Dermott Hayes's Blog: Postcard from a Pigeon, page 86

May 3, 2014

IVAN (a sample chapter from TITO’S DEAD, my first novel)

IVAN

Ivan hitched the collar of his black leather overcoat round his neck. He sniffed at the rain as he stepped out of his car into the gloom of the alley, lit by the flashing light of a patrol car. A sullen drop hung from the tip of his nose.

Four shadowy figures stood around the crumpled heap on the ground, silhouetted by their own cigarette smoke. They might have been digging a hole, he thought, and had stopped for a break to talk about it. Rain was everywhere. It eddied in pools and potholes. Ran down the walls. Splashed and spattered off every surface. This was rain that soaked to the bone. Inspector Ivan Toscic of the Sarajevo Municipal Police felt the chill. ‘Another fucking dead one’, he thought.

His own cynicism startled him like an unwanted guest at a party. The body lay hunched in a dark, dimly lit and rain soaked back street of Sarajevo. A single bullet hole in the back of the skull had made sure the young man would never worry about the weather again. There was no decomposure. They’d found a fresh one. Here was the body of a young man, possibly in his mid-twenties, fashionable, even expensive clothes, stylish hairstyle, good shoes. Dead. Toscic thought he looked peaceful. Take away the sticky hole in the back of his head and he’d be sleeping.

He had seen worse. Bodies maimed, tortured, burned or blown up. He had waded through the aftermath, his socks and shoes so regularly seeped in gore and burnt tissue he’d taken to storing a pair of gumboots in the boot of his car.

So it began, again. His job was to find the killers. But war turns a policeman’s job into farce. He becomes merely part of the process, supervising the production line. Violent death is routine. Someone gets killed. A body is found. The police record and investigate. The paramedics mop up the blood and shovel the body parts into bags. The police tag the body bag. The rain and the City sweep the memory away.

Ivan felt nothing and worried about not feeling regret anymore. Never get involved, was the policeman’s mantra. Yet Toscic believed the reverse was true. Were he not to feel something, he thought, then he would be as bad as this young man’s killers. Yet he felt nothing. He might be investigating a traffic violation. This young man had been clamped for life and he could never talk his way out of it.

Toscic thought through the scene – an alleyway, darkness, the body of a young man, a single bullet, a look of easy contentment, the rain. The location was remote so there would be little chance of witnesses. The rain would obscure whatever forensic evidence might be gleaned from the scene, footprints, tyre prints, even saliva. The bullet would offer nothing in a country where everyone carried guns and no-one had a licence.

This was an execution. The motive, he guessed, was commercial rather than some passion fomented in Sarajevo’s seething ethnic cauldron. Just some tit for tat partisan killing that went on every day and night, even in a ceasefire. The war is over and the UN wants to go home. But the killings continue as the hate seethes beneath the surface calm.

There were no signs of a struggle or restraint. Death was sudden and precise. There were no placards of denunciation, no hastily discarded, half destroyed clues. Someone was taking care of business and they had no interest in anyone else knowing. An anonymous caller reported the death. That was not unusual. No-one wants to get involved. Not even the team of street cops, paramedics, SOC forensic investigators, or anyone in this circus called to another crime scene. It was wet and dark and cold and no-one, least of all the poor crumpled stiff being stuffed and zipped in a body bag, wanted to be there.

Sarajevo, like any border town in a war, like all the war torn cities in all times and down the ages, had its own war town economy; a thriving underworld that would supply you with anything from Stinger missiles to AK47s, hashish to heroin, bread to caviar, passports to people. The gangs who ran this underground criminal network were the flotsam of conflict; ex-soldiers and partisans, full time criminals, opportunists and the organised terror gangs from the east, the so called Russian and Albanian mafia who ran everything from sex to guns, drugs and refugees. Life is simply another commodity. If it’s served its purpose, get rid of it.

Toscic stood for a moment in the mouth of the alleyway, silhouetted by the street light and the cold shroud of rain. He stared at the only thing the dead man was carrying. Carefully wrapped in a sealed Jiffi bag for fingerprinting purposes, was a crumpled postcard of a bar in Dublin, Ireland. In the dim light, the rain had already taken possession of the bag in his hand. A beaded mist of damp clung to its surface. The bar in the postcard looked cheerful and inviting. Death had dried his throat. Ivan felt his own thirst rise at the thought of standing among the living in a warm bar.

He stared at the hand written message on the back of the card but didn’t recognise all of the English phrases and made a mental note to check it out with the mad Irishman. He put the card in the inside pocket of his sodden overcoat, cast one final glance over the murder scene as the twin doors of the ambulance were slammed shut. Then he turned and walked to his car.

http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00JQC2ODY

May 2, 2014

Thoughts on the writings of James Lee Burke

The comment that has surprised me most since I published my first novel, TITO’S DEAD, last week, is, ‘A Crime novel? I wouldn’t have seen you writing a Crime Mystery’ novel.’ Why not?

Mystery and crime are two phenomena no-one’s short of, in fiction or real life. But I think I got my love of crime novels from my father who read everyone from Arthur Conan Doyle to Mickey Spillane, when I was growing up. I sought them all out, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Doyle, Spillane, Maupassant, Ellroy and, more recently, Harlan Coben, Ian Rankin, Michael Connelly but, above all, James Lee Burke.

James Lee Burke’s Dave Robicheaux novels are never ‘typical’ crime novels. First, there’s Robicheaux, a disgraced, former NOPD Homicide lieutenant turned sheriff’s detective in Iberia Parish. Robicheaux is a good man with a chequered past; a Vietnam veteran and recovering alcoholic who carries traces of post-traumatic stress disorder and an unspecified, but lingering, guilt from the eruption of his parents’ marriage, his father’s death and his mother’s violent murder at the hands of corrupt, NOPD detectives.

His background is working class,backwoods, Louisiana Cajun. He’s Catholic. He runs a bait shop and bayou cafe when he’s not detecting. He has problems with authority, is single-minded in his pursuit of wrongdoers, corporate polluters and the antebellum remnants of the southern ascendancy. Robicheaux, although an essentially good man, has a violent streak.

Some of Burke’s other novels, like Two for Texas, are historical explorations of the complex forces that combine to make up Robicheaux’s contemporary environment; Louisiana’s sub-tropical swamplands, struggling to survive against the elements of natural phenomena like hurricanes, corporate greed and pollution and the complicit dealings of corrupt politicians, police and the Mafia. Into this milieu in ‘In the Electric Mist’, he introduces a story about a violent and sexually perverted, serial killer, an alcoholic, Hollywood actor with psychic leanings and a sociopathic, Mafia boss turned film producer. The actor taps in to Robicheaux’s own psychic inclinations by introducing him to the ghost of a one legged, one armed, Confederate general who, along with his ragged bunch of soldiers, haunts the swamps around his home.

Now he’s worried it’s just a dry drunk dream or living nightmare or has he conscripted himself into a new struggle with the Confederate dead, to fight the forces of evil, whether corporate, criminal or perverse or combinations thereof, that threaten his life and the lives of those he love as well as the environment they live in?

