Diane Lockward's Blog, page 15

June 12, 2015

West Caldwell Poetry Festival Featured Poet: Anna M. Evans

Anna's description of her collection:Before writing Sisters and Courtesans, it occurred to me that, until Anne Bradstreet, the only women writing poetry were outside of society in some way—some royals, but mainly cloistered women and women of easy virtue. Everyone else was busy having babies and raising chickens. I felt it would be interesting to explore women’s lives throughout history using that lens and the sonnet as a form, and to attempt to see what else such women might have in common.

Anna's description of her collection:Before writing Sisters and Courtesans, it occurred to me that, until Anne Bradstreet, the only women writing poetry were outside of society in some way—some royals, but mainly cloistered women and women of easy virtue. Everyone else was busy having babies and raising chickens. I felt it would be interesting to explore women’s lives throughout history using that lens and the sonnet as a form, and to attempt to see what else such women might have in common.Praise for Sisters and Courtesans: "If sonnet means 'little song,' what Anna Evans has crafted here is a sassy selection of female singers, a spirited chorus that takes the figures of different women throughout history, giving life to their stories with frank audacity and lively craft. This book is full of surprise after delightful surprise, deft rhymes and scandalous turns. This is a book to pass from sister to sister, from woman to woman, from friend to friend. But don't worry, fellows, you too will be equally charmed and delighted by this poet who has all the necessary lines and lives to make the sonnet sing with voices you never will think of again in quite the same way."—Allison Joseph

Click Cover for Amazon

Click Cover for AmazonMy Life as a Camp Follower

The fight keeps dragging on. My soldier loverwas badly wounded by a Yorkist axe.I came here in the hope that he'd recover,and stayed on after, in the army's tracks.It's easy living—all the men are lonelyand most are gentle. I say I'm a nursealthough I tend to them in one way onlyand then I slip their pennies in my purse.I use a pessary of wool and wineand drink mint tea in secret. If they sawthey'd call it witchcraft. Well, the risk is mine,all part of women's lot. The men make warand corpses pile crotch deep in England's mud.So many things in life come down to blood.

Anna sent us home with this challenge: Write a sonnet from the perspective of someone who lived in a different age from our own, but do NOT make them a famous or named person in history. Include a non-alcoholic beverage and an eye rhyme.

Published on June 12, 2015 10:12

June 5, 2015

West Caldwell Poetry Feature: R.G. Evans

R.G. Evans, aka Bob, was one of six featured readers at the 2015 West Caldwell Poetry Festival.

R.G. Evans' first collection, Overtipping the Ferryman, received the 2013 Aldrich Press Poetry Prize. His poems, fiction, and reviews have appeared in Rattle, The Literary Review, Paterson Literary Review, Lips, and Weird Tales, among other publications. His original music was featured in the 2012 documentary film All That Lies Between Us. He teaches high school and college English and Creative Writing in southern New Jersey.

R.G. Evans' first collection, Overtipping the Ferryman, received the 2013 Aldrich Press Poetry Prize. His poems, fiction, and reviews have appeared in Rattle, The Literary Review, Paterson Literary Review, Lips, and Weird Tales, among other publications. His original music was featured in the 2012 documentary film All That Lies Between Us. He teaches high school and college English and Creative Writing in southern New Jersey.Overtipping the Ferryman is a collection of poems ranging from the dark to the darkly comic. Themes include mortality, the art of poetry, grief and loss, and the natural world. Most of the poems are free verse, but the book includes formal poems such as sonnets and a villanelle as well.

Praise for Overtipping the Ferryman:

“With an ear that searches and regularly finds language that complicates and fulfills his apparently Manichean vision, R.G.Evans navigates between reverence and irreverence in these often terrific poems. Death and fire dominate their imagery, and a kind of spiritual ferocity their tone. These are spiritual poems that don't attempt to console. They are poems of complicity. Their speaker wants “more,” and knows something about its price. To overtip the ferryman suggests the anxiety behind the journey, the uncertainty of the arrival. It doesn't get much better than this.” —Stephen Dunn

Click Cover for Amazon

Click Cover for AmazonMonth Without a Moon

Any night I like, I can rise instead of the moon

that has forgotten us, not a thought of our sad lot,

and roam the darkened oblongs of the dunes.

Once you said the moon was some pale god

who turned away his face to cause the tides,

and once you said that, I of course believed

that you were mad. Now the ghost crab guides

me to the edge where land is not land, sea not sea,

and all the sky above is one dark dream.

This is the month with no full moon. You

were its prophet, and I am standing on the seam

between belief and what I know is true.

I gave you a diamond. It should have been a pearl.

It should have been a stone to hang above the world.

