Marc Tyler Nobleman's Blog, page 108

May 6, 2013

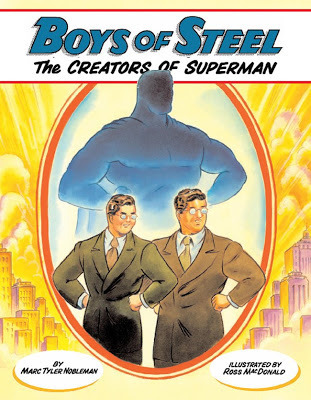

Rules I broke in “Boys of Steel: The Creators of Superman”

Superman is the ultimate law-abider. So it’s borderline traitorous for me to write a book about him that breaks some of the “rules.” Luckily, none go so far as to be criminal.

broken rule #1—Do not write nonfiction picture books on pop culture figures.

At first this may seem invalid because plenty of others have also broken this rule (and, for that matter, all of the other rules I’ll list). Yet this still comes up. It’s a commentary on commerce, not content. There can be editorial resistance to historic figures who are not part of traditional curriculum. Teachers are pressured to stick to material that will come up on tests; anything else can be perceived as a waste of time. Therefore, some editors worry that this situation will doom sales for a book on an unconventional topic. I am happy to report that the fact that Superman and his creators, writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster, are typically not covered in social studies has not hindered classroom use of Boys of Steel. In fact, the book has multiple applications to curriculum, even if the Man (or Boys) of Steel will not be on the test.

broken rule #2—Do not write picture books about writers.

It does seem that a book featuring illustration after illustration of a person sitting at a desk would quickly become visually boring. But writers do far more than sit at desks. In writing any book there are challenges, and in writing any picture book there are additional challenges, and one of them is varying your images no matter what the subject. Boys of Steel contains only one image of Jerry at his typewriter. The rest is other kinds of adventure.

broken rule #3—Do not use dialogue in nonfiction picture books.

I’ve already written on this, but the recap is as follows: if you treat it like any other fact and source it appropriately, why not? In Boys of Steel, I include statements the Boys made in interviews but present it as dialogue. It livens up the text as dialogue tends to do, and it brings the reader closer to the protagonists. Yes, the lines of dialogue may have occurred at different times in real life than when they appear in the book, but this is a convention we regularly accept in nonfiction. No nonfiction is “pure” nonfiction—not even autobiography.

broken rule #4—With biographies, start with birth, end with death…or at least mention birth and death.

We are living in the Golden Age of Picture Book Biography, which allows writers unparalleled freedom in how we tell our true stories. Everything in the book must be factual, but not every fact must (or even can be) in the book. We need not present our tellings chronologically or wholly. Sometimes the birth and/or death of a figure are simply not essential details in our approach. (To the subjects, they were, of course, notable milestones.) I start Boys of Steel in roughly 1930, when Jerry and Joe met, and end it in roughly 1940, soon after Superman’s stratospheric rise. (In the author’s note, I do briefly address the rest of their lives.)

broken rule #5—Refer to your main character by name.

Perhaps this is not quite a rule, but it certainly is the standard. Not counting the subtitle and author’s note, Boys of Steel contains the word “Superman” precisely zero times. This was not because I was hindered by copyright/trademark restriction or because I made an oversight. This was simply because I could. In my structure, the Boys create Superman toward the end of the story proper, which means I got pretty far without using the word; it then became a fun challenge to see if I could get to the end without it. Readers come away thinking I’ve used the word, but they are extracting that thought from images alone.

broken rule #6—Have a happy ending.

Real life sometimes doesn’t, so books about real life sometimes can’t. Kids can handle the truth (relative to their age, of course). It does no favors to sugarcoat—or omit—certain tragedies. Every biography addresses struggles the protagonist faced en route to success, so why can’t the book end on a struggle? The illustrated portion of Boys of Steel does end on a high note, but the author’s note reveals that the Boys went on to face considerable suffering. Learning about injustice or misfortune or other unpleasantries may sound depressing, but often it is empowering. It can get kids fired up to help prevent similar situations in their own lives and to go do good in the world.

These are the kinds of rules even Superman would condone breaking.

broken rule #1—Do not write nonfiction picture books on pop culture figures.

At first this may seem invalid because plenty of others have also broken this rule (and, for that matter, all of the other rules I’ll list). Yet this still comes up. It’s a commentary on commerce, not content. There can be editorial resistance to historic figures who are not part of traditional curriculum. Teachers are pressured to stick to material that will come up on tests; anything else can be perceived as a waste of time. Therefore, some editors worry that this situation will doom sales for a book on an unconventional topic. I am happy to report that the fact that Superman and his creators, writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster, are typically not covered in social studies has not hindered classroom use of Boys of Steel. In fact, the book has multiple applications to curriculum, even if the Man (or Boys) of Steel will not be on the test.

broken rule #2—Do not write picture books about writers.

It does seem that a book featuring illustration after illustration of a person sitting at a desk would quickly become visually boring. But writers do far more than sit at desks. In writing any book there are challenges, and in writing any picture book there are additional challenges, and one of them is varying your images no matter what the subject. Boys of Steel contains only one image of Jerry at his typewriter. The rest is other kinds of adventure.

broken rule #3—Do not use dialogue in nonfiction picture books.

I’ve already written on this, but the recap is as follows: if you treat it like any other fact and source it appropriately, why not? In Boys of Steel, I include statements the Boys made in interviews but present it as dialogue. It livens up the text as dialogue tends to do, and it brings the reader closer to the protagonists. Yes, the lines of dialogue may have occurred at different times in real life than when they appear in the book, but this is a convention we regularly accept in nonfiction. No nonfiction is “pure” nonfiction—not even autobiography.

broken rule #4—With biographies, start with birth, end with death…or at least mention birth and death.

