Dermott Hayes's Blog: Postcard from a Pigeon, page 81

April 12, 2016

1916, Souls of Freedom

2 armies, 2 ideals, 2 ghosts, an allegorical tale of 1916

2016 is the centenary of an event in Irish history that set the template for a nation. On April 24, 1916 a handful of men and women, led by a motley group of poets, writers and revolutionaries, took on the might of the British Empire and the Crown forces, to declare the birth of the Irish Republic. For six turbulent days, they fought before they were overcome, Dublin city destroyed and more than 500 died.

In the aftermath of this disturbance, Ireland was put under martial law and within three weeks, 14 of the Rising’s leaders were tried by court martial and then shot by British firing squads. Then public opinion was charged with outrage. Public opposition to the armed disturbance turned to support for their separatist ideals and condemnation of the British government.

The blood sacrifice of the defeated insurrectionists of 1916 rallied the population to their aspiration for…

View original post 767 more words

Kevin Costner, Boers and the fighting Irish

Did the Oscar winning writer of Dances with Wolves draw his inspiration from a ‘Buffalo Bill’ style hero of the Boer War, who led the Irish Brigade against the British Empire?

Colonel John Franklin Blake was a West Point graduate and US 6th cavalry officer, with a distinguished career fighting the Apache wars in Arizona, gave up a civilian career in business and travelled to Africa in pursuit of adventure. His travels in Rhodesia, chronicled in his writings for American and London journals, made him famous.

By the time he reached Paul Kruger’s Transvaal Republic, shortly after the abortive Jameson Raid, his reputation preceded him. He was a tall, genial man, by all accounts, with ‘a Buffalo Bill look’ about him. He was a favourite with Boer society ladies and a ‘jolly good fellow‘.

The first Irish Brigade was organized, in Johannesburg by emigrant Fenian and Mayo born, John McBride but command of the volunteer Irish brigade was given to Blake, with McBride assuming the rank of Major, as his second in command.

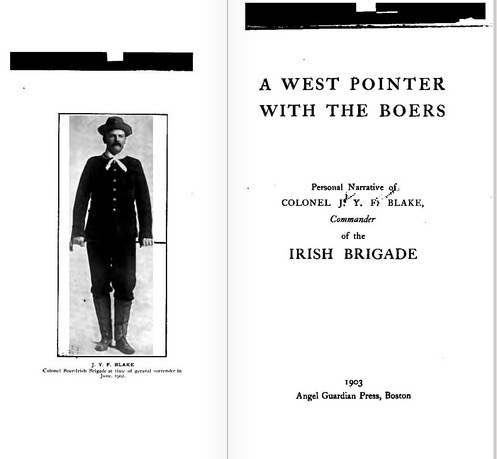

Blake later published an account of his adventures in South Africa, A West Pointer with the Boers.

Now, the reason that prompted this research was a remark made by Dances with Wolves’ lead and director, Kevin Costner, on the Graham Norton Show.

The writer, of course, was novelist and screenwriter, Michael Blake, who went on to win an Oscar for his adaptation of his own novel, Dances with Wolves. Now Costner’s version of the story of their relationship was slightly truncated, probably because he’s told the story so often but also because he wanted it to fit in to the context of the point he was making.

In essence, while telling the story of how his most successful films he ever made were first rejected by Hollywood and then, through his own belief, sacrifice and efforts, they became hits. Blake was a writer he’d known since the, then unknown Costner, appeared in the Blake written, Stacy’s Knights, in 1983. Then, while Costner’s career began its rise and rise to the pinnacle of his first Oscar with Dances with Wolves in 1990, Blake’s career remained so much in the doldrums, he was sleeping on friends’ couches, Costner’s in particular.

It was then that Costner exercised some tough love and told his friend to stop bitching and moaning and get out there and get writing. In particular, Costner encouraged him to work on the screenplay of his own, relatively forgotten novel, Dances with Wolves, an account of a US cavalry officer, living alone in a frontier wilderness and befriending wolves and native Americans.

And that was the trigger for me, because I had read Colonel John F. Blake’s A West Pointer with the Boers and remembered, in particular, his introduction. Although born in Missouri, Blake’s family moved to Texas. And there, he wrote, ‘I first saw light, as far as I can remember.’ Growing up on a cattle and horse ranch he became ‘fairly well acquainted with the character and habits of horses and cattle,’ he wrote, ‘happy were those days of loneliness and ignorance spent on those far stretching plains, where roamed hundreds of thousands of horses, cattle and buffalo.’If you close your eyes, you can almost envisage scenes of wide open plains and charging herds of buffalo, as in Dances with Wolves.

Blake then went to Arkansas University before getting a cadet commission to West Point, graduating as a second lieutenant in 1880. His first commission was served in the Arizona Apache wars. Under General Crook, he was put in charge of the Apache scouts’ division, with which he ‘roamed about the mountains’ until 1885. After a short spell in cavalry training in Fort Leavenworth, he was promoted to 1st lieutenant and posted to New Mexico, where he was put in charge of Navajo Scouts. After four years there, he got bored and quit the army.

So take this a step further and have a look at some photos of Colonel J.F. Blake and Hollywood screenwriter, Michael Blake.

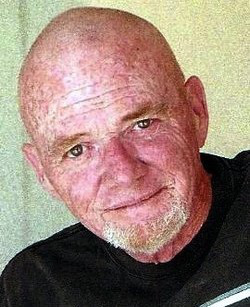

Michael Blake, writer

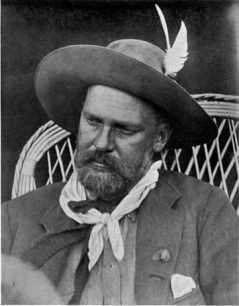

Colonel J.F. Blake

Taking this a step further and this is just conjecture, since I have no definitive confirmation of the relationship between the two, but one of Michael Blake’s subsequent novels, Into the Stars, tells the tale of a soldier in WW1 and his relationship with his horse when they find themselves stranded in No Man’s Land and have to find their way home, to safety. The young soldier’s name is Ledyard Dixon and Ledyard, by coincidence or design, was also the name of Colonel John Blake’s son, born in 1889.

Of course, this could all be a load of rubbish. Michael Blake, the author, was born Michael Webb and took his name as a writer, from his mother, Sally Blake. He also told interviewers, following the success of Dances with Wolves, that he first became inspired about the plight of American Indians by reading Dee Brown’s seminal, ‘Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee.’

Michael Blake died, last year, in Tucson, Arizona, at the age of 69 after a long illness. He was acclaimed, not just for his writing, but also his humanitarian and environmental work on behalf of Native Americans and America’s wild horses. I have written emails to his estate in an attempt to find out if there is, or ever was, any connection between the two Blakes. If you have any information, let me know. I hope, if nothing else, Michael Blake would find this story amusing.

