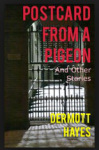

Dermott Hayes's Blog: Postcard from a Pigeon, page 76

May 8, 2016

Postcard from a Pigeon

Postcard from a pigeon was the first story I wrote for the 2012 collection of short stories that is Postcard from a Pigeon and other stories. So, without further ado, oh, I do need to say this is by way of introduction, because this is what I do, write short stories (among other things, like photographs and poems)and here’s the one that inspired the title of a book and this WordPress Blog site, Postcard from a Pigeon, the musings of Dermott Hayes, a writer(comments, welcome and requested)

As the story went, Paddy was a local pigeon. Anyone could tell that from his general demeanour. He was scrawny and mottled. He had a shifty look about him and never seemed at ease when he was still. But he could strut with the best of them and was a regular on the steps of the pub when the chef tossed scraps in the morning.

It was down the same lane beside the pub where Tito first made his acquaintance. Poor Paddy took a tumble or was in a rumble with a scavenging crow. When times were lean the survival war continued, bird against bird, claw to claw, beak to beak, an eye for an eye.

Paddy’s wing was broken and he lay on the ground amid the fallen autumn leaves, discarded Tayto bags and used condoms. Flightless, he was a sitting target for every predator, winged or not. He would scrabble and peck but his days, if that’s how they counted time, were numbered.

Tito kneeled and spoke to him. He made pigeon sounds. He cooed and billed and murmured softly. Paddy squinted at him ferociously, scrabbling frantically if Tito moved. He kept his beak wide open but never made a sound.

Half the pub turned out for Paddy’s departure. It was like an American wake and the denizens of Bruxelles were seeing off a member of the family. Pigeon stories abounded.

Paddy blinked when he first came into the sunlight. Tito lifted him gently to his face, speaking softly to the bird. When he unwrapped the cloth and let him go there was a flurry of feathers as Paddy struggled to keep himself aloft, testing his wings for faults and strength. Then he flew away.

He flew to the top of the nearest building, a municipal edifice opposite the pub. There, he paused, perching on the paint peeling gutter, staring at Tito below. Then he flapped his wings and flew away.

Tito slumped. Everyone in the bar watched the drama unfold through the side window. When Tito came back to the bar, everyone was in their seats. Not a word was said.

Tito was like any other refugee or asylum seeker whose numbers had swollen in this city in the last years of the last century. And he was unlike them too.

He could speak several languages with ease which was why the rumour started about his command of ‘pigeon’.

He was Albanian though he spoke Italian fluently and carried an Italian passport of dubious provenance. He could converse with ease and facility in English, French and German and his Spanish went much further than ‘dos cervesas, por favor.’

If there was a language problem to be solved, Tito was your man and his services were engaged on a regular basis, to negotiate between the growing population of Central European workers from Croatia, Bosnia, Yugoslavia, Albania and Romania and their Irish employers.

Occasionally, as he sat in the bar on a Thursday afternoon waiting with everyone else for their pay packets, Tito’s humour would change from the breezy sparkle that saw him through years of hard knocks and strife, to a morose and brooding sulk. He would drink more than his customary pint of Guinness and snarl and snipe at his co-workers, foreign and Irish.

Sometimes he shunned their company and in a show of defiant bravado, he’d lavish charm on the nearest pretty female customer. Other times he sat quiet and brooded, joining the afternoon pub talk only with monosyllabic and barbed asides.

Once or twice, if the numbers at the bar were less, he would open up and allow a brief and all too oblique glimpse at his past. There was an overbearing father, a protective but timid mother and brothers whose high and consistent academic achievements paved the way for their younger sibling’s wandering.

His travels, he confided once in a rare unguarded moment, had brought him to a succession of European capitals, menial service industry McJobs and in and out of love and trouble in equal doses. He honed his wits in a hostile world with a sharp wit and natural intelligence. An easy facility with languages helped his passage.

There was talk of a Croatian girlfriend who fled with her family to Dublin from a holding camp outside London. Tito, some people who claimed to know him said, was by then working and living in Islington. He packed in his job, they claimed, to follow her.

Some people thought he was a deserter and perhaps even Bosnian. There was even a whisper of his involvement with smugglers and the tough and ruthless Albanian underground. There were as many rumours as Tito had tall tales.

His friends, apart from those he worked with, rarely visited him in the bar. When they did they were a rum lot, possessed of a greater self assurance than their compatriots.

Loving the mischief he could cause, Tito played up to the legend and fuelled the rumours. It was only on very rare occasions people got a glimmer of light through the fog.

Talk in the bar had it that Tito’s girlfriend was in the advanced stage of a pregnancy. There was speculation that this was why she and her family, devout Christians of the Orthodox Church persuasion, had fled London. Tito, an avowed atheist by his own protestations, was from a Muslim family.

The girl, housed by the Social Welfare in a budget hostel in the Liberties, refused to see Tito. This much, at least, was known for sure. Tito said as much himself one day when he turned up late to pick up his wages. He had just come from a public confrontation with her at the hostel where she lived.

This was confirmed by Viktor, a Bosnian who lived in the same building as Tito’s ex-girlfriend, but his version was far more graphic than Tito’s ‘public confrontation.’