We are living in the Golden Age of Picture Book Biography, which allows writers unparalleled freedom in how we tell our true stories. Everything in the book must be factual, but not every fact must (or even can be) in the book. We need not present our tellings chronologically or wholly. Sometimes the birth and/or death of a figure are simply not essential details in our approach. (To the subjects, they were, of course, notable milestones.) I start Boys of Steel in roughly 1930, when Jerry and Joe met, and end it in roughly 1940, soon after Superman’s stratospheric rise. (In the author’s note, I do briefly address the rest of their lives.)

broken rule #5—Refer to your main character by name.

Perhaps this is not quite a rule, but it certainly is the standard. Not counting the subtitle and author’s note, Boys of Steel contains the word “Superman” precisely zero times. This was not because I was hindered by copyright/trademark restriction or because I made an oversight. This was simply because I could. In my structure, the Boys create Superman toward the end of the story proper, which means I got pretty far without using the word; it then became a fun challenge to see if I could get to the end without it. Readers come away thinking I’ve used the word, but they are extracting that thought from images alone.

broken rule #6—Have a happy ending.

Real life sometimes doesn’t, so books about real life sometimes can’t. Kids can handle the truth (relative to their age, of course). It does no favors to sugarcoat—or omit—certain tragedies. Every biography addresses struggles the protagonist faced en route to success, so why can’t the book end on a struggle? The illustrated portion of Boys of Steel does end on a high note, but the author’s note reveals that the Boys went on to face considerable suffering. Learning about injustice or misfortune or other unpleasantries may sound depressing, but often it is empowering. It can get kids fired up to help prevent similar situations in their own lives and to go do good in the world.

These are the kinds of rules even Superman would condone breaking.

Published on May 06, 2013 04:00

May 5, 2013

National Cartoonists Society

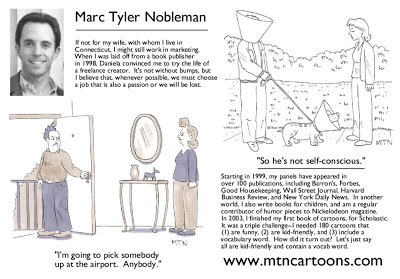

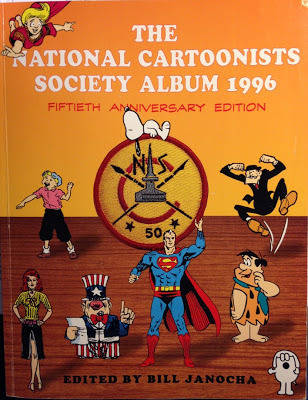

In 1999, the way I partied like it was, well, that year was by joining the National Cartoonists Society.

This entitled me to a copy of the NCS membership album from 1996—the 50th anniversary edition.

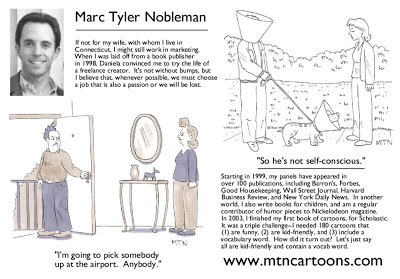

It also entitled me to an entry in the next edition. Rather than copy and submit my high school yearbook entry, I cobbled together something new:

That site is defunct but the cartoons live on.

Happy National Cartoonists Day. You are convincing in your act that you did not already know it was today.

This entitled me to a copy of the NCS membership album from 1996—the 50th anniversary edition.

It also entitled me to an entry in the next edition. Rather than copy and submit my high school yearbook entry, I cobbled together something new:

That site is defunct but the cartoons live on.

Happy National Cartoonists Day. You are convincing in your act that you did not already know it was today.

Published on May 05, 2013 04:00

May 4, 2013

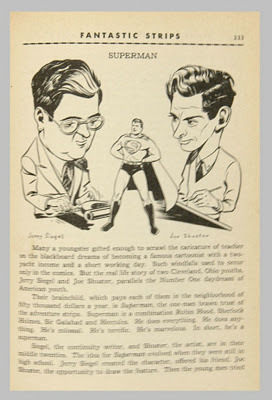

Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster are not heroes

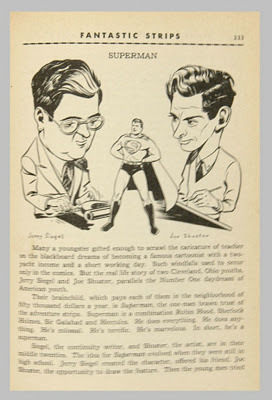

Some reviews of Boys of Steel: The Creators of Superman called writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster heroes. These guys created arguably the most iconic superhero of the 20th century. But does that make them heroic?

I feel the word “hero” is overused. This dilutes its potency. The more people we call heroes, the less impact the word has.

It is a natural transference to refer to superhero creators as heroes themselves, but that is a disservice both to more traditionally defined heroes (firefighters, police officers, rescue workers, everyday people who surprise even themselves by risking their own lives to try to save another) and to the creators themselves.

True, dreaming up a character who becomes an industry unto himself is something few have done; there are fewer such creators than heroes. So there is certainly prestige and distinction in it. But that doesn’t mean there is bravery and selflessness in it. Superhero creators deserve praise, but to call them heroes for their visions is giving them the wrong kind of praise...or praise for the wrong aspect. (More on this in a moment.)

Another word tossed around too liberally is “genius.” Were Jerry and Joe creative geniuses? I consider “genius” a classification that can be measured, and I don’t believe you can measure artistic ability. It’s subjective. So if you ask me, not only were Jerry and Joe not heroes, but also not geniuses.

So what were they? They were creative for sure. Innovative. Risk-taking. Persistent.

And it is in this last regard that they came closest to being, yes, heroic.

