Linda Collison's Blog, page 18

March 23, 2014

Writing on a Ranch in the Rockies; Antidotes to Isolation

Mary Kurtz is one of the Steamboat Writers, a group of essayists, fiction writers, academics, and poets who have been meeting weekly for more than twenty years to share their works-in-progress and receive feedback from one another. The group, affiliated with the Steamboat Arts Council, also hosts an annual writers conference in Steamboat Springs, Colorado.

I always look forward to hearing Mary read. Whether poetry or prose, she writes sparely, yet vividly. Her words quietly tear at the heart and connect us through our pain and isolation. Thanks, Mary, for contributing to my series, How We Write.

Antidotes to Isolation

by Mary Kurtz

I am often asked by out-of-town guests if living on a ranch is lonely. My answer is usually the same:

I am often asked by out-of-town guests if living on a ranch is lonely. My answer is usually the same:

“Not any lonelier than anywhere else.” I’ve long believed that loneliness is relative. It can occur in the

middle of Manhattan. However, if anyone were to ask me if the writing life feels lonely, my answer

is “yes”. While I find solitude necessary to my writing process, I often need to break away from the

narrow focus of what’s on my desk. On any given day that might mean it’s time for a walk with my dogs,

a hike on a nearby hill or in the winter, a snowshoe. I find the fresh air an antidote to the isolation.

However, on a fairly regular basis, I find the need for more potent antidotes.

So, I participate in local and regional conferences and writers groups and find the isolation of my desk

dissolve in those professional connections. In 2013, I attended the Taos Writers Conference in New

Mexico. While there I was fortunate to hear Priscilla Long from Seattle, Washington. A writer, teacher,

and scientist she enthusiastically encourages writers to get to the desk, to sit down and start writing.

While I’ve self-published a collection of essays, I struggle some days to justify my writing time. Living

on a ranch, particularly in the summertime, I find it hard to sit at my desk knowing there is always

something to be done outside. So, I was looking for support at this conference for my daily writing

practice. Thankfully, Priscilla was helpful.

In her book, The Writers Portable Mentor: A Guide to Art, Craft and the Writing Life, she shared a

writing technique I use frequently in my daily writing. She refers to it as the “Word Trap.” This exercise

can be used as a simple free write or as a brain-storming exercise when a writer is looking for inspiration

for a poem, a character, or essay theme. To begin, at the top of the page write a word, say “garden”.

Then write every thought that comes to mind when you think of that word. I find that one, two, and

three words come at first, and then they easily become phrases that grow as the writing goes on down

the page. The free association is a gift because it isn’t judgmental and easily invites the writer to a

daily practice. So, now I have both the memory of Priscilla’s encouraging voice and one of her helpful

techniques to use when I’m struggling alone to sit at my desk.

I also find support from participating in writers groups. One local group offers feedback on my

writing; and another supports authors like me who publish their work independently. And lastly, my

membership with writing groups like Women Writing the West offers contact with regional and national

female authors.

As a result of attending WWW Conferences, I’ve developed relationships with authors who’ve answered

questions, offered encouragement and in 2012 invited me to submit my writing for an anthology

project. Now two years later, my essays, “Bugsy” and “Daddy’s Girl” will be included in the anthology,

Ankle High and Knee Deep: Women Reflect on Western Rural Life, to be released in June, 2014 by Two

Dot an imprint of Globe Pequot Press. Without attending the WWW Conference in Seattle that year I

wouldn’t have met the future anthology editor, Gail Jenner, nor would I have been offered the invitation

to contribute my writing—this all over a friendly glass of wine during a networking session one evening.

So, while the real work of my writing takes place in a quiet office in my son’s old bedroom on our ranch,

neither my writing nor I would be known in a wider world if it weren’t for the connections I have made

through writing groups and attending conferences. My participation is affirming each time I read aloud

and ask for critique in writers group, each time I network at a conference and each time I hear the

stories of other writers. In the exchange, I know I share common experiences within the larger writing

community. For me, this kind of reassurance is the strongest antidote to the isolation of the writing life

