Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 230

July 13, 2014

Shakespeare's Friars

Ken Colston writes about Shakespeare's Franciscan Friars in Homiletic & Pastoral Review:

Like the present Holy Father, William Shakespeare channeled an “inner Franciscan.” Despite Elizabethan persecution of Roman Catholics, the dramatic genius—who, according to Harold Bloom, invented the human personality—gave several pivotal roles to characters from an order that had virtually disappeared from England several generations earlier during Henry VIII’s first dissolution of the monasteries. These characters, while not leading protagonists, were much more than bit parts. Shakespeare took a political risk in overtly portraying them in their traditional garb onstage, where the royal censor, the Master of the Revels, might well have objected, demanded their removal, and even prosecuted the playwright’s company. What reasons, dramaturgical, political, or religious, might have led Shakespeare to take such a risk to his livelihood and person?

Using the example of Friar Laurence from Romeo and Juliet, Colston states:

Shakespeare may have had not just traditional Catholic leanings, but also personal memories behind his portrayal of Friar Laurence. Heinrich Mutschmann and Karl Wentersdorf suggest that Fr. Frist, the Roman Catholic priest of Temple Grafton (the likely venue of Shakespeare’s marriage to Anne Hathaway), was the biographical model for Friar Laurence. Frist was also interested in medicine and healing, and the famously rushed marriage that he would have performed for the Warwickshire couple was by license rather than by the usual banns. A second personal Catholic association may also loom in Shakespeare’s memory in forming the Church regular. In Shakespeare’s home county of Warwickshire, a religious community, called the Guild of St. Anne, flourished prior to the Reformation. Its registry contains 16 brothers and sisters named Shakespeare, one of which was an abbess, Isabella, who bears the name of the Poor Clare heroine of Measure for Measure. Isabella Shakespeare may have been an aunt of William, the poet.

After discussing other Franciscan friars in Shakespeare's plays Much Ado About Nothing, Measure for Measure, and Two Gentlemen of Verona, Colston asks a couple of questions and draws some conclusions:

What can we conclude from Shakespeare’s use of these 10 followers of the via Franciscana? First, he departs from the satirical tradition, both Catholic and Reformed, with universally sympathetic portrayals of Franciscans. He associates the Poor Clares with austerity, the friars with prudence and cunning. In fact, the friars operate somewhat in the reputed manner of Jesuits with their shadowy access to powerful aristocratic families, their confessional exactitude, and their deceptive tactics. Second, in all three plays in which they have major roles, they take extraordinary means to move couples, and indeed, the entire small world of the drama, toward holy matrimony, which is seen as a means of reconciling conflicts, both between families and within the hearts of characters. Marriage resolves social enmities and the inner war between flesh and spirit. Third, the friars are instruments of moderation, wisdom, and peace; they know canon law with respect to marriage and confession; they move far more freely onstage than they did in Elizabethan and Jacobean England, where they were banned, persecuted, and pursued. Fourth, since they are the only order of regulars specifically depicted in the Shakespearean canon, and, except for the churchmen in the history plays, the only identifiable Roman Catholic characters, they are a strong clue to Shakespeare’s friendly feelings toward that bane of Elizabethan-Jacobean political rule, Roman Catholicism. He is unique among playwrights of the time in presenting in a positive light, and in the daylight exposure of a universally recognized habit, the dread enemy of the realm, the whore of Babylon, in a dangerous, even suspect, public space.

So, why, then, Franciscans, and why such positive roles, on a stage where Catholic clergy would be so suspect, even threatening to the court? First, dramaturgically, a Franciscan would be quickly, easily, and inexpensively identified by his simple habit. Second, popular respect for Franciscans as close followers of the evangelical counsels of poverty, chastity, and obedience must have persisted in the popular imagination despite the centuries-old anti-fraternal tradition—obedience to moral authority, not power, being the emphasis. Third, as an order quasi-independent of the hierarchy, the Franciscans would not have been necessarily associated with the hypocrisy, corruption, venality, and thirst for power of the papacy feared and hated by the English court. Fourth, Shakespeare, the consummate dramatist, sensed that the serious, even sacral theme of marriage as an instrument of peace could be reinforced by a highly visible “objective correlative,” to use T.S. Eliot’s term, of characters in religious habit independent enough of the hierarchical Church to not threaten Protestants and, yet, also representative of the best in traditional Catholicism. Dominicans were also associated with Spain and the Inquisition; Jesuits, also having a Spanish founder, also implicated in treason; the other orders, too obscure. While Franciscans come ready made in Shakespeare’s source material, he probably saw them immediately as robed crowd pleasers, even as Cardinal Bergoglio intuited their popularity on the anti-clerical world stage.

