Linda Collison's Blog, page 12

January 10, 2016

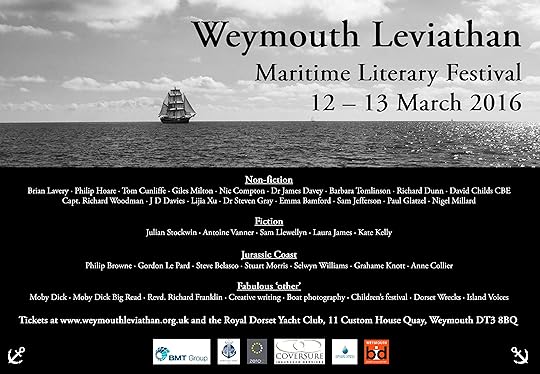

Weymouth’s First Maritime Literary Festival March 12-13 2016

I’m looking forward to attending England’s first maritime literary festival and meeting up with many of my nautical writer friends and acquaintances, and hopefully making new ones. Organized by James Farquharson, the event will be taking place the weekend of March 12-13, 2016 at The Royal Dorset Yacht Club and several other venues in Weymouth.

The festival includes 37 official events organized by James Farquarson, which are predominantly lectures given by well-known maritime historians David Childs, Anne Collier, Dr. James Davy, J.D. Davies, Richard Dunn, Dr. Steven Gray, Brian Lavery, and Barbara Tomlinson, maritime archaeologist Gordon LePard and wreck divers Graham Knott and Selwyn Williams, photographers Steve Belasco and Nigel Millard, sailing gold medalist Lijia Xu — and a significant number of well-known and emerging nautical novelists, autobiographers and nonfiction writers, including the ever popular Julian Stockwin and Old Salt Press author Antoine Vanner.

Nine of the presenters are women. They are Emma Banford (newspaper and magazine editor; sailor), Lizzie Church (Regency novelist), Fiona Clark Echlin (author, poet, playwright and academic), Anne Collier (historian and author), Angela Cockayne (artist), Laura James (author) and Kate Kelly (author and scientist), Barbara Tomlinson (author and Curator Emeritus, Natl. Maritime Museum), and Lijia Xu (gold medalist sailor and author).

For a complete list of speakers and events (which include a maritime church service and a Moby Dick Big Read, artistic exhibit, and showing of the movie) see the official programme.

The events, held over the course of two days, are sold a la carte. I have so far bought tickets to three events and will surely add others.

A festival such as this is a great opportunity for writers to learn from each other and support maritime literature. We’re connected by the sea, both physically and thematically. This coming together is important to share ideas and inspirations. Gatherings also presents networking opportunities for writers. A dozen or so of us will be meeting informally throughout the weekend to discuss topics such as writing process, publishing opportunities and marketing strategies. What better place than an old port town to have a maritime literary festival? Yes, there will be a pub crawl!

For more information and to purchase tickets in advance please visit Weymouth Leviathan Maritime Literary Festival website.

See you there?

December 7, 2015

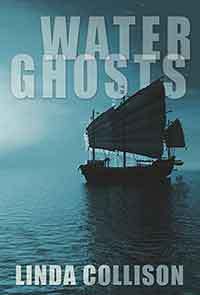

Water Ghosts — the terror of the doldrums

dol-drums

1. a state of inactivity or stagnation, as in business or art

2. the doldrums, a. a belt of calms and light baffling winds north of the equator between the northern and southern trade winds in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

3. a dull, listless, depressed mood; low spirits

Syn. depression, gloom, melancholy, dejection

— Webster’s New Universal Unabridged Dictionary

Adrift at sea, it’s not at all what I imagined.

The literal doldrums, more scientifically called the Inter-tropical Convergence Zone, is a shifting, unpredictable belt of low pressure on either side of the equator where the trade winds of the Northern and Southern Hemispheres come together. It is a pattern observed in the great bodies of water, the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, and well worth studying more, particularly if you’re a meteorologist, an oceanographer — or a sailor. Bob and I first encountered this strange, unsettled seascape when we sailed our Luders 36′, Cheoy Lee-built sailboat, from Hawaii to Tahiti, a voyage that took us twenty-one days.

Before I encountered them first hand, I imagined the doldrums to be a pleasant, placid stretch of benign water — a welcoming place, offering a respite from our relentless windward journey as we struggled to make our easting. If the winds died for a few days, I figured it would give me a chance to wash some of our sweaty, salty clothes in a bucket of fresh water on deck, and hang them on the lifelines to dry. At rest on the deep calms might give us an opportunity to slip overboard for a refreshing bathe in the tepid water– not to mention a little sunbathing on the foredeck — an activity all the glossy sailing magazines promised as part of a tropical cruise.

Since leaving Hawaii we had been beating hard into steady, strong easterlies for eight or nine days, climbing up and plunging down sparkling blue hills of water, eight to ten feet high. Sunny skies, puffy white clouds on the horizon — it was glorious sailing weather!

But there was nothing gentle about it. Beating into those seas was physically demanding. Bob and I took our turns at the helm, watch and watch, wearing our safety harnesses and strapped to the lifeline. It was at once exhilarating, yet exhausting.

Down below, cooking presented its own challenges. I strapped myself in, took a wide stance in front of the two-burner alcohol stove swinging madly on gimbals, and prepared for the juggling act that inevitably followed. Each time the boat crashed down the back side of a roller, knives and wooden spoons became airborne and supper would lift itself up out of the pot. Simply advancing the five steps from the companionway to the v-berth at the bow was a feat requiring all four extremities. Handholds were a must as I lumbered and lurched across the swaying deck. And this was good weather, I marveled! What would a storm at sea be like?