“He went mad,” Viktor, a kitchen porter, recounted later to everyone on ‘cowboys corner’, the part of the bar unofficially reserved for regulars, ” he shouted and banged on the doors. He wouldn’t go away when they asked him. Then they said they would get the police but he stayed and shouted and kicked the door.”

Everyone in the bar that evening, Irish and foreign, listened intently. “He is bloody mad, bloody foreigner,” Sergio, the florid Sicilian owner of the Pizza parlour announced with great indignation and with no hint of irony. His extreme views, like his pizzas, were well known, if not as highly regarded.

Jimmy stood up for Tito, whom he considered a friend. “That’s not fair, now, you don’t know the whole story,” he said. Tito and Jimmy had a strong bond. Jimmy had taken Tito under his wing and Tito, in return, adopted Jimmy, teaching him Slavic slang phrases he could use to trade curses with the bejewelled Romany beggars or berate his small army of casual lounge labour.

Molly felt strongly for the boy too, a mother of four from the Liberties with a flower stall on the corner. Her sons and daughters, two strapping pairs of each and their father, Bert, a man aged before his time, gawped in awe of her. “The young fella’s missing his family and he wants to be there when his child is born. It’s understandin’ he needs, not the back of her hand,” she tutted.

And on top of all the travails already heaped on his head, his pigeon was gone. Tito nursed the bird back to health on a bed of old glass cloths in a shoebox hidden in the cellar, feeding it every day with meal mushed with milk and water squeezed through an old sock.

For two days a palpable gloom descended on the pub. Regulars found excuses to go elsewhere and the crowd at lunch was smaller than usual. On the second day only Jimmy and Sergio stood at cowboys’ corner.

“Whattahella is the matter with everyone?” Sergio asked no-one in particular, “issa likea funeral in here.” Jimmy stared into his Guinness, his fifth of the day. It was just five pm.

“It’s Tito,” Jimmy barked hoarsely as he lit another Sweet Afton, “he’s depressed about de burd.”

“He’s berd?” Sergio scoffed aloud, “they’re likea rabbits, justa leeving and breeding. He’s a better off withouta her from what I hear and he’ll soon find another to takea her place.”

“No, Jaysus, I meant his burd, Paddy…” interrupted Jimmy.

“He’s a queer as well? That’s all we need,” continued Sergio.

“Paddy the pigeon, ye fuckin’ eedgit, the burd with the broken wing he saved,” corrected Jimmy.

“Oh?” said Sergio, having missed the bird saga while on a visit to his own homeland.

Ignorance never stopped Sergio from expressing a forthright opinion on everything from sport to abortion but now there was a bird loving Albanian to consider.

Jimmy filled him in as best he could, relating the story of the hapless pigeon rescued, harboured and nursed to health by the volatile Tito. Sergio had returned from his holiday on the day Tito had his confrontation and he scoffed derisively when told of the pervading depression that followed the bird’s departure.

But it was clear, even to him, the pub and its denizens had assumed a pallor of unspoken grief and loss. Something needed to be done.

This was where I came into the story. Being an occasional visitor to this city hostelry as much for the irreverent ribaldry of its denizens as its excellent ‘pub grub’, I was a familiar, if irregular, presence.

In this cosmopolitan pub populated by human refugees, I was just another face with a pint. Everyone knew what I did for a living and no-one cared or bothered.

That evening as I took up my customary perch at the bar on cowboys’ corner, Jimmy began his approach. “Tito’s good buddy has gone, he’s flown the coop,” he began. Somewhat cryptically, I thought, though I knew the vague bones of the Tito and the pigeon story.

“He has more than the bird to worry about,” I volunteered, being one of the people with whom Tito occasionally engaged in conversation. Sergio, standing on Jimmy’s other side, looked up from his Racing Post.

Jimmy continued, “We need to do something and you’re the man for the job,” he growled in his best 40 a day worn voice, “we want you to write him a letter.”

“What…?”

“From Paddy…the pigeon,” he continued, ignoring my question, “he’d feel better if he knew the pigeon was safe and happy…”

“What…?”

“He might snap out of this depression if he got a letter from the pigeon,” he continued, “and we thought (his hand swept the company, two waiters, three kitchen porters, a university lecturer, a newspaper vendor, two policemen and a Sicilian restaurateur) you’re the very man for the job.”

“You want me to write him a letter from a pigeon?,” I spluttered, “Have you lost your marbles? Are you taking the piss?”

“No, no…if he got a letter from Paddy it might cheer him up. He has enough troubles but he’s been very down since the bird left.” Sergio’s confusion deepened. The company watched with interest and anticipation.

I thought about it. “Let me think about it,” I said and returned to my evening paper and freshly poured pint. Sergio asked to see the racing pages. There was an evening meeting in Clonmel and he fancied a leisurely beer fuelled flutter. There was a murmur of agreement and the talk turned to horses.

I pondered the bird conundrum.

Paddy the pigeon was gone, of that there was no doubt. His departure left behind a downcast Albanian and a depressed pub. Sergio left to make the bookies before the 6.30 race.

An idea occurred to me. Although the situation was patently absurd so, without saying as much, was anything that was said or happened in the pub. That was its charm and they were all willing contributors.

So here’s what I did. I thought of the Pigeon House, a city port landmark, that like many features of the city, were ascribed an identity of their own out of familiarity than with any relationship to their origin. So a statue of ‘Molly Malone’ became ‘the tart with the cart’ and another of two ladies resting on a bench with their shopping, ‘the hags with the bags.’ Buses and city maps referred to the south port location as ‘the Pigeon House’ when it was, in fact, named after John Pidgeon, who cashed in, cannily, on his role caretaker by setting up a cafe, selling refreshments to boat passengers arriving from England and Europe.

