Karl Shuker's Blog, page 63

July 30, 2012

SWAMP CRITTERS AND SAND WORMS - INTRODUCING THE SPECTACULAR IMAGINARIUM OF ANDREW SCOTT

Beasty and various other creations of Andrew Scott

Beasty and various other creations of Andrew ScottOne of the chief delights for me in joining Facebook has been meeting and becoming friends with so many interesting people – some of whom, moreover, are gifted with the most extraordinary and wonderful talents. One such person is Andrew Scott from Vancouver in British Columbia, Canada, whose ability to manufacture astonishingly life-like models of real and imaginary animals is truly breathtaking. Using acrylic on PVC gel and iron wire or copper and aluminium for many of them, each of his numerous sculptures has been skilfully created by him with meticulous attention to detail, and the result is never less than mesmerising.

Now, with Andrew's kind permission, I am delighted to be able to present here an exclusive ShukerNature showcase of his spectacular work – a unique imaginarium of wonders, marvels, and terrors the likes of which you will never have seen before nor are likely ever to see again. So sit back, eyes at the ready, and prepare to be amazed!

Needless to say, as a cryptozoologist I am particularly fascinated by Andrew's eclectic assortment of mystery and imaginary beasts – a wholly original museum of unnatural history, in fact, whose specimens' decidedly strange, even alienesque features are guaranteed to delight and disturb in equal measure!

CREATURES OF CRYPTOZOOLOGY

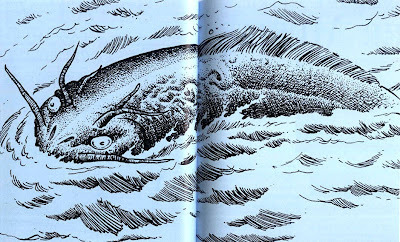

One of my personal favourites from Andrew's menagerie of crypto-models is his Zeuglodon – an evolved, present-day version of which is a popular identity among cryptozoologists for various elongate lake and sea monsters.

Zeuglodon

ZeuglodonAnother crypto-celebrity produced in model form by Andrew, utilising acrylic and foam rubber, is the giant squid.

Giant squid

Giant squidAndrew has yet to prepare a Mongolian death worm (though he has plans to do so), but he has already produced something comparable, which he refers to as a Sand Worm. As can be seen here, it is armed with a cluster of tentacles at its anterior end, plus a triangle of tiny ocelli (eye-spots) on top of its head and an additional pair sited laterally. It is this minute degree of detail present in all of Andrew's works that I find so captivating, from both a purely aesthetic and a strictly scientific viewpoint.

Sand Worm

Sand WormAndrew's Chupacabra is not for the faint-hearted. A terrifying bristle-backed biped armed with formidable talons and sizeable fangs, there is no doubt that this green-skinned, hunch-backed horror would strike fear into the heart of anything that it encountered, and provide years of nightmares for anything that survived such an encounter.

Chupacabra

ChupacabraAnd speaking of nightmares...

NATURE'S NIGHTMARES

Warning: This section contains slimy tentacles – lots of them!!

It is perhaps with Nature's nightmarish side that Andrew really comes into his own, permitting his imagination to wander down the darker paths and byways of evolution to conjure forth an array of overtly bizarre and sometimes physically shocking life-forms, yet invariably executed with exemplary showmanship flair and expert structural insight.

Take, for instance, the Swamp Critter. Dramatically dissimilar from anything within Earth's catalogue of known, modern-day organisms, it vaguely resembles something called into being from the archaic Burgess Shale ecosystem present at the onset of life on our planet. However, it is even stranger and decidedly more sinister – thanks in no small way to that conspicuously large, sharp-looking claw at the tip of its elongated body, its plethora of vermiform tentacles, and the unnerving ability of its anterior body portion to rear upwards, rather like a cobra about to strike.

Swamp Critter

Swamp CritterNo less settling to the mind is what Andrew terms the Baby Deep One, because this is his concept of what H.P. Lovecraft's Deep Ones looked like as infants. Dorsally, it resembles a curled, gelatinous larva with little in the way of distinguishing features other than three short projections borne upon what appears to be this bizarre entity's neck region, and a pattern of short ridges running down its back. Turn it over, however, and you are met with a writhing mass of slimy tentacles, resembling a host of twisting, intertwined worms coated in glistening mucus. As with all of Andrew's sculptures, the technical accomplishment is dazzling – even the creature's slime looks ready to drip off its tentacles at any moment.

Baby Deep One, two views

Baby Deep One, two viewsClick here to discover how Baby Deep One was created by Andrew.

Yet another of Andrew's beasts supplied with a plenitude of tentacles is the Crawler. Dorsally, its crenulated external surface recalls that of a woodlouse, but ventrally its tentacles betray a very different zoological identity and origin.

Crawler

CrawlerOcelli and tentacles are trademarks of Andrew's zoological design, and both figure extensively in Beasty, together with a vicious-looking pair of lateral jaws.

Beasty

BeastyEven more impressive, however, are the huge jaws of the Crazy Critter (in reality a purchased pair of genuine wolf-eel jaws), which otherwise resembles a centipede, but with tentacles instead of legs.

Crazy Critter

Crazy CritterIn the Sand Creature, the ocelli have been replaced by fully-fledged eyes, and the tentacles are arranged in lateral clumps.

Sand Creature

Sand CreatureAs for Baby: well, it has certainly never been more true that only a mother could love it! Armed with Andrew's customary abundance of tentacles, a jutting lower jaw brimming with teeth, and a long tail, this globular grotesque is definitely NOT pretty in pink (but readily emphasises the sick in cyclamen), and calls to mind a cryptozoological Eraserhead. In fact, Baby was indeed designed by Andrew specifically for a horror film, but sadly the film was never completed.

Baby

BabyRemember those disgusting little wingless insects known as silverfish that sometimes turn up in fire grates, kitchens, or bathrooms? Imagine if one of them mutated, growing larger in size, turning a lurid pink in colour, and seeking out a more intimate dwelling place – the human brain? If that pleasant little thought hasn't already given you nightmares, here's Andrew's brainworm!

Brainworm

BrainwormAnd don't even get me started on his Triloslug and his Martian Maggot – the latter is clearly one for the exobiologists.

Triloslug (left) and Martian Maggot (right)

Triloslug (left) and Martian Maggot (right)Two more weirdly wonderful creations designed as ever with Andrew's painstaking care and precision – as is the wonderfully-named Sea Pineapple of Death.

Sea Pineapple of Death

Sea Pineapple of DeathThis vaguely squid-like marine organism with a pineapple-redolent body sports a ring of eyes encircling its head, and two threesomes of tentacles - one set long, the other set short.

Not all of Andrew's creations are of Earth origin, as exemplified not only by his Martian Maggot but also by his Alien Embryo.

Alien Embryo

Alien EmbryoTentacles, as ever, are liberally supplied, but it is difficult to speculate what this entity may ultimately become – which is perhaps no bad thing, especially for those of a nervous disposition!

AN INORDINATE FONDNESS FOR BEETLES

British geneticist Prof. J.B.S. Haldane is best-remembered outside genetics for his oft-quoted reply when once asked what inferences could be drawn about the nature of God from a study of His works: "An inordinate fondness for beetles".

Carabid beetle model

Carabid beetle modelA study of Andrew's models would suggest that he shares a similar degree of fondness for such insects, as his collection includes a wide range of beetles.

Seven-spotted ladybird model

Seven-spotted ladybird modelFurthermore, so true to life are they that had I not already known them to be models, looking at their pictures I would have assumed that I was viewing examples of macro-photography featuring bona fide beetles.

Pupa model

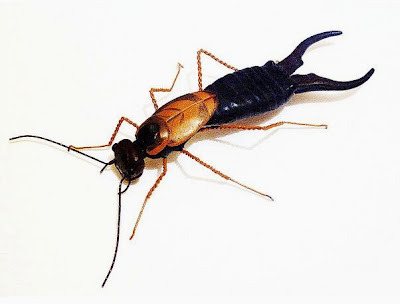

Pupa modelSimilarly, the exceptional degree of verisimilitude exhibited by this model makes it very easy to forget that this really is 'just' a sculpture and not a genuine earwig, ready to scuttle away at any moment.

Earwig model

Earwig modelAndrew also has a passion for trilobites, and again he has produced models of several different types. The following example, belonging to the species Bristolia bristolensis, is particularly eyecatching.

Bristolia bristolensis trilobite

Bristolia bristolensis trilobiteAs varied and as numerous as they are, the examples presented here are just a small selection of Andrew's prodigious output of models and sculptures, which readily convey the vast scope, expertise, and inventiveness of the mind and imagination that created them. One of his models drew a comment from a viewer who compared Andrew to the celebrated Dutch artist Hieronymus Bosch (c.1450-1516) – famed for his extraordinary triptych painting 'The Garden of Earthly Delights', which is filled with fantastic figures and beasts.

'The Garden of Earthly Delights' (Hieronymus Bosch)

'The Garden of Earthly Delights' (Hieronymus Bosch)To my mind, this is a valid comparison, because Andrew's creations demonstrate a breadth and depth of vision so profound and proliferate that just as Dr Bernard Heuvelmans was called the Sherlock Holmes of cryptozoology, it would be no exaggeration to call Andrew Scott the Hieronymus Bosch of (un)natural history.

