Linda Collison's Blog, page 21

October 4, 2013

The Lost Letters of Lizzie Austen; a serialized blog-novel (2)

With trembling hands, I untied the faded blue ribbon holding the first bundle of letters together. Forgetting to put on my archiver’s cotton gloves, I delved into the one on top; a folded piece of parchment paper, water marked and stained with what looked like splotches of tar. It had been sealed, in fact, with a well-placed drop of bubbling tar, as if from the deck of a ship. Although I was sure this was a literary hoax, I delved in, anxious for a diversion from my research, which had grown quite tedious.

The date was unreadable, a mere blur of ink engulfed in a water mark. Below the date I could make out the letters HMS but the ship’s name was smudged beyond recognition. My eyes flew to the body of the letter.

Dear Jane,

How to begin? How to introduce myself to my own sister, by birth? A sister who should know me well and have tender feelings for me, but for our parent’s neglect. Perhaps you do have some recollection of my birth? Or have you convenientlly forgot, along with the others? The way you forgot our poor George. And Aunt Lenora, for that matter. Out of sight, out of mind, it worked well for our family, did it not? Then again, there were so very many of us… Mother and father were forced to chuse which ones to give their attentions to. I (being the third girl, and painful to look at) was easy to forget.

I was told by my foster mother that I was born in January of 1778, a healthy pink female, bald as a billiard, my face covered with stork bites. After three months at the breast mother dearest put me out with them, John and Elizabeth Littleworth (their surname tells it all, does it not? England’s under-valued people, the poor-to-middling, the backbone of our great nation) near two miles away at a Cheesedown farmhouse near Deane. Here I thrived. Or, at least, I survived.

Mother farmed you out too, dear sis, to the very same family. But you, she came back for, once you were out of nappies and past the mewling, puking, bawling stage. Me, she quite forgot. At least, I prefer to think she simply forgot me. Unlike our brother George, who was placed elsewhere because he was dim-witted and had embarassing fits of some sort. And Edward, lucky Edward, but we’ll speak of him later.

Like you, sister Jane, I lived my first years in the Littleworth’s thatched-roof hovel on the Cheesedown, near Deane; a noisy, mud-floored tenant farmhouse crowded with kids of all ages. That’s how my foster mother supplemented her husband’s meagre earnings, minding the brats of more well-to-do families. Because our father was the parson, dear Mrs. Littleworth probably hoped to gain a little influence with the Almighty. I cannot help but wonder, since they never came for me, if I was not my father’s daughter, afterall. Or p’raps I was my father’s daughter, but not out of the loins of our dear mother. But that’s a scandelous thing to say about one’s birth parents. I prefer to think they simply mislaid me, like a stocking lost under the bed. And who cares? For what good is a daughter, except to match up and marry off to a wealthy family? But an ugly girl is so difficult to foist off –unless she comes with a nice dowry. Yet ugly has served me well, as you shall see.

I write you, hoping you might write a story about me, dearest sister. It’s a lurid tale, one that Defoe and Cleland would be envious of. Your brothers are not the only ones who went to sea for their li

The remaining sentence and last paragraph on the page is washed out and unreadable. At the very bottom of the page I can make out a closing and signature:

Your forgotten sister, etc. etc.

Lizzie, a.k.a. Carlisle Littleworth Austen

Copyright 2013 by Linda Collison

October 1, 2013

Lost Letters of Lizzie Austen

The Lost Letters of Lizzie Austen; a novel in progress.

The Lost Letters of Lizzie Austen; a novel in progress.

by Linda Collison

I was sitting in the Greenwich library, staring at my notes and nearly falling asleep, having turned up little of note in my research that afternoon, when someone came up behind me, and coughed politely. I turned to see an old seaman, dressed in costume, a performer or re-enactor, perhaps. But on second glance I realized it might be a woman. She looked to be out of her mind; quite mad as they say here in the motherland. Or maybe the poor thing was lost — or looking for the restroom. Looking again, I saw she might not be as old as I first assumed. Or maybe she was far older than I could imagine. Her hands were so very wrinkled, as if she had been too long in a salty bath. Her hair dripped from under her hat.

“Can I help you?” I whispered.

She looked at me with shrewd eyes, sizing me up. “Yes ma’am, I believe you can.” She then dropped her seaman’s gear bag at my feet with a thump. It was damp and salty, speckled with tar, and smelled like bilge water.

“What’s that?”

“Jane’s letters.”

“Jane? Do I know Jane?”

She snorted. “Everybody knows Jane. Jane Austen.”

I blinked. Poor woman was obviously delusional. “But why give them to me”, I asked, not wanting to seem rude. “If they’re really letters the great novelist penned, shouldn’t you give them to the librarian? An historian, perhaps? Or to the museum? You could aution them at Sotheby’s and make your fortune.”

She shook her head slowly. Sadly. A strand of seaweed fell out of her hair. “They wouldn’t believe me. They would think it’s but a hoax.”

“But why give them to me? I’m an American. So unworthy.” My attempt at satire went completely unnoticed.

“True. But you know. About my kind. And you’re a writer.”

“Your kind?”

She nodded, biting her lip. Allowing her eyes to meet mine. “Girls in breeches. On ships. In disguise.”

What did that have to do with Jane Austen, I wondered. Or maybe I spoke aloud.

“Jane Asten was my sister,” the woman said.

My heart thumped in my throat. Was this a ghost? Was I mad?

“You’re Cassandra?”

She rolled her eyes and sighed. “Hardly. Do I look like Cassandra? I’m her other sister. Lizzie.”

Before I could say a word, she blurted out, “I’m the sister mother conveniently forgot about. Forgot, then denied. But it’s here in these letters, it’s all here. She thought she burned them but I tricked her, you see. I made copies of all my letters before I sent them – and I saved all she ever sent to me. You might say I was her alter ego – except I was her younger sister. The one they forgot. It’s all there. I want you to have them. I want to you tell my story.”

I didn’t believe a word of it, of course, though as a novelist, the idea grabbed me and wouldn’t let go.

“What do you want for the letters? The whole sack, “I asked.

“Fifty quid. They’re no longer any use to me, but I can’t just give them away, now can I?” A slight smile tugged at her lips.

Heart thumping, I reached for my handbag and rummaged through my wallet. I had just enough money. Surely the letters were fake, or maybe the sack was filled with paper from the waste bin, but I must say, my curiosity was piqued. I closed my handbag and reached to give her the money, but she was gone. Vanished. Leaving only the damp canvas sack of letters, a puddle of water, and the slight smell of the harbor at low tide.

To be continued…

copyright 2013 Linda Collison

September 18, 2013

Hannah Snell, Royal Marine

One of the most well-known cross dressers who went to sea was Hannah Snell, born in 1723, to a hosier/dyer and his wife on Fryer Street in Worcester, England. Her grandfather was Captain-Lieutenant Snell who took part in the conquest of Dunkirk and the battle of Blenheim, a turning point in the War of the Spanish Succession.

