Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 224

September 4, 2014

Leanda de Lisle on Borman's Cromwell

Writing for The Spectator, Leanda de Lisle reviews a new biography of Thomas Cromwell:

Writing for The Spectator, Leanda de Lisle reviews a new biography of Thomas Cromwell:The travel writer Colin Thubron once told me that to understand a country and its people he first asks, ‘What do they believe?’ This is also a good place to begin when writing about the past, not least when your subject is Thomas Cromwell, a key figure in the English Reformation. But Tracy Borman’s Cromwell doesn’t have beliefs so much as qualities: ones that will appeal to fans of the fictional Cromwell of Hilary Mantel’s Tudor novels.

Borman’s Cromwell likes women, and is nice to the poor. True he fits up Anne Boleyn on treason charges, and has the illiterate nun Elizabeth Barton executed without a trial. But then he is a ‘pragmatist’, and much of his killing, torturing and bullying is ‘self-defence’. He is a loving husband, or at least there is no evidence that he isn’t. He is also a ‘witty and generous host’, unless your name is Mark Smeaton. In which case, your arrival at Cromwell’s lovely home will be followed by your confessing to having had sex with Henry’s VIII’s wife. Your next meal will be in the Tower.

This Cromwell also dislikes many bad things. Neighbours, for example: at least those with possessions he covets. When he builds a new house he pinches the gardens of those around him (and there are other lapses of kindness to ordinary folk). But in particular he hates the ‘corrupt’ Roman Catholic church, its ‘medieval seven sacraments’ (don’t they still have seven?), and ‘idolatry’. Although (naturally) a great lover of art, this obliges him to order that ‘statues, rood screens and images be destroyed in churches and religious houses across the land’. And in the case of monastic land, it soon belongs to the king.

Read the rest here. De Lisle is not impressed by Borman's understanding of what Cromwell believed about Jesus Christ and His Church:

Between 1533 and 1540 Cromwell carried out Henry VIII’s will as his secretary, enforcer and vicar-general. In this, according to Borman, he was always ‘a pragmatist rather than an idealist’ and ‘Henry VIII’s most faithful servant’. Like the king, Cromwell remained a Catholic, just not a ‘Roman’ Catholic, we are told. Unfortunately, Borman is very confusing on the religious issues. One minute Cromwell is ‘ambivalent’ about the Lutheran doctrine of justification by faith alone. Next he is a ‘radical’, pleased to see that the 1536 Ten Articles on religion have the words ‘justification’ and ‘faith’ used in close proximity. He is ‘frustrated’ that they continue to ‘assert that the body and blood of Christ were really present at the Eucharist’. Yet, we are reassured later, Cromwell believed firmly in the real presence.

Could Thomas Cromwell not have known what he believed about how Jesus Christ intended His Church to lead souls to Heaven? If he was so inconsistent, what he trying to achieve in all the religious changes he helped implement? If it was only his power and influence over his monarch, his wealth and financial security--then he is no one to admire put only pity, for then he would have been a fool. All through his career at Henry VIII's Court he had seen people fall from power (and he'd had a hand in some of those falls): he should have known he could not survive for long.

Published on September 04, 2014 22:30

September 3, 2014

Mistaken Identity in Bavaria

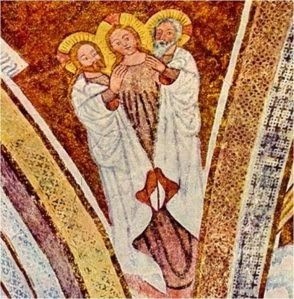

Writing about St. James in Urschalling, near Prien am Chiemsee in The Wall Street Journal, H. George Fletcher comments on one of its most famous pieces of art, and the persistent error about what it depicts:

The single outstanding feature is described as a depiction of the Trinity, the triune rendition of one God in three divine persons, a depiction reportedly unique in art history, conforming to neither Eastern nor Western Christian iconography. In a diminishing triangular segment on the north side of the interior dome of the apse, between two ribs of the arches, three figures stand side by side, initially distinct and in seeming equivalence. The bodies of the figures begin to combine as they fill the long shield-shaped section that ends in a point, finally merging. The Trinity is conventionally shown as a seated God the Father, holding the crucified Christ, with the dove of the Holy Spirit hovering above. Here, there is a white-robed, white-bearded elderly man to the viewer's right, a white-robed, dark-bearded younger man to the left, and between them, a brown-robed, smooth-faced figure with long, flowing brown locks framing the face. Each is distinguished with a nimbus.

Its importance and fame notwithstanding, there is a considerable problem in identifying this depiction as the Trinity, because it is not the Trinity at all, but rather the reception of the Virgin in Paradise. Mary is welcomed and flanked by God the Father and God the Son, her own son, their respective outside arms embracing her protectively. It is entirely logical to find this above the altar, continuing the Mariology of other murals. The directly opposite southern section of the dome contains the Madonna and Child. An erroneous conclusion at an earlier date has been perpetuated, and this proof by progressive assertion, as a mentor of mine used to say, has canonized the "Trinity" painting as the most significant of the murals. It ought not to remain misidentified. It can stand on its own terms as an early and important vision of the female—indeed, of the female—in Christian iconography.