for it brings me back to a place where I feel as though I belong.

~~~~~~~~~~

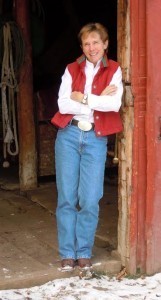

Mary Kurtz and her husband, Peter, raise cattle, hay, and quarter horses in northwestern Colorado on

their ranch outside Steamboat Springs, Colorado. She finds inspiration for her writing in their daily

ranch living and in the beautiful landscape of the Elk River Valley. Mary’s award-winning first collection of essays, At

Home in the Elk River Valley: Reflections on Family, Place and the West invites readers into the history,

natural world and community of the Elk River Valley. She has contributed to Farm and Ranch Living, the

Trail and Rider Magazine, and the Country Woman Magazine.

The soon-to-be released anthology, Ankle High and Knee Deep: Women Reflect on Western Rural Life is

available for pre-order at www.amazon.com.

Please visit Mary at: www.marybkurtz.com

March 16, 2014

Anna Belfrage talks of time travel and other writing secrets

How We Write.

Today’s guest post on How We Write is by novelist Anna Belfrage, who lives in Sweden. Anna and I have connected on Facebook – and quite possibly in other lifetimes. Here’s a glimpse into her fantastical writing process:

Writing your protagonists

Writing your protagonists

One of the benefits of writing fiction is that you can make things up. (Duh!) In my case, I have long nurtured a dream to time-travel, and once I came to the conclusion this was not about to happen for real – major, major disappointment, let me tell you – I decided to write about it instead. So I whipped up a major lightning storm that propelled my female protagonist in The Graham Saga, Alex Lind, three centuries backwards in time. I have a thing about the 17th century; all that political upheaval, all that religious unrest – definitely a time when a lot of stuff happened.

Dear Alex is not as adequately grateful as she should be. After all, here she is, thrown into a life full of adventure and excitement, very far from her previous rather humdrum existence as some sort of computer whiz.

“Humdrum?” she squeaks (she does that when she gets upset).

“Humdrum,” I insist. Well, okay, humdrum may be pushing it a bit, what with her horrible experiences in Italy and Ángel and—

“I don’t want to talk about that!” Alex interrupts. No; she wouldn’t, would she? One could actually say I did her a favour, propelling her out of a time so full of nasty characters, and yet the woman keeps complaining! No showers, no in-door plumbing, no newspapers, no TV… Sheesh! What about the benefits of unpolluted air? Of living in a time where so much of the world was unexplored? Alex gives me a look that should reduce me to a little pile of gooey matter and tells me that on top of it all, she is now relegated to being a second-class citizen – if at that – in a world where men control everything, at least legally. Hmm. I must concede she has a point there.

Alex did not leap out of my head like a modern day Athena, fully formed into the character she now is. She came in bits and pieces, evolving from a rather fuzzy image of someone with a lot of curly hair to a woman with more than her fair share of courage – and a capacity to adapt. Which is why, when I drop in to check on her, I am met by a woman quite indistinguishable from her new contemporaries – at least on the outside…

Alex sits down on the bench and looks at me. She’s in long skirts, a bodice that is a bit too tight over a rounded bosom, a neat white collar and an apron that is in serious need of a wash. The colours suit her, the muted russet of the bodice brings out the bronze and copper strands in her dark hair. Two blue eyes meet mine, brows pulled together in a frown.

“Still look the same, do I?” she says.

“More or less.” After all, the first time I saw her she was in jeans.

Alex scrapes at a stain of something that looks suspiciously like dried blood on her apron and sighs.

“Sometimes I no longer even notice. First few months here I’d change aprons every morning, but now …” She shrugs. “Same thing with all my clothes; I wear them well beyond modern hygiene standards.”

I can smell that. At least she bathes regularly, a major difference to most of the people in the here and now.

“Do you think it was meant somehow?” I ask her. “You know, your plunge through time.”

“Like some sort of predestined fate? Don’t be ridiculous! It was more a matter of wrong time, wrong place.”

“Yes,” I say. “I dare say you regret taking the shortcut over the moors.”

“I was late.” Alex gnaws her lip. She takes off her cap and scratches vigorously at her hair. I wonder if she might have lice, but refrain from asking. “It was either the moor or being flayed by Diane for being late. The moor seemed a better option.”

“So, do you regret it?”

“Well, I didn’t exactly plan on time travelling, did I?” She laughs, shaking her head. “I guess nobody does. Kind of incredible, all in all.” She grows serious. “Had someone told me that by taking the road over the moor I might end up yanked out of my time, I would never have done it – assuming I believed anyone who told me something so utterly ridiculous.”

We share a chuckle. Alex has no patience with people professing an interest for the occult – no matter in what shape. And yet here she is, living proof that sometimes weird things happen.

“I’m pretty glad no one did,” she says a few minutes later. “Otherwise, I’d never have met Matthew.” She gazes out of the small window, her mouth softening into a faint smile.

“So he’s worth it, huh?”

“He’s worth some of it,” she fires back. “Some of the experiences I’ve had here, I’d rather have been without, thank you very much.”

“Umm.” I like putting her through precarious episodes.

“Yeah, I kind of notice that.” Her blue eyes bore into me. “It’s because you’re jealous.”

“Who? Me?” I feel caught out. Of course I’m jealous! She’s young, he’s gorgeous, life is crammed with adventure – okay, okay, perhaps excessively so at times, but still. She laughs and shakes her head at me, and I feel my cheeks flaring into a bright, tomato red.

“We’re not here to talk about me,” I say in an effort to retake control over the situation. “It’s you people want to know about.”

“Five foot eight, dark hair, blue eyes, good tits… well that’s it, no?”

I roll my eyes at her. “Your inner qualities, Alex!”

“Opinionated and stubborn to a fault,” Matthew says as he enters the kitchen. He grins at Alex. “Quite the hellcat, and she kicks like an unbroken horse.” His mouth softens, he extends his hand and Alex sort of floats upright and levitates towards him. Okay, okay; of course she doesn’t – but is sure looks that way.

“I’m right glad you chose that shortcut,” he says.

“So am I,” she says, “most of the time.”

“Not always?” he asks, something dark colouring his voice.

“Almost always,” she says.

“Hmm.” He grips her chin and raises her face to the light. He kisses her, a mere brushing of lips no more, and I pretend a major interest in my pencil.

“Not always?” he asks again.

“Always,” she says in a voice so breathless it makes me smile. Seeing as they’re entirely oblivious to my presence, I leave them to it, gliding as soundlessly as possible from the table to the door.

***

Anna Belfrage is the author of five published books, all part of The Graham Saga. Set in the 17th century, the books tell the story of Matthew Graham and his time-travelling wife, Alex Lind. Anna can be found on amazon, wordpress, facebook and on her website.

See you in the 17th century?

(

March 14, 2014

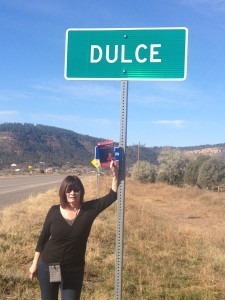

Looking for Redfeather a Foreword Review’s Book of the Year Finalist

I’m pleased to announce that Foreword Reviews has chosen Looking for Redfeather as a finalist for the YA Book of the Year 2013 Award! Looking for Redfeather is now available through Ingram Spark, for bookstores and libraries. Order it from your local indie bookstore or online from Amazon or Barnes & Noble.

Looking for Redfeather was also awarded runner-up in the Wild Card category at the Los Angeles Book Festival.

Thanks to my husband, Bob, for all his support, and to the Steamboat Writers for their supportive feedback during the writing process.

March 10, 2014

Writing process? What process? A blog hop tour

My Writing Process

Judith Starkston, author of Hand of Fire (Fireship Press, September 2014) invited me to participate in this blog hop tour and answer four questions about my writing process. I have to warn you, it’s a bit of a mess.

1) What are you working on?

