Diane Lockward's Blog, page 2

April 21, 2022

Terrapin Books Interview Series: Robb Fillman Interviews Meghan Sterling

The following is the twelfth in a series of brief interviews in which one Terrapin poet interviews another Terrapin poet, one whose book was affected by the Pandemic. The purpose of these interviews is to draw some attention to books which missed out on book launches and in-person readings. Robb Fillman talks with Meghan Sterling about poetry and place, poetry and parenting, the function of titling, and poetry and form.

The following is the twelfth in a series of brief interviews in which one Terrapin poet interviews another Terrapin poet, one whose book was affected by the Pandemic. The purpose of these interviews is to draw some attention to books which missed out on book launches and in-person readings. Robb Fillman talks with Meghan Sterling about poetry and place, poetry and parenting, the function of titling, and poetry and form.Robert Fillman: Thank you, Meghan, for taking a moment to chat with me about your ambitious debut collection, These Few Seeds , which I loved! The book covers a lot of ground—Brooklyn, London, Greece, California, New England, Texas—was your intention to evoke place (and a range of places) when you set out to write this collection? Or did you have some other governing principle in mind?

Meghan Sterling: It is a whirlwind, isn’t it? A big part of my life has been traveling the world—it was actually in Peru that I decided to have my daughter. As my first collection, I wanted to give it the breadth of my life, all that came before that delivered me to my daughter, as it were, that made me the person who could be her mother, who could mother at all. Traveling also gives me a broader sense of grief about what we are losing to climate change. And she may not take after me, but if she does, I hope she can travel a world that still has sacred and pristine spaces.

Robb: So many of the poems in These Few Seeds are tender representations of motherhood. And yet, they are often textured by an awareness of the environmental crises that threaten to upend intimate moments with your child. Could you talk about the feelings you are working through as you bring these themes together?

Meghan: There is a sharpness in intense joy that sometimes carries the resemblance of intense grief with it. When I was pregnant with my daughter, the wilderness around Asheville, NC, where we were living at the time, was on fire, and Asheville was a bowl of smoke. Australia was on fire, California was on fire, and the Amazon was on fire. The world was on fire. It has been on fire in every way since that time. With my daughter's tender growing comes the grief and uncertainty that this world deserves her, or that the parts that do will survive long enough to become part of the landscape that shapes her. And I write into that fear and sorrow and love.

Robb: I appreciate that the phrase "these few seeds" (which is, of course, the title of the book) appears in the last line of the final poem. It keeps the reader in suspense, waiting for that revelatory moment! Would you walk us through how you arrived at the title of the book and how you see that metaphor operating for the collection as a whole?

Meghan: Oh, titling. I went through so many titles. It took me months. I went from long titles to one word titles—I tried everything. By the end, I knew I wanted something that was three words and contained assonance. I had been inspired by my friend and fellow poet Suzanne Langlois’s chapbook titled, Bright Glint Gone. I loved the clean brevity of it, and the sound of it. Diane Lockward (publisher of Terrapin Books) and I worked together to search through the manuscript for just the right three-word phrase—and she found it!

Robb: I admire a poet that embraces different forms. Free verse clearly dominates the book, but each of the five sections of These Few Seeds experiments with line and stanza length. In fact, it is rare to see two poems in the collection adopt an identical form. Can you explain how you arrive at the formal structures of your work?

Meghan: I love playing with forms. I started out as a formal poet who has branched into the world of free verse and modern sonnets. However, I love to play with the way a poem looks on the page. One criticism I got early on was that my poems were just blocks of text on the page, so I am sensitive to create space and variety.

I like to let the poem inform me as to the shape. Something very dense might become a series of couplets. Something that has a song-like quality or a certain way of repeating itself might become a series of tercets. If something feels breathless and urgent, it might remain in a block of text, without breaks. And, if something has a certain longing in it, it might become a sonnet. But I experiment until it settles into the form that gives it life.

Robb: I loved so many of these poems: "Morning Prayer," "The Absence of Birds," "Man Subdues Terrorist with Narwhal Tusk on London Bridge," "Adeline," "Apology After the Fire." I could go on! If you had to pick a single poem from the book that means the most to you (for whatever reason), which would it be—and why?

Meghan: I have a few. “Still Life with Snow,” “Jew(ish),” and “All That I Have is Yours” are some that jump to mind, but my very favorite is probably “Weaning.” It captures some of the raw feeling, the intense physical love between a mother and child, that I really didn’t know existed until I had my daughter. That deep, powerful, physical love has changed me utterly. That poem captures the anguish at each layer of losing a closeness with her. It was the first one—weaning her. There have been more since, and so many more to come. But when I read that one, I cry a little, every time. And that makes me feel like I got at the truth of something, which is, ultimately, why I write poems.

Sample poem from These Few Seeds:

Still Life with Snow

It fell away, that slant of light

that followed us across the North Sea,

across a stable yard, hoofmarks

sunk into the frozen mud. The way the barn

cut the night in two, the hay steaming,

the chickens soft in the roost. I had dreamt

us before we ever came to be, clutching the cold

like a talisman against the bruising of old dreams,

against the inevitable age that would grip us

in its fulsome mouth, a dog in the stable yard

mawing its one mean bone. And what sky was left

was hollowed moon and piecemeal as a memory

of what I thought I could be if only love would

find me, traveling the Arctic of my heart,

gnawing its white bone.

Click Cover for Amazon

Click Cover for AmazonMeghan Sterling’s work was nominated for four Pushcart Prizes in 2021 and has been published in Rattle, Colorado Review, Idaho Review, SWIMM, Pinch Journal, and elsewhere. She is Associate Poetry Editor of the Maine Review. Her first full length collection These Few Seeds (Terrapin Books) came out in 2021. Her chapbook, Self Portrait with Ghosts of the Diaspora (Harbor Editions) will be out in 2023.

www.meghansterling.com

Robert Fillman is the author of the chapbook November Weather Spell (Main Street Rag, 2019). His poems have appeared in such journals as The Hollins Critic, Poetry East, Salamander, Sugar House Review, Spoon River Poetry Review, and Tar River Poetry. His criticism has been published by ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and the Environment, CLAJ: The College Language Association Journal, and elsewhere. He holds a Ph.D. in English from Lehigh University and teaches at Kutztown University. His debut full-length collection, House Bird, was published by Terrapin Books in February 2022.

http://www.robertfillman.com

April 14, 2022

Terrapin Interview Series: Dion O'Reilly Interviews Yvonne Zipter

The following is the eleventh in a series of brief interviews in which one Terrapin poet interviews another Terrapin poet, one whose book was affected by the Pandemic. The purpose of these interviews is to draw some attention to books which missed out on book launches and in-person readings. Dion O'Reilly talks with Yvonne Zipter about discovery in poetry, dealing with difficult topics, poetry and religion, and finding solace in poetry.

The following is the eleventh in a series of brief interviews in which one Terrapin poet interviews another Terrapin poet, one whose book was affected by the Pandemic. The purpose of these interviews is to draw some attention to books which missed out on book launches and in-person readings. Dion O'Reilly talks with Yvonne Zipter about discovery in poetry, dealing with difficult topics, poetry and religion, and finding solace in poetry.Dion O’Reilly: Nature, or what we now call The Living World, is a prominent feature in your poetry. Do you consider yourself an eco-poet?

Yvonne Zipter: I’ve never actually thought about it, but I think that’s a fair label to apply to my work. If ecopoetry explores “the relationship between nature and culture, language and perception,” as Forrest Gander posits in The Ecopoetry Anthology (eds. Ann Fisher-Wirth and Laura-Gray Street), then it makes perfect sense to apply that term to my work. Kissing the Long Face of the Greyhound , for instance, is organized roughly as a dialogue between the natural world and humans, the intent being to show how they—we—are interrelated. But I tend to agree with Naturalist Weekly that “labels can be challenging for readers and writers. They have a tendency to limit our ability to see the world. One of the things I really appreciate about poetry is that any given poem may produce different meanings to different people. . . . Any poetry that gets you to think about your role or place in the natural world is beneficial and . . . the labels we give them are only helpful if they contribute to the joy of the audience.” That said, I would be honored to be thought of as an ecopoet.