Andrew recently mentioned to me that he will be attempting a model of the Mongolian death worm, a cryptid famed for its alleged powers of electrocution. Consequently, I now await this with keen delight, albeit with a degree of trepidation too. For if Andrew's death worm is (as it surely will be) as realistic as all of his other animal models, it may prove to be a shocking experience – in every sense!

Andrew's study, showing some of his many creations

Andrew's study, showing some of his many creationsIMPORTANT: The copyright of all photographs included in this ShukerNature blog post belong to Andrew Scott, and these photographs must not be reproduced without his written permission.

Published on July 30, 2012 19:01

July 29, 2012

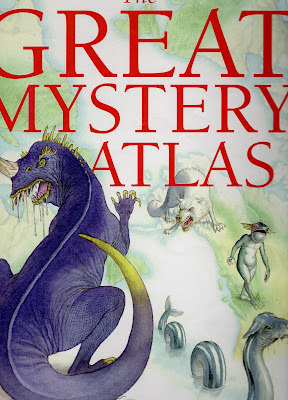

'THE GREAT MYSTERY ATLAS' - THE BOOK THAT GOT AWAY

I have been very fortunate during more than 20 years as a full-time author in that virtually every book that I have personally submitted for publication or have been involved with in some capacity has duly appeared in print. During the mid-1990s, however, there was one notable exception to this successful trend.

It was provisionally entitled The Great Mystery Atlas: A Pictorial Guide to Mysterious Creatures and Places. I had been contracted by a leading British publisher (whose identity for reasons of professional confidentiality and courtesy I shall not disclose here) to write the text for it, and an artist, Stephen Player, had been contracted to prepare its illustrations. With a very significant cryptozoological and zoomythological content, this large-format, full-colour book, aimed at older children and early teenagers, promised to be a noteworthy addition to the literature as well as a good seller.

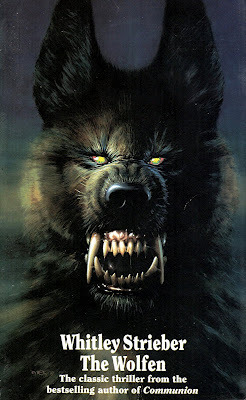

Left-hand page of the 'Land of the Yeti' spread

Left-hand page of the 'Land of the Yeti' spreadHence I lost no time in writing its complete text, which was greeted with great enthusiasm when received and read by the editors, and for which, happily, I was paid in full very shortly afterwards.

Right-hand page of the 'Land of the Yeti' spread

Right-hand page of the 'Land of the Yeti' spreadUnfortunately, however, certain aspects of the book's production that were completely unrelated to my contribution experienced some apparently intractable problems, as a result of which the entire project was shelved, and then subsequently cancelled. Having already seen and approved the first two double-page spreads for it as well as a draft version of its front cover by then, I was very disappointed by its cancellation, because their sumptuous appearance suggested that the complete book would have been truly spectacular.

Left-hand page of the 'Bigfoot Territory' spread

Left-hand page of the 'Bigfoot Territory' spreadSadly, though, it was not to be, and today all that I have to show for what might have been are those spreads and the cover. So now, as a ShukerNature exclusive, here they are – from the book that got away.

Right-hand page of the 'Bigfoot Territory' spread

Right-hand page of the 'Bigfoot Territory' spreadNB: because the spreads' pages and the cover were bigger than A4-size, whereas I only have an A4-size plate on my scanner, I have been unable to scan them in their entirety – some text and images around their edges have been cut off during the scanning procedure.

All illustrations included here (of the spreads and cover) are jointly copyrighted to the publisher, Stephen Player, and myself.

Published on July 29, 2012 15:19

July 28, 2012

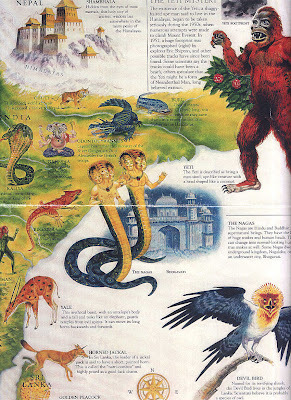

WULVERS AND WOLFEN AND WEREWOLVES, OH MY!! - TALES OF THE UNINVITED

Wolf-men appear in the mythology of many cultures worldwide (Richard Svensson)

Wolf-men appear in the mythology of many cultures worldwide (Richard Svensson)One of the most unusual examples of the werewolf movie genre was the film 'Wolfen' (1981), based upon the novel The Wolfen (1978) by Whitley Strieber. Albert Finney starred as a Manhattan detective searching for a mysterious, elusive, and exceedingly intelligent species of highly-evolved humanoid wolf, which has been preying upon humans from the earliest times and is responsible for the werewolf legends but has never been revealed by science. Of course, wolfen are wholly fictional...aren't they?

Front cover of my copy of Whitley Strieber's novel The Wolfen; this is the 1992 reissue of Coronet Books' 1979 paperback edition (Dr Karl Shuker)

Front cover of my copy of Whitley Strieber's novel The Wolfen; this is the 1992 reissue of Coronet Books' 1979 paperback edition (Dr Karl Shuker)Similarly, world mythology is amply supplied with wolf-headed humans or wolf-men. These include ancient Egypt's jackal-headed god of the dead, Anubis; the evil king of Thessaly, Lycaon, transformed into a wolf by Zeus but often portrayed as a wolf-headed man; the cynocephali of India; and even St Christopher, frequently depicted as a dog-headed human. Moreover, the British Isles is famously rich in fabulous monsters, one of which is the wulver - a reclusive wolf-headed humanoid from Shetland mythology, which is covered in short brown hair, lives in caves dug out of steep hills, and enjoys fishing. Once again, however, wulvers are entirely legendary...or are they?

Medieval colour illustration of some cynocephali supposedly sighted by Marco Polo in the Andaman Islands

Medieval colour illustration of some cynocephali supposedly sighted by Marco Polo in the Andaman IslandsThere is an unsettling number of reports on file describing reputedly authentic encounters with wolf-men. These include the following pair of spine-chilling incidents, each featuring an extraordinary skull and the even more extraordinary events that followed its discovery.

Southwest of the Shetlands is another group of Scottish islands - the Hebrides or Western Isles. According to ghost-hunter Elliot O'Donnell's book Werewolves (1912), these were once the setting for a frightening encounter with a decidedly malign wulver-like beast. Several years earlier, O'Donnell had taken down the testimony of the wolf-man eyewitness, a Mr Warren (named as Andrew Warren in an account of this episode included by Graham McEwan in his book Mystery Animals of Britain and Ireland, 1986), who claimed that his creepy experience had occurred while he was a teenager, staying in the Hebrides:

"I was about fifteen years of age at the time, and had for several years been residing with my grandfather, who was an elder in the Kirk [Church] of Scotland. He was much interested in geology, and literally filled the house with fossils from the pits and caves round where we dwelt. One morning he came home in a great state of excitement, and made me go with him to look at some ancient remains he had found at the bottom of a dried-up tarn [lake]. 'Look!' he cried, bending down and pointing at them, 'here is a human skeleton with a wolf's head. What do you make of it?' I told him I did not know, but supposed it must be some kind of monstrosity. 'It's a werwolf[sic]! he rejoined, 'that's what it is. A werwolf! This island was once overrun with satyrs and werwolves! Help me carry it to the house.' I did as he bid me, and we placed it on the table in the back kitchen. That evening I was left alone in the house, my grandfather and the other members of the household having gone to the kirk. For some time I amused myself reading, and then, fancying I heard a noise in the back premises, I went into the kitchen. There was no one about, and becoming convinced that it could only have been a rat that had disturbed me, I sat on the table alongside the alleged remains of the werwolf, and waited to see if the noises would recommence. I was thus waiting in a listless sort of way, my back bent, my elbows on my knees, looking at the floor and thinking of nothing in particular, when there came a loud rat, tat, tat of knuckles on the window-pane. I immediately turned in the direction of the noise and encountered, to my alarm, a dark face looking in at me. At first dim and indistinct, it became more and more complete, until it developed into a very perfectly defined head of a wolf terminating in the neck of a human being. Though greatly shocked, my first act was to look in every direction for a possible reflection - but in vain. There was no light either without or within, other than that from the setting sun - nothing that could in any way have produced an illusion. I looked at the face and marked each feature intently. It was unmistakably a wolf's face, the jaws slightly distended; the lips wreathed in a savage snarl; the teeth sharp and white; the eyes light green; the ears pointed. The expression of the face was diabolically malignant, and as it gazed straight at me my horror was as intense as my wonder. This it seemed to notice, for a look of savage exultation crept into its eyes, and it raised one hand - a slender hand, like that of a woman, though with prodigiously long and curved finger-nails - menacingly, as if about to dash in the window-pane. Remembering what my grandfather had told me about evil spirits, I crossed myself; but as this had no effect, and I really feared the thing would get at me, I ran out of the kitchen and shut and locked the door, remaining in the hall till the family returned. My grandfather was much upset when I told him what had happened, and attributed my failure to make the spirit depart to my want of faith. Had he been there, he assured me, he would soon have got rid of it; but he nevertheless made me help him remove the bones from the kitchen, and we reinterred them in the very spot where we had found them, and where, for aught I know to the contrary, they still lie."