Read the rest here.

Published on July 13, 2014 22:30

July 12, 2014

Echoes of the Dissolution of Monasteries--in Philadelphia

Father Zuhlsdorf posted a link to a story from The Daily Mail of photos taken in Philadelphia of partially demolished, abandoned Catholic churches. As I scrolled through the story, I kept thinking of the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII, which left so many beautiful chapels and churches in ruins.

From the remains of these churches in Philadelphia, you can see that they were beautiful sanctuaries of worship; with wonderful architectural bones still standing, there are still glimmers of the art that filled the niches and the side chapels. Parishioners worshipped there, went to Confession on Saturday evening, brought their babies to be baptized, their sons and daughters to be married, their fathers and mothers to be buried. They paid their tithe and left bequests--you can imagine the life of the parish from the life of your parish today.

The parish priests said their first Masses, prepared First Holy Communion and Confirmation classes for the Sacraments, instructed pre-Cana couples--and then sadly, all of them had to see the church stripped, closed, and even partially demolished. The people in the parish may have fought against the closure, raised funds, held raffles, applied for historic building protections, petitioned The Holy See--whatever their efforts, the church was still closed and they went to another parish or parishes.

At the end of the article, the photographer, Matthew Christopher, explained his fascination with these ruined churches:

Mr Christopher's fascination with abandoned spaces started when he was a child. He enjoyed looking at artwork set in buildings that have since decayed.

His fascination with churches stemmed from this genre of art, as many painters in the late 1700s and early 1800s would paint churches and abbeys, closed under Henry VIII.

Later this year a book named 'Abandoned America: The Age of Consequence' will be released documenting some of the most spectacular ruins, including Mr Christopher's church pictures.

You can see more of his spectacular photographs on his website, Abandoned America , and its related Facebook page .

The common folk protested the suppression of the monasteries in England with the Pilgrimage of Grace, but as Father Zuhlsdorf comments, we don't need an uprising--we Catholic laity have to think about the glories of the legacy we've received and help it survive and thrive:

The point is that parishes have bills to pay and parishes need priests. If you don’t pay the bills and if you don’t provide solid vocations to the priesthood through prayer, promotion and sacrifice, this is what happens. That means that you, dear readers, must with joy support interest in a vocation to the priesthood in your families. It also means that you should also provide feedback and support for formation for priests. Lousy priests can equate to everything from emptying pews to emptying coffers. Be engaged.

So, photos like these can also underscore the creative destruction that takes place from time to time everywhere. Sometimes things break down. Then something new is rebuilt.

But none of what you want and need as Catholics is free. You can and must (it is a precept of the Church) contribute by your time, your talents and your treasure.

My husband and I have the great good fortune to live and have lived all our lives in a diocese that has grown with new churches and parishes being built in its major metropolitan area, but certainly rural churches have had to close and consolidate the Catholic communities because of changes in population. The parish church I grew up in was demolished to make way for a highway expansion--and that was sorrowful to me even though it wasn't that beautiful to my taste. I was confirmed there and both my sister and I were married there. In other words, it can't always be helped--but when it can, it's up to the Catholic laity to be faithful and fruitful!

When we attend Mass today in the parish church of St. Anthony of Padua, so lovingly and carefully restored several years ago, and so lovingly and carefully built many years ago, I'll look around gratefully for the survival of its beauty, pray for the benefactors, living and dead. Perhaps you can do the same thing today in your parish church. Bon dimanche--Good Sunday!

Attribution: Photograph by Mike Peel (http://www.mikepeel.net/).