First I thought I’d get a postcard of the Dublin port landmark and then dismissed the idea as patronising and obvious. A postcard of Bruxelles would do. It would save me a walk in the rain too.

“Dear Tito,” I wrote, “How’s it going? I’m back with me mates down the Pigeon House and I have you to thank for it. The lads here are great crack and the wing has come on so much, the pain has gone. I’ll never forget your kindness to me nor the taste of that bleedin’ sock. Take care of yourself, I have to fly. All my love, Paddy the Pigeon.”

Although I was unsure if the facetiousness of the final sentence might shatter the carefully constructed veneer of absurdity, Jimmy was very pleased with my effort and told me, stashing it carefully in the pocket of his jacket, he would pass it on to Tito when he saw him.

The following day Tito was like a new man. He strutted and preened about the pub, joking and laughing in a Babel of languages. To everyone who would listen he showed the postcard, brandishing it with pride and a hint of whimsy.

As the evening progressed and as these things go when drink and sentiment are mixed, there were tears in their beer and a plaintive note in the songs.

Occasionally, brandishing the pigeon postcard, Tito read it in bleary silence and sniggered as though, locked within its banal sentiment, he found a secret only he could see.

Curiously, that was the last we ever saw of Tito in Bruxelles. He disappeared without trace, allowing full range for speculation and fantastical rumour. He was deported, some said. Others said he followed the girl back to London.

After that, life got back to its daily routine. Tito and the pigeon became memories until one day, almost a month since his departure,Viktor, Sergio’s kitchen porter, approached him with a curious tale. Tito was dead, he said, shot down, in mysterious circumstances, in a Sarajevan back street.

The location added further to the mystery that was Tito, a nameless Albanian nomad shot dead in a Bosnian alley.

‘Jaysus, he was some boyo,’ Jimmy observed. ‘There was something very dodgy about ‘im,’ said another. ‘Fuck heem,’ Sergio barked, ‘he was no fuckin’ good. We’re better off without heem.’

Listening, I doubted it was Tito. ‘What makes you think it was Tito if the dead man had no name?’ I asked.

Viktor, relishing his moment of drama, produced a carefully folded and frayed newspaper cutting from his wallet and laid it on the counter in front of us.

The story, he explained, speculated the death was connected to a black market smuggling operation.

He faced a wall of blank, questioning stares.

‘’Eets in the hedline,’ explained Viktor holding the clipping aloft with a dramatic flourish, and translating, ‘PIGEON POSTCARD MURDER CLUE.’

May 7, 2016

The Funeral

There’d been greyer, winter days in London but not in my experience. The clouds crowding the morning sky were like a bundle of overstuffed pillows, ready to burst. I smelled snow. The air was crisp; the daylight, brittle. My breath puffed like cotton candy in my face as I stepped from the taxi on Euston Road.

There’d been greyer, winter days in London but not in my experience. The clouds crowding the morning sky were like a bundle of overstuffed pillows, ready to burst. I smelled snow. The air was crisp; the daylight, brittle. My breath puffed like cotton candy in my face as I stepped from the taxi on Euston Road.

The old Victorian station brought back memories of student days and freezing, drunken sea crossings on the B&I from Dun Laoghaire to Holyhead; the dozy train ride to London. Camden never changes, I thought; the people might but never the place. Whole generations of Irish people trudged through this place on the emigrants’ trail.

I used to imagine the ghosts of Sherlock Holmes, Charles Dickens and all the characters who filled their worlds, walking these streets. My father used to read me Dickens’ stories. There was always a character seeking his true nature, a fish out of water.

I checked the big digital clock, 8.05am, I was early. The Holyhead train would arrive at 8.33, or thereabouts. It was British Rail. He hates flying. He only flew once before. 1968 it was, to do a training course in London. He never talked about it much apart from those half joking references to all the black people he saw. ‘Jaysus, they’d ate you,’ he used to say. I knew he was joking; I wanted him to be joking. I didn’t meet my first black person in the flesh until I was 13 and he was the only one in a school of more than 900 students.

I checked the clock again. Time for a coffee and maybe a muffin, buy a newspaper.

Euston was in full early morning rush hour mode; crackling, incomprehensible tannoy announcements, incoming commuters avoiding eye contact, striding purposefully; bewildered tourists dragging luggage, squinting at noticeboards, maps and timetables; station porters, some of them dreadlocked, others turbanned, moving at the pace they’d maintain for their day as though the frenetic pace of those around them was happening in another dimension.

I ordered a coffee from a stand up stall on the sidelines. The young, lip and eye pierced ‘barista’ looked confused.

‘Just a black coffee, please, regular milk on the side, thank you.’ Again with the blank look.

‘An Americano, then.’ At last, a light, there is someone home.

‘I’ll have one of those blueberry muffins too, please?’

Studs ignored me as she went about clattering coffee dregs from the chrome plated Gaggia before refilling it for my order, twisting the handle into place and pressing the steam release. The big machine chugged and hissed and then began to trickle coffee. She plonked a plate in front of me with a plastic spoon in cellophane before opening another glass case to lift the preferred blueberry muffin with her plastic thong. ‘£4.50,’ she said as she reached for the mug of steaming coffee with her free hand.

