Linda Collison's Blog, page 19

February 16, 2014

M.C. Muir on discipline and motivation during the Age of Sail.

“Research, when writing a novel,” says Margaret Muir, “May be time-consuming but it is an interesting journey to be on. Usually, it means delving deeper into a subject than necessary. But once embarked on, the search for facts becomes compulsive, resulting in an accumulation of information in excess of what is required. Such was the case when I began investigating crime and punishment in the Royal Navy, in particular the Articles of War – the strict rules that regulated the behaviour of men aboard His Majesty’s ships. Rather than tossing the excess information away, I offer it as an example of where research can lead.”

Crime and punishment according to law

Every such person…shall suffer death

by M.C. Muir

The first laws of the sea were prepared by Richard the Lionheart for his men heading off on the crusades. The Ordinance or Usages of the Sea of Richard 1, the Lionhearted was recorded in the 13th century. According to these regulations:

He who kills a man on shipboard, shall be bound to the dead man, and thrown into the sea; if the man is killed on shore, the slayer shall be bound to the dead body and buried with it.

Anyone convicted by lawful witness of having drawn his knife to strike another, or who shall have drawn blood of him, he is to lose his hand.

Anyone convicted of theft shall be shorn …; boiling pitch shall be poured on his head and he shall be set ashore at the first land the ship touches.

From this early set of ordinances, the Black Book of the Admiralty emerged in the 15th century. The punishment, according to the Black Book, for the first offense of sleeping on watch, was mild. The sailor suffered a bucket of sea-water to be poured over his head. But if caught for a fourth time, the punishment usually proved fatal.

The offender was slung in a covered basket hung below the bowsprit. Within this prison he had a loaf of bread, a mug of ale and a sharp knife. An armed sentry ensured that he did not return aboard if he managed to escape from the basket. Two alternatives remained – starve to death or cut himself adrift to drown in the sea.

The Articles of War, formalized by an Act of Parliament in 1661, were based on this old Admiralty code of discipline and apart from some amendments made in the 18th century much of the content, and the brutal punishments they carried, remained the same throughout the age-of-sail.

As readers of nautical fiction are aware, the penalty for many minor misdemeanours, as well as serious offenses, carried the death penalty. Crimes ranged from abusive behaviour, negligence of duty, disobeying orders and mutiny, and the Articles of War applied equally to the lowliest ship’s boy as to the senior naval officers. Every man aboard ship was reminded of them on a regular basis – usually on a Sunday following the public Worship of God Almighty, which was also stipulated in the Articles.

While crimes and subsequent punishments at sea seemed exceedingly harsh, in 1800, the courts in England listed hundreds of minor offenses that were punishable by death. Crimes ranged from common assault, to burglarizing, to stealing a loaf of bread. For the lucky ones – mostly young males, a plea for clemency resulted in the sentence being commuted to transportation to the colonies – over the seas and beyond the seas. However, for some, enduring years of depravity in chains and subjected to the lash, resulted in a lingering death.

On land, death at the end of a rope usually came as the result of asphyxia. With a short drop through the trap door (the long drop was not introduced till later), the noose tightened but failed to separate the vertebrae, failed to cut off the blood supply and therefore failed to cause unconsciousness. Depending on where the rope was placed around the man’s neck, the victim gasped for breath as his neck muscles attempted to protect his windpipe from being crushed and the root of his tongue being forced further up his throat.

Writhing in mental if not physical agony, it could take up to half-an-hour before a man was declared dead. Hence the body was left dangling for that time to ensure the hangman had done his job satisfactorily. It was not unknown, on land, for friends of a condemned man, or members of his family, to leap forward and pull down on his feet in order to tighten the noose and hasten his demise.

At sea, the most common punishment for a man sentenced to suffer death was to be hung from one of the upper yards. This was done by reeving a sturdy rope through a block on the end of a yardarm. After his hands were tied behind his back and his ankles lashed together, the condemned man was then blindfolded or hoodwinked and a noose placed around his neck. The slack on the other end of the rope was taken up by a dozen men – often the worst types on board, and when the signal was given, the drums rolled, a gun was fired and the line was hauled lifting the condemned man from the deck and up into the rigging. Once aloft, the signal was given to belay hauling and secure the line to a pin on the rail.

With the body jerking, the face livid, the eyes and the tongue protruding, the assembled ship’s company continued to observe until the writhing stopped. However, to make sure the man was dead, his body remained hanging in the rigging for half-an-hour before it was lowered to the deck. After examination by the ship’s doctor, confirmation of death was pronounced.

But hangings were not a punishment which could be meted out by a single captain. For crimes which carried the death penalty a Punishment Warrant from the Admiralty or a Court Martial had to be convened. Without this body of senior officers to hear the case, captains were limited in the punishments they could deliver aboard their ships. Floggings, therefore, were a common form of shipboard punishment.

During the Nelson era, according to Admiralty regulations, one dozen strokes of the cat o’ nine tails was the maximum that could be given. Some captains appear to have ignored this ruling, while others were loath to flog their men arguing that it bred hatred and did not foster respect.

The barbaric sentence of being flogged around the fleet could only be delivered by a Court Martial. The result of such a cruel punishment was tantamount to a death sentence, plus it guaranteed a far more painful death than the short drop from the gallows.

When a man was sentenced to such a punishment, he was delivered into a ship’s boat in which a frame had been erected. With his hands and feet lashed to the frame, the victim was rowed to every ship of the fleet where a Bosun’s mate would inflict the prescribed number of lashes. The addition of a left-handed flagellator, approved by some sadistic captains, created a criss-cross pattern of stripes drawn by the leather thongs on the victim’s back.

The doctor, attending the proceedings in the boat, was not on hand to halt the punishment, but to advise if and when the man was dead. In some cases the floggings were continued on a lifeless corpse.

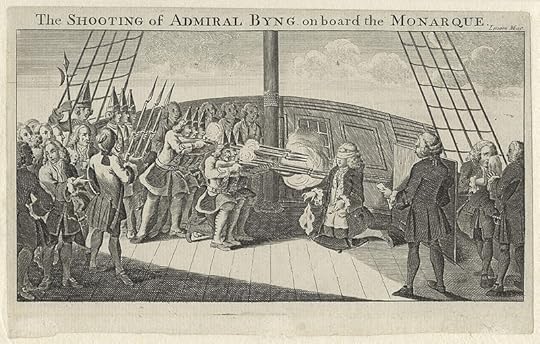

A speedy and far less painful exit from this life could be achieved when sentenced to death by shooting. One such sentence was carried out in 1757. The findings of a British Court Martial determined that Admiral John Byng, while serving in the Mediterranean, had contravened one of the Articles of War. He was accused of failing ‘to do his utmost’ to defend and hold the port of Minorca, which, as a result, was taken by the French. Byng’s argument, that his fleet had been poorly supplied by the Admiralty and was under-manned, was ignored and pleas for clemency were rejected by King George ll. Admiral Byng was taken aboard HMS Monarch in the Solent, and in front of his own men and the company of other ships, he knelt on the quarterdeck and was summarily executed by a firing squad.

