Marc Tyler Nobleman's Blog, page 106

June 12, 2013

Bobbuster

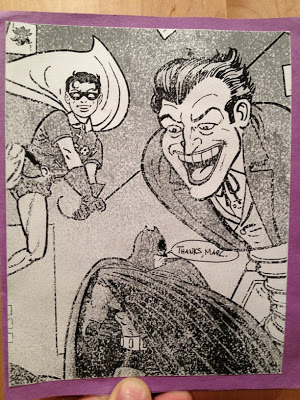

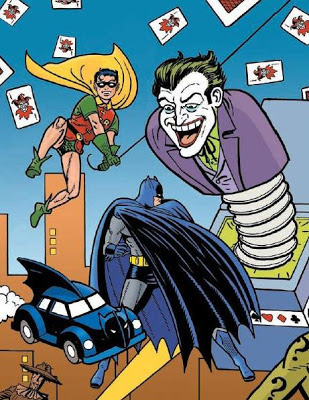

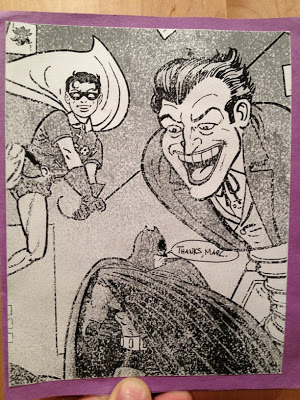

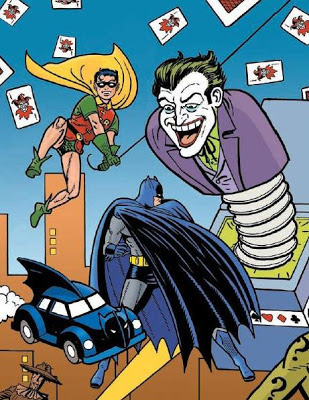

How Ty Templeton signed a copy of Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman:

Used with permission. (Ty’s, not Bob’s.)

Used with permission. (Ty’s, not Bob’s.)

Published on June 12, 2013 21:35

Page two, rule of threes

Just as personalities can be encoded with patterns even the person possessing the personality doesn’t realize, writing styles can, too.

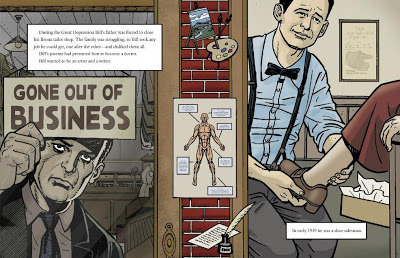

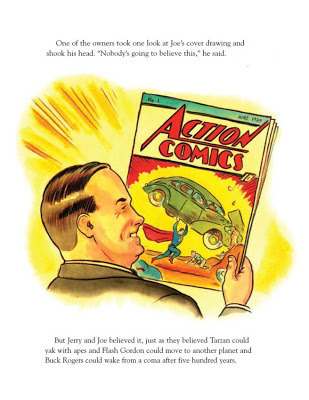

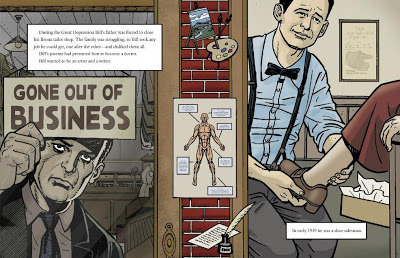

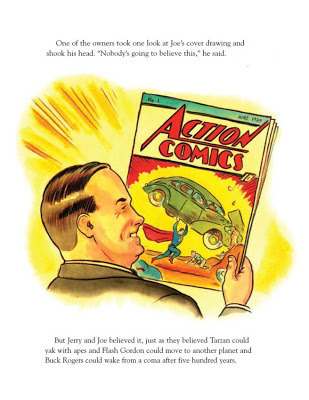

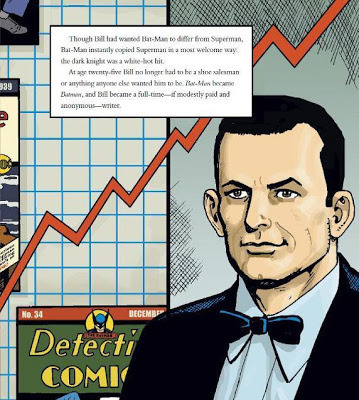

Both of my superhero picture books, Boys of Steel: The Creators of Superman and Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman, take a similar approach on the second page: they use the rule of threes. (This is often associated with humor, but can be used in other ways as well.)

(The previous page teases that Jerry Siegel, Superman writer, was with his friends when at home rather than school; this page is the surprise reveal.)

(The previous page teases that Jerry Siegel, Superman writer, was with his friends when at home rather than school; this page is the surprise reveal.)

The rule of threes in and of itself is not the pattern I’m pointing out—lots of writers use it, of course. The pattern is using the rule of threes on the second page. (Normally I would reserve the word “pattern” for three or more instances, but…okay, head starting to spin.)

I didn’t notice I’d repeated this tactic until after the second book was out. Because I didn’t do it consciously, I probably can’t explain it satisfactorily. It may be as simple as this: it’s a handy device to quicken the pace, which works especially well toward the beginning of a story because it tugs readers in via a rhythm.

