David O. Stewart's Blog, page 3

July 4, 2017

Writing Great Characters Like Babe Ruth

But the novelist needs to tell us more, to lead us inside the character to new lands. That involves discerning what made that person tick, teasing out underappreciated qualities, and presenting those insights in a persuasive and natural-seeming narrative.

That challenge emerged early in writing The Babe Ruth Deception , my historical mystery about Ruth’s early years playing for the Yankees, years that also saw Prohibition crash onto the scene, organized crime explode in American streets, and gambling scandals beset baseball. I had to weave the Babe into those tumultuous times, respecting what we know while exploring truths under the surface.

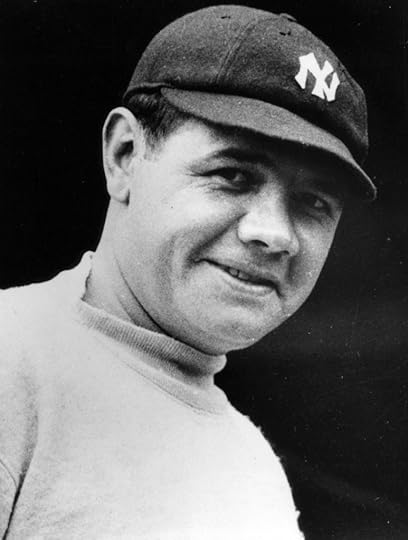

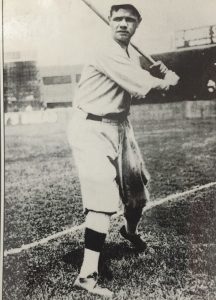

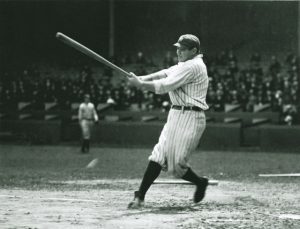

Babe Ruth as a new Yankee, 1920

I knew I had to include the Babe’s core, well-known qualities. He was barely educated, usually affable, always ready for fun, and a never-satiated consumer of food, liquor, and female companionship.

I also had to portray his extraordinary physical gifts. After all, no one else has been a star pitcher for four seasons, setting records that stood for decades, and then transformed himself into the best hitter of all time, reinventing baseball into a power game built around the home run.

I also had to confront a distortion in our historical memory. Most film clips of the Babe date from the end of his career, when high living had taken its toll and laid on extra pounds. Yet early in his playing days, the Babe was a physical marvel.

He was fast enough to steal home ten times. He had the power to set a new home run record in 1919, with 29 homers. And to smash that record the following year when he crushed 54 home runs (more than most entire teams that year). And then to break that record a year later with 59 home runs. Three record-setting seasons in a row. The man was no fluke. He did things that people didn’t imagine could be done.

With great talent comes a natural, unthinking arrogance. When asked why he played a musical composition so fast, the guitar virtuoso Andres Segovia answered, “Because I can.” Babe Ruth, behind that aw-shucks grin, knew he was better than other players. I needed to capture that, to dispel the assumption that he was just some big lunk who happened to have great hand-eye coordination.

The truth is, the Babe had a fierce drive to excel and didn’t let anything stand in his way. The closing scenes of The Babe Ruth Deception trace his astonishing performance in the 1921 World Series, when he almost gave up an arm in order to lead the Yankees in their first postseason classic ever.

He seized his career in both hands and made something great with it. When his first team, the Boston Red Sox, insisted that he continue pitching every four days, he made himself sufficiently obnoxious that the Sox sold his contract to the Yankees, who were willing to grant his wish to be an everyday outfielder.

On July 16, 1922, the Babe had the mortifying experience of losing a ball in the sun while playing left field in New York’s Polo Grounds. For the next 12 years, he refused to play any outfield position that looked into the afternoon sun. So he played right field in the Polo Grounds and Yankee Stadium and in Washington DC and Cleveland, but left field in all the other American League cities!

And when it came to marketing himself – what business types now call “building your brand” – no one could touch the Babe. For big paydays, he endorsed chocolate bars, two types of breakfast cereal (Wheaties and Quakers Puffed Wheat), cigarettes, cigars and chewing tobacco, soft drinks, gasoline, soap, bread, shaving cream, baseball mitts and balls, and even underwear (take that, Michael Jordan).

Babe Ruth working out (not his favorite activity) and having some fun!

So I had to depict a man with little education, rough manners, and decidedly low habits, who also was single-mindedly able to achieve unimagined success, while retaining a childish innocence and love for the game.

To capture such a complex figure, I read many descriptions of him and his exploits. I watched film clips and dug up old photos of him speaking and clowning around and hammering home runs. I had to insert what I learned into the story with the writer’s tools: creating revealing situations (fictional and real), portraying the Babe’s actions and reactions, and imagining his vocabulary of gestures and dialogue.

Did I get them right? I hope you’ll take a look at The Babe Ruth Deception and let me know how I did.

Understanding Babe Ruth

David O. Stewart

(David O. Stewart is the author of The Babe Ruth Deception, a historical mystery focused on the first two years the Babe played for the New York Yankees, 1920 and 1921.)

