Marc Tyler Nobleman's Blog, page 107

May 23, 2013

Plausible nonsense

In a 3/18/13 New Yorker “Talk of the Town” piece by Rebecca Mead resides this gem:

So much more could be written about this, but I don’t know that I yet have the experience to be one to do so. However, I’m shopping around a manuscript that may set me on that path. It’s a departure for me—picture book yes, nonfiction no.

It’s funny, too. I need some way to redirect the energy I am not putting into cartooning at the moment.

I hope to be able to elaborate here soon.

You—or someone—may be shocked…

The books of Dr. Seuss, the pen name of Theodor Geisel, depend on what Donald Pease, a professor of English literature at Dartmouth, refers to in his biography of Geisel as “plausible nonsense.” “Children will grant you any premise, but after that—you’ve got to stay on the same key,” Geisel told one interviewer.

So much more could be written about this, but I don’t know that I yet have the experience to be one to do so. However, I’m shopping around a manuscript that may set me on that path. It’s a departure for me—picture book yes, nonfiction no.

It’s funny, too. I need some way to redirect the energy I am not putting into cartooning at the moment.

I hope to be able to elaborate here soon.

You—or someone—may be shocked…

Published on May 23, 2013 04:00

May 22, 2013

Bill Finger’s sole Batman credit in his lifetime

In 25 years of writing Batman stories, including some of the most popular ever, Bill Finger was officially credited as a writer (or co-creator) precisely zero times. (By that I mean in a credit box within the story. In the 1960s, editor Julie Schwartz, bless him, did sneak Bill’s name into the backmatter at least a couple of times.)

One time only, Bill did get to see his name prominently displayed on a first-run story—but it was not in print. Bill was the only writer of Batman comics who (with Charles Sinclair) also wrote an episode of the 1966 TV show that made Batman’s popularity go mainstream.

Small screen was big time on one level, but in the grand scheme, small solace for a marginalized career.

Speaking of TV credits, here is what the credits for the landmark Batman: The Animated Series could’ve looked like if things had played out differently…fairly:

courtesy of @hrguerra

courtesy of @hrguerra

Note the order.

One time only, Bill did get to see his name prominently displayed on a first-run story—but it was not in print. Bill was the only writer of Batman comics who (with Charles Sinclair) also wrote an episode of the 1966 TV show that made Batman’s popularity go mainstream.

Small screen was big time on one level, but in the grand scheme, small solace for a marginalized career.

Speaking of TV credits, here is what the credits for the landmark Batman: The Animated Series could’ve looked like if things had played out differently…fairly:

courtesy of @hrguerra

courtesy of @hrguerraNote the order.

Published on May 22, 2013 04:00

May 21, 2013

“Boys of Steel” book report by an author's son

It’s always an honor when a young person chooses a book you wrote for a school project. It is a special honor when that young person happens to be the child of a fellow author. (Not every writer passes on genetic code for a talent in writing but I suspect all writers hope we pass on at least refined taste in writing.)

The young man’s name is Max. The fellow author, his mom, also happens to be my friend. Her name is Jennifer Allison. She also gave birth to Gilda Joyce via a series of mystery novels for young readers.

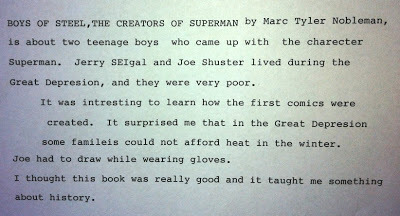

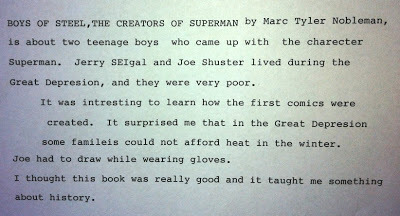

Here is Max’s report, which I find both flattering and factually sound:

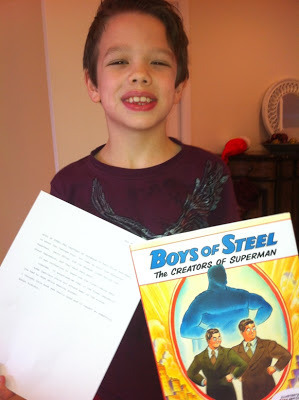

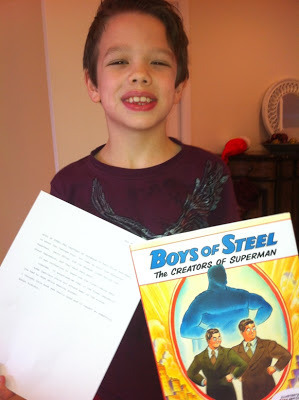

Here is Max:

Thank you Max! You are now a Boy of Steel, too. And Jennifer will be featured on this blog again later this year. I won’t say why yet but will give this clue. Maybe this is one for Gilda Joyce herself to solve...

The young man’s name is Max. The fellow author, his mom, also happens to be my friend. Her name is Jennifer Allison. She also gave birth to Gilda Joyce via a series of mystery novels for young readers.

Here is Max’s report, which I find both flattering and factually sound:

Here is Max:

Thank you Max! You are now a Boy of Steel, too. And Jennifer will be featured on this blog again later this year. I won’t say why yet but will give this clue. Maybe this is one for Gilda Joyce herself to solve...

Published on May 21, 2013 04:00

May 20, 2013

Sandy Hook Elementary author variety show, 2/12/13

More photos from the author variety show (contributed by and used with permission of the school):

me fumbling through emceeing with the other authors in the wings

me fumbling through emceeing with the other authors in the wings

taking bows: Mike Rex, Susan Hood, Meghan McCarthy, Vincent X. Kirsch, Tracy Dockray, Bruce Degen, Katie Davis, Daniel Kirk, easel,Alan Katz, projector, Bob Shea, Tad Hills, me

taking bows: Mike Rex, Susan Hood, Meghan McCarthy, Vincent X. Kirsch, Tracy Dockray, Bruce Degen, Katie Davis, Daniel Kirk, easel,Alan Katz, projector, Bob Shea, Tad Hills, me

levity

levity

me fumbling through emceeing with the other authors in the wings

me fumbling through emceeing with the other authors in the wings

taking bows: Mike Rex, Susan Hood, Meghan McCarthy, Vincent X. Kirsch, Tracy Dockray, Bruce Degen, Katie Davis, Daniel Kirk, easel,Alan Katz, projector, Bob Shea, Tad Hills, me

taking bows: Mike Rex, Susan Hood, Meghan McCarthy, Vincent X. Kirsch, Tracy Dockray, Bruce Degen, Katie Davis, Daniel Kirk, easel,Alan Katz, projector, Bob Shea, Tad Hills, me  levity

levity

Published on May 20, 2013 04:00

May 19, 2013

One way to spread the word about Bill Finger

When my daughter was four, and I was in the thick of Bill Finger research, I interviewed her on camera about her life thus far. A transcribed excerpt (insert giggles after most of her answers):

So yes, I scarred her.

When she was eight, I spoke at her school and showed this 40-second clip. Her classmates, not surprisingly, loved it. (It is always fun to see home movies of one of your own.)

She later reported that some kids (mainly boys) had adopted “Bill Finger” as a catchphrase under the same conditions. In other words, when they were asked a question (by friends, not teachers), the answer often given was “Bill Finger.”

Bill Finger is now a meme—a verbal, regional one, anyway.

I didn’t orchestrate it or even expect it, but I am thrilled by it.

Anything that gets people talking about Bill is a good thing.

MTN: What do I do all day?

daughter: Work.

MTN: What’s my job?

daughter: (pause) Bill Finger.

MTN: What do I do?

daughter: Bill Finger.

MTN: What does that mean?

daughter: Bill Finger.

MTN: Who’s Bill Finger?

daughter: Bill Finger.

MTN: Is that my friend?

daughter: Yes.

MTN: What’s your favorite color?

daughter: Bill Finger.

So yes, I scarred her.

When she was eight, I spoke at her school and showed this 40-second clip. Her classmates, not surprisingly, loved it. (It is always fun to see home movies of one of your own.)

She later reported that some kids (mainly boys) had adopted “Bill Finger” as a catchphrase under the same conditions. In other words, when they were asked a question (by friends, not teachers), the answer often given was “Bill Finger.”

Bill Finger is now a meme—a verbal, regional one, anyway.