April 8, 2016

Poisoned Chalice

A FF/FG coalition is a poison chalice from which neither of them will drink. Now both parties are damned if they do and damned if they don’t, while Sinn Fein can sit on the sideline and watch their rivals tear each other apart.

National interest, for either party, is not just that one of them takes power but that the two of them keep the shinners at bay, while maintaining their own political identity.

This, of course, in the treacherous shifting sands of Irish politics in recent years, is easier said than done.

For a start, the wholesale and rampant greed, manifested and celebrated as, the Celtic Tiger and the subsequent fall to earth, with a resounding and still reverberating thud, has, at least, had a cathartic effect on the body politic and woken it, like a long term coma victim, from a sleep that began, ironically, in 1919.

That ideological stasis, since known as treaty politics, has blinded people to the realities of politics, the haves and have nots. Instead, it has become a near century old, tribal struggle for power at all costs and often, by any means.

Realpolitik in Ireland, today, is in the proliferation of Independents who, in one form or another, display, identify and reflect, the ideological leanings of their supporters. Many of them have been elected on the strength of single issues, like anti-water charges, but they are, more simply the genesis of a new political landscape.

This is why Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael are caught in a dilemma since both are soaked in and imbued with the belief and only they, whichever one, represents the true ‘national interest’ and a coalition of the pair is as impossible as mixing oil and water, a denial of their individual raison d’etre.

To compound their problems is the rise of Sinn Fein, a party that tries to present itself as both left wing and republican, for intents and purposes, a Fianna Fáil without shiny suits.

April 6, 2016

Away with the fairies

Justin Bieber has dreadlocks. Away with them, string him up, cast him out. And while you’re at it, leave our leprechauns alone. I’m fed up of people claiming to be Irish, dressing up in green clothes and drinking green beer so they can say ‘top o’the mornin’ to ye’ and get drunk on St Patrick’s day.

That’s cultural appropriation, isn’t it? Not if everyone does it, apparently, even when they’re a boozed up Stag party in green hats and ‘funny’ red beards and hair. But hey, we don’t have a copyright or intellectual property rights on drunkenness, red hair or pots of gold, for that matter.

Justin Bieber’s sporting dreadlocks and the whole world’s up in arms but hey, it’s just a hairstyle or is it? Not, according to a black student in California, who, physically, confronted fellow student, Cory Feldstein, who is white, because of his ‘locks.’

Of course, if you look at the history of ‘locks’, you’ll find it has, er, roots going right back to ancient Egypt. Hindu mystics, the Sadhus, wear their hair in locks as part of their religious detachment from the material world. Ancient Celts and Vikings wore their hair in locks. They’re even mentioned in the Bible, if you want to check out Samson and Delilah.

Bieber, of course, is not the first, white and wealthy, western artist to ‘appropriate’ another culture for their own gain. Madonna came under fire for ‘appropriating’ ‘vogueing’ from the black and Latino New York gay culture; Katy Perry pissed off many Asians when she dressed up as a geisha for the video of her single, Unconditional. Paul Simon got raked over the coals for apparently flaunting the cultural boycott of apartheid South Africa, with his album, Graceland.

And while we’re at it, let’s burn effigies of Elvis and The Rolling Stones for ‘appropriating’ the blues and gospel. But hang on a minute, there. Surely modern pop and rock culture owes as much to country music and European folk music? I remember having a conversation with Mac Rebennack , Dr John, about that very subject. Now, Rebennack, apart from being a well respected artist in the jazz influenced tradition of New Orleans’ blues culture, he is also a recognised expert on the melting pot roots of that Louisiana music that draws as much from its black slave roots, as it does from the Acadian music of Canada and Irish music, drawn from the denizens of New Orleans’ own, Irish Quarter.

The ‘appropriation’ of black music, whether it was by the Chess family, the Rolling Stones or U2, hasn’t done that music or the artists who played it, any harm, either. Indeed, if it’s true all ships float with a rising tide, then ‘black’ music has benefited, largely, by the aforementioned ‘appropriation’.

Indeed, I remember, distinctly, the cover of an Ice T, gangsta rap album, from the early ’90s, called ‘Home Invasion’, with its illustration of a young, white, middle class suburban child dressing like a ‘homie’ and listening to rap to the horror of his parents. The inference was obvious: this was a ‘cultural appropriation’ that has provided black comics plenty of fodder for ridicule, while lining the pockets of all those gun totin’, Cristal guzzling rappers

That’s all very well, the culture police might argue, but ‘dreadlocks’ are a special case because of their connection to an obscure Jamaican religious movement called Rastafari and their symbolic use in the rejection of cultural, economic and physical slavery that has, in turn, been appropriated as a general symbol for black culture, in general.

So there’s a whole lot of ‘appropriating’ going on, much of it with a strong argument but no unconditional right of ownership that I can see. Perhaps, if such inappropriate fashion statements like Justin Bieber’s hairstyle, were termed ‘misappropriations’, there might be a stronger argument but until then, like the Irish and ‘our’ leprechauns, well, it’s away with the fairies, isn’t it?

April 3, 2016

Old, for new, bones

“A gas leak? Are you fuckin’ joking?

“A gas leak? Are you fuckin’ joking?

No-one’s going to believe that.”

“That’s what I was told. And that’s how it is. Shut the site down and send them home now. Tell them to report back in two days.”

“And that’s it?’

“No, there’s more. Yourself and Seamus, stay. Wait for me. Go’n’ave a pint, have lunch. I’ll talk to you in a few minutes.”

The twins shrugged and turned away, throwing their hard hats on a bench in the corner. Seamus grabbed two coats, rough wool, dark blue donkey jackets, hanging from a nail beside the door and tossed one to John, his older brother by two minutes.

Neither spoke until two pints of Guinness stood in front of them. The pub was a short walk from the site. It was an old pub with brass and copper pipes and water stained mirrors faded with age. The wooden floor was pitted and creaked as the lunchtime crowd spilled in. The bar shone with a veneer of spilt beer and a couple of centuries of furniture polishes. Old wooden pews, John suspected were castoffs from the church, lined the walls.

John broke the silence.

“I don’t like it.”

Seamus said nothing. He stared at his settling pint. John studied the straight, glass pot of black beer in front of him, his brow furrowed like the neat stack of folded napkins on the bar.

Seamus waited. John picked up his pint and squinting, sank his upper lip into the froth of creamy stout and tilted his head back, his Adam’s apple bobbing, once, twice, as half the beer in his glass disappeared. Seamus followed suit, watching his brother.

John set his pint down hard on the wood counter, stained and shined by elbow grease and slops down the years. The beer sloshed from his glass. It made Seamus jump. He set his own glass down carefully on a beer mat, using both his big, gnarled, navvy hands.

“I don’t fuckin’ like it,” John said again. He stared at his feet as he leaned into the bar, both hands stretched out before him for support. His anger commanded a presence in this Dublin saloon as office workers, shoppers, tradesmen and builders crowded in for lunch.

