Linda Collison's Blog, page 22

June 18, 2013

Hawaiki Rising

Bob and I sailed our 36 foot sloop from Hawaii to French Polynesia in 2000, an experience which gave us a great appreciation for the Polynesian voyagers of old who populated the Pacific. Living in Hawaii for so many years, we followed the voyages of Hokule’a and read everything that came out about the renaissance in traditional wayfinding. A new book has just been published and released in Hawaii. Hawaiki Rising by Sam Low.

As the night wore on, the swells built to twenty feet and began to break. “Two big ones rocked the whole canoe,” Chad recalls. “They went over us and I heard Gordon yelling “Is everybody okay?” Then another wave hit us and I remember one guy grabbed me by the shoulders and looked at me with big eyes and a pale face — ‘This is it,’ he yells. ‘This is it.” — page 233 Hawaiki Rising.

Sam Low’s “Hawaiki Rising” is an important addition to the growing collection of books about the renaissance of traditional wayfinding on the Hokule’a, and the resurgance of Polynesian voyaging and the science and art behind it. This book differs from previous classics (“Voyage of Rediscovery” by Ben Finney, “We, the Navigators” by David Lewis, “An Ocean in Mind” by Will Kyselka, “Voyagers” by Herb Kawainui Kane) in that it’s more of a narrative of the human dynamics of the early voyages. The author provides enough science and nautical information for understanding, but his real contribution is the candid revealing of the human drama that was at the core of these exciting voyages. He uses quotes from other crewmembers to recreate the experiences and lend validity to his account. His account of the loss of Eddie Aikau was absolutely riveting and reverent; he brings out the psychological effect it had on the entire crew and the future of Hokule’a. Sam Low concentrates more on the people, the voyagers themselves, and after reading it I feel like I know them a little better and have an inkling of what they went through.

My husband and I had the pleasure of hearing Sam Low and Nainoa Thomson introduce the new book at Imiloa in Hilo (June, 2013) as the Hokule’a is beginning another voyage. This book offers yet another perspective of the now legendary experiment and cultural revival of traditional Pacific voyaging.

Immensely readable and highly recommended. If you aren’t familiar with the story of Hokule’a and the Polynesian Voyaging Society, this book is an excellent one to read first.

June 17, 2013

Judas Island

Joan Druett’s Judas Island, the first book in her Promise of Gold series, features a young woman on a free trader’s ship in the mid-nineteenth century– a topic Joan knows quite a lot about. As a maritime historian Joan has written numerous books about shipboard life in the age of sail. Many of her books (Hen Frigates, Petticoat Whalers, She Captains, Rough Medicine, In the Wake of Madness and Tupaia) are longtime companions of mine and hold a special place on my bookshelf. They influenced me (and made for entertaining reading) when I was researching my first historical novel Star-Crossed and its sequel Surgeon’s Mate.

Joan Druett’s Judas Island, the first book in her Promise of Gold series, features a young woman on a free trader’s ship in the mid-nineteenth century– a topic Joan knows quite a lot about. As a maritime historian Joan has written numerous books about shipboard life in the age of sail. Many of her books (Hen Frigates, Petticoat Whalers, She Captains, Rough Medicine, In the Wake of Madness and Tupaia) are longtime companions of mine and hold a special place on my bookshelf. They influenced me (and made for entertaining reading) when I was researching my first historical novel Star-Crossed and its sequel Surgeon’s Mate.

I was immediately engaged and found it a quick, absorbing story.

The protagonist, nineteen year old Harriet Gray. is an actress from a family of actors, her mother of some repute.

“We were a stage family, with stage traditions. And my mother was indeed famous.

In the Victorian era an actress had a social standing just above a prostitute. Yet Harriet is a wily actress and it’s a good thing, since in that era a woman pretty much had to depend on a man for her livelihood and Harriet’s husband had run off, leaving her in dire straits.

And, as the lawyer had pointed out, desertion, no matter how heartless, was not considered a public scandal. It happened all the time. Thousands of men left their wives penniless while they hunted fortunes in other lands.

[Harriet] said, “I acted. After all, that is all I can do.”

Harriet is clever and resourceful. She comes aboard Captain Dexter’s brig Gosling with a scheme to get to Valparaiso.

Jake Dexter, captain of the brig, has bent the law many times and many ways in order to make his livelihood.

At no time was it possible for him to forget that he was carrying passengers, and at all times he remembered a vow he had made right from the beginning – that he might smuggle goods through borders, that he might take on cargoes that were forbidden by local authorities, that he might trespass on foreign soil to spy for money, or go fortune-hunting on a hunch, but he would never touch the slave trade, and he would never carry passengers.