Published on July 12, 2014 23:00

Book Review: Sister Queens--Katherine and Juana

I found a bargain book at Barnes & Noble on the 4th of July: Sister Queens: The Noble, Tragic Lives of Katherine of Aragon and Juana, Queen of Castile by Julia Fox. According to the publisher:

I found a bargain book at Barnes & Noble on the 4th of July: Sister Queens: The Noble, Tragic Lives of Katherine of Aragon and Juana, Queen of Castile by Julia Fox. According to the publisher:The history books have cast Katherine of Aragon, the first queen of King Henry VIII of England, as the ultimate symbol of the Betrayed Woman, cruelly tossed aside in favor of her husband’s seductive mistress, Anne Boleyn. Katherine’s sister, Juana of Castile, wife of Philip of Burgundy and mother of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, is portrayed as “Juana the Mad,” whose erratic behavior included keeping her beloved late husband’s coffin beside her for years. But historian Julia Fox, whose previous work painted an unprecedented portrait of Jane Boleyn, Anne’s sister (sic) [she was her sister-in-law, married to Anne's brother George], offers deeper insight in this first dual biography of Katherine and Juana, the daughters of Spain’s Ferdinand and Isabella, whose family ties remained strong despite their separation. Looking through the lens of their Spanish origins, Fox reveals these queens as flesh-and-blood women—equipped with character, intelligence, and conviction—who are worthy historical figures in their own right.

When they were young, Juana’s and Katherine’s futures appeared promising. They had secured politically advantageous marriages, but their dreams of love and power quickly dissolved, and the unions for which they’d spent their whole lives preparing were fraught with duplicity and betrayal. Juana, the elder sister, unexpectedly became Spain’s sovereign, but her authority was continually usurped, first by her husband and later by her son. Katherine, a young widow after the death of Prince Arthur of Wales, soon remarried his doting brother Henry and later became a key figure in a drama that altered England’s religious landscape.

Ousted from the positions of power and influence they had been groomed for and separated from their children, Katherine and Juana each turned to their rich and abiding faith and deep personal belief in their family’s dynastic legacy to cope with their enduring hardships. Sister Queens is a gripping tale of love, duty, and sacrifice—a remarkable reflection on the conflict between ambition and loyalty during an age when the greatest sin, it seems, was to have been born a woman.

This book was published around the same time as Giles Tremlett's Catherine of Aragon: Henry's Spanish Queen, which I reviewed here. Both authors used the Spanish background of Katherine of Aragon to place her life as Henry VIII's queen and wife in context, and the addition of her sister's life and career as Queen of Castile adds greater depth to the story of princesses and queens, as well as princes and kings in the sixteenth century.

One theme that emerges is the impact of death in royal dynastic plans. All the marriages Ferdinand and Isabella--and Henry VII--so carefully planned and arranged to consolidate and maintain power came to naught because of "untimely" deaths. Fox highlights the devastating blows of Juan, the Prince of Asturias and Arthur, the Prince of Wales in Spain and England to the Catholic Monarch's plans and Henry VII's hopes--and then the effects on Katherine and Juana's lives.

While covering the familiar ground of the breakdown of Henry VIII's and Katherine's marriage, Fox clearly emphasizes Katherine's steadfast faithfulness to her marriage and to her love for Henry. Fox notes that Katherine's influence on Henry, so strong early in their marriage, declined as Thomas Wolsey's influence increased. Like Tremlett, Fox also stresses Katherine's concern for the Catholic faith in England as she saw Henry not only attacking the Church hierarchy to get his way on the matter of their marriage but also allowing Lutheran ideas about the Christian faith to gain a foothold in England. As a daughter of the Catholic Majesties of Spain and the wife of the Defender of the Faith, these assaults on the True Faith and then the martyrdoms of the Carthusians, Bishop John Fisher, and Thomas More, troubled Katherine greatly.

Juxtaposed to Katherine's troubles, Juana's situation is much worse throughout the book as she is misused by her husband, her father, and her son--and even her grandson; denied her rights to reign as the Queen of Castile (Spain's Cortes did not have the same concerns with a female ruler that Henry VIII had--nor any Salic law like France had) by all three, and imprisoned, neglected, abused, and consistently lied to by the latter two. Ferdinand of Aragon was a true Machiavellian; Charles V has sunk lower than before in my estimation after reading about his treatment of his mother, and Philip II learned how to treat the Princess of Eboli from the example of his grandmother's captivity. Fox examines Juana's mental state throughout the book--she did use rather drastic methods to try to achieve what she wanted: fasting, neglecting her health, refusing to sleep or staying in bed all day, refusing to attend Mass or go to confession. The latter two refusals concerned the family greatly especially as she grew older (it's not clear whether Fox means that Juana refused to attend daily Mass or Sunday Mass); yet the family consistently ignored the physical and mental abuse meted out to her by her attendants.