‘Milk?,’ I asked, handing over a fiver. She gestured with her chin and a sneer to a point beyond my left shoulder. I looked around and found a half opened cardboard box of u.h.t. Milk portions.

S.O.P., I thought, standard operating procedure. Like the station porters, her day has just begun. She’ll move at her own pace. At least the hot coffee was good, strong and aromatic in contrast to the muffin which tasted like a soggy paper napkin. I sipped from the steaming hot mug as I gripped it with two hands to warm my fingers. I checked the clock again, ten minutes.

‘Why could he not have flown over?’ I thought. Rhetorically, because I knew the answer. Boats and trains he knew and understood. Timetables were like a playful mathematical puzzle for him; itineraries, another campaign strategy. He’d have it all written down like a blueprint for the inner workings of a precision Swiss timepiece. I’ll bet he’s been standing in the gangway at the train’s exit door since it hit London’s outer suburbs.

I did my own research while I waited. I walked over to the nearest available ticket window and asked the sullen clerk how I’d get to New Malden. I knew it was in Surrey, south of the Thames and in the outer eastern suburbs of the city. Once he knew I hadn’t a complaint and wasn’t looking for a refund, my sullen friend went into friendly overdrive.

‘Take Victoria line to Vauxhall, mon, then change to the south west train line to Shepperton. That should get you there.’

‘Oh, thank you.’

My experience of London travel told me when there’s one way, there’s at least another.

’Suppose I took the Northern, south to Waterloo?’

‘You say ‘ sweet potato’ ,mon, I say ‘yam’,’

We both laughed and I bought the tickets he recommended.

I checked the time again and noted the train had arrived and was disembarking. I dropped the remains of the soiled napkin muffin in the nearest bin and made my way to the platform gate for the Holyhead train. As I guessed, he was out of the traps, ahead of the pack and already proferring his ticket to the disinterested ticket inspector at the gate .

‘Dad,’ I said, to catch his attention, ‘Dad.’ It worked. He stopped looking at the disinterested rail man in his dowdy black uniform and turned his attention in my direction. I could see him think and focus, then his eyes widened and he smiled, put his ticket back in his wallet, picked up his bag and shuffled towards me, oblivious to the growing glut of passengers in his wake.

He looked pale and drawn; shrunken, even. ‘How was your trip?’ I asked.

‘Too long,’ he said.

‘Did you get any sleep?’

‘Not a bit.’

He was already studying a notebook he produced from the pocket of his overcoat. I knew it was his itinerary. He checked his watch and then looked around for the station clock.

‘Have you eaten? There’s a nice little place across the road…’

‘Where do we get the underground? Is it in this station?’

‘There’s plenty of time. We can get some breakfast first…’

‘Your mother packed some sandwiches for me. I got a cup of tea on the train. The removal’s at 11. We’ll have to go now.’

‘I just thought…’

‘I want to get going.’ And with that he picked up his bag and walked away.

Our ‘discussion’ was at an end. I followed him, a 30 year old man feeling 13. We were here to bury his sister, my aunt. He hadn’t seen her in 40 years. I never met her. She and his other sister left Ireland to seek work in post war London. Just get through the fucking day.

‘I’m going to phone Uncle Sean to let him know we’ll be there soon.’ He said nothing but just stood and waited.

Outside, the blizzard had already begun, snow blanketed the streets. Ahead of me, my father put on his little black beret and buttoned his overcoat to the neck. He turned and looked at me. I pointed ahead to the entrance to Euston Underground and led him gently by the elbow, both of us crouched and squinting through the white curtain blowing in our face. We’ll get the Victoria line to Waterloo and change there for the Shepperton train to New Malden. I have the tickets already. As we went through the tube station entrance I thought I saw him smile.

‘I booked you a room in the same hotel as me, tonight,’ I told him when we settled into a seat on the Tube.

‘There’s no need. I’m going home tonight.’

‘You’re joking. Look at the weather. The boat won’t sail.’

‘Oh it will, as far as I know. It was like this all the way over on the boat, snowing, but they told me the boat would sail tonight.’

‘But you must be exhausted. You didn’t sleep last night,’ I argued but I knew it was useless. His mind was made up, his plan was made. He stared out the window into the void of an underground tunnel.

‘I saw a fox standing alone in a field on the train journey down. I noticed there was a copse of woods in many of the fields.’

Vauxhall approached. I gathered his bag and hung the strap from my arm. It was very light.

‘You didn’t bring much,’ I said.

‘No,’ he agreed. There wasn’t much else to say. We disembarked and walked to the overground train station on the other side of a wide street junction outside. The snow still fell but it had abated. Traffic and pedestrians turned it to mucky sludge, underfoot. We barely spoke on the short train journey to New Malden.

Two people, my late aunt’s husband and widower and his daughter, my cousin, met us at the station. Uncle Sean was a small man with big hands, gnarled and calloused with labour and arthritis, I thought. Hatless, his hair was white and thin on his head. His lined face carried a life of experience and hardship but the crow’s feet at the corner of his eyes and the upturned wrinkles on the corners of his mouth hinted at good humour and laughter. His eyes were as green as the sea in Galway bay but without the light that reflected off it in the moonlight.