John was not a big man. They were both of average height and build, 5’9″ in their socks and though, in their civvies, they’d pass for ‘slight’, it belied the hardness of their physiques, sculpted by a lifetime of labour; first on their father’s subsistence farm in the west and since then on building sites around the world like Boston, USA; Perth, Australia; Hamburg and Berlin in Germany and, of course, every corner of England. They’d built bridges and skyscrapers, dug tunnels and canals, sometimes in blistering heat but more often in freezing cold and driving rain. They worked hard and played harder. They drank, like any other navvy, for companionship and to hold the lonely nightmares at bay for a Western sunset in Perth might look spectacular but it could never look the same as an Atlantic sunset from Doolin.

Money was never a problem but when they collected their wages, no matter where they were, the first port of call was the nearest Western Union office and a cash transfer to the sub-post office in Darragh, Co Clare. The money was for their widowed mother who lived alone in the old cottage, surviving on her sons’ cash and an old age pension.

Their duty discharged, they hit the pubs, the greasy spoons and back alley dives. Seamus and John were identical twins but John, being the elder by two minutes, always led where Seamus followed. Seamus knew his brother well. He knew John broods and fumes when something bothers him. It was like standing by a smouldering volcano.

“Is this about the bones?” Seamus asked. John’s gaze was downwards but at no fixed point. His shoulders were hunched, the muscles tense. He waited. He always waited. It was body language only they understood. When they got in fights, John threw the first punch but Seamus was always ready. Even if he started the fight, John threw the first punch. Seamus saw it coming and Seamus backed him, to the finish.

“There yiz are,” Costello the foreman came through the door, interrupting anything John might say, “sorry I kept ye waiting. Did ye order me a pint? did ye get something to eat? what’s the soup, today? Give us a pint of stout, are ye ready for another, boys? I can only stay for the one.”

John stared at him. Seamus knew the look. He got between them, saying, “no, we’re grand. We’re only in the door ourselves. We were just chattin’, we haven’t had a chance to look at the menu.”

“Ah, that’s fine, so. will we sit down?” Costello, oblivious to the tension, picked up the still settling pint the bartender placed before him, and marched off to a vacant table in a corner of the bar, just below a stained glass window where the afternoon sunlight cast a red and yellow shadow across the floor.

John picked up his pint, staring after the receding figure. He took a contemplative swig and swallowed. Seamus picked up his pint and nudged his brother forward.

Costello was studying the menu when they sat down. “The measure of a good pub is the quality of their soup. That was my father’s contention, anyway and he’d walk a mile through a blizzard for a good bowl of soup and a heel of fresh bread.”

Costello’s like a crab, John thought, he approaches everything sideways. He watched the foreman’s eyes shift around the room while he took everything in, the measure of everything and the value of nothing, he thought. They’d known each other all their lives, grew up in the same rural backwater in Clare, went to school together, played on the same hurling teams. When they worked on sites in London, it was often Costello got them their start. He wasn’t a great grafter but he always had the ear of the boss, the site foreman, the subcontractor. He could talk up a storm, never said ‘no’ and always knew someone ‘who could do the job.’ It was Costello persuaded them to come back to Ireland. “Buildings are going up here like ragwort in a meadow,” he said, “they’re screamin’ for good workers, the pay is good and there’s plenty of overtime.” They were on a site the day after they came home, excavating a foundation for a new apartment block. Costello got them the job. He was their foreman.

“We have to move the bones out of the site. Any delay could destroy us,” Costello said this while he studied the bar menu. He looked up when the waitress stood before him, “what’s today’s soup?” he asked. John and Seamus gawped at him. He ignored them, concentrating his attention on the young girl before him who had that out of date, bleached blonde, feather cut, mullet look of someone from eastern Europe.

“Tomito and roast rid pipper,” she said.

Costello’s eyes stayed fixed on her face.

“What?” he asked.

“Tomato and roast red pepper”, John said, interrupting.

Costello looked at him like he saw him for the first time. John was growing impatient.

“Right.” said Costello, “I’ll have a bowl of that with a heel of brown bread, if you have it? D’ye want anything?, he asked the twins. John dismissed the idea with a wave of the back of his hand. The waitress walked away. John noticed the ladder in her black stockings.

“What do you mean ‘we’ ? We don’t want anything to do with this.”

“John, I won’t see you wrong. How long have we known each other? Didn’t I get you the jobs in the first place…I just need this one favour. Ye’ll be well paid for it.”

“We didn’t sign up to move bones from a church.”

“It’s not a church anymore. It’s been decommissioned or deconsecrated or whatever they call it. If the bones were important to them, they wouldn’t have left them behind them, would they?”

“Moving them is still wrong,” John said, “it’s illegal, isn’t it?”

“It’s fucking illegal to stop people working, ” Costello spat back, his chin thrust out, one eye squinting at the twins. Seamus hadn’t said a word. He let John do the talking.

Costello tried to stare John down but broke off with a shrug.

“Look, ” he said, “this business has turned cutthroat. There’s a lot of competition out there and ye’ll do anything to stay ahead.” He looked at John as though he expected him to fold. John said nothing, his stare fixed on Costello’s face.

“Our last two jobs were held up. We went over the time limit in the contract and they started costing us money. We can’t afford to let that happen again. We’ll go belly up…you’ll be out of work. Them Polish boys are good workers.”

“Is that a threat?” asked John. Seamus sat up. He watched Costello, his fists bunched.

“We’re subcontractors, for fuck’s sake. We’re subcontracting to the main contractor. He gets the job and pieces out the work. If we don’t get finished on time there’s a penalty clause on us, not the contractor. Finding bones or pots or a Viking’s shit pot means an archaeological impact survey has to be done. That takes time and it costs money, more money than we can fucking afford. D’ye get it, now?”

“Ye’ve lost your souls, that’s what I get…these are human bones and we’ve dug them up. They deserve a proper burial,” John spat back at him.

He stared around the room as though the answer to his questions were hidden in the bar’s brass footrail, the water stained mirrors or the nicotine shaded plasterwork. “Ye spend yer life building but only in Ireland will it bring ye back to politics,” he thought.

“What did’ye say?”, Seamus asked him.

“Nothing,” John said.

Costello studied him. He paused. There was a glint in his eye.

“I agree with you. They should have a proper burial. But we shouldn’t have to pay for it. If we take them out and bury them tonight, no-one will ever know. It won’t cost us a thing and we’ll all keep our jobs.”

“He has a point, John,” Seamus spoke for the first time. John looked at his twin like he’d been stabbed in the back.

“Not you as well. What the fuck is going on? I don’t believe we’re even having this conversation.”

“It’s a dog eat dog world, John. If we’re out of work we might have a job getting another when they’re hiring more foreigners that’ll work cheaper.”

John stared at his brother in disbelief unsure whether what he said shocked him more than his brother putting more words together than he’d heard from him in his life.