After both sisters have died--and Juana lived a long time in her captivity--Fox turns to the hoped-for triumph of the alliance between England and Spain when Philip II, Juana's great-grandson and Katherine's great nephew, married Mary I, Juana's great niece and Katherine's daughter. But that marriage was not fated to be fruitful. Although Mary manages to restart Catholicism in England, her too brief reign without a male heir to succeed her meant that Elizabeth came to the throne--and the rest, as they say, is history.

There were a few quibbles as I read the book--at one point Fox seems to imply that to be Catholic is to be narrow-minded, when referring to Isabella of Castile's library, saying it was more eclectic than to be expected from a "Catholic Monarch"--forgetting that Catholic/catholic means universal and that Christian humanism was a wide-ranging search for truth and knowledge. It was also surprising that Fox does not mention the second Henry, the son Katherine bore in 1514, who lived long enough to be named the Duke of Cornwall during her examination of Henry's citation of Leviticus to support his qualms of conscience about the validity of their marriage.

Fox does not impute emotions to the personages in this book as much as she did in her previous book about Jane Boleyn, Anne Boleyn's sister-in-law (whom the publishers mis-identify in their blurb above--thus my "sic"), which was too filled with would haves, could haves and might haves. She has much more content and many more resources from correspondence and reports for these subjects including letters, official records, and ambassador's reports, so she does not have to be so inventive. Fox does have a good eye and depicts major set pieces like Katherine and Arthur's wedding or Katherine and Henry's coronation with great detail to help the reader imagine them. I would recommend Sister Queens for anyone wanting to know more about not only the familiar story of Katherine of Aragon's marriage to Henry VIII, but also interested in the diplomatic tangle of royalty in the sixteenth century, as the houses of Asturias, Tudor, Valois, and Burgundy struggled for power--with death always around the corner.

Published on July 12, 2014 22:30

July 11, 2014

St. John Jones in "The Catholic Herald"

The Catholic Herald features St John Jones, one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales, in their latest issue. And he was from Wales, a Franciscan Friar who began his vocation during the reign of Mary I at Greenwich, went to the Continent and returned as a missionary priest:

John arrived in London towards the end of 1592 and laboured in different parts of the country. His brother Franciscans elected him their minister provincial.

In 1596 a spy told the priest-catcher Richard Topcliffe that John had visited two Catholics and celebrated Mass in their home. Although it was later revealed that the two Catholics were in prison at the time the Mass was alleged to have been celebrated, John was arrested, scourged and tortured. He was then imprisoned for two years.

On July 3 1598, John was tried on the charge of “going over the seas in the first year of Her Majesty’s reign [1558] and there being made a priest by the authority from Rome and then returning to England contrary to statute”. He was convicted of high treason and sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered.

His execution was delayed by an hour because his executioner forgot to bring the rope. He used the spare time to preach to the crowd and answer their questions. He was executed on what is now the Old Kent Road in south-east London. His dismembered body parts were fixed on top of poles on roads leading to Newington and Lambeth.

While he was imprisoned for two years, St. John Jones was able to help sustain the faith of St. John Rigby, a layman who had, while representing the daughter of his employer, confessed his own Catholic faith to authorities. Rigby was executed at St. Thomas Waterings, on the Old Kent Road (on the way to Canterbury) on June 21, 1600. The Franciscans of the Province in England remember several other martyrs on this date: St. John Wall, Blessed Thomas Bullaker, Blessed Henry Heath, Blessed Arthur Bell, Blessed John Woodcock, and Blessed Charles Meehan-Mahoney.

Image credit: Used by permission of the webmaster: A stained glass depiction of Franciscan Saints above the high altar [at the former Chilworth Friary of the Holy Ghost]: at the extreme left is Blessed John Jones, at the extreme right Blessed John Wall (also known as Joachim of St Anne), both of whom are now canonised Saints.

