Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 226

August 18, 2014

Preview of StAR's September/October Issue

The William Byrd Festival is in progress in Portland, Oregon with its concluding events coming up this weekend. The reason I lead off with this notice is that I have an article about Byrd and other recusant composers coming out in the September/October issue of the St. Austin Review (plus a book review).

The William Byrd Festival is in progress in Portland, Oregon with its concluding events coming up this weekend. The reason I lead off with this notice is that I have an article about Byrd and other recusant composers coming out in the September/October issue of the St. Austin Review (plus a book review).According to Joseph Pearce, who ought to know:

The theme of the next issue of the St. Austin Review is “Recusants and Martyrs: English Resistance to the Tudor Terror”.

Highlights:

-Shaun Blanchard views St. Thomas More as the Ideal Christian-Joseph Pearce connects Shakespeare and St. Thomas More-Mark Amorose waxes poetical about Recusants-Anne Barbeau Gardiner discovers Secret Hiding Places: Recusant Houses and Priest-Holes Made by a SaintStephanie A. Mann reads between the lines in her survey of Tudor Church Music and Revisionist History-T. Renee Kozinski looks iconically at St. Edmund Campion and the Tyburn Tree-John Beaumont tells the tale of A Remarkable Convert Priest, Resisting the Tudor Terror-Stephen Brady condemns The Murder of Merrie England-Brendan King admires The Picture that Painted a Poem, explaining How an Italian Masterpiece Inspired an English Saint-Trevor Lipscombe elegizes Our Lady’s Dowry-Susan Treacy muses on William Byrd’s Gradualia-M. J. Needham praises the Art of Katie Schmid in the full colour art feature-Kevin O’Brien tackles Modern Persecution and the Catholic Church-James Bemis checks off Schindler’s List in his ongoing survey of the Vatican’s List of “great films”-Fr. Benedict Kiely contemplates the meaning of the priesthood-Donald DeMarco spies A Ray of Hope for the Family in Quebec-Michael Lichens remembers Stratford Caldecott-Carol Anne Jones reviews Was Shakespeare Catholic? by Peter MilwardStephanie A. Mann reviews Catholics of the Anglican Patrimony by Aidan Nicholls-Carol Anne Jones reviews Anne Line: Shakespeare’s Tragic Muse by Martin Dodwell-Mark Newcomb reviews The One Thomas More by Travis Curtright

I'll post the cover as soon as it is available!

Published on August 18, 2014 22:30

August 17, 2014

Mosul Today and England Yesterday

Father Christopher Colven, rector of St. James, Spanish Place, offers these reflections on the current state of affairs in Mosul, Iraq and in the England during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries:

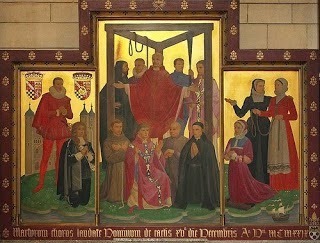

The Christian communities of Iraq are among the oldest that have existed and it is particularly painful to see the witness of 2,000 years persecuted and dispersed. As our bishops reminded us last weekend, the Eucharist will have been celebrated in Mosul for the best part of two millennia – but now no more – no altar, no priest, no Christian people. We must continue to pray and do whatever we can for our brothers and sisters as they seek a new security, but it does us well to remember that what we take so easily for granted is a great privilege denied to many in our own times, and that there were many sad years here in England when the state forbade the celebration of the Mass. The reredos above the Martyrs altar in Saint Michael’s Chapel (this is the original which has been reproduced in many other Catholic churches) depicts a few of those who were willing to make the ultimate sacrifice of their own lives for the sake of the Mass. Several of those depicted were ordinary working people - John Roche, the Thames lighterman, together with three housewives Margaret Clitheroe, Anne Line and Margaret Ward – all of them martyred for trying to ensure that, despite every attempt to frustrate them, the Holy Sacrifice would continue to be offered on English soil.

Father Colven goes on to highlight our proper dispositions for receiving Holy Communion at Mass, citing Pope St. Pius X, whose memorial we will celebrate on Thursday this week:

The new Bishop of East Anglia has recently made the point that we are in danger of losing our grasp on the Eucharistic Mystery: because the Mass is now so easily available (a minimum of three Masses each weekday here at Spanish Place alone) and Holy Communion is received as a matter of course (often without any real time of preparation) we can become blasé in approaching the Bread of Life. It was Saint Pius X at the beginning of the last century who encouraged all Catholics to make their Holy Communion as regularly as possible – and that is clearly a very good thing to do – but Saint Paul issues a stern warning in his dealings with the Corinthian Christians about any failure to “discern the Lord’s Body” when doing so: we must never treat holy things in a casual way. “Everyone is to recollect themselves before eating this bread and drinking this cup because a person who eats and drinks without recognising the Body is eating and drinking his own condemnation” (1 Corinthians 11:28).