Portraying familiar historical figures is a central challenge of writing historical fiction, and also a great joy. The writer, of course, has to replicate any widely-known qualities about the character. Abraham Lincoln, for example, has to be tall. Ulysses Grant really should chain-smoke cigars.

But the novelist needs to tell us more, to lead us inside the character to new lands. That involves discerning what made that person tick, teasing out underappreciated qualities, and presenting those insights in a persuasive and natural-seeming narrative.

That challenge emerged early in writing The Babe Ruth Deception, my historical mystery about Ruth’s early years playing for the Yankees, years that also saw Prohibition crash onto the scene, organized crime explode in American streets, and gambling scandals beset baseball. I had to weave the Babe into those tumultuous times, respecting what we know while exploring truths under the surface.

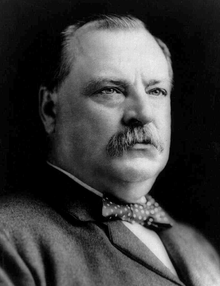

Young Babe Ruth: hale, hearty, and an extraordinary athlete

I knew I had to include the Babe’s core, well-known qualities. He was barely educated, usually affable, always ready for fun, and a never-satiated consumer of food, liquor, and female companionship.

I also had to portray his extraordinary physical gifts. After all, no one else has been a star pitcher for four seasons, setting records that stood for decades, and then transformed himself into the best hitter of all time, reinventing baseball into a power game built around the home run.

I also had to confront a distortion in our historical memory. Most film clips of the Babe date from the end of his career, when high living had taken its toll and laid on extra pounds. Yet early in his playing days, the Babe was a physical marvel.

He was fast enough to steal home ten times. He had the power to set a new home run record in 1919, with 29 homers. And to smash that record the following year when he crushed 54 home runs (more than most entire teams that year). And then to break that record a year later with 59 home runs. Three record-setting seasons in a row. The man was no fluke. He did things that people didn’t imagine could be done.

With great talent comes a natural, unthinking arrogance. When asked why he played a musical composition so fast, the guitar virtuoso Andres Segovia answered, “Because I can.” Babe Ruth, behind that aw-shucks grin, knew he was better than other players. I needed to capture that, to dispel the assumption that he was just some big lunk who happened to have great hand-eye coordination.

The truth is, the Babe had a fierce drive to excel and didn’t let anything stand in his way. The closing scenes of The Babe Ruth Deception trace his astonishing performance in the 1921 World Series, when he almost gave up an arm in order to lead the Yankees in their first postseason classic ever.

He seized his career in both hands and made something great with it. When his first team, the Boston Red Sox, insisted that he continue pitching every four days, he made himself sufficiently obnoxious that the Sox sold his contract to the Yankees, who were willing to grant his wish to be an everyday outfielder.

On July 16, 1922, the Babe had the mortifying experience of losing a ball in the sun while playing left field in New York’s Polo Grounds. For the next 12 years, he refused to play any outfield position that looked into the afternoon sun. So he played right field in the Polo Grounds and Yankee Stadium and in Washington DC and Cleveland, but left field in all the other American League cities!

And when it came to marketing himself – what business types now call “building your brand” – no one could touch the Babe. For big paydays, he endorsed chocolate bars, two types of breakfast cereal (Wheaties and Quakers Puffed Wheat), cigarettes, cigars and chewing tobacco, soft drinks, gasoline, soap, bread, shaving cream, baseball mitts and balls, and even underwear (take that, Michael Jordan).

k

Babe Ruth promotes Girl Scout cookies (in his mouth), while

admiring a scout in a way her father wouldn’t approve

So I had to depict a man with little education, rough manners, and decidedly low habits, who also was single-mindedly able to achieve unimagined success, while retaining a childish innocence and love for the game.

To capture such a complex figure, I read many descriptions of him and his exploits. I watched film clips and dug up old photos of him speaking and clowning around and hammering home runs. I had to insert what I learned into the story with the writer’s tools: creating revealing situations (fictional and real), portraying the Babe’s actions and reactions, and imagining his vocabulary of gestures and dialogue.

Did I get them right? I hope you’ll take a look at The Babe Ruth Deception and let me know how I did.

June 15, 2017

June 27: The Babe Ruth Deception launches in paperback, preorder now!

With the Yankees perched in first place in the AL East, it’s a great time to launch the paperback of The Babe Ruth Deception, my mystery about the Babe’s first years with the Yanks. Consider pre-ordering your copy soonest!

Set in 1920 and 1921, The Babe Ruth Deception plunges Jamie Fraser and Speed Cook — the heroes of my mystery series — into the tumultuous time when the Babe was reinventing baseball, when gangsters corrupted America’s Pastime, and when Prohibition changed everything. The story careens from pennant races to terrorism, from the movies to forbidden romance to fixing the 1919 World Series, while dark figures sink their hooks deep into the Babe. Only Fraser and Cook can help. . . . (For full synopsis, click here.)

Next month I’ll be talking about the book at these events and would love to see you there:

Sunday, July 9, at 2 p.m., at the Bethesda, MD Writers Center

Saturday, July 8, at 9 a.m., with the Bob Davids Chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research in Columbia, MD.