Here's the prompt Bob sent us home with. Give it a try:

In one of the most famous scenes from the film Jaws, Quint, Brody and Hooper sit in the cabin of the Orca drinking and comparing various scars they have (moray eel bite, thresher shark’s tail). Quint reveals that one mark on his arm is a tattoo he had removed: the USS Indianapolis. He proceeds to tell the true story of the Indianapolis, the ship that delivered the Hiroshima bomb and which ultimately sank, many of the survivors attacked by sharks before the rest could be rescued.

Like Quint’s, the marks on our bodies tell the stories of our lives.

Make a list of all your bodily markings: scars, tattoos, piercings, etc. If you want to go deeper, you can list your emotional scars as well.

Write a poem either 1) in the voice of one of your scars speaking to you (recalling how it came to be, what it has to teach you, etc.) or 2) in the form of a dialogue between two of your scars/markings speaking about you in the third person.

Published on June 05, 2015 08:12

June 4, 2015

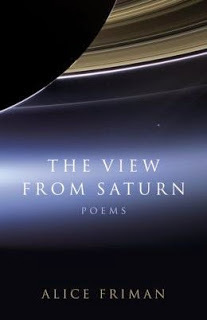

West Caldwell Poetry Festival Features

On Sunday, May 17, I ran the West Caldwell Poetry Festival, something I've been doing for the past twelve years. For the first ten years the focus was on New Jersey's literary journals. Each year I invited twelve journals to participate. Each editor then invited two representative poets to come and read. Journals were on display and for sale in the reference area while readings took place in the Community Room.

Then last year I began to feel that a change was needed so switched the focus to poets with new books. I invited six poets to be featured at the festival. The journals were again included, but the editors did not invite poets to read. Instead, the six featured poets read in two groups of three, each for 15-17 minutes. Journals were for sale as were the poets' books. There was also a panel during which the poets discussed process. And there was a publishers' panel.

This year I decided to repeat last year's format but omitted the publishers' panel so that the readings could be a bit longer as could the browsing time.

Our featured poets this year were Charlie Bondhus, Anna Evans, R.G. Evans, Doug Goetsch, Therese Halscheid, and Adele Kenny. They were all terrific!

In order to extend the festival's reach, I have invited each of the poets to have a feature here on my blog. Those features will begin tomorrow, Friday, June 5. Please be sure to check in and get a sample of the wonderful poets and poetry we had at this year's festival.

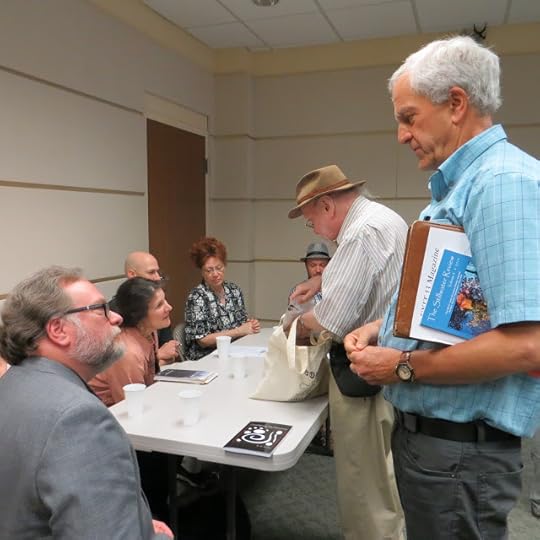

Visitors browsing the journals and meeting the editors

Visitors browsing the journals and meeting the editors

Poets signing books after the panel discussion

Poets signing books after the panel discussion

Published on June 04, 2015 06:14

May 30, 2015

Summer Journals Q-Z 2015

Here's the third and final installment of the list of print journals that read during the summer months. Again, please let me know if you spot any errors or omissions. Good luck!

No rejections allowed.

No rejections allowed.**Remember that the asterisks indicate that the journal accepts simultaneous submissions.Journal accepts online submissions unless otherwise indicated.

**Quiddity—2x

**The Raleigh Review—2x—opens July 1

**Rattle—4x

Raven Chronicles—2x—April 1-July 1

snail mail

**Redactions—2x—by email–opens July 1

**Redivider—2x

**Rhino—1x—April 1-Oct 31

**River Styx—3x—May 1 thru Nov 30

snail mail

**Rosebud—3x

via email

**Sakura Review—2x

**Salt Hill—2x

August 1-April 1

**San Pedro River Review—2x

month of July

via email

**Saw Palm—1x—July 1-Oct. 1

must have a Florida connection

**Smartish Pace—2x

via email

**South Dakota Review—4x

**The Southeast Review—2x

**Southern Humanities Review—4x—Aug 1-Dec 1

**Southern Poetry Review—2x

snail mail or via their website

**Sugar House Review—2x—Jan 31-July 31

**Tahoma Literary Review—4x

**32 Poems—2x

Threepenny Review—4x—reads thru June

**Turnrow—2x

snail mail

**Tusculum Review—1x

US 1 Worksheets—1x—April 15- June 30

snail mail

**Washington Square Review—2x—Aug 1-Oct 15

**West Wind Review—1x—July 1-Sept 1

**Women Arts Quarterly Journal—4x

**Yemassee—2x

Summer Journals A-F

Summer Journals G-P

Published on May 30, 2015 07:51

May 28, 2015

Summer Journals G-P 2015

Here's the second installment of the list of print journals that read during the summer months. If you find any errors or have others to add to the list, please let me know. Good luck with your submissions.