Quite aside from its highly sensational storyline, it is rather difficult to take seriously any account featuring someone (Warren's grandfather) who seriously believed that the Hebrides were "...once overrun with satyrs and werwolves"! By comparison, and despite his youthful age, Warren's own assumption that the skeleton was that of a deformed human would seem eminently more sensible - at least until the remainder of his account is read. Notwithstanding Warren's claim that his account was factual, however, the arrival of what was presumably another of the deceased wolf-headed entity's kind, seeking the return of the skeleton to its original resting place, draws upon a common theme in traditional folklore and legend.

King Lycaon, portrayed in this 16th-Century copperplate engraving by Italian artist Agostino de' Musi as a ferocious wolf-headed man comparable to the entity reported by Andrew Warren

King Lycaon, portrayed in this 16th-Century copperplate engraving by Italian artist Agostino de' Musi as a ferocious wolf-headed man comparable to the entity reported by Andrew WarrenAs documented in Werewolves (1933) by the Reverend Montague Summers, an authority on such entities, the second of the two bloodcurdling episodes to be considered here occurred in summer 1888, and featured a professor from Oxford who had rented a holiday cottage in a mountainous area of Merionethshire, Wales. During his stay there, the professor decided to go fishing one day in a local lake, and while doing so he hooked an unusual object that proved to be the skull of an extremely large dog-like beast. Curious to discover more about his unusual catch, he took the skull back to the cottage, but left it in the kitchen when he went out for the evening with a friend, leaving his wife alone in the cottage.

While they were away, the professor's wife suddenly heard a strange snuffling sound outside the kitchen door, but when she went into the kitchen she saw to her horror the face of a terrifying red-eyed beast, seemingly part-human and part-wolf, outside the window, grasping the window ledge with paws that resembled hands. Greatly frightened, she ran back to the front door of the cottage and bolted it - just in time. Moments later, the monster was panting outside, and rattling the door's latch. Unable to open the door, it paced round and round the cottage, snarling and growling with rage as it vainly sought some way to enter, until eventually it departed, leaving the petrified woman shaking with fear inside.

When her husband returned with their friend, they made absolutely sure that the house was totally secure, and then sat waiting with stout sticks and a gun at the ready, in case the wolf-man, werewolf, wulver, or whatever it was, returned - which it did.

Holding a figure which may resemble the wolf-man that besieged the professor's holiday cottage in Wales (Dr Karl Shuker)

Holding a figure which may resemble the wolf-man that besieged the professor's holiday cottage in Wales (Dr Karl Shuker)Later that same night, as the cottage lay enshrouded in a still darkness, its three alert occupants heard the soft crunching of paws upon the gravel outside, then the scratching of nails or claws against the kitchen window. And, to quote Summers, as they peered towards the sound: "...in a stale phosphorescent light they saw the hideous mask of a wolf with the eyes of a man glaring through the glass, eyes that were red with hellish rage". They raced to the door, but their quarry had heard them, and as they opened it they could just discern a huge form racing into the lake, and disappearing from view beneath the surface.

There seemed only one way of bringing this living nightmare to a close. So as soon as it was light, the professor left the cottage, rowed out into the lake, and hurled the mysterious skull as far as possible into the lake's depths. Returning the skull from whence it had come evidently restored an equilibrium of sorts, because its semi-lupine seeker never returned.

Coupled with its melodramatic storyline, this case's absence of names via which its details could be independently checked or pursued by other researchers does not bode well for its verisimilitude. Of course, it could be that the professor and the others did indeed exist but did not wish their identities to be made public - which, though perfectly understandable, is hardly beneficial in furthering the case's claims to authenticity.

What big teeth you have! (Richard Svensson)

What big teeth you have! (Richard Svensson)Even more worrying, however, is this case's profound similarity to the earlier one, documented by O'Donnell. In both histories, a large canine skull (one in isolation, the other attached to a human skeleton) is found in a lake (one still containing water, the other dried up), brought back to the finder's residence, and left there in the kitchen during the evening with only a single person in the house. This person is duly confronted at the kitchen window by a terrifying face and hand(s) - presumably a living representative of the skull's species (described in near-identical manner within the two histories) searching for it. Although the entity is ultimately frustrated, it has elicited sufficient fear for the skull's finder to return the skull to its place of discovery, after which the entity is not seen again.

All the better to bite you with!! (Richard Svensson)

All the better to bite you with!! (Richard Svensson)Yet even if we dismiss Summers's case as a piece of fiction inspired by O'Donnell's report, there are others still to account for, some of which are again included in O'Donnell's book and McEwan's. Hence it is a great pity that the remains reputedly found by Warren's grandfather were never examined by a qualified zoologist. After all, how often in modern times has science been presented with the skeleton of a mythical entity for formal scrutiny?

Wolf magic!

Wolf magic!

Published on July 28, 2012 12:25

July 26, 2012

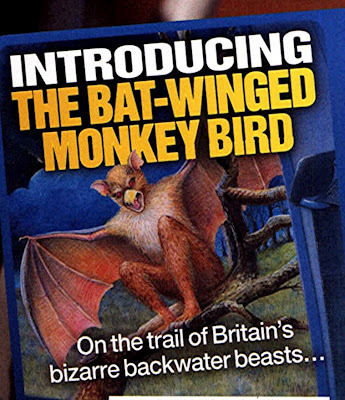

INTRODUCING BRITAIN’S BAT-WINGED MONKEY-BIRD

Artistic representation of Britain's bat-winged monkey-bird (Richard Svensson)

Artistic representation of Britain's bat-winged monkey-bird (Richard Svensson)The following winged wonder only became known to me in mid-October 2007, when Jan Patience, acting editor of the now-defunct British monthly magazine Beyond for which I contributed a major cryptozoology article each issue, brought to my attention a truly extraordinary email that she had just received from a reader. At that time, I was preparing a lead article on lesser-known British mystery beasts for the next issue of the magazine, so the email reached me in time for me to investigate it further and include a full account of the case in my article (Beyond, January 2008), and it is this account of mine that I shall now quote from here.

The email in question had been sent by Jacki Hartley of Tunbridge Wells, Kent, concerning a truly bizarre beast that she claims to have encountered on three totally separate occasions, and which she reported as follows:

"Back in 1969 I was 4 years old and travelling back from my auntie’s house in London. Dad had been driving for about half an hour and we were going through the countryside. I was in the back of the car when I suddenly heard an awful, screeching scream. Mum and dad were in the front chatting and heard nothing. It was twilight and as I looked out of the back window into the trees, I saw what I could only describe as a monster.

"It had bat wings which it unfolded and stretched out before folding back up again, red eyes and a kind of monster monkey face with a parrot's beak and was about 3 feet in height.

"To my 4 year old mind it was terrifying and I had nightmares for weeks. I did not have a name for this thing in my vocabulary and so called it The Bat Winged Monkey Bird as it seemed to be such a weird mixture of animals.

"I saw it again late one night when I was eleven from the back window of the car on our way home from Hastings, I think we were travelling through Robertsbridge and I saw it for the third time last year.

"It was 4.30 in the morning and I was woken by the same horrible screeching sound. Thinking someone was being murdered in the street I jumped out of bed and ran to the window, catching the tail end of it as it flew past. I knew immediately what it was. . .the same horrible monster thing I had seen all those years ago, The Bat Winged Monkey Bird was back.

"I would be very grateful if you or any of your readers could shed any light on or put a name to this thing."

When Jan forwarded Jacki’s email to me, I was naturally extremely intrigued, and replied directly to it, requesting any further information that Jacki could send. In response, I received this second email, together with two accompanying pictures, one of which is Jacki’s own representation of what she saw, and the other a photo of her taken at the age when she experienced her first sighting of the monkey bird:

"My most recent sighting was at 4.30am on 19-10-06 outside my bedroom window, I saw the tail end of it fly past after the awful screeching noise woke me up, my address is in Tunbridge Wells in Kent.

"The time before that I was on my way back from Hastings in Sussex, having just passed through Robertsbridge. While the first time I saw it, we were coming back from London, heading toward Kent and had been travelling for about 20-30 minutes. The creature was sitting in a tree in a field off to my right.

"As for my parents, they just laughed and said I must have fallen asleep and had a nightmare; they weren't interested and simply dismissed it, even though I had nightmares about it coming to get me.

"Although the creature looked solid flesh and blood and made an awful sound, I think it could be paranormal in origin as I have never seen or read about anything that even vaguely resembles it, but if it is real, I would love to know if anyone else has seen it."

Jacki Hartley’s sketch of the bat-winged monkey bird, and a photograph taken of her at the age when she first saw it (Jacki Hartley)

Jacki Hartley’s sketch of the bat-winged monkey bird, and a photograph taken of her at the age when she first saw it (Jacki Hartley)There is no doubt that this grotesque entity as described by Jacki does not correspond even vaguely with any known species of animal native to Britain. And even when venturing beyond the known into the realms of cryptozoology and zooform phenomena, there is little to compare with it, especially from the British Isles. Perhaps the nearest is the Cornish owlman, a weird owl-human composite spied in the vicinity of Mawnan Church Cornwall, mostly during the 1970s, and discussed later here. Remarkably, however, as I discussed in my Beyond article, Jacki’s creature is certainly reminiscent of the Raymondville man-bat(s), for which there has never been a satisfactorily explanation.