Despite its historical importance, St. James, Urschalling seems to have garnered only German-language attention and study. It greatly deserves to be far more widely known and visited.

I would like to know more about how this image has been misinterpreted and why Mr. Fletcher is so certain his view is correct. Neither interpretation seems to rest on a common iconography--he outlines the usual imagery for the Trinity, and while the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Coronation of the Blessed Virgin Mary are common images, the "reception of the Virgin in Paradise" is not an image I've seen.

Published on September 03, 2014 22:30

September 2, 2014

Book Review: The Last White Rose

As Kirkus Reviews describes this book:

As Kirkus Reviews describes this book:The Tudors have been written about ad nauseam, but historian Seward (Eugenie: The Empress and Her Empire, 2004, etc.) opens another branch of study harkening back to their beginnings at the Battle of Bosworth of 1485.

The defeat of King Richard III did not eliminate all claimants to the crown. After his victory, Henry VII spent his reign ruthlessly quashing one after another. The genealogical tables at the front of Seward’s book are indispensable for this and any English history, as authors must carefully refer to characters by one name only. For instance, John de la Pole, the Duke of Suffolk, and his sons, John, Earl of Lincoln, and Edmund, Earl of Suffolk, had claim to the crown, and all suffered for it. Choosing a single moniker for each character is preferred, except, of course, that Henry VII and his son, Henry VIII, tended to bestow and take away titles according to whim or worry. The paranoia of Henry VII was actually justified, as the Yorkist family had many eligible candidates, and popular support for restoring their reign was widespread. Challengers found support from Margaret of Burgundy, sister to kings Richard III and Edward IV, the French, who were always ready to stir things up, and the Irish, firmly in the Yorkist camp. By far the most interesting pretender was Richard de la Pole, who was educated at Henry VIII’s expense, created a cardinal by the pope without ordination and considered as a mate for Princess Mary. (sic!)* Henry VIII was pathologically suspicious and saw conspiracies in every shadow, and the cream of England’s aristocracy paid the price. The story of the descendants of the White Rose adds yet another black mark against the first two Tudors, as if they needed more.

A fresh look at a well-worn field of study, appropriate for general readers.

*That's a strange error: I'm sure the reviewer meant to cite Reginald Cardinal Pole as "the most interesting pretender", although there was a pretender named Richard de la Pole who died at the Battle of Pavia in 1525, fighting alongside King Francis I of France. After the battle, Richard de la Pole was buried in the Basilica of San Pietro in Ciel d'Oro--where St. Augustine of Hippo is also buried. Henry VIII rejoiced greatly when he heard that Richard de la Pole had died: one fewer White Rose or rival to get rid of by assassination or execution!

One thing that Seward does very well here is tell his story without too many digressions--he tells enough of what is going on outside of these rebellions and pretenders for necessary context--but not so much that he writes another book about Henry VIII, his six wives and four children, the English Reformation, the Dissolution of the Monasteries, or the Pilgrimage of Grace. In The Last White Rose: The Secret Wars of the Tudors, he depicts both Henry VII and Henry VIII as most uneasy monarchs, fearful of and vindictive toward anyone who had a claim upon the crown the Tudors plucked from the House of York. Any noble family, like the Howards, the de la Poles, the York/Poles (Margaret of York and her grown children), the Courtenays, the Staffords, etc., had much to fear from the Tudors, whether or not they really were plotting to supplant or succeed their monarch. Seward notes that the White Rose faction missed their one great chance when they did not get behind--or rather, take leadership of--the Pilgrimage of Grace. With an army of 30 to 40 thousand behind them, the House of York could have taken England back from the Tudors, stopped the English Reformation and the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

Published on September 02, 2014 22:30

September 1, 2014

The Fire of London and the Gregorian Calendar

The Great Fire of London began on September 2 in Pudding Lane 348 years ago today (1666) and would burn until September 5, destroying 13,200 houses, 87 parish churches, and many government buildings. King Charles II and his brother James, the Duke of York worked hard to direct fire-fighting efforts, but the fire's penultimate day, Tuesday, September 4th was the day of greatest destruction, as St. Paul's Cathedral caught fire and was ruined that day. This was the great medieval, Gothic cathedral built between 1089 and 1314, containing wondrous stained glass and with a tall spire. It had of course fallen into disrepair, having been damaged by Puritan forces during the Civil War.

Its destruction gave Sir Christopher Wren the opportunity to design and build a new Anglican Cathedral influenced by the design of St. Peter's in Rome and Val-de-Grace in Paris, along with 50 other Anglican churches.

In the aftermath of the fire, someone had to be blamed, and Catholics were held responsible. A French watchmaker did claim responsibility (as an agent of the Pope) but after he was hung at Tyburn, authorities found out he had arrived in London two days after the fire started. Too late!