Byng’s only consolation was that this mode of punishment provided him with a quick death, whereas men put ashore on a deserted island or cast adrift in an open boat faced a lingering death – death from exposure, thirst, starvation, and eventual madness. The events surrounding the life of Alexander Selkirk were famously fictionalized by Daniel Defoe in his book Robinson Crusoe. Cast ashore, after arguing with the captain, on Juan Fernandez Island in the Pacific Ocean, Selkirk did not die, as most expected, but survived alone for several years.

In other circumstances, when sailors found themselves adrift following the sinking of their ship, the survivors adopted the role of judge and jury, and passed sentence on the first unlucky victim who was to be slaughtered and eaten. Cannibalisation is not uncommon in the annals of history and if survivors were eventually found, their only defense was to quote the unwritten law of the sea. In his book, The Custom of the Sea, Neil Hanson quotes dozens of recorded incidences of cannibalism.

Finally, the most diabolical sentence handed out aboard ships of various nations was keel hauling. While it was not a death sentence per-se, it invariably resulted in the sailor’s relatively quick but cruelly painful demise. Rigged on a line that was run below the ship’s keel, the victim’s hands and feet were tied. The rope around his chest tightened as a group of sailors hauled him from the deck, dropped him into the water and pulled him under the vessel. As he was dragged across the barnacle-encrusted hull, the razor-sharp shells ripped the skin from his face, arms and body. The more months the ship had been at sea, since its bottom had been scraped, the more lethal the punishment it provided. If the victim did not drown in the process, he did not survive long from his shocking injuries. Keel hauling, in the Royal Navy, was discontinued in 1720 but continued until 1750 in some other European navies.

For any man who would suffer death at sea, death on the gun deck from an enemy’s broadside was a far sweeter alternative to being punished according to the Royal Navy’s Articles of War, which changed little over the centuries.

***

For material used in this article, my thanks go to Wikipedia and Customs of the Navy.

M.C. Muir is the author of The Oliver Quintrell Series – Under Admiralty Orders. Floating Gold, book one of series, is free on Kindle for three days, February 17-19, 2014, coinciding with this guest post. The books are available separately, and the trilogy as a boxed set on Kindle.

M.C. Muir is the author of The Oliver Quintrell Series – Under Admiralty Orders. Floating Gold, book one of series, is free on Kindle for three days, February 17-19, 2014, coinciding with this guest post. The books are available separately, and the trilogy as a boxed set on Kindle.

“Like” Muir’s Floating Gold page on Facebook, to keep up with future books in the series, and special offers.

Upcoming events: Margaret Muir will be on two author panels at Tasmania’s Festival of Golden Words March 14-16.

February 15, 2014

From historical fiction to sci-fi space opera; time-jumping through the ages

I have a hard time developing a “platform” as a writer because I don’t stick to one genre. Instead, I time-hop from past to present to future.

I have a hard time developing a “platform” as a writer because I don’t stick to one genre. Instead, I time-hop from past to present to future.

I’ve just published a new short story. Holiday on Planet Jolieterre; a Nova Skylar Space Nurse Adventure is available in electronic format on Smashwords for 99 cents.

This space opera satire was inspired by a Mediterranean cruise Bob and I took last year aboard Independence of the Seas, along with fellow writer Margaret Muir (who will guest post here on Monday). I used my nursing background to create the protagonist, Nurse Nova Skylar, a hermaphrodite from planet Skeksio.

I LOVE the cover design by Albert Roberts, who also designed the covers for Friday Night Knife and Gun Club, and Looking for Redfeather. Albert is a very talented graphic artist who also plays a ship surgeon aboard HMS Acasta.

Holiday on Planet Jolieterre takes place in the distant future on board a cruise ship, Looking for Redfeather takes place on the road in the 21st century, and the Patricia MacPherson Nautical Adventures take place in the 18th century.

In spite of the diverse settings and time periods, I strive to create interesting, believable characters. What’s your favorite setting?

February 9, 2014

Character Motivation; Love-Driven Rage in the Bronze Age

Fiction writers: What motivates your protagonist?

Fiction writers: What motivates your protagonist?

Hand of Fire tells the tale of Briseis, the captive woman Achilles and Agamemnon fought over in the Iliad. When Achilles, the half-immortal Greek warrior, takes Briseis captive in the midst of the Trojan War, he gets more than he bargained for: a healing priestess, a strong-willed princess—and a warrior. She raises a sword against Achilles and ignites a passion that seals his fate and changes her destiny.

What makes a young woman pick up a sword against a powerful Greek Warrior? I asked Judith Starkston, author of Hand of Fire, to tell us something about how she writes believable action in historical fiction. What makes Brisius, her young female protagonist, pick up a sword against Achilles, and how do you convince the reader of this heroic action?

Starkston says:

“A while back Justin Aucoin had a great guest post here on sword fighting. I commented that I wished I knew more about sword fights, but that mine were Homeric and thus somewhat different from his descriptions. Linda asked me what my favorite Homeric fight scene was and I somewhat jokingly said, the one where my heroine takes up a sword against Achilles (apologies to the bard—no such scene in the Homeric corpus—I made it up). She invited me to write a post about that scene. I’m focusing on motivation—why Briseis lifted that sword—since I can claim no expertise in actual sword fighting technique the way Justin can.

In Homer’s Iliad Briseis has only a few lines. She is the captive woman Achilles and Agamemnon fight over and as such she is central to the action of the poem, but we only learn a tiny amount about her. We know she is a princess from the city of Lyrnessos, which is one of Troy’s allies, that she had three brothers, and that she loved Achilles even though he took her captive and seemingly ruined her life. I decided to write a novel filling out her life and world. And in the course of that story she challenges the greatest of the Greek heroes with a sword.”

Why did she take up a sword?

“If she were a warrior princess, the sort we often find in fantasy novels or in history through women like Britain’s Boudica, that would be easy to answer. But the Briseis I got to know was no warrior. I researched the recently excavated world of the Bronze Age in what is now Turkey where Troy was situated and found a model of the person I thought she might well have been in the ancient Hittite hashawa, a kind of healing priestess, literate and respected. The Hittites and culturally related peoples lived throughout this region. I found powerful women in this culture, both the healing priestesses and queens who continued ruling after their husband’s deaths and whose counsel was accepted as equal to the king’s. As both a princess and a hashawa, Briseis wielded power, but there were no examples of women who fought battles or took up arms. As a healer, she opposed taking her people into the Trojan War because she knew up close what danger to the human body truly means. In my novel she spends her time and emotional focus curing people and trying her best to protect the Lyrnessans from her husband’s rash desire to fight Achilles at any cost. She is the most unlikely candidate for fighting with a sword against the half-immortal hero.

So why does she do it? For the most primeval and basic of reasons. She is driven to protect her family, in this case her youngest brother, whom she had been especially close to throughout her childhood. She has no battle training and she doesn’t carry on as a warrior from that day forth, but in a moment of love-driven rage she grabs a sword that chance has laid at her feet at this critical moment. She defends her brother, whose character we already know as sweet and unwarriorlike, because for her there is no choice, no alternative. The wild sound of fury like hundreds of bees swarming in her head and the utter unwillingness to accept that she is helpless to protect her brother drive her more than self-preservation.

