Karl Shuker's Blog, page 60

September 30, 2012

MY TWO-HEADED KESTREL – ALL IS REVEALED!

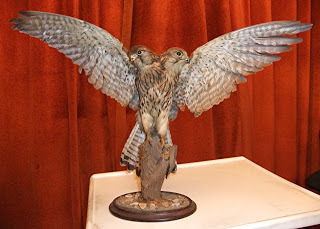

Testament to the skills of an extremely accomplished taxidermist, the two-headed kestrel that is lost no longer (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Testament to the skills of an extremely accomplished taxidermist, the two-headed kestrel that is lost no longer (© Dr Karl Shuker)When I encountered the above taxiderm specimen of a European kestrel Falco tinnunculus with two heads while browsing in a local market on 28 September 2012 (click here to read my ShukerNature blog post concerning it), I was very surprised to SEE it, but not at all surprised BY it. And if that in itself sounds surprising – and possibly even a little confusing! – please allow me to explain, via the following sequel, which in reality is a prequel.

Freak shows and travelling circuses usually display at least one two-headed lamb or pig amidst their panorama of curiosities and caprices, so such entities are far from uncommon. The same can certainly not be said, however, for the erstwhile prize exhibit of a private natural history collection amassed some years ago by a friend of mine whom I shall refer to as Nigel F, from the West Midlands. Among his array of fossils and stuffed animals was a winged wonder unlike no other – dating from Victorian times, it was a perfectly preserved taxiderm kestrel, with two heads.

Silent testimony to the art of the expert taxidermist, it astonished and entranced all who viewed it, until eventually, along with most of his other specimens, Nigel sold it several years ago. Only then did he confess the truth to me – it was a fraud, albeit a truly amazing one. The left head was from another specimen entirely, which the taxidermist had meticulously attached to an already-prepared stuffed kestrel from Victorian times, to create this twin-headed falcon.

Nigel's photograph of his two-headed kestrel (© Nigel F.)

Nigel's photograph of his two-headed kestrel (© Nigel F.)So superb was the artifice, however, as seen in this photograph which he had snapped of his dicephalous marvel some time before selling it (and which, amusingly, depicts the kestrel wearing a gold medallion and chain around its necks!), that even though Nigel knew which head was fake, he had great difficulty in detecting the zone of attachment, artfully concealed beneath its neck feathers. Indeed, to quote the famous words spoken by British television comedian Eric Morecambe concerning his comedy partner Ernie Wise’s alleged wig: “You can’t see the join!”.

Close-up of the kestrel's two heads (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Close-up of the kestrel's two heads (© Dr Karl Shuker)After Nigel sold his two-headed kestrel, however, the whereabouts of this wonderful specimen were no longer known, and there seemed little hope of ever tracing it again. Until 28 September 2012, that is, when I was extremely shocked, but delighted, to discover it for sale on a stall in the very same town where Nigel had sold it all those years previously! In any case, I recognised it instantly from Nigel's photograph (a copy of which he had given to me some time ago) – its pose, tree branch mount, and base were all identical, as can be readily confirmed here by comparing Nigel's photo of it with one of mine, snapped on 28 September.

Nigel's photo (top) and one of mine (bottom) (© Nigel F. and Dr Karl Shuker)

Nigel's photo (top) and one of mine (bottom) (© Nigel F. and Dr Karl Shuker)Clearly, therefore, the kestrel had been sold either directly to the stall holder by whoever had owned it after having purchased it from Nigel, or via one or more intermediary purchasers/owners if such existed. Whatever the explanation, I certainly had no intention of allowing such an astonishing (un)natural history exhibit to disappear into obscurity again – as would almost certainly have happened if someone else had purchased it. So I duly bought it myself.

And once I inform him of its current whereabouts, Nigel will be happy knowing not only that his unique kestrel has resurfaced after all this time but also that it has found a good home again! Result!!

With my two-headed taxiderm kestrel (© Dr Karl Shuker)

With my two-headed taxiderm kestrel (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Published on September 30, 2012 09:40

September 28, 2012

THE TWO-HEADED KESTREL THAT CAME HOME WITH THE GROCERIES!

With my newly-acquired two-headed kestrel (© Dr Karl Shuker)

With my newly-acquired two-headed kestrel (© Dr Karl Shuker)I may be a cryptozoologist and animal anomalist, but even I have to admit that it's not every day I go into town to buy some groceries and return home with a two-headed kestrel – but today was one such day!

Browsing in a local market that contains a number of antique/collectors' stalls, I came upon one stall that I hadn't seen before. And there, directly before me, was this truly extraordinary exhibit – a two-headed taxiderm specimen of the European kestrel Falco tinnunculus.

Two heads are certainly more eyecatching than one! (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Two heads are certainly more eyecatching than one! (© Dr Karl Shuker)To cut an extremely short story even shorter: reader, I purchased it! It is an adult female specimen (judging from its brown heads), is in excellent condition; and although I have seen various dicephalous chickens and ducks in the past, this is certainly the very first bicephalic bird of prey that I have ever encountered.

Did this bird get ahead by having two heads? (© Karl Shuker)

Did this bird get ahead by having two heads? (© Karl Shuker)But is it genuine, a bona fide teratological raptor, or – to use a very apt falconry term - has it been created in order to hoodwink its observers? That is a very good question!

What do you think?

Not quite what I expected when shopping for my groceries! (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Not quite what I expected when shopping for my groceries! (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Published on September 28, 2012 12:44

September 27, 2012

KICKING UP A STINK ABOUT THE INK MONKEY

Reconstruction of Eosimias, the dawn monkey - responsible for the Chinese ink monkey's erroneous resurrection? (Nancy Perkins/Carnegie Museum of Natural History)

Reconstruction of Eosimias, the dawn monkey - responsible for the Chinese ink monkey's erroneous resurrection? (Nancy Perkins/Carnegie Museum of Natural History)The Vu Quang ox or saola Pseudoryx nghetinhensis, the giant muntjac Muntiacus (=Megamuntiacus) vuquangensis, and the Panay cloud rat Crateromys heaneyi are just a few of the remarkable number of major new mammals that were described from Asia during the 1990s. Yet none has a more controversial pedigree than the very mysterious mini-mammal that was supposedly rediscovered during the mid-1990s in southeastern China.

The tangled tale of the Chinese ink monkey (also called the pen monkey) hit the media headlines on 22 April 1996 when the People's Daily newspaper published an account based upon information supplied to it by the official New China News Agency (Xinhua). According to these sources, this amazing little animal was no larger than a mouse, weighed only 7 oz, and had recently been discovered alive in the Wuyi Mountains of Fujian Province after having been dismissed as extinct by Chinese scientists for several centuries. Strangely, however, no additional details concerning its resurrection - precisely when, by whom, the number of specimens recorded, whether any had been photographed or collected, etc - were given. Nor was its zoological species identified, or any extensive morphological description supplied.

In contrast, details of its 'pre-extinction' history were as profuse as they were perplexing. Supposedly known in China since at least 2000 BC, the ink monkey was so-named because it was the traditional pet of scholars and scribes - and for good reason. Despite its tiny size, the ink monkey was very highly intelligent - so much so that a writer would frequently train one to prepare his ink for him, turn the pages of a manuscript that he was working on or reading, and pass brushes to him as required. Ever the practical, diligent pet, a writer's ink monkey would even sleep in his master's desk drawer or brush pot. Zhu Xi (AD 1130-1200), a famous Neo-Confucian philosopher, allegedly owned one of these obliging little helpers, yet sometime later the species seemed to have become extinct (an unexpected occurrence for so useful a beast, I would have thought) until its belated reappearance during the mid-1990s.

Those, then, were the 'facts' of a very odd cryptozoological case - but they served only to enhance rather than to elucidate the mysteries encompassing this extraordinary animal.

An Eosimias-inspired Chinese ink monkey, as visualised by artist Monkeyink (click

here

to view a selection of products bearing Monkeyink's wonderful artwork)

An Eosimias-inspired Chinese ink monkey, as visualised by artist Monkeyink (click

here

to view a selection of products bearing Monkeyink's wonderful artwork)First and foremost of these was its identity - what exactly was - or is - the ink monkey? The world's second smallest known living primate is itself a fairly recent revival - the western rufous mouse lemur Microcebus myoxinus of Madagascar, measuring a mere 7.75 in long, and weighing just over 1 oz. This tiny species was first described by science back in 1852, but was subsequently believed to have died out until its rediscovery in 1993. Could it be that the ink monkey report was a confused retelling of this lemur's reappearance? In view of the historical background details presented above, this seemed highly unlikely. (In 2000, an even smaller species, Madame Berthe's mouse lemur M. berthae, was formally named and described, and now holds the record of the world's smallest living primate species.)