I didn’t orchestrate it or even expect it, but I am thrilled by it.

Anything that gets people talking about Bill is a good thing.

Published on May 19, 2013 04:00

May 16, 2013

The Dinobunnies dominate

On 3/8/11, I spoke at Pleasant Ridge Elementary in Overland Park, KS, notable for being the first school in which I sat in a bathtub in the library. (Also notable for being a great school.)

More than a year later, the school shared some flattering news about its Battle of the Books competition. A group of 4th graders who had lost the previous year changed their team name and tried again as 5th graders. In 5/11, they won. The team name?

The Dinobunnies.

posted with permission (two stuffed animals were harmed in the making of that mascot)

posted with permission (two stuffed animals were harmed in the making of that mascot)

During my presentations, after polling the audience, I sketch a couple of characters. Invariably, one ends up being a dinobunny (sometimes dino-bunny, sometimes rabbitosaurus).

(not taken at Pleasant Ridge but he always looks the same)

(not taken at Pleasant Ridge but he always looks the same)

More than a year later, the school shared some flattering news about its Battle of the Books competition. A group of 4th graders who had lost the previous year changed their team name and tried again as 5th graders. In 5/11, they won. The team name?

The Dinobunnies.

posted with permission (two stuffed animals were harmed in the making of that mascot)

posted with permission (two stuffed animals were harmed in the making of that mascot)During my presentations, after polling the audience, I sketch a couple of characters. Invariably, one ends up being a dinobunny (sometimes dino-bunny, sometimes rabbitosaurus).

(not taken at Pleasant Ridge but he always looks the same)

(not taken at Pleasant Ridge but he always looks the same)

Published on May 16, 2013 04:00

May 14, 2013

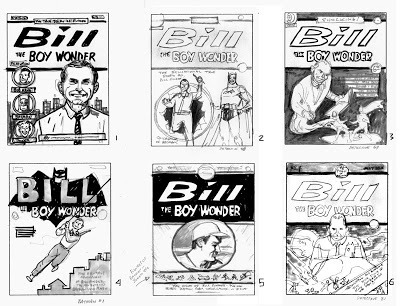

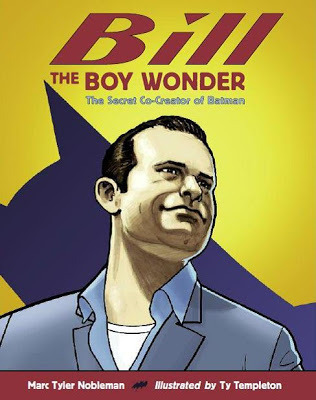

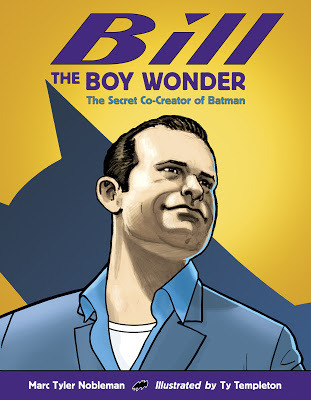

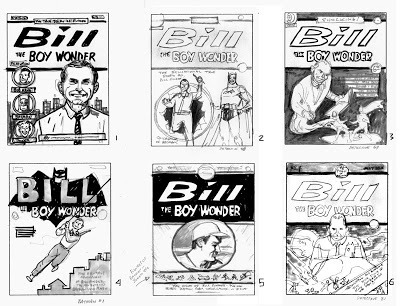

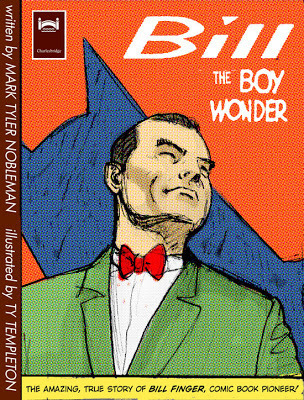

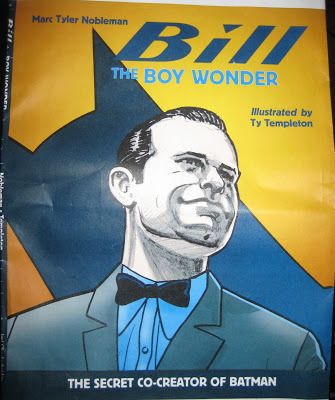

Bill the Boy Wonder: The Unused Covers of Ty

Ty Templeton, artist magnifico of numerous stories including Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman, permitted me to show sketches of cover ideas for the book.