That’s not difficult to understand as motivation, but it only works if the character herself has enough courage and inner strength to take on such a daunting challenge, to feel no alternative. Many of us would see our brother or sister in danger and be unable to act with sufficient force. Interestingly enough, I knew fairly early on in the drafting of this book that this moment of confrontation would be central to the novel, of sword upraised defensively against the most powerful sword in legendary history. But it took me a while to find the solid core of Briseis’s strength and how to depict it. Briseis had to keep redirecting my efforts and showing me how to reveal inner resolve. She had to embrace violence and accept its inevitable place in her fractured world. I had a very hard time giving in to that. I kept shielding this young woman when she simply didn’t want to be.

Eventually a woman strong enough to challenge Achilles—and eventually to love this impossible hero—came forward, from the historical record and from my struggling imagination.”

Here’s a short passage from a fight scene in Hand of Fire:

(Brisius) stopped. A shadow had fallen across the opening. The guardsman sitting on the well drew his sword. Iatros pushed her down so she was hidden behind the well and drew his sword. She heard the sounds as bronze-nailed footsteps rushed. Swords clashed. A man fell.

Then a voice called out in Greek, “Lord Achilles, come over—” There was a grunt, a thud. The voice fell silent. A Greek warrior lay against the well. His hand loosened its grip on his sword.

She lifted her head to see over the well. Iatros stared at his bloody sword and the dead Greek. The man with the leg wound was on the ground, his sword arm still outstretched, but his innards poured out onto the hard dirt.

Other guardsmen came out of the stables, but it did not matter, for the gate filled with a huge form, and Achilles plunged toward Iatros. Her brother lifted his sword to meet the oncoming stroke. A rage rose up in her; the sound of a hundred bees filled her head. In one motion she swept the dead Greek’s sword off the ground and leapt from behind the well. Achilles’s blade flashed in the air above her. She saw his hands grasping the hilt and sensed their power, then saw his look of astonishment as she raised her blade against the blow aimed at her brother. A new, invincible strength coursed through her arms. The desire to strike—raw and terrifying—drove out her helplessness. Her blade met his. A bolt shot through her, and she reeled from the force. Achilles jerked his chest backwards even as the momentum of his swing carried him forward. Achilles’s sword cut through the unprotected joint of her brother’s armor between the neck and shoulder. Iatros’s head fell to the side. As the weight of Iatros’s body carried her to the ground, she heard an anguished cry and could not tell if it was hers or Achilles’s…

Judith Starkston writes historical fiction and mysteries set in Troy and the Hittite Empire, as well as the occasional contemporary short story. She also reviews books for Historical Novels Review, the New York Journal of Books, the Poisoned Fiction Review, and on her own website. Hand of Fire, will be published by Fireship Press on September 10, 2014. More about the historical background of this period, as well as historical fiction reviews can be found on the author’s website JudithStarkston.com. Follow her on Twitter @JudithStarkston and on Facebook .

February 7, 2014

Land’s End

Aloha from the Big Island of Hawaii, my private writer’s retreat.

Aloha from the Big Island of Hawaii, my private writer’s retreat.

Water covers about three-quarters of our planet’s surface.

Most of us find ourselves drawn to the seashore, if not the sea itself. The sea, the ocean, any body of water, represents possibilities. It might also represent our subconscious mind.

On an island, you can find land’s end in any direction.

In Hawaii, when you travel toward the sea, the direction is “makai.” When you travel further inland, to higher ground, the direction is “mauka.” Toward the sea, toward the mountains, is the rough translation. Today we’re going makai to write at the beach. Nothing better to clear the mind than the rhythmic rush of water lapping at the shore, a sound like breathing; like mother’s heartbeat. Set your beach chair in the sand in the brindled shade of one of the old kiawe trees and allow yourself to write. I like to free write with pen and paper; in an inexpensive black-and-white-speckled composition book. Free writing is like free diving for pearls. See how long you can write without coming up for air.

Don’t worry if you stray from your outline or your perceived plot, let the characters lead you. Don’t be afraid to waste words or to write poorly, just write to discover. Set your timer and begin. If you find a blank page staring at you, ask your character a question, in writing. Begin a sentence with “What if” and answer it in a myriad of ways.

Much of what a writer writes never makes it into the final manuscript. But the story is deeper for it. Free writing, writing to discover, enriches both character and setting. Don’t interrupt your writing time to look up historical facts or check a word usage, just make a note and keep wading into deeper water. When you get over your head, that’s where you’ll discover the real story. Don’t be afraid. Writing is swimming and free-writing is diving deep to explore the unseen.

What will you find beneath the surface today?

February 2, 2014

Finding Your Voice

Voice on the page – it’s what agents, publishers, and readers all want. But what is it?

Voice is difficult to define, yet you recognize it when you “hear” it. It’s a way of writing that is unique, like a fingerprint. As a fiction writer, you give your characters individual voices, yet you, the author, have an underlying voice of your own. Word choice, syntax, and what you choose to reveal, all make for a resonate and distinct sound on the page. Lively, individual writing – now that’s Voice.

A manuscript can be technically well-written, with interesting characters and a thrilling plot, but still reads flat. A computer might have written it; it has no voice. Another manuscript can be filled with mistakes and not ready for publication, but sounds much more alive. So alive it nearly jumps off the page. Which one do you want to read?

It generally takes years of writing to develop your own voice. Don’t worry about identifying or deconstructing it, just write from the heart. Get the story down the way it wants to come out. Don’t be afraid to write poorly. What you’re trying to do in the first draft is capture the heart of the thing. The soul. Write like only you can.

Of course you’ll have to revise it, and more than once. But don’t edit the heart out of it. This can happen if you over workshop your story and listen to too many self-proclaimed writing experts who have read all the books and know all the “rules” about creative writing. (That’s bullshit. Rules are meant to be broken, and all writing rules have successfully been broken!) Fellow writers and beta readers are most helpful NOT when they’re telling you HOW to write, but when they tell you what parts, what paragraphs, they liked best. An immediate, gut-level feedback. Those are the parts that have heart and voice. Write more of those kind of paragraphs!

During the revision process you’ll surely need to do some rewriting. You might need to clarify. Or prune dry words that are sapping the strength of your story. You might need to rake up and dispose of piles of information, dumped like dead leaves. But while revising it’s important to listen for your own voice — your own way of telling a story — and trust it. Whose story is this anyway?

There are some techniques to develop your voice:

As Peter Elbow says in Writing with Power; Techniques for Mastering the Writing Process, “A sentence should be alive. Does it sag in the middle or trail off at the end? Is it fog or mush? Sentences need energy to make the meaning jump off the page into the reader’s head… Stop beating around the bush. Stop Explaining things or talking in ‘essay’ or translating what you have on your mid into ‘writing’ language; just say it!” (pg. 135)

Have a few trusted critics read a section of your work and circle paragraphs or sentences that grab them, that come alive, for whatever reason. Now look at them yourself, read them aloud. Can you hear your own voice coming through? Now re-read some of your own work, listening for those parts that are so true, that feel natural, and are clear. Write more of them!