Hannah was one of nine children. Except for one of her sisters, all nine grew up to become soldiers, sailors, or the wives of such. Hannah reports playing army as a girl; no surprise, having six brothers. She formed a company of young soldiers among her playfellows, of which she was chief. “Young Amazon Snell’s Company” would parade through the town of Worcester.

After the death of her parents, Hannah went to London to live with her sister and brother-in-law James Gray, a carpenter in Wapping. At twenty-one she married a Dutch sailor, James Summs, who abandoned her when she was seven months pregnant. The baby didn’t live long and Hannah set out to find him, taking her brother in law’s name, and a suit of his clothes. She claims to have enlisted in the army but soon deserted, then traveled south to Portsmouth and enlisting in the marines, where she served aboard the sloop-of-war Swallow. The Swallow was sent to India with Admiral Boscawen’s fleet and Snell was sent ashore to fight the French in Pondicherry. She was wounded numerous times. One wound was to the groin. She removed the ball and dressed it herself, with the help of an Indian nurse, so her sex would not to be discovered. As soon as her health was restored she was sent on board the Tartar Pink to perform the duties of a common sailor, then was assigned to the Eltham man-of-war which set sail for Bombay.

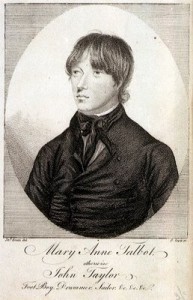

Hannah Snell, Royal Marine in Captain Graham’s company, Colonel Fraser’s regiment.

Hannah Snell lived and worked as a man for more than four years. When at last she returned to her sister and brother-in-law’s home in London, she quit her disguise — then capitalized on her bold experiences by selling her story to the publisher, Robert Walker, who wrote and printed it. (Like many women of her time, Hannah could read but she couldn’t write proficiently.) Hannah also went on tour, re-enacting military drills before a thrilled audience, achieving significant fame. Hannah then applied for – and was granted –a pension for her war injuries.

Discovering that her estranged husband, James Summs, had been executed for murder, Hannah was free to marry again. She did so, outlived that husband, then married a third time and gave birth to a son. She lived on her pension, and on the money she made as a street peddler, to the age of 86 when she was committed to Bedlam hospital with “the most deplorable infirmity” (which might have been dementia and seizures secondary to neurosyphilis or meningovascular syphilis –forms of tertiary syphilis that present 4-25 years after infection). If this was the most deplorable infirmity the former marine suffered from, she might have contracted it from her first husband.

Hannah died in Bedlam in 1792.

The Female Soldier or The Surprising Life and Adventures of Hannah Snell was written, printed and sold by R. Walker, of London, in 1750. Some of the incidents he might have exaggerated, confabulated or otherwise made up, but by and large, her story is believable. Tales of women soldiers and sailors, disguised as men, were popular among Britain’s lower classes, who bought them in on the street in the form of inexpensive broadsheets and ballads. The publication of Hannah Snell’s story gave wider recognition among the middle and upper classes; people who could afford to buy books.

The protagonists of the many stories and ballads of cross dressing women were said to be in search of boyfriends or husbands who had run off to war, or pressed into the navy. This became a formulaic story, guaranteed to sell broadsheets and ballads. This motivation was likely interjected by male writers who could imagine no other reason a young woman might want to join the army or the navy.

And why would they, you ask? For the same reasons a young man might: The paycheck, the billet, the food, the camaraderie, the adventure, the chance to be part of a greater cause, the opportunity for travel — and the possibility of meeting a man (or in some cases a woman) worthy of your love? Most people lived hand to mouth, and struggled to get by. If you didn’t have money, a title, or a good man to support you, life was very hard for an 18th century woman. Who wouldn’t sell a petticoat and go to sea?

All ye noble British spirits

That midst dangers glory sought,

Let it lessen not your merit,

That a woman bravely fought…

Resources:

The Lady Tars: The Autobiographies of Hannah Snell, Mary Lacy and Mary Anne Talbot, with a Forward by Tom Grundner. Fireship Press, 2008. Tom Grunder encouraged my writing about the crossdressing Patricia MacPherson, and gave me this book to help me with my research.

For more salty history, visit my fellow shipmates blogging about all things nautical:

J.M. Aucoin http://jmaucoin.com/2013/09/16/nautical-blog-hop-black-men-the-black-flag/

Helen Hollick http://ofhistoryandkings.blogspot.co.uk/2013/08/weigh-anchor-nautical-blog-hop.html

Doug Boren http://doug1401ck.blogspot.co.uk/2013/08/pirates-and-their-ships.html

Margaret Muir www.margaretmuirauthor.blogspot.com

Julian Stockwin http://julianstockwin.com/welcome-front-page/blog-page/

Anna Belfrage http://annabelfrage.wordpress.com/2013/09/16/by-the-sea-by-the-beautiful-sea/

Andy Millen http://wp.me/p3GFor-1W

V.E. Ulett http://www.veulett.com/2013/09/16/weigh-anchor-nautical-blog-hop/

T.S. Rhodes http://thepirateempire.blogspot.co.uk/

Mark Patton http://mark-patton.blogspot.co.uk/

Katherine Bone http://www.katherinebone.com/

Alaric Bond http://blog.alaricbond.com/

Ginger Myrick http://gingermyrick.com/nautical-blog-hop/

Judith Starkston http://www.judithstarkston.com/articles/the-wonders-of%E2%A6age-shipwrecks/

Seymour Hamilton http://seymourhamilton.com/?p=168

Rick Spilman http://www.oldsaltblog.com/

James L. Nelson http://jameslnelson.blogspot.co.uk/

S.J. Turney http://sjat.wordpress.com/2013/08/28/nautical-meanderings/

Prue Batten http://pruebatten.wordpress.com/2013/09/09/knowing-the-ropes/

Antoine Vanner http://dawlishchronicles.blogspot.co.uk/

Joan Druett http://www.joan-druett.blogspot.co.nz/

Edward James http://busywords.wordpress.com/

Nighthawk Newshttp://nthn.firetrench.com/2013/09/stand-by-to-raise-anchor/

September 16, 2013

Who wouldn’t sell a petticoat and go to sea?

A sailor takes her ease

artwork by Eye Be Oderlesseye.

mimifoxmorton.blogspot.com

Women in breeches — I got caught up in the masquerade back in 1999, while serving as a voyage crewmember aboard the HM Bark Endeavour, a replica of James Cook’s 18th century ship, which was circumnavigating that year. On my three-week passage from Vancouver to Kealakekua, Hawaii I worked alongside 53 officers and men (one of whom I was married to) to sail, steer, and maintain the ship. Eight of us were female. On this passage of a lifetime, I became intrigued with the idea of a woman dressing like a sailor and doing a man’s job aboard a ship – because that’s exactly what I was doing! I figured if a middle-aged woman could do the work, surely a much younger gal would have no problem.

In spite of the persistent, old husbands’ tale that women are bad luck at sea, women have long been going to sea, luck be damned. But for a period of several hundred years some of them had to resort to disguise.