His daughter, my cousin Aine, was an entirely different kettle of fish. Big bosomed and rosy cheeked, her smile glowed in this snow blown morning on a train platform in east London. ‘Greetings,’ she said, ‘ye must be frozen in this weather. I’m Aine, Sean’s daughter.’

Then she enveloped my father in her billowing, dark blue overcoat and the cushions of her mighty bosom, kissing him behind his right ear. When she released him he appeared to reel back on his heels, his eyes opened and shut and opened again. He put out his hand to my uncle Sean, grasping his and whispering, ‘Sean, I’m sorry for your loss.’ Uncle Sean looked at him but his gaze was focussed about two feet beyond him. Then Aine turned to me and I drew my breath, involuntarily, as I felt myself being pulled into the same welcoming vortex. ‘Cousin Martin, this is a sad time to meet for the first time.’

Without further ado she grasped her father’s arm, turning him around and walked away from the station, our signal to follow her.

Aine led her father tenderly across the snow covered expanse of the station’s car park to a bottle green Volvo Estate. A man jumped out of the driver’s seat as we approached. He wore polished black leather shoes and a dark suit under a tailored, double breasted Camel Crombie coat. He had receding dark hair, shiny with gel and combed back close to his skull. His eyes were smiling and a light, almost translucent, blue. His skin was the sallow colour of someone who enjoyed sunshine.

‘’Ello, Trevor’s my name, Aine’s ‘usband. You’re very welcome,’ he said, extending his right hand to shake while his other hand opened the rear door of the car. I noticed he wore a gold sovereign ring on the little finger of his right hand. We all piled into the car and set off. Trevor drove.

‘I’m sorry this is all a bit rushed,’ Aine explained, ‘there won’t be any funeral service, just the burial and we’re going straight to the cemetery. No-one wants to be standing around too long in this weather.’

‘So you came over this morning on the nanny and Wayne, Brendan, you must be cream crackered?’, Trevor asked my father who looked at him, nonplussed. He looked at me. ‘He asked if you came over this morning on the boat and train, are you very tired?’ I translated. He looked even more confused. ‘Nanny’ or ‘nanny goat’, the boat; ‘Wayne’ or ‘John Wayne’, the train and ‘Cream Crackered’, ‘knackered’ or tired,’ I translated.

‘Oh, I’m sorry. Cor, where’s my manners? I use the ‘slang to wind up Sean and his mates. ‘Ow’d you get ‘ere, Martin?’ Trevor asked me.

‘I flew over yesterday morning. I had some business. I met Dad off the train at Euston.’

‘Right, well, we ‘ad the service last night and the burial is booked for 10.30 so we’re going straight there.’

The snowfall had worked itself up to a blizzard again as we pulled into the car park of the Kingston cemetery. The snow swirled in blinding gusts. A group of people, huddled together in the freezing wind, opened as we approached. Most of them were men of my uncle’s age. They were all dressed in dark overcoats, some of them wore hats. There were a few young women too of Aine’s age and no doubt, close friends and perhaps, daughters of the other men. There was a buzz of introductions led by Aine and Trevor. All of them greeted Trevor warmly. I heard some murmurs of ‘Dia dhuit’ and ‘Dia’s Muire dhuit’, Gaelic greetings of ‘God be with you’ and ‘ May God and Mary be with you.’ A few of the men, gripping uncle Sean by his wrist and elbow, whispered ‘Is trua liom do bhris’ or ‘I’m sorry for your loss.’ Their accents reminded me of an Atlantic breeze in Clifden, Connemara.

A taxi approached. In the white blur of the cascading snow, a woman emerged backwards from the rear of the car. She wore a brown, knee length, fur coat and full length, black leather boots. When she straightened up, we could see she wore a matching fur hat. ‘It’s Auntie Bridie,’ Aine announced, surging past us, her arms outstretched in greeting. The figure in the fur raised her head to view the oncoming welcome while holding her hat with one hand and the front of her coat, with the other. She wore skin tight, brown leather gloves. She appeared to ignore Aine’s embrace by turning sideways and presenting her cheek to her niece. Aine engulfed her with her arms, apparently unaware or ignoring the slight. She planted a kiss on her aunt’s proferred cheek and taking her elbow, steered her to our huddled group. My father stepped forward, taking her gloved hand and pulled her close to kiss her other cheek. ‘Hello, Bridie,’ he said. ‘Brendan,’ she replied. She turned her attention to me. ‘Who’s this?’ she asked no-one in particular, ‘not Martin? My God, I wouldn’t know you, you’ve grown so much.’ I was 10 when I saw her last. Finally, she offered a gloved hand to Sean, the widower, muttering, offhand, ‘I’m sorry for your loss.’ Sean shook her hand but her presence hardly registered with him. The taxi driver pulled his car into a spot beside Trevor’s in the car park.

Sean’s friends gathered the coffin from the back of the hearse. The priest, his white cassock covered in an overcoat, his head covered by a dark, cloth cap, trudged off in the snow, leading the men who held the coffin aloft on their shoulders. Sean and the attentive Aine, followed. Trevor lingered behind to walk with us. Aunt Bridie didn’t acknowledge his existence. We walked, silent, heads down and concentrated on our steps in the driving snow, whipping into our faces at an impossible angle.

The service was short as our small party gathered around the open pit and the coffin was lowered down. We all murmured a response to the priest’s prayer even though only parts of it could be heard in the wind that battered and blew among the headstones.