Reviewers of the novel have been generous:

“David O. Stewart is rapidly becoming one of our best new writers of historical mysteries . . . [with] his Deception series of gripping mysteries.” “[Fraser and Cook] have plenty of fraught challenges, but none more engaging and human than the swaggering, generous, profligate Great Bambino.”

— Washington Times, September 22, 2016

“A terrific read. . . . This one is a baseball fan’s dream.”

— Mystery Scene Magazine, Fall 2016

“The Babe Ruth Deception is a solid story of friendship, love, and baseball set at a turning point in American history. It offers a glimpse of some of the worst of human nature — scandal, greed, racial tension — yet leaves the reader rooting for the home team.”

— Washington Independent Review of Books, October 9, 2016

“This is so much more than a baseball book. . . . I loved it!”

— Tim Kurkjian, ESPN Baseball Contributor and Author

The Babe doing a star turn in 1920 movie “Headin’ Home,” which occupies a central place in the novel!

April 6, 2017

Babe Ruth Built the Best Brand Ever

Look at that grin! The Babe. Who else could it be?

Our digitized world is obsessed with branding. The road to success, we’re told, is to create a public image of a consistent experience/product/person that people will want to acquire or be exposed to.

That’s why the trade association for accountants published “Five Tips to Branding Yourself” (how, in fact, do accountants brand themselves?). It’s why Success Magazine advised “How to: Brand Yourself.” And it’s why Semantic Scholar magazine explored the power of branding (“Researchers themselves are brands”).

Even writers are supposed to brand themselves (painful!) with online posts like this one, social media chirpiness, and identifiable literary products like my historical mystery series, each with “Deception” in the title. [Which means I should mention that the paperback The Babe Ruth Deception will release on June 27!]

So let me put in a vote for the best brand ever: BABE RUTH.

The Power of the Name

What’s the evidence? I’ll stake my case on the name “Babe Ruth” and how we use it. When we want to say that someone is dominant in a field, is the absolute best, what’s the metaphor that we reach for? Often, it’s the Babe. Among the examples I’ve noticed in just the last few months:

When Donald Trump’s spin artist wanted to tout her candidate’s performance in a debate, she called him “The Babe Ruth of debating.“

To explain why Yale University named a residential college for Grace Hopper, a largely unknown navy admiral/computer whiz, the New Haven newspaper called her .”

When a federal trial witness wanted to describe a sports gambler and investment guru, he called him “The Babe Ruth of Risk.”

How to describe Bill Clinton on the campaign trail? He’s the “Babe Ruth of Presidential Campaigns,” according to the Observer.

Even Marty Aronoff turns out to be the “Babe Ruth of Television Statisticians,” or so USA Today told us.

This just scratches the surface. Willie Sutton as the “Babe Ruth of Bank Robbers” and Enrico Caruso as the “Babe Ruth of opera singers”? Of course, according to Time Magazine and the New York Times, respectively.

Atlantic Magazine said that Wilt Chamberlain was “the Babe Ruth of Basketball“? But Fox News thinks Kobe Bryant was “the Babe Ruth of the NBA“? Who knew there was a “Babe Ruth of bridge“? A “Babe Ruth of Relationships“?

Or that Bible teachings of the Old Testament are “The Babe Ruth of Kindness?

I couldn’t make this one up.

So how did the Babe do it? He was a lightly-educated kid from the wrong side of Baltimore’s tracks with a family so dysunctional that he mostly was raised in St. Mary’s Industrial School. Yet he built the Best Brand Ever.

For a full answer, we’ll have to wait until this time next year, when Jane Leavy’s book on the Babe comes out — Hey Big Fella: Babe Ruth and the Advent of Celebrity. Like Jane’s other books, it’ll be compelling and fascinating. Until then, here’s a quick list of reasons that pop into my mind:

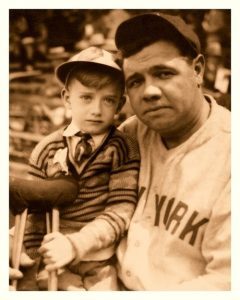

Go ahead, try not to puddle up over this one!

Do something that lots of people do and love (baseball!), and do it better than anyone else ever has.

Have FUN while you’re doing it.

At the batting cage with kids

While you’re at it, fundamentally change how that thing is done — say, by hitting more home runs than anyone ever thought was possible.

Slap a charming grin on an ugly-handsome, unforgettable face.

Have an easy-to-remember, two-syllable name that sounds as friendly as your grin looks.

Make it clear that you like a good time as much as — hell, more than — most people do.

Babe holding court after a game

Love kids and get yourself photographed with them all the time.

Then go ahead and endorse every product that will pay you to do so. Don’t be shy about it.

Among the items the Babe touted for America were:

Babe Ruth Underwear.

“Ruth’s Home Run” chocolate bar (the Baby Ruth bar was a total ripoff of the Babe by the Curtis Candy Company, but I digress).

Wheaties!

Quakers Puffed Wheat and Puffed Rice.

Did he always wear his uniform to breakfast?