Charles II commissioned The Monument to the Great Fire of London, which Robert Hooke, not Sir Christopher Wren, designed, and it was built between 1671 and 1677. In 1681, in the midst of the Popish Plot, words were added to the Monument to reflect fear of Catholics and blame them for the Great Fire:

'Here by ye permission of heaven, hell broke loose upon this protestant city from the malicious hearts of barbarous papists, by hand of their agent Hubert, who confessed, and on ye ruines of this place declared the fact for which he was hanged (vizt) that here began that dredfull fire, which is described and perpetuated on and by the neighbouring pillar. Erected Anno 1681 in the Majoraltie of Sr Patience Ward Kt.’

In his Moral Essays, written in 1733-1734 (Epistle iii, line 339) Alexander Pope noted of those words:

Where London's column, pointing at the skies,

Like a tall bully, lifts the head, and lies.

Because, remember, authorities already knew that Hubert could not have started the Great Fire--so they inscribed a lie. During the reign of James II, the anti-Catholic words were removed; with the Dutch invasion and coup d'etat of the Glorious Revolution they were restored and remained there until 1830 after Catholic Emancipation.

It was also on September 2 in 1752 that England finally caught up with the times, adopting the Gregorian calendar. One reason it took so long (Pope Gregory XIII introduced the reformed calendar in 1582, correcting errors in the calculation of Easter presented by the old Julian Calendar) was indeed the source of the correction: the Papacy and the Catholic Church. History Today has an article in its archives about England finally admitting that Rome could be right about something--but it's behind the pay wall:

In 1750 England and her empire, including the American colonies, still adhered to the old Julian calendar, which was now eleven days ahead of the Gregorian calendar, introduced in 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII and in use in most of Europe.

Attempts in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to adopt the new calendar had broken on the rock of the Church of England, which denounced it as popish. The prime mover in changing the situation was George Parker, second Earl of Macclesfield, a keen astronomer and a Fellow of the Royal Society. He was assisted in his calculations by his friend James Bradley, the astronomer royal, and he gained the influential support of Philip Dormer Stanhope, the sophisticated fourth Earl of Chesterfield (of letters to his son fame), who squared it with Henry Pelham’s initially reluctant government.

It's just so sad and unjust when prejudice and bigotry influence our acceptance of facts: Catholics did not set fire to the city of London, there was no Popish Plot, and the Julian Calendar needed to be reformed.

Note that some think the Gregorian calendar needs to be replaced: here's some analysis of the perceived problems and proposed solutions.

Published on September 01, 2014 22:30

August 31, 2014

WWI Poet, Siegfried Sassoon, RIP

Siegfried Sassoon, the great World War I poet and Catholic convert, died on September 1, 1967--he was born on September 8, 1886, so he almost made it to his 81st birthday. There is a new biography of the poet, heroic soldier, novelist, and pacifist, published by The Overlook Press:

Siegfried Sassoon, the great World War I poet and Catholic convert, died on September 1, 1967--he was born on September 8, 1886, so he almost made it to his 81st birthday. There is a new biography of the poet, heroic soldier, novelist, and pacifist, published by The Overlook Press:Published to coincide with the centennial of the outbreak of the First World War, Siegfried Sassoon is the first complete biography of arguably the greatest English-language war poet. Hailed as “invaluable” by the Times and “thorough and perceptive” by the Observer, Siegfried Sassoon encompasses the poet’s complete life and works, from his patriotic youth that led him to the frontline, to the formation of his anti-war convictions, great literary friendships, and flamboyant love affairs. Written by biographer and scholar Jean Moorcroft Wilson, this single-volume opus also includes never-before-published poems that have only just come to light. With over a decade’s research, and unparalleled access to Sassoon’s private correspondence, Wilson presents the complete portrait, both elegant and heartfelt, of an extraordinary man, and an extraordinary poet.

“Soldiers are dreamers; when the guns begin they think of firelit homes, clean beds, and wives.” —Siegfried Sassoon

Jean Moorcroft Wilson lectures in English Literature at Birkbeck College, University of London. She is married to Virginia Woolfe's nephew, with whom she runs a publishing house. She is considered the foremost expert in Siegfried Sassoon.

He became a Catholic in 1957, and Joseph Pearce provides some background to his conversion:

The dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima inspired Sassoon to the same heights of horrified creativity as it had inspired Sitwell in the composition of her "three poems of the Atomic Age" . . . Sassoon's "Litany of the Lost" employed resonant religious imagery as a counterpoint to the post-war pessimism and alienation engendered by the descent from world war to Cold War. As with the previous war, the world had emerged from the nightmare of conflict into the desert of despair, transforming "wasteland" to nuclear waste.

The ending of the second of the century's global conflagrations marked the beginning of Sassoon's final approach to the Catholic faith. Influenced to a degree by Catholic friends such as Ronald Knox and Hilaire Belloc, but to a far greater degree by the experience of his own life, he was received into the Church in September 1957, shortly after his 71st birthday. After a lifetime of mystical searching he had finally found his way Home.