Western rufous mouse lemur (Wikipedia)

Western rufous mouse lemur (Wikipedia)Turning from lemurs to monkeys, however, shed little light on the problem either. The world's smallest formally recognised species of monkey is the pygmy marmoset Cebuella pygmaea of the Upper Amazon Basin, with a total length of around 10 in. Yet mainstream zoology knows of no species of Chinese monkey as small as a mouse - nor, as far as I am aware, are there any reports of such a beast in the cryptozoological literature either. Nevertheless, the ink monkey is not entirely unknown to Westerners.

Two baby pygmy marmosets (FactZoo.com)

Two baby pygmy marmosets (FactZoo.com)I am greatly indebted to Steve Moore, a renowned specialist in Oriental Fortean-related literature, for bringing the following excerpt to my attention, which appeared in a book of Chinese lore by E.D. Edwards entitled The Dragon Book (1938), p. 149:

"THE INK-MONKEY

"This creature is common in the northern regions and is about four or five inches long; it is endowed with an unusual instinct; its eyes are like cornelian stones, and its hair is jet black, sleek and flexible, as soft as a pillow. It is very fond of eating thick Chinese ink, and whenever people write, it sits with folded hands and crossed legs, waiting till the writing is finished, when it drinks up the remainder of the ink; which done, it squats down as before, and does not frisk about unnecessarily."

Edwards obtained these engrossing snippets from a Chinese author called Wang Ta-Hai, writing in 1791, whose work was translated into English as a two-volume tome entitled The Chinese Miscellany (1845, 1849).

Whereas Edwards's description may initially conjure forth bizarre images of a red-eyed pixie with an insatiable ink lust, it also calls to mind certain real-life creatures, such as the bushbabies or galagos, and, especially, those real-life goblins of the golden eyes - the tarsiers. These tiny arboreal primates weigh only a few ounces and have brown or grey bodies measuring no more than 6 in. Tarsiers are distantly related to bushbabies and lemurs, and are characterised by their large ears, enormous orb-like eyes, very long tarsal bones, flattened sucker-like discs at the tips of their fingers and toes, and a long thin tail.

Phillipine tarsier (Wikipedia)

Phillipine tarsier (Wikipedia)Traditionally constituting a trio of species indigenous to Borneo, Sumatra, the Philippines, and Sulawesi, in recent times several additional species have been recognised from Sulawesi and its offshore islets - including the pygmy tarsier Tarsius pumilus in 1987, Diana's tarsier T. dianae in 1988, and the Sangihe tarsier T. sangirensis in January 1996. Could the ink monkey be yet another lately-revealed tarsier? During a radio interview broadcast on 24 April 1996 concerning the ink monkey in which he expressed the view that it may possibly be a tarsier, veteran British wildlife broadcaster Sir David Attenborough noted that tarsiers did exist in southern China a long time ago, and that such secretive, nocturnal creatures as these might conceivably have succeeded in surviving in small numbers amid this region's thick forests right up to the present day while remaining undetected by science.

Conversely, during the same interview, Cyril Rosen of the International Primate Protection League favoured the slow loris Nycticebus coucang as a plausible contender, whose southeast Asian distribution range may indeed extend into southeastern China.

Slow loris depicted on a postage stamp issued by Vietnam in 1984

Slow loris depicted on a postage stamp issued by Vietnam in 1984Yet even if one or other of these identities were correct, how could such an animal be trained to prepare ink? Back in the centuries when the ink monkey allegedly assisted writers in this manner, ink was normally compounded from a precise array of precious materials, such as sandalwood, musk, gold, pearls, and rare herbs or bark, yielding a stick of ink. Consequently, it was suggested in Western media accounts that perhaps the ink monkey was trained to grind the stick in an inkstone with pure water until the correct shade was obtained. Nevertheless, such valuable constituents as those listed above are hardly the types of material that most people would entrust to a monkey (or tarsier) for handling.

Moreover, aside from Edwards's curious contribution that the ink monkey not only prepares but also consumes ink, there were no details as to its dietary preferences. Tarsiers, unlike most other primates, are entirely carnivorous. So if the ink monkey is indeed a tarsier, what might we expect its favourite food to be? When a colleague's enquiries at the news agency in Xinhua that released the original press information concerning the ink monkey revealed that the agency had no record of where they had actually received their own details(!), I began to suspect that fillet of red herring - or perhaps even a tasty canard? - may well prove to be the answer.

In other words, it seemed likely that the whole episode of the Chinese ink monkey was either a bizarre hoax from start to finish, or, more probably, simply the benighted product of confused reporting. Quite possibly, for instance, a Chinese media report had somehow been erroneously translated by Western journalists so that its true subject, one of China's lesser-known non-existent beasts of fable and folklore, had falsely 'become' a real-life animal that had been rediscovered after several centuries of supposed extinction.

And in case this hypothesis seems too implausible, I recommend readers to peruse an entire chapter devoted to several comparable cases of monstrous misidentification exposed in all their glorious folly, within one of my earlier books, From Flying Toads to Snakes With Wings (1997).

Nevertheless, it would be reassuring if the original source of such confusion could be traced. For a time, I was unable to do this, but eventually, when resurveying zoological reports from April 1996, I came upon a short piece that had not attracted anywhere near as much attention as the Chinese ink monkey story, and which I had not seen before, yet which assuredly presented me with the missing piece of this extraordinary cryptozoological jigsaw.

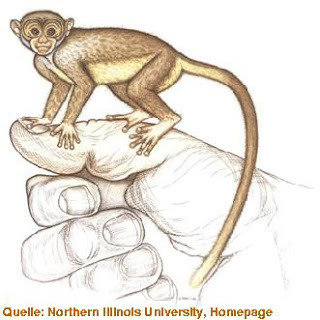

Life-size reconstruction of Eosimias centennicus (Northern Illinois University)

Life-size reconstruction of Eosimias centennicus (Northern Illinois University)The report was a short but succinct item published by London's Times newspaper on 5 April 1996 (3 weeks before the ink monkey reports). It recorded the discovery in China's Yellow River basin of fossil jaw remains from a mouse-sized primate dubbed Eosimias centennicus, the dawn monkey, which had lived 40-43 million years ago, and weighed a mere 3-4 oz. Needless to say, this description tantalisingly echoes the sparse details available in the subsequent reports dealing with the Chinese ink monkey.

Consequently, the most reasonable explanation for this entire episode is as follows. Somewhere in the early portion of the chain of journalistic communication ultimately giving rise to the ink monkey media stories in the West, details of the discovery of the Eosimias fossils, documented correctly in The Times, became distorted elsewhere, and were mistakenly combined with the traditional Chinese ink monkey folklore - until the tragi-comical result was the rediscovery of a creature that had never existed.

In other words, a scenario featuring, perhaps fittingly, a classic case of Chinese whispers!

Life-sized model of Eosimias centennicus (Robert Clark/National Geographic)

Life-sized model of Eosimias centennicus (Robert Clark/National Geographic)NB - Four Eosimias species are currently recognised nowadays, with remains of a fifth presently awaiting formal naming.

This ShukerNature blog post began life as a 'Menagerie of Mystery' article of mine published by Strange Magazine in 1996, which I later expanded and updated to yield a chapter in my book The Beasts That Hide From Man: Seeking the World's Last Undiscovered Animals (Paraview: New York, 2003), but it has been extensively plagiarised online since then (like so much of my other writings and researches!). Consequently, I decided it was high time my original, authentic version was made available on the Net, so here it is!

Published on September 27, 2012 18:20

September 24, 2012

A SNAKE WITH A HEAD AT EACH END? - THE AMPHISBAENA AWAKES!

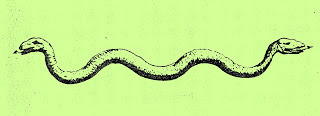

Amphisbaena portrayed in a mediaeval bestiary

Amphisbaena portrayed in a mediaeval bestiaryAs documented in a previous ShukerNature blog article (click here to read it), freak two-headed (aka bicephalic or dicephalous) snakes, although rare, are by no means unknown. In some examples, the two heads each emerge directly from the body; in certain others, they each possess their own neck that emerges independently from the body; and in a few instances, one head emerges directly from the body whereas the other emerges via a neck. However, what they all have in common is that both heads occur at the same end of the body, the front (anterior) end, with a tail at the posterior end.

This is why the freak specimen of rough earth snake Virginia striatula (a small, non-venomous, arthropod-eating colubrid) discovered three weeks ago by workmen at the home of the Logan family in South Carolina (and cared for since then by the grandfather of the two Logan children, Preston and Savanna) is so very special – because this remarkable little snake's two heads are located at opposite ends of its body! Instead of possessing a tail, it sports a head at the posterior end of its body, plus a head at the anterior end as normal. This extraordinary teratological condition is known as amphicephaly, and, as will be seen a little later here, is so rare that the Logans' new pet may be the only modern-day example ever confirmed – always assuming, however, that it really is amphicephalous.

