Dermott Hayes's Blog: Postcard from a Pigeon, page 85

August 11, 2014

Who’s the Boss?

Who’s the Boss?

I’ve been listening to I’m Not Bossy, I’m the Boss by Sinead O’Connor before I’m overwhelmed by comments and misguided reviews. Of those, I’ve read a few. Some spoke of a new maturity while others toyed with the notion of Sinead, the auteur, creating ‘characters’ with and about whom she can spin tales of forlorn romance, wanton abandon, dutiful devotion, self loathing, seduction, fear, horror, vindictiveness, persecution and adulterous husbands. Funnily, I’ve known all these Sinead’s, just as I’ve known, as many others have, the funny Sinead, the devoted mother, Sinead as well as Sinead, the incisive analyst.

This album is Faith and Courage, Part II. Fourteen years later, she’s still a woman with an aching need to love and be loved. So far, so simple, you might think until you hear of her desire to be a dutiful wife, washing, cooking and even, gasp, baking, for her man. Then she wants to be a slut, have a mad night out and be the seductress of young men and adulterous husbands. Cleverly, she has spoken of writing about ‘characters’, where she has taken the ‘I’ of old and replaced it with the third person. Make a Fool of Me All Night, one of the extra tracks in the De Luxe version is Sinead, the lover, in full flight, locking the door and the world outside and giving in to the abandonment she craves. People don’t see the humour and self deprecation in Sinead and her music. They only see the hurt. If you look for that here, you’ll find it, too. It’s in the love songs, too but it’s obvious in 8 Good Reasons and even more obvious in ‘Harbour’, which, if you reflect on it, conjures disturbing images.

I’ve always rated Faith and Courage as one of Sinead’s strongest albums and this album has all its strengths and more, particularly a musical relationship with John Reynolds, her long time musical and personal collaborator, that has matured into an innate understanding.

August 9, 2014

Words of Mouth

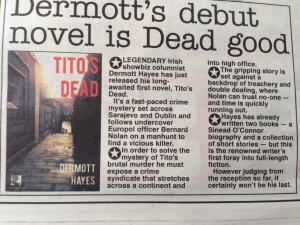

My eternal thanks to those who took the time and bother to buy TITO’S DEAD. It appears Irish readers are among the last of the Literary Luddites, who appear to believe language is communicated through paper, rather than words, hence, an apparent reluctance to grasp the notion of reading a book on their phones.

Undeterred, though, I am a firm believer in TITO’S DEAD. It is, and not just in my estimation, a well written and exciting crime thriller.

The intention I had, in publishing it myself, was, apart from my own resolute stubbornness and lifelong desire for independence, a combination of disillusion and disbelief in the priorities of conventional publishing. It’s cheap, too, or rather, low cost.

What they don’t tell you about are the hidden costs, particularly marketing. Now I’ve never been a ‘joiner’, so I’ve an innate reluctance to parade my wares through the countless promotional social sites and blogs and twits. So that’s been a disadvantage.

I’ve no axe to grind, no bone to pick and no song to sing. I’ve only got my words and the stories they tell. I’ll go on telling them.

I got my first ‘royalty’ from Amazon, recently. It wasn’t, by any stretch, an impressive sum and it will never defray my costs. But it did afford me some measure of recognition, at least for the path I’ve chosen.

By day, I work as a waiter. All the time, I’m a writer. I was a journalist for more than twenty years. Sadly, my creative writing activities have not warranted much support from my former colleagues – with the sole exception of my old mate, Mark Kavanagh, deputy editor of the Irish Daily Star.

I’ve started writing a new book and I’m feeling good about it.

Tito’s Dead deals with a world where the roots of every motive are underpinned by others that can be secret and evil. But humanity holds itself together.

Words, language and communication are the three things in my life that remain constant. Perhaps it’s a sign of the times. I was born in the ’50s and moved, through transistor radios, stereo phonics, Walkmen, eight tracks, cassettes, DAT, CDs, microwave to broadband and smart phones.

But the one common thread is language, almost a living, breathing organism, however abused, it adapts, shifts shape and meaning.

That’s what I wanted to tap in to by self publishing TITO’S DEAD, word of mouth. Perhaps naively, I believe good, will out and people will seek and find quality. So, if you’ve read TITO’S DEAD, ‘Share’ this and let someone else know.

And, if you haven’t read it, please do. Then, tell your friends

July 2, 2014

Writing Again…here we go

I compare writing to stepping on a rollercoaster. There is certainly a similarity in the emotional impact.

I’ve read and re-read many books about writing but I don’t think there is any right or wrong way to do it and everyone has their own style and approach. Some people are extremely well organized, often to an OCD extreme. They prepare their space, gather their pencils or pens and stacks of paper in loose leaves or refill pads; some use old typewriters.

Many set themselves a timetable, allotting a specific length of each day to sit at a desk, staring at a blank page, waiting for inspiration. Others take the ‘there’s no such thing as an empty page, only empty thoughts’ approach. This involves in writing anything and everything, until something clicks and the bones or frame of a story begin to appear. At its worst, this conjures images of Jack Nicholson typing ‘all work and no play…’

At its best, there is a lot in its favour. Once you start writing, the mind is stimulated and things do begin to appear, much of which you might discard later on but at least you’re writing, like taking your imagination for a walk. It’s exercise.

Story ideas can come from anywhere so the writer’s mind must be like one of those ‘dreamcatcher’ nets, the kind of thing you see in those shops full of crystals, stones and old bones, they tell you were designed and used by tribal shamen to capture and interpret dreams. So, if you’re a writer, catch a dream and turn it in to a story.

It could start with a character, someone you know or have heard of, who intrigues you or perhaps it’s an incident you’ve heard of, maybe involving someone you know, have read about or encountered. All these things act as triggers for the imagination. So that when you start writing a description of a person you’ve encountered or a snippet of conversation you’ve had or overheard, then you think of a scenario or an incident that intrigued you and, suddenly, that character you were writing about, walks right into it and it feels good, because it fits. Now you’re sucking diesel.

I’ve had characters running around in my head for years, seeking a home, a plot, a story. Flann O’Brien gave these aimless characters a home in his more surrealistic novels as they began to take over his stories and rebel against his plot lines, displacing themselves, going missing, interfering and invading other story lines. Kurt Vonnegut Jr did that too. Tom Robbins and many other writers have taken a stab at it, too.

