject] has become interesting to you. Everyone should be interested in it! Moreover, you will likely recall just how difficult it was to fill in some ellipsis in the historical record, or what inventive research strategy and series of penetrating inferences revealed the truth which lesser writers had missed, and those memories makes it doubly painful to cut those passages. But leaving stuff out is one of the reasons writers pull down the big bucks. Or so I have thought.

I offer a second, slightly more subtle reason, that may help explain the door-stopper phenomenon. Some of my worst moments as a writer come when I read over a passage and think, with a sinking heart, “Wow, that’s shallow.” I try to cut those passages. But I think the fear of the shallows may be a factor in the production of door-stoppers.

The presumptuous act of writing — demanding that other people pay attention to your thoughts — requires the confidence that you are telling them something worthwhile, but also carries with it the implicit fear (nay, terror) that you have been entirely banal. Perversely, I think that fear of the shallows often drives writers (fiction and non-fiction) to pile in more and more material in the hope that the additional episodes and details will show the depth of understanding and greatness of soul to which we all aspire. No doubt it works sometimes. But I won’t be reading a lot of those books.