Karl Shuker's Blog, page 64

July 13, 2012

THE PEACOCK-PLUMED WINGED SERPENTS OF GLAMORGAN – A ZOOMYTHOLOGICAL CURIOSITY FROM WALES

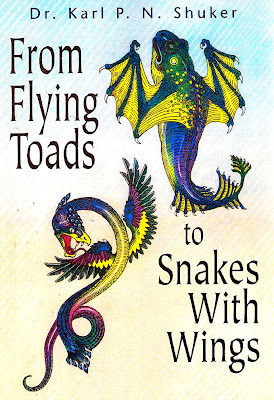

A winged feathered serpent from Glamorgan (as appearing on the front cover of my book From Flying Toads To Snakes With Wings (Llewellyn: St Paul, 1997))

A winged feathered serpent from Glamorgan (as appearing on the front cover of my book From Flying Toads To Snakes With Wings (Llewellyn: St Paul, 1997))British mythology is replete with folktales and legends of fabulous beasts, including many that feature dragons and other reptilian monsters. Surely the most remarkable of these, however, are the jewel-scaled, plume-winged wonders that were reportedly still existing in Wales as recently as the 1800s.

Marie Trevelyan brought these exquisite creatures to widespread attention in her book Folk-Lore and Folk Stories of Wales (1909), and her description of them is so vibrant and uniquely detailed for such an ostensibly implausible type of beast that it deserves quoting here:

"The woods round Penllyne Castle, Glamorgan, had the reputation of being frequented by winged serpents, and these were the terror of old and young alike. An aged inhabitant of Penllyne, who died a few years ago [c.1900], said that in his boyhood the winged serpents were described as very beautiful. They were coiled when in repose, and "looked as if they were covered with jewels of all sorts. Some of them had crests sparkling with all the colours of the rainbow." When disturbed they glided swiftly, "sparkling all over," to their hiding places. When angry, they "flew over people's heads, with outspread wings bright, and sometimes with eyes too, like the feathers in a peacock's tail." He said it was "no story invented to frighten children," but a real fact. His father and uncle had killed some of them, for they were "as bad as foxes for poultry." The old man attributed the extinction of the winged serpents to the fact that they were "terrors in the farmyards and coverts."

"An old woman, whose parents in her early childhood took her to visit Penmark Place, Glamorgan, said she often heard the people talking about the ravages of the winged serpents in that neighbourhood. She described them in the same way as the man of Penllyne. There was a "king and queen" of winged serpents, she said, in the woods round Bewper. The old people in her early days said that wherever winged serpents were to be seen "there was sure to be buried money or something of value" near at hand. Her grandfather told her of an encounter with a winged serpent in the woods near Porthkerry Park, not far from Penmark. He and his brother "made up their minds to catch one, and watched a whole day for the serpent to rise. Then they shot at it, and the creature fell wounded, only to rise and attack my uncle, beating him about the head with its wings." She said a fierce fight ensured between the men and the serpent, which was at last killed. She had seen its skin and feathers, but after the grandfather's death they were thrown away. That serpent was as notorious "as any fox" in the farmyards and coverts around Penmark."

In 1812, very similar beasts were also reported in the Vale of Edeirnion, northern Wales.

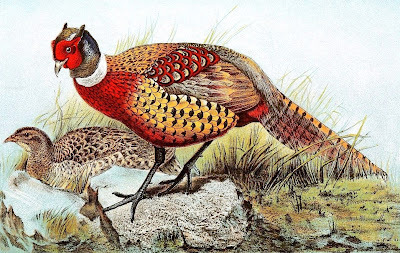

What could have inspired such astonishing accounts? Remarkably, it has been suggested by one or two folklorists and cryptozoologists that these truly exceptional creatures were pheasants. As the ring-necked pheasant Phasianus colchicus (the only species present in Wales during the early 19th Century) was introduced into Britain back in Roman times, however, it seems unlikely that a species so well-established here by the 1800s could be mistaken for anything as exotic as a plumed serpent with wings. In any case, only the males of this pheasant species possess colourful feathers.

19th-Century colour illustration of a pair of ring-necked pheasants

19th-Century colour illustration of a pair of ring-necked pheasantsEven less likely is the prospect that they represented an unknown species of pheasant, one perhaps that was more elongate in form than usual (possessing a longer-than-typical neck and tail?), so as to present a vaguely serpentine appearance. For if this were so, there is no doubt whatsoever that many specimens of such a distinctive and extremely eyecatching bird would have been diligently preserved as prized taxiderm exhibits in country manors and museums. Such a striking form of game bird would also have been extensively documented and depicted in countryside magazines or those devoted to hunting and shooting - sports that were extremely prevalent and popular throughout Britain two centuries ago, and obviously it would have been instantly recognised by hunters, poachers, and gamekeepers alike as a mere bird, not some bizarre reptilian entity more akin to the Aztecs' deified Quetzalcoatl!

In short, if such a spectacular, impossible-to-overlook bird had ever inhabited Wales as late in time as the 1800s, it would have been formally discovered and described long before it was ultimately exterminated. Instead, it is conspicuous only by its absence from natural history tomes and from any other wildlife publications, being solely confined to the pages of Trevelyan's book and to scant mentions elsewhere in other works of British mythology.

Equally difficult to explain if these bedazzling beasts were genuinely pheasants (known or unknown species notwithstanding) is their appetite for the farmers' chickens, earning them the reputation of being as troublesome on this score as foxes. Whereas male pheasants can be aggressive, it hardly need be pointed out that they do not feast upon chickens. Ditto for the possibility that they constituted escapee peacocks. And there is no known bird of prey native to Britain (or, indeed, anywhere else in the world for that matter) that matches the multicoloured, glittering appearance described for the thoroughly baffling albeit very beautiful creatures under consideration here.

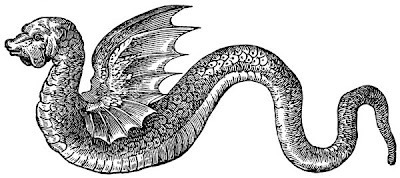

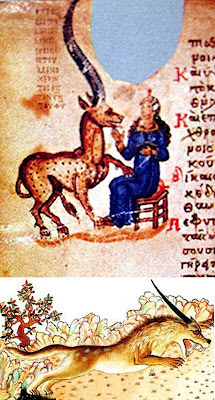

An amphiptere, as depicted in a medieval bestiary

An amphiptere, as depicted in a medieval bestiaryThe same situation also arises when seeking parallels outside the confines of recognised natural history, by venturing forth instead within the more flexible boundaries of zoomythology. An association with buried treasure or similar hoards of riches is of course a familiar theme in dragon myths, but otherwise there is nothing even vaguely comparable between Wales's winged feathered serpents and any other beast in British legends and folklore. (True, a few amphipteres occur - winged serpent dragons, i.e. resembling snakes but dragon-headed and possessing a pair of bat-like wings - but these are not clothed in flamboyant plumage.) For not only is their morphology exceptional, so too are their surprising erstwhile abundance and the acceptance of them by the local people as relatively mundane members of the area's fauna.

If only the skin and feathers of a killed specimen had been preserved and submitted for scientific examination instead of being discarded. After all, it's not every day that the opportunity to examine the mortal remains of a winged, feathered, serpent arises!

Published on July 13, 2012 14:27

July 11, 2012

SOLVING THE MYSTERY OF SCHOMBURGK'S MISSING MICRO-SQUIRRELS - AND REVISITING TANZANIA'S FLYING JACKAL

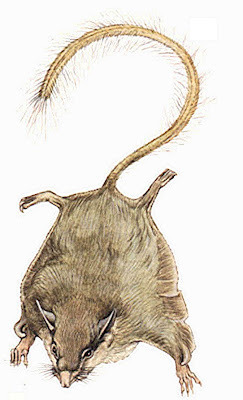

Large-eared flying mouse Idiurus macrotis (Jonathan Kingdon - Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals)

Large-eared flying mouse Idiurus macrotis (Jonathan Kingdon - Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals)It's often been said that good things come in small packages, and this is certainly true of the following cryptozoological case, in which the cryptid in question may be minuscule but is definitely no less memorable for that.

The German explorer/naturalist/film-maker Hans Schomburgk (1880-1967) earned a lasting, well-deserved place in zoological and cryptozoological history by rediscovering on 13 June 1911 the pygmy hippopotamus Choeropsis liberiensis, alive and well in Liberia – where it had long been known to the native people as the nigbwe, yet had been ignored by scientists.

