Dermott Hayes's Blog: Postcard from a Pigeon, page 82

March 13, 2016

Unfathomed Wonders

It was a soap smell, that’s what it was. He couldn’t pin it down. He was never good at that. People could tell the only soap ever touched his skin was the carbolic soap his mother scrubbed him with on a Friday night when he and his brothers got their weekly bath. Then he smelled like he’d been through a cattle dip.

She had the smell of soap, or, at least, what he thought was a soap smell. It was like soft, warm water and a gentle breeze in a field of blossoms, a spring meadow. He met her in Bertie’s Amusements, behind the fish’n’chip shop, just off Main St.

He didn’t really ‘meet’ her. They didn’t exchange numbers or names. They never even spoke. She was buying candy floss from the stall by the door. He was pushing pennies into a machine that promised to pay him twenty or more, if only he could manoeuvre his coins so they landed where the big metal sweeper would push the rest into the tray below.

She was wearing a yellow dress that matched her unruly shock of curly blonde hair, set off by the deep tan colour of her skin. Her two friends wore shorts and teeshirts. They were a cacophony of giggles and chatter.

He gave up on the machine and decided to walk up the town where he could stare at the gew gaws and gadgets in the shop windows and listen to the night sounds of the town before he went home. She stepped back from the candy floss counter just as he was leaving. They bumped. She got a faceful of fluffy, sticky, pink sugar. He got a smell of her and red hot ears.

She squealed. Her friends giggled more. He ran away.

Two days went by before he saw her again. He wasn’t avoiding her. It was a small town and there was only so many things you could do, places you could go. He didn’t have any friends there. His cousins were too old and worked in his uncle’s factory. Two weeks in a seaside town is every boy’s dream, isn’t it?

He did dream about it before he was packed off on the bus for the twenty mile trip from the city. His mother packed his bag and slipped an orange ten shilling note into his hand as she saw him on the bus. She kissed his head and told him to mind himself. Then she spoke to the driver and told him he’d be picked up by his uncle at the station on the other end. It was his first time away on his own. He waved at his Mammy and pushed back the tears, as the bus pulled away. He sat alone and stared at the bright orange ten shilling note.

She was playing golf on the putting green down by the shore. She wasn’t wearing the yellow dress but he recognised her hair. She was with the same two friends and he guessed they were sisters, maybe even twins. They dressed alike and both had lank manes of nut brown, shoulder length hair. All three of them wore shorts and flip flops. She wore a blue teeshirt.

He wanted to play, too, just to get near her, to find some excuse to speak to her. Then the terror of that struck him. His ears got hot again. No words would form in his head. Paying sixpence to go putting alone was out of the question; it was either an indulgent extravagance or pathetic. Either way, the local boys, who all knew him to see and never seemed to play on the putting green but were always there, because it was near the amusements and the beach, well, they’d jeer him for being a show off or a billy-no-mates.

Anyway, he told himself, he was carrying a sack of periwinkles he’d just picked and putting with them would be silly. So he walked on home past the putting green and its wire enclosure. He stared at his feet and felt his cheeks burn as he passed the ninth hole which her party was negotiating. Then her friends saw him and they began a chorus of jeers and giggles, as they teased and goaded her and he looked up, a swift, surreptitious glance and their eyes met. He stumbled, periwinkles spilled from his bag and ignoring them, he ran, feeling tears sting his eyes.

Later, he forgot the stumble and the periwinkles but he remembered her eyes. He remembered that moment when their eyes met. He ignored the amusement there, the mocking jeer at a gauche boy. There was only those eyes, the promise and pledge of unfathomed wonders, the mystery of all he didn’t know but always, unbeknown before, had longed for.