Later in both books, I refer back to the threesome. In Boys of Steel, it reiterates the list—twice, actually:

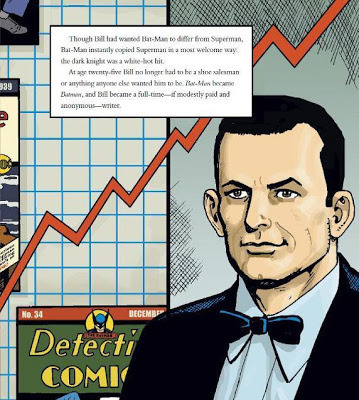

In Bill the Boy Wonder, I refer back less specifically:

Let’s see if I end up using the rule of threes on the second page a third time.

Head spinning faster now.

Both of my superhero picture books, Boys of Steel: The Creators of Superman and Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman, take a similar approach on the second page: they use the rule of threes. (This is often associated with humor, but can be used in other ways as well.)

(The previous page teases that Jerry Siegel, Superman writer, was with his friends when at home rather than school; this page is the surprise reveal.)

(The previous page teases that Jerry Siegel, Superman writer, was with his friends when at home rather than school; this page is the surprise reveal.)

The rule of threes in and of itself is not the pattern I’m pointing out—lots of writers use it, of course. The pattern is using the rule of threes on the second page. (Normally I would reserve the word “pattern” for three or more instances, but…okay, head starting to spin.)

I didn’t notice I’d repeated this tactic until after the second book was out. Because I didn’t do it consciously, I probably can’t explain it satisfactorily. It may be as simple as this: it’s a handy device to quicken the pace, which works especially well toward the beginning of a story because it tugs readers in via a rhythm.

Later in both books, I refer back to the threesome. In Boys of Steel, it reiterates the list—twice, actually:

In Bill the Boy Wonder, I refer back less specifically:

Let’s see if I end up using the rule of threes on the second page a third time.

Head spinning faster now.

Published on June 12, 2013 04:00

June 8, 2013

Bill Finger and gay culture

Bill Finger, uncredited co-creator of Batman, had numerous connections to the gay community.

His first wife Portia was a fixture in the mid-century New York City gay scene.

Bill’s only known child, son Fred, was gay.

Bill’s other A-list superhero co-creation, Green Lantern (Alan Scott edition), was recently reimagined as a gay man.

Bill even weighed in on the nature of Batman and Robin’s relationship.

Bill himself, however, was notoriously not gay.

His first wife Portia was a fixture in the mid-century New York City gay scene.

Bill’s only known child, son Fred, was gay.

Bill’s other A-list superhero co-creation, Green Lantern (Alan Scott edition), was recently reimagined as a gay man.

Bill even weighed in on the nature of Batman and Robin’s relationship.

Bill himself, however, was notoriously not gay.

Published on June 08, 2013 04:00

June 5, 2013

A Bill Finger memorial in Poe Park in the Bronx, part 3 of 3

Part 2.

Here is my proposal for a Bill Finger memorial in the Bronx:

Goal: Install a modest memorial statue in Poe Park for Bill Finger, the uncredited co-creator, original writer, and visual architect of perhaps the world’s most popular superhero, Batman.

Background: I am the author of Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman, which has generated extensive media including NPR’s All Things Considered and Forbes, and has made best-of-the-year lists at USA Today, Washington Post, and MTV. Unprecedented in both subject and format, the book is the first to reveal the full and startling true story behind the creation of Batman in 1939—which took place right there in the Bronx! Finger is like the Bronx itself—too often both are unrecognized for their cultural contributions. An installation to Finger would actually serve a triple purpose: help right a wrong, boost Bronx/NYC tourism, and make pop culture history. It would be the first memorial honoring a superhero creator in NYC, the Superhero Capital of the World.

Why Bill Finger? He’s the main mind behind one of the most influential fictional icons in world history yet his onetime partner, cartoonist Bob Kane, took full credit for Batman. Finger designed Batman’s costume; wrote the first Batman story and many of the best stories of his first 25 years (including his groundbreaking—and heartbreaking—origin); wrote the first stories of popular supporting characters including Robin and the Joker; named Bruce Wayne, Gotham City, and the Batmobile; and nicknamed Batman "the Dark Knight," which has influenced the titles of two of the highest-grossing movies of all time. Yet while Kane never wrote a Batman story, Finger never saw his name as co-creator in a Batman story.

In 1974, after a career in which most of his work was published anonymously, Finger died alone and poor. No obituary. No funeral. No gravestone.

No kidding.

Finger was largely responsible for one of our greatest fictional champions of justice. It is time for justice for Finger himself.

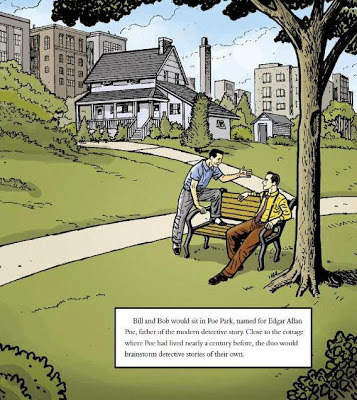

Why Poe Park? Finger and Kane used to brainstorm Batman stories there; see documentation below and attached. In the early 1940s, Bill lived on the Grand Concourse just north of Poe Park. Also, appropriately, Poe was the father of the modern detective story and Batman is known as the World’s Greatest Detective. The Batman-Poe Park connection was recently covered in the New York Times (though the article mistakenly states that Batman was created in Poe Park).

Why now? True, this is not the best time. The best time would have been while Finger was alive. But since we can’t go back, this is the next-best time. There are untold thousands of Batman fans worldwide clamoring for DC Comics to add his name to the Batman credit line. DC may not be able to do that at this time, but we can pay tribute to Finger’s legacy in another meaningful and bold way.