My mother used to warn me about having too many irons in the fire, as she called it. Like many writers, I’ve got several projects going on, in various stages. For example, I’m working on the third book of the Patricia MacPherson Nautical Adventures – my historical novel series. I’m also looking for an agent to represent “Water Ghosts,” a contemporary YA psychological thriller with paranormal and historical elements, set at sea. If I don’t find a good agent I’ll publish it in the indie world. “Looking for Redfeather,” a contemporary coming-of-age road trip novel I published under the Fiction House imprint, is now being written as a stage play. I had my first reading on Sunday. Very fun and energizing to work with talented artists on the stage adaptation. I have some other novel and short stories brewing on the back burner.

2) How does your work differ from others of its genre?

Patricia MacPherson Nautical Adventures is one of the few, if not the only, nautical historical series that features a female protagonist who is living as a man in the 18th century. I’m exploring some new territory in book 3, which has been a long time in the making, but then speed has never been a part of my writing process. It took more than six years for Star-Crossed (Knopf; 2006) to be written and published. Star-Crossed is the novel that inspired the Patricia MacPherson Nautical Adventures, and was chosen by the New York Public Library to be among the “Books for the Teen Age – 2007.” Fireship Press has re-published Star-Crossed as adult historical fiction, titled Barbados Bound, the first book in the series, followed by Surgeon’s Mate.

3) Why do you write what you do?

I write for my own pleasure, and to explore possibilities. I write to try to understand.

As far as my Patricia MacPherson historical novels are concerned, I was driven to write the first two because I think women have been largely misrepresented, historically. I have a passion for history and a love for my primary setting – sailing ships and port towns. And because three weeks working as a seaman aboard HM Bark Endeavour, a replica of Captain James Cook’s 18th century ship, taught me that women can indeed do men’s work aboard ship. History has overlooked the significant numbers of women who sailed aboard ships during the great age of sail, often as wives of warrant officers and girlfriends of the seamen, sharing their hammock and their rations.

4) How does your writing process work?

Oh, it’s mayhem. It’s chaos. Sometimes daring. Mostly, slow. Definitely not linear. Each manuscript I learn something, learn many things, and the process changes. One thing that remains constant: I write the heart of the story first. Something grabs my imagination – a setting, a character, a bit of dialogue, an event – and then, if it becomes an obsession, I turn it into a story. Somehow. Lots of rewrites, an enormous amount of rewriting. But in the first crucial draft I try to capture the beating heart, then in the second few drafts I build the structure. The bones. After that, I spend many months fleshing it out and dressing it up.

Next Monday, March 17, pop on over to historical novelist Janet Oakley’s blog and Alaric Bond’s blog. Janet is the author of the acclaimed novel Tree Soldier, set during the Great Depression in a civilian conservation camp. Alaric Bond writes nautical fiction set in the age of sail,including The Fighting Sail series, and other stand-alone stories.

Both are writers whose work I admire.

March 7, 2014

Writers — why not take the scenic route?

Turning my novel, Looking for Redfeather, into a stage play has been an interesting challenge — and fun. I had to look at the story as a series of distinct scenes. Except for the challenge of conveying a character’s thoughts, writing Redfeather as a play was in some ways easier than writing it as a novel.

The scenic approach can be used in prose as well as theater, I’m learning. A scene in fiction might be described as that action which takes place in a single setting; a single place in time and space. A novel might be written as a series of scenes, each one critical to the bigger picture. The whole story is greater than the sum of its parts, yet an effective scene is complete in and of itself, with a beginning, middle and end.

When my historical novel-in-progress (Book Three of the Patricia MacPherson Nautical Adventures) got becalmed in a nameless sea, it helped me get underway again by imagining the story in terms of distinct scenes. Now as I write I’m asking myself these questions:

1.Where in the world are you, Linda? And when? And why? What is important about this particular setting?

2. What happens in this scene? Are the characters developed or the plot advanced?

3. What do I want the reader to discover or experience in this scene?

4. Whose scene is this? Protagonist or antagonist? Or is it a secondary character’s scene? Even if I’m writing from the omniscient POV, one character might want to steal this scene. Let her.

5. Can this scene be effectively combined with another scene — or might it be more effective divided into two or more scenes?

6. A well-developed scene includes description, narration, dialogue, interior dialogue, and action. Characters observe, talk, think, feel, act, and react. How can I enrich, fill out, or balance out this scene? Or does it need to be pared down closer to the bone? Does every word count?

7. Is this scene necessary to setting, character development or plot advancement? Or is it merely a preliminary sketch? Am I still in the free-writing stage, looking for the essence?

8. If this is a necessary scene, how can I punch it up? Bring it to life? Make it more vivid? More important to the story as a whole? Get out the toolbox: Livelier verbs, tighter descriptions, snappier dialogue, deeper interior thoughts and feelings? Does something more need to HAPPEN in this scene? What’s the worst that could happen right now? What bad choice might my character make? What terrible mistake? What if I allow that to Happen?

This scenic approach might not work for you, but it has gotten me back on course with my novel. Please share what works for you!

Watch Looking for Redfeather, the book trailer. Enjoy the scenery!

March 3, 2014

Barbara Kyle on Writing a Series

I had the pleasure of meeting Barbara Kyle in person at the Historical Novel Society Conference in London, 2012. And what a lovely person she is!

Barbara writes both historical and contemporary fiction, leads workshops and speaks about writing. She studied theater and acted professionally for twenty years, mostly in television. No wonder she’s able to create such vibrant characters and deliver such action on the page! Barbara’s contemporary thrillers include Entrapped and The Experiement. In 2008 Kensington Books published Kyle’s first historical novel; set in King Henry VIII’s court, The Queen’s Lady became the first in a series of six novels – and counting! Barbara and her husband also enjoy sailing; she and I are connected through writing and water.

Here is Barbara Kyle sharing her experience and advice on writing a series…

How Fenella Became a Star: Thoughts on Writing a Series

by Barbara Kyle

Publishers love series. No wonder. The Harry Potter empire has sold more than 400 million

Publishers love series. No wonder. The Harry Potter empire has sold more than 400 million

books. Nancy Drew? The 175 installments of the beloved mystery series have had sales of over

200 million. Of Twilight’s four books more than 100 million copies have been sold.

Publishers love series because readers love series. Just like TV, where viewers eagerly welcome

the same characters into their living rooms week after week—be it Downton Abbey, Breaking

Bad, Game of Thrones, or The Good Wife—readers of series by master storytellers like George

R. R. Martin, Diana Gabaldon, and Bernard Cornwell have the same addiction. They get to know

the continuing characters so well they can’t wait to find out what happens in the next book.

What happens in the next book can sometimes surprise the author. The surprise for me was

Fenella Doorn.

Fenella is the heroine of my new historical thriller, The Queen’s Exiles. She’s a savvy Scottish-

Fenella is the heroine of my new historical thriller, The Queen’s Exiles. She’s a savvy Scottish-

born entrepreneur who salvages ships. This is the sixth book in my Thornleigh Saga which

follows a middle-class English family’s rise through three tumultuous Tudor reigns. In Book

4 Fenella played a small but crucial role in the plot, and then I forgot about her. She didn’t

appear in Book 5. But when I was planning Book 6, and focusing it on one of the series’ major

continuing characters, Fenella sneaked up me. A warm-hearted, determined, courageous woman,

she’s also rather cheeky and she insisted that I include her in the new story. She reminded me

that she’d had past connections with two exciting men in the series, Adam Thornleigh and Carlos

Valverde, which promised some dramatic sparks.

