Dermott Hayes's Blog: Postcard from a Pigeon, page 79

April 26, 2016

sunburst with passion

From Nothing to Surprise

Jimmy Brown’s blowin’ town, he thought, as he slipped behind the wheel of his silver grey Honda Odyssey, the gift he gave himself for his 70th birthday. He loved the smell of new leather and fresh upholstery. He rubbed one hand along the dash as he slipped the key in the ignition.

The car had power adjustable seats with eight variations, the steering wheel had a tilt and telescope facility. Even the sliding doors were power operated and on top of that, it topped all the safety standards. There was a dock for his cell phone that would let him take calls, hands free and charge the battery, too, while he was driving.

Jimmy let himself slip and slide back as he ran through the driving seat adjustments. He did the same with the steering column until everything was just so. Next, he turned on the ignition, chose a cd from the selection of country favourites he’d just bought in the 7/11, Jim Reeve’s Greatest Hits, slipped it in the machine that lit up like the bridge of the Starship Enterprise, then he selected a button for random play, checked his mirror, signalled and pulled out into the quiet, Main St traffic.

‘Get ready to take us to warp speed, Mr Scott,’ he chuckled, as he drove down the short end of the street and the quickest route, out of town and into the country. Monday was a quiet day so Jimmy closed the office, for the day, sending Mrs Wicks, his bookkeeper home for an unexpected break. He felt a passing whimsy, he suppressed, about why she never made any remark about it. She knew him, he didn’t take days off, yet she never said a thing about it, just grabbed her bag and coat, waved and took off.

‘What the hell, like as if I cared?’ he said to himself and he pointed his gleaming new SUV, a Honda Odyssey, no less, southwards into the great blue and desert like yonder. Jim Reeves was singing, ‘From a Jack to a King, from loneliness to a wedding ring…’ He didn’t like any fuss, anyway. Mary Wicks worked with him, in that same office, for close on 30 years. He saw her family grow up. He even designed the extension on her tract house on the edge of town.

‘with no regrets, I stacked the cards last night and Lady Luck played her hand, just right…’

He was singing along but ol’ Jim Reeves wasn’t making magic for him, he thought. With his right hand, he rustled around in the bag he’d thrown on the passenger seat and found Marty Robbins’ Gunfighter Ballads. ‘Now, that’s more like it,’ he thought, ‘a good ol’ boy, done good.’ He hit the random selection button again and got

‘when I hear the raindrops coming down, it makes me sad and blue…’

Frustrated, he hit the random button again and this time ole Marty was singing, ‘Cool, clear, water…’ This was one he knew like he’d written it himself in an old notebook he kept as a journal. At least now, though he was alone, he felt free and, well, happy or so he told himself, ‘keep a’movin’ Dan, he’s a devil of a man…’

Now the desert highway stretched out before him and he knew he had choices with plenty of time to make them. He could go on to Las Vegas and spend the night there. Or he could take the interstate at Kingman and take the long ride into Los Angeles.

Marty was singing, ‘bury me out in the prairie, where the coyotes can cry o’er my grave…’ The words made him pause as he tried to make sense of the jumble of emotions he was feeling; lonely, because he was alone for the first time in 50 years, on his birthday and angry, because his wife, Barbara, his childhood sweetheart was gone, taken by cancer, before they could pack up her memories and say goodbye.

‘She was young and she was pretty, she was warm and tender, too…’ ‘Christ,’ he shouted, aloud, reaching over to turn off the music. ‘Even Marty Robbins’s against me,’ he thought. He hated himself for feeling so sorry for himself. When he got up that morning, he was thinking of stopping by the nursery to pick up some saguaro cactus blossoms and paying a visit to her graveside. She loved their sweet smell and always laid them out in a bowl floating on a thimble of water for his birthday. She said they reminded her of him, big, rough and spiky but soft and fragrant, too. She told him it was no coincidence he was born in the same month they blossomed.

beautifulflowerspict.blogpot.com

He couldn’t go to her grave, couldn’t face her, feeling angry and lonely. They’d both grown up together in Scottsdale, sweethearts through high school and stayed devoted to each other even when he studied architecture in ASU, Tempe. But that wasn’t far away so they kept in touch. His father was an architect, studied and worked with Frank Lloyd Wright and little Jimmy Brown was going to build big things, too.