Harriet has a plan for her own survival and Captain Jake Dexter is always looking for cargo to carry that will bring him a good return. But neither one plans on an epidemic of California gold fever to change the game.

The sexual tension between Harriet and Jake combined with the contest of their wills, the other characters aboard, and the ultimate fate of the ship kept me turning the pages. (I kept thinking of Humphrey Bogart and Katherine Hepburn in the classic movie made of C.S. Forester’s book African Queen.

Druett’s historical fiction rings of verisimilitude (I love that word…) She knows her way around a ship and she’s also quite at home in the time period. She knows her world — and her craft.

Judas Island is published by Old Salt Press, a cooperative venture you’re going to be hearing a lot more about.

Joan has authored many books, both novels set at sea, and nonfiction nautical studies. She often gives lectures at sea. She’s my mentor as I undertake my first nonfiction nautical book. Here’s her blog.

June 16, 2013

Privateering with Mark Knopfler

“…To hear the rollers thunder on a shore that isn’t mine…” Doesn’t that just make your heart leap? Your skin tingle?

Mark Knopfler

I’m cooking up a Father’s Day dinner listening to Privateering, Mark Knopfler’s latest CD. Bob and I heard Knopfler perform this in Dublin, Ireland, on his 2011 tour. Yeah, we’re Knopfler groupies. Damn, this is gonna be a great father’s day dinner. It always is, when I cook to Mark Knopfler. Don’t mind my singing along. (Menu: Bacon wrapped jalapeno peppers, gorgonzola burgers, Waimea greens, Chainbreaker White IPA from Bend Oregon). Here’s to fathers and privateers. Cheers!

To really appreciate it, you have to hear it and sing along. With a bottle of beer in one hand and a spatula in the other.

Yon’s my Privateer

see how trim she lies

To every man a lucky hand

and to every man a prize

Come with me to Barbary

We’ll ply there up and down

Not quite exactly

in the service of the Crown

June 11, 2013

Looking for Redfeather, coming soon…

Three runaway teens, a “borrowed” Cadillac Eldorado, and an elusive Apache named Redfeather…

I’ve been published traditionally, by Alfred A. Knopf (Random House) and by small publishers Pruett and Fireship Press. Now I’m publishing my own book under the imprint of FICTION HOUSE, LTD. – - using CreateSpace for my editorial and printing services. Looking for Redfeather will be published this summer in trade paperback and electronic editions. Read the first chapter.

Most of my friends and readers are familiar with my nautical historical fiction; Star-Crossed, which led to Barbados Bound and Surgeon’s Mate. There’s nothing nautical about Looking for Redfeather (although Chas and Ramie do go swimming in the Gulf of Mexico, off Padre Island.) Historical elements and cultural references are woven into the contemporary story, set in the American West.

I wrote the first draft in November, 2007, during National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) when I was back east promoting Star-Crossed (Knopf; 2006). I workshopped it with the Steamboat Writers Group, a fellowship of Colorado writers, with good feedback. Presently, as the manuscript is being edited, I’m working on the play version.

If you liked Kerouac’s On the Road, you might like Collison’s Looking for Redfeather. It’s a different age but it’s still a road trip. A coming of age.

April 21, 2013

A brief history of hospital ships, part 2

I became interested in the history of hospital ships and shipboard medicine while researching my historical novels, Barbados Bound and Surgeon’s Mate, that take place during Britain’s rise to naval power in the 18th century. Before that, most battles were seasonal affairs fought close to home; hospital ships were essentially boats used to transport those wounded in battle a short distance back to land.

The 1700s saw the beginnings of far-away wars as European powers began to colonize and wrest economic control from distant lands and seaways. The Seven Years War (1756-1763) often referred to as the French and Indian War in North America, was the first World War; its conflicts and power struggles were between multiple nations in far flung theaters around the globe. A threat more deadly than mortar and shot was disease. Disease killed more soldiers and sailors in the 1700’s and 1800’s than did all the enemies’ weapons combined. Vessels were assigned temporary hospital duty – especially in tropical latitudes where diseases such as malaria , yellow fever, and other “tropical fevers” were endemic.