We entered the ITCZ — the doldrums — rather suddenly. One day the wind dropped and the next day it gasped its last breath and we were dead in the water, about six degrees north. But the water in that fabled place wasn’t flat like a lake, like I imagined it would be if the wind wasn’t blowing. Energy was still surging through the ocean, rocking our boat violently from side to side, but without the wind we were going nowhere — except possibly westward, on the North Equatorial Current. The sun disappeared and soggy, sullen gray clouds soon enveloped us. The sails slatted and banged with each wave of energy that passed beneath us — through us — shaking the boat and the boom, rattling our teeth and our nerves. Below — books, dishes, and anything not securely — stowed flew across the cabin, as if flung by an angry poltergeist. To keep the rigging from being damaged we sheeted the boom in to its cradle and dropped the sails, lashed the wheel and went below, wedging ourselves in the v-berth amidst the spare sails to keep from being tossed about ourselves. The seasickness we had overcome a few days into the passage, came back to haunt us. We were in our own particular hell.

This is when the idea of water ghosts crept into my imagination. The rocking and shaking felt like malevolent forces were intent on destroying us. Now that we weren’t moving, I experienced intense claustrophobia, trapped in a small boat in the middle of the ocean, many days away from the nearest island. I drugged myself with a double dose of Dramamine and tried to sleep.

There was no thought of bathing in the ocean — the boat was rocking so hard as to make getting back on board hazardous. Not to mention the fear of sharks. On the return voyage, when passing through the doldrums, something struck our rudder (a shark? a whale? floating debris?) and Bob had to go overboard, dive down and inspect it for damage. He tied a dock line around his waist, the other end to the stanchion, donned mask and fins and dropped over the side. Fortunately, the rudder was intact — but once again I struggled with a mounting panic as I stood on the bobbing deck, feeling trapped being aboard a small floating object in the midst of a vast, unpredictable ocean, going nowhere. Oh, and did I mention it was insufferably hot and humid?

Rain squalls! The one blessing the doldrums shower upon you is fresh water. Frequent yet unpredictable little downpours, complete with their own little weather patterns, which usually involved strong but short-lived winds. A chance to raise the sails and make some progress. A chance to get out the shampoo, strip down and shower on deck. We had no water maker on that passage (and water makers take power, which requires carrying more fuel which is impractical on a small sailboat). Although we carried 120 gallons of fresh water in our tanks — and several cases of bottled water — we always took advantage of fresh water from the heavens. Cruising sailors are thrifty by necessity.

Why not turn on the engine and motor out of the doldrums, you might wonder? Being a small sailing vessel, we carried a limited amount of diesel fuel and could not afford to waste it, just to make way. Like sailors of centuries past, we had to be patient and wait for the wind. Before the advent of steam, sailing ships driven around the world by the powerful trades were often “caught” in the doldrums for days or weeks on end, until they drifted north or south enough to pick up the reliable trades again — or the invisible zone’s ever-changing boundaries shifted and steady breezes graced them once again.

“What was that?” I murmured to Bob, coming out of my drug-induced sleep. The boat wasn’t shaking so much. There was a soughing sound in the rigging as if the ocean was breathing again, in fits, starts, and listless sighs.

“Wind,” he said.

We pulled ourselves out of our steaming hot bunks, staggered up on deck to roll out the jib, only to be disappointed. But we kept at it, each huff, each luff, we ghosted along the confused waters as far as that breath would take us. By nightfall the breeze was steady enough to raise the mainsail and we were back on course, making two or three knots. The skies cleared and new stars appeared to guide us on our journey south, toward landfall.

That brings me to the other connotations of the word doldrums: A period of inactivity or stagnation in business or art. a dull, listless, depressed mood; low spirits.

Writers — know that encountering the doldrums is part of the creative process, part of the process of living. If you find yourself stuck, uninspired, depressed, or afraid, don’t abandon ship. Instead, examine the deep waters beneath you, supporting you, surrounding you. Explore the deep dark waters of your subconscious mind. Feel the greater Energy that breathes Life into your valiant body, still afloat, and somewhere aboard that floating home, your Soul. Sit down and write what surfaces. Write your way through these difficult, sometimes terrifying times.

Water Ghosts is now an audio book, narrated by Aaron Landon and produced by Dennis Kao, from Audible.com.

The terror of the doldrums

dol-drums

1. a state of inactivity or stagnation, as in business or art

2. the doldrums, a. a belt of calms and light baffling winds north of the equator between the northern and southern trade winds in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

3. a dull, listless, depressed mood; low spirits

Syn. depression, gloom, melancholy, dejection

— Webster’s New Universal Unabridged Dictionary

Adrift at sea, it’s not at all what I imagined.

The literal doldrums, more scientifically called the Inter-tropical Convergence Zone, is a shifting, unpredictable belt of low pressure on either side of the equator where the trade winds of the Northern and Southern Hemispheres come together. It is a pattern observed in the great bodies of water, the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, and well worth studying more, particularly if you’re a meteorologist, an oceanographer — or a sailor. Bob and I first encountered this strange, unsettled seascape when we sailed our Luders 36′, Cheoy Lee-built sailboat, from Hawaii to Tahiti, a voyage that took us twenty-one days.

Before I encountered them first hand, I imagined the doldrums to be a pleasant, placid stretch of benign water — a welcoming place, offering a respite from our relentless windward journey as we struggled to make our easting. If the winds died for a few days, I figured it would give me a chance to wash some of our sweaty, salty clothes in a bucket of fresh water on deck, and hang them on the lifelines to dry. At rest on the deep calms might give us an opportunity to slip overboard for a refreshing bathe in the tepid water– not to mention a little sunbathing on the foredeck — an activity all the glossy sailing magazines promised as part of a tropical cruise.