Essentially, there are no rules because a story’s a story. And therein lies the rub, if it’s not a story, why would you read it?

There have been story lines in my head, too that I could never find a home for or characters to live in them. My novel, TITO’s DEAD began life as a short story, about a young Kosovan refugee, living in Dublin, who befriended an injured pigeon and nursed it back to health. That simple act of kindness for an injured creature, earned him respect, for himself and from those who watched him. It made me wonder why, without that simple act, we couldn’t see he was injured, too?

About that time, when I began to formulate the story of Tito, there was a news incident about a truck full of dead immigrants being found in Wicklow, on the road from Wexford where they’d been smuggled in to Ireland, via Rosslare, from the Continent. The Balkan conflicts were in the news all the time and Ireland, like many other European countries, was awash with displaced people from warzones like Serbia, Bosnia and Kosovo. The unfortunates in the truck, I remember, were Turkish Kurds, traced back to a small mountain village by a newspaper colleague of mine.

The plight of refugees and illegal immigrants began to preoccupy me. There was talk of Albanian gangs muscling in to certain inner city districts, displacing the old guard of native criminals. There were occasional clashes between these opposing parties, reported. I had a friend in the army who performed ‘peacekeeping’ duties with IFOR (Implementation Force), the multinational NATO group set up to implement the Daytona Agreement in Bosnia Herzegovina, between 1995 and 1996. Another friend, an Irish police detective, spent a year on secondment in Kosovo, helping to reorganize the civilian police services there. They had interesting stories to tell.

At the same time in Ireland, there appeared to be a lot of money in circulation and with money comes crime. People were having a good time, spending and enjoying their new wealth, it was a party. And that party was fuelled my mountains of drugs, supplied by the burgeoning crime gangs and their drug lords who were given curious nicknames like ‘The General’ and ‘Fatso’, and many others.

So I locked myself away in a small farmhouse in county Clare and let loose the hounds of imagination, howling in my head. Within five days I had written 25,000 words and TITO’S DEAD was no longer a notion in my head, it had a life of its own.

May 26, 2014

The Russians are coming

The Russians are coming

This is a short story from my published collection, Postcard from a Pigeon and Other Stories. Since the recent anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis and an article by John Pilger in The Guardian (http://fb.me/3pbmzC0cg), I decided to post my take on that historic event, as experienced through the eyes of some children in a small country village in Ireland in 1963

This is a short story from my published collection, Postcard from a Pigeon and Other Stories. Since the recent anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis and an article by John Pilger in The Guardian (http://fb.me/3pbmzC0cg), I decided to post my take on that historic event, as experienced through the eyes of some children in a small country village in Ireland in 1963

THE RUSSIANS ARE COMING

By Dermott Hayes

It was shopping day and Mammy wrapped me up well for the long walk across the border.

She put on her best coat, tied a scarf around her head and gathered her two shopping bags. Before we left the house she checked her list and her purse. She put on one of her gloves at the hallway door and paused long enough to splash us both with Holy water from the white china font of an angel carrying a giant seashell, hung by the door. Satisfied I had blessed myself, she muttered a prayer and said, ‘right, we’re away so…’

Our walk took us through the neighbourhood. She greeted neighbours cheerily as they went about their morning chores of sweeping and cleaning and scrubbing.

Every now and then she paused to lean across a hedge with her hands clasped as though one was supporting the other.

‘How’s Maisie?’ she’d say, ‘d’ye think it’ll rain?’

Weather was always a safe opening gambit. It allowed both parties to take up a position of comfort and an air of authority and opinion.

‘The sky’s full of it, Martha, and there’s a bit of a blow but with any luck it’ll hold ‘til I get some dryin’ out of it.’

Both of them stared at the sky that was an eggshell blue and dotted with great fluffy balls of cotton wool clouds. There wasn’t a hint of rain in it, as far as I could tell.

‘Are you over to the shops?’ Maisie asked, her own arms crossed beneath her pinafored chest.

‘Aye, I’ve a few things to get to have in the house, just in case…’

This last observation trailed off with ominous significance. Both women shared a conspiratorial look of long suffering.

‘The way they’re talking we’ll all be dead in our beds before they can get a war started,’ Maisie observed, her eyes, squinting and fixed on some point on the horizon.

‘Sure the whole world’s gone mad,’ Mammy replied in agreement, ‘it’ll just take one of them to press the button and we’ll all disappear like those poor people in Japan.’

‘Sure, it’s ten times worse now,’ Maisie rejoined, warming to her subject, ‘they called it the end of war but they forgot to tell us it’d be the end of the world too.’

Mammy flashed a swift look of disapproval at her as though she had broken some time honoured rule of grown ups that there were things best left unsaid in the company of children. She rearranged the straps of her handbag and shopping bags on her arms, touched her scarf at the hairline and took a step back. Then she blessed herself.

‘Please God it won’t come to that,’ she prayed.

Bowed, Maisie took a step back herself and lowered her eyes as though to concentrate on some hitherto undetected flaw in her garden hedge.

‘President Kennedy will see us right,’ she offered, encouragingly, ‘and all we can do is pray.’

But the damage was done. I heard it all. My trip was spoiled. Not even the lollypop I got from the barber who cut my hair that day, nor the sixpence Mammy’s friend, Mrs Ferguson, pressed into my hand when we went visiting, could distract my thoughts from the horrors in store for us all.

The next day we were staring at the sky.

We stood in a circle, the four of us, in furrowed concentration, staring at the sky.

“The Russians are comin’ t’ drop bombs on us,” I threw in the pot with as much authority as my seven and a half year old frame could muster .

“‘A’sright,” Hughie piped in, “but pres’dent Kennedy’s goin’ to protect us.”

“That’s shite,” Scratchy blurted indignantly, “my Daddy says the Russians don’t give a shite about us.”

But we didn’t believe him. For a start Scratchy’s Daddy was no authority. My mammy told Hughie’s mammy that he knew nothing except the drink and his bed. He had made a career of idleness, they both agreed.

Scratchy’s daddy was also well known for his poaching and smuggling skills and he had a way with greyhounds, it was said.

Scratchy was a tough kid and he was one of the gang. If you sat beside him in school you’d soon know where his name came from. He was good to have on your side in a fight. He could climb any tree and had no fear of diving in the river.