Raymondville man-bat (artist unknown, but appeared in Creatures From Elsewhere (ed. Peter Brookesmith, 1984))

Raymondville man-bat (artist unknown, but appeared in Creatures From Elsewhere (ed. Peter Brookesmith, 1984))Consequently, here, for anyone who may be unfamiliar with the latter, is a summary of the Raymondville man-bat case, together with a similar one subsequently reported from LaCrosse, Illinois, as quoted from my book Dr Shuker's Casebook (2008):

"Sitting in his mother-in-law's backyard at Raymondville, Texas, on the evening of 14January 1976, Armando Grimaldo suddenly heard a strange whistling, and a sound that reminded him of flapping bats' wings - a highly pertinent comparison, as it turned out. For just a few seconds later, he was attacked by a man-sized monstrosity with the face of a bat or monkey, a pair of large flaming eyes but no beak, dark, leathery, unfeathered skin, and a pair of huge wings yielding a massive 10-12 ft wingspan (i.e. twice that of any known species of bat). Swooping down at the terrified man, the creature snatched at him with its big claws, but, happily, Grimaldo was able to flee inside before his aerial attacker had inflicted any serious injuries. Nevertheless, his encounter was just one of several on file from this particular region of Texas during early 1976, all documenting sightings of a similar entity.

"Another ‘man-bat’, 6-7-ft tall with a leathery 10-12-ft wingspan, clawed hands and feet, yellow eyes, well-delineated ears, and revealing a huge snarling mouth brimming with teeth, almost flew into the windscreen of a 53-year-old man, Wohali, as he was driving his truck (with his 25-year-old son as passenger) along a road near LaCrosse, Wisconsin, just after 9 pm on the evening of 26 September 2006. The creature then flew back up into the sky and vanished, but the shock of encountering it was such that both men became physically sick. They were convinced that it was a physical, tangible entity. This remarkable case has been documented in detail online by Linda Godfrey at http://www.cnb-scene.com/manbat.html "

LaCrosse man-bat (Richard Svensson)

LaCrosse man-bat (Richard Svensson)Returning to Britain's bat-winged monkey-bird: What is also very strange about Jacki’s report is that she saw the creature in three very different geographical localities and over a considerable period of time, yet without any other eyewitnesses apparently having seen it – or have they? This is where you, gentle readers, come in. Like Jacki, I would love to know if anyone out there has indeed seen this extraordinary creature, or something like it. So if you have, please get in touch with any details that you can provide. I now declare the case of the bat-winged monkey bird well and truly open for online investigation!

Bat-winged monkey-bird as illustrated in colour for the front cover of the January 2008 issue of Beyond, containing my article on lesser-known British mystery beasts (Philippa Foster)

Bat-winged monkey-bird as illustrated in colour for the front cover of the January 2008 issue of Beyond, containing my article on lesser-known British mystery beasts (Philippa Foster)

Published on July 26, 2012 15:21

July 25, 2012

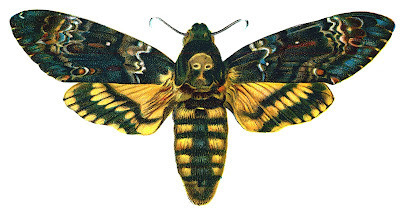

AT THE SIGN OF THE DEATHSHEAD

19th-Century colour engraving of the deathshead hawk moth

19th-Century colour engraving of the deathshead hawk moth"On the 4th of September [1883] one of these insects flew into a house near the Brunswick Brewery, Leeds. There was a sick child in the house at the time, and the mother, terrified at what she thought an evil omen, could not be pacified for some time. The insect was secured and taken to Wardman's, the bird-stuffer's."

John Grassham - The Naturalist's World (January 1884)

Acherontia atropos, the insect referred to above, is nothing if not distinctive in appearance. A rare migrant to the UK, with a wingspan that can exceed 5.5 in and a weight that can fall little short of 0.1 oz, it is incontestably Britain's largest species of moth. Its plum-coloured, wavy-lined forewings and rich golden-yellow hindwings, not to mention its bulky body striped boldly underneath in dark brown and primrose bands, also render it one of this country's most attractive moths. Nevertheless, all of these features are eclipsed by a single, but very singular, additional characteristic - one which instantly identities this species and distinguishes it from all others in Britain, which has woven around it a near-indestructible web of folklore and fear, and which has earned it its extremely sinister-sounding English name.

Pinned specimen of the deathshead hawk moth (Ivo Antušek/www.biolib.cz)

Pinned specimen of the deathshead hawk moth (Ivo Antušek/www.biolib.cz)This feature is a strange marking on top of its thorax's front portion, which, by a grotesque quirk of nature, forms a surprisingly realistic image of a human skull, ghostly white in colour with black, empty eyesockets. Enhancing this macabre image, the thoracic hairs bearing it are erectile, so that when they are raised up and down while the moth is resting, the 'skull' appears to be nodding!

To many superstition-ridden people in the past (and even to some today) this bizarre insignia is considered to be nothing less than the symbol of Death itself, so that A. atropos is commonly referred to as the deathshead, or deathshead hawk moth in full.

Close-up of a pinned deathshead hawk moth, showing its skull simulacrum

Close-up of a pinned deathshead hawk moth, showing its skull simulacrumAs can be imagined, its uncanny skull simulacrum has burdened this perfectly innocent insect with a fearful but wholly undeserved reputation as a harbinger of death, doom, and disaster, and has spawned a rich if ridiculous wealth of fanciful rural beliefs and old wives' tales. For example, on occasions when specimens have been observed in a given region just prior to an outbreak of an epidemic disease, the moths have been automatically blamed, and labelled as the messengers of impending mourning. Indeed, many people blamed the entire French Revolution upon the appearance of an unusual number of deathshead moths shortly before its commencement. Moreover, this insect is said in some localities to be in league with witches and to murmur into their ears the names of persons soon to be visited by Death. In central France, it is widely believed that blindness will result if dust particles falling from the wings of a deathshead in flight happen to land in the eyes of anyone watching it...and so on, and so forth.

Spectacular tattoo of a deathshead hawk moth (Matt Gardiner/Flickr)

Spectacular tattoo of a deathshead hawk moth (Matt Gardiner/Flickr)If these tales were treated lightly, with the humour and contempt that their imaginative but baseless claims deserve, they would constitute nothing more than intriguing yet harmless additions to the annals of modern-day folklore. Tragically, however, for a very long time they have been accepted as truth so wholeheartedly by the credulous and ingenuous that this magnificent moth has been subjected to extensive, barbaric persecution - as revealed graphically by Rev. J.G. Wood's account in his Illustrated Natural History of an all too typical incident that he witnessed during the mid-19th Century:

"I once saw a whole congregation checked while coming out of church, and assembled in a wide and terrified circle around a poor Death's-head Moth that was quietly making its way across the churchyard-walk. No one dared to approach the terrible being, until at last the village blacksmith took heart of grace, and with a long jump, leaped upon the moth, and crushed it beneath his hobnailed feet. I keep the flattened insect in my cabinet, as an example of popular ignorance, and the destructive nature with which such ignorance is always accompanied."

Yet ironically, and despite its eerie thoracic emblem, this much-maligned species was not always so intimately associated in the human mind with death and ill-fortune. Its first English name, apparently given to it in 1773 by nature writer Wilkes, was much more pleasant-sounding - the jasmine hawk moth, after a favoured food-plant of its caterpillar. In 1775, Moses Harris renamed it the bee tyger hawk moth, because of its brown and yellow stripes. 1f only he had been content with this. Sadly, however, in 1778 he changed its name again, this time to the deathshead, which, to its great cost, it has retained ever since. Its scientific name is no less ominous either. Acherontia is derived from Acheron, a river in the underworld of Greek mythology; and Atropos, eldest of the Fates or Moirae, was the black-veiled goddess responsible for cutting every mortal's Thread of Life.

Deathshead hawk moth with wings closed

Deathshead hawk moth with wings closedAcherontia atropos has two close relatives that share its deathhead motif and also have equally doomladen names. Acherontia lachesis (inhabiting the Orient and also the Hawaiian Islands) is named after another of the three Fates, this time Lachesis, who measures out every’s mortal’s Thread of Life, thereby allotting the length of their life.

Acherontia lachesis (Umeshsrinivasan/Wikipedia)

Acherontia lachesis (Umeshsrinivasan/Wikipedia)And Acherontia styx (native to the Middle East and eastern Asia) is named after the river of death encircling the Greek underworld.

Acherontia styx

Acherontia styx

The tenacity of the deathshead’s fallacious notoriety as a winged memento mori has even attracted the attention of the entertainment world. In 1967, Tigon Productions released a UK horror movie entitled 'The Blood Beast Terror', which starred Peter Cushing among others, and concerned a Frankensteinian entomologist of the Victorian era who creates two humans with the ability to transform themselves into giant deathshead moths!

'The Blood Beast Terror' on video (Cobra Video)

'The Blood Beast Terror' on video (Cobra Video)This species is also associated with Salvador Dali’s macabre surrealist film ‘Un Chien Andalou’ (1929). And it appears on the cover of Thomas Harris’s chilling novel The Silence of the Lambs (1988), as well as in the official theatrical release posters for the 1991 film adaptation starring Jodie Foster and Anthony Hopkins.