Like prison hulks, hospital ships were usually vessels that were no longer suited for the line of battle. It was cheaper and more efficient to have a floating hospital that could follow the fleet rather than to build and staff land-based hospitals all over the world. Then too, the air was thought to be more salubrious offshore. The germ theory of disease had yet to be developed and it wasn’t known that mosquitoes carried the microorganisms that caused many of these tropical fevers. Many of the ill suffered from scurvy as well – a vitamin C deficiency, as it would later be identified. Soldiers and seamen too ill or incapacitated to fulfill their duties were sent to hospital ships to recover, thereby relieving the warships of the burden.

The age of steamships meant vessels were no longer at the mercy of the winds. While their overall speed wasn’t much faster, the speed was consistent and independent of wind direction. In the late 1800’s as the United States began to embrace steam power and moved from a policy of isolationism to one of imperialism, the outcome was the Spanish American War. Realizing the success of the Red Rover as a floating hospital (discussed in my previous entry) the U.S. Navy made more extensive use of hospital ships in the war with Spain (Milte Riske, “A History of Hospital Ships.” SEA CLASSICS; March, 1973.)

U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt flexed his muscles, sending a “Great White Fleet” of sixteen battleships on a circumnavigation as a show of U.S. power. The hospital ship Relief was part of this imperial cruise. While the fleet was in the Mediterranean it responded to a deadly earthquake in Italy, rescuing many and proving that hospital ships could also be used for humanitarian purposes as well as support for battleships. Unfortunately, the Relief proved unseaworthy in a Pacific typhoon and was reassigned as a floating dispensary in the Philippines, her name changed to Repose, but other ships were designated as hospitals and played a role in the Spanish American War.

In response to the crisis in Cuba a passenger steamship, S.S. Creole, was purchased by the U.S. Navy, renamed the USS Solace and converted for hospital duties in just sixteen days — thanks in part to a donation from the Red Cross Committee. The Solace was the first U.S. Navy ship to fly the Geneva Red Cross flag. Solace was in use during the entire conflict, shuttling wounded Americans back to Norfolk, New York, and Boston.

The Olivette, another American steamer-turned-hospital ship, supported the U.S. invasion of Cuba, receiving wounded Spaniards as well as Americans. Enemies such as Admiral Cervera, Commandant of the Spanish fleet, along with many of his officers and men.

The steamship Missouri sailed under the British flag before becoming an American hospital ship in the Spanish-American War. While still in commerce, the Missouri went to the aid of the Denmark, an immigrant ship out of Copenhagen bound for New York. The Denmark signaled “Am sinking; take off my people.” Captain Murell jettisoned his cargo to make space for the rescued passengers and every soul was saved. Later, this same ship and her crew rescued the steamship Delaware and towed her to Halifax, and towed the foundering Bertha to Barry, England. The Missouri also carried cargoes of flour and corn to the starving Russians during the famines of 1891 – 1892, after which she was offered to the Surgeon General of the Army by her owner, B.M. Baker, of Baltimore.

“Hospital ships are children of necessity, mothered and fathered by wars,” says Milt Riske in “A History of Hospital Ships.” (Sea Classics, March 1973. United States Naval Hospital Ships, a Naval Historical Foundation Publication.) Sadly, that is all too often the case and our country’s shameful actions in the Spanish American War, particularly in the Philippines where we slaughtered so many men, women and children in the name of Imperialism.

In a future post I’ll discuss humanitarian and mercy ships — ships not born of war but of altruism.

April 10, 2013

A brief history of hospital ships; part I

According to historian and author J. David Davies, the concept of a hospital ship was well established in 17th century Britain. During the Anglo-Dutch wars most casualties were taken ashore in small boats, though several dedicated hospital ships including the Loyal Katherine, the Joseph, the Maryland Merchant, and the Helderenberg were commissioned during the second Anglo-Dutch war.

Yet during those “neighborhood wars” many injured sea men were cared for in private homes in seaport towns. In Davies’ book Pepys’s Navy; Ships, Men & Warfare 1649-1689, he describes private citizen Elizabeth Alkin, known as Parliament Joan, who nursed seamen at Portsmouth before 1653, when she moved to Harwich. She used her own resources for the men’s care, which included Dutch prisoners of war and was partly compensated by the government before she died in 1655.

During Queen Anne’s wars women served on hospital ships, says Christopher Lloyd in The British Seaman. Suzanne Stark has more to say on the subject in Female Tars; Women aboard ship in the Age of Sail. In 1696 each of England’s six existing hospital ships was to be assigned six nurses and four laundresses. They were paid able seamen’s wages. There were continual complaints that the women were drunk and disorderly, but there were also complaints of the male assistants being drunk and disorderly. According to Stark, hospital ships were usually worn-out sixth-rates or converted merchant vessels. There was usually only one surgeon aboard, about four suregeon’s mates, six nurses, and four laundresses.