“Jesus,” he muttered before picking up his pint then paused to stare into it before he drained it and smacked the empty glass on the table. “How will we do this?” he asked.

Costello smiled and called for three more pints of stout. Then the three of them huddled close.

Four hours later they were in Costello’s Land Rover pulling an open trailer of bones covered with a tarpaulin, through the southern suburbs of Dublin.

“Are we nearly there yet?” Seamus asked.

“You sound like my kids when we drive to Brittas. It’s at the end of this road. We’ll go in the back way so we don’t draw attention,” Costello said.

“What is this place?” John asked.

“It’s another job we have on except this time we’re putting in the foundations instead of excavating them like the last job. So, it’s like we’re burying them again. There’s no harm done.”

“I can’t believe we’re doing this,” John said, staring blankly out the window at the passing houses.

“Ah, don’t start that shite again,” Costello barked. He swung the Land Rover through an open gate on what appeared to be a closed site.

“Is there no site security?”, Seamus asked.

“He’s one of ours,” Costello answered, ” I called ahead. He knew we were coming. He’ll stay out of our way .”

Costello was true to his word. One hour later they were finished, six large sacks of bones dumped in the foundation of the new site with two dozen bags of gravel dumped on them. They piled back in to the Land Rover. They were silent, exhausted. John felt little satisfaction from the job they’d done. He knew Seamus was right. They needed to keep working so they could send money home to their mother. They couldn’t afford a conscience. It was a luxury.

Costello drove the Land Rover and its empty trailer out through the site’s front entrance, slowing to wave at the site security, a black man hunched over a metal bucket aglow with warm coals.

John read the site project banner above the front entrance with its list of contractors, engineers and architects and the legend of the project itself, ‘site of a new Mosque’. He didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. He felt like he’d buried part of himself.

March 31, 2016

A nation once again? When where we ever?

The amount of hoohaw and guff spouted about the Easter Rising and the Proclamation in the past week has stuck in my craw. There’s been an element of measured keening for the revolutionary dead, tempered by some fawning nods of reconciliation to those who continue to deny the legacy of that event.

Most of the videos we’ve seen about the centenary have dwelt on the diaspora, with many of the Irish people chosen to recite excerpts of the Proclamation against the background of their foreign homes, without a hint of irony regarding the circumstances that drove many of them to seek a life abroad, their own nation could not give them.

Then Centenary, the RTE show in the Bord Gais theatre, has been proclaimed as ‘a new Riverdance moment’, that, for some odd reason, reminds me of Kurt Vonnegut Jr’s unfulfilled novelist, Kilgore Trout, who could only get published in porn magazines and one story of his, in particular, about an alien who landed on earth beside a suburban house that was on fire. So, when the alien woke the family to warn them of their imminent danger, he could only communicate, in his alien way, by tap dancing and farting and got knocked down, dead, by the father of the house, wielding a nine iron.

The show was, without a doubt, a triumph, but I did wonder why the second chapter, the building, included a Ewan McColl song, ‘School Days Over’, about the plight and working lives of miners? Was someone having a laugh? Of course, it might’ve been an ironic nod to the thousands of Irish who left the new nation to find work because there was none here and who spent their lives as navvies on British roads, buildings and canal ways.

And where was Christy Moore, once hailed the ‘storm in a tee shirt’ and ‘the national conscience’, was he asked to take part?

Last year, when a friend of mine (Gary Kelly) approached me with a screenplay for a 1916 themed short film, I took it on with him, as a worthwhile project to make a statement about 1916; first, that were two armies in the Rising and two ideals pursued in the Proclamation but secondly, that 100 years after the Rising, those ideals have not been achieved and the ghosts, of those who fought, are still with us.

So, when a relative of James Connolly suffers abuse at the hands of a narrow mined, nationalist, bigot at a commemoration ceremony for relatives of people who fought in the Rising and a young woman, Irish, but not white, should ask, ‘why is that still a problem, 100 years after the Rising?, then we must ask ourselves, are we a nation, were we ever and what does that mean?

These same points have been reiterated also daily, in the past fortnight. Here is a variety of them, from all sides.

Rewriting History

An open letter to the Government and people of Ireland, by Emma Lock

March 30, 2016

Indelible Echoes

This poem is about memories and how they can be triggered by chance experience. I revisited this video, recently and here is the result

A harbour breeze,

a mountain spring,

rain, the scent of heather,

a hazel copse,

freshly cut turf,

crickets in the thatch,

laughing spuds,

sizzling mackerel

and periwinkles,

sand in your toes

and the salty brine

of seaweed,

a sunburst

of glorious colour

in my mind.

Indelible echoes

of a life

tread with memories

without footprints

March 25, 2016

1916, Souls of Freedom

2016 is the centenary of an event in Irish history that set the template for a nation. On April 24, 1916 a handful of men and women, led by a motley group of poets, writers and revolutionaries, took on the might of the British Empire and the Crown forces, to declare the birth of the Irish Republic. For six turbulent days, they fought before they were overcome, Dublin city destroyed and more than 500 died.

In the aftermath of this disturbance, Ireland was put under martial law and within three weeks, 14 of the Rising’s leaders were tried by court martial and then shot by British firing squads. Then public opinion was charged with outrage. Public opposition to the armed disturbance turned to support for their separatist ideals and condemnation of the British government.

The blood sacrifice of the defeated insurrectionists of 1916 rallied the population to their aspiration for a free Irish state, independent of the British Empire.

Within two years, Sinn Féin (Ourselves Alone), the political party that championed their ideals, swept up more than 90% of the seats in a general election and then refused to take their seats in the British House of Commons. Instead, they established the first Dàil, a separate Irish parliament and declared their independence.

Two years of armed struggle ensued as the British sought to quell this new challenge to their hegemony in Ireland but the republicans had learned their lesson from the slaughter of 1916 and fought a guerilla war. By late 1921, overtures for peace were made and by August, 1922, a treaty was signed and the Irish Free State was established.

The treaty brought with it many headaches. Its terms, a separated Ireland of 26 counties with six northern counties retaining membership of the United Kingdom, brought bitter division between the forces that had fought for independence and a bitter Civil War followed. Those divisions have remained central to the political culture and history of the following century.

Anything that followed, including the declaration of an independent Irish Republic and the subsequent turbulence in Northern Ireland, has been defined by the aspirations expressed in the 1916 Proclamation. This created an anomaly in the political identity of the country, as though anything that followed has been measured against the political aspirations of a tiny group of revolutionaries, motivated by their own beliefs and without any popular, democratic mandate.

Those revolutionaries were made up of not one, but three, revolutionary groups. First, there was the Irish Republican Brotherhood, a secret revolutionary group within the Irish Volunteers, that traced its lineage back through a century of clandestine insurrection. Second, was the Irish Citizen Army, an armed force established in 1913 by revolutionary socialist and trade unionist, James Connolly, expressly to defend striking workers against the repressive actions of the Dublin Metropolitan police. Connolly was recruited into the IRB and was a signatory of the 1916 Proclamation. Finally, there was Cumann na mBan, a paramilitary group of Irish women that became an auxiliary to the Irish Volunteers who fought in 1916.