Dion: Do you strive to take turns in your poems, what we call voltas or peripeteia? In other words, do you seek a deeper layer, what Robert Frost called surprise and what many poets call discovery?

Yvonne: For me, part of the joy of writing poetry is discovering what the poem is about as I’m writing it. That surprise or discovery, to my way of thinking, is an important component of a compelling poem, not only for me as the poet but for the reader as well. The delight I feel when an out-of the-ordinary perspective emerges regarding some ordinary thing—I want the reader to feel that delight as well. A poem for which the significance of the subject remains opaque to me is never successful. I end up trying to force a revelation, and the resulting poem feels empty, too glib, uninspired—boring. What I aim for in my poems is being able to take the reader along with me in the process of seeing something in a new way that might ordinarily be taken for granted. Well, that’s not quite true—I write for myself, for the joy of learning something I knew but didn’t know I knew. It’s only afterward that I think about the reader.

Dion: How do you feel poetry should deal with what some call, perhaps unfairly, darkness—topics like death, pain, "the slings and arrow?"

Yvonne: Pain, death, and adversity are common to every living being and are thus topics that should be universally relatable. As a poet, writing about these difficult topics has not only given me solace but has also been a way for me to find beauty and/or poignancy about some of life’s least pleasant moments. The hope is that such poems can allow readers to think about their difficult moments in a new way and/or help them process their own pain or grief. At the very least, poems on topics such as these let people know they are not alone in what they’ve been through.

However, much as with love poems, poems about pain and death are hard to write without falling into abstractions and clichés. I often have to let months or years pass before I can write a poem about something dire that has happened before I can focus on the kinds of details that will let me tell the reader “this was awful” without telling them that.

Dion: You have a few poems which could be interpreted as having a theme of religion versus spirituality—"Still Waters" and "Manners of the Flesh" come to mind. Is this a theme you grapple with?

Yvonne: Religion, in my poems, functions as a sort of shorthand—like myth, in a way—to convey a lot about a subject without having to elaborate in great detail because the themes, terms, et cetera are well-known. I think of myself as a spiritual person. When it comes to traditional religion, I consider myself to be an atheist, but I was raised going to church (three different denominations, actually—Lutheran, Methodist, and Unitarian) and my wife is Catholic, so despite my beliefs, I am nevertheless steeped in this culture. But because I use religious imagery so often in my poems, my wife sometimes teases me that I’m the worst atheist ever. “Manners of the Flesh” was actually written for a friend of mine who has struggled with his own relationship to religion, especially during the time his sister was dying, hence the ambivalence about heaven, prayer, and so on, whereas in “Still Waters” I use the terminology of religion to express my reverence for nature and the awe I often feel in its presence—in other words, as a way to put spirituality on the same plane as religion.

Dion: Danusha Lameris talks about poets having a solace and an irritant. The irritant feels broken or off-kilter and inspires them to speak. But poets also often experience a solace, a relief from that irritant. It appears that the Living World (nature) and your dogs are a solace for you. Would you say that is true? And what is your irritant?

Yvonne: You’ve hit the nail right on the head: nature, including pets, is definitely a place of refuge for me. When I’m looking at a Cooper’s hawk in flight or hugging the dog, I’m not thinking about the precarious nature of our democracy or inequities of race and class. As a kid, I immersed myself in nature, haunting the nearby creek for frogs and garter snakes, climbing trees, and chasing bumblebees and fireflies trying to catch them in a jar so I could watch them up for a while close. But as I got older, I drifted away from the natural world. There was always so much else to do—studying, reading, learning what it was to be a feminist, to be queer. But as things began to slow down a bit, with a steady job and long-term relationship, I found myself drawn to nature again.

As for an irritant, I have a few, from racial inequities to political skulduggery. But these irritants overwhelm me in a way that, for the most part, makes it hard for me to write poetry about them without sounding shrill and prosaic. But then, that gives me something to work toward.

Sample poem from Kissing the Long Face of the Greyhound :

Osteosarcoma: A Love Poem

—for Easton, Zooey, and Nacho

Cancer loves the long bone,

the femur and the fibula,

the humerus and ulna,

the greyhound’s sleek physique,

a calumet, ribboned with fur

and eddies of dust churned to a smoke,

the sweet slenderness of that languorous

lick of calcium, like an ivory flute or a stalk

of Spiegelau stemware, its bowl

bruised, for an eye blink, with burgundy,

a reed, a wand, the violin’s bow —

loves the generous line of your lanky limbs,

the distance between points A and D,

epic as Western Avenue, which never seems to end

but then of course it does, emptying

its miles into the Cal-Sag Channel

that river of waste and sorrow.

I’ve begun a scrapbook:

here the limp that started it all, here

your scream when the shoulder bone broke,

here that walk to the water dish,

your leg trailing like a length

of black bunting. And here the words I whispered

when your ears lay like spent milkweed pods

on that beautiful silky head:

Run. Run, my boy-o,

in that madcap zigzag,

unzipping the air.

Click Cover for Amazon

Click Cover for AmazonYvonne Zipter was born in Milwaukee, WI, and following sojourns on both coasts, has replanted herself firmly again in the Midwest. She lives in Chicago with her wife and a long succession of retired racing greyhounds. She is the author of the poetry collections Kissing the Long Face of the Greyhound, The Patience of Metal (a Lambda Literary Awards finalist) and Like Some Bookie God; the nonfiction books Ransacking the Closet and Diamonds Are a Dyke's Best Friend; the novel Infraction; and the nationally syndicated column "Inside Out,"which ran from 1983 to 1993. Her poems have been published widely in periodicals.

www.yvonne-zipter.com

Dion O’Reilly’s prize-winning book, Ghost Dogs , was published in February 2020 by Terrapin Books. Her poems appear in Cincinnati Review, Poetry Daily, Narrative, The New Ohio Review, The Massachusetts Review, New Letters, Journal of American Poetry, Rattle, and The Sun. She is a member of The Hive Poetry Collective, which produces podcasts and radio shows, and she leads online workshops with poets from all over the United States and Canada.

www.dionoreilly.wordpress.com

April 7, 2022

Terrapin Interview Series: Meghan Sterling Interviews Robb Fillman

The following is the tenth in a series of brief interviews in which one Terrapin poet interviews another Terrapin poet, one whose book was affected by the Pandemic. The purpose of these interviews is to draw some attention to books which missed out on book launches and in-person readings. Meghan Sterling talks with Robb Fillman about masculinity and poetry, parenthood and poetry, ordering poems in a manuscript, and more.

The following is the tenth in a series of brief interviews in which one Terrapin poet interviews another Terrapin poet, one whose book was affected by the Pandemic. The purpose of these interviews is to draw some attention to books which missed out on book launches and in-person readings. Meghan Sterling talks with Robb Fillman about masculinity and poetry, parenthood and poetry, ordering poems in a manuscript, and more.Meghan Sterling: The poems in House Bird, which are lovely, have a thread of masculinity/an examination of men and manhood running through them, both painful and yearning. Can you talk about how you came to a place of writing about manhood? What do you feel is most urgent about doing so?

Robb Fillman: To be honest, I don’t believe it was a conscious act. In other words, I did not set out to write about masculinity per se. I think I started writing poems about the relationships I had with the people around me—my wife, my children, my father, my grandfather, my uncles, my childhood friends, and so on—and I started thinking about what it means to be a father, a husband, a son, a brother. And it wasn’t until well into writing that I noticed that I was actually trying to speak the words that had been, for whatever reason, difficult for me to express in conversation.

Sometimes, I think men and boys feel as though they can’t talk openly about their feelings, so we talk around the "thing" we wish to say, or we don’t talk at all. And I suppose, one of the reasons I started writing poetry was because I felt inarticulate. In that way, the poems could speak for me. And really, it was after I had children when I began to think: I don’t want my kids not knowing what their dad thought or felt. I want them, when they are older, to have a map, to know I was (and still am) a "work in progress." I never want them—my son or my daughter—to be afraid of their own feelings. Poetry opens up that space.