He spent the afternoon in the front room of his aunt’s house, stacking Beatles’ LPs on the family gramophone. He loved that machine, a modern marvel in a lush walnut and cherry cabinet and a radio spectrum with dials and magic names like Hilversum, Luxembourg and even Athlone. He loved it like it was a personal friend and confidant, it’s lacquered wood finish and scent of polish. But it was his cousins’ collection of Beatles’, Elvis Presley, Marty Robbins and Skeeter Davis albums that caught his interest. After lunch he feigned an upset tummy so his aunt let him stay at home while she went up the town to do her shopping. He knew this would take up half her day as she’d chat to her neighbours and catch up on gossip before she went to the chapel for afternoon prayers and confession on her way home.

So he swung back the arm and stacked With the Beatles, Please Please Me and Beatles for Sale on the stacking turntable, then set the arm to secure the stack, before clicking the lever and the first album dropped. These records were a treasure for him that glittered when he held them and gazed at their covers. Now they just mocked him. John Lennon goaded him, chanting ‘it won’t be long,’ and ‘all I’ve got to do,’ as if it were that easy. When Paul sang ‘till there was you’, he wanted to cry. He skipped to another LP and stared, wistfully, out the front room window until John sang, ‘I’m a loser’ and then he’d had enough. He turned off the gramophone, grabbed his jacket and ran out the door. He rushed from the house, ‘Words of Love’ ringing, tauntingly, in his ears.

On the street, he realised he had nowhere to go where he couldn’t see her face, her smile or hear her laugh. She haunted him through the town’s streets and lanes. He heard her order milk and a newspaper in the corner shop but when he turned around it was his aunt’s neighbour, Mrs McGavigan. He saw her reflection in the window of a passing bus but when he turned around she was nowhere to be seen. He cursed his lack of courage as he sat on the banks of the river, skimming flat stones across the surface of the calm water in the dark pool, where local fishermen cast enticing flies to catch brown trout. Then, sensing their displeasure, he gathered all his confusing sorrow and walked away, along the riverbank and towards the sea, to hide in the abandoned military fort that once filled his imagination with daring deeds. But now, its grim desolation and crumbling disorder made him shiver, not with cold, but an unfulfilled sense of loss.

The last time he saw her was on the last day of his holiday. His bus departed at six that evening so he got up early to pack his day with all the memories he could carry. Apart from two days in the first week when rain fell, the sun was always shining but that day was the hottest of them all. He rolled his swimming trunks in a towel and headed for the beach. He vowed to start his day with a dip, well, a paddle, really, then a walk in the dunes before he’d go to his favourite spot by the river. He’d have time to linger at the amusements, too, for a while.

The beach was packed. The local boys were diving noisily from the rocks beneath the high board. There was a natural, deep pool there when the tide was in and occasionally one of them would answer the jeers of his friends by climbing the ladder and taking the high plunge.

She was standing with her friends, the same two girls, Mary and Collette, the twins, by the ice cream stand. She was wearing a pink bikini; they wore matching turquoise blue swimsuits. She was holding a 99 in one hand. Her other hand was behind her back, half covering one cheek of her pink suited bottom.

Her name was Debbie. He learned that just the night before when he went to see the film in the local cinema, Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines. He was sitting alone, as usual, in the fourth row of the stalls, the thrupenny seats. She came in with her friends and he heard them giggling before he saw them. Then they were sitting in the row beside him and the twins, Mary and Collette, giggled as they pushed their friend, Debbie, into the seat beside him. There wasn’t much said while they watched the film but at the interval, when the girl came around with the ice lollies and the tubs of ice cream and they all got up to buy something, one of the twins, Collette he guessed, pulled his sleeve, giggling and asked his name. He was glad it was dark in the cinema and they couldn’t see him blushing but they’d all laughed together there and he didn’t feel so bad or tongue tied, so he told her and she introduced her sister, Mary and then, Debbie and their eyes met, again, before she looked down and away. They sat down again and watched the film and when it was all over, the girls went into the toilet and he waited around outside but left before they came out; afraid, suddenly, that had nothing to say or, if he had, was afraid to say it.