The Logan family's putative amphicephalous snake (© Foxcarolina.com)

The Logan family's putative amphicephalous snake (© Foxcarolina.com)On 24 September 2012, America's Fox News released a short video of the snake as part of an interview with the Logan family concerning it (click here to view it), and their report claims that the snake definitely has two heads, each with its own pair of eyes, a mouth, and a tongue, but that one head is more dominant than the other, though each head will take control of the body's movements. Having watched the video closely, I have been unable to spot a tongue emerging from the mouth of the subordinate head, in contrast to the constant tongue-flicking behaviour of the dominant head. However, the subordinate head does appear to possess a pair of eyes. So, could the Logans' snake truly be amphicephalous, and, if so, are there any verified precedents? Or is there some other, more orthodox, conservative explanation?

A normal rough earth snake (Jscottkelley/Wikipedia)

A normal rough earth snake (Jscottkelley/Wikipedia)Quite a number of snake – and also lizard – species have a tail that closely resemble their head both in shape and in colouration, and often move their tail in a manner that deftly mimics the head's movements. The purpose of this deceptive duplication is to confuse predators so that if they do attack, they attack the least important body end (the tail, which can often be regenerated later), rather than the head. This condition thereby constitutes 'pseudo-amphicephaly'. Such species include southeast Asia's red-tailed pipe snake Cylindrophis ruffus, the Indian sand boa Eryx johnii, the Australian stump-tailed lizard Trachydosaurus rugosus (=Tiliqua rugosa), and in particular the so-called worm-lizards or amphisbaenians.

Two Iberian amphisbaenians or worm-lizards Blanus cinereus (Richard Avery/Wikipedia)

Two Iberian amphisbaenians or worm-lizards Blanus cinereus (Richard Avery/Wikipedia)In contrast, genuine amphicephalous individuals are rarely if ever recorded (until now?). Probably the best modern-day review of such animals was a paper by Prof. Bert Cunningham of Duke University, published by Scientific Monthly in 1933. His paper considered a selection of reptilian examples of potentially genuine amphicephali. However, these were mostly collected from medieval bestiaries and other antiquarian writings, which tend not to be the most reliable or scientifically accurate of sources. And certainly, the vast majority of those examples seemed to be either misidentifications of pseudo-amphicephalous species or deliberate fakes. Two, conversely, may well have been the genuine article.

One of these was a supposed amphicephalous snake specimen catalogued in 1679 within the famous natural history collection of the eminent Dutch biologist Jan Swammerdam (1637-1680). Moreover, it was personally observed a year later by another prominent scientist, Dutch physician-entomologist Steven Blankaart (1650-1704) – all of which lends a degree of veracity to this specimen's authenticity.

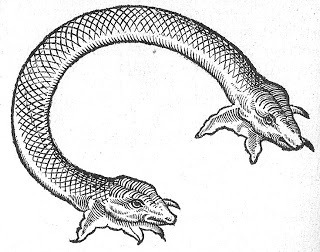

Jan Swammerdam's reputed amphicephalous snake, drawn by Blankaart and published in 1680

Jan Swammerdam's reputed amphicephalous snake, drawn by Blankaart and published in 1680The second example was a lizard with a head at each end, represented by an illustration in Historia Serpentum et Draconum by Italian naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522-1605), published posthumously in 1640. Aldrovandi is said to have made his drawing from the living animal, which, if true, increases the likelihood of this specimen having been truly amphicephalous.

Aldrovandi's drawing of an alleged amphicephalous lizard

Aldrovandi's drawing of an alleged amphicephalous lizardAlso worth recording here is a pair of conjoined (i.e. 'Siamese') terrapin twins reported in 1928 by C.H. Townsend. For whereas most conjoined terrapins (a fair number have been documented down through the years) are linked to one another laterally (i.e. side by side) or ventrally (belly to belly), these two individuals were joined to each other posteriorly (rear-to-rear). This yielded a double animal that approached the genuine amphicephalous state. Other, more recent examples of this semi-amphicephalous version of conjoined terrapins are also known.

A semi-amphicephalous example of conjoined terrapins (Matt Rourke)

A semi-amphicephalous example of conjoined terrapins (Matt Rourke)Returning to the medieval bestiary sources consulted by Prof. Cunningham, these would certainly have referred to the most famous amphicephalous beast of all, albeit one that is entirely mythical – the amphisbaena. Generally categorised as a serpent dragon, i.e. limbless like a snake but dragon-headed, the amphisbaena had a head at each end of its body, and could therefore move in either direction – sometimes accomplished by grasping one head in the jaws of the other so that its body became a hoop that could roll rapidly over the ground.

An amphisbaena was almost impossible to approach unseen, because only one head slept at a time, the other one staying awake, particularly when this creature was laying eggs. And if an amphisbaena were cut in half, the two segments would promptly rejoin.

According to Greek mythology, the amphisbaena was spontaneously generated from drops of blood falling onto the desert sands from the severed head of the gorgon Medusa when her slayer, the hero Perseus, flew over Libya with it on his journey back home to the Greek island of Seriphos. Although the amphisbaena's principal diet was ants, it was claimed by some writers to be extremely venomous, and one was blamed for the subsequent death of Mopsus, a seer who was also one of the famed Argonauts that accompanied Jason on his quest for the Golden Fleece.

Amphisbaena reported from Mexico, depicted in Johannes Faber's Thesaurus (1651)

Amphisbaena reported from Mexico, depicted in Johannes Faber's Thesaurus (1651)Yet despite its deadly nature, the dual-headed amphisbaena was often cited by early scholars for its medicinal qualities. Sometimes a living specimen was needed, otherwise the skin of one was sufficient. Among the assorted ailments that it reputedly eased were arthritis, chilblains, and the common cold, as well as assuring a safe pregnancy, and keeping warm during the winter if working outside. Eating the meat of an amphisbaena could even attract lovers, and killing one during a full moon would imbue its slayer with great power provided that he was pure of heart and mind.

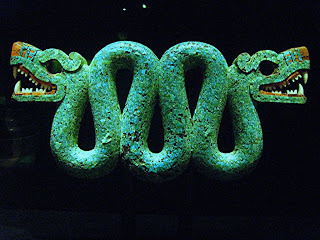

Amphisbaenas often featured in Mesoamerican and Inca cultures too, frequently depicted with a vertically undulating body, and symbolised eternity. Some of the most spectacular renditions are composed of turquoise mosaic, a stone believed by the Aztecs to emit smoke, and therefore a very fitting mineral for portraying a dragon, especially in versions representing Xiuhcoatl - known variously as the fire serpent or the turquoise serpent. In these New World versions, one head was sometimes much larger than the other, rather than always being identical as in the original Old World amphisbaena.

The turquoise serpent, sculpted from turquoise and pine resin, 15th-16th-Century, Mexico, housed at the British Museum (Sarah Branch/Wikipedia)

The turquoise serpent, sculpted from turquoise and pine resin, 15th-16th-Century, Mexico, housed at the British Museum (Sarah Branch/Wikipedia)In Chile, the oral traditions of the Elqui villagers tell of a 6-ft-long spotted amphisbaena known as the culebrón. During the day, it crawled very slowly upon the ground, but at night it took flight, because, uniquely among amphisbaenas, this version sported a pair of wings

Perhaps the strangest South American amphisbaena, however, was the manora, whose basic form resembled a giant earthworm. Its head and tail ends were indistinguishable from one another, but its body was covered all over with sharp feather-like quills.

Today, the legendary amphisbaena gives its name to a group of real-life reptiles, the amphisbaenians, which are also known as worm-lizards. Their heads are so similar in appearance to their tails that it can be difficult to distinguish which end is which, thus recalling the two-headed amphisbaena of legend.

19th-Century engraving of a spotted amphisbaenian Amphisbaena fuliginosa from Trinidad

19th-Century engraving of a spotted amphisbaenian Amphisbaena fuliginosa from TrinidadHaving said that, the legendary amphisbaena underwent a profound transformation during medieval times. It gained not only a pair of legs but also a pair of wings, as well as a well-delineated tail – at the end of which was its second head. It also acquired the literally petrifying, gorgonesque ability to turn anyone who looked at it to stone with just a single glance. This advanced version of the amphisbaena is known as the amphisien, and commonly occurs in heraldry.