Left to right, clockwise… Dublin brigade of the Irish Volunteers, Irish Citizen Army, Declaration of the Irish Republic, badge insignia of Cumann na mban, the Irish women’s auxiliary of Volunteers

The involvement of these three separate groups informed the aspirations and ideals of an Irish Republic expressed in the Easter Proclamation.

This year Ireland is commemorating the 1916 Rising but even the nature and style of the commemoration plans have been fraught with controversy. The Government’s initial plans were attacked by historians who accused them of trying to write the revolutionaries and what they stood for, out of the picture. The coalition government, on the other hand, is made up as it of a majority party that traces its origins back to the pro-treaty forces that established the Free State in 1922 and a Labour party whose own history and political development has been stunted by Connolly’s actions in subsuming the socialist revolutionary aspirations of his own movement into the drive for a separate, nationalist state, effectively turning their role in the Irish Republic’s political development into little more than a footnote.

And ranged against them is Fianna Fail, the old guard party of anti-treaty forces and the modern day, Sinn Féin, a political force grown out of the nationalist armed struggle of the past 40 odd years and more, in Northern Ireland. Of course, to complicate things further, neither of these opposition parties could acknowledge their common ground as to do so could diminish their own proprietorial claim to the legacy of 1916.

It’s as though, while the rest of the world goes about existing in the 21st century, Ireland struggles with its own political identity, stunted by a debate that began with an armed revolution, 100 years ago.

So, all these things considered, myself and some friends, decided to adress these issues in a short film drama. In our film, 1916, Souls of Freedom, two Irish republicans; one a wounded officer of the Irish Citizen Army, the other, a young, Irish Volunteer; find themselves hiding in an abandoned house in Dublin in the final days of the Easter Rising, 1916. But as the film ends with them meeting a bloody end, we realize it is not 1916, but 2016 and these two combatants are ghosts, trapped forever in their own past and tragic end, some moments echo forever.

Left to right, shooting 1916, Souls of Freedom; actors, Paul Ronan and George McMahon, cast and crew, on location

March 21, 2016

Same History

Seamus Dempsey was cleaning a gutter at the front of his house when the Special Branch came for him. It was a job he’d been putting off for some time. But it was a bright summer’s day, a Saturday morning and there wasn’t a cloud in the sky. He had the day off and Eileen, his wife, had woken him that morning, briskly yanking the bedroom curtains apart and letting the sun’s rays rouse him from his slumber.

‘Get up out of that,’ she’d said, ‘that’s the first fine day we’ve had in a month and it would be sinful to waste it. Will you tackle them gutters before they collapse from the weight of the leaves in them and the house gets flooded.’

Blinking and groaning, Seamus feigned exhaustion but he knew from her manner it was a wasted effort. He hauled himself from his bed, swinging his pyjama’d legs over the edge and scratched his head. Yawning and stretching, he felt the shadow of Eileen leave the room and dropped back onto the bed for one last bask in the bed’s cotton warmth.

‘I’ve left your overalls in the bathroom and clean underwear,’ her voice found him, ‘you can have the job done before lunch and we’ll make the one o’clock train and be at the church for two.’

Seamus cursed silently. He’d forgotten the church, a Christening and Eileen had accepted the invite. Their daughter, Maire, was standing for the child as Godmother and the family had invited them along. It would be a long day with a train journey, a meal and possibly a few drinks by way of wetting the child’s head.

He had planned another journey that afternoon and the Christening had completely slipped his mind. There was to be a march to protest the seizure of the remains of a hunger striker sent home from an English prison. He’d have to forget about that now, he thought, as he ran the hot water in the bathroom sink so he could have a shave and wash before he got dressed and tackled the gutter. DIY was not his strongest point and he was the first to admit that. He had been looking forward to a morning in his garden. He surveyed his pride and joy from the bathroom window as he was shaving.

Everything was in growth and there was plenty of weeding to be done. The early potatoes were showing blossoms and he’d be ready for the first crop in three or four weeks. By that time they’d have a good range of summer salads ready for harvest; lettuce, cucumber, radish and tomatoes. If the weather stayed good they’d have everything for the annual Dempsey family midsummer feast including a whole fresh salmon ordered from his old poaching contacts in Donegal.

‘Your breakfast is on the table and there’s fresh tea in the pot,’ Eileen’s voice broke his reverie, ‘I’m away to the shops. I’ve meat to pick up in the butchers and we need eggs. Oh, and I’ll get the ‘papers, too.’

He heard the front door slam shut behind her as he finished dressing and came down to start the day. He poured himself a cup of tea and absentmindedly buttered a slice of brown bread. His mind was distracted by the prospect of missing the march.

There was only so much a man could take before he had to stand and object, he thought. He was not a political man by nature. He kept himself to himself and his family and he kept his opinions to himself too. But there were limits, he told himself. He had marched on the British Embassy after Bloody Sunday. But then, he thought, so had half the city.

Hundreds of thousand of people had stepped out onto the streets of Dublin that day to march in protest to the embassy over in Merrion Square. There were so many people and the crowd was so dense his feet had left the ground in the surge somewhere around the Taj Mahal and only touched the ground again beside the Mont Clare hotel. He’d come the entire length of Clare St as part of a flowing tide of human anger to protest at the death of 13 Irish people, unarmed and protesting peacefully at the hands of the hated British Paratroop regiment in Derry the previous Sunday.

That experience had scared him. He had felt scared by the force of emotion and the terror it engendered. He had felt the anger himself and felt how it had ennervated him and spurred him on with all the others. And he had feared the anger of the mob that teetered on irrationality and threatened to unleash a terrible retaliation. He saw it in the eyes of everyone around him, smelt in from their collective breathing and the rage of fury that rippled through the marching crowd.

He had left the march then, struggling his way against it and towards the Dental hospital so he could slip down Westland Row and catch the five o’clock train home from Pearse Station.

Pearse, he thought as he stood and waited on the northbound platform, the furious roar of the massive crowd beyond in Merrion Square clearly to be heard, there was a name to conjure with along with McDonagh and Kent, Plunkett and Clarke, McDermott and Connolly. Irishmen like many hundreds of unsung martyrs before them and since who had fought and died for the cause of Irish freedom against the might of perfidious Albion and the forces of the British empire. That was the history he had been taught with pride, a history steeped in blood and sacrifice.

He and those who came after them had inherited their legacy of a free, independent and sovereign Democratic Republic. Seamus was born in the same week as the Treaty was signed, the treaty of 1922 that ended the so-called war of Independence, the fight for Irish freedom. That same treaty turned brother against brother and neighbour against neighbour and… A time check on the morning radio telling him it was ten o’clock snapped him back to the present.