So, I did more than include her in the new book. I made her its star.

That can happen when you write a series —a secondary character can take over. I was glad

Fenella did. She offered me an opportunity to create a complex, admirable woman who doesn’t

fit the ingénue heroine so common in historical fiction. She’s not a young thing; she’s thirty.

She’s not a pampered lady; she rolls up her sleeves running her business of refitting ships.

She’s attractive but not a smooth-faced beauty; her cheek is scarred from a brute’s attack with a

bottle ten years ago. And she’s not a virgin; she was once the mistress of the commander of the

Edinburgh garrison (he of the bottle attack). In other words, Fenella is my kind of woman.

But making her the star of the new book in my series meant some serious recalibrating. How

could I fit her into the Thornleigh family? Writing a series opens up a vista of opportunities but

also a minefield of traps. I’ll share a few with you here.

1. Every Book is New

Don’t assume that readers have read the previous books in the series. My agent always reminds

me of this when I send him the outline for a new book in the Thornleigh Saga: “Many readers

won’t know what these characters have already been through.” So, each book has to give some

background about what’s happened to the main characters in the preceding books, enough to get

new readers up to speed. However, you can’t lay on so much backstory that you bore readers who

have followed all the books. Getting the balance right is tricky.

I like the way episodes in a TV series start with a helpful recap: “Previously on Downton

Abbey…” It’s perfect: it refreshes the memory of viewers who’ve seen the previous episodes, and

is just enough to tantalize those haven’t and bring them up to speed. I wish I could have a nice

announcer give a recap at the beginning of my Thornleigh books! The point is, each book in a

series must stand on its own. It has to be a complete and satisfying story for any reader.

2. Create a Series Bible

Before writing full time I enjoyed a twenty-year acting career, and one of the TV series I did was

a daytime drama (soap opera) called High Hopes. The writers on that series kept a story Bible: a

record of the myriad details that had to be consistent from show to show concerning the dozens

of characters. It’s a wise practice for the writer of a series of novels, too.

My Thornleigh Saga books follow a family for three generations (and counting), so it’s easy

to forget facts about a character that were covered three or four books ago. That’s why I keep

a Bible that keeps track of the characters’ ages, occupations, marriages, love affairs, children,

ages of their children, homes, character traits, and physical details like color of hair and eyes . . .

and missing body parts! Richard Thornleigh loses an eye in The Queen’s Lady, Book 1 of the

Thornleigh Saga, yet in later books I would often start to write things like, “His eyes were drawn

to …” So I keep that Bible near.

3. Consistency Can Yield Rewards

When I had a brute cut Fenella Doorn’s cheek in Book 4, The Queen’s Gamble, I never expected

Fenella to reappear in a future story. Two books later, when I brought her back to star in The

Queen’s Exiles, I could not ignore the fact that she would have a sizable scar on her cheek. So I

used that scar to enrich her character. She’d been a beauty at eighteen, relying on men to support

her, but when her cut face marred her beauty she realized that it was now up to her to put bread

on the table and clothes on her back. I made her ironically aware that the scar freed her from the

bonds of beauty; it made her independent. And she became a successful entrepreneur.

4. Let Characters Age

It’s hard for readers to believe that a detective can fight off bad guys like a young stud when

the decades-long timeline of the books he appears in make him, in fact, a senior citizen. J. K

Rowling was smart. She let Harry Potter and his friends grow up. I’ve enjoyed doing this with

my characters. Through six books I’ve taken Honor Larke from precocious seven-year-old to

wise grande dame as Lady Thornleigh. Her step-son Adam Thornleigh’s first big role was in

The Queen’s Captive where he was an impetuous seafaring adventurer, but by the time of The

Queen’s Exiles Adam has become a mature man, a loyal champion of his friend Queen Elizabeth.

He has been through a loveless marriage, adores his two children, and falls hard for Fenella.

5. Embrace Cliff-hanger Endings

Each book in a series must be a stand-alone story, with an inciting incident, escalating conflict

developments, and a satisfying climax. But if you can end each book by opening up a new

question for the characters that will be tackled in the next book, readers will love it and will look

forward to getting the next in the series.

***

Barbara Kyle is the author of the acclaimed Tudor-era Thornleigh Saga novels. Over 425,000

copies of her books have been sold in seven countries. Her latest, The Queen’s Exiles, will

be released in June 2014. Barbara has taught writers at the University of Toronto School of

Continuing Studies and is known for her dynamic workshops for many writers organizations and

writers conferences. Before becoming an author Barbara enjoyed a twenty-year acting career in

television, film, and stage productions in Canada and the U.S. Visit www.barbarakyle.com where

you can watch an excerpt from her popular series of online video workshops “Writing Fiction

That Sells.” The first workshop is free!

Follow Barbara on her website Facebook author page and on Twitter

March 2, 2014

3 stories by Linda Collison free on Smashwords this week

It’s March Madness all week on Smashwords! My contemporary coming-of-age novel, Looking for Redfeather, and my two sick nurse short stories, Holiday on Planet Jolieterre and Friday Night Knife and Gun Club are free for download from Smashwords. The covers of all three of these stories come from the creative mind and talented hand of Albert Roberts, a time traveler I met on Facebook.

It’s March Madness all week on Smashwords! My contemporary coming-of-age novel, Looking for Redfeather, and my two sick nurse short stories, Holiday on Planet Jolieterre and Friday Night Knife and Gun Club are free for download from Smashwords. The covers of all three of these stories come from the creative mind and talented hand of Albert Roberts, a time traveler I met on Facebook.

Help yourself to a slice of my imagination pie. Go on, have another! Complements of the chef. Enter RW100 at checkout. A review on Smashwords, Amazon (USA, CA, UK, AU, or Planet Jolieterre) would be greatly appreciated. Linda Collison on Smashwords.

For those who follow my historical fiction, I’m working on book 3 of the Patricia MacPherson Nautical Adventures, published by Fireship Press. The time travel involved in writhing histfic means it takes longer to write, edit and produce. While you’re waiting, why not time-hop to the 21st century, and beyond?

Later this month cover artist Albert Roberts will be a guest here on Sea of Words, as his alter-ego Dr. Roberts of HMS Acasta. Tomorrow my guest will be historical novelist Barbara Kyle, giving us some tips on writing a series on the thread “How We Write.” If only I had read this BEFORE I started writing mine…

Later this month cover artist Albert Roberts will be a guest here on Sea of Words, as his alter-ego Dr. Roberts of HMS Acasta. Tomorrow my guest will be historical novelist Barbara Kyle, giving us some tips on writing a series on the thread “How We Write.” If only I had read this BEFORE I started writing mine…

February 28, 2014

It’s all in the details

Character, plot, and setting. These are the three main building blocks of fiction. What connects these three components and brings them to life are the details.

But which details do we include in our stories?

In this photo taken several years ago, I’m aboard the Maine-built Lynx, a clipper schooner inspired by the 1812 American Privateer Lynx, built in Fells Point, Maryland, my home state. Here we are on an afternoon sail, just outside of Kawaihae Harbor, on Hawaii Island. (Consider the details in these two sentences: perhaps too many? Or, irrelevant? Does the reader really want or need to know where I was born? Do they care the replica vessel was built in Maine? Is that important to my story? Does it give the ship life?)

So many details, so many components, can be discovered in this single photograph. Hemp lines, sun-bleached blocks, and the polished wood rail. There’s the sweaty, sunburned, bare-chested man behind. There’s the soft Kona breeze against my hair and the side of my face….the rough scratch of hemp against my bare hand on the brace. The creaking of blocks, the swish against the hull as the ship makes way through the water. I am feeling too warm under the white cotton jacket I wear to protect my skin from the sun. And although I look confident, I’m fighting a feeling of queasiness – a rolling of the stomach that coincides with the roll of the ship on the ever-present swell.