1/21/11:

Including notes by Ty.

Including notes by Ty.

These were homages to early Batman comics. While I liked that idea on one level, ultimately I wanted our book iconography to stand on its own—to avoid referencing existing images. I also didn’t want to represent Bill as Batman himself. Though there are parallels (life in the shadows, namely), it seemed inconsistent with the tone of the story. Bill is the hero of the story, but not quite heroic; his fatal flaw is a lack of self-defense—emphatically not Batman-esque.

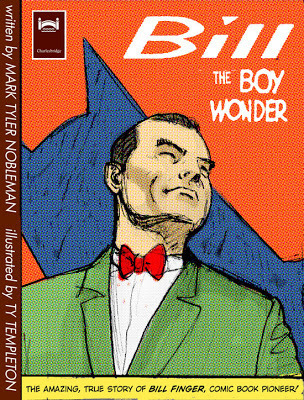

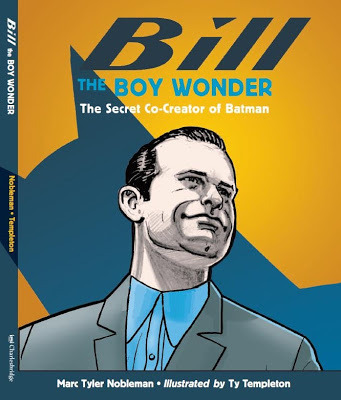

3/7/11:

I loved the angled, almost subverted silhouette. But I felt the cover overall was too colorful for Batman. I specifically did not like orange. I also did not prefer vertical type treatment for our names.

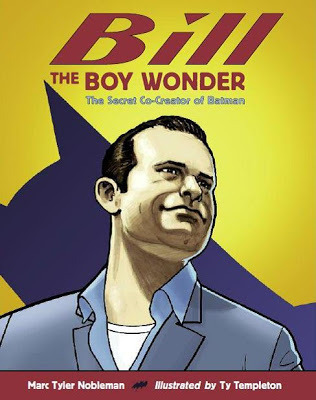

8/21/11:

Dramatic improvement in color. But I wanted my name and Ty’s to be on equal footing. And I wanted the subtitle, which contains the most marketable word on the cover, to be higher. Also, the bow tie seemed too twee; besides, several I asked said Bill did not wear them.

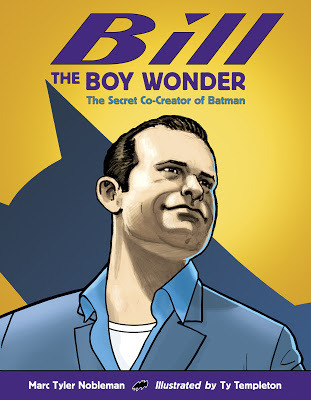

9/6/11:

Names look much better. Bow tie gone but top-buttoned shirt not much less twee.

10/24/11:

Finally we get a bat! And a loose collar! But the red is Superman, not Batman. For a replacement color, I suggested purple as a nod to the original color of Batman’s gloves.

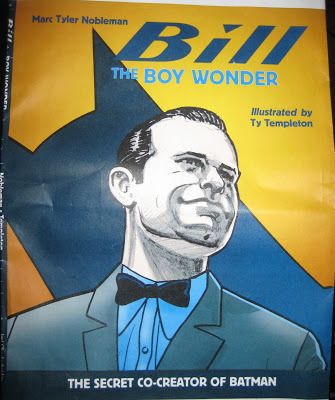

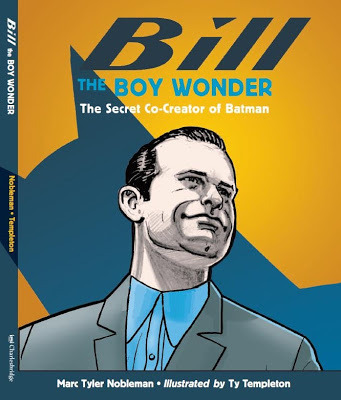

The winner:

1/21/11:

Including notes by Ty.