Since leaving Hawaii we had been beating hard into steady, strong easterlies for eight or nine days, climbing up and plunging down sparkling blue hills of water, eight to ten feet high. Sunny skies, puffy white clouds on the horizon — it was glorious sailing weather!

But there was nothing gentle about it. Beating into those seas was physically demanding. Bob and I took our turns at the helm, watch and watch, wearing our safety harnesses and strapped to the lifeline. It was at once exhilarating, yet exhausting.

Down below, cooking presented its own challenges. I strapped myself in, took a wide stance in front of the two-burner alcohol stove swinging madly on gimbals, and prepared for the juggling act that inevitably followed. Each time the boat crashed down the back side of a roller, knives and wooden spoons became airborne and supper would lift itself up out of the pot. Simply advancing the five steps from the companionway to the v-berth at the bow was a feat requiring all four extremities. Handholds were a must as I lumbered and lurched across the swaying deck. And this was good weather, I marveled! What would a storm at sea be like?

We entered the ITCZ — the doldrums — rather suddenly. One day the wind dropped and the next day it gasped its last breath and we were dead in the water, about six degrees north. But the water in that fabled place wasn’t flat like a lake, like I imagined it would be if the wind wasn’t blowing. Energy was still surging through the ocean, rocking our boat violently from side to side, but without the wind we were going nowhere — except possibly westward, on the North Equatorial Current. The sun disappeared and soggy, sullen gray clouds soon enveloped us. The sails slatted and banged with each wave of energy that passed beneath us — through us — shaking the boat and the boom, rattling our teeth and our nerves. Below — books, dishes, and anything not securely — stowed flew across the cabin, as if flung by an angry poltergeist. To keep the rigging from being damaged we sheeted the boom in to its cradle and dropped the sails, lashed the wheel and went below, wedging ourselves in the v-berth amidst the spare sails to keep from being tossed about ourselves. The seasickness we had overcome a few days into the passage, came back to haunt us. We were in our own particular hell.

This is when the idea of water ghosts crept into my imagination. The rocking and shaking felt like malevolent forces were intent on destroying us. Now that we weren’t moving, I experienced intense claustrophobia, trapped in a small boat in the middle of the ocean, many days away from the nearest island. I drugged myself with a double dose of Dramamine and tried to sleep.

There was no thought of bathing in the ocean — the boat was rocking so hard as to make getting back on board hazardous. Not to mention the fear of sharks. On the return voyage, when passing through the doldrums, something struck our rudder (a shark? a whale? floating debris?) and Bob had to go overboard, dive down and inspect it for damage. He tied a dock line around his waist, the other end to the stanchion, donned mask and fins and dropped over the side. Fortunately, the rudder was intact — but once again I struggled with a mounting panic as I stood on the bobbing deck, feeling trapped being aboard a small floating object in the midst of a vast, unpredictable ocean, going nowhere. Oh, and did I mention it was insufferably hot and humid?

Rain squalls! The one blessing the doldrums shower upon you is fresh water. Frequent yet unpredictable little downpours, complete with their own little weather patterns, which usually involved strong but short-lived winds. A chance to raise the sails and make some progress. A chance to get out the shampoo, strip down and shower on deck. We had no water maker on that passage (and water makers take power, which requires carrying more fuel which is impractical on a small sailboat). Although we carried 120 gallons of fresh water in our tanks — and several cases of bottled water — we always took advantage of fresh water from the heavens. Cruising sailors are thrifty by necessity.

Why not turn on the engine and motor out of the doldrums, you might wonder? Being a small sailing vessel, we carried a limited amount of diesel fuel and could not afford to waste it, just to make way. Like sailors of centuries past, we had to be patient and wait for the wind. Before the advent of steam, sailing ships driven around the world by the powerful trades were often “caught” in the doldrums for days or weeks on end, until they drifted north or south enough to pick up the reliable trades again — or the invisible zone’s ever-changing boundaries shifted and steady breezes graced them once again.

“What was that?” I murmured to Bob, coming out of my drug-induced sleep. The boat wasn’t shaking so much. There was a soughing sound in the rigging as if the ocean was breathing again, in fits, starts, and listless sighs.

“Wind,” he said.

We pulled ourselves out of our steaming hot bunks, staggered up on deck to roll out the jib, only to be disappointed. But we kept at it, each huff, each luff, we ghosted along the confused waters as far as that breath would take us. By nightfall the breeze was steady enough to raise the mainsail and we were back on course, making two or three knots. The skies cleared and new stars appeared to guide us on our journey south, toward landfall.

That brings me to the other connotations of the word doldrums: A period of inactivity or stagnation in business or art. a dull, listless, depressed mood; low spirits.

Writers — know that encountering the doldrums is part of the creative process, part of the process of living. If you find yourself stuck, uninspired, depressed, or afraid, don’t abandon ship. Instead, examine the deep waters beneath you, supporting you, surrounding you. Explore the deep dark waters of your subconscious mind. Feel the greater Energy that breathes Life into your valiant body, still afloat, and somewhere aboard that floating home, your Soul. Sit down and write what surfaces. Write your way through these difficult, sometimes terrifying times.

Water Ghosts is now an audio book, narrated by Aaron Landon and produced by Dennis Kao, from Audible.com.

November 18, 2015

Novel writing: Finishing the first draft

Welcome to the art of novel writing. How many of us have a good idea for a novel?

Hands shoot up all over the room, waving with excitement.

How many of us have actually started the novel?

A few hands wither and sink out of sight.

Now, how many have actually finished writing their novel?

Arms drop like trees under a logger’s chain saw. Only a few remain standing.

Why? What’s keeping you from finishing?

“I lost interest.”

“I ran out of ideas.”