Meghan: How do you feel fatherhood has changed the way you see your father and grandfather? Your mother? How do you feel your poems reflect that?

As I was beginning to say, becoming a parent changed my entire outlook. Until I had children, I don't think I was nearly as reflective as I am now—in my poetry, or just in my daily existence. After having kids though—playing with them, caring for them, reading to them, witnessing their facial expressions, listening to what they say (and don't say)—I came to realize that even the slightest interaction, no matter how insignificant it may seem at the time, affects them. Every experience they have is a discovery.

So becoming a father got me circling back to my own childhood and the people who influenced me. I was very lucky to have nurturing and generous caregivers. But we are all human, so we are flawed and subject to human frailties. I try to be mindful of those complexities in my poetry. If anything, writing about the important people in my life has only made me appreciate them and their experiences more.

Meghan: These poems deal a lot with the intimate spaces of home—in regards to one’s original home and the one we create as adults. How do you approach writing poetry that is located in the familiar, physical spaces of the past and the present?

That's a great question! One of the dangers a writer faces when writing about the familiar is that you very often have to face those spaces (and those people) day in and day out. As a poet, fortunately I have the freedom to play with details in the world of a poem. What I try to honor most are the feelings associated with the experience. When I write about a childhood memory, or a loved one's presence in the home, or something that happened at the breakfast table two days ago, I don't want my thoughts or feelings to be separate from the text I am creating. I want the emotion that I am experiencing at that moment (or about that person) to leach from every corner of the text. To allow that to happen, I have to give myself permission to know that my feelings are momentary, and likely to change ten minutes later. If I didn't allow myself that "out," so to speak, the understanding that what I am writing at any given time is only a snapshot of a situation, and an incomplete one at that, I don't think I would be able to get up the nerve to write about things close to me at all.

Meghan: Which is the poem you feel closest to in this collection?

Robb: That is such a difficult question, though a great follow-up! As you know, every poem contains a part of the writer, so it’s almost like picking which part of yourself you like best. There are poems I am almost certain to read at readings: “House Bird,” “The Bones,” “Superstition,” “For Snowflake,” “The Blue Hour.” Like many of the poems in the collection, these are syllabics that unfold accretively and quietly and build in intensity, so they were all very much written in the same headspace. But if I had to pick just one from the bunch, I would say “Superstition.” To me, this poem represents a turning point in my career as a writer. “Superstition” was the first poem I wrote in which, upon its completion, I was 100% satisfied with the results. I wrote myself out of the idea suddenly and decisively. From the moment I placed the final punctuation mark, I knew that was the poem I was supposed to write that day—and it was at that moment that I started to gain confidence in my ability as a writer.

Meghan: House Bird looks closely at childhood, adolescence and adulthood, and the poems are woven thematically instead of ordered chronologically. How did you choose the poems for this collection and then choose the order—how did you make the choices you did to construct the narrative arc?

Robb: Another great question! I really admire poets who think in terms of an entire book manuscript. They seem to know intuitively what a collection needs, what's missing, the order of things. I haven't been able to do that. I write what I write-- which is a lot of individual poems. And it is only after some distance-- and looking back on what I have created-- that I can begin to see what I've done-- which themes I keep returning to, which voices tend to dominate, which subjects I can’t let go of.

House Bird had many iterations: it was four sections; it was five; it was organized chronologically; it was ordered according to the seasons. It took a lot of shuffling, and it wasn't until Diane Lockward (Terrapin Books publisher) made some excellent suggestions about re-ordering that I was able to see the collection's potential. Rather than create a straightforward narrative, we opted to abandon a linear "plot" or organizational formula and instead create a collage, or maybe several mini collages—a kind of mosaic of experience in which images, and words, and subtle through-lines reveal themselves gradually, building enough resonance to give the reader, by the end, a sense of a uniform whole.

I wanted House Bird to be an excavation of memory, to work the way the mind does, shadows coming and going, hazy outlines sending the reader backwards in time, the familiar drawing them back into the present.

Sample poem from House Bird:

The Bones

What I remember most

are the bones—and my dad's

fingers slimy with guts

as he pulled apart bits

of smoked whiting he bought

from the market downtown.

He sat in the kitchen

most of the afternoon,

working over headless

glistening flesh, picking

through the soft pink insides

without a knife or fork,

offering my brother

and me a horse-radished

peck now and then. We stood

by his side and waited,

listened to him humming

along with Merle Haggard

between long sips of beer.

He was always careful

with the giving, his hands

like a slow, warm current

feeding another. That

cold fish with its many

bones. Dad never let one

slip past. It was all smoke

and silver scales, the tang

of root wet in our mouths.

Click Cover for Amazon

Click Cover for AmazonRobert Fillman is the author of the chapbook November Weather Spell (Main Street Rag, 2019). His poems have appeared in such journals as The Hollins Critic, Poetry East, Salamander, Sugar House Review, Spoon River Poetry Review, and Tar River Poetry. His criticism has been published by ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and the Environment, CLAJ: The College Language Association Journal, and elsewhere. He holds a Ph.D. in English from Lehigh University and teaches at Kutztown University. His debut full-length collection, House Bird, was published by Terrapin Books in 2022. http://www.robertfillman.com

Meghan Sterling’s work has been nominated for 4 Pushcart Prizes in 2021 and has been published or is forthcoming in Rattle, Colorado Review, Idaho Review, Radar Poetry, The West Review, West Trestle Review, River Heron Review, SWIMM, Pinch Journal, and others. She is Associate Poetry Editor of the Maine Review. Her first full length collection These Few Seeds (Terrapin Books) came out in 2021. Her chapbook, Self Portrait with Ghosts of the Diaspora (Harbor Editions) will be out in 2023.

www.meghansterling.com

March 31, 2022

Terrapin Books Interview Series: Karen Paul Holmes Interviews Hayden Saunier

The following is the ninth in a series of brief interviews in which one Terrapin poet interviews another Terrapin poet, one whose book was affected by the Pandemic. The purpose of these interviews is to draw some attention to these books which missed out on book launches and in-person readings. Karen Paul Holmes talks with Hayden Saunier about place in poetry, sections in a collection, selecting a publisher, choosing cover art, and reading/performing poetry for an audience.

The following is the ninth in a series of brief interviews in which one Terrapin poet interviews another Terrapin poet, one whose book was affected by the Pandemic. The purpose of these interviews is to draw some attention to these books which missed out on book launches and in-person readings. Karen Paul Holmes talks with Hayden Saunier about place in poetry, sections in a collection, selecting a publisher, choosing cover art, and reading/performing poetry for an audience.Karen Paul Holmes: I’ve dog-eared so many pages in this beautiful book, A Cartography of Home. Please tell us how this collection came about. I note a thread of homestead/weather/growing things that almost feels pioneer-like, but in a modern sense. And you do, after all, live on a farm. But there are other-located poems too: mini-market, hotel, church, for example. What can you tell us about the sectioning of the book into four parts? How much of the choosing and ordering of poems throughout the collection was purposeful and how much intuitive? Did you write any of the poems for this book specifically or did you assemble poems already written?

Hayden Saunier: I’ve been thinking about place for a long time. I’m a southerner who moved north into cities for theatre opportunities, but I grew up attached to a rural landscape and with an awareness of the innumerable lives that have inhabited a place long before me. Moving to the farm where my husband grew up reignited that deep connection to a particular landscape, but I also wanted to expand on the ideas of home and place to the those “other-locations” you mention (superstores, mini-markets, churches, press conferences, customer helplines) that have become our current and shared cultural landmarks. And when you walk the same fields and woods every day you are confronted by how time is stacked up in layers in a place, like tree rings and soil, so writing about place and home naturally becomes writing about time. That’s been given as an argument for art: It’s a means to stop time. Or a means to enter a single moment and that feels like stopping time.

