Karl Shuker's Blog, page 62

August 18, 2012

THE AFRICAN CRESTED RAT - KICKING UP A STINK OVER SKUNK IMPERSONATION

19th-Century colour painting of the type specimen of one of Africa's most amazing rodents - Lophiomys imhausi, the African crested (maned) rat

19th-Century colour painting of the type specimen of one of Africa's most amazing rodents - Lophiomys imhausi, the African crested (maned) ratEveryone thinks that their pet is special, but the following one really was, at least as far as cryptozoology is concerned - because it became the type specimen of a species of rodent hitherto unknown to science but which was so dramatic in form that an entirely new taxonomic family was created in order to accommodate it. And the name of this radical rodent? The African crested rat, also known as the maned rat, whose remarkable nature is not confined to its appearance but also embraces an equally extraordinary talent for interspecific impersonation. Intrigued? Then read on...

Returning home to Europe in 1866 after spending some time on the Mascarene island of Reunion, traveller M. Imhaus stopped off at Aden for a few hours. While there he met a man with a most interesting pet - a large rodent of very distinctive appearance, belonging to a species completely unknown to science. Of stout build with small head and short limbs but long bushy tail, it was principally blackish-brown in colour, but its forehead and the tip of its tail were white, and its flanks each bore a lengthy horizontal strip of pale brown, edged with white and with a white stripe running along its centre. This strip was separated by a type of furrow from the notably long dark hairs borne upon the middle of the animal’s back, and also upon its tail, which were erectile, capable of yielding a very odd-looking mane or crest.

The pelage colouration and pattern of Lophiomys instantly differentiates it from all other rodents (picture source unknown to me)

The pelage colouration and pattern of Lophiomys instantly differentiates it from all other rodents (picture source unknown to me)Imhaus bought the man’s pet, and took it to France’s Garden of Acclimatisation in the Bois de Boulogne, where it thrived for about 18 months upon a diet of maize, vegetables, and bread, and slept during the day. After its death, its body attracted the attention of acclaimed zoologist Prof. Alphonse Milne-Edwards, whose studies of it uncovered sufficient anatomical idiosyncrasies to warrant the creation for its species of a brand new taxonomic family, Lophiomyidae.

In his description of this radically new rodent, published in 1867, Milne-Edwards named it Lophiomys imhausi - ‘Imhaus’s maned rat’. Distributed from Kenya in eastern Africa northwards as far as Ethiopia’s border with Sudan, and measuring up to 21 in long (females are larger than males), its closest relatives appear to be the murids (mice, rats, etc), with which it is nowadays classed by some authorities as a distinct subfamily, Lophiomyinae.

African crested or maned rat — an accomplished skunk impersonator (Kevin Deacon/Wikipedia)

African crested or maned rat — an accomplished skunk impersonator (Kevin Deacon/Wikipedia)A sluggish, generally slow-moving animal, undoubtedly the most distinctive feature of this species is its erectile mane of hair, which has a very important function. The maned rat has few enemies - and little wonder. When challenged by a would-be predator, it raises its mane, and instantly ‘transforms’ into a surprisingly convincing replica of one of the most feared medium-sized mammals of Africa - a long-furred relative of the weasels known as the zorilla or striped polecat Ictonyx striatus.

Although only distantly related to the New World skunks, the zorilla is extraordinarily similar to them, due not only to its vivid black and white fur, but also to its deadly propensity for ejecting streams of unutterably foul-smelling liquid from its anal glands at anything foolish enough to approach it too closely. So dreaded and dreadful is its malodorous arsenal that if a zorilla approaches a lion kill, the lions will back away and wait impatiently but impotently at a safe distance until the little zorilla has eaten its fill and departed. Not for nothing is it referred to by many tribes as ‘Father of the Stenches’!

Zorilla — Africa’s ‘Father of the Stenches’ (picture source unknown to me)

Zorilla — Africa’s ‘Father of the Stenches’ (picture source unknown to me)Thus, by impersonating this Dark Continent untouchable, the relatively harmless maned rat (it does have a strong bite) is assured of similar immunity from most would-be assailants. If, however, it does fail to convince, it can actually exude a very toxic glandular secretion that is sufficiently potent to kill a dog if swallowed.

This ShukerNature post is an excerpt from my book Extraordinary Animals Revisited: From Singing Dogs To Serpent Kings (CFZ Press: Bideford, 2007).

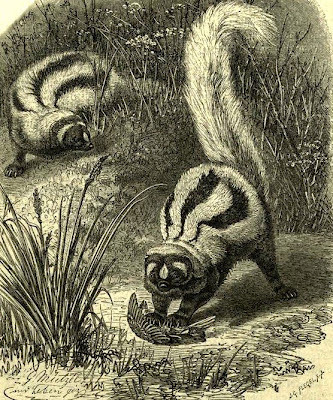

19th-Century engraving depicting a pair of zorillas

19th-Century engraving depicting a pair of zorillas

Published on August 18, 2012 14:17

August 17, 2012

DEMON MASKS, DODOS, WOMBLES, AND OWL KINGS - CAR BOOT SALES AND CRYPTOZOOLOGY #1

My Sri Lankan peacock demon mask (Dr Karl Shuker)

My Sri Lankan peacock demon mask (Dr Karl Shuker)Those of you who know me personally will be well aware that I am partial to wandering around antique markets and book fairs in search of discoveries pertinent to cryptozoology - but some of my most surprising finds have been unearthed either at the more humble car boot and bric-a-brac sales that are perennially popular throughout the UK or in charity shops, whose contents are wonderfully varied and, by their very nature, wholly unique. (For overseas readers who may not be familiar with the term 'car boot sale', all is revealed here .)

Such items are rarely of great (if, indeed, any!) value in a strictly monetary sense, of course, but in terms of their curio worth, they are, at least in my humble opinion, well worth seeking out and salvaging.

So here, for your delectation and delight, is the first in an occasional series of ShukerNature posts revealing some of the exotica and esoterica that I have uncovered over the years while browsing and bartering at car boot and bric-a-brac sales in search of treasures among the tat.

SRI LANKAN PEACOCK DEMON MASK

I saw this beautiful Sri Lankan wood-carved mask at a car boot sale in Birmingham one chilly morning in January 2012, and recognised what it was straight away. Unfortunately, however, it was being perused at the time by a guy in front of me, who couldn't make up his mind whether he wanted it or not, and was haggling with the stall holder concerning its price – while I was standing just behind him silently but very earnestly willing him to put it down and walk off! Happily, he finally did so, telling the stall holder that he'd have a brief walk round to think about it – but the moment he turned away, I grabbed it, paid for it, and walked triumphantly off with it – result!! He who hesitates, etc etc!

Two views of my peacock demon mask from Sri Lanka, via Birmingham! (Dr Karl Shuker)

Two views of my peacock demon mask from Sri Lanka, via Birmingham! (Dr Karl Shuker)The mask depicts Maura Raksha, Sri Lanka's peacock demon, who brings peace, harmony, and prosperity, and is one of several demons whose masks are used in various types of traditional dance-based rituals (e.g. devil dancing, kolam dancing, sokari dancing). These masks are also widely seen at the main entrance of Sinhalese homes, to ward off evil influences and protect the householders, and they date back to pre-Buddhist times when Sri Lanka was an agricultural society.

Coincidentally, the previous year I came upon a set of much smaller but no less interesting Oriental demon masks at a different car boot sale. Originating from Thailand this time, they were in the form of ornamental bottle-top covers.

My set of Thai demon mask bottle-top covers – no home should without one! (Dr Karl Shuker)

My set of Thai demon mask bottle-top covers – no home should without one! (Dr Karl Shuker)WAYNE'S WOMBLE

Earlier this year, I spotted a large-sized fluffy toy in the form of a womble on the stall of a friend, Wayne, at a local bric-a-brac market. Wayne had recently obtained it in a batch of items purchased in a house-clearance sale for reselling purposes, and although it had clearly been a much-loved womble in its time, it had evidently seen better days too, as its fur was somewhat bedraggled now. Consequently, I reluctantly declined the opportunity to add it to the Shuker menagerie. Nevertheless, Wayne kindly agreed to snap a photograph of me holding this womble (I think he's Orinoco), because, after all, in the weirdly wonderful world of cryptozoology, you don't know when such a picture may come in useful...well, you don't!

Underground, overground, wombling free... (Dr Karl Shuker)

Underground, overground, wombling free... (Dr Karl Shuker)ENCOUNTERING THE OWL KING

One of my more recent car boot purchases, this small but delightful figurine is of an owl wearing a crown. I have no idea as to its origin or specific significance, though I am aware that owl kings and similar characters feature in various European folktales, so I assume that this is what it represents.

My owl king figurine (Dr Karl Shuker)

My owl king figurine (Dr Karl Shuker)In any event, an owl king purchased for the princely sum of only £5 is certainly a bargain!

And don't forget to check out future ShukerNature posts for more car boot curios! After all, where else are you likely to find a Portuguese egg-bowl in the shape of a dodo??

Happy hunting!

My dodo-shaped Portuguese egg-bowl, purchased at a bric-a-brac market for £2.50 many years ago (Dr Karl Shuker)

My dodo-shaped Portuguese egg-bowl, purchased at a bric-a-brac market for £2.50 many years ago (Dr Karl Shuker)

Published on August 17, 2012 14:20

August 15, 2012

THE TRUTH ABOUT BLACK PUMAS - SEPARATING FACT FROM FICTION REGARDING MELANISTIC COUGARS

Computer-generated mock-up of a black puma (Dr Karl Shuker)

Computer-generated mock-up of a black puma (Dr Karl Shuker)In all the time that I have been researching and documenting creatures of cryptozoology (almost 30 years now!), I have encountered few subjects engendering more controversy and confusion than the reality, or otherwise, of black pumas. Consequently, I have explored various aspects of this most contentious mystery cat in a number of different publications of mine. Yet as the subject still incites heated debate even today, I feel that it is now time to assemble together my disparate writings concerning it, and present them here (together with some previously-unpublished information) as a ShukerNature review article.