The night before as I lay wedged by the wall in the double bed I shared with my brothers, the warm, greasy smell of chip van fish supper sneaked like a thief through the open window and wafted around the room. It was followed by the sound of Scratchy’s voice, singing a pop chart hit, ‘from a Jack to a King…”

“Wad’yethink?” Scratchy asked the fourth of our skygazing, group, Wee Phonsie. Phonsie was nine and would not have been seen with us of a summer’s day. There was nothing wee about him either. But that day none of his friends were about and the village was buzzing with rumours.

We reckoned Wee Phonsie was some class of genius who couldn’t express himself. He was not given to expressing his opinions or even talking at all at the best of times. He would giggle to himself as some thought occurred to him. This, as always, appeared to set off some internal debate which, quickly and quietly resolved, was followed by a shrug, another giggle and silence.

This time he pushed his thick blond fringe back from his eyes and stared at his shoes.

Scratchy, his left hand shading him from the summer sunlight as he squinted skyward, got suddenly agitated and began jumping up and down. “The Russians’r’comin’,” he roared, “heretheycome, the Russians’r’coming.”

High in the sky the telltale silver glint of a lone jet’s underbelly. Its twin vapour trails stood out in the blue of the summer sky.

The appearance of a jet in the skies of north Donegal in the early ’60s was as remarkable as a neighbour with Radio Telefis Eireann, or Free State tv, as my daddy called it. Our wee group’s agitation drew attention.

Mothers and fathers, children, babies, dogs and the postman, who had just appeared on his morning rounds, all stood with their heads tilted to the skies above. Rosaries rattled and a chorus of whistling prayer whispers hummed over the morning hush.

Mrs Gallagher began reciting the Sorrowful Mysteries as the entire community fell to its knees with her in a rustle and wheeze of beads and church trained coughs. Mammy crossed herself and fell to her knees on the other side of the tidy privet hedge separating their two gardens.

Mammy was a devout woman who attended Mass every day of the week, every week of the year. She went to Sodalities, prayer meetings, Stations, blessings and special Masses for the sick and dying. She picked flowers for the church and helped sweep the chapel clean after Sunday masses. But she would never start a rosary in the street.

Phonsie stole a furtive peak at his mother, frowned, swallowed, smiled and then giggled. He pushed the hair back from his forehead and stared at his shoes.

Scratchy reacted fastest. Faced and surrounded with this spontaneous outburst of communal piety, he dived for the cover of his own overgrown front garden. As the droning response engulfed us, we fell to our knees.

The sun slipped behind a big fluffy cloud and a dreary gloom joined the drone of prayer as an unseasonal icy chill made us shiver in our summer shorts.

It passed as swiftly as it came and the sun swept back the gloom, lighting the dusty, cricket worn sward of green and warming our bones.

“HERESTHEOTHERCROWDNOW,” Scratchy squealed breathlessly as he pingponged from his own garden, waving his arms and pointing skyward. And as he joined our huddled group of friends again, he added, “OHBOYSOHBOYSTHERESGOINABESOMERUCKUSNOW.”

His interruption ended the prayers as everyone, hungry for every scrap of news watched his eruption from his garden with interest and followed his pointing finger skyward.

Another silver gleam made them squint in that bright lunchtime sun. The same thin twin vapour trails…It appeared in the top right corner of the sky; the first, from the bottom right. Both were heading in roughly the same direction, left.

“That second one looks smaller and faster,” someone commented.

“Aye, he’s catchin’ up on the first fella,” said another. Neighbours began to emerge slowly from their own gardens and encroach the space of our circle on the tiny green.

Our circle had by now taken on a magical power. Our world, the village had spilled from its homes and everyone was on their knees praying. Fear made me shiver for the first time as I watched Mammy kneel in prayer in the front garden.

The men engaged in a murmur of sullen debate. Few would concede ground to others by dint of ignorance.

Standing in a circle in the green, clutching hands on either side, I began to think of death and remembered with a shiver the night I’d touched a cold corpse.

Just a week before I could recall the stuffy iciness in the neighbour’s house the night they laid him out before his funeral.

The bedroom smelled like Mass of a wet November, all sweat, damp clothes, cheap perfume and incense. The sombre neighbours, used to ordering pans and baps from the man before them as he used to drive a bread van, filed in their turn to his bedside, leaned over and touched the body before blessing themselves and filing out.

I ran away that night. Shot down the stairs, out the garden and across the green past the two boys sitting waiting in the garden and didn’t stop until I reached the comfort of home and the arms of Mammy.

Running was not an option this time. Now death, that I had already touched or, more truly, had touched me, was on its way back to feast on our wee village.

The second plane, it was suggested, was clearly an American Air Force fighter bomber, lighter, nimbler and faster than the missile laden Russian craft.

It arrived, pundits maintained, from a North Atlantic patrolling aircraft carrier to honour the promise President Kennedy, himself of Irish Catholic extraction, made to protect Catholic Ireland from the invading Communist hordes. Its mission, as the two vapour trails approached each other miles above us, was clearly to thwart the Russians and save us all. It was scary.

The praying resumed as a lone voice speculated this could be the end of the world. But the rosary ripple had barely begun before Hughie’s daddy erupted.

He was an educated man and a senior manager in the county council. This warm Saturday morning he had stepped from his home without his customary suit jacket. His shirt unbuttoned, the sleeves rolled up, he sat down in his own front garden on a kitchen chair to read his morning paper.

The scorching noon day sun pinkened his bald pate. He wore a neatly knotted linen handkerchief to protect himself.

He observed this public outcry of piety and fear with curiosity and amusement. He even doffed his knotted hanky and murmured a response to Mrs Gallagher’s prayer lead.

But when he heard the phrase, “the end is upon us”, he exploded.

Waving his angrily scrunched up Irish Independent he shot through his garden gate into a knot of men gathering in the road in front of his house to hear what he had to say.

“YE’RE ALL TALKING SHITE,” he declared. His anger was enough to quell the crowd’s clamour but the profanity, spoken from a man with as much clout and respect and fear in the community as a man of the cloth, a man in a uniform or anyone else in a suit for that matter, stopped them all. It shut them up so they almost forgot how to make a sound.

In our circle, Hughie, scarlet with embarrassment, giggled with secret pride.

“These jets are just regular transatlantic traffic and they’re either on their way to or from America or the European mainland,” he explained with bored indignation, “one is much higher in the sky than the other and arrived in our bit of sky long after the other. They could be both on their way to Shannon airport to refuel.”