I love sectioning a book because I think a reader needs a place to rest between poems. I know I do. The way a bench is situated on a walking path to allow a moment to consider the view or tie your shoes or just sit. In A Cartography of Home, the first section begins with concrete considerations of home and habitation, and then those ideas ripple outward in the second and third sections, returning to the concrete and actual by the end. The way a walk works when the mind loosens and makes wider associations between the fixed points of beginning and end.

Some of these poems were begun years ago—I am a constant reviser— and some came into being as part of the process. In general, I’m slow to put a manuscript together; it takes me a while to understand around what center of gravity the poems are orbiting. The title poem came together after many revisions and a recognition that people are places too—until they are no longer here—because here is a place. “Navigational Notes” was among the last poems I wrote for this book so it grew out of the endeavor. It grew directly from the Rene Char quote “how do we bring the ship near to its longing,” and how home is a longed-for place. I loved including that imagined landscape as part of the mapping of home. By the end of work on this collection, like all obsessions, everything I wrote was attached to time and place and home.

Karen: Thanks for that great answer! I’m a northerner who moved south, and your ideas of place and time resonate with me. I also sensed in the middle sections of Cartography the “ripple outward” you mention, and that really did work for me as a reader. And “Navigational Notes” definitely got dog-eared on my first read!

This book and How to Wear This Body were both published by Terrapin Books. (And by the way, both have such compelling covers!) You’ve had two other full-length books and a chapbook published with other publishers. Of your 2013 book, the wonderful Laure-Anne Bosselaar wrote, “Hayden Saunier is a poet of wit, irony, and a huge generosity of heart.” I happily find that to be so true of your work today, too. Why did you choose to publish a second book with Terrapin? Tell us about timing, especially considering the pandemic.

Hayden: Yes, Laure-Anne is a treasure. I’ve been fortunate with book prizes and excellent publishers and working on How to Wear This Body with Diane at Terrapin was a continuation of this great good luck. As for the timing of Cartography , it was a gift that my focus on this manuscript during the first months of lockdown coincided with Terrapin’s decision to launch the Redux series. I’ve learned to recognize luck when I see it! I didn’t trouble myself worrying about the timing of publication with the pandemic and the dearth of readings. I just didn’t. Poems find their way in the world all by themselves, I think.

And thank you for the compliments on the cover images. An extra pleasure working on these two books with Terrapin has been that when we couldn’t quite settle on a cover image for either, I created my own. I’m not a visual artist but I know how to look for inspiration, so full disclosure: the multimedia artist Cecilia Paredes inspired the coat image and Rosamund Purcell’s photographs inspired the nest. The experience of creating and photographing the coat and the nest informed both books as much as the books informed the images. That’s been another way the process of working on this book has been layered from beginning to end.

Karen: It’s very cool that you’ve got the skills to create images that exactly work for your books. You’re also an actress and therefore, of course, an excellent poetry reader. In your work, I can tell you take such care with word selection and sound. When I’ve edited one of my poems to a certain point, I often record myself (or read it to my husband) so I can listen to the sounds and line breaks and feel the poem in my mouth. Do you do something similar? How much does your acting background influence the way you write? What are some actor’s tips you can give to poets who are about to do a reading?

Hayden: I am always speaking a poem as I write—it’s natural to me. I love to read aloud and I love the sound and vibration of words in my mouth and head and chest. My favorite moments as an actor have been the times—which are very rare—when all aspects of a play come together with the sound and the meaning of someone’s brilliant words in your body—it’s transportive. Poetry is the essence of that, and it was through theatre that I came to poetry. It’s so much cheaper to produce—no lights, no costumes, no crew! And best of all, you don’t have to wait for someone to give you a job. But I miss the collaboration of theatre and the discoveries one makes when minds and imaginations knock against one another and work together to create a whole world. As for reading tips, I try to let the images and rhythms of the poems tell their stories. And no “poet voice.”

Karen: So true about poetry! And speaking of collaboration, I’d love to know more about the program you founded called No River Twice (www.norivertwice.org/). Your website calls it “an interactive poetry performance group in which the audience interacts with a group of accomplished poets to determine the direction of each performance from beginning to end, poem by poem, co-creating a reading that is never the same twice.” What else can you tell us?

Hayden: No River Twice is so much fun. We’re a group of poets who do readings from our books but what we read is determined by audience interaction—so we never know where we are going to start or end or what we are reading along the way. We follow the images or ideas in poems like stepping stones across a river and make a cento poem from the connecting lines—a collective poem of the reading. It’s surprising and wide-open and encourages us all to listen to poems in whatever way we like and be playful in whatever way we respond to it. It’s never even remotely the same twice. The idea is to connect without judgement to other voices and finding deep human community there. Another reason for poetry.

Sample poem from A Cartography of Home:

A Cartography of Home

My mother was a place. She was the where

from which I rose. Once on my feet, I touched

my forehead to her knee, then thigh, then hip,

waist, shoulder as I grew into my own wild country,

borderless, then bordered, bound

by terrors, terra incognita and salt seas.

I took my compass rose from her, my cardinal points,

embodiments of wind and names of cloud,

but every symbol in the legend now

belongs to me—rivers, topographic lines and shading,

back roads, city streets, highway lanes that end

abruptly at the broken edge of cliffs

where dragons snorting fire

ride curls of figured waves in unknown seas.

Monsters mark the desert blanks on her charts too.

Before she died, I folded myself back

to pocket-size, my children tucked inside

like inset maps and I lay my head down on her lap.

My mother stroked my hair

the way her mother had stroked hers,

and hers before hers, on and on, and we

remained like that—not long—but long enough

to make an atlas of us, perfect bound,

while she was still a place and so was I.

Click Cover for Amazon

Click Cover for Amazon

Hayden Saunier is the author of five poetry collections, most recently A Cartography of Home (Terrapin Books, 2021). Other collections include How to Wear This Body (Terrapin Books, 2017) Tips for Domestic Travel (Black Lawrence Press, 2009) a St. Lawrence Award Finalist, Say Luck (Big Pencil Press, 2013), winner of the 2013 Gell Poetry Prize, and Field Trip to the Underworld (Seven Kitchens Press, 2012) winner of the Keystone Chapbook Award. Her work has been published in such journals as Beloit Poetry Journal, Nimrod, Southern Poetry Review, Tar River Poetry, and Virginia Quarterly Review, featured on Poetry Daily, The Writer's Almanac, and Verse Daily and has been awarded the Pablo Neruda Prize and the Rattle Poetry Prize. She is the founder and director of No River Twice, an interactive, audience-driven poetry performance group.

www.haydensaunier.com

Karen Paul Holmes has two poetry collections, No Such Thing as Distance (Terrapin Books, 2018) and Untying the Knot (Aldrich, 2014). Her poems have been featured on The Writer's Almanac, The Slowdown, and Verse Daily. Her publications include Diode, Valparaiso Poetry Review, American Journal of Poetry, Pedestal, and Prairie Schooner, among others. She’s the current “Poet Laura” for Tweetspeak Poetry. Holmes founded and hosts the Side Door Poets in Atlanta and a monthly reading with open mic in the Blue Ridge Mountains. She has an MA in musicology from the University of Michigan, was VP-Communications for a global financial company, and has led workshops in business communications, creative writing, and poetry.

www.karenpaulholmes.com

March 24, 2022

Terrapin Books Interview Series: Hayden Saunier Interviews Patricia Clark

The following is the eighth in a series of brief interviews in which one Terrapin poet interviews another Terrapin poet, one whose book was affected by the Pandemic. The purpose of these interviews is to draw some attention to these books which missed out on book launches and in-person readings. Hayden Saunier talks with Patrica Clark about manuscript development, the function of a title poem, the selection of cover art, and more.

The following is the eighth in a series of brief interviews in which one Terrapin poet interviews another Terrapin poet, one whose book was affected by the Pandemic. The purpose of these interviews is to draw some attention to these books which missed out on book launches and in-person readings. Hayden Saunier talks with Patrica Clark about manuscript development, the function of a title poem, the selection of cover art, and more.Hayden Saunier: I’m fascinated by how poetry manuscripts develop. In Self-Portrait with a Million Dollars was there a central idea or proposition or moment that these poems gathered themselves around? A series of explorations that you return to again and again?