Seamus soaked the remains of his fried egg with a forkload of black pudding and the heel of brown bread he loved to eat with his breakfast. He drained the last of his second cup of tea made from loose tea leaves and brewed strong. ‘Right, I better tackle those gutters,’ he thought, glancing at his watch to calculate Eileen’s estimated time of return. ‘I’ll never hear the last of it if I’m not up that ladder and upto my elbows in leaf mulch by the time she gets here,’ he told himself. He squinted at the sky before he went outdoors. The weather looked like it was holding. The sky was clear. He decided not to wear his jacket but he couldn’t resist putting on his old black beret, a boyhood affectation that had never left him.

Outside he pulled the ladder from under the tarp in the passage between the garage and the adjoining neighbour’s wall and levered it over the garden gate into the driveway. Then grabbing a galvanised bucket and a small hand trowel and fork he opened the gate and went outside. It was best to start above the adjoining wall of their semi-detached home, he thought and work his way along to the drain that ran from the gutter to the ground flue. That way, he thought, he could clear all the mess in the gutter, give the roof tiles a once over and some running repairs if needed and then clear the runaway drainpipe.

It wasn’t rocket science but it was necessary, a routine maintenance chore that he detested. He extended the ladder until it rested just half a foot below the gutter and then secured the foot of the ladder with a hefty breeze block he carried from the side of the house.

A mild refreshing gust whispered around the eaves as he carried his bucket and tools to the top of the ladder. It gasped a cherry blossom scented ‘good morning’ and brought a jaunty tune to his head.

…’when boyhood’s fire was in my blood, I dreamt of ancient freemen, of Greece and Rome who bravely stood, three hundred men and three men…’

The gutter was a mess, choked to overflow with leaves and ancient rain and silky black muck, the detritus of a winter of neglect.

Seamus set about his task with cheery determination, whistling tunelessly of Clare’s Dragoons and Katie Daly, hacking at the muck with the short garden fork and scooping it in messy dollops into the galvanised bucket hanging from a hook on the side of the ladder.

His mind wandered back to the day’s protest march as a dark cloud of anger and shame began to mist his day. He had never fought in any war nor carried a weapon in defence of a cause, he thought, but he had served his country as a loyal and patriotic public servant, proud in the belief that he had done his share for his country through loyal service. Now he felt betrayed, insulted, robbed and oddly confused.

‘Seamus…could I have a word with you?…Seamus?’

The voice of his neighbour, Mick McCarthy, disturbed him from his thoughts.

‘Ah, how’re ye? Mick, how’s it going? Grand day, thank God.’

‘It is, it is…I see Eileen has you at work…that’s the start of it now. I’ll be up a ladder myself once herself sees you hard at it…eh…’

Seamus knew Mick had more to talk about than the weather by the way he hesitated and lingered at the foot of the ladder. He looked down at his neighbour of ten years, shuffling distractedly in the front driveway, reluctant and hesitant.

‘Is there something on your mind, Mick?’ he asked, ceasing his digging for a moment as he squinted enquiringly at his neighbour, a detective sergeant in the Special Branch.

‘Could I have a word with you, Seamus?’ Mick asked, shooting a swift glance at Seamus on the ladder before looking away into the middle distance.

Seamus dropped the trowel into the bucket and began his descent, musing all the while at his neighbour’s discomfort.

‘What’s up, Mick? You look as though you’ve stepped in something.’

‘Seamus, …a file came across my desk the other day with your name on it. You’ve upset someone high up and they’ve asked us to look into you…now I know you this ten years and our children are all in the same schools and our wives do their Easter dues together and…’

‘Is this about the march today?’ Seamus asked.

‘Ah Jaysus, you’re not going on that, surely?’ Mick said, dismayed, ‘no, it’s not. It’s about you scaring the living daylights out of a couple of respectable middle class women who were out doing their political duties last week…’ Seamus chuckled. He remembered them well.

‘Grave robbers,’ he called them when the two middle class ladies canvassing for the local politician in the coming election had approached him at the hustings. They were canvassing the neighbourhood for the incumbent Minister only one week before and on the same day the police had seized the coffin and remains of the hunger striker sent home from a British prison. They took his body and denied him his right to a hero’s burial. It was an outrage, Seamus said. ‘Bloody grave robbers,’ he fumed at them. The ladies fled from the door in turmoil and shock.

‘For Heaven’s sake, Mick, have you nothing better to be doing than wasting your time with that…aren’t I entitled to express my opinion? Is this not a democratic state?’

Mick wasn’t laughing and his grim clouded face choked the laughter in Seamus.

‘It’s no joking matter, Seamus,’ he growled, ‘these are strange and dangerous times we’re living in and you may be entitled to your opinions but you should be more careful who you express them to…as far as I am concerned this matter ends here. We were all taught the same history, it’s just the people who teach it and the way we learn it that changes.’

They both stood in the driveway, silent and awkward.

‘How’s Mick?’ Eileen asked as she walked up the garden path laden with shopping bags, ‘are you holding him from his work? It’s taken me two months to get him up that ladder…’

‘Ah how’re you, Eileen?,’ Mick said, too grateful for the interruption, ‘I was just saying to Seamus ‘tis a grand day for it too but I wish he hadn’t started because herself will have me climbing the walls as soon as she sees him.’

‘Somebody has to take ye in hand or nothing would ever get done,’ she replied, laughing.

The two men exchanged one last glance before Seamus turned and climbed the ladder again.

March 15, 2016

Donkey Race in Lixnaw

I knew none of my companions before that evening. Yet here we were, all five of us, striding with intent, to our common destination.

A full moon swung in the air like a bare bulb swinging in a dingy pub toilet. The path underfoot was wet and slimy from that evening’s summer downpour, treacherously slippy from the sodden daily grime of a country town’s streets, chip grease, spilt beer, puke and chewing gum. We trudged along purposefully and, it must be said, tipsily.

We were seeking arbitration and judgement on an issue that on a summer’s evening in a small town in north west Kerry raised issues as fundamental as birth and birthright. There was close to €750, in side bet stakes, involved too.

* * * * * * *

It’s amazing what a night of drinking and carousing can be had from a summer’s night in a country pub with a town festival and carnival in full swing. The posters we spotted promised as much. It was the ‘Welcome Home to Lixnaw Festival incorporating (intriguingly) An Cailin Ailinn na paroiste’ (Lovely Girl of the Parish).

Terry, grinning inanely, ripped the poster from the newsagent’s notice board, oblivious to the shopkeeper’s withering look, declaring,‘are they taking the piss or wha’? An Cailin Ailinn na paroiste? If I remember my Buntus Cainte (Learning to Speak) right that’s straight out of Fr Ted. We have to check this out.’