“I have writer’s block.”

“I lost the thread of the story.”

“It sucks.”

I’ll bet there isn’t a writer, living or dead, who has finished every novel he or she began. Starting novels and abandoning them is nothing to be ashamed of; it’s part of the writing process. Sometimes we’re just trying out ideas. Practicing. Playing with characters and situations. The way a visual artist doodles and sketches. The way a musician plays scales and riffs. The difference, I suppose, is that most writers who start out to write a novel, don’t believe they’re practicing or doing exercises. They often start, headlong and driven by the creative pressure, the so-called muse, to write a meaningful story –but eventually flounder and come to a halt. And unlike a sketch or a practice session, we don’t feel our story has value unless we complete it. I’m not even talking about publishing at this point; I’m just talking about finishing the story.

When is a story finished? Is it finished the day it’s officially published? The first time it’s read by someone? When you complete your final edit and hit “send?” When you finish the raw and ragged first draft?

Some say a story is never finished, and I happen to believe that. As a writer I finally decide on one iteration, then move on to the next story.

But for me, the story quickens, it springs to life when I’ve captured the heart of the thing. The manuscript is still rough, in fact, it’s hideous in places, but it has a heart and a soul.

But how do you complete your story, that half-formed lump of clay in your hands? How do you get beyond the great wasteland of the middle, when all of a sudden you don’t know where you are or what you were trying to express? This is often the point where you feel your writing has no merit and your story is a sham. What to do?

First of all, believe me when I tell you your story has value. Without even reading it, I know it has potential. Maybe it needs a heart, or maybe it needs muscle and bones. It almost certainly needs direction.

Many writers shun outlines; they don’t want to feel constrained by them. Outlines feel imposed and artificial. If intuitive writing is working for you, then keep at it. But if you lose your way, you might want to make a map to help you reach your destination. A map is something like an outline; it helps you find your way, and hopefully finish your story.

If you haven’t done it already, try writing the end of your story before you tackle the great middle. It’s not written in stone; you might decide to change it completely. But at some point during the writing process, an ending will come to you that feels so right. This ending gives you guidance because now you know where you’re headed.

If you’re stuck in the middle of your story even though you know your ending, you might need to throw some obstacles at your characters. Don’t make it easy for them (or you.) What’s the worst that could happen to your protagonist? Throw it at him or her –then write your way out of it. Trust your inner voice. Trust your characters to work it out.

The other thing to think about is the theme of your novel. I like non-genre, literary stories, rich in theme. But even highly formulaic stories have themes. Themes are what your story is really about, beyond the plot. The bigger picture, the deeper meaning, the take-home message. Theme and character development drive the plot.

If that doesn’t work, or if your book isn’t very much about plot, develop your characters through thoughts, actions and memories. Do some free writing. Open a new file on your computer, or a new notebook, and start writing about one of the supporting characters. See where it leads you.

Set a deadline to finish the rough draft. You’ll feel a sense of satisfaction having completed a story, rough and unfinished though it may be. If you’ve captured the heart, you’ve got the best of it.

If none of this is working, maybe you’re not writing the story you really want to write. Sometimes we have to start all over again. Or start a completely new story. But beware! At first you’ll be, like, oh yes! This is the novel for me! But when you come to the middle of the story, don’t be surprised to find yourself feeling lost and uninterested again. It’s not easy to see it through. But at some point, if you want to write a novel, you need to finish the damn thing. If there’s no wind in your sails, get out the oars and row. Commit yourself to the page. Only you can write this particular story.

If you get lost or “blocked” try writing a brief synopsis — as if your story was already finished. Write the copy for the back of the book jacket. Don’t try to tell the whole plot, just the highlights. Try drawing a road map of the story. Read your favorite authors for inspiration. Show your beginnings to a trusted friend or writing mentor and ask for suggestions. Avoid talking too much about your novel or you might lose the creative tension needed to write it.

Set aside a block of time each day, even if it’s only half an hour, to work on it. Thirty minutes is all some people can commit to, but if you dedicate yourself to writing during that half hour, you’ll eventually get there. Once you have a first draft, no matter how rough and in need of repair, you will feel a sense of satisfaction. You’ve discovered the heart of the story. It will need revision but each draft gets better and the characters, more alive.

November 11, 2015

How to Write A Novel

November is National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo). Right now thousands upon thousands of stories are being spilled onto the screen as writers around the world commit to 50,000 somewhat meaningful and related words in thirty days. In 2007 I answered the call, writing the first draft of Looking for Redfeather during the month of November. It took 72 more months to revise, edit, and publish the book!

I’ve been asked to lead a writers’ workshop for the students at Prospect Academy next week — the topic being How to Write a Novel.

The workshop is next week, so I’ve been gathering my notes and my thoughts. What will I say to these young writers? How do you write a novel?

There are three rules for writing a novel — unfortunately no one knows what they are. — a humorous quip attributed to Somerset Maugham. I’m going to put a little spin on that and say no one can agree what they are. Because there’s a lot of advice floating around on blogs and social media about how to write a novel. A lot of “should” and “shouldn’t, “must” and “must not” to freeze your fingers and stop your imagination cold. The most ardent advice seems to come from self-styled writing experts. Beware!

The truth is, there are no rules for writing a novel. It’s up to you to capture the essence of your story the best way you can.

Now that we’ve established there are no rules and given you the freedom to write whatever you want to, a few guidelines might help you complete your novel. Some writers like to have structure. They make detailed outlines, conform to an established story arc, and interview their character for back story. Their MO is to write a complete narrative outline first, before going back and fleshing it out with details and dialogue.

At the opposite end of the spectrum are those adventurous souls who sit down and let their fingers do the walking across the keyboard, channeling the characters in their imagination and trusting them with the story line.