Patricia Clark: These poems that became a manuscript that came to be named Self-Portrait with a Million Dollars are not poems of a project, or an agenda. I can’t work that way—with an aim at a project defined ahead of time. I want to write out of my obsessions and, over time, see what results. What are the threads that unite these poems? Feasts, pleasures, and the falling away, the inevitable loss of such pleasures. The longing for connection with others, with ourselves, and with the world. The elegiac thread of loss, lost moments and chances, and also lost loves and selves, missed connections. The awfulness of flux. We want stability—but stasis is a horror—and we get only fragments, of course. Robert Frost’s description of a poem, each one as “a momentary stay against confusion.” Brief, yes, but such great moments and fragments!

Another way of looking at the poems gathered in the book is to note the epigraph at the book’s front by Elizabeth Bishop: “It is like what we imagine knowledge to be: dark, salt, clear, moving, utterly free.” Each poem included here is a bit (a micro bit) of knowledge, knowledge of living in our world. And I love her adjectives. Be ready for some cold, even frigid, North Atlantic water: “dark, salt, clear, moving, utterly free.” Brilliant. Finally, maybe each poem included here is a self-portrait but not called that, as the title poem is. Moments of living, moments of memory.

Hayden: The title poem appears toward the end of the collection and seems to explore the gap between expectation and reality—but I especially love how it also snapshots your family in a moment before “anyone was sundered,” a richness and wealth that we rarely recognize when we possess it. Could you comment on this?

Patricia: Yes, you put your finger on it: the difference or gap between expectation and reality. I don't mean the poem and the experience's end results to be such a letdown—it wasn't really. The buildup was so good, the vision I had was so spectacular, that of course no reality could ever live up to that. Still, I have the great memory of being there with my father, who took the time to bend to my wishes, and so I have/had it all—just not a glimpse of the coins. Well, until later. I did see them in a pile at the fair in Seattle. Memory has preserved it all, fabulously, and the sweet moment with my father. My goal in choosing a title was to have it be memorable, yes, and also to fit the book. I think it does.

Hayden: Tell me a little about the cover of this book. I’m drawn to its primary colors and abstraction but also to the texture and sense of scribble, the reworking and balancing of the shapes, all of which sounds like a writing process. So perhaps I am projecting my own process here. What drew you to this image?

Patricia: I have met this painter, the painter of "Darn"—Mary McDonnell—she's a Michigan painter from Saginaw, Theodore Roethke country. I love her work. Lots of bold abstractions and lots of marks on the canvas as you describe. She works on canvases on the floor, as I've heard her describe it, and she walks round and round the work trying to figure out the orientation, which edge is up. Yes, to me, the painting seems to reveal a process, quite similar to working one's way through a poem, the confusions, the attention to craft and to letting the "meaning" develop on its own almost. The painting is a record of an exploration—in paint, but very similar to a writer’s exploration in words. I was captivated by the boldness of the images and colors and maybe those primary colors speak, especially, to childhood and youth. Maybe the poems inside the book are, after all, primary experiences of dipping one's hand in cold water, as Bishop describes. And one feels something, an icy jolt. Wow, that's knowledge, huh? I like it. I hope my poems take the reader into such a primary experience—with seeing an owl, or walking in a garden.

Hayden: “Feasting, Then” opens the first section with a call to attention to the small marvels and gifts surrounding us in the natural world. “And the Trees Did Nothing” is a poem that confronts our romantic notions about that natural world as the human one literally collides with it—there’s an icy jolt of “knowledge.” These are two examples, but all through the book, your attention and your language focus our eyes and ears on vivid, resonant details of both worlds. How did you develop this keenness of observation?

Patricia: Thanks for the compliment on "keenness of observation." I'll say right off, it has taken me years. And I'm still not really satisfied. How does one describe what one sees: whether a sky or a tree? Impossible. The real sight still escapes one, I think. What I am up to, I believe, is trying to tell the truth about something I see in the physical world. When I get stuck in the poem, I return to that, over and over. What was there? What else was there? Was that everything? And don't make it too beautiful? what was on the ground? Some trash? some dog poop? Let the "divine details" (Nabokov's words) speak. And they will and the poet can step out of the way. And back to another poet, William Carlos Williams—"No ideas but in things." I have no "idea" what a poem is up to—I want to let the details speak and tell the story, tell the moment. If I can do that well, I've done my job, I believe. And it's not easy, even then. If I get the “small” picture right, the big picture of the poem (its meaning, its thoughts and movement) should take care of itself.

Hayden: Often, a poem doesn’t find a first publisher before being included in a book, a poem that we, as writers, adore and are baffled by the fact that the poem never found a home in a journal. Do you have a favorite poem from this book that was ignored or homeless that we can give its full due now?

Patricia: I honestly don't remember the poems and their publication history. I could look it up but won't. I’ll pick out a poem that appeared first in Galway Review in Ireland, a place I love. “After the Darkest Year” only made the journey out one time and it was accepted by the magazine right off, and published very quickly. I pick it out for a few more moments of attention because I wish readers would take the time (if they don’t already) to read poems out loud. This poem is one that I think gets on a particular linguistic, sonic roll. And it’s basically all one sentence. I was trying to just describe and describe and not worry at all about where the poem was heading. Just give the horse its head and let it run! So that’s what I did. Is the darkest year just winter, or something more? Oh, let the reader open to whatever thoughts come to him/her. All of those are in there and are correct. Happy reading!

Sample poem from Self-Portrait with a Million Dollars:

After the Darkest Year

Out of verdant and lush,

oak leaf, Virginia creeper vine,

blackberry wild as today’s wind,

sumac, invasive honeysuckle,

each different leaf a knuckle, earlobe, or palm

of the hand,

in thirty days no less, from dormant

to swaying, leaves shivering and trembling,

one side grayer, one side slick,

shiny on top,

and what gets through of sunlight

dappled and shade-crazed,

sunburst down to a single blade

standing tall on ravine-floor,

leaf-pile, leaf mold, crackle

of still dried stalk and spent

blossom trundled from the yard,

an ancient process, green

to done, down, trampled on, spent,

left here to vegetate, pack deep

under snow, decompose,

and then all starts again,

warbler time just after dormancy breaks,

bud swell and pencil point unfurling

of green, each blossom and ear leaf

sparking in its time—trillium, may-

apple, redbud, lilac, more—

and the welcome scents

[cont’d; no stanza]

lively on the air, fresh and new

as any flower, note of honey,

jasmine, vanilla, lemon, bark,

till all is filled, unfurled, spread wide

and out—umbrella canopy, wand of

Solomon’s seal with berries white,

dangling, ripe—and whose mouth

will surround, pull them off to eat?

So sudden you could blink, miss it, lose

sight of dame’s rocket imagining it

phlox when it’s not, lavender, white,

and pink covering a slope, a hill,

an elevated bank by the creek

or by the busy road usually all dun

and trash, dirt, dust, but now

a gorgeous swell, in bloom, so brief.

Click Cover for Amazon

Click Cover for AmazonPatricia Clark is the author of six books of poetry, most recently Self-Portrait with a Million Dollars (Terrapin, 2020) and the author of three chapbooks. New work appears in Plume, Tar River Poetry, Paterson Literary Review, Westchester Review, I-70 Review, Atticus Review, Midwest Quarterly and elsewhere. She is professor emerita of Writing at Grand Valley State University.

www.patriciafclark.com

Hayden Saunier’s most recent book, A Cartography of Home, was published in 2021 by Terrapin Books. Her work has been published in numerous journals, featured on Poetry Daily, The Writer's Almanac, and Verse Daily, and awarded the Pablo Neruda Prize and the Rattle Poetry Prize. She is the founder and director of No River Twice, an interactive, audience-driven poetry performance group. www.haydensaunier.com

March 17, 2022

Terrapin Books Interview Series: Ann Fisher-Wirth Interviews Christine Stewart-Nuñez

The following is the seventh in a series of brief interviews in which one Terrapin poet interviews another Terrapin poet, one whose book was affected by the Pandemic. The purpose of these interviews is to draw some attention to these books which missed out on book launches and in-person readings. Ann Fisher-Wirth talks with Christine Stewart-Nuñez about book organization, marriage to another creative person, motherhood and poetry, and being a state Poet Laureate.