I’ve read everything I could find of James Lee Burke’s and I’m a fan.

Breaking Facebook rules…

Facebook Pages are an easy, cheap and relatively efficient way of reaching a local, target audience, assuming, of course, that you fall on the right side of completely annoying.

Every self publishing author will tell you, Facebook, Twitter, blogger, these are the routes to getting about your presence and the book you’ve just published. Tell people, engage people, make them want to read your book…these are the usual mantras, humming through the ether. Your friends are the first to feel the impact of this charm and smarm campaign; first, by email, text and messenger service and then, by direct confrontation, pleading, short of outright begging and then rage, guilt, denial and acceptance. Or, was that something else?

The point is, if you’re self publishing, you’re selling; get used to it. Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. On the one hand, you could bury yourself in the multitude of online guides to self publishing, most of them written by people who’ve become best sellers, selling ebooks on how to sell a successful ebook. You might, also, join the many ebook ‘writer’ sites on the internet, who will assure you that while joining them may not guarantee million plus sales of your book, it might help and it certainly won’t harm you. On the other hand, you could ‘upgrade’ your membership to ‘full’ or ‘premium’ and take advantage of the online marketing tools they provide and to which you can only get a fleeting glimpse, with their ‘free’ membership.

One of the most insidious of these, I believe, is the ‘facilitator’ companies that provide formatting tools and e-vetting roles for the big, non-Amazon, epub retailers. In reality, they’re buffer zones, housed by middle men and, like agents and publishing houses, they’ll take a chunk out of you for doing very little.

Trying to do everything on your own, exactly what you’re encouraged to do, will leave you hung up in traps and pitfalls you could never imagine.

To write my two e-books, Postcard from a Pigeon and Other Stories and Tito’s Dead, I set out to find a software package that would allow me to format my book in multiple online formats. There’s a whole bunch of them about but I settled on Scrivener because, for one, it’s good value and two, it does everything I needed and can format .mobis for Kindle, .epubs for iTunes, Sony, Nook, Barnes & Noble and the ever growing, legions of online libraries. I registered with Nielsen Book Data and bought a bunch of ISBNs. Then I got myself a simple publishing design app for my iPad, to help me design the book’s cover.

I’ve taken to blogging more frequently than I used, although, having worked as a journalist for more than twenty years, I’m no stranger to deadlines. I try to ‘twit’, but I find it almost debilitating, from a moral and morale, perspective. Face it, the majority of the aptly named ‘twits’ to be read, at any given moment, are, quite frankly, moronic.

So I set up a Facebook PAGE called Tito’s Dead – https://www.facebook.com/HANNIBALTHEHAT – to propagate news of my book’s publication. It’s my first novel and I’m very excited about it, unfortunately, in direct and inverse proportion to the number of people who are aware of it, have any interest in it or who may become even vaguely curious about it. I could use my own Facebook page to ‘plug’ my book but I haven’t. Not much, anyway and certainly, not anything like the cloying, annoying self promotion engaged in by some of my contemporaries. One person, in particular, writes obscenely frequent, cloying and puke inducing self promos, he’s a classic example of the phrase, ‘if he were a lollipop, he’d lick himself.’

Facebook Pages are a moneymaker for the global social networking site. You can ‘boost’ your Page to gain more ‘likes.’ Of course, as everyone knows, this is the insidious, deep and not so furtive, penetration ploy that gets your foot in the door of everyone else’s contacts and opens the potential exposure of your book. Boosting individual posts, I’ve found, is far more effective.

A post should take an attitude, inform, entertain and, in the most subtle fashion possible, sell, too. Of course, there are rules regarding the words and content of the pictures you use. If you want to post a picture, then do that and that alone, saving the verbal, not for the picture but for the comment slot that says, ‘write something about this post…’

with this simple message…TITO’S DEAD is now available for download from Amazon Kindle, as a .mobi and from Smashwords, as a .epub…download the free Kindle app to your phone, iPad, Tablet or laptop, download the book, and you’re away, ENJOY.

I also did a Page promotion which, though it ‘reached’ more than 10,000 people, only garnered 14 ‘likes’ in the three days that it ran while my own, direct promotion brought me 150 ‘likes’ in two days.

So I decided on something different. I would ‘post’ a chapter of my book by way of a ‘free sample’ induction. This is the short description of the book, ‘Tito’s Dead is a fast paced crime mystery set in Sarajevo and Dublin and follows undercover, Europol cop, Bernard Nolan, on a manhunt to find a killer and expose a crime syndicate that stretches across a continent and into high office, against a backdrop of treachery and double dealing, where he can trust no-one and time is running out…’

Now let’s assume that if there’s a killer, there must be a murder, right? The chapter I chose to post is called ‘Ivan” and it’s the third chapter in the book when they body of a young man is found, shot dead, in a dark alleyway in Sarajevo, by Bosnian detective, Ivan Toscic. So, I boosted the post. It was paused and rejected by the Facebook Ads team. This is what they told me, ‘Your ad was rejected because it violates the language policy of the Ad Guidelines. The title and body of your ad may not be insulting, harassing or threatening to other people. You may not use profane, vulgar, or threatening words in the body or title of your ad. Additionally, you can’t use any words that mentions or targets someone’s personal characteristics (ex: age, gender, race, etc.).

To resubmit your ad, edit the text from your ads manager.’

I questioned this, adding, ‘It is a sample chapter from a new novel. There is no intentional profanity. It is clearly introduced as a piece of fiction. I will not censor my own writing.’ To which they replied, again, ‘Your Post wasn’t boosted because it violates Facebook’s ad guidelines by including profanity or language that refers to a person’s age, gender, name, race, physical condition or sexual orientation. The post is still published, but it is not running as an ad.’ To which I countered, ‘Ridiculous.’

I added, ‘Facebook’s advertising manager has replied to my query of their decision to block my promoting or ‘boosting’ a Page post because it broke rules about language and identifying someone by age, dress and ethnicity. The post in question is a sample chapter of my book, Tito’s Dead and the chapter describes the discovery of Tito’s body by a Bosnian detective.

It’s fiction, I argued, and how else can you describe a dead body, except by age, dress and ethnicity?

So Facebook had second thoughts about the whole thing. They wrote, ‘Thanks for following up on this. It appears your ads were mistakenly disapproved. However, they’ve now been re-reviewed and approved. Sorry for any inconvenience.

Please note that although we approved your ads, these ads may remain paused until you resume them. You can access your ads and change their status at any time by clicking the Ads Manager or “Ads” tab in the Applications menu when you are logged in to your account. Then, to reactivate an ad:

(1) Click on the name of the campaign that contains the ad you’d like to reactivate.

(2) Under the “Status” column, slide the bar into active mode. ‘

Of course, I had another ‘go’ at it. And, unfortunately, if inevitably, the promotion had ‘timed out’ and ‘boosting’ was no longer an option. Not unless, that is, i return to my first step and then post the chapter, again before ‘boosting’ it. Then, of course, there’d be the pause and rejection stage, but at least I’ll know most of the pitfalls this time, unless they come up with some new ones.