Batman’s significance (beyond the obvious):

Batman is iconic even to those not interested in comic book culture. To a relative few, Batman may seem like just another superhero; however, he is one of the most recognizable fictional characters in world history (let alone the most lucrative superhero of all time). He’s in a class by himself and therefore, so is his original writer/visual architect.

I know New York has been home to countless notable people and historic events. But not many accomplishments (certainly few cultural accomplishments) can compare to the magnitude of Batman’s influence—and it all dates back to a humble start in an unassuming apartment in the Bronx, thanks to the mind of Bill Finger. The Batman imprint at DC Comics puts out at least thirteen Batman-themed comic books every month. (The next most popular, Superman, has only four.) Batman currently appears on the list of the top 20 highest-grossing films of all time...twice (and it’s not just teenaged boys making those movies break records). Batman has starred in TV animation since 1968 and almost continuously since 1992. The examples go on and on.

Target date: 2014 (75th anniversary of Batman, 100th anniversary of Finger’s birth, 40th anniversary of Finger’s death). We would be able to piggyback on other media, though this being an unprecedented project will almost certainly generate media on its own.

Legal aspect: Though Kane’s contract with DC prevents DC from officially co-crediting Finger, DC does give him credit for every story he wrote. What’s more, I have extensive documentation from

Cost: I plan to use Kickstarter and private sources.

Sources for the Batman-Poe Park connection:

Batman & Me, Bob Kane and Tom Andrae, Eclipse Books, 1989, p. 41: "We used to hang out at Poe Park." This is Bob Kane’s autobiography.

The Steranko History of Comics, Volume 1, James Steranko, Supergraphics, Reading, PA, 1970, p. 44: "He asked Bill to meet him later at Edgar Allan Poe Park to discuss a new strip." This is one of the definitive resources on comics history, and the only book to publish an interview with Finger in his lifetime.

Amazing World of DC Comics #1, uncredited article, DC Comics, July-August 1974, p. 28: "Bob asked Bill to meet him later at Edgar Allan Poe Park to discuss a new strip"

Famous 1st Edition (Batman #1) # F-5, Carmine Infantino, DC Comics, February-March 1975, inside front cover: "They agreed to meet later at Poe Park, to work out the details"

interview with Julius Schwartz (longtime DC Comics editor who grew up in the Bronx): "Edgar Allen Poe Park, and there were benches there. And Bill Finger and Bob Kane would meet and plot stories"

I will do all I can to help make this happen and hope to have your support and collaboration. People dressed as Batman will come on a regular basis and take photos with it...

Here is my proposal for a Bill Finger memorial in the Bronx:

Goal: Install a modest memorial statue in Poe Park for Bill Finger, the uncredited co-creator, original writer, and visual architect of perhaps the world’s most popular superhero, Batman.

Background: I am the author of Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman, which has generated extensive media including NPR’s All Things Considered and Forbes, and has made best-of-the-year lists at USA Today, Washington Post, and MTV. Unprecedented in both subject and format, the book is the first to reveal the full and startling true story behind the creation of Batman in 1939—which took place right there in the Bronx! Finger is like the Bronx itself—too often both are unrecognized for their cultural contributions. An installation to Finger would actually serve a triple purpose: help right a wrong, boost Bronx/NYC tourism, and make pop culture history. It would be the first memorial honoring a superhero creator in NYC, the Superhero Capital of the World.

Why Bill Finger? He’s the main mind behind one of the most influential fictional icons in world history yet his onetime partner, cartoonist Bob Kane, took full credit for Batman. Finger designed Batman’s costume; wrote the first Batman story and many of the best stories of his first 25 years (including his groundbreaking—and heartbreaking—origin); wrote the first stories of popular supporting characters including Robin and the Joker; named Bruce Wayne, Gotham City, and the Batmobile; and nicknamed Batman "the Dark Knight," which has influenced the titles of two of the highest-grossing movies of all time. Yet while Kane never wrote a Batman story, Finger never saw his name as co-creator in a Batman story.

In 1974, after a career in which most of his work was published anonymously, Finger died alone and poor. No obituary. No funeral. No gravestone.

No kidding.

Finger was largely responsible for one of our greatest fictional champions of justice. It is time for justice for Finger himself.

Why Poe Park? Finger and Kane used to brainstorm Batman stories there; see documentation below and attached. In the early 1940s, Bill lived on the Grand Concourse just north of Poe Park. Also, appropriately, Poe was the father of the modern detective story and Batman is known as the World’s Greatest Detective. The Batman-Poe Park connection was recently covered in the New York Times (though the article mistakenly states that Batman was created in Poe Park).

Why now? True, this is not the best time. The best time would have been while Finger was alive. But since we can’t go back, this is the next-best time. There are untold thousands of Batman fans worldwide clamoring for DC Comics to add his name to the Batman credit line. DC may not be able to do that at this time, but we can pay tribute to Finger’s legacy in another meaningful and bold way.

Batman’s significance (beyond the obvious):

Batman is iconic even to those not interested in comic book culture. To a relative few, Batman may seem like just another superhero; however, he is one of the most recognizable fictional characters in world history (let alone the most lucrative superhero of all time). He’s in a class by himself and therefore, so is his original writer/visual architect.

I know New York has been home to countless notable people and historic events. But not many accomplishments (certainly few cultural accomplishments) can compare to the magnitude of Batman’s influence—and it all dates back to a humble start in an unassuming apartment in the Bronx, thanks to the mind of Bill Finger. The Batman imprint at DC Comics puts out at least thirteen Batman-themed comic books every month. (The next most popular, Superman, has only four.) Batman currently appears on the list of the top 20 highest-grossing films of all time...twice (and it’s not just teenaged boys making those movies break records). Batman has starred in TV animation since 1968 and almost continuously since 1992. The examples go on and on.