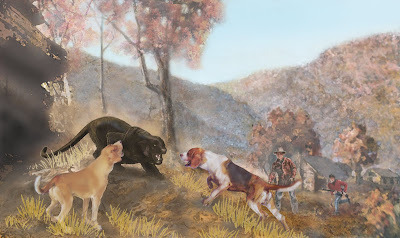

North American mystery black panther – a melanistic leopard, or a black puma? (William Rebsamen)

North American mystery black panther – a melanistic leopard, or a black puma? (William Rebsamen)The two most commonly-voiced identities for Britain’s elusive ebony-furred mystery cats, as well as those reported in continental Europe, North America, and Australia, are escapee/released black panthers (i.e. melanistic, all-black specimens of the leopard Panthera pardus) and black (melanistic) pumas. Yet whereas the former is plausible, the latter is little short of impossible - for two extremely good, fundamental reasons.

REASON #1: CONSPICUOUS BY ITS ABSENCE

Ordinarily, the puma Puma concolor (aka the cougar, mountain lion, panther, catamount, and painter) occurs in two separate colour forms (morphs) – tawny-red, and slaty-grey, both of which are common.

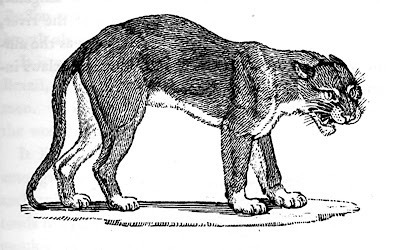

A normal tawny-coloured puma

A normal tawny-coloured pumaConversely, even though this species has the greatest native distribution range of any modern-day wild cat, occurring from the northernmost regions of North America to the southern tip of South America, the number of confirmed black pumas can be counted on the claws of one paw!

Not a single scientifically-confirmed preserved specimen exists. In 1843, a bona fide black puma was shot in the Carandahy River section of Brazil by professional hunter William Thomson, but regrettably its skin was not retained. In addition, I have seen various online mentions of an enigmatic taxiderm cat dubbed the 'Cherokee cougar' that has been claimed to be a black puma. Measuring 6 ft 2 in (1.87 m) long, and variously said to have been shot in Tennessee or Montana, it has been denounced by sceptics as a normal puma that has been dyed black, or some entirely different feline species. However, hair samples from it that were tested by researchers from the zoology department of East Tennessee State University confirmed that they had not been dyed, and DNA samples verified that it was a puma. Nevertheless, photos of it (not seen by me so far) apparently suggest that it is dark brown rather than truly black.

Unfortunately, however, no primary sources concerning this potentially significant specimen are provided by any online documentation that I have encountered so far. So if any reader can provide some, or can offer any further information or first-hand observations regarding it, I would greatly welcome receipt of them.

In 1998, American mystery cat investigator Keith Foster of Holcolm, Kansas, informed me that what had been reported to him by the person concerned as being a "glossy black puma" had been shot and killed in Oklahoma several years previously after it had been killing sheep on his father's farm. Afterwards, this person (a church pastor who was known to Keith) contacted the authorities, and the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife duly confiscated the cat's carcase. Nothing more was heard about it after that, but Keith vowed to trace it. Unlike so many cryptozoological cases featuring a missing specimen, moreover, Keith did succeed in doing so, but was disappointed to discover that it wasn't glossy black in colour after all, merely grey.

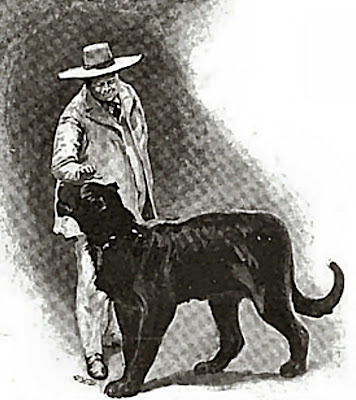

As for pictorial evidence, only one clear, unequivocal photograph of a black puma is known. Reproduced below, this photo depicts a dead specimen shot in 1959 by Miguel Ruiz Herrero in the province of Guanacaste along Costa Rica's north Pacific coast. Estimated to weigh 100-120 lb, its carcase is seen here alongside Ruiz's herdsman, but what happened to it afterwards is unknown.

Ruiz's black puma (Miguel Ruiz Herrero)

Ruiz's black puma (Miguel Ruiz Herrero)In view of such exceptional scarcity of tangible evidence, it is evident that the prospect of any of Britain's, Europe's, or Australia's black mystery cats being escapee/released black pumas is unlikely in the extreme. After all, if there were such extraordinarily rare non-native cats as black pumas in captivity in any of these regions, they would surely have attracted immense publicity, and would have been far too valuable to be allowed to escape or to be released by their owners.

But what about in North America, where the puma is a native species? Surely a black morph could have arisen here? After all, countless sightings of seemingly very large all-black cats claimed by their eyewitnesses to be melanistic pumas have been reported all over this continent (most especially in the east), and continue to be today. There are even Native American traditions appertaining to such beasts, which they termed 'black devils' or 'devil cats'. But could they truly be melanistic pumas? Not according to Reason 2.

REASON #2: THE TWO-TONE DILEMMA

Whereas most melanistic cat forms are uniformly black all over, so-called black pumas only have black upperparts. Their underparts are noticeably paler, usually slate-grey or dirty cream. This provides crucial evidence for discounting such cats as the identity of Britain’s, Europe's, North America's, and Australia's pantheresque mystery cats, because these latter felids, just like bona fide black panthers (and also like melanistic specimens of the jaguar Panthera onca), are black all over.

A black panther, i.e. melanistic leopard (Qilinmon at the English language Wikipedia)

A black panther, i.e. melanistic leopard (Qilinmon at the English language Wikipedia)The black puma's distinctive two-tone colouration, black dorsally and paler ventrally, can be clearly discerned in Ruiz's specimen. Equally, the Carandahy River specimen's appearance was described by Thomson in his book Great Cats I Have Known (1896) as follows:

"The whole head, back, and sides, and even the tail, were glossy black, while the throat, belly, and inner surfaces of the legs, were shaded off to a stone gray."

THE JAGUARETE – AN AMALGAMATED ANOMALY?

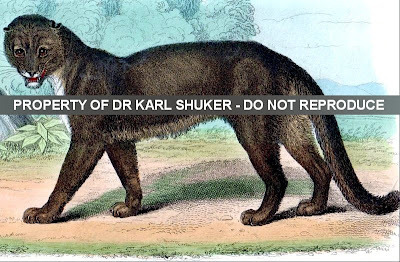

Yet although exceedingly scarce today, black pumas do seem to have been more common in past ages, certainly in South (even if not in North) America, because there are a number of reports and even one or two early illustrations of such cats, sometimes dubbed ‘couguars noires’, in archaic natural history tomes. And these reports and illustrations often compare closely with the (very) few verified modern-day specimens - although in some cases there appears to have been confusion between, and amalgamation of, reports of black pumas and reports of black jaguars.

A black (melanistic) jaguar (cburnett/Wikipedia)

A black (melanistic) jaguar (cburnett/Wikipedia)I examined this confusing situation as follows in my very first book, Mystery Cats of the World (1989):

"Referred to in Latin America as `black tigers', [melanistic jaguars] tend to be noticeably large, especially in the Mato Grosso. According to various antiquarian zoology tomes and native Guyanan beliefs however, a further type of black tiger would seem to exist within this continent, one which allegedly is very different morphologically from the typical melanistic jaguar. Nevertheless, its precise identity has never been satisfactorily ascertained.

"Nowadays a totally forgotten felid, this mysterious melanistic was referred to as the `cougar noire' by the eminent eighteenth-century naturalist de Buffon, and as the `jaguarete' (a less ambiguous name, which I therefore prefer and shall use hereafter in this book) by his equally eminent contemporary Thomas Pennant. However, in the virtually verbatim version of Pennant's description which appeared in Thomas Bewick's A General History of Quadrupeds, S. Hodgson referred to it merely as `the black tiger'. Hodgson's choice of name would seem to imply that the jaguarete is truly nothing more than a straightforward melanistic jaguar. Yet neither the illustration which accompanied Pennant's description nor that (by Bewick) which accompanied Hodgson's is compatible with such an identity. To quote Pennant:

"'Head, back, sides, fore part of the legs, and the tail, covered with short and very glossy hairs, of a dusky-color; sometimes spotted with black, but generally plain: upper lips white: at the corner of the mouth a black spot: long hairs above each eye, and long whiskers on the upper lip; lower lip, throat, belly, and the inside of the legs, whitish, or very pale ash-color; paws white: ears pointed. Grows to the size of a heifer of a year old: has vast strength in its limbs. Inhabits Brasil and Guiana (Guyana]: is a cruel and fierce beast; much dreaded by the Indians; but happily is a scarce species.'"