In 1703 Admiral George Byng and Daniel Furzer, surveyor of the navy, recommended that the women nurses be replaced by men. The navy ruled that women would not be hired to serve in hospital ships, “except when circumstances required.” Such circumstances quickly developed that same year. (Incidentally, Admiral George Byng was not the Admiral John Byng who was court-marshaled and put to death in 1757 during the Seven Years War with France pour encourager les autres – or, failing to do his utmost to prevent Minorca from falling to the enemy.)

I’ve found a few mentions of American vessels serving as temporary hospital ships during the early nineteenth century, the most famous being the ketch, Intrepid. A few months after Stephen Decatur used the Intrepid to sneak into harbor to destroy the U.S. frigate Philadelphia which had been captured by the Tripolitans, the ketch served briefly as a hospital ship in the Mediterranean.

During the American Civil War the Sanitary Commission and the U.S. Army charterd steamers as makeshift floating hospitals on the Western Rivers. It wasn’t until December 26, 1862 that the United States Navy commissioned its first hospital ship. The Red Rover was a sidewheel steamship the Union Army captured from the Confederates. The Illinois Prize Board sold the Red Rover to the Navy The ship’s first patient as a commissioned hospital ship was a cholera victim. The medical staff included 30 surgeons and male nurses, and four female nurses; sisters of the Order of the Holy Cross. They were joined later by several other nuns and some black female nurses. When a naval hospital was built in Memphis, Tennessee, the Red Rover was relieved of some of her duties and she was removed from the service November 17, 1865.

February 4, 2013

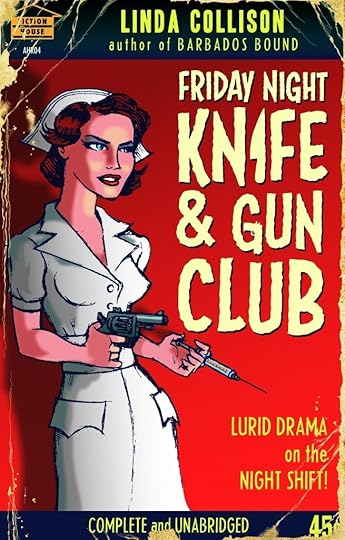

Friday Night Knife and Gun Club — a short story

I love this cover art created by graphic designer and re-enactor Albert Roberts. He’s totally captured the kitch and the drama I had in mind for the cover art for my new short story, just published on Kindle. I’m having the cover art made into a poster to hang on my wall to inspire me to finish the collection of short stories and speculative memoir about nurses that I’ve been working on for, well, decades.

I love this cover art created by graphic designer and re-enactor Albert Roberts. He’s totally captured the kitch and the drama I had in mind for the cover art for my new short story, just published on Kindle. I’m having the cover art made into a poster to hang on my wall to inspire me to finish the collection of short stories and speculative memoir about nurses that I’ve been working on for, well, decades.

The nurses in Friday Night Knife and Gun Club aren’t ordinary nurses. They live and work in a dystopian near-future, in an unnamed city in the American West (actually, it’s Denver, where I lived and worked for many years) where nearly everybody carries a gun to protect themselves from the loonies. Yep — it’s the wild Wild West. And yes, my tongue is in my cheek.

There’s nothing nautical about this story. And although it’s fiction, I didn’t have to make very much up. A lot of it comes from my own life.

I was compelled to write it after the shooting that took place at a hospital in Alabama in December. Which took place just after the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Connecticut, which took place after a random mall shooting in Oregon, which took place a few months after the theater shooting in Colorado. Not to mention the Gabby Giffords shooting in Arizona, the Columbine school shooting in Colorado, the Virginia Tech shooting… and the beat goes on. And on. And on.

I am not against guns. I am against the easy availability of firearms and large magazines. I am against the idea that the way to fight violence is with more violence. All those years I worked in the hospital — in emergency and ICU and psychiatrics and oncology — I sometimes thought about what would happen if some angry sociopath came in with a gun and started shooting us up. In this dystopian short story I’ve re-imagined that horror. But I’ve given it an ironic twist. I’ve given the nurses guns. It’s lurid drama, it’s urban fiction, yet it’s all too real.

Friday Night Knife and Gun Club is available on Kindle for 99 cents — and I’m offering it free this week. I’m hoping to have the entire collection of short stories completed by the end of 2013 and ready for publication, both in print and electronic format. Meanwhile, I hope you’ll find this short piece provocative.