Target date: 2014 (75th anniversary of Batman, 100th anniversary of Finger’s birth, 40th anniversary of Finger’s death). We would be able to piggyback on other media, though this being an unprecedented project will almost certainly generate media on its own.

Legal aspect: Though Kane’s contract with DC prevents DC from officially co-crediting Finger, DC does give him credit for every story he wrote. What’s more, I have extensive documentation from

Cost: I plan to use Kickstarter and private sources.

Sources for the Batman-Poe Park connection:

Batman & Me, Bob Kane and Tom Andrae, Eclipse Books, 1989, p. 41: "We used to hang out at Poe Park." This is Bob Kane’s autobiography.

The Steranko History of Comics, Volume 1, James Steranko, Supergraphics, Reading, PA, 1970, p. 44: "He asked Bill to meet him later at Edgar Allan Poe Park to discuss a new strip." This is one of the definitive resources on comics history, and the only book to publish an interview with Finger in his lifetime.

Amazing World of DC Comics #1, uncredited article, DC Comics, July-August 1974, p. 28: "Bob asked Bill to meet him later at Edgar Allan Poe Park to discuss a new strip"

Famous 1st Edition (Batman #1) # F-5, Carmine Infantino, DC Comics, February-March 1975, inside front cover: "They agreed to meet later at Poe Park, to work out the details"

interview with Julius Schwartz (longtime DC Comics editor who grew up in the Bronx): "Edgar Allen Poe Park, and there were benches there. And Bill Finger and Bob Kane would meet and plot stories"

I will do all I can to help make this happen and hope to have your support and collaboration. People dressed as Batman will come on a regular basis and take photos with it...

Published on June 05, 2013 04:00

June 4, 2013

A Bill Finger memorial in Poe Park in the Bronx, part 2 of 3

Part 1.

The story so far: I proposed installing a memorial to Bill Finger in Poe Park.

What happened next:

Jonathan Kuhn, Director of Art & Antiquities in the NYC Parks department, strikes me as a sharp, candid guy. I’d wager he knows more than anyone else about the history of New York parks (and the history of the history commemorated within them). He has the tone of a man used to fielding the same questions again and again over years—patient with an underlying irritation. Yet he kindly devoted time to me until I better understood the nuances of the parks system policy on installing monuments.

The policy, generally speaking, is this: no.

In Kuhn’s 22 years in the monuments division, 30 sculptures have been installed. I didn’t know if that is a lot or a little; apparently, it’s a little. Kuhn said that for years, NYC Parks has been moving away from sculptures due to factors including maintenance costs.

In other words, it’s not me, it’s them.

I inquired about the possibility of putting a small memorial to Bill inside the Poe Park Visitor Center, but that, too, is under NYC Parks jurisdiction.

I mentioned Milwaukee, where fans raised more than $85,000 for a statue of the Fonz from Happy Days. Thousands turned up for its unveiling.

meeting the Bronze Fonz, 2011

meeting the Bronze Fonz, 2011

I mentioned Detroit, where fans raised more than $56,000 for a statue of Robocop. (Robocop. He doesn’t come close to the iconic status of even Batman’s supporting characters.)

Kuhn said that the NYC Public Design Commission in NYC considers pop culture-related sculptures in other cities to be bad examples of public art. (To be clear, I am not proposing a statue of Batman or even Bill Finger but rather an artistic tribute to Bill Finger.)

More facts I was fascinated to learn about New York and monuments:

they do monuments only for people who are already widely known (“Think Gandhi”)certain people who got a monument then “became a trivia question,” prompting certain other people to request that such monuments be removedthe potential to boost tourism is not a consideration in greenlighting a monumentall park monuments are funded privately and endowed in perpetuityit’s easier to install a monument on private propertyit’s prohibited for monuments to include copyrighted characters (Central Park is home to a statue of Alice in Wonderland, but those characters are public domain)

The first criterion does not resonate with me because there are people whose names are not household but whose accomplishments are known worldwide. (For example, quick—who invented the cell phone? Sneakers? Pizza delivery?) I don’t remember the exact words of Kuhn’s response, but the gist was “Even still…”

Kuhn repeatedly said that New York has been home to many notable people and moments. (I would love to see a list of people who have been proposed and rejected.) More than once he cited singer Rosemary Clooney [aunt of actor George Clooney...who played Batman]. Kuhn said Clooney gave her first concert in Poe Park...and has no monument there.

He meant this as a reason to justify not approving a monument to Bill Finger in the same park, though that also did not resonate with me, for two reasons.

First, the cultural impact of Bill’s creations clearly exceeds the impact of the contributions of some of the “many notable people.” I know Rosemary Clooney was a beloved performer in her day, but today, is her name as well known or her influence as pervasively felt as Batman’s? (I’m not saying she’s a trivia question, but Batman debuted in 1939 and grows more popular with each new generation.)

Second, that fact that many notable people have made history in New York should not factor into any individual decisions. If someone deemed more notable has not been nominated, that should have no bearing on a nomination for Bill—or anyone else. I’m not suggesting “first come, first served.” I’m simply suggesting that each person be evaluated in and of himself, not in contrast to any number of others who could sustain a monument.

This reminds me of a yearly phenomenon regarding the Best Picture Academy Award nominations; there is always an underdog and always at least one “snubbed” film—but that is not the underdog’s fault.

Also, according to the NYC Parks site itself, “Rosemary Clooney is reported [emphasis mine] to have made her public debut at the Poe Park bandstand.” I don’t know how they don’t know for sure if Clooney indeed performed there, but we have multiple published sources for Bill’s connection to the park, including Bill himself.