And that’s how I found myself marching the streets of Lixnaw, Co Kerry with four strangers I’d met in a pub close to midnight one summer on an August evening, only two nights after the solar eclipse that scarcely a sinner, myself included, saw, on account of the dense sea mist that engulfed the county.

* * * * * *

The darkened smokiness of Quilter’s pub in Lixnaw was in stark contrast to the colourful mayhem going on all around it.

To the right of the pub and just behind its small car park, a ferris wheel the height of a four storey building spun its cargo of humans to the tinny rattle of Rod Stewart’s Do Ya Think I’m Sexy.

At the entrance to the temporary fairground a harried man in a candy striped booth dispensed tickets, loose change and candy floss at 50p a stick.

There were chairoplanes and a kiddies’ roundabout and a stall with a wheel of fortune that was tended by a woman the size of a baby elephant who was chanting ‘Hairy Mary’s back from Tipperary, round and round she goes, where she’ll stop, no-one knows…’

We ignored the fairground and headed straight for the bar. Quilter’s was the hub of all the festival activity as they owned the carpark and the field behind where every other event, bar the ‘tarrier race’, would be held. These included a wellington hurling contest, a tug of war and then the highlight of the evening, the donkey race.

* * * * *

But the most unholy sight was the stampede of dogs of all shapes and sizes, yowling and yelping frenziedly, as they thundered in our direction, in pursuit of the van.

* * * * * *

‘’How’re ye, boys, what can I get ye?’ a friendly voice from behind the bar enquired as he wiped the beer stains from the counter before us and swept two empty pint pots away in the fingers of his other hand.

‘Two pints of stout,’ Terry replied.

The barman squinted in the dim light of the bar. With a glass cloth over one shoulder and his head tilted to the side while he pulled the pints, his squinting eyes twinkled, a thin smile lingered on his mouth as he asked, ‘are ye here for the festival, boys? There’ll be some craic here tonight.’

‘We’re here for the tarrier racing, the donkey derby and the cailini ailinn…’ Terry joked loudly.

A group of men huddled in one corner of the bar turned their attention to us. Ruddy faced farming men, they were big boned and hardy. The tall one sitting nearest to me wore a baseball cap that declared him a fan of the Boston Whitesox. The grey flannel trousers e wore were torn and frayed by the ends. His worn, brown leather boots looked as though they had seen better days. The lining of his jacket burst from a hole at the elbow of his left arm. His hand, like a shovel, gripped his pint glass between his thumb and his forefinger.

‘Are ye from Dublin?’ he asked, adding, before we could reply, ‘there’ll be a book open soon if ye wanted to make a bet on the donkey race.’

‘Jaysus, give us a chance to wet our whistles first, men,’ Terry laughed easily. They all joined in.

‘We don’t mind ye backing the donkeys or, indeed, the dogs but we’d like you to stay away from the lovely women. They’re for our eyes only,’ another joked, triggering another burst of merriment. In fact, the cailin ailinn wouldn’t be chosen until the following night, we were told.

The ice was broken. More pints were ordered, stories told, great games won and reputations destroyed. As the evening advanced, our numbers grew and each newcomer, in his turn, made his way into our circle with a round of drinks and a sporting story or a joke.

Around eight o’clock the barman, who had been missing for a short while, came in and declared the tarrier race was starting and would pass right by the front door of the pub in less than two minutes. We all grabbed our pints and squeezed out the door.

Outside the light of the summer’s evening had given every surface a sparkle. Fifty yards down the street a dark green Hiace van was idling as a group of men huddled near its back door. Beyond them we could hear better than see another knot of men holding a motley pack of hounds on strings, ropes and leather leads.

‘Wait’ll ye see this, boys,’ one of our drinking companions encouraged, nodding down the road towards the dogs and the Hiace.

‘What’s going to happen?’ I asked but the action had already begun. The barman, our genial host – his name was Ignatius – had emerged on the other side of the street carrying a whistle and a gas hooter, like the kind they use at football games. He let off an earsplitting honk as the Hiace coughed into action, gathering speed as it approached the pub.

But the most unholy sight was the stampede of dogs of all shapes and sizes, yowling and yelping frenziedly, as they thundered in our direction in pursuit of the van.

Or what was hanging from the van, it transpired. Because as the Hiace drew level with the small wall of the pub we were all standing on, you could see a beat up joint of meat had been tied to the van’s rear fender. This was drag racing, Kerry style.

We all stared, bemused, at the receding van as it sped up the road with the town’s dogs baying and barking in hot pursuit. There was laughter and roars all round. But soon everyone was back in the bar, assuming the positions they’d stood or sat in before.

Although you’d be hard put to pin down a reason, the atmosphere had changed. Ignatius, a hard working gossoon who never seemed to stop, had raised a board behind the bar complete with grids and the names of all the donkey’s jockeys in preparation for the big event, the donkey race.

Betting was brisk and rich. Fivers, tenners and the occasional twenty made their way into the carefully attended biscuit tin. Names and stakes were jotted into the cash book. No dockets were issued.

Two others, a petite and coquettish grey mare and a lumpy roan by her side, gave in to their baser urges, discarding their pilots unceremoniously, in their unbridled passion.

Terry, a fervent punter, was already sussing out the form. Although there were 12 donkeys in the race and hundreds of people from the village and the outlying townlands of the parish would be there to cheer on the winner, it was a two donkey race, according to the pundits dispensing advice and wisdom out of the corner of their mouths while sitting at the bar, nursing pints and bottles of stout and the occasional glass of whiskey.

‘Murphy’s donkey will take the prize from Mick Lehane’s grasp and Jimmy will never let him hear the end of it,’ one old farmer in a grime encrusted serge blue pin stripe suit that must have been more than thirty years old if it was a day.

‘I’ve £20 on Lehane,’ a younger man said, ‘and he won’t let me down. His donkey has won two good races this year and he’s been training him this past month for the feshtival. There’s nothing known about Jimmy’s donkey although they say he’s been grazing him in a farm outside the parish.’

‘He’s a cute hoor is Jimmy. He’ll give nothing away ‘til he’s good and ready,’ someone else said.

The race track, in the field behind, was laid out like a crime scene. Wooden stakes and empty beer kegs littered the rectangular pitch strung together by a twisted roll of thick tape. There was no paddock but everyone caught a look at the field as they lined up beside Ignatius now posing as captain of the course, perched on a high chair he’d borrowed for the purpose from the bar within.

There’s little need to describe the race. Once around the field might have been their objective but at least four of the contestants never left the starting line regardless of the coaxing of their jockeys and the growing impatience of their supporters.

Two others, a petite and coquettish grey mare and a lumpy roan by her side, gave in to their baser urges, discarding their pilots unceremoniously, in their unbridled passion.

There were, as the wise old pundits in the bar had predicted, only two donkeys in the race although some held out for an upset when a snow white donkey ridden by what looked like a spider monkey but was a child of six or seven, took off at a brisk canter ahead of the rest.