This mailbox is ready to receive good mail.

This mailbox is ready to receive good mail.**Indicates that simultaneous submission is ok

Unless otherwise indicated, the journal accepts online submissions.

**Grist—1x—June 15-Sept 15

Hanging Loose—3x

snail mail

**Hartskill Review—3x

**Hayden’s Ferry—2x—opens for submissions August 1

**Hiram Poetry Review—1x

snail mail

Hudson Review—4x—April 1-June 30 (all year if a subscriber)

snail mail

**Lake Effect—1x

snail mail

Little Star Journal—1x

strong preference for snail mail

strong preference for no sim sub

Louisiana Literature—2x

**Lumina—1x—check in July

**MacGuffin—3x

via email attachment

Manhattan Review—2x

(prefers no sim but will take)

Measure—2x

metrical only

**Michigan Quarterly Review—4x

**Mid-American Review—2x

**Minnesota Review—2x—August 1–November 1

**Missouri Review—4x

**The Mom Egg—1x—June 1-Sept 1

**Naugatuck River Review—2x—July 1-Sept 1

for the winter issue

**Nimrod—2x—Jan 1-Nov 30

snail mail

**Parnassus: Poetry in Review—1x

snail mail

Pinyon—2x

via email

**Pleiades—2x—Aug 15-May 15

**Ploughshares—3x—June 1 to January 15

**Poet Lore—2x

snail mail

**Poetry—11x

Summer Journals A - F

Summer Journals Q-Z

Published on May 28, 2015 10:06

May 25, 2015

Summer Journals A-F 2015

Get your mailbox ready to receive good news.

Get your mailbox ready to receive good news.It's that time of year again. During the summer many of us have more time to write and submit, but quite a few journals close their doors to submissions for the summer months. Do not despair. There are still many journals that do read during the summer and some that read only during the summer. This is the first of a 3-part list of those journals, all print. As in the past, several had to be removed this year as they have closed their doors permanently. But a few have been added.

I've added links for your convenience. I've also indicated the number of issues per year, the submission period dates, which journals accept simultaneous submissions, and which ones accept online submissions. If you find an error, please let me know.

**Indicates that simultaneous submission is ok

Unless otherwise indicated, the journal accepts online submissions.

If no dates are given, the journal reads all year.

**American Poetry Review—6x-tabloid

**Another Chicago Magazine—2x—Feb-Aug 31

**Asheville Poetry Review—3x—Jan. 15-July 15

snail mail

**Atlanta Review—2x—deadlines June 1 & Dec 1

reads all year, but slower in summer

snail mail

**Barn Owl Review—1x—June 1-Nov 1 (NO READING PERIOD IN 2015)

**Bat City Review—1x—June 1-Nov 1

Beloit Poetry Journal—3x

**Black Warrior Review—2x—June 1-Sept 1

**Bone Bouquet—2x (site says they will reopen for subs in June--check for an update)

women only

** B riar Cliff Review—1x—deadline Nov 1

**Burnside Review—2x

email sub ok

$3 reading fee /pays $50

**Caketrain—1x

email sub

**Chariton Review—2x

snail mail

**Cimarron Review—4x

**Columbia Journal—2x—March 1- Sept 15

**Columbia Poetry Review—1x—July 1-Nov 1

**Conduit—2x

snail mail

**Crab Orchard Review—2x—Aug 15-Nov 5 (special issue)

snail mail

**Cream City Review—2x—Aug 1-Nov 1

Field—2x—August 1-May 31

**The Florida Review—2x—Aug 1-May 31 (subscribers all year)

**The Fourth River—1x—opens July 1

Published on May 25, 2015 11:49

May 19, 2015

The Poet on the Poem: Alice Friman

It is my pleasure to feature Georgia poet Alice Friman in this installment of The Poet on the Poem.

Alice Friman’s sixth full-length collection is The View from Saturn from LSU Press. Her previous collection is Vinculum, LSU, for which she won the 2012 Georgia Author of the Year Award in Poetry. She is a recipient of a 2012 Pushcart Prize, is included in Best American Poetry 2009, and has been published in 14 countries. She lives in Milledgeville, Georgia, where she is Poet-in-Residence at Georgia College. Her podcast series, Ask Alice, is sponsored by the Georgia College MFA program and can be seen on YouTube.

Today's poem comes from Friman's latest book, The View from Saturn.

Click Cover for AmazonComing Down

Click Cover for AmazonComing Down

At high altitudes the heart rises

to throat level, clanging for service.