Down on the beach on that last day, being a non-swimmer and, embarrassed about that, he paddled and dipped in the shallows, far from the rocks and the diving board where the other boys dived and jeered each other. In the distance, he saw her step out of the water where she swam and for just a moment, a split second, she forgot the hand that protected her pink cheek and he could see why. There was a tiny hole, near the waistband and he caught a brief glimpse of white skin, untouched by the sun.

March 11, 2016

Brown Bread (a short story)

The smell of bread and baking woke him. It was familiar and comforting. He tried to sit up but didn’t move. Muffled voices crowded his mind. He couldn’t see them. When he tried to call out, he was silent.

A cold fear crept over him as he lay, wherever he lay. He didn’t know ‘where’ that was. He didn’t know why he was there. He didn’t know…who he was…he didn’t know how to move, speak, touch, see…images, distorted, disjointed, disoriented, crowded his mind. A snatch of a song…someone’s got it in for me…

He decided to concentrate on the smell of the bread. It reminded him of… Jesus, what? Then the screens came down again and he slid into a warm bath of dreams.

Home, for him, was the smell of baking bread.

In the kitchen of his home the aroma of freshly baked bread wrapped itself around you like a warm, fragrant blanket. It rose from the stove cooker in the scullery and from the top of the dresser by the kitchen window where his Mammy had laid out that day’s baking to sit and breathe.

As life passed by with a rhythmic beat, some things marked its inexorable passage. Fresh bread baking, dough rising, slices, warm from the oven and dripping with dollops of melting butter, these kept time for him.

He could discern the sour musk of buttermilk in the egg white glow of the soda bread, studded by raisins and sultanas that carried their own hum of fruity fermentation.

Beside it his Mammy had set the humble wheaten loaf, the family nutritional furnace, a carefully nurtured and kneaded eruption of coarse wheatmeal flour, the colour of warm coals.

This time when he awoke he was wet. He knew he was wet because it felt like his eyes were steaming up. He wasn’t sure if it was sweat or fever or both. Was he in a bath or tossed into a river, another body discarded, a wasted husk, with less than reverence for his soul’s sacred journey.

He tried to concentrate. He could feel a faint buffeting as though he was being rolled in a barrel of tripe. A muffled voice penetrated the blur of white noise crackle around his head.

‘If he lives, he’s a miracle but he’ll be scarred to the bone,’ the first voice said. I say ‘the first’ because as wakefulness took more control and honed his senses he became aware of a number of presences.

‘Will you keep your big mouth shut? he’s not dead or a vegetable. He’s in a coma. The poor lad might hear you. Lord knows what sort of suffering horrors he’s endured,’ said voice number two.

‘Excuse me. He’s not the only one…but right enough, he has enough on his plate without having to listen to me wittering on…he was a fine cut of a wee lad too,’ said voice one.

‘It’s always the youngest and the bravest go first…’ voice two, an older voice, trailed wistfully. He struggled to smell them, to catch some distinguishing odour. He smelled fruitcake…

Here was his mother’s magic, the fruits of her daily alchemic rituals. Her efforts went beyond food to sacred action as she assembled and arranged her instruments, jars, spoons and ingredients on the altar of the kitchen table.

Every morning after she had risen and fed the cats and the children and her husband and packed them all off on their respective paths to a sun trap patch beneath the garden hedge, to school or to work, she cleared the table and began her preparations.

A jug of buttermilk, covered with a thinning strip of muslin, was fetched from the dry,cool pantry alcove off the kitchen along with half a dozen sand shell coloured hen’s eggs.

A slab of fresh country butter was laid on the table with a tin of salt and a grocer’s bag of white sugar. Next came the red and white sack of Odlum’s plain flour and two small tins, one of Bextartar, the other of bread soda. Pride of place in the centre of this assembly was given to the sack of wheatmeal .

The instruments for the operation to follow were then gathered together at hand’s reach on the table. First the shiny butterscotch brown delph mixing bowl, then a wooden spoon, a teaspoon and an old ceramic handled kitchen knife, yellowed, cracked and curling with age. A wooden rolling pin was kept within reach.