Whether you plot everything out in advance and follow the golden story arc– or write by the seat of your pants, or use a combination of the two, it really doesn’t matter. The process of many writers (this writer) falls somewhere in the middle of the two extremes. Either way, the process isn’t linear and becomes messy with successive re-writes. (Like time travel, if you change something in the past it alters the present and the future!) The only thing to do is to write your way out of it.

It might make you feel more confident to remember no novel is perfect; the perfect novel cannot be written. Once you accept that, it gets easier. Well maybe not easier but there is one less obstacle in your way.

Here are a few suggestions I can offer, from my own experience:

A novel is easier to write if you can conceive of the three P’s: A person in a particular place with a particular problem.

Write about a character who interests you, intrigues you, or whom you care a great deal about. Allow that character to come to life and direct their own story. The character can be based on yourself or someone you know — or a combination of people. The character will begin to develop on the page, trust me. Even if you’ve modeled the character after a real person, your fictional character will become unique. Yes, it’s magic.

Get your story out of your head and down on paper or the computer screen. Resist the urge to talk about your story; you’ll lose the fire.

Don’t feel compelled to write chronologically. Even if you are using an outline or other structure, write the part that speaks to you, first.

Try writing the whole story before you begin to revise and edit. This is not a rule, but a suggestion. I know one excellent writer who never goes to the next chapter until the first one is pretty much perfect. The problem I’ve found with that approach is I never get the story finished! What works for me is to capture the heart of the story, the spirit that makes it alive and unique, by writing a beginning, middle and end — and then going back and beginning the many revisions that are necessary. My first drafts aren’t very long — sometimes less than half the length of the finished novel. In that respect a first draft is kind of like an outline that needs to be filled out and expanded upon.

If one method isn’t working, try something else. Read another author for inspiration. Start over, if you have to (we’ve all done it!) But keep writing. Persevere. Write to discover.

Looking for Redfeather, my 2007 NaNoWriMo book, was a Foreword Reviews finalist for Book of the Year, YA category, in 2013. Check out the audiobook, narrated by actor Aaron Landon!

November 1, 2015

Drafting off NaNoWriMo

Hats off to Chris Baty, founder of the wildly successful National Novel Writing Month! Thanks to Baty and his cohorts, November will never be the same for compulsive writers and would-be novelists. Baty started NaNoWriMo in California with 21 participants, back in 1999. Sixteen years later, billions and billions (OK, thousands and thousands) of writers all around the globe are answering the challenge to write the first draft of a new novel of at least 50,000 words in 30 days. (Click here to find out more about the rules.)

Why would anyone want to commit to such an outrageous endeavor? Why subject yourself to the torture of hammering out 1,667 words a day for 30 days?

It’s a little like going to a gym to work out. It helps some writers to sweat alongside other writers — to experience group pain and the accompanying euphoria in order to get in shape.

I was a teenage writer, long before NaNoWriMo was invented. One of my eighth grade friends was also a writer; we used to read each others’ stories, scrawled on lined, three-ring notebook paper, fastened together by dog-earring the corners, tearing a little notch and folding it down. In high school I joined the literary club where we wrote and published Sunburst, an emotive, somewhat histrionic collection of teenage poems and stories typed, mimeographed, and bound with three staples. As a young professional nurse I started a writers roundtable for other nurses at the hospital where I worked. We were low tech back then, long before the internet or Chris Baty existed. Today’s young writers have technology on their side but they still need self-discipline and the drive to do it. NaNoWriMo helps through the herd effect. You can even join NaNoWriMo groups on Facebook if you need that kind of reinforcement.

Baty’s nonprofit organization even has a Young Writers Program geared to students and educators.

Professional writers need encouragement too. Some of us don’t allow enough time for our work. Or we avoid it. Like giving birth, it is an uncomfortable, messy, too-slow process. Sometimes we’re afraid of the work, afraid of the pain, afraid of what we’re bringing forth into this world! It helps to make a commitment — a pledge — to write a certain number of words a day. Which is also terrifying because as any writer knows, much of what you write is crap. But you have to believe that in that growing garbage heap of words there is something important — something worth preserving.

I did it once. NaNoWriMo. In 2007 I made the pledge to write a 50,000 novel during the month of November. At the time I was on the road doing some talks at high schools and libraries about Star-Crossed — my first published novel that had been six years in the making. I signed up in my hotel room and began my story about three runaway teens who meet up on the road, each on their own mission, and go on a hunt for a musician named Redfeather, believed to be Ramie’s estranged father. The first draft of Looking for Redfeather, my 2007 NaNoWriMo project of 55,000 words, was uploaded on the last day of November and I received my NaNo badge.

It took six more years to revise and edit my literary YA road trip which I eventually published under my Fiction House imprint. Looking for Redfeather was a Foreword Reviews IndieFab finalist for YA Book of the Year, 2013, and a Literary Fiction Book Review Spring Spotlight award-winner in 2015. It was one of the most fun books I’ve written, possibly because I wrote the first draft in 30 days.

This year I’ve pledged to finish my current novel-in-progress during National Novel Writing Month. This disqualifies me from officially entering the challenge, but it doesn’t mean I can’t draft off the energy of all those young writers bursting out of the gate today, November 1, writing the beginnings of their brand new novels. Ready, Set, GO! Write your hearts out, kids; I’m right behind you.

That’s my NaNoWriMo story — what’s yours?

October 30, 2015

Halloween book giveaway

Painting by John William Waterhouse, 1886, via Wikimedia Commons.

Happy Halloween!