'The Silence of the Lambs' movie poster (Orion Films)

'The Silence of the Lambs' movie poster (Orion Films)Only a fairly rare spring and summer visitor to Britain, the deathshead A. atropos occurs as a breeding species throughout North Africa and the Middle East and northwards to the Mediterranean. It is resident in parts of southern Europe, and migrates throughout Europe - but cases of breeding have been reported on occasion from Britain, with discoveries of caterpillars in several southern counties. Up to 5 in long, and of robust girth, the impressive-looking deathshead caterpillar varies from several shades of green to lemon, dark brown, or even purple, and is embellished on each flank by seven mauve or azure chevrons, edged decorously with bright yellow or cream. This bold but beautiful colour scheme is topped off with a hazy sprinkling of deep violet or sparkling white dots, and as a final flourish its body's rear end bears a striking curved horn.

Caterpillar of the deathshead hawk moth (Jean Pierre Hamon/Wikipedia)

Caterpillar of the deathshead hawk moth (Jean Pierre Hamon/Wikipedia)Pupation takes place underground, the caterpillar digging its way 2-4 in beneath the soil surface and transforming after about a fortnight into a hard, brown, somewhat shiny chrysalis, surrounded by its cocoon of soil, whose function seems to be to maintain the correct degree of humidity around the chrysalis for its successful metamorphosis.

Pupa of the deathshead hawk moth (Walter Schön/Wikipedia)

Pupa of the deathshead hawk moth (Walter Schön/Wikipedia)By late September or early October, metamorphosis is generally complete and the adult moth emerges. Sometimes two generations occur in the same year; the second emerges during November.

Deathshead hawk moth, 19th-Century German print

Deathshead hawk moth, 19th-Century German printWhereas the caterpillar thrives upon leaves (especially from the potato), the moth is a fruit-eater primarily - but not exclusively, as beekeepers will verify. Unlike the long slender proboscis ('tongue') of so many other hawk moths, perfectly designed for probing flowers in search of nectar, the deathshead's is much shorter and stouter, adapted instead for piercing the tough outer skin of fruit to obtain their succulent juices. However, it is also well-suited for puncturing the honey-containing cells in beehives, which has enabled the deathshead to expand its dietary scope, and explains why this attractive species is frequently discovered inside hives (as are A. lachesis and A. styx). This is exemplified by a startling discovery made in 1901 by the curator of a marine biology station's museum at Rovigno, Istria. As documented by Alfred Bunbury (The Field, 7 December 1901):

"On the second floor of a house next to this zoological museum is a window whose wooden persienne have for a long time been closed. Though the shutters have been shut, the old wood was full of chinks, and Dr Hermes, the curator of the museum, noticed that a swarm of bees had utilised the space between the window and the shutters for a hive. Curious to see the work of the bees, on Oct. 1 he climbed up to the window, and was astonished to find it covered with death's head moths (Acherontia atropos). The moths, which are extremely fond of honey, had either failed to find their way out of the chinks through which they had entered, or, having fed too heavily on the food, had become dazed in the semi-dark light of the window. Dr Hermes and an assistant made their way into the room by another entrance, and removed a lower pane of the window. Quantities of moths were found hanging on the walls and others on the floor. Many that were dead had evidently been killed by the bees, which had got in under their wings, and those that were still alive were badly mutilated. More than one hundred large specimens were taken that day, and though every day five or six more were found in the same way, by Oct. 13, on which day Dr Hermes was summoned to Berlin, he thought that he had freed the last prisoner. But a few days ago a telegram informed him that 154 moths had again fallen a prey to the bees."

Its liking for honey also appears to explain a characteristic of the deathshead that is every bit as uncanny and superficially unnatural as its thoracic skull sign - namely, it has the highly unexpected and singularly unmoth-like ability to squeak!

Click here

to view a photograph of a deathshead hawk moth feeding upon honey inside a honeybee hive (ARKive)

to view a photograph of a deathshead hawk moth feeding upon honey inside a honeybee hive (ARKive)Records of this odd behavioural trait date back at least as far as the 1700s, and its physiological basis has incited much speculation. Some researchers assumed that the squeak was created by friction of the moth's abdomen against its thorax at the junction of these two body portions. Certain others suggested that it occurred if the moth's palps (accessory mouthparts) grated upon its proboscis. It is now known to result from the moth's inhalation of air into its pharynx, causing a stiffened flap (the epipharynx) to vibrate very rapidly.

In their Illustrated Encyclopedia of Beekeeping (1985), Roger Morse and Ted Hooper report that the epipharynx's oscillation yields a pulsed sound of approximately 280 pulses per second for a period of about 80 milliseconds (80 thousandths of one second), followed by a brief pause of 20 milliseconds before the epipharynx is held upwards, enabling the air to be blown out - creating the moth's famous squeak. Lasting a mere 40 milliseconds, it is a very high-pitched sound of about 6 kHz - above the audible range of many humans, though children and acute-eared adults can usually hear it. The moth will perform up to six of these 'squeak-cycles' in as little as one second, but the squeak shortens as the moth tires.

Naturally, there has been much debate about the precise purpose of the deathshead's squeaking. It is certainly a deliberate action, as the moth raises its body when doing so, which enables the sound to be carried to the bees through the air. And as the bees often react by permitting it to enter the hive unmolested (though its tough cuticle is sufficient to withstand occasional stings imparted by any less trusting hive workers, and it is in any case resistant to the venom imparted by such stings), it would seem that its squeaking serves as an effective password. Indeed, some researchers even assert that the moth's squeak is sufficiently similar to the sound made by the hive's queen bee to fool the workers into believing that their queen is instructing them to remain passive. According to this idea, therefore, the deathshead's squeaking is not so much a password as an inspired voice impression!

Deathshead hawk moth, colour engraving from 1840

Deathshead hawk moth, colour engraving from 1840Moreover, as revealed by R.F.A. Moritz and colleagues, this extraordinary moth is even able to mimic the scent of the honey bees’ cutaneous fatty acids, thus rendering it chemically invisible to them, and so further enabling it to move about freely inside their hives (Naturwissenschaften, vol. 78, 1991).

Intriguingly, writer and photographer Des Bartlett has discovered that in Kenya the presence of deathshead moths inside the beehives comes as a great shock to many of the native Kikuyu people, who seem convinced that they must be some form of wonderful super-queen bee (Animals, 30 July 1963). Also, their unexpected squeaking has been looked upon by all too many Westerners as something ominous or even preternatural - no doubt inspiring the earlier-mentioned myth that this species whispers into the ears of witches.

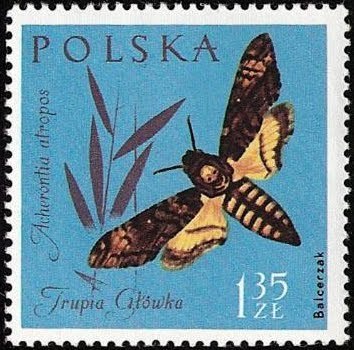

Polish postage stamp portraying the deathshead hawk moth

Polish postage stamp portraying the deathshead hawk mothAll of which brings us back to the subject of superstition, whose anachronistic, irrational utterings of ignorance and fear are still inciting mindless acts of vengeance and violence against this very elegant, showy, and thoroughly harmless insect. Even though we have entered the ultra-scientific 21st Century, there are still people who will not hesitate to kill any deathshead hawk moth that they encounter, atavistically recalling foolish fancies from the centuries of the past.

What can we say to such people? Ironically, the best reply is one that was published almost 150 years ago, but which is still as appropriate today as it was then. To quote from Louis Figuier's The Insect World (1872):

"In spite of its ominous livery, the Atropos does not come from Hades; it is no envoy of death, bringing sadness and mourning. It does not bring us news of another world; it tells us, on the contrary, that Nature can people every hour; that it was her will to console them for their sadness, to grant to the twilight and to the night the same winged wanderers which are at once the delight and ornament of the hours of light and of day. This is the mission of science, to dissipate the thousands of prejudices and dangerous superstitions which mislead ignorant people."

I pray that its mission will succeed, to ensure the survival of the deathshead hawk moth and every other animal currently endangered by the baneful influence of fatuous notions that should have been buried by rationality and compassion a very long time ago.

19th-Century engraving of the deathshead hawk moth

19th-Century engraving of the deathshead hawk mothThis ShukerNature blog post is excerpted from my book Extraordinary Animals Revisited (CFZ Press: Bideford, 2007)

Published on July 25, 2012 17:33

July 19, 2012

THE MISSING MENAGERIE – CREATURES CURSED BY THE STAMP OF EXTINCTION

Following on from my two most recent ShukerNature blog posts (click here and here to view them), here is a third one that once again links a couple of my greatest interests – natural history and philately.

Thanks to my trio of definitive books documenting them ( The Lost Ark , 1993; The New Zoo , 2002; and The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals , 2012), I am more readily associated with zoological arrivals and revivals than I am with extinct and endangered species.