Old Gold Cigarettes

Pinch Hit Tobacco

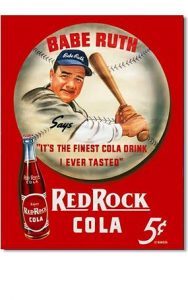

Red Rock Cola

Esso Oil

Murphy-Rich Soap

Mrs. Sherlock’s Bread

Sinclair Oil

Raleigh Cigarettes

White Owl Cigars.

A.J. Reach Co. baseball mitts and baseballs

Barbasol shaving cream.

Girl Scout cookies!

Hey Babe, look at the camera, not the Girl Scout!

March 1, 2017

Up Next: G. Washington, America’s Master Politician

I’ve just signed with a Penguin imprint, New American Library, to write a book about The Big Guy — GWash himself, the Master of Mount Vernon, the man-myth who was indisputably the key figure in the founding of the United States and without whom, well, things would have gone very different and a whole lot worse for Americans. First in war, first in peace. . . . and the only human being for whom a global capital city is named!

Is this exciting? Absolutely. After writing three books in the Founding Era — The Summer of 1787, Madison’s Gift, American Emperor — I feel like I’m about to plunge into the back room where the priests put on their robes while wrestling with their doubts, that I’m approaching the beating heart of the whole enterprise. (Also, entering territory where my control over metaphors magically degrades.)

Is this intimidating? That, too. See, people have written books about Washington before. Maybe, I don’t know, a bajillion have so far. And some of those books have been really really good.

So what am I going to do different?

The Political Master and The Real Man

Washington was the third son of a second-tier Virginia planter with family connections that were relatively undistinguished for Virginia of the era. He had little formal education. With peers who read Latin and Greek and spoke French, who inhaled philosophical treatises and argued passionately about intellectual matters, he mostly held his tongue. He was a man of action in a generation of American leaders who thought great thoughts. Washington mostly kept his to himself.

Filled with ambition, Washington was a hard-driving slave master who didn’t shy from the need for violence to compel enslaved people to work. He could be grasping in commercial dealings. His greatest business venture — building a canal/water link between the Potomac and Ohio Rivers that would open up the American West — never succeeded, dashing the fortunes of many before it was abandoned a quarter-century after his death.

Yet when it came to public matters, he was as sure-footed a political operative as America has seen, or will ever see. As a military commander, his political skills in dealing with Congress were as important as his strategy for outlasting the British. Time and again as president, he faced complex, delicate political decisions and always weaved his way through competing concerns to reach an outcome that was both wise and effective. Take some obvious symptoms of this mastery: he won the four most critical political contests of his career, and the nation’s birth. No, that’s not all. He won them unanimously.

That’s right. No one voted against him.

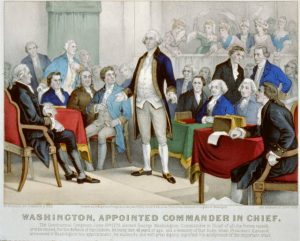

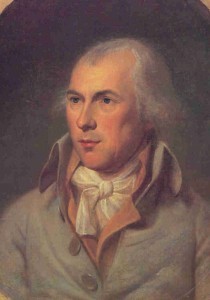

Currier & Ives print of Washington’s selection as commander of the Continental Army, 1775

That includes the 1775 vote by the Continental Congress to name him commander-in-chief of the Continental Army that would lead America’s drive for independence.

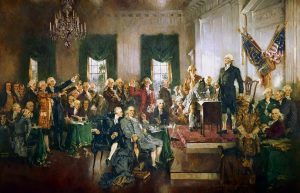

That includes his elevation as president of the 1787 Constitutional Convention that created the world’s longest-lived constitutional democracy.

Washington presiding over the signing of the Constitution, 1787

And, of course, that includes his two elections as president of the new nation, in 1789 and 1792.

So maybe you’re shrugging inside your mind and thinking, okay, but he was really tall and it was the olden days when no one faced any real political opposition. Not such a big deal for him to win like that, right?

Wrong. Those guys played for keeps, without pads or helmets.

Thomas Jefferson was as tall as Washington and way more articulate, but he didn’t have any cakewalks into the White House. The first time he ran for president in 1796? Got beat by John Adams, who was really short and had an evil temper. The second time, in 1800? He managed to nose out Adams but then was tied by his own running mate, Aaron Burr. How embarrassing was that? Jefferson finally gasped over the finish line after thirty-six anxious ballots in the House of Representatives. (All presidential election votes are collected here.)

Go down the list of early presidents. Adams? A one-term president, defeated in his bid for re-election. Madison? Lost his campaign for a seat in the U.S.Senate in 1789, and faced two contested elections for president; one was pretty tight. Monroe? Lost his race for the House of Representatives in 1789 and barely won nomination for president in 1816.

Easy? Only for Washington.

So where did the man’s political mastery come from? It sure didn’t come from books or higher education. I want to look hard at some often-neglected times in Washington’s early life. When he served in the British Army in the French and Indian War, it didn’t go very well. He squabbled with his superiors and left the service in frustration in 1758. After leaving the army, he served for sixteen years as a legislator in the Virginia House of Burgesses, and five years as a justice of the Fairfax County Court.

Then, when the independence crisis ripened in 1774 and 1775, Washington arrives as WASHINGTON, the man of the moment who commanded the respect of every other delegate in the room at the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, and of every soldier in the army he took command of. Something happened between 1758 and 1774. He transformed himself. How did he do that? How did he remake himself?