The party made its way back to the car park. Trevor and Aine invited everyone to follow their car back to their house where food and refreshments would be served. Aunt Bridie, who hadn’t spoken to anyone throughout the brief service apart from the few words exchanged on her arrival, now demurred. She looked as though there was a stone in her shoe and wore an expression my mother used to describe grumpy people, ’she’s a face on her like a fir hatchet,’ meaning it looked sharp and mean.

Trevor and Aine wanted Dad and I to travel in their car. Bridie wanted us to travel in her waiting taxi. My father whispered something to Aine and then motioned me towards the taxi. There was a strained silence in the car as we wound our way through the streets of Kingston. It was broken by Bridie, ‘why was there no church service? Had she no friends besides his cronies? You’d think they’d’ve organized a reception in the local hotel.’

‘Will you shut up, Bridie,’ my father exploded. She was speechless, her jaw hung open as though she’d lost her next sentence. I was surprised by my father’s outburst. ‘Have some respect,’ he finished. Bridie looked like she’d been slapped.

We were the last to arrive at the house, a small, neat semi-detached house with a short driveway in a narrow street. Aine stood at the door to greet our arrival, a warm, inviting beam in her face. ‘C’mon in out of the cold. Give us your coats, go into the lounge. Trevor’ll get you a drink.’

Dad walked in ahead of myself and Bridie. She pulled my arm as we crossed the threshold. ‘I didn’t want to come here,’ she said, looking around her as though she’d entered the chamber of horrors in Madame Tussaud’s. She made no effort to take off her fur coat or hat and stood apart in the doorway of the tiny lounge. All of Seamus’s friends and, I assumed, members of their families as well as friends of Trevor and Aine, were packed inside, nursing tumblers of whiskey and cups of tea. A few held glasses of stout.

The lounge recessed, through an alcove, to the house’s parlour and beyond that, to a conservatory spread out into a small back garden. Trevor tended bar behind a small, white, leatherette lounge bar affair in the corner, complete with optics of whiskey and gin, an array of glasses and a small fridge. Sean stood in the corner, to the left of the bar, nursing a tumbler of whiskey with that same faraway look he had at the graveside. He was surrounded by his friends who filled the silence.

‘Aon sceal a’at?’, one of them asked another.

‘Deabhail sceal,’ another answered, ‘mura bhfuil sceal a’at fein?’

My own Gaelic was rusty but I was aware Seamus and all his friends hailed from the same small village in west Connemara and had taken the boat to England together. One had asked , ‘what’s the story?’, I guessed, to which the other replied, ‘divil a bit, have you no story, yourself?’

I needn’t have worried about my father. Nursing a whiskey, I heard him ask Seamus, ‘Ni fhacas Peadair, ’n’fheadair a bhfuil se lasmuigh?’ He mentioned Peter, Sean’s son and Aine’s brother, and enquired about his whereabouts.

Sean looked at him as though he was only noticing him for the first time.

‘’Peadair?,’ he said, ‘an creatur bocht. Ni raibh se in ann teacht abhaile.’

(Peter? The poor creature, he wasn’t able to come home).

‘Ca bhfuil se?’ my father asked.

‘San Astrail,’ Sean replied, the faraway look, creeping back, ‘le fada an la anois.’

(‘In Australia, this long time’).

Aine and the other ladies busied themselves in the kitchen. Bridie had opened her coat but had yet to discard it. ‘You’ll roast in that, Bridie, take it off and ‘ave a drink,’ Trevor offered. Bridie visibly recoiled. Trevor looked amused. Sean’s friends exchanged questioning looks. One of them said, ‘Bean lach is ea I, ‘bhfuil fhios a’at, ach ta nimh inti.’ (She’s a fine woman but there’s poison in her.)’

The flow of drink woke the gathering and thawed them from the cold of the cemetery. Bridie provided some diversion and amusement and the assembly of souls with a common home and language, warmed them all. They were getting hungry too.

Almost on cue, the partition doors to the kitchen were flung open by Aine and one of her helpers to reveal a long table laden with sausage rolls, spicy chicken wings, pork pies, sandwiches of a hundred fillings from ham and cheese to poached salmon and mayonnaise, egg and onion and chicken and stuffing. The men burst in to spontaneous applause and one let loose a whoop of celebration. They crowded round the table while Aine and the ladies filled their plates.

Bridie caught my arm as I made my own way to the table. ‘Don’t touch that food, Martin, that’s awful stuff,’ she said.

‘BRIDIE,’ my father said, so loudly, he stilled the room, as he walked into the hallway without looking at her. She followed him. Everyone tried not to listen to what was spoken behind the half closed door. Trevor nudged me. ’They’re a rum lot,’ he said, nodding fondly at his father in law’s friends. ‘You get on well with them,’ I said. ‘I love ‘em. We never stop ribbing each other. These guys might live in London but their hearts are in the west of Ireland sometime in the ’50s, I fink.’ At least they have a home, I thought, wondering about poor Aunt Bridie. She was clearly uncomfortable but she’s lost her sister, too. ‘What do you do, Martin?’ Trevor asked. ‘I’m in public relations,’ I said and then, aware of the irony of my own situation, we both laughed.