Which of these descriptions brings the story to life?

Typically, when I write the first draft of a story, I don’t include all the details. The first time through I hear conversation, I hear interior thoughts. I write what happens to the characters – the plot. What I end up with is little more than a narrative outline of the story – with dialogue and motivation. It’s only on subsequent drafts that I go back and get inside each scene, page by page, using my memory and imagination – and often research – to flesh out the details.

Once I really get inside the scene, it’s easier to experience the details. I ask myself, what am I seeing, hearing, tasting, smelling, feeling? What am I wearing? What kind of day, or night, is it? What is going on in the larger world at that time and place, that affects me? What phase was the moon in?

Seriously, moon phases for past dates, can be worked out! Tables exist! When I wrote Star-Crossed I became obsessed with moon phases; I wanted to know when the moon was full. My scientist husband researched this for me, God love him! Does historical fiction need to be that exact? No! But I was absorbed with that detail.

In my contemporary fiction as well as my historical fiction, I like to visit the places I’m writing about, whenever possible. Often the setting itself initiates the story. I record details in photographs, in a journal, and sometimes on random scraps of paper. I read books and first-hand accounts about the places and events in my story. I listen to music associated with the time period and even dress like my protagonist. Method writing!

After I pile on the descriptions, later revisions involve cutting out extraneous detail and searching for more poignant description. Characters can drown in too much setting. Too many props distract. But how does a writer know which details to cut? That’s where the art of writing, rather than the craft comes in. And voice. We could all write the same plot with the same characters, yet it wouldn’t be the same story at all. What we choose to describe, the details we include, are part of our perspective. Our voice.

Writing exercise: Take five minutes to describe the place where you are right now. Using your five senses, explore your surroundings in minute detail. Include your feelings. You can easily come up with a wealth of information, almost a list, on the page. The challenge for the author is choosing the telling detail. Which single detail or description brings your scene to life? Which one brings a vivid image or sensory experience to mind? Consider cutting the others to make that one stand out. This is a decision only the author can make.

Here’s a passage from Looking for Redfeather (pg. 53) that shows what details I felt were important:

Here’s a passage from Looking for Redfeather (pg. 53) that shows what details I felt were important:

The blast of cool air felt refreshing against their skin, and the smell of bacon frying was tantalizing. Big, old-fashioned, over-stuffed booths, the bright color of taxi cabs. Eighties music filled the room. Foreigner singing, “I wanna know what love is” — that’s just how they felt! Lyrics and music composed and recorded long before they were born had been given new significance. Everything they saw and heard seemed important, meaningful, created for them alone.

“Breakfast is on me, my friends,” Chas said largely. “Have whatever you want.”

They took him at his word, ordering as if money were no object, as if they had just returned, triumphant, from a long and arduous journey. A wait person brought them coffee (a man or a woman, they weren’t sure), and they admired the sinewy arm, a panorama of ink from wrist to armpit. Chas felt like he was in some kind of spontaneous street performance and everyone they saw was a character.

Bacon — a pile of bacon, stacked like firewood — and has browns, steaming beneath the brown crust. Heaps of fluffy scrambled eggs, golden pancakes, stacks of buttered white toast. Ice tea, chocolate milk, orange juice, and coffee served in thick mugs, cracked from years of holding hot coffee, mugs that had touched how many lips? More coffee? Oh, yes, please, and Chas shoveled in the sugar, stirring the muddy slurry, appreciating for the first time how good coffee could be…

***

I guess I must’ve been hungry when I wrote that! The actual place that inspired that passage was Tom’s Diner on Colfax Avenue, Denver, Colorado.

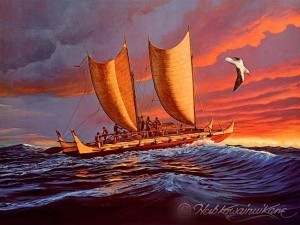

February 23, 2014

Interview with anthropologist, author, filmmaker, and voyager Sam Low

Bob and I had the pleasure of meeting author Sam Low and his kinsman, navigator Nainoa Thomson at Imiloa Astronomy Center in Hilo, Hawaii, last June at a book talk and signing of Hawaiki Rising. The book release coincided with the beginning of a new voyage for Hokule’a, Hawaii’s traditional voyaging canoe, on the fortieth anniversary of its creation.

Bob and I had the pleasure of meeting author Sam Low and his kinsman, navigator Nainoa Thomson at Imiloa Astronomy Center in Hilo, Hawaii, last June at a book talk and signing of Hawaiki Rising. The book release coincided with the beginning of a new voyage for Hokule’a, Hawaii’s traditional voyaging canoe, on the fortieth anniversary of its creation.

I’ve been interested in the history and renaissance of Polynesian voyaging canoes for many years. Having sailed from Hawaii to Polynesia and back in a fiberglass sloop with Bob, just the two of us (with all the modern gadgets such as GPS ) we developed an even greater appreciation for the Polynesian voyagers and their traditional methods of wayfinding.

In our large collection of books we have just about every book related to Polynesian nautical history that is in print today. When I heard about the release of Hawaiki Rising, I knew I had to read it. But I wondered if it would be a derivative of the handful of books that were already out there. Another crew-member telling his story, that sort of thing. Much more than a derivative, Sam breaks new ground in discussing the social and cultural problems the crew faced.

In Hawaiki Rising, Low adds to and enriches the growing library of Polynesian voyaging. An anthropologist, Sam’s roots are deep in Hawaiian soil; he is a direct descendent of John Palmer Parker and a cousin of Nainoa Thompson, and has sailed three times on the Hokulea. He has also worked as an underwater archaeologist and a filmmaker – all fascinating occupations – and his academic credentials are impressive. But for me, Sam’s greatest talent is as a writer. He has a unique perspective on the Hokulea story, sharing the tension and turmoil on board, and he has the skills to craft a compelling history.

I wrote a review of Hawaiki Rising and reached out to the author via his website. Although a very thorough interview is posted on his website, Sam graciously agreed to answer my questions. So here we go…

I would like to ask you a little more about your Hawaiian roots and connections. You said your father was raised in Kohala? Can you tell me more about your father, your Ohana, and your Hawaiian roots?

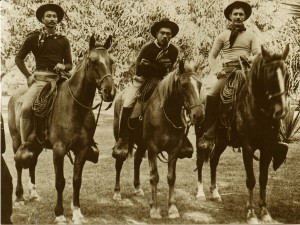

My great grandfather, John Somes Low, traveled from Gloucester, Massachusetts to the Big Island in 1850, to seek his fortune. In 1857 he married Martha Kekapa Namoomoo Parker Fuller, the daughter of Mary Parker and grand daughter of John Palmer Parker, head of the Parker Ranch, the most affluent of the haole settlers in Waimea. His son, Eben Parker Low, my grandfather, was born and raised on the ranch and became a famous cowboy. They called him Rawhide Ben. Ben later founded his own ranch, Puuwaawaa, on the big island. In addition to his exploits as a roper of wild cattle on the slopes of Mauna Kea, he was famous in the islands for sending three cowboys to compete in the Cheyenne Roundup in Wyoming in 1908. They entered the roping contest and placed first, third and fifth – a blow for the haole cowboys who doubted they could rope at all.

My father was sent away [from Hawaii] to school in Connecticut when he was 17 years old. The story goes that his father went bankrupt at home and he had no money to pay for his son’s return – so my father decided to make his way in New England. He grew up to become an artist, teacher and director of an art museum in New Britain, Connecticut, married a beautiful and talented New Englander, had me, and stayed on.