Published on July 11, 2014 22:30

July 10, 2014

Seven Year Anniversary of Summorum Pontificum

Father Alexander Lucie-Smith writes about the seventh anniversary of Pope Benedict XVI's motu proprio Summorum Pontificum, in The Catholic Herald:

My father was a huge admirer of the Latin Mass of his youth: he used to say that its great advantage was that wherever you went in the world, the Mass was the same, in Latin, in the universal language, and thus accessible to all. That is a point of view I have not heard expressed for many a year. But there is something in it. The EF, I discovered as I learned it, is very formal: every gesture and every word has its place, and there is no room for variation, which is a good thing. Every Mass, in theory, is exactly like every other Mass. Why is this good? It is good because it reminds us that the Church is Catholic, universal. Of course we all have our particularities, but we need to remember that the universal aspect ought to take precedence. Why? Because the revelation of Jesus Christ is something that makes sense across space and time. It is valid for all times and places. Therefore it seems to me that the Mass ought to be celebrated in a way that emphasises the unicity of revelation and the unity of the human family. We should not be celebrating diversity, but identity; not celebrating difference, but the common heritage we all share.

I think this is one thing that has changed in the last seven years, and this is one of the looked for fruits of Summorum Pontificum: the EF has ‘reminded’ the OF of the ‘catholicity’ of the Church.

If the horizontal aspect is important, so is the vertical. The EF is clearly old, indeed very old. Codified at Trent, it is much older than Trent, going back to the time of Gregory the Great; in his time it was already old. Moreover, the OF is not ‘new’, in the sense that it is clearly in continuity with the ‘old’ Mass; the ‘new’ Mass is not ex nihilo. So, whether you celebrate one Mass or the other, or both from time to time, you are standing in a millennial tradition, going right back to the time before Pope Gregory. The ancient nature of the Church’s tradition is not something you heard much about when I was growing up, when all the talk was of the importance of ‘relevance’. So it is good that we should feel the worth and weight of tradition, and antiquity. These are useful counter-cultural correctives in this culture of ours, a culture which will one day be in the dustbin of history while the Mass, ever old, ever new, will continue.

So this is the main thing that we owe to Benedict’s motu proprio: it has put us more in touch with our history and with our universality.

As you may know from reading this blog, my husband and I have grown devoted to the Extraordinary Form of the Latin Liturgy of the Roman Rite, attending Sunday Mass at St. Anthony of Padua (my husband took the picture above on Palm Sunday this year) here in Wichita and seeking it out when we travel--especially at St. Eugene-Ste. Cecile in Paris. I echo Father Lucie-Smith's statement about being in touch with "our history", our Catholic past. To me, the historical connection has been to the English Catholic martyrs, since the missionary priests who had studied on the Continent came back to England, celebrating the Mass according to the Missal of Pope St. Pius V. They knew the glories of the rite in Rome, Paris, and throughout Europe--in their native land they celebrated Low Mass secretly, furtively, and faithfully. It's the form of Latin Liturgy of the Roman Rite that Blessed John Henry Newman learned to celebrate when he studied for the Catholic priesthood in Rome and then celebrated at the Oratory.

We are very thankful to Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, to our local Ordinary, Bishop Carl Kemme, and the priests of our diocese who offer the Mass in the Extraordinary Form at St. Anthony and throughout the diocese--and to the master of ceremonies and the servers he's trained and the choir director and the choir members he directs to sing the parts of the Mass and the beautiful hymns.

Published on July 10, 2014 23:00

This a Job for an English Major!

When I majored in English Language and Literature and then went on to earn an M.A. in the same subject, the question often was--"What are you going to DO with those degrees?" or "How are you going to get a job?" The common argument for the "usefulness" of the Liberal Arts was that I was going to know how to think, how to do research, how to write, how to express ideas--to teach, to persuade, etc. Now I find out that I--were I a recent graduate--could help airlines apologize, according to this article in The Wall Street Journal, as "Carriers Deploy Software, English Majors to Tell Angry Fliers They're Sorry for Mistakes in Flight":

United Airlines, which had the highest rate of complaints filed at the DOT among major airlines the past three years, has a team of about 450 customer-care agents handling general issues and refunds. Add to that 400 people handing (sic) frequent-flier program issues and about 100 answering baggage-related letters and emails.

Delta Air Lines employs 150 people in Atlanta and Minneapolis to email answers to angry—and complimentary—customers. Many get letter-writing training and are experienced airport agents used to dealing directly with customers.