The body—#l customer—needs oxygen,

the red blood cells scurrying like beaten

serfs not delivering fast enough: supply

and demand, that old saw.

Remember

struggling to make love under six blankets,

my heart banging so hard it threatened

to knock me out of bed, and you

in socks, ski hat, and four sweaters, fighting

for breath? When relating our story, paring

it down for parties,

let's leave those parts

out. Say we went to South America

for pre-Columbian art and Machu Picchu.

Mention the giant condors, yes, but not how

they floated up from Colca Canyon

like human souls circling in great flakes

of praise

nor how I cried, reaching to bridge

the unbridgeable gap. Say that one shivering

night we visited a thermal pool, but not

how slippery as twins tumbling in the womb,

we sloshed together under Andean stars.

Or how nose-bleeding or heart-pounding

and laboring for breath,

always always

we reached for each other. Practice the lesson

of the body in distress: the heart knows

how much leeway it has before demanding

its due. Waiting in line for the Xerox calls for

giveaways of more supple truths: cartilage, Love,

not bone.

DL: What was the thinking behind your decision to use dropped lines? What do you think they contribute to the poem?

AF: The poem is in the form of a sort of letter—a mental letter to my husband. But, yes, a letter; therefore the paragraph form with what I think of as paragraph indentations rather than as dropped lines. I think that the paragraph form is useful when a stanza break seems like too much of a break and the alternative is no break at all. It's a sort of compromise, a middle ground, a little break.

When I write, I rarely think about how the poem presents itself on the page. The underlying emotional heart of a given piece usually chooses how it wants to come out. In a first draft, scribbled in ink, the line breaks and stanza breaks will often naturally assert themselves. And then later, after many drafts, I back up and take a look. In the case of this piece, the first two stanzas came out in six lines each. All right, I say, six-line stanzas is what you want? So be it.

DL: The poem includes several negatives: in stanza 3 “but not,” in stanza 4 “nor how” and another “but not,” and in the poem’s last line “not bone.” There’s also a contrast between what really happened and what the two lovers will say happened. And there’s a contrast between what the physical heart wants and what the romantic heart wants. Talk to us about the function and value of contrast in this poem.

AF: Yes, there's much contrast in the poem, and I'm pleased that you pointed it out. But use of contrast is only one part of a process of clarification and narrowing down that this poem employs. The poem begins with the general and little by little moves to the particular. In this case: bone. More important to that process of narrowing is that the piece is written in the negative. Writing in the negative is a technique I use often. What it does is clarify by paring down in steps: no it's not this, nor is it this, nor this, until you get to the point, the conclusion.

I hasten to say that I think if a poet chooses to employ the negative, it's not necessary to have thought about the end before sitting down to write the poem. That's an essay, not a poem. Robert Frost said that a poem is an ice cube melting on the stove. In other words, the poem should be a discovery for the writer in writing it as it is for the reader in absorbing it.

I think writing a poem utilizing a repetition of the negative serves as an example of the poet thinking on paper. And hopefully, the reader, in following the negative steps, becomes a companion to that thinking, thus leading him down, down to the point—in the case of this particular poem, to "cartilage, Love, / not bone." Notice, too, that the poem begins with the body and ends with the body, and so, in a sense, the poem is a circular descending spiral driven by all those negatives.

DL: The repetition of “always” in the final indented line strikes me as one of those little things that mean a lot. Is it strategic? Why repeat the word?

AF: Yes, it's strategic. I repeat the word for emphasis. After all, the poem is a love poem. Even under great physical duress (which we were in) and in the midst of incredible beauty that bordered on the mythic, making us feel small and insignificant, we clung to each other. Yes we did. That is the "bone" I'm referring to at the end, the basic bone of our marriage that isn't necessary to share with idle chat at the water cooler. There's an old Irving Berlin song called "Always" that my husband often sings to me in his sweet tenor voice, a song that always makes me cry. In it the word "always" is repeated and repeated. Perhaps I was channeling that.

DL: Your poem is rich with figurative language. For example, hyperbole occurs in stanza 2 where you have a “heart banging so hard it threatened to knock me out of bed” and in stanza 4 where the two lovers were “nose-bleeding or heart-pounding and laboring for breath.” Hyperbole often doesn’t work in serious poems, but it does in yours. Tell us how you made it work.

AF: My dictionary defines hyperbole as “an obvious and intentional exaggeration.” Let me assure you and anyone reading this that the language I use is neither exaggeration nor hyperbole. We were in the mountains of Peru. We were over 16,000 feet up. I did some research after I got home to understand just how high we were so as to explain the effect that that altitude had on us, especially me. Denver is called “the mile high city.” Its altitude is only 5,183 feet—one third as high as where we were. Sixteen thousand feet is higher than any mountain in the Alps. Twenty-six thousand feet is called “the death zone.” I can tell you honestly and plainly that I understand why. When I speak of “nose-bleeding” in the poem, I am recalling the fact that I ended up in the emergency room gushing from both nostrils. When I say “heart-pounding,” I can tell you that when the heart is laboring so hard, the rest of your body feels like an appendage to be knocked about. If you are lying down, the body twitches uncontrollably and jerks back and forth hard. I did indeed feel as if I were going to be knocked out of bed.