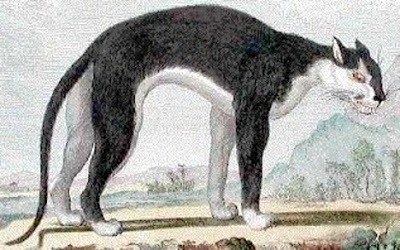

Bewick's 'black tiger', in which it is clearly two-tone (like a black puma) rather than uniformly black (like a black jaguar)

Bewick's 'black tiger', in which it is clearly two-tone (like a black puma) rather than uniformly black (like a black jaguar)"In addition, Hodgson noted that it frequented the seashore and that it preyed upon a variety of creatures (including lizards, alligators and fishes) as well as devouring turtles' eggs and (rather curiously) the buds and leaves of the Indian fig."

Buffon's two-tone 'cougar noire'

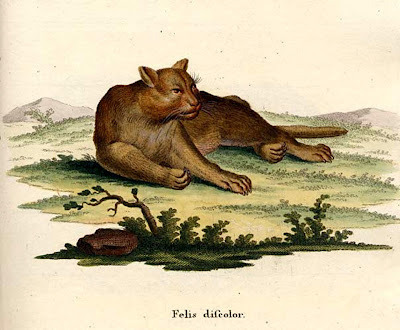

Buffon's two-tone 'cougar noire'Subsequent to writing Mystery Cats of the World , I discovered that in 1778, German naturalist Johann Christian Daniel Schreber had formally described the jaguarete and christened it Felis discolor ('two-coloured cat'). Yet, paradoxically, the accompanying colour illustration of it merely showed a mid-/dark-brown cat resembling a normal puma!

Schreber's monotone 'two-coloured cat'

Felis discolor

Schreber's monotone 'two-coloured cat'

Felis discolorReturning to my book's account of this mysterious cat:

"What could the jaguarete be? On first sight, a black jaguar identity seems most likely - in most specimens, the rosettes can indeed be seen as cryptic markings against the coat's abnormally dark colouration. However, the black jaguar is dark dorsallv and ventrally, just like the black panther and other melanistic felid individuals, thereby contrasting markedly with the near-white underparts, lowers jaw and paws of the jaguarete. Of course, it may be that the jaguarete is nothing more than an inaccurate description of a black jaguar, but arguing against this is the statement in a footnote by Pennant that two jaguaretes were actually shown in London during the eighteenth century; hence their appearance would have been familiar to naturalists of that time."

In my book, I went on to consider two additional jaguar possibilities. One was that the jaguarete was a jaguar possessing the rare recessive black-and-tan mutant allele of the agouti gene in homozygous (two-copy) form, because this yields a cat with black dorsal pelage but light or cream underparts, which corresponds well with the shot black pumas of Thomas and Ruiz. The other possibility was a pseudo-melanistic jaguar, i.e. one in which its rosettes had freakishly multiplied and amalgamated to yield a similar appearance – black dorsally and normal, paler colouration ventrally.

However, having given the matter of the jaguarete further consideration since writing that book, I now deem it more plausible that like so many other cryptids (such as the great sea serpent and the Nandi bear), the jaguarete was in reality a non-existent composite beast, erroneously created by combining together reports of wholly different animals. In the case of the jaguarete, those animals would seem to be normal South American melanistic jaguars (explaining the spots) and rare but nevertheless real South American melanistic pumas (explaining the two-tone colour scheme, which matches that of the Ruiz and Thomas cats). Certainly, some of the images that I have seen of the jaguarete greatly resemble black pumas of this nature, even including the puma's characteristic black facial bar, as seen, for instance, in the illustration below:

Engraving of the jaguarete in Thomas Pennant's A History of the Quadrupeds (1781)

Engraving of the jaguarete in Thomas Pennant's A History of the Quadrupeds (1781)THE YANA PUMA – NEITHER PUMA NOR JAGUAR?

As if the jaguarete had not muddied – and muddled - the taxonomic waters sufficiently in relation to black pumas and black jaguars, South America may also be home to a further melanistic mystery cat, and of quite prodigious size, as documented by me in another of my books, The Beasts That Hide From Man (2003). Known as the yana puma, it may even have been the inspiration for one of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's most famous short stories, 'The Brazilian Cat', which was first published by Strand Magazine in 1898, then republished in a 1923 collection of his horror stories, Tales of Terror and Mystery.

One of the illustrations by Sidney Paget accompanying the original 1898 publication of 'The Brazilian Cat'

One of the illustrations by Sidney Paget accompanying the original 1898 publication of 'The Brazilian Cat'Here is a condensed version of my book's account of the yana puma:

"Several years ago, I read a short story by Conan Doyle called 'The Brazilian Cat', published in 1923, which featured a huge, ferocious, ebony-furred felid that had been captured at the headwaters of the Rio Negro in Brazil. According to the story: "Some people call it a black puma, but really it is not a puma at all". Yet there was no mention of cryptic rosettes, which a melanistic (all-black) jaguar ought to possess, and it was almost 11 ft in total length - thereby eliminating both puma and jaguar from consideration anyway. Hence I simply assumed that Doyle's feline enigma was fictitious, invented exclusively for his story - but following some later cryptozoological investigations of mine, I am no longer quite so sure.

"To begin with: in Exploration Fawcett (1953), the famous lost explorer Lt.-Col. Percy Fawcett briefly referred to a savage 'black panther' inhabiting the borderland between Brazil and Bolivia that terrified the local Indians, and it is known that Fawcett and Conan Doyle met one another in London. So perhaps Fawcett spoke about this 'black panther' and inspired Doyle to write his story. But even if so, it still does not unveil the identity of Fawcett's panther. Black pumas are notoriously rare - only a handful of specimens have been obtained from South and Central America (and none ever confirmed from North America). Conversely, black jaguars are much more common, and with their cryptic rosettes they are certainly reminiscent of (albeit less streamlined than) genuine black panthers, i.e. melanistic leopards. However, the mystery of Brazil's black panthers is far more abstruse than this... [I then went on to discuss the Brazilian jaguarete, referring to the accounts of Buffon and Pennant already incorporated in this present ShukerNature article.]

"Yet as it seemed to be nothing more than a non-existent composite creature - 'created' by early European naturalists unfortunately confusing reports of black jaguars with black pumas - the jaguarete eventually vanished from the wildlife books. Even so, its rejection by zoologists as a valid, distinct felid may be somewhat premature. This is because some reports claimed that the jaguarete was much larger than either the jaguar or the puma - a claim lending weight to the prospect that a third, far more mysterious black cat may also have played a part in this much-muddled felid's history.

"Dr Peter J. Hocking is a zoologist based at the Natural History Museum of the National Higher University of San Marcos, in Lima, Peru. Aside from his official work, for several years he has been collecting and investigating local Indian reports describing various different types of mysterious, unidentified cat said to inhabit the Peruvian cloudforests. One of these, of great relevance here, has been dubbed by him 'the giant black panther'.

"In an article published by the journal Cryptozoology in 1992, Dr Hocking revealed that this particular Peruvian mystery cat is said to be entirely black, lacking any form of cryptic markings, has large green eyes, and is at least twice as big as the jaguar. Moreover, the Quechua Indians term it the yana puma ('black mountain lion'). This account immediately recalls Conan Doyle's story of the immense Brazilian black cat. The yana puma is apparently confined to montane forest ranges only rarely visited by humans, at altitudes of around 1600-5000 ft. If met during the day, when resting, it is generally passive, but at night this mighty cat becomes an active, determined hunter that will track humans to their camps and has sometimes slaughtered an entire party while they slept, by lethally biting their heads.

"When discussing the yana puma with mammalogists, Hocking has frequently been informed that it is probably nothing more than a large melanistic jaguar. Yet as he pointed out in his article, such animals do not attain the size claimed for this mysterious felid (nor do melanistic pumas) - and the Indians are adamant that it really is quite enormous. Nevertheless, the yana puma could still merely be a product of native exaggeration, inspired by real black jaguars (or pumas) but distorted by superstition and fear.

"However, a uniformly black, unpatterned felid does not match either a black jaguar or a black puma - yet it does compare well with Conan Doyle's Brazilian cat. Moreover, as some jaguarete accounts spoke of a black cat that was notably larger than normal jaguars and pumas, perhaps the yana puma is not limited to Peru, but also occurs in Brazil. Is it conceivable, therefore, that Doyle (via Fawcett or some other explorer contact) had learnt of the yana puma, and had based his story upon it? If so, it would be one of the few cases on file in which a bona fide mystery beast had entered the annals of modern-day fiction before it had even become known to the cryptozoological - let alone the zoological - community!"

Particularly intriguing in relation to the yana puma is an illustration that I recently came upon while browsing through Sir William Jardine's tome The Natural History of the Felinae (1834). It was a magnificent watercolour drawing by James Hope Stewart of an alleged black puma from Paraguay, dubbed ‘Felis nigra’, with big green eyes and unpatterned coat.

‘Felis nigra’, a black puma – or even the yana puma?

‘Felis nigra’, a black puma – or even the yana puma?Yet unlike other abnormally dark pumas on record, the Jardine individual was black all over, rather than being black dorsally and paler ventrally. Consequently, its uniformly black, unpatterned pelage, together with its large green eyes, accord well with native descriptions of the Peruvian yana puma.

ARE BLACK PUMAS AN OPTICAL ILLUSION?

Over the years, a number of explanations for claimed sightings of native black pumas in North America and escapee/released non-native black pumas elsewhere have been put forward, proposing that they are merely normal pumas observed under abnormal conditions. When tested, however, such theories have failed to deliver. To quote once again from my Mystery Cats of the World :

"[As contemplated by veteran puma investigator Bruce Wright:] Could normal-coloured pumas appear black when wet? To investigate this, Wright took the fresh hide of a newly killed puma from Vancouver Island, suspended it by its edges, filled it with water and left it overnight. When he examined it the following morning, however, despite viewing and photographing it from every conceivable angle, he was unable to make it appear black in colour. He also considered the possibility that backlighting of normal pumas could create the illusion of black fur, but this, when checked, proved untenable too."