Airlines say they try to make responses conversational and personal. They aim to apologize and acknowledge the problem, providing more information about the particular situation after research, then offering some compensation as a goodwill gesture, such as some frequent-flier miles. Letters are signed by an employee, though many use pseudonyms.

Complaints are sorted by complexity and by the value of the customer—top-tier frequent fliers and big spenders get priority. A low-level customer may get 3,000 frequent-flier miles for a canceled flight, while a high-value customer who complains is soothed with 10,000 miles.

Agents research incidents to verify and provide explanations. Complaints also are tracked so airlines can peg frequent complainers trawling for extra miles or discounts.

Customer feedback is compiled into reports for top executives, and individual letters—complaint or compliment—do get forwarded to supervisors and employees, airlines say.

American Airlines uses a library of responses built over the years that agents can search and then customize. That allows for consistency and accuracy in responses. "We've gone completely away from corporate-speak to personally showing empathy," said John Romantic, American's managing director of service recovery.

The print article contains additional detail about Southwest Airlines, which employs 200 agents just to respond to customer complaints and compliments. "It's an entry-level job for college graduates. Southwest also employs proofreaders, often English majors."

My first job out of the graduate school as as a proofreader at an advertising agency.

As I was pursuing those degrees, however, my ideal was Blessed John Henry Newman's--that a liberal education was a good in itself, as knowledge is a good in itself, without needing application or usefulness to prove its worth. I'm certainly not sorry about that.

Published on July 10, 2014 22:30

July 9, 2014

"100 Years; 100 Legacies': More on WWI from the WSJ

The Wall Street Journal continues to explore the legacy of World War I, with an on-line examination of one hundred legacies of the Great War to End All Wars, including music and literature. Fiona Matthias looks at the classical music inspired by conflicting impulses of patriotism and sorrow:

The Wall Street Journal continues to explore the legacy of World War I, with an on-line examination of one hundred legacies of the Great War to End All Wars, including music and literature. Fiona Matthias looks at the classical music inspired by conflicting impulses of patriotism and sorrow:The emotional wounds of war as well as patriotism resonate through the music of many of the most influential composers of the early 20th century.

Edward Elgar’s work is infused with both sentiments, including “For the Fallen” (1915-17); “Carillon” (1914) and “Polonia” (1915), in honor of Belgium and Poland, respectively; and “The Fringes of the Fleet” (1917).

While Elgar, in his mid-50s when war broke out, was only able to respond in his music to the carnage taking place on the other side of the English Channel, there were others directly touched by it. . . .

The Great War, of course, claimed millions of lives, among them one of Britain’s most promising writers, George Butterworth, known for “The Banks of Green Willow,” which is now regarded by many as an anthem to unknown soldiers everywhere. A recipient of the Military Cross, Butterworth died at the age of 31 during the Battle of the Somme and his place of burial remains unknown.

The BBC Music Magazine has also been exploring the musical legacy of World War I, with its June issue dedicated to the composers of that era, including George Butterworth, and the July issue featuring a CD of Elgar's The Spirit of England.

Published on July 09, 2014 22:30

July 8, 2014

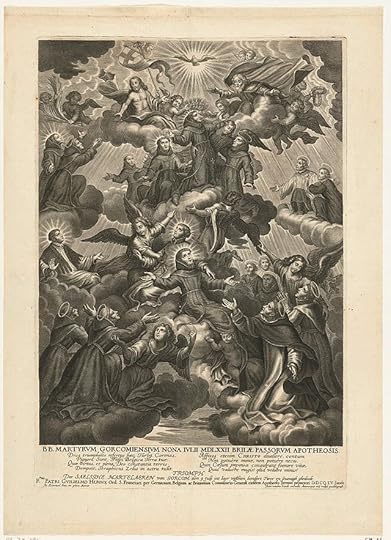

Franciscan Martyrs of Gorkum, South Holland

On Saturday, July 12, the Franciscans of England will celebrate several martyrs during the Recusant era and the Popish Plot crisis. Today, Franciscans (and Dominicans) in the Netherlands and Belgium remember the Gorkum martyrs, brutally tortured and executed by Calvinist pirates against the wishes of Prince William of Orange. From

Catholic Exchange

:

On Saturday, July 12, the Franciscans of England will celebrate several martyrs during the Recusant era and the Popish Plot crisis. Today, Franciscans (and Dominicans) in the Netherlands and Belgium remember the Gorkum martyrs, brutally tortured and executed by Calvinist pirates against the wishes of Prince William of Orange. From

Catholic Exchange

:On July 9, 1572, nineteen priests and religious were put to death by hanging at Briel, the Netherlands. They had been captured in Gorkum on June 26 by a band of Calvinist pirates called the Watergeuzen (sea-beggars) who were opposed to the Catholicism of the Spanish princes of the country.