Then he brings us back to the memory of the English Catholic martyrs who were willing to suffer so much for the sake of the Holy Eucharist, the source and summit of our Catholic faith:

The current suffering of so many of those who are with us “in Christ", as well as the particular history of the Catholic Church in these islands, should give pause for thought and the opportunity to think out afresh what the celebration of the Eucharist means to us. Tyburn Tree, where so many of countrymen and women accepted terrible deaths is only a few hundred yards from Saint James’s doors – “lest we forget”. Mother Teresa of Calcutta caused a notice to be put up in the sacristy of each of her convents worldwide: it was an admonition to the celebrant – but it applies as well to the faithful gathered around any altar: “O priest of God, offer this Mass as if it were your first … and as if it were your last”.

Image credit.

Published on August 17, 2014 22:30

August 16, 2014

Mr. Darcy Proposes Again

My husband and I went to see Woody Allen's new movie, Magic in the Moonlight with Colin Firth as a melancholy magician who sets out to prove that Emma Stone, the supposed psychic medium is a fraud. Of course, he ends up falling in love with her--it's a rather lightweight Woody Allen movie and its supposed discussion of whether there is anything beyond this life on earth is really beside the point of the movie. It's set in 1928 in the south of France (Coe d'Azur and Provence), the costumes are excellent and the music is fun.

Colin Firth, however, must have experienced a moment of deja vu as he played his character, Stanley, because as he proposed to Sophie he seems to be channeling (just to use one of Sophie's terms) another character. Stanley's proposal of marriage is diffident and proud, just as Mr. Darcy's was to Elizabeth in Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice :

"In vain I have struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you."

Elizabeth's astonishment was beyond expression. She stared, coloured, doubted, and was silent. This he considered sufficient encouragement; and the avowal of all that he felt, and had long felt for her, immediately followed. He spoke well; but there were feelings besides those of the heart to be detailed; and he was not more eloquent on the subject of tenderness than of pride. His sense of her inferiority-- of its being a degradation-- of the family obstacles which had always opposed to inclination, were dwelt on with a warmth which seemed due to the consequence he was wounding, but was very unlikely to recommend his suit.

In spite of her deeply-rooted dislike, she could not be insensible to the compliment of such a man's affection, and though her intentions did not vary for an instant, she was at first sorry for the pain he was to receive; till, roused to resentment by his subsequent language, she lost all compassion in anger. She tried, however, to compose herself to answer him with patience, when he should have done. He concluded with representing to her the strength of that attachment which, in spite of all his endeavours, he had found impossible to conquer; and with expressing his hope that it would now be rewarded by her acceptance of his hand. As he said this, she could easily see that he had no doubt of a favourable answer. He spoke of apprehension and anxiety, but his countenance expressed real security. Such a circumstance could only exasperate farther, and, when he ceased, the colour rose into her cheeks, and she said:

"In such cases as this, it is, I believe, the established mode to express a sense of obligation for the sentiments avowed, however unequally they may be returned. It is natural that obligation should be felt, and if I could feel gratitude, I would now thank you. But I cannot-- I have never desired your good opinion, and you have certainly bestowed it most unwillingly. I am sorry to have occasioned pain to anyone. It has been most unconsciously done, however, and I hope will be of short duration. The feelings which, you tell me, have long prevented the acknowledgment of your regard, can have little difficulty in overcoming it after this explanation." You can watch Colin Firth as Mr. Darcy both insult Elizabeth's family and social connections while expressing his love even though it's unreasonable and irresponsible of him in this clip from 1995 BBC adaptation of Pride and Prejudice: It's a long way from Jane Austen to Woody Allen!

Published on August 16, 2014 22:30

August 14, 2014

Elena Maria Vidal on Diane de Poitiers and Anne Boleyn

Historical fiction author Elena Maria Vidal discusses a biography of French king Henri II's long-time mistress Diane de Poitiers and compares and contrasts two royal marital triangles: Henri II-Catherine de Medici-Diane de Poitiers and Henry VIII-Katherine of Aragon-Anne Boleyn:

The Moon Mistress by Jehanne d'Orliac is a 1930 biography of the beloved mistress of Henri II of France. After reading about Henri's queen, Catherine de Medici, and taking her side, I thought it only fair to see what anyone had to say on Diane's behalf. By the way, I tend to take the side of the legitimate wife in such situations; I do so in the Catherine/Henri/Diane triangle as in the Katherine/Henry VIII/Anne Boleyn fiasco. One thing I have learned in Diane's favor, to put it gingerly, is that if Diane had wanted she could have talked Henri into annulling Catherine and marrying herself. She could have been Queen. She had complete dominion over her Henri in a way that Anne never had over her own Henry, except perhaps for a passing year or two. Instead, Diane did everything she could to strengthen Henri's marriage by encouraging him to sleep with his wife and beget progeny. There are several practical reasons for this: Diane was twenty years older than Henri and knew that Catherine had a better chance of bearing children for France, which she did. The bottom line, however, is that in spite of her scandalous relationship with the king, Diane was more conservative than Anne; she despised the new religious ideas which fascinated the latter and never wavered in her support for the Roman Catholic Church. Diane, strangely enough, is one reason why France and the royal family remained Catholic.

Why do I keep dragging in Anne Boleyn? Anne and Diane were both ladies-in-waiting to Queen Claude of France and must surely have known each other. Even then, Diane was the more conservative, preferring the the staid household of Queen Claude to the licentious court at large. Anne, according to d'Orliac's book, finding the placid routine of the Queen to be deadly dull, asked to be transferred to the more lively service of the Duchessse d'Alençon. Diane, by that time, was already happily married to Louis de Brézé, a much older man known as the Grant' Sénéchal. He adored his young wife and after his death she wore mourning for the rest of her life, as well as the title of the Grant Sénéchalle.

Until she became Henri's mistress, Diane was known for her chastity and faithfulness to her husband and to his memory, and for her dedication to bringing up her daughters in a proper Christian manner. She was an outdoorsy sort and lived for the hunt, in accord with her name. Her early education had been flawless. Diane had been brought up in the court of the regent Anne de Beaujeu, daughter of Louis XI, who ruled during the minority of her brother Charles VIII. Anne made certain all the girls in her care were thoroughly versed in music, literature, history and the classics. In Anne's household, Diane also learned how to be a great lady and skilled courtier. She was known for her integrity, grace, intellect, and charities. This was no small feat.

The Renaissance, though much-lauded as a time for rediscovering the learning and cultural riches of ancient Greece and Rome, brought with it a renewed fascination with paganism, the occult, and alchemy, as well as a general decadence which permeated the great courts of Europe, including the papal court. Such decadence and total disregard of morality spurred on the Protestant "reformers" who offered a "pure" Christianity. Diane found herself a widow with young daughters caught amid a power struggle with the Reformers for control of the French throne. The mistress of Henri's father Francis I leaned towards the Protestants, whereas Henri's Catholic wife, the young Catherine Medici, was deeply enthralled with her astrologers and alchemists. Diane, as royal mistress, a queen in all but name, kept Henri, his children, and his court from chaos through her ability to manage people as well as finances and prickly situations. Under Henri II, France recovered from the debts of Francis I while experiencing a flourishing of the arts.

Read the rest here.

By the way, Elena Maria Vidal is preparing her latest novel for publication--she sent me the manuscript for review a couple of months ago and I contributed a back cover blurb--and now she's sent me a proof copy. The Paradise Tree is set for release in October this year and I highly recommend it. She is also raising some funds to cover publication and marketing expenses. Read more here.

The Moon Mistress by Jehanne d'Orliac is a 1930 biography of the beloved mistress of Henri II of France. After reading about Henri's queen, Catherine de Medici, and taking her side, I thought it only fair to see what anyone had to say on Diane's behalf. By the way, I tend to take the side of the legitimate wife in such situations; I do so in the Catherine/Henri/Diane triangle as in the Katherine/Henry VIII/Anne Boleyn fiasco. One thing I have learned in Diane's favor, to put it gingerly, is that if Diane had wanted she could have talked Henri into annulling Catherine and marrying herself. She could have been Queen. She had complete dominion over her Henri in a way that Anne never had over her own Henry, except perhaps for a passing year or two. Instead, Diane did everything she could to strengthen Henri's marriage by encouraging him to sleep with his wife and beget progeny. There are several practical reasons for this: Diane was twenty years older than Henri and knew that Catherine had a better chance of bearing children for France, which she did. The bottom line, however, is that in spite of her scandalous relationship with the king, Diane was more conservative than Anne; she despised the new religious ideas which fascinated the latter and never wavered in her support for the Roman Catholic Church. Diane, strangely enough, is one reason why France and the royal family remained Catholic.