During his first Lent as a Catholic, Sassoon wrote "Lenten Illuminations," a candid account of his conversion which invites obvious comparisons with T.S. Eliot's "Ash Wednesday." The last decade of his life, like the last decades of the Rosary he came to love, was a quiet meditation on the glorious mysteries of faith. As ever, his meditations were expressed in memorable verse, particularly in the peaceful mysticism of "A Prayer at Pentecost," "Arbor Vitae," and "A Prayer in Old Age."

In 1960 Sassoon selected 30 of his poems for a volume entitled The Path to Peace, which was essentially an autobiography in verse. From the earliest sonnets of his youth to the religious poetry of his last years, Sassoon's intensely personal and introspective verse offered a sublime reflection of a life's journey in pursuit of truth. These, and not his diaries, his letters, or his prose, are the precious jewels of enlightenment that point to the soul within the man.

UPDATE: I looked at this biography in our local B&N bookstore yesterday: the author notes that Sassoon's conversion made him very happy for the rest of his life. He encountered some of the usual misunderstanding and anti-Catholic response to his conversion, but also made some great new contacts, particularly at Stanbrook Abbey. Joining the Catholic Church transformed Sassoon's moral and spiritual life.

Published on August 31, 2014 22:30

August 30, 2014

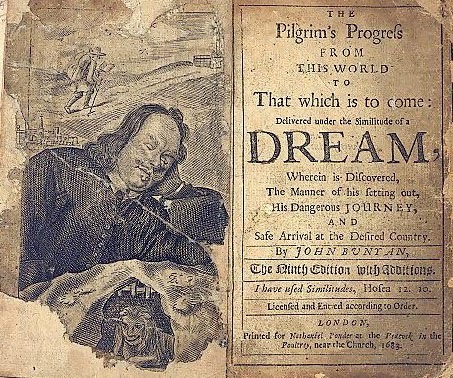

G.K. Chesterton on John Bunyan

John Bunyan, author of The Pilgrim's Progress, died on August 31, 1688. G.K. Chesterton wrote an introduction to Bunyan's great allegory:

John Bunyan was born in 1628, probably in the November of that year, since his baptism followed in that month. His birthplace was the village of Elsow, just outside Bedford. His family was a good example of a thing of which there are many examples, and of which there cannot be too many-- a sort of plebian aristocracy, plain and insignificant in name and handicraft, but rooted in the land like a royal dukedom. The notion that Bunyan's origin lies amid vagrant tinkers is an error; it lies amid highly respectable tinkers, whose presence can be traced for generations and who had left such evidences as a whole farm which had always been called "Bonyon's End." Bunyan's grandfather, Thomas Bunyan, was a small tradesman or "chapman" who died in 1641; of his father less is known, beyond the fact that he had three wives, of whom the second was the mother of John Bunyan, and the third was to all appearance his worst enemy.

He has left on record himself that his youth was riotous, but to judge by the specimens which he gives it would have seemed to boast only a very mild and clumsy sort of rioting. In all human probability he was really only a course and awkward boy, sometimes dropping in among dubious companions, far more often drifting off sulkily by himself. He served in early life in the army, no uncommon episode in the careers of that kind of sullen wastrel. Some dispute has arisen, not indeed about the actuality of his military service, but about the side on which he served in the Civil War. General internal evidence, however, as well as enormous moral probability, allot him to the Parliamentarian camp.

In the year of the Restoration he was arrested for having preached to unlawful assemblies, and was imprisoned in Bedford Gaol for twelve years. In this sudden isolation, shut out from effective acting or speaking, it occurred to him systematically to write, and he opened the first window on the dark and amazing drama which had been going on within his seemingly dull personality while he ran about the fields to be away from his stepmother or leaned on his pike by the watch fires of the great war.

He wrote "Grace abounding to the Worst of Sinners" perhaps the most powerful work ever wrought by genius with the materials of morbidity. Certainly no Parisian decadent, no Swinburnian poet, no Beardsleyian artist so completely contrived to give disease the vigor of health. It is the masterpiece of an element which has a right to have a masterpiece, since it is a living and recurring element-- the element of the dark and hysterical soul of early youth. It is the epic of the pessimism of boyhood.

During the same period he wrote a less-known work called "The Holy City." He was released in 1672, but as he refused to abandon his preaching, which was now powerful and popular, he was flung back again into prison in 1675. It was during this second detention that he wrote the work which has set him finally among the English immortals, "The Pilgrim's Progress." Many controversies have raged as to whether he owed the allegorical type of narrative to anything before him, but all the allegories mentioned in this connection are almost as unlike "The Pilgrim's Progress" as they are unlike "Vanity Fair." The Elstow tinker produced an original thing, if an original thing was ever produced. Nothing stronger can be said of it than that it dwarfs altogether into insignificance "Grace Abounding" published before it, and "The Holy War," published afterwards. Bunyan, released from prison, died quietly in 1688.