I knew that my father was different from other dads at an early age. For one thing, he did not work in an office, he went to his studio to paint, or to Loomis School to teach art, or to the New Britain Museum of American Art where he was the director. My mother was an artist, too, so I grew up in a very creative family. And my father was the only dad that I knew who played the guitar and sang songs in Hawaiian. The fact that I was part Hawaiian didn’t really have much meaning for me, growing up in a very haole world in New England. What fascinated me most were stories my father told about HIS father – a famous cowboy from the Big Island known as “Rawhide Ben Low.” How could I not be interested in a grandfather who was a cowboy? I loved dad’s stories of Rawhide Ben growing up on the Parker Ranch, hunting wild cattle on the slopes of Mauna Kea, losing his arm in a roping accident, and founding Puuwaawaa Ranch. Still, I really did not know what “being Hawaiian” meant.

In 1964, after graduating from Yale University, I was commissioned as a Naval Officer and ordered to a ship in Pearl Harbor – which was my choice – I wanted to see Hawaii.

My plan was to drive a battered Volkswagen across country to San Francisco, ship the car to Hawaii and fly to join my ship. On the day that I left home, my father took me aside.

“I will see you in Hawaii,” he told me. “I have not returned but now is the time. You will be there and I want to see my family.”

He died in his sleep that night of a massive heart attack.

Later, in Hawaii, an elderly cousin took me aside. “When your father never came back, some of us in the family were angry with him. We felt that we were not good enough for him. But there is another reason. When he left the islands, he went to a kahuna for a blessing. The kahuna told him that he would die young and that he would never come home. I think he did not come back because he was afraid to. And now the kahuna’s story has come true. But I am glad that you are here. In you, he has come home.”

It was not until I arrived in Hawaii for the first time in the fall of 1964, as a young naval officer stationed on a ship home ported in Pearl Harbor, that I began to get an inkling of my Hawaiian identity.

I lived on Sunset Beach for about six months in a house I rented from the famous surfer Fred Van Dyke. During that time, I got to know my aunt, Clorinda Lucas – and I was introduced to an old-time, authentic Hawaiian life style by staying with her in Niu Valley. Clorinda was a well-known social worker who dedicated her life to helping Hawaiians. Almost every day, Hawaiian families would visit her home in Niu and be welcomed to discuss their lives, their joys and sorrows, with Clorinda. And, when needed, Clorinda would find a way to help them. It was this “helping” ethic that I found most fascinating and that introduced me to, if you will, the “aloha spirit.”

At that time, I did not really see much left of an authentic Hawaiian culture. None of my family spoke Hawaiian – with the exception of Clorinda who knew a few sentences and phrases. All of them, like so many Hawaiians, had been raised to deal with a haole world. I did not see any classic hula. The culture seemed to be dying.

In 1976, I read about Hōkūle‘a and her successful voyage from Hawai‘i to Tahiti – carrying her crew 2400 miles in thirty-five days. Even more astonishing, she was navigated by Mau Piailug, a man from a tiny Micronesian Island who found his way as his ancestors always had, without charts or instruments, relying instead on a world of natural signs. I determined to make a film about this story, The Navigators – Pathfinders of the Pacific which has just been re-released in high definition video, and to tell it from the perspective of the scientists who had discovered the truth about ancient Polynesian explorers and men like Mau Piailug who continued to sail in the old way.

I spent two years traveling the Pacific with experienced archaeologists as guides, retracing steps taken by early Polynesian mariners. I sailed with Mau Piailug from his home island of Satawal. He told me how he navigated by the stars and by signs in the wind and waves using secret knowledge handed down from father to son over thousands of years. I spent time in Hawai‘i with Nainoa Thompson who combined Mau’s teachings with his own discoveries to reveal how ancient Polynesians may have guided their canoes. I began to feel a stirring in my blood. I am one-quarter Hawaiian, and three-quarters haole—descended from a Hawaiian aliʻi (a chief) and a New Englander who ventured to the islands in 1850 seeking wealth and bringing with him disease and an alien way of life. At first glance, this influx of outsiders seemed to have destroyed Hawaiian culture. But as I visited the islands more often, I discovered an astonishing revival of the Hawaiian language, poetry, dance and all the other arts of indigenous life. Hawaiian culture had not died. It had gone underground—waiting for a spark to ignite it. That spark was Hōkūle‘a.

artist, Herb Kane

In 1995, I was at the departure ceremonies for Hokule’a when she left on Na ‘Ohana Holo Moana – a voyage to join up with 6 other canoes and sail from Tahiti back to Hawaii via the Marquesas. Nainoa came up to me and said, “Do you want to sail back with us on an escort boat from Tahiti, one of the crew couldn’t make it and I think I can get you a berth.” It was an unexpected honor. Naturally, I said yes.

In April, I flew to Nuku Hiva and joined the crew of Rizaldar, a 43-foot Swann cruising-racing boat, captain Randy Wichman. On April 23rd we set off from Nuku Hiva for Hawaii in the company of 6 canoes.

The trip aboard Rizaldar was exhilarating. And on that voyage, I found a new meaning and mission. After we had set foot on Hawaiian soil, I wrote: “Reflecting back on the trip, I remember one night in particular. As we moved through the Equatorial Counter Current, during the midnight to six watch, I experienced the arc of stars above me wheel across the sky. Some tribal people believe the stars are the spirits of their ancestors. On that night, I imagined that a pair of stars rising off the starboard bow were the spirits of my mother and father. I felt a deep welling of emotion. I imagined the Milky Way to be a trail of my ancestors stretching back to the original seeding of my bloodline. As I looked over the side of the vessel, I saw glowing plankton turn the sea as effervescent as champagne. Large globs of green light flared up, shimmered for an instant, then slowly faded. I seemed to float through a universe of jewels, the stars above and the sea below. Here, perhaps as far away from the influence of modern life as one can get, time stood still. I imagined myself on the deck of a Polynesian canoe, making the first voyage to Hawaii. The past lived.”

I kept a log of the voyage with the idea of writing an article, which was published by Sail Magazine and is available at: http://www.samlow.com/sail-nav/starpaths.html.

In that article, I wrote: “My mission here is personal – a voyage back to my own roots. My father was Polynesian — born in Hawaii but sent as a teenager to a boarding school in Connecticut. He stayed in New England, and died there, never having returned to the islands. I am returning for him. “

In 1999, I was invited by Nainoa to voyage aboard Hokule’a from Tahiti to Rapa Nui (Easter Island). My job would be to document the voyage.

In my log, on October 21st, after making landfall, I wrote: “On this, my last day on the island, I sit on a ledge of rocks down by the harbor in Hanga Roa, lost in a reverie. As I listen to the waves crash on the reef offshore, I remember the excitement of sighting Rapa Nui and the inner peace of the evening before our arrival, as Höküle’a ghosted along the coast. We had all lingered on deck, enjoying the last few moments of comradeship with each other and our canoe. Hotu Matua (The Polynesian navigator who discovered Rapa Nui) and his men must have seen what we were seeing – the dark smudge of the island against a backdrop of stars – and they must have heard what we were hearing: the rush of wind over sails, the soft lap of waves on twin hulls, the murmur of sailors as they sit shoulder to shoulder, waiting for the first scent of land to reach them.”

In 2000 I served aboard the canoe on a voyage from Tahiti to Hawaii and in 2007 I sailed from Chuuk (in Micronesia) to Mau Piaulug’s home island of Satawal for the pwo ceremony – an initiation of Hawaiian and Micronesian navigators as masters of the art.

You’ve been a part of some incredible voyages, as listed on your webpage. Can you tell me about your early interest and connections with sailing and voyage making? Something about your experience in the Naval Reserves, if applicable?

From compendium