It’s that time in America when kids dressed as superheros and princesses in store-bought costumes come knocking at the door begging for candy. This year I’m dressing as a witch (or maybe revealing my true persona) and instead of candy I’m handing out books, tricks be damned. Casting spells with words, because that’s what witches — and writers — attempt to do.

If you’d like to knock on my door and receive one of my spells, just leave a comment on my website and tell me what costume you’re wearing — and which story you’d prefer.

In exchange, all I want is your undivided attention…

Double double toil and trouble, Fire burn and cauldron bubble…

These are the books I’m giving away — this weekend only…

October 26, 2015

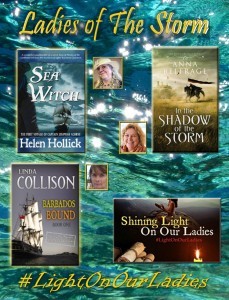

Shining Light on our Ladies

I’m delighted for Patricia MacPherson, my 18th-century cross-dressing protagonist, to be among those fictional ladies in the spotlight this week, as part of Helen Hollick‘s October blog tour celebrating female protagonists through the centuries. Blog tours are fun ways to be introduced to authors you might not otherwise be familiar with. Welcome aboard my blog, a Sea of Words; charting a course from imagination to publication. As you can tell from the title, the major focus of my blog is the process of writing.

I was thrilled when Helen invited me to participate because I’ve been at work for several years now on Leaving Havana, the third book in the Patricia MacPherson Nautical Adventure Series.

Patricia MacPherson came to me in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. She appeared in my imagination, insistent that I tell her story. It was the middle of the night while I was at the helm of the HM Bark Endeavour (yes! — I was taking my turn steering the famous replica ship!) on a passage from Vancouver to Hawaii in1999. My husband and I had joined the ship with a few dozen other middle-aged wannabe sailors, as “voyage crew” — temporary hands to help sail the old girl on a part of her journey around the world that year. When we signed on we agreed to stand our watch, climb aloft to make and furl sail, help clean and maintain the ship, and obey the captain and officers. For three weeks we essentially lived the lives of 18th century sailors, standing our watch, steering the ship, and scrambling up the ratlines and out on the foot rope beneath the yard arm high above the deck, to let loose or take in canvas. We took our turns at galley duty, we maintained the vessel, and when our watch was over we strung our hammocks from the deck head an slept, exhausted, until the ship’s bell roused us again. It was very much like a time machine back to life aboard an 18th century British sailing ship. I would later write an article published in Sailing Magazine about my experience, entitled Three Weeks Before the Mast.

But by the time I disembarked in Hawaii I also had the beginnings of a novel in my mind — a story about a young woman aboard an 18th century sailing ship — much like the ship I had just been a part of. The ship was my setting — I knew it intimately. Like me, my female protagonist would not be just a passenger. One thing I had discovered first hand was that women can do anything men can do, when it comes to sailing or maintaining a ship. Maybe there was more truth than I realized to those old 18th century British ballads and broadsheets about girls going to sea dressed as men.

Although the character Patricia, had made herself known to me, and although I knew the setting like the back of my hand, I had a lot of research to do — six years’ worth — before I had a finished manuscript. In that research I discovered many documented cases of girls who really did go to sea disguised as boys. In most cases they were only discovered while being treated for life-threatening battle wounds. Think of the many who might never have been caught!

My novel Star-Crossed was published by Knopf in the fall of 2006 as a Young Adult historical novel. In 2007 it was chosen by the New York Public Library to be among the Books for the Teen Age. I wrote the rough draft of a sequel, but Knopf wasn’t interested in a series; they had published it as a stand-alone. My agent declined. But Tom Grundner, founder of Fireship Press and Editor-in-Chief, wanted to acquire my series and in 2011 Surgeon’s Mate; book 2 of the Patricia MacPherson Nautical Adventure Series was published. In 2012 Fireship Press published a slightly revised Star-Crossed (now out of print) as Barbados Bound; book 1 of the Patricia MacPherson Nautical Adventure Series. Tom was enthusiastic about my books and we were discussing a third book when he died suddenly. My plans for the third book were abandoned for a time, as I felt I had lost not just an editor but a mentor.

Patricia has languished for a few years, seemingly lost at sea, while I’ve completed several other novels I had in the works. Tired of waiting to be rescued, she has managed to jury-rig a sail and find the wind to fill it. She insists I continue her story. I’m not sure I could have, had I not found a new mentor and several trustworthy writing “mates” who know nautical history and are supportive and encouraging of our efforts — Patricia’s and mine. I am very grateful for these writers — and for the readers who have taken the time to let me know how much they want to read more adventures of Patricia MacPherson. Unlike Star-Crossed, the version Knopf published , the Patricia MacPherson Nautical Adventure series are adult novels, not YA .

Barbados Bound (first published as Star-Crossed by Knopf in 2006 as a stand-alone YA historical novel.)

Portsmouth, England,1760. Patricia Kelley, the illegitimate daughter of a wealthy Barbadian sugarcane planter, falls from her imagined place in the world when her absent father unexpectedly dies. Raised in a Wiltshire boarding school sixteen-year-old Patricia embarks on a desperate crossing on a merchantman bound for Barbados, where she was born, in a brash attempt to claim an unlikely inheritance. Aboard a merchantman under contract with the British Navy to deliver gunpowder to the West Indian forts, young Patricia finds herself pulled between two worlds — and two identities — as she charts her own course for survival in the war-torn 18th century.

In writing Patricia MacPherson’s story I wanted to explore what it might have been like for a young woman in the eighteenth century to live, work and reinvent herself aboard a ship. Although it’s a work of fiction, I have attempted to maintain historical accuracy.