The following is the seventh in a series of brief interviews in which one Terrapin poet interviews another Terrapin poet, one whose book was affected by the Pandemic. The purpose of these interviews is to draw some attention to these books which missed out on book launches and in-person readings. Ann Fisher-Wirth talks with Christine Stewart-Nuñez about book organization, marriage to another creative person, motherhood and poetry, and being a state Poet Laureate.Ann Fisher-Wirth: In one poem toward the end of The Poet & the Architect , “Map and Meaning,” you write of the difficulty of learning to make “one’s own map” rather than relying on the maps created by others, and you say that the map you eventually created “marked the spirals of stops along my path.” The book itself is structured into four “Rings,” and each section page that announces a new ring has a little drawing of a spiral. So I’d like to invite you to tell us about spirals. What do they signify to you, both in organizing this book and—perhaps—in organizing the “map” of your life?

Christine Stewart-Nuñez: I’m so glad you asked about the spiral! It’s long been a symbol I’ve used. I kept some of my writing from grade school, and spirals abound in the margins of that saved work. Even now, I use the symbol to show “insight” when I’m annotating the margins of a text. In The Poet & The Architect, besides existing as an image in some of the poems, it also serves as an organizational strategy. The spiral helped me conceptualize how poems could return to earlier themes, picking up images introduced in those poems and broadening or expanding them. I decided to start each ring with the most intimate poems and move outward from there. For example, the first poems are short and set both spatially and temporally before the meeting of the poet and the architect. Next the poems move outward from the intimacy of new coupledom to establishing a family and experiencing life together. “Credo,” which employs syllabic lines based on fractal integers, gathers fractal images from life, nature, and architecture, and ends the book with an invocation of time and space in a much broader context. I think ultimately the spiral captures my sense of time—moving forward yet reaching back to a central core. For example, “Credo” ends by connecting the birth of my son Xavier, the death of my sister Theresa, and divine light.

Ann: The Poet & the Architect is a book about a poet who is a wife and a husband who is an architect. Both are creators, and both are engaged in the fundamental work of building a home. What do these two callings share? What have you learned from each other’s work?

Christine: I didn’t really understand myself as an artist—as a maker of things—until I met Brian. Through our conversations, and through my observations of the way he works, I realized that the processes of writing and designing are so similar; I reference that several times in the book, but most specifically in “The Process of an Architect’s Thinking.” By identifying as a literary artist, I give myself permission to experiment more, to play more.

From Brian, I’ve learned a lot about how to engage buildings and places as products of design (or lack thereof). Until recently, I’ve seen myself only as a consumer of buildings—I vastly underappreciated what kinds of work went into creating them. When I asked Brian what he’s learned from my work, he said: “I have found that architecture and poetry have more in common in conveyance than any other form of writing. Architectural drawing, according to Nelson Goodman, is at once sketch, score, and script. It depicts the project, it constructs the project, and it programs the project. Poetic writing at once gives one an image, presents how to say it, and delineates meaning in a way that is analogous to architectural communication.”

Also, I didn’t anticipate learning how energizing it feels to apply the lessons of “process” to building a life together as a couple and as a family.

Ann: Motherhood is a central focus in your book. There are poems about LEGOS and gingerbread houses, a little boy’s fascination with wildfires and typhoons, and also poems about your older son’s seizures and other health problems, poems that add to the developing body of disability literature. In your writing, what are some ways you have found to approach this latter, intensely personal material?

Christine: My approach to motherhood poems comes from a similar emotional space as my other poems: I sense a tension that I want to think more about. Whether it’s a confounding event, an interesting juxtaposition, a pairing of words, or an emotional knot—I want to explore it through sounds, imagery, and (often) metaphor. Even before my oldest son was diagnosed with a rare epilepsy syndrome that caused him to lose his ability to use and understand language for several years, I wrote about him learning to talk. As a poet and mother, I wanted to think more about how my child would learn—and use language in particular. So when these skills began to regress, I needed to explore it with the tools I possessed; most of those poems are in Bluewords Greening. Now, though, I’m interested in exploring how my relationship to parenting has shifted and changed as a result of this experience. In The Poet & The Architect , the poems inspired by Holden are largely speculative; I wonder what his future holds.

That said, I reflect a lot on the ways I represent personal material after the poems get drafted. Within the constraints of the genre, there’s not space for explanation. Because of this, personal experience can transform into something that reads far more abstract, or it gets reduced to one of its many facets. Both can be problematic. I also think a lot about shame, and the reasons that embodied realities like seizures and the behaviors associated with them are stigmatized. When I speculate about what happens to Holden’s memories when impacted by seizure activity, for example, I push against the stigma of epilepsy—naming it, exploring it, discussing what it can do. Of course, my understanding is limited; I can observe and read about seizures, but I’ve never had one.

Ann: You were recently Poet Laureate of South Dakota, and it seems that some of your poems reflect that public engagement—for instance, “Research,” “Marker of Medary,” “Mall Manifesto,” “A Good Building.” Though still personal, they turn outward to consider towns, buildings, history. Please tell us about the relationship between your laureateship and your poetry; did being a poet laureate lead your work in particular directions?

Christine: I often write about place—especially places new to me, places where I’m there, in part, to learn and observe. But it took a decade of living in South Dakota before a South Dakota poem tumbled out. Most of the poems in The Poet & The Architect were drafted before I was appointed poet laureate—influenced by seeing the landscape and architecture through Brian’s eyes. But the laureateship did give me me a stronger sense of citizenship, of wanting to make that place a weightier thread of the book.

Sample poem from The Poet & The Architect:

Blueprints and Ghosts

My husband and I were midnight whispering

in the moment the soul opens after the body’s

sated, that moment when everything’s laid bare

and imagination, past, and present collide—

everything compossible—when he tells me

he helped design a project that still haunts him.

The clients? New Yorkers. Creepy, slick, budget

unlimited. The elder, founder of the lingerie

store housed in every American mall, introduced

the younger client to the team, and he requested

a cabin, a picnic place for models featuring baskets,

bearskin rugs, and a fireplace for cold desert nights.

A glass wall overlooked a vista in New Mexico;

the road-facing wall was windowless save a few

narrow slits. Silk against skin. They shook hands.

How close can one get to evil before it tarnishes?

My husband’s heart skittered across history: architects

who designed concentration camps and gallows.

He wondered how much they knew and when

and how they felt about knowing. He wondered

if design could help men to do bad better. At 55,

he can draw that cabin from memory—the same one

he drew at age 32, the year his daughter was born,

the year a surgeon scraped out a tumor from his knee—

and he can still feel that post-meeting handshake.

That cabin made the news this week: Predator. Sex

trafficking. Hundreds of girls. Now nightmares cross

my husband’s midnights: his hand erases walls, line

after line, page after page until, as he rubs the last angle

away, the cabin returns. Over and over, he begins again.