But that was 1965 and he joined the Marines, volunteered, like a fool, he thought in a moment of patriotic lunacy. They married, before his first tour of duty, up country Vietnam. It was a hell that kept on giving and the only ray of hope and light for him was the thought of Barbara, waiting for him, at home. She even sent him cactus blossoms while he patrolled in the sticky heat of the fetid jungle. When he got home, safe and uninjured, externally, at least, he finished his degree, got a job and bought a house, but he knew and she knew, too, but she understood, he was never the same man.

He’d been on the road for almost three hours now, he figured but, lost in his thoughts, he didn’t know where he was. His new Honda had satnav, as standard but he was wary of it and hadn’t turned it on. He didn’t know where he was going so how could it tell him where to go?

There was one road and plenty of dirt trails but this was the Mohave Sonoran desert, the hottest, bleakest expanse of searing desert in all of North America. He’d stocked up with drinking water, had a full tank of gas and in the a/c comfort of his Odyssey, he felt at ease. He didn’t want to go to Las Vegas, though, and the thought of the long drive through even more desert, to Los Angeles, bore no appeal. No, he thought, there’s nothing to do out here, time to head home.

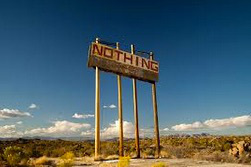

It was then he saw the road sign, old and beat up, it said, NOTHING and he started laughing and laughing, until the salty tears ran down his face, unchecked. He’d reached the town of Nothing, an uninhabited ghost town, smack in the middle of the desert that was now used for photo opportunities by tourists and an occasional film crew. Still laughing, he swung the Odyssey around, his journey was over. He knew Barbara would’ve laughed as well.

He’d reached the town of Nothing, an uninhabited ghost town, smack in the middle of the desert that was now used for photo opportunities by tourists and an occasional film crew. Still laughing, he swung the Odyssey around, his journey was over. He knew Barbara would’ve laughed as well.

The drive home seemed shorter than his outward venture. But then, he thought, that was more of a journey inward. He put on another cd, Hank Williams at the Grande Ole’ Opry, put it in the machine and hit the button and waited.

‘Hey, hey, good lookin’, what you got cookin’?

Jimmy smiled, slapped his wheel, threw his head back and sang along, ‘how’s about cookin’ something up with me? Say, say, sweet baby, don’t you think, maybe, we could find us a brand new recipe…’

For the rest of the trip he sang along with Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, George Jones and Tammy Wynette and pretty soon he was home in Surprise, Arizona.

April 25, 2016

Foxglove 2

Hugh’s weekly photo challenge: week 22 Group

Autumn Leaves

Foxglove

Be Prepared

A gentle drizzle of summer rain fell like a blanket of sodden gauze on the meadow. Morning, a reluctant schoolboy, crept across the field. Songbirds and the hum of river insects roused the day and the two rival camps from their slumber.

I was stuck between the two, in a small, frame tent, senior patrol leader of our troop, forcing my eyes open, listening to the morning symphony, feeling my stomach turn, my heart sink .

A member of Beaver patrol speared himself with a can opener the day before. He required first aid, transport and two stitches. I had a bad feeling then even as the ambulance driver ribbed about being prepared for anything. Badger patrol members hacked into a living tree trunk to build a ford for the stream.

Both patrols were competing for their weekend camp competence badges. Personal pride was at stake for the two patrol leaders, newly promoted and their new patrols formed to accommodate the troop’s burgeoning numbers.

Beaver leader Tom McCarthy was as big as he was loud. A strapping lad of thirteen years, he had been a scout two years and made up in strength and enthusiasm what he lacked in skill and patience. He led by fear and respect- no-one would call him a bully to his face – but he got things done.

Ken McCusker, of the Badgers, was a little older than McCarthy, quiet, ambitious and arrogant and a skilful scout who led by example. McCusker was competitive and impatient.

The camp was planned four weeks in advance. Both patrols had a list of tasks to perform. These included laying out and pitching a serviceable field camp with wet and dry latrines, field kitchens, fuel and supply storage and a campfire capable of providing three hot meals a day for the patrol.

Tents were to be pitched according to specifications; dry and level pitch, secure guy lines and facing downwind. Extra points would be added for organisation, initiative and teamwork.

Patrol leaders were marked on leadership skills and their ability to motivate the others and maintain a high level of morale with singsongs, entertainment and games.

I considered myself an old hand at camping. Though younger than the other two by almost a year, I became the youngest patrol leader at eleven and then the first senior patrol leader in the troop.

Along the way I collected a colourful array of proficiency badges that included advanced knotting, first aid and backwoodsmanship. The latter was an arduous weekend camp alone where I built a secure, dry bivouac with available materials and cooked a three course meal for two without the use of pots. Bear Grylls, move over.