Eighteenth century merchantmen and British Naval ships did indeed carry women — wives, girlfriends, passengers, prostitutes, laundresses — even though the Admiralty had rules on the books prohibiting it. Children too, were commonly found aboard ships. Some were born on the passage and some went to sea at an early age for their livelihood.

According to numerous sources, some women really did enlist in the navy and army in male disguise. Several accounts tell of women who worked for months, and in some cases years, before being found out. These impostors carried out their duties, performed bravely in battle and were only discovered to be female after being wounded in the line of duty. (The artifice may have occurred more often than has been recorded, simply because some women may have successfully carried it off.)

Thought the work was hard and not without danger, a ship provided room and board, and a chance for adventure. In fact, it still does.

Surgeon’s Mate; Book 2.

It’s late October, 1762. After surviving the deadly siege of Havana, Patrick MacPherson and the rest of the ship’s company are looking forward to a well deserved liberty in New York. But what happens in that colonial town will change the surgeon’s mate’s life in ways she could never have imagined. Using a dead man’s identity, young Patricia Kelley MacPherson is making her way as Patrick MacPherson, surgeon’s mate aboard His Majesty’s frigate Richmond. She’s become adept at bleeding, blistering, and amputating limbs; but if her cover is blown, she’ll lose both her livelihood and her berth aboard the frigate. The ship’s gunner alone knows her secret – or does someone else aboard suspect that Patrick MacPherson is not the man he claims to be? Surgeon’s Mate, book two of the Patricia MacPherson Nautical Adventure Series, is a work of fiction inspired in part by the historical accounts of actual 17th and 18th century soldiers, sailors and marines who were in fact women. Included in this group were Christian Davies, Hannah Snell, Mary Lacy, Mary Anne Talbot, Deborah Sampson, to name but a few.

(Here’s a photo of me at the 2012 Historical Novel Society Conference costume party — cross-dressed as Patricia’s male persona, Patrick MacPherson.)

Leaving Havana; Book 3 of the Patricia MacPherson Nautical Adventure Series

In this work-in-progress Patricia continues her association with Yankee smugglers at great risk, and is reunited with three people from her past, making some rash decisions with enormous, life-changing consequences. Look for it to be released by Spring, 2016…

Now let me hand the microphone to Helen Hollick, an amazing historical novelist who writes in several different eras. If you are an historical novel aficionado, chances are, you already know this author — a force of nature, she is — who writes in several eras. I had the good fortune to be on a nautical historical panel with her at the 2012 Historical Novel Conference in London and since I have become acquainted with her and her work I’ve been greatly inspired by her writing process and her writing style — not to mention her energy and willingness to encourage and promote historical fiction by emerging writers.

Helen lives on a thirteen-acre farm in Devon, England. Born in London, Helen wrote pony stories as a teenager, moved to science-fiction and fantasy, and then discovered historical fiction. Published for over twenty years with her Arthurian Trilogy, and the 1066 era, she became a ‘USA Today’ bestseller with Forever Queen. She also writes the Sea Witch Voyages, very engaging, somewhat salty, pirate-based fantasy adventures. The ocean connects us all, and that’s how I first found Helen. As a supporter of Indie Authors Helen Hollick is Managing Editor for the Historical Novel Society Indie Reviews, and inaugurated the HNS Indie Award. Please check out her blog post today, Let us talk of many things

As for her ladies — her female protagonists and supporting characters – every sea captain needs a woman to come home to, but Captain Jesamiah Acorne (ex-pirate) has three to choose from: Tiola ( a midwife and a white witch) ‘Cesca, an English woman with a Spanish name (a spy) and Alicia… well, all Alicia wants is Jesamiah’s money…

A rollicking nautical adventure!

Now, let me reacquaint you with Anna Belfrage.

Anna is a delightful author I featured here on my Sea of Words blog last year. (See, Anna Belfrage talks of time travel and other writing secrets)

Had Anna been allowed to choose, she’d have become a professional time-traveller. As such a profession does not exists, she settled for second best and became a financial professional with two absorbing interests, namely history and writing.

Presently, Anna is hard at work with The King’s Greatest Enemy, a series set in the 1320s featuring Adam de Guirande, his wife Kit, and their adventures and misfortunes in connection with Roger Mortimer’s rise to power. When Anna is not stuck in the 14th century, chances are she’ll be visiting in the 17th century, more specifically with Alex and Matthew Graham, the protagonists of the acclaimed The Graham Saga. This series is the story of two people who should never have met – not when she was born three centuries after him.

Meet Anna’s ‘lady’…. She was blackmailed into marrying an unknown knight. She hadn’t expected having to save his life as well…

visit Anna and – and a chance to win TWO of Anna’s books! Annabelfrage.wordpress.com

We are historical fiction writers shining the light on our female protagonists; thank you for your attention!

If you’ve enjoyed our posts please share and tweet #LightOnOurLadies. We appreciate your interest! In case you came late to the party, here’s what you missed:

The first three weeks of the #LightOnOurLadies tour:

6th October: Helen Hollick with Pat Bracewell and Inge Borg

13th October: Helen Hollick with Regina Jeffers, Elizabeth Revill and Diana Wilder

20th October : Helen Hollick with Alison Morton and Sophie Perinot

Keep that spotlight shining, ladies!

October 23, 2015

Water Ghosts: Featured in Literary Fiction Book Reviews

“Linda Collison’s Young Adult novel, Water Ghosts, is the story of fifteen-year-old James McCafferty, whose parents have signed him up for an adventure-therapy cruise for teens on a traditional Chinese junk. From the beginning, James, who sees and hears things other people don’t, feels like the ship and its young crew of misfit kids are setting sail toward doom. James befriends a young Asian girl named Ming and they, along with Truman, whom James suspects has Asperger’s, become a trio of outcasts. Accompanying them on the trip is a trio of older, larger and stronger teenage bullies. The junk sets sail on a sea James soon believes is infested with ghosts of those who have drowned. Chinese ghosts. And one in particular, Yu, who waits for the junk to pass over the place where he drowned so he can switch places with James.