Franz Kafka would’ve had a heyday in this age of online vetting and form-filling. It’s like The Trial, Online.

April 26, 2014

The Whys and Wherefores, of Writing

I bought a collection of short stories last night by the American writer, James Lee Burke. It was the last of Mr Burke’s books, to complete my collection. It’s called The Convict and Other Stories. In his Introduction: Jailhouses, English Departments and the Electric Chair, he writes about his own experience as a writer; the rejections, the defiance, the drinking, the teaching and then his inability to learn.

James Lee Burke is not only one of the most successful detective crime writers alive today, he’s also one of the best living American writers. His powers of description are breathtaking and he can stop you breathing with the emotion of a moment. He stands with John Steinbeck and Kurt Vonnegut Jr as my all time, favourite American authors.

I’ve learned from all three of these writers and many more. One of the first lesson any writer learns, is to become a reader, then, an observer. Sometimes, after reading someone like Burke, I’d begin to think there was nothing I could write about to match someone like him. Louisiana, Texas and Montana – his favoured locations – just seemed to have that much more going for them. John Steinbeck wrote about hobos and the dust trail from the Texas panhandle to the Californian fruit fields, migrant workers and underground agitators. Kurt Vonnegut wrote about soldiers and aliens. Desperation set in if I thought about my own paltry settings.

Then I realized I wasn’t looking at things from the right angle. I could say James Joyce taught me that, but I won’t. I’ve read big chunks of Ulysses and the short story collection, Dubliners. But it took me four weeks to get through 15 pages of Ulysses on my first attempt. Brendan Behan and Sean O’Casey taught me a valuable lesson. Stories are not just on your doorstep; they’re in your head. You have to get them out. I’ve got more pleasure out of reading John McGahern, William Trevor, Sebastien Barry and Joe O’Connor. These are writers who understand scene and setting. Roddy Doyle has the same talent.

Reading can satisfy writers, but it also makes them restless. Restless, to get their own words and thoughts down in print. And that makes the difference between a reader and a writer. Every reader will entertain the thought of being better and more able than a writer, to capture the moment of their lives that encapsulates their thought processes and sums up their existence. It is the writer who writes it.

April 24, 2014

Publishing is painful

Writing your first book is an apprenticeship and there are plenty of ‘long stands’.

I’ve written three books and, although TITO’S DEAD is the third, in my mind, it’s my first.

The ‘first’ was Sinead O’Connor, So Different, an unauthorised biography of the frequently celebrated, never celebrity and often castigated Irish singer. I remember saying it was only a footnote to a career and life that would grow, on and on. It’s long since out of print and original copies trade for as much as $100 on eBay .

The second was Postcard from a Pigeon and Other Stories, a collection of 18 short stories that, I hope, reflect events and changes in Irish life, over 50 years.

The third, but for me, the first, is TITO’S DEAD. This is the description of the novel on Amazon, ‘Tito’s Dead is a fast paced crime mystery set in Sarajevo and Dublin and follows undercover, Europol cop, Bernard Nolan, on a manhunt to find a killer and expose a crime syndicate that stretches across a continent and into high office, against a backdrop of treachery and double dealing, where he can trust no-one and time is running out… ‘

it does, in brief, describe what goes on, but, it’s strange and illuminating, how writing these things can concentrate your mind and even let you see your own work from a different perspective.

For example, after I wrote this description for Amazon, I added, on reflection, ‘Tito’s Dead is the first novel by Irish writer, Dermott Hayes. It tells how a simple human act in this 21st century world, can be misinterpreted as weakness and its meaning, distorted, into a maelstrom of deception, hate and treachery.’

And in the ‘from the author’ section I wrote, ‘TITO’s DEAD began life as a short story, about a young Kosovan refugee, living in Dublin, who befriended an injured pigeon and nursed it back to health. That simple act of kindness for an injured creature, earned him respect, for himself and from those who watched him. It made me wonder why, without that simple act, we couldn’t see he was injured, too? ‘

I gave the manuscript to half a dozen people from different walks of life and points on the global compass and these helped refine, even define, my own understanding of the book. I imagine critical response will have an impact, too.

Writing the book started with a thought and a chance meeting with film maker, actor and screenwriter, Terry McMahon (Charlie Casanova, Patrick’s Day), one day in the bar of the Clarence hotel; so that was the inspiration, then I had to write it…

So, write it, Terry said to me and here I am, ten years later, and I’ve let it go to make its own way in the world. The first thing I did was lock myself away in a farmhouse in County Clare for two weeks. Many headaches, balls of paper tossed in a bin, later, I emerged with 25,000 words written and the feeling there was no going back…

Of course, there have been bumps along the way. An agent from London turned up on my doorstep one day. He said he’d read the first three chapters and wanted to sign me up. ‘You’re the new Harlan Coben,” he said, ” you’re Dublin’s Ian Rankin.” Since they’re two of my favourite crime writers, I was flattered. It was all a load of bollocks.

Two years later and I was rewriting, re-rewriting, and re-re-rewriting so much, I was getting dizzy. Two new hips didn’t help, either. My hot shot agent had acquired a bunch of best selling authors, particularly George Galloway MP, who was brewing up a storm of book sales and my pathetic rewrites were slipping to the bottom of an ever increasing pile. It also occurred to me that an agent’s primary interest is making money for him (or her) self and a best seller is the show, while first time author’s, well, if they don’t put up, they can go…And go, I did, without any hard feelings on either side once I got a letter from his office, refuting any future claim to my publications. Fuck it, if you don’t believe in yourself, who else will?

Disgusted and disenchanted by my initial flirtation with the world of publishing, I put all the manuscripts, the rewrites and the tears, in a box and out of sight, for four years. I didn’t stop writing, although I did pack in journalism.

I started writing short stories and they had a cathartic effect. As news of electronic book publishing chronicled the increasing popularity of the E book, self publishing became an achievable and affordable prospect.

My first foray into that world was ‘Postcard from a Pigeon and Other Stories’, published in 2012 and, happily, I don’t have enough fingers, toes, feet, legs, ears, eyes or balls to quantify its impact on the electronic reading world.

Once you decide to self publish, a whole new can of worms is opened.

Back in the 1980s, the global publishing world began to contract. It didn’t get smaller but the ownership profile of the publishing world did get smaller.

And, as the world of publishing contracted until there were about five main players who controlled the bulk of global publishing, so the number of books being published, annually, began to contract, just as global profits began to rise.

Of course, the nabobs and bead counters claimed this as a triumph of their accounting skills to weed out the unprofitable, give the people what they want and line their shareholders’ pockets.

They had a point, if you believe the world of literature, the act of creative writing, has a quantifiable, currency, value. On the other hand, their actions had an even more profound effect on publishing by usurping the role of the publishing house editors and replacing them with agents.

After that the primary prerogative for a new writer’s publishing potential was how much and how quickly they could make profits for publishers and commission, for the agents.