Basic foodstuffs were supplied along with a knife, a fork and a box of matches. I made a salad of wild rocket and sorrel to start and followed that with a potato baked in hot embers and stuffed with bacon and egg. A tin of baked beans was heated on a flat rock in the campfire.

Dessert was a dough bread made of egg, flour and water and cooked on a spit like a kebab then filled with wild blackberries. An ambitious attempt to boil tea over an open flame in a brown paper bag met with mixed results – the bag sprung a leak when the water was lukewarm but I quickly transferred the contents to the empty bean tin.

Outdoors was heaven for me. Outdoors was an infinite playground for the imagination.

My wake time reveries were disturbed by a commotion from the Badger camp, 150 metres south east or to the left of my encampment, a natural hollow in the lea of the meadow’s prow. Beaver patrol was camped straight ahead, south west of my own position.

“I’m not ready for this,” I groaned, crawling out of my sleeping bag, kicking stockinged feet into my boots and grabbing a shirt and jacket with one hand as the other untied the tent flaps. The yelps and screams that rent the morning calm were replaced by running feet and shouting, angry voices. The camp, in the distance, was engulfed in a thick fug of damp campfire smoke. I walked down the hill to inspect the commotion.

As the morning breeze thinned the fog, three figures stood out at the centre of the action, beside what remained of the Badger patrol’s camp centrepiece, a canopied kitchen and service area with a prep counter and a charcoal grill and spit. It was a Ken McCusker special; effective, economical, social, industrious and ingenious.

A black faced McCusker was berating his two subordinates, assistant patrol leader, Jimmy Woo, who was in charge of the previous night’s camp watch and Johnny Norris, camp cook. Globules of mucous and saliva were spitting from McCusker’s mouth and showering the heads of the other two.

His bluster halted with the clatter and clang of two tin cans I banged.

All three turned to look at me. “Look at what that bastard McCarthy and his crew have done to my camp…”, McCusker began, as I surveyed the damage, “I’ll fuckin’ ki…”.

“You’ll do nothing, Was anyone injured?”

“No, but we were luc…”

“What happened?” I asked this last question of Norris, ignoring McCusker’s rant.

Norris was quiet and slow but deliberate. He looked cowed and the shouting wasn’t helping.

“I lit the fire and built it up and then I put the big pot of water on to heat for the breakfast,” he said, choking back a tear, “then the whole thing got drenched in water and there was steam and sparks and boiling water.”

“They rigged up a canopy of water in a manure bag and hung it under the roof of the awning we built over the main stove,” McCusker took it up, “and when the fire heated up the air under the canopy got hotter, the plastic melted and the water put the fire out.”

“How did they get in without anyone hearing them?” I asked Jimmy Woo, a Taiwanese Chinese who spoke very little English but was invaluable for rigging McCusker’s mad schemes. Jimmy explained how he laid out a network of tripwires around the entire perimeter of their camp, backed by a corner of the stream .

“So they came across the stream,” I concluded. “If it was the Badgers,” I remarked smirking, pointing behind them to the makeshift camp flagpole, “at least they have a sense of humour.”

A roll of toilet paper replaced the Badger patrol banner leaving a clear message to McCusker his camp was a shithole and the Beavers had just flushed all over them.

A strange look came over McCusker. He bent his head and began to shake and sob. Then he stood bolt upright. He spat out a shuddering scream of outrage before sprinting off in the direction of the Beaver camp at the far side of the field.

Pearse and Jimmy Woo gave chase while Norris went back to directing the clean up. The entire camp, Woo told him, would have to be moved. McCusker, a handy sprinter on the school team, had a good start on us. I felt my gorge rise in a wave of nausea. I knew what was coming. I never wanted to be prepared for this.

As we crested the hill we could see McCusker launch himself into the heart of the Beaver camp. I saw McCusker struggle with McCarthy before the bigger boy fell onto his knees and pitched forward into the camp’s kindling pile. I got to McCusker just as two members of the Beaver patrol grappled McCusker to the ground.

Members of both patrols gathered in the Beaver camp. The younger boys were crying. Some of the older boys were arguing. One of their leaders lay wounded. The other had lost his reason.

I prised the weapon from McCusker’s hand. The stricken McCarthy, stabbed with a camp fork ploughed and raked across his back, coughed, convulsed and spluttered. Then he stopped. He was dead.

April 24, 2016

100 years, April 24 1916 – 2016

This is my tribute, made with the help of a bunch of friends, to the men, women and children, who died in the Easter Rising that began April 24, 1916, exactly 100 years ago, today, in Dublin.