The amphisien version of the amphisbaena, as depicted in the Aberdeen Bestiary (Aberdeen University Library MS 24)

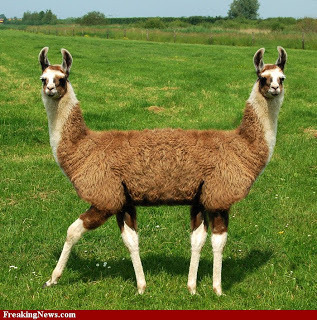

The amphisien version of the amphisbaena, as depicted in the Aberdeen Bestiary (Aberdeen University Library MS 24)In modern-day fiction, the most famous amphicephalous creature must surely be the pushmi-pullyu, featuring in Hugh Lofting's beloved series of 'Doctor Dolittle' novels for children (click here for a ShukerNature post devoted to this twin-headed wonder beast). In reality, however, no such animal could exist, because as mammals have a head at one end of their body and an anus at the other, an amphicephalous mammal would lack an anus and therefore be unable to defaecate.

A marvellous Photoshopped pushmi-pullyu (FreakingNews.com)

A marvellous Photoshopped pushmi-pullyu (FreakingNews.com)Surely, therefore, this same argument negates the plausibility of the Logan family's alleged amphicephalous snake too? Actually, no – because unlike mammals, the external excretory orifice in snakes (which is actually a cloaca, as it also functions as a genital orifice) is situated not at the end of its body but about a quarter of the way up from the end (which means that the remaining quarter of the snake's body is actually its tail). Theoretically, therefore, an amphicephalous snake could actually have two cloacae, each positioned a quarter of the way up from the opposite head. As for how an amphicephalous snake could develop in the first place, if an early snake embryo split laterally from the head down almost to the end of the tail, so that the two resulting snakes remained attached to one another only by a common, shared portion of the developing tail section, this might indeed yield such a specimen.

No mention of cloacal presence has been reported for the Logans' snake, but it will be very interesting to see whether further reports, containing additional details or confirmation of its dual anatomy, emerge in due course. After all, it's not every day that a veritable resurrected beast of classical mythology hits the news headlines around the world.

The amphisbaena awakes? Let's wait and see...so watch this space!

An ornament portraying the amphisbaena of classical mythology (Dr Karl Shuker)

An ornament portraying the amphisbaena of classical mythology (Dr Karl Shuker)

Published on September 24, 2012 15:47

September 22, 2012

THE STUFFED DODO THAT WAS A NO-NO!

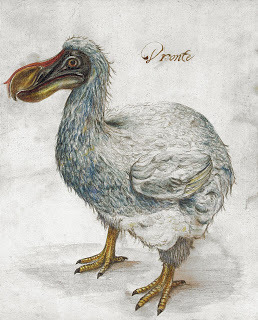

A recently-discovered 17th-Century Dutch illustration of the dodo

A recently-discovered 17th-Century Dutch illustration of the dodo One of the most (in)famous stories in zoological museum history is how the world’s only stuffed specimen of the dodo Raphus cucullatus - Mauritius's best-known species of extinct bird - was allegedly discarded and burnt on 8 January 1755 on the orders of a committee of trustees at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum because they considered it looked tatty, and how an assistant had the foresight to rescue its head and one of its feet before the flames reached them. As will be revealed later however, this story is spurious in the extreme. What is true, conversely, is that those precious relics were later transferred to the University Museum of Zoology, where they are now among its most prized specimens.

Plaster casts of the preserved Oxford dodo head and a now-lost preserved dodo foot formerly held at Brighton's Booth Museum of Natural History (Ed Schipul/Wikipedia) Being well aware of this, I was nothing if not startled by an email published on 16 March 2008 in the Sunday Mirror newspaper’s ‘Treasure Hunters’ column, compiled by TV antiques and collectables expert James Breese. The email in question was from a Ray Holmes (no address or location details given), in which he asked Breese to tell him the likely worth of what he described as a stuffed dodo in near-perfect condition, owned by him and preserved inside a domed glass case, which had originally been acquired by an ancestor of his sometime during the mid-1600s.

Plaster casts of the preserved Oxford dodo head and a now-lost preserved dodo foot formerly held at Brighton's Booth Museum of Natural History (Ed Schipul/Wikipedia) Being well aware of this, I was nothing if not startled by an email published on 16 March 2008 in the Sunday Mirror newspaper’s ‘Treasure Hunters’ column, compiled by TV antiques and collectables expert James Breese. The email in question was from a Ray Holmes (no address or location details given), in which he asked Breese to tell him the likely worth of what he described as a stuffed dodo in near-perfect condition, owned by him and preserved inside a domed glass case, which had originally been acquired by an ancestor of his sometime during the mid-1600s.In reply, Breese rightly pointed out that if a genuine stuffed dodo did indeed exist anywhere, it would be priceless both in value and in scientific importance. However, he also revealed that fake dodos have been produced by taxidermists (notably Rowland Ward of London), created by using feathers and tissues from other birds, and opined that this is very probably the explanation for Holmes’s dodo.

Nevertheless, the fact that the latter specimen apparently dated from the mid-1600s – a period when the dodo was still alive (this species’ official extinction date is traditionally given as 1681, though recently a slightly later date has also been proposed) – was significant enough in Breese’s view for him to suggest that Holmes should take his dodo to a museum for a closer inspection.

Facsimile taxiderm specimens of the Reunion white dodo Raphus solitarius (a species now known never to have existed!) and the Mauritius dodo at Tring Natural History Museum (Dr Karl Shuker) Although I strongly suspected it was a fake, I certainly agreed with Breese's suggestion that it should be professionally examined. After all, albeit highly unlikely, if by any chance it actually was the real thing, a complete, near-perfect, genuine stuffed dodo would be one of the greatest zoological finds of modern times – almost as amazing as discovering a living, breathing dodo! Consequently, after documenting this intriguing episode in one of my Alien Zoo columns for Fortean Times a few months after the Sunday Mirror's original report, I requested anyone with additional information concerning this or other stuffed dodos to contact me.

Facsimile taxiderm specimens of the Reunion white dodo Raphus solitarius (a species now known never to have existed!) and the Mauritius dodo at Tring Natural History Museum (Dr Karl Shuker) Although I strongly suspected it was a fake, I certainly agreed with Breese's suggestion that it should be professionally examined. After all, albeit highly unlikely, if by any chance it actually was the real thing, a complete, near-perfect, genuine stuffed dodo would be one of the greatest zoological finds of modern times – almost as amazing as discovering a living, breathing dodo! Consequently, after documenting this intriguing episode in one of my Alien Zoo columns for Fortean Times a few months after the Sunday Mirror's original report, I requested anyone with additional information concerning this or other stuffed dodos to contact me.As a result, I received several communications from dodo author-historian Anthony Cheke, who not only supported my suggestion that it was a fake but also provided further insights into this intriguing subject, and which he has kindly permitted me to document here.

Flemish artist Roelandt Savery's famous dodo painting from 1626 (which also features two mystery macaws – click HERE for details) Most significantly, the methods of preservation available during the 17th Century were so poor that there are no stuffed birds from that time period still in existence anywhere – they have all long since rotted away or been eaten by insects. As stated by Anthony to me:

Flemish artist Roelandt Savery's famous dodo painting from 1626 (which also features two mystery macaws – click HERE for details) Most significantly, the methods of preservation available during the 17th Century were so poor that there are no stuffed birds from that time period still in existence anywhere – they have all long since rotted away or been eaten by insects. As stated by Anthony to me:"In the 17thC (i.e. 1600s) skins were just cleaned and dried (rarely stuffed) without preservative - or any they used was short-lived. So the specimens simply over time succumbed to moths and mites, only the hard bits generally surviving (i.e. beaks, bones, antlers, carapaces etc.). Very few survived as far as the mid-18thC, the decaying dodo [at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum] was a late survivor, and the Ashmolean dumped ALL their remaining 17thC specimens at the same time as the dodo [1755]... - [museums/cabinets of curiosities] didn't even invent pickling specimens in alcohol until the mid-1660s! As far as I know there are NO 17thC specimens intact anywhere, and very few that pre-date the mid-1700s - most of the huge (former) royal collection in Paris (including almost all of Brisson and Buffon's types) was destroyed around 1800 when they tried to save it by fumigation, but the sulphur fumes damaged the specimens more than the bugs they were trying to kill!...The stuffed dodo in Prague was at some point reduced to just a skull and some bones that still survive. Two more in Oxford's Anatomy School disappeared around 1750."

Further details can be found in Anthony’s authoritative book Lost Land of the Dodo: The Ecological History of Mauritius, Reunion and Rodrigues (2007), co-authored by Dr Julian Hume.

In short, as suspected from the beginning, the dodo owned by Ray Holmes is undoubtedly a later, facsimile dodo, constructed from the skin and feathers of other, non-dodo species of bird.