The young crew eventually find themselves in a Lord of the Flies situation, alone at sea after the adult counselor disappears and First Mate Miles Chu goes looking for her in the only lifeboat, never to return. Then the captain is found dead in his quarters. Will the outcasts and bullies be able to work together to survive?

You can read the full review by clicking on the above link. A young reader’s review is forthcoming…

October 11, 2015

Strong Female Protags Wearin’ the Pink

The days of the stereotypical helpless heroine of the romantic Gothic novel are long-gone — well, except for characters like the passive, doe-eyed Bella Swan who succumbs to the sexy vampire Edward in Stephanie Meyers’ Twilight… OK, so maybe those days are not long-gone; the helpless heroine waiting for a man to save her (or suck the life out of her) continues to be a pervasive meme in literature no matter how much I sigh and roll my eyes. The problem is, writing a strong female character is rather frightening. Having a mind of their own, strong female characters often take on a life of their own — Watch out!

But what is a strong female protagonist?

Here’s what she is not: “Feisty.” “Spunky.” Has “feisty” or “spunky” ever been used to describe a man’s character? OK, maybe if he’s ninety-six years old, in his dotage and charmingly irascible to the attendants at the nursing home. “Feisty” and “spunky” are diminutives of STRENGTH — which in many cultures is considered a male trait, exclusively. Yet strength — whether physical, mental, emotional, moral, or spiritual — isn’t exclusive to the Y chromosome.

We all know women are strong — we know it first-hand — so why do some of us have a hard time showing their strength? Are we afraid we’ll make our male protags seem weaker by comparison? Are we afraid of alienating male readers?

Writers, is your main femme strong? Is she potent? Tough? Tenacious? Resilient? How is she strong? What are her weaknesses that undermine her strength? How do you balance these to create a human being in full without devaluing your male protag?

V.E. Ulett writes historical fiction set at sea during the age of sail. Her trilogy, Blackwell’s Adventures, is “a story of honor, duty, social class and the bond of sensual love,” says Joan Druett. nautical historian and novelist who knows very well what it was to be a strong, sea-going woman in any age. Ulett writes with gritty candor about topics some historical novelists avoid. I asked her to tell us more about her female protag’s strengths and how she drew upon them. Was there historical evidence for a woman of her time having this particular trait? Do any women today exhibit this fortitude?

Ulett replies:

Mercedes was raised on the Spanish settled western coast of America, in her youth Mercedes fought with swords, sailed on ships, and found the love of her life. In Blackwell’s Homecoming Mercedes faces illness, aging, and cultural divides while still passionately attached to Captain Blackwell and their children.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that everyone’s life has been touched by cancer and other grave illnesses. In historical fiction, in fiction writing in general, we make choices about what to leave in and what to edit out. A constant balancing act between credibility, perceived accuracy, and entertainment value. In my novel, Blackwell’s Homecoming, one of the main characters has breast cancer and endures a mastectomy under early 1800s surgical conditions.

Both breast cancer and the possibility of surgical treatment were known in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as movingly depicted in the HBO series John Adams, and more to the point of this post as described by Madame D’Arblay in a first hand account of her surgery in The Diary and Letters of Madame D’Arblay. Madame D’Arblay, or Francis Burney, is a literary hero of mine, for her valuable seven volume Diary and Letters and her novels. When I wrote my scene of a character undergoing this operation, I turned to Madame D’Arblay’s letter to her sister, describing her experience, as a guide in capturing the patient’s or sufferer’s perspective. Madame D’Arblay’s letter was the inspiration for the surgical scene I wrote, though I didn’t flatter myself that I could create anything so moving, so graphic, or so well told as Madame D’Arblay’s account. She was a remarkably intelligent, brave, and incomparable woman and writer. Madame D’Arblay recovered from the surgery, living to the age of 88.

A couple of the pre-publication readers of Blackwell’s Homecoming let me know how uncomfortable the surgical scene made them. One commented that I might lose readers who would go no farther than the mastectomy scene, especially men of a certain age. It was hinted the scene was an instance of when it might be better to tell rather than show. Nothing will get an author’s attention faster than the suggestion we might lose readers, so I was given serious pause. What to leave in and what to take out?

How to balance the sensibilities of readers who may have had direct painful experience with cancer, with a desire to depict the courage, both physical and in strength of mind, of a woman undergoing the trauma. I was also very much concerned with whether it diminishes the strength and honor of women to have their events, however dreadful, pushed off-stage. I turned to Madame D’Arblay’s account, where she describes how difficult it was to relive the surgery in recounting it for her sister.

“I have a head-ache from going on with this account! and this miserable account, which I began 3 Months ago, at least, I dare not revise, nor read, the recollection is so painful.”

After her husband Alexandre D’Arblay includes a note to Fanny’s sister Esther and their family with her account, Madame d’Arblay concludes in part, “God bless my dearest Esther—I fear this is all written—confusedly, but I cannot read it—and I can write it no more, therefore I entreat you to let all my dear Brethren male and female take a perusal—”

I left the surgery scene in my novel, however uncomfortable, because I believe this is how to depict strong female characters, by showing what women have survived and overcome.

A woman’s fortitude — it’s more than a pink ribbon and a month of awareness.

Eva Ulett is the author of Captain Blackwell’s Prize (book 1), Blackwell’s Paradise (book 2), and Blackwell’s Homecoming. To find out more about the Blackwell’s Adventures Trilogy visit veulett.com or the publisher’s website Old Salt Press.