Tony DiTerlizzi's Blog

October 1, 2024

BEHIND-THE-BOOK: “The Spider & The Fly”

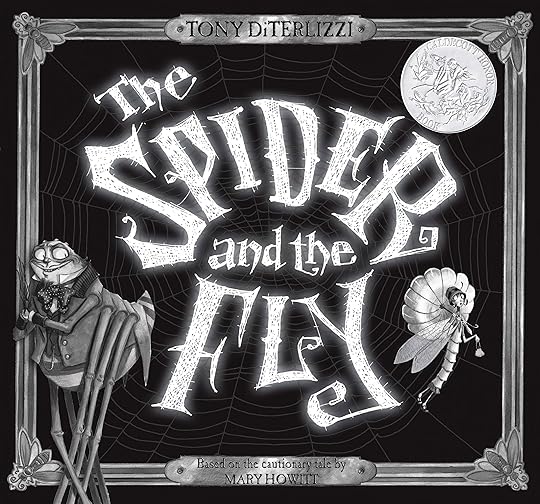

The Spider & The Fly was published 22 years ago, on October 1st. Creating this award-winning, bestselling picture book was a journey as twisting and winding as Mr. Spider’s web.

Simon & Schuster editor, Kevin Lewis (above), planned on publishing a picture book adaptation of Mary Howitt’s classic 1829 poem with hopes of approaching Caldecott-award-winning artist, Fred Marcellino, to illustrate it. However, Marcellino was battling colon cancer and passed away in July 2001.

Knowing that an artist with an understanding of insects was key to successfully bringing this book to life, the project languished until later that summer when an issue of Spider magazine circulated the S&S offices. The cover, painted by yours truly, depicted anthropomorphic insects cavorting around a fairy.

When Kevin inquired about my familiarity with insects, I replied, “Of course I can draw insects. I grew up in Florida. It’s nothing but retirees and gigantic insects down there.”

I was only familiar with the opening lines of Howitt’s famous verse (published when she was 30) so Kevin faxed over the entire poem. I was delighted by the unexpected ending (SPOILER: The Fly gets eaten. The End.)

This twist brought to mind the dark humor of Charles Addams, Edward Gorey and Tim Burton. I asked if we could print the book in black-and-white, which Kevin thought a novel idea.

Sketching began in earnest in August of 2001, with final art due on December 31st. The publication date was set for October 1st, 2002. The book dummy was the most realized I’d made at that point.

The book’s overall layout was inspired by silent movies of the 1920s. With that in mind, I based the design of the main characters after movie stars. Ms. Fly was inspired by actress Clara Bow, while Mr. Spider was part Peter Lorre and part Gomez Addams, with the charisma of Marlon Brando.

The vain Mr. Spider would change outfits throughout the story while Ms. Fly would remain in the same costume throughout.

Although the idea of a tour through a creepy dollhouse came early in development, with plenty of visual gags utilizing Mr. Spider’s past victims, how to depict the parlor was tricky.

It required quite a bit of exploration until it was decided it would be revealed to the Fly (and the reader) that it was Spider’s trophy room. An unused gag showed the mounted head of David Kirk’s Miss Spider, from his popular book series.

The ghost bugs, J. Waterhouse Cricket and Madame Butterfly, were my invention, created to add humor throughout.

There was a third ghost, a dead silverfish, but he was cut due to schedule limitations.

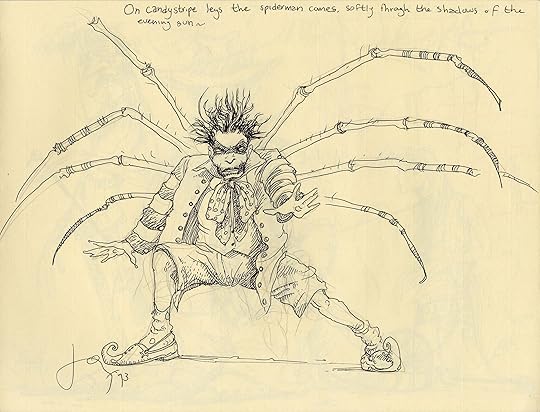

To get in the gothic mood, every morning I’d play The Cure’s 1989 album Disintegration, which quotes Howitt’s poem during the bridge of the hit song, “Lullaby”.

A longtime fan of that album, I’d sketched Robert Smith’s Spiderman back in 1993. A decade later Mr. Spider’s attire would bear some resemblance to this early design.

The finished paintings were accomplished using only two tubes of Holbein acryla gouache: Titanium White and Lamp Black. It was planned that the final art would be printed using a duotone process of only two inks: Warm Grey and Silver.

As the artwork neared completion grumbling began with upper management at S&S. Some were concerned the book was too scary for children, while others felt the black & white artwork limited the book’s appeal. Kevin countered with two award-winning black & white illustrated books: Chris Van Allsburg’s Jumanji and Amelia and Eleanor Go for a Ride, illustrated by Brian Selznick.

In January of 2002, Angela and I threw a Spider & Fly sneak-peek art party for friends.

In attendance were fellow artists, Donato Giancola and TSR alumni, Alan Pollack, as well as (then debut) author, Holly Black (below with Ang) , who exclaimed she loved the gothic art so much that, “…if we ever have a kid, Theo and I will read this book to them every day.” Subsequently, the book was dedicated to Holly and Theo.

The duotone printer’s proofs did not look good. The warm grey, printed over silver, was muddy and muted, lacking any clarity. Kevin and I were told that, to keep the book on schedule the ink could not be changed and we had to go ahead with what we had.

The ink could only be swapped with a true black in the second printing, but we feared the book would not make it to a second printing. Fortunately, (then) Simon & Schuster VP, Brenda Bowen, stepped in and solved our printing problems.

Promotional items, including a poster for schools and libraries, were created in the spring of 2002 and a lengthy book tour was planned, sending me to California, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, Louisiana and New York. I would travel with the original artwork to share my process at each event.

Reviews for the book were encouraging. Publisher’s Weekly said, “DiTerlizzi has spun a visual treat that young sophisticates and adults alike will enjoy.” While School Library Journal observed that, “This title is worth purchasing for its valuable artwork alone.”

On October 27th, 2002 The Spider & The Fly debuted on the New York Times Bestseller List for Picture Books. Other bestsellers include Halloween by Jerry Seinfeld, Olivia by Ian Falconer and Zathura by Chris Van Allsburg—whom I met at my event in Los Angeles.

On January 27th, 2003, the American Library Association awarded The Spider & The Fly a Caldecott Honor for outstanding illustration of a work published in the United States. Kevin quipped that, “We prefer the silver medal, as gold would’ve clashed with the silver duotone printed in the book.”

Other honorees included Peter McCarty and Jerry Pinkney (above). The Spider & The Fly would be nominated and honored by many state book awards in years to follow.

Although there have been offers to purchase the original artwork from the book, I’ve kept all the pieces, which have been exhibited in museums over the years, including the Art Institute of Chicago, Norman Rockwell Museum and Ducale Palace in Lucca, Italy.

Occasionally I’ve painted one-offs to sell for charity, including this piece done for the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art.

…and this piece, gifted to celebrated author Jane Yolen, on her 75th birthday.

On October 27th, 2006 First Lady Laura Bush read The Spider & The Fly at the West Palm Beach Public Library to a group of children. “What’s the lesson?” she asked at the end. “Just because someone says flattering words, don’t be tricked into doing something you shouldn’t.”

My take on this classic has been optioned for the silver screen several times but never made it past development. Scripts have been written by the likes of Brad Peyton and Tim McCanlies. A simple animated version was created in 2010 for the beloved UK show, Bookaboo, and read by actress Emilia Fox.

I returned to The Spider & The Fly in 2012 to celebrate its 10-year anniversary.

A new dust jacket was created with a reversible poster on the inside, inspired by silent movies posters of the 1920s. Maybe I can update the jacket once more for its 25th anniversary in 2028…

The Spider & The Fly changed my career in children’s publishing. Its success opened the doors for The Spiderwick Chronicles, and it is still read in schools and libraries every Halloween. I am grateful to Kevin Lewis and the team at Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers who’ve supported me and took a chance on creating this spooky cautionary tale for young readers. Here’s yours truly reading it during the 2020 lockdown. Enjoy sweet creatures!

July 5, 2024

Behind The ‘Monstrous Manual’: PART 10

Using the money I had earned from Dragon Mountain and the Monstrous Manual, in the summer of 1993 I rented a two-bedroom apartment, dedicating one bedroom as my “art studio”. Well…really I drew and painted all over the place, as you can see in the photo below. For normals this would be a dining area, but for this artist it was a place to work on personal paintings, like “Johnny Depp with Tiger Beetles”.

On the smaller easel, just below my faux fine art, is a sample piece I’d completed for Larry W. Smith (Art Director of Dragon magazine at that time) titled, “Conversation with a Brass Dragon”.