But enough about agents, because thankfully, there are still great writers among us and I doff my hat here, to Colm Toibin, Sebastian Barry, Roddy Doyle and Colum McCann, to name just a random few.

Global sales of digital books eclipsed the sale of print books, four years ago. And, if we believe all the self help pedalled on the internet, self publishing in this brave new digital world, is the only way forward.

Alas, it’s not quite as simple as that. Because what’s got forgotten in this world of ‘the bottom line’, is that a writer will write. That’s what we ‘do’, to make sense of our world and even our existence.

April 7, 2014

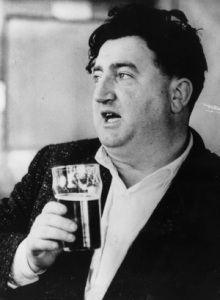

Brendan Behan, a lion roaring in a wilderness

BRENDAN BEHAN died on March 20, 1964. Fifty years ago and I haven’t heard a word about it by, or from, my own Government, the National Broadcaster, RTE, by the National Theatre Company, The Abbey Theatre or by the Irish Film Institute, the national archive of Ireland’s contribution to the film industry. So where, do they estimate someone who gave us The Quare Fella, The Hostage and The Borstal Boy, stands in the pantheon of great Irish artists?

Nowhere, it appears. If it’s to be estimated from this complete and outrageous act of cultural airbrushing that only rivals Stalin era to 1990 photo compositions of the movers and shaky shakers of Soviet power, like the West’s version of the Hollywood Oscar shakeup.

One year and 50 years since the almost totally ignored Irish workers’ revolution of 1913, since, conveniently, and ambiguously, known as ‘The 1913 lock out’, one of the greatest contributors to the hall of international fame’s list of Irish artists, Brendan Behan, died.

And we, since I can’t, in all fairness exonerate myself from blame here, failed to celebrate. Let’s consider why?

Brendan Francis Behan (/ˈbiːən/ BEE-ən; Irish: Breandán Ó Beacháin; 9 February 1923 – 20 March 1964) was an Irish poet, short story writer, novelist, and playwright who wrote in both English and Irish. He was also an Irish republican and a volunteer in the Irish Republican Army. Born in Dublin into a republican family, he became a member of the IRA’s youth organisation Fianna Éireann at the age of fourteen. However, there was also a strong emphasis on Irish history and culture in the home, which meant he was steeped in literature and patriotic ballads from a tender age. Behan eventually joined the IRA at sixteen, which led to him serving time in a borstal youth prison in the United Kingdom and was also imprisoned in Republic of Ireland. During this time, he took it upon himself to study and he became a fluent speaker of the Irish language. Subsequently released from prison as part of a general amnesty given by the Fianna Fáil government in 1946, Behan moved between homes in Dublin, Kerry and Connemara and also resided in Paris for a period.

In 1954, Behan’s first play The Quare Fellow was produced in Dublin. It was well received; however, it was the 1956 production at Joan Littlewood‘s Theatre Workshop in Stratford, London, that gained Behan a wider reputation – this was helped by a famous drunken interview on BBC television. In 1958, Behan’s play in the Irish language An Giall had its debut at Dublin’s Damer Theatre. Later, The Hostage, Behan’s English-language adaptation of An Giall, met with great success internationally. Behan’s autobiographical novel, Borstal Boy, was published the same year and became a worldwide best-seller.

He married Beatrice Ffrench-Salkeld in 1955. Behan was known for his drinking problem, which resulted in him suffering from diabetes, which ultimately resulted in his death on 20 March 1964. He was given an IRA guard of honour which escorted his coffin and it was described by several newspapers as the biggest funeral since those of Michael Collins and Charles Stewart Parnell.

And that’s the potted history from Wikipedia, And what about Dave Finnegan’s recent reflections in the Irish Times regarding the level of notoriety and acclaim Behan accrued from his exploits in New York in the late ’50s and early ’60, he enjoyed a celebrity so large it might be best described as what you’d get today if you crossed the literary credibility of Colum McCann with the tabloid notoriety of Colin Farrell.

One minute he was discussing Joyce with James Thurber and Burgess Meredith, the next he was on the front pages for drunkenly rampaging across the stage during a Broadway production of The Hostage . A few weeks into trying to figure out whether there might be an actual book to be wrung from this type of carry-on, I happened upon a quote from Frank O’Connor.

“I wish I had it in my power to suppress ‘Brendan Behan’s New York’ with which we are threatened,” wrote O’Connor in the week of Behan’s death in March 1964. “It will not be New York and it will not be Brendan. I should be happier to think that some young writer was gathering up the hundreds of stories about him that are circulating at this moment in Dublin and that would tell scholars and critics 100 years from now what sort of man he was and why he was so greatly loved.”

There are as many pubs today, in Dublin, where you can hear that many stories about him in a day and there is probably as many people you might meet, who could claim to have known him/drunk with him/ or witnessed a row between himself and Patrick Kavanagh as there wre people who claimed to have been in the GPO in 1916 or, to at least, have had a relative who knew someone else who knew someone who was there.

The point is, the one common, and the pertinent point is, common, denominator, is Brendan Behan, the writer, activist, republican or whatever, but above all, is a Dubliner and one who gave voice to a new generation of Dublin, beyond O’Casey, oblivious to , Swift, Wilde, Synge or Yeats, never mind the aforementioned O’Casey, Beckett or Joyce, a voice in a new country, a voice of the common people.

So here’s the thing…Behan became celebrated internationally, in the late ’50s for his autotbiographical, The Borstal Boy and subsequently, for his earlier writings, The Quare Fella and The Hostage. Films were made of at least two of these productions and God knows how many times his plays are staged around the world and that’s just on national theatre stages…so why has the anniversary of his death been marked with less than a whimper and barely a whisper.

Behan was a lion roaring in a wilderness, and now he can’t be heard? Pathetic.

April 5, 2014

Hitchcock, storyteller

The 39 Steps and The Lady Vanishes are the two most important formative films in the career of British born director, Alfred Hitchcock. That career spanned more than five decades.

Thematically, there is little difference between their narrative devices in the ‘30s and his later works. What changed is the technology and the history. The skeletal stories donned new clothes; technical innovations made new things possible like colour and sound.

Hitchcock stands at the epicenter of change and innovation not necessarily because he stood at the cutting edge but because he could tell a story better than any one else and for all those 50 plus years, the world of cinema has struggled to keep up.

Hitchcock’s career began in England in the 1920s and many of his earliest films were made without sound. He was a member of the British Film Society along with such literary luminaries as George Bernard Shaw and H.G. Wells; filmmaker Anthony Asquith and critics like Iris Barry and Ivor Montagu.

The BFI screened works of German Expressionist cinema such as FW Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) and Robert Wiene’s 1920 classic, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari as well as the works of Sergei Eisenstein and D.W. Griffith. This experience heavily influenced Hitchcock’s filmmaking style although he refrained from writing theoretical essays on film like his contemporaries. It might be said he practiced what they preached.