Their cultural contribution was undeniably seismic, but it was their blind determination to see their idea through despite three and a half years of rejection that shows just how strong they were. (The book is called Boys of Steel for a reason.) They endured nos ranging from the unembellished to the borderline cruel. Yet none of that stopped them, because they were convinced they had a good idea.

Then after they sold all rights to Superman for $130, they went through 35 years of hardship trying to get them back. They genuinely believed it was their right to do so. They were the underdogs. They were demoralized, ignored, insulted—yet they were not deterred from their goal.

To me, that is heroic. Your ideas may be peerless but it’s your actions that determine your hero status.

I feel the word “hero” is overused. This dilutes its potency. The more people we call heroes, the less impact the word has.

It is a natural transference to refer to superhero creators as heroes themselves, but that is a disservice both to more traditionally defined heroes (firefighters, police officers, rescue workers, everyday people who surprise even themselves by risking their own lives to try to save another) and to the creators themselves.

True, dreaming up a character who becomes an industry unto himself is something few have done; there are fewer such creators than heroes. So there is certainly prestige and distinction in it. But that doesn’t mean there is bravery and selflessness in it. Superhero creators deserve praise, but to call them heroes for their visions is giving them the wrong kind of praise...or praise for the wrong aspect. (More on this in a moment.)

Another word tossed around too liberally is “genius.” Were Jerry and Joe creative geniuses? I consider “genius” a classification that can be measured, and I don’t believe you can measure artistic ability. It’s subjective. So if you ask me, not only were Jerry and Joe not heroes, but also not geniuses.

So what were they? They were creative for sure. Innovative. Risk-taking. Persistent.

And it is in this last regard that they came closest to being, yes, heroic.

Their cultural contribution was undeniably seismic, but it was their blind determination to see their idea through despite three and a half years of rejection that shows just how strong they were. (The book is called Boys of Steel for a reason.) They endured nos ranging from the unembellished to the borderline cruel. Yet none of that stopped them, because they were convinced they had a good idea.

Then after they sold all rights to Superman for $130, they went through 35 years of hardship trying to get them back. They genuinely believed it was their right to do so. They were the underdogs. They were demoralized, ignored, insulted—yet they were not deterred from their goal.

To me, that is heroic. Your ideas may be peerless but it’s your actions that determine your hero status.

Published on May 04, 2013 04:00

April 30, 2013

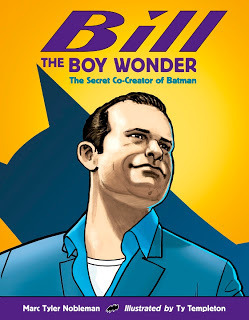

“Bill the Boy Wonder” secrets revealed!

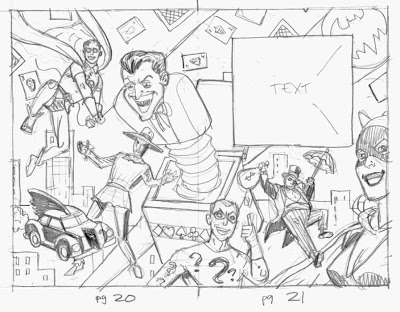

Soon after Boys of Steel: The Creators of Superman came out in 2008, I posted what I called a “tour” of the book, pointing out details, tricks, and other Easter eggs that even astute readers might otherwise miss.

Here is the tour for Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman.

As is typical for contemporary picture books, the pages aren’t numbered. (Publishers fear that could turn off readers by calling attention to their relatively short length.) So I’ll reference pages by their first few words.

Get your copy of the book and follow along...

“Every Batman story…” (inside front cover)

backstory – I originally envisioned this text (both white and yellow) as a teaser/cold open on the page before the title page. It’s still before the title page…

“After Milton Finger graduated…”

design – This image is a (rotated) close-up of the scene on the title page. See little Bill?

never-published information – Bill’s given name was Milton; Bill graduated high school in 1933.

design – I wanted the three “secret identity” starbursts throughout the book to be consistent in color scheme (happened) and size (did not).

backstory – The “first secret identity” line was intended to be a hook. People reading a book about a superhero would not be surprised to see mention of a secret identity (singular)…but it would be unusual for someone to have more than one.

“Bill loved literature…”

design – Throughout the book, Ty depicts Bill in blue and Bob in yellow. Bill liked to wear blue Oxford shirts. And the yellow stands for…

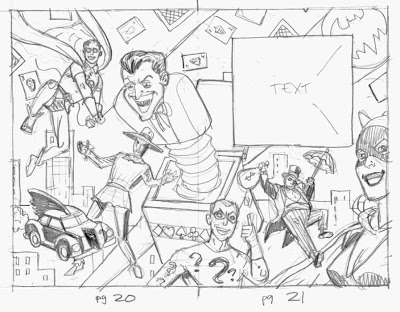

“That weekend he sketched…”

design – I love the scene in the first panel but felt the apartment looked too grand for a young artist in New York. I was (peaceably) overruled. Similarly, I felt the sidewalk in the second panel was too wide, but creative license won that one. In early drafts of the manuscript, I described the look of Bob’s character and first gave the name “Bat-Man” in the text, but once I started to lay out the book in my mind, I saw that these reveals would have a more striking impact if instead we showed them in the art.

“Wings aside…”

design – We deliberately showed only parts of Batman rather than the whole for two reasons. First, delayed gratification: the later it comes, the greater the effect. Two, we had to be selective about showing characters owned by DC Comics: the fewer, the better.

attention to detail – That bat is a reproduction of how the drawing really looked in the 1937 Webster’s Dictionary, which would’ve been the most current edition when Bill and Bob were building Batman in 1939. (The fish, a bass, is also authentic.)

“In April 1939…”

attention to detail – The image is based on a period photo of a newsstand. The comic covers are ones that would have been on the newsstand at approximately the same time as Detective Comics #27 (Batman’s debut). This is the first “full” appearance of Batman in the book, though I consider it too small to count.