In his collection of essays The Thing (which we are reading in the Wichita branch of the American Chesterton Society), Chesterton writes "On Two Allegories"--Bunyan's in The Pilgrim's Progress and Dante's in The Divine Comedy, comparing and contrasting their allegories and the theologies on which they are based:

Mr. James Douglas, who once presented himself to me as a representative of Protestant truth, and who is certainly a representative of Protestant tradition, answered Mr. Alfred Noyes in terms very typical of the present state of that tradition. He said that we should salute Bunyan's living literary genius, and not bother our heads about Bunyan's obsolete theology. Then he added the comparison which seems to me so thought-provoking: that this is after all what we do, when we admire Dante's genius and not HIS obsolete theology. Now there is a distinction to be made here; if the whole modern mind is to realize at all where it stands. If I say that Bunyan's theology IS obsolete, but Dante's theology is NOT obsolete--then I know the features of my friend Mr. Douglas will be wreathed in a refined smile of superiority and scorn. He will say that I am a Papist and therefore of course I think the Papist dogmatism living. But the point is that he is a Protestant and he thinks the Protestant dogmatism dead. I do at least defend the Catholic theory because it can be defended. The Puritans would presumably be defending the Puritan theory--if it could be defended. The point is that it is dead for them as much as for us. It is not merely that Mr. Noyes demands the disappearance of a disfigurement; it is that Mr. Douglas says it cannot be a disfigurement because it has already disappeared. Now the Thomist philosophy, on which Dante based his poetry has not disappeared. It is not a question of faith but of fact; anybody who knows Paris or Oxford, or the worlds where such things are discussed, will tell you that it has not disappeared. All sorts of people, including those who do not believe in it, refer to it and argue against it on equal terms.

I do not believe, for a fact, that modern men so discuss the seventeenth century sectarianism. Had I the privilege of passing a few days with Mr. Douglas and his young lions of the DAILY EXPRESS, I doubt not that we should discuss and differ about many things. But I do rather doubt whether Mr. Douglas would every now and again cry out, as with a crow of pure delight "Oh, I must read you this charming little bit from Calvin." I do rather doubt whether his young journalists are joyously capping each other's quotations from Toplady's sermons on Calvinism. But eager young men do still quote Aquinas, just as they still quote Aristotle. I have heard them at it. And certain ideas are flying about, even in the original prose of St. Thomas, as well as in the poetry of Dante--or, for that matter, of Donne.

The case of Bunyan is really the opposite of the case of Dante. In Dante the abstract theory still illuminates the poetry; the ideas enlighten even where the images are dark. In Bunyan it is the human facts and figures that are bright; while the spiritual background is not only dark in spirit, but blackened by time and change. Of course it is true enough that in Dante the mere images are immensely imaginative. It is also true that in one sense some of them are obsolete; in the sense that the incidents are obsolete and the personal judgment merely personal. Nobody will ever forget how there came through the infernal twilight the figure of that insolent troubadour, carrying his own head aloft in his hand like a lantern to light his way. Everybody knows that such an image is poetically true to certain terrible truths about the unnatural violence of intellectual pride. But as to whether anybody has any business to say that Bertrand de Born is damned, the obvious answer is No. Dante knew no more about it than I do: only he cared more about it; and his personal quarrel is an obsolete quarrel. But that sort of thing is not Dante's theology, let alone Catholic theology.

In a word; so far from his theology being obsolete, it would be much truer to say that everything is obsolete except his theology. That he did not happen to like a particular Southern gentleman is obsolete; but that was at most a private fancy, in demonology rather than theology. We come to theology when we come to theism. And if anybody will read the passage in which Dante grapples with the gigantic problem of describing the Beatific Vision, he will find it is uplifted into another world of ideas from the successful entry to the Golden City at the end of the Pilgrim's Progress. It is a Thought; which a thinker, especially a genuine freethinker, is always free to go on thinking. The images of Dante are not to be worshipped, any more than any other images. But there is an idea behind all images; and it is before that, in the last lines of the Paradiso, that the spirit of the poet seems first to soar like an eagle and then to fall like a stone.

There is nothing in this comparison that reflects on the genius and genuineness of Bunyan in his own line or class; but it does serve to put him in his own class. I think there was something to be said for the vigorous denunciation of Mr. Noyes; but no such denunciation is involved in this distinction. On the contrary, it would be easy to draw the same distinction between two men both at the very top of all literary achievement. It would be true to say, I think, that those who most enjoy reading Homer care more about an eternal humanity than an ephemeral mythology. The reader of Homer cares more about men than about gods. So, as far as one can guess, does Homer. It is true that if those curious and capricious Olympians did between them make up a religion, it is now a dead religion. It is the human Hector who so died that he will never die. But we should remonstrate with a critic who, after successfully proving this about Homer, should go on to prove it about Plato. We should protest if he said that the only interest of the Platonic Dialogues to-day is in their playful asides and very lively local colour, in the gay and graceful picture of Greek life; but that nobody troubles nowadays about the obsolete philosophy of Plato. We should point out that there is no truth in the comparison; and that if anything the case is all the other way. Plato's philosophy will be important as long as there is philosophy; and Dante's religion will be important as long as there is religion. Above all it will be important as long as there is that lucid and serene sort of religion that is most in touch with philosophy. Nobody will say that the theology of the Baptist tinker is in that sense serene or even lucid; on many points it necessarily remains obscure. The reason is that such religion does not do what philosophy does; it does not begin at the beginning. In the matter of mere chronological order, it is true that the pilgrimage of Dante and that of Bunyan both end in the Celestial City. But it is in a very different sense that the pilgrimage of Bunyan begins in the City of Destruction. The mind of Dante, like that of his master St. Thomas, really begins as well as ends in the City of Creation. It begins as well as ends in the burning focus in which all things began. He sees his series from the right end, though he then begins it at the wrong end. But it is the whole point of a personal work like THE PILGRIM'S PROGRESS that it does begin with a man's own private sins and private panic about them. This intense individualism gives it great force; but it cannot in the nature of things give it great breadth and range. Heaven is haven; but the wanderer has not many other thoughts about it except that it is haven. It is typical of the two methods, each of them very real in its way, that Dante could write a whole volume, one-third of his gigantic epic, describing the things of Heaven; whereas in the case of Bunyan, as the gates of Heaven open the book itself closes.