And for some, it ended badly. From the St. James Gazette, supplement to the Manchester Courier on July 5, 1890 we hear this snippet of a story:

The case of the poor little sea apprentice “Hans Brandt” who the other day fell into the hold of the barque Ida of Pensacola, at West Hartlpool and was killed, adds one more name to the long list of women who, for one reason or another, have put aside the garments of their sex and have donned the habits and imitated the ways of men. Not until “Hans Brandt’s” body was being prepared for burial was it discovered that the Ida’s apprentice was a girl… (britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

From the Renaissance through the Victorian age there are many acounts of women in disguise working aboard ship as sailors, servants, skilled craftsmen, marines –and even a few officers, such as Anne Chamberlyne, twenty-three year old daughter of a lawyer, who served aboard the Grifffin Fireship, commanded by her brother Clifford, during the Battle of Beachy Head in 1690. Most of these femmes fared better than poor Hans Brandt who fell into the hold. Some went on to write their memoirs. Some became immortalized in folk songs. And some, like Anne Chamberlyne, had memorials errected in their honor.

The first books I came across that were entirely devoted to women at sea were Joan Druett’s Hen Frigates, and She Captains; Heroines and Hellions of the Sea. I soon discovered many other works, but Joan’s books introduced me to the world of women on ships. Another of her books on the subject is Petticoat Whalers; Whaling Wives at Sea, 1820-1920. Over the years I’ve collected many more sources. Historians Lesley and Roy Adkins, authors of several British Naval history books, have been very helpful in sharing their own research with me.

Just as I was writing this post, Andrew Beltz, one of the crew aboard “All Things Nautical” Facebook group gave me a hot tip about Louise/Louis Giradin, a French woman who masqueraded as a steward on La Recherche, which set out 1791 under the command of Bruny d”Entrecasteaux, in search of the missing La Perouse.

“She had appeared at Brest disguised as a man, with a letter of introduction to Mme Le Fournier d’Yauville. She persuaded her brother Jean-Michel Huon de Kermadec, then second in command to d’Entrecasteaux, to recommend her as a steward on the Recherche. It appears that d’Entrecasteaux knew her secret, and gave his approval… She had a small but separate cabin… During the voyage, Girardin maintained a male identity, despite widespread suspicion. She even fought a duel with a crew member who questioned her gender… ” from — Journeys of Enlightenment

While Louise Girardin is honored with a plaque in Tasmania, few scholars have given serious attention to the many women soldiers and sailors of the pre-modern era. Not many fiction writers have given life to their stories, either. Crossdressing women on ships seem to be regarded by many historical novelists as unwanted intruders into the male domain of wooden ships. Why can’t the damned dames just stay home, card wool, and mind the starving brats? OK, maybe there were a few of these broads in breeches (obviously lesbians) – but NOT on my ship, dammit! Julian Stockwin includes a crossdressing stowaway named Pookie in one of his Kydd adventures, but for the most part, they are shunned.

But crossdressers were once objects of admiration. Beginning in the Elizabethan era and continuing through the 19th century, stories and songs about young women gone to war on land or sea, were popular among the working classes of Great Britain and North America. According to Dianne Dugaw, these folk songs were as well-known in their time as Blowin’ in the Wind was, in the 1960’s. The female soldier or sailor was an enduring motif – a character who displayed both male courage and female fidelity. In most of these ballads (Dugaw cites hundreds of them) the theme is that of a virtuous woman gone to war in search of the man she loves. This heroine captured the imagination of the public for hundreds of years but died out in the twentieth century, as women’s rights became more of an issue — and perhaps more of a threat.

“But how did they get away with it?”

I can only throw out some educated guesses based on my own experience and what others have to say on the matter.

As Joan Druett, Suzanne Stark, and other nautical historians have pointed out, there were many young boys serving aboard these ships. A female in breeches might easily pass as a teenaged boy. We’ve all seen such epicene youngsters in that awkwardly beautiful stage of development; people who could be either male or female, we can’t be certain.

Before the twentieth century the navies didn’t require thorough physical exams. The only time seamen were required to strip was if they were about to be flogged. The navies needed capable men – especially when a war was on, which was much of the time in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. If someone presented themself as a man and was dressed like a man, and gave a man’s name – why, he would be welcomed aboard, no questions asked. Who cared if he had a smooth cheek and a soft voice? Ample breasts are easily flattened. Loose breeches rather than tight ones would hide what wasn’t there. My fictional crossdresser Patricia/Patrick MacPherson is by nature flat-chested with boyish hips and a complexion ruined by freckles. It’s only her voice she has to work on. After a time it becomes second nature.

Having lived and worked aboard the Endeavour Replica, I can tell you that seamen are kept busy most of the time and people aren’t lurking around corners waiting for you to flash your undergarments or to see what’s hidden inside them. Eighteenth-century ships were ill-lit and extremely dark belowdecks, even during the daytime. People didn’t bathe often; they seldom changed their clothes. Women likely held their bladders until after dark before relieving themselves in the heads, or the “seats of ease.” People in crowded places, such as ships, tend to respect one another’s privacy. As sodomy was punishable by death, men likely tended to keep their eyes and hands to themselves, once they sailed away from the prostitutes who came to the ship by the boatloads when the ships were at anchor. Then again, the warrants could take their wives to sea with them –the ship was their home –so 18th century ships were not the exclusive male clubs some novelists make them out to be. There were women on many ships and maybe some of these warrant’s wives recognized and helped their sisters in disguise.

What of menstrual periods, some ask me. If you’re a squeamish male, you might want to skip the rest of this paragraph. Well, what of it? I mean, can you walk into a crowded room today and pick out the women who are menstruating? I doubt it. There were rags – and there was oakum, the fibers of worn-out ropes picked apart and collected to reuse as caulking. Pretty scratchy, but it might work in a pinch. Beause many of the seamen suffered from constipation and bleeding hemmorhoids, blood-stained breeches would not draw much notice – and the stains could be covered up with tar, plentiful on a ship. Then again, amennorhea may have been the rule. The Mayo Clinic lists stress, low bodyweight and excessive exercise as conditions which can cause the cessation of menstruation. Due to the hard work and limited diet, women posing as men might have skipped menses or have had very light flows, easily contained. OK squeamish males, you can start reading again.

Maybe some of these masquerading women had sponsors – men or women aboard who knew their secret and helped them get by. Maybe they were friends or lovers on land. Maybe the sponsor felt compassion for them. Maybe they admired them. Then again, maybe some of these women were coerced into giving sexual favors in return for guarding their real identity.

In The Discovery of Jeanne Baret (Crown Publishers; 2010) Glynis Ridley suggests that the the crossdressing Jeanne who went on Bougainville’s expedition as the botanist Commercon’s assistant, was gang-raped by some of the crew on the island of New Ireland, and subsequently became pregnant, delivering the baby on Mauritius, where she remained for seven years before completing her circumnavigation. Ridley’s interpretations of the accounts of Bougainville and his officers, is a dark and chilling one. I don’t always agree with the conclusions she comes to, but the case she presents is plausible. Although in Ridley’s interpretation it wasn’t the sailors who gang-raped Baret, but the other servants and possibly, the ship surgeon.