Be bold. Send your inner critic on vacation for the first drafts. Write from the heart to capture the soul of the story. Revise wisely. Don’t throw away the sweet inner meat of the coconut with the husk.

January 26, 2014

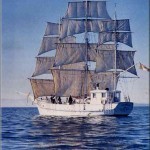

History lives aboard the North Star of Herschel Island

What would it be like to live aboard a historic arctic sailing ship? Freelance writer Bruce MacDonald wrote the book about the life and times of North Star of Herschel Island, his floating home for the past seventeen years. This working vessel once carried fur-trading Inuit, their sled dogs, and valuable pelts of white fox fur. (I feel bad for the foxes, but I’m always intrigued by how people make a living. )

What would it be like to live aboard a historic arctic sailing ship? Freelance writer Bruce MacDonald wrote the book about the life and times of North Star of Herschel Island, his floating home for the past seventeen years. This working vessel once carried fur-trading Inuit, their sled dogs, and valuable pelts of white fox fur. (I feel bad for the foxes, but I’m always intrigued by how people make a living. )

I asked Bruce how he was able to learn the ship’s story and bring it to life in the book; diligence, coincidence, oral histories –and Facebook –all play a part.

Bruce MacDonald writes:

When author Linda Collison asked fellow authors to share their methods of research I immediately thought back to when I first began to piece together my book about the last of the Arctic fur trading ships, North Star of Herschel Island. I have been writing magazine articles for over thirty years and have contributed to numerous cruising guides and nautical instruction books and so my research methods are fairly standard – a bit of Googling, a few trips to the library, and as many phone calls as it takes to get some original quotes to bring the story to life. With this book I had to set a completely different course.

My wife and I purchased and moved aboard North Star of Herschel Island with our children seventeen years ago. We knew that the ship was from the Arctic and had originally been owned by two Inuit fur trappers. There is an old photo album that shows some of her previous adventures but all that did was whet our appetite to learn and record her whole story.

The ship is like a floating museum with most everything aboard left unchanged from when she was built in 1935. From our first days aboard we have met a steady stream of people who have recognized the ship from their time in the Arctic and have stopped by to tell their stories. For instance, one evening we were sitting in the pilothouse having our supper when a lady knocked on the door and hesitantly spoke, “I grew up on this ship. My dad used to own her. So glad that you are taking care of her and I am sorry to disturb you.” She went to walk away but we convinced her to come and join us. Once aboard it turned out that not only did this woman, Margaret, grow up aboard North Star, she had been born on her.

Looking around the pilothouse and breathing in the old ship’s smell of tar and cordage she couldn’t help but let the tears start to fall and that evening she began to tell us what would become the outline for my research into the ship’s Arctic years. When we brought out the photo album Margaret couldn’t believe her eyes. “That’s a picture of my mother!” she said. “I have never seen a picture of her before. She died when I was very young – and look – she’s pregnant in this photo.” Looking at the date she began to cry again. “That’s me that she’s pregnant with.”

We copied all of the photos for Margaret and thus began a wonderful friendship. She identified everyone else in the photos and supplied me with names of other people that I could contact to learn more about the ship’s history.

The man that we had purchased North Star of Herschel Island from was in his seventies and over the following years we met regularly for coffee and to talk about his own adventures with the ship. Initially he was quite eager to help with the project but I soon ran up against a wall as he soon decided that he should write his own book on the same subject. Aside from North Star being the last of the Arctic fur trading ships she was also chartered by the Canadian government during the Cold War to assert Canadian Arctic sovereignty and to sail to and hold a remote island at the entrance to the NW Passage ‘for Queen and country’. She was also chartered to survey the controversial B.C./Alaska boundary and one infamous summer was chartered by some Cambridge University scientists to search for mermaids off of the Aleutian Islands.

It was her fur trading years, though, that most interested me when her Inuit owners, during the Great Depression, were making money hand over fist selling their white fox fur to European fashionistas, Buckingham Palace princesses, and directly to movie stars such as Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich. To learn of this time I would need to speak with the Inuit who were there, though they would have been children or teens at the time.

I began a letter writing campaign, asking people from different communities that the ship used to sail to such as Tuktoyaktuk, Inuvik, Aklavik, and Sachs Harbour, using the family names that Margaret had supplied me with. Of the many dozen letters that I wrote I received one or two replies and these were just suggestions of other people that I should speak with.

As the Arctic communities are quite small I was able to look up telephone numbers and so I tried phoning people. In most cases, probably due to call-display, no one would pick up. I later learned of how private these people are and how many of them are very distrustful of white people. If someone did answer there invariably followed an inquisition of who I was and how did I get their phone number. Since the people that I wanted to speak with are senior citizens and many were hard of hearing, my answers had to be shouted back. Inuvialuktuk is the dominant language in the western Canadian Arctic and many times people would just speak this, either to frustrate me into hanging up or because that is what they always speak.

At this point I had roughed out a good history of the ship but I really only had a few peoples’ stories to bring the book to life. I knew how much North Star had meant to so many communities in the ‘30’s until the ‘70’s but I was being stonewalled in my regular research methods.

Then one night I was looking over my daughter’s shoulder when she was on FaceBook and noticed the search bar. I had no interest in this site and made a point of steering clear of it as this was a place where our children could speak with their friends. I really did not want to know what they were talking about and respected their privacy. I asked her to type in North Star’s first owner’s surname and suddenly all of the names that I had written to or phoned over the last year scrolled up on the screen.

The next day I made a fan page for North Star of Herschel Island and on the front page made a request for Northerners to share their stories with me. In order to communicate with potential interview subjects I made my own account and fired off some friend requests. The floodgates opened! Turns out that the residents of these remote Arctic villages love FaceBook. When they get up in the morning they sign on and many of them just leave the site running all day long just to chew the fat with their neighbours. It might be too cold to visit in person but with this new technology they can chat back and forth. On numerous occasions I have seen someone put out an alert that a polar bear had been sighted close to town or that someone had done well hunting and had some meat to share.

In this environment with everyone party to the interviews and perhaps with strength in numbers, I was able to just about complete my research. The coup de grace came when I was invited to go north and stay with some Inuit elders who had strong memories of North Star and her original owners and whom when I arrived there kindly shared their memories and their own photo albums with me.

The Inuit have a long history of passing on their stories through the ‘oral tradition’ and so written first hand accounts are very rare. When I had showed them my good intentions by traveling to the high Arctic to meet them and when they learned that my family and I had been maintaining and living aboard their old ship a trust was formed and they recognized the importance of a permanent record for their ancestors to read.

The book was published in late 2012 and I was invited to launch it in Canada’s capital city, Ottawa, in the offices of the House of Commons in the Parliament Buildings. This would be akin to a U.S. author being invited to launch their book in the White House or a British author to be invited to the House of Commons and House of Lords. Through on-line crowd-funding with pre-sales of my book I was able to raise enough money to go on a book promotional tour twice across western Canada, stopping in bookstores, libraries, museums, and any other venue that would have me.

Scuttlebutt: Next month Bruce will be a guest on Julian Stockwin’s blog, so be sure to check it out!

North Star of Herschel Island is published by friesenpress.com and is available on Amazon in Canada, the U.S. and the U.K.