The hall door opened and my father returned with Bridie, without her coat and hat. Trevor handed her a glass with a smile, ‘have some Calvin Klein,’ he said and filled her glass with wine. One of Sean’s friends produced a button concertina and played a tune. Another called, ‘Michael, cas amhran.’ (Michael, sing a song). ‘Nil me in ann, cas tu fhein ceann.’ (I can’t, sing one yourself) and without further ado, the singing started. There were sad songs, dancing songs and funny songs. My father recited a poem, an epic tale of Robert Service set in the vast snowlands of the Canadian tundra. Even Bridie, her inhibitions lost, sang ‘If I were a blackbird’ and everyone cheered her effort.

At six o’clock, my father turned to me and said, ‘it’s time I was leaving.’ We gathered our coats and said our goodbyes. A taxi collected us at the door and brought us to the station. We made it to Euston station with only minutes to spare. My father said he’d see me in Dublin. I handed him a bag of sandwiches and chicken legs wrapped in tin foil Aine had slipped me as we left. His parting words to me were ‘never forget your home’, then he turned and walked down the platform and onto the train.

May 6, 2016

On eating that which is real (and being relaxed about it)

Fads can kill, just like fats. Trust yourself to find the flavour, don’t leave it to the chemicals

Americans never adopt fads lightly. When we take up a cause, we commit and we go to the extreme. Moderation is a virtue that we never seem to have much needed in the United States of America. Be it the size of our homes and cars, the depth and breadth of our reality TV, our fervent denial of climate change, or our mass accumulation of guns, we do nothing on a small scale. We take on nothing lightly. Nowhere does this tendency seem more clear to me than our current obsession with food.

We could talk about how enormously fat Americans are, which is true, but I am interested in the other side of the spectrum, where people are fixated on healthy food, where we consider ourselves holy because we have not (yet) slipped into obesity. It’s one pole or the other for me and my fellow patriots: Either we wantonly stuff ourselves…

View original post 590 more words

Apple Stole My Music. No, Seriously.

Signing on for Apple Music is like taking a leap, head first, down a rabbit hole

“The software is functioning as intended,” said Amber.

“Wait,” I asked, “so it’s supposed to delete my personal files from my internal hard drive without asking my permission?”

“Yes,” she replied.

Maybe I’m Not Pressing the Keys Hard Enough.

Maybe I’m Not Pressing the Keys Hard Enough.

I had just explained to Amber that 122 GB of music files were missing from my laptop. I’d already visited the online forum, I said, and they were no help. Although several people had described problems similar to mine, they were all dismissed by condescending “gurus” who simply said that we had mislocated our files (I had the free drive space to prove that wasn’t the case) or that we must have accidentally deleted the files ourselves (we hadn’t). Amber explained that I should blow off these dismissive “solutions” offered online because Apple employees don’t officially use the forums—evidently, that honor is reserved for lost, frustrated people like me, and (at…

View original post 1,263 more words

May 5, 2016

An open letter to White people who tire of hearing about slavery when they visit slave plantations: especially Suzanne Sherman.

Having read your letter, I had to take the link back to the original story and The American Conservative. Now I could get a measure of your own restraint in your thorough refutation of his point, that the tours of the two houses mentioned, was somehow imbalanced by the inclusion of the history of the enslaved workforce of these houses. What struck me was the writer’s blindness to the inherent irony in his own argument, for if, as he wished, the tours spoke more of the contribution and formulation of political ideals of the inhabitants of these houses, then these ironies would’ve become immediately apparent. This is a great read.

Dear Ms. Sherman,

When I read your reflection in The American Conservative I was so sorry to hear that you had mistaken the museum at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello for a monument to the Declaration of Independence. This mistake clearly caused much despair to you, and I suspect, to your unwitting children, who later found themselves flung headfirst into the depths of their mother’s folly before a crowd of annoyed weekenders. And so, though it was due to your own mistake, I offer you my sympathy and am glad to hear, for the sake of your emotional well-being, that out of the glare of national attention, on a lesser known property, Jefferson’s Poplar Forest estate, you were able to receive the version of history which you most preferred. For the sake of people like you, if it would not be such a terribly expensive endeavor, mental health professionals might find it…

View original post 1,681 more words

Down on the beach

https://dailypost.wordpress.com/prompts/beach/

The beach was packed. The local boys were diving noisily from the rocks beneath the high board. There was a natural, deep pool there when the tide was in and occasionally one of them would answer the jeers of his friends by climbing the ladder and taking the high plunge.

She was standing with her friends, the same two girls, Mary and Collette, the twins, by the ice cream stand. She was wearing a pink bikini; they wore matching turquoise blue swimsuits. She was holding a 99 in one hand. Her other hand was behind her back, half covering one cheek of her pink suited bottom.

Down on the beach on that last day, being a non-swimmer and, embarrassed about that, he paddled and dipped in the shallows, far from the rocks and the diving board where the other boys dived and jeered each other. In the distance, he saw her step out of the water where she swam and for just a moment, a split second, she forgot the hand that protected her pink cheek and he could see why. There was a tiny hole, near the waistband and he caught a brief glimpse of white skin, untouched by the sun.

The Tower in my Back Yard

Thursday photo prompt – The Tower… #writephoto

I live in the grounds of an old church, St Nicholas of Myra, in The Liberties in Dublin. It dates back to the late 18th century. This is the view out my window, morning or night.