Pygmy hippopotamus (Cliff1066/Wikipedia)

Pygmy hippopotamus (Cliff1066/Wikipedia)Indeed, until then this enigmatic species had generally been discounted as nothing more than a freak of nature, consisting merely of dwarf, stunted specimens of the larger, common hippopotamus Hippopotamus amphibius, or even as a juvenile form of the latter – despite American zoologist Dr Samuel G. Morton having officially named and described it as a valid, second species of hippo more than half a century earlier in 1849. Following its rediscovery by Schomburgk, however, studies confirmed its status as a valid and very distinct species in its own right. (For full details concerning the pygmy hippo's controversial history, see my book The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals (Coachwhip: Landisville, 2012).)

These were the first live pygmy hippos that I ever saw, at Bristol Zoo during the late 1960s/early 1970s (Maurice Beere)

These were the first live pygmy hippos that I ever saw, at Bristol Zoo during the late 1960s/early 1970s (Maurice Beere)Yet whereas Schomburgk became famous for refinding this erstwhile cryptid, it was by no means the only creature of cryptozoology that he had heard about during his numerous African expeditions. In his book Zelte in Afrika ('Tents in Africa'), published in 1957 but looking back upon his explorations and researches from the past six decades, he documented a number of very interesting mystery beasts, some of which were new to me when they were brought to my attention recently by German cryptozoological investigator Markus Bühler.

Although I'd heard of Schomburgk's book, and had read a little concerning his cryptozoological accounts in other publications, I'd never seen a copy of it. Nor had I received any excerpts or summaries from it, until Markus very kindly provided me with the following information:

"There are so many cryptids in Schomburgk´s "Zelte in Afrika", including some he has seen himself, which were nowhere else documented...

"He wrote for example he once encountered several small mammals which looked like tiny squirrels, and which were extremely tame. They were so cute he didn't want to kill one for his collection, and later he learned these animals were never seen before (and never again)...

"There were also some stories which he heard from natives, but without further information, about a giant hyaena, a "jungle tiger" and I think also a mokele-mbembe-like animal. If I remember correctly he also brought a sculpture of some kind of water monster back to Germany, which was in the archives of the ethnological museum at Hamburg, but later given back (but there is still a copy I think). It's already been some time ago since I read the book the last time, but there are really a whole lot of great stories, and a lot of information about water elephants."

As I was so intrigued by the tantalising snippets above, Markus checked through his copy of Zelte in Afrika for further details, and this is what he found:

"Luckily I have put a bookmark at the pages which mention some cryptids.

"So here are some animals which are sadly only mentioned: the lion-tiger (not jungle tiger as I thought) of Senegal, the giant hyaena, the water-leopard [of] Mafue [near Zambia's Lukanga Swamp] which is depicted in the sculpture he discovered.

"He also heard reports about chimpekwe [aka chipekwe] at Lake Bangweulu [in Zambia].

"He mentions also a creature called koo-be-eng, some kind of giant snake-like reptile with a horn on its head, which lives in the water and eats big animals. He wrote that there is a depiction of such a beast in a cave at Brackfontein [in South Africa].

"There is also kou-teign-koo-rou - lord of the water, which was said to be bigger and stronger than a hippo and also living in swamps.

"Bushmen caught it with very strong traps, and he mentions also depictions.

"He also heard tales about the animal tu from the upper part of Morfi River [in Liberia], which was said to be as big as a goat, with teeth of a dog, black fur, and to be quite vicious.

"And a giant ape from Vey-Land which was like a huge greyish yellowish chimp with long fur, which kills or mutilates humans."

Although all of these beasts sounded very interesting (I was already aware of the tu, chipekwe, and water leopard, but not the others), the one that fascinated me most was the Liberian micro-squirrel. For although Schomburgk had stated that these delightful little creatures had never been seen again since his encounter with them, they instantly reminded me of an obscure but formally-described and definitely still-surviving species that I had read about somewhere else. So I asked Markus if he could provide me with a translation into English from Schomburgk's book of the entire passage describing them, and here it is: (Thanks, Markus!)

"During my search for Choeropsis liberiensis I found a bush which was full of lovely small animals. Full of beans, they were. They were grey-brown coloured, reminiscent of tiny squirrels. I put my hand in the bush. The tiny cute beasts whizzed on my palm, stood upright like small rabbits and jumped from finger to finger. Noticeable was the long tail, with feather-like erected hairs. When I tried to hold one on it, it broke off. I repeated this experiment, but always with the same result, so brittle was this, with a thin skin-covered chain of tiniest vertebrae. Surely they were some kind of pygmy mouse. As I was on a hunt, I had no vessel with me, in which I could have caught one of the beasties alive. Only the spirit jar, which one of my native helpers carried. I let him uncap it, to include at least one or two of these beings in my collection. But at this moment the tiny mice looked at me with their big wide eyes in such a clever trusting way, I had not the heart to exploit their trust in the giant who was so mysterious to them. It doesn't have to be today, I thought. I will come back tomorrow or the day after tomorrow and incorporate the lovely bush pygmy mouse into my menagerie. But never again, neither back then nor later, have I or any other explorer found any sign of this odd little animal. And what grieves me most: since then, I have learned that I'd had an animal in my hand that had never been seen in my homeland and which was unknown to science. I have enriched zoology with some discoveries: the Bubalus schomburgki (a type of Liberian buffalo), the already mentioned shell Mutela hargeri schomburgki, five species of earthworm, from which two have my name as well. However, my lively little mouse belongs to those animals that exist yet which have still not been secured for science."

After reading this account, conversely, I was even more convinced that I knew the identity of Schomburgk's mystifying little mammal, because many years earlier I had read about another famous naturalist not only seeking but successfully encountering what seemed to be an identical mini-beast elsewhere in West Africa. The book in which this search appeared was The Bafut Beagles (Rupert Hart Davis: London, 1954), recounting the author's many adventures during a private expedition to Cameroon in 1949, collecting wild animals to sell to zoos. And the name of that author? None other than Gerald Durrell.

My much-treasured Penguin paperback edition of The Bafut Beagles (the very first Gerald Durrell book that I ever read, and which swiftly led to my devouring each and every other book written by him!)

My much-treasured Penguin paperback edition of The Bafut Beagles (the very first Gerald Durrell book that I ever read, and which swiftly led to my devouring each and every other book written by him!)One creature that Durrell was particularly anxious to find and collect while in Cameroon belonged to a fascinating but scarcely-known genus of rodents – Idiurus, the flying mice (a somewhat unfortunate name, as they are not mice, and they glide rather than fly!). And the species of Idiurus that he was seeking was I. kivuensis (which, as will be seen, has a somewhat convoluted taxonomic history).

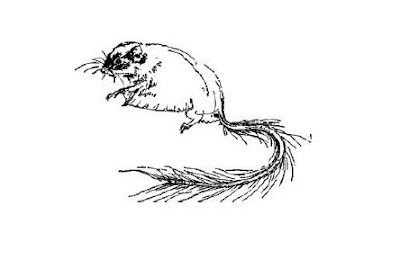

Idiurus kivuensis as depicted in The Bafut Beagles (Ralph Thompson)

Idiurus kivuensis as depicted in The Bafut Beagles (Ralph Thompson)Idiurus is one of three genera of squirrel-like rodents belonging to the taxonomic family Anomaluridae. Exclusively African, this family's members are known collectively as anomalures ('strange tails') or, more colloquially, as scaly-tails, because they are all characterised by two rows of overlapping keeled scales on the underside of their tail near the base. Moreover, all but one species also possess a pair of gliding membranes, linking their front and hind limbs on each side of their body.

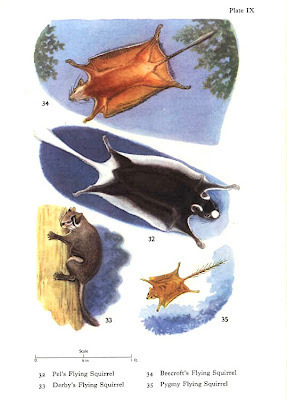

Three species of scaly-tail, including both species of flying mouse (Jonathan Kingdon - Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals)

Three species of scaly-tail, including both species of flying mouse (Jonathan Kingdon - Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals)Consequently, scaly-tails superficially resemble true flying squirrels or petauristids, but their cranial structure is very different, so they are only distantly related to those latter rodents. Instead, their outward similarity is due to convergent evolution (so too is that of the even more distantly related flying phalangers - a group of squirrel-like gliding marsupials native to Australia).