DL: You also employ several similes. In stanza 1 we find “red blood cells scurrying like beaten serfs,” in stanza 3 condors “floated … like human souls,” and in stanza 4 we are told that the lovers were once “slippery as twins tumbling in the womb.” Are these similes to be taken as literally as your hyperboles? How did you arrive at these comparisons?

AF: When I wrote "the red blood cells scurrying like beaten serfs,” I was thinking that red blood cells carry oxygen. People who live in the higher elevations of the Andes have evolved larger red blood cells that are capable of delivering more oxygen. We, on the other hand, are at a disadvantage; the heart has to pump like crazy to drive the blood faster and faster. I imagined the red blood cells as serfs, bent under their load of oxygen, being whipped and driven.

One of the most magical places I've ever seen is Colca Canyon which is twice as deep as the Grand Canyon. You sit on the edge and watch the condors with wingspans of up to ten and a half feet float slowly up out of the canyon. Since they are so big, they have to wait until the sun warms the air enough so that they can rise on the thermals. They do not fly as we know it but float instead, being lifted up and then circling. They seemed weightless like great dark flakes. Before I left, I stood, tilted back my head, and raised my arms; one condor seemed to pause then circle above me like some sort of greeting, and I felt as if I were being blessed. The fact that most people were fussing with their cameras and two men standing next to me were discussing their golf game made me realize again how perhaps I don't belong in this world, which is why I listed this experience as one of the things not to be discussed in passing, in idle chat.

The "tumbling in the womb" refers to one very cold night high in the Andes when we visited a thermal pool. The water was hot as amniotic fluid, the earth's uterine water, and my beloved and I were playing in it. Were we not then children of the earth? twins in the belly of the mother? in the world's amniotic sack?

As for how I arrived at these similes, I just wrote what I saw and what it meant to me.

DL: It’s clear that your poem evolved out of a real experience. What made you sit down and convert the experience into a poem?

AF: Not all poems have a trigger—the thing that gets you started—but this one did, an interesting one. My husband and I had recently come back from Peru, so, of course, our stay there was in my mind and I had been writing about it. It was a late afternoon. I was driving on the outskirts of Columbus, Georgia, I imagine coming home from the Carson McCullers house where I used to go to hole up and write. I passed a street sign that said—or I thought it said—Cartilage Drive. That caught me up. Wow! Cartilage? And I realized that I had never seen that word in a poem. Okay, I said. I shall write a poem whose end will include the word cartilage.

Check out another poem from The View from Saturn: How It Is, featured at Poetry Daily.

Alice Friman’s sixth full-length collection is The View from Saturn from LSU Press. Her previous collection is Vinculum, LSU, for which she won the 2012 Georgia Author of the Year Award in Poetry. She is a recipient of a 2012 Pushcart Prize, is included in Best American Poetry 2009, and has been published in 14 countries. She lives in Milledgeville, Georgia, where she is Poet-in-Residence at Georgia College. Her podcast series, Ask Alice, is sponsored by the Georgia College MFA program and can be seen on YouTube.

Today's poem comes from Friman's latest book, The View from Saturn.

Click Cover for AmazonComing Down

Click Cover for AmazonComing Down At high altitudes the heart rises

to throat level, clanging for service.

The body—#l customer—needs oxygen,

the red blood cells scurrying like beaten

serfs not delivering fast enough: supply

and demand, that old saw.

Remember

struggling to make love under six blankets,

my heart banging so hard it threatened

to knock me out of bed, and you

in socks, ski hat, and four sweaters, fighting

for breath? When relating our story, paring

it down for parties,

let's leave those parts

out. Say we went to South America

for pre-Columbian art and Machu Picchu.

Mention the giant condors, yes, but not how

they floated up from Colca Canyon

like human souls circling in great flakes

of praise

nor how I cried, reaching to bridge

the unbridgeable gap. Say that one shivering

night we visited a thermal pool, but not

how slippery as twins tumbling in the womb,

we sloshed together under Andean stars.

Or how nose-bleeding or heart-pounding

and laboring for breath,

always always

we reached for each other. Practice the lesson

of the body in distress: the heart knows

how much leeway it has before demanding

its due. Waiting in line for the Xerox calls for

giveaways of more supple truths: cartilage, Love,

not bone.

DL: What was the thinking behind your decision to use dropped lines? What do you think they contribute to the poem?

AF: The poem is in the form of a sort of letter—a mental letter to my husband. But, yes, a letter; therefore the paragraph form with what I think of as paragraph indentations rather than as dropped lines. I think that the paragraph form is useful when a stanza break seems like too much of a break and the alternative is no break at all. It's a sort of compromise, a middle ground, a little break.