So now, by way of contrast and compensation, this present ShukerNature blog post surveys a varied selection of the most famous and extraordinary residents of Nature’s missing menagerie of vanished creatures. Although they are represented nowadays only by lifeless museum specimens and a few faded photographs, their original beauty and grandeur is recaptured for all time in numerous modern-day works of art – including, as selected from my own personal collection of wildlife-themed postage stamps and presented here, an eyecatching gallery of the philatelic variety.

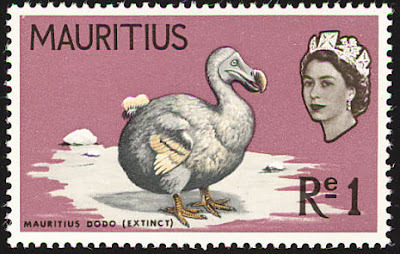

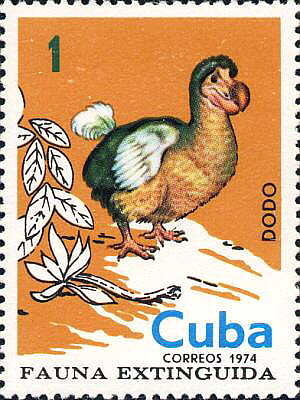

AS DEAD AS THE DODO

By popular zoological convention, an animal is said to have become extinct in historical times if it died out after 1681 AD. However, this is not an arbitrary date. On the contrary, 1681 is the official year of demise for the most famous modern-day extinct species of all – the dodo Raphus cucullatus of Mauritius. ‘As dead as the dodo’ is a popular contemporary expression of extinction or general obsolescence, but the dodo was once very much alive. This giant hook-beaked relative of doves and pigeons had survived untroubled by other species for countless ages on its island home in the Indian Ocean, and, as a result of having no need to flee from anything, had gradually lost the power of flight, becoming ever larger until it was the size of a turkey.

Size, however, was not the only characteristic that the dodo shared with the turkey. Like the latter bird, it was not overly encumbered with brainpower, and its flesh, though not tasty, was at least palatable. These two attributes would spell its inevitable doom if ever it were to encounter humankind – and finally, after Mauritius had enjoyed centuries of secure isolation, this is precisely what happened.

During the early 16th Century, Portuguese sailors began visiting the island, using it as a stop-over location for supplying their ships with food during long oceanic voyages. The dodo, trusting and edible, was a prime target. Later, the Portugese were replaced by the Dutch, who in 1644 established Mauritius as a Dutch colony. By now, the slaughter of dodos had become almost a sport in terms of popularity among the colonists, and its inevitable demise was hastened by persecution from various non-native species introduced here by humans, most notably the rat, dog, cat, monkey, and pig.

By the end of the 17th Century, less than 200 years since the island’s first visitation by Europeans, Mauritius had lost its most iconic inhabitant (and several of its other exotic endemic birds would also be exterminated in the years that followed). The dodo was no more, and the age of modern-day extinction had begun.

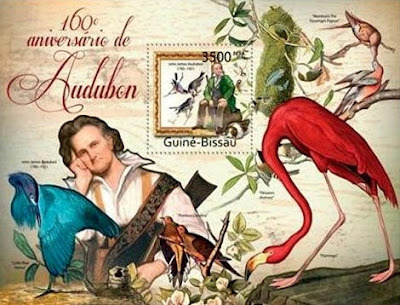

THE PASSING OF THE PASSENGER PIGEON

During the next three centuries, a host of other pigeons, doves, and even a swan-sized dodo relative called the Rodrigues solitaire would be wiped out in remote localities all over the world, but no such extinction would be more surprising – indeed, scarcely believable - than that of the passenger pigeon Ectopistes migratorius. Not only was this handsome species native to the North American continent (as opposed to some far-flung tropical isle only lately reached for the first time by humankind), but it was once incomprehensibly numerous. In fact, as recently as the 19th Century it was deemed to be the most abundant bird that had ever existed anywhere on the planet – its single species accounting for almost 40% of North America’s entire bird population. The following incident demonstrates this well.

One autumn day in 1813, while travelling on a wagon from his Ohio River home to Louisville, Kentucky, around 88 km away, the great American bird painter John James Audubon (who famously painted this now-lost species) witnessed a stupendous flock of passenger pigeons flying overhead in a colossal mass, which so filled the sky above that in his own words: “[the] light of noonday sun was obscured as by an eclipse”. So immense was the flock that when he arrived at Louisville at sunset, it was still passing overhead - an unbroken, seemingly never-ending cloud of life that according to conservative estimates must have contained well over one billion pigeons!

It will come as no surprise, sadly, to learn that the sight of such unimaginable numbers triggered in every sense an insatiable bloodlust among the sporting fraternity of America, and hunters would shoot endlessly at these massive migrations of pigeons, a single bullet often bringing down multiple birds. On and on the slaughter continued, year after year, decade after decade (around a billion pigeons were killed during a single hunt held in 1878 close to Petoskey, Michigan), as it seemed impossible even to contemplate that any depredation, however sustained, would affect the numbers of this innumerable bird – but it did.

Astonishingly, by the end of the 19th Century, the most abundant bird that had ever been had become, in relative terms, a rarity, but even worse was to follow. Less than a quarter of a million pigeons remained, all contained within a single great nesting flock in Ohio - which was almost totally destroyed when a massive hunting party descended upon it, leaving no more than 5000 birds alive.

Too late it was realised that this uniquely prolific species needed enormous numbers for successful reproduction. The sparse quantity that now remained was insufficient, and so the passenger pigeon plummeted headlong into the abyss of extinction. The last known wild specimen was shot in Ohio in 1900, and on 1 September 1914, at the grand old age of 29, the last passenger pigeon in the world, a lone female called Martha Washington, died in her cage at Cincinnati Zoo, and in so doing marked the death of an entire species – one that had once seemed indestructible. The unthinkable had happened – the passenger pigeon was extinct.

Incredibly, only four years after Martha’s death, a second very significant North American species also met its untimely end in the very same zoo, when in 1918 the world’s last Carolina parakeet Conuropsis carolinensis died here. Although nowhere near as numerous as the passenger pigeon, this highly attractive yellow-headed, green-bodied species – the U.S.A.’s only native species of parrot – had once been a common sight through much of the continent’s eastern and southern regions, but it was irresistibly attracted to the fruit of farmers’ orchards and the grain of their fields, and so, like the pigeon, it was doomed.

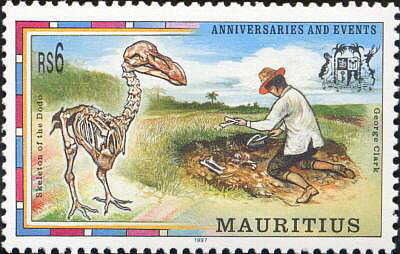

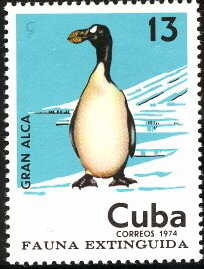

RAIDERS OF THE LOST AUK

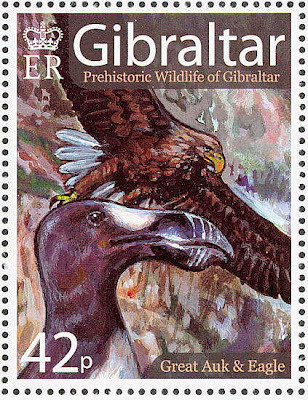

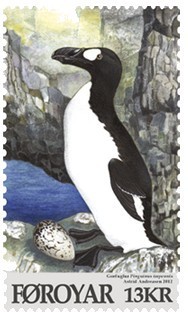

Another famous vanished species is the great auk Pinguinus impennis. This large flightless black-and-white seabird from the northern hemisphere was superficially reminiscent of the southern hemisphere’s familiar penguins, but its link with them does not end there – because the great auk was the original penguin, the latter name having been initially bestowed upon this puffin-allied species. Only later was it applied by those European sailors first penetrating Antarctic waters to the wholly-unrelated birds that they encountered there and which retain it today, long after the original penguin’s extermination.

The great auk once existed in tens of millions, nesting on the rocky coastal areas of islands on both sides of the North Atlantic, but it was in America that it first met its end. Its feathers were prized for use in eider-downs and feather beds, its flesh was tasty and therefore much sought-after by sailing vessels, and collectors coveted its eggs, and so this imposing but helpless bird was massacred in countless numbers. On Funk Island off Newfoundland, for example, its precious nesting grounds were frequently raided and mercilessly desecrated. Thousands of auks were captured alive and cooped together in great enclosures like domestic fowl until it was their time to be slaughtered en masse by being clubbed to death and then thrown into furnaces, enabling their feathers to be more readily removed from their bodies. By the second decade of the 19th Century, the great auk was merely a memory in North America.

In Europe, its major stronghold was the Icelandic coast, but great auks even existed around the more northerly islands of Scotland, most notably St Kilda but also visiting the Orkneys, with one particularly famous Orcadian pair being nicknamed the King and Queen. Sadly, however, they were no safer from hunting here than they had been in the New World. Moreover, it was especially ironic that as this species became rarer, it became ever more persecuted by museum collectors - anxious to add specimens and eggs to their collections before it died out! The last known great auks constituted a pair clubbed to death (and their egg smashed) on the Icelandic island of Eldey on 3 June 1844.