The smallest scaly-tails are the so-called flying mice or pygmy scaly-tails, belonging to the genus Idiurus. Today, only two species are recognised – I. macrotis, the long-eared flying mouse (formally described in 1898, and native to western and central Africa, ranging from Sierra Leone to the Democratic Republic of Congo); and I. zenkeri, Zenker's flying mouse (formally described in 1894, and native to central and central-west Africa, ranging from Cameroon to the Democratic Republic of Congo).

Zenker's flying mouse (Eveha/Wikipedia)

Zenker's flying mouse (Eveha/Wikipedia)At the time of Durrell's expedition, however, a third species was also recognised – I. kivuensis, the Kivu flying mouse. When this was originally described in 1917 by Swedish mammalogist Dr Einar Lönnberg, he had categorised it as a subspecies of I. zenkeri, but in 1946 mammalogist Robert W. Hayman from London's Natural History Museum had elevated it to the level of species. Thus it remained until 1963, when it was reclassified by Belgian mammalogist Prof. Walter N. Verheyen as a subspecies of I. macrotis, a status that it has retained ever since.

So the Idiurus that Durrell encountered in Cameroon during his 1949 expedition there - and documented in a charmingly entitled chapter 'The Forest of Flying Mice' within his book - is nowadays deemed to be a subspecies of Idiurus macrotis, the long-eared flying mouse.

Long-eared flying mouse Idiurus macrotis (Ed Stauffacher/Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopaedia)

Long-eared flying mouse Idiurus macrotis (Ed Stauffacher/Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopaedia)And here is Durrell's description of the very first specimen that he succeeded in capturing:

"He was about the size of a common House Mouse, and very similar to it in general shape. The first thing that caught your attention was his tail: it was very long (almost twice as long as his body), and down each side of it grew a fringe of long, wavy hairs, so the whole tail looked like a bedraggled feather. His head was large, and rather domed, with small, pixie-pointed ears. His eyes were pitch black, small, and rather prominent. His rodent teeth, a pair of great bright orange incisors, protruded from his mouth in a gentle curve, so that from the side it gave him a most extraordinarily supercilious expression. Perhaps the most curious part about him was the 'flying' membrane, which stretched along each side of his body. This was a long, fine flap of skin, which was attached to his ankles, and to a long, slightly curved, cartilaginous shaft that grew out from his arm, just behind the elbow. When at rest, his membrane was curled and rucked along the side of his body like a curtain pelmet; when he launched himself into the air, however, the legs were stretched out straight, and the membrane thus drawn taut, so that it acted like the wings of a glider."

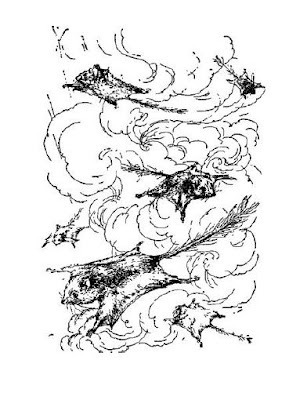

Later on, by smoking a tree containing more Idiurus specimens in the hope of capturing some without harming them, Durrell was able to see these tiny creatures take to the air, and what a remarkable sight it was:

"I have seen some extraordinary sights at one time and another, but the flight of the flying mice I shall remember until my dying day. The great tree was bound round with shifting columns of grey smoke that turned to the most ethereal blue where the great bars of sunlight stabbed through it. Into this the Idiurus launched themselves. They left the trunk of the tree without any apparent effort at jumping; one minute they were clinging spread-eagled to the bark, the next they were in the air. Their tiny legs were stretched out, and the membranes along their sides were taut. They swooped and drifted through the tumbling clouds of smoke with all the assurance and skill of hawking swallows, twisting and banking with incredible skill and apparently little or no movement of the body. This was pure gliding, and what they achieved was astonishing. I saw one leave the trunk of the tree at a height of about thirty feet. He glided across the dell in a straight and steady swoop, and landed on a tree about a hundred and fifty feet away, losing little, if any, height in the process. Others left the trunk of the smoke-enveloped tree and glided round it in a series of diminishing spirals, to land on a portion of the trunk lower down. Some patrolled the tree in a series of S-shaped patterns, doubling back on their tracks with great smoothness and efficiency. Their wonderful ability in the air amazed me, for there was no breeze in the forest to set up the air currents I should have thought essential for such intricate manoeuvring."

Idiurus airborne, as depicted in The Bafut Beagles (Ralph Thompson)

Idiurus airborne, as depicted in The Bafut Beagles (Ralph Thompson)As its common name suggests, a flying mouse does indeed look very murine in general form, because when at rest its gliding membranes are folded up tightly and thus are not readily noticeable (which would explain why Schomburgk never mentioned them). What is noticeable, conversely, as mentioned by Durrell, is its very lengthy, plumed tail, which is so fragile that it could certainly be snapped off if not handled with great care.

Moreover, whereas most scaly-tail species are solitary, those of Idiurus are colonial; indeed, the two Idiurus species have even been found associating together. In 1940, for instance, veteran American cryptozoologist and animal collector Ivan T. Sanderson recorded finding approximately 100 individuals of both Idiurus species living together in the same tree during his participation in the Percy Sladen Expedition to the Mamfe Division of Cameroon.

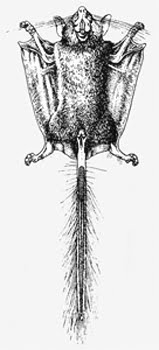

Idiurus ahoy! (Illustration source unknown)

Idiurus ahoy! (Illustration source unknown)Due to their primarily nocturnal lifestyle and highly elusive nature, however, even today the Idiurus scaly-tails remain virtually unknown not only to science but even to local hunters – as Durrell discovered during his Idiurus searches in Cameroon.

In conclusion: as can clearly be seen from the above accounts, the long-eared 'flying mouse' scaly-tail I. macrotis, whose zoogeographical range includes Liberia, so greatly resembles Schomburgk's description of his mysterious Liberian micro-squirrel that there can be little doubt the two mammals are indeed one and the same species – an opinion shared by Markus after I'd informed him of my thoughts concerning this case. Another longstanding if hitherto little-known cryptozoological mystery is duly solved, but many others documented by Schomburgk remain unresolved – for now!

Interestingly, this is not the first time that a scaly-tail has been at the core of a cryptozoological mystery, as ably demonstrated by the remarkable case of Tanzania's flying jackal - which I originally investigated in my book Extraordinary Animals Worldwide (1991) and returned to in its updated edition, Extraordinary Animals Revisited (2007).

Late 19th-Century engraving of a large Anomalurus scaly-tail

Late 19th-Century engraving of a large Anomalurus scaly-tailAs reported by Captain William Hichens in the December 1937 issue of a monthly magazine entitled Discovery, kraalsmen in what was then Tanganyika (now Tanzania) affirmed that an amazing beast known to them as the mlularuka or flying jackal, yet wholly unknown to science at that time, would frequently raid their mango trees and pomegranates during its flights at dusk, and would give voice to loud cries while on the wing. Not surprisingly, their reports were totally disbelieved and dismissed as arrant fantasy - until the ‘flying jackal’ was discovered!

A selection of scaly-tails (Clifford Lees, in A.H. Booth's Small Mammals of West Africa)

A selection of scaly-tails (Clifford Lees, in A.H. Booth's Small Mammals of West Africa)As I learnt from Dr Maria E. Rutzmoser of Harvard University’s Agassiz Museum, in 1926 zoologist Arthur Loveridge was in Tanganyika, collecting specimens for the museum, and at Vituri he succeeded in tracking down the mlularuka, but it was not a flying jackal. Instead, it was a large (2.5-ft-long) form of scaly-tail.

Although well-known in West and Central Africa at that time, their existence in East Africa had not previously been suspected. Consequently, the mlularuka was initially believed to be a new species, but was later shown to be a subspecies of an already wide-ranging species variously called Lord Derby's or Fraser’s scaly-tail Anomalurus derbianus. Hence it is now referred to as A. d. orientalis - a mythical flying jackal that was ultimately unmasked as an aerial squirrel-impersonator!

Lord Derby's (aka Fraser's) scaly-tail (Eveha/Wikipedia)

Lord Derby's (aka Fraser's) scaly-tail (Eveha/Wikipedia)My sincere thanks to Markus Bühler for so generously sharing information from Schomburgk's book with me and also for very kindly supplying me with an English translation of the relevant passage from it concerning the Liberian micro-squirrels.