I don’t have snappy answers to all these questions today, but I have some ideas, and I hope to have compelling answers by the time the book comes out . . . in a few years.

It won’t be easy. Washington could be aloof. It was a technique for commanding respect while avoiding conversations where he might not shine. As a mature leader, he was always careful about what he said. But underneath layers of self-control and discipline was a man of ferocious intensity whose force of will impressed everyone who met him. To protect the man underneath the shell from our prying eyes, he had his wife, Martha, burn all of their intimate correspondence.

Even after Martha’s conflagration, there’s a crazy volume of Washington-related material to master. At least sixty-eight volumes of his papers are already in print.

But it’s more than just the volume of material. By now George Washington has become the marble man, the one whose monument in the city named for him is a massive phallic symbol, not an even slightly humanizing statute. I hope to chip away at that marble exterior and find the person underneath, one with fears and uncertainties and drive and even a sense of humor.

Wish me luck, and stay tuned.

February 10, 2017

Africa Days and Nights

Coming home from 17 days in East Africa last month, jazzed by how fascinating our visit had been and conscious of how little I know about Africa, I scooped up Ryszard Kapuscinski’s The Shadow of the Sun while wandering around the Arusha (Tanzania) Airport. What a stroke of luck!

The amazing animals roaming in the national parks of Kenya and Tanzania drew us to Africa, but then Africa exerted its own pull.

We went to Africa mostly to see the game preserves, which were everything we hoped for, from the hippo blocking our way to breakfast to the endless zebra and wildebeest to the multiple prides of lions and the solitary leopards, the majestic elephants and the poignantly voiceless giraffes. But I found all elements of East Africa to be fascinating, especially the people and their lives and the surprisingly mild climate (surprising to me, anyway), the great distances and breathtaking vistas.

So I was lucky to stumble upon the Kapuscinski book. He was a Polish journalist who died about ten years ago. His specialty was Third World countries, with a focus on Africa, which he first visited in 1957. Voted “journalist of the century” in Poland (whoever makes that decision), he traveled to fascinating and terrible places on the African continent. I loved reading about them — some sweltering in humidity, some blistering with desert heat, many filled with hungry, desperate people. He captured moments that sum up a place and a society, such as this episode when he took a bus in Ghana.

“We climb into the bus and sit down. At this point there is a risk of culture clash, of collision and conflict. It will undoubtedly occur if the passenger is a foreigner who doesn’t know Africa. Someone like that will start looking around, squirming, inquiring, ‘When will the bus leave?’

“‘What do you mean, when?’ the astonished driver will reply. ‘It will leave when we find enough people to fill it up.'”

It leaves two hours later, full to bursting with passengers.

Ryzsard Kapuscinski, Poland’s journalist of the century.

But Kapucscinski did more than just describe. He reflected on what he saw and tried to understand those things. He speculates that below the Sahara Desert, Africa’s development was hamstrung by the use of a single form of land transportation: the human leg:

For thousands and thousands of years, Africa walked. People here did not have a concept of the wheel, and were unable to adopt it. They walked, they wandered, and whatever had to be transported they carried — on their backs, on their shoulders, and, most often, on their heads.

But why no concept of the wheel? He traces it to something else:

Neither the camel nor the horse was able to adapt to regions south of the Sahara — they perished, decimated by the encephalitis borne by the tsetse fly, as well as by other fatal diseases of the tropics.

So, he wondered also, how did this limitation interact with “the immensity of African space (more than thirty million square kilometers!) and the defenseless, barefoot, wretched man who inhabits it.”

Often one had to walk for hundreds, thousands of miles, to encounter other people. . . For the most part information, knowledge, technological innovation, goods, commodities, and the experiences of others did not penetrate here, could not find a way in.

The African was a man on the move. Even if he led a sedentary life in a village, he was also on the move, for periodically the entire village would set off: either the water had run out, or the soil had ceased to bear crops, or an epidemic had broken out, and off they would go. . .

The striking physical characteristic of [African] civilization is its temporariness, its provisional character. . . A hut put up only yesterday has already vanished. A field still cultivated three months ago is today lying fallow . . .

The continuity that lives and breathes here, and that creates the thread of social fabric, is the continuity of family tradition and ritual. . . . Rather than a material or territorial community, it is a spiritual community that binds the African to those closest to him.

This rings true to me. For example, our Kenyan and Tanzanian guides — people thoroughly entrenched in the technology and information overload of the 21st century — retained powerful ties to their tribes, their clans, their family villages.

Also, Kapuscinski wonders, has this “compulsory mobility” of Africans “resulted in Africa’s interior having no old cities, at least none comparable in age to those that still exist in Europe, the Middle East or Asia”?

Are some or all of Kapuscinski’s extravagant generalizations subject to cavil and qualification by anthropologists and historians? I assume so. But they are thoughtful and provocative, and accord with some of my very shallow impressions of the places we saw.