When I write, I rarely think about how the poem presents itself on the page. The underlying emotional heart of a given piece usually chooses how it wants to come out. In a first draft, scribbled in ink, the line breaks and stanza breaks will often naturally assert themselves. And then later, after many drafts, I back up and take a look. In the case of this piece, the first two stanzas came out in six lines each. All right, I say, six-line stanzas is what you want? So be it.

DL: The poem includes several negatives: in stanza 3 “but not,” in stanza 4 “nor how” and another “but not,” and in the poem’s last line “not bone.” There’s also a contrast between what really happened and what the two lovers will say happened. And there’s a contrast between what the physical heart wants and what the romantic heart wants. Talk to us about the function and value of contrast in this poem.

AF: Yes, there's much contrast in the poem, and I'm pleased that you pointed it out. But use of contrast is only one part of a process of clarification and narrowing down that this poem employs. The poem begins with the general and little by little moves to the particular. In this case: bone. More important to that process of narrowing is that the piece is written in the negative. Writing in the negative is a technique I use often. What it does is clarify by paring down in steps: no it's not this, nor is it this, nor this, until you get to the point, the conclusion.

I hasten to say that I think if a poet chooses to employ the negative, it's not necessary to have thought about the end before sitting down to write the poem. That's an essay, not a poem. Robert Frost said that a poem is an ice cube melting on the stove. In other words, the poem should be a discovery for the writer in writing it as it is for the reader in absorbing it.

I think writing a poem utilizing a repetition of the negative serves as an example of the poet thinking on paper. And hopefully, the reader, in following the negative steps, becomes a companion to that thinking, thus leading him down, down to the point—in the case of this particular poem, to "cartilage, Love, / not bone." Notice, too, that the poem begins with the body and ends with the body, and so, in a sense, the poem is a circular descending spiral driven by all those negatives.

DL: The repetition of “always” in the final indented line strikes me as one of those little things that mean a lot. Is it strategic? Why repeat the word?

AF: Yes, it's strategic. I repeat the word for emphasis. After all, the poem is a love poem. Even under great physical duress (which we were in) and in the midst of incredible beauty that bordered on the mythic, making us feel small and insignificant, we clung to each other. Yes we did. That is the "bone" I'm referring to at the end, the basic bone of our marriage that isn't necessary to share with idle chat at the water cooler. There's an old Irving Berlin song called "Always" that my husband often sings to me in his sweet tenor voice, a song that always makes me cry. In it the word "always" is repeated and repeated. Perhaps I was channeling that.

DL: Your poem is rich with figurative language. For example, hyperbole occurs in stanza 2 where you have a “heart banging so hard it threatened to knock me out of bed” and in stanza 4 where the two lovers were “nose-bleeding or heart-pounding and laboring for breath.” Hyperbole often doesn’t work in serious poems, but it does in yours. Tell us how you made it work.

AF: My dictionary defines hyperbole as “an obvious and intentional exaggeration.” Let me assure you and anyone reading this that the language I use is neither exaggeration nor hyperbole. We were in the mountains of Peru. We were over 16,000 feet up. I did some research after I got home to understand just how high we were so as to explain the effect that that altitude had on us, especially me. Denver is called “the mile high city.” Its altitude is only 5,183 feet—one third as high as where we were. Sixteen thousand feet is higher than any mountain in the Alps. Twenty-six thousand feet is called “the death zone.” I can tell you honestly and plainly that I understand why. When I speak of “nose-bleeding” in the poem, I am recalling the fact that I ended up in the emergency room gushing from both nostrils. When I say “heart-pounding,” I can tell you that when the heart is laboring so hard, the rest of your body feels like an appendage to be knocked about. If you are lying down, the body twitches uncontrollably and jerks back and forth hard. I did indeed feel as if I were going to be knocked out of bed.

DL: You also employ several similes. In stanza 1 we find “red blood cells scurrying like beaten serfs,” in stanza 3 condors “floated … like human souls,” and in stanza 4 we are told that the lovers were once “slippery as twins tumbling in the womb.” Are these similes to be taken as literally as your hyperboles? How did you arrive at these comparisons?

AF: When I wrote "the red blood cells scurrying like beaten serfs,” I was thinking that red blood cells carry oxygen. People who live in the higher elevations of the Andes have evolved larger red blood cells that are capable of delivering more oxygen. We, on the other hand, are at a disadvantage; the heart has to pump like crazy to drive the blood faster and faster. I imagined the red blood cells as serfs, bent under their load of oxygen, being whipped and driven.