“This is a story of the sea – and it is natural that I should choose this as my first book because I have been attracted to the sea all my life. I grew up on a small island – Martha’s Vineyard – and I spent most of my time on or in the ocean. When I graduated from college I joined the United States Navy as an officer and served aboard a ship on Yankee Station off the coast of Viet Nam at the beginning of the Viet Nam war. Afterwards, I studied nautical archeology and was a member of a team of National Geographic archeologists excavating a Roman shipwreck off Italy, a Byzantine shipwreck off the coast of Turkey and a Roman seaport a few hundred miles north of Rome. I have always owned boats, both sailing and power, and have written about them and to this day I spend a great deal of time on the ocean.”

As you know, I’m a big fan of Hawaiki Rising. You have dared to bring out the tensions between the Hawaiians and the Haloes involved in the project, presenting them with understanding. What is your relationship now, with the current Polynesian navigators?

It was important to tell the story of the Pilikia (Hawaiian word for “trouble”) during the early years of Hokule’a – the friction between Hawaiian and haole crewmembers – because it illustrated the anger that came to the surface when Hawaiians began to realize what had happened to their ancestors. The story of the conquest of Hawaii by outsiders, of the suppression of the Hawaiian culture, was not well known in Hawaii at the time. That story had been swept under the rug. It was only natural that, once Hawaiians learned about it that they would become disillusioned and angry with how all this had been kept from them – was not taught in schools or spoken of by their parents. I needed to write of the anger because I needed to tell that story of oppression so my readers would understand the importance of the revival of Hawaiian culture which was brought about by voyaging.

You ask about my relationship with the navigators.

Nainoa Thompson, the chief navigator and mentor of all the others, is my cousin. When I go to Hawaii, I spend time with his mother and live in a guest house not far from Nainoa’s home where he lives with his wife and two children. Our relationship is close. We have sailed together and I have spent about six years interviewing him for the book. The process of reliving his past, he has told me, has helped develop his own thinking about navigation and wayfinding. I would say that the exchange, the working together, has created a bond between us.

Bruce Blankenfeld, another of the experienced navigators, is married to Nainoa’s sister and also lives next door. He took me under his wing early in the project and helped me understand the basic concepts of navigation. He told me stories that were essential to my understanding of the deeper basis of wayfinding and taught me a great deal about Hawaiian culture. He is a mentor and a good friend.

Chad Kalepa Baybayan, another of the experienced wayfinders, is a strong supporter of my work. We voyaged together from Mangareva to Rapa Nui in 1999 and got to know one another. I interviewed him extensively for the book and we also traveled together to Satawal, aboard Hokule’a, for the pwo ceremony in which Mau bestowed highest honors on the Hawaiian navigators. I consider him a friend as well.

I want to know more about your filmmaking projects. How did you become a producer/director? Are your films available to the general public?

At Harvard, I studied anthropology and what is known as ethnographic filmmaking – a deep kind of documentary in which the filmmaker, often an anthropologist, lives with the people for sometimes years at a time and documents the deep aspects of their lives. Two of the best ethnographic filmmakers had Harvard connections, Tim Asch and John Marshall, and they both took me under their wing and taught me the basics of filmmaking. John loaned me an Auricon camera, gave me some film, and helped me when I went off on a Gloucester Trawler to the Grand Banks to make my first film (it never progressed beyond the first assembly but was a seminal experience).

In 1978, I got a job as senor researcher on a remarkable Public Television series called Odyssey. The executive producer of Odyssey, Michael Ambrosino, was the creator of the first hour-long documentary series for PBS, called NOVA. He was another mentor. In my first year at Odyssey, I became what is called an acquisitions producer. Odyssey produced 12 programs a year, 6 of which were purchased from other sources such as the BBC and Granada Television in the UK and “remade” for American Public Television. The English programs were often about 6 to 10 minutes too short for American TV and so I traveled to the UK where I went through the outtakes with a skilled editor and added new sequences to the films. By so doing, I had to deconstruct the basic structure of each film, understand how the story was told, find places where new scenes could be inserted without disturbing the basic rhythm of the film. I had to understand the film. That was a crash course in filmmaking, better I think than any film school. I “remade” four films in the first year.

In the second year, I proposed a film of my own – The Ancient Mariners – about how underwater archeologists, working in the Mediterranean, had excavated three ships – Greek, Byzantine and Arab – that demonstrated a fundamental change in shipbuilding technology that made possible the building of the large vessels used by Europeans to discover and explore the world’s oceans. That was my first real film. It was my graduation exercise.

Three years later, Odyssey having competed its run, I produced The Navigators – Pathfinders of the Pacific, which tells the story of my ancestors’ settlement of the Pacific. That film cemented my interest in Polynesian voyaging and led, eventually, to the publication of Hawaiki Rising thirty years later. The Navigators has been restored and was re-released in January of this year and is now available on DVD for home viewing. It has been shown on the BBC and television venues around the world and has continued to be used in classrooms and is, according to many teachers I have spoken with, still the best movie available about Polynesian settlement and voyaging. It features unique footage we took of Mau Piailug during a two-week stay in 1982 on his island, Satawal, in the Caroline islands. It can be purchased from me directly on my website for $20.00 and will soon be available, I hope, on Amazon.com along with Hawaiki Rising. I think that the book and film work well together and am pleased that they are both now being used in classrooms and seen in homes all over.

As an anthropologist as well as a participant in the voyages of Hokule’a, where do you see traditional wayfinding and Polynesian voyaging going?

For the first 25 years of its existence, Hokule’a voyaged in the wake of our ancestors on a primary mission of recovering the skills and the pride of all Polynesians. Our people, whether in Tahiti, New Zealand or Hawaii had been suppressed by colonial powers – as have indigenous people all over the world. Hokule’a and her voyages are deeply symbolic to us all – and she has restored our pride of ancestry. In Hawaii, a profound revival of culture has occurred, to the point that the language, once ebbing away, is now being spoken fluently by an ever-increasing number of Hawaiians. In 1995, in fact, the fist cohort of Hawaiian students graduated from high school having spoken Hawaiian exclusively in their classrooms. Classic hula is back, replacing the ersatz versions common in Hollywood movies and Waikiki bars. Curing practices, aspects of our region and spirituality, chants, poetry, the martial arts and sculpture are all being revived. And voyaging is now strong throughout Polynesia, with traditional canoes sailing out of ports in Aotearoa (New Zealand), Tahiti, Tonga, the Marquesas and other islands – about twenty in all. So Hokule’a has pretty much accomplished her mission of restoring pride. She now joins with others on a different mission – supporting the effort of people around the world to seek a sustainable relationship with planet Earth.

As Nainoa once told me: “When you voyage, you become much more attuned to nature. You begin to see the canoe as nothing more than a tiny island surrounded by the sea. We have everything aboard the canoe that we need to survive as long as we marshal those resources well. We have learned to do that. Now we have to look at our islands, and eventually the planet, in the same way. We need to learn to be good stewards.”

This is not really a new mission. It is founded on basic Polynesian values. Ancient Polynesians fashioned canoes like Hokule’a with stone tools. They used koa wood for the hulls, breadfruit sap and coconut husks for caulking, and coconut fiber rope for lashings. With materials from the land they fashioned a vessel to blend with the sea.