He loved to sit and watch her work on chill, Autumnal evenings when the day’s curtains were drawn early and a spray of rain mist would keep him indoors after school.

She would pour him a glass of cold milk and, for a treat, butter a slice of warm raisin dashed soda bread which she’d sprinkle with sugar. She’d call it ‘a piece’, saying, ‘sit down there, wee man, and eat yer piece.’

He’d sit at the end of the kitchen table with only the fading light of the evening sun to illuminate her actions and listen to her sing songs that had caught her fancy like Que Sera, Sera and If I were a Blackbird.

His mind wandered. Or should that be strayed? He felt engulfed in a daydream. Surrounded by a liquid warmth that dulled his senses. So he could not move when he desired or speak or shout. He had no sight. He was aware his eyes were open. Vague noises: the rustle of starched cloth, the tinny clank of bedpans or dishes, the slosh of water filling a glass. He could feel the soft breath of damp air when a window was opened or a door slammed. Footsteps; some loud, hard and resolute, some shuffling, without direction. Voices, muffled and indistinct, some loud, some whispered. He opened his mouth to speak but he could hear no sound except a faint echo in a far recess…

Outside the evening gloom encroached slowly on the garden and the rain beat a sombre tattoo on the window. Inside was warm and safe and smelled of fresh baked bread and the salty treacle of melting butter.

Evening time was the time he loved best. The house had the cosy warmth of brushed cotton bedsheets that when combined with the aromatic blend of dry, country turf burning in the stove and the ambrosial scent of his Mammy’s baking created an indelible imprint of home in his mind that he could store in the recesses of memory when comfort, serenity and love were needed and he could recall them.

In these memories nothing had a time, just a place in the picture. So the pictures on the walls included a picture of Pope John XX111 alongside US President John F. Kennedy and Daddy’s framed version of Yeats’ poem, The Lake Isle of Inisfree.

A statue of the Virgin Mary as she appeared at the shrine at Knock stood in a bed of blue satin, encased in a gold painted frame over the kitchen door. The Blessed Virgin shared pride of place with St Martin de Porres, an ascetic Brazilian monk, to whom his Mammy had a particular devotion as Martin was the name of her husband.

In these memories the kitchen walls are always painted blue while the free standing dresser, painted two shades of green with the plates and the cups and the drawer of cutlery on the left and allsorts on the right side , stood inside the door to the back garden.

This dresser had six doors and two drawers. In the middle behind one big drop down door were shelves of tins of beans and boxes of marrowfat peas and supplies of dried herbs, spices like allspice, cloves and white pepper as well as all his mother’s baking magic, like baking soda, bread soda, Bextartar, colourings, vanilla essence and packets of raisins and sultanas and all those things that went into the Christmas cake mix like cherries, maraschino, green and red glace , mixed fruit peels and almonds, flaked, chipped and whole as well as coconut, chipped and dessicated.

The two doors above housed the dinner plates, saucers, side plates, dessert plates and cereal bowls for every day use while the teacups hung from hooks and the glasses stood ready for action and easy access. The best tableware was on display in the front room in a glass fronted cabinet.

Below the main drop down desk style door and work place the delph and glass mixing bowls and oven ready Pyrex bowls in different sizes were stacked behind two knee height doors alongside the steel cooking pots, frying pans, steamer, aluminium colander and wire sieve.

The kitchen floor was covered with linoleum in a woodcut diamond pattern. I imagined it was three dimensional when he stared at it long enough.

In those autumn evenings as he sat at the kitchen table, his sugared ‘piece’ in hand, he would listen to his mother’s gently absent minded crooning, ‘que sera, sera…whatever will be, will be…the future’s not mine to see,… que sera, sera…’

A noise, louder than the muffled rustling he had become accustomed to, shattered his reverie. Its thunderous rumble reverberated through his frame and where he lay. Screams, groans and the crash of shattered masonry followed. Then barked orders, shouted with the authority of fear and command.