So why did they do it? The paycheck was of course, the big draw. Always in arrears, the pay was likely more than a femme sole could make selling fish — or selling her favors. The roof over her head, leaky though it might be, was a nice perk. As were the three square meals of weevily ship buscuit , mouldy cheese and salt beef. A ration of grog and a hammock to sleep in? And aboard a naval ship, the chance of prize money, which was divided among the crew! Are you kidding me? Who wouldn’t sell a ragged petticoat and go to sea?

But some females were coerced into the role of cabin boy by their masters. Mary Anne Talbot, for instance. Talbot’s master was militia captain Essex Bowen, who assigned her with boy’s clothing, the name of John Taylor, and brought her along to the West Indies as his personal servant. We can only imagine the many tasks she was required to perform for him… Another reported case is that of thirteen-year-old Rebecca Ann Johnson whose father dressed her as a boy and apprenticed her to a collier ship where she served four years.

But surely a few girls went to sea primarily for the adventure, as I did aboard Endeavour.

How many? We’ll never know. How did they get away with it? We can only surmise. What I can tell you for certain is that a woman can do a man’s job aboard a sailing ship. I did it, and I earned the respect of my male watchmates, whose knees trembled as much as mine the first time we climbed up the ratlines, up and over the futtock shrouds, on up to the cross trees and out on the foot rope to make and furl sail. When no sail changes were required, we were put to work doing ship maintenance, which was never-ending. And when, after four hours on watch we went below, we strung up our hammocks and collapsed from fatigue.

In summary, some crossdressers had inside help – someone who knew their secret and helped them — or forced them — to maintain their ruse. But I believe a few enterprising females acted independently, deftly pulling the wool over their shipmates’ eyes. I base this on a phenomenon I call ”male pattern blindness” or “androgenic visual deficit.” Many ordinary objects are totally invisible to men who have this genetic trait, which has reached epidemic proportions in the twenty-first century. Maybe you know someone with this handicap? Someone who goes to the refrigerator for a bottle of beer but literally can’t see it lurking behind a jar of mayonaise, and calls to his wife, asking for help?

Having lived and worked with men, both at sea and on land (and having found countless bottles of invisible beer in the refrigerator) I think I know how a women could get away with it. Dress like a man (or a mayonaise jar) and pull your weight. Do your duty, don’t cause trouble, and chances are good your watchmates won’t see past your seaman’s slops and your sunburned, tar-smudged face. Apparently it worked for Hans Brandt — but watch out for open hatches.

In future blogs I’ll share more of my personal experiences as an ordinary seaman aboard HM Bark Endeavour – and I’ll discuss individual crossdressing seamen in more detail.

By a Yankee Moon, a novel about a crossdressing sailor and book three of the Patricia MacPherson Nautical Adventure Series, will be available in 2014. Barbados Bound and Surgeon’s Mate, the first two books in the series, are published by Fireship Press.

For more nautical posts please visit the rest of the fleet on this week’s blog hop, organized by Helen Hollick, author of Sea Witch Voyages, a pirate-based fantasy, and other historical fiction. A rising tide raises all ships!

September 5, 2013

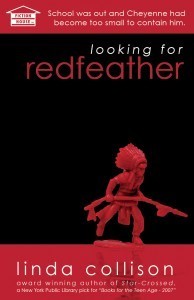

Looking for Redfeather – available for preorder at Smashwords

Looking for Redfeather is a road trip novel but it ain’t Jack Kerouac’s road trip!

Here’s a short youtube video shot on location in Denver, Colorado.

Available for preorder at Smashwords. For a limited time, get a free download of Looking for Redfeather on Smashwords with the coupon YY58Y. Trade paperback edition by Fiction House, Ltd., a small, independent press, to follow. The cool cover is by graphic artist Albert Roberts.

August 26, 2013

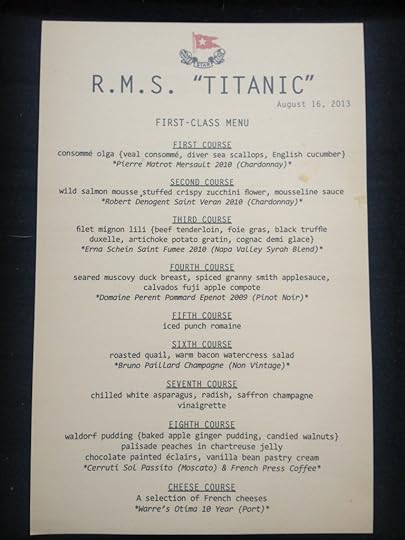

My birthday aboard the R.M.S. Titanic.

I dreamed I boarded the Titanic, a mile above sea level in Denver, Colorado. You know how dreams can be, mixing time and place in creative, seemingly impossible ways you never would have thought of on your own.

I dreamed I boarded the Titanic, a mile above sea level in Denver, Colorado. You know how dreams can be, mixing time and place in creative, seemingly impossible ways you never would have thought of on your own.

Only this wasn’t a sleeping dream, but a wakeful, dream-like Experience. This was my surprise birthday party (I’ll let you guess the year, I’d as soon forget it), dreamed up by Mr. Russell, my darling husband of nearly 21 years. Also known as Bob.

“Good evening Madam, and welcome aboard the Titanic.” A stout gentleman dressed in white coat greeted us with a bow as we stepped off the elevator on the seventeenth floor of Denver’s Daniels and Fisher Clock Tower, on Sixteenth Street in Denver, Colorado. The Clock Tower is a Sixteenth Street landmark I was familiar with, having passed it many times –yet I had never been inside. I had no idea it was a TARDIS. A time machine.

[An aside: Three hundred and twenty-five feet tall, the D & F clock tower, completed in 1911, was the tallest building west of the Mississippi for three years, until surpassed by the Smith Tower in Seattle. Designed by British-born architect Frederick Sterner and fashioned after the campanile of Piazza San Marco, Venice, the landmark edifice towered over the adjoining five- story Italian Renaissance Revival building that housed the Daniels and Fisher department store, which unfortunately was torn down in the urban renewal insanity of the 1960’s. The tower alone was saved from destruction and is on the National Register of Historic Places. The steel structured tower, faced with blond brick and terra cotta, features four Seth Thomas Clocks and a six-foot, 5,500 pound bell made in a Baltimore foundry, the largest bell west of the Mississippi. I was born in Baltimore. ]

In the ‘sixties William S. Pierson operated KBPI radio station out of the D&F building, with the antennae in the tower. When the building was condemned, Pierson refused to vacate. For five years he continued to operate out of the historic building, and according to author Mark A. Barnhouse, he climbed the 394 steps every day to wind the clocks. (Mark A. Barnhouse. “Denver’s Sixteenth Street”.)