“Bill and Bob would sit in Poe Park…”

attention to detail – This setting is based on period photographs of Poe Park.

“Though Bill had wanted Bat-Man…”

design – The sentence starting “Bat-Man became Batman…” makes sense in print, but requires elaboration/clarification when read aloud.

design – This marks the second appearance of Batman, though only his head on a comic book cover. Still no big splash.

“Almost immediately Bob hired…”

attention to detail – Those two guys standing in the background are Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, who were friends with Bill Finger and Jerry Robinson (seated).

design – This is an example of taking advantage of the medium of picture books. The fact that Bill and Jerry played darts is not significant to the larger story, but it is visually interesting so it became the setting for the information conveyed in the accompanying text. Otherwise it could’ve been another scene of guys at a desk.

“But Bill stuck…”

attention to detail – The phrase “superstitious, cowardly hearts of criminals” is a nod to Detective Comics #33, which first presents the origin of Batman and in which Bruce Wayne says “Criminals are a superstitious, cowardly lot. So my disguise must be able to strike terror into their hearts.”

backstory – No gun is visible on purpose, though the threat is still evident.

“Steadily, silently, Bill built…”

attention to detail – In the first sketches, Batman did not appear in this scene because the text is about Batman’s sidekick and villains.

However, in layout, I realized that we had not yet shown a whole, sizable Batman so I asked that we add him; as noted above, Batman does appear on a comic cover in two previous scenes, but in both cases, he is so miniscule that some readers may overlook him. And if kids got to this spread showing Batman’s supporting cast but still had not seen a “big” Batman, they would feel that it was either lame or an oversight.

attention to detail – At first glance most will presume that the title of the book comes from the familiar phrase “Robin the Boy Wonder,” and that is a good thing, but on this page a more literal inspiration for the title manifests itself. It is in Bob’s 1989 autobiography where he said he referred to Bill as “boy wonder.” He, too, was not oblivious to the Robin association, even if he did indeed call Bill this back at the beginning of Batman.

“Other comics creators…”

attention to detail – When I first saw the sketch in which both the Empire State and Chrysler Buildings are visible, I said I didn’t think that there was a ground-level vantage point (even with the lower skyline of the 1940s, when this scene took place) from which such a view existed. Upon seeing images like the one below and thereby learning I was wrong, we situated the scene on East 30th Street in an attempt at authenticity.

backstory – I did not want the inset showing Bill shaking an editor’s hand, for two reasons. One, we already had a handshake image (Kane and editor Vin Sullivan) and I felt including a second one would dilute the (tragic) significance of the first. Two, I doubt it happened. I would guess that an editor simply called Bill to ask for a story, and it was as unceremonious as that. I was overruled, and it was okay.

attention to detail – The gimmick book examples came from published sources and the astounding memory of Charles Sinclair.

“In 1948 Bill and his wife…”

never-published information – Bill nicknamed his son Fred “Little Finger.”

attention to detail – The ticket window is based on several period photographs.

design – Originally, the text specified the way Bill snuck Fred into the museum, but after we began discussing art, it became clear to me that it would be more fun to portray the trick solely in the art.

“While his son…”

backstory – The quotation “I’d like to return to the innocence of my childhood” was not essential, but I included it because it comes from the only known instance of Bill being mentioned/quoted in a mainstream publication (The New Yorker, 1965) in his lifetime.

“Bill was fond of writing…”

attention to detail – The size of the plug seems disproportionately small compared to the size of the fork and plate, but we’d already gone through several sketches to get the trajectory of Batman popping out of the toaster seem plausible (ha) so the size concern was one I had to let go.

attention to detail – If I had not caught that the absence of Batman on the earlier spread featuring the supporting characters/villains would seem like a goof, this would have been the first full-on appearance of Batman in the book.

“To get his stories…”

attention to detail – This desk scene is, unbelievably, perhaps, based on a 1940s photograph of Bill’s workspace. Yes, I went from being told only two photos of Bill exist to having not only 11 photos but also one of his writing desk.

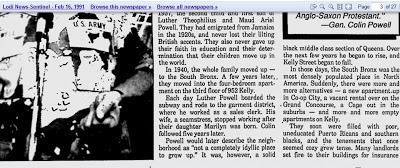

attention to detail – That unassuming little paperweight is not just an illustrator flourish.

“During the first twenty-five years…”

attention to detail – Here is the page from the 1943 story in which Bill’s name appears…sort of. Look carefully...

“In 1964 that changed…”

backstory – Ty Templeton made up the blue-armored figure partially visible behind Julie Schwartz. I did not know this until after the book came out. I would have pushed for a glimpse of a known character, but I understand Ty wanting to limit potential intellectual property claims.

“The next summer…”

backstory – I wanted either Bill to be wearing a tie or one other panelist not to be because I felt Bill could come off as schlubby if he were the only one that casual. I was overruled.

“Jerry also did his own…”

attention to detail – The print over Bill’s desk…was a print over Bill’s desk. Thanks (again) to Charles Sinclair for injecting even more accuracy.

attention to detail – The image of “If the Truth Be Known…” looks that way because this scene takes place in 1965, a time when photocopies did not exist but mimeographs (in all their smudgy purple glory) did.

“Bill’s final Batman…”

never-published information – Bill’s death date (previously reported as January 24). design – “Come Monday” deliberately repeats a construct I used for the first historic “Batman weekend” (1939).

“Now grown…”

never-published information – Bill was cremated; Fred spread his ashes on an (Oregon) beach in an apropos shape. (No spoilers here. You have to see it for yourself.)

“In Bob’s later years…”

design – I did not think we needed the “Bob Kane” credit box there to identify him, and in fact worried it might be confusing, but was overruled.