ISBN: hardcover 978-1-4602-0558-7

Softcover 978-1-4602-0557-0

e-book 978-1-4602-0559-4

The ship’s website is northstarofherschelisland.com and she has a strong presence on FaceBook. If you visit her page, please give her a LIKE. All proceeds from the sale of the book go to the ship’s maintenance fund.

January 20, 2014

Tom Rizzo wrangles research and storytelling

A good story of any genre brings the reader in, makes us feel a part of the setting and identify with the characters. Writing historical fiction is particularly challenging; the past must be brought to life in a way that is believable, yet doesn’t detract from the story. How do we maintain credibility without becoming historically pedantic? How do we walk the fine line between reporting the past and telling a story set in the past?

My guest today is Tom Rizzo, author of Last Stand at Bitter Creek; an action adventure historical novel, set in the United States, largely in the West, shortly after the Civil War. A finalist for the Western Fictioneers‘ Peacemaker awards, Tom also writes short stories; his latest is a western titled A Fire in Brimstone. I asked Tom if he’d share something about his writing process, particularly how he brings the past alive in his fiction.

My guest today is Tom Rizzo, author of Last Stand at Bitter Creek; an action adventure historical novel, set in the United States, largely in the West, shortly after the Civil War. A finalist for the Western Fictioneers‘ Peacemaker awards, Tom also writes short stories; his latest is a western titled A Fire in Brimstone. I asked Tom if he’d share something about his writing process, particularly how he brings the past alive in his fiction.

Striking a Balance Between Storytelling and Research

By Tom Rizzo

In its purest form, writing historical fiction is nothing more than telling a story set in the past. But, the process involves the double-edged sword of storytelling and research.

Like any story, historical fiction must include conflict, with a beginning, middle, and end, along with a blend of truths, half-truths, and untruths.

Research, while important, often stands as both a blessing, and a curse. It’s exciting to dig into other times and cultures, and learn how people lived, worked, and interacted, as well as the kinds of problems they faced and how they dealt with them.

The danger in conducting historical research is overdoing it to the point where it becomes overwhelming and, ultimately, paralyzing.

Collecting enough research to create a story is all about balance. It’s important to keep the focus on story, not research.

When I decided to write Last Stand at Bitter Creek, a historical action-adventure novel, I underestimated the time and the amount of work involved. I found myself bogged down in research—so much so, that—yep you guessed it—I almost lost sight of the storytelling process.

Unlike other genres, writers of historical fiction straddle the fence between historian and storyteller. But, you must have a feel for when you’ve reached the saturation point of research, and get to the business at hand—writing the story.

The appeal of the Old West, for example, is anchored in both a poetry and mythology of pioneering Americans. People were drawn to the West because of the challenge of overcoming the unknown. It’s important not to lose sight of this spirit during the storytelling process, rather than clog it up with unnecessary detail.

The poetry of the West, if you will, marries imagination and reality, an era of danger, opportunity, and freedom—three characteristics that make up the fabric of a good story.

While most tales of the West feature relatively simple plots and sometimes larger-than-life characters, the better stories are unique in the way they blend fact and fiction. But, in truth, stories of the American West are often all about actual larger-than-life individuals—courageous achievers who often surmounted incredible odds, even though they sometimes failed.

According to British historian David Murdock, “No other nation has taken a time and a place from its past and produced a construct of the imagination equal to America’s creation of the West.”

It’s all about good against evil, law against outlaw.

Research, of course, is important because historical novels should reflect actual history. It’s up to the writer to educate readers about the importance of a particular era by showing, in a fictional presentation, the impact of certain events and characters.

The research process is relatively painless, thanks to Internet access, local libraries and museums, the telephone and email, to track down, and interview various experts. Some authors make it a point to travel to a particular location to gather up-close-and-personal inspiration, and color.

The research that included should benefit both writer and reader, but in different ways. For example, my novel is set in the mid-19th century, just after the Civil War, and beyond.

Since I had no common knowledge, or reference point, for what life was like in the mid- to late-1800, I had to conduct enough research to learn how characters dressed, how they traveled, and how they communicated with each other. Sometimes, little things count. For example, how many miles could horse-and-rider travel in a day? How long did it take to get from point A to point B?

It all comes down to conveying realism. I had to find answers involving issues such as hotel accommodations, the price of a cup of coffee in a saloon, and what people of that particular era ate, and drank, and how they socialized.

My research also included learning about different professions—Army spy, burglar, doctor, farmer, cattle rancher, banker, and lawman. How did these individuals think? What motivated them? How did they deal with adversity?

Research, to me, involves learning enough that will help me understand—as much as possible—the behavior of the characters I’m writing about and, at the same time, get a sense of time and place.

Credibility earns the trust of readers. Writers of historical fiction need to know enough to create a believable fictional world for their stories.

Readers, however, want to experience a seamless transition into this fictional setting. They want to read a story, not a history lesson. They’re looking for entertainment.

On the other hand, James Alexander Thom, in his book, The Art and Craft of Writing Historical Fiction, writes:

“ Some readers are learning the history of their country through the story in my novel. They didn’t learn the history very well in school because it was taught in ways that were dry or boring. The historical novelist has a responsibility to keep the history as accurate as research can make it.”

Whatever the purpose, the highest compliment writers of historical fiction can earn is to hear a reader say, “I felt like I was there.”

XXX

Join me in following Tom on Facebook, Twitter, and on his excellent website.

January 14, 2014

Meet Jeanne Roppolo; adventuring grandma, author, and friend

Some of my best friends are writers.

Some of my best friends are writers.

I first met Jeanne Roppolo in Hawaii, as the sun set on the Kohala Coast, back in 1997. She was standing beside a big yellow tanker in jeans and a tee shirt, her eyes wide, hanging onto every word the professional trainer said. We were both brand new volunteer firefighters for Hawaii County, Company 14-A, and a little nervous about the rigorous training ahead of us.

Over the next months and years, Jeanne and I learned to pull hose and operate the nozzles; we learned how to use a fire extinguisher, how to rescue people off of rooftops and burning buildings, we learned how to jumpstart a heart with the automatic external defibrillator. Together, Jeanne and I fought many a brush fire on Hawaii’s west side (the dry side) in our yellow canvas brush jackets, our hair tucked up under our helmets, our faces smudged with soot. Jeanne was everyone’s favorite firefighter. She’s maybe 5’2″ in her brush boots and 120 pounds with all her bunker gear on; she’s got energy and enthusiasm to spare. She is likewise one of the most trustworthy people I know, and I’m proud to call her my friend.

Being a middle-aged female firefighter is just one chapter in Jeanne’s life. A few years ago she took a job in Antarctica. At a point when other women her age are thinking about retiring or spending more time rocking grandbabies, Jeanne goes off to McMurdo Station to work for six months. I told her she should write a book. She’s written four so far, and working on the fifth! I’m so inspired by this woman, this grandmother, this friend.

I asked Jeanne to share something of her writing process.

…While in the zen of my vacuuming at McMurdo Station, I was plotting my Antarctica adult memoir book when my dear friend and fellow firefighter, Linda Collison, author of numerous titles, the latest being Looking for Redfeather, suggested that I write a children’ book about my adventure at the bottom of the world. With wonder and amazement, (that I had never thought of that), I replied: “I can do that.”