First Day At School

Hi, first, my checklist. Clean, behind the ears, pencil, bus money, lunch, notebook. Right, this is my first day in school. I’ve just signed up for a blogging basics course and this is my first task. Stand up, in front of the class and tell you who I am.

My name is Dermott. I’m a writer.

Pause.

Aren’t you guys supposed to say? No, no, forget it, that’s a different…I’m a little confused.

Ok, let me start again. I first began writing when I realized pens were not just for chewing. I published my own newspaper in school (https://dermotthayes.com/2016/04/27/an-obstacle-is-a-challenge/). I changed schools a couple of times and in different places but I always loved writing.

After spending some time on the academic trail – I studied politics and history, wrote some research papers, did some teaching – then I became a journalist and worked for many national newspapers in Ireland and the UK and as a freelance journalists for newspapers and magazines around the world. For a short while I was People magazine’s correspondent in Ireland . I wrote about music for MOjo, Q, Select, Noor and Rolling Stone. After 25 years in newspapers, my last job was as Showbusiness Editor of the Irish Mail on Sunday, I gave it up and decided to stick to writing my own work.

Since then I’ve published two books, Postcard from a Pigeon and Other Stories, a collection of short stories and Tito’s Dead, a crime fiction novel. I am writing another, currently.

I’ve dabbled in film making and scriptwriting. Everything is a learning process and if I’m not learning, I’m not interested. I’ve made a couple of video poems that can be seen in the drop down, ‘videos’ menu on my site. Last year, I made a short film, https://dermotthayes.com/2016/04/12/1916-souls-of-freedom-2/ to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Easter Rising in Dublin, 1916.

I joined WordPress more than a year ago but never put any time or conviction into it until the past six weeks. Now, I love it because it’s an excellent forum to develop ideas, take on prompts and challenges, check out other people’s work, get feedback and comment on new fiction.

What a mug

https://new2writing.wordpress.com/2016/05/05/maydays-prompt-the-break/

They only make them in plastic now. When I got mine is was a stoneware stein, a heavy vessel for swigging beer. It was a wild, stormy night, near a town called South Euclid, Ohio. The rain pelted down so hard, each dropped bounced back, a foot high and as I descended, on foot, off the highway, soaked to the skin, I remember thinking I’d love a beer, right then. I was hungry too but, as they said at home, my throat was cut for a sup. I knew the Notre Dame campus was right down here, somewhere, close to the interstate.

Six days I’d been on the road, through deserts, over mountains and across broad plains of corn, as far as the eye could see. I’d slept on the roadside, in campus dormitories and once, in a railroad carriage. Hitchhiking, back then, was an adventure but don’t get me wrong, even then, in 1974, it was a dangerous adventure.

Many well-intentioned people pick you up out of the goodness of their heart but there were predators, too. The best ride I got brought me from Cheyenne, Wyoming on I80, all the way to Chicago, Illinois. Chuck and Jess were driving a black and chromed up Lincoln Continental, the most unlikely mode of transport you could imagine for a pair of old motorcycle bandits.

They had a cooler full of beer in the back seat and I sat upfront with them, all the way across Nebraska and Idaho, drinking beer, smoking reefer and singing along to Chuck’s collection of Lynnrd Skynnrd 8 Tracks. Occasionally, we’d get surrounded on the highway by leathered up, road dusted, motorbike gangs in their charging hogs and choppers and they’d exchange greetings, joints and beer before moving on down the road.

Shortly after they dropped me off, a man, middle aged, well dressed, neatly groomed, tried to rob me but I got away from him. You could never be too careful.

So here I was, trudging up to the flood lit football stadium on the Notre Dame campus where pre-term training was in session and I did what every traveling student did in those circumstances, I played the Irish card. C’mon, what did you expect? Hey, I said to one of the guys, as soaked as I was, except he was in his football gear, I’m an Irish student, traveling, I need a place to stay, can you help?

Help? They brought me back to their dormitory. People were dispatched to round up a crowd and as many beers as they could muster. Food was found and my clothes were taken to be laundered and dried. I dug one dry pair of jeans and teeshirt from the bottom of my back pack. Pretty soon, the party was in full swing and from there, my memory blurs. The following morning, after breakfast. the guys presented me with my Fighting Irish beer stein, the receptacle from which I had drained an entire can of beer without breath, the previous night. I packed it away and promised I’d cherish it.

Three months later, back home in Dublin, I was packing up, again, leaving home for a student pad of my own on the other side of Dublin. My mother fussed about, packed a Tupperware box of sandwiches, a couple of hardboiled eggs and an apple – in case you get hungry and there isn’t anything in your place – and as she dressed my abandoned bed to keep her self busy she bumped the shelf above my bed and an avalanche of football trophies, medals, model cars and my Fighting Irish mug, hit the ground, hard. The mug shattered and so, I believe, did my mother’s heart.

She was inconsolable in her contrite grief, mortified to have shattered my trophy from my travels. She cried and cried. Then I cried, too because she wouldn’t stop crying and I was a big boy now and it’s only a fucking mug, for God’s sake and there’s no need for you to be cursing about it, what kind of language is that? I’m sorry, Mammy, then we cried again as she picked up the shards and vowed to put it back together again.

And I gave up, piled my backpack on my back again and left, ‘cos I was a big boy now.

May 4, 2016

Mayo, across a lake

Postcard from a Pigeon

- Dermott Hayes's profile

- 4 followers