Why do I keep dragging in Anne Boleyn? Anne and Diane were both ladies-in-waiting to Queen Claude of France and must surely have known each other. Even then, Diane was the more conservative, preferring the the staid household of Queen Claude to the licentious court at large. Anne, according to d'Orliac's book, finding the placid routine of the Queen to be deadly dull, asked to be transferred to the more lively service of the Duchessse d'Alençon. Diane, by that time, was already happily married to Louis de Brézé, a much older man known as the Grant' Sénéchal. He adored his young wife and after his death she wore mourning for the rest of her life, as well as the title of the Grant Sénéchalle.

Until she became Henri's mistress, Diane was known for her chastity and faithfulness to her husband and to his memory, and for her dedication to bringing up her daughters in a proper Christian manner. She was an outdoorsy sort and lived for the hunt, in accord with her name. Her early education had been flawless. Diane had been brought up in the court of the regent Anne de Beaujeu, daughter of Louis XI, who ruled during the minority of her brother Charles VIII. Anne made certain all the girls in her care were thoroughly versed in music, literature, history and the classics. In Anne's household, Diane also learned how to be a great lady and skilled courtier. She was known for her integrity, grace, intellect, and charities. This was no small feat.

The Renaissance, though much-lauded as a time for rediscovering the learning and cultural riches of ancient Greece and Rome, brought with it a renewed fascination with paganism, the occult, and alchemy, as well as a general decadence which permeated the great courts of Europe, including the papal court. Such decadence and total disregard of morality spurred on the Protestant "reformers" who offered a "pure" Christianity. Diane found herself a widow with young daughters caught amid a power struggle with the Reformers for control of the French throne. The mistress of Henri's father Francis I leaned towards the Protestants, whereas Henri's Catholic wife, the young Catherine Medici, was deeply enthralled with her astrologers and alchemists. Diane, as royal mistress, a queen in all but name, kept Henri, his children, and his court from chaos through her ability to manage people as well as finances and prickly situations. Under Henri II, France recovered from the debts of Francis I while experiencing a flourishing of the arts.

Read the rest here.

By the way, Elena Maria Vidal is preparing her latest novel for publication--she sent me the manuscript for review a couple of months ago and I contributed a back cover blurb--and now she's sent me a proof copy. The Paradise Tree is set for release in October this year and I highly recommend it. She is also raising some funds to cover publication and marketing expenses. Read more here.

Published on August 14, 2014 22:30

August 13, 2014

The Martyrs of Otranto and Today

You may have seen this symbol used as a facebook profile picture--it is the Arabic letter Nun standing for Nazarene, used as a negative epithet against Christians in Iraq. It was drawn, in red, on the walls of Christian homes, marking the homes for destruction and the Christians for their choice: convert, die, or leave. At least they were allowed to leave. The Martyrs of Otranto were not given that last option on August 14, 1480, as Dr. Matthew Bunson explains:

On August 14, 1480, a massacre was perpetrated on a hill just outside the city of Otranto, in southern Italy. Eight hundred of the city's male inhabitants were taken to a place called the Hill of Minerva, and, one by one, beheaded in full view of their fellow prisoners. The spot forever after became known as the Hill of the Martyrs.

In medieval warfare, the bloody execution of a city's population was commonplace, but what happened at Otranto was unique. The victims on the Hill of Minerva were put to death not because they were political enemies of a conquering army, nor even because they refused to surrender their city. They died because they refused to convert to Islam. The 800 men of Otranto were martyrs, the first victims of what was fully expected to be the relentless conquest of Italy and then all of Christendom by the armies of the Ottoman Empire. Because of their sacrifice, however, the Ottoman invasion was slowed and Rome was spared the same fate that had befallen Constantinople only 27 years before.

The town of Otranto held out against the Turkish invaders and when they were finally defeated, they faced their choice:

The Pasha Ahmet ordered the men of Otranto, 800 exhausted, beaten, and starved survivors of the battle, to be brought before him. The Pasha informed them that they had one chance to convert to Islam or die. To convince them, he instructed an Italian apostate priest named Giovanni to preach. The former priest called on the men of Otranto to abandon the Christian faith, spurn the Church, and become Muslims. In return, they would be honored by the Pasha and receive many benefits.

One of the men of Otranto, a tailor named Antonio Primaldi (he is also named Antonio Pezzulla in some sources), came forward to speak to the survivors. He called out that he was ready to die for Christ a thousand times. He then added, according to the chronicler Giovanni Laggetto in the Historia della guerra di Otranto del 1480:

My brothers, until today we have fought in defense of our country, to save our lives, and for our lords; now it is time that we fight to save our souls for our Lord, so that having died on the cross for us, it is good that we should die for him, standing firm and constant in the faith, and with this earthly death we shall win eternal life and the glory of martyrs. [author translation]

At this, the men of Otranto cried out with one voice that they too were willing to die a thousand times for Christ. The angry Pasha Ahmed pronounced his sentence: death.