…but I am getting ahead of myself. Note the date that the photo was taken: August 22nd. This was the day after I’d returned from a visit to the TSR offices and the Gen Con gaming convention.

You see, once the Monstrous Manual was released in June, Project Coordinator and Career Catapult Man, Tim Beach, invited me to come meet the team up at Lake Geneva, Wisconsin–home of TSR’s corporate headquarters and birthplace of D&D. He also encouraged me to attend Gen Con (the first of many for me).

So, in August, I flew up to meet Tim, Peggy Cooper, and everyone I’d been working with. The unassuming, functional building, nestled in a business park, was home to a labyrinth of D&D-decorated cubicles and offices. To give you an idea, here’s fellow designer, Dale “Slade” Henson‘s cubicle. (Apparently, he was not a fan of Gen Con back then).

It was totally awesome for this nerd! I met staff artists like Jeff Easley, Dave “Diesel” LaForce and others. I hit it off with Tim’s roommate, fellow game designer Colin McComb, who I would become close with in years to come.

One person, in particular, that I met was renowned game designer, David “Zeb” Cook (shown above at Gen Con ’96). I’d illustrated several creatures in the Monstrous Manual that Zeb had created: the Tasloi, Yaun-Ti and Aboleth. Zeb purchased those original pieces from me, along with my Brownie illustration. He later told me he liked my take on the monsters, particularly the “little folk”, saying, “They were more than just ‘here’s a monster’ but [you] tried to add a sense of place and culture to them. The stuff really stood out. What they wore and carried didn’t seem like afterthoughts.”

That’s some mighty high praise coming from a legend.

Little did I know that Zeb and Peggy were in deep discussions on inviting me to fully illustrate a new campaign setting he’d been developing for the D&D line. But, this meant that I couldn’t be tied up on another big illustration job when the art order for Zeb’s new secret project was ready to go.

For the remainder of 1993, freelance work was lean. I illustrated a couple modules for the Dark Sun setting, some odds and ends for White Wolf Games, and a few Dragon and Dungeon Adventures magazine articles. In fact, one of my rejected Monstrous Manual sketches, of a giant scorpion, was finished as my first printed piece in Dragon magazine, accompanying the aptly named article ,”The Ecology of the Giant Scorpion”.

* Note that the art is accomplished in the same media (alcohol markers, ballpoint pens, bond paper) as the Monstrous Manual, except for the addition of an airbrush, which I’d use consistently over the next few years.

Do You Want to Get Paid to Draw Monsters? With Benefits and Health Care?Late in 1993, Peggy asked if I could fly up to TSR and meet the team I’d be working with for Zeb’s new secret project. I returned to (a now freezing cold) Lake Geneva where Zeb presented his weird, wonderful setting for Dungeons & Dragons: Planescape.

In an effort to retain an established look to the game (not unlike what Larry Elmore had down for Dragonlance or Gerald Brom had done for Dark Sun), I would be the sole illustrator for the line…except for Robh Ruppel‘s painterly covers. As if that weren’t enough, I was offered a staff position in TSR’s art department. HOLY CRAP.

Thankfully I did not have to give an answer right away on the job offer and my participation in Planescape wasn’t dependent on me taking it. Regardless, there was A LOT of work to do. I honestly had no idea how crazy my life was about to get…

…but that is another story altogether.

What’s important here is what my extra effort to do my very best–as well as my willingness to follow Tim and Peggy’s direction–on the Monstrous Manual had earned me. Planescape was the treasure at the end of this adventure.

So Long Old Friends, We Shall Meet AgainIf you are fan my work, perhaps you know where this story goes: I illustrated as a freelance artist on Planescape non-stop until the late 1990s and only stopped because TSR was descending into bankruptcy. I did not take the staff position, but instead moved with my then-girlfriend-now-wife, Angela, to New York City in 1996, with hopes of breaking into children’s publishing (surprise: we did).

Tim remained at TSR until 1995, writing mostly for the Mystara game setting. We would reconnect at Gen Con, though I became more intertwined with the Planescape team as time went on. Regardless, I always let Tim know that I would never forget the amazing opportunity he’d given me.

With the launch of my first children’s book in 2000, I no longer had the time to work on D&D, though my love for the game never wavered. In fact, I convinced my publisher, Simon & Schuster, to launch The Spiderwick Chronicles at Gen Con in 2003, which we did with much fanfare. That was a full circle moment for sure.

With my kid’s lit career in full swing and a feature film in the works, I would not return to Gen Con until 2015, where I was Guest of Honor and celebrating the release of REALMS: The Roleplaying Game Art of Tony DiTerlizzi. For me, Gen Con ’15 was a long overdue reunion of old friends, including Tim:

By then, I’d sold off much of the original artwork from the Monstrous Manual to devoted fans and collectors, keeping only a handful for my archive. Those pieces were exhibited in my first retrospective at the Norman Rockwell Museum of Illustration in 2017.

Wow. If 1993-Tony could’ve seen this, I don’t think he would have believed it.

Visiting Old FriendsAs years went by, I’d occasionally dust off the old Monstrous Manual drawings and think about how much I’d grown technically as an artist. In 2003, the incredibly talented comic artist, Claire Wending, decided to fully re-illustrate a self-published sketchbook she’d released in 1996. The side-by-side comparison was astounding. You could see her evolution as an artist when you compared the gesture, line work and style of her past and present. I loved it.

This was the same year we were set to attend Gen Con (to launch Spiderwick) but it was also the 10-year anniversary as my debut of an illustrator for games. I printed up my own souvenir sketchbook, Ten Imaginary Years (1993-2003) and, on the last page spread, redrew the dryad from the Monstrous Manual:

This exercise led to other revisits over the years. Here’s that Kenku that was never printed, redrawn in 2006. He later became a miniature in the DiTerlizzi Masterworks line.

And here’s another cantor-wearing Mind Flayer from 2012. Is the skull the correct size now?

I’ve revisited my Brian Froud-inspired gnome illusionist a few times; this rendition from 2015 being a favorite:

Speaking of Froud, I also realized my Dark Crystal-Garthim-inspired Umber Hulk in 2015.

For my 2017 Norman Rockwell exhibition, I created a mobile of fairies, including an updated take of the D&D sprite:

During the 2020 pandemic, over daily live-stream sessions of “Drawn to Fantasy“, I returned to the old Monstrous Manual on several occasions, resketching the Locathah, Orc and Sylph.

As the decades have passed, my memory of this experience only glows brighter. The opportunity to reinterpret these beloved monsters with pencils, markers and paper–as my paid profession–was a dream-come-true for this kid. A kid whose overactive imagination was set ablaze when he first cracked opened that slim hardcover book back in 1982: The Monster Manual.

Hey, Tim Beach still designs games! His latest, Start Here, is an introductory role-playing game system for young players. You can learn more about it here.

Many of those early ink drawings, along with some of these recent revisits, were self-published in THE PEN & INK DRAWINGS OF TONY DITERLIZZI: Collecting Three Decades of Fantasy Art from the Artist’s Sketchbooks, which is available from Noble Knight Games right here.

This year, I released a Mini-Monster Portfolio of some of my favorites. Although I had to adjust the poses to fit the vertical format, the color reproduction is spot on! It is also available at Noble Knight Games right here.

Thank you for your kind words, notes, emails and messages during these posts and over the years. It keeps me going. I hope to see you soon!

–td.

July 2, 2024

Behind The ‘Monstrous Manual’: PART 9

Welcome back to a deep dive of my experience working on the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Monstrous Manual. As I mentioned at the start, I finished illustrating the Dragon Mountain boxed set adventure on February 1st, 1993 and began immediately on the Monstrous Manual the following day.

All 100 pieces were due on March 23rd and completed in less than two months. According to this journal entry in my sketchbook, I finished right on time:

I was exhausted but excited. It had been a seven-week marathon of sketching, revising, phone calls, faxes, FedEx and finishing–all completed at the kitchen table of my childhood home, the same table I’d copied pictures from Dave Trampier, David Sutherland and Erol Otus a decade earlier. Talk about a surreal moment.

It had been a glorious experience and I was ready for more. As luck would have it, Project Coordinator and Expert Cat Herder, Tim Beach, rang me up with just that: MORE monsters were needed!

It turned out that he’d forgotten to assign me the “plant people”: the Myconid, Shambling Mound, Treant and Vegepygmy in my original art order! So, during the last week of March 1993, I scrambled to finish these pieces, along with a few others…

ILLUSTRATION #234: Plant, Intelligent

“[Regarding the inspiration behind the Shambling Mound] Strictly from ‘The Heap‘ in Airboy Comics, of which I was a great fan.”

–Gary Gygax, 2007

The Shambling Mound made its debut in the 3rd issue of The Strategic Review in fall of 1975, described by Gygax as, “…a heap of rotting vegetation.”