I feel it is short-sighted for the NYC Parks system to decline Bill Finger in large part because they did not already know who he was. I provided what I objectively feel is substantial evidence why he deserves a memorial in New York—and it should have been enough even if I had just said “He was the main mind behind Batman.” Such a memorial would have deep meaning for many.

As of now, I am pursuing four other options, three in New York, and all of which you’ll read about here before long.

Part 3 (the proposal itself).

The story so far: I proposed installing a memorial to Bill Finger in Poe Park.

What happened next:

Jonathan Kuhn, Director of Art & Antiquities in the NYC Parks department, strikes me as a sharp, candid guy. I’d wager he knows more than anyone else about the history of New York parks (and the history of the history commemorated within them). He has the tone of a man used to fielding the same questions again and again over years—patient with an underlying irritation. Yet he kindly devoted time to me until I better understood the nuances of the parks system policy on installing monuments.

The policy, generally speaking, is this: no.

In Kuhn’s 22 years in the monuments division, 30 sculptures have been installed. I didn’t know if that is a lot or a little; apparently, it’s a little. Kuhn said that for years, NYC Parks has been moving away from sculptures due to factors including maintenance costs.

In other words, it’s not me, it’s them.

I inquired about the possibility of putting a small memorial to Bill inside the Poe Park Visitor Center, but that, too, is under NYC Parks jurisdiction.

I mentioned Milwaukee, where fans raised more than $85,000 for a statue of the Fonz from Happy Days. Thousands turned up for its unveiling.

meeting the Bronze Fonz, 2011

meeting the Bronze Fonz, 2011I mentioned Detroit, where fans raised more than $56,000 for a statue of Robocop. (Robocop. He doesn’t come close to the iconic status of even Batman’s supporting characters.)

Kuhn said that the NYC Public Design Commission in NYC considers pop culture-related sculptures in other cities to be bad examples of public art. (To be clear, I am not proposing a statue of Batman or even Bill Finger but rather an artistic tribute to Bill Finger.)

More facts I was fascinated to learn about New York and monuments:

they do monuments only for people who are already widely known (“Think Gandhi”)certain people who got a monument then “became a trivia question,” prompting certain other people to request that such monuments be removedthe potential to boost tourism is not a consideration in greenlighting a monumentall park monuments are funded privately and endowed in perpetuityit’s easier to install a monument on private propertyit’s prohibited for monuments to include copyrighted characters (Central Park is home to a statue of Alice in Wonderland, but those characters are public domain)

The first criterion does not resonate with me because there are people whose names are not household but whose accomplishments are known worldwide. (For example, quick—who invented the cell phone? Sneakers? Pizza delivery?) I don’t remember the exact words of Kuhn’s response, but the gist was “Even still…”

Kuhn repeatedly said that New York has been home to many notable people and moments. (I would love to see a list of people who have been proposed and rejected.) More than once he cited singer Rosemary Clooney [aunt of actor George Clooney...who played Batman]. Kuhn said Clooney gave her first concert in Poe Park...and has no monument there.

He meant this as a reason to justify not approving a monument to Bill Finger in the same park, though that also did not resonate with me, for two reasons.

First, the cultural impact of Bill’s creations clearly exceeds the impact of the contributions of some of the “many notable people.” I know Rosemary Clooney was a beloved performer in her day, but today, is her name as well known or her influence as pervasively felt as Batman’s? (I’m not saying she’s a trivia question, but Batman debuted in 1939 and grows more popular with each new generation.)

Second, that fact that many notable people have made history in New York should not factor into any individual decisions. If someone deemed more notable has not been nominated, that should have no bearing on a nomination for Bill—or anyone else. I’m not suggesting “first come, first served.” I’m simply suggesting that each person be evaluated in and of himself, not in contrast to any number of others who could sustain a monument.

This reminds me of a yearly phenomenon regarding the Best Picture Academy Award nominations; there is always an underdog and always at least one “snubbed” film—but that is not the underdog’s fault.

Also, according to the NYC Parks site itself, “Rosemary Clooney is reported [emphasis mine] to have made her public debut at the Poe Park bandstand.” I don’t know how they don’t know for sure if Clooney indeed performed there, but we have multiple published sources for Bill’s connection to the park, including Bill himself.

I feel it is short-sighted for the NYC Parks system to decline Bill Finger in large part because they did not already know who he was. I provided what I objectively feel is substantial evidence why he deserves a memorial in New York—and it should have been enough even if I had just said “He was the main mind behind Batman.” Such a memorial would have deep meaning for many.

As of now, I am pursuing four other options, three in New York, and all of which you’ll read about here before long.

Part 3 (the proposal itself).

Published on June 04, 2013 04:00

June 3, 2013

A Bill Finger memorial in Poe Park in the Bronx, part 1 of 3

Though he was the co-creator of one of the most recognizable fictional characters in world history, almost nobody appeared to notice when Bill Finger died. Even, at first, his only known child, son Fred. (Scribbled on the medical examiner report: “No family.”)

During my research about Bill (which began in 2006), almost no one I asked knew what had happened to him after he died. The most anyone thought they knew was that Bill did not have a funeral.

That, sadly, turned out to be true—and he has no gravestone, either.

Yet Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman goes beyond his death for six pages. This is noteworthy for any man, and especially a man who seemingly vanished from Earth with no fanfare.

And the story of Bill’s afterlife is not done yet.