The next morning, August 14, the 800 prisoners were bound together with ropes and led out of the still-smoking battleground of Otranto and up the Hill of Minerva. The victims repeated their pledge to be faithful to Christ, and the Ottomans chose the courageous Antonio Primaldo as the first to be executed.

The old tailor gave one final exhortation to his fellow prisoners and knelt before the executioner. The blade fell and decapitated him, but then, as the chronicler Saverio de Marco claimed in the Compendiosa istoria degli ottocento martini otrantini ("The Brief History of the 800 Martyrs of Otranto"), the headless corpse stood back upright. The body supposedly proved unmovable, so it remained standing for the entire duration of the gruesome executions. Stunned by this apparent miracle, one of the executioners converted on the spot and was immediately killed. The executioners then returned to their horrendous business. The bodies were placed into a mass grave, and the Turks prepared to begin their march up the peninsula toward Rome. Otranto was in ruins, its population gone, its men dead and thrown into a pit, seemingly to be forgotten.

Last year, when Pope Francis canonized the 800 martyrs of Otranto, the mainstream media was in full Pope Benedict vs. Pope Francis mode, and reporters suggested that Pope Francis was risking the possibility of dialogue with the Muslim world and I wrote about it here.

This year, as we celebrate their feast, it's important to note that the Vatican (specifically, The Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue) is calling on Muslim leaders to address recent atrocities for the sake of dialogue with the Christian world:

The Vatican called on Muslim leaders to condemn the "barbarity" and "unspeakable criminal acts" of Islamic State militants in Iraq, saying a failure to do so would jeopardize the future of interreligious dialogue.

"The plight of Christians, Yezidis and other religious and ethnic communities that are numeric minorities in Iraq demands a clear and courageous stance on the part of religious leaders, especially Muslims, those engaged in interfaith dialogue and everyone of goodwill," said a statement from the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue released by the Vatican Aug. 12.

"All must be unanimous in condemning unequivocally these crimes and must denounce the invocation of religion to justify them," the statement said. "Otherwise, what credibility will religions, their followers and their leaders have? What credibility would remain to the interreligious dialogue patiently pursued in recent years?"

The document noted that the "majority of Muslim religious and political institutions" have opposed the Islamic State's avowed mission of restoring a caliphate, a sovereign Muslim state under Islamic law, to succeed the Ottoman Caliphate abolished after the founding of modern Turkey in 1923.

The Vatican listed some of the "shameful practices" recently committed by the "jihadists" of the Islamic State, which the U.S. government has classified as a terrorist group. Among the practices cited:

-- "The execrable practice of beheading, crucifixion and hanging of corpses in public places."

-- "The choice imposed on Christians and Yezidis between conversion to Islam, payment of tribute or exodus."

-- "The abduction of girls and women belonging to the Yezidi and Christian communities as war booty."

-- "The imposition of the barbaric practice of infibulation," or female genital mutilation.

"No cause can justify such barbarity and certainly not a religion," the document said.

"Religious leaders also are called on to exercise their influence with the rulers for the cessation of these crimes, the punishment of those who commit them and the restoration of the rule of law throughout the country, ensuring the return home of the deported," the Vatican said. "These same leaders should not fail to emphasize that the support, financing and arming of terrorism is morally reprehensible."

You can read the full statement here.

Published on August 13, 2014 22:30

August 12, 2014

Book Review: "Papist Devils"

As mankind become more liberal they will be more apt to allow that all those who conduct themselves as worthy members of the community are equally entitled to the protection of civil government. I hope ever to see America among the foremost nations in examples of justice and liberality. And I presume that your fellow-citizens will not forget the patriotic part which you took in the accomplishment of their Revolution, and the establishment of their government; or the important assistance which they received from a nation in which the Roman Catholic faith is professed.--George Washington to prominent Catholics who congratulated himon his election as the first President of the United States, March 15, 1790

Robert Emmett Curran may cover some of the same ground at Papist Patriots in his telling of the history of Catholics in Maryland, but by examining the Catholic populations of the British West Indies and other colonies like New York and Pennsylvania he broadens the range of this study:

This is a brief [320 pages] highly readable history of the Catholic experience in British America, which shaped the development of the colonies and the nascent republic in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Historian Robert Emmett Curran begins his account with the English reformation, which helps us to understand the Catholic exodus from England, Ireland, and Scotland that took place over the nearly two centuries that constitute the colonial period. The deeply rooted English understanding of Catholics as enemies of the political and religious values at the heart of British tradition, ironically acted as a catalyst for the emergence of a Catholic republican movement that was a critical factor in the decision of a strong majority of American Catholics in 1775 to support the cause for independence.