Published on July 11, 2012 14:10

July 4, 2012

THE OLDEANI MONSTER – HOW I HELPED TO REDISCOVER AND IDENTIFY A LOST SPECIES OF MYSTERY CHAMELEON

Sir Peter Scott's sketch of the Oldeani Monster in his diary (Lady Philippa Scott/Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust)

Sir Peter Scott's sketch of the Oldeani Monster in his diary (Lady Philippa Scott/Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust)To the chagrin of cryptozoologists and the delight of their critics, the conclusive identification of a longstanding mystery beast is not a common occurrence. That is why I have particular pleasure in presenting herewith one such revelation that I was personally able to achieve.

As documented in his Travel Diaries of a Naturalist, Volume One (1983), on 25 February 1962, during a visit to Africa, world-renowned conservationist and naturalist Sir Peter Scott, had set off for Tanzania's Serengeti Plains with companions John and Jane Hunter from their home at Oldeani. They had reached the Ngorongoro Conservation Authority Area when they spied a large, unfamiliar-looking chameleon, crossing the road just beyond the Area's entrance.

Somewhat elongate in shape with a very lengthy tail, and a tiny horn at the tip of its snout, this mysterious lizard - probably a male and later nicknamed the Oldeani Monster - was brown in basic colour, with small red spots and a distinctive horizontal stripe running across the center of each flank.

The Oldeani Monster (Lady Philippa Scott/Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust)

The Oldeani Monster (Lady Philippa Scott/Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust)Scott was so intrigued that he picked up this 'monster' - which promptly attempted to bite him! Undeterred, he took it back home with him when he returned to England, where it lived for 18 months at his famous Wildfowl Trust (now the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust) at Slimbridge in Gloucestershire. When it died, its body was preserved and Scott referred it to several herpetological experts in the hope of identifying its species - but no-one could offer a satisfactory answer.

One authority suggested that it may actually be a female, not a male, and related to Chamaeleo [now Trioceros] jacksonii merumontanus - a subspecies of Jackson's distinctly dragonesque three-horned chameleon confined solely to Tanzania's Mount Meru.

Jackson's three-horned chameleon (Wikipedia)

Jackson's three-horned chameleon (Wikipedia)Another expert considered the possibility that it was a juvenile of an extremely sizeable species called Meller's chameleon C. [now T.] melleri (mainland Africa's largest species of chameleon), but this was later disproved.

Meller's chameleon (Wikipedia)

Meller's chameleon (Wikipedia)Scott himself was inclined to believe that it belonged to a hitherto-undescribed species, and even proposed 'Chamaeleo oldeanii' as a suitable name.

Tragically, however, the bottle containing the earthly remains of the obscure Oldeani Monster was eventually lost, possibly destroyed inadvertently. Consequently, it seemed as if the mystery of its identity could never now be solved.

At the beginning of 1991, however, after reading Scott's diary account of it and viewing his accompanying painting (see this ShukerNature blog post's opening illustration), I became very interested in the Oldeani Monster. So I set about seeking an answer to this longstanding riddle myself.

The Oldeani Monster at Slimbridge (Lady Philippa Scott/Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust)

The Oldeani Monster at Slimbridge (Lady Philippa Scott/Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust)First of all, I sent details of its history to herpetologist Colin McCarthy at London's Natural History Museum. In response, I learnt from him that the expert who had nominated C. [now T.] jacksonii merumontanus as a likely identity for this specimen was chameleon specialist Dr Dick Hillenius, at Amsterdam University's Institute For Taxonomic Zoology, who had seen some colour transparencies of the Oldeani Monster sent by Scott to the Natural History Museum in April 1983.

I then contacted Scott's widow, Lady Philippa Scott, who confirmed that the Oldeani Monster's remains had never been found again, but she did have some colour transparencies of it (copies of which she kindly made available to me for credited inclusion in any of my publications). She also commented that it had seemed very similar to the two-banded chameleon C. [now T.] bitaeniatus.

Two-banded chameleon

Two-banded chameleon(http://www.freewebs.com/robin_reptile...)

In November 1991, after reading a cryptozoological article by him in the periodical Tier und Museum, I wrote to German herpetologist Dr Wolfgang Böhme, who has a great interest in mystery reptiles. Indeed, he is famous for unveiling a hitherto-unknown species of monitor lizard, now known as the Yemen monitor Varanus yemenensis, while in the comfort of his own home! Viewing a TV documentary concerning Yemen one evening in 1985, he spotted a strange-looking monitor in it - his subsequent investigations confirmed that its species was totally new to science. (See my book The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals , 2012, for full details regarding this remarkable herpetological find.)

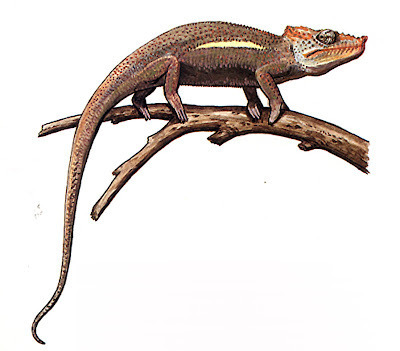

And now, after reading my letter (which also contained copies of Lady Scott's transparencies), the mystery of the Oldeani Monster was a mystery no longer either. Dr Böhme recognized its species immediately, naming it as Bradypodion uthmoelleri – known variously as Müller's leaf chameleon and the Hanang hornless chameleon. Moreover, in an issue of the weekly journal Salamandra (15 December 1990), he had actually published a paper dealing with this latter lizard. It is an exceedingly rare species, which was formally described by science in 1938, but as recently as 1990 was known from just three specimens - the latest of these constituting the first recorded female, collected from the Ngorongoro crater.

Müller's leaf chameleon (http://www.leoleocf.com)

Müller's leaf chameleon (http://www.leoleocf.com)Happily, my own interest in the Oldeani Monster had forged the vital link between two discrete parties with complementary information. Namely, Lady Scott, with firsthand knowledge of the Oldeani Monster, but not of B. uthmoelleri or Dr Böhme's paper; and Dr Böhme, with firsthand knowledge of B. uthmoelleri, but not of the Oldeani Monster – which constituted a previously unrecognized, fourth specimen of this reclusive species.

After almost three decades, the remains of the Oldeani monster could at last rest in peace - wherever they are.

About a year ago, an unexpected but very pleasant postscript to this interesting history occurred, when, while browsing at a book fair, I came upon a copy of a book by Lady Scott that I hadn't seen before. Published in 2002, it was entitled So Many Sunlit Hours, and recalled many of the adventures that she had shared over the years with her husband, travelling the world in search of rare and exotic species to film, paint, and assist in conserving for future generations.

So Many Sunlit Hours

So Many Sunlit HoursOpening it, I was surprised but delighted to find that it was personally signed by her, and so I purchased it without delay. Later, reading through a chapter documenting their sojourns through Africa, I was even more surprised and delighted, as well as very honoured, to discover the following paragraph:

"The chameleon that we had caught above the crater turned out to be extremely interesting. We named it the 'Oldeani Monster' after the area where it was found. It was not as easily tamed and handled as the other two species we had – Ch jackson [sic] and Ch bitaeniatus – hence the additional name 'Monster'. Some years later, thanks to the excellent painting of it in Peter's diary, it was recognised by Dr Schukker [sic] as the rare Bradypodion uthmoelleri."

Sadly, Lady Scott had died in January 2010, at least 18 months before I had happened upon her book, so I never had the opportunity to thank her for her kind acknowledgement of my investigations – until now. Thank you so much, I am truly grateful and very pleased that I was able to shed some light upon the longstanding mystery of your fascinating little Monster's zoological identity.

I also wish to offer my sincere thanks to Lady Scott for so kindly granting me her permission in perpetuity to reproduce in suitably credited form the three Oldeani Monster illustrations supplied to me by her and included in this present ShukerNature blog post.

Incidentally, in 2006 the Oldeani Monster's species was transferred to a newly-created genus, Kinyongia, so its taxonomic name is now Kinyongia uthmoelleri. Since its rediscovery, moreover, via the Oldeani Monster, this species has been maintained and bred in captivity, so its survival now seems much more assured.

This ShukerNature blog post is an expanded, updated version of a section from my book From Flying Toads To Snakes With Wings (Llewellyn: St Paul, 1997).