In fact, throughout his career, Hitchcock stood astride two distinctions in cinematic history by his own design. He craved and sought commercial success as a measure of his own achievements but he had an equal craving for the approval of his contemporaries and their acknowledgement of his role in the development of film as an art form.

The 39 Steps and The Lady Vanishes have many features in common. Both films were made prior to Hitchcock uprooting to Hollywood. Both films involve train journeys. Both films are based on novels, Ethel Lina white’s The Wheel Spins , (1936) and John Buchan’s ‘The 39 Steps’, (1915).

In The 39 Steps, the hero, Richard Hannay is an innocent man, wrongly accused of a murder, who goes on the run to expose the real criminals and prove his innocence.

In The Lady Vanishes, the protagonist is a woman who reports the mysterious disappearance of a travel companion only to find no-one believes her. The classic narrative of a wrongly accused innocent on the run became a recurring theme for Hitchcock (North by Northwest) or, as in The Lady Vanishes, the heroine’s sanity is in question (Suspicion). Both films were made in the 1930s against a backdrop of international unrest, particularly on mainland Europe.

John Buchan’s novel of The 39 Steps was written while he was recuperating from an illness in 1915. It plays with the prevalent fear of fifth columnists, spies and counter-spies. Hitchcock’s adaptation brings the film forward to the ‘30s against the backdrop of the rise of Hitler and the National Socialists in Germany and Mussolini’s Fascists in Italy. It is not inconceivable either that Hitchcock was indifferent to the prevalent philosophical teachings of his day.

The Frenchman, Henri Bergson wrote of how to live in ‘real time’, a person should and must grasp it intuitively. Such a notion would have found favour with a thoughtful cineaste as Hitchcock. As a filmmaker, he directed what his audience would intuit. Story telling was Hitchcock’s strength and he used every trick available to him to insure the story was told the way he wanted it perceived.

Although he once referred to his audience as ‘the moron millions’, Hitchcock had a conspiratorial pact with his audience. He made the suspense thriller the genre with which he was most closely identified and he employed and deployed his grab bag of tricks like a virtuoso violinist. In a Hitchcock film the audience are at once spectator and spied upon; hare and hound.

The 39 Steps begins in a place of entertainment, a music hall where Richard Hannay, an expatriate Canadian goes to while away some time in frivolous amusement. The star attraction is Mr Memory whose act lies in remembering facts with little notion of their meaning or import. Hitchcock lets the circumstances tell the story; we find out about Hannay because he asks Mr Memory the distance between Winnipeg and Montreal. But as the show progresses, the audience grow bored and restless; there’s jostling and a fight. Then two gun shots are fired. It is the first hint of the influence of the German Expressionists on Hitchcock; the jostling crowd, Mr Memory, the fight, the gunshots, askew camera angles.

Leaving the music hall, Hannay meets Annabella Smith who persuades him to take her home to his flat. There, she explains she fired the shots to scare off two heavies who were moving in on her. She tells him she is a spy for the British Government on the trail of a mysterious ringleader whose only distinguishing feature is a mutilated digit. In the morning her body is discovered by Hannay’s maid.

Smith is knifed to death, another Hitchcock favourite. But it is the maid’s scream that lavishes more of the classic Hitchcockian mode; first, it is a classic Expressionist ploy except in this case Hitchcock has deployed its impact in sound. The open mouthed scream of the maid segues neatly, dramatically and suspensefully into the train whistle to mark the fleeing Hannay’s departure to Scotland where he must find Ms Smith’s murderer to exonerate himself.

The 39 Steps in question are explained as some unspecified military secret that is vital to British security. But this becomes largely irrelevant to the narrative which deals with Hannay’s journey and particularly his efforts to persuade his reluctant travel companion, Pamela (Madeleine Carroll) of his innocence.

This is the classic ‘McGuffin’ of Hitchcock films, a ‘red herring’ introduced early in the narrative to help advance the plot but with little or no impact on its resolution. Thus the disappearance of Miss Froy in The Lady Vanishes appears to be the film’s raison d’etre but it proves to be just another narrative ploy, a McGuffin, against the enfolding of the film’s far more sinister purpose.

Hitchcock employs comedy in both films for light relief but, as a master storyteller, he’s well aware of the narrow divide between comedy and horror, the kind of suspenseful horror that keeps audiences on the edge of their seats. In the 39 Steps, he uses Mr Memory’s music hall performance and Hannay’s introduction to create his first moment of suspense using choppy editing, odd camera angles, glowering faces, ribaldry and boisterousness before he breaks the atmosphere abruptly with the gunshots.

In The Lady Vanishes, his most comic construct is the character double act of Caldecott and Charters, the pair of British gents on holiday, played by Naunton Wayne (Caldecott) and Basil Radford (Charters) whose sole obsession is getting home to see the England team play a test cricket series. Their employment proved so successful, the pair appeared in a total of ten films as the same characters, subsequently.

There is a deeper purpose to the comic characters in The Lady Vanishes. Hitchcock used contemporary socio-political concerns as a narrative vehicle in both films. The Lady Vanishes was made in 1938 when concern about developments in Europe were becoming more urgent. It was in the eve of Chamberlain’s so called Munich agreement. Caldicott and Charters make disparaging remarks about the country they are in – an obscure Tyrolean state – and the only ‘England’ they appear to be concerned about, is a cricket team.

Eric Todhunter, the pompous English barrister holidaying with his mistress, ‘Mrs’ Margaret Todhunter, is more concerned with keeping up appearances and not letting the world know his business than with the disappearance of an English governess. He is even more incredulous when confronted with gun wielding security in a secluded woods of a Tyrolean state. His death, delivered abruptly and without histrionics by Hitchcock, brings them all back to reality with a bang. It was clearly time to wake up and smell the coffee, or, in this case, the herbal tea favoured by Miss Froy.

The train journey serves a similar purpose in The 39 Steps. Hannay is Canadian, a traveler who has just returned from his work as a mining engineer in Africa. He visits a music hall and finds himself embroiled in a tangle of espionage and murder. When he takes the journey from London to Edinburgh, he begins his own journey of reawakening. The pace of the train ride reflects Hannay’s shift from a man reacting to events he hasn’t created into someone who regains his spontaneity and takes control of his own destiny. Gun wielding thugs can concentrate the mind but it is Hannay’s determination and drive to prove himself innocent against odds that appear to stack themselves higher against him with every plot twist, that is his real journey of self discovery and awakening.

Equally, his relationship with his unwilling travel companion (Madeleine Carroll) becomes the focus of his quest to prove his innocence. They remain handcuffed together for more than half the film – Hitchcock doesn’t resist the opportunity for a comic interlude here when they reach the crofter’s cottage and have to share a bed as ‘honeymooners’ – but in the film’s closing scene they walk away holding hands.