Why didn’t he take the elevator? Maybe it had been shut down, because the building had been slated for destruction. Luckily the tower was saved by Denver preseravationists. Today, it houses Lannie’s Clocktower Cabaret, in the windowless basement, a cabaret owned by actress/singer Lannie Garret. There is also a residential apartment, purportedly for sale, listed by Sotheby’s…]

But back to our Titanic party, on the upper floors of this iconic portal to other times and places. I thought to myself, he’s done it. Bob has pulled it off! A themed party in my honor. A titanic birthday celebration with an ironic twist: The ship was grounded like the Ark, a mile above sea level, on the upper floors of an historic landmark. [another aside: This is the party I always wanted to throw in honor of Bob’s birthday – April 14 - the night the Titanic struck the iceberg, at 11:45. Now that he’s scooped me, I’ll have to settle for a Lincoln assassination party…]

Was it really a surprise? Well, not entirely. Being the clever, intuitive wife, I knew he was planning something special to celebrate my birthday this year. Excitement was afoot, as evidenced by a constant flurry of phone calls and text messages two weeks prior to the big day (August 16, for future reference…)

“Honey,” I suggested. “I know you’re planning to surprise me but you must give me some little clue. I need to know how to dress. Swim suit? Blue jeans and tee shirt? Fancy dress?”

“The latter,” he said. “And think, Edwardian Era.”

“Like, Downton Abbey?” (We’re both fans of the show.)

He nodded but refused to elaborate.

Oh good, I thought. I love to go time-traveling. Shall I be Lady Mary? Hmmm, it would probably be more age-appropriate for me to go as the Dowager. Then again, in keeping with my ancestry, perhaps I should go as Mrs. Hughs… But no – It’s my birthday, I’ll go as a Lady. Lady Linda. Even if I find my costume at a secondhand shop.

And so I dressed for the evening in clothing reminiscent of the period, showing off the elegant period necklace (definitely NOT from a second hand shop!) Bob had given me on the morning of my birthday, and wearing a fetching fascinator purchased at a hat store in Denver’s Larimer Square.

Greg Carl, President and CEO of Epicurean Catering met us in the lobby of the Clock Tower and beamed us up to the seventeenth floor –which had been magically turned into a choice selection of first class accommodation aboard the Titanic. Here we met Jessica Stapp, the party coordinator, and Kevin, maître d’ and historian, flanked by their mates, all dressed in white coat and tie. I was presented with a rose and baby’s breath wrist corsage, wished a happy birthday, and bid to come on board.

It felt like I was aboard a steamer as I was escorted to a narrow set of industrial steel stairs, complete with textured, nonskid steps, which looked and felt very much like a ship’s companionway. (Remember – we’re at the upper end of a 20-story, 34’x34’ tower.) Steam pipes and valves added to the atmosphere. Up we climbed to the nineteenth floor where we stepped up and over a bulkhead (which may have been a conduit encasing plumbing or electrical infrastructure) and low and behold, a bar was set up and I was offered a glass of rose champagne from white gloved hands and the contemplative sounds of a cello, expertly played, met my ears. Small cocktail tables were set with arrangements of red roses, white hydrangea, Queen Anne’s lace and summery fronds.

As if in a dream, Bonnie and Lorie materialized; my sisters who live on the East Coast, dressed in their Edwardian finery. Exclamations of delight, followed by champagne toasts and first-class canapés (oysters on the half shell, Colorado lamb carpaccio, foie gras torchon, and truffled celery mousse). We three Collison sisters, reunited aboard the Titanic; that was altogether unexpected!

The other immediate family members tricked in, two by two; the men, handsome and dashing in tuxedos with tails, and the women, beautiful in their interpretations of 1912 fashion. The cellist continued to play, working up a bit of a sweat in the mid-August heat, and we opened the doors on either side of the tower and a breeze slipped through and our parched throats were bathed in champagne.

Our maître d’, historian and story teller, Kevin Chavez, announced dinner and so we followed him down the companionway to the eighteenth floor where three tables had been set for eighteen guests in front of the clock face (photo). Here, the cellist was joined by two violinists and the enormous clock behind us was reminiscent of the Musee d’Orsay, a former train station in Paris. Very steampunkish, gears visible, black hands slowly revolving, a backdrop with a momento mori to the passage of time and the brevity of life.

The chef, Jenna Johansen, made an appearance to brief us on the nine course meal we’d be enjoying; a gastronomic extravaganza inspired by the last dinner served to the first class passengers aboard the Titanic that fateful night –and each course paired with the appropriate wine as chosen by sommelier, Annie Shoemaker. This had been Bob’s idea, to recreate the menu, based on the book “Last Dinner on the Titanic” by Rick Archbold and Dana McCauley. Mr. Chavez kept us riveted between courses, with stories about the Titanic, and Captain Arthur Henry Rostron, captain of the Carpathia, the Cunard line passenger ship who diverted course and rescued 705 of the survivors in lifeboats.

After dinner, down on Sixteenth Street, the younger generation waiting in their finery for horse-drawn coaches to take them to the after-party at the Oxford, we spied another character from the past. A girl with a typewriter, improvising poems. Just like an 18th century broadsheet balladeer, I thought. I must have one. Youngest son Matthew, sporting a top hat, white gloves and walking stick, paid the struggling artist a tuppence to compose his mother a birthday poem about sailing. Here is what she wrote:

Sailing

A cool wind

Breathes through me

And I am

The master

Of this vessal

Slicing harp-string

Destiny

Carrying

Me further

Along the water’s

Belly button.

by Abigail Mott

Denver, CO 8/16/13

August, 16. The last two digits of the year are 13, yes. But what century are we in? Surely not the twenty-first!

As the youngsters made off in their carriages, I was whisked away in my coach, which had turned back into a Subaru Outback, at the stroke of midnight. But no matter. I was with my Prince Charming. We had an amazing party and survived the doomed Titanic. What fortune!

Thanks to my husband Bob and my entire family for making this celebration possible. And to the Coordinator Jessica Stapp; Maître d’ and story teller, Kevin Chavez; Innovation Chef, Jenna Johansen; Captain, Joel Villescaz; sommelier, Annie Shoemaker; Chef, Elmer Pacheko –and 14 more unsung staff of Epicurean Catering, to serve 18 lucky guests.

August 11, 2013

Smugglers

DVDs, cell phones, chocopies and Kentucky Fried Chicken. Heroin, ecstasy, komodo dragons and rhino horns. Cigarettes, coltan ore (short for columbite-tantalite, a substance used in cell phones and other electronic devices). Human beings. Cold, hard cash. These are some of the most popular items being smuggled across international borders today (debiparna chakraborty. List Dose ).

Smuggling has been going on as long as there have been borders and duties to be paid. Black markets, free traders, rum runners, gun runners have influenced history in a big way. Boston, Rhode Island, New York; Americans built those cities on profits from evading taxes and duties on sugar and molasses. The notable John Hancock was a smuggler and The War for Independence was all about not paying our taxes.

England; 1801. Alaric Bond’s latest novel, Turn a Blind Eye, tells the story of Commander Griffin, an earnest young officer in His Majesty’s Custom Service who takes on the smuggling cartel of Newhaven. Not only did the English smugglers evade import taxes on wine, spirits, tobacco, and luxury items, they helped the enemy by shipping gold, wool, and other vital raw materials out of Britain and into the French coffers. During Britain’s Golden Age of Smuggling (roughly 1750-1830, Bond tells us), the nation was involved in a number of wars and numerous gangs as well as individuals carried on their business with the enemy, often bribing customs officials and preventative men paid to apprehend them.