Papist Devils utilizes archival material, newspapers, and other contemporary records in addition to a broad array of general histories, monographs, and dissertations dealing with the British Atlantic world.The unprecedentedly broad scope of this study, which encompasses not only the thirteen colonies that took up arms against Britain in 1775, but also those in the maritime provinces of Canada as well as the ones in the West Indies, constitutes a unique coverage of the British Catholic colonial experience, as does the extension of the colonial period through the American Revolution, which was its logical dénouement.

He clearly demonstrates the long reach of the English Reformation and its penal laws against Catholics, Catholic priests, and the Catholic Mass. There was a constant tension between Catholics and Anglicans and other Protestants even in those colonies founded expressly to allow religious liberty, Maryland and New York. I think we forget what "York" represents in that name: James, the Duke of York, Charles II's Catholic convert brother and heir. The long recusant period had inspired a longing for religious freedom in Catholics and a continued suspicion and hatred of Catholics in Anglicans and Protestant dissenters from the Church of England. Catholics in British America inherited the legacy of English fear of them as disloyal, dangerous, and conspiratorial--and as enemies of freedom! Hatred and fear lead to paranoia and bigotry of course, and the Catholics of Maryland and New York soon found themselves disenfranchised and penalized for their faith.

When the British Parliament recognized the freedom of Catholics in French Canada to practice their faith (the Quebec Act), British Americans regarded this as an act of tyranny. But it was through French Canada that British Americans began to change their minds a little about Catholics--because they needed Catholics to reach out to Quebec to join the revolution. Benjamin Franklin, enlightened Catholic hater though he was, found out by going to Quebec with Charles Carroll of Carrolton and his cousin Father John Carroll that Catholics are human beings. Franklin was touched by John Carroll's concern for him when he fell ill. Although the mission failed, George Washington had forbidden the celebration of Pope Day (Guy Fawkes Day) on the 5th of November, pointing out that it made little sense to attack the spiritual leader of possible French Catholic allies. The support of French and Polish Catholic military leaders extended the ban on burning the Pope in effigy.

It almost seems miraculous that Catholics were finally allowed to participate in the founding of the United States of America, based on the history of anti-Catholic prejudice in the British American colonies. In the West Indies, that fear and hatred was focused on the Irish indentured servants, temporary slaves of the sugar plantations, and those Irish who had been sent into true slavery during the English Civil War and Cromwell's campaigns in Ireland. Their land had been confiscated, their families divided, and they were branded, sometimes literally, as felons and slaves. With the African slaves brought to the West Indies, they sometimes resisted the cruelty of the great planters and then were ruthlessly put down and punished.

On the Continent, the Seven Years War/French and Indian War inspired more anti-Catholic fervor with the French as enemies, and the horrible dispersal of the French Catholic Acadians of Nova Scotia was hailed as a great British accomplishment! Fear of Catholic conspiracies against the British Empire in time of war was exacerbated by evangelical ministers like the cross-eyed George Whitfield, friend of Charles and John Wesley, during the first Great Awakening. He saw the Seven Years War as a vast Catholic wing conspiracy against Protestantism (Arminian or not). Wherever Catholics congregated in significant numbers they were suspected of some conspiracy against British forces in the field of battle, and Catholics were harassed, attacked, and taxed at a higher rate.

The irony is that because the Pope did not take sides in the American Revolution, Catholics were free to choose which side to support--some were Loyalists, fighting for King George--but Commodore John Barry exemplifies the contribution Catholics made to the war. While British Americans had regarded the Catholic Church as the source and summit of tyranny in the world, Catholics supported them in their efforts to throw off tyranny! Pardon the anachronism, but it must have blown their minds!

Curran narrates this story and its surprising conclusion vividly and clearly, describing conflicts, personalities, and events throughout British American history. The bibliography is excellent and the book is well illustrated. Highly recommended.