Published on July 04, 2012 16:45

July 1, 2012

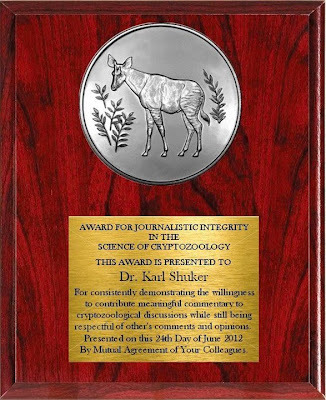

AN HONOUR MOST GRACIOUSLY BESTOWED AND VERY GRATEFULLY RECEIVED

I am extremely proud to have received this award, which was devised by fellow cryptozoological writer/researcher Randy Merrill, and Liked on Facebook by so many other kindred spirits. Thank you all most sincerely - I very greatly appreciate it!

Published on July 01, 2012 16:46

June 26, 2012

THE PARK OF THE MONSTERS - RENAISSANCE GARDEN FOR A GORGON

A colossal winged siren of stone at Bomarzo's astonishing Park of the Monsters (Burningmax/Flickr)

A colossal winged siren of stone at Bomarzo's astonishing Park of the Monsters (Burningmax/Flickr)Several years ago, while browsing through a series of bookstalls in the indoor market of Bridgnorth, a town in Shropshire, England, I came upon a hardback travelogue book, dating from around the 1950s/early 1960s as far as I can recall, in which the writer described various sights that he had visited during his journeys around Europe (and possibly elsewhere). One chapter particularly interested me, as it described an extraordinary park located somewhere in continental Europe that was filled with huge, grotesque stone statues of monsters and other bizarre entities, but which had long since been abandoned and was now exceedingly overgrown, heightening its nightmarish aspect.

The face of Proteus, Park of the Monsters (Alessio Damato/Wikipedia)

The face of Proteus, Park of the Monsters (Alessio Damato/Wikipedia)Normally, anything as unusual as like this would have been enough for me to have purchased the book without hesitation, so I still don't understand why I didn't do so on this particular occasion. To make matters worse, I never even took notice of the book's title or author (I can only assume that I must have had other, more pressing matters on my mind that day!). As always happens in such a situation, of course, I later regretted not purchasing the book and resolved to do so when I was next in Bridgnorth (a town I often visit), but, as again always happens, when I did return, the book was gone, and the book stalls' owner did not even remember it.

A grim Janus-faced column in the Park of the Monsters (Burningmanx/Flickr)

A grim Janus-faced column in the Park of the Monsters (Burningmanx/Flickr)Not long afterwards, moreover, he moved out of the market altogether, presumably selling his stock or taking it to set up elsewhere. So any chance of painstakingly going through all of his many books there in case it had been mis-shelved was gone too.

Neptune/Poseidon (Alessio Damato/Wikipedia)

Neptune/Poseidon (Alessio Damato/Wikipedia)Recently, recalling to mind that long-vanished book, I decided to see if I could discover any information online that may identify the mysterious garden of monsters that it had documented, and, happily, I succeeded! So here is what I found out:

One of the most spectacular works of Renaissance art can be found in one of Europe's strangest gardens. Dubbed the world's first theme park by some, it may be Renaissance by date but in appearance and content it is decidedly gothic. For although its official name is the Garden of Bomarzo (situated in Viterbo, northern Lazio, in Italy), it is most commonly referred to – and for very good reason – as the Park of the Monsters.

A moss-covered Pegasus fountain (Alessio Damato/Wikipedia)

A moss-covered Pegasus fountain (Alessio Damato/Wikipedia)It was created during the 16th Century by Duke Pier Francesco 'Vicino' Orsini (1528-1588), an ex-military officer who was also a leading patron of the arts, and devoted to his wife, Guilia Farnese. When she died, he established the garden (which he called his Sacred Grove) in tribute to her. It consisted originally of a wooded park at the bottom of a deep valley overlooked by Orsini's castle, but he then commissioned the sculpting of a host of arcane gargantuan statues to populate it, some hewn directly from the valley's natural bedrock, and many representing terrifying monsters or other figures from classical Greek mythology. More than two dozen were completed, plus various smaller exhibits such as a temple.

Cerberus, Greek mythology's triple-headed hound of hell (Burningmax/Flickr)

Cerberus, Greek mythology's triple-headed hound of hell (Burningmax/Flickr)These awe-inspiring but very macabre stone colossi included Cerberus the three-headed hound of Hades, two mermaid-like sirens, a Pegasus fountain, a scarcely-attired reclining nymph, Neptune/Poseidon, the goddess Aphrodite, a giant (possibly Heracles) sculpted in the act of ripping apart another giant (Cacus?), the shape-shifting marine deity Proteus, and a winged woman sitting upon a vast tortoise.

A giant savagely dispatching his enemy in mortal combat ((Alessio Damato/Wikipedia)

A giant savagely dispatching his enemy in mortal combat ((Alessio Damato/Wikipedia)Also present was the bizarre Mouth of Hell – the screaming face of a hideous ogre, whose mouth was a grotto big enough for people to walk through, and inscribed with the words "All reason departs".

The Mouth of Hell ((Alessio Damato/Wikipedia)

The Mouth of Hell ((Alessio Damato/Wikipedia)Assorted animals included a bear, a whale, and a war elephant of the Carthaginian general Hannibal (carrying a trampled Roman soldier in its great trunk).

War elephant gripping the soldier's dead body (Alessio Damato/Wikipedia)

War elephant gripping the soldier's dead body (Alessio Damato/Wikipedia)Perhaps the most outstanding example of Orsini's bizarre statuary, however, was a stupendous sculpture of a winged classical dragon, crouching at bay with jaws open wide as it battled a dog (symbolising spring), a lion (summer), and a wolf (winter).

Bomarzo's great stone dragon battling a dog, lion, and wolf (Alessio Damato/Wikipedia)

Bomarzo's great stone dragon battling a dog, lion, and wolf (Alessio Damato/Wikipedia)Placed in an apparently random manner within the park, these daunting goliaths astonished all who saw them, but some felt that their grotesque, melancholic forms and erratic distribution mirrored Orsini's anguished, deranged state of mind resulting from his wife's death. There is controversy as to who designed and prepared the statues. Some experts attribute them to the acclaimed architect Pirro Ligorio. Others support claims that it was none other than Michelangelo who designed these great works, with some of his most talented students sculpting them. A third school of thought suggests that a team of prisoners of war awarded to the duke was responsible.

Siren and two lions (Samuele Ghilardi/Flickr)

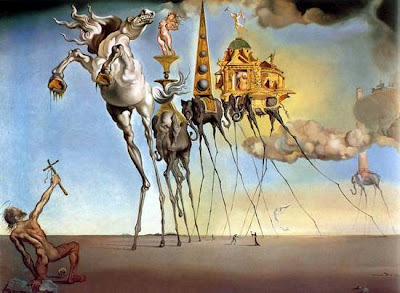

Siren and two lions (Samuele Ghilardi/Flickr)Following his death, this nightmarish park was gradually abandoned, falling into an eerie state of disrepair, until by the 1800s many of the figures had become virtually hidden within a veritable jungle of overgrown vegetation and unchecked foliage. Orsini's forgotten menagerie of immense megaliths remained neglected and unvisited by all but vagrants and ne'er-do-wells (plus Salvador Dali in 1938, a visit that inspired his 1946 painting 'The Temptation of St Anthony') until as recently as 1970. This was when a successful restoration was initiated by the Bettini family owning the land containing this most surreal of gardens.

'The Temptation of St Anthony' (Salvador Dali)

'The Temptation of St Anthony' (Salvador Dali)Today, the Park of the Monsters is a major tourist attraction. Countless visitors wander now through its shadowy realm to encounter its frozen fauna of horror, where Orsini's dragon, winged steed, triple-headed hell hound, and all of his other weird figures stand forever in stony silence, as if the very gorgon Medusa had cast her evil gaze of petrification upon their grim gathering.

View from inside the Park of the Monsters, featuring the Carthaginian war elephant (Gabriele Delhy/Wikipedia)

View from inside the Park of the Monsters, featuring the Carthaginian war elephant (Gabriele Delhy/Wikipedia)And yes, just in case you're wondering, Italy's Park of the Monsters is definitely on my list of places to visit in the not-too-distant future – so watch this space for plenty of additional information and all-new photographs!