Mr McGinley turned about after his outburst and returned, unravelling his by now shredded newspaper, to the garden seat to resume his Saturday leisure.

Silently acknowledging his unspoken signal people receded into their own while giving him looks like he’d just burst the ball in an important match. Everyone kept their eyes peeled on the sky. Just in case.

The men were pointing at the sky and arguing amongst themselves. Scratchy’s daddy emerged blinking from his own bed, a rare and remarked upon sight before noon. A fervent murmur of prayer rose from a knot of women.

There was irrefutable logic aplenty. Everyone had, as Mr McGinley angrily pointed out, seen the paths of two planes intersect in the sky above the village before.

But this was different.

Both planes appeared from different corners of the sky. One, (the Russian, some believed) came from the north east and was heading south. The other, (the American saviour) followed from the northwest. Both were heading south and their vapour trails, high in the sky, were on the point of touching.

“OHSACREDHEARTOFJESUSMOTHEROFMARYGODSAVEUS,” someone shouted. The praying resumed again, even louder. We gripped each other’s hand tightly in our magic circle on the green. Phonsie giggled nervously through grinding teeth.

And as we stared, the vapour trails crossed in the sky and a warm trickle of pee ran down my leg, soaking my shortlegged summer khakis. I cried at the sky and peed on my shoes that day the world nearly ended.

May 24, 2014

Foreword and first Chapter to TITO’S DEAD by Dermott Hayes

My first novel, TITO’S DEAD was published last month. It is set in Dublin and Sarajevo and it’s a crime mystery novel. But it’s also a story about human relations and how we learn to live with each other.

Irish Daily Star, May 21, 2014

Foreword

No-one was surprised when we heard Tito was dead. For what we knew of him, he was dodgy. You wouldn’t trust him with your mother, one of his own pals once grumbled. There was little else to be said.

Or was there? Everything about him left you feeling uncomfortable. I didn’t know him that well but I felt he knew my secrets.

It’s been a year since the whole Tito thing and it lasted less than a month but the reverberations are still felt. It’s not as though he was mourned and missed. His disappearance barely raised a question. Maybe there was a joke or two because he was colourful and weird and that was a perfect combination for some speculative analysis from the committee of experts who reserved squatters’ rights in one corner of the bar.

Tito might be dead or sitting on the terrace of a house in Albania, sipping a cold beer and watching the sun set on the Adriatic. In the nature of these things, I’m prepared to believe either story.

The thing that bothered Tito was his invisibility. He knew, considering his legal status, he needed to be invisible but it was not in his nature. Tito raged against the anonymity.

There were other things he hated, like missing his family and particularly, his younger sister. In the days before he disappeared, he mentioned her to a few people. Himself and Deare, the journalist, were close. They often spoke together in a quiet huddle and occasionally you would hear Tito sob or roar. He couldn’t just cry.

I told him invisibility protects us but he couldn’t see it. “It is all very well for you to say this when you have people you can talk to, who know who you are and can bless you and curse you…” he lashed back at me and only for it was more words than he’d ever directed at me in one sentence, I might have had a profound and witty reply.

I didn’t though. He never let anyone close enough to understand his anger. So all we could do was resent him. When he refused to work, the work got done by someone else. Whether he left when he left, his days in the pub were numbered.

Anonymity is good for a bartender because all you have to do is sell drink. But that means standing in a confined space for eight hours pouring drinks for strangers while you listen to their stories and watch them get drunk. You’re anonymous because the customer doesn’t see you. Drinking is a performance art and you are the audience. Sometimes it’s about a celebration but more often than the celebrants will admit, it’s about contrition and regret and you are the priest confessor. Conspiracies and intrigues are hatched in drink and the players forget the stagehands are watching and listening.

I have seen unfaithful wives and philandering husbands spin webs of deceit for their companions or, on any night, their chosen and often complicit quarry and all this without a thought for who might be listening on the other side of the bar.

Most of the time, you couldn’t give a damn and mark it all down as part of life’s so-called rich tapestry, just another cliché to be stored away for future use. A good bartender, I’ve always said, should have as many of those in his or her head as cocktail recipes.

“You don’t know me,” was one of Tito’s favourite, dismissive phrases. “And you don’t fuckin’ know me,” I’d bark back at him. And though there was more meaning in what was left unsaid than the empty banter we exchanged, neither of us understood the other.

I wanted him to know you can never know someone who doesn’t know themselves; that everyone makes up their own story and there’s not a living person on this planet without a secret. I wanted him to know a thousand things I thought about trust and friendship but I couldn’t, because I didn’t know if I believed them myself or if I wanted to share them with him, either.

He may have felt the world had abandoned him and his kind and you could forgive him for forgetting there were other people hurting. I hope he knew when he was handed the postcard from the pigeon, that that was his recognition. At least, as far as anyone in the pub was concerned but if ignorance is bliss, it’s no excuse and certainly, no solace for its victims.

It was Peter Cahill’s idea and it was a good one. It surprised me at the time that Cahill, a high flyin’ Special Branch man, would even bother his arse. But right then it was the perfect antidote for Tito’s gloom. We didn’t know then it was his death warrant.

The way I think it went, is this: Tito thought he was a player but he was just someone else’s pawn. Beneath all his bravado beat a wounded heart. He craved recognition, not for any reasons of vanity but because he wanted to love and, I suppose, be loved and there was no-one who could acknowledge it.

He wasn’t unlike anyone else, whether their name was Tito, Mick or Mary. That’s why I’m breaking my own rule of anonymity although this is the last you’ll hear from me, because this is Tito’s story.

SARAJEVO

Peter Cahill wasn’t happy staying in Sarajevo’s Holiday Inn. He wasn’t too happy about being told what to do, either. Particularly when the orders come from a jumped up American spook without the manners to take his mirror shades off throughout their meeting.

It’s all very well for this creep to stand there shouting the odds, he thought, but I’ll be the one whose arse will be on the line if the whole thing goes pear shaped.

“Are you confident everything is in place?,” the eyeless Yank was asking, “and there’ll be no hitches?”

The Holiday Inn was a pig ugly, yellow building that became one of the best known landmarks in the city, only because it managed to stay standing when all about it was getting blown to bits. Smack dab on ‘Sniper Alley’, on the main route from the airport to the city, it was the headquarters for every foreign war correspondent during the bitter ethnic conflicts in the ‘90s.