I found all the smuggling business fascinating. Like, how they did it; all the little tricks of the trade. Bond includes a glossary of nautical and smuggling terms. I liked His protagonist, Commander Griffin. Griffin can’t be bought off. And he stands to profit from prize money for capturing smugglers. But he falls for a young woman whose family is involved in smuggling. And that creates tension. Not to mention, the smuggling mafia wants to kill him like they killed the last revenuer. Actually, this nautical historical novel reminds me a lot of a good Western, except instead of horses, you have cutters, smacks and sloops.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading Turn a Blind Eye – in part because my work-in-progress, By a Yankee Moon; book 3 of the Patricia MacPherson Nautical Adventure Series, is also about smuggling. The smuggling of sugar and molasses from the French West Indian plantations into the British colony of Rhode Island, in the mid-1760’s. Patricia, however, is not so honorable as Commander Griffin. But hey, a girl’s got to make a living. Even if she’s pretending to be a man.

August 4, 2013

Roy and Lesley Adkins on Jane Austen’s World

This is the summer for Jane Austen festivals; this, the 200th anniversary of the publication of Pride and Prejudice. I’d love to attend one of these celebratory functions where I imagine the other ladies dance the quadrille wearing custom made, empire waist gowns, and adorable bonnets, sip tea and quote J.A.. But of course as a servant I would be slaving away in the kitchen, the garret, or the stable. I wouldn’t be dancing or sipping or strolling in the garden with the proper guests. I’m pretty sure I would have been a servant. My English ancestors left the mother country for America in the 18th century, so they probably weren’t landed gentry – or else why would they have have left? Darn the luck!

Roy and Lesley Adkins have written a terrific book every Austen lover should read: A sweeping survey that sheds light on the wider world Jane Austen and her characters inhabited – the same world my ancestors, the servants, merchants, farmers and artisans, inhabited. Yes, the other 98 percent.

Jane Austen’s England will be released in the U.S. on August 15, 2013. The book was released in the U.K. earlier this summer as Eavesdropping on Jane Austen’s England. I’m a fan of Team Adkins and I was delighted to read an advance copy, which I reviewed on HistoricNavalFiction and Amazon.Co.UK.

The Adkins are authors of numerous books, mostly popular history, and many of them written together as a team. Jack Tar; Life in Nelson’s Navy, and, The War for All the Oceans: From Nelson at the Nile to Napoleon at Waterloo, are particular favorites of mine. Thank you Roy and Lesley (I think the credit goes largely to Lesley) for taking time from your busy season of appearances and book talks to answer my questions. Tell your publicist your American fans are clamouring for a stateside tour.

1. What are your personal connections with Jane Austen?

Our connections with Jane Austen probably have more to do with geography than literature. Lesley was brought up in Hampshire – Jane Austen’s own county, where the novelist lived most of her life and did much of her writing. Roy was born in the adjoining county of Berkshire and spent much of his childhood leisure time in Hampshire. Both of us are well acquainted with the area where Jane Austen lived.

Hampshire has a distinctive appearance, with rolling hills, woodlands and fertile valleys used for farming, intersected by winding, sometimes narrow lanes. One feature of the older buildings, including the churches, is the use of brick and flint (with thatch for roofs), since the county has no decent building stone. It is a gentle landscape, with no large cities or bleak moors, and somehow it appears a warm and friendly place, but perhaps that is because both of us have pleasant associations with the area.

2. What made you decide to write a book about life in England during Jane Austen’s time?

For our previous book, Jack Tar: Life in Nelson’s Navy, we explored the way of life of lower-deck seamen and lower-ranking officers during the period 1771–1815. The year 1771 is when Nelson first joined the Royal Navy as a captain’s servant, and the year 1815 is of course ten years after his death at Trafalgar, the very end of the wars with France and America. During the wars, many men were pressed into the navy against their will, but some did volunteer, and we wondered what sort of life the pressed men had left behind and why others willingly chose such a hard and dangerous life at sea. Was their situation on land really so bad that life in the navy was preferable?

It’s all too easy to divide history into completely separate units, such as naval, political and social history, but everything is intertwined, and we felt that it was an obvious progression to venture onto land. When researching Jack Tar, we constantly came across a great deal of material about life on land. Naval seamen were recruited ashore, often forcibly by the press-gang, and they had an impact when returning home after the wars. Similarly, thousands of people were directly employed in dockyards or in industries supporting the navy. With Britain being an island, it was inevitable that the navy was inextricably entwined with what happened on land. Perhaps we could have called the book Nelson’s England, but it was more appropriate to use Jane Austen as a constant thread – she lived from 1775 to 1817, which is much the same period as covered by Jack Tar, and in the end we chose the dates 1770 to 1817 for Jane Austen’s England. We hope it is a fitting companion to Jack Tar.

3. What do you hope readers will glean from Jane Austen’s England?

Jane Austen’s novels may be superbly crafted and timeless classics, but they focus on a very narrow slice of society. She herself said that her work was a “little bit (two inches wide) of ivory on which I work with so fine a brush as produces little effect after much labour”. We set out to explore all of England during her lifetime rather than the part of society about which she wrote. Her novels concentrate on the upper classes and barely mention revolutions, overseas wars and civil unrest at home. Her few surviving letters do touch on mundane subjects, but they do not mention the extreme poverty and hardship suffered by so many people. Even the servants who surround the upper-class characters in her novels are hardly mentioned.

Our book shows how ordinary people fitted into the period when she was alive and how her world and her fiction connected with the England around her. Many people think they would love to experience Jane Austen’s time, but not everyone could go to the fancy balls and dances – most people’s ancestors were more likely to have been the servants at these balls, doing all the laborious chores and working interminable hours.

Re-reading her fiction during the research for our book made it clear to us just how much is sketched or hinted at in the novels and how much you can miss if you don’t know the background to the characters and society she is writing about. Because Jane Austen was writing for a contemporary readership, there was no need for her to include explanations of everyday life and manners. In fact, we learn more about such matters from her letters. The aspect most often misunderstood about Jane Austen is that she was not a writer of historical novels but of contemporary satires. The publication of Northanger Abbey, which was finished in 1803, was delayed by the publisher, and Jane Austen was such a modern writer that in 1816 she added a note explaining that because of this delay, parts of the book might appear “obsolete” because “places, manners, books and opinions” had “undergone considerable changes”. Alas, the novel was not to be published until after her death the following year.

4. How do you get along as a writing team? Do you have specific responsibilities or does it vary from book to book?

Each book is different, but for this book (as with most others) we had to prepare a 20,000-word proposal for the publisher to consider before the book was commissioned. This gave us the basic structure of the book, and so we divided the chapters between us, a fairly amicable process! We each researched and wrote the first draft of those chapters, but even at that stage we would exchange material as our research threw up items that sat more comfortably in other chapters. There was, of course, far more material than could be squeezed into the book, and sometimes we would discuss the relative merits of different items while we were writing.