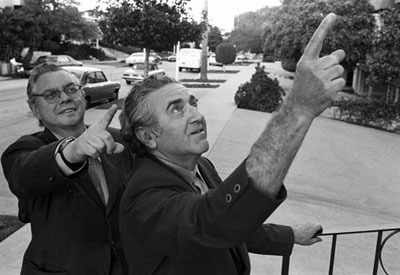

“Jerry Robinson had long wanted…”

attention to detail – This image is based on a photograph of Jerry’s home office. I asked for the TV to show a still from the credits of the 1960s TV Batman show, though it’s been “modified to fit the screen.”

“It was named…”

attention to detail – That’s Jerry again, with Mark Evanier. We sought permission to include the Comic-Con imagery.

“From Milton to Bill…”

backstory – I normally don’t like posing questions in my text, but could not resist the penultimate line.

copy of guestbook (last page)

never-published information – Through a fluke both sad and fortunate, this remnant of Bill still exists.

“Bill was the greatest…” (inside back cover)

backstory – Two of these three quotations were not my original suggestions. I had used a quotation from Lyn Simmons, Bill’s second wife, and another by another associate of Bill’s, but neither of them appear in the story proper and my editor, Alyssa Mito Pusey, felt it would be better to quote characters the reader already knew. I was hesitant at first but came to see her point…and am so glad I did. I love it this way.

I love it all this way.

Thank you, Alyssa, Ty, Martha, and the veritable flash mob of others whose knowledge and talent combined to make this a book about which I am overflowing with pride.

More Bill Finger secrets abound, if you know where to look...

Here is the tour for Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman.

As is typical for contemporary picture books, the pages aren’t numbered. (Publishers fear that could turn off readers by calling attention to their relatively short length.) So I’ll reference pages by their first few words.

Get your copy of the book and follow along...

“Every Batman story…” (inside front cover)

backstory – I originally envisioned this text (both white and yellow) as a teaser/cold open on the page before the title page. It’s still before the title page…

“After Milton Finger graduated…”

design – This image is a (rotated) close-up of the scene on the title page. See little Bill?

never-published information – Bill’s given name was Milton; Bill graduated high school in 1933.

design – I wanted the three “secret identity” starbursts throughout the book to be consistent in color scheme (happened) and size (did not).

backstory – The “first secret identity” line was intended to be a hook. People reading a book about a superhero would not be surprised to see mention of a secret identity (singular)…but it would be unusual for someone to have more than one.

“Bill loved literature…”

design – Throughout the book, Ty depicts Bill in blue and Bob in yellow. Bill liked to wear blue Oxford shirts. And the yellow stands for…

“That weekend he sketched…”

design – I love the scene in the first panel but felt the apartment looked too grand for a young artist in New York. I was (peaceably) overruled. Similarly, I felt the sidewalk in the second panel was too wide, but creative license won that one. In early drafts of the manuscript, I described the look of Bob’s character and first gave the name “Bat-Man” in the text, but once I started to lay out the book in my mind, I saw that these reveals would have a more striking impact if instead we showed them in the art.

“Wings aside…”

design – We deliberately showed only parts of Batman rather than the whole for two reasons. First, delayed gratification: the later it comes, the greater the effect. Two, we had to be selective about showing characters owned by DC Comics: the fewer, the better.

attention to detail – That bat is a reproduction of how the drawing really looked in the 1937 Webster’s Dictionary, which would’ve been the most current edition when Bill and Bob were building Batman in 1939. (The fish, a bass, is also authentic.)

“In April 1939…”

attention to detail – The image is based on a period photo of a newsstand. The comic covers are ones that would have been on the newsstand at approximately the same time as Detective Comics #27 (Batman’s debut). This is the first “full” appearance of Batman in the book, though I consider it too small to count.

“Bill and Bob would sit in Poe Park…”

attention to detail – This setting is based on period photographs of Poe Park.

“Though Bill had wanted Bat-Man…”

design – The sentence starting “Bat-Man became Batman…” makes sense in print, but requires elaboration/clarification when read aloud.

design – This marks the second appearance of Batman, though only his head on a comic book cover. Still no big splash.

“Almost immediately Bob hired…”

attention to detail – Those two guys standing in the background are Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, who were friends with Bill Finger and Jerry Robinson (seated).

design – This is an example of taking advantage of the medium of picture books. The fact that Bill and Jerry played darts is not significant to the larger story, but it is visually interesting so it became the setting for the information conveyed in the accompanying text. Otherwise it could’ve been another scene of guys at a desk.

“But Bill stuck…”

attention to detail – The phrase “superstitious, cowardly hearts of criminals” is a nod to Detective Comics #33, which first presents the origin of Batman and in which Bruce Wayne says “Criminals are a superstitious, cowardly lot. So my disguise must be able to strike terror into their hearts.”

backstory – No gun is visible on purpose, though the threat is still evident.

“Steadily, silently, Bill built…”

attention to detail – In the first sketches, Batman did not appear in this scene because the text is about Batman’s sidekick and villains.

However, in layout, I realized that we had not yet shown a whole, sizable Batman so I asked that we add him; as noted above, Batman does appear on a comic cover in two previous scenes, but in both cases, he is so miniscule that some readers may overlook him. And if kids got to this spread showing Batman’s supporting cast but still had not seen a “big” Batman, they would feel that it was either lame or an oversight.

attention to detail – At first glance most will presume that the title of the book comes from the familiar phrase “Robin the Boy Wonder,” and that is a good thing, but on this page a more literal inspiration for the title manifests itself. It is in Bob’s 1989 autobiography where he said he referred to Bill as “boy wonder.” He, too, was not oblivious to the Robin association, even if he did indeed call Bill this back at the beginning of Batman.