A voice to his left said, ‘that was a close one. I think we took a hit…’

Another said, ‘Jesus, I’m bleeding. I think I’m hit.’ He sounded surprised.

In his bed, awake and conscious, he thought, or is this my nightmare? He strained to feel but all he could do was drift again…

You could set your watch by mammy, he thought. Her day’s work of washing and hanging out the clothes on the line in the garden; making the beds and dusting, baking and gardening over she would walk to the local shop to stock up on essentials for the tea and a visit to a neighbour for a wee cup of tea in her hand and a chat . By four o’clock she was ready to bake again and this was the time he loved best.

If she baked a sponge cake there’d be a chance to swipe his finger along the inside of big mixing bowl after she’d emptied its contents into the baking tin. The creamy, sugary mix pasted to the bowl was the prize for being there with her as she floured, kneaded and rolled . Sometimes it was Madeira cake or ‘coloured cake’ as he called it, a mesmerising kaleidoscope of colours, flavours and pungent, sweet aromas, cherry pink, chocolate brown and vanilla, a pale, delicate yellow.

Other times it was coffee cake and the bottle of Irel, a liquid chicory flavouring that gave the sponge and its creamy sandwich filler a rich, treacly coffee brown colour and taste.

Everyday she’d bake an apple tart when there were good cooking apples available from the tree in the garden at the back of the house. She’d lace it with cinnamon and dashed with cloves and then seal and paint it with country butter yellow egg yolk and coat it with white grain and castor sugar. He used to think his head would explode with the pleasure of swimming in the warm, sensory swirl of baking apples.

A putrid stench. He hadn’t realised he couldn’t smell until the acrid odour of steaming urine assailed his nostrils. Then he felt his whole face fill with a symphony of smells: sweaty socks, body odour, boiled cabbage, turgid faeces, disinfectant and bleach and a fetid reek of decay…the smell of cordite and exploded high calibre ordnance and the sweet, nauseating reek of burning flesh…

All these rushed into his brain, filling him up. Now he could hear and smell. He tried to combine both in his sensory deprived limbo. But his efforts were confused and pointless. Everything drained away again like waste from a sink. He struggled to hold on to something.

‘Here comes the shit,’ he thought. Was that a door opening? Were those the footsteps of a man or a woman? As soon as he could discern a movement he tried to concentrate on it to give it an attendant odour. But nothing stood still long enough to give it an identity. He felt tired and lost.

They were tying a rope to a branch of an old, gnarled blackthorn tree that stood on a ditch up the lane behind his house. It was mid-afternoon and a fine summer’s day.

The tree cast its big, curly shadow over the stream that skirted the field beyond the hedge. On our side the lane ran behind the squat row of houses.

The object of their adventure was the nest of wasps that had made their home in the dry, porous clay of the embankment just below the tree. Their mission, should they choose to accept it, as they’d declare solemnly to each other, was to swing from the embankment and kick the wasps’ nest on the inswinging return. In the way of things he took first turn while Hughie, his best friend, looked on.

Nothing happened on the first swing. The wasps went about their business, apparently unperturbed, hovering and buzzing in and out of the tiny wasp sized holes they had dug into the embankment.

Hughie, taller and heavier than he and with shoes that were three sizes bigger swung and hit the bank with a dull shudder. In his panic to escape he released the rope and leapt to his feet, dancing a bizarre dance by kicking his legs out while brushing them frantically with his arms. They could see more wasps had come out to investigate the disturbance.

Taking the rope, he swung again. His feet, like diving bomber planes rained death and destruction on the wasps. He imagined their tiny dwellings collapse and implode, crushing their numbers with sudden, terrifying death. The impressions of his feet were plainly visible in the embankment.

Releasing the rope the rope he knew there was no escape. At least two wasps had got off their chocks to swoop and harry the enemy. A sharp protruding stone split his shin as the wasps stung deep and bitter into the soft flesh behind his knee .

Tears welled up in his eyes and flowed fast like the blood staining his socks. He turned and ran.