Early depictions certainly drew from The Heap comic character and, likely, Marvel Comics’ Man-Thing; however, my 1992 rendition kept true to Gygax’s original description:

Although mine drew inspiration from a different “heap of rotting vegetation”…

For fun, I posed him looking over his shoulder, à la the famous 1967 Bigfoot film footage, as if he’s shambling back to his swampy domain. This was among the last pieces I completed for the Monstrous Manual…

…and it would be another of my designs that would be later molded in metal (perfectly captured by sculptor, Dave Summers).

In all, six of my illustrations were the basis for official D&D minis that year.

Regarding the other “plant people” entires, I don’t recall rendering them and I’ve no known sketches either, which leads me to think that they were each drawn on a single sheet of paper, faxed to Tim, discussed over the phone, then completed. After all, it was crunch time.

As well, there were a couple of redos that Tim requested, which happens on big projects like this when many artists are contributing: personal life interferes and artists can no longer meet the deadline, or the piece isn’t quite what the game designers were hoping for, or the requirement for the illustration has changed due to a shift in the content its meant to accompany.

Remember, while all this artwork is being finished, the text is being revised and copyedited. On top of that, the pages are being laid out and typeset by the designer (back then, this was done in QuarkXPress). In fact, the Monstrous Manual used a keyline process, which meant areas of each page were designated to print in color (the art) while others where set to print only in black (the text). This kept printing costs down. Nowadays the entire page would be printed in color. All this production continues right up to the moment the book is sent off to the printer. Like I said, a marathon.

Monstrous Redos and A Lost GremlinThere were several illustrations Tim wasn’t 100% happy with and he wanted options. These images were the Minotaur, Ettin, Leprechaun and Harpy. I’ve mentioned what became of the Minotaur and Ettin already. As for the Leprechaun, there are no sketches nor do I have any memory of creating it, so I suspect the process was the same as the “plant people”. The harpy was a bit of a different story.

There was an ink drawing in my ’92 sketchbook, based on the metal miniature by Ral Partha. Later sketches push the nose/beak idea but it never made it past this point.

Tim’s memory on this is fuzzy, but the reasoning for a redo may have been that the harpy had been classified as “bird-folk” (coming up) or a “mythical monster”. Since I had rendered some of the other mythical monsters (like the Medusa, Cyclops and Minotaur) the change was in order to retain an artistic continuity; however, on top of this reclassification, Tim was also dealing with the same PG-13/no-nudity issues that we faced with the nymph. In the end, he ran with what he had in hand (a solid illustration by Jeff Butler), and my harpy never made it past the sketch phase…but others did and one little troublemaker was even finished…

ILLUSTRATION #168: Gremlin, MiteAmidst various sketches of elves in my ’92 sketchbook, there was a drawing of a Jermlaine that Tim thought, “… is a really good Mite, which can also be used in this [the Jermlaine] illustration.”

Both the Jermlaine and Mite are variations of the D&D version of a gremlin–small mischievous troublemakers–that made their first appearance in 1981’s Fiend Folio. The Jermlaine was completed before my deadline and sent up with the bulk of the art.

I think the plan was to push the Mite at the end of my art order to finish if time permitted. I did finish it and sent it up, along with those last-minute pieces.

*This is a low-res scan of the original from 1998 before it was sold off, so the colors are approximate.

Like I said, there is editing and reorganization happening to the book’s layout and text, all while art is being produced. As he’d done with other similar monster-types, Tim folded several of the “mischievous critters” under the entry for Gremlin. You see, on their own, none were fleshed out enough to warrant their own page and separate entry. But this rearranging of the entries made for a lot of text and not a lot of space for art. Sadly, the Mite would be cut from the book.

There was yet another illustration that would never see print as well…or maybe it did, we just didn’t have the right means to see it.

ILLUSTRATION #166: Invisible StalkerAlways a funster, Tim (along with Monstrous Manual editor Doug Stewart) signed a blank sheet of paper as the art for the Invisible Stalker (a classic D&D monster present since the game’s debut) and added it to the stack of completed artwork before handing it over to art director Peggy Cooper for scanning. Coincidentally, I’d sent over a piece when I shipped up my art for the book. It remains in Tim’s collection to this day.

I hear the Ral Partha miniature of this one came out great but didn’t sell well. I wonder why?

But Wait, There’s More!After delivering the last stragglers to TSR, Tim and I continued having conversations about the possibility of having me redo a few other images, too. Some of the “bird-folk” illustrations that were turned in were not as evocative as he’d hoped. I got to work immediately, completing sketches and ink drawings for both the Kenku and Aarakocra:

…which Tim liked but ultimately did not go with, as the Art department was close to finishing the book and preparing it for print. Yet, the conversations continued and there was talk of me taking a stab at some other monsters as well:

I cannot recall if the above were sketched because Tim had asked or (more likely) because my enthusiasm compelled me to do them. These next ones; however, certainly made it past the sketch stage. Like the Kenku, they’re inked and ready for color:

But, in the end, time ran out. All these drawings were filed away, never to appear in print.

By the end of March 1993, my work on the AD&D Monstrous Manual was completed.

Phew!

But Wait, You Didn’t Talk About The…Yes, there were plenty of other monsters I illustrated that were not covered in this blog series, in particular; the Lycanthropes. This is due to several factors: I don’t have any recollection of creating the artwork, I don’t own the original artwork (or decent laser copies) and/or I don’t have a lot of sketches and process for them. You see, for every interesting behind-the-scenes story of how I came to draw a Displacer Beast there’s a Giant Centipede that was simply completed so I could move on and make that deadline.

However, here are scans of sketches for a few that I did not discuss.

I love when a longtime fan shares that they first came to know my work through the illustrations I’d done for the Monstrous Manual. Often I am told that many enjoyed, “…looking for those little ‘td’ initials next to the art.”

Part of the impetus for this series of posts was newly discovered correspondence from Tim during the time that we worked on this book (above). It provided weekly interactions where sketches were given feedback and final art was revised and approved. It also helped me piece together a timeline of when the art was completed.

A fascinating detail that became quite apparent was how my initials evolved each week as I finished batches of art.

As mentioned earlier, at the end of each week I would head to the local copy shop to have a set of color laser copies made and send them up to Tim for feedback. When I rearranged my artwork in a chronological order it was interesting to see my initials transform from a hand drawn font to a genuine signature. The graphic above tracks my confidence growing week-by-week as an artist.

I won’t bore you with a detailed timeline (though if you are curious, you can take a look at it here). Either way, now, when you page through the old Monstrous Manual you can note the style in my initials and approximate when I rendered your favorite monster.

One Last ThingIf you were to page through my contract, you might say that the business-end of this job wasn’t worth it. As a work for hire, all rights of the artwork (except for prints) were owned by TSR and I was paid $70 per illustration. That’s about $150 today. You may be thinking, if I was just starting out now would I still take this job? Unequivocally, the answer would be YES.

This high-profile project gave me so much more than money: it built my confidence as an artist, taught me how to truly collaborate and work with an editor, and invited me in to become a part of a legacy that I held dear. If I could go back, I wouldn’t change a thing (except keep a better archive of the artwork).

The thing is, I grew past this and became an artist who went on to successfully create new stories of my own. This experience, back in good ol’ 1993, was a building block in the foundation of my career. I’ll elaborate more on that in the final post of ‘Behind the Monstrous Manual’.

Next: Part 10: After the Monstrous Manual

June 26, 2024

Behind The ‘Monstrous Manual’: PART 8

I am sad to say our trip down Monstrous Manual Memory Lane is nearing its end but don’t fret, we still have a few more monsters to cover: Giant creepy crawlers that are iconic Dungeons & Dragons monsters, like…

ILLUSTRATION #3: AnkhegThe giant subterranean invertebrate known as the Ankheg (ANN-kegg) made its colorful debut in issue #5 of Dragon magazine in March 1977 and, like the Remorhaz (REM-hor-RAZ), was first visualized by legendary TSR artist, Erol Otus (who also provided these pronunciations).

Sixteen-year-old Otus not only rendered this first illustration, he wrote up the details as well! I wanted to know more about the Ankheg’s origin, so I called him up so we could chat about it further.

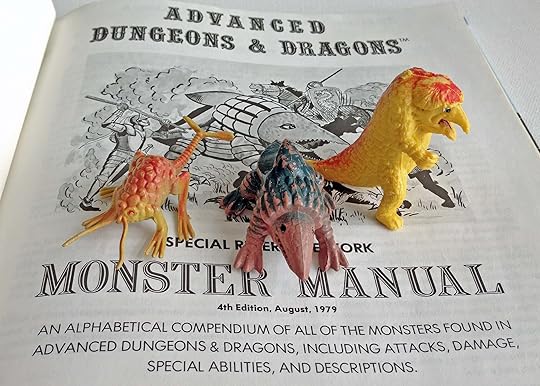

“The inspiration for the aesthetic of the monster came from this rubber creature I owned,” he said. That creature was but one of the many rubber “scary” toys that were commonly found in gumball vending machines and dime stores in the 1960s and 70s.