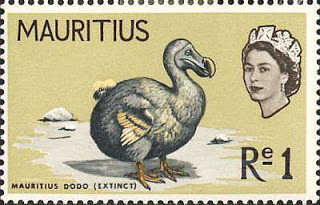

Dodo portrayed on a postage stamp issued by Mauritius in 1965 (Dr Karl Shuker) Anthony also provided some little-known but interesting mitigating evidence in relation to what has traditionally been portrayed as a rash act by the Ashmolean Museum's trustees in discarding its dodo:

Dodo portrayed on a postage stamp issued by Mauritius in 1965 (Dr Karl Shuker) Anthony also provided some little-known but interesting mitigating evidence in relation to what has traditionally been portrayed as a rash act by the Ashmolean Museum's trustees in discarding its dodo:"On the Oxford specimen, you have to remember that in 1755 they didn't know they had the only specimen, and equally didn't know it was extinct (that wasn't first mooted until 1784 - in France)."

Moreover, even the oft-reported account of how it was wilfully destroyed seems now to have been at the very least an exaggeration or distortion of the true facts, and at most a downright lie. Here is what Dr Julian Hume and two co-workers wrote on this delicate subject in a 2006 dodo paper published in the Bulletin of the British Ornithologists Club:

"There was a long-held belief that this, by then unique, stuffed Dodo was thrown onto a fire in 1755, and that only the head and a foot were rescued from the flames (e.g., Strictland & Melville 1848, Fuller 2002). In fact, its removal from exhibition was a curatorial decision made to preserve what was left of the by then highly degraded specimen (Ovenell 1992). The salvaged remains included the skin of the head, some feathers and a foot."

The final nail in this now-clearly-suspect account's coffin was provided by another dodo researcher, Jolyon Parish, who disclosed the following information in an email to me of 2 December 2010:

"Regarding the Oxford dodo, the head and left foot were saved by the same person as removed it from display (George Huddesford). There is no evidence that the specimen was burned and it is only recorded that they were removed from display, as decreed by Ashmole’s statute, following a meeting of the Vice-Chancellor (Huddesford, who was also Keeper of the Museum) and the Visitors in January 1755."

And so another favourite story from the history of zoology proves to have been just that – a fable that had tenaciously persisted into the present day, unlike, tragically, its long-demised subject, the dodo.

Some of my dodo figures (Dr Karl Shuker)

And finally: The last preserved dodo may be long gone, but thanks to coelacanth discoverer Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer's great-aunt Lavinia, there may still be one surviving dodo egg. Lavinia had received it from a family friend who worked as a sea captain and frequently travelled between South Africa and Mauritius, where he claimed to have found the egg in a swamp. In 1915, she in turn gave it to her grand-niece Marjorie, who later became the curator of South Africa's East London museum - to where she famously returned from the docks one December afternoon in 1938 with the very oily but zoologically priceless body of the first scientifically-recorded specimen of a living species of coelacanth.

In August 2010, the museum's present curator, Mcebisi Magadla, announced plans for a tiny sample to be removed from the egg in order for its DNA to be tested, and thus determine conclusively whether it truly is a dodo egg – or whether, as sceptics have suggested, it is nothing more exciting than an ostrich egg.

As yet, however, I have not learnt whether such a test has been conducted, or, if it has been, the result. So if any reader does have information concerning this, I'd be very pleased to hear from you!

Not a dodo egg but rather an egg-dish in the shape of a dodo! (Dr Karl Shuker)

Not a dodo egg but rather an egg-dish in the shape of a dodo! (Dr Karl Shuker)

Published on September 22, 2012 11:54

September 20, 2012

UNMASKING THE MOONRAT - A HAIRY HEDGEHOG THE SIZE OF A CAT!

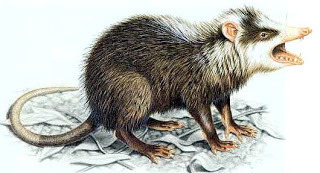

The nominate black-furred subspecies, E. g. gymnura, of the moonrat (Constance Warner)

The nominate black-furred subspecies, E. g. gymnura, of the moonrat (Constance Warner) As a child, animals with unusual names always held an intense fascination for me. So it was inevitable that I would want to learn more about the moonrat!

Sadly, I soon discovered that in spite of its exotic appellation, this wonderful creature, known scientifically as Echinosorex gymnura, does not actually come from the moon, but it is such an amazing-looking animal that anybody could be forgiven for wondering whether it may do! In fact, the marvellous moonrat is from southeastern Asia (specifically the Thai-Malay Peninsula and the islands of Sumatra and Borneo), and it is also called a gymnure ('naked tail'), because its very long slender tail is almost hairless and is covered in scales, rather like a snake! Equally ophidian is the moonrat's loud, threatening hiss that it gives voice to if confronted by predators or by other moonrats invading its territory.

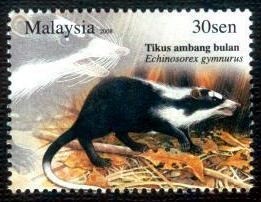

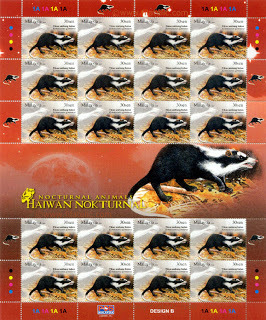

Moonrat postage stamp, Malaysia 2008

Moonrat postage stamp, Malaysia 2008 With a head and body length of 13-16 in, a tail of 8-12 in, and weighing up to 2.75 lb, the moonrat looks very like a gigantic rat - a rat wearing a black mask, and as big as a domestic cat! (In Borneo, moonrats lack the mask because here, uniquely, they are predominantly white all over in colour.) It even occupies a similar ecological niche to true rats. Taxonomically, however, this deceptive animal is something very different, because its closest relatives are not the rodents but the hedgehogs.

For although, outwardly, it doesn't look anything like one, when its anatomy is examined the moonrat is swiftly revealed to be a kind of extra-large, long-tailed hedgehog - but one that is covered in long coarse hair instead of spines.

The moonrat's very distinctive, predominantly white Bornean subspecies, E. g. alba (FactZoo.com)

The moonrat's very distinctive, predominantly white Bornean subspecies, E. g. alba (FactZoo.com)The moonrat's external appearance has some other surprises too. Its very lengthy, mobile snout is plentifully supplied with exceptionally long, bristly whiskers - as are its eyebrows. These whiskers are extremely sensitive to touch, and probably help the moonrat to gauge in the dark whether it is thin enough to pick its way through tight crevices while active at night. Also assisting it do this is the remarkable shape of its body, which although looking very burly from the side, is actually surprisingly narrow, allowing it to squeeze through gaps that seem scarcely wide enough to let it pass. So too do its very short legs.

The moonrat inhabits dense forests and swamps, usually near water. A good swimmer, it is fond of eating fishes, frogs, crabs, clams, and other aquatic creatures, as well as worms and insects. Despite its size and eyecatching appearance, however, as well as the facts that it was first documented scientifically as long ago as 1821 (by Sir Stamford Raffles no less, who named it a year later) and has a lifespan of up to 5 years in its native habitat, the moonrat remains one of the world's most mysterious mammals. This is because it is incredibly shy and hence is rarely seen in the wild.

Moonrat (D. Kirshner)

Moonrat (D. Kirshner) One peculiar thing that we do know about its wild habits, however, is that when the female moonrat makes a nest in which she subsequently gives birth to two babies, the fluid that she secretes from a pair of glands under her tail to mark the nest's entrance possesses a strong ammonia content and has a potent smell that closely resembles rotten onions or garlic! (The male also secretes this same fluid when marking his territory.) So even if our eyes are unsuccessful in catching sight of moonrats, our nose should have far less trouble locating their nests!

The moonrat's memorable name has assisted it in becoming an unlikely villain in a delightful children's book written by Helen Ward. Entitled The Moonrat and the White Turtle and originally published in 1990, it also contains Ward's beautiful full-colour illustrations. Moonrat is the greatly-feared leader of a rascally band of pirate rats, and is driven by one unquenchable ambition – to steal the moon out of the sky and add it to his vast glittering trove of ill-gotten treasure! But does he succeed with his nefarious plot, and who or what is the White Turtle? I'll leave you to discover this excellent book and find out for yourself!

There is also a Los Angeles-based rock group called The Moonrats, but I'm unsure whether their name was gymnure-inspired, or just inspired!

Finally: all that remains to be answered is where the moonrat itself obtained its noteworthy name. However, this appears to be one mystery that is destined to remain unanswered, because in spite of considerable research, I have so far been unable to trace any explanation of its origin. So if anyone can enlighten me concerning this, I'd love to hear from you!