Published on August 30, 2014 22:30

August 29, 2014

Many Martyrs Today: Three Special Women and Several Brave Men

There are really two events to remember today. One is the execution of six Catholics--one laywoman, four laymen and one priest--in London as part of the English government's reaction to the attempted invasion of England by the Spanish Armada. The other is the memorial of three female English Catholic martyrs, who were canonized among the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales in 1970, but have this special day all to themselves on the liturgical calendar of the Dioceses of England and Wales.

St. Margaret Clitheroe and St. Anne Line share the date of St. Margaret Ward's execution on August 30, 1588--she was part of a second group of martyrs after the failure of the Spanish Armada. She is a virgin martyr: she helped Father William Watson escape from Bridewell Prison. She visited him often enough that the jailer finally allowed her to enter without searching her, so she was able to smuggle in a rope. Father Watson injured himself unfortunately while escaping and was unable to retrieve the rope. Margaret found John Roche to help the injured priest once out of prison and both she and John were arrested; John because he had exchanged clothing with the priest and Margaret because the jailer figured out that she was the last person to visit Father Watson before he escaped. She was held in chains, hung up her hands and scourged as the authorities attempted to force her to tell them where Father Watson went after escaping Bridewell prison. She refused, even though she acknowledged that she helped him. Offered a pardon for attending Church of England services, she again refused. The torture inflicted upon her left her partially paralyzed and she had to be carried to Tyburn for hanging.

Also martyred that day were Blessed John Roche (who had assisted Margaret Ward in the escape of Father William Watson), three other laymen who had assisted priests, Blesseds Richard Lloyd, Richard Martin, and Edward Shelley, and one priest, Blessed Richard Leigh. The regime was certainly sending a message about laity who assisted Catholic priests.

The article for Blessed Richard Leigh from the Catholic Encyclopedia offers some details about him and the other laymen executed that day:

English martyr, born in Cambridgeshire about 1561; died at Tyburn, 30 August, 1588. Ordained priest at Rome in February, 1586-7, he came on the mission the same year, was arrested in London, and banished. Returning he was committed to the Tower in June 1588, and was condemned at the Old Bailey for being a priest. With him suffered four laymen and a lady . . . Edward Shelley of Warminghurst, Sussex, and East Smithfield, London (son of Edward Shelley, of Warminghurst, a Master of the Household of the sovereign, and the settlor in "Shelley's case", and Joan, daughter of Paul Eden, of Penshurst, Kent), aged 50 or 60, who was already in the Clink for his religion in April, 1584 was condemned for keeping a book called "My Lord Leicester's Commonwealth" and for having assisted the [Blessed] William Dean [who had been executed on August 28, 1588]. He was apparently uncle by marriage to Benjamin Norton, afterwards one of the seven vicars of Dr. Richard Smith. Richard Martin, of Shropshire, was condemned for being in the company of the Ven. Robert Morton and paying sixpence for his supper. Richard Lloyd, better known as Flower (alias Fludd, alias Graye), a native of the Diocese of Bangor (Wales), aged about 21, younger brother of Father Owen Lloyd was condemned for entertaining a priest named William Horner, alias Forrest. John Roche (alias Neele), an Irish serving-man, and Margaret Ward, gentlewoman of Cheshire, were condemned for having assisted a priest named William Watson to escape from Bridewell.

St. Margaret Clitherow and St. Anne Line also suffered martyrdom because they protected priests from discovery during England's recusant era. May these three brave Catholic women martyrs--and all the brave men who suffered this day in 1588-- inspire us!

St. Margaret Clitheroe and St. Anne Line share the date of St. Margaret Ward's execution on August 30, 1588--she was part of a second group of martyrs after the failure of the Spanish Armada. She is a virgin martyr: she helped Father William Watson escape from Bridewell Prison. She visited him often enough that the jailer finally allowed her to enter without searching her, so she was able to smuggle in a rope. Father Watson injured himself unfortunately while escaping and was unable to retrieve the rope. Margaret found John Roche to help the injured priest once out of prison and both she and John were arrested; John because he had exchanged clothing with the priest and Margaret because the jailer figured out that she was the last person to visit Father Watson before he escaped. She was held in chains, hung up her hands and scourged as the authorities attempted to force her to tell them where Father Watson went after escaping Bridewell prison. She refused, even though she acknowledged that she helped him. Offered a pardon for attending Church of England services, she again refused. The torture inflicted upon her left her partially paralyzed and she had to be carried to Tyburn for hanging.