Click Cover for Amazon

Click Cover for AmazonChristine Stewart-Nuñez, South Dakota’s poet laureate from 2019-2021, is the author and editor of several books, including The Poet & The Architect (2021), Untrussed (2016) and Bluewords Greening (2016), winner of the 2018 Whirling Prize (literature of disability theme). Her poetry has been the basis for international, cross-artistic collaborations with colleagues in music, dance, visual art, and architecture. She recently joined the faculty of arts at the University of Manitoba, where she teaches in the women’s and gender studies program.

christinestewartnunez.com

Ann Fisher-Wirth’s sixth book of poems is The Bones of Winter Birds (Terrapin Books, 2019). Her fifth, Mississippi, is a poetry/photography collaboration with Maude Schuyler Clay (Wings Press, 2018). With Laura-Gray Street, she coedited The Ecopoetry Anthology (Trinity UP, 2013). A senior fellow of the Black Earth Institute, she has had Fulbrights to Switzerland and Sweden, and residencies at Djerassi, Hedgebrook, The Mesa Refuge, and Camac/France; next October, she’ll be in residence at Storyknife, in Homer, Alaska. Her work has received two MAC poetry fellowships, the MS Institute of Arts and Letters poetry prize, and the Rita Dove poetry prize. She teaches at the University of Mississippi, where she also directs the interdisciplinary environmental studies program. For many years, she taught yoga in Oxford, MS.

www.annfisherwirth.com

March 9, 2022

Terrapin Books Interview Series: Lisa Bellamy Interviews Jeff Ewing

The following is the sixth in a series of brief interviews in which one Terrapin poet interviews another Terrapin poet, one whose book was affected by the Pandemic. The purpose of these interviews is to draw some attention to these books which missed out on book launches and in-person readings. Lisa Bellamy talks with Jeff Ewing about what's it's like to write in multiple genres, his use of point of view, and his unique writing process.

The following is the sixth in a series of brief interviews in which one Terrapin poet interviews another Terrapin poet, one whose book was affected by the Pandemic. The purpose of these interviews is to draw some attention to these books which missed out on book launches and in-person readings. Lisa Bellamy talks with Jeff Ewing about what's it's like to write in multiple genres, his use of point of view, and his unique writing process.

Lisa Bellamy: Jeff, Wind Apples is such a memorable poetry collection! I was delighted to have the opportunity to read it. Your biography notes it is your first, and that you’ve written and published in other genres. What led you to poetry, specifically?

Jeff Ewing: Hi Lisa, and thanks for that. I’m really glad you enjoyed it. It is my first poetry book, but it’s been quite a while in the making. I’m not sure whether I came to poetry first, or if—as seems likely—I started with stories, but it was very early. I do like variety, and have been unable, or unwilling, to settle on a single genre. I jump back and forth between poetry, fiction, and nonfiction, with the occasional short play thrown in to round things out. What draws me to poetry is that it lets me play with language more freely, and to tie images and ideas together with a sort of finer thread. I was exposed early on to poetry that seemed far different from the customary grade school assignments. My father was a big Robert Frost fan, and he used to recite his poems as if it were the most natural thing in the world. Not the usual ones; he tended toward the epics. He could sail effortlessly through “The Death of the Hired Man,” but I remember “Mending Wall” and “Birches” making an early impression too. He really loved them, and the effect they had on him was eye-opening. They became a part of him, almost as if he’d helped write them. I think poetry can give you that feeling of participation, that your own thoughts have been captured and refined by someone else.

Lisa: Given that you write in several genres, could you talk about your process? What guides you to knowing whether you’ll work with material in poetry, rather than in one of your other genres?

Jeff: Most times an idea presents itself early on as what it’s going to be—a poem or story or a play. Essays are pretty easy to isolate, since they necessitate sticking to the facts. With other ideas—it may be a phrase or an image or a situation—I look to see what aspect of it calls for treatment. Conflicts or journeys, for instance, usually (though not always) are best suited to fiction. Phrases and very distinct images probably suggest a poem; playing with the language, following one line to the next by practiced guesswork. Many of my poems seem to cascade in that way, by sound as much as sense. Not to say they’re necessarily abstract, just that sound in a poem is very central for me. It’s what separates poems most clearly from the other forms. It’s hard to sustain that kind of music in a story or a play, though they can certainly feature that. And there have been times I’ve changed course in the middle of writing—realizing that a poem should have been a story, or the other way around, or a story would be better reduced to dialogue alone. A few times I’ve explored the same idea in several genres, written a poem over again as a story, or whittled a story down to a poem. It’s fun to play with those things. That, by the way, is a central part of why I write in the first place. The fun and thrill of watching something come out of nothing.

Lisa: Wind apples is such an evocative phrase. I know the meaning—windfalls—but the phrase invites the reader to a wider meaning, a metaphor. And of course, it is the title poem. Is there more you could say about that?

Jeff: The poem really originated from the notion of the mnemonic quality of a smell drifting on the wind. “Wind apples” in that sense, imaginative apples (rotting, tellingly) acting as a trigger. Like the taste of a madeleine, famously. The image of the windfall apples (“the last scrimped fruit”) are a concrete bridge to that idea, to memories stumbled across after their prime. Apples evoke a great deal for me, I’m not sure exactly why. But they can stand in for any common, tangible thing that opens the floodgates. The image seemed apt to the collection, where memory is often both a comfort and a burden, or a taunt.

Lisa: In some poems, the narrator views characters from a different perspective, as in “As the Crow Flies,” or from a third-person perspective, as in “On the Death, by Trampling, of a Man in Modoc County.” What does this change-up do artistically for you, as a writer?

Jeff: It’s very freeing to get away from the constant “I.” Seeing the scene from an abstracted point of view—in “As the Crow Flies”—or a third person, really does allow me to put myself at that vantage. To get a wider, more objective view of the action. The default “I” point of view of a lot of poems—mine included—does convey a certain intimacy, but it’s also constricting. Claustrophobic. I get itchy and anxious after a while. It’s clearly the point of view a writer has the most authority over and experience with, but there’s a danger of coming to see it as genuinely authoritative. As a reader, it makes me suspicious and a little resentful. Like most people I get tired of myself, and it’s a relief sometimes to break out of that.

Lisa: The varied stanza constructions in your collection fascinate me! Each poem has its own “stanza strategy,” so to speak. How do you build your poems? What choices do you make? What is the process?

Jeff:. I wish I could say I have a process. I write when I can—I’ve always had jobs with no connection to poetry or imaginative writing. It’s made my output less than it might have been, but it’s also allowed me to retain a level of excitement at the prospect of sitting down. I think it’s common to feel a little lost at the beginning of each new project, but it’s not unpleasant for me. Each poem is a fresh start. I become something of an amnesiac; suddenly I’ve never done this before and have to dive in blindly. A framework of some kind can help. Occasionally I’ll set out to use an established form, a villanelle or a sestina maybe, but often I’ll devise my own purely arbitrary structure. A given number of lines per stanza, for example; or a visual layout, two lines flush left, one line indented; a single stanza without punctuation carrying a head of steam all the way through. Anything, really, that eliminates a range of options and forces me to focus on manipulating what’s left. It really opens doors for me. That said, a form might change completely during revision, when the plan I’d started out with forces unnatural line breaks or kills the pace. But as a starting point, I find it very helpful. Poems can too easily become uncontrolled and indulgent, and a little bit of a fence—"something there is that doesn’t love a wall” notwithstanding—can corral it before it runs off into the brush.

Sample poem from Wind Apples:

Wind Apples

The orchard, ghosted

in fog, rises in ranks

toward Orion.

The last scrimped

fruit thuds to ground

like footsteps

working downhill,

shuffling through dry

leaves. I meet

myself coming back

when I can’t sleep

and the trees—

heads bowed, branches

clawed with age—

rattle my nights

with remembered harvests.

When the smell of

cider on caught

breath and the spill of

light ripening on

moon-washed skin

drags me uphill again.

One leg stiff with

cold and wear,

my blood thick as

winter sap, I find

our old spot

and eat myself sick

on wind apples,

lug after lug,

carried in unforgiving

gusts down from

the gray crest.