War with fucking room service, he heard himself grumble. The brochures said ‘grand’ and ‘majestic’, he figured, because it was still standing. He didn’t like it because he felt exposed. He was an Irish policeman meeting an American spook in a Bosnian hotel.

The hotel was fine, he conceded, Holiday Inns were Holiday Inns, the Mickey D’s of hostelry. It was central but he wasn’t there to see the sights. He hardly left his room since checking in apart from a visit to a café on the corner for a cup of Turkish coffee. Even that put the fear of God in him.

The hotel was stuffed with tourists and carpetbaggers: the first, attracted by the cheap prices and the ghoulish thrill of walking in the shadows of ghosts; the second, the kind who thrive on the carrion of a fallen city.

There were too many Irish people in Sarajevo, in his estimation, as police, soldiers or civilians. If it had been his choice he would have done this somewhere else.

The U.S.’S ‘War on Terror’ knew no boundaries and America’s allies were swiftly finding out if you weren’t with them, you were against them, as far as they were concerned. ‘Get with the Plan” was no longer an invitation, it was an order.

He studied the face of the man who asked the question. He was square jawed, broad and black. His hair was cut in what Americans referred to as ‘crew’ style. It looked as though it had been chiselled and finished with a precision laser. The eyes (or, at least, the shades) were impenetrable.

Agent Powers wore the regulation, reflector style, aviator sunglasses they gave him when they broke him out of his mould. He didn’t like him but they weren’t there to get to know each other.

He concluded his operational briefing and answered, “we’ve already set the wheels in motion. Contact has been made with a young Kosovan woman. She has given information about our target’s associates, here and in Dublin. We have set in motion a series of events that should draw our man out of hiding to protect his investment and keep control of his operation.”

“Good. Are you confident of your intelligence in Dublin? Are you sure the target will be there?”

“Absolutely, he’ll be there, alright. He visits Dublin and keeps a house there. But he’s unpredictable but our plan should draw him out of cover.”

‘Does your man in Sarajevo know about these plans?”

“No. The operation is ‘need to know’ only and that clearance goes no further than this room. Everything will be completely deniable in the event of a cock up.”

He stared at his own reflection in Agent Powers’ sunglasses. Christ, he thought, I look really pissed off. Calm down, for fuck’s sake. Don’t give this wanker the satisfaction.

He knew he was far less confident than he sounded and he hoped Powers was convinced. The job was shaky from the word ‘go’. The target was ‘untouchable’, which was why, he guessed, the task had been handed to him.

Powers appeared to hold his gaze for longer than was needed in the tension filled pause that followed their exchange. He turned to the third person in the room and spoke to him for the first time.

“Are you clear about the details and satisfied with the plan?”

The third man hadn’t spoken since he’d arrived, half an hour before, even as they’d gone through the logistics of the operation in detail. He was dressed in a neat, beige, suit with an open necked blue shirt, exposing a deeply tanned body. His hair was a blue steel, gray but as thick as a teenager’s. He wore no shades but his eyes were a liquid blue and seemed to float about in his head. He considered Powers’ question for a time before answering. Cahill and the American waited. Old Blue Eyes was in no hurry.

The Irishman had already met him, unofficially. Blue Eyes introduced himself as ‘Abe’ when they met in the hotel foyer, earlier that day. It appeared to be a casual encounter as Abe stepped into the elevator with the Irishman right after he’d registered and collected his room key.

Abe came straight to the point. “I don’t trust Powers,’ he said. Cahill feigned ignorance but Abe said, “I know your name and I know why you’re here.” And before he could protest, he continued, “when they ask us to do something they’d think twice about doing themselves then you have a right to know how to protect yourself. We must do this job together and I like to know who I will share danger with.”

Cahill wasn’t sure how to react but he warmed to Abe’s direct approach. He couldn’t place his origin or accent and Abe never volunteered any information. He appeared Mediterranean in that lifelong tan and his ‘cool in the heat’ manner, but that was as close as he could call it.

Abe smiled and shook hands with him before he got out of the lift. He didn’t see him again until he turned up for the meeting. Now they were sitting in this hotel suite and they were hanging on this man’s answer. Abe’s silence had shifted the power base in the room.

Finally, shrugging and with pursed lips, Abe said, “it’s a crazy plan but what option do we have?”

Agent Powers wasn’t satisfied. “Have you picked a man to do the job?” he asked. Blue Eyes looked at him as though he was seeing him for the first time. “If he’s happy,” he said, nodding at the Irishman, “then I am happy. We have the perfect man for the job.”

May 15, 2014

Who’s at the Door?

Another short story from my 2012 published collection, Postcard from a Pigeon and Other Stories. This was written in response to a topic challenge in a writers’ forum.

Who’s at the Door?

By Dermott Hayes

Mummy won’t get out of bed.

There’s ice inside the kitchen window. The curtains are closed.

I soaked some crusts of bread and old biscuits in the last of the lumpy milk. It softened them. Kitty cried while she ate it. She said it made her feel sick. She said it smelled like cat pee and old socks. She giggled when she said that. Then she cried harder.

The wind rattling the window frames and whistling through the holes where the putty cracked, scares Kitty.She clutches my hand. A branch from the old tree in the yard scuffing against the glass makes her jump. It makes the same sound as the rats skitting and scurrying in the pipes.’It’s only the wind and the tree,’ I tell her.

Kitty’s my little sister. She whispers to me when she speaks. Her brown eyes look twice their size in her little face. She stares around her when she whispers as though she’s waiting from something to jump from the shadows.

Mummy can’t get out of bed. Occasionally, we hear her coughing like someone’s kicked her stomach. She reaches under the bed to scrabble for the tin can. Then she hacks, splutters. Then there’s silence.

Things were better before she got sick. She brought me to school. It was my first day and she walked me down there, wheeling Kitty in her buggy. She handed me a paper bag with two slices of crustless bread smeared with strawberry jam and peanut butter. She kissed me and ruffled my hair.

‘Be a good boy,’ she said to me ‘and do everything the teacher tells you.’

I watched her and Kitty walk away. I smiled because I could see she was talking to Kitty. I couldn’t hear what she said but I could see her crouch over the top of the buggy and shake her shiny black hair.