“Other comics creators…”

attention to detail – When I first saw the sketch in which both the Empire State and Chrysler Buildings are visible, I said I didn’t think that there was a ground-level vantage point (even with the lower skyline of the 1940s, when this scene took place) from which such a view existed. Upon seeing images like the one below and thereby learning I was wrong, we situated the scene on East 30th Street in an attempt at authenticity.

backstory – I did not want the inset showing Bill shaking an editor’s hand, for two reasons. One, we already had a handshake image (Kane and editor Vin Sullivan) and I felt including a second one would dilute the (tragic) significance of the first. Two, I doubt it happened. I would guess that an editor simply called Bill to ask for a story, and it was as unceremonious as that. I was overruled, and it was okay.

attention to detail – The gimmick book examples came from published sources and the astounding memory of Charles Sinclair.

“In 1948 Bill and his wife…”

never-published information – Bill nicknamed his son Fred “Little Finger.”

attention to detail – The ticket window is based on several period photographs.

design – Originally, the text specified the way Bill snuck Fred into the museum, but after we began discussing art, it became clear to me that it would be more fun to portray the trick solely in the art.

“While his son…”

backstory – The quotation “I’d like to return to the innocence of my childhood” was not essential, but I included it because it comes from the only known instance of Bill being mentioned/quoted in a mainstream publication (The New Yorker, 1965) in his lifetime.

“Bill was fond of writing…”

attention to detail – The size of the plug seems disproportionately small compared to the size of the fork and plate, but we’d already gone through several sketches to get the trajectory of Batman popping out of the toaster seem plausible (ha) so the size concern was one I had to let go.

attention to detail – If I had not caught that the absence of Batman on the earlier spread featuring the supporting characters/villains would seem like a goof, this would have been the first full-on appearance of Batman in the book.

“To get his stories…”

attention to detail – This desk scene is, unbelievably, perhaps, based on a 1940s photograph of Bill’s workspace. Yes, I went from being told only two photos of Bill exist to having not only 11 photos but also one of his writing desk.

attention to detail – That unassuming little paperweight is not just an illustrator flourish.

“During the first twenty-five years…”

attention to detail – Here is the page from the 1943 story in which Bill’s name appears…sort of. Look carefully...

“In 1964 that changed…”

backstory – Ty Templeton made up the blue-armored figure partially visible behind Julie Schwartz. I did not know this until after the book came out. I would have pushed for a glimpse of a known character, but I understand Ty wanting to limit potential intellectual property claims.

“The next summer…”

backstory – I wanted either Bill to be wearing a tie or one other panelist not to be because I felt Bill could come off as schlubby if he were the only one that casual. I was overruled.

“Jerry also did his own…”

attention to detail – The print over Bill’s desk…was a print over Bill’s desk. Thanks (again) to Charles Sinclair for injecting even more accuracy.

attention to detail – The image of “If the Truth Be Known…” looks that way because this scene takes place in 1965, a time when photocopies did not exist but mimeographs (in all their smudgy purple glory) did.

“Bill’s final Batman…”

never-published information – Bill’s death date (previously reported as January 24). design – “Come Monday” deliberately repeats a construct I used for the first historic “Batman weekend” (1939).

“Now grown…”

never-published information – Bill was cremated; Fred spread his ashes on an (Oregon) beach in an apropos shape. (No spoilers here. You have to see it for yourself.)

“In Bob’s later years…”

design – I did not think we needed the “Bob Kane” credit box there to identify him, and in fact worried it might be confusing, but was overruled.

“Jerry Robinson had long wanted…”

attention to detail – This image is based on a photograph of Jerry’s home office. I asked for the TV to show a still from the credits of the 1960s TV Batman show, though it’s been “modified to fit the screen.”

“It was named…”

attention to detail – That’s Jerry again, with Mark Evanier. We sought permission to include the Comic-Con imagery.

“From Milton to Bill…”

backstory – I normally don’t like posing questions in my text, but could not resist the penultimate line.

copy of guestbook (last page)

never-published information – Through a fluke both sad and fortunate, this remnant of Bill still exists.

“Bill was the greatest…” (inside back cover)

backstory – Two of these three quotations were not my original suggestions. I had used a quotation from Lyn Simmons, Bill’s second wife, and another by another associate of Bill’s, but neither of them appear in the story proper and my editor, Alyssa Mito Pusey, felt it would be better to quote characters the reader already knew. I was hesitant at first but came to see her point…and am so glad I did. I love it this way.

I love it all this way.

Thank you, Alyssa, Ty, Martha, and the veritable flash mob of others whose knowledge and talent combined to make this a book about which I am overflowing with pride.

More Bill Finger secrets abound, if you know where to look...

Published on April 30, 2013 04:00

April 29, 2013

Grandmaster Flash, the Fastest DJ Alive

This blog is not known for its hip-hop commentary.

(Once, however, I did write about hip-hop. An entry in What’s the Difference? is the difference between hip-hop and rap.)

Even though I’m not exactly a GOAT, I was fascinated to learn of a certain connection between hip-hop culture and comic books thanks to the 4/8/13 New York magazine, its third annual “yesteryear” issue. (In that same issue, I learned of a connection between Bill Finger and Colin Powell.)

This recollection by graffiti artist Fab 5 Freddy caught my attention:

Did you catch that? According to FFF, Grandmaster Flash is named after the superhero the Flash! It’s not even in GF’s Wikipedia entry!

The idea that comic books could inspire someone to become a graffiti artist hadn’t occurred to me before. But it sure makes sense. Both comics and graffiti have an urban sensibility, bright colors, and a history of being forbidden. And both had to work hard to be taken seriously as an art form. (Of course, I’m not condoning illegal graffiti.)

I can’t name a single Grandmaster Flash album or single, but I love the guy anyway.

(Once, however, I did write about hip-hop. An entry in What’s the Difference? is the difference between hip-hop and rap.)