Including notes by Ty.These were homages to early Batman comics. While I liked that idea on one level, ultimately I wanted our book iconography to stand on its own—to avoid referencing existing images. I also didn’t want to represent Bill as Batman himself. Though there are parallels (life in the shadows, namely), it seemed inconsistent with the tone of the story. Bill is the hero of the story, but not quite heroic; his fatal flaw is a lack of self-defense—emphatically not Batman-esque.

3/7/11:

I loved the angled, almost subverted silhouette. But I felt the cover overall was too colorful for Batman. I specifically did not like orange. I also did not prefer vertical type treatment for our names.

8/21/11:

Dramatic improvement in color. But I wanted my name and Ty’s to be on equal footing. And I wanted the subtitle, which contains the most marketable word on the cover, to be higher. Also, the bow tie seemed too twee; besides, several I asked said Bill did not wear them.

9/6/11:

Names look much better. Bow tie gone but top-buttoned shirt not much less twee.

10/24/11:

Finally we get a bat! And a loose collar! But the red is Superman, not Batman. For a replacement color, I suggested purple as a nod to the original color of Batman’s gloves.

The winner:

Published on May 14, 2013 04:00

May 11, 2013

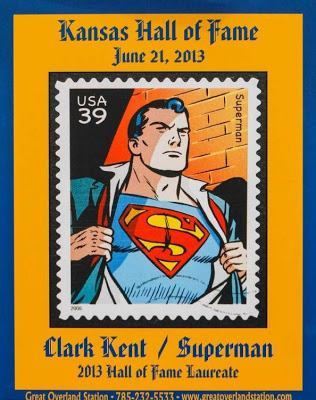

Superman honored in both native and adoptive homes

In October 2012, Cleveland, the city in which Superman was created, installed an exhibit about him in the airport.

In June 2013, Kansas, the state in which Superman crash-landed, will induct him (as well as Clark Kent) into its hall of fame.

What is your city doing to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the world’s first superhero?

In June 2013, Kansas, the state in which Superman crash-landed, will induct him (as well as Clark Kent) into its hall of fame.

What is your city doing to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the world’s first superhero?

Published on May 11, 2013 04:00

May 10, 2013

Persistence at—and before—school visits

Several years ago, I emailed Marjorie Cohen, a teacher at Cold Spring Elementary in Potomac, MD, introducing myself as an author who speaks in schools. I’d come across her name in the alumni magazine of our alma mater, Brandeis University.

I didn’t hear back. I tried again.

I didn’t hear back again.

In 2012, the school booked me through another channel. I had forgotten the Marjorie connection but she reminded me after I got there.

The theme of my standard school presentation is persistence. I don’t come in and announce this; I work it in gradually, stealthily, narratively. But the takeaway is clear: persistence (perhaps even more than talent) is essential to success.

After I spoke at Cold Spring, before the kids were dismissed, Marjorie stood up and asked for their attention.

Then she confessed.

She told them how I had emailed her and how she dismissed me twice. But now that she’d heard me speak, she admitted she should’ve paid attention.

I don’t fault her. Regardless of what we do, many of us are pitched a lot. We don’t have the bandwidth to fully consider each pitch.

She said she was glad I was persistent. She was glad I came. And now that she saw my focus, it all made sense.

In fact, it worked out better this way because Marjorie was able to reinforce my assembly-long message with a short, real-life anecdote. “The guy who just tried to persuade you to adopt persistence actually walks the walk—and it got him here, despite me.” (Paraphrasing, of course.)

It’s one of those spontaneous moments that make it all even more worth it.

I didn’t hear back. I tried again.

I didn’t hear back again.

In 2012, the school booked me through another channel. I had forgotten the Marjorie connection but she reminded me after I got there.

The theme of my standard school presentation is persistence. I don’t come in and announce this; I work it in gradually, stealthily, narratively. But the takeaway is clear: persistence (perhaps even more than talent) is essential to success.

After I spoke at Cold Spring, before the kids were dismissed, Marjorie stood up and asked for their attention.

Then she confessed.

She told them how I had emailed her and how she dismissed me twice. But now that she’d heard me speak, she admitted she should’ve paid attention.