Published on August 12, 2014 22:30

August 11, 2014

Iconoclasm in the Long English Reformation

From Once I Was a Clever Boy, some notes on iconoclasm, the destruction of religious images, during the Long English Reformation (I corrected some typos):

I pointed to four main phases of iconoclasm in this country. These firstly are the period 1536-1539 when the monasteries were dissolved and there was the attack of shrines and relics, and especially on the cult of St Thomas of Canterbury. Secondly there is the period from 1548 to 1553 under the Edwardian reform which saw the attack on veneration of the Virgin Mary, the dissolution of the chantries, liturgical change with the imposition of the First and Second Prayer books in 1549 and 1552 and the expropriation of church goods in 1552. Thirdly there was an outbreak of image breaking in the period after 1559 when the Elizabethan settlement was brought in. This lasted until about 1562, but was followed by neglect and abandonment - notably the cessation of worship in the chancels of churches and their consequent appropriation for seating. The fourth phase is that in the First Civil War of 1642 to 1646, with attacks on cathedrals such as Canterbury, Lincoln, Peterborough, and Worchester, and the activities of people such as William Dowsing in East Anglia, who went round destroying the relics of Popery in the parish churches of the region.

All this was followed by two centuries of neglect, before the nineteenth century got to work restoring (sometimes too enthusiastically it has to be said) and conserving our medieval heritage.

This will be a series of posts, so follow it here.

I pointed to four main phases of iconoclasm in this country. These firstly are the period 1536-1539 when the monasteries were dissolved and there was the attack of shrines and relics, and especially on the cult of St Thomas of Canterbury. Secondly there is the period from 1548 to 1553 under the Edwardian reform which saw the attack on veneration of the Virgin Mary, the dissolution of the chantries, liturgical change with the imposition of the First and Second Prayer books in 1549 and 1552 and the expropriation of church goods in 1552. Thirdly there was an outbreak of image breaking in the period after 1559 when the Elizabethan settlement was brought in. This lasted until about 1562, but was followed by neglect and abandonment - notably the cessation of worship in the chancels of churches and their consequent appropriation for seating. The fourth phase is that in the First Civil War of 1642 to 1646, with attacks on cathedrals such as Canterbury, Lincoln, Peterborough, and Worchester, and the activities of people such as William Dowsing in East Anglia, who went round destroying the relics of Popery in the parish churches of the region.

All this was followed by two centuries of neglect, before the nineteenth century got to work restoring (sometimes too enthusiastically it has to be said) and conserving our medieval heritage.

This will be a series of posts, so follow it here.

Published on August 11, 2014 22:30

August 10, 2014

Buckfast Abbey on the BBC

Buckfast Abbey was featured on the BBC's Choral Evensong programme last week and the Vesper service is still on-line today. It was recorded for the Feast of the Transfiguration:

Choral Evening Prayer from Buckfast Abbey, Devon during the 2014 Exon Singers’ Festival – recorded Thurs 31st July (rpt Sun 10th Aug)

Introit: An Introit for Transfiguration (Robin Holloway) (First performance)

Responses: Plainsong

Office Hymn: O vision blest of heavenly light (Coelestis gloriae)

Psalms: 97, 121 (Plainsong; Robin Holloway)

First Lesson: 2 Peter 1 vv16-19

Anthem: Christus Jesus splendor Patris (Massaino)

Second Lesson: Matthew 17 vv1-9

Homily: The Rt Revd David Charlesworth, Abbot of Buckfast

Canticle: Magnificat quarti toni (Palestrina)

Lord’s Prayer (Toby Young ) (First performance)

Motet: Ave Maria (Josquin)

Final Hymn: ‘Tis good, Lord, to be here (Carlisle)

Organ Voluntary: Hymne d’Actions de graces: “Te Deum” (Langlais)

Richard Wilberforce (Music Director)

Jeffrey Makinson (Organist)

Buckfast Abbey was founded first in the 11th century as a Benedictine abbey, and then Cistercians took over. They surrendered the abbey in 1540 and it was used as a quarry after Thomas Cromwell's Court of Augmentations granted it to Sir Thomas Dennis of Holcombe Burnell. French Benedictines returned to the site in 1882 and built a new abbey, officially opened in 1902, with the abbey church pictured above (from Wikipedia Commons) completed in 1938. Buckfast Abbey sells a tonic wine and raises bees to be self-sufficient.

More information about the Exon Singers' Festival here.

Published on August 10, 2014 23:00

Back to Provence and Pagnol

Many, many years ago my husband and I watched Jean de Florettte and Manon of the Springs, two wonderful movies based on Maurice Pagnol's novels. We also saw My Father's Glory and My Mother's Castle--I know that we watched them in a great movie house in Augusta, Kansas, which was festooned with neon. Last month, we watched

The Well-Digger's Daughter

, a remake of a Pagnol movie, produced, directed, and starring Daniel Auteuil, who played the role of Ugolin Soubeyran, the carnation grower in the Jean/Manon movies.