…While in the zen of my vacuuming at McMurdo Station, I was plotting my Antarctica adult memoir book when my dear friend and fellow firefighter, Linda Collison, author of numerous titles, the latest being Looking for Redfeather, suggested that I write a children’ book about my adventure at the bottom of the world. With wonder and amazement, (that I had never thought of that), I replied: “I can do that.” And so it began…

My first draft was written with another children’ book as my guide. THIS IS WHAT I THOUGHT WAS EXPECTED. -So, I tried to fit into that format. When completed, I gave the result to a friend that I have known for over 45 years, someone who really knows me. She read my masterpiece (haha) & threw it back at me and said: “Do it over. Where is the passion? Where are YOU? This is NOT how YOU tell stories.”

You know what? My friend was right. That first draft was not me; that is not how I tell stories. I was trying to write the way I thought it was expected. I was trying to be something that I was not. So, I rewrote my adventure the way I verbally tell my stories. I changed my mind set. I no longer tried to be an author. I just wrote my story, my way. The result was 100% better. Writing my way, allowed my voice, my passion to come through on every page. This is who I am. I don’t consider myself an author. I am just sharing my stories…When YOU write—YOUR personality, YOUR passion needs to come through the written word. The end product has to be a reflection of you. If it is, you have succeeded. You are the writer of your own story.

Sincerely,

Jeanne Roppolo

About the “Grandma Goes to…” book series: Written for children, educational for all ages, and an inspirational read for the whole family. Visually stunning with 38 pages of color photographs. These children’s books meet federally-mandated, Common Core standards; a companion Teacher Study Guide is also available for each title.

In her motivational speaking engagements she conducts for children, teens, and adults, Jeanne Roppolo talks about her unusual life journey. This world-traversing grandmother loves to share her unique stories. Not just for kids.Be inspired! Follow her on Facebook! Purchase books and study guides, or schedule Grandma Jeanne to speak with your group (K-adults) via her website!

I hope Jeanne is planning a Grandma Fights Fires in Hawaii book in her series — if only for old times’ sake.

January 6, 2014

Getting inside the Victorian Mind

I’m pleased to welcome my literary friend Antoine Vanner to talk about how he creates believable characters in his Victorian-based historical fiction. Vanner writes The Dawlish Chronicles, of which Brittania’s Wolf is the first book of five (see my review on Amazon.) The story begins in 1877 during the Russo-Turkish War, a period the author is obviously knowledgeable about and feels at home in.

“I’m fascinated by the Victorian period,” Vanner told David Hayes for Historic Naval Fiction. “for not only was it one of colonial expansion and of Great Power rivalry that often came to the brink of war, but it was also one of unprecedented social, political, technological and scientific change… The Dawlish Chronicles are set in that world of change, uncertainty and risk.”

Antoine has survived military coups, a guerrilla war, storms at sea and life in mangrove swamps, tropical forest, offshore oil-platforms, and the boardroom. He has lived and worked in eight countries, has traveled widely in all continents except Antarctica and is fluent in three languages. His writing is both meticulous yet lively and action-packed. Vanner writes from a Victorian mindset, not from a twenty-first century perspective. Because of the psychological and social verisimilitude he achieves in his historical fiction, I consider him a fellow time-traveler. I entertain a little fantasy in which Vanner and I write a book together; I would be Florence Nightingale, or one of her nurses, and he would be Nicholas Dawlish, or one of his crew…

When I asked Antoine to give us some insight into how he thinks like a Victorian, here is his process:

Getting into the minds of characters in Historical Fiction

Getting into the minds of characters in Historical Fiction

by Antoine Vanner

I believe that the greatest single challenge in writing historical fiction is not getting dates, physical details of ships or weapons, forms of speech or linkages to real events right, but in getting into the minds of the characters. This means that they should think and feel as people in that period would have done and that they should not be 21st Century people in re-enactors’ dress. The most uncomfortable aspect of this may concern values and views regarded as acceptable by decent people in those days yet which would be considered abhorrent today. An example of this was the fact that many abolitionists in the United States had attitudes to African-Americans which we would regard today as patronising and demeaning, and that they saw resettlement in Liberia and elsewhere as a goal to be pursued once slavery had been abolished. Even Lincoln himself held such views to some extent.

When creating believable characters not all research should show up ultimately on the page but the writer should have a comprehensive mental picture of the world the character inhabited and how he or she would have thought or behaved in it. Main characters – and especially ones which recur in series fiction –should become real persons to the writer and their reactions to any set of set of circumstances should be consistent with the constraints, liberties, challenges and opportunities which that world represented, and with the values they hold. Any one book in a series will show a lead character at a particular period of their lives and credibility is enhanced if the writer has a view of what the totality of that life might have been, from birth to death. The “back story” of the character’s life up to the period of the book’s action determines how he or she will feel and behave, and the events in that book in turn will have a bearing on their thinking and behaviour in later books. In my own case my fictional hero, the Royal Navy officer Nicholas Dawlish (1845-1918) has featured in one published novel so far (Britannia’s Wolf) but I’ve already written three others and am currently at work on the fifth in the series. The second novel in the sequence (Britannia’s Reach) is due for publication early in 2014. I therefore have a sense that I’m writing (and researching) chapters in a biography, the main features of which I already know, even if the detail remains to be filled in. On my website an outline is provided of Dawlish’s whole life and further information will be added as more books are published. (dawlishchronicles.com)

My writing concentrates on the Victorian period (1837-1901) and though the settings are global the perspective is from a British viewpoint. At this time British power was approaching its zenith and though the sentiment that “God is an Englishman” might not have been stated in so many words the sentiment was widely held by all classes of society. As the British Empire expanded – more often than not by a series of accidents and by reactions to real or imagined external threats – Britons came in contact with a wide range of other cultures. And in most cases, when they matched them against their own values, they regarded them as wanting and shaped their own behaviour accordingly.

In getting into the minds of fictional characters, whether admirable or despicable, or somewhere on the broad spectrum in between, I see three major themes which must be addressed. These are:

Social and ethical values

Physical constraints of time and distance

What they didn’t know

For the Victorian periods – Dawlish’s era – there were major differences In all these areas with how people in English-speaking countries view the world today. In this blog I’m concentrating on the first of these themes but the others should not be forgotten and I may discuss them at some later date. My focus is largely on British values and thinking, not just in what is today the United Kingdom but in the major settlements in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa, where large numbers of emigrants settled. Much of what consisted of the remainder of the still-expanding empire saw very little permanent settlement by Europeans. The enormous area represented by “India”, which covered today’s India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, saw practically none, and it was administered by a few thousand British officials, garrisoned by a small British army supplemented by high-calibre Indian regiments.