A BLACK PUMA AT LONDON ZOO?

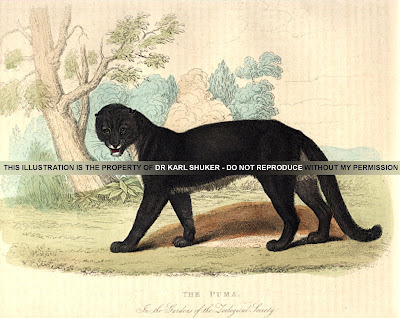

Finally: The following account and images, included here as a ShukerNature exclusive, are excerpted from my forthcoming book Cats of Magic, Mythology, and Mystery (CFZ Press: Bideford, 2012). Once this book has been published, I shall remove the watermarks from the images below:

"As far as I was aware, no such animal [black puma] had ever been kept in captivity, at least not in Europe. But all that changed a while ago during one of my numerous visits to one of my all-time favourite places – Hay On Wye, Herefordshire’s world-famous ‘Town of Books’, nestling on the Welsh border.

"In addition to around 30 bookshops at present, this small town also has shops devoted to antiquarian prints. As an avid collector of such items, I was browsing in one of these shops one sunny Saturday afternoon during the late 1990s when I came upon a truly remarkable example – remarkable because it is not often that an antiquarian print depicts a cryptozoological cat!

"The print in question, which was an original hand-coloured copper engraving dating from 1862 (as written in pencil on its reverse), and which I naturally lost no time in purchasing, is duly reproduced here (its previous appearance, in an article of mine published by the now defunct British monthly magazine Beyond, where it was reproduced in its original full-colour format, may well have been the first time that it had ever been published anywhere), and appears to portray a bona fide black puma."

My black puma engraving (Dr Karl Shuker)

My black puma engraving (Dr Karl Shuker)"Certainly, it comes complete with jet-black upperparts, slaty-grey underparts, and white chest – very different from normal pumas, which are either tawny brown-rufous or silver-grey (the puma exhibits two distinct colour morphs), but matching precisely those few confirmed black puma specimens. Most interesting of all, however, is the engraving’s caption: “The Puma. In the Gardens of the Zoological Society”. This means that if the puma in the engraving has been coloured accurately, and there is no reason why it should not have been, a black puma, that most mysterious of mystery cats, was once actually on display at London Zoo!

"When I first discovered this engraving, I wondered whether its astonishing black puma was exhibited at London Zoo at the same time as the zoo’s unique captive woolly cheetah, bearing in mind that the engraving was dated 1862. Who knows, if so, it may even have been in the enclosure next door!

"In February 2011, however, I discovered a second copy of the same puma engraving, but this one was dated 1825. (Moreover, the hand-colouring on this latter version, reproduced here, is much more skilful.)"

The second version of the black puma engraving (Dr Karl Shuker)

The second version of the black puma engraving (Dr Karl Shuker)"So which (if either) is the correct date for it? The mystery deepens, and darkens – which is very apt for anything featuring a black puma at its core!"

Indeed it is. For as I have shown here, the all-too-commonly-cited 'explanation' in media reports of black mystery cats being black pumas is woefully unsubstantiated at the present time by confirmed evidence of such cats' existence. Or, to rephrase this situation in a more succinct manner – AWOL black pumas RIP!

NB - In most cat species, melanism is due to the expression in homozygous (two-copy) form of a recessive mutant allele; in the leopard and probably other species too, this is the non-agouti mutant allele of the agouti gene. Conversely, in the jaguar and also the jaguarundi Puma yagouaroundi, melanism is due to the expression of a dominant mutant allele instead. In the case of the puma, however, the genetic basis of melanism is presently unknown, but as black pumas do not display a uniformly black pelage anyway but rather a two-tone pelage, it is likely to be due to a fundamentally different genetic scenario.

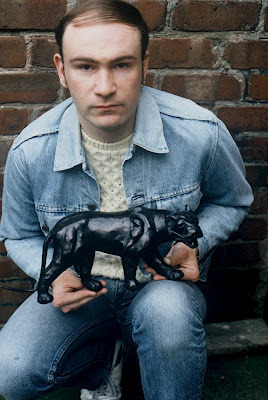

Holding a model of a black panther (Dr Karl Shuker)

Holding a model of a black panther (Dr Karl Shuker)

Published on August 15, 2012 18:55

August 9, 2012

THE BONOBO OR PYGMY CHIMPANZEE - A NEW APE, INCOGNITO

A bonobo at Twycross Zoo (Dr Karl Shuker)

A bonobo at Twycross Zoo (Dr Karl Shuker)One of the highlights of my visit yesterday to Twycross Zoo in Leicestershire, England - famous worldwide for its very comprehensive collection of primates and its excellent record of success in breeding and conserving endangered species - was viewing its breeding group of bonobos or pygmy chimpanzees Pan paniscus, led as is normal for this species by an alpha female (in the common chimp, conversely, it is an alpa male who acts as group leader).

Our own species' closest living relative (putative living Neanderthals excepted!), the bonobo is visibly different in several ways from the much more familiar common chimpanzee P. troglodytes - which makes it all the more remarkable that its separate taxonomic status was not even suspected, let alone recognised, until the 1920s, i.e. less than 100 years ago. The history of the bonobo's official scientific discovery and classification as a valid species of great ape in its own right is a major success story for cryptozoology, and makes fascinating reading, which I have documented in all three of my books on new and rediscovered animals - The Lost Ark( 1993), The New Zoo (2002), and The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals(2012), and is now reproduced here on ShukerNature:

The bonobo is visibly different from - and much more human-like than - the common chimpanzee (Dr Karl Shuker)

The bonobo is visibly different from - and much more human-like than - the common chimpanzee (Dr Karl Shuker)Until the mid-1920s, science only accepted the existence of one species of chimpanzee, the familiar common species Pan troglodytes, generally divided into three subspecies. In 1928, however, zoologist Dr Ernst Schwarz was examining some specimens at the Congo Museum in Tervueren, Belgium, when he came upon a series of skeletons and skins of a chimpanzee type that appeared very different from any that he had seen before.

Two bonobos at Twycross Zoo (Dr Karl Shuker)

Two bonobos at Twycross Zoo (Dr Karl Shuker)Obtained by a M. Ghesquiere, they revealed that this strange form of chimpanzee was smaller in size than the common species, and was much more slender in build. Its head was smaller too, but its face was longer and narrower, its dense fur was also long and was uniformly black except for a small white patch on the rump, and it lacked the common chimpanzee's familiar white beard. Schwarz discovered that these odd-looking chimps had been collected in an area of tropical rainforest on the south bank of the Congo River - all previously recorded chimpanzees had been obtained from localities north of this river.

Until viewing Twycross's specimens yesterday, I had not realised just how gracile, or relatively long-limbed, the bonobo is in comparison with the common chimpanzee (Dr Karl Shuker)

Until viewing Twycross's specimens yesterday, I had not realised just how gracile, or relatively long-limbed, the bonobo is in comparison with the common chimpanzee (Dr Karl Shuker)Evidently, the southern chimps comprised an important find, and their distinctive morphology persuaded Schwarz that they represented a currently undescribed subspecies. Hence in 1929 he formally documented it within the museum's journal, naming this new ape P. t. paniscus - the pygmy chimpanzee. Five years later, it was elevated to the level of a full species - P. paniscus.

Bonobo - the leggiest member of the great apes (Dr Karl Shuker)

Bonobo - the leggiest member of the great apes (Dr Karl Shuker)Once science became aware of this freshly-found primate, investigations uncovered that the Tervueren examples were not the only specimens of pygmy chimp to have been collected without recognition of their separate taxonomic status. The British Museum's collections had contained one in 1895, for instance, and a living example of what was almost certainly a pygmy chimp had been on show for a time in 1923 at New York's Bronx Zoo. Similarly, John Edwards, a zoological historian and Fellow of London's Zoological Society, has kindly brought to my attention a picture postcard in his private collection depicting a chimp housed in Amsterdam Zoo, again during the early 1920s, which was quite obviously a pygmy chimpanzee.

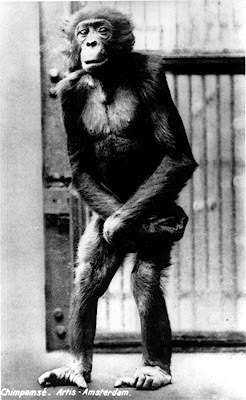

John Edwards's historically significant postcard, depicting a bonobo maintained at Amsterdam Zoo before the separate taxonomic status of its species had been recognised (John Edwards)

John Edwards's historically significant postcard, depicting a bonobo maintained at Amsterdam Zoo before the separate taxonomic status of its species had been recognised (John Edwards)Since the species' 'official' discovery, specimens (correctly identified) have been exhibited at several zoological gardens, particularly in European collections such as Antwerp Zoo and Vincennes Zoo. In 1962, Frankfurt Zoo succeeded in breeding pygmy chimps for the first time in captivity, and has repeated this feat on a number of occasions since then. Studies of captive individuals such as these have revealed that the pygmy chimpanzee is much more docile and even-tempered than its less placid, better-known relative.