For a few decades thereafter, some quite convincing reports of lone living specimens emerged from various remote far-northern European localities, but none was confirmed. Reports emanating from Norway’s Lofoten Islands during the 1920s and 1930s were duly investigated, only to discover that the birds in question were actually released Antarctic penguins. And a supposed great auk spied in the Orkneys during the 1980s that attracted considerable media attention owed more to a clever publicity campaign for a certain brand of whisky than it did to any unexpected resurrection of the lost auk.

ONE BIRD, TWO BEAKS

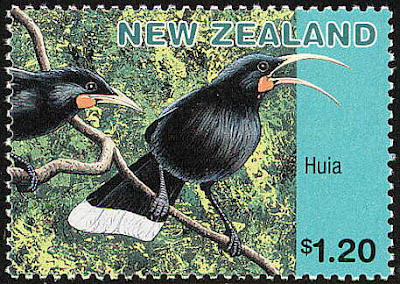

The great auk was not the only species hastened into extinction by the mercenary actions of museum curators. Moving from the North Atlantic to the North Island, of New Zealand, the huia Heteralocha acutirostris was a large predominantly black-plumaged bird whose long broad tail’s tip bore a striking white horizontal band, and its cheeks sported a pair of bright orange wattles. Indeed, it was a member of a small family of birds known as wattlebirds, found only in New Zealand.

What singled the huia out from all other birds, however, was its beak – or, rather, its beaks. Uniquely, the beak of the male huia was totally different in shape from that of the female huia - the former’s was short and straight, the latter’s was long and downward-curving. A pair would work together when seeking the wood-inhabiting grubs on which they fed – the male using his hard, sharp beak to chisel through rotting bark in search of the grubs, and the female then hooking them out with her more delicate, curved beak.

Tragically, however, this unparalleled avian teamwork would soon come to an end – when the species itself died out. Traditionally, the huia’s eyecatching tail feathers had been used in ceremonial Maori head-dresses, but when Europeans arrived their usual unwelcome contingent of rats and cats lost no time in decimating the endemic bird population of New Zealand, and the huia proved to be particularly vulnerable not just to predation by these and other alien species but also to various diseases associated with them. And as with the great auk, once the huia’s numbers crashed, museum curators who realised that they held few specimens of this extraordinary species soon made known their requirement for more, thereby sounding the death knell for this highly endangered bird.

The last known huia was sighted in 1907, and although, as documented in my book Extraordinary Animals Revisited (2007), a few unconfirmed sightings have been made since, including one by Danish zoologist Lars Thomas as recently as 1991, until further notice the huia remains yet another tragic inhabitant of the missing menagerie.

THE SORRY SAGA OF A SEA COW

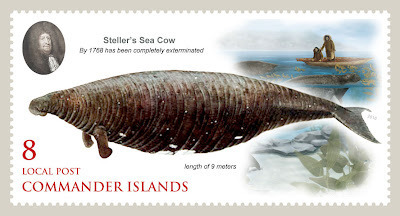

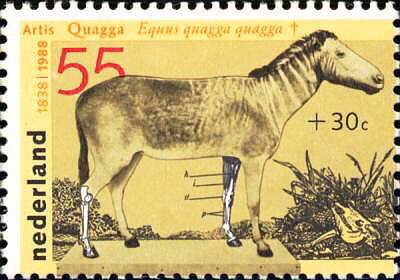

Birds are not the only species to have lost some of their most dramatic members either. Three of the most spectacular mammals to have disappeared since the dodo are Steller’s sea cow Hydrodamalis (=Rhytina) gigas, the quagga Equus burchelli quagga, and the thylacine (Tasmanian wolf) Thylacinus cynocephalus.

Scientifically discovered in 1741 by Russian naturalist Georg Steller, during the Bering Expedition to the icy waters of far-eastern Russia’s North Pacific, and duly named after him, Steller’s sea cow measured approximately 8 m long. This made it by far the largest member of the taxonomic order of mammals known as sirenians, named after the fondly-held belief that sightings by sailors of some of the smaller species, known as manatees and dugongs, had inspired the belief in mermaids or sirens.

When his ship was wrecked on the coast of one of the Bering Sea’s previously-uncharted Commander Islands, Steller had plenty of time to observe in detail these enormous but wholly inoffensive, herbivorous mammals that grazed upon seaweed and gave voice to loud, lugubrious groans. Among the countless discoveries that he made about them was that their flesh was delicious – a fact not lost upon the various expeditions that arrived here in the years to come. So much so, in fact, that by 1768, a mere 27 years after the first one had been seen by Steller, the last of his eponymous sea cows was killed, and the mournful song of this strange mega-mermaid was forever stilled.

THE ZEBRA THAT LOST ITS STRIPES…AND ITS SURVIVAL

Named after the sound of its strange high-pitched whinny, the quagga of South Africa could more aptly be termed a quasi-zebra, for unlike the uniformly striped zebras familiar to one and all today, the quagga, uniquely, was striped only on its face, neck, and anterior forequarters – its flanks and hindquarters were wholly brown and unstriped, and its legs were predominantly white. Although still present in huge herds as late as the 1840s, during the next three decades the quagga was hunted in great numbers by the Boers for its hide and its meat. Its decimation in the wild was completed with the killing of the last known wild specimen in 1878. On account of its unusual appearance, a number of quaggas had been exhibited at various zoos, but in those pre-conservation days no attempt was made to breed this very interesting creature, so when the last captive specimen died at Amsterdam Zoo in 1883, the quagga was gone forever – or was it?

A fascinating captive breeding programme, the Quagga Project, pioneered by natural historian Reinhold Rau, has been underway since the 1990s in South Africa, attempting to recreate the quagga by selective breeding, using specimens of the plains zebra Equus burchelli (of which the quagga was a subspecies) with fewer stripes than normal. Some decidedly quagga-like individuals have already been engendered, but whether they share the original quagga’s genetic make-up rather than merely its outward form has yet to be determined.

THE ONCE AND FUTURE THYLACINE?

Another lost creature that may yet rise again like a veritable phoenix in stripes was – or is, or will be again? – the thylacine or Tasmanian wolf Thylacinus cynocephalus (popularly translated as ‘pouched dog with wolf’s head’, on account of its decidedly canine head and offspring-rearing pouch). Remarkably lupine in superficial external appearance (but wholly unrelated to real wolves and dogs), it was also known as the Tasmanian tiger due to its series of distinctive body and tail stripes. This very impressive creature was the world’s largest carnivorous marsupial (pouched mammal), and although confined in historical times to the island of Tasmania, only a couple of millennia ago it also thrived in mainland Australia, and formerly in New Guinea as well.

Yet despite its spectacular appearance, the thylacine won no fans among European settlers on Tasmania, especially those with farm livestock, whose lambs and sheep proved particularly tempting to this meat-eating mammal – although to be fair, more sheep were killed by introduced domestic dogs there than were ever killed by this island’s pouched counterparts. Nevertheless, in 1888, the Tasmanian government offered a bounty for every thylacine shot, and so, as had happened to all too many other species at other times elsewhere, the annihilation duly began. In 1936, when realisation of the fate awaiting what by now had been scientifically recognised as a priceless product of Antipodean evolution belatedly hit the Tasmanian government, it finally granted the thylacine full protection. The timing was impeccable – impeccably bad, that is, bearing in mind that the world’s last thylacine, a female specimen known somewhat oddly as Benjamin, died at Hobart Zoo just two months later; the last confirmed wild specimen had been shot in 1930.

Having said that, the thylacine has since earned itself the title of the world’s most common extinct animal, because seldom has a year gone by ever since without alleged sightings of specimens emerging from one region or another of Tasmania, and sometimes by very experienced, reliable eyewitnesses such as national park wardens. Consequently, some zoologists remain reluctant to deny categorically that the thylacine still survives, but without any physical, unequivocal evidence to hand, the case for its survival remains unresolved.

Like the quagga, however, plans are afoot to resurrect this fairly recently-extirpated enigma, but this time by means of cloning DNA extracted from various well-preserved museum specimens. Some Australian scientists are confident that the technology to accomplish this Jurassic Park scenario may soon be forthcoming, and that before much longer a living breathing thylacine will once more be a reality.

AND NOT FORGETTING…

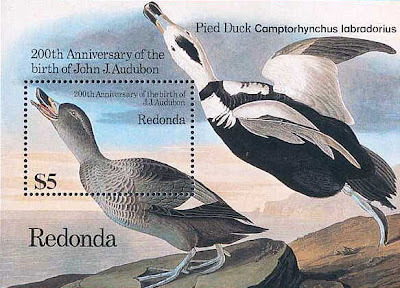

Meanwhile, the extinct species described in this article are just a handful of the hundreds of truly exceptional creatures that have been wiped out since the dodo. Others include the colossal ostrich-like elephant bird of Madagascar Aepyornis maximus (end of the 18th Century), South Africa’s blaauwbok Hippotragus leucophaeus (1799; Africa's first large mammal to become extinct in historical times); the Labrador (pied) duck Camptorhynchus labradorius (1875; black-and-white North American waterfowl only distantly allied to other ducks); and the Falkland Islands fox Dusicyon australis (1876; wholly confined to this South Atlantic island group).