Reclining nymph (Burningmax/Flickr)

Reclining nymph (Burningmax/Flickr)

Published on June 26, 2012 12:31

June 25, 2012

GOODBYE, LONESOME GEORGE - R.I.P. THE PINTA ISLAND GIANT TORTOISE

Lonesome George (Cryptomundo)

Lonesome George (Cryptomundo)It is rare indeed for the precise date of extinction of a species or subspecies to be known, but there are a few notable examples. 1 September 1914 marked the death of the world's last known passenger pigeon Ectopistes migratorius (in Cincinnati Zoo); 21 February 1918 saw the death of the last verified Carolina parakeet Conuropsis carolinensis (also, remarkably, in Cincinnati Zoo); and on 7 September 1936 the last confirmed specimen of the Tasmanian wolf Thylacinus cynocephalus died (in Hobart Zoo). Now, tragically, we can add another black day to that list - 24 June 2012, the day when Lonesome George, the world's only known surviving Pinta Island giant tortoise, died. He was approximately 100 years old, and, with ironic inevitability, he was alone when death finally releaased him from decades of isolation from any other member of his subspecies.

Lonesome George's biography

Lonesome George's biographyHere, as a tribute to Lonesome George, is my documentation of his sad story and that of his entire race, which appeared in my recently-published book, The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals (2012):

The South American Galapagos archipelago is named after its giant tortoise Chelonoidis nigra (formerly known as Geochelone elephantopus); 'galapagar' is Spanish for 'a place where tortoises thrive'. An imposing sight, weighing in at a hefty 330-440 lb, and with a burly carapace (shell) at least 3.5 ft long, it once existed on no fewer than 11 of the islands, and occurred in so great a variety of shell shapes that it was once split into at least 15 different species. On some islands, its carapace was domed (as in smaller tortoises), on others it was flattened like a saddle. The largest island, Albemarle (also called Isabella), had five species, and ten other islands each had one; but nowadays these are all treated merely as distinctive subspecies of a single species.

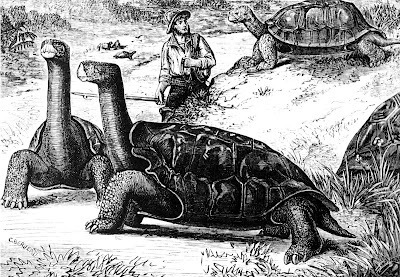

19th-Century engraving of Abingdon (Pinta) Island giant tortoises

19th-Century engraving of Abingdon (Pinta) Island giant tortoisesRegardless of their shell shapes, however, all of the islands' giant tortoises were united by at least one shared feature - a feature that proved to be their undoing. Their flesh was extremely tasty - prompting their slaughter en masse during the early 1800s by visiting sailors, whalers, and other seafarers, until several subspecies were exterminated.

One of the most distinctive was the saddle-shelled form on Abingdon (Pinta) Island, C. n. abingdoni, whose carapace was unusually thin. By the 20th century's opening years, its population had virtually disappeared, and during scientific expeditions to Abingdon in the 1930s and 1950s not a single specimen was observed (though it is now known that local fishermen found and slaughtered some for meat in the early 1950s). To make matters even worse, goats were introduced onto the island from 1954 onwards, whose insatiable appetites soon converted its all-too-small covering of foliage into an arid wilderness. Not surprisingly, the Abingdon Island giant tortoise was written off as extinct, but in 1964 no fewer than 28 dead specimens were discovered there. They appeared to have died about five years before, which meant that they must have been alive, but concealed, during the earlier searches. Even so, 28 dead specimens could hardly resurrect their subspecies from extinction.

An Abingdon (Pinta) Island giant tortoise exhibited at London Zoo in 1914

An Abingdon (Pinta) Island giant tortoise exhibited at London Zoo in 1914Nevertheless, it was resurrected in March 1972, for this was when - to the astonishment of herpetologists everywhere - a living specimen was encountered on Abingdon. Furthermore, tracks indicating the presence of others were also sighted. The live tortoise, a male (later christened Lonesome George), was swiftly transferred to the Charles Darwin Research Station on Santa Cruz for security. Still alive today (August 2011), George is believed to be 60-90 years old and in good health, but attempts to mate him with females of other Galapagos subspecies in order to preserve his genes in future generations of hybrids has so far proven unsuccessful.

Meanwhile, no other living pure-bred Abingdon giant tortoise has been found on Abingdon since the discovery there of George. Nor have any been confirmed existing in any zoo or private collection (although as first publicised in 2006, there is a possible pure-bred adult male, Tony, living at a Prague zoo, whose taxonomic identity is now under close investigation). However, in view of the tracks observed, it seems remotely feasible that specimens do still survive on Abingdon - a possibility reinforced in 1981 by the discovery on this island of some tortoise faecal droppings that appeared to be no more than a few years old. To encourage searches, a reward of $10,000 is being offered by the Charles Darwin Research Station to anyone who successfully discovers a living female Abingdon Island giant tortoise.

Sadly, any such find will now be too late for Lonesome George. However, it would resurrect his subspecies from extinction, so for that reason alone, the search must continue, in the memory of the Pinta Island giant tortoise's most prominent and poignant ambassador.

Lonesome George (Putneymark/Wikipedia)

Lonesome George (Putneymark/Wikipedia)

Published on June 25, 2012 09:38

June 21, 2012

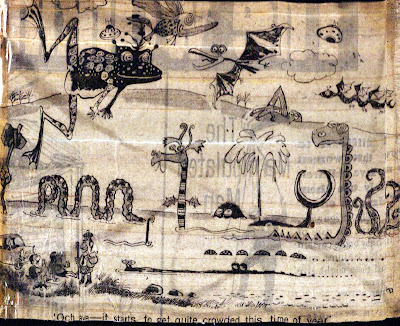

NESSIE AND THE NEWSPAPER CARTOON – IN SEARCH OF ITS SOURCE

The very considerable cryptozoological archives that I have amassed over many years of research began long ago with a series of humble little scrapbooks of interesting animal-related newspaper cuttings and magazine articles that I compiled as a child. Sadly, my enthusiasm for collecting and preserving these items was not matched at that tender age with the realisation that to render them of scientific worth I should also be noting down their source and date of publication. Happily, I have since been able to trace the relevant details for many of them, but not all...

One item that falls into that latter, still-unsourced category is the wonderful Loch Ness Monster-themed newspaper cartoon appearing in this present ShukerNature blog. All that I can recall about it is that it was published during a flurry of media-hyped Nessie activity during the early 1970s, and probably appeared in either the Daily Mirror or the Sun. These are two British tabloid newspapers which, among a wide range of other newspapers (tabloids, broadsheets, nationals, locals, dailies, Sundays), my parents read at that time (however, the cartoon's style and format do not match those of any of their other purchased newspapers from that same period). So if anyone happens to know the newspaper in which this cartoon appeared and/or the date on which it was published, I'd greatly welcome any details.

Incidentally, please forgive the poor quality of my photograph of it – but as this cutting is now roughly 40 years old, it has become somewhat yellowed and extremely tattered round the edges. Nevertheless, I am delighted to have it still, as it remains my all-time favourite cryptozoologically-themed newspaper cartoon.

Published on June 21, 2012 12:41

June 18, 2012

THE DAY I SAW A UNICORN ON SAFARI

Behold, the unicorn! (Dr Karl Shuker)

Behold, the unicorn! (Dr Karl Shuker)The last thing that I expected to see when visiting the West Midlands Safari Park last summer was a unicorn – but that is exactly what I did see there...well, sort of.

I've frequently read in accounts of unicorns the theory that some reported sightings were nothing more than long-horned antelopes viewed side-on, so that their two horns perfectly overlapped, creating the illusion of a single centrally-horned unicorn. And I admit that I've always tended to think "Yeah, right, I'll believe that when I see it". Well now I do, because I have – and here's the proof!

Driving through one of the ungulate paddocks at the safari park, I came upon an addax Addax nasomaculatus resting on the ground with head raised, the two spiralled horns of this pale Sahara Desert antelope perfectly discernible as I photographed it.

Before... (Dr Karl Shuker)

Before... (Dr Karl Shuker)And then, suddenly, it turned sideways slightly, as I was still photographing it, and there – only for a split second, but right before my astonished eyes – was a unicorn!