Even though I’m not exactly a GOAT, I was fascinated to learn of a certain connection between hip-hop culture and comic books thanks to the 4/8/13 New York magazine, its third annual “yesteryear” issue. (In that same issue, I learned of a connection between Bill Finger and Colin Powell.)

This recollection by graffiti artist Fab 5 Freddy caught my attention:

I was into the whole comic-book concept. … And the whole comic-book concept of adapting this alternative persona was a big inspiration on the development of hip-hop culture. Case in point: Since I’m the fastest D.J., I’m going to call myself Grandmaster Flash. You’d create this alternative urban superhero persona who could do all the cool things that you fantasize about doing—graffiti or rap or break-dancing. It inspired a lot of New York City kids. It made me a graffiti artist.

Did you catch that? According to FFF, Grandmaster Flash is named after the superhero the Flash! It’s not even in GF’s Wikipedia entry!

The idea that comic books could inspire someone to become a graffiti artist hadn’t occurred to me before. But it sure makes sense. Both comics and graffiti have an urban sensibility, bright colors, and a history of being forbidden. And both had to work hard to be taken seriously as an art form. (Of course, I’m not condoning illegal graffiti.)

I can’t name a single Grandmaster Flash album or single, but I love the guy anyway.

Published on April 29, 2013 04:00

April 28, 2013

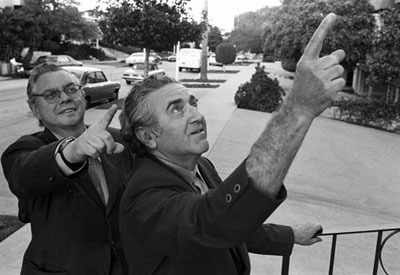

World's Greatest Detective and Secretary of State were almost neighbors

According to the 2004 Colin Powell biography by Reggie Finlayson (page 20), the family of the former Secretary of State moved to 952 Kelly Street in the South Bronx when Powell was four, so around 1941.

another source, Lodi News-Sentinel, 2/16/91

another source, Lodi News-Sentinel, 2/16/91

Just two years prior, something else notable happened on Kelly Street.

A superhero named Batman was created there.

I learned that Powell and Finger were nearly neighbors thanks to the 4/8/13 New York, its third annual “yesteryear” issue. (It didn’t mention Finger but I hadn’t known that Powell also has a tie to Kelly Street.)

I found an article about Powell returning to the Bronx in 2010 for a building dedication near Kelly Street. The article quoted Damian Griffin, Education Director of the Bronx River Alliance, who also lived nearby.

I emailed Damian, starting with “Here’s a question you don’t get every...well, ever.” I explained who I am and built up to this: “If you happen to live down the street from Finger’s former residence, would you be willing to go there and ask a tenant for the contact info of who owns the building? Consider it a cultural favor to New York!”

Damian responded as follows:

The coincidences continued. He also said that he used to know the family in the basement apartment of Finger’s former home. And upon doing a property map search, he saw that his daughter’s first babysitter now owns the building. (However, that turned out to be another person with the same name.)

By week’s end, Damian came through and sent me the contact information for the building owner.

As for why I want it, stay tuned.

another source, Lodi News-Sentinel, 2/16/91

another source, Lodi News-Sentinel, 2/16/91 Just two years prior, something else notable happened on Kelly Street.

A superhero named Batman was created there.

I learned that Powell and Finger were nearly neighbors thanks to the 4/8/13 New York, its third annual “yesteryear” issue. (It didn’t mention Finger but I hadn’t known that Powell also has a tie to Kelly Street.)

I found an article about Powell returning to the Bronx in 2010 for a building dedication near Kelly Street. The article quoted Damian Griffin, Education Director of the Bronx River Alliance, who also lived nearby.

I emailed Damian, starting with “Here’s a question you don’t get every...well, ever.” I explained who I am and built up to this: “If you happen to live down the street from Finger’s former residence, would you be willing to go there and ask a tenant for the contact info of who owns the building? Consider it a cultural favor to New York!”

Damian responded as follows:

We actually met when…you came as a visiting author [to my son’s school several years ago]! Funny world. I will check out the building on my bike ride to work this morning and let you know. If I can help, I certainly will.

The coincidences continued. He also said that he used to know the family in the basement apartment of Finger’s former home. And upon doing a property map search, he saw that his daughter’s first babysitter now owns the building. (However, that turned out to be another person with the same name.)

By week’s end, Damian came through and sent me the contact information for the building owner.

As for why I want it, stay tuned.

Published on April 28, 2013 04:00

April 27, 2013

Scarab in print and in person

Image from Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman.

Scarab from Bill the Boy Wonder, AKA Bill Finger.

Published on April 27, 2013 04:00

April 25, 2013

Fitchburg footwear

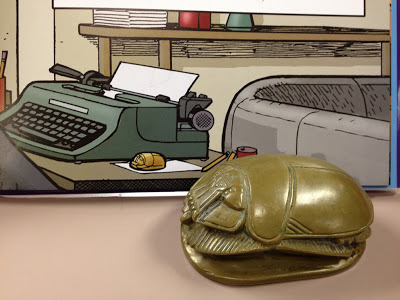

On 11/7/12, with fallen snow as fresh as the newly re-elected president, I spoke several times at Fitchburg State University in Massachusetts.