What follows here is a non-exhaustive list of Social and Ethical values that influenced, or determined, how Britons thought and behaved in the second part of the 19th Century:

Many, and not only those in positions of power, felt pride about what Britain had achieved as a world power and, increasingly, unease about whether it could be maintained. Over the preceding three centuries Britain had been threatened by great Continental European tyrannies – Spain’s Phillip II, France’s Louis XIV and Napoleon – and it had survived, and prevailed, by a combination of superbly professional naval power, subsidy of European allies and deployment of armies, often small, on the European mainland only when unavoidable. Nobody knew with certainty in the late 19th Century that the pattern was to repeat itself twice in the 20th Century – and three times if the Cold War is taken into account – but there was growing unease about the rise of German power through and after the years of German unification. Despite this, for much of the period the main threats were still to be seen as coming from both France and Russia;

There was a widespread sense of national superiority. To many today there seems much that is smug about Victorians’ view of “foreigners” in general. This was perhaps largely founded however on awareness that social and political reform had been achieved by compromise and consensus, notably by the 1832 and 1867 Reform Acts, rather than by the revolutionary violence that had torn much of Europe apart in earlier decades. Even by comparison with Britain’s nearest continental neighbour there was much to be smug about since the 1830 and 1848 revolutions, the 1851 coup, Napoleon III’s tinsel empire and the horror of the Paris Commune, and its suppression in 1871, all reinforced the view that the British way was best;

The sense of national superiority allowed – even sanctioned – forms of religious and racial intolerance which shock us today. Though restrictions on Catholics, Dissenters and Jews had been removed by the 1870s, unofficial barriers often prevented their full acceptance in social life. Pockets of outright bigotry against Catholics persisted in Northern Ireland and Scotland and despite the friendship of the otherwise un-admirable Prince of Wales with leading Jews they too found it had to gain acceptance. The “humorous” magazine Punch routinely depicted the Irish as chimpanzees in cartoons that merit comparison with those of Jews in Julius Streicher’s scurrilous “Der Stürmer” in the 1920s and 30s;

Britain’s lead in abolishing the slave trade – and being ready to expend lives and money in continuing to suppress it as in both the Atlantics and Indian Oceans – and her outright abolition of slavery in all her colonies from 1834, allowed some justifiable feeling of superiority over nations which were much slower to follow suit (Outright abolition dates: France and Denmark 1848, Netherlands and United States 1863, Ottoman Turkey 1882, Spain 1888) ;

There was widespread awareness that social reform was being achieved, usually in fits and starts, but overall positively. Legislation had curbed the worst excess of exploitation of labour in general, and of women and children in particular, even it a lot still remained to be done. Labour was finding a voice through the now-legal trade-union movement and would emerge as a major political force by the end of the century. The Fabian Society was founded in 1884 and would have a massive impact on the politics and structures of later decades. Many of its early members, including Beatrice and Sydney Webb, H.G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw were to be influential well into the 20th Century;

By the early 19th Century the cruel and savage punishments that had disgraced earlier centuries were phased out and reform of the prison system was underway, even if conditions were still harsh by modern standards. Transportation to Australia was ended in the 1860s (though France was still transporting convicts to dreadful conditions in French Guyana up to 1953). A revulsion against public executions led to their ending in the 1860s. Unpleasant as long-drop hanging in private might have been it was less brutalising than the spectacles of public beheading (for the last time in France in 1939) or of execution by slow-strangulation in Spain (used last in 1978). Another manifestation of this greater humaneness was the movement against cruelty to animals. This increasing sensitivity was to a significant extent responsible for ruthless reaction by British forces when they encountered atrocities committed, and considered acceptable, by other cultures. The most extreme example of this was the retribution meted out to rebellious sepoys during the Indian Mutiny, and triggered by massacres of British women and children such as at Cawnpore. In my novel Britannia’s Wolf, the hero, a British officer, is revolted by a similar massacre elsewhere and he exacts retribution, without hesitation, in a way that would certainly be called a war crime today;

Though cholera and infectious diseases generally had been major killers up to the middle of the century, improved sanitation and supply of clean water from the 1860s onward, often involving huge projects, had a significant impact on life expectancy. For many families the loss of one or more children had previously been regarded as all but inevitable. It’s hard today to imagine the sorrow that had been so widespread from this cause – and for the first time the numbers involved were starting to fall. Florence Nightingale’s virtual invention of the modern nursing profession, the application of anaesthesia and antiseptics and the discovery of the bacterial source of many infections brought relief to millions. Despite this, medicine was till primitive by modern standards and bed-rest was the only prescription for many illnesses;

Religion (and Disbelief) was taken very seriously by the steadily growing middle-class, not just in outward forms which included strict Sabbath observance, but as regards how religious faith consciously influenced personal behaviour. (A fascinating insight to this can be got from Edmund Gosse’s wonderful memoir Father and Son). Political and military leaders felt no embarrassment about admitting to praying for guidance. Disbelief was approached with similar earnestness (itself a great Victorian virtue) and for those whom Darwin’s Origin of Species (1858) forced reassessment of their beliefs the process was painful in the extreme. It was notable however that religious belief and observance was weaker, and frequently non-existent, at the extreme upper and lower levels of society;

Higher ethical standards in public life and service were demanded from the mid-century onwards. Corruption, nepotism and bribery had been accepted as integral aspects of government and administration up to the early 19th Century, as they are still in many countries today. In Britain however, from mid-century onwards, a politically-neutral civil service was created which was recruited, and promoted, on merit, and held to strict standards of accountability. Local government, notably in great urban centres such as London, Birmingham and the major northern manufacturing cities followed a similar course. Reform of the Army, especially abolition of purchase of commissions, also followed a similar path. There was still a long way to go but there was a general awareness of steady progress;

Food was getting cheaper, partly due to the abolition of the Corn Laws in the 1840s (but not soon enough to stop the Irish Potato Blight deteriorating into the Irish Potato Famine) which allowed importation of grain from Russia and North America. The invention of refrigeration, brought affordable meat imports from as far afield as Argentina and New Zealand from the 1880s onwards;

Technology was impacting on the lives of ordinary people at an unprecedented rate, and usually improving them. Gas lighting and, by the last decades of the century, electric lighting made for greater home comfort and facilitated reading of the flood of cheap newspapers, magazines and books that new printing techniques made possible. Ever more efficient railways made commuting from more distant suburbs a reality and London’s underground railways set the example for mass-transit schemes elsewhere. The penny-post and the very efficient organisation that supported it (up to three deliveries a day in large towns and cities) allowed families to keep in hitherto undreamt-of easy contact. The telegraph had linked all major parts of the globe by the 1880s but for most people a telegram was too expensive to send, even locally, except in emergencies. And few imagined that from 1914 onwards the sight of a telegram delivery boy was one to chill the blood have

Awareness of class differences probably reached its climax in this period, becoming almost an obsession with the expanding Middle, Lower Middle and “Respectable Working” Classes. Above these levels nobody was much concerned, being convinced of their own superiority anyway, while the Underclass was too focussed on survival to care. “Respectability”, difficult to define but known when seen, was a goal to be striven for. The Church, Law, Medicine, the Army and the Navy were no longer the only professions to which gentlemen cold belong as room was made for accountants, bankers and stockbrokers, though not necessarily on equal terms. (Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage is excellent on this). Bizarrely, given that Britain’s wealth was built on industry, engineers never achieved the status they did in the United States or Continental Europe and indeed still haven’t. “Trade” remained looked down on, the term applying to profit-making ventures of any type and minor land-owning gentry sneered at millionaires who had made their money in business or industry. These millionaires in turn bought landed estates and angled for knighthoods and peerages, striving to ensure that their own sons and daughters would escape the taint of trade. “Marrying beneath one” could invite a lifetime of humiliation, if not social ostracism, a concern that troubles the hero of Britannia’s Wolf even as war rages around him and his survival hangs in the balance;