Kapuscinski was gifted not only at speculating about large forces in the world. He also was a keen observer of the small parts of life. He had particular empathy for Africa’s urban poor, drawn to the cities in the hopes of finding some food, a life even slightly better than the struggle for survival in their drought-ravaged villages. His 1967 description of the destitute in Lagos, Nigeria, stays with me:

My alley, the adjacent streets, and the entire neighborhood are full of idle people. They wake in the morning and search for some water with which to wash their faces. Then, those with a bit of money buy themselves breakfast: a glass of tea and a stale roll. But many people don’t eat anything. Before noon still, the heat is difficult to bear — one must look for a shady spot. The shade moves hourly with the sun, and the man moves with the shade — following the shade, crawling after it to hide in its dark, cool interior, is each day his only real occupation. Hunger. One badly wants to eat, but there is nothing to be had. Making matters worse, the smell of roasting meal wafts from a nearby bar. Why don’t these people storm the bar?

. . .

It is rare for someone to settle for long in my alleyway. The people who pass through are the city’s eternal nomads, wanderers along the chaotic and dusty labyrinth of its streets. They move away quickly and vanish without a trace, because they never really had anything. They go, either tempted by the mirage of employment, or frightened by an epidemic that has suddenly broken out nearby, or evicted by the owners of the clay huts and verandas, whom they were unable to pay for the space they occupied. Everything in their life is temporary, fluid, and frail. It exists and it doesn’t exist. Even if it does exist — then for how long? This eternal uncertainty causes my neighbors to live in a perpetual state of alert, of unabating fear.

Fifty years later — based on the many young and older people we saw idling on streets and in markets at all times of the day, based on the our guides’ report that Kenya has a forty percent unemployment rate — not a great deal has changed.

I’m not sure that Kapuscinski’s work would have resonated so powerfully with me if I had not just been in Africa, but I commend it without reservation. Have you never understood the whole Hutu and Tutsi thing in Rwanda? Kapuscinski can explain that to you. How about the decades-long civil wars on the continent — in Uganda and Ethiopia and Nigeria and Liberia: why do we know so little about them? Kapuscinski has ideas about that, too. It’s a great book.

December 15, 2016

225th Birthday of America’s Bill of Rights!

The semi-dashing James Madison in 1794, five years after drafting America’s Bill of Rights.

I’m delighted to be among the first to proclaim the 225th anniversary of the ratification of America’s Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the Constitution. Those amendments protect individual liberties that Americans hold most dear, and became central to our national character after the Fourteenth Amendment (adopted in 1868) applied them against state governments as well as the federal government.

I thought about writing a book about the enactment of the Bill of Rights as a natural sequel to my first book, The Summer of 1787: The Men Who Invented the Constitution. Ultimately, though, I concluded that the story lacked the drama and oomph I was looking for. In truth, America backed into the Bill of Rights, which was adopted without much enthusiasm. I did get to write about the episode in Madison’s Gift, but as part of the much larger story of James Madison’s remarkable contributions to the nation.

The surprising truth is that the delegates at the Philadelphia Convention of 1787 didn’t spend much time thinking about protecting individual liberties. Their concern was with creating an effective new government.

In the last week of the convention, George Mason of Virginia and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts proposed a Bill of Rights; several state constitutions had one. The other delegates, however, swiftly defeated the effort. They offered the counter-arguments that it wasn’t necessary (how could the federal government threaten personal rights?) and that it would be dangerous to list some protected rights because they might inadvertently omit others that should have been listed. Mostly, though, they thought Mason and Gerry were trying to sidetrack completion of the Constitution, which both men soon refused to sign.

Once the Constitution was released to the public, the most effective criticism of it turned out to be the absence of a Bill of Rights. The pro-Constitution forces, led by Madison and Alexander Hamilton, won ratification by the states over the opposition, but Madison became persuaded that a Bill of Rights was necessary to quiet public doubts about the new government. Indeed, he made it a central campaign promise when he ran for Congress in early 1789 against James Monroe.

Accordingly, Madison arrived in Congress in New York City on a mission to win approval of a Bill of Rights. Though many congressmen and senators thought a Bill of Rights wasn’t very important and resented spending time on it, Madison insisted, arguing that it would not be “altogether useless” — a surprisingly modest claim.

Federal Hall in New York City, where Madison proposed the Bill of Rights and Congress approved them in 1789.

Madison proposed a long list of rights to be protected. His list was consolidated by the House, then pared down much further during the then-secret deliberations of the Senate. Consequently, we have no good explanation for many of the wording choices in the final text of the amendments. That has helped fuel considerable litigation — as with, for example, the clumsily worded Second Amendment and its right to bear arms.

One of the dropped Madison amendments would have ensured freedom of speech and religion against state intrusions, a protection that would have to wait for the Civil War and the Fourteenth Amendment.

The final ratification came more than two years after Congress adopted the amendments, on December 15, 1791, from — fittingly enough — the state of Virginia.

Congress had sent twelve amendments to the states in 1789, but only ten were ratified then and became known as the Bill of Rights. Of the two that were not adopted in 1791, one was adopted two centuries later as the Twenty-Seventh Amendment, and decrees that congressional pay raises cannot take effect until after a new Congress is elected. The twelfth proposed to limit the size of congressional districts to 30,000 citizens; it was not adopted and swiftly became moot as the nation grew.