In The Lady Vanishes, Iris Henderson (Margaret Lockwood) is a London socialite on her way home to marry a man she doesn’t love. She meets with Gilbert Redman (Michael Redgrave), an English gentleman writing a history of the folk music of the country in which they’re traveling. Although their introduction is not a happy one, when she convinces him of the disappearance of Miss Froy and in their subsequent misadventures on the train, he changes from a gadabout to someone with purpose: a hero, in other words and someone with whom she could never resist falling in love. It has sometimes been argued that Hitchcock was never an innovator but someone who used the artillery available to him better than any one of his contemporaries.

For many others, even Hitchcock, The 39 Steps was ‘pure cinema’, a story told with pictures and sound in a craft and medium that was still in its formative years.

In The Lady Vanishes he uses all the dramatic, editing and cinematic tricks he would employ in his later work in Hollywood. Both films stand as classics of the Hitchcock oeuvre and, in their own right, both stand as classics of a genre – the suspense thriller – and would be used as style blueprints for films that followed.

March 18, 2014

The Detour (a short story)

(Hi, my name is Dermott Hayes and I’m new to WordPress. Two years ago I set off on a quest to be published. And I did it on my own. The first book I published was a collection of short stories. I sold it for the price of a cup of coffee but despite the world’s growing fondness for roasted beans, it never translated into massive book sales. Undeterred, at least I learned the mechanics of self publication. Anybody who’s willing to gamble knows their money is the only measure of their conviction. In my case, I believe it’s my words and my writing. So, here they are. I’m putting my words where my mouth is, so to speak. If you like them, you’ll respond.)

Oh God, pre-wedding jitters; sweaty palms, itchy scalp, soggy crotch. Better change my underwear, dab on some eau de toilette; careful, you don’t want to traipse up the aisle with a honk of tart’s handbag. I’d have a fag only I haven’t put the last one out yet. This will be right. You haven’t rushed into it. There’s been plenty of time to pause and reflect. And, if you’ve a mind for it, run.

Three years you’ve been together; three, blissfully happy, years. Was that a question? Or a statement? Trying to reassure myself.

Soul mates. They wear open toed sandals, eat brown rice and lentils and talk about ley lines and karma, don’t they? We had common interests in music and cooking even though we met in a noisy club. I remember that night so well. I didn’t want to be there that night. Or any night. I was clubbed out, back then. Christ, it’s corny, tiny hairs rising on my neck with the memory. Jeez, our eyes met across a crowded room. Three years on and we’re laughing about that, still. We couldn’t hear each other talking so left for a quiet coffee shop where we sat and drank cappucino and espresso, nibbled almond biscotti and then a bottle of the Sicilian nero d’avola – since, our favourite wine – and talked and talked and talked. What a Gobshite. A grandparent, closer to 60 than fifty, walking up the aisle, like a giddy virgin? Am I mad? Is it the loneliness? We walk, we talk; we go to the pictures and the theatre shows. We dine out for a treat when we have the money. We have our garden. But where’s the passion? Would you listen to me? Passion, at my age? We took it slowly, knowing, ironically, time was not on our side. But at our age there’s plenty of baggage.

My first marriage fell apart. We were in love. I’m pretty certain of that. I think. There’s no way to be sure, y’see. All that shite about preparing you for marriage, well, it’s all bollix, isn’t it? The fact is, you’re first love is about nature, isn’t it? Or is it? I mean, we were taught to find someone to make a home and raise a family with. And in marriage, of course. It became a war. Surrounded by an ever rising wall of interest rates, unemployment and soiled nappies, we imploded. We fell out over curtains in the end.

Well, things have changed since then.

Honking car horn, a ringing doorbell, a clenched fist beating the door. Christ, they’re here already. Have I everything? I scanned the room, stopped at the portraits of my beautiful daughters and grandsons. I’ve put them through so much. Am I such a selfish bastard, I’ll put them through it again? Do they know what love is? Do they know they’ll lose the love they began with and have to discover new ways to love within what they’ve built already? They saw and heard us fighting. What sort of start was that? What sort of nurture was that?

Life takes us down some strange paths. Perhaps that’s what my first marriage was, just a detour. But where does that put my children? If I’d ignored that detour, they wouldn’t be here. That’s the long and the short of it.

I slammed the door of the taxi shut, louder and harder than I intended. ‘Sorry,’ I said to the taxi driver. He waved my apology away. ‘It’s the nerves, is it?’ Oh great. A philosopher. ‘Do you know where you’re going?’ ‘Don’t worry. I’ll get you there on time.’

My phone rang and I answered, welcoming the intrusion.

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I’m in a taxi. I’ll be there in five minutes.’

Right, I’m here. And so’s everyone else. Even the ex-wife.

‘You can run, if ye want but it’s now or never, bud.’ Jean Paul Sartre and Elvis, on another day I’d love it. I handed him 10 Euro, waving the change away. It’s only two Euro, the mouthy bollix.

‘You’re late,’ someone said.

‘You’re up next,’ someone else said.

I was rushed through the front hall crowded with families and friends, the gathered support groups. I don’t know, I thought in terror. The Registrar speaks. Her lips move. I strain to hear.

‘Do you John, take James, to be your lawfully wedded partner?’

March 17, 2014

When is truth, fiction and fiction, truth?

I believe, as a writer of fiction, that whatever I write, regardless of how close an account it is to a real event, it remains, for all intents and purposes, fiction.

Now that’s a very broad and some might argue, indefensible statement. How can the reader discern the fact from the fiction, for example?

There is a contradiction inherent in all fiction writing.

One one hand, the novice writer is encouraged to stick to what they know and are passionate about and then, write about that or, at least, draw their inspiration from that well.

On the other hand, a writer must never get too close or emotional to their own writing since their task, and duty, to the reader, is to help them suspend their disbelief and doubt and find their own ‘truth’ in the fiction they’re reading.

Fiction, the noun, according to most dictionaries, is ‘literature in the form of prose, especially novels or short stories, that describes imaginary events and people.’ Such a definition might exclude the ‘fictional’ works of half the world’s greatest writers, I think.

Few can doubt the fictional nature of Kurt Vonnegut Jr’s Slaughterhouse Five, surely, since it relates a story of alien abduction and an alien race called The Tralfamadorians.

At the same time, the hero of the story, Billy Pilgrim, is a young American soldier who, like Vonnegut, survives the bombing of Dresden because he was working, as a POW, in an underground meat locker. Pilgrim, however, unlike the author, begins to experience life out of sequence, frequently revisiting scenes. He also meets the Tralfamadorians along the way.

Could James Joyce have conjured Leopold Bloom from his imagination or any of the other central and incidental characters who populate Ulysses or his book of short stories, Dubliners, had he not been an inhabitant and keen observer of the denizens of his own native city?

I think not and I’m sure there are characters in many novels who may cause some disquiet in the lives of real people and acquaintances of the authors.

James Lee Burke, one of my all time favourite authors, frequently draws his characters from his personal experience.

Burke is a multi-award winning writer of crime mysteries, best known for his novels involving Dave Robicheaux, some time deputy sheriff of New Iberia parish in Louisiana, full time recovering alcoholic and former NOPD homicide detective. He’s also written a series involving first, Hackberry Holland, recovering alcoholic and former Congressional candidate, Texas Ranger and public defender turned sheriff of a small, dusty town on the rim of the Tex-Mex border and then his brother, Billy Bob Holland, a public defender and environmental champion, transplanted from Texas to Montana.