Also martyred that day were Blessed John Roche (who had assisted Margaret Ward in the escape of Father William Watson), three other laymen who had assisted priests, Blesseds Richard Lloyd, Richard Martin, and Edward Shelley, and one priest, Blessed Richard Leigh. The regime was certainly sending a message about laity who assisted Catholic priests.

The article for Blessed Richard Leigh from the Catholic Encyclopedia offers some details about him and the other laymen executed that day:

English martyr, born in Cambridgeshire about 1561; died at Tyburn, 30 August, 1588. Ordained priest at Rome in February, 1586-7, he came on the mission the same year, was arrested in London, and banished. Returning he was committed to the Tower in June 1588, and was condemned at the Old Bailey for being a priest. With him suffered four laymen and a lady . . . Edward Shelley of Warminghurst, Sussex, and East Smithfield, London (son of Edward Shelley, of Warminghurst, a Master of the Household of the sovereign, and the settlor in "Shelley's case", and Joan, daughter of Paul Eden, of Penshurst, Kent), aged 50 or 60, who was already in the Clink for his religion in April, 1584 was condemned for keeping a book called "My Lord Leicester's Commonwealth" and for having assisted the [Blessed] William Dean [who had been executed on August 28, 1588]. He was apparently uncle by marriage to Benjamin Norton, afterwards one of the seven vicars of Dr. Richard Smith. Richard Martin, of Shropshire, was condemned for being in the company of the Ven. Robert Morton and paying sixpence for his supper. Richard Lloyd, better known as Flower (alias Fludd, alias Graye), a native of the Diocese of Bangor (Wales), aged about 21, younger brother of Father Owen Lloyd was condemned for entertaining a priest named William Horner, alias Forrest. John Roche (alias Neele), an Irish serving-man, and Margaret Ward, gentlewoman of Cheshire, were condemned for having assisted a priest named William Watson to escape from Bridewell.

St. Margaret Clitherow and St. Anne Line also suffered martyrdom because they protected priests from discovery during England's recusant era. May these three brave Catholic women martyrs--and all the brave men who suffered this day in 1588-- inspire us!

Published on August 29, 2014 23:00

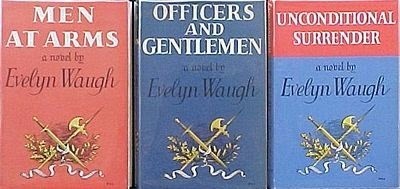

Waugh's Interviews

(Waugh's Sword of Honor trilogy)

(Waugh's Sword of Honor trilogy)Francis Philips writes about Evelyn Waugh in The Catholic Herald, referring to a televised interview he gave in 1960:

Then I came across Fr Tim Finigan’s blog last year about Evelyn Waugh’s “Face to Face” interview with John Freeman in 1960. Never having watched this encounter before, I found it very revealing of the man who could write the mordant satire referred to above. Waugh smiled from time to time as he (briefly) explained a point, but only with his lips; his eyes remained cold, watchful, wary – indicative, as Freeman must have realised, of a gifted, complex and deeply private man who understood his own nature and failings and felt not the slightest desire to share this knowledge with the BBC.

Freeman was a model of patient, self-effacing and sensitive enquiry; a disembodied voice focused on his subject and unvaryingly courteous, even though Waugh refused to expand on any tentative avenues of enquiry. Asked whether he missed the life of the city (Waugh was then living at Combe Flory House in Somerset), he replied “I live in the country as I like to be alone”, indicating that further questions in this line would not be approved. . . .

There were no revelations, confessions, psychologising or the kind of celebrity chumminess that has characterised interviews in a later age. When Freeman tried to probe him on his conversion, Waugh refused to be drawn; he had realised that “Catholicism was Christianity” at the age of 16, had ignored religion for the next decade and reprimanded Freeman for suggesting that his faith might have brought him comfort or solace: “It isn’t a lucky dip”, he replied, adding in an aside that was not picked up on, that it was “the essence”.

Waugh converted in 1930. In 1949 he explained in an interview that his conversion followed his realization that life was “unintelligible and unendurable without God.” Doubtless, if Freeman had quoted this on “Face to Face” Waugh would have declined to expand. But it indicates much about the intellectual clarity and emotional intensity with which he looked at life.