Some moments echo forever

Sinful Saviour

A shapely thigh,

a wisp of lace.

puts a glint in my eye

and a wistful

spark of youth,

in my face

Sinful Sunday #36

More Sinful Sunday here.

April 23, 2016

The Curious Incident

WQWWC

“Is there any point to which you would wish to draw my attention?’

‘To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.’

‘The dog did nothing in the night-time.’

‘That was the curious incident,’ remarked Sherlock Holmes.”

― Arthur Conan Doyle, Silver Blaze

Waking up somewhere you don’t recognise is not good. Waking up beside a complete stranger doesn’t augur well, either. And if they’re dead, that’s not a mystery, it’s a disaster.

My mysteries usually occur in the dark end of a dimly lit alley, the air redolent of scuzzy discarded condoms, beer puke, urine and faeces, the graffitied walls dripping with a primeval slime.

This was a high class hotel suite. The sheets made the crinkly noise of Egyptian cotton and the complimentary pillow chocolate that was stuck to my face, was at least 70% high grade cocoa.

The corpse beside me was naked. Checking her pulse was out of the question. Her throat was slit from ear to ear and she was the colour of an old dish cloth. It was a big bed so little of the blood bath had oozed as far as me. Of course, I thought, it helped that she was surrounded by bloody teddy bears, maybe two dozen of them.

They weren’t just ‘bloody’, like splattered, no, they were oozing blood. It was like a teddy bear massacre. And these were just my waking moments, that fuzzy twilight where you can see the light, in the distance, but all your other senses are still playing catch up. Because just about then, I began to smell the blood and forgot about the teddy bears. It smelt like a slaughterhouse.

Then the fog lifted and I leaped out of that bed, stark naked, ready to run, as far and as fast as my feet would carry me. And that wasn’t too far because my clothes were there, by the side of the bed, folded neatly over my Zimmer frame walker. Then it occurred to me I hadn’t moved that fast in 20 years or more. And I’m naked, Christ, I didn’t even like looking at my own body, anymore; scarred, pitted and crooked as it was. Suddenly, I needed to pee. I looked around for my socks that were stuffed, neatly, into my Drew Jimmy’s orthopedic shoes. I grabbed my boxers, too and sat on the Ottoman at the end of the bed to put them on.

That done, I hobbled to the bathroom behind the bed. In there, I lifted the seat off the toilet and waited. Jesus, I thought, now with the stage fright? The bathroom looked untouched. The toilet roll had that triangular fold like it was a dinner napkin, for God’s sake. What the fuck was I doing here? Where the fuck am I? and who, the fuck, is the stiff in the bed next door? Still nothing, the sluice is open but there’s no flow. Fuck it, I have to get out of here.

I gave up trying to pee and paused, to unwrap a small tablet of soap but when I turned on the tap, it wasn’t the only faucet to let fly. Christ, I cursed, as a trickle of pee ran down my leg, soaking my boxers, before I could get it out again to point it at the pan. Of course, I’d put the lid back, so now there was pee on my feet and the floor and by the time I got the lid up, again, it stopped.

That was it. I went back inside and got dressed in a hurry, well, as quickly as my rickety 78 year old frame could manage. Composed and leaning on my zimmer, my bed companion, deceased, I paused, long enough to look her over. She was a real beauty, maybe 55, 60, or thereabouts. Blonde, if bottle enhanced, and nice jugs, too, though just a little too pert, given wear and tear. In fact, they defied gravity, sliding neither to the left or right, nor flattening like the worn out dugs of the last woman I bedded and that was ten years ago.

Before I left, I took a hand towel from the bathroom and mopped the pee from the floor. Then I took another and wiped down any obvious surfaces like the bathroom door handle and around the bed, on my side. Then I threw both towels in the bath and soaked them, quickly, by turning on the bath faucet.

Satisfied, I left, hobbling down a long corridor where I found an elevator. That tune, An Englishman in New York, was playing and I pressed the button for the lobby. There was no-one else in the elevator so I hummed along with Sting until the door opened and I shuffled out in to the busy foyer. I gazed around to get my bearings.

“Dad, Dad, there you are…where, in God’s name have you been? Every person in this hotel has been looking for you. The cops have been trying to find you. Jesus, what are we going to do with you? Don’t ever wander off like that, again. We’ve been going crazy, we thought you were dead or mugged or something.”

I looked sheepish and contrite, but I said nothing.

Postcard from a Pigeon

- Dermott Hayes's profile

- 4 followers

Abstract

Abstract