Early in the book’s development I knew that I would propose erecting a memorial in Bill’s honor in the Bronx, where he was living when he mo-created (mostly created) Batman in 1939. I envisioned this specifically in Poe Park, where Bill and Bob brainstormed early Batman stories.

from Bill the Boy Wonder

from Bill the Boy Wonder

I suspected that navigating New York City bureaucracy would be a challenge, but for me, that’s hardly a deterrent.

(My first attempt to commemorate a key Bill locale, the privately owned Greenwich Village apartment building in which he lived for much of the 1940s, was not successful.)

In June 2011, I began chasing my Poe Park memorial dream, aiming for an unveiling in 2014—the 75th anniversary of Batman and what would have been Bill’s 100th birthday.

I started the conversation with the director of the Bronx Tourism Council, then heard nothing for months. In early 2012, a different contact at the BTC reached out. In July 2012, I heard from a third, the NEW director of the BTC, and began again, getting the green light to resubmit a tweaked version of the proposal I’d sent a year before. We exchanged a few emails after that.

(At some point I also checked back with the Bronx Historical Society, whom I’d contacted during my book research; I learned—as I supposed—that they have no governance with respect to memorials.)

It wasn’t until early November 2012 that the director told me she was not in a position to approve this. She suggested I contact Bronx elected officials. This included a senator, an assemblyman, and a councilman. I emailed them, asking for their support. I heard back from none of them.

In February 2013, I was rerouted again, this time to the Poe Park Visitor Center Coordinator. She also fielded my proposal, and she also reported back that she’s not the one with decision-making authority.

She directed me to Jonathan Kuhn, Director of Art & Antiquities in the NYC Parks department. He was the person I should have been in touch with all along.

His response: let’s talk.

It’s my nature to read positively into such short, cryptic suggestions. My nature, however, is flawed.

Part 2.

During my research about Bill (which began in 2006), almost no one I asked knew what had happened to him after he died. The most anyone thought they knew was that Bill did not have a funeral.

That, sadly, turned out to be true—and he has no gravestone, either.

Yet Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman goes beyond his death for six pages. This is noteworthy for any man, and especially a man who seemingly vanished from Earth with no fanfare.

And the story of Bill’s afterlife is not done yet.

Early in the book’s development I knew that I would propose erecting a memorial in Bill’s honor in the Bronx, where he was living when he mo-created (mostly created) Batman in 1939. I envisioned this specifically in Poe Park, where Bill and Bob brainstormed early Batman stories.

from Bill the Boy Wonder

from Bill the Boy WonderI suspected that navigating New York City bureaucracy would be a challenge, but for me, that’s hardly a deterrent.

(My first attempt to commemorate a key Bill locale, the privately owned Greenwich Village apartment building in which he lived for much of the 1940s, was not successful.)

In June 2011, I began chasing my Poe Park memorial dream, aiming for an unveiling in 2014—the 75th anniversary of Batman and what would have been Bill’s 100th birthday.

I started the conversation with the director of the Bronx Tourism Council, then heard nothing for months. In early 2012, a different contact at the BTC reached out. In July 2012, I heard from a third, the NEW director of the BTC, and began again, getting the green light to resubmit a tweaked version of the proposal I’d sent a year before. We exchanged a few emails after that.

(At some point I also checked back with the Bronx Historical Society, whom I’d contacted during my book research; I learned—as I supposed—that they have no governance with respect to memorials.)

It wasn’t until early November 2012 that the director told me she was not in a position to approve this. She suggested I contact Bronx elected officials. This included a senator, an assemblyman, and a councilman. I emailed them, asking for their support. I heard back from none of them.

In February 2013, I was rerouted again, this time to the Poe Park Visitor Center Coordinator. She also fielded my proposal, and she also reported back that she’s not the one with decision-making authority.

She directed me to Jonathan Kuhn, Director of Art & Antiquities in the NYC Parks department. He was the person I should have been in touch with all along.

His response: let’s talk.

It’s my nature to read positively into such short, cryptic suggestions. My nature, however, is flawed.

Part 2.

Published on June 03, 2013 04:00

June 1, 2013

How to do an author's pic

The only “about the author” blurb of mine that was accompanied by a drawing rather than a photo was in my 2006 book How to Do a Belly Flop.

Don’t believe those other two names on the cover. They didn’t write any of this book; they wrote the previous and their names were added to link the two books.

Favorite entry: how to have a snowball fight...in July.

Don’t believe those other two names on the cover. They didn’t write any of this book; they wrote the previous and their names were added to link the two books.

Favorite entry: how to have a snowball fight...in July.

Published on June 01, 2013 04:00

May 31, 2013

International Reading Association 2013: nonfiction lives!

That “lives” could be a verb or a noun; we discussed both.

Me, two other cowboys, and two fine cowgirls (AKA Brian Floca, Chris Barton, Meghan McCarthy, and Shana Corey) moseyed on down old San Antonio way for IRA, where we did a panel called “‘But Kids Haven’t Heard of That!’: Why Teaching Unconventional Nonfiction Is Important.”

Moderated by the tireless Susannah Richards, Associate Professor of Education at Eastern Connecticut State University, each of the five authors did a fifteen-minute presentation, then collectively took questions from Susannah and the audience.

I was as much an avid audience member as a participant. Adding to my excitement was the fact that I’d proposed the panel—twice actually (it was rejected for 2012)—stocking it with four of my favorite nonfiction picture book writers, not to mention friends.

Brian Floca, Meghan McCarthy, me, Shana Corey, Chris Barton

Brian Floca, Meghan McCarthy, me, Shana Corey, Chris Barton

Here is feedback on the proposal from IRA decision-makers:

The panel of authors should draw a big audience.Appropriate subject matter for this symposia. The panelists are authors and have significant information to share with the audience.This proposal presents a clear evidence base and also is convincing and motivating. The content was detailed and gives a clear idea of what will transpire in the session. The objectives align with the content. This is an excellent proposal.