Madison’s prediction about the importance of the Bill of Rights proved prescient. He acknowledged that in times of crisis — war and civil strife — governments will violate individual rights and no “parchment barriers” are likely to stop them. But by enshrining personal rights in the Constitution, he argued, those rights would become entrenched in the national character and ultimately would be cherished and protected in many situations.

Happy Birthday!

December 8, 2016

Babe Ruth in Pictures

Though my Babe Ruth book’s a novel — as in FICTION — one of the fun consequences of writing about the Babe has come when people share with me their Babe memorabilia. Because the Babe was way more than just a great ballplayer. He was and remains a huge cultural figure. I offer a couple of exhibits.

At the semi-famous Dan Moldea Writers’ Dinner this week night (we writers have to dine together because few others want to eat with us), none other than Mr. Moldea, who you know as the relentless pursuer of the Jimmy Hoffa killer and other mysterious evildoers, shared with me some souvenir baseball cards he acquired . . . sometime or other. They’re not from Ruth’s era, but they have some great photos of the Babe.

Start with the Babe’s marriage to 16-year-old Helen Woodford, his waitress at a Boston restaurant when he was a rookie with the Boston Red Sox in 1914.

Babe and first wife Helen Woodford in the early days of their marriage.

Is that a charming picture, or what? It’s so easy to forget the young Babe, the one who captured the heart of the nation (and is featured in my novel).

Then Dan’s treasure trove yields up an image of Babe from 1919, the first year he played the outfield fulltime for the Boston Red Sox and led the league in homers with 29, hit .322, and drove in 113 runs.

Take a gander at how young the 23-year-old ex-pitcher looks!

Oh, yeah, he also kept pitching that season when the Bostons needed him to. In 1919, he pitched 133 inning, racking up a 9-5 record with an earned run average of 2.97.

Be honest: you might not even have recognized him in that image, right? He looks so young and slender, so full of promise. Of course, the camera doesn’t reveal how much he made himself a pain in the neck to the Red Sox so they’d send him to another team, the heretofore no-account New York Yankees, until then a perennial also-ran in the American League.

Babe changed the Yankees forever, leading them into two World Series in 1921 (a centerpiece of my novel) and 1922 (after the novel ends). Babe performed heroically in that first series as a Yankee. In the second one, though, the Babe came up small, hitting an anemic .118 with no home runs.

He spent the next winter at the farm he and Helen owned in Massachusetts, using farm chores to get into great physical condition. That process is commemorated in the final photo from the Moldea trove, a dinner in New York honoring the Babe and his putative workout partner, a model of a cow.

He spent the next winter at the farm he and Helen owned in Massachusetts, using farm chores to get into great physical condition. That process is commemorated in the final photo from the Moldea trove, a dinner in New York honoring the Babe and his putative workout partner, a model of a cow.

How did the bovine workouts turn out? Babe returned to form in the 1923 season, batting an amazing .393, blasting 41 homers and driving in 130 runs.

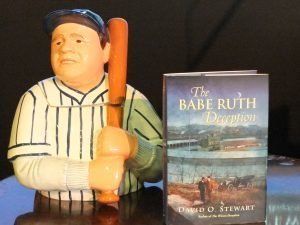

My final bit of Babe-orabilia came from baseball savant Paul Dickson, who found this cookie jar . . . somewhere or other. Outstanding, eh?

Babe Ruth cookie jar — suitable for holding Baby Ruth bars, too!

November 9, 2016

The Constitutional Elector System: Defeating Democracy for Two Centuries

It seems to have happened again. This makes four.

Hillary Clinton

The American people just voted for president. The candidate who won the largest number of votes — Hillary Clinton, this year — will not become president. As of now, she is more than 200,000 votes ahead of her leading opponent, Donald Trump. But through the weird alchemy of the elector system, Trump will become president.

It happened in 1876, when Rutherford Hayes “won” the election against Samuel Tilden. And in 1888, when Benjamin Harrison “defeated” Grover Cleveland. And in 2000, when George W. Bush “triumphed” over Al Gore.

Why do we put up with this?

Donald Trump

The presidential elector system grew out of a stalemate at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. The delegates couldn’t figure out how to choose the president. Many thought it outrageous to suggest, as James Madison and Alexander Hamilton did, that the president should be chosen by popular vote. As George Mason of Virginia blustered, the people are ill-informed and not to be trusted! You might as well, he added, ask a blind man to choose colors.

So they created the elector system. The voters were to choose wise men (only men, of course) to be electors. Each state would have as many electors as the combined number of senators and representatives it had, and each state could determine how it would choose electors and how the electors would do their business. Because the electors would be wise, they would choose the most qualified person.

The system was ill-considered, unprecedented, and broke down as soon as George Washington retired from public life. Political parties formed, and parties were not going to tolerate having a bunch of self-important people deciding who would be the best candidate. Only the party candidates would be considered. Many states had their state legislatures choose the electors; only after the Civil War did every state allow voters to choose the electors.

At its core, though, the system has a bias. In the patois of the president-elect, it’s rigged. As I explained in an appendix to my first book, The Summer of 1787, by giving each state two electors based on their senators — rather than allocating electors solely on the basis of population — the system gives greater power to small states. A candidate who wins a bunch of small states can gather up a disproportionate total of electors and win the contest while still having fewer overall votes than an opponent.