There it is again, he thought. The smell of baking bread and apple tart with cinnamon and maybe fairy cakes with icing cream and hundreds of thousands.

He could hear a confusion of sounds. Somewhere close by a voice said, ‘nurse, I think yer man’s awake again…’ Running footsteps, raised voices, orders, ‘get a doctor…get a defib…’ He ignored them as they had ignored him.

He had run to the door as fast as his injuries would allow and his young legs could carry him. Now he was banging on it and the tears that had been welling burst their floodgates. He wanted the comfort of his mammy, a sugared piece, a plaster and a wee hug to wipe the fear away…

‘Mammy, mammy…let me in,’ he wailed. Then the door swung open and he was enveloped in the pungent comfort of home baking and suffused by a brilliant living light. He was home.

In an hour Daddy will be home. Homework will be discussed and examined. And as Tommy plays Scott Joplin on Teatime with Tommy, we’ll devour the day’s labours and dissect the day’s events.

July 7, 2015

Stormshell Productions

Sorry for my (almost forced) absence from WordPress in the past two months. I’ve been busy preparing to make my first short film, 1916, Souls of Freedom, a short drama set in Dublin about two men, soldiers of the ill fated ten day long revolution in Dublin, 1916, hiding in an abandoned house, from soldiers of the Crown, intent on their arrest and/or destruction.

Film and film making have been life long interests of mine and I never thought I would get the opportunity to try my hand at such a still, relatively, young, art form. This link should bring the viewer to the You Tube channel of Stormshell Productions and three videos that showcase our output to date. Comments are welcome.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCjd3ebqrv2krA5Hn6LCodeA

April 10, 2015

Tosca’s Tale continued

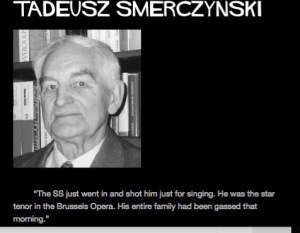

In January 2015, the world commemorated the liberation of Auschwitz, 70 years before, by the Russian Red Army. To mark the occasion, there was a week of articles and tv documentaries. I was watching one of these one night, a program that traced the lives of six Auschwitz survivors, after that day of liberation. One of these was Dr Tadeuscz Smerczynski, a Polish national interned in Auschwitz as a political prisoner.

On leaving Auschwitz, Tadeuscz vowed to devote his life to a career in medicine and particularly, medical research. He excelled in college and was well on his way when he was approached by the Polish Communist Party and asked to join. When he refused, his life became a nightmare. Separated from his family, he served for five years in the Polish army and all his subsequent efforts to become involved in medical research were to no avail. Undeterred, indeed, determined, he became a GP except the only place he could find to develop a practice was within a ten minute drive of Auschwitz.

In the documentary, Dr Smerczynski told of how there were two things that revived the nightmares of those years in the German concentration camp. One, was passing the former Camp and he lived only ten minutes drive from it. The other was an aria from Puccini’s opera, Tosca, which he heard an inmate sing, one day and to this day, he could not listen to that aria.

His story moved me because, as ephemeral as it may seem, the thought that something as beautiful as a Tosca aria could be turned in to an inadvertent symbol of oppression, both angered and depressed me.

So I wrote this poem, Tosca’s Tale. Then I sent it to my friend, Anna Zak in Poland, a post graduate student of translation. She introduced the poem to her classmates and together, as a lesson, they set out to translate the poem.

Then they went a step further. Anna contacted the family of Dr Smerczynski and though he’s long since retired from his GP practice, his son has continued in his place. After Anna and Dr Smerczynski’s daughter in law exchanged a couple of emails, she forwarded the translated poem and it was shown to Dr Smerczynski.

This is the message he sent me.