During... (Dr Karl Shuker)

During... (Dr Karl Shuker)A momentary metamorphosis, from a commonplace antelope of reality to a wondrous beast of legend. And then, it moved its head just a fraction – and the spell was broken, the illusion dispelled. The unicorn was gone, as if it had never been, and the addax had returned, wholly unaware of the magical presence that it had conjured forth.

After... (Dr Karl Shuker)

After... (Dr Karl Shuker)But my camera had recorded its transient alter ego – a single wonderful photograph of a modern-day marvel, a unicorn beheld and bedazzling. And what more fitting animal to have evanescently assumed this fairest of forms than the white-coated, spiralled-horned addax?

I felt strangely blessed as I continued upon my safari journey, the image of the unicorn that never was, almost was, and truly was, if but for the most fleeting of instants, still alive and entrancing within the shadowed glades of my memory.

The full sequence of addax-unicorn-addax transformation (Dr Karl Shuker)

The full sequence of addax-unicorn-addax transformation (Dr Karl Shuker)Worth noting, incidentally, is that not all unicorn reports described the horn as pointing forwards – some claimed that it was directed backwards - as with, for instance, the desert-dwelling black-horned karkadann of Persia. Similarly, there are several different descriptions relating to its horn's supposed colour – white, black, red, and even all three together!

Two different karkadann depictions

Two different karkadann depictionsFor further information concerning the history and surprising diversity of unicorns, see my book Dr Shuker's Casebook (CFZ Press: Bideford, 2008).

Published on June 18, 2012 06:45

June 15, 2012

FLOWER-GENERATED BIRDS, AND TURTLES THAT FLY

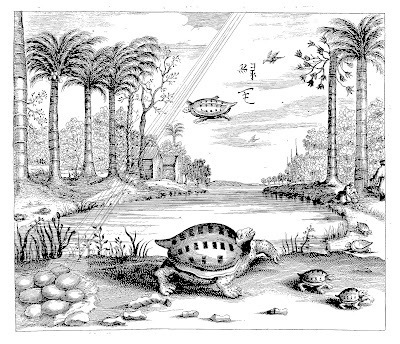

Flying turtles illustration from Athanasius Kircher's tome China Illustrata (1667) [note also the flying dragon in the background!]

Flying turtles illustration from Athanasius Kircher's tome China Illustrata (1667) [note also the flying dragon in the background!]How often is it that when pursuing one line of investigation, a second, wholly unrelated but equally interesting one presents itself and is so captivating that to ignore it would be entirely futile?

So it was when I began to seek out information concerning a truly extraordinary illustration of supposed flying turtles native to Henan in China, which appeared in German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher's tome China Illustrata (1667). Or, to give it its full title, China monumentis, qua sacris qua profanis, nec non variis naturae and artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabilium argumentis illustrata.

Athanasius Kircher (1601/1602-1680)

Athanasius Kircher (1601/1602-1680)On 15 June 2012, I had received via a clickable link placed upon my Facebook wall by New Jersey-based colleague Robert Schneck a copy of this illustration, and as I could think of few creatures less likely to have acquired a mastery of the air than a turtle, I was naturally perplexed and piqued by curiosity in equal measures. China Illustrata had originally been published in Latin, but browsing online I soon discovered an English translation of it, and sure enough, there inside I found not only the illustration but also an explanation of it by Kircher.

But before I reveal just what that explanation was, I'd like to digress for a while if I may, in order to document a separate but equally memorable entry that I chanced upon in Kircher's selfsame tome, and which shone some very welcome light upon a riddle of Nature that until then had long mystified me.

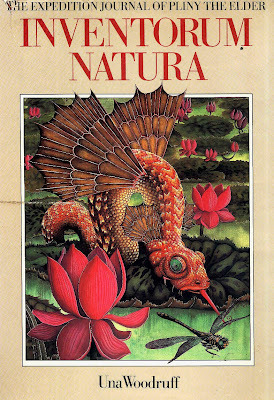

Within my library are quite a few delightful works of what I refer to as pseudozoology. Most of these are large, lavishly-illustrated books purporting to be republished tomes of arcane natural history, but which upon reading are swiftly recognised as adroitly-constructed fiction penned with tongue very firmly in cheek. An excellent example of this highly-specialised genre is a truly spectacular tome entitled Inventorum Natura: The Expedition Journal of Pliny the Elder (1979), compiled and exquisitely illustrated by celebrated fantasy writer-artist Una Woodruff.

Inventorum Natura: The Expedition Journal of Pliny the Elder (1979) by Una Woodruff.

Inventorum Natura: The Expedition Journal of Pliny the Elder (1979) by Una Woodruff.The premise behind this very elaborate and skilfully-prepared volume is that it is a painstaking reconstruction of a supposedly long-lost work written in Latin by the real-life Roman author-naturalist Pliny the Elder (who died during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD), describing the astonishing fauna and flora that he allegedly observed during a purported three-year expedition to distant lands, an incomplete version of which Woodruff happened to rediscover. The creatures documented in it include many famous legendary beasts, including the basilisk, manticore, unicorn, Eastern dragon, griffin, hydra, vegetable lamb or barometz, Chinese hua fish (depicted on the book's front cover), merman, and Western dragon. However, it also included a few examples that I had never read anything about elsewhere, so I wondered whether these may have been specially created for this book.

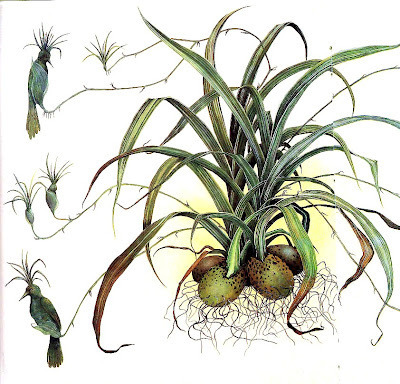

One of them was the bird plant, which according to Inventorum Natura was a variety of grass native to mainland Asia whose flowers transformed into small brightly coloured birds. The accompanying double-spread illustration (part of which is reproduced here) revealed how these flowers gradually metamorphosed into birds, which eventually broke free of the plant's flower stems to become independent, free-flying entities comparable in every way externally to genuine egg-hatched birds but remaining wholly botanical internally.

The bird plant (Una Woodruff, in Inventorum Natura)

The bird plant (Una Woodruff, in Inventorum Natura)Until Robert's link containing Kircher's flying turtle illustration appeared on my Facebook wall, I had all but forgotten the bird plant, but while perusing Kircher's China Illustrata, I was startled yet delighted to discover the following highly illuminating section:

"In Suchuen [sic – Sichuan] Province there is said to be a little bird which is born from the flower called Tunchon, and so the Chinese call it Tunchonfung. The Chinese say that this measures its life by the life of the flower, and that flower and bird die at the same time. The bird has a variety of colours. When flying and beating its wings, the bird looks like a beautiful flower flying across the heavens. Whether an animal, bird, or insect could really be produced from a plant is doubtful. We have denied this in Book Twelve of our Subterranean World. It is not possible for the vegetable level of nature to progress to the sentient, since it is impossible to skip a level in nature and produce an effect inconsonant with one's own nature. I think it would be possible for these birds' eggs, which are no larger than peas, to be laid in the pods or leaves, or to be deposited on the flowers. A flying creature might seem to be born like a flower, if the egg were broken and the seed of the bird were mixed with the moisture of the flower. Also, if a person with a vivid imagination gazes at the variety of the colours of flowers, the fantastic colours of the birds' wings might seem to be derived from the flowers. This can even be frequently seen in Europe."

Clearly, therefore, there is indeed a genuine tradition of belief, albeit one founded upon a fallacy, that small birds can be generated from flowers. Sadly, there are insufficient details to identify either the tunchon or the tunchonfung with any degree of certainty, although it is possible that the latter is a species of sunbird (nectariniid). Native to Africa, Asia (including China's Sichuan Province), and Australasia, sunbirds are small, extremely brightly coloured, and mirror ecologically albeit not taxonomically the New World hummingbirds.

Sunbird alongside a bird of paradise flower (Public domain)

Sunbird alongside a bird of paradise flower (Public domain)But what about China's supposed flying turtles – did I find anything about them in Kircher's tome too? Indeed I did. Accompanying the illustration that initiated everything documented here was the following information:

"The Chinese Flora says that in the kingdom of Honan [=Henan, nowadays a province in central China] are found turtles which are green or blue, and that there are also some with wings on their feet, who in this way they compensate for the slow progress they can make on foot. I, however, could not easily believe that these swimming creatures have wings, for it seems to violate the primary nature of a turtle. Rather, turtles give off a sticky liquid around their feet, as the drawing shows, and in time this becomes cartilaginous and resembles a limb which flaps around as they move. This is not used for flying, so when the matter is examined, it turns out to be different than is commonly believed."