I scrabble around in the cupboards for something to light a fire. I rip out old newspapers lining the drawers and bunch them in the grate. There’s a few sticks left of the kindling I’d gathered in the yard and three coals at the bottom of the bag.

Kitty’s clothes are ragged and dirty. I put everything she owns on her; her ribbed black tights with the holes, a pair of dungaree shorts, an old ‘My Little Pony’ teeshirt and two skirts. She watches me from the tatty armchair next the fireplace. Her teeth rattle. She tucks her hands inside her armpits.

We used to walk through the park on our way home after Mummy picked me up from school. Kitty gurgled or girned in her buggy while I played on the swing or mummy bounced me on the seesaw.

She met her friend there, the same time, same place, every day. I pushed Kitty’s buggy down to the edge of the park pond where I skimmed flat stones and Kitty waved and giggled at the ducks. Some days, if mummy’s friend was late or didn’t show, she’d march us home, silent. Then she’d send us to our room while she smoked a cigarette and chewed her nails.

We didn’t mind. Kitty made a fort in her bed to play house with her doll, Moll and Bruno, the one eyed bear while I flicked through a book of pictures and made up stories about other lives and places. We knew there’d be a fight when Daddy got home. The shouting started after the front door closed and we heard the ‘phhssshhhh’ as he opened his first can of beer.

The match lights at the first strike. I’m glad of that. There are only three left in the box. I light the crumpled newspaper, dry as dust, and wait for the kindling to catch. From upstairs we hear the sloshing sound of the tin as it’s dragged from under the bed. This is followed by another hacking fit of coughing. Then it stops.

We wait in silence. I can feel Kitty’s slow breathing close to my face and her big eyes, hollow in her baby face, staring at the flames. The fire flickers there in those sorrowful peepers.

Daddy left five days ago. They had another fight. We sang songs in our room. The crashing was the loudest yet. Mummy was asleep on the living room floor when he came home. He told us to get out, go to our room. There was no fresh food or beer just a stale loaf, half a litre of milk, two tubs of yoghurt, some biscuits and a bag of frozen peas. He gave her money but it was gone. She met her friend in the park that day.

The door slammed shut. He was gone. He never came back.

I didn’t go to school the next day or the day after that. We heard Mummy climb into bed that night. The next morning she didn’t wake up until lunchtime. She shuffled downstairs in her old dressing gown and floppy slippers. Her eyes had sunk in her head. They looked red and angry. She hadn’t combed her hair and it was matted and flattened on one side. She didn’t speak as she slouched to the fridge. Her shoulders slumped.

‘Where’s the fuckin’ yoghurt?’ she snarled. Kitty picked up her bear and stood behind me. I could feel her little hands clasp the leg of my pants.

‘There was nothing else to eat,’ I said.

She looked at me as though she’d just noticed I was there. Then the light went out in her eyes again and she shuffled past Kitty and I. When she got to the bottom of the stairs she half turned and growled, ‘I’m sick. I’m going back to bed. I don’t want to hear a peep out of you two and don’t answer the fuckin’ door.’

She hasn’t come downstairs since. Even when there was a knock on the door in the middle of the night and Kitty, crying, woke me with her little hands shaking me and I felt her wet tears on my face. ‘Who’s at the door?’ she asked me but I didn’t know. So we stayed quiet and waited until nobody answered and the knocking stopped.

May 13, 2014

The Rigours of Writing…

Writing is about communicating, but what you wish to communicate, will determine how it’s written.

For example, if you’re a historian, writing a history of World War One, you won’t start with a blow by blow account of the violent death of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on June 28, 1914 in Sarajevo. No, you’re more likely to start with an account of the shifting complex of treaties and alliances that led the world to war and the decade of global political assassinations, leading up to that one event.

As a journalist, you’d lead with the assassination and address the questions of ‘who, why, what, where, when?’, in the first four paragraphs. The background to the story, and its aftermath, might fill the latter paragraphs as ‘background.’

As a writer, you’d go straight for the action, contrasting the pomp and ceremony of an Imperial Archduke’s visit with the sweaty, fear fuelled anxiety of a bunch of teenage anarchists, their bumbling intentions and the implications of their actions.

The historian’s purpose is driven by perspective, so by going right back to the root history of the event, he might explain why it happened. The journalist’s primary concern is ‘the news’, so the article must begin at, well, the end, or at least, at its most recent point. The novelist, however, must choose his/her point of entry, depending on their own perspective of the story and how it should be told and how it will engage their readers, if they have any.

Of course, they (the authors) start with a distinct advantage; they’re making it up. The characters, the events, the settings are all elements of the author’s imagination and they must be arranged in a fashion that will engage the reader, help suspend their disbelief and entertain them.

Shakespeare believed there were seven stages in a life but he, clearly, couldn’t reckon with the world of the 21st century, or, for that matter, the Industrial Revolution, from whence a person’s life could fragment into a dozen more stages and multi-tasking means more than scratching your arse while picking your nose.

My earliest, coherent memories, are of reading and listening to the printed word, spoken aloud. No, I was not a child prodigy poring through philosophical texts while sucking a teat. But I do remember curling up to my father, as he partook of a Saturday morning lie-in with a paperback, and asking him to read for me from whatever happened to be his chosen livre du jour. As it turns out, I have very fond memories of Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath and Harold Robbins’ A Stone for Danny Fisher. Steinbeck’s In Dubious Battle, remains for me, to this day, my favourite book of all time. He read a lot of Dickens’ too as well as his beloved Shakespeare. And for lighthearted diversion, there was Mickey Spillane.

I did my student time, learned Latin, read the classics and even tinkered with philosophy and logic, briefly, in college. But what I loved most, but for a very particular reason, was history. At an earlier age, in primary school, I became fascinated with the so called ‘Cultural Revolution’ in China. So, I wrote to the nearest Chinese embassy, in London, asking for information. Three weeks later, a crate arrived, packed with images of Mao Tse Tong, 12 copies of his ‘little red book’ (in English) and several (English) editions of the Peking Daily News. It was followed, quite promptly, by a visit from two members of the ‘Special Branch’ of the Irish police force, anxious to know who was importing Communist propaganda to a small town in the west of Ireland. It was 1968 and I had just turned 12.

Having left primary school and put primary school things behind me, including my first newspaper for which I was publisher, editor and sole reporter; I went to secondary (High) school and made my first acquaintance with creative writing, in a very positive situation. My English teacher was an enlightened individual who, apparently, recognised something in me about which I was totally unaware; I could write.