Szanowny Panie Detmott,

Niesamowitym prze��yciem by��o dla mnie us��ysze�� ten pi��kny ��piew w scenerii obozu koncentracyjnego. Emocje tenora kt��ry straci�� rodzin�� w komorach gazowych i r��wnocze��nie zosta�� pozostawiony przy ��yciu ��eby s��u��y�� SSMan’om. Cz��owieka maj��cego ��wiadomo���� ��e jest to ostatnia pie���� jego ��ycia i chc��cego wyrazi�� sw��j dramat. Si��a tych uczu�� odcisn����a si�� w mojej pami��ci bardziej ni�� jakiekolwiek prze��ycie ostatnich 70 lat.

Wiersz “Opowie���� o Tosce” niezwykle trafnie oddaje te emocje.

Z wyrazami szacunku,

Tadeusz Smreczy��ski

Dear Dermott,

It was a striking experience to hear this wonderful song in the scenerry of the concentration camp. The tenor’s emotions, who lost all his family in gas chambers and simultaneously was left alive to serve SSmen –��SCHUTZSTAFFEL.��

the man who was aware that it was his last song in his life, who wanted to express his tragedy. The strength / power of these feelings has left a deeper mark in my memory than any other experience fir the last 70 years in my life.

��

the poem “Tosca’s Tale” remarkably accurately ��expresses those emotions

��

Best regards

Tadeusz Smerczynski

This is the poem.

Tosca���s tale

of love and loss

sung aloud, forlornly

in Auschwitz,

the charnel house

of tyranny,

rang true and clear

without breath of fear,

set free by willing

and defiant spirit,

to relate the story

of love���s contentious struggle

against bitter hate

and treachery

and though

suddenly snuffed

and silenced,

its defiant message

rings true today

as in the words

of Edmund Burke,

paraphrased,

sing now

and defy

all tyrants

and here is the Polish version, translated by Anna Zak and her fellow students.

OPOWIE���� O TOSCE

Opowie���� o Tosce

o mi��o��ci i stracie

wy��piewana w Auschwitz

g��o��no i z rozpacz��

w grobowcu ofiar tyranii

brzmia��a czysto i wyra��nie

odwa��nie

wyzwolona przez ducha

niez��omnego, niepokornego

aby zn��w przypomnie�� opowie����

o za��artej walce

mi��o��ci z zaciek���� nienawi��ci��

i zdrad��

i cho�� tak nagle zd��awiona

i uciszona

to jej wyzywaj��ce przes��anie

dzi�� brzmi prawdziwie

tak jak s��owa

co od s����w Edmunda Burke’a pochodz��

��piewaj na przek��r

wszystkim tyranom.

February 20, 2015

People of Dublin

February 11, 2015

Sauce for the Goose

Double standards in public life is almost de rigueur these days. Anyone following the trial of a former banker and French presidential candidate or reading the unfolding revelations about HSBC’s Swiss branch’s services in the interests of big capital greed, will know what I mean.

In Ireland, the incumbent government has lurched from one disaster to another but holds, resolutely, to the patronising notion that it knows best.

To prove its point it persists with the intention to bill its overtaxed population for water they’ve already paid for; it denies private legislation drawn to overcome an appalling anomaly and allow women abortions in cases where full term delivery would result in the inevitable death of the mother; now it arrests peaceful protesters by sending six policemen to their doorstep in the early hours of the morning.

January 31, 2015 was the latest deadline Irish people were given to register for Irish Water, the private company set up to run the new water service, yet, even by their estimation, there is a shortfall of at least 50% of the population, on the register and, from now on, we’re on the clock and the bills will arrive in April. So I wrote this poem, Sauce for the Goose, in response and reaction.

will I pay?

for what? I say

water, today

no way

will I register?