As a longtime collector of these weird creepy-crawlers, Otus realized many of them were the perfect scale to use as monsters with his gaming miniatures. In fact, a companion to his rubber Ankheg inspired yet another legacy D&D monster.

“Although [TSR veteran] Rob Kuntz created the Remorhaz, it was based on my drawing,” he said, “which, like the Ankheg, was inspired from one of my rubber jigglers.”

That is so cool! Get it? ’cause the Remorhaz is an ice worm and it…nevermind.

Fast forward to 1993, Project Coordinator and DiTerlizzi Director, Tim Beach, was paging through my ’92 sketchbook, hunting for potential images to be used in the Monstrous Manual. He thought my Ankheg sketches were, “Really good.”

The creature’s head design was initially inspired by that underground bug muncher, the Ant Lion, but I decided on the more robust, wasp-like head in the end. As you can see, the sketch on the far left (marked with the blue “X”) became the basis for the final art.

This was among the first batch of finished pieces that I sent up to TSR and displayed the same naturalism that I strove for in the Troglodyte and Locathah.

When I look back on this art, I am reminded of the cabinet graphics for one of my favorite classic 80s arcade games, Centipede. I was not consciously pulling from that iconic art for this piece, but I can see it there, in the mix.

Speaking of giant insects, this Volkswagen-sized Beetle (see how I did that?) started out as an ink drawing alongside the Ankheg in my ’92 sketchbook.

I used reference from an amazing book on beetles that I’d borrowed from the local library (that’s what you did before Google) to make color laser copies from (also, no color printer in your home office), ultimately using this beautiful Rhinoceros beetle from Venezuela for my pose.

There is also a bit of influence from the comic book legend, Jean Giraud (aka Möebius), in the execution of the final piece, specifically from his Arzach series. I would return to Moebius for inspiration after I completed the Monstrous Manual for the Dark Sun adventures I illustrated afterwards.

This famous dungeon scavenger made its debut in the early years of the game back in 1975’s Greyhawk supplement.

I’ve read that this first illustration is attributed to Dave Arneson. When I corresponded with Tim Kask about the origins of D&D monsters inspired from Chinasaurs, he stated that the Carrion Crawler and Purple Worm (coming up next) also came from toys, but I have yet to find exact matches. Though, like Erol Otus’ Ankheg and Remorhaz, there are plenty of rubber wiggler toys released in the 1960s that would easily fit the bill.

I had not drawn the Carrion Crawler in my ’92 sketchbook so the below was done in February of ’93 (along with a Kilmoulis that almost made it into the book).

Tim had notes: “I like the sketch, but it looks too much like a larva of some kind. (Interesting question: what does it become after it pupates?) extend the body, and put legs along more of its length. I like the general look of the body and head, though…”

I was never 100% satisfied with this illustration. Looking back, I should have given it different legs, perhaps more like a velvet worm, but I didn’t have that clarity or the time to redraw it. I still had a horde of monsters to render like…

ILLUSTRATION #294: Worm, Purple

“These huge and hungry monsters lurk nearly everywhere just beneath the surface of the land.”

–Gary Gygax, 1974

Speaking of worms, another monster from the earliest edition of the game is the gigantic Purple Worm. I do not know if Gygax was inspired by the enormous sandworms of Frank Herbert’s 1965 classic sci-fi novel, Dune, but I sure was when I sketched these suckers in the fall of 1992.

Tim sent reference samples that I, sadly, no longer possess. However, he confirmed that they were photographs of a lamprey’s mouth. You can see how integral his reference was when I finalized the design. Shai-Hulud!

Old fat spider spinning in a tree!

Old fat spider can’t see me!

Attercop! Attercop!

Won’t you stop,

Stop your spinning and look for me?

–from The Hobbit, 1937

The Attercop Ettercap made its D&D debut in the Games Workshop-created Fiend Folio, published in 1979. The late Russ Nicholson illustrated that version, but it was Daniel R. Horne’s wonderful rendition in the Monstrous Compendium Volume II that inspired me:

My ’92 sketchbook had a few Ettercap doodles, which Tim responded to: “Your sketches have potential; play down the ‘beer belly’ and exaggerated features.”

With that art direction in mind, I created a more finished drawing:

Tim liked this revision, saying: “Great. Definitely the best Ettercap we’ve ever seen. A design on the stomach is good, too.” That design, and overall coloration in the final piece, was taken from an Ant-Mimic spider, found in my trusty Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Insects & Spiders.

The response from Tim was so positive that I simply laser-copied the pencil drawing onto a sheet of paper and colored it. TSR received the artwork for the Ettercap late in February ’93. Tim replied: “Really, really, very excellent. He looks very nasty; someone else also commented that ‘it finally looks like something to be frightened of’.”

That was exciting news but not all my interpretations of classic D&D monsters would go over so well…

ILLUSTRATION #226: Otyugh

The Dianoga of D&D is a foul beast known as the Otyugh. As far as I know there has been no definitive story on the inspiration for this stalk-eyed trash eater; however, the timing of Star Wars’ phenomenal release in May of 1977 perfectly aligns with this creature’s debut in the Monster Manual, published later that year.

I had a sketch of an Otyugh in my ’92 sketchbook, on the page with the Minotaur.

Tim noted, “See the original picture of the otyugh for the placement of the eyestalk.” …which somehow, I got wrong:

Tim was NOT having it: “No. As stated in the original art order, ‘generally speaking, now is not the time to develop new takes on old creatures; stick with the standard appearance where possible; this applies even more stringently to the ‘classic’ AD&D monsters’ and ‘see the original picture of the otyughs for the placement of the eyestalk.’ Put the eyestalk, with three eyes, on the top of the creature. I’ll go for the rest of the new look for the critter, and we really like the slimy look and the flies nearby. It would be nice to thicken the frontmost tentacle too, but that’s optional.”

Whoa. Okay, Tim. You could have simply said, “Put the eyestalk, with three eyes, on the top of the creature.” Honestly, I wasn’t trying to redesign this critter. I just did not completely understand Otyugh anatomy. Sheesh!

ILLUSTRATION #239: Rakshasa

“All Rakshasas wear human clothing of the highest quality”

–Monstrous Manual, page 299

This entry should really be with the other mythological creatures but I’ve saved it as my last little story. Why? Because it perfectly captures my life in 1993.

I mentioned at the beginning that I don’t keep journals, but I do keep sketchbooks that chronicle creative periods of my life and 1992 was certainly one of those periods.

As well as preparing my samples for TSR, I often journaled in the form of “freeform” drawing–surreal, dreamlike imagery that blurred together to form bizarre, Hieronymous Bosch-inspired pictures. Here’s one of me taking in Pablo Picasso‘s work:

Reappearing motifs would occur in these pieces: the ocean, objects and people suspended by strings, and various iterations of myself (and friends) as mythical creatures or animals:

Aside from the Mad Hatter’s hat, the clothing here is accurate. In my attempt to be an “eccentric artist” I often wore odd combinations of clothing and jewelry purchased from thrift stores and whatever I could afford at the local mall. Surely, by now, you can see where I am going with this.

This illustration is a fantastical reflection of fashion back then, a snapshot of the early 90s–from the popular M.C. Hammer-style harem pants (that I assure you, I did not own…though many did) to the plum-colored jacket you may have noticed in my art school photo.

As seen in this catalog page (from Oaktree Menswear), this was the fashion of the day. A style that twenty-something-Tony coveted, but could not afford, so it is envisioned here in my drawing of the Rakshasa.

I no longer own this original artwork, but when I look at it I smile because it takes me right back to that time in my life. A time when it seemed that, at last, a door of opportunity opened before me. And if one dream could come true, could others? Did I dare chase more? You bet your lucky 20-sided dice I did.

NEXT: PART 9: TD, Monster machineJune 22, 2024

Behind The ‘Monstrous Manual’: PART 7

Welcome back to a deep dive of my experience working for TSR on the 1993 Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Monstrous Manual. We’ve covered quite a bit leading up to this point–from my humble beginnings as an aspiring art school graduate to rendering some of D&D’s classic creatures.

Like many Gen X kids, I was obsessed with D&D since its rise to popularity in the 1980s. When I wasn’t playing, reading rulebooks or penning my own adventures, I was drawing, as can be seen in my rendition of David A. Trampier‘s illustration of a Lizard Man from the 1977 edition of the Monster Manual.

Tramp’s image is burned into the memory of so many of us who played back then. Even the miniatures, by Grenadier, were based on his iconic design.

When it came to illustrating the Lizard Man for the Monstrous Manual, I had to nail it. So, no pressure 1993-Tony…no pressure at all.