I don’t fault her. Regardless of what we do, many of us are pitched a lot. We don’t have the bandwidth to fully consider each pitch.

She said she was glad I was persistent. She was glad I came. And now that she saw my focus, it all made sense.

In fact, it worked out better this way because Marjorie was able to reinforce my assembly-long message with a short, real-life anecdote. “The guy who just tried to persuade you to adopt persistence actually walks the walk—and it got him here, despite me.” (Paraphrasing, of course.)

It’s one of those spontaneous moments that make it all even more worth it.

Published on May 10, 2013 04:00

May 7, 2013

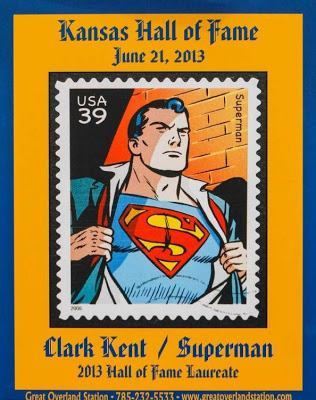

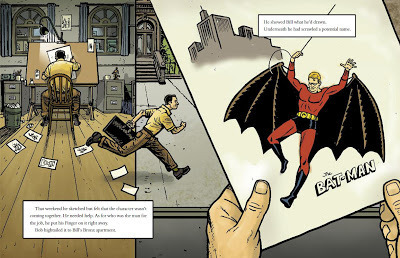

Where art tells the story in "Bill the Boy Wonder"

One of my last steps in writing a picture book is to go through and pinpoint areas where I can cut text. Yes, that is a writing step. Because I’m not cutting meaning. I’m merely eliminating redundancy in instances where the art can show rather than the words tell.

Here are examples from Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman.

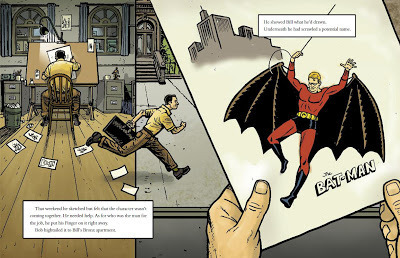

The name of the pivotal character is revealed not in the text but rather in the picture. Yes, it is done with words, but the words are part of the art.

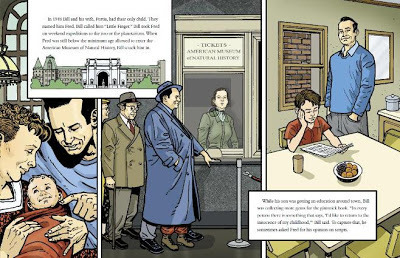

The text says that Bill sneaked his son Fred into the American Museum of Natural History, but doesn’t say how. This means readers must look to the art for the explanation, and kids especially love figuring it out.

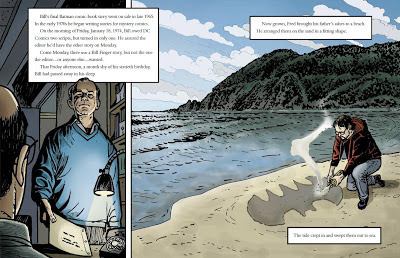

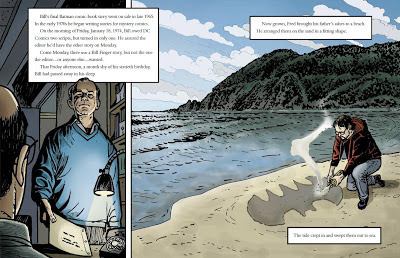

“Fitting shape” is deliberately vague. It forces the eye to the picture where the impact is greater than if I’d simply stated that Fred arranged the ashes into a bat.

Here are examples from Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman.

The name of the pivotal character is revealed not in the text but rather in the picture. Yes, it is done with words, but the words are part of the art.

The text says that Bill sneaked his son Fred into the American Museum of Natural History, but doesn’t say how. This means readers must look to the art for the explanation, and kids especially love figuring it out.

“Fitting shape” is deliberately vague. It forces the eye to the picture where the impact is greater than if I’d simply stated that Fred arranged the ashes into a bat.

Published on May 07, 2013 04:00