During their imprisonment, the priests were tortured, subjected to countless indignities, and offered their freedom if they would deny the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist and the primacy of the pope. Despite a letter from Prince William of Orange ordering their release and protests from the magistrates of Gorkum, the men were thrown half-naked into the hold of a ship on July 6, and taken to Briel to be killed in the presence of a Protestant nobleman, Admiral Lumey, who was noted for his hatred of Catholicism. Their bodies, mutilated both before and after death, were callously thrown into a ditch.

The scene of the martyrdom soon became a place of pilgrimage. Accounts of several miracles, performed through the martyrs’ intercession and relics, were used for their beatification. Most of their relics are kept in the Franciscan church at Brussels to which they were secretly conveyed from Briel in 1616.

The 19 martyrs, canonized by Pope Pius IX on June 29, 1865, are:

1. Leonard van Veghel (born 1527), spokesman, secular priest, and since 1566 pastor of Gorkum2. Peter of Assche (born 1530), Franciscan lay brother3. Andrew Wouters (born 1542), secular priest, pastor of Heinenoord in the Hoeksche Waard4. Nicasius of Heeze (born 1522), Franciscan friar, theologian and priest5. Jerome of Weert (born 1522), Franciscan friar, priest, pastor in Gorcum6. Anthony of Hoornaar, Franciscan friar and priest7. Godfried van Duynen (born 1502), secular priest, former pastor in northern France8. Willehad of Denemarken (born 1482), Franciscan friar and priest9. James Lacobs (born 1541), Norbertine canon10.Francis of Roye (born 1549), Franciscan friar and priest11.John of Cologne, Dominican friar, pastor in Hoornaar near Gorkum12.Anthony of Weert (born 1523), Franciscan friar and priest13.Theodore of der Eem (born c. 1499–1502), Franciscan friar and priest, chaplain to a community of Franciscan Tertiary Sisters in Gorkum14.Cornelius of Wijk bij Duurstede (born 1548), Franciscan lay brother15.Adrian van Hilvarenbeek (born 1528), Norbertine canon and pastor in Monster, South Holland16.Godfried of Mervel, Vicar of Melveren,Sint-Truiden (born 1512), Franciscan priest, vicar of the friary in Gorkum17.Jan of Oisterwijk (born 1504), canon regular, a chaplain for the Beguinage in Gorkum18.Nicholas Poppel (born 1532), secular priest, chaplain in Gorkum19.Nicholas Pieck (born 1534), Franciscan friar, priest and theologian,Guardian of the friary in Gorkum, his native city

The church alluded to in the Catholic Exchange article is St. Nicholas Church in Brussels, not too far from the Grand Place. The martyrs' reliquary is a large rectangular case decorated with their images on the sides, and events of their arrest and martyrdom on the lid. The relics had been transferred originally to a nearby Franciscan friary which was suppressed during the French Revolution (1796), and then moved to St. Nicholas; the gilded bronze reliquary was created in 1870 for the relics.

Prince William the Silent might have ordered the Calvinist pirates to release the Catholic priests, demonstrating mercy, he was not accorded the same justice as King Philip II of Spain declared him an outlaw and promised a reward for his assassination. Balthasar Gerard wanted the reward and shot the Prince of Orange to death on July 10, 1584, 12 years and one day after the Gorkum martyrs were hung. Gerard was captured, tortured, and brutally executed--obviously not receiving the reward he sought.