Many, many years ago my husband and I watched Jean de Florettte and Manon of the Springs, two wonderful movies based on Maurice Pagnol's novels. We also saw My Father's Glory and My Mother's Castle--I know that we watched them in a great movie house in Augusta, Kansas, which was festooned with neon. Last month, we watched

The Well-Digger's Daughter

, a remake of a Pagnol movie, produced, directed, and starring Daniel Auteuil, who played the role of Ugolin Soubeyran, the carnation grower in the Jean/Manon movies.Set in Provence just before and during World War I, this is a story about a beautiful young girl who foolishly falls for a young man. She finds herself pregnant and abandoned (she thinks) by him, and his parents will not acknowledge their son's responsibility. Pascal Amoretti, the well digger, considers his perfect, good daughter Patricia's sin a great shame to the family--especially since Jacques Mazel's family will not accept his daughter as their son's wife--and sends her away to his sister's to carry the baby to term without anyone knowing what's happened.

When one of his neighbors and another of his daughters visits the baby and he finds out it's a boy, Pascal, who has no son, goes to his sister and brings Patricia and "Amoretti" as he calls him home. The other family also values the little boy when they hear that Jacques is missing in action and believed dead--they want to have contact with their grandson--and confess their role in Patricia's shame.

I won't go into more detail about how the family honor is restored. Pagnol's very human, almost unbaptized portrayals of Provencal life always seem to be based on ideals of family versus stranger, honor versus shame--when Pascal accuses Patricia of "sin" he is not really thinking of her fall in terms of religion: he does not tell her to go to Confession and repent of her sin. He thinks about the family's honor and the shame her pregnancy will bring upon the family. She did not sin against God; she sinned against him and his ideal of her. He sends her away with a kiss that he tells her is only for the benefit of her sisters, not out of any affection. When Jacques Mazel's father and mother reject the pregnant Patricia and add the accusations of entrapment and blackmail, they are again concerned about their own standing in the community.

The production values of the movie are beautiful--Auteuil made the movie with film, not digitally--and the score by Alexandre Desplat is evocative. These movies always inspire me to buy some good dry red wine, some crusty French bread, have some olives, and a delicious soup.

Published on August 10, 2014 22:30

August 9, 2014

A Tree that Inspired Tolkien

This is Oxfordshire reports some bad news for a tree that's said to have inspired Tolkien's creation of the Ents of Middle Earth. With the headline "The Ent is nigh for Tolkien tree" they note recent damage to the tree and the decision to cut it down:

This is Oxfordshire reports some bad news for a tree that's said to have inspired Tolkien's creation of the Ents of Middle Earth. With the headline "The Ent is nigh for Tolkien tree" they note recent damage to the tree and the decision to cut it down: IT is said to have influenced the work of JRR Tolkien and inspired creatures in Lord of the Rings.

But now an iconic pinus negra – or black pine – is being felled in Oxford University’s Botanic Garden after two of its limbs fell off over the weekend.

Experts at Oxford City Council and the university have examined the 20-metre tall tree and decided it has to be cut down, but have not been able to determine what caused the limbs to fall off, damaging a wall.

Dr Alison Foster, acting director of the garden, said: “The black pine was a highlight of many people’s visits to the Botanic Garden and we are very sad to lose such an iconic tree.”

Tolkien, who was a fellow of Pembroke College and Merton College and is buried in Wolvercote Cemetery, was extremely fond of the tree and has been pictured sitting underneath it and standing beside it.

The article goes to explain how much Tolkien “hated the wanton destruction of trees for no reason . . ." Those scenes in The Lord of the Rings, both in the books and the films, when Saruman's Orcs destroy the forests of Isengard to create weapons (The Fellowship of the Ring) and then when the Ents discover what Saruman has done and march to besiege him and destroy Isengard (The Two Towers) certainly demonstrate Tolkien's feelings. [The image of Treebeard is from Wikipedia Commons, created by Tom Loback and used under a Creative Commons License: Attribution: I, TTThom.]

With those sentiments about trees, Tolkien agreed with the spirit of Gerard Manley Hopkins' poem, "Binsey Poplars. felled 1879":

MY aspens dear, whose airy cages quelled, Quelled or quenched in leaves the leaping sun, All felled, felled, are all felled; Of a fresh and following folded rank Not spared, not one That dandled a sandalled Shadow that swam or sankOn meadow and river and wind-wandering weed-winding bank. O if we but knew what we do When we delve or hew— Hack and rack the growing green! Since country is so tender To touch, her being só slender, That, like this sleek and seeing ball But a prick will make no eye at all, Where we, even where we mean To mend her we end her, When we hew or delve:After-comers cannot guess the beauty been. Ten or twelve, only ten or twelve Strokes of havoc únselve The sweet especial scene, Rural scene, a rural scene, Sweet especial rural scene.

Published on August 09, 2014 23:00