“When our ancestors went to the mountains to cut down trees they did not think they were taking the tree’s life,” navigator Bruce Blankenfeld once told me. “They were just altering its essence, taking it from the forest and putting it into the sea, and in Hawaii the sea and the land are tied together. Everything in the sea has a counterpart on the land because on an island the land and the sea rely on each other for life.”

Polynesian islanders recognized the inherent “oneness” of their natural world because islands are fragile places where the interaction of man and nature is clearly seen. When they cut the trees in their valleys they must have noticed the effect of pollution from runoff on their reefs. This may explain why ancient Polynesians constantly balanced the resources of land and sea in their rituals. Some anthropologists call it “dualism” and believe they have discovered in such ‘primitive’ societies a yin and yang universal in human thought. But I think it’s simpler than that. If ritual reinforces ways of living essential for survival then it is no mystery why Polynesian islanders recognized the aholehole fish as ritually equivalent to a species of taro plant. Today, we are so distanced from this basic understanding of connectedness that we use a relatively new word to express it – ecology.

“When we sail we find ourselves surrounded by an empty ocean which forces us to turn inward and consider how to take care of ourselves, each other, our canoe,” says Nainoa. “Learning to survive on long voyages also forces us to consider how to survive on the islands we live on, it’s a microcosm for learning to survive everywhere. In Hawaii we are surrounded by the world’s largest ocean, but Earth itself is also a kind of island, surrounded by an ocean of space. In the end, every single one of us – no matter what our ethnic background or nationality – is native to this planet. As the native community of Earth we should all aspire to live in pono – in balance – between all people, all living things and the resources of our planet.”

To support this mission of pono, of balance, Hokule’a will sail around the world beginning in May, 2014.

As Nainoa tells us: “In our Hawaiian language we have a word—mālama—which means “to care for,” and I think it evolved from our own heritage of long distance voyaging. Our ancestors learned that to arrive safely at their destination they must malama each other and their canoe.”

“The wisdom and values of our ancestors enabled them to mālama Hawai‘i

and her surrounding oceans for nearly 2,000 years. By carefully managing their

natural resources, they were able to sustain a large, healthy population. Now, we

must learn to treat our planet in the same way.”

“In May. 2014, we will begin a voyage around the world to mālama honua

—“care for the Earth.” We will sail for approximately 36 months; travel more

than 45,000 nautical miles; and visit at least 26 countries, with 62 stops. During

the voyage, we will connect with communities that share our values and vision.

Returning home, we will bring with us lessons of hope and action as we navigate toward a safe, peaceful, and sustainable future for our children.”

(Follow Hokule’a's Worldwide Voyage)

What’s next for Sam Low? What are you working on that you can tell me about?

For the next three years, while Hokule’a is voyaging round the world, I will continue to work to support her mission. I hope to give talks in the American hinterlands and up and down both coasts, where many people still think that Polynesia was settled by people who drifted on rafts (Kon Tiki did sell 50 million copies so I have a lot of work to do.)

I have been invited to write a chapter for a new book about Polynesian prehistory and will also take up a project I put aside long ago – a book about my grandfather, “Rawhide” Ben Low, a famous Hawaiian cowboy. Ben wrote a memoir which was never published and it is my kuleana – my privilege and responsibility – to finish it. He lived at a very interesting time, when Hawaiian culture was being both actively and passively suppressed, and I hope to weave a little of that theme into this new book so it will, in a sense, be a continuation of what I wrote about in Hawaiki Rising.

Writing that book will also be a continuation of my own personal search to discover what it means to me to be Hawaiian. I look forward to it.

***

Mahalo, Sam. I’m looking forward to reading that next book!

Visit Sam Low’s website

February 22, 2014

Interior dialogue: What is your character really thinking?

Having just adapted one of my novels to a stage play, I’m acutely aware of how important a character’s unspoken thoughts and feelings are to the story. In a play we cannot know a character’s direct thoughts unless he speaks them out loud in a sort of soliloquy. (Suddenly I’m imagining a performance in which the actors turn their heads with hand raised to the side of the mouth to voice their true, unspoken thoughts before delivering their scripted lines. It could be interesting!) Novels and stage plays both tell stories, but in different ways. Actors express their emotions physically, and thoughts are implied or communicated indirectly. In prose, we can have a direct view into our character’s mind, and heart. We can become the character.

Why is showing a character’s thoughts a powerful tool for the fiction writer? So often what we think and what we say out loud are at odds. This in itself can raise the tension of your prose. Characters think one thing, say another, and then DO something completely different. By showing the thoughts, the spoken dialogue, and the action, we have three ways to develop character, create tension, and move the story along.

Interior dialogue doesn’t have to be a full paragraph of mind-chat. Unless you’re writing a stream-of-consciousness novel along the lines of Joyce’s Ulysses or Wallace’s Infinite Jest, you’ll want to filter your character’s thoughts and emotions to suit your purpose.

Picking up a novel I recently reviewed (Britannia’s Reach by Antoine Vanner) I’m opening to a random page to look for examples of interior dialogue, or other glimpses inside the protagonist’s mind.

Dawlish ducked under the hitching bar and cupped the mare’s nose in his hands for an instant. She was quivering, her eyes straining, yet she seemed to calm slightly at his touch. An image of morning canters in Shropshire flashed for an incongruous instant through his mind as his nostrils caught the whiff of her scent... (pg 101)

Here’s another example, from the same book:

“I am a British Officer, Sir,” Dawlish said, feeling a little sententious, but unsure of how otherwise to answer… “ (pg. 120)

While this isn’t an extended interior monologue, it gives us an inside view of our protagonist without slowing the story down with full-fledged, developed thoughts. It’s concise and effective.

Patrick O’Brian’s interior dialogue is more oblique and tends to be a longer narration. Take this example:

Jack did not reply at once: his mind was dealing with the advantages and disadvantages of touching at a Brazilian port – the loss of the trade-wind inshore, the way the south-easter would often hang in the east for weeks on end just under the tropic, so that a ship might have to beat into it, tack upon tack, for very little gain, or else run far south for the westerlies; a whole mass of considerations. His face was already sad; now it grew stern and cold; and when he did speak it was not to tell Stephen what he intended to do but to ask whether Pullings and the people in the sickbay might be allowed wine yet. (Desolation Island, pp.156-157)

These almost stream-of-consciousness thoughts of Jack’s, in the middle of a conversation, make him very life-like and complex. When he does speak, it is altogether unexpected and has nothing to do with what he was thinking. This fleshes out Jack’s character, gives it depth and complexity.

Pick up the nearest novel to you and look for examples on any given page.

Now take a page or two of your prose, a story you’ve been working on. Try enriching this scene by adding thought-bites and unspoken feelings. Try adding a sentence or two of interior dialogue that only the character and the reader are privy to.

What is your character REALLY thinking or feeling before he speaks? How does he feel AFTER he says it? Does his mind wander when the other person is speaking? That happens in real life all the time. How much you let us see inside your protag’s head is up to you.

To bring your characters to life on the page, let us hear what they’re thinking. Let us slip inside their skin and feel it tingle.