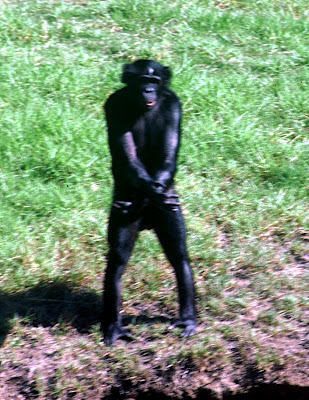

Bonobos are able to stand upright on their hind legs and are adept at walking bipedally too (Alan Pringle)

Bonobos are able to stand upright on their hind legs and are adept at walking bipedally too (Alan Pringle)There has been a fair amount of controversy concerning the pygmy chimpanzee's precise taxonomic identity. Whereas some experts are so convinced of its distinct specific status that they have even placed it within its own genus, as Bonobo paniscus (bonobo is its native name), certain others still prefer to treat it merely as a subspecies of the common chimpanzee. Recent biochemical and genetic comparisons between common and pygmy chimps, however, indicate that the latter ape is certainly sufficiently distinct to justify classification as a separate species (though whether separate generic status for it is warranted is still a matter for conjecture).

When viewing a photograph like this one, it is not difficult to comprehend that the bonobo is our own species' closest living relative (Dr Karl Shuker)

When viewing a photograph like this one, it is not difficult to comprehend that the bonobo is our own species' closest living relative (Dr Karl Shuker)It seems surprising that a wholly new species of ape could remain undetected by science until as recently as the late 1920s, especially when specimens were actually preserved in scientific museums and exhibited alive in zoos. In fact, there is an even more ironic twist to this tale. Following extensive researches on the subject, Vernon Reynolds revealed in the 1960s that the individual designated by Linnaeus way back in 1758 as his type specimen for the common chimpanzee was actually a pygmy chimpanzee!

The bonobo - now recognised as a wholly discrete, second species of chimpanzee after centuries of taxonomic obscurity (Dr Karl Shuker)

The bonobo - now recognised as a wholly discrete, second species of chimpanzee after centuries of taxonomic obscurity (Dr Karl Shuker)For many more remarkable histories of animal discovery and rediscovery, please check out my latest book, The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals: From Okapis to Onzas - and Beyond (Coachwhip Publications: Landisville, 2012).

Published on August 09, 2012 16:18

August 8, 2012

SEX AND THE SINGLE SATYR

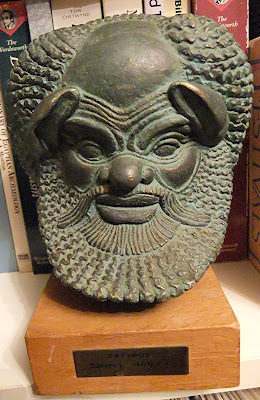

Replica of Greek satyr bust from c.400 BC (Dr Karl Shuker)

Replica of Greek satyr bust from c.400 BC (Dr Karl Shuker)A few months ago, I spotted in a charity shop the very unusual artefact depicted above at the beginning of this ShukerNature blog post; and after recognising what it was, I lost no time in purchasing it for the princely sum of just £5. It is a replica of a Greek stone bust dating from c.400 BC, which portrays the head of a satyr.

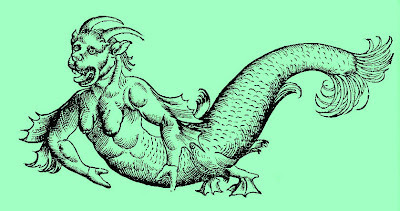

Typical latter-day depiction of satyr as goat-man in a medieval bestiary by Aldrovandi

Typical latter-day depiction of satyr as goat-man in a medieval bestiary by AldrovandiToday, the popular image of a satyr is that of a semi-human semi-goat entity, with hairy goat-legs and hoofed feet, a pair of short curly horns, and a very inconspicuous goat-tail.

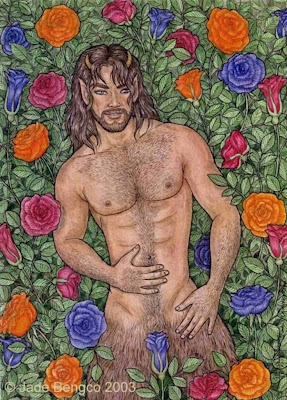

'Satyr Among Roses' (Jade Bengko)

'Satyr Among Roses' (Jade Bengko)In classical Greek mythology, conversely, the satyr was originally represented with the long, profusely-haired tail of a horse, with pointed donkey-like ears rather than horns, a flattened nose, and the legs and feet of a normal human.

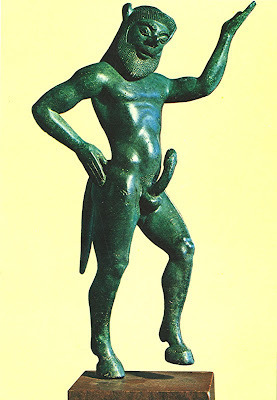

Satyr depicted with a long, full-bodied horse-tail on a pottery fragment from a Greek amphora dating from the 6th Century BC

Satyr depicted with a long, full-bodied horse-tail on a pottery fragment from a Greek amphora dating from the 6th Century BCLovers of wine, nymphs, and playing music with their panpipes, satyrs were disciples of a minor demi-god of fertility called Silenus, and, just like him, they were also enthusiastic followers of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine. As Silenus was commonly portrayed as an elderly man of typically inebriated aspect, old satyrs were duly referred to as sileni (young ones were known as satyrisci).

'Drunken Silenus', a 2nd-Century-AD Roman marble statue in the Louvre, Paris (public domain)

'Drunken Silenus', a 2nd-Century-AD Roman marble statue in the Louvre, Paris (public domain)During Roman times, however, the image of the satyr became conflated and ultimately synonymised with that of a rustic Roman nature deity called Faunus. He was half-human, half-goat, as were his followers, known as fauns (though originally they were described as half-human, half-deer).

Statue of Faunus at the Fountain of Neptune in Florence, Italy, sculpted by Bartolomeo Ammanati (public domain)

Statue of Faunus at the Fountain of Neptune in Florence, Italy, sculpted by Bartolomeo Ammanati (public domain)Since then, satyrs and fauns have generally been treated as one and the same type of mythical entity. But just how mythical – or otherwise – are satyrs?

As described time and again in mythology and folklore, satyrs were infamously lewd and lustful, never happier than when, fuelled by copious quantities of wine, they were in lecherous pursuit of some hapless nymph to ravish.

Satyr statue by Frank (Guy) Lynch in Sydney Botanic Gardens, Australia, visited by me during autumn 2006 (Dr Karl Shuker)

Satyr statue by Frank (Guy) Lynch in Sydney Botanic Gardens, Australia, visited by me during autumn 2006 (Dr Karl Shuker)In my book The Unexplained (1995), I documented a remarkable cryptozoologically-relevant link between these priapic satyrs of classical legend and certain forms of elusive man-beast being reported today – with the emphasis very definitely upon priapic. Here is what I wrote:

"In Greek mythology, satyrs were semi-humans with the hairy legs, hooves, tail, and short horns of goats - but did they have a basis in reality? This unexpected prospect was raised in a stimulating paper published in the scientific journal Human Evolution in 1994 by Dr Helmut Loofs-Wissowa from the Australian National University's Faculty of Asian Studies.

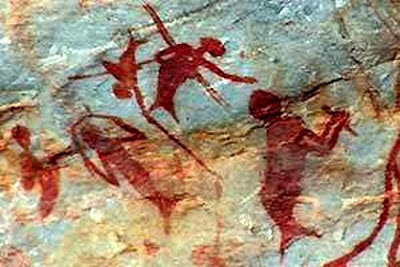

"In ancient classical art, satyrs were frequently portrayed with a prominently erect penis - even when engaging in non-sexual activity. Indeed, it was this characteristic that earned them their reputation for sexual licentiousness. However, Dr Loofs-Wissowa believes that this is all fallacious - that in reality, the satyrs were displaying a physiological condition known as the penis rectus, in which the penis assumes a horizontal position even when flaccid. Among modern humans, this condition is only recorded from the bushmen of South Africa, but it is often portrayed in prehistoric cave art, including some Upper Palaeolithic examples from Europe, in which the figures exhibiting the penis rectus condition are hairy humanoids."

Classical Greek satyr statue ostensibly portraying the penis rectus condition (Athens Archaeological Museum)

Classical Greek satyr statue ostensibly portraying the penis rectus condition (Athens Archaeological Museum)"There are two very intriguing aspects concerning this. One is that anthropologists have argued that these hirsute figures are representations of Neanderthal Man Homo neanderthalensis, which is believed to have died out at least 30,000 years ago. The other is that sightings of hairy troll-like humanoids are often reported in many parts of Asia, and these are believed by some scientists to be relict, modern-day Neanderthals, eluding formal scientific discovery. Of particular note here is that eyewitness descriptions of these mystifying entities have often alluded to the odd fact that they seem to have permanently erect penises, apparent even when spied indulging in non-sexual activity such as eating or walking. This suggests that they are in reality displaying the penis rectus condition.

"Combining all of this information, Loofs-Wissowa suggests that the penis rectus condition is clearly a marker in human palaeontology, i.e. indicating the identity of Neanderthals. And, as a direct consequence, he boldly proposes that satyrs might actually have been latter-day Neanderthals. He notes that many features attributed to satyrs in artistic representations differentiate them from modern humans but ally them to Neanderthals. These include their hairy body, upturned nose, prominent eye ridges, round head, strong neck - and, most noticeable of all, their exhibition of the penis rectus condition, hitherto wrongly identified as an overtly visual indication that satyrs possessed a hyperactive sex drive.