Sheet of moonrat-depicting postage stamps issued by Malaysia in 2008

Sheet of moonrat-depicting postage stamps issued by Malaysia in 2008

Published on September 20, 2012 12:45

September 17, 2012

MORE SKY BEASTS?– SOME HITHERTO-UNPUBLISHED SIGHTINGS OF AERIAL ANOMALIES

In an earlier ShukerNature blog post (click here ), I documented one of my favourite if very radical theories appertaining to mystery creatures. Namely, that some UFOs may actually be living entities – i.e. highly-specialised, undiscovered species of atmosphere-inhabiting sky beast, adapted for an exclusively airborne existence in a vast rarefied realm in the uppermost reaches of our planet where, very oddly in terms of evolutionary diversity, no species endemic to it have ever been formally disclosed.

After he read that blog post, I was contacted on 24 July 2012 by Facebook friend Chris Bond from Sheffield in South Yorkshire, England, who revealed to me that he had personally observed some anomalous aerial phenomena that he could not explain, but whose activity seemed somewhat reminiscent of living organisms. Chris sent me a detailed account of his sightings, together with an illustration of one of them, and has very kindly permitted me to chronicle them here as a follow-up to my previous ShukerNature sky beast article.

Are the vast skies far above us inhabited by extraordinary life forms still awaiting formal scientific discovery?

Are the vast skies far above us inhabited by extraordinary life forms still awaiting formal scientific discovery?Chris described his first sighting as follows:

"The first relevant one that I remember took place in Mount Ambrose in Cornwall in maybe 1991. I used to stand outside my grandparents bungalow smoking roll-ups and, as the sky is relatively clear there, I used to watch the satellites pass overhead. One of these "satellites" was very strange. It looked like a regular satellite or medium magnitude star, but I can only describe its movement as how I would imagine a nautilus moves at speed or some other marine animal. The object would instantly brighten and shoot forward some distance, then dim as it slowed down until it was no longer visible. Then it would repeat the process, moving across the sky in bursts of energy. At the time it reminded me of some sort of marine animal propelling itself by shooting water out through its shell, in pulses, from some vague memory of footage of something similar seen many years before."

Sighting #2 was no less intriguing:

"The second was even stranger. One spring morning in 1992, at around 4 am, I was walking home from my brother's in Plymouth and there's a spot by Patna Place where the ground drops and, over a wall, you can see most of Plymouth Sound below. I noticed in the distance what looked like a very bright star, but this one was bright red. After some minutes, and as it grew closer, I began to see the actual shape of the object. I can only describe it as like a massive glowing red seagull. The wings didn't flap; it glided, silently, and the air all around it glowed red. It's difficult to gauge the actual size, but it gave the impression of being very large; passenger jet or larger, but with a very organic shape, just like a seagull. I watched it cross the whole sky over Plymouth Sound, maybe 10-15 minutes in total. I checked for others who might have seen it, but nothing. Any fishermen out on the Sound at the time were no doubt scanning the deep for Morgawr."

Love it!

Chris's third sighting, which is certainly the strangest of them all, inspired him to prepare this drawing. He states that it accurately portrays the movement and arrangement of the objects that he witnessed, but he has transferred the setting from Plymouth to Cornwall (hence Chun Quoit) for artistic regions.

Drawing depicting the aerial objects featured in Chris's third sighting (Chris Bond)

Drawing depicting the aerial objects featured in Chris's third sighting (Chris Bond)Here is his description of this sighting:

"The third is, to me, the most profoundly curious of the lot. I always got the feeling that it was some kind of message, but have never yet fathomed the meaning; maybe something to do with cell division. This too was in Plymouth, at 12:25am on 4 April 1996, at the back of my flat on Allendale Road. I wrote it down immediately so as not to forget anything. It was a particularly good night for astronomy. Very clear! There was a total lunar eclipse at that very time; the moon was bright orange-red. The comet Hyakutake was also visible, though hidden to me at that point due to my house being in the way. I was studying the eclipse when I caught an incredibly bright star in the corner of my eye, slowly rising up from the horizon; again it was bright red. Initially, I thought that the colour may have due to the eclipse, but soon realised that it was way too bright, and that the moon would in no way affect the colour of a star some distance away in the sky. My attention turned to the star. When it had reached a point roughly 45 degrees up from the horizon it suddenly stopped dead and for a few seconds it just sat there, brightly twinkling. Then, it suddenly "exploded" into two, of equal size and magnitude to the first. These two stopped a short distance away from each other. The two then repeated the division, forming 4; then again, to form 8. They were by this point arranged in a formation which reminded me of Cassiopeia, but a bit larger. The objects stayed there for a few seconds, then suddenly shot off towards the opposite horizon at breakneck speed; keeping the Cassiopeia-like formation the whole way, until they disappeared in the direction of Cornwall. After they disappeared I looked down at a cat which was sat a few feet away from me; it was still looking up at the sky. The whole episode was completely silent and I can only describe the objects and their movement as unearthly, and very beautiful. The Red Arrows performed over Plymouth a few days later, and they looked like slugs in the sky in comparison. There were no clouds and I'm certain that they weren't lasers. There is nothing that I could even vaguely compare to them. I saw a close friend the next day and before I'd had a chance to say anything he informed me that he'd seen UFOs "dancing" around the comet the night before. I read reports in UFO Magazine a month or two later that similar objects had been seen over Dorset that night, about an hour before my sighting; and therefore just prior to the eclipse."

Chris also mentioned a fourth sighting, which he made while in the company of a friend, and which, though seemingly less allied to the sky beast category of UFO sightings than the previous three, is worth including here if only because Chris feels that all four observations may be in some way connected, in spite of their morphological disparity:

"The last is probably less relevant to your blog post, so I will be brief. About 3 years ago now, at Beacon near Camborne in Cornwall, a friend was giving me a lift in his car. As we were pulling up to his drive he pointed out an object moving in the sky, at maybe 100m above the rooftops. It appeared to me like an upturned black dustbin, and of about the same size, and was rotating on an axial tilt of about the same as the earth at roughly one rotation per second, maybe slightly slower. It was moving through the sky at a fairly slow pace, but seemed effortless and mechanical, but very precise. It did not deviate in its trajectory whatsoever and did not seem affected by breezes. Its movement reminded me of a drone or radio controlled vehicle. It disappeared towards Redruth, the view obscured by the houses. My friend...had never seen anything similar in his life, although he did once witness a large black cat cross the road at Newbridge near Penzance.

"I feel that the first two of these sightings may interest you in regard to your blog post. The second two, maybe less so, but to me the four seem related, but that might just be my mind trying to make some sense of experiences for which I have very little explanation."

What an interesting series of reports, of which the second and third were particularly intriguing to me. I've read about UFOs splitting into twos or other multiples, almost like celestial cellular division! And who knows - if these really were sky beasts, that is precisely what may have been occurring. The 'seagull' sighting is also reminiscent of others in this genre - the organic 'feel' to the object has been reported many times. Indeed, the company of nine 'flying saucers' famously sighted on 24 June 1947 by private pilot Kenneth Arnold as they flew at supersonic speeds past Mount Rainier in Washington State, USA, were subsequently likened by him to space jellyfishes. I'm not sure what to make of sighting #1 - I can understand what Chris meant when he referred to its motion, but it's rather different from other putative living UFOs that I've read about.

Photograph of Kenneth Arnold with a drawing of one of the nine objects sighted by him on 24 June 1947 (http://podcastufo.com/blog/kenneth-ar...)

Photograph of Kenneth Arnold with a drawing of one of the nine objects sighted by him on 24 June 1947 (http://podcastufo.com/blog/kenneth-ar...)Having said that, I freely confess that I am certainly no expert in ufology – which is where, gentle readers, you come in. Chris has mentioned to me that Sighting #3 was reported to PUFORG, who printed a report at the time, and a short version of the same was published in UFO Magazine some months later, but otherwise this is the first time that the details presented here have been made public. Consequently, if you can add any suggestions, opinions, or additional information regarding the phenomena sighted and reported by Chris, we'd both be very pleased to receive them here.

For more information concerning sky beasts, check out my book Dr Shuker's Casebook: In Pursuit of Marvels and Mysteries (CFZ Press: Bideford, 2008).

Published on September 17, 2012 17:15

September 16, 2012

NANDI BEARS AND DEATH BIRDS - MY TOP TEN DEADLIEST MYSTERY BEASTS !!

Nandi bear by sunset (Markus Bühler)

Nandi bear by sunset (Markus Bühler)Not all mystery beasts on record are shy, reclusive creatures that take great pains to avoid humankind at all cost. Some, conversely, are actively belligerent, ferocious animals that have reputedly attacked and killed people with impunity, or at the very least, if confronted, possess all manner of ingenious but equally devastating ways of dispatching their foolhardy antagonists.

Here, then, in no particular order is my own personal listing of the world's top ten deadliest cryptids – lethal life-forms that only the most brash, or rash, field cryptozoologist is likely to consider pursuing...at their peril!