ILLUSTRATION #183: Lizard ManLizard Men populated D&D right from the start and were first described in the Greyhawk supplement back in 1975. This booklet also featured a large illustration by Greg Bell, which would go on to become the logo for TSR during the 1970s.

My ’92 sketchbook had a few drawings which Project Coordinator and Reptilian Humanoid Handler, Tim Beach, liked: “Good Lizard Man on page 49; perhaps square up the back of the head a bit, for a more dinosaur-like look, rather than having such a curved neck… refer to the first edition art as ‘the’ source.”

In an unusual step from all other images in the book, (save for the Medusa) I inked the Lizard Man on a large sheet of 11 x 17″ paper. I wanted to be able capture all the scaly details.

You can see the influence of David Trampier’s bold image, even in my linear design. This ink drawing was laser printed horizontally onto an 8.5 x 11″ sheet of paper, where I added his poleaxe and tail before finishing.

His coloration was taken from that handy Audubon Society Pocket Guide that I mentioned earlier (for the naga), specifically this image of Collared Lizards.

Now, this bad boy wasn’t the only lizard I’d referenced from my Pocket Guide. There was one more reptilian humanoid that I’d already completed just before I started the Lizard Man. In fact, it was the very first image I rendered for the Monstrous Manual.

ILLUSTRATION #281: TroglodyteThere were sketches in my ’92 scrapbook of troglodytes:

Tim responded, “The head nearest the ‘troglodyte’ label is best; don’t let ‘scrappy’ become weaselly; keep them menacing.” My fin-headed version was based on David Sutherland’s illustrations from the Monster Manual and 1978 module, Descent Into the Depths of the Earth.

It is interesting that Gary Gygax changed the creature from the traditional depiction of prehistoric caveman to bipedal reptile, not unlike the Sleestaks from Land of the Lost.

I set out to draw a new sketches in February 1993, going for a more naturalistic approach.

Like the Lizard Man, This lifelike drawing was accomplished using real-world inspiration. I referred to a photograph of a Western Whiptail from my Audubon Pocket Guide for scale placement and pattern.

Tim approved the new sketch and I was off. The troglodyte entry may appear in the latter half of the book but it was the first finished illustration I completed.

Though it is not “menacing” as Tim had requested, there was something magical about this piece. It felt alive. This not only marked the start of my work on the Monstrous Manual but the beginning of my methodology for rendering realistic, yet fantastical, creatures that seemed more at home in a naturalist’s field guide than a fantasy setting. Although twenty-three-year-old me could not keep up that level of realism under the deadline I’d been given at the time, I would eventually have my opportunity to fully realize this vision in Arthur Spiderwick’s Field Guide to the Fantastical World Around You.

ILLUSTRATION #184 : LocathahAs I mentioned at the start, I was obsessed with D&D and dreaming of working for TSR throughout 1992. I even sketched on napkins at restaurants and bars.

Although these doodles were of Sahuagin, Tim felt the topmost sketches were perfect for the Locathah–a “fairly civilized” race of aquatic nomads who first appeared in Dave Arneson’s Blackmoor supplement in 1975. Continuing with the same approach I’d used for the troglodyte, I found inspiring head reference of a Sandpaper fish in my Animals book from Dover Publications.

A detailed pencil drawing was completed, which I then had laser copied onto bond paper to color.

I still did not possess the skills to fully synthesize all reference into a cohesive creature design (like his legs and feet) but, like the troglodyte, I was excited with this level of natural realism in portions of this piece and eager to draw more fish-men.

A freshwater fish, a Mooneye, served as my inspiration for the Kuo-Toa, a classic D&D monster that made its debut in the appropriately named adventure module, The Shrine of the Kuo-Toa.

Honestly, I prefer David Sutherland’s design on this cover over mine; although, coincidentally, my rendition of the Sahuagin (up next) bears quite a resemblance to his art here.

In all my years of playing, my adventuring party never encountered these evil fish guys. My guess is they are the D&D version of H.P. Lovecraft’s “Deep Ones” from his 1931 Cthulhu novella, The Shadow Over Innsmouth. So it’s kind of perfect that he’s coincidentally drawn here with a Mind Flayer (which Gygax created based on the Lovecraftian novel, The Burrowers Beneath).

Tim had minor adjustments to the sketch, adding: “Kuo-Toa never had tails, but we like it.” As I’d done with Medusa, the ink drawing was laser copied, then the top half of the critter was cut out and mounted onto a new sheet of paper. From there, the bottom half was redrawn then it was laser copied once more and colored.

I don’t recall how I hit upon the idea of the spearhead being made from the the serrated snout of a sawfish, but it was that type of detail (just like the gnoll) that supported my philosophy of making the monsters as interesting as player characters. Note the string of conical shells on his strap…these represent each foe he’s struck down.

ILLUSTRATION #246: SahuaginThe “Devil Men of the Deep” made their (quite detailed) debut in Dave Arneson’s Blackmoor supplement back in 1975.

My first question to Tim was how to pronounce their name. He said there were two pronunciations accepted amongst the staff at TSR: sah-HWAH-gin and suh-HOO-uh-gin…or, more simply, Sea Devil.

These devils, which bring to mind the “Gill-Man” from the 1954 film, The Creature from the Black Lagoon remained much the same design-wise throughout the 1970s-80s. But Daniel R. Horne’s ink drawing for the ’89 Monstrous Compendium was less human and more creature-like, which got my creative gears turning.

As mentioned earlier, I had sketches for the Sahuagin but Tim felt they were better suited for the Locathah, so it was back to my Animals book for ideas. An engraving of a deep-sea Lightfish and Dragonfish(?) fired those creative gears into high speed.

I came up with this design, which Tim thought was, “Pretty good. Half out of water is good. Maybe try the head a little more shark-like (they hand with sharks, after all). I think the beady eyes might be better than the bulging type. If you really don’t like the shark look, though, go with what you’ve got.”

I didn’t want the Sea Devils looking like Jabberjaw, so I went with what I had, adding webbed feet, tail and a diving knife. Tim thought it came out “good”.

Good enough for this redesign to remain the basis for the Sahuagin for the next 15 years, up to fourth edition. I suppose I hooked a big one with this illustration! Sorry, I had to do it.

ILLUSTRATION #276: Thri-KreenOur last entry is among Tim Beach’s favorite critters in the Monstrous Manual, the 11-foot long mantis warriors known as the Thri-Kreen. By the way, if you ever watched videos of what an actual praying mantis will capture and eat (seriously, do not Google it), you’ll know that a gigantic one doesn’t really need weapons. It’s terrifying just by its mere existence. But sure, why not give it razor boomerangs and a spear?

This menace had an unusual debut in the 1982 Monster Cards, where it was first described and listed as “New” (instead of referencing what book or adventure module it came from). The Thri-Kreen would later return the following year in the Monster Manual II. They remind me somewhat of the tharks from Edgar Rice Burroughs’ 1917 sci-fi classic, A Princess of Mars.

Despite a deep love of insects–especially mantids–I did not have any drawings in my ’92 sketchbook because this was one of the few monsters I was not familiar with. (Our gaming group had not yet ventured into the Dark Sun setting, which featured mantis warriors decimating thirsty, sunburnt heroes.) But Tim gave me the lowdown and I was off sketching.

Of all the feedback I received from Tim during the entire run of the Monstrous Manual, the Thri-Kreen received the most notes: “No pupils! I know real mantids have eye spots, but Thri-Kreen don’t. And don’t give him a nose. The face on the current MC (he’s referring to the 1991 Forgotten Realms Monstrous Compendium, seen below) is really good. Make sure they have side-to-side mandibles that will do damage. Make his torso thicker.

The hands have three opposed thumbs, essentially, and these should be somewhat pointed at the end to give him claw damage (or, if they actually show in the final, it would be cool to give them interior serration like a preying mantis’ claws). Or, we can assume their claw damage comes from the spikes on their arms.

Also, modern Thri-Kreen have four arms and two legs. They are insects, not insect like, so all limbs should attach at the thorax, though they can attack high, middle, and low. For the legs, see the attached pictures; (I no longer have the reference pictures of mantids that he’s referring to) either style is fine… With only two legs, and 450 pounds of body, these seem more structurally sound….(He goes on to give additional notes on a page of sketches that I cannot locate, then onto the ones on the legal paper shown above)… Second page, upper left, the face looks goofy; top right, okay, but the mandibles look weak (plus the human nose is out); middle right, (obscured by my dumb “td” stamp) the pose is okay, but I like the other one better.

In case it isn’t apparent, I really like Thri-Kreen.

No, Tim. I didn’t get that at all from the novel you sent back. Anyways, somehow I miraculously was able to synthesize pretty much everything he asked for using multiple mantis images for reference and even mantidfly reference, which is a different insect species entirely.