His charge abated as swiftly as it had begun. When he reached the first bend in the field he carried on in a straight line through a gap in the outer fence, the howls of his jockey drowned by the baying roar of the crowd.

After that it was all over bar the shouting.

. Jimmy Murphy’s donkey raced nose to nose alongside Mick Lehane’s until the final straight. Holding the inside line on the curve, Murphy’s donkey inched ahead as they straightened out for the final burst for home.

Then Murphy’s donkey showed its class, streaking ahead, leaving Lehane’s two times champion a big time loser on the night.

Murphy’s ass had barely crossed the finish line past the waiting Ignatius, frenziedly waving a chequered flag from his lofty position on the high chair, when the shouting began in earnest.

A knot of angry Lehanes surrounded the winner and his owner and their supporters. The atmosphere changed from festival to fight night in a trice. Mothers herded their children to the fairground. Boys boxed each other about the ears and wrestled.

‘There was foul play here tonight,’ Mick Lehane was heard shouting, ‘that donkey should never have run in this race. He’s not even from the parish.’

All heads turned to Jimmy Murphy like spectators at a match and they waited for his return. But Murphy wanted to savour his victory and his reply was calculated to answer nothing and exacerbate his opponents’ anger and frustration.

‘’Twas a fair race,’ says he, ‘can’t you take your beating?’

Lehane was fit to be restrained as indicated by the way he spread his arms out to those around him as he feigned a lunge for Jimmy Murphy.

‘That donkey has ridden races in other parishes,’ someone argued, ‘he was grazing in a field near Listowel only two weeks ago.’

Murphy faced his accusers and taunted, ‘there’s no stud book in donkey racing.’

At this point Ignatius, the race marshal and course captain stepped in and the gathering crowd hushed to hear his say.

‘’Tis true competing donkeys in the annual Lixnaw parish derby must be from the parish,’ he announced, adding with a hint of a smirk, ‘but ‘tis also true there’s no stud book in donkey racing as Jimmy here points out. In that case this is not only a matter of honour but of birthright. We are all entitled – and a donkey is no exception – to a homeland for the parish graves are full of our forebears who have fought for that right.’

There was a murmur of assent and agreement among the spectators . Then a voice from the rear of the group piped up, ‘you’ll have to ask the parish priest. He’ll give ye ye’r answer.’

It was the crusty old sage in the corner, our man in the blue pinstripe suit. Savouring his moment at the centre of attention, he declared,

‘The donkey’s home is the home of its owner and if the owner’s home is within a Station district of the parish then it stands to reason – he said ‘raisen’ but even Terry and I knew what he meant – that that’s the home of the donkey.’

‘The Stations is when the priest takes the Holy Mass to the homes of his parishioners,’ Mr Woodbine explained, sloshing the dregs of his pint about in their glass, a look of forlorn yearning in his eye arched in Terry’s direction.

‘Give that man a pint,’ said Terry, asking ‘are youse boys ready for another?’

No sooner had he asked than three more drained pint glasses hit the counter which Ignatius, already a step ahead, had begun to replace with fresh ones.

Mr Woodbine cleared his throat and squinted happily at the settling head on his pint. He raised the pint to eye level and with one eye shut, examined the depth and quality of the pint’s creamy head. Then satisfied, he raised it to his lips and slowly submerged them into the edge of the glass.

It wasn’t until he had replaced it on the bar, his beer mat straightened and the stout moustache on his upper lip wiped clean with the back of his sleeve that he spoke.

‘Each parish is divided into Station Districts and twice a year each Station house in the district gets a visit from the priest. These are called out from the pulpit by the parish priest himself on the first Sunday of the month.’

Terry and I looked at him, hearing but not understanding. He went on with the tolerance of a saint.

‘To be named a station house is a great honour in the parish and no expense is spared to bring the house to sparkling order for the honour of receiving the Holy Host in your home,’ he continued.

‘’Tis only a chance for the well to do of the parish to show off,’ someone interjected. He was silenced by a grumble of voices while Mr Woodbine waited patiently for calm to resume.

‘’Tis true for you, in a way,’ he conceded graciously, ‘everyone is invited but only a few are chosen to host such an event. In the end it is an opportunity for the Grandees of the parish to sit down and eat grub with the parish priest in their own house. Their houses are painted and scrubbed from gable to gable, the best ware and linen is laid out and the dinner table groans with baked hams glazed with honey and cloves, roast chickens and steaming bowls of spuds, bursting with floury laughter, all served with tea, bread and sweet cakes on the best bone china.’

‘There’s only one thing for it,’ Jimmy Murphy declared, ‘let’s go to the parochial house now and ask the parish priest to arbitrate the dispute.’

* * * * * * * *

So here we were, this motley crew, hastily delegated from Quilters. We swung through the tall, cast iron gates of the parochial house. It was five minutes short of midnight.

Lehane and Murphy and the little man in the tired pinstripe suit doffed their caps and hats as Ignatius rattled the parochial house’s heavy door knocker. The crash of metal on metal in the midnight gloom could have raised the dead. For one ridiculous moment I felt like running away to hide.

There was a pause as long as a week before a light came on within. Then a distant sound of approaching feet down the hallway stairs.

‘Who’s that?’ the voice of the parish priest could be heard enquire.

‘Could we have a word with you, Father?’ Ignatius began, ‘there’s a dispute arising out of the donkey race…’

The door opened to reveal a distinguished if sleep tousled head in a collarless white shirt and pants donned in a darkened hurry, a button misplaced in his haste.

‘The donkey race? Are ye mad?’ he growled, surveying our faces in the gloom.

‘Murphy’s donkey took the race but the Lehanes believe the donkey is not a bona fide member of the parish,’ Ignatius explained breathlessly.

The parish priest glared at him in disbelief, mustered himself to speak, shook his head, snorted and went silent.

‘We said the only way to establish the donkey’s bona fides was to ask yourself if the Murphy’s house was within the station district,’ Pinstripe, unabashed, contributed.

The parish priest’s anger appeared to dissipate as though he’d been distracted by the territorial conundrum raised by Pinstripe.

‘There are three townlands in that Station district,’ the parish priest explained, ‘Glenoe, Leam and Oliversfield. The Murphys live in Oliversfield and I’ve seen three generations of their family through their devotions from cradle to grave but I’ve never seen their donkey at a Mass. Now turn around, men and get out of my sight. I’ve more things to be doing than arbitrating on the results of ye’r gambling exploits.’

And so the dispute was settled. Murphy’s ass had carried the day. Lehane would have to take it in good grace. Ignatius would have to pay up at two to one.

As we strolled back towards the pub to carry the news, Pinstripe by my side chuckled silently to himself. ‘Murphy’s donkey may be from the parish but Father Gaynor’s housekeeper slipped in to the bar to place a fiver on the winner only minutes before the start of the race.’

Postcard from a Pigeon

- Dermott Hayes's profile

- 4 followers