Click Cover for Amazon

Click Cover for AmazonJeff Ewing is the author of Wind Apples (Terrapin Books, 2021), and The Middle Ground: Stories (Into the Void Press, 2019). His poems, fiction, and essays have appeared in publications in the U.S. and abroad, and his plays have been staged in New York, Los Angeles, and Buffalo, New York. He has lived in Chicago, Santa Cruz, and Bergen, Norway, working variously as a technical writer, editor, newsroom PA, copier repairman, forklift driver, longshoreman, and salad boy. He now lives in Sacramento, California, where he grew up.

www.jeffewing.com/

Lisa Bellamy studies poetry with Philip Schultz at The Writers Studio, where she also teaches. She is the author of The Northway (Terrapin Books, 2018) and a chapbook, Nectar (Encircle Publications chapbook prize, 2011). She has received a Pushcart Prize, a Pushcart Special Mention, and a Fugue Poetry Prize. She is working on new collections of poetry and beast fables. She lives in Brooklyn, New York, and the Adirondack Park with her husband.

www.lisabellamypoet.com

March 2, 2022

Terrapin Books Interview Series: Robin Rosen-Chang Interviews Diane LeBlanc

The following is the fifth in a series of brief interviews in which one Terrapin poet interviews another Terrapin poet, one whose book was affected by the Pandemic. The purpose of these interviews is to draw some attention to these books which missed out on book launches and in-person readings. Robin Rosen Chang talks with Diane LeBlanc about book design, grief in poetry, prose poems, and more.

The following is the fifth in a series of brief interviews in which one Terrapin poet interviews another Terrapin poet, one whose book was affected by the Pandemic. The purpose of these interviews is to draw some attention to these books which missed out on book launches and in-person readings. Robin Rosen Chang talks with Diane LeBlanc about book design, grief in poetry, prose poems, and more.

Robin Rosen Chang: I loved The Feast Delayed, Diane. Congratulations on this gorgeous book. While reading it, I noticed what I consider a tension between the act of living and the act of grieving. On one hand, poems such as “The End of Grief” or “Last Day of September” offer the idea of hope and moving beyond grief, whereas in “Orientation,” the speaker, who is married to an astronomer, reflects about living “in a state of constant orientation.” Is acceptance of where one is oriented at a particular moment, even if it’s somewhere painful, a central concern in The Feast Delayed? Of course, this also relates to the notion of “the feast delayed.”

Diane LeBlanc: I’d love to turn that question back to you because your collection, The Curator’s Notes, particularly the title poem, reflects on the dynamic tension between living with wonder and grieving. Reflection ideally examines the past, analyzes experience, and imagines how we respond to new experiences based on the past. The tension in “Orientation” is between hyper-awareness of where I am and the confusion caused by lack of orientation, or living in rooms painted the same shade of white that blur into one another. So in a way, yes, acceptance of where one is oriented is a central concern. I wrote many of these poems between 2015 and 2020, when the U.S. political landscape shifted, science deniers influenced public policy, and I no longer understood who I was in the changing narrative of America.

Throughout the book, I explore responsibility and my place in a web of being, hoping to measure how my choices move or disrupt other strands of the web. Perhaps the feast is delayed, but the poems find agency in doing things to salvage and to disrupt.

Robin: One of my favorite poems in your collection is “Possum.” In this poem, the speaker chides herself for not checking if there were live babies in the pouch of a dead possum she found in the grass. The speaker then asks herself, “What if I rolled the possum with my foot, opened her like a purse, and rummaged through the dead to find only more dead? What plea do I answer when it’s too late to salvage the living?” This is such a powerful question. It’s about more than grief. It’s as if the speaker carries the burden not only to accept loss but also to heal the living. Could you talk about this?

Diane: I appreciate your insightful reading of this poem. Your observation may inform how readers perceive other poems in The Feast Delayed. Obviously, I wrote this poem after encountering a dead possum. No one responded to calls to remove the body, so it became an artifact of loss that I confronted almost daily when my dog and I walked around the pond. My grief for this small creature was informed by larger ecological loss. An earlier poem in the book, “Stars to Fire,” begins, “This is the year we lost stars to fire.” In “Possum” and other poems I explore the question of whether or not I have done enough, or anything, to salvage the living. I live with that same question as I witness the devastation caused by climate change. It’s another way of asking, “In what ways am I responsible for this loss?” I remember being profoundly moved by Marie Howe’s book, What the Living Do. Although I continually articulate, “I am living,” as the speaker does in the last poem of that collection, grief and responsibility to the living are inseparable.

Robin: You have an incredible facility with metaphors. A few standouts for me include: “Language is the velvet grenade/whose pin I keep replacing” (“Six Variations on an Accident”); “…you confessed your thoughts were razors floating in a tub” (from “Reconciliation”); and “Metaphor from a distance is my comfort” (“December Hospice”). How do you craft such inventive metaphors, and how does metaphor function throughout the book?

Diane: Thank you, and I love this question. As an undergraduate in the 1980s, I studied X.J. Kennedy’s An Introduction to Poetry in my poetry genre and writing courses. Several chapters auger into metonymy, synecdoche, and all of metaphor’s nuances. I still have and use my copy, which has deteriorated to loose pages bundled with a rubber band. Contrary to claims that poetry complicates or muddies ideas, I believe that effective figurative language brings us closer to things and ideas. I’m an embodied writer, so when I’m composing I often make gestures with my hands to understand the physicality of process, shape, and movement. That’s when metaphors develop. At other times, I write very quickly and let the language fly in all directions. Those drafts may not survive as poems, but I sometimes find ideas for metaphors that will clarify other poems. Metaphors are central to the collection for a reason I touched on above. I wrote these poems during a period of ecological, political, and personal uncertainty. Expressing the unknown through the known, which is the outcome of metaphor, was one way of grounding poems of uncertainty, loss, and hope.

Robin: Almost one-third of the collection consists of prose poems. What inspired you to write so many of the collection’s important poems in this form? Do you feel it is better suited for the material you were working with?

Diane: I write both poetry and lyric essays. Are you familiar with Annie Dillard’s essay “To Fashion a Text?” She writes that when she gave up poetry to write prose she felt as if she had “switched from a single reed instrument to a full orchestra.” Her description upset me at first because it situates poetry as a deficit genre. Then I started writing essays and understood Dillard’s contrast. But I didn’t leave poetry behind. Prose poems exist in the sweet spot where poetry and prose live together. For me, a good prose poem offers the full orchestra experience with some stunning single reed solos.

When I’m drafting, I don’t decide in advance if I’m writing poetry or prose. I let the language determine what will happen. When a poem with line breaks depends on narrative, but it’s too compressed or lyric-driven to be prose, I’ll eliminate the line breaks to see how it reads. Each of my published collections has an increasing number of prose poems until, as you observe, they comprise almost a third of the poems in The Feast Delayed. Some of the poems went back and forth several times as I experimented with how to tell a particular story. In the end, the blurring of poetry and prose emerged as the necessary form to write about orientation, loss, and transformation.

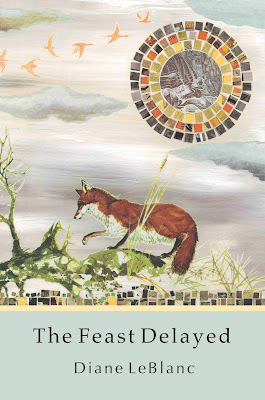

Robin: I visited your website and saw samples of your stunning book arts. How did you get into book arts, and how does it relate to your writing? Perhaps you might also like to comment on the artwork on the cover of The Feast Delayed.

Diane: I’m a book nerd. I love paper, font, white space, stitching, everything about books. By the time I started an MFA in creative writing, I had been writing and publishing for over 20 years and wanted new ways to use form and image in poems. I had a rare opportunity to take a course co-taught by poet and collage artist Deborah Keenan and poet and book artist Georgia Greeley. They introduced me to the basics of shape, balance, color theory, and book arts, and I’ve learned more through the Minnesota Center for Book Arts. The tactile experience of making books influences how I think about words and white space on a page. I sometimes use book form or collage to shape a poem. Several of the poems in The Feast Delayed are responses to collages I made. I wouldn’t have written the book’s final poem, “Gretel’s Campaign,” without this process. And that poem enabled me to see the book’s larger themes of personal and ecological survival.

My love of paper eventually led me to artist Molly Keenan’s paper mosaics and collages whose images of sun, moon, trees, birds and foxes and deer, and seasonal change speak to me. When I discovered “Dreaming Minnesota: December Fox,” now the cover art for The Feast Delayed, I felt immediately that the fox in mid-step against the gray-blue sky conveyed the book’s tone. And of course, foxes appear in these poems.

Sample poem from The Feast Delayed:

Click Cover for Amazon