Tim responded: “Excellent–but lose the wings. The torso could still be a little thicker, but it’s okay. You may also want to shorten the polearm a bit (optional). Finally, it would be nice to see a throwing wedge somewhere, hanging on the harness, maybe; it’s a very traditional Thri-Kreen weapon.”

I tried to incorporate every change he requested before coloring it up for the final.

This one really relies on the drawing more than the color. This scan (supplied by Tim) offers detail not seen in the final published book. (Yup, I am happy to report that this was another piece of art Tim purchased from me and still treasures to this day.) At the end of February of 1993, with the deadline for the Monstrous Manual just thirty days out, Tim sent this note:

“Some day, we are supposed to a do a Thri-Kreen handbook for Dark Sun. I’ve asked to write it, and I’ve been told I’ll have first shot at it, but I wouldn’t start writing it for at least a year. Assuming everything works out, though, I’d like to keep you in mind for the art on it.”

…little did either of us know that within a year I’d be the exclusive illustrator for a new line from TSR called Planescape as well as contributing to White Wolf Games’ new line, Changeling. However, my old classmate from art school, John Dollar, would go on to illustrate Tim’s The Thri-Kreen of Athas in 1995. He did a bang up job, too. (I wonder how many notes he got from Tim?)

Well, I’m just about finished with my behind-the-scenes stories but I do have a mess of sketches to share, along with a few more memories. We’ll get to those next!

Next: Part 8: TD, the Monster MachineJune 18, 2024

Behind The ‘Monstrous Manual’: PART 6

I’m highlighting some classic, iconic monsters of Dungeons & Dragons that I had the opportunity to illustrate back in 1993 for the Monstrous Manual

The Fauna of D&D

The Fauna of D&DWe’ve covered literary-inspired humanoids, monsters of myth and even the fae folk of fairy tales, but this entry is all about creatures that are unique to the game when they made their debut in the 1975 Greyhawk supplement…even though, they too, had their roots from outside sources, like these toys from Hong Kong which inspired three major beasties:

ILLUSTRATION #252: Rust MonsterLike many, I played with “Chinasaurs”, the plastic figures often found in toy aisles of general stores during the 1970s-80s. In fact, I wrote a detailed article about their transformation from Ultraman knockoffs to the stuff of gaming legend.

Though the Rust Monster was listed in the Greyhawk supplement there was no accompanying art. That would come a few years later in the Monster Manual, where we see a clear connection to the toy in David Sutherland’s iconic illustration.

When I attempted my rendition in 1992, I tried to find an insect that was similar in shape and form to the original. The wētā–a large flightless cricket found in the land of hobbits (New Zealand)–served as my inspiration.

This image came from my favorite Dover Publication of them all, a treasure-trove titled, Animals: 1,419 Copyright-Free Illustrations of Mammals, Birds, Fish, Insects, etc.

Using the reference, I sketched variations of this corrosive critter.

Project Coordinator and Fellow Chinasaur Collector, Tim Beach, liked the below sketch, saying: “… make the tail a bit more T-shaped, rather than drooping, and color it.”

This re-imagining proved to be a pivotal one in this monster’s legacy as all renditions in subsequent releases of the game, including fifth edition, were variations of my wētā-inspired design. Wow.

ILLUSTRATION #22: BuletteOur second Chinasaur-inspired beast is the Landshark or Bulette (pronounced “boo-lay” by the monster’s creator and Dragon magazine editor, Tim Kask, but “bullet” by D&D creator Gary Gygax). This fearsome subterranean hunter was not present in the early editions of the game but, instead, made its debut in the premiere issue of Dragon in June 1976.

Here’s Tim Kask talking about the monster’s origin in more detail:

As I’d done with the Rust Monster, I went for an interpretation drawn from the natural world, going so far as to add orca-like markings.

…which Tim Beach preferred over a design I’d previously done for the Dragon Mountain adventure (below), saying, “I like the shark-like face of your Bulette… the crest needs to be flexible, and he needs armor… try it more like the original.”

By mid-February I’d sent a revised sketch, which Tim felt was “pretty good”, adding: “Shorten the legs by at least a third, maybe even half. The crest still needs to be flexible at the bottom. It’s like a segment of shell that it lifts when excited (to give it a weakness for player-characters to take advantage of). The back of it is hollow (looks kind of like a pointed band-shell from the back), and the bulette is able to lay the crest down, almost to the body. The armor and head are excellent.”

I carried out Tim’s requests and delivered exactly what he wanted. He was so pleased with this take that he purchased the original artwork from me. High praise indeed!

The final monster conjured into D&D from cheap plastic toys is everyone’s favorite hugger, the Owlbear.

Though it is clear that David Sutherland’s illustration from the Monster Manual is derived from the figure, the original edition of D&D had a more literal illustration by Greg Bell. And yet, Gygax seems to be describing the toy, saying: “…bodies are furry, tending towards feathers over the cranial region…”

It is unclear why there was a change but the Chinasaur-inspired design appeared in modules and products throughout the 1980s, as seen in Jim Roslof’s epic opening illustration from the 1979 adventure module, The Keep on the Borderlands.

Despite my deep love for this beast, there were no Owlbear drawings in my ’92 sketchbook. Tim and I had a conversation about it, where he directed me to: “Remember the bear-like posture we discussed; up pose maybe between all-fours and upright, as if it were lifting up a little to sniff the air?”

I tried to draw this pose but couldn’t capture what Tim wanted. As it was with the others, I went for a more natural take, referencing a Black Bear for the body pose and a Golden Eagle for the head:

…to arrive at this:

Tim thought it was “good” and added: “I wouldn’t mind seeing the front claw raised to strike, but don’t worry about it if it will throw off the rest of him. Owlbears have tails; add one as indicated by marks on the sketch.” Which I must have added to the above sketch before laser printing it onto bond paper for coloring.

For whatever reason, I did not raise the front paw. It may have been an oversight on my part as I raced to keep the pace of completing two finished pieces a day in order to make the deadline. I still had many more classic D&D monsters to draw, like…

ILLUSTRATION #292: Umber Hulk

“Umber hulks seem to disappear or spring up…at will and always take great care in hiding their tunnels behind them.”

–Monstrous Manual, page 352

Tim Kask has said that the Umber Hulk’s origins also came from a plastic toy that Gary had in a “bag of stuff”. Many have speculated that this pincer dragon below is the inspiration but, given that David Sutherland’s illustrations are so faithful to their toy counterparts, I remain dubious.

And, if so, Gygax’s original description in the Greyhawk supplement doesn’t align: “Typically they are 8′ tall, 5′ wide, with heads resembling bushel baskets, and gaping maws flanked by pairs of exceedingly sharp mandibles.” Here is the Umber Hulk’s pictorial debut from Dave Arneson’s Blackmoor, published in 1975:

The above, another illustration by Sutherland, looks more like it was taken from a comic book than a plastic toy.

In my correspondence with Tim Kask back in 2013 (for my Chinasaur article) he maintained the Umber Hulk was based on a toy but NOT the pincer-dragon-Chinasaur. I scoured the internet, showing him photos of similar toys, like the Ultraman Kaiju Antlar, but none were a match.

My suspicion is that Kask’s memory may be fuzzy. After all, these events happened nearly 50 years ago! He also revealed that the Purple Worm and Carrion Crawler came from plastic toys but I have yet to locate anything that resembles either of them. Perhaps those two were based on rubber jigglers—toy prizes commonly found in gumball vending machines back then—or just simple rubber fishing lures. But I’ve digressed…

My take: I think Sutherland may have cobbled together a custom miniature (as he had done with the Ogre, Troll and even a dragon) or, possibly, based the head design on the giant ants from the classic 1954 film, Them! The distinct open maw on the giant ant puppet is quite similar to that first Umber Hulk drawing from ’75.

Indulge me a bit more: this scene from the film pretty much shows what it’d be like to descend into an underground lair and experience an Umber Hulk attack. Get your fireball spells ready!

Regardless, my 1992 rendition of this subterranean brute was inspired by another crustacean of cinema–the Garthim from 1982’s The Dark Crystal.

Tim Beach liked this sketch and the final artwork was shipped off in the first batch to TSR at the end of February, 1993.

The Beholder, also known as the “Sphere of Many Eyes” or “Eye Tyrant”, is one of the most iconic monsters in the game’s 50-year history and, like rest of these beasties, was introduced in the Greyhawk supplement right smack on the cover.

Unlike many of the other monsters I’ve discussed, the Beholder is an original creation and not based on a creature from mythology or other fiction. Terry Kuntz, conceived the idea and Gygax detailed it for publication. Both Terry and his brother Rob were fellow gamers who played with Gygax and Arneson on early iterations of D&D, and would go on to join the burgeoning TSR staff.

But the image most of us 80’s kids know is Tom Wham‘s humorous drawing for the Monster Manual.

I loved this image as a kid. I love it now. It brings to mind the art of underground comics by the likes of Robert Crumb or even 1960s Rubber Uglies trading cards.