He’s also published a number of historical novels set in the American civil war and all written from a Confederate army perspective.

His observations are panoramic and insightful, always erudite and frequently painful in their honesty. Just what you’d expect from a man with an alcoholic and academic past who has worked as a teacher, a journalist, an oil worker and among down and outs in Los Angeles’ skid row and who grew up in Louisiana and now lives in Montana.

Read the Introduction to ‘The Convict and Other Stories.’ It’s called Jailhouses, English Departments and Electric Chairs. It is a revelation for any aspiring writer that nothing is guaranteed or written in stone, except the writer’s own unquenchable thirst to write.

‘Jolie Blon’s Bounce’, one of Burke’s most highly acclaimed and successful novels in the Dave Robicheaux series, was turned down more than 100 times before it finally found a publisher.

I spent more than twenty years working as a journalist when the essential imperative, both legal and moral, was to ensure, as far as we could,

what we wrote was factual and truthful.

An author has a different objective. It may be their intention to inform; they may desire to entertain but, in my estimation, their real task is to alter the reader’s point of view. I don’t mean ‘opinion’; I mean, literally, point of view.

If a writer can give the reader the facility to see something from the point of view of a different person, of another age, another race, even another gender; then they’ve suspended their disbelief and achieved their own goal.

A popular novelist once told me a very personal story about himself that, while not doing anything wrong, made him look, well, gullible and human and not the worldly wise author of crime fiction he was.

He was aware of my role as a journalist but he gave me the story. There was drink taken, I must admit, but the story subsequently appeared in a newspaper. The author was appalled and, frankly, outraged. He never denied it nor did he seek legal redress, as one might expect he would.

Instead, a character appeared in one of his subsequent novels, bearing my name, complete with two ‘ts’. That character was a dog, a friendly, if rather dozy golden retriever, if memory serves and its owner bore the name of the third person who witnessed my conversation with the author and his revelations.

What you write becomes fiction when you set it in print, if that is your intent and design. It is the reader who must decide if it’s worth reading.

A writer will find inspiration anywhere. They have to look and see, that’s all. Then they have to write.

August 16, 2013

The Lark in the Morning...memories of The Bothy Band

The first time I saw Planxty was in the National Stadium in the early '70s when they played support to Donovan. The first time I saw The Bothy Band was at as lunchtime show in Lecture theatre 'L' in the Arts building in UCD, Belfield. Although there could be no greater contrast in venue; the charged atmosphere of anticipation surrounding the return of a '60s icon like Donovan in the National Stadium on a hot summer evening and the lunchtime lethargy of academia and bored students, vaguely curious to hear a band born from the ashes of a legend, Planxty, that support act from the National Stadium. I'm not even sure if the name 'Planxty' had been coined before that night in the National Stadium in 1972. To those who knew of him, Christy Moore was the most recognizable figure among the support crew on stage that night, the others were Donal Lunny, Liam Og O'Flynn and Andy Irvine. They only played a handful of tracks, including the Raggle Taggle Gypsy which was to become one of their signature tracks. I went to the show with my brother and he had bought a copy of Prosperous, a 'solo' album recorded by Christy Moore with the same personnel in an old house in his Kildare hometown and, if that album was to be the template for future Planxty albums, that first performance in the National Stadium stamped their authority and presence in the public mind.Significantly too, Irvine was a former member of Sweeney's Men, an earlier, trailblazing Irish band, cut from the same cloth. Sweeney's Men was a ballad group in the style of The Dubliners and The Clancy Brothers but they derived inspiration and style from further afield that Irish balladry and explored multi-instrumental and non-ballad arrangements that set them apart. Similarly, Donal Lunny had cut his teeth in the folk world with Emmet Spiceland and both he and Moore were boyhood friends. It was Lunny who taught Moore to play guitar and bodhran.Christy Moore carved out a name for himself on the English folk club scene in the '60s. He hung up his tie and left his bank job during a bank strike and never looked back. With only his guitar and a suitcase, he took the boat to England and cut out a new life and career for himself as a ballad singer. Moore met up with his old pal, Donal Lunny and they brought Andy Irvine and Liam Og O'Flynn together to record Moore's second solo album, Prosperous for what was to become the future blueprint for Planxty. When Donal Lunny left Planxty in 1973, Dubliner Johnny Moynihan joined the band. Moynihan was another former member of Sweeney's Men and is often credited with introducing the six string bouzouki to Irish folk music. Liam Og O'Flynn, the fourth member of the original quartet, was a well known solo instrumentalist who had learned his trade at the hands of Seamus Ennis, widely regarded as one of the finest proponents of the uileann pipes, past or present. O'Flynn's distinctive style set Planxty apart and his instrumental tracks, influenced to a large degree by the arrangements of Sean O'Riada, often made up the b-sides of their first single releases. It was those instrumental leanings that prompted the formation of The Bothy Band by Donal Lunny. The original line up included Paddy Glackin on fiddle, Paddy Keenan on pipes, Matt Molloy on flute, Tony McMahon on button accordion and the brother and sister team of Michael O'Domhnaill and Triona Ni Dhomhnaill. Tony McMahon left to become a producer with BBC and Paddy Glackin was replaced by Donegal fiddler, Tommy Peoples for the band's first album, '1975'. Two more studio albums followed and further personnel changes, most notably, Sligo fiddler, Kevin Burke whose inimitable style became a signature sound. I first heard Kevin Burke play on two tracks of an album by Arlo Guthrie (son of Woody Guthrie) - Last of the Brooklyn Cowboys, 'Farrell O'Gara' and 'Sailor's Bonnet'. The O'Domhnaills, Michael and Triona, had played together along with their other sister, Maighread in a group called Skara Brae that had often supported Planxty on their tours. They had a wealth of songs they'd learned from a blind, maiden aunt while Michael was an accomplished guitarist and Triona played Clavinet and harpsichord. There had to be artistic tensions, the fountain of creativity but these, one can only speculate might have been based on more than just musical direction. Planxty and The Bothy Band emerged at a time in Irish history when that Irish cultural identity appeared to have a greater urgency than ever before. In my youth, we listened to The Walton Show on radio when we were admonished/advised that if we felt like singing a song, 'do sing an Irish song' and, ironically, one of that show's most requested songs was Katie Daly, an American folk song. Planxty, in particular, emerged in the days of internment in Northern Ireland and later, Bloody Sunday, when one of the most popular songs was 'The Men Behind the Wire'. In 1972 John Lennon performed 'The Luck of the Irish', a damning attack on British imperialism's impact on its neighbour and just a year later, Paul McCartney was singing, 'Give Ireland Back to the Irish.' Planxty's songs were noticeably non-political as though they'd made a collective decision to avoid acknowledgement of the very historic events happening on their doorstep that some argued, were the lifeblood of 'folk' music. It's a dilemma, I imagine, that concentrated the mind of Christy Moore in particular and may have prompted or at least, influenced his return to solo work. Indeed, Moore released an album of songs later, that was sold outside the GPO and whose proceeds went to dependents of interned Republicans. Whatever the circumstances, Planxty and The Bothy Band gave a new generation an introduction to an indigenous culture they could embrace without political baggage. Of course, there was the other tension, the musical disapproval of their syncopated arrangements led by the so called and self styled 'purists' who tut tutted and 'ciunas'd' their way through every gathering of musicians as though it was their own private club that brooked no changed or embraced any novelty or innovation. For five years in the '70s I followed these bands and their music and they prompted me to delve deeper into the roots of the tradition that was the core of my own interests but simply hovered like a ghost or an itch I couldn't scratch. Their own leanings drove me to explore music from further afield such as American and British folk, European and African folk and what has, since then, become more fashionably known as 'world music.' But no study or studious collecting could replace the blood soaring excitement of standing in a sweaty marquee in Ballisodare and listening to The Bothy Band let loose with Rip the Calico or that medley of reels, The Salamanca,The Banshee and The Sailor's Bonnet.