The stage in the auditorium where I gave my first presentation of the day was set up for a play:

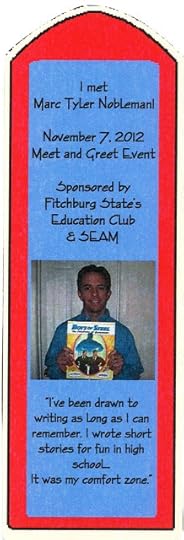

At a lovely reception with teachers-in-training, they distributed this bookmark:

The poster designed for my final talk of the day is one of the coolest ever done in connection to my work:

I enjoyed the first snowfall of the season except for the fact that the only shoes I brought were these:

Published on April 25, 2013 04:00

April 23, 2013

“Super Friends” writer writes letter to “Super Friends” comic

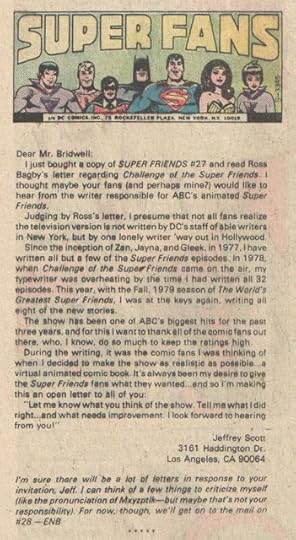

In 1980, Jeffrey Scott, who wrote most episodes of the Saturday morning cartoon Super Friends from 1977 to 1980, also wrote a clarifying letter to the comic book based on the show.

This is from Super Friends #33.

This is from Super Friends #33.

Published on April 23, 2013 04:00

April 20, 2013

Why “Bill the Boy Wonder” should have been nominated for an Eisner

A book I wrote, Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman (illustrated by Ty Templeton), should have been nominated for a 2013 Eisner Award.

I realize that this may come across as brazen or bitter. But it’s not deriving from the natural bias an author has for his work. In fact, most of my rationale is objective. (Can something be self-serving and have integrity at the same time?)

The quick list of reasons why I believe the book deserved an Eisner nomination:

It is unprecedented in topic.It is unprecedented in approach. It is unprecedented in research.It received mainstream critical acclaim, including an invitation to give a TED talk.It has already had a positive real-world impact on the family.It may have a significant real-world impact on fans.Kids, I’m happy to report, love it.

All of this is, of course, rewarding and humbling enough, but in terms of what this book has contributed to comics scholarship, not to mention social justice, the leading industry award should have acknowledged it. (Heck, part of the Eisner ceremony is the Bill Finger Awards!)

In particular, I believe that Bill the Boy Wonder deserved a nomination in at least one of these two categories:

Best Publication for Kids (ages 8-12)Best Comics-Related Book

But perhaps it is because the book is eligible for both that it was nominated for neither. Unfortunately, some have a perception that nonfiction for young readers or for all ages is not as “legitimate” as exclusively adult nonfiction. However, I am hardly the only one who strongly disagrees with this view. And I feel it makes an even stronger statement to tell this story a format that is, to some, so unexpected.

An elaboration on my reasons (which does not sequentially expand on the quick list above because the points intermingle):

For nearly 75 years, the sole creator myth that cartoonist Bob Kane started has reigned, and no previous book has gone far enough to debunk this. No previous book has put Bill Finger, uncredited co-creator and original writer of Batman (quite possibly the most popular—and almost certainly the most lucrative—superhero in world history) at the rightful center of the story. That alone makes this a book worthy of some distinction.

Yet there is more.

Bill the Boy Wonder, the result of five years (and counting) of intensive sleuthing, is the first book on Bill. Strange that it took this long; his peers and fans alike considered him everything from the most gifted comics writer of his generation to an unequivocal genius.

I was one of the last writers (if not the last writer) in touch with several of Bill’s Golden and Silver Age colleagues (Arnold Drake, Alvin Schwartz, Carmine Infantino) before they died, and none of Bill’s family and non-comics friends I contacted had ever been interviewed about him. I uncovered everything from his high school yearbook photo to the only known note in his handwriting to his WWII draft record to his death certificate (first two in the book, second two on this blog). None of it was a mere Google away.

There is still more.

Though Bill the Boy Wonder is the standard thinness of traditional picture books, it packs in a lot of previously unpublished bombshells:

Bill’s given first name and why he changed itthe aforementioned handwritten note (now the only surviving version because the owner—Jerry Robinson—lost the original after I copied it)who was receiving Batman royalties—properly and illegally—for Bill’s workquotations from Bill’s only known personal correspondencethe aforementioned yearbook photo (not as easy to find as you would think)nearly a dozen “new” photos from personal collectionsexactly when and how Bill dieda persistent rumor about Bill’s remains is wrong…and the truth is visually chillingBill had a second wife the only known mainstream press mention of Bill in his lifetime (The New Yorker, 1965)the only known time between 1939 and 1963 that Bill’s name appeared in a Batman comic…sort of…more than one example of entries from Bill’s famed but long-gone “gimmick books” (Alvin Schwartz mentioned one online but the others come from Bill’s longtime friend Charles Sinclair)Bill’s endearing nickname for his son Fredwhat Bill kept on his desk what Bill liked to eat late at night

And most startling of all:

the lone and previously unknown heir to Bill Finger: how I found her, who she is, and how my involvement helped her to receive long-overdue Batman royalties

For all of above, my book is the only print source.

Plus I continue to find even more info and I regularly share it on this blog and at speaking engagements, free of charge. That’s the modern model of storytelling.

Lastly, Bill the Boy Wonder may change pop culture history.

Despite what the comics community believed for decades, I discovered that Bill does have an heir, a granddaughter born two years after he died. She is in the unique position to try to correct the ubiquitous, contractually mandated, yet egregiously inaccurate credit line “Batman created by Bob Kane.” In the history of comics, whole credit lines have been added to superheroes after years of anonymity, but no existing superhero credit line has changed.

I know that a real-world repercussion is not a criterion for an Eisner nomination, and even if that never happens, the book is still a landmark work in the field.

Again a bold statement, but I can’t very well continue to call Bill’s failure to speak up on his own behalf a fatal flaw and then follow his lead.

* * *

Disclaimer: This opinion is no way a judgment on any of the deserving talents who were nominated; I am not comparing my work to theirs but rather assessing it on its own. Good luck to all of the nominees.

Published on April 20, 2013 04:00