Servants, male and female, represented a huge percentage of the working population, valued and reasonably well remunerated at the senior levels of butler, housekeeper or cook, but paid pittances at lower levels such as scullery maid. Even allowing for inflation, £10 a year, plus food and accommodation, was not overgenerous, especially when one free day, or even half-day, might be provided per fortnight and working days might be up to 16 hours. Even modestly prosperous families could afford a single servant and having one was one mark of respectability. (A very realistic picture of lower middle-class life in the 1880s can be had from the Grossmiths’ very entertaining Diary of a Nobody). An unpleasant aspect of the system was that young female servants were often the victims of rape by employers, or by their sons. Tess of the d’Urbervilles’ case was not unusual;

Which brings us finally to Sex. There is a widespread modern misconception that Victorians disliked and disapproved of it but the large families of the period, including Queen Victoria’s nine children, give the lie to it. There was however good reason to be careful. There was no reliable method of contraception and pregnancies were often dangerous, indeed fatal. The commonly held view that that “Good Women do not like Sex” probably had much to do with this. Educated and reasonably wealthy women who had produced “the heir and the spare” were reluctant to have more children, which only sexual abstinence could guarantee. In such cases gentleman would be unwilling to force the issue, but in many cases would find solace elsewhere. What were referred to by Sherlock Holmes as “separate establishments” were not unusual and prostitution flourished. Fear of unwanted pregnancy also inhibited easy sexual relations outside marriage and a major lack or realism in many historical novels and movies is the ease with which characters jump into bed together! Though savage legal penalties applied to homosexual practices (life imprisonment for Sodomy and two-years’ hard labour for Gross Indecency) they seem to have been seldom applied. A blind eye seems to have been turned by the authorities to an active Gay sub-culture, the view being that “You can do what you like as long as you don’t do it in the street and frighten the horses”. Only when high publicity was involved, as in the case of the Oscar Wilde and Cleveland Street affairs, was action taken. Wilde himself would probably never have been prosecuted had he not brought the matter into the open himself.

What’s listed above provides only the sketchiest outline of a complex and rapidly changing culture. Many of its features are familiar to us in our own day, sometimes in an evolved form, but others are jarringly different. We have the advantage of knowing “what happened next”, which the people of the time did not, and we know what aspects led to positive or negative long-term outcomes. It’s a world like this which a historical novelist must make his or her characters citizens of, not people of our own day acting out parts in period dress. Any character will be conscious of, or driven by, or oppressed or advantaged by any of the factors above. Even if this does not emerge explicitly on the page it’s essential for the novelist’s own mental picture.

And finally, for me, writing about “the day before yesterday” in historical terms is much easier than novelists dealing with older and remote periods – but for all of us, regardless of era, the joy or research and creation is a delight.

December 29, 2013

Cli-fi: A perfect storm of sci-fi and global warming

Joining me today is author Joe Follansbee, one of my nautical writer friends whose work I admire. I have two of his books: The Fyddeye Guide to America’s Maritime History, and Bet: Stowaway Daughter, a young adult novel. Joe, what are you working on these days? Saltwater fiction? Joe writes back,

Joining me today is author Joe Follansbee, one of my nautical writer friends whose work I admire. I have two of his books: The Fyddeye Guide to America’s Maritime History, and Bet: Stowaway Daughter, a young adult novel. Joe, what are you working on these days? Saltwater fiction? Joe writes back,

Get two or more writers in a bar and they’ll argue about genres. The conversation goes like this:

Q: What are you writing these days?

A: I’m working on a sci-fi mystery novel, though I think of it as speculative crime thriller, with elements of paranormal erotic Regency romance.

Eyes of all other writers at the table glaze over.

This happens to me at least once a week when I mention an emerging sub-genre: “climate fiction,” or “cli-fi.” A blogger friend, Dan Bloom , coined the term in 2008 to describe novels with global warming as an important part of the narrative. Dan is a public relations man and a climate change activist who noticed that science fiction writers hadn’t paid much attention to global warming as subject matter. The few who did needed a label of their own, thus “climate fiction.” Dan sees cli-fi was a way of engaging the public on climate change that doesn’t rely on boring stats or the constant hedging by scientists that leave openings for compulsive deniers.

The mainstream took notice of the term in 2013, when The Guardian newspaper and NPR ran pieces on the genre. The debate has raged since then, with arguments falling into three main camps: Yes, it really is a new genre; Maybe, it’s just a sub-genre of sci-fi; or No, it’s a made-up genre that will fade into obscurity.

The debate smacks of the how-many-angels-dance-on-the-head-of-a-pin arguments of scholars in the Middle Ages, but it illustrates the importance of genre in the publishing world. Potential book buyers need shorthand ways to refer to fiction with certain themes or tropes. For example, “fantasy romance” didn’t emerge as a shelf label until 2005, with the release of the wildly popular, vampire-populated Twilight series. These days, you can’t swing a cat at a writers conference without hitting three or four authors with a vampire love story in hand.

Climate fiction hasn’t enjoyed a Twilight moment yet, though several well-known writers have adopted the term, notably Margaret Atwood, author of the MaddAddam series. Like most cli-fi stories, Atwood’s world is ravaged by global warming, which becomes a new crucible for human thought and behavior. In other words, climate change is a driving force behind the narrative. For her part, Atwood prefers the term “speculative fiction,” but the series has definite dystopian and science fiction themes. Other recent novels that fall into the climate fiction bin include Nathaniel Rich’s Odds Against Tomorrow, and Ian McEwan’s Solar.

The NPR story, which aired on April 20, 2013, inspired me to finish a novel I had started in 2008. In Carbon Run, a tall ship sailor lives in a post-global warming world where all carbon-based fuels are banned and a Gestapo-like agency enforces draconian environmental laws. I wrote a dozen chapters over a three or four month period, then shelved the project when I found myself in a narrative cul-de-sac. It took a new label, climate fiction, to get me thinking again about the novel. If I could tie the premise to a topic on everyone’s lips, I thought, perhaps I could find a market. I finished the manuscript in December 2013 and I’m awaiting responses from agents and publishers.

Despite its usefulness, I don’t use “climate fiction” often to describe Carbon Run, even with writer friends. Their confused grimaces signal that it’s too new. “Science fiction” works better, and I use the phrase “dystopian science fiction adventure” in pitches to agents and publishers. But I do tag tweets with #clifi and mention it on my blog and Facebook page in hopes that one day, my book will sit on a shelf with the likes of Atwood, Rich, and others. That will give me bragging rights next time I’m arguing in a bar with other writers.

Joe Follansbee is the author of eight books, including the young adult novel, Bet: Stowaway Daughter. He blogs at joefollansbee.com , tweets as @Joe_Follansbee , and posts on Facebook as AuthorJoeFollansbee. I follow him on all three