The first time I saw Planxty was in the National Stadium in the early '70s when they played support to Donovan. The first time I saw The Bothy Band was at as lunchtime show in Lecture theatre 'L' in the Arts building in UCD, Belfield. Although there could be no greater contrast in venue; the charged atmosphere of anticipation surrounding the return of a '60s icon like Donovan in the National Stadium on a hot summer evening and the lunchtime lethargy of academia and bored students, vaguely curious to hear a band born from the ashes of a legend, Planxty, that support act from the National Stadium. I'm not even sure if the name 'Planxty' had been coined before that night in the National Stadium in 1972. To those who knew of him, Christy Moore was the most recognizable figure among the support crew on stage that night, the others were Donal Lunny, Liam Og O'Flynn and Andy Irvine. They only played a handful of tracks, including the Raggle Taggle Gypsy which was to become one of their signature tracks. I went to the show with my brother and he had bought a copy of Prosperous, a 'solo' album recorded by Christy Moore with the same personnel in an old house in his Kildare hometown and, if that album was to be the template for future Planxty albums, that first performance in the National Stadium stamped their authority and presence in the public mind.Significantly too, Irvine was a former member of Sweeney's Men, an earlier, trailblazing Irish band, cut from the same cloth. Sweeney's Men was a ballad group in the style of The Dubliners and The Clancy Brothers but they derived inspiration and style from further afield that Irish balladry and explored multi-instrumental and non-ballad arrangements that set them apart. Similarly, Donal Lunny had cut his teeth in the folk world with Emmet Spiceland and both he and Moore were boyhood friends. It was Lunny who taught Moore to play guitar and bodhran.Christy Moore carved out a name for himself on the English folk club scene in the '60s. He hung up his tie and left his bank job during a bank strike and never looked back. With only his guitar and a suitcase, he took the boat to England and cut out a new life and career for himself as a ballad singer. Moore met up with his old pal, Donal Lunny and they brought Andy Irvine and Liam Og O'Flynn together to record Moore's second solo album, Prosperous for what was to become the future blueprint for Planxty. When Donal Lunny left Planxty in 1973, Dubliner Johnny Moynihan joined the band. Moynihan was another former member of Sweeney's Men and is often credited with introducing the six string bouzouki to Irish folk music. Liam Og O'Flynn, the fourth member of the original quartet, was a well known solo instrumentalist who had learned his trade at the hands of Seamus Ennis, widely regarded as one of the finest proponents of the uileann pipes, past or present. O'Flynn's distinctive style set Planxty apart and his instrumental tracks, influenced to a large degree by the arrangements of Sean O'Riada, often made up the b-sides of their first single releases. It was those instrumental leanings that prompted the formation of The Bothy Band by Donal Lunny. The original line up included Paddy Glackin on fiddle, Paddy Keenan on pipes, Matt Molloy on flute, Tony McMahon on button accordion and the brother and sister team of Michael O'Domhnaill and Triona Ni Dhomhnaill. Tony McMahon left to become a producer with BBC and Paddy Glackin was replaced by Donegal fiddler, Tommy Peoples for the band's first album, '1975'. Two more studio albums followed and further personnel changes, most notably, Sligo fiddler, Kevin Burke whose inimitable style became a signature sound. I first heard Kevin Burke play on two tracks of an album by Arlo Guthrie (son of Woody Guthrie) - Last of the Brooklyn Cowboys, 'Farrell O'Gara' and 'Sailor's Bonnet'. The O'Domhnaills, Michael and Triona, had played together along with their other sister, Maighread in a group called Skara Brae that had often supported Planxty on their tours. They had a wealth of songs they'd learned from a blind, maiden aunt while Michael was an accomplished guitarist and Triona played Clavinet and harpsichord. There had to be artistic tensions, the fountain of creativity but these, one can only speculate might have been based on more than just musical direction. Planxty and The Bothy Band emerged at a time in Irish history when that Irish cultural identity appeared to have a greater urgency than ever before. In my youth, we listened to The Walton Show on radio when we were admonished/advised that if we felt like singing a song, 'do sing an Irish song' and, ironically, one of that show's most requested songs was Katie Daly, an American folk song. Planxty, in particular, emerged in the days of internment in Northern Ireland and later, Bloody Sunday, when one of the most popular songs was 'The Men Behind the Wire'. In 1972 John Lennon performed 'The Luck of the Irish', a damning attack on British imperialism's impact on its neighbour and just a year later, Paul McCartney was singing, 'Give Ireland Back to the Irish.' Planxty's songs were noticeably non-political as though they'd made a collective decision to avoid acknowledgement of the very historic events happening on their doorstep that some argued, were the lifeblood of 'folk' music. It's a dilemma, I imagine, that concentrated the mind of Christy Moore in particular and may have prompted or at least, influenced his return to solo work. Indeed, Moore released an album of songs later, that was sold outside the GPO and whose proceeds went to dependents of interned Republicans. Whatever the circumstances, Planxty and The Bothy Band gave a new generation an introduction to an indigenous culture they could embrace without political baggage. Of course, there was the other tension, the musical disapproval of their syncopated arrangements led by the so called and self styled 'purists' who tut tutted and 'ciunas'd' their way through every gathering of musicians as though it was their own private club that brooked no changed or embraced any novelty or innovation. For five years in the '70s I followed these bands and their music and they prompted me to delve deeper into the roots of the tradition that was the core of my own interests but simply hovered like a ghost or an itch I couldn't scratch. Their own leanings drove me to explore music from further afield such as American and British folk, European and African folk and what has, since then, become more fashionably known as 'world music.' But no study or studious collecting could replace the blood soaring excitement of standing in a sweaty marquee in Ballisodare and listening to The Bothy Band let loose with Rip the Calico or that medley of reels, The Salamanca,The Banshee and The Sailor's Bonnet.

Postcard from a Pigeon

- Dermott Hayes's profile

- 4 followers