"A very novel idea, but it still leaves unexplained the small matter of the satyrs' hooves and tail, not to mention their horns..."

Statue of a satyr unearthed at Pompeii, Italy (Dr Karl Shuker)

Statue of a satyr unearthed at Pompeii, Italy (Dr Karl Shuker)Not all cryptozoologists, however, agree that satyrs may represent relict Neanderthals. In their book The Field Guide to Bigfoot, Yeti, and Other Mystery Primates Worldwide (Avon Books: New York, 1999), Loren Coleman and Patrick Huyghe propose an alternative but equally thought-provoking option. They suggest that man-beasts exhibiting this distinctive penile condition represent a category of man-beast entirely separate from Neanderthals. They term it the Erectus Hominid, as they believe this man-beast may constitute a surviving representative of one of our own species' ancestors, Homo erectus:

"The Erectus Hominid is probably the least known of the world's mystery hominids. The reason for this is simple: most of the beings in this class have in the past been misidentified as Neanderthal. The Erectus Hominid is human-sized to about six feet tall. Its body is also within the standard human range with a slight barrelling of the chest. They are partially to fully hairy, with head hair longer than their body hair. The males of the class normally display a semi-erect penis."

Whatever the identity of satyrs in European mythology may be, however, there is an intriguing yet generally overlooked reason for their unbridled libido and debauched passion for seducing nymphs – the same reason why I entitled this ShukerNature blog post 'Sex and the Single Satyr'. Remarkably, there is no reference anywhere in the annals of classical mythology to female satyrs!

'Nymphs and Satyr', painted by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905)

'Nymphs and Satyr', painted by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905)By definition, therefore, all satyrs were doomed to remain single, celibate, and sexually frustrated – unless they could achieve some lascivious success with the local dryads (wood nymphs) and oreads (mountain nymphs). Equally, such illicit liaisons offered the only opportunity for satyrs to procreate, producing new generations of satyrs, albeit ones that were increasingly diluted by the nymphs' genetic input.

Statue of an infant faun at Glastonbury, Somerset (Dr Karl Shuker)

Statue of an infant faun at Glastonbury, Somerset (Dr Karl Shuker)Eventually, satyrs simply vanished from folklore and traditions, but, faced with such an uncertain, unpredictable pathway to reproductive success, it is hardly surprising really that they became extinct!

Satyr frolicking with nymphs, painted by Claude Lorrain (public domain)

Satyr frolicking with nymphs, painted by Claude Lorrain (public domain)

Published on August 08, 2012 18:33

August 5, 2012

RIDDLE OF THE BURU, AND THE LUNGFISH LINK

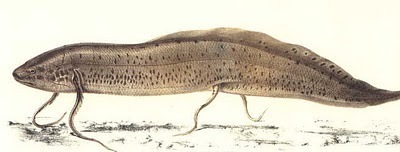

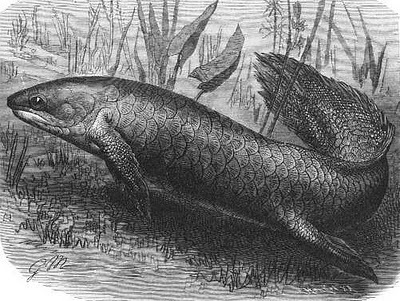

African lungfish

African lungfishAfter reading an interesting cryptozoology post on the CFZ Bloggo re the buru, which mentioned my theory that this remarkable Asian mystery beast may be a giant lungfish, here is my full coverage of this subject, excerpted from my book Extraordinary Animals Revisited (2007) after it had debuted in my book's original edition Extraordinary Animals Worldwide (1991). (Incidentally, I had originally posted this particular article on ShukerNature back on 31 January 2009, but in attempting to update it yesterday, it somehow was republished in its entirety here, thereby obliterating the earlier version.)

Known scientifically as dipnoans (‘double noses’) because they have external and internal nostrils, lungfishes are undoubtedly among the most unusual of all modern-day fishes, with an air-bladder modified into lungs (either single or paired) richly supplied with blood, paired fleshy fins, an odd but characteristic pointed tail, and an overall appearance reminiscent of some strange hybrid of eel and overgrown newt. Little wonder, then, that they so greatly perturbed zoologists when first discovered.

Although lungfishes have an extensive fossil history, only six modern-day species are known, which exhibit a curiously dispersed distribution. The first species to be brought to scientific notice was the tiny-finned, eel-like garamuru or South American lungfish Lepidosiren paradoxa, when in 1837 Dr Johann Natterer captured two specimens — one in a swamp on the Amazon’s left bank, and the other in a pool near Borba, on an Amazon tributary called the Madeira.

Next to be discovered were the four Protopterus species from Africa - P. aethiopicus, P. amphibius, P. annectens, and P. dolloi — slim-bodied with thin lengthy fins. And in 1870 the most primitive modern-day species was formally described from Queensland — Neoceratodus forsteri, the Australian lungfish. Much more robust than the others, with surprisingly sturdy, limb-like fins, and only a single lung (each of the other living lungfish species has a pair), Neoceratodus is considered sufficiently distinct to warrant its own taxonomic family; moreover, its teeth are so similar to those of the archaic fossil genus Ceratodus that it is thought of as a ‘living fossil’.

These, then, are the known present-day lungfishes — which, seemingly for no good reason, lack any type of Asian representative. Or do they? In fact, it is possible that until quite recently there was an extra species, much larger than the others, inhabiting certain swamplands in the Assam region of the Outer Himalayas.

In 1948, news correspondent Ralph Izzard of the London Daily Mail accompanied explorer Charles Stonor on a unique expedition to an eastern Himalayan swamp valley called Rilo, close to Assam’s Dafla Hills. The object of their expedition was to seek a mysterious creature called the buru, of which Stonor had learned during two trips made at the close of World War II with anthropologist J.P. Mills to another valley, to the north-east of these hills, called Apa Tani. According to the Apa Tani natives, the buru had been exterminated here when their ancestors had drained the valley’s swamplands. In contrast, the Rilo natives maintained that it still existed in their valley’s swamps.

Sadly, however, Stonor and Izzard failed to find any evidence for this assertion. Nevertheless, their searches were not wholly in vain. During the Apa Tani expeditions, Mills had meticulously recorded the detailed, quite matter-of-fact descriptions of the buru recounted by the Apa Tanis, which were based upon accounts passed down from their forefathers; and to those were added the largely comparable Rilo versions collected by Stonor and Izzard during their Rilo search. All of this information was carefully documented by Izzard in his subsequent book The Hunt For the Buru (1951), and the following is a summary of this animal’s description.

The buru was elongate, and roughly 11.5-13.5 ft in length - which included a 20-in head with a greatly extended, flat-tipped snout, behind which were its eyes. Its teeth were flattened, except for a single pair of larger, pointed teeth in both the upper and lower jaws, and its tongue was said to be forked. Its neck was about 3 ft long, and capable of being extruded or retracted. Its body was roundish, as was its tail, which tapered towards the tip, measured about 5 ft, and bore broad lobes running along the entire length of its upper and lower edges. The appearance of the buru’s limbs is somewhat uncertain: some of the natives attested that they were well-formed, roughly 20 in long, with claws; others asserted that they were nothing more than paired, lateral flanges, so that the animal seemed rather snake-like. Its skin was dark blue with white blotches and a wide white band down its body’s underside, and resembled that of a scaleless fish in texture.

As for the buru’s lifestyle, it was reputedly wholly aquatic, rarely venturing on to land even for a short time, but sometimes extending its neck above the water surface to utter a loud, bellowing sound. It did not eat fish. Lastly, but of particular interest, the Rilo natives said that when the swamps dried up during the dry season, the buru remained in the layers of mud and sludge on the swamp bottom.

Izzard believed that the buru might have been a modern-day species of dinosaur. Since his book, few writers have mentioned this mystery beast, and its identity remains very much a matter of controversy. In The Leviathans (revised 1976), the late Tim Dinsdale, the world-renowned Loch Ness monster authority, postulated from its description that it could have been some form of crocodile. Cryptozoologist Dr Roy P. Mackal, though, in Searching For Hidden Animals (1980), favoured a large species of water-dwelling monitor lizard. The riddle of the buru has intrigued me for a long time, and, after having given the matter some considerable thought, in this present book’s original incarnation, Extraordinary Animals Worldwide (1991), I offered a third contender - a giant lungfish. As I revealed, this identity provides a compelling correspondence relative to the buru’s general appearance and behaviour.

African Lungfish

African Lungfish One of the most awkward characteristics to explain when attempting to reconcile the buru with a large reptilian species is its tendency to remain ensconced within the swamp-bottom mud when the waters dry up during the dry season. Certainly it seems unlikely that either crocodiles or monitors would (or could) stay submerged in this manner for extended periods of time. In contrast, it is well known that Lepidosiren and two Protopterus species burrow into the mud when their streams dry out during the hot summer months, and remain duly encased, in a resting state called aestivation, until the water returns. Indeed, the first specimen of P. annectens brought to Europe from its native Gambia, in 1837, was transported here whilst still entombed within its cocoon of mud and secreted slime. If the buru is (or was) a lungfish, comparable behaviour could explain its otherwise anomalous actions during the dry season.

The buru’s head was said to terminate in a great snout, flattened at the tip. This is a fair description of the head of Lepidosiren and Protopterus, whose eyes, moreover, are closely aligned behind the snout - another buru characteristic. The teeth of lungfishes consist of rows that yield connected ridges borne on thickened, fan-shaped plates, flattened in form and thus comparing closely with the flattened teeth described for the buru. In some species, smaller tooth-plates occur that are less flattened and separate - these could explain the pointed pairs of teeth reported for the buru.