Now, I had good primary school teachers and was well schooled in the parsing and analysis of English grammar and George Orwell’s 5 rules of effective writing were as relevant then, as they are today.

Never use a metaphor, simile or figure of speech you are used to seeing in print

Never use a long word, where a short one will do

If it is possible to cut a word out, cut it out

Never use the passive, where you can use the active

Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent

He nurtured and encouraged my creative drive and suddenly, school essays were no longer chores but adventures. That didn’t last long. I left that school and went to the Big City where my English teacher was a grumpy fool and a member of a religious order. Of course, I fell foul of him, immediately. In my first week, we were assigned a choice of essay topics, drawn from the previous year’s state education exams. One of the topics was ‘Bus Queues’ and that was my downfall.

Imagining most of my contemporaries would take this topic as a ‘cue’ to recounting a series of amusing incidents and conversations ‘overheard or encountered’ at their nearest bus stop, I decided to take a completely different tack and write a pseudo-philosophical piece about how the orderly ‘bus queue’ was a micro analogy for an ordered society and how the bus shelter was a potential, even anarchic, threat to good order. The good father was not amused. Indeed, he held it at arm’s length, between thumb and forefinger, before flinging it at me. It was traumatic and I vowed to never let my genie out of its bottle, again.

Complete rubbish, you might argue, but this is now and that was then. I was 14 and already, the dream of a career I’d mapped for myself as a best selling author, was shattered. So, I turned to history, by way of refuge. Studying history teaches the discipline of research and ordered thought and you can never let your imagination get in the way of a thoroughly researched paper. And that got me thinking about journalism again, except that, after six years working in historical research, I had to re-learn how to write if I wanted to become a journalist.

It took a while to unlearn old habits but, hunger, as it’s said, is a good sauce and journalism became my bread, butter and livelihood for more than twenty years. during which I wrote about music, industry, crime, film, finance and just about anything else that put food on my family’s table.

Along the way, I wrote an unauthorised biography of Sinead O’Connor, called Sinead O’Connor: So Different, for Omnibus Press. To my surprise, it got translated into three languages (German, Italian and Slovak) and became a best seller in Ireland. Better still, the reviews, particularly by the international music press, were good and that alone, was gratifying. These days, the book is long out of print but copies are still traded on ebay and Amazon, for anything from $75 to $100, apiece.

To my surprise, it got translated into three languages (German, Italian and Slovak) and became a best seller in Ireland. Better still, the reviews, particularly by the international music press, were good and that alone, was gratifying. These days, the book is long out of print but copies are still traded on ebay and Amazon, for anything from $75 to $100, apiece.

It wasn’t until I withdrew from journalism that I began to explore the idea of creative writing again. Ironically, it was Sinead O’Connor who inspired me. Sinead and I were good friends, even if she’d opposed the publication of the biography I wrote about her. She encouraged me to try my hand at writing fiction, joking, it was what I’d been doing all along.

So I started writing short stories, just like I’d done thirty years earlier and because it was something I needed to do, I soon discovered. Writing, for a writer, I’ve always said, is akin to breathing. No writer can survive without it. Journalists are constantly on the lookout for stories. Writers are, too. Their perspective is different, however. So I began to look at the world around me through different eyes.

I also began to realise, embarking on a lifestyle of creative writing would involve a new discipline and an apprenticeship began; an apprenticeship, incidentally, without a master, at least, no tangible master apart from the inspiration would could derive from those who went before. So I began to look at other writers and all the books I’d ever written, from an entirely different perspective.

One of those writers whom I’d always admired, was Kurt Vonnegut Jr. He wrote his eight basic rules of writing in the preface to his collection of short stories, Bagombo Snuff Box,

Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted.

Give the reader at least one character he or she can root for.

Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.

Every sentence must do one of two things—reveal character or advance the action.

Start as close to the end as possible.

Be a sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them—in order that the reader may see what they are made of.

Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.

Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. To heck with suspense. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages.

The greatest American short story writer of my generation was Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964). She broke practically every one of my rules but the first. Great writers tend to do that.

I was glad he wrote the last line; rules, as far as I’m concerned, are guidelines, not mainstays. I began to read books about writing that told you to shut the doors, batten down the hatches and, if need be, tie yourself to a desk with a pen and an empty page for, at least, four hours a day or, alternatively, a minimum of 1,000 words. Of course, I soon realised many of these books are written by people who have written nothing but self help books.

The point is, you can’t dictate rules to a writer. They must find and adhere to their own rules; whatever gets the job done. It is a good idea to start with a blank page and to write down whatever comes in to your head, however nonsensical. Something will emerge, like the seed of an idea. The next job is to nurture it and help it grow. As for starting at 8am, well, I had to make a living, so I started working in a bar and those were late hours, so early morning starts were out of the question.

So I kept writing and slowly amassing a collection of short stories I was happy with but, unlike journalism, I feared to expose them to public scrutiny.

My old teacher always told me to write about what I know and my imagination would take care of the rest. That always puzzled me. How did people write historical novels or science fiction, for that matter? Franz Kafka wrote a book about New York without ever visiting the United States and it is, without doubt, the one he would’ve rather forgot. Writing about what you know is part of the learning curve; it helps hone your observational and descriptive skills.

Working in a bar, I found, exposed me to a whole new experience of people, where I could observe their behaviour, mannerisms and colloquialisms at close hand and without being noticed. It was a smorgasboard of potential stories. One of those became the title of my first, self published book, a collection of short stories called Postcard from a Pigeon and Other Stories.

Postcard from a Pigeon and Other Stories is a collection of 18 short stories about the changes transforming Ireland, from a very human perspective. There are stories about migrants, paedophiles and gay marriage; about Ireland in the 1960s and how the Cuban Missile crisis impacted on a tiny village in the west of Ireland; and about the so-called Celtic Tiger, an unprecedented period of wealth and growth when greed replaced care and hospitality. Essentially, it’s a collection of stories about change.

The short story was my route to writing, a format that is the most immediate form of fiction: it drops you right in the action, a cutaway from real life. I began writing these stories ten years ago. Many were transformed since then and even more discarded. Some of them are based on true stories but altered for artistic purposes. About half the stories were written in the last six months of 2011. It was only when I made a list of the first ten stories that I realized they followed a pattern of sorts; each story was about a human experience relevant to the past 50 years of Irish history. But just as these stories may have a geographical location, the experiences, I believe, are universal to everyone.