The Chinese Flora referred to above by Kircher was Flora Sinensis (1656), authored by Polish Jesuit missionary Michael Boym. It was one of the first European books ever to have been written about China's natural history; despite its title, it included information concerning a number of animals as well as plants.

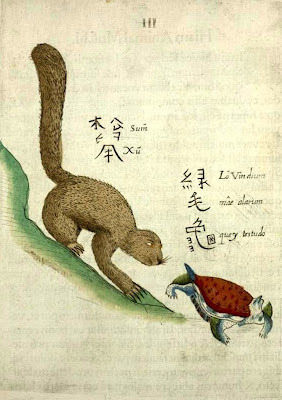

Illustration of squirrel chasing turtle from

Flora Sinensis

Illustration of squirrel chasing turtle from

Flora SinensisAs for China's flying turtles: here was a situation where one mystery appeared to have been solved only by the citing of another one, because the notion of turtles' feet secreting a sticky substance that hardens to yield flapping quasi-wings was certainly new to me. Happily, however, at the very same time that I was pondering this riddle, a second Facebook-mediated message was winging its way to me from Robert Schneck. And in this latter one, Robert informed me that according to his own investigations, Kircher's documentation of a supposed Chinese belief in flying turtles was an error caused by mistranslation of Chinese sources. What these had actually referred to were turtles with moss or weeds growing upon their limbs, but unfortunately this had been mistranslated by Kircher (or by earlier non-Chinese works that he had directly consulted), yielding turtles with wings on their limbs instead.

In short, another seemingly impossible beast had been unmasked as entirely plausible after all, albeit very different in form from how it had originally been described. Never mind. The flying turtles of Henan may never have existed, but at least they inspired a delightful illustration, one that also serves as a very evocative reminder of the perils of mistranslation – or, how Chinese whispers can engender Chinese flying turtles!

My sincere thanks to Robert Schneck for bringing to my attention the enigma of Henan's flying turtles and, by doing so, also assisting me in resolving a second mystery of unnatural history – by enabling me to uncover a factual origin for the bird plant fallacy.

Published on June 15, 2012 19:05

June 12, 2012

BLACK LIONS - MANIPULATION, MELANISM, AND MOZAICISM

Photoshopped black lion #1 (tumblr.com)

Photoshopped black lion #1 (tumblr.com)In recent weeks, two very stunning black lion photographs have been circulating online. One of them is the picture above, opening this ShukerNature blog post, and the other one is documented further down in it. Why they attracted such interest is that according to mainstream zoology, black lions simply do not exist. If they did, and were wholly black in colour, they would most probably be melanistic specimens, analogous if not homologous genetically with black panthers (melanistic leopards) and mutant all-black individuals of other felid species.

Sadly, for those hoping that these two photos therefore represented some major cryptozoological discovery, the reality, as is true ever more frequently nowadays, is that they are nothing more than Photoshopped images.

I traced Photo #1 (above) to the following specific link: http://24.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_m4qd4hvuEr1rv9dvno1_400.jpg (on the following site: martincito1.tumblr.com – which has now vanished!), but I have no idea whether martincito1 created it, or simply added it from elsewhere to their galleries of images there. However, it is unmistakeably a product of photomanipulation, because I also traced the original photo that had been used – depicting a normal tawny lion photographed in Namibia and present on the Leopalmerphotography website (it can be accessed at http://www.leopalmerphotography.co.uk/male%20lion.jpg).

Photoshopped black lion Photo #1 alongside the original Leopalmerphotography photo that the unknown photomanipulator has used to create it (tumblr.com/Leopalmerphotography.co.uk)

Photoshopped black lion Photo #1 alongside the original Leopalmerphotography photo that the unknown photomanipulator has used to create it (tumblr.com/Leopalmerphotography.co.uk)As for Photo #2 (below):

Photoshopped black lion #2 (PAulie-SVK/deviantART.com)

Photoshopped black lion #2 (PAulie-SVK/deviantART.com)This is actually a photograph of a bona fide exotic lion – namely, a white lion – that has been skilfully converted digitally into a black one (I discovered the original photo on the following site http://www.cutehomepets.com/the-white-lion). Moreover, as I learnt when he kindly posted details upon my Facebook wall on 10 June, cryptozoological colleague Mike Covell successfully traced Photo #2 to digital artist PAulie-SVK, who had created it and placed it in one of their galleries on the deviantART.com site, after which it had been posted elsewhere online by persons unknown wrongly assuming it to be a genuine specimen. (Here is the specific page: http://paulie-svk.deviantart.com/art/Black-Melanistic-Lion-292088989)

Photoshopped black lion #2 (PAulie-SVK/deviantART.com) with original white lion photograph beneath it (cutehomepets.com)

Photoshopped black lion #2 (PAulie-SVK/deviantART.com) with original white lion photograph beneath it (cutehomepets.com)A third online image of a black lion, see Photo #3 (below), is another Photoshopped black lion by PAulie-SVK (this time manipulating an image of a normal tawny lion), produced in wallpaper format (available here: http://paulie-svk.deviantart.com/art/Black-Lion-wallpaper-306684136)

Photoshopped black lion #3 (PAulie-SVK/deviantART.com)

Photoshopped black lion #3 (PAulie-SVK/deviantART.com)But what about real black lions? What do we know of such ebony-furred enigmas? As already noted, no confirmed sightings exist and only a few sparse, unconfirmed reports, most of which I summarised as follows in my book Mystery Cats of the World (1989):

"According to W.L. Speight, in 1940, an experienced game warden once stated that he had spied a whole pride of pitch-black lions in the Kruger National Park. Half a century earlier, a very dark brown specimen had been killed by soldiers of the Luristan Regiment and was seen by archaeologist Sir Henry Layard at Ispahan in what is now Iran. And an account of a black lioness observed at very close quarters was included in Okavango, by June Kay."

Additionally, in a letter of 20 January 1980 to American cryptozoologist Loren Coleman (who has kindly shared its contents with me), wild cats author C.A.W. Guggisberg stated:

"While there are black leopards in the Aberdares, there never was any talk of black lions. A few years ago a rumour went round that black lion cubs were seen somewhere in western Tanzania, but this was never confirmed."

More recently, media reports emanating from South Africa in 2008 carried bizarre stories of big black lions that had allegedly escaped from the Kruger National Park and were now roaming the streets of Matsulu township outside the Mpumalanga capital, terrifying residents who claimed that they were too afraid to walk outside at night. No tangible evidence for their presence was produced, however, and even if lions were genuinely on the prowl there, they may well have simply been dark brown individuals, or normal lions that had rolled in black mud (like the specimens lately photographed at Madikwe, Tanzania, by Grant Marcus – click here http://www.grantmarcus.com/?p=670 to access his website with some superb photos of them). They might even have been nothing more remarkable than ordinary lions glimpsed at night, or during the day but with bright sunlight behind them.

Lion covered in black mud (Gerry van der Walt)

Lion covered in black mud (Gerry van der Walt)In 1975, at Glasgow (formerly Calder Park) Zoo in Scotland, a lion cub named Ranger was born with a black chest and one black leg. This was possibly an example of mozaicism – the development of fixed, irregular patches of pigment on an individual’s body – as these patches never expanded into other areas. Richard O’Grady, the zoo’s director, planned to breed Ranger when old enough with his mother, Kara, in the hope of producing an all-black specimen, but as I learnt from Richard, although such matings did occur on several occasions, no offspring resulted, even though Ranger and Kara were both in excellent health. Ranger was also mated with other lionesses, but always with the same non-result, suggesting that he may have been sterile. Ranger was euthanased in 1997.

Ranger as a cub with his mother Kara (Richard O'Grady/Zoological Society of Glasgow & West of Scotland)

Ranger as a cub with his mother Kara (Richard O'Grady/Zoological Society of Glasgow & West of Scotland)Finally: Before leaving the subject of black lions, it should be explained that the so-called 'black lion' that Marco Polo claimed to have spied in Kollam, India, during his alleged travels in Asia was actually nothing more than a melanistic leopard!

Published on June 12, 2012 15:42

Karl Shuker's Blog

- Karl Shuker's profile

- 45 followers

Karl Shuker isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.