Published on July 08, 2014 22:30

July 7, 2014

The Translation of St. Thomas a Becket's Relics

I posted the last letter St. Thomas More wrote to his dear daughter Margaret Roper the day before the anniversary of his martyrdom. In the letter he mentions that he hopes his execution is scheduled for the morrow, before the Feast of St. Thomas on July 7. A Clerk of Oxford explored that feast more fully here yesterday and then discusses some aspects of medieval feasts and devotion to saints:

I posted the last letter St. Thomas More wrote to his dear daughter Margaret Roper the day before the anniversary of his martyrdom. In the letter he mentions that he hopes his execution is scheduled for the morrow, before the Feast of St. Thomas on July 7. A Clerk of Oxford explored that feast more fully here yesterday and then discusses some aspects of medieval feasts and devotion to saints:Translation feasts like today's are particularly tricky to explain to a modern audience. It's easy to be cynical about their original motivation, since the practical benefits are usually so obvious as to make the whole idea seem like nothing more than a money-grab: building a bigger or more prominent tomb to attract and accommodate pilgrims, providing a saint with an extra feast to celebrate (often at a more convenient time of year for travel or liturgical commemoration - as clearly illustrated in the case of Becket, whose December feast, awkwardly close to Christmas, was supplemented by a summer translation one), claiming a saint as belonging to one church rather than a rival, and so on. Some medievalists get very sniffy about the pragmatism of it all, their high-minded idealism clearly offended by the idea of churches trying to make money off their saints. There's a lingering Puritanism in some circles (even within academia, but certainly outside it) which can't quite allow that medieval cults of saints were ever anything but a big con - that the saints of the Middle Ages were mostly a bunch of obscure people who were praised far beyond their merits, credited with patently invented miracles, and lauded in tiresome hagiography, with the aim of extracting money from gullible pilgrims. . . .

But if we take translation feasts as an example, trying to understand rather than to condemn or mock, they can tell us fascinating things about the communities who organised them. They can help us trace, for instance, which parts of a community's history were most important to its identity at any point in time, or how a community defined itself against other nearby houses - the translation of Thomas Becket marked the moment when he became Canterbury's most famous saint (as he remains today), surpassing the Anglo-Saxon archbishop-saints, who were still venerated but no longer as culturally useful as they had been for the community in the period immediately following the Norman Conquest (on which see this post on Dunstan and this on Ælfheah). A translation tells us not all that much about the saint whose physical body is its focus, but a great deal about what a saint's memory meant to the people who venerated him or her. What is really commemorated today, then, is not just Thomas Becket but his importance to Canterbury and to the wider world: the fame which brought pilgrims to his shrine, the political charge which made him important enough for his name to be scratched out and his carols cancelled in the sixteenth century, and, yes, the income which built Canterbury Cathedral, a treasure-house of medieval art which still draws thousands of tourists and pilgrims every year. All this deserves to be remembered - and even blogged about.

Read the rest--and enjoy all the great pictures--there.

Published on July 07, 2014 23:00

The Merode Altarpiece: The Annunciation, with Donors and St. Joseph

Harry Rand, senior curator of cultural history at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History, writes about Robert Campin's Masterpiece, the Merode Altarpiece, now displayed at The Cloisters in New York City, in The Wall Street Journal:

Sadly, relatively few of these works survived the iconoclastic frenzy that accompanied the Netherlands' subsequent embrace of Protestantism. Another problem that long barred the recognition and appreciation of their creators was the elevation of the Italian Renaissance as the universal criterion of artistic quality, an alien standard that automatically demoted these Flemish masters.

Among the obscured painters one of their geniuses languished, long known only as the Master of Flémalle—named for a town now in Belgium. Today we know him as Robert Campin (c.1375-1444), generally recognized as the teacher of the more famous Rogier (Roger) van de Weyden.

Now in the Cloisters, the Metropolitan Museum of Art's upper-Manhattan outpost for Medieval art, Campin's Mérode Altarpiece (c.1427-32) can still startle with its revolutionary formal and technical innovations. A wooden triptych only 25½ inches tall, the work seems too diminutive for so important a painting. But its size derives from its intended use for private worship and meditation. It was probably commissioned by Peter Ingelbrecht, a wealthy merchant; Campin produced what seems, at first, an unremarkable "Annunciation with donors." Yet behind its calm appearance the work delivers a magnificently ambitious ensemble, staggering in visual sumptuousness and breathtaking in its symbolic message.

The Mérode Altarpiece has never been surpassed in symbolic complexity. Campin saturates his scene with emblems designed to show Providence's unceasing hand shaping and guiding the world of Campin's faith.

Read the rest here. Image credit: detail of the center panel.

Published on July 07, 2014 22:30