My ’92 sketchbook had a bunch of Beholder doodles, including one inaccurately portraying an encounter above ground. Tim noted from the onset: “Generally speaking, now is not the time to develop new takes on old creatures. In some cases, there are options, though, and you can be creative–with approval. Please check with me before you try anything really wild. This applies more stringently to the ‘classic’ AD&D monsters. For instance, though your sketchbook version of beholders would be fine for a module, stick to the ‘standard’ as far as size and shape of mouth, eyes, etc.”

So that is exactly what I did.

You’ll note that there are some Beholder-Kin drawings collaged into my sketchbook and a side view of the Beholder, which was used for the group shot:

* This is another original I no longer own, so the colors are inaccurate. At least you can see more detail than in the published book.

My favorite part of the Beholder-Kin illustration was the opportunity to render different pupil shapes, pulling inspiration from goats, geckos and an octopus (for the Eye of the Deep).

As for the second image of Beholder Kin, I no longer own the original or a laser copy. It’s not a favorite of mine, as it was a lot of strange shapes to be assembled in a single piece (like the Elemental-Kin). Though I wasn’t excited about that illustration I was thrilled that I had the opportunity to render a true D&D legend.

ILLUSTRATION #48: Displacer BeastOur last classic creature is the Displacer Beast, another favorite of mine from childhood.

The displacer beast was first described as “a puma-like creature with six legs and a pair of tentacles which grow from its shoulders.” This cool concept was “burrowed” from a 1939 short story by A.E. Van Vogt, Black Destroyer, later collected in the novel The Voyage of the Space Beagle. His extraterrestrial creature was named the coeurl.

David Trampier’s illustration in the ’77 Monster Manual may have been influenced by the Marvel Comics 1974 adaptation of Vogt’s story.

My ’92 sketchbook had an ink drawing and a test for my coloring method using a laser copy of the line work. Tim’s only note was to give the beast six legs, instead of four, as described.

Referencing my Animals book, I proceeded to final art. Can you tell which one I used? (Hint: it’s 3 feet away from where you think it is.)

Tim, and the rest of the TSR team, were happy with this rendition, as was I. This particular piece had a presence that gave the lifelike illusion that this animal could exist in some alternate reality. The seeds of a realistically detailed yet fantastic field guide were germinating in my mind…

Coming up, nature continues to inspire me as I set out to illustrate D&D’s iconic reptile and fish folk.

Next: Part 7: Lizardmen and Fish FolkJune 14, 2024

Behind The ‘Monstrous Manual’: PART 5

We enter the enchanting fairytale world of sprites, sylphs, gnomes and other fae folk in this installment of ‘Behind The Monstrous Manual’. Previously, I spoke about mythology, folklore and J.R.R. Tolkien’s classic books, The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings trilogy influencing Gary Gygax and his designers when creating Dungeons & Dragons in the 1970s.

ILLUSTRATION # 145: Hobbit Halfling“Why is it called a halfling when it is clearly a hobbit?” you ask. Well, this race of half-sized humans were referred to as hobbits in the early printings of D&D…that is until TSR received a warning from the rights owner of Tolkien’s Estate. As Gygax recounted in 2002:

“TSR was served with papers threatening damages to the tune of half a mil by the Saul Zantes (sp?) [Tony here, he’s referring to Saul Zaentz] division of Elan Merchandising on behalf of the Tolkien Estate. The main objection was to the boardgame we were publishing, The Battle of Five Armies. The author of that game had given us a letter from his attorney claiming the work was grandfathered because it was published after the copyrights for JRRT’s works had lapsed and before any renewals were made. The action also demanded we remove balrog, dragon, dwarf, elf, ent, goblin, hobbit, orc, and warg from the D&D game. Although only balrog and warg were unique names we agreed to hobbit as well, kept the rest, of course. The boardgame was dumped, and thus the suit was settled out of court at that.”

…and there you have it. Apparently, amongst the designers at TSR during production of the Monstrous Manual, there was debate on whether halflings had pointed ears or not. Project Coordinator and Creature Catcher, Tim Beach, noted: “Your halflings on page 62 are good, but like we talked about, cover up the ear so we don’t see if it is pointed or not.”

Although I was a fan of the Rankin & Bass 1977 production of The Hobbit, I tried for a less exaggerated, more serious take, as per Tim’s initial notes to me at the onset. I’d previously thought the original artwork of the halfling was sold off but uncovered it tucked amongst some files while researching for this article! A treasure rediscovered, worthy of Gollum’s greed.

ILLUSTRATIONS #130 & #131: GnomeThroughout my career, I’ve talked about my obsession with famed fairy artist Brian Froud. His 1978 book, Faeries, blew my 10-year-old mind when mom brought it home from the bookstore. The mind-blowing continued when I saw his earthy, grotesque drawings come to life in Jim Henson’s 1982 film The Dark Crystal. Certainly, The Spiderwick Chronicles wouldn’t exist if it hadn’t been for Froud’s influence. A particular favorite of mine was his painting of the Irish spirit, the Fear Dearg:

There’s just so much awesome here I can hardly take it all in! The Dearg’s tattered, patchwork jacket inspired Hogsqueal’s attire, seen here:

But a decade before Spiderwick, Froud’s iconic illustration also inspired this sketch, of a gnomish self-portrait in November, 1992:

Tim loved this drawing, saying: “He’s perfect; ink him and color him.”

As I’d done with Medusa, for this final piece, I colored a black & white laser copy of the ink drawing instead of directly on it. This was because I was uncertain of the color palette and wanted the ability to explore my options (as well as not having it end up too close to Froud’s art). If I did indeed color up alternate versions, I have no record of them. Ultimately, I decided on teal-colored robes.

The gnome illusionist’s hat, a WWII military garrison cap, came from another wizard…a Pinball Wizard:

Elton John was sporting an array of gaudy garrison-style caps during the early 1990s. They were so unusual, I just had to incorporate one in my art.

Besides, the garrison cap wearing illusionist, there was a second entry in the Monstrous Manual: the Tinker Gnome.

His pose was taken from an engraving from yet another Dover Publications book, Men: A Pictorial Archive from Nineteenth-Century Sources.

Like the illusionist, the pencil drawing was also laser copied onto paper then colored. I was experimenting on the fly and wanted options. If the colored sketch was too soft and didn’t work, I still had the original that I could ink and finish. Today, I no longer own the artwork (or even a decent laser copy) but it looks like I did ink the piece in the end. If only I had some of that gnomish magic to conjure up a decent scan…

ILLUSTRATION #271: Sprite

“Normal sprites have distinctly elven features.”

—Monstrous Manual, p. 328

I utilized the same sketch-to-laser-copy method for the sprite as well, although the design for this li’l fella started in 1992 as an exploration of elven attire, drawn while preparing my art submission to TSR.

Tim approved this design, once I added (cicada) wings, changed the dagger to a longsword, and adjusted the angle of the ears.

The unique costuming came from the French artist, Erté, whose elegant yet graphic, Art Deco-inspired designs were sophisticated in the same way that I imagined elven culture. My introduction to Erté’s work was a collection of his fashion drawings that I’d found in a used bookshop. Back then, I was always on the hunt for a new Dover book to add to my collection.

And, speaking of Dover’s books, the next three entries started with copyright-free images from this gem:

Is the cover meant to be a diagram of a woman’s mind? Is this where Pixar got the idea for Inside Out?

ILLUSTRATION #82: Elemental, Air KinThe sylph, a mythological, elemental spirit of the air, made its D&D debut in the 1977 Monster Manual. I was excited to draw this one. Again, inspired by the artistry and brilliance of Brain Froud, I sketched out a traditional depiction of a fairy, complete with dragonfly wings.

Tim liked this sketch but had me add a little more of her “diaphonous robes” before going to final. Her pose and clothing were referenced from this image:

As you may notice from my sketch, I had not planned to have the Aerial Servant (aka Cloud Guy) behind her. You see, originally the “Elemental-Kin”, like the other “Elemental” entries, were each to be separate illustrations, but Tim asked that they be combined due to limited page space.

I resisted this request. Tim replied, “It would probably be better to put critters together when the illo calls for two of them. Why can’t you see the salamander with a fire snake? They work together sometimes. I’d prefer the elemental kin together…”

My reasoning was that, unlike the serpentine salamander and fire snakes, the other pairings were mismatched shape-wise and, therefore; clunky when placed in a composition together.

Truth be told, I did not yet possess the skills to pair them in a creative way, which is why I wasn’t happy with this request. My frustration manifested into me rushing to finish the sylph piece and move on, which is why I never detailed the final art (you’ll note her feet are poorly rendered). I’d envisioned this image as a single figure and felt Cloud Guy ruined it. But I knew I’d have another opportunity to draw a fairy type with my illustration of the nymph.