Here is feedback on the panel from an attendee:

Panel’s-eye views:

After, as we unwound at the River Walk, another author ally, Erica Perl, joined us. I, however, was the only one who wanted homemade ice cream.

For diehards and readhards, here is the meat of the proposal:

Educational Significance

For some students, nonfiction has a stigma: boring. This is perplexing: why would a true story inherently be less intriguing than something made up? In years past, nonfiction was often written in a dry manner. In addition, there was less risk in subject matter and style.

Today, however, the authors writing nonfiction for young people recognize the dual responsibility they have. First, they must continue to present accurate (and, when possible, new) information. And now, they must do so in an engaging fashion. The marked shift from “textbook” to narrative nonfiction is a considerable benefit for young readers.

In exercising creative freedom with respect to tone, chronology, perspective, and subject matter, contemporary nonfiction writers are boosting the excitement of teachers and kids alike. Such fresh material lures reluctant readers and further stimulates active readers.

We’ve seen an increase in nonfiction picture books described as a “first of its kind.” We’ve seen an increase in picture books subjects that have never been the focus of even a book for adults (The Day-Glo Brothers, Strong Man, Surfer of the Century, Boys of Steel). We’ve seen a rise in the level of sophistication of—and the amount of pages devoted to – back matter. The reason: there is an audience and an educational missive to support it.

Yet with library budgets in crisis, it can be difficult to get unconventional nonfiction into schools—and with test preparation time increasing, educators may struggle to make time to introduce it. In our increasingly blended world, however, it is critical to re-emphasize a diversity of subject matter. (No slight to Benjamin Franklin, Muhammad Ali, Babe Ruth, or the Obamas’ dog, each of whom has starred in multiple picture books.)

This panel may include but is not solely about multicultural subjects. Rather it focuses more broadly on subjects generally not taught in curriculum.

2012 IRA attendee feedback:

Very appropriate subject matter! Nonfiction needs to be addressed, especially with Common Core being the focus!Informational text deserves greater attention, especially unconventional informational text. The panel format will be appealing to the audience. The panelists have valuable information to share. The topic is grounded in literature that is relevant and substantial. I believe this session will be of interest to a broad cross-section of IRA members.

Evidence Base

Forty-five states have adopted the Common Core Standards.

Publishers Weekly (7/18/12): “By the 2014-15 academic year, the initiative calls for 50% informational text (including…nonfiction trade books) in elementary school and 70% in high school-on average, across all curricula. … [A]ccording to the Core: dull-looking nonfiction is out. … ‘Visual elements are particularly important in texts for the youngest students and in many informational texts for readers of all ages.’”

New York Times (3/11/12): “Children in New York City who learned to read using an experimental curriculum that emphasized nonfiction texts outperformed those at other schools.”

School Library Journal (4/1/12): “‘The advent of Common Core presents school librarians with both a great opportunity and a great challenge,’ says kids’ book editor and author Marc Aronson. ‘The emphasis on nonfiction from elementary school on puts them front and center, since few current homeroom teachers know nonfiction in their grades as read-alouds, as pleasure reads, or as opportunities to compare different narrative approaches.”

Horn Book (March-April 2011): Author Susan Campbell Bartoletti writes that in her teaching experience, fiction-reading kids would hold up a favorite book and ask for another like it. But nonfiction readers “wanted to read [books] about things they didn’t already know.”

Jim Trelease, author of The Read-Aloud Handbook, stated that an unconventional nonfiction “panel is a super idea and one that will draw a top audience.”

Increasingly, picture book nonfiction includes an author’s note about the author’s research process—a process that every student must learn in English class. And the best of these authors’ notes read like detective novels.

Sites such as teachwithpicturebooks.blogspot.com promote picture books in the classroom—even in middle and high school. Neither “short” nor “illustrated” automatically makes a book only for young people.

Reading nonfiction capitalizes on existing interests and generates motivation. Reading unconventional nonfiction challenges perspectives and brings fuller, often cross-disciplinary understanding to any historical period.

Reading nonfiction helps to build schema and vocabulary knowledge. Reading unconventional nonfiction empowers students to experiment with topics they may not presume to like or understand, and often enlightens them when they can make a connection between that material and curriculum.

- end of proposal excerpt -

Oh, and circling back to the cowboy theme: the last morning, I was almost trampled by a stampede…of teachers and librarians…headed to a booth for a free bag featuring Superman on one side and (for them) the bigger draw, Wonder Woman, on the other.

Me, two other cowboys, and two fine cowgirls (AKA Brian Floca, Chris Barton, Meghan McCarthy, and Shana Corey) moseyed on down old San Antonio way for IRA, where we did a panel called “‘But Kids Haven’t Heard of That!’: Why Teaching Unconventional Nonfiction Is Important.”

Moderated by the tireless Susannah Richards, Associate Professor of Education at Eastern Connecticut State University, each of the five authors did a fifteen-minute presentation, then collectively took questions from Susannah and the audience.

I was as much an avid audience member as a participant. Adding to my excitement was the fact that I’d proposed the panel—twice actually (it was rejected for 2012)—stocking it with four of my favorite nonfiction picture book writers, not to mention friends.