No one in 1787 intended that result. In 1787, they didn’t expect popular votes even to be tallied. The system has just worked out that way.

Samuel Tilden

Grover Cleveland

Al Gore

As Samuel Tilden, Grover Cleveland, Al Gore, and now Hillary Clinton have experienced.

It’s a ridiculous barnacle on our democracy, the unintended result of decisions made more than two hundred years ago. We have the power to change it by amending the Constitution. It has been proposed many times. That amendment is long overdue.

October 14, 2016

Winning by Losing: Babe Ruth at the 1921 World Series

Babe Ruth led the New York Yankees into the 1921 Series against the New York Giants of John McGraw and Frankie Frisch.

When Babe Ruth led the New York Yankees into their first World Series ever in 1921 — 95 years ago — he had just finished what may have been the best season a hitter has ever had: 59 home runs, 161 RBIs, a .378 batting average. He scored 177 runs. Opposing teams hated to pitch to him; he impatiently endured 145 bases on balls.

Baseball fans eagerly anticipated the Yankees’ October showdown with their crosstown rivals, the New York Giants. Though Babe had played in three World Series for the Boston Red Sox, he had been a star pitcher then. Now he had made himself the most feared hitter in the sport. What havoc might this awesome “Sultan of Slug” wreak on the poor Giants?

The reality was both much less than fans had hoped, and much, much more.

Take what they give you

That’s the truism that hitters have to learn, and the 26-year-old Babe knew it well. In the early games of the Series, the Giants’ pitchers wanted no part of him. They walked him four times in the first two games. And the Babe was eager to do something great. He struck out twice. Still, he drove in a run with a single in the first game and scored a run in the second, stealing two bases in the process. Fabled sportswriter Heywood Broun drew an indelible portrait of the rampaging Ruth on the basebaths:

“It is startling to see so huge a man suddenly abandon his fixed post at top speed. If some morning the Woolworth building should lean over and pat a passer-by on the back without preliminary warning, somewhat the same effect might be created as that which attends the sight of Ruth’s entire body in motion all at once.”

The Yanks took the first two games by 3-0 scores, jumping into the lead in the best-of-nine series (1921 was the last time baseball used the best-of-nine format).

Ruth drove in two more runs in Game 3 with another single and was walked again, but the Giants roared back to take the game in a laugher, 13-5. When Ruth was pulled for a pinch runner in the eighth inning, some fans booed. They didn’t know the truth. Babe’s aggressive baserunning had brought on a painful injury.

As big as an elephant’s thigh

Sliding into third base in Game 2, Babe had torn up an elbow on the pebbly, uneven basepath. He aggravated the injury performing the exact same act in Game 3. When the Yanks announced that he wouldn’t play in Game 4, panic struck among their fans.

“The Yankees have lost not only his great hitting,” the New York Times wrote, “but also the smartness and cunning that this ball player brings to a team.” The article pointed out that Ruth “conceived and directed most of the daring base running to the credit of the Yankees, and his value as a strategist has excelled even his ability to punch the ball to distant regions.”

Not just a power hitter, eh?

Babe Ruth taking a mighty swing in 1921 season — look at the size of that bat!

But in Game 4, Babe confounded the experts and the doctors. Playing despite his injury, he smacked a home run and single in a losing cause. Now the series was even.

Game 5 was the watershed. Despite the elbow injury and a knee that was going lame, Babe took his post in left field and his third spot in the batting order. His elbow was on fire. The knee was shaky. He wasn’t the real Babe Ruth. He struck out three times, yet led his team to a win with a startling bunt single in the fourth inning and coming around to score winning run by the end of the inning. “Babe Ruth knocks the Giants over with a feather,” Heywood Broun announced, vividly describing the big man’s bunt:

“Babe’s bat was vibrating up behind his shoulder and he was staring intently at the wooden bleachers in right [field]. It was a gorgeous piece of character acting for as the ball came up to the plate, Babe suddenly checked his swing and thrust his bat straight out across the plate. The ball dropped five feet away from the plate, lazily rolled over twice and stopped. And like a bigger ball with a bad dent in it, Ruth rolled toward first, going lickety split and limpety-limpety.”

To equal the distance of Babe’s longest home run, Broun added, Babe would have to hit that bunt 105 and one-half times, but “that little tap served just as well.”

It was the Babe’s final highlight in the Series. The Yankees, alarmed by the spreading infection in his arm and by his gimpy knee, disqualified him from further play. Yankee Manager Miller Huggins said after Game 5, “How he had been able to do what he had done during the afternoon made me look at him in amazement. It was an exhibition of gameness that will go down through baseball history.” Another great sportswriter, Grantland Rice, wrote that Babe’s arm was so swollen that it “looked like an elephant’s thigh.”

With Ruth sidelined, the Giants took the series, five games to three. Babe took the field one more time, pinch hitting in the final inning of the final game. He grounded out weakly.

Though the series had been grueling and disappointing, the Babe had only burnished his emerging legend. “Ruth had the greatest individual following in baseball before the series opened,” the New York Times wrote, “and he has passed out of the series a bigger figure in baseball than he was at the start.”