Lungfishes do not have long necks. However, a modern-day species with the eel-like body of Protopterus or (especially) Lepidosiren but with pectoral fins positioned further back on its body (thus paralleling the condition present in some extinct lungfish species) could appear to the untrained observer to have a long ‘neck’, as described for the buru. The buru’s round body and tapering tail are features exhibited by modern-day lungfishes, and the lobes of the buru’s tail could be explained as merely a slight elaboration of the normal tail-fin possessed by all living lungfishes (a characteristically primitive, pointed type referred to as being protocercal). Furthermore, the tail-fin of Protopterus is indeed split dorsally into slight flukes.

As for the buru’s limbs, the lungfish identity can provide a close correspondence whether they were true limbs with clawed feet (according to some native reports), or merely paired lateral flanges that made the animal seem snake-like (according to certain other native reports). On the one hand, Australia’s Neoceratodus has sturdy flipper-like pelvic and pectoral fins, with rough spiny edges that do resemble claws. And on the other hand, the fins of Protopterus and Lepidosiren are indeed little more than paired lateral flanges with no real resemblance to limbs, thereby enhancing these fishes’ anguinine appearance - to the extent that they could seem quite serpentine to a casual observer.

In actual fact, it is even possible that the buru had both types of limb (which would resolve the controversy regarding their shape). Like so many fish species, it might have been sexually dimorphic (i.e. possessing morphologically dissimilar sexes), with the limbs of one sex (probably the male) of more robust construction than those of the other.

The buru’s skin allegedly resembled that of a scaleless fish; closely conforming once again, the scales of Protopterus and Lepidosiren are concealed under a soft outer skin, so that they appear superficially scaleless. Also, whereas Lepidosiren and Neoceratodus are mostly brown in colour, Protopterus is pale pinkish-brown with dark blue-black blotches, so that it would not require too drastic a change in colour scheme to produce the buru’s bluish-brown shade and white blotches. Moreover, it is interesting to note that Africa’s Latimeria chalumnae, that celebrated lobe-finned fish known as the coelacanth – one of only two known survivors of an ancient piscean lineage (the other is the recently discovered Indonesian coelacanth L. menadoensis) and classed by some as the lungfishes’ closest living relative - is steely-blue in colour and dappled with numerous white blotches, only fading to a dull brown following its death.

The buru was alleged to be emphatically aquatic, rarely venturing onto land and never spending any length of time there. However, the natives stated that sometimes it had been seen raising its head up out of the water and making a bellowing noise. This scenario is one that has strong lungfish associations for me.

One of the most popular exhibits of the ichthyological practicals during my days as a zoology student at university was a living specimen of an African lungfish Protopterus, which was sometimes placed on display in order that we could observe its behaviour. As it happened, for much of the time there was actually very little that we could observe, because it would spend most of the practical resting motionless at the bottom of its tank. Every so often, however, and usually when everyone’s attention was diverted elsewhere, it would solemnly perform its pièce de resistance. All at once, without any prior warning, it would raise the front part of its large body upwards, until its head just touched the surface of the water. Sometimes it would then simply nudge the tip of its snout above the water surface, but if we were lucky (by now, everyone would have rushed up to its tank to watch its celebrated performance) it would actually raise its entire head, after which it would remain in this position for several minutes, ventilating.

South American lungfish

South American lungfish Although lungfishes have external nostrils, they breathe through their mouth, positioned at the very tip of the snout. This intake of air, readily perceived visually by the movements of its mouth and throat (proving that the lungfish is genuinely swallowing air) can also be very audible. The size of the buru was such that if it were truly a lungfish, the bellowing noise reported when its head was visible above the water might well have been the very audible result of its ventilation period.

According to native testimony, the buru was not piscivorous - in stark contrast to crocodiles and aquatic monitors. But what about lungfishes? It has been demonstrated that the diet of Protopterus depends upon its body size. Up to 1 ft long, it eats only insect larvae; between 1 and 2 ft, its diet is a mixture of insect larvae, snails, and the occasional fish; above 2 ft, it eats only snails. Among the other lungfishes, crustaceans are also popular (as is plant material with Neoceratodus). Thus a diet in which fish is only an insignificant inclusion is typical for lungfishes.

All in all, there would seem to be only one noteworthy discrepancy between the buru’s appearance and that of lungfishes - its forked tongue. This is a feature typical of monitors, certain other lizards, and snakes, but not of lungfishes. In view of the overwhelming degree of correspondence with lungfishes on other morphological grounds, however, it is quite probable that this feature was not a genuine component of the buru’s make-up, but rather a fictional flourish — especially as it is common amongst primitive tribes from many parts of the world to ascribe a forked tongue to a creature (sometimes even to another tribe’s members) that they fear or dislike.

In summary, on virtually every count a lungfish identity corresponds more than adequately with native descriptions of the buru. Overall, it seems to compare most closely with the elongate Lepidosiren or Protopterus, but its much larger size and possible Neoceratodus-like fins imply that it would have probably required a brand-new genus.

Worthy of brief mention is a second putative identity for the buru involving a strange type of freshwater fish (again previously unconsidered), a type which, although totally unrelated to lungfishes, provides some striking parallels with them, and hence with the buru. Last survivors of an ancient line, the bonytongues or osteoglossids have an oddly discontinuous distribution, existing in northern Australia, south-east Asia, West and Central Africa, and eastern South America - thus almost precisely mirroring the distribution of the lungfishes, except, of course, for Asia. Moreover, they are long, cylindrical species, the most famous being the mighty 7-ft-long arapaima or pirarucu Arapaima gigas of South America, with flattened head and snout, oddly shaped fins, and, most intriguing of all, an air-bladder modified as a lung - all features again exhibited by the lungfishes.

Most striking of all in terms of parallel lifestyles, however, is the bonytongues’ method of breathing. For most of the time they remain beneath the water surface, but every so often they raise their body upwards, and poke their mouth up through the surface to gulp air. Sounds familiar? On the other hand, unlike some lungfishes, bonytongues do not aestivate.

Nevertheless, it would require greater morphological changes to reconcile the buru with a bonytongue (even though there are already Asian forms) than with a lungfish. True, opponents of the lungfish identity might argue that the absence of any form of modern-day lungfish from Asia (though various fossil species have been found here) is a major obstacle to overcome. However, there is one final item of information that I have still to offer in favour of the lungfish identity, an item that could effectively provide this theory’s missing segment of credibility.

During my correspondence with Dr Roy Mackal regarding the buru, he informed me that he has collected excellent anecdotal reports that point to the existence in Vietnam of a 6-ft-long species of lungfish. Apart from being a zoological sensation, the discovery of such a creature would provide very considerable support for the identity of the buru as a larger, related species.

Clearly, as was shown in 1930 when the sole specimen of the enigmatic Australian paddle-nosed lungfish Ompax spatuloides was exposed as a hoax (constructed from a Neoceratodus head, mullet body, and platypus beak!), the lungfishes have a continuing potential for inciting violent controversy among scientists.

Australian lungfish

Australian lungfish

Published on August 05, 2012 14:59

August 4, 2012

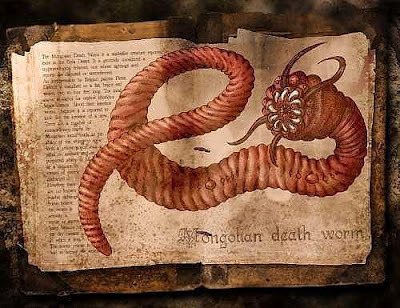

THE MONGOLIAN DEATH WORM – A SHOCKING SURPRISE IN THE GOBI?

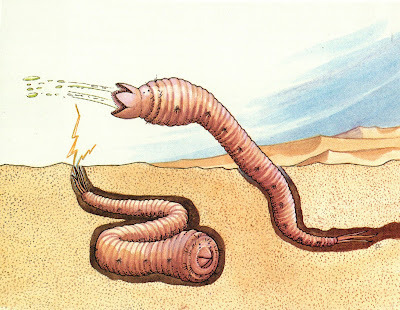

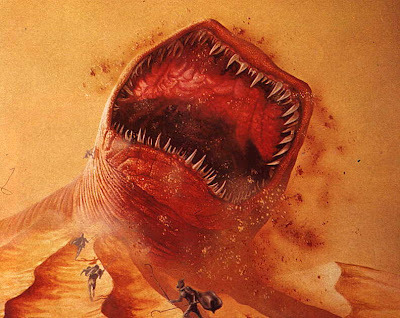

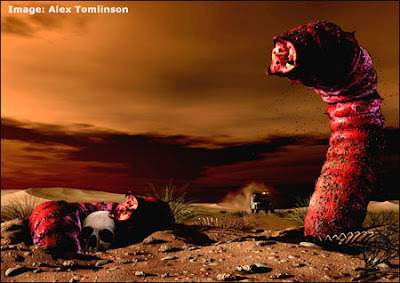

The Mongolian death worm - shocking and spraying! (Philippa Foster)

The Mongolian death worm - shocking and spraying! (Philippa Foster)It's not every day – or every expedition – that begins with a request from a country's head of government formally requesting that a specimen be captured of a creature so elusive, and deadly, that western science does not even recognise its existence. Nevertheless, that is precisely what happened in 1922 when eminent American palaeontologist Prof. Roy Chapman Andrews met the Mongolian premier in order to obtain the necessary permits for the American Museum of Natural History's Central Asiatic Expedition to search for dinosaur fossils in the Gobi Desert. And the creature that the Mongolian premier instructed him to procure? None other than the lethal allghoi khorkhoi – or, as it is nowadays commonly referred to throughout the world, the Mongolian death worm.