Brian Floca, Meghan McCarthy, me, Shana Corey, Chris Barton

Brian Floca, Meghan McCarthy, me, Shana Corey, Chris Barton Here is feedback on the proposal from IRA decision-makers:

The panel of authors should draw a big audience.Appropriate subject matter for this symposia. The panelists are authors and have significant information to share with the audience.This proposal presents a clear evidence base and also is convincing and motivating. The content was detailed and gives a clear idea of what will transpire in the session. The objectives align with the content. This is an excellent proposal.

Here is feedback on the panel from an attendee:

I attended a panel meeting of nonfiction authors. One author in particular, Marc Tyler Nobleman, stuck out to me. … Mr. Nobleman’s book [Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman] is a must read. [He] is an excellent storyteller; it’s just, he’s not telling you a story—he’s telling you facts. I have never seen nonfiction this cool and interesting before now.

Panel’s-eye views:

After, as we unwound at the River Walk, another author ally, Erica Perl, joined us. I, however, was the only one who wanted homemade ice cream.

For diehards and readhards, here is the meat of the proposal:

Educational Significance

For some students, nonfiction has a stigma: boring. This is perplexing: why would a true story inherently be less intriguing than something made up? In years past, nonfiction was often written in a dry manner. In addition, there was less risk in subject matter and style.

Today, however, the authors writing nonfiction for young people recognize the dual responsibility they have. First, they must continue to present accurate (and, when possible, new) information. And now, they must do so in an engaging fashion. The marked shift from “textbook” to narrative nonfiction is a considerable benefit for young readers.

In exercising creative freedom with respect to tone, chronology, perspective, and subject matter, contemporary nonfiction writers are boosting the excitement of teachers and kids alike. Such fresh material lures reluctant readers and further stimulates active readers.

We’ve seen an increase in nonfiction picture books described as a “first of its kind.” We’ve seen an increase in picture books subjects that have never been the focus of even a book for adults (The Day-Glo Brothers, Strong Man, Surfer of the Century, Boys of Steel). We’ve seen a rise in the level of sophistication of—and the amount of pages devoted to – back matter. The reason: there is an audience and an educational missive to support it.

Yet with library budgets in crisis, it can be difficult to get unconventional nonfiction into schools—and with test preparation time increasing, educators may struggle to make time to introduce it. In our increasingly blended world, however, it is critical to re-emphasize a diversity of subject matter. (No slight to Benjamin Franklin, Muhammad Ali, Babe Ruth, or the Obamas’ dog, each of whom has starred in multiple picture books.)

This panel may include but is not solely about multicultural subjects. Rather it focuses more broadly on subjects generally not taught in curriculum.

2012 IRA attendee feedback:

Very appropriate subject matter! Nonfiction needs to be addressed, especially with Common Core being the focus!Informational text deserves greater attention, especially unconventional informational text. The panel format will be appealing to the audience. The panelists have valuable information to share. The topic is grounded in literature that is relevant and substantial. I believe this session will be of interest to a broad cross-section of IRA members.

Evidence Base

Forty-five states have adopted the Common Core Standards.

Publishers Weekly (7/18/12): “By the 2014-15 academic year, the initiative calls for 50% informational text (including…nonfiction trade books) in elementary school and 70% in high school-on average, across all curricula. … [A]ccording to the Core: dull-looking nonfiction is out. … ‘Visual elements are particularly important in texts for the youngest students and in many informational texts for readers of all ages.’”

New York Times (3/11/12): “Children in New York City who learned to read using an experimental curriculum that emphasized nonfiction texts outperformed those at other schools.”

School Library Journal (4/1/12): “‘The advent of Common Core presents school librarians with both a great opportunity and a great challenge,’ says kids’ book editor and author Marc Aronson. ‘The emphasis on nonfiction from elementary school on puts them front and center, since few current homeroom teachers know nonfiction in their grades as read-alouds, as pleasure reads, or as opportunities to compare different narrative approaches.”

Horn Book (March-April 2011): Author Susan Campbell Bartoletti writes that in her teaching experience, fiction-reading kids would hold up a favorite book and ask for another like it. But nonfiction readers “wanted to read [books] about things they didn’t already know.”

Jim Trelease, author of The Read-Aloud Handbook, stated that an unconventional nonfiction “panel is a super idea and one that will draw a top audience.”

Increasingly, picture book nonfiction includes an author’s note about the author’s research process—a process that every student must learn in English class. And the best of these authors’ notes read like detective novels.

Sites such as teachwithpicturebooks.blogspot.com promote picture books in the classroom—even in middle and high school. Neither “short” nor “illustrated” automatically makes a book only for young people.

Reading nonfiction capitalizes on existing interests and generates motivation. Reading unconventional nonfiction challenges perspectives and brings fuller, often cross-disciplinary understanding to any historical period.

Reading nonfiction helps to build schema and vocabulary knowledge. Reading unconventional nonfiction empowers students to experiment with topics they may not presume to like or understand, and often enlightens them when they can make a connection between that material and curriculum.

- end of proposal excerpt -

Oh, and circling back to the cowboy theme: the last morning, I was almost trampled by a stampede…of teachers and librarians…headed to a booth for a free bag featuring Superman on one side and (for them) the bigger draw, Wonder Woman, on the other.

Published on May 31, 2013 04:00

May 30, 2013

Cartoons for "Publishers Weekly"

BookExpo America opens today.

At BEA eleven years ago, my cartoons appeared in the Publishers Weekly Show Daily.

At BEA eleven years ago, my cartoons appeared in the Publishers Weekly Show Daily.

Published on May 30, 2013 04:00

May 25, 2013

A clever thank you from a Rhode Island school

As often is the case, I find myself thanking for a thank you. Thank you, Cluny School of Newport!

The Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman source page:

The Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman source page:

Published on May 25, 2013 04:00