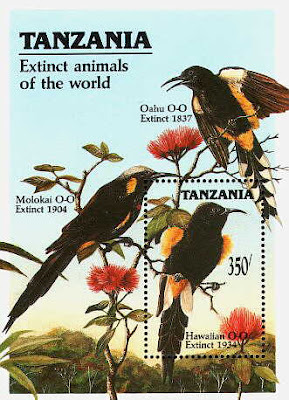

Over a dozen species of finch-related Hawaiian honeycreepers have become extinct in modern times too (including in 1898 the gorgeously-plumed mamo Drepanis pacifica), plus at least three different species of exotic black-and-yellow o-o birds (also Hawaiian, and named after their distinctive call).

Also extinct is the toolach Macropus greyi (1939; an exceptionally beautiful wallaby); the Caribbean monk seal Monachus tropicalis (1952; a specimen was once owned by Fidel Castro); and the all-white Chinese river dolphin or baiji Lipotes vexillifer (declared extinct in 2004, after having first been made known to western science as recently as 1918). And these are just a few from the disturbingly long list of species that have vanished since the dodo's own disappearance just over three centuries ago.

The cloning of a thylacine, or any other of the presently lost species documented here, would certainly be a marvel, but just because extinction might indeed become reversible in the up-and-coming future, we must never forget what destruction our ancestors have wrought upon the living world in the not-so-distant past, and we must ensure that such activity is never repeated anywhere in the present. Who knows – perhaps in the not-too-distant future extinction may no longer be forever, but it should never be at all.

Published on July 19, 2012 17:18

CRYPTO-PHILATELY IN THE FAROES

Iceland is not the only island nation from the far north of Europe that has lately issued a set of postage stamps with a theme bridging cryptozoology and animal mythology – as documented by me in the previous ShukerNature blog post (click here ).

On 30 April 2012, the Faroes issued a set of four very distinctive stamps depicting a quartet of legendary entities endemic to their own land's ancient traditions.

Portrayed on the 6.50 króna stamp is the gryla, which occupies the traditional bogeyman role here, but is also sometimes described as a hairy ogre-like giant or man-beast. During carnival time at Shrovetide in the Faroes, children dress up in festive, imaginative costumes and visit houses to receive sweets and other treats, rather like the 'Trick or Treat' custom at Halloween elsewhere. And according to folklore, the gryla also wanders around at this time, carrying a big sack, inside which he drops any child who has breached the Lent fasting.

The mera or mare pictured on the 11 króna stamp is the original nightmare - a monster that appears at night, often adopting the guise of a beautiful woman according to Faroese belief, and sits upon a sleeping person's body, suppressing their breathing as well as disturbing their sleep, stimulating evil, frightening dreams. Worse still, if it succeeds in inserting its long skeletally-slender fingers into the sleeper's mouth and counts all of their teeth, that person will die.

Even more eerie and grotesque is the entity depicted on the 17 króna stamp, for this is the niðagrísur - the ghost of a newborn or infant child who was murdered without ever having been christened. As a result, the child returns to earth as a niðagrísur, an apparition no bigger than a ball of yarn, in search of its missing name, but it will disappear forever if it is finally given one.

Last but definitely not least is the florutroll or Faroese beach troll, featuring on the 19 króna stamp. Despite its horrifying appearance, covered in seaweed and pebbles, the florutroll serves an important, beneficial function – by scaring children away from the beach, it shields them from the danger of drowning in the sea or being swept away in the raging waves and surf.

Having seen such interesting stamps as these two series from Iceland and the Faroes, it is to be hoped that other nations will consider issuing comparable series focusing upon legendary entities from their own traditions, because they would definitely make fascinating additions not only to philately but also to the artwork and archives of zoomythology and cryptozoology.

Published on July 19, 2012 14:28

ICELAND’S STAMP(S) OF CRYPTOZOOLOGICAL APPROVAL

My book Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Animals on Stamps (CFZ Press: Bideford, 2008) contains a special appendix devoted to stamps depicting creatures of cryptozoology, including such famous examples as the yeti, bigfoot, Nessie, thylacine, Ogopogo, and all manner of sea monsters. On 19 March 2009, moreover, a new set of postage stamps with a cryptozoological and zoomythological theme was issued by Iceland, and the creatures portrayed on this mini-sheet of ten extremely attractive stamps are so unusual and hitherto-obscure that they definitely deserve some attention here.

Perhaps the best-known is the skoffin. This is usually said to be a basilisk-like entity, but is depicted on its stamp as mammalian in nature, and I have documented elsewhere in the past.

Far less familiar, however, are bizarre creatures such as the coast-inhabiting skeljaskaimsli (shell monster), which is a rusty-brown, multi-limbed animal with a tapir-like trunk and pangolin scales; a grave-robbing mystery felid called the urdarkottur or ghoul cat (more details appear in my forthcoming book Cats of Magic, Mythology, and Mystery); and the highly poisonous ofuguggi or reverse-fin trout, whose fins all turn forwards instead of back.

Completing this interesting set are three different varieties of mystery whale - the red-maned hrosshvalur (horse-whale), the raudkembingur or red-crest (both inspired perhaps by oarfishes Regalecus glesne?), and the massive-eared mushveli (mouse-whale); the sheep-molesting, shore-dwelling fjorulalli or beachwalker, portrayed as being very seal-like in its stamp; the huge selamodir (seal mother), which protects normal-sized seals if they are threatened but appears less seal-like in its stamp; and the amphibious saeneyti (sea cattle) that sometimes mingle with true cattle.

A useful new book, Meeting With Monsters, which documents many of these curious Icelandic crypto-beasts, and is available in English and Icelandic, can be ordered from Postphil Iceland. For further details, check out the following link:

https://www.postur.is/cgi-bin/hsrun.exe/Distributed/Postphil/Postphil.htx;start=DetectLanguage?Language=LANG_English

My catalogue of dinosaur and other prehistoric animals on stamps also contains a special appendix devoted to stamps depicting current and former cryptids

My catalogue of dinosaur and other prehistoric animals on stamps also contains a special appendix devoted to stamps depicting current and former cryptids

Published on July 19, 2012 11:21

July 16, 2012

THE TENGU - AN EXCLUSIVE EXCERPT FROM MY FORTHCOMING BOOK, 'CREATURES OF SHADOW AND NIGHT'

Tengu (Andy Paciorek)

Tengu (Andy Paciorek)Earlier this month, a very different book of mine was formally accepted for publication by Coachwhip of Landisville, USA (the company that also published my most recent book in print, The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals, 2012). A most exciting venture and a marked departure from my previous books and writing style, it is entitled Creatures of Shadow and Night, and in it I shall be retelling the folklore and legends of a wide range of sinister and decidedly dark supernatural entities of the night, most of which are relatively or entirely unknown outside their respective homelands. Moreover, each of my verbal portrayals will be accompanied visually by a spectacular full-colour illustration specially prepared by highly-acclaimed graphics artist Andy Paciorek. Now, presenting a tantalising taster of what is to come, here as a ShukerNature exclusive is one of the entries from our book, combining my text with Andy's artwork. We hope that you enjoy it!

THE TENGU

They look like men, until they extend their shadow-pinioned wings and soar skyward. They speak like men, until they turn around and reveal their vulturine faces and hooked raptorial beaks. Mercurial, mischievous, merciless, the Japanese tengus of forest and mountain, and also their Filipino counterparts the alan, can be many things; they will even offer comfort and assistance to humans sometimes - but only sometimes...

The evening had grown dark, but to the Buddhist priest, journeying through the densest, gloomiest portion of the great forest, and enveloped in its grim shroud of shadows, it made little difference. And yet, just up ahead, he was certain that he could discern something glimmering, something that grew steadily brighter as he drew nearer. Suddenly, the thick foliage fell aside, and as he stepped out into a clearing, he gasped in surprise.

Suspended from a sturdy branch of the tall tree standing at the very centre of the clearing was what looked exactly like an enormous birdcage, but a birdcage wrought of gleaming, lustrous gold, which glowed so brightly that the priest was forced to shield his eyes as he gazed at it.

And as he did so, he realised that the cage was not empty. Hanging upside-down inside it was an extraordinary creature – or was it a human? Just like the cage, it too glowed, but with a strange phosphorescence that disturbed yet also delighted the priest, drawing him ever closer until he stood directly before it. Looking through the cage’s bars, his eyes met those of the creature, who seemed to be wrapped in a long feathered cloak, and whose eyes held his in thrall.

Suddenly, the priest felt an uncontrollable desire to open the cage, to become one with its uncanny occupant, but how? He had no key. Still staring into the creature’s unblinking, unfathomable eyes, he felt his hand rise towards the door of the cage. Instinctively, he pulled it back, but then, relenting, he allowed his hand to move forward again, until it rested upon the door’s ornate keyhole. He heard a single faint click, and saw the door begin to swing open, and then...nothing!

The priest’s eyes felt heavy and dim as he struggled to open them, as if they had been bound with a thousand cobwebs of deftly-spun silver. And there, standing before him, stood the tengu. Oh, he recognised it now, and as he looked at it, the tengu’s feathered ‘cloak’ unfurled, transforming into a pair of huge wings. It looked at the priest for a long, silent moment, then threw back its bald avian head, opened its sharp curved beak, and laughed – a terrible, screaming, heart-tearing sound that echoed through the clearing.