NANDI BEAR

The year was 1925. A six-year-old girl had been mysteriously abducted from her village in the Nandi region of Kenya by a greatly-feared monster known locally as the chimiset, and Captain William Hichens of the Intelligence and Administrative Services of East Africa had been instructed by the Kenyan government to investigate. Science did not - and still does not - recognise the existence of the chimiset, but it is an all-too-familiar creature to the native Nandi people, and also to European settlers here, who call it the Nandi bear on account of its bear-like head.

Consequently, Hichens took the matter seriously, and set up camp near to a small forest-clad kopje (boulder hill) from where the chimiset reputedly emerged periodically. One night, Hichens was asleep in his tent, with his mongrel hunting dog, Mbwambi, tied to a pole outside, when suddenly:

"...the whole tent rocked; the pole to which Mbwambi was tied flew out and let down the ridge-pole, enveloping me in flapping canvas. At the same moment the most awful howl I have ever heard split the night. The sheer demoniac horror of it froze me still...I heard my pi-dog yelp just once. There was a crashing of branches in the bush, and then thud, thud, thud, of some huge beast making off. But that howl! I have heard half a dozen lions roaring in a stampede-chorus not twenty yards away; I have heard a maddened cow-elephant trumpeting; I have heard a trapped leopard make the silent night miles a rocking agony with screaming, snarling roars. But never have I heard, nor do I wish to hear again, such a howl as that of the chimiset. A trail of red spots on the sand showed where my pi-dog had gone. Beside that trail were huge footprints, four times as big as a man's, showing the imprint of three huge clawed toes, with trefoil marks like a lion's pad where the sole of the foot pressed down. But no lion ever boasted such a paw as that of the monster which had made that terrifying spoor."

Although Hichens pursued these tracks, which did indeed lead to the kopje, and spent at least a week searching the forest for whatever had made them, he did not succeed in his quest - but in view of his dog's dreadful fate, that may not have been such a bad thing!

The Nandi bear may well comprise more than one type of animal. As revealed by cryptozoologist Dr Bernard Heuvelmans in his pioneering book On the Track of Unknown Animals (1958), accounts of several wholly distinct animals appear to have been erroneously assigned by earlier authors at one time or another to this formidable mystery beast - involving spotted hyaenas, unusually large baboons, honey badgers, aardvarks, even the occasional murderous witchdoctor. However, there may also be one or two genuinely unknown species involved.

Some Nandi bear reports describe hyaena-like beasts, but far larger than any known to exist today, and sporting a dark shaggy pelage quite unlike that of the spotted hyaena Crocuta crocuta, which is the world's largest modern-day hyaena species. Also, the Nandi bear is far more aggressive than typical contemporary hyaenas. Prior to the close of the Pleistocene epoch, a mere 10,000 years ago, however, Africa was known to harbour a terrifying species called the short-faced hyaena Procrocuta brevirostris. Although related to the small modern-day brown hyaena Hyaena brunnea, it was characterised by its enormous lion-sized stature, and also by its short bear-like muzzle and active hunting behaviour (in marked contrast to the carrion-sustaining lifestyle typifying today's hyaenas). If such a creature as this has persisted into the present day within the dense little-explored forests of Kenya's Nandi region, we may not need to seek further for the Nandi bear's identity.

Is the Nandi bear a living chalicothere? (Philip72/Wikipedia)

Is the Nandi bear a living chalicothere? (Philip72/Wikipedia)Moreover, Pleistocene Africa was also home to a bizarre type of ungulate known as a chalicothere, which resembled a horse-sized hyaena in general outline, and possessed sharp claws instead of hooves typical of other ungulates. Although chalicotheres were herbivores, a brief sighting of such a creature could well convince a native hunter or anyone else not well-versed in zoological taxonomy that they had encountered a giant hyaena. Accordingly, several zoologists have seriously entertained the idea that perhaps a species of African chalicothere survived beyond the Pleistocene into modern times, giving rise to reports of Nandi bears.

One intriguing item of Nandi bear lore that supports this identity is the claim by Kenyan residents that this mystery beast was once quite common here but was almost exterminated in the 1890s by a plague of rinderpest that swept across most of Africa, devastating livestock and wild buffaloes. Rinderpest, of course, principally kills ungulates, not carnivores - a fact cited by sceptical scientists as evidence that the Nandi bear is a native fantasy. Yet if this animal is a species of chalicothere, it could indeed be susceptible to rinderpest.

And if, like some other ungulates, including bull elephants, hippos, Cape buffaloes, and peccaries, chalicotheres display bouts of savage unpredictable aggression (vegetarian lifestyle notwithstanding), we can easily comprehend why the Nandi bear is so greatly feared.

For additional details on ShukerNature re the Nandi bear, click here .

ARTRELLIA (PAPUAN DRAGON)

After spending many hard hours on the trail of wallabies and other animals for food through the jungles bordering the Binatori River, the young Papuan hunter was weary. Consequently, he was very pleased to spy an extremely large, fallen tree trunk lying on the ground nearby, half-hidden in the lush green undergrowth. Hurrying over, he sat down in aching relief upon its supporting, welcoming bole - but not for very long. Seconds later, his sturdy seat began to move, raising itself - and him - off the ground in a violent surge of energy. Leaping off in alarm, the hunter turned round - and was horrified to discover that the 'tree trunk' was actually a gigantic lizard! And as he gazed, motionless with fear, the lizard reared up onto its hind legs like a veritable dragon, standing more than 10 ft high, with its long tail splayed out behind, and its huge crocodile-like jaws open wide, revealing a brimming armoury of dagger-like teeth - and a long orange-yellow tongue, which flicked rapidly like living fire!

Faced with this towering monstrosity, the hunter did what any self-respecting person would do in similar circumstances - he fled with all speed, back along his hunting trail to the safety of his home village, Giringarede, not even glancing back to see whether his saurian aggressor was following him. Happily, it was not - or, at least, not swiftly enough, because he reached his village safely, and lived long enough to tell the dramatic tale of his escape to his children, and to theirs. He was one of the lucky ones - not everyone survives an encounter with what the tribes inhabiting Papua New Guinea (the eastern half of New Guinea) call the artrellia, and what cryptozoologists call the Papuan dragon.

With a total area of approximately 342,000 square miles, New Guinea is the world's second largest island after Greenland, and contains immense expanses of tropical jungle and swamplands only sparsely explored by scientists and western travellers. Not surprisingly, therefore, cryptozoologists believe that it holds considerable promise as a locality for major zoological discoveries in the future - a belief fuelled by reports of several mysterious creatures still unrecognised or unidentified by science.

One of the most spectacular of these cryptic creatures is the artrellia, which the local people describe as a gigantic crocodile-like lizard or dragon, up to 30 ft long, capable of climbing trees, breathing fire, and liable to kill and eat any humans who chance upon it amid its dense jungleland domain. Nor are artrellia reports confined to native testimony.

A number of British, American, and Japanese soldiers stationed in Papua during World War II reported seeing huge lizards estimated by them to be 15-20 ft long prowling the forests. Similarly, in 1960, David Marsh, Port Moresby's district commissioner, revealed that he had made two giant lizard sightings in western Papua during the early 1940s.

In 1980, an international scientific expedition called 'Operation Drake' visited Papua New Guinea, and its leader, renowned explorer Lieutenant-Colonel John Blashford-Snell, was particularly interested by native testimony and accounts regarding the artrellia, including the incident recalled at the beginning of this article.

After bribing local hunters to capture an artrellia and bring it to him, he was delighted when they succeeded in doing precisely that - enabling its species to be formally identified at last. It was a monitor lizard, specifically Salvadori's monitor Varanus salvadorii, also called the tree dragon, which is the world's longest known species of lizard, and has been confirmed to attain lengths of up to 15.5 ft.

Salvadori's monitor – the real artrellia?

Salvadori's monitor – the real artrellia?Having said that, the specimen obtained for Blashford-Snell was hardly a monster, measuring only a little over 6 ft long. When its body was examined, however, it was found to be just a youngster, a juvenile specimen, so its potential maximum adult size could only be guessed at. Needless to say, its flickering orange-yellow tongue would certainly have been sufficient to inspire local claims that it breathed fire like a dragon. In addition, as revealed by one of its common names, this species does climb trees, and large monitors are indeed known to rear up and even run for a short time on their hind legs - all of which corresponds well with native accounts of the greatly-feared artrellia.

During this same expedition, moreover, one team member had a close, albeit brief, encounter with an artrellia that appeared to be rather more akin to the legendary giant specimens spoken of by the tribespeople. English zoologist Ian Redmond had been sitting quietly by a waterhole in a creek bed below the level of the forest floor in the Fly River region of Papua when he heard a series of heavy crunching footsteps coming ever closer across the forest's leaf-covered ground, sounding like human steps and not at all like the lighter, rapid scurrying noise that one would expect from a lizard.