ILLUSTRATION #224: Nymph

“If the nymph disrobes, the onlooker will die unless a saving throw versus spell is successful.”

—Monstrous Manual, p. 270

Like the sylph, the nymph is first listed in the Monster Manual, but not shown. However, thanks to centuries of art history, when I think of this beautiful nature deity, my mind is flooded with classical imagery from legendary painters like John William Waterhouse and William-Adolphe Bouguereau.

I had an idea of posing the nymph like an ancient Greek marble statue.

Using additional reference from my copy of Women: A Pictorial Archive from Nineteenth-Century Sources , I completed this piece…

…but it didn’t work. It looked like she was toweling off after a bath. I could do better. I could create an alluring image, in line with the depictions I’d seen in those classical paintings. After hunting about for inspiration, I found the perfect pose, right smack on the cover of my life drawing handbook from art school…

…and began sketching.

For the final art, I elongated her features. More fairy. Less human.

…but it didn’t work for TSR. As Tim said on February 25th, 1993, “Sigh. Wonderful piece but management has decided firmly, ‘no nudity’… because our company is the focus of anti-gaming material, we have to stay cleaner than all the others, and our code of ethics is clear on this. Sorry.”

I countered that, due to the pose, I didn’t reveal anything but Tim replied that she couldn’t be naked when she stood up. Okay. Fair enough.

I loved this piece and did not want to slather white paint all over it. Also, the deadline was fast approaching. So, instead of redoing the art a third time, I opted to paint on a color laser copy of this piece. I submitted the revision but still it wasn’t acceptable. Tim elaborated, “My boss, Tim Brown, asked me to save his job and get her covered up a little more. We like her but I’d have to agree that the illustration could cause some problems with our enforced PG-13 rating.” Tim went on to instruct exactly how much covering up I needed to do. I did what I was asked but was disappointed with the final printed image.

I was new to this type of compromise–that is, altering a finished piece of art that I really cared about. This wasn’t a school assignment, where I’d make the changes to score a better grade, it was a book that (as Tim said) we hoped would remain in print, “…for a number of years.” It had to be the best art I was capable of creating.

Over time, I’d learn how to collaborate with others and still satisfy my inclinations and personal goals. When I look back, I realize my experience working for TSR was my on-the-job training for the future book projects that were little more than daydreams back in 1993.

ILLUSTRATION #78: DryadUnlike the previous two fairies, the process for creating the dryad was as easy as picking wildflowers…well, without thorns, stinging insects or poison ivy.

The finished piece was completed in the first batch of finished art and colored over a laser print of the pencil sketch, to give it that soft line.

Some have pointed out that the spiked hair is a distinct characteristic of my interpretation of this mythical being. Truth be told, I was thinking of the Oona character from the 1985 film, Legend, who sported a similar style:

The pose and drapery, however, were (like the sylph and the first attempt of the nymph) taken from an exquisite woodcut engraving in that Women book I mentioned earlier.

Boy, oh boy, those Dover Publications were really helping me along with this project, especially with all the fantastic D&D animals I still had to draw. We’ll get to those next!

Next: PART 6: Monstrous FaunaJune 10, 2024

Behind The ‘Monstrous Manual’: PART 4

Moving beyond Parts 2 and 3 of fantasy humanoids, we’ll now take a look at a several monsters I had the opportunity to illustrate for the Dungeons & Dragons Monstrous Manual that have been celebrated for centuries in epic myths. We’re talking the Cyclops, Medusa, Minotaur and more!

ILLUSTRATION #44: Giant, CyclopsOur first monster was also part of my submission to TSR in 1992. Actually, it was my second, followup, submission. You see, originally I’d sent Art Director Peggy Cooper (seen here) a pile of monster and character drawings–which didn’t score me any work because I didn’t show whether I could actually illustrate scenarios required for an adventure: characters fighting monsters, characters finding treasure, setting off traps, etc.

I listened to Peggy’s guidance and sent in new samples within 2 weeks. Unbeknownst to me, this showed her that I could not only take direction but meet a deadline–key traits required for a freelance illustrator. My second submission impressed her and she took and chance with this Florida kid, fresh outta art school, hungry for work. Peggy changed my life.

Though my ambition had won the day, I still had a lot to learn. D&D, like any good story, isn’t just about characters: the setting, artifacts, lighting, emotion and more convey important information to the players and Dungeon Master. You’re showing them what this experience could feel like.

But for me, I struggled with depicting action scenes. Maybe that’s why I steered away from trying my hand at superhero comics. Instead, staged moments–by the likes of Norman Rockwell or J.C. Leyendecker–that told story through acting and props sparked my artistic drive. You can see it in The Secret Staff illustration above…”But,” you say, “Cyclops Point, on the left page, has action.” True. But I didn’t create that scene. It was lifted it from one of my heroes, Mike Kaluta, in his epic comic, Starstruck.

Kaluta, along with William Stout, Bernie Wrightson and Charles Vess created comics that hearkened back to the Golden Age of Illustration (1880s-1930s). Among them, Mike Kaluta is a legend. I’ve learned a lot from studying his work and (years later) hanging out to talk shop. I even connected Mike with the D&D art team back in 2000 for the 3rd edition Monster Manual, where he contributed a few pieces! Talk about a full circle moment.

Of course, I would have never allowed my submission to be published. I was just trying on another artist’s brain to figure out how they worked. It’s how I learn. I still do exercises like this today. I am still learning…still trying to become a better illustrator.

Tim approved my submission piece for the mythical Cyclopskin. I redrew it and changed the pose. His expression completely captures the overwhelming and dumbstruck feeling I’d felt back then that I was actually getting paid to do this. All he needed was a handful of markers and pens balled in his fist.

Although I did not illustrate the other giant entries, Tim intended for me to contribute to the smaller Giant-Kin: the Cyclops and the Ettin. Possibly as an oversight on Tim’s part, the Ettin was assigned and completed by Jeff Butler, who was illustrating all the giants. Of course I did not know this and sent in my finished Ettin.

…But due to that mix-up, he never made it in the final book (which is why he is so grumpy). This design was based on a drawing from my 1992 sketchbook, along with doodles of halfling faces…and illuminates how my younger brother’s head was shaped exactly like a light bulb.

Present since the first edition of the game, Medusa has always fascinated me, especially after seeing Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion marvel, Clash of the Titans.

If we look back to that first submission (the one where I just drew monsters hanging around, doing nothing), you’ll see I included a portrait of Medusa.

As mentioned previously, Project Coordinator and Monster Wrangler, Tim Beach, loved my interpretation of this fearful gorgon, adding: “We like the snake ponytail; shorten the ears by about half.”

I’d love to say that my unique take, of styling a topknot full of slender snakes, just popped into my head and onto paper in one instant but it required some exploration.

To save time, I laser copied the original ink drawing from my submission, pasted it onto a new sheet of 11×17″ paper and added her extended right hand holding the dagger sheath.

This line drawing was laser copied onto an 8.5×11″ sheet of paper, then colored (a technique I would use on several other images, including the Cockatrice, Rakshasa and Mindflayer).

This piece was a favorite of mine and Tim’s. We went back and forth trying to the get all the details just right. The above color laser copy is not the final image. Tim had a few more tweaks before I sent off the artwork: “After some more late debate (with the production team), we decided a couple of things. First, the ears need to be bobbed a bit, at least the part above her forehead snakeline. Pointed is still okay, but not so long and sharp. Second, the description says she has glowing red eyes. We can rationalize our way out of this, by saying her petrification is voluntary, and her eyes glow when she uses it. In other words, it would be nice to be consistent with the text, but we won’t push it if it doesn’t fit your color scheme. Finally, the forearms are a bit spindly, but tolerable. How about some light scales on her stomach? I like the way the bottom is left ambiguous, so she could have a snake body or human legs.”

In the end, I did adjust the ears, add some reddish glow around the eyes and the scaling. Unfortunately, I no longer own the original so you’ll have to compare this with the printed image in the book.

Also, as with several other designs in the Monstrous Manual, my rendition of Medusa was sculpted (by the late Geoff Valley) as a miniature for Ral Partha and released shortly after publication. That was really cool.

Although I was quite aware of the serpent-like spirit of Asian myth, there were no naga (or, more accurately, nagini) drawings in my ’92 sketchbook. I was familiar with David Sutherland’s illustration from the Monster Manual and a plastic toy I had since the 80s, manufactured by the company Dimensions for Children from one of their epic fantasy playsets. (They would later be sent a Cease & Desist by TSR.)

Now, growing up in south Florida, I’d seen my share of lizards, snakes, turtles and alligators. I had several handy guidebooks to help identify what was slithering, crawling and creeping while I was camping, hiking, mowing the lawn, taking out the trash, etc.

A photograph of a Western Rattlesnake in my copy of the Audubon Society Pocket Guide served as the reference for the naga illustration, as can be seen in the sketches below.