When one of us finished a chapter, a print-out was handed over and eventually returned, covered in comments and amendments in red ink. These elements were then changed or discussed, altered or rejected. When such roughly constructed chapters were all complete, they were assembled together and the long process of forming them into a coherent book began, with material being passed back and forth and discussed until we were happy enough with the result. We are never entirely happy with the books we write, but there comes a point when further changes are more likely to damage rather than improve the end result. That is the time to let the publisher see and comment on it.

We have written together as co-authors for so long that it does not seem anything out of the ordinary, but the place where we write surprises some people. Our house is too small, and so the living space is very restricted in order to make room for our office and library. The biggest room is used as an office, though bookshelves have infiltrated everywhere else, with another room filled with rolling stacks of books. Our office has a huge window on one side, with a view towards Dartmoor in the distance, so we can see for miles around. We are often asked if this is a distraction, and it is true that the landscape presents an ever-changing picture, but it is refreshing to look up from your work and gaze outside for a few minutes. And at night, there are very few lights visible, a reminder of Jane Austen’s era.

5. What advice do you have for others who are writing, particularly historical nonfiction?

Whatever you are writing, fiction or non-fiction, it is the people you are writing about that hold the most interest for a reader. Jane Austen’s novels are a good example of this point. She is not famous for her plots, and some people think that plot is her weakest element. What makes her novels great is the interplay between the characters. For historical fiction, with strong characters and plot, readers will forgive a few flaws. Not so non-fiction. Accuracy is essential, but non-fiction also presents different sorts of challenges than those encountered in writing fiction. Perhaps the biggest challenge is to make it readable, since factual writing can so easily become boring.

For anyone contemplating writing historical non-fiction with the intention of getting it published, then our advice is to ask “Who is likely to buy this book?”. If your subject is very specialised, then you either need to broaden its appeal in order to attract a mainstream publisher or else offer it to a genre or local history publisher. Too many writers think that publishers have a duty to publish their work, and yes, we’ve all been guilty of such thoughts. It’s also very irritating to be reminded that publishers and booksellers are businesses who need to make profits, but if you accept this premise (even if you think their business model is flawed), then it becomes easier to turn your idea into something that will attract the widest possible readership.

Writing a good book that appeals to many readers is only half the battle, since getting it published is very difficult. Publishing is in a state of flux at the moment, with small presses and self-publishing providing viable alternatives to the traditional publishing houses, but it remains true that even if you have written the most wonderful book, it is still largely a matter of luck whether you can find a publisher – Jane Austen herself encountered many problems when trying to have her books published. Most traditional publishers will not look at anything unless it has been submitted to them by a literary agent, and we really don’t have an answer on how to deal with that problem. As with all writing, if you think you are good enough, never give up! And never play by the rules. Your book is too important for rules.

6. How does Jane Austen’s England differ from other books about Jane Austen?

It seems to us that most other books about Jane Austen deal with the England of her time as if it was the country portrayed in her novels. Jane Austen wrote about a small section of society in a country that is a lightly sketched backdrop to the interaction between the characters. Our book Jane Austen’s England sets out to link two Englands – the England of Jane Austen’s novels, which focus on a privileged class of people, and the England that is barely mentioned in the novels – a country that is at war and gripped by austerity, one where women were still burned at the stake for counterfeiting and young people might be transported to America, or later Australia, for stealing a pocket watch. We describe the plight of children weaving fine muslin in the factories for the gowns of the wealthy; the women – even pregnant women – and children who toiled down the coal mines, producing coal for the fireplaces of wealthy homes (except for Fanny Price in Mansfield Park who was, of course, denied a fire in her room); the smock weddings and forced weddings that were a far cry from the romances of the Austen novels, as were the instances of selling wives in the marketplace.

Another topic is the dire state of medicine – how often in the Austen novels have we been slightly perplexed by characters taking to their beds in total panic after “catching a chill” – and yet ignorance bred fear. There was a belief in miasmas and bad humours, and for anyone with a chill, the best remedy might be to draw off some blood to eradicate the bad humours – the application of bloodsucking leeches was one favoured method. And dentistry was a horrifying proposition, something that Jane Austen mentions in her letters. False teeth were available at a price, though often they were made with teeth illicitly obtained from corpses by graverobbers.

We have woven a narrative from a variety of sources, all of them voices from two centuries ago, contemporary with Jane Austen herself. The previously unpublished archive material ranges from criminal trials of the most lowly pickpockets to the letters of Sarah Wilkinson detailing the progress of her baby girl and then her tragic death, while the diaries of William Holland let us see fascinating everyday details. He had a status similar to George Austen, Jane’s father, and their world was interconnected. At times, his diaries and other sources even throw additional light on the life of the Austen family itself.

7. What are your favourite venues for author talks and presentations?

Over the years we have given talks at a wide variety of venues, both large and small, and it is difficult to select particular favourites because they all have an individual character. The smaller venues are often very informal and provide plenty of time to meet readers, but there is also a particular satisfaction in talking to a large audience, and some are especially memorable.

We recently gave a talk at the annual weekend festival called “History Live!” organised by English Heritage at Kelmarsh in Northamptonshire, the biggest historical event in Europe. The lectures were held in a huge tent, organised by the BBC History Magazine, and ours was packed out and went really well. In the background, we could hear gunfire, because many other attractions were being held at the same time. We were able to see all sorts of displays and historical re-enactments (from the Romans to World War 2), as well as attend talks by other authors.

That is also one of the joys of the Telegraph’s Ways With Words Festival at Dartington in Devon. The medieval Dartington Hall is a beautiful setting for the festival, and this year the weather was glorious. We gave a talk about “Women in Jane Austen’s England”, and because we live nearby, we were able to attend talks given by other people. We could go on and on about the various venues, but perhaps we can just squeeze in the “Off The Shelf” festival at Sheffield. This is an October festival which has an autumnal feel about it that is strangely fitting for a town with such a great industrial heritage. We have a number of future talks lined up, details of which can be found on our website at www.adkinshistory.com (under “Latest News”). We have given talks all over Britain and even in mid-Atlantic on board a cruise liner, but the one thing we haven’t done is a lecture tour abroad – we are open to offers!

7. What next for the Adkins authors?

For the next few months our priority will be promoting Jane Austen’s England to bring it to the attention of as many potential readers as possible. Long gone are the days when you could simply write a book and expect the publisher and booksellers to publicise and sell it. Despite our best efforts, we are still contacted by people who have only just discovered and enjoyed books we published over a decade ago! It’s therefore far more important for us to concentrate on doing promotion work to make readers aware of Jane Austen’s England at this stage. There is nothing better than word-of-mouth recommendations – but this of course relies on people reading the book first before they can recommend it. We are also concentrating on writing articles for magazines, and we continue to send out our free email newsletters to anyone who signs up for them on our website at www.adkinshistory.com.

We do have many ideas for books and later this year we will sit down and start a proposal for a new book, trying to heed the advice we have given above. One thing we have learned over the years is that there is no point in rushing things. It’s best to move slowly into success than rush into failure!