Julian Jebb interviewed Evelyn Waugh for The Paris Review in 1962, and seemed to have about the same luck, although there are some gems:

INTERVIEWERIt is evident that you reverence the authority of established institutions—the Catholic Church and the army. Would you agree that on one level both Brideshead Revisited and the army trilogy were celebrations of this reverence? WAUGHNo, certainly not. I reverence the Catholic Church because it is true, not because it is established or an institution. Men at Arms was a kind of uncelebration, a history of Guy Crouchback's disillusion with the army. Guy has old-fashioned ideas of honor and illusions of chivalry; we see these being used up and destroyed by his encounters with the realities of army life. INTERVIEWERWould you say that there was any direct moral to the army trilogy? WAUGHYes, I imply that there is a moral purpose, a chance of salvation, in every human life. Do you know the old Protestant hymn which goes: “Once to every man and nation / Comes the moment to decide”? Guy is offered this chance by making himself responsible for the upbringing of Trimmer's child, to see that he is not brought up by his dissolute mother. He is essentially an unselfish character. And this exchange on characters in fiction: INTERVIEWERE. M. Forster has spoken of “flat characters” and “round characters”; if you recognize this distinction, would you agree that you created no “round” characters until A Handful of Dust? WAUGHAll fictional characters are flat. A writer can give an illusion of depth by giving an apparently stereoscopic view of a character—seeing him from two vantage points; all a writer can do is give more or less information about a character, not information of a different order. . . .But look, I think that your questions are dealing too much with the creation of character and not enough with the technique of writing. I regard writing not as investigation of character, but as an exercise in the use of language, and with this I am obsessed. I have no technical psychological interest. It is drama, speech, and events that interest me. INTERVIEWERDoes this mean that you continually refine and experiment? WAUGHExperiment? God forbid! Look at the results of experiment in the case of a writer like Joyce. He started off writing very well, then you can watch him going mad with vanity. He ends up a lunatic.

Published on August 29, 2014 22:30

August 28, 2014

An Obscure Masterpiece

Willard Spiegelman, Hughes Professor of English at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, describes Caravaggio's masterpiece, "The Taking of Christ" for The Wall Street Journal:

Seven figures, one barely noticeable, are tightly bound within the confines of a small space. On the left, John the Evangelist turns his back on the others, his hands lifted in shock, surprise or exclamation. Next to him, Christ is dressed in red and blue garments. His eyes, hooded to the point of invisibility, look down, and he clasps his hands in resignation. Judas, having just kissed the Savior, grips Jesus with his left hand. Both men—typical of Caravaggio—have dirty nails. Their brows are furrowed. John, Jesus and Judas look like parts of one person, their three heads all in a line, with John's seemingly joined Siamese-fashion to Christ's, and Judas's mouth having just separated from the man he has sold to the enemy.

Dead center in the picture is the arresting officer, of whose face we can see only a nose and the outline of an upper lip. Otherwise, he is a study in metal. His left arm clasps Christ and his hand extends from the shiny, steel-colored armor of his arm and breastplate. His helmet completes the image. He is all exoskeleton, barely a man at all. The painter has offered an allegory of the way the State—hard, metallic and unyielding—comes to overwhelm compliant, beleaguered, passive humanity. Beside the main officer another, older, soldier reveals more flesh—nose and moustache—but in neither of these figures can we see eyes. In the rear we can make out only the outline of yet one more soldier.

This leaves us with the most mysterious figure of all, neither Roman nor Jew. Dark-headed, handsome, with eyes fully revealed and looking intently at the scene in front of him, this man holds in his right hand a lantern, which offers illumination from behind and to the right of Jesus and Judas. Who is he? The consensus among the experts is that Caravaggio has produced a self-portrait.

This is one of "Ireland's Favorite Paintings" at the National Gallery of Ireland, which displays it on indefinite loan from the Irish Jesuits.

Image Credit: Public Domain.

Published on August 28, 2014 23:00

August 27, 2014

O Bone Jesu: St. Edmund Arrowsmith, SJ

O bone Jesu, miserere nobis, quia tu creasti nos, tu redemisti nos sanguine tuo praetiosissimo.

Today's English Catholic Martyr was raised in a recusant family and suffered much for his Catholic faith and his priesthood. Executed on the vigil of the Feast of the Beheading of St. John the Baptist, it is interesting to note that his defense of holy matrimony brought about his final arrest. Like St. John the Baptist, speaking to Herod, he told one of his flock that his marriage was not valid and was betrayed.

According to this site, Catholic Online:

St. Edmund Arrowsmith (1585 - 1628) Edmund was the son of Robert Arrowsmith, a farmer, and was born at Haydock, England. He was baptized Brian, but always used his Confirmation name of Edmund. The family was constantly harrassed for its adherence to Catholicism, and in 1605 Edmund left England and went to Douai to study for the priesthood. He was ordained in 1612 and sent on the English mission the following year. He ministered to the Catholics of Lancashire without incident until about 1622, when he was arrested and questioned by the Protestant bishop of Chester. He was released when King James ordered all arrested priests be freed, joined the Jesuits in 1624, and in 1628 was arrested when betrayed by a young man he had censored for an incestuous marriage. He was convicted of being a Catholic priest, sentenced to death, and hanged, drawn, and quartered at Lancaster on August 28th. He was canonized as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales by Pope Paul VI in 1970. His feast day is August 28th.

He recited the prayer O bone Jesu (Oh, Good Jesus, have mercy on us; because you have created us, you have redeemed us through your most Precious Blood), on his way to execution.

Published on August 27, 2014 23:00