for what? I say

water, today

no way

Yes, I will register

my anger and disgust

at the wholesale

greed and lust

because I will pay

for others��� avarice

and acquisition

and grotesque ostentation

while they walk free

as though protected

by misguided misconception

of lese majeste

justice, we seek

for the cold and the meek,

the dispossessed and hungry

a bed for the sick, a smile for the lonely

balance, we seek,

not only in budgets

ledgers or sheets,

but in human relations, the man in the street

They will register our resistance

while they balance their books

glancing with fear and suspicion

at our rueful looks

As they pay off the fiscal burden

like a jaded puppy with an old bone

wagging its tail, to be thanked

by Eurocrats, for a job well done

But when the figures are added

and the coffers depleted

there remains a debt unpaid

though not in coin

or platitudes

or threats to a scolded child,

as the elected lacky

turns boss for those who foot the bill

and tell us they know best

so hush, now

don���t be shouting

or we���ll knock you in the morning

and take you down

before you jet away,

no, I���m wrong,

before you question our right

to do what is wrong,

so let the poor go hungry

we���ll take your homes

to feather our pension cushioned nests

while tax cheats

fill the election war chests

before flying home

to their sun drenched havens

So what���s sauce for the goose

should be sauce for the gander

and if they won���t pay,

I won���t either

February 10, 2015

Indelible Echoes

A harbour breeze,

a mountain spring,

rain and the smell of heather,

a hazel copse,

freshly cut turf,

crickets in the thatch,

sizzling mackerel

laughing spuds

and periwinkles,

sand in your toes

and the salty brine

of seaweed,

memories of sight,

sound and smell,

indelible echoes

February 1, 2015

Irish Newspapers in collective cranial meltdown?

In my last post, I highlighted how one Irish national daily newspaper, the Irish Examiner, ran a quarter page ad for domestic gas on the same day and on the same page they lead with a story about survivors of Auschwitz.

Now, the Irish Independent has featured an ad about a German supermarket chain’s meat supplies – featuring a very graphic sharpening of a carving knife, followed by the cutting of some very tender meat – before a video report on their online edition, about the beheading of a Japanese journalist by Isis. See for yourself.

January 29, 2015

Oh dear…

Sometimes, when newspapers fuck up, they REALLY fuck up…Check out the lead and second lead stories in the Wednesday, January 28 edition of the Irish Examiner. Then, check out the big advertisement at the bottom of the page. WHOOOPS

January 28, 2015

Tosca’s Tale

Seventy years since the survivors’ of Auschwitz were liberated, I was watching a tv documentary where six of them recounted their stories of survival and the terrible aftermath they’ve endured, of nightmares and tragedies. One Polish man, who became a doctor and practiced general medicine within ten minutes of the camp gates, has been forever haunted, not just by the memories but by his own physical proximity to the camps. One other thing that horrifies him, is an aria from Puccini’s opera, Tosca, itself a tale told against a backdrop of tyranny and oppression. He heard an inmate singing the aria. He said it was strange to hear such a thing in the surroundings of the camp. An S.S. guard heard it, too and ran to find its source. Our survivor asked someone, what happened? The singer was killed. His story moved me to write this poem.

Seventy years since the survivors’ of Auschwitz were liberated, I was watching a tv documentary where six of them recounted their stories of survival and the terrible aftermath they’ve endured, of nightmares and tragedies. One Polish man, who became a doctor and practiced general medicine within ten minutes of the camp gates, has been forever haunted, not just by the memories but by his own physical proximity to the camps. One other thing that horrifies him, is an aria from Puccini’s opera, Tosca, itself a tale told against a backdrop of tyranny and oppression. He heard an inmate singing the aria. He said it was strange to hear such a thing in the surroundings of the camp. An S.S. guard heard it, too and ran to find its source. Our survivor asked someone, what happened? The singer was killed. His story moved me to write this poem.

Tosca���s tale

of love and loss

sung aloud, forlornly

in Auschwitz,

the charnel house

of tyranny,

rang true and clear

without breath of fear,

set free by willing

and defiant spirit,

to relate the story

of love���s contentious struggle

against bitter hate

and treachery

and though

suddenly snuffed

and silenced,

its defiant message

rings true today

as in the words

of Edmund Burke,

paraphrased,

sing now

and defy

all tyrants

Postcard from a Pigeon

- Dermott Hayes's profile

- 4 followers