Roy & Lesley Adkins

3rd August 2013

Hear Lesley Adkins on the BBC History podcast!

July 28, 2013

Young Writers in Dublin

I’m just back from Ireland, where I led a writers workshop for young adults at the VCFS International Scientific Meeting, a conference which brought together researchers, students, medical specialists and families dealing with the disorder from all over the world. One of my favorite researchers presenting at the conference was Dr. Tony Simon, of the U.C. Davis M.I.N.D. Institute. Simon directs the MIND Institute’s Cognitive Analysis and Brain Imaging Laboratory (CABIL, pronounced “cable”). CABIL’s mission is to investigate, explain and eventually treat the impairments in cognitive function experienced by children with neurodevelopmental disorders.

This year there were many activities designed for teens and young adult attendees, one of which was my writers workshop. We did some free writing, some journaling, and I’m pretty sure I learned more from the attendees than they learned from me!

The remarkable young people who took part in the workshop are all affected by a micro-deletion on the q arm of the 22nd chromosome; they all have 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, which presents in a myriad of phenotypes. Some have VCFS — velo-cardio-facial-syndrome, while others are affected in other ways, such as endocrine and immune disorders, learning differences and in many cases, impaired intelligence, as well as psychiatric disorders. Over 180 symptoms or anomalies have been identified, and no two people with the 22q deletion present exactly the same. In the past the disorder has been called by a variety of names, including VCFS, DiGeorge, Conotruncal Anomaly Face Syndrome, but the current trend is to call them by the genetic name, 22q11.1 deletion syndrome – 22q, for short.

My granddaughter has 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. The deletion happens during meiosis and it happens randomly. It’s not a question of mother’s age. 22q11.2 deletion is not uncommon; the occurrence is thought to happen 1:2000 births. Many people presently go undetected for some years, if they don’t have a severe cardiac malformation. My granddaughter has had numerous medical problems and surgeries, but her biggest challenges are cognitive, social, and emotional. Yet as a writer, she is already better than many people who have no cognitive impairments. Lauren writes vividly and evocatively to explore her deepest fears and anxieties. She is currently working on a novel called Stalking the Undead.

Although 22q11.2 deletion syndrome can’t be cured or even prevented, medicine can address most of the physical abnormalities. The psychiatric, the social, the cognitive problems are much harder to fix. Interestingly, many people with 22q deletion are extremely creative, even when they are intellectually impaired. Some, like my granddaughter, find themselves through language arts. The young writers who attended the workshop expressed themselves through poetry, essays, memoir and fiction. Each had her own voice and style. Each moved me deeply.

I used to feel like I lived in a dark hole

Where I felt cold, there was nothing I could hold…

– from a poem by Aine Lawlor titled Me Before, Me Now.

Aine is a young adult with 22q, who writes poetry and essays, plays the violin, bowls, dances the Irish jig, and inspires all who know her.

…Now I have a choice, now I

make people listen to my voice.

So right, Aine. And how to make people listen to our voice? To what we have to say? That is ever the writer’s dilemma.

…All I need to do is be honest and

be true.

Once again, the teacher learns from the pupil.

Internationally known photographer Rick Guidotti, has an eye for honesty and truth. Rick, beloved by all who know him, brings out the best in all of us. We were so fortunate to have Guidotti at the conference, capturing the truth and the beauty of those with differences. Check out this NBC clip about Rick’s work. Rick Guidotti re-interprets beauty

June 30, 2013

Navigators

Mau Piailug, navigator

“How shall we account for the Nation spreading itself so far over this Vast ocean?’ — Captain James Cook.

On the 17th of January, 1779, Cook piloted his ship Resolution into Kealakekua Bay on the island of Hawaii, writes Sam Low in Hawaiki Rising; Hokule’a, Nainoa Thompson, and the Hawaiian Renaissance (Island Heritage Publishing; 2013). On two previous voyages, Cook had explored deep into the Pacific, visiting the islands of New Zealand, Tahiti, Tonga and Samoa and everywhere he recognized the same lilting tones of the Polynesian language. He was a sailor-scholar who surmised these far flung islanders shared a similar culture.”

Captain Cook encountered large double canoes that sailed circles around his own ships. On his first voyage to Tahiti in 1769, he met Tupaia, a high priest and navigator who guided him through the Society Island chain. From memory, Tupaia described more than a hundred islands stretching from Tonga in the west to the Australs in the east — a distance of twelve hundred miles. Tupaia told Cook that navigators from Ra’iatea had sailed for twenty days or more aboard their large double canoes, called pahi, and in 1769 Cook had written in his log ‘In these Pahee…these people sail in those seas from Island to island for several hundred Leagues (about 600 nautical miles), the sun serving them for a compass by day and the Moon and stars by night. When this comes to be prov’d we shall be no longer at a loss to know how these Islands sying in those seas came to be people’d.” (Low, 19-21.)

Hokule’a, the tradional Polynesian voyaging canoe, has over the past thirty years or so, made numerous voyages all over the Pacific Ocean, without instruments and on wind power alone, proving that Polynesians could have settled the Pacific intentionally, and that their vessels were capable and their navigational methods accurate. Indeed, that is the accepted theory now. Polynesians, orginally from southern Asia, peopled the Pacific Islands over many hundreds of years. Theirs is not the story of two guys out fishing on a raft who get blown off course and end up in Hawaii, but of purposeful voyagemaking and emigration with navigators, food and fresh water, and women aboard. Thor Heyerdahl’s thory of American origins “seems no longer tenable in face of the accumulated evidence from archaeology, word analysis, studies of introduced plnats and animals, and other data, says David Lewis in We the Navigators; the Ancient Art of Landfinding in the Pacific (University of Hawaii Press; 1972).

Today’s traditional navigators were taught by Mau Piailug, a Micronesian navigator from Satawal, who passed along a dying art before he himself passed on in 2010. Some of today’s Hawaiian traditional navigators who studied with Mau include Nainoa Thompson, Chad Baybayan, Shorty Bertelmann, Bruce Blankenfeld and Chad Paishon. The practice has been revived and proves that humans can intentionally cross an ocean without use of compass, quadrants, charts or other western technology.

Captain Cook, an astute observer and admirer of Polynesian seamanship, would smile knowingly.

Sources:

Hawaiki Rising; Hokule’a, Nainoa Thompson, and the Hawaiian Renaissance Sam Low ( Island Heritage; 2013).

The Explorations of Captain James Cook in the Pacific as told by selections of his own journals 1768-1779. Ed. Grenfell Price (Dover; 1971)

Tupaia; Captain Cook’s Polynesian Navigator. Joan Druett (Praeger, 2010).

Voyage of Rediscovery; a cultural odyssey through Polynesia. Ben Finney (University of California Press; 1994.)

We, the Navigators; The Ancient Art of Landfinding in the Pacific.( second edition). David Lewis (University of Hawaii Press; 1994)

![2013-Nautical-Blog-Hop-small[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1381040327i/3939294.jpg)