One of the most magical places I've ever seen is Colca Canyon which is twice as deep as the Grand Canyon. You sit on the edge and watch the condors with wingspans of up to ten and a half feet float slowly up out of the canyon. Since they are so big, they have to wait until the sun warms the air enough so that they can rise on the thermals. They do not fly as we know it but float instead, being lifted up and then circling. They seemed weightless like great dark flakes. Before I left, I stood, tilted back my head, and raised my arms; one condor seemed to pause then circle above me like some sort of greeting, and I felt as if I were being blessed. The fact that most people were fussing with their cameras and two men standing next to me were discussing their golf game made me realize again how perhaps I don't belong in this world, which is why I listed this experience as one of the things not to be discussed in passing, in idle chat.

The "tumbling in the womb" refers to one very cold night high in the Andes when we visited a thermal pool. The water was hot as amniotic fluid, the earth's uterine water, and my beloved and I were playing in it. Were we not then children of the earth? twins in the belly of the mother? in the world's amniotic sack?

As for how I arrived at these similes, I just wrote what I saw and what it meant to me.

DL: It’s clear that your poem evolved out of a real experience. What made you sit down and convert the experience into a poem?

AF: Not all poems have a trigger—the thing that gets you started—but this one did, an interesting one. My husband and I had recently come back from Peru, so, of course, our stay there was in my mind and I had been writing about it. It was a late afternoon. I was driving on the outskirts of Columbus, Georgia, I imagine coming home from the Carson McCullers house where I used to go to hole up and write. I passed a street sign that said—or I thought it said—Cartilage Drive. That caught me up. Wow! Cartilage? And I realized that I had never seen that word in a poem. Okay, I said. I shall write a poem whose end will include the word cartilage.

Check out another poem from The View from Saturn: How It Is, featured at Poetry Daily.

Published on May 19, 2015 06:45

May 12, 2015

West Caldwell Poetry Festival

This is year 12 for the West Caldwell Poetry Festival. We have a great lineup of six poets and ten journals and editors. Please join us!

See Festival Website for Details, Schedule, and Direction.

Published on May 12, 2015 11:32

May 4, 2015

Joys of the Table: An Anthology of Culinary Verse

Click Cover for AmazonLast week my contributor’s copy of Joys of the Table: An Anthology of Culinary Verse arrived in the mail. Edited by Sally Zakariya and published by Richer Resources Publications, the collection includes food-related poems by 75 poets, the majority women but not all women. Some of the women poets familiar to me are Lucille Lang Day, Carol Dorf, Erica Goss, Charlotte Mandel, Andrea Potos, Susan Rich, and Kim Roberts. The male poets include Lawrence Schimel, Nicholas Samaras, Michael H. Levin, and Conrad Geller. A full list of the contributors with bios may be found HERE.

Click Cover for AmazonLast week my contributor’s copy of Joys of the Table: An Anthology of Culinary Verse arrived in the mail. Edited by Sally Zakariya and published by Richer Resources Publications, the collection includes food-related poems by 75 poets, the majority women but not all women. Some of the women poets familiar to me are Lucille Lang Day, Carol Dorf, Erica Goss, Charlotte Mandel, Andrea Potos, Susan Rich, and Kim Roberts. The male poets include Lawrence Schimel, Nicholas Samaras, Michael H. Levin, and Conrad Geller. A full list of the contributors with bios may be found HERE.The book is divided into six sections: Amuse Bouche, What We Eat, Food and Love, Geography of Food, Kitchen Memories, and Food and Mortality. I found many mouth-watering poems in this tasty collection. I also found some tempting recipes scattered among the poems.

My own contribution, “Linguini,” is included in the Food and Love section.

From the What We Eat section I especially liked this poem by Erica Goss:

Afternoon in the Shape of a Pear

One hundred pounds

on the kitchen counter,

shoulder- to-shoulder

like sweet, lumpy trolls.

I touch each one, feel

hidden seeds moving

and the hairy tickle

of the blossom-ends.

Something so bland

takes sharpness well:

bleu cheese,

the paring knife.

Perishable flesh

glowing like pearl

leaves sugary grains

under my fingernails.

In its lopsided heart

a lute-shaped crater

hides the worm

who, though blind

knows the importance

of being first.

—Santa Clara Review, 2013

A favorite poem from the Food and Mortality section is this one by Susan Rich:

Food for Fallen Angels

If food be the music of love, play on.—Twelfth Night, misremembered

If they can remember living at all, it is the food they miss:

a plate of goji berries, pickled ginger, gorgonzola prawns

dressed on a bed of miniature thyme, a spoon

glistening with pomegranate seeds, Russian black bread

lavished with July cherries so sweet, it was dangerous to revive;

to slide slowly above the lips, flick and swallow-almost, but not quite.

Perhaps more like this summer night: lobsters in the lemon grove

a picnicker's trick of moonlight and platters; the table dressed

in gold kissed glass, napkins spread smooth as dark chocolate.

If they sample a pastry-glazed Florentine, praline hearts—

heaven is lost. It's the cinnamon and salt our souls return for—

rocket on the tongue, the clove of garlic: fresh and flirtatious.