But I couldn’t stop there. I’d always loved reading crime mysteries and had worked my way through the complete works of Edgar Allen Poe, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Dashiell Hammett, Charles Dickens, Michael Connelly, Ian Rankin, Harlan Coben and many others.

I decided to take the story, Postcard from a Pigeon and develop it into a novel, a crime mystery novel involving international intrigue, organized crime and human trafficking. So, I locked myself away in a remote farmhouse for ten days and emerged with 28,000 words. There was no going back from there.

A story can assume a life of its own. That’s why I always loved reading the works of Flann O’Brien, many of whose books were populated by the fictional characters who were, in turn, his own creative inventions, as though they had a life outside the writer’s imagination. Kurt Vonnegut employed a similar tactic, although in a more restrained fashion to the more surreal writings of O’Brien. The point they made had no less an impact. Character can dictate a story and in the writing, it is the author who carries the burden, as well as the reins, of control.

And this is where my story steps beyond the physical act of writing into the first levels of public exposure, however limited, and all that that implies. I gave a couple of chapters to a journalist friend in London who got them into the hands of a well known literary agent. Within days of getting them, eh, the agent, turned up on my doorstep in Dublin. He was adamant about, his willingness and desire to represent me, his belief in my abilities to take my place among the top pantheon of crime mystery, NYT, best sellers.

There were, however, some catches. I would have to do some drastic rewrites and, having read the final manuscript , rewrite the ending. Ok, I thought, naively, he knows best but, as the days turned to weeks and weeks, to months, between rewrites and revisions, it dawned on me I was not the literary priority he had led me to believe I was for him. Ironically, one of the distorts on his staff who read my manuscript told me he thought it was ‘quite good’, for a first draft.

The rot had set in, unfortunately. I broke off all contact with the agent and buried in the manuscript in an old shoe box file on my hard disk and tried to forget it. Instead, I turned to short story writing, finished the ‘Postcard’ collection and went about publishing it, myself. And all these roads have lead to the publication, last month of my first novel, TITO’S DEAD.

I’ve learned a lot, like how to filter advice and criticism, how I like to write and most importantly, how to believe in myself. You should, too.

May 6, 2014

The Rules of Writing…

KURT VONNEGUT JR put it very simply. Paraphrasing him, he said, ‘there are no rules.’

Well, he didn’t quite say that but I’ve learned a lot about writing from Kurt Vonnegut. Vonnegut outlined eight basic criteria for telling a story, well. He called it ‘Creative Writing 101′. Here they are…

Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted.

Give the reader at least one character he or she can root for.

Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.

Every sentence must do one of two things—reveal character or advance the action.

Start as close to the end as possible.

Be a sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them—in order that the reader may see what they are made of.

Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.

Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. To heck with suspense. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages.

All this can be found in the preface to his short story collection, Bagombo Snuff Box. Along with the admonishment,

‘The greatest American short story writer of my generation was Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964). She broke practically every one of my rules but the first. Great writers tend to do that.’

Samuel Beckett (photo, above), a fellow Irishman, to whom every Irish writer pays homage, despite knowing very little and understanding almost nothing of what he wrote, must have broken every ‘rule’ there has ever been for the art of writing and, in so doing, devised, perhaps unwittingly, a new rule book that no-one understands.

But, both Beckett, and the writer to whom he was apprenticed, James Joyce, were meticulous in their mapping of the uncharted literary waters they chose to navigate and not, I believe, so future generations might navigate the same waters, but so they could find their own way home. They were, as Will Self outlined in a recent Guardian article on the future of the novel, http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/may/02/will-self-novel-dead-literary-fiction, already struggling with the 20th century’s nascent technological threats to the novel form. As he writes, ‘The use of montage for transition; the telescoping of fictional characters into their streams of consciousness; the abandonment of the omniscient narrator; the inability to suspend disbelief in the artificialities of plot – these were always latent in the problematic of the novel form, but in the early 20th century, under pressure from other, juvenescent, narrative forms, the novel began to founder. The polymorphous multilingual perversities of the later Joyce, and the extreme existential asperities of his fellow exile, Beckett, are both registered as authentic responses to the taedium vitae of the form, and so accorded tremendous, guarded respect – if not affection.’

Self’s depressing narrative for the demise of the novel, does have its truths. ‘Just because you’re paranoid, doesn’t mean they’re not out to get you’ is a coda he repeats, twice and to some effect.

And Self takes no prisoners; those who hail the printed word with a Luddite zeal, he dismisses as having Marshall McLuhan’s ‘Gutenburg Minds’. He outlines the physical demise of the novel as a printed format, with an accurate narrative on publishing’s own, and ultimately self destructive , drive for profits, no better described, paradoxically, in the guise of the monopolistic monolith of Amazon, but through the ’80s’ restructuring of the literary world as editors took early retirement, in face of the approaching hegemony of the literary agent.

Joyce and Beckett were faced with their own mechanical challenges but the game changers for McLuhan included telephones, cinema, radio and television. Today, there’s the infinite choice, as presented by Broadband, and the instant gratification, presented by smartphones, tablets, laptops and games consoles.

Personally, I would be interested to see what percentage of the growing world of digital publishing, particularly the so called self published ‘best sellers’, are either soft porn books or self help guides to becoming a self publishing best seller? I ask this because it appears for every person who sweats blood and tears to put themselves in print, digital or otherwise, there must be at least two dozen people to tell them how to do it.

And equally, how much academic employment has been created directly as a result of digital publishing? You’ll find ‘creative writing’ is now a taught subject from night class courses in junior colleges to the highest centres of academia. What can they teach you? Well, you’d guess that their achievement might be measured by the number of best selling writers they’ve produced. So how many are they? What, no-one knows? Hmmm

Surely, this might be because they can’t tell you how to do it, but they can tell you how NOT to do it. And, if that were true, then Kurt Vonnegut’s admonition about Flannery O’Connor’s ability to break all the rules, might be redundant. But it’s not, because the point is writing is about telling a story and while the story cannot remain the same (or else, what’s the point of telling it?), surely, how we tell it, must change, too.

Postcard from a Pigeon

- Dermott Hayes's profile

- 4 followers