Thinking that it was a colleague playing a joke on him, Redmond refused to look round at first, but when his curiosity finally got the better of him he did turn round - and saw an exceedingly large monitor lizard looking at him over a log close by. He couldn't see the whole lizard, just its head and shoulders - but they were as big as a horse's! And as Salvadori's monitor does not have a disproportionately large head and shoulders, how big must the rest of this lizard have been? Redmond bent down to reach for his camera, but as he did so the lizard moved away, and he did not see it again.

The famous gigantic Komodo dragon Varanus komodoensis of Indonesia, up to 10 ft long, is proof enough that huge - and occasionally man-eating - monitor lizards do exist. And amid the vast unexplored rainforests of New Guinea, extra-large specimens of Salvadori's monitor could readily thrive, avoided by native people, rarely spied by western visitors, and occupying much the same top predator niche here that their Komodo relatives occupy on their eponymous Indonesian island home.

NUNDA (MNGWA)

A mystery beast inciting immense terror among local people sharing its homeland is the mngwa or nunda - Swahili for 'strange one'. Aptly named and reputedly indigenous to the coastal forests of mainland Tanzania, this unidentified creature is said to be an enormous and singularly ferocious grey cat, larger than a lion and further differentiated from all known species of African cat by its peculiar brindled fur.

During the 1920s, there was a spate of savage killings claimed to be the work of a nunda, in which several people in the Tanzanian coastal village of Lindi were attacked and their bodies horrifically mangled. As with the Nandi bear rampage described earlier, Captain William Hichens investigated, but although he did not succeed in spying a nunda, he did examine the body of one of its victims, and found a matted clump of strange brindle-grey fur clenched in his fist, as if he had torn it out while attempting to fight off his feline assailant.

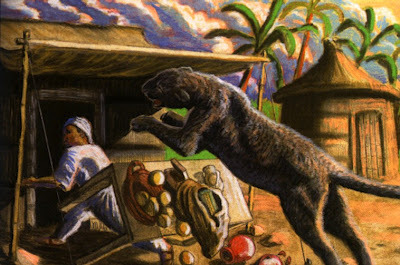

A nunda attack (William Rebsamen)

A nunda attack (William Rebsamen)Another European investigator, Patrick Bowen, observed some nunda pawprints, which resembled those of a leopard but were as large as a lion's. Cryptozoologists have proposed that the nunda may be a giant form of golden cat Profelis aurata, an extremely savage species with very varying fur colour and patterns, which might conceivably account for the nunda's odd brindled pelage.

For a more detailed ShukerNature blog post re the nunda, click here .

HIDE

Several seemingly unknown species of extra-large jellyfishes have been reported over the years, but these have usually been fairly typical in shape, if not in size. However, there is one very macabre mystery beast on record that may well be a scientifically-unknown representative of one of their more specialized, deepwater forms.

This is the singularly eerie creature spied in 1953 by an Australian diver while testing a new type of deep-sea diving suit in the South Pacific. As revealed by Eric Frank Russell in his book Great World Mysteries (1957), the diver had been following a shark, and was resting on the edge of a chasm leading down to much deeper depths, still watching the shark, when an immense, dull-brown, shapeless mass rose up out of the chasm, pulsating sluggishly, and flat in general outline with ragged edges.

Despite appearing devoid of eyes or other instantly-recognizable sensory organs, this malign presence evidently discerned the shark's presence somehow, because it floated upwards until its upper surface made direct contact. The shark instantly gave a convulsive shudder, and was then drawn without resistance into the hideous monster's body. After that, the creature sank back down into the chasm, leaving behind a very frightened diver to ponder what might have happened if that nightmarish, nameless entity had not been attracted towards the shark!

In the past, a deep-sea octopus has been put forward as a possible identity for this disturbing creature, but in reality, as I first revealed in my book From Flying Toads To Snakes With Wings (1997), a deep-sea jellyfish is a much more plausible candidate. To begin with, all octopuses have tentacles, but a number of jellyfishes (including various known deep-sea species) do not. However, all jellyfishes are armed with nematocysts (sometimes on their body surface as well as upon their tentacles), which in some species, as noted earlier, can elicit paralysis or indescribable pain. Accordingly, if the amorphous creature observed by the diver was equipped with a plentiful supply of these, the immediate paralysis of the shark could be readily explained.

In addition, although the shark's killer lacked such obvious sensory organs as eyes (this is true of all jellyfishes), its ability to detect the shark can again be explained via the jellyfish identity. This is because these animals possess primitive sensory structures receptive to water movements. Hence the creature would have been able to detect the water disturbances created by the shark's swimming. How fortunate it was, therefore, that, by choosing to watch the shark, the diver had remained stationary!

Deepstaria enigmatica, a bizarre, flattened species of deep-sea jellyfish (http://2.bp.blogspot.com)

Deepstaria enigmatica, a bizarre, flattened species of deep-sea jellyfish (http://2.bp.blogspot.com)Deep-sea jellyfishes similar (though not identical) to the above-described creature encountered by the diver may explain Chilean legends of a grotesque sea monster termed the hide, documented by Jorge Luis Borges in his famous work The Book of Imaginary Beings (1969). According to Borges, the hide is an octopus that resembles in shape and size a cowhide stretched out flat, with countless eyes all round its body's perimeter, and four larger ones in the centre. It lives by rising to the surface of the sea and swallowing any animals, or people, swimming there.

As this description makes no mention of tentacles, it seems highly unlikely that such a beast (assuming that it really does exist) could be any form of octopus. In any event, octopuses only have a single pair of eyes, not a whole series around the edge of their body and two pairs of principal eyes. Conversely, many jellyfishes possess peripheral sensory organs called rhopalia, which incorporate simple light-sensitive eyespots or ocelli.

Moreover, although no jellyfish has true eyes, some - such as the common moon jellyfish Aurelia aurita - have four deceptively eye-like organs visible in the centre of their bell (which are actually portions of their gut, known as gastric pouches). In short, a jellyfish candidate provides a far more realistic answer to the question of the hide's identity than an octopus.

In May 2012, a hitherto scarcely-known and somewhat amorphous, sheet-like species of deep-sea jellyfish known as Deepstaria enigmatica hit the global headlines when a specimen was filmed by underwater cameras during a deep-water drilling operation near the U.K. It is usually found at depths of 5000 ft in the south Atlantic Ocean. Who knows what other, and conceivably much more deadly, relatives lurk within the uncharted chasms of our planet's deepest waters?

ETHIOPIAN DEATH BIRD

Just before Ethiopia was invaded by Italy in 1935, archaeologist Byron de Prorok took part in an expedition to the southern Ethiopian province of Walaga, where, as noted in his book Dead Men Do Tell Tales (1943), he was shown a dreaded cavern called Devil's Cave. Here, according to native tradition, live flocks of a small but terrible blood-drinking bat known as the death bird, which emerge at night and surreptitiously drink the blood of local goatherds while they sleep until they eventually die and are replaced by new goatherds.

Does an unknown species of Old World blood-drinking bat lurk in Ethiopia's Devil's Cave?

Does an unknown species of Old World blood-drinking bat lurk in Ethiopia's Devil's Cave?As the only sanguinivorous bats known to science are the three species of vampire, all of which are found only in the New World, de Prorok did not believe these stories - until he was taken to the goatherds' camp nearby, where he saw that all of the herders had wounds on their arms resembling small puncture wounds. He also saw one herder close to death - little more than a skin-clothed skeleton surrounded by blood-stained rags.

Over 70 years have passed since then and the death bird's identity is still a mystery, but with sizeable areas of Ethiopia scarcely explored due to civil unrest, it is likely to remain so for the foreseeable future.

MONGOLIAN DEATH WORM

Also known to the nomadic inhabitants of the southern Gobi desert as the allghoi khorkhoi ('intestine worm') because of its supposed resemblance to a living intestine, the death worm is said to be up to 5 ft long, dark red in colour with brown spots, and has pointed projections at both ends of its body. Spending much of the year hidden beneath the desert sands, it emerges only during the two hottest months (June and July), but is avoided by humans and even camels, because it can kill instantly, and via two wholly different means.

This deadly mystery beast can allegedly squirt a highly virulent, corrosive venom, which presumably acts by burning its way through the victim's flesh into the bloodstream like a potent acid. It can also kill much more mysteriously, by touch. Indeed, its lethal power can even be transmitted via metallic objects - as fatally discovered by a visiting geologist many years ago, when he accidentally prodded a death worm with a metal rod.

If true, this suggests that the worm can kill by electrocution, and must therefore be able to generate electricity, like the electric eel and certain other fishes. At present, however, despite a number of expeditions in search of this macabre mystery beast led by Czech explorer Ivan Mackerle during the 1990s, and several others by additional field investigators in more recent years, the death worm's reality has yet to be formally confirmed.

Mongolian death worm, shocking and spitting (Philippa Foster)