—From The Alchemist's Kitchen , White Pine Press, 2010

The following recipe, contributed by Eric Forsbergh, sounds outstanding. I think I’d better try it soon.

Pavlovas with Berry Topping

Meringues

4 large egg whites

Pinch of salt

1 teaspoon distilled white vinegar or strained lemon juice

1 cup sugar, divided

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

4 teaspoons cornstarch

Berry Topping

1 pint strawberries, rinsed, hulled, and sliced

3 tablespoons sugar

1 cup each fresh raspberries and blueberries

Whipped Cream

1 cup heavy whipping cream

2 tablespoons sugar

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

Set racks in the upper and lower thirds of the oven and preheat to 250 degrees. Line cookie sheets or jellyroll pans with parchment paper. Draw 3- to 3 1/2 -inch-diameter circles, well apart from each other, on the parchment paper and turn the paper over.

Combine egg whites, salt, and vinegar. Whip the whites until they hold firm peaks but are not stiff. Gradually add 3/4 cup of the sugar, then whip in the vanilla. Mix the last 1/4 cup sugar with the cornstarch and fold it in.

Spoon the meringue onto the parchment paper in the circles, spreading and smoothing to fill. Use a spoon to make an indentation in the center to hold the cream and fruit. Bake for one hour. Turn the oven off and leave them in the oven with the door open for another 30 minutes.

For the berry topping, stir the strawberries and the sugar in a bowl. Cover and refrigerate for at least a couple of hours. Just before serving, fold in the raspberries and blueberries.

Whip cream, sugar, and vanilla until soft peaks form. To assemble, place each meringue on a dessert plate. Spoon whipped cream on each and add the berry topping, drizzling the berry juices over all.

This book would make a great gift for friends who love poetry and food. Don’t forget to be a friend to yourself. Bon appetit!

Published on May 04, 2015 07:53

April 30, 2015

Featured Book: The Beautiful Moment of Being Lost, by Michael T. Young

The Beautiful Moment of Being Lost. Michael T. Young. Poets Wear Prada, 2014.

Click Cover for AmazonMichael T. Young has published four collections of poetry, most recently, The Beautiful Moment of Being Lost. He’s the recipient of a poetry fellowship from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts and the 2014 Jean Pedrick Chapbook Award for his collection, Living in the Counterpoint. He’s also received the Chaffin Poetry Award. His work has appeared in numerous journals including Fogged Clarity, The Louisville Review, The Potomac Review, and Rattle. He lives with his wife, children and cats in Jersey City, New Jersey.

Click Cover for AmazonMichael T. Young has published four collections of poetry, most recently, The Beautiful Moment of Being Lost. He’s the recipient of a poetry fellowship from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts and the 2014 Jean Pedrick Chapbook Award for his collection, Living in the Counterpoint. He’s also received the Chaffin Poetry Award. His work has appeared in numerous journals including Fogged Clarity, The Louisville Review, The Potomac Review, and Rattle. He lives with his wife, children and cats in Jersey City, New Jersey. Description:

. . . explores the difficulties and necessities of violating expectation, both one’s own and those of others. Through this necessary risk meaning and growth are found. Throughout the exploration, questions of memory and history, loss and identity are probed.

Blurb:

In The Beautiful Moment of Being Lost, poet Michael T. Young writes with a “dangerous brilliance.” Keening through histories, personal and collective, Young guides the reader to unimagined destinations. Rather than feeling lost, however, the reader arrives at termini of discovery, finding them to be inevitable, necessary, earned. Young enacts these journeys through cognitive leaps that defy reason and syntax, performed by his prodigious wizardry. And as the unknown becomes known, what is lost is regained, for these poems are redemptive. Each one is bathed in a luminosity of phrasing Wallace Stevens would have envied. Young writes, “[H]ear the voice in light / whose only utterance is melting snow.” Unlike snow, these poems will not disappear as long as important poetry continues to matter. (Dean Kostos)

The Beautiful Moment of Being Lost

The secrets of a place are in its small streets,

its narrow passages, the alley in Venice

with cobblestones worn down and wet

by the humidity and dank progression of centuries,

the way we turned the same corner as others

in different years had turned into that dead-end

with its dark alcove, back doors and a wall

gaping with a niche containing a statue

of the Madonna and child, or in Florence

along a street where we pressed

into the painted brick to let a bus go by

while you pulled my backpack out of the way;

gnarled streets in Amsterdam, lower

Manhattan, passages like crooked fingers

pointing the way back to childhood,

when I liked to hide in closets, crouch

in a hamper full of clothing or make a tent

out of a bed sheet. Or the passes

and cul-de-sacs stumbled on in a beautiful

moment of being lost, the way we come

into life, without intention, snug in the primal dark.

More Poems:

The Adirondack Review

Rattle

with audio

Click Here to Purchase

Published on April 30, 2015 05:00