Ivan Mackerle (Ivan Mackerle)

Ivan Mackerle (Ivan Mackerle)Although in the 1920s, this extraordinary mystery beast was totally unheard of outside Mongolia, today it is one of the most (in)famous of all cryptozoological creatures – thanks to the series of pioneering expeditions to its southern Gobi homeland launched by Czech explorer Ivan Mackerle, the first of which took place during June and July 1990, and which subsequently attracted considerable interest internationally. During his searches, Ivan collected a very impressive dossier of information concerning the death worm, based upon eyewitness reports and other anecdotal evidence, which he subsequently made freely available to me to use as I wished in my own writings, and which can be summarised as follows.

Its local names – allghoi khorkhoi and allergorhai horhai – translate as 'intestine worm', because according to eyewitness testimony, this mysterious sausage-shaped creature resembles a living intestine. Red in colour with darker blotches, it measures 1-1.6 m long and is as thick as a man's arm, but has no discernable scales, mouth, nor even any eyes or other recognisable sensory organs. It is said to be truncated at both ends, but according to some accounts at least one end also bears a series of long pointed structures at its tip.

Illustration of Mongolian death worm based upon eyewitness descriptions (Ivan Mackerle)

Illustration of Mongolian death worm based upon eyewitness descriptions (Ivan Mackerle)For much of the year, the death worm remains concealed beneath the Gobi's sands, but during the two hottest months – June and July – it can sometimes be encountered lying on the surface, particularly after a downpour of rain.

Black saxaul

Black saxaulLocals claim that it can also be found in association with the black saxaul Haloxylon ammodendron, a yellow-flowered desert shrub, whose roots are parasitized by the goyo Cynomorium songaricum – a strange, cigar-shaped plant of uncertain taxonomic affinities.

Goyo plants (Ivan Mackerle)

Goyo plants (Ivan Mackerle)According once again to local lore, the death worm is deadly for two very different reasons. If approached too closely, it is said to raise one end of its body upwards (as portrayed on the front cover of my book The Beasts That Hide From Man, 2003), and then squirt with unerring accuracy at its victim a stream of extremely poisonous, acidic fluid that burns the victim's flesh, turning it yellow, before rapidly inducing death. It is claimed that the death worm derives this highly toxic substance externally - either from the saxaul's roots or from the goyo attached to them (and thereby reminiscent of how South America's deadly arrow-poison frogs derive their skin toxins from certain small arthropods that they devour). During my own researches, however, I have uncovered no evidence to suggest that the saxaul's roots are poisonous, and I have revealed that the goyo is definitely not poisonous (it is eaten as famine food, and used widely in Chinese herbalism). So if the death worm truly emits a venomous fluid, it presumably manufactures it internally, rather than deriving it externally.

Model of Mongolian death worm emerging from sand (Markus Bühler)

Model of Mongolian death worm emerging from sand (Markus Bühler)Even more shocking – in every sense! – is the death worm's second alleged mode of attack. Nomadic herders inhabiting the southern Gobi tell of how entire herds of camels have been killed instantly merely by walking over a patch of sand concealing a death worm beneath the surface. Moreover, one of Ivan Mackerle's local guides recalled how, many years earlier, a geologist visiting the Gobi as part of a field trip was killed when he began idly poking some sand one night with an iron rod – as he did so, he abruptly dropped to the ground, dead, for apparently no reason, but when his horrified colleagues rushed up to him, they saw the sand where he had been poking the rod suddenly begin to churn violently, and from out of it emerged a huge, fat death worm.

The camels presumably died from coming into direct physical contact with the death worm hidden beneath their feet, but the geologist only touched it indirectly, via the metal rod. Consequently, the only conceivable way that this action could have caused his death is by electrocution – which would obviously explain the camels' instant deaths too. Although there are several different taxonomic groups of fish containing species that can generate electricity – including the famous electric eel and gymnotids, as well as the electric catfish, electric rays, mormyrids, rajid skates, and electric stargazers – no known species of terrestrial creature possesses this ability. So if the native claims concerning the camels and the geologist are correct, and always assuming of course that it really does exist, the death worm must be a very special animal indeed. But what precisely could it be?

Mongolian death worm (www.static.environmentalgraffiti.com)

Mongolian death worm (www.static.environmentalgraffiti.com)Despite its English name and superficially similar external appearance, it is highly unlikely that the death worm could be a bona fide earthworm or related invertebrate. For although some earthworms do grow to prodigious lengths, and certain species known aptly as squirters even spurt streams of fluid from various body orifices, none exhibits a water-retentive cuticle, which would be imperative for survival in desert conditions to avoid drying out. Of course, there may be a highly-specialised earthworm in the Gobi that has indeed evolved such a modification, but with no precedent currently known, the chances of this seem slim. In addition, if the death worm's powers of electrocution are real, this would require even more modification and specialisation for an earthworm to fit the bill.

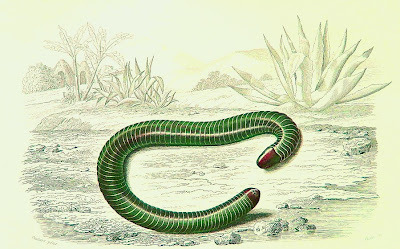

Caecilians constitute a taxonomic order of limbless amphibians that are deceptively worm-like in appearance and predominantly subterranean in lifestyle. Certain species can also attain a total length matching the dimensions reported for the death worm. As with true worms, however, caecilians' skin is water-permeable, so once again even a giant caecilian would soon dry out in the arid Gobi, unless, uniquely among these particular amphibians, it had evolved a water-retentive skin.

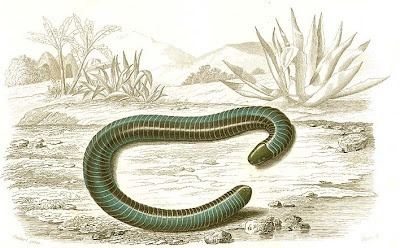

19th-Century engraving of a caecilian, Siphonops

19th-Century engraving of a caecilian, SiphonopsIf the death worm is genuine, it is almost certainly some form of reptile. To my mind, the likeliest solution is an unusually large species of amphisbaenian. On account of their vermiform appearance (most species are limbless), these little-known reptiles are also called worm-lizards, even though, taxonomically speaking, they are neither. As with caecilians, they spend much of their lives underground, rarely coming to the surface except after a heavy fall of rain. This all corresponds well with the death worm's reported behaviour. Furthermore, unlike real worms and caecilians the skin of amphisbaenians is water-retentive, so a giant species would not dry out in the Gobi.

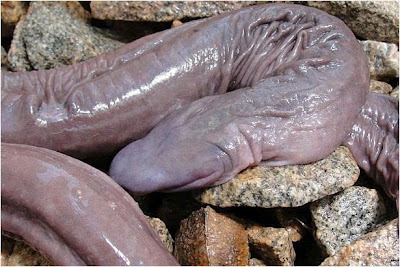

Two Iberian amphisbaenians Blanus cinereus (Richard Avery/Wikipedia)

Two Iberian amphisbaenians Blanus cinereus (Richard Avery/Wikipedia)Conversely, whereas the death worm is said to be smooth externally, amphisbaenians are very visibly scaly, and they also have a readily-observed mouth. In addition, they are all completely harmless, which wholly contradicts the twin death-dealing talents attributed to the Gobi's moat greatly-feared denizen. Naturally, it is conceivable that these abilities are entirely apocryphal, nothing more substantial than superstitious fancy. After all, several known species of amphisbaenian, and also caecilian, are fervently believed by their local human neighbours to be deadly poisonous even though in reality they are wholly innocuous.

19th-Century engraving of an amphisbaenian

19th-Century engraving of an amphisbaenianMuch of what has been proposed for and against an amphisbaenian identity for the Mongolian death worm applies equally to the possibility of its being an unknown species of very large legless true lizard - akin perhaps to the familiar slow worm and glass snake, or even to the skinks, some species of which are limbless. However, these lizards are much less worm-like and subterranean than amphisbaenians, so overall the latter provide a more satisfactory match with the death worm.

Mexican ajolote - possessing a pair of extremely small forelegs, this is the only type of amphisbaenian with any limbs at all (picture source unknown to me)

Mexican ajolote - possessing a pair of extremely small forelegs, this is the only type of amphisbaenian with any limbs at all (picture source unknown to me)Last, but by no means least, is the thought-provoking prospect that the death worm may be a highly specialised species of snake. Not only do most of the above-noted physical and behavioural similarities between the death worm and the amphisbaenians and legless lizards apply here too, but spitting cobras also offer a famous precedent for an elongate creature that can eject a stream of corrosive venom with deadly accuracy at a potential aggressor. Moreover, the spine-bearing tip described for the death worm recalls a genus of cobra-related species known as death adders Acanthophis spp., which possess a spiny worm-like projection at the tip of their tail that acts as a lure for potential prey.

Death adder

Death adderTheir name recognises the fact that although, like cobras, they are elapids, the death adders have evolved to occupy the ecological role filled elsewhere by true vipers. Could there be a specialised, unknown species of death adder that has evolved the venom-spitting ability of its spitting cobra relatives? If so, this would vindicate the locals' testimony concerning the death worm's emissions. But what about its alleged powers of electrocution?