Behind The ‘Monstrous Manual’: PART 6

I’m highlighting some classic, iconic monsters of Dungeons & Dragons that I had the opportunity to illustrate back in 1993 for the Monstrous Manual

The Fauna of D&D

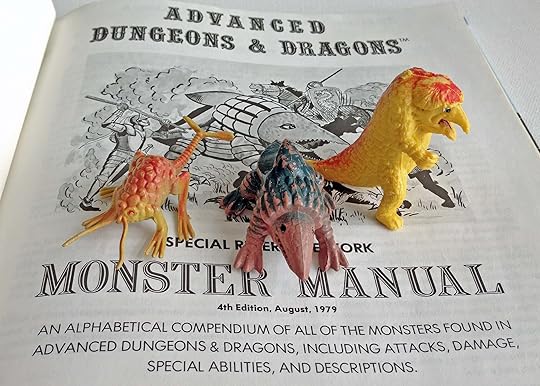

The Fauna of D&DWe’ve covered literary-inspired humanoids, monsters of myth and even the fae folk of fairy tales, but this entry is all about creatures that are unique to the game when they made their debut in the 1975 Greyhawk supplement…even though, they too, had their roots from outside sources, like these toys from Hong Kong which inspired three major beasties:

ILLUSTRATION #252: Rust MonsterLike many, I played with “Chinasaurs”, the plastic figures often found in toy aisles of general stores during the 1970s-80s. In fact, I wrote a detailed article about their transformation from Ultraman knockoffs to the stuff of gaming legend.

Though the Rust Monster was listed in the Greyhawk supplement there was no accompanying art. That would come a few years later in the Monster Manual, where we see a clear connection to the toy in David Sutherland’s iconic illustration.

When I attempted my rendition in 1992, I tried to find an insect that was similar in shape and form to the original. The wētā–a large flightless cricket found in the land of hobbits (New Zealand)–served as my inspiration.

This image came from my favorite Dover Publication of them all, a treasure-trove titled, Animals: 1,419 Copyright-Free Illustrations of Mammals, Birds, Fish, Insects, etc.

Using the reference, I sketched variations of this corrosive critter.

Project Coordinator and Fellow Chinasaur Collector, Tim Beach, liked the below sketch, saying: “… make the tail a bit more T-shaped, rather than drooping, and color it.”

This re-imagining proved to be a pivotal one in this monster’s legacy as all renditions in subsequent releases of the game, including fifth edition, were variations of my wētā-inspired design. Wow.

ILLUSTRATION #22: BuletteOur second Chinasaur-inspired beast is the Landshark or Bulette (pronounced “boo-lay” by the monster’s creator and Dragon magazine editor, Tim Kask, but “bullet” by D&D creator Gary Gygax). This fearsome subterranean hunter was not present in the early editions of the game but, instead, made its debut in the premiere issue of Dragon in June 1976.

Here’s Tim Kask talking about the monster’s origin in more detail:

As I’d done with the Rust Monster, I went for an interpretation drawn from the natural world, going so far as to add orca-like markings.

…which Tim Beach preferred over a design I’d previously done for the Dragon Mountain adventure (below), saying, “I like the shark-like face of your Bulette… the crest needs to be flexible, and he needs armor… try it more like the original.”

By mid-February I’d sent a revised sketch, which Tim felt was “pretty good”, adding: “Shorten the legs by at least a third, maybe even half. The crest still needs to be flexible at the bottom. It’s like a segment of shell that it lifts when excited (to give it a weakness for player-characters to take advantage of). The back of it is hollow (looks kind of like a pointed band-shell from the back), and the bulette is able to lay the crest down, almost to the body. The armor and head are excellent.”

I carried out Tim’s requests and delivered exactly what he wanted. He was so pleased with this take that he purchased the original artwork from me. High praise indeed!

The final monster conjured into D&D from cheap plastic toys is everyone’s favorite hugger, the Owlbear.

Though it is clear that David Sutherland’s illustration from the Monster Manual is derived from the figure, the original edition of D&D had a more literal illustration by Greg Bell. And yet, Gygax seems to be describing the toy, saying: “…bodies are furry, tending towards feathers over the cranial region…”

It is unclear why there was a change but the Chinasaur-inspired design appeared in modules and products throughout the 1980s, as seen in Jim Roslof’s epic opening illustration from the 1979 adventure module, The Keep on the Borderlands.

Despite my deep love for this beast, there were no Owlbear drawings in my ’92 sketchbook. Tim and I had a conversation about it, where he directed me to: “Remember the bear-like posture we discussed; up pose maybe between all-fours and upright, as if it were lifting up a little to sniff the air?”

I tried to draw this pose but couldn’t capture what Tim wanted. As it was with the others, I went for a more natural take, referencing a Black Bear for the body pose and a Golden Eagle for the head:

…to arrive at this:

Tim thought it was “good” and added: “I wouldn’t mind seeing the front claw raised to strike, but don’t worry about it if it will throw off the rest of him. Owlbears have tails; add one as indicated by marks on the sketch.” Which I must have added to the above sketch before laser printing it onto bond paper for coloring.

For whatever reason, I did not raise the front paw. It may have been an oversight on my part as I raced to keep the pace of completing two finished pieces a day in order to make the deadline. I still had many more classic D&D monsters to draw, like…

ILLUSTRATION #292: Umber Hulk

“Umber hulks seem to disappear or spring up…at will and always take great care in hiding their tunnels behind them.”

–Monstrous Manual, page 352

Tim Kask has said that the Umber Hulk’s origins also came from a plastic toy that Gary had in a “bag of stuff”. Many have speculated that this pincer dragon below is the inspiration but, given that David Sutherland’s illustrations are so faithful to their toy counterparts, I remain dubious.

And, if so, Gygax’s original description in the Greyhawk supplement doesn’t align: “Typically they are 8′ tall, 5′ wide, with heads resembling bushel baskets, and gaping maws flanked by pairs of exceedingly sharp mandibles.” Here is the Umber Hulk’s pictorial debut from Dave Arneson’s Blackmoor, published in 1975:

The above, another illustration by Sutherland, looks more like it was taken from a comic book than a plastic toy.

In my correspondence with Tim Kask back in 2013 (for my Chinasaur article) he maintained the Umber Hulk was based on a toy but NOT the pincer-dragon-Chinasaur. I scoured the internet, showing him photos of similar toys, like the Ultraman Kaiju Antlar, but none were a match.

My suspicion is that Kask’s memory may be fuzzy. After all, these events happened nearly 50 years ago! He also revealed that the Purple Worm and Carrion Crawler came from plastic toys but I have yet to locate anything that resembles either of them. Perhaps those two were based on rubber jigglers—toy prizes commonly found in gumball vending machines back then—or just simple rubber fishing lures. But I’ve digressed…

My take: I think Sutherland may have cobbled together a custom miniature (as he had done with the Ogre, Troll and even a dragon) or, possibly, based the head design on the giant ants from the classic 1954 film, Them! The distinct open maw on the giant ant puppet is quite similar to that first Umber Hulk drawing from ’75.

Indulge me a bit more: this scene from the film pretty much shows what it’d be like to descend into an underground lair and experience an Umber Hulk attack. Get your fireball spells ready!

Regardless, my 1992 rendition of this subterranean brute was inspired by another crustacean of cinema–the Garthim from 1982’s The Dark Crystal.

Tim Beach liked this sketch and the final artwork was shipped off in the first batch to TSR at the end of February, 1993.

The Beholder, also known as the “Sphere of Many Eyes” or “Eye Tyrant”, is one of the most iconic monsters in the game’s 50-year history and, like rest of these beasties, was introduced in the Greyhawk supplement right smack on the cover.

Unlike many of the other monsters I’ve discussed, the Beholder is an original creation and not based on a creature from mythology or other fiction. Terry Kuntz, conceived the idea and Gygax detailed it for publication. Both Terry and his brother Rob were fellow gamers who played with Gygax and Arneson on early iterations of D&D, and would go on to join the burgeoning TSR staff.

But the image most of us 80’s kids know is Tom Wham‘s humorous drawing for the Monster Manual.

I loved this image as a kid. I love it now. It brings to mind the art of underground comics by the likes of Robert Crumb or even 1960s Rubber Uglies trading cards.

My ’92 sketchbook had a bunch of Beholder doodles, including one inaccurately portraying an encounter above ground. Tim noted from the onset: “Generally speaking, now is not the time to develop new takes on old creatures. In some cases, there are options, though, and you can be creative–with approval. Please check with me before you try anything really wild. This applies more stringently to the ‘classic’ AD&D monsters. For instance, though your sketchbook version of beholders would be fine for a module, stick to the ‘standard’ as far as size and shape of mouth, eyes, etc.”

So that is exactly what I did.

You’ll note that there are some Beholder-Kin drawings collaged into my sketchbook and a side view of the Beholder, which was used for the group shot:

* This is another original I no longer own, so the colors are inaccurate. At least you can see more detail than in the published book.

My favorite part of the Beholder-Kin illustration was the opportunity to render different pupil shapes, pulling inspiration from goats, geckos and an octopus (for the Eye of the Deep).

As for the second image of Beholder Kin, I no longer own the original or a laser copy. It’s not a favorite of mine, as it was a lot of strange shapes to be assembled in a single piece (like the Elemental-Kin). Though I wasn’t excited about that illustration I was thrilled that I had the opportunity to render a true D&D legend.

ILLUSTRATION #48: Displacer BeastOur last classic creature is the Displacer Beast, another favorite of mine from childhood.

The displacer beast was first described as “a puma-like creature with six legs and a pair of tentacles which grow from its shoulders.” This cool concept was “burrowed” from a 1939 short story by A.E. Van Vogt, Black Destroyer, later collected in the novel The Voyage of the Space Beagle. His extraterrestrial creature was named the coeurl.

David Trampier’s illustration in the ’77 Monster Manual may have been influenced by the Marvel Comics 1974 adaptation of Vogt’s story.

My ’92 sketchbook had an ink drawing and a test for my coloring method using a laser copy of the line work. Tim’s only note was to give the beast six legs, instead of four, as described.

Referencing my Animals book, I proceeded to final art. Can you tell which one I used? (Hint: it’s 3 feet away from where you think it is.)

Tim, and the rest of the TSR team, were happy with this rendition, as was I. This particular piece had a presence that gave the lifelike illusion that this animal could exist in some alternate reality. The seeds of a realistically detailed yet fantastic field guide were germinating in my mind…

Coming up, nature continues to inspire me as I set out to illustrate D&D’s iconic reptile and fish folk